Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 519-527Original Article

PREPARATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF NOVEL LOXOPROFEN-LOADED SOLID LIPID NANOPARTICLES

TABAREK KHALID HASAN1*, MAZIN THAMIR ABDUL-HASAN2

1Department of Pharmaceutics, college of Pharmacy, University of Al-Qadisiyah, Al-Diwaniya, Iraq. 2Department of Pharmaceutics, college of Pharmacy, University of Kufa, Najaf, Iraq

*Corresponding author: Tabarek Khalid Hasan; *Email: tabarekk.alshamarti@student.uokufa.edu.iq

Received: 05 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 15 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) exhibit many beneficial characteristics in the formulation of drug delivery systems. Loxoprofen (LX) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). This work aims to prepare and evaluate novel LX-loaded SLNs (LX-SLNs).

Methods: Experimental formulas were developed using Design-Expert 13. The Formulas were prepared via hot emulsification followed by probe ultrasonication then evaluated for their particle size, polydispersity index (PDI) and entrapment efficiency (EE%). The optimum formula was selected and lyophilized for further testing of fourier transformed-infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), powder x-ray diffraction (PXRD), and field emission scanning electronic microscopy (FE-SEM). In vitro release studies were conducted on pure LX and five formulas with varying lipid amounts and types.

Results: The optimization LX-SLNs formulations was performed using Design-Expert 13, with run 13 identified as the optimal formulation. This formulation, containing glyceryl monostearate (GMS) and poloxamer 407 (PX407), showed the best overall results in terms of particle size (70±4 nm), PDI (0.02±0.001), and EE% (88.07%±0.8). The release studies demonstrated sustained release behavior, with a decrease in the release rate as the lipid amount increased. Drug-excipient compatibility was confirmed by FTIR analysis, while PXRD results showed the disappearance of the sharp peaks found in the pure materials, indicating reduced crystallinity and suggesting that the drug is either in an amorphous form or dispersed in a solid solution state.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated successful encapsulation of LX in SLNs, with lipid content controlling the drug release rate. Higher lipid content demonstrated slower drug release.

Keywords: Solid lipid nanoparticles, Glyceryl monostearate, Loxoprofen, Probe ultrasonication, Controlled release

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54465 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

The discovery of new chemical entities with therapeutic potential drives the need for innovative drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutical formulators face numerous challenges, prompting the development of diverse strategies to accommodate a wide range of therapeutic agents-from small molecules to complex biologics like proteins and nucleic acids. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery has emerged as a promising approach, offering advantages such as enhanced drug solubility, stability, high loading capacity, targeted delivery, and controlled release, making it valuable for both pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical applications [1-3]. Lipid-based nanoparticle have received the attention of many scientists due to high biocompatibility and biodegradability. Liposomal formulations were the first lipid-based nanoparticles to be investigated for drug delivery [4, 5]. Liposomal formulations have been widely investigated with different chemical compounds from anticancer agents to topically used cosmetic agents such as kojic acid dipalmitate [6]. Phospholipid instability, due to hydrolysis and oxidation, affects liposome stability, causing drug leakage, aggregation, short shelf life, delivery failure, and potential toxicity [7]. Another example is self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS), which are isotropic mixtures of oils, surfactants, and co-surfactants that spontaneously form emulsions or microemulsions in gastrointestinal fluids due to GIT movement and fluid content [8]. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), in comparison to liposomes and SEDDS, show greater chemical stability [9]. SLNs are similar to nanoemulsions in that they are composed of lipids dispersed in aqueous media with the aid of surfactants, however, the key difference is that the lipids used are solid at room and physiologic temperature [10]. SLNs are considered versatile nanocarriers as researchers have utilized SLNs have to deliver a wide variety of therapeutic agents ranging from small molecules such as rivastigmine tartrate [11] to biological macromolecules such as erythropoietin [12]. SLNs as colloidal drug carriers, integrate the advantages of both polymeric nanoparticles and liposomes, offering enhanced physical stability, the ability to encapsulate both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for scale-up and industrial production [13]. Loxoprofen (LX) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) [14]. Chemically, LX is a propionic acid derivate [15]. Clinically, LX is used orally and topically in the management of inflammatory disorders and pain in many illness of the skeletomuscular system, whether acute or chronic. Also its used in the management of post-operative pain. Several advanced LX delivery systems have been developed to enhance bioavailability, controlled release, and targeted delivery. These include omega-3-based nanoemulsions to improve permeation and reduce gastrointestinal side effects; Nano-sponges [16], nanocrystals to enhance solubility and gastroretentive floating tablets [17] and bilayered tablet for prolonged gastric residence [18]. However, no study to date has investigated SLNs for LX delivery. SLNs present multiple advantages over other systems. Their components are biodegradable, biocompatible, and generally recognized as safe (GRAS). The solid lipid matrix enhances physical and thermal stability by preventing phase separation, coalescence, and oxidative degradation-issues common in liposomes and nanoemulsions. SLNs also ensure better drug retention and controlled release, minimizing premature leakage [13]. These features highlight the untapped potential of SLNs for improving LX delivery, making this study a novel and valuable contribution to the field. To optimize LX-SLNs formulation, this study applies the Quality by Design (QbD) approach, [16]. QbD, through Design of Experiments (DOE), enables systematic identification and control of critical process and formulation variables, reducing experimental burden while enhancing product quality [17]. The present study utilizes DOE to develop LX-SLNs with optimal encapsulation efficiency and particle size [18].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Loxoprofen was purchased from Combi-Blocks Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA). stearic acid was obtained from Himedai, Glyceryl monostearate (GMS), palmitic acid Tween 80, tween 20, span 20, span 40, span 80, cremaphre rh 40 and sodium lauryl sulfate from were bought from Hyper-Chem. Ltd. Co., China. Poloxmer 188 was bought from Alfa Aesar (china) Chemical Co., Ltd. Poloxamer 407 (PX407) was bought from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). All other reagents and chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade.

