Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 436-443Original Article

MOLECULAR DOCKING AND ADMET PROPERTIES OF NOVEL 5-METHYL-6AH-BENZO [4, 5] OXAZOLO [3,2-A]QUINOLIN-2-OL DERIVATIVES FOR THEIR ANTI-CANCER ACTIVITY

SIMPI MEHTA1*, POONAM KASWAN2*, POOJA RANJAN3, SUDESH4

¹DPG Institute of Technology and Management, Gurgaon-122004, India. ²AISSMS Institute of Information Technology, Pune, India. ³Department of Chemistry, Hindu Girls College, Sonipat-131001, India. ⁴Department of Chemistry, Research Scholar, Baba Mast Nath University, Rohtak-124001, India

*Corresponding author: Simpi Mehta; *Email: simpimehta@gmail.com

Received: 07 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 01 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to design and evaluate a series of novel 5-Methyl-6aH-benzo [4,5]oxazolo [3,2-a]quinolin-2-ol derivatives as potential anticancer agents targeting the human amine oxidase (AO) enzyme.

Methods: Seventeen oxazole-based ligands were designed and subjected to molecular docking simulations using the crystallographic structure of human AO (PDB ID: 2v5z). GlideScore was used to assess binding affinity, and key molecular interactions were analyzed. Additionally, ADME-Toxicity properties were predicted to evaluate pharmacokinetic and safety profiles.

Results: Among the ligands, compounds 8 and 10 demonstrated the highest binding affinities, with GlideScores of –10.219 and –10.461 kcal/mol, respectively, significantly better than the reference drug R-(–)-Deprenyl (–6.205 kcal/mol). These ligands exhibited strong hydrophobic and π–π stacking interactions with active site residues PHE168, TRP119, and TYR435, indicating stable binding. ADME-Toxicity analysis revealed that all designed ligands had favorable pharmacokinetic profiles, including high oral absorption, low predicted toxicity, and acceptable blood-brain barrier permeability.

Conclusion: The results highlight the therapeutic potential of oxazole derivatives as effective scaffolds for developing new anticancer agents targeting amine oxidase, with compounds 8 and 10 emerging as promising lead candidates.

Keywords: Benzo [4, 5]oxazolo [3,2-a]Quinolin-2-ol amine oxidase (AO), Molecular docking, Anticancer agents, Glide score, 2v5z, π–π stacking interactions, Hydrogen bonding, ADMET prediction, In silico drug design, Deprenyl, Biogenic amine deamination, Structure-based drug design (SBDD), Tumor progression, Pharmacokinetics

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54488 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Amine oxidases (AOs) catalyze the oxidative deamination of amines, generating aldehydes, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby influencing cellular processes, and among them, monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A)-a mitochondrial flavoprotein-plays a critical role in prostate cancer progression by promoting ROS production, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), and tumor growth, making it a promising therapeutic target for inhibition [1-5]. Dysregulation of monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) has been extensively linked to various pathologies, including neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety-where its hyperactivity disrupts neurotransmitter balance-as well as neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, and cardiovascular conditions, including myocardial injury and heart failure [6-9]. In the context of cancer biology, particularly prostate cancer, elevated MAO-A activity has been associated with increased ROS production, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), and tumor progression. Inhibition of MAO-A has shown therapeutic promise in limiting tumor growth and metastasis [10, 11]. Within this framework, 5-Methyl-6aH-benzo [4,5]oxazolo [3,2-a]quinolin-2-ol has emerged as a potential anticancer agent. Its fused tricyclic aromatic core promotes π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding within the MAO-A active site. Molecular docking studies predict a favorable binding orientation, suggesting effective inhibition of MAO-A by occupying the catalytic site and disrupting its enzymatic function [12-17]. Recent studies highlight the emerging role of MAO-A in cancer, particularly in prostate cancer (PC), one of the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancers and a leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men [18-20]. Elevated MAO-A expression in prostate tumors correlates with higher Gleason grades and poor differentiation, suggesting its involvement in cancer progression and metastasis [21-25]. Overexpressed MAO-A has been shown to suppress E-cadherin and upregulate vimentin and Twist, driving epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and contributing to metastasis [23-25]. Moreover, MAO-A upregulation has been linked to resistance against androgen deprivation and antiandrogen therapies in prostate cancer, indicating its role in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [26-28]. MAO-A mediates resistance by regulating neuroendocrine differentiation through pathways involving GR (Glucocorticoid Receptor) activation and relieving REST transcriptional suppression, which promotes cell survival via autophagy while inhibiting apoptosis [29]. Contrastingly, studies on hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cholangiocarcinoma reveal inconsistent roles for MAO-A, emphasizing the complexity of its function in cancer biology [30-33]. Nonetheless, MAO-A’s involvement in tumor progression, therapy resistance, and regulation of prostate epithelial cell growth makes it a promising target for cancer therapy [23, 25, 34, 35]. In particular, repurposing clinically available MAO inhibitors (MAOIs) offers a potential strategy for treating prostate cancer, with preclinical and clinical data supporting their efficacy [36-38]. Additionally, benzoxazole-containing compounds have demonstrated significant anticancer activities across various cell lines [39-42]. Novel compounds integrating benzoxazole moieties with quinoline frameworks have exhibited promising antitumor effects, further underscoring their potential in cancer treatment [42-45]. Together, these findings position MAO-A and its inhibitors as key targets for advancing therapeutic strategies against cancer, particularly for aggressive and treatment-resistant forms like CRPC [46-48].

The benzo [d]oxazole nucleus, a privileged heterocycle incorporating both nitrogen and oxygen within a fused aromatic system, is known for its metabolic stability, binding affinity, and broad bioactivity, including anticancer effects. Its planar aromatic nature enhances π–π stacking within enzyme binding pockets, while its modular structure enables systematic substitution to optimize potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties [49-51].

Altogether, these features make benzo [d]oxazolo derivatives compelling candidates for the development of novel MAO-A inhibitors with potential therapeutic applications in prostate cancer.

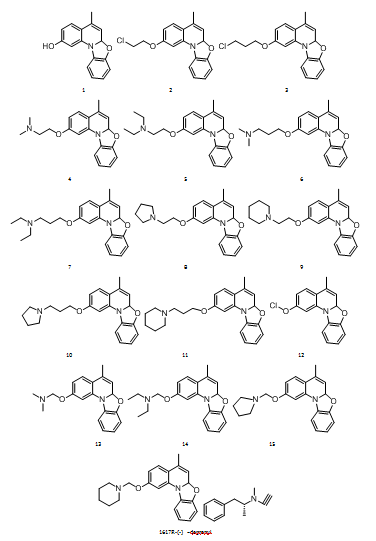

Fig. 1: Structures of docked ligands and reference compound

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Software and computational tools

All computational studies were carried out using the Schrödinger Suite 2021-4 (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, USA) [52, 53]. The following modules were employed: Maestro (for molecular visualization), LigPrep (for ligand preparation), Protein Preparation Wizard (for receptor preprocessing), Glide (for molecular docking), Receptor Grid Generation, and QikProp (for ADME/T predictions). Calculations were performed on a system running Windows 10 with Intel® Core™ i7 processor and 16 GB RAM.

Ligand preparation

A set of 17 ligands, including sixteen benzo [4, 5]oxazolo derivatives(compounds 8, 10) and the reference compound R-(–)-deprenyl, were constructed using ChemDraw Ultra 12.0. These structures were imported into Maestro, and geometry optimization was performed using LigPrep with the OPLS4 force field. Ligands were desalted, tautomers and stereoisomers were generated, and ionization states were predicted using Epik at pH 7.0±2.0.

Protein preparation

The crystal structures of human amine oxidase (PDB IDs: 2v5z, 2v60, and 2v61) were obtained from the PDB (Protein Data Bank) (https://www.rcsb.org/) [54-56]. These protein structures were subsequently refined using the Protein Preparation Wizard in the Glide module. The preparation process involved several critical steps to ensure structural accuracy for further computational studies. Hydrogen atoms were added to the structures, and side chains distant from the active site or not participating in salt-bridge formation were neutralized. Crystallographic water molecules were removed, and appropriate protonation states and tautomeric forms of histidine residues were assigned. Additionally, the positions of hydroxyl and thiol hydrogen atoms were optimized, and the correct rotameric forms of Asn, Gln, and His residues were selected. Following these modifications, energy minimization was performed using the OPLS-2005 force field to ensure a stable and energetically favorable conformation of the protein structures. These PDB entries represent monoamine oxidase (MAO) isoforms with known co-crystallized inhibitors, suitable resolutions, and relevance to MAO-A inhibition.

Receptor grid generation

For docking simulations, the binding site was defined using the centroid of the co-crystallized ligand or active site residues. A receptor grid was generated using the Receptor Grid Generation module with default parameters and grid box coordinates X = 10.869, Y = –9.290, Z = 9.489. Water molecules were excluded, and no constraints were applied during grid setup.

Molecular docking simulation

Molecular docking was performed using the Glide XP (Extra Precision) mode with flexible ligand sampling (up to 100 poses per ligand) and the OPLS-2005 force field to ensure high-accuracy predictions. Docking poses were evaluated using GlideScore, Glide Energy, and Emodel Energy. GlideScore, an empirical estimate of binding affinity, considers van der Waals and electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonds, lipophilic contacts, and structural penalties or rewards. The best pose for each ligand was selected based on the lowest GlideScore and favorable interactions with active site residues.

ADMET prediction

Pharmacokinetic and ADMET properties were predicted using the QikProp module. The following parameters were evaluated.

Table 1: Predicted ADMET parameters and acceptable ranges

| Parameter | Description | Acceptable range |

| WPSA | Weakly polar surface area | 0.0–175.0 |

| Volume | Total solvent-accessible volume (ų) | 500.0–2000.0 |

| Donor HB | Number of hydrogen bond donors | 0.0–6.0 |

| Acceptor HB | Number of hydrogen bond acceptors | 2.0–20.0 |

| QPlogS | Aqueous solubility (mol/dm³) | –6.5 to 0.5 |

| QPlogHERG | Predicted IC₅₀(Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration) for HERG K⁺ channel blockage | <–5 |

| QPPCaco | Caco-2 cell permeability (nm/sec) | >500 |

| QPlogBB | Logarithm of Brain/Blood Partition Coefficient | –3.0 to 1.2 |

| QPPMDCK | MDCK cell permeability (nm/sec) | >500 |

| QPlogKp | Logarithm of Skin Permeability | –8.0 to –1.0 |

| Human Oral Absorption | Estimated percentage of oral absorption | >80% (High) |

| Lipinski’s Violations | Number of violations of Lipinski’s Rule of Five | Minimal preferred |

These descriptors aided in assessing drug-likeness and the potential of the compounds as orally bioavailable antibacterial agents.