Methods

UV absorbance spectrum maxima determination (λ max)

A stock solution of (0.1 mg/ml) was prepared by dissolving 10 mg of LX in 100 ml of distilled water and phosphate buffer pH 7.4. Then the solutions were scanned using Shimadzu-1800 (Japan) UV spectrophotometer in the range (400 to 200) nm.

Construction of calibration curve

Similar to the previously mentioned solutions, fresh solutions were prepared and serial dilutions were made and their respective absorbance values were determined at the previously established lambda max and plotted against concentration to graph the calibration curve. The R2 was calculated.

Lipid selection

Despite the absence of a universally accepted standard method for lipid selection, various approaches have been explored and reported in the literature. Various lipids were scanned (bees wax, cetyl alcohol, stearic acid, palmitic acid, GMS). An equilibrium solubility study was not attempted due to the solid nature of the selected lipids and their different melting point. Therefore, a visual method was done which included placing 1 g of the lipid in a small test tube then placed in water bath to melt the lipid with continuous stirring and at 5 °C above each lipid melting point, an accurately weighed 10 mg of LX was then added, left for 2 min until the solution is clear, then more is added until the solution was not clear anymore, the amount of LX was noted [19].

Excipient interference study

To ensure accurate results later on in the study an excipient interference study was conducted in the following manner, first a 100 ml suitable solvent was used to dissolve 10 mg the excipient (the lipids selected from the lipid selection study and the following surfactants: tween 80, tween 20, span 80, span 40, span 20, soy lecithin, chromophore rh 40, PX188, PX407), the solution was scanned at the determined lambda max to investigate the presence of UV interference. Surfactant solutions that showed no absorbance where further tested by mixing 10 ml of drug solution with known concentration and absorbance with 10 ml of excipient solution of know concentration, then the solution absorbance was determined at the previously established lambda max of LX to further verify the lack of interference.

Experimental design

A Design of Experiment (DOE) approach was employed to systematically evaluate preparation of LX-SLNs. A 3×3×2 mixed factorial design was implemented, different numbers of levels are present in a mixed-level factorial design. The DOE dependent variables included three factors-two categorical (lipid type and surfactant type) and one numerical factor (lipid to surfactant ratio). The first categorical factor consisted of three levels (three different lipids), while the second one consisted of two levels (two different surfactants) mean while the numerical factor consisted of three levels. The independent variables or responses were particle size, EE% and polydispersity index (PDI). The investigation of interactions between the design components at different levels becomes possible by this form of design. The design was analyzed using Design expert software (Version 13, Stat-ease. Inc, USA). The 3×3×2 mixed factorial design was employed since the experimental design incorporated two categorical factors (e. g., lipid type and surfactant type) and one numerical factor (e. g., lipid: surfactant ratio), each with multiple discrete levels. Given the presence of categorical variables that represent distinct qualitative classifications, experimental designs tailored for continuous factors-such as Central Composite Design (CCD) or Box-Behnken Design (BBD)-were deemed unsuitable. These designs assume continuous factor spaces and are optimized for second-order (quadratic) modeling of numerical variables, which cannot be directly applied to categorical factors. The mixed factorial design was therefore selected as it allows for the simultaneous study of both numerical and categorical factors, enabling comprehensive assessment of main effects, interaction effects, and simple effects within the experimental domain. This approach also provided an efficient balance between the number of experimental runs and the depth of information obtained, ensuring statistical robustness while maintaining practical feasibility [20]. The suggested design composed of 21 runs as shown in table 1.

Table 1: Mixed factorial design variables to formulate and prepare LX-SLNs

| Type of variable | ||||

| Independent variable | Level or category | Dependent variable | ||

| Low(-1) | Medium(0) | High(1) | ||

| X1= lipid to surfactant ratio | 1:1 | 2:1 | 3:1 | Y1 = particle size |

| X2= Lipid type | PA | GMS | SA | Y2= EE% |

| X3= surfactant type | PX188 | PX407 | Y3= PDI | |

Preparation of LX-SLNs

LX-SLNs were prepared by hot coarse emulsification followed by ultrasonication method. Briefly, the solid lipid was weighed and placed into a glass screw-cup then 10 mg of LX was weighed and added, slowly the lipid-LX mixture was heated to the lipid melting point and mixed with a magnetic bar on a magnetic hot plate to ensure that LX is homogenously mixed with the lipid. Then the hot surfactant containing aqueous solution is added and stirred at 1000 rpm for 10 min and all were maintained at 5 C above the lipid melting point. The obtained course emulsion is then sonicated for 10 min and the final volume adjusted to 10 ml due to possible water losses due to evaporation, to ensure process reproducibility, sonication was performed using a probe sonicator (Sonics Materials™ VCX-130-220) at 90% amplitude in a pulsed mode, with 50 seconds ON and 10 seconds OFF cycles, for a total duration of 10 min to facilitate efficient droplet size reduction, and ensure uniform particle distribution. The nanoemulsion was then cooled down to yield the SLNs dispersion. [21]. The lipid phase temperature was chosen based on the melting point of the lipid used in each formula, accordingly, the processing temperature was set at 5 °C above the lipid melting point, to facilitate complete lipid melting, avoid phase separation, and ensure formulation homogeneity.

Table 2: Characteristics of palmitic acid, stearic acid, and GMS as defined in

| Substance | USP definition | Melting point |

| Palmitic acid | Fatty acid mixture predominantly composed of hexadecanoic acid | Approximately 63-64 °C |

| Stearic acid | Fatty acid mixture predominantly composed of octadecanoic acid | 66–69 °C |

| GMS | Mixture of mono-and diglycerides of stearic and palmitic acids | Specification: does not melt below 55 °C |

The USP doesn’t define a specific melting point for GMS as it defines it as a mixture of mono-and diglycerides of stearic and palmitic acids, with a specification that it does not melt below 55 °C. [22]

Characterization of LX-SLNs

Particle size, PDI and EE% were measured for all of the prepared formulas. In vitro release study was conducted for 5 formulas the best formula was subsequently selected, prepared, lyophilized for further tests such as differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), powder x-ray diffraction (PXRD), fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM).