Visualization and binding analysis

The binding poses and molecular interactions between ligands and the amine oxidase active site were visualized using Pose Viewer and 2D Interaction Diagrams in Maestro. Hydrogen bonds, π–π stacking, and hydrophobic contacts were examined. Superposition of docked poses was performed to compare the binding mode and orientation of structurally related compounds [56-58].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Molecular docking simulations

Molecular docking simulations were conducted to assess the binding interactions of a designed library of 17 ligands with three crystallographic structures of the amine oxidase enzyme (PDB IDs: 2v5z, 2v60, and 2v61). The docking scores revealed favorable binding affinities, with ranges of –7.148 to –10.461 for 2v5z, –3.04 to –4.79 for 2v60, and –9.576 for 2v61. Corresponding binding energies (in kcal/mol) were observed within the ranges of –8.837 to –27.538 for 2v5z, –27.022 to –30.816 for 2v60, and –20.611 for 2v61. A detailed listing of docking scores and binding energies for ligands 1–16 and the reference compound R-(–)-deprenyl (ligand 17) is presented in table 1, while graphical representations for docking scores and binding energies specific to 2v5z are shown in fig. 2 and 3, respectively. Further molecular interaction parameters were analyzed, including potential energy (OPLS-2005: 122.486 to 245.665), Glide hydrogen bonding energy (Glide Hbond: 0 to –0.697), van der Waals energy (Glide EVDW: –6.213 to –44.356), and Coulombic energy (Glide ECoul: –0.015 to –8.431). These results, detailed in table 2, indicate strong and favorable ligand–protein interactions, particularly for ligands exhibiting substantial van der Waals and electrostatic contributions.

Molecular docking energy evaluation

Further analysis focused on the binding interactions of the 17 ligands with amine oxidase (PDB: 2v5z) using the Glide module (Schrödinger) with the OPLS-2005 force field. Key docking parameters are summarized in table 2.

Table 2: Docking scores of ligand1-16 and reference compound R-(-) –deprenyl with protein amine oxidase

| S. No. | Protein name | PDB | Ligand No. | Potential energy (OPLS-2005) | Docking Score | Glide Hbond | Glide EVDW | Glide ECoul | Glide energy |

| 1 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 1 | 122.486 | -9.679 | -0.7 | -26.019 | -1.519 | -27.538 |

| 2 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 2 | 136.114 | -9.523 | 0 | -22.626 | 0.568 | -22.058 |

| 3 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 3 | 136.814 | -9.801 | 0 | -25.21 | 1.201 | -24.009 |

| 4 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 4 | 167.127 | -9.609 | 0 | -18.431 | 2.629 | -15.802 |

| 5 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 5 | 173.213 | -8.12 | 0 | -22.998 | 2.046 | -20.952 |

| 6 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 6 | 159.544 | -7.148 | 0 | -16.802 | 2.635 | -14.168 |

| 7 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 7 | 177.254 | -7.291 | 0 | -21.802 | 3.089 | -18.713 |

| 8 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 8 | 245.665 | -10.219 | 0 | -17.492 | 2.35 | -15.142 |

| 9 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 9 | 204.574 | -7.728 | 0 | -19.4 | 2.332 | -17.068 |

| 10 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 10 | 239.395 | -10.461 | 0 | -22.248 | 2.564 | -19.685 |

| 11 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 11 | 197.629 | -7.434 | 0 | -19.395 | 3.053 | -16.342 |

| 12 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 12 | 135.323 | -7.783 | 0 | -9.643 | 0.806 | -8.837 |

| 13 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 13 | 140.921 | -9.13 | 0 | -16.166 | 2.048 | -14.118 |

| 14 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 14 | 154.112 | -9.734 | 0 | -18.602 | 2.191 | -16.411 |

| 15 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 15 | 215.576 | -7.353 | 0 | -20.603 | 2.208 | -18.394 |

| 16 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 16 | 178.869 | -7.586 | 0 | -20.187 | 2.464 | -17.723 |

| *17 | Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 17 | 61.176 | -6.412 | 0 | -23.761 | -1.307 | -25.068 |

Among all ligands, Ligand 10 exhibited the most favorable docking score (–10.461), alongside a significant Glide energy (–19.685 kcal/mol), attributed to robust van der Waals and electrostatic interactions. Ligand 8 followed closely with a docking score of –10.219; however, its high potential energy (245.665 kcal/mol) indicates possible conformational changes upon binding. Ligand 3 also displayed a strong docking score (–9.801) and substantial Glide energy (–24.009), driven by strong van der Waals forces. Notably, Ligand 1 displayed one of the most negative Glide energies (–27.538), indicating highly favorable binding interactions. It also showed the only significant hydrogen bond contribution (–0.7), suggesting specific H-bond interactions with active site residues, potentially enhancing selectivity and stability. In contrast, the reference compound Ligand 17 yielded the weakest performance (docking score –6.412; Glide energy –25.068), implying poor fit or unfavorable electrostatic compatibility within the binding pocket. Ligands 6, 7, 11, 15, and 16 presented moderately unfavorable profiles, with docking scores between –7.1 to –7.7. These findings indicate that Ligands 10, 8, 3, and 1 exhibit the most promising binding affinities and interaction energies. While Ligand 10 balances docking affinity and energy optimally, Ligand 1 demonstrates selective hydrogen bonding, and Ligand 8 suggests possible induced fit upon binding. These insights support the potential of these ligands for further in vitro and in vivo validation, with Ligand 17 considered unsuitable for further development due to weak binding affinity.

Pharmacokinetic (ADME/) predictions

ADME/T profiling was conducted using the QikProp module to predict pharmacokinetic behavior, including water solubility (QPlogS), Logarithm of Brain/Blood Partition Coefficient (QPlogBB), Predicted Permeability of Caco-2 Cells (QPPCaco), and human oral absorption. The results are provided in table 3. Most ligands demonstrated excellent predicted oral absorption (100%) and compliance with Lipinski’s Rule of Five, indicating good drug-likeness. Notably, Ligands 2, 3, 5, 10, 13–16 passed all essential criteria. Ligand 17, while showing high oral absorption, had a high number of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, violating the rule of five and possibly contributing to its poor binding. Table 3 summarizes the ADME/T and pharmacological profiles of selected ligands and reference compounds predicted using QikProp. Most ligands show favorable absorption characteristics, with 100% predicted human oral absorption. Ligands such as 2 and 3 exhibit high Caco-2 and MDCK(Madin-Darby Canine Kidney) permeability, suggesting good intestinal absorption and blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration. Ligands 10, 14, and 16 show moderate permeability and acceptable predicted logBB values, indicating potential CNS activity. Ligand 17, although distinct in structure (notably with 4 H-bond donors and 11.1 acceptors), shows significantly lower Permeability of MDCK Cells (QPPCaco: 48.54; QPPMDCK: 24.66) and a high logBB (2.44), suggesting limited oral bioavailability but high CNS penetration potential. Most ligands follow Lipinski’s Rule of Five, indicating drug-likeness, though the high logHERG blockade values in some cases (e. g., ligand 10: –6.928) warrant caution due to potential cardiotoxicity.

Receptor interaction analysis

Ligands 8 and 10, which showed top docking performance, were further analyzed for their interaction profiles within 4 Å of the active site residues (table 4). Both ligands formed extensive hydrophobic contacts with residues such as Leu164, Leu167, Ile316, and Phe168, and π–π stacking with aromatic residues like Tyr326, Tyr60, and Phe343. Ligand 1 exhibited specific hydrogen bonding with Gln206, further supporting its strong binding stability.

Table 3: ADME/T and pharmacological parameters prediction for the ligands and the reference compounds using QikProp

| S. No. | WPSA | Volume | Donor HB | AcceptHB | QPlogS | QPlogHERG | QPPCaco | QPlogBB | QPPMDCK | QPlogKp | Percent human oral absorption | Rule of five |

| 1 | 0 | 800.706 | 1 | 1.5 | -7.1 | -4.827 | 287.911 | 0.023 | 1549.062 | -1.382 | 100 | 0 |

| 2 | 73.485 | 967.511 | 0 | 1.5 | -9.1 | -4.486 | 9450.506 | 0.603 | 100 | -0.328 | 100 | 1 |

| 3 | 73.346 | 1029.073 | 0 | 1.5 | -8.5 | -5.722 | 94.188 | 0.542 | 10000 | -0.233 | 100 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 | 1214.651 | 0 | 3.5 | -8.3 | -3.85 | 234.545 | 0.571 | 1362.065 | -0.082 | 100 | 1 |

| 10 | 0 | 1215.674 | 0 | 3.5 | -5.4 | -6.928 | 217.901 | 0.594 | 1250.541 | -2.184 | 100 | 1 |

| 13 | 0 | 1017.551 | 0 | 3.5 | -3.7 | -6.237 | 192.306 | 0.684 | 1140.412 | -0.456 | 100 | 0 |

| 14 | 0 | 1126.766 | 0 | 3.5 | -4.4 | -6.418 | 229.99 | 0.629 | 1346.519 | -2.163 | 100 | 0 |

| 15 | 0 | 1096.073 | 0 | 3.5 | -4.2 | -6.186 | 209.223 | 0.71 | 1213.656 | -0.381 | 100 | 0 |

| 16 | 0 | 1139.339 | 0 | 3.5 | -4.9 | -6.557 | 2169.153 | 0.722 | 1263.92 | -2.376 | 100 | 0 |

| *17 | 21.52 | 1140.31 | 4 | 11.1 | -3.79 | -5.08 | 48.54 | 2.44 | 24.66 | -0.29 | 100 | 0 |

Predicted interaction with receptors

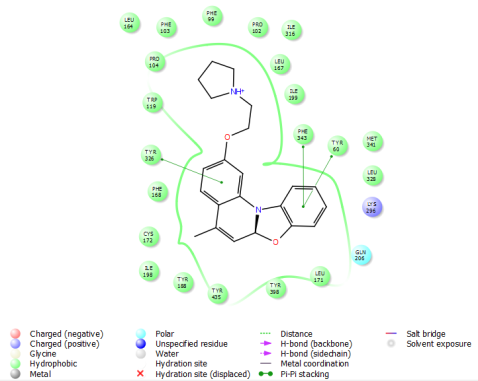

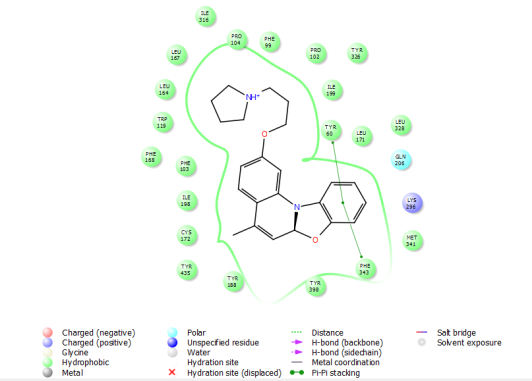

The hydrophobic interactions of ligands 8 and 10 with the amine oxidase protein (PDB ID: 2v5z) were analyzed, revealing their strong engagement with key hydrophobic and nonpolar residues within the binding pocket. Ligand 8 interacted notably with residues such as Leu164, Leu167, Ile316, Ile199, Met341, Leu328, Leu171, Tyr398, Tyr188, Tyr435, Cys172, Ile198, Trp119, and Phe168, while ligand 10 engaged a similar set including Leu164, Leu167, Ile198, Met341, Leu328, Leu171, Tyr188, Tyr435, Cys172, Ile316, Trp119, and Phe168. Both ligands established π-π stacking interactions with aromatic residues Tyr60, Tyr326, and Phe343, enhancing their stabilization within the hydrophobic environment of the active site. Additionally, interactions with the polar residue Gln206 contributed to overall binding stability. The hydrophobic interaction profiles of ligands 8 and 10 are detailed in table 4, with visual representations provided in fig. 2(A-B) and 3(A-B), underscoring the importance of hydrophobic contacts and π-π stacking in driving their strong binding affinity toward amine oxidase.