Particle morphology analysis

Particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) were measure for all of the prepared formulas using ABT-9000 NANO Laser particle size analyzer (Angstrom Advance Inc. USA). The optimized formula underwent further FE-SEM imaging.

Entrapment efficiency EE%

EE% was measure for all of the prepared formulas. Using an amico filter tube.

The following formula was used:

%EE =

In vitro release study

Pure LX and five formulas were selected for the in vitro release study, the study included using a dialysis bag release method immersed in a 250 ml of 7.4 buffer solution under 50 rpm continuous agitation and a steady temp of 37 c to mimic physiological conditions in agreement with the test specifications in the official pharmacopeia. A dialysis membrane with a molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) 12–14 kDa was used. The present study focuses on the preliminary development and characterization of LX-loaded formulations with the ultimate goal of designing an effective topical gel. Consequently, in vitro release studies were conducted under conditions relevant to topical application, employing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 to simulate the physiological environment of the skin and underlying tissues. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-way factorial ANOVA within a response surface framework using Design-Expert® software. The independent variables included formulation type (categorical) and time (numeric), while the response variable was cumulative drug release (%).

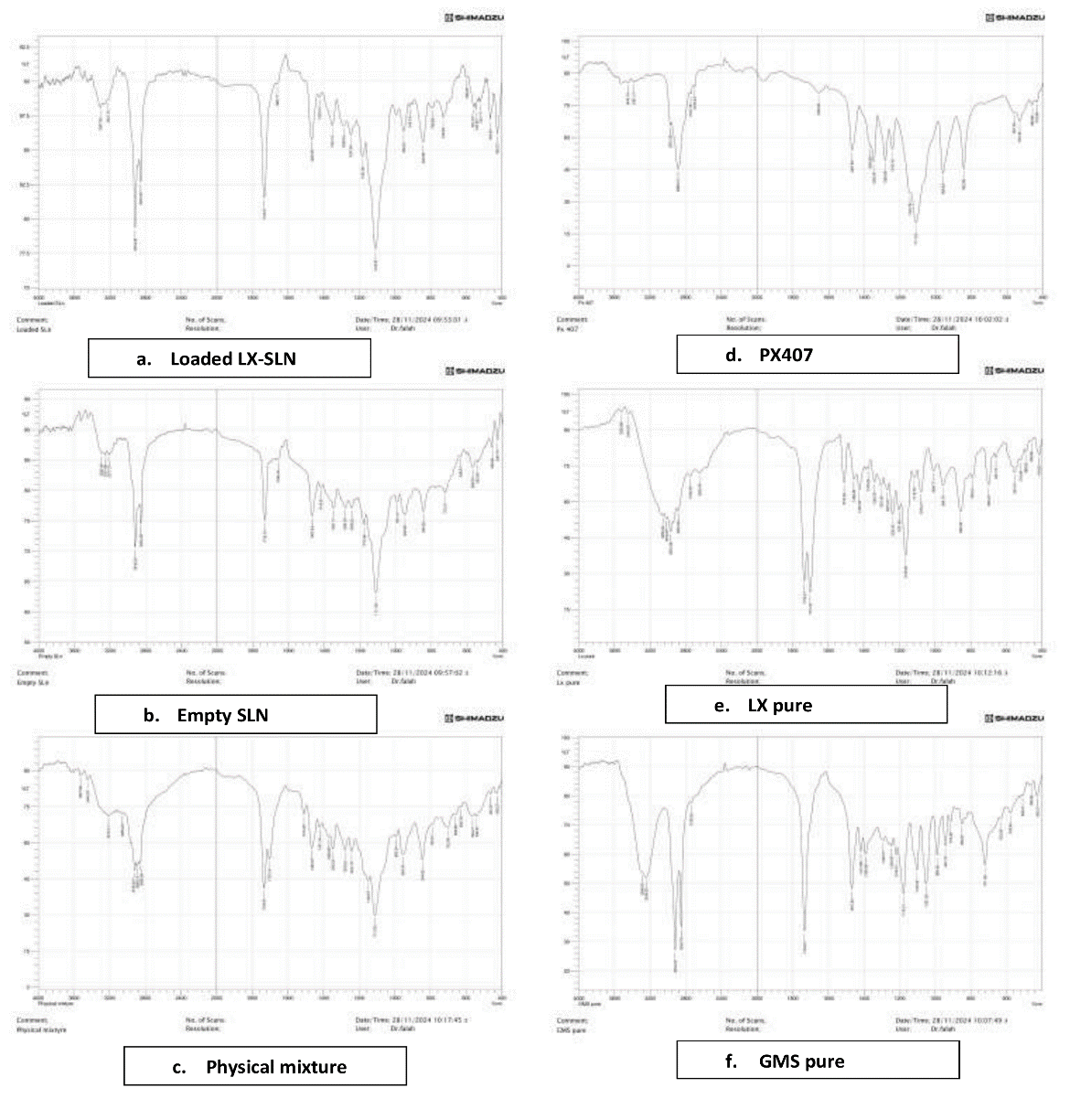

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The functional groups of pure LX, PX407, and lyophilized empty SLNs and Lx loaded SLNs optimized formulas were analyzed using FTIR (FTIR-8400S with DRS; Shimadzu) about 1 mg of each sample was mixed with 40 mg of KBr and compressed manually into a pellet using a KBr press. The pellets were then placed in the sample holder, and spectra were recorded over the 4000–400 cm⁻¹ wavelength region [23].

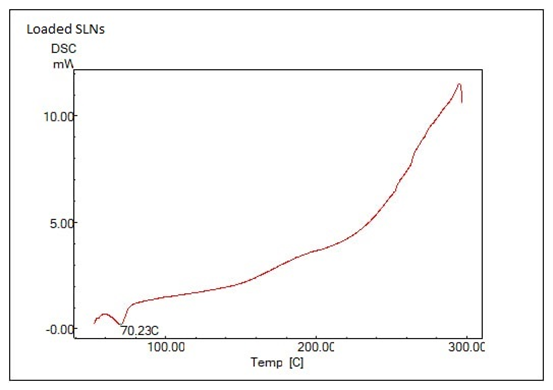

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)

PXRD is utilized to investigate the crystallinity of the pure materials used and the nanoparticles produced both empty and loaded. Five samples each of 5 mg were tested using AERIS XRD Diffractometer (Malvern, Almelo, the Netherlands).