Table 4: Receptor interactions within 4Å for best ligands

| Protein | PDB | Ligand | Hydrophobic residues | Polar residues | Pi-Pi interactions |

| Amine Oxidase | 2v5z | 8 | Leu164, Leu167, Ile316, Ile199, Met341, Leu328, Leu171, Tyr398, Tyr188, Tyr435, Cys172, Ile198, Trp119, Phe168 | Gln206 | Tyr326, Tyr60, Phe343 |

| 10 | Leu164, Leu167, Ile198, Met341, Leu328, Leu171, Tyr188, Tyr435, Cys172, Ile316, Trp119, Phe168 | Gln206 | Tyr326, Tyr60, Phe343 |

ADME-toxicity and interaction analysis

The pharmacokinetic and toxicity (ADME-T) profiles of ligands 1–16 were evaluated using the QikProp module (Schrödinger, 2012), with results summarized in table 3. Most ligands displayed acceptable pharmacokinetic parameters, indicating favorable oral and systemic properties. All compounds showed 100% predicted human oral absorption, and except for ligand 1, QPlogHERG values indicated low cardiotoxicity risk. Only ligands 10–16 showed potential blood-brain barrier permeability, while ligands 2 and 3 had low skin permeability, and ligands 1–3 had suboptimal hydrogen bond acceptor values. Docking studies with amine oxidase (PDB ID: 2v5z) revealed strong binding interactions for ligands 8 and 10. Ligand 8 showed hydrophobic interactions with PHE94, LEU198, and ILE124, along with π-π stacking with PHE99 and a hydrogen bond with GLU206. Ligand 10 exhibited a similar pattern, with additional electrostatic interaction with LYS66 and enhanced π-π stacking, suggesting stronger binding. Collectively, the ADME-T and docking results identify ligands 10–16, particularly ligand 10, as promising antimicrobial candidates with drug-like properties.

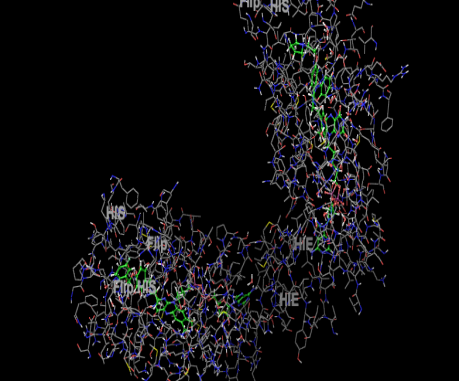

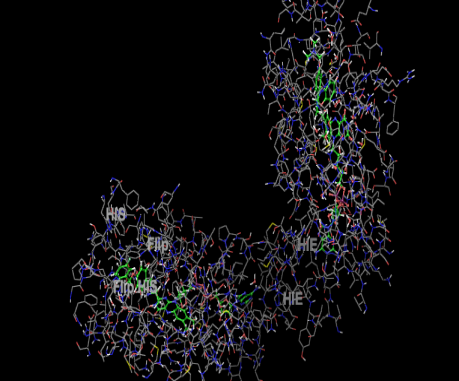

Molecular docking visualization and interaction analysis

The three-dimensional molecular docking visualization offers key insights into the interaction between the target protein and synthesized ligands. The protein is shown in wireframe, revealing its coiled structure with alpha-helices and loops, while atoms follow standard color codes (e.g., blue for nitrogen, red for oxygen). The ligand-binding site is highlighted by green residues, notably aromatic ones like histidine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan, which suggest a predominantly hydrophobic and aromatic pocket. These residues facilitate π-π stacking and hydrophobic interactions, favoring ligands with aromatic or heteroaromatic features. Ligands 8 and 10 showed strong binding within a deep pocket, supported by docking scores and interaction data, with stabilization likely through π-π stacking and hydrogen bonding.

2A) 2(B)

Fig. 2: Hydrophobic interaction of ligand 8 with 2v5z 2D (2A) and 3D (2B)

3(A) 3B)

Fig. 3: Hydrophobic interaction of ligand 10 with 2v5z 2D (3A) and 3D(3B)

The comprehensive docking analysis against human amine oxidase (PDB ID: 2v5z) confirms successful accommodation of the 5-Methyl-6aH-benzo [4,5]oxazolo [3,2-a]quinolin-2-ol derivatives within the active site, reinforcing their biochemical relevance and therapeutic potential. Ligands 8 and 10 demonstrated the strongest binding affinities with docking scores of –10.219 and –10.461 kcal/mol, respectively, owing to their rigid fused aromatic scaffolds that facilitate π–π stacking with key residues such as PHE168 and TRP119, and their flexible ethoxy linkers ending in morpholine or piperidine moieties, which further enhance hydrophobic and polar interactions. Other derivatives like 1, 3, and 14 also exhibited favorable binding through van der Waals and electrostatic interactions driven by specific substituents. Conversely, compounds with bulkier or less interactive terminal groups (5–7, 9, 11–12, 15–17) displayed weaker binding affinities due to suboptimal fit within the enzyme’s active pocket. Collectively, the study underscores the importance of a planar aromatic core, strategic linker flexibility, and interactive terminal functionalities in maximizing ligand binding and highlights the potential of these synthesized compounds, including sulfonyl piperidine carboxamides, as promising amine oxidase inhibitors through reinforced hydrophobic and aromatic interactions.

Future prospective

Building on these promising computational results, future work should focus on the synthesis of ligands 8 and 10 followed by in vitro and in vivo biological evaluation to validate their anticancer efficacy and safety profiles. Structural optimization and analog design may further enhance their activity and selectivity. Additionally, molecular dynamics simulations could be performed to investigate the stability and interaction dynamics of the ligand-protein complexes under physiological conditions. These efforts will be crucial for advancing ligands 8 and 10 toward preclinical development as novel anticancer agents.