Field emission scanning electronic microscopy (FE-SEM)

FE-SEM imaging was conducted to study the surface morphology of the optimized formula. Few drops of the optimum formula were placed on a glass slide, let to air dry, the covered with gold and viewed using InspectTM F50 (Japan). Imaging was performed under high vacuum conditions at a chamber pressure of 1.08 × 10⁻³ Pa. An accelerating voltage of 30.00 kV was applied to achieve high-resolution imaging. Images were captured at a magnification of 120,000×.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

UV absorption spectrum maxima determination (λ max)

The UV scanning of LX in, distilled water and phosphate buffer solution PBS (at pH 7.4), demonstrated a maximum absorption peak at 223 nm for both solutions, which is in agreement with the literature [18].

Construction of calibration curve

The calibration curves for LX in DW, and phosphate buffer solutions (pH 7.4) of the absorbance versus concentrations were plotted to create calibration curves. Within the tested concentration range, the curves follow Beer-Lambert's law, according to the regression coefficient R2.

Lipid selection

Although no systematic or standard protocol has been published for the selection of the best solid lipid, certain methods practical methods such as visual or apparent solubility has been reported in the published literature. Good solubility is important in order to prevent crystallization, drug expulsion, burst release and ensure efficient drug loading [24]. LX visual solubility screening revealed highest solubility in GMS, while stearic acid and palmitic acid showed relatively close solubility results but lower than GMS followed by cetyl alcohol, bees wax. These results solubility may be justified due to the molecular interaction between LX and the lipids as number of hydrogen bonding between LX and the lipid increases the solubility increases. This is in agreement with the conclusions of Yung-Chi Lee et al. [25] and Cao et al. [26]. Bees wax is a natural product that is composed of many components and overall it has a weak potential for hydrogen bonding which would justify why bees wax showed the lowest solubility. It may be also due to its highly ordered crystalline structure [27].

Drug-excipient UV interference study

The quantitative analysis of drugs using UV spectroscopy can be complicated by UV interference caused by excipients. Since many excipients absorb UV light, their absorption spectra can overlap with the drug's, making it difficult to measure the drug's concentration accurately. In order to overcome this, it is crucial to choose excipients with low or no UV absorption or to isolate the drug from interfering excipient using separation methods like HPLC. Furthermore, utilizing appropriate solvents and selection the wavelength so that the medication exhibits maximum absorbance and excipients exhibit minimal absorbance. Though HPLC is highly sophisticated analysis tool but also expensive and time consuming in comparison to UV-Vis spectroscopy. The results showed no interference with (GMS, stearic acid, palmitic acid, PX188, PX407) at 223 nm, while (tween 20, tween 80, span 20, span 40, span 80, cremaphore rh 40, SLS, soy lecithin) all showed significant interference at 223 nm, thus they were excluded from the formulation of LX-SLNs.

Experimental design

The dependent and independent variables were inputted into Design-Expert version 13 for the final design and statistical analysis of the work. Selection of the optimized formula was done using Design-Expert 13, the program selected run 13 as the optimal formulation, focusing on maximizing the EE% while achieving a particle size under 100 nm which also yielded a desirability factor of 0.792, indicating a good statistical alignment. This optimization process in Design-Expert considers various experimental variables and outcomes, balancing them to achieve the highest possible desirability score for the desired properties. With a desirability close to 0.8, the formula is well-suited for the intended parameters, suggesting it has met our work primary goals effectively.

Characterization of LX-SLNs

Particle morphology analysis

Particle size was investigated for all formulas using ABT-9000 NANO Laser particle size analyzer (Angstrom Advance Inc. USA). As this device utilizes laser diffraction technology, accurate and repeatable Particle size analysis require that the sample must be clear, bubble free, appropriately diluted and the particles to be analyzed must be suspended and well distributed in the sample. All the samples were diluted on a 1 to 10 scale using a pre-prepared room temperature surfactant solution of 0.1 w/v% PX188 for samples of runs (1 to 9) and 0.05 w/v% PX407 for samples of runs (9 to 21) under continuous stirring [19, 28]. This is done because any cloudiness or over concentrated solution would they scatter intensely leading to less reliable and reproducible data. Also Surfactant solution is used to maintain sample stability as using pure water would destabilize the particles and may lead to agglomeration and inaccurate readings [29, 30]. Controlling the Sauter mean diameter helps tailor the release profile. Due to the observed PDI ranging up to 0.3, with a significant portion of formulations displaying moderate polydispersity, the surface-area-weighted Sauter mean Diameter (D[3,2]) was regarded a better descriptor than other descriptors like the Z-average, which need a lower PDI to convey more accurate analysis [30]. This approach provides a more realistic estimation of the effective particle size influencing surface-driven properties such as dissolution, wettability, dispersion stability, encapsulation efficiency, and biological interactions [31].