CONCLUSION

In this study, molecular docking using Glide was conducted to assess 16 designed ligands against the amine oxidase enzyme (PDB ID: 2v5z), with special attention to hydrogen bond scoring nuances. While hydrogen bonds are typically favorable, their direct impact on binding affinity is often neutral due to water displacement, though entropy gain may enhance overall interaction. Notably, ligands 8 and 10 showed the highest binding affinity, with docking scores of –10.219 and –10.461, respectively, outperforming the reference ligand R-(–)-deprenyl (–6.412). These ligands formed strong van der Waals and electrostatic interactions, exhibited the lowest Glide energies, and demonstrated excellent ADME-Toxicity profiles, including 100% predicted oral absorption and compliance with drug-likeness rules, marking them as promising anticancer candidates.

FUNDING

Nil

ABBREVIATION

AOs: Amine Oxidases, MAO-A: Monoamine Oxidase A, EMT: Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition, CRPC: Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer, ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species, ADMET: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity, WPSA: Weakly Polar Solvent-Accessible Surface Area, QPlogS: Logarithm of Solubility, QPlogHERG: Logarithm of HERG IC₅₀, QPPCaco: Predicted Permeability of Caco-2 Cells, QPlogBB: Logarithm of Brain/Blood Partition Coefficient, QPPMDCK: Predicted Permeability of MDCK Cells, QPlogKp: Logarithm of Skin Permeability, MDCK: Madin-Darby Canine Kidney, IC₅₀:Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration, PDB: Protein Data Bank, XP: Extra Precision, OPLS: Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations, vdW: Van der Waals, Coul: Coulombic Interactions, HERG: Human Ether-à-go-go-Related Gene, GR: Glucocorticoid Receptor.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

The research work was a collaborative effort involving contributions from all authors. Simpi Mehta was primarily responsible for the conceptualization of the study, development of the methodology, conducting investigations, curating the experimental data, and preparing the original draft of the manuscript. Poonam Kaswan provided overall supervision and project administration, ensured validation of the results, and contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. Pooja Ranjan carried out the literature review, performed formal data analysis, and prepared visualizations to support the findings. Sudesh was involved in data collection, execution of experimental work, and management of essential resources required for the study.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

We, the authors, hereby declare that the manuscript titled “Molecular docking and ADMET properties of novel 5-Methyl-6aH-benzo [4, 5]oxazolo [3,2-a]Quinolin-2-ol derivatives for their anti-cancer activity” is an original work and has not been published or submitted for publication elsewhere. We confirm that all authors have significantly contributed to the research and preparation of the manuscript, have read the final version, and agree with its submission. There are no conflicts of interest to disclose, and all necessary ethical guidelines have been followed in the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

Knieper M, Viehhauser A, Dietz KJ. Oxylipins and reactive carbonyls as regulators of the plant redox and reactive oxygen species network under stress. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(4):814. doi: 10.3390/antiox12040814, PMID 37107189.

Gogoi K, Gogoi H, Borgohain M, Saikia R, Chikkaputtaiah C, Hiremath S. The molecular dynamics between reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and phytohormones in plants response to biotic stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2024;43(11):263. doi: 10.1007/s00299-024-03343-3, PMID 39412663.

Lilay GH, Thiebaut N, Du Mee D, Assuncao AG, Schjoerring JK, Husted S. Linking the key physiological functions of essential micronutrients to their deficiency symptoms in plants. New Phytol. 2024;242(3):881-902. doi: 10.1111/nph.19645, PMID 38433319.

Lee KP, Kim C. Photosynthetic ROS and retrograde signaling pathways. New Phytol. 2024;244(4):1183-98. doi: 10.1111/nph.20134, PMID 39286853.

Muro P, Zhang L, Li S, Zhao Z, Jin T, Mao F. The emerging role of oxidative stress in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1390351. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1390351, PMID 39076514.

Sharma R, Kumarasamy M, Parihar VK, Ravichandiran V, Kumar N. Monoamine oxidase: a potential link in papez circuit to generalized anxiety disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2024;23(5):638-55. doi: 10.2174/1871527322666230412105711, PMID 37055898.

Kaswan P, Oswal P, Kumar A, Mohan Srivastava C, Vaya D, Rawat V. SNS donors as mimic to enzymes, chemosensors and imaging agents. Inorg Chem Commun. 2022 Feb;136:109140. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2021.109140.

Srivastava P, Sudevan ST, Thennavan A, Mathew B, Kanthlal SK. Inhibiting monoamine oxidase in CNS and CVS would be a promising approach to mitigating cardiovascular complications in neurodegenerative disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2024;23(3):331-41. doi: 10.2174/1871527322666230303115236, PMID 36872357.

Moreira J, Machado M, Dias Teixeira M, Ferraz R, Delerue Matos C, Grosso C. The neuroprotective effect of traditional Chinese medicinal plants a critical review. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13(8):3208-37. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.06.009, PMID 37655317.

Fatima Shad K. Serotonin neurotransmitter and hormone of brain bowels and blood: Norderstedt Germany: BoD--Books on Demand; 2024 Jun 19. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.1000435.

Patel SS, Acharya A, Ray RS, Agrawal R, Raghuwanshi R, Jain P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of curcumin in prevention and treatment of disease. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60(6):887-939. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1552244, PMID 30632782.

Verma C, Kumar A, Thakur A, editors. Phytochemistry in corrosion science: plant extracts and phytochemicals as corrosion inhibitors. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2024. doi: 10.1201/9781003394631.

Parga JA, Rodriguez Perez AI, Garcia Garrote M, Rodriguez Pallares J, Labandeira Garcia JL. NRF2 activation and downstream effects: focus on parkinsons disease and brain angiotensin. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(11):1649. doi: 10.3390/antiox10111649, PMID 34829520.

Jurcau MC, Andronie Cioara FL, Jurcau A, Marcu F, Tit DM, Pascalau N. The link between oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and neuroinflammation in the pathophysiology of alzheimers disease: therapeutic implications and future perspectives. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11(11):2167. doi: 10.3390/antiox11112167, PMID 36358538.

Santin Y, Resta J, Parini A, Mialet Perez J. Monoamine oxidases in age-associated diseases: new perspectives for old enzymes. Ageing Res Rev. 2021 Mar;66:101256. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101256, PMID 33434685.

Hillman P. Molecular mechanisms of JNKs in anxiety and depression; 2024.

Acero VP, Cribas ES, Browne KD, Rivellini O, Burrell JC, O Donnell JC. Bedside to bench: the outlook for psychedelic research. Front Pharmacol. 2023 Oct 2;14:1240295. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1240295, PMID 37869749.

Labbe M, Hoey C, Ray J, Potiron V, Supiot S, Liu SK. MicroRNAs identified in prostate cancer: correlative studies on response to ionizing radiation. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01186-6, PMID 32293453.

Ghosh S, Hazra J, Pal K, Nelson VK, Pal M. Prostate cancer: therapeutic prospect with herbal medicine. Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov. 2021 Jul 8;2:100034. doi: 10.1016/j.crphar.2021.100034, PMID 34909665.

Ci Q, Yang H, Bian Y, Li Z, Liu J, Wei J. An in situ fluorescent copolymer dots-based kit for the specific detection of monoamine oxidase a in cell/tissue/human prostate cancer. Sens Actuators B. 2023;397:134655. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2023.134655.

Wang YY, Zhou YQ, Xie JX, Zhang X, Wang SC, Li Q. MAOA suppresses the growth of gastric cancer by interacting with NDRG1 and regulating the Warburg effect through the PI3K/AKT/MTOR pathway. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2023;46(5):1429-44. doi: 10.1007/s13402-023-00821-w, PMID 37249744.

Han Y, Chang Y, Wang J, Li N, Yu Y, Yang Z. A study predicting long-term survival capacity in postoperative advanced gastric cancer patients based on MAOA and subcutaneous muscle fat characteristics. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22(1):184. doi: 10.1186/s12957-024-03466-7, PMID 39010072.

Wei J, Wu BJ. Targeting monoamine oxidases in cancer: advances and opportunities. Trends Mol Med. 2025;31(5):479-91. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2024.09.010, PMID 39438199.

Chen CH, Wu BJ. Monoamine oxidase: an emerging therapeutic target in prostate cancer. Front Oncol. 2023 Feb 13;13:1137050. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1137050, PMID 36860320.

Han H, Li H, Ma Y, Zhao Z, An Q, Zhao J. Monoamine oxidase a (MAOA): a promising target for prostate cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2023;563:216188. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216188, PMID 37076041.

Lyu F, Shang SY, Gao XS, Ma MW, Xie M, Ren XY. Uncovering the secrets of prostate cancers radiotherapy resistance: advances in mechanism research. Biomedicines. 2023;11(6):1628. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11061628, PMID 37371723.

Kornicka A, Balewski L, Lahutta M, Kokoszka J. Umbelliferone and its synthetic derivatives as suitable molecules for the development of agents with biological activities: a review of their pharmacological and therapeutic potential. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(12):1732. doi: 10.3390/ph16121732, PMID 38139858.

Zhang T, Li J, Dai J, Yuan F, Yuan G, Chen H. Identification of a novel stemness-related signature with appealing implications in discriminating the prognosis and therapy responses for prostate cancer. Cancer Genet. 2023 Aug;276-277:48-59. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2023.07.005, PMID 37487324.

Kosalge SB, Fursule RA. Investigation of in vitro anthelmintic activity of thespesia lampas (Cav.). Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2009;2(2):69-71.

Zhou S, Wang S, Xiang J, Han Z, Wang W, Zhang S. Diagnostic performance of MRI for residual or recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after locoregional treatment according to contrast agent type: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2024;49(2):471-83. doi: 10.1007/s00261-023-04143-1, PMID 38200213.

Al Ageeli E. Dual roles of microRNA-122 in hepatocellular carcinoma and breast cancer progression and metastasis: a comprehensive review. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46(11):11975-92. doi: 10.3390/cimb46110711, PMID 39590305.

Minakshi KP, Singh K, Devi SR, Yadav N, Yadav M. Recent advances in di-, tri-substituted mono-thiazoles and bis-thiazoles: factors affecting biological activities, future aspects and challenges. Curr Top Med Chem. 2025 Mar 28. doi: 10.2174/0115680266334873250316102556.

Wang X, Xiao K, Liu Z, Wang L, Dong Z, Wang H. Unveiling disulfidptosis-related genes in HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: an integrated study incorporating transcriptome and Mendelian randomization analyses. J Cancer. 2024;15(17):5540-56. doi: 10.7150/jca.93194, PMID 39308675.

Li S, Kang Y, Zeng Y. Targeting tumor and bone microenvironment: novel therapeutic opportunities for castration resistant prostate cancer patients with bone metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2024;1879(1):189033. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2023.189033, PMID 38040267.

Chen L, Xiong W, Qi L, He W. High monoamine oxidase a expression predicts poor prognosis for prostate cancer patients. BMC Urol. 2023;23(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s12894-023-01285-8, PMID 37403079.

Ma Y, Chen H, Li H, Zhao Z, An Q, Shi C. Targeting monoamine oxidase a: a strategy for inhibiting tumor growth with both immune checkpoint inhibitors and immune modulators. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2024;73(3):48. doi: 10.1007/s00262-023-03622-0, PMID 38349393.

Moura C, Vale N. The role of dopamine in repurposing drugs for oncology. Biomedicines. 2023;11(7):1917. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11071917, PMID 37509555.

Zirbesegger K, Reyes L, Paolino A, Dapueto R, Arredondo F, Gambini JP. Molecular imaging of monoamine oxidase a expression in highly aggressive prostate cancer: synthesis and preclinical evaluation of positron emission tomography tracers. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2023;6(11):1734-44. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.3c00175, PMID 37982127.