Table 3: Effect of formulation factors on responses 1,2 and 3

| Run | Factor X1 | Factor X2 | Factor x3 | Response (1) | Response (2) | Response (3) |

| Lipid: surfactant ratio | Lipid type | Surfactant type | Particle size | EE% | PDI | |

| 1 | 1 | SA | PX188 | 154.3±7.2 | 86.32%±1.2 | 0.08 ±0.005 |

| 2 | 2 | SA | PX188 | 197.6±9.1 | 88.22%±0.8 | 0.09 ±0.003 |

| 3 | 3 | SA | PX188 | 286.1±17.4 | 95.19%±2.5 | 0.20±0.002 |

| 4 | 1 | GMS | PX188 | 222.8±10.3 | 88.77%±1.7 | 0.02±0.004 |

| 5 | 2 | GMS | PX188 | 636.4±15.7 | 89.98%±2.2 | 0.23±0.005 |

| 6 | 3 | GMS | PX188 | 842.2±45.6 | 93.62%±3 | 0.31±0.08 |

| 7 | 1 | PA | PX188 | 79.9±7.5 | 88.17%±1.7 | 0.11±0.02 |

| 8 | 2 | PA | PX188 | 171.3±11.4 | 89.85%±2.5 | 0.20±0.034 |

| 9 | 3 | PA | PX188 | 279.6±14.1 | 90.7%±3.2 | 0.25+0.012 |

| 10 | 1 | SA | PX407 | 317.7±4.2 | 81.77%±1.8 | 0.18±0.08 |

| 11 | 2 | SA | PX407 | 391.5±15.8 | 88.38%±2 | 0.22±0.02 |

| 12 | 3 | SA | PX407 | 419.2±22.3 | 90.11%±2 | 0.30±0.05 |

| 13 | 1 | GMS | PX407 | 70.6±4.1 | 88.07%±0.8 | 0.02±0.001 |

| 14 | 2 | GMS | PX407 | 148.8±7.6 | 88.16%±1.3 | 0.13±0.05 |

| 15 | 3 | GMS | PX407 | 263.5±19.2 | 89.54%±1.3 | 0.23±0.01 |

| 16 | 1 | PA | PX407 | 88.7±3.3 | 75.58%±2.1 | 0.01±0.008 |

| 17 | 2 | PA | PX407 | 135.2±7.7 | 84.46%±3 | 0.06±0.01 |

| 18 | 3 | PA | PX407 | 289.9±13.5 | 87.18%±4 | 0.13±0.008 |

| 19 | 1 | SA | PX407 | 322.1±7.3 | 83.19%±1.4 | 0.23±0.07 |

| 20 | 3 | GMS | PX407 | 259.4±22.8 | 88.20%±1 | 0.12±0.04 |

| 21 | 1 | GMS | PX407 | 66.8±9.2 | 89.67%±1.2 | 0.08±0.003 |

Data are represented as mean ±SD, N=3 observations.

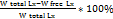

Fig. 1: Particle size distribution analysis of optimized formula by particle size analyzer ABT-9000

The particle size distribution profile of the optimized formula represented by fig. 1 in which the x-axis represents particle size in nanometers on a logarithmic scale, while the dual y-axes display cumulative percentage (Cumu%) and differential percentage (Diff%) reveals a sharp, narrow peak, indicating a uniform and monodisperse population of nanoparticles. The steep rise in the cumulative curve and the narrow differential peak reflect a highly homogeneous formula with minimal polydispersity. This distribution suggests efficient size control during formulation, which is critical for ensuring stability, reproducibility, and optimal performance. The particle size distribution analysis indicates that the production process used is highly effective in producing homogenous and uniform nanoparticles. The observed restricted size distribution highlights the precision of the process controls and the consistency kept throughout the production method. This homogeneity signifies predictable and consistent physicochemical features, which is a requirement in pharmaceutical applications, as reproducibility and predictability is essential in successful formulation. Particle size and particle size distribution can significantly affect dissolution rates, bioavailability, and formulation stability. Thus, minimal variability is paramount for ensuring dependable and consistent performance of the nanoparticles in their intended applications. A significant particle size increases were observed in Runs 5 and 6 that may be attributed to higher lipid: surfactant ratios, which promote lipid droplet fusion and increasing particle aggregation. Insufficient surfactant coverage or steric hindrance may fail to stabilize the lipid interface, resulting in larger, aggregated particles.

PDI values across the formulations indicate the degree of particle size uniformity, which is crucial for colloidal stability and consistent drug release. As depicted in table 3 PDI values ranged from as low as 0.01±0.008 (Run 16: PA with PX407 at low lipid ratio) to as high as 0.3±0.08 (Run 6: GMS with PX188 at high lipid ratio). Lower PDI values (<0.1), such as those observed in Runs 4 (0.02±0.004), 13 (0.02±0.001), and 21 (0.08±0.003), indicate highly monodisperse nanoparticle populations, which generally correlate with enhanced physical stability and predictable drug release profiles. These formulations are less prone to aggregation and sedimentation. In contrast, higher PDI values (>0.2), such as in Runs 5 (0.2±0.005), 6 (0.3±0.08), and 12 (0.3±0.05), reflect broader particle size distributions and potential aggregation, demonstrating the presence of a heterogeneous particle populations with increasing lipid: surfactant ratio. Such heterogeneity can negatively impact the stability of the formulation over time and may lead to inconsistent drug release rates due to variable particle sizes. These findings highlight the significance of optimizing lipid: surfactant ratio to achieve a balance between high EE%, desirable particle size distribution, long-term stability and consistent drug release [32].

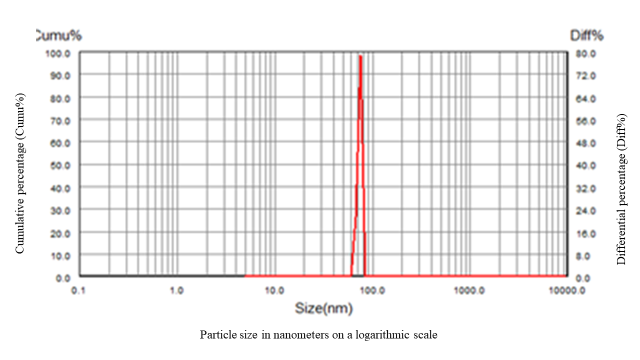

In addition, FE-SEM (InspectTM F50) imaging results confirmed the results obtained from the laser diffraction size measurements of the optimized formula. The FE-SEM images were analyzed using Fiji software. At varying magnifications, the particles exhibit a relatively uniform size distribution, with diameters measured at approximately 59 nm, and 77.0 nm. This narrow size range is optimal for achieving effective drug delivery and controlled release, as smaller particle sizes are generally associated with enhanced stability in SLNs. Morphologically, the particles display a smooth, slightly spherical structure, which is indicative of a well-formulated SLNs system. Such uniformity is critical for minimizing polydispersity and reducing the chance of aggregation, both of which are essential for ensuring long-term stability. FE-SEM also revealed a well-dispersed arrangement of particles with minimal aggregation, suggesting that the formulation process successfully prevented particle clumping, which is important to maintaining consistent drug release profiles and stability [33]. Fig. 2 show FE-SEM of optimized formula

Fig. 2: FE-SEM of the optimized formula

In vitro release study

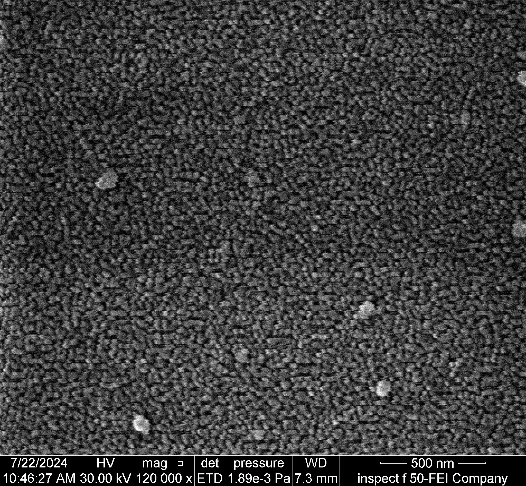

Pure LX and five formulas were selected for the in vitro release study, the study included using a dialysis bag release method to investigate the effect of lipid type and amount on drug release.

Fig. 3: % cumulative drug release vs. time profile for pure LX and various formulas, data are represented as mean ±SD, N=3 observations

Comparing the pure LX release profile to LX-SLNs formulas reveal a characteristic burst release in the case of pure LX, where a significant percentage of the drug was rapidly released within the first 60 min. This immediate release is accredited to the unencapsulated nature of the pure LX. In contrast, the LX-SLNs formulations exhibited a more sustained release pattern with minimal or no burst effect. This attenuation of the burst release is likely due to the entrapment of LX within the lipid matrix, which restricts its immediate release. This behavior of the SLNs indicates successful incorporation of the drug in the lipid matrices. The differing release profiles of LX-SLNs formulas can be rationalized based on the lipid amount and type. Formulations with increasing GMS amount resulted in a more prolonged release as increasing the lipid amount results in a denser matrix which encapsulates the drug more effectively, thus creating a more substantial physical barrier for the drug. This barrier slows down drug diffusion to the surface and results in a sustained release. In contrast, formulations with lower lipid content, such as GMS 1:1, tend to have a looser matrix structure, allowing the drug to diffuse more quickly and resulting in a faster release. Furthermore, if we compare the different lipid types GMS, stearic acid, palmitic acid, then a trend also is obvious that palmitic and stearic acid-based SLNs have been shown to release drugs more rapidly than GMS-based SLNs. This may be attributed to first the greater LX solubility in GMS than in palmitic acid and stearic acid, second GMS structure is different in having a glyceryl backbone, while stearic acid and palmitic acid are straight-chain fatty acids this difference in molecular structure could lead to reduced lipid mobility thus hindering the diffusion of Lx out of the GMS-based SLNs. similar rationalization applies as to why palmitic-based SLNs showed faster release profile, palmitic acid(16-c) is two carbon atoms shorter than stearic acid (c-18), thus palmitic acid create less dense matrices. These matrices have less molecular order and greater mobility, allowing the drug to diffuse more readily, which explains the faster release profiles observed for palmitic acid in comparison to stearic acid [34]. Furthermore, various kinetic models-including Zero-order, First-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer–Peppas, and Hixson–Crowell-were applied to the in vitro release data using DD-Solver®, an add-in tool for Microsoft® Excel, to determine the best-fit model describing the drug release behavior, which was determined by finding the R2 value for each kinetic model. The Statistical analysis results which was performed using a two-way factorial ANOVA using Design-Expert 13® software in which the independent variables included formulation type (categorical) and time (numeric), while the response variable was cumulative drug release (%) revealed an significantly high model F-value (F = 2842.12, p<0.0001), indicating that the tested model captured a substantial portion of the variability in drug release across the examined formulations and time points and that the differences in drug release profiles statistically significant and not due to random variation. This strongly suggests that formulation composition had statistically significant effect on the release behavior.

Table 4: Best-fit kinetic models with mechanism interpretation

| Formulation | Best-fit model | R² value | Mechanism interpretation |

| Pure LX | Hixson-Crowell | 0.9875 | Surface-area dependent release (erosion-controlled) |

| Palmitic 3:1 | First-order | 0.9971 | Concentration-dependent release |

| GMS 1:1 | First-order | 0.9958 | Concentration-dependent release |

| Stearic 3:1 | First-order | 0.9745 | Moderate fit; likely involves complex or mixed mechanisms |

| GMS 2:1 | Korsmeyer-Peppas | 0.9816 | Diffusion-controlled release (possibly Fickian) |

| GMS 3:1 | Korsmeyer-Peppas | 0.9831 | Diffusion-controlled release (possibly Fickian) |

Fig. 4: FTIR spectra a) Loaded LX-SLNs, b) Empty SLNs, c) Physical mixture, d) PX407, e) Pure LX, f) GMS pure

FTIR

The FTIR results illustrated in fig. 4 confirm the lack of chemical interaction between the components as the FTIR spectra of the optimized LX formula displayed nearly all distinctive peaks of LX, GMS and PX407 without significant shifts in peak positions, indicating no chemical interactions. This analysis suggests that the excipients in the SLNs of LX are compatible.