Mishra S, Gupta A, Jain S, Vaidya A. Anticancer mechanisms of β-carbolines. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2024;103(4):e14521. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.14521, PMID 38653576.

Spirtovic Halilovic S, Salihovic M, Osmanovic A, Veljovic E, Rahic O, Mahmutovic E. In silico study of microbiologically active benzoxazole derivatives. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2023;85(3):767-77. doi: 10.36468/pharmaceutical-sciences.1143.

Abdullahi A, Yeong KY. Targeting disease with benzoxazoles: a comprehensive review of recent developments. Med Chem Res. 2024;33(3):406-38. doi: 10.1007/s00044-024-03190-7.

Kaswan P. Natural resources as cancer-treating material. S Afr J Bot. 2023 Jul;158:369-92. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2023.05.028.

Han D, Lu J, Fan B, Lu W, Xue Y, Wang M. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 inhibitors: a comprehensive review utilizing computer-aided drug design technologies. Molecules. 2024;29(2):550. doi: 10.3390/molecules29020550, PMID 38276629.

Li X, Yujuan Sun, Zhu X. Preparation of chiral carbon quantum dots and its application. J Fluoresc. 2024;34(1):1-13. doi: 10.1007/s10895-023-03262-8, PMID 37199894.

Badgujar ND, Dsouza MD, Nagargoje GR, Kadam PD, Momin KI, Bondge AS. Recent advances in medicinal chemistry with benzothiazole-based compounds: an in-depth review. J Chem Res. 2024;6(2):202-36. doi: 10.48309/jcr.2024.436111.1290.

Sun K, Zhi Y, Ren W, Li S, Zheng J, Gao L. Crosstalk between O-GlcNAcylation and ubiquitination: a novel strategy for overcoming cancer therapeutic resistance. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2024;13(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s40164-024-00569-5, PMID 39487556.

Atole DM, Rajput HH. Ultraviolet spectroscopy and its pharmaceutical applications a brief review. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11(2):59-66. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i2.21361.

Hwang KW, Yun JW, Kim HS. Unveiling the molecular landscape of FOXA1 mutant prostate cancer: insights and prospects for targeted therapeutic strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(21):15823. doi: 10.3390/ijms242115823, PMID 37958805.

Kaswan P. Chalcogenated schiff base ligands utilized for metal ion detection. Inorg Chim Acta. 2023 Oct 1;556:2023.121610. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2023.121610.

Ebenezer O, Jordaan MA, Carena G, Bono T, Shapi M, Tuszynski JA. An overview of the biological evaluation of selected nitrogen containing heterocycle medicinal chemistry compounds. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8117. doi: 10.3390/ijms23158117, PMID 35897691.

Kerru N, Gummidi L, Maddila S, Gangu KK, Jonnalagadda SB. A review on recent advances in nitrogen-containing molecules and their biological applications. Molecules. 2020;25(8):1909. doi: 10.3390/molecules25081909, PMID 32326131.

Alam R, Samad A, Ahammad F, Nur SM, Alsaiari AA, Imon RR. In silico formulation of a next-generation multiepitope vaccine for use as a prophylactic candidate against Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-02750-9, PMID 36726141.

Mohan Kumar R, Anantapur R, Peter A, HC. Computational investigation of phytoalexins as potential antiviral RAP-1 and RAP-2 (replication-associated proteins) inhibitor for the management of cucumber mosaic virus (CMV): a molecular modeling in silico docking and MM-GBSA study. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022;40(22):12165-83. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1968500, PMID 34463218.

Murakawa T, Suzuki M, Fukui K, Masuda T, Sugahara M, Tono K. Serial femtosecond X-ray crystallography of an anaerobically formed catalytic intermediate of copper amine oxidase. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2022;78(12):1428-38. doi: 10.1107/S2059798322010385, PMID 36458614.

Ekstrom F, Gottinger A, Forsgren N, Catto M, Iacovino LG, Pisani L. Dual reversible coumarin inhibitors mutually bound to monoamine oxidase B and acetylcholinesterase crystal structures. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2022;13(3):499-506. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00001, PMID 35300078.

Mohanty M, Mohanty PS. Molecular docking in organic, inorganic and hybrid systems: a tutorial review. Monatsh Chem. 2023;154(7):1-25. doi: 10.1007/s00706-023-03076-1, PMID 37361694.

Guareschi R, Lukac I, Gilbert IH, Zuccotto F. SophosQM: accurate binding affinity prediction in compound optimization. ACS Omega. 2023;8(17):15083-98. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c08132, PMID 37151542.

Padroni G, Patwardhan NN, Schapira M, Hargrove AE. Systematic analysis of the interactions driving small molecule-RNA recognition. RSC Med Chem. 2020;11(7):802-13. doi: 10.1039/d0md00167h, PMID 33479676.

Tu Y. Artemisinin a gift from traditional Chinese medicine to the world (nobel lecture). Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55(35):10210-26. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601967, PMID 27488942.

Liu X, Cao J, Huang G, Zhao Q, Shen J. Biological activities of artemisinin derivatives beyond malaria. Curr Top Med Chem. 2019;19(3):205-22. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190122144217, PMID 30674260.

Zhang B. Artemisinin-derived dimers as potential anticancer agents: current developments action mechanisms and structure activity relationships. Arch Pharm (Weinheim). 2020;353(2):e1900240. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201900240, PMID 31797422.

Zhang X, Liu J, Li Y, Li Y, Zhao Y, He J. Synthesis and evaluation of coumarin artemisinine hybrids as potent anticancer agents. Chem Eur J. 2015;21(49):17415-21.

Rani D, Verma R, Saroha B, Kumar V. Synthesis and anticancer evaluation of novel coumarin azole hybrids. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2021;21(16):1957-76.