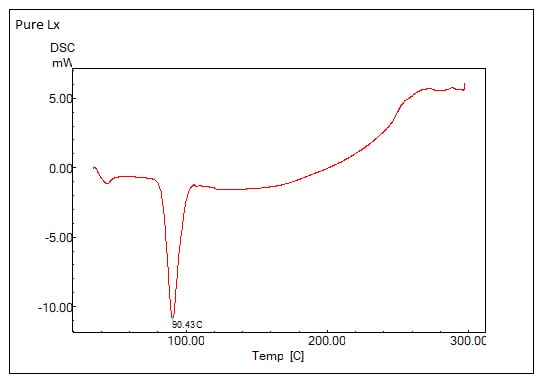

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The DSC thermograms for Loaded SLNs and Pure LX are shown in fig. 5 reveal key differences that highlight the effects of encapsulation on the thermal properties of SLNsb. In Pure LX thermogram, a sharp endothermic peak at 90.43 °C, indicating a stable, crystalline structure with a well-defined melting point. This peak is characteristic of Pure LX, where crystallinity is maintained. However, the LX-SLNs thermogram lacks this distinct melting peak at 90.43 °C, the disappearance of the LX-specific peak suggest that drug loading disrupts the crystalline structure of LX, possibly creating a more amorphous or mixed-phase matrix.

XRD

Raw material powder and lyophilized formulas were used for powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis using (AERIS XRD Diffractometer, Malvern, Almelo, The Netherlands) to evaluate the physical changes of transforming the raw material to nanomaterial. Six samples were examined and the results are graphed in fig. 6.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the individual components (GMS, LX, and PX407) show distinctive sharp peaks at specific 2θ angles, indicating their crystalline nature. GMS exhibits characteristic peaks around 19-22°, while LX has additional crystalline peaks around 30°, aligning with published data on these components' crystalline forms [35]. PX407 has prominent peaks around 20-22 degrees, indicating a semi-crystalline structure also in agreement with published data [21]. In contrast, the XRD patterns for both Loaded SLNs and Empty SLNs display broad halos between 10 and 30° 2θ, with the absence of sharp, intense peaks. This suggests that the SLNs formulation component may have transitioned to an amorphous state, losing the ordered crystalline structure of their individual components. Those findings support the findings previously demonstrated by the DSC where the melt point of LX peak disappeared in the LX-SLNs.

(A) Pure LX

(B) Optimized LX SLNs formula

Fig. 5: DSC thermograms of: (A) pure LX and (B) Optimized LX SLNs formula

Fig. 6: Powder X-ray diffractograms of LX, GMS, PX407, empty SLNs, optimized loaded LX-SLNs. Distinct crystalline peaks were observed for GMS in the range of 19°–22° 2θ, indicative of its polymorphic crystalline structure. The disappearance or broadening of these peaks in the SLNs formulation suggests a transition toward an amorphous or less-ordered state, likely due to nanoparticle formation and molecular dispersion of the drug within the lipid matrix

CONCLUSION

Firstly, The authors conclude that Hot melt emulsification followed with probe Sonication, is a fast, convenient, and efficient method to create SLNs without using organic solvents that may add cost or be of hazardous nature to the researcher or the environment [36]. Secondly, LX, a nonsteroidal propionic acid derivative, can be successfully loaded into SLNs made of stearic acid, palmitic and GMS type of lipid with PX188 and PX407 as surfactants. This shows the highly customizable nature of SLNs preparations alongside their biocompatibility and availability of the formulation lipids due to their natural sources and well known profile. The characteristics of the prepared SLNs-particularly the nanoscale particle size and sustained drug release profile-suggest the potential for improved oral bioavailability and reduced dosing frequency, which are key benefits in a clinical context. However, the study has certain limitations. Notably, in vivo studies to validate the pharmacokinetic performance and therapeutic efficacy of the SLNs were not conducted. Additionally, challenges related to process scalability, long-term stability, and batch-to-batch reproducibility must be addressed in future work to ensure compliance with regulatory standards and support potential clinical translation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the department of pharmaceutics and the faculty of pharmacy at the University of Kufa for providing the necessary facilities for the successful completion of this work.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed equally to the development and execution of this research. Each author was actively and equally involved in the conceptualization, data acquisition, analysis, and manuscript. The final manuscript has been thoroughly reviewed and approved by all authors prior to publication.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Vargason AM, Anselmo AC, Mitragotri S. The evolution of commercial drug delivery technologies. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5(9):951-67. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00698-w, PMID 33795852.

Mekuye B, Abera B. Nanomaterials: an overview of synthesis classification, characterization and applications. Nano Select. 2023;4(8):486-501. doi: 10.1002/nano.202300038.

Areej W, Alhagiesa MM. Formulation and characterization of nimodipine nanoparticles for the enhancement of solubility and dissolution rate. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2021;30(2):10. doi 10.31351/vol30iss2pp143-152.

Scioli Montoto S, Muraca G, Ruiz ME. Solid lipid nanoparticles for drug delivery: pharmacological and biopharmaceutical aspects. Front Mol Biosci. 2020 Oct 30;7:587997. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.587997, PMID 33195435.

Pham CV, Van MC, Thi HP, Thanh CD, Ngoc BT, Van BN. Development of ibuprofen-loaded solid lipid nanoparticle-based hydrogels for enhanced in vitro dermal permeation and in vivo topical anti-inflammatory activity. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020 Jun;57:101758. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.101758.

Ajaana SSA. Enhancing the loading capacity of kojic acid dipalmitate in liposomes. Lat Am J Pharm. 2020;39(7):1333-9.

Mohammad HA, MMG, Mohammd Akrami, Ameer Sabah Sahib. Design and characterization of tacrolimus monohydrate-loaded core-shell lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticle. J Complement Med Res. 2020;11(5):11.

Wannas AN, Abdul Hasan MT, Mohammed Jawad KK, Razzaq IF. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of SELF-NANO emulsifying drug delivery systems of ketoprofen. Int J Appl Pharm. 2023;15(3):71-9. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i3.46892.

Stanisic D, Costa AF, Cruz G, Duran N, Tasic L. Applications of flavonoids with an emphasis on hesperidin as anticancer prodrugs: phytotherapy as an alternative to chemotherapy. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry. 2018;58:161-212. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-64056-7.00006-4.

Mohammed HA, Khan RA, Singh V, Yusuf M, Akhtar N, Sulaiman GM. Solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted natural and synthetic drugs delivery in high incidence cancers and other diseases: roles of preparation methods lipid composition, transitional stability and release profiles in nanocarriers development. Nanotechnol Rev. 2023;12(1):20220517. doi: 10.1515/ntrev-2022-0517.

OPA, ND, Gidwani B. Optimization characterization and in vivo study of rivastigmine tartrate nanoparticles by using 22 full factorial design for oral delivery. Int J Appl Pharm. 2023;15(3):80-9. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i3.47140.

Dara T, Vatanara A, Nabi Meybodi M, Vakilinezhad MA, Malvajerd SS, Vakhshiteh F. Erythropoietin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles: preparation optimization and in vivo evaluation. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019 Jun 1;178:307-16. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.01.027, PMID 30878805.

Phalak SD, Bodke V, Yadav R, Pandav S, Ranaware M. A systematic review on nano drug delivery system: solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN). Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2024;16(1):10-20. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2024v16i1.4020.

S KS, G Rana D. Possible influence of loxoprofen in lipopolysaccharide-induced alterations in sucrose intake in chronic mild stress model in mice. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2021;14(7):99-101.

Peneva PT. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for topical ophthalmic administration: contemporary trends. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(9):13-9.

Hamza MY, Abd El Aziz ZR, Aly Kassem M, El Nabarawi MA. Loxoprofen nanosponges: formulation characterization and ex-vivo study. Int J Appl Pharm. 2022;14(2):233-41. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2022v14i2.43670.

Zaman M, Akhtar F, Baseer A, Hasan SM, Aman W, Khan A. Formulation development and in vitro evaluation of gastroretentive drug delivery system of loxoprofen sodium: a natural excipients-based approach. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2021;34(1):57-63. PMID 34248003.

Tak JW, Gupta B, Thapa RK, Woo KB, Kim SY, Go TG. Preparation and optimization of immediate release/sustained-release bilayered tablets of loxoprofen using box-behnken design. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2017;18(4):1125-34. doi: 10.1208/s12249-016-0580-5, PMID 27401334.

Nandgude T, PS P, VC P. Solid lipid nanoparticle-based gel to enhance topical delivery for acne treatment. Int J Drug Deliv Technol. 2022;13(2):474-82.

Arteaga Cabrera E, Ramirez Marquez C, Sanchez Ramirez E, Segovia Hernandez JG, Osorio Mora O, Gomez Salazar JA. Advancing optimization strategies in the food industry: from traditional approaches to multi-objective and technology-integrated solutions. Appl Sci. 2025;15(7). doi: 10.3390/app15073846.

Das S, Ng WK, Kanaujia P, Kim S, Tan RB. Formulation design preparation and physicochemical characterizations of solid lipid nanoparticles containing a hydrophobic drug: effects of process variables. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2011;88(1):483-9. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.07.036, PMID 21831615.

Rowe RC, Sheskey PJ, Owen SC. Handbook of pharmaceutical excipients. Vols. 308-10. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2006. p. 501-2, 739.

Shrimal P, Jadeja G, Naik J, Patel S. Continuous microchannel precipitation to enhance the solubility of telmisartan with poloxamer 407 using box-behnken design approach. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2019;53:101225. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101225.

Shah M, Agrawal Y. High throughput screening: an in silico solubility parameter approach for lipids and solvents in SLN preparations. Pharm Dev Technol. 2013;18(3):582-90. doi: 10.3109/10837450.2011.635150, PMID 22107345.

Lee YC, Dalton C, Regler B, Harris D. Drug solubility in fatty acids as a formulation design approach for lipid-based formulations: a technical note. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2018;44(9):1551-6. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2018.1483395, PMID 29873584.

Cao Y, Marra M, Anderson BD. Predictive relationships for the effects of triglyceride ester concentration and water uptake on solubility and partitioning of small molecules into lipid vehicles. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93(11):2768-79. doi: 10.1002/jps.20126, PMID 15389678.

Alwani S, Wasan EK, Badea I. Solid lipid nanoparticles for pulmonary delivery of biopharmaceuticals: a review of opportunities challenges and delivery applications. Mol Pharm. 2024;21(7):3084-102. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.4c00128, PMID 38828798.

Yin J, Xiang C, Wang P, Yin Y, Hou Y. Biocompatible nanoemulsions based on hemp oil and less surfactants for oral delivery of baicalein with enhanced bioavailability. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017 Apr 10;12:2923-31. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S131167, PMID 28435268, PMCID PMC5391827.

Farrell E, Brousseau JL. Guide for DLS sample preparation; 2025. p. 1-3.

Chemical instrumentation F. Particle characterization guide; 1990.

Alhagiesa A, Ghareeb M. Formulation and evaluation of nimodipine nanoparticles incorporated within orodispersible tablets. International Journal of Drug Delivery Technology. 2020;10(4):547-52. doi: 10.25258/ijddt.10.4.7.

Danaei M, Dehghankhold M, Ataei S, Hasanzadeh Davarani F, Javanmard R, Dokhani A. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(2):57. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10020057, PMID 29783687.

Mehta M, Bui TA, Yang X, Aksoy Y, Goldys EM, Deng W. Lipid-based nanoparticles for drug/gene delivery: an overview of the production techniques and difficulties encountered in their industrial development. ACS Mater Au. 2023;3(6):600-19. doi: 10.1021/acsmaterialsau.3c00032, PMID 38089666.

Xie S, Zhu L, Dong Z, Wang X, Wang Y, Li X. Preparation characterization and pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles: influences of fatty acids. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2011;83(2):382-7. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.12.014, PMID 21215599.

Khezri K, Saeedi M, Morteza Semnani K, Akbari J, Hedayatizadeh Omran A. A promising and effective platform for delivering hydrophilic depigmenting agents in the treatment of cutaneous hyperpigmentation: kojic acid nanostructured lipid carrier. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2021;49(1):38-47. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2020.1865993, PMID 33438443.

Khairnar SV, Pagare P, Thakre A, Nambiar AR, Junnuthula V, Abraham MC. Review on the scale-up methods for the preparation of solid lipid nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(9):1886. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14091886, PMID 36145632.