Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 9-20Review Article

TARGETED DRUG DELIVERY THROUGH CRISPR‒CAS9: BRIDGING BIOPHARMACEUTICS AND PHARMACOKINETICS

JUBILEE RAMASAMY*, DHARSHINI JAISANKAR, SURUTHI RAMAMOORTHY, DEEPIKA JOTHIBASU, NIRANJANI RAVIKUMAR

Department of Pharmacology, Saveetha College of Pharmacy, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), Saveetha University, Thandalam, Chennai-602105, India

*Corresponding author: Jubilee Ramasamy; *Email: jubileer.scop@saveetha.com

Received: 08 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 01 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Precision medicine transforms healthcare by tailoring treatment methods to individual patient characteristics. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9) gene editing serves as the primary technological force enabling effective targeted alterations of specific genetic information.

This analysis provides a clear overview of how CRISPR-Cas9 technologies enhance drug distribution systems and pharmacologic process management. The combination of CRISPR‒Cas9 technology with gene therapy and targeted drug delivery systems leads to improvements in therapeutic effectiveness.

CRISPR‒Cas9 technology delivers three distinct functional abilities to the medical field including drug target detection along with enhanced targeted delivery mechanisms and gene-edited pharmacokinetic management. The CRISPR‒Cas9 system creates advancements in precision medicine development. The analysis explores new drug delivery techniques alongside CRISPR‒Cas9 role in medication transport systems and biochemical processing mechanisms.

Modern drug delivery systems developed from CRISPR‒Cas9 technology and biopharmaceuticals will build the next generation of precision medicines. Through its ability to regulate drug activation and bioavailability the CRISPR‒Cas9 system plans to revolutionize future medicine supply networks. .

Keywords: Biopharmaceutics, CRISPR‒Cas9 technology, Drug delivery, Gene-editing tools, Gene-targeted therapy, Pharmacokinetics, Precision medicine

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54502 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

The next evolution of modern medicine, precision medicine, has transformed the world of healthcare, pivoting the paradigm toward bespoke treatments tailored to an individual patient’s genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors [1]. Such paradigm-shifting, tournament work is now possible owing to recent advances in genomics, bioinformatics, and molecular biology that enable researchers to challenge mechanisms of disease at an unparalleled scale [2]. Among these breakthrough technologies, CRISPR-Cas9 technology has been one of the most powerful tools for precise gene editing, offering new avenues in disease therapy, targeted drug delivery and pharmacokinetic optimization [3]. As a protective immune mechanism in bacteria and archaea, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats-associated protein 9 (CRISPR‒Cas9) has been repurposed as a highly sophisticated gene-editing platform that enables targeted modification. Since its first use in genome editing in 2013, CRISPR‒Cas9 technology has revolutionized diverse fields, such as genetic disorder therapy in oncology, regenerative medicine and drug development [4-6]. Among the interesting applications of CRISPR‒Cas9 technology is its introduction into targeted drug delivery systems [7]. A field that has long faced challenges such as low bioavailability, systemic toxicity and off-target effects [8]. Conventional drug delivery methods result in low drug distribution, rapid metabolism, adverse side effects, and restricted therapeutic efficacy. CRISPR‒ Cas9 gene-directed drug delivery can overcome these limitations by enabling precise control over drug activation, targeted release and improved absorption and metabolism, ultimately improving pharmacokinetics. In addition to enhancing drug delivery, CRISPR‒Cas9-mediated pharmacokinetic modifications also have considerable ramifications for drug metabolism, absorption and systemic circulation [9-11]. Researchers are highly interested in how CRISPR‒Cas9 technology can be deployed to modulate driver metabolic pathways and transport mechanisms that influence drug bioavailability [12]. For example, gene-editing techniques use CRISPR‒Cas9 systems to cleave genes encoding drug-metabolizing enzymes such as protein kinases and enzyme families [13] and drug transporters (i. e., by CRISPR‒Cas9 gene editing, researchers are working toward creating personalized pharmacotherapy strategies that can increase drug efficacy, decrease adverse reactions and restore drug resistance mechanisms) [14]. The application of CRISPR‒Cas9 in pharmacokinetic and biopharmaceutical applications is fraught with several challenges, such as off-target modifications, immune activation, ethical concerns and regulatory issues [15, 16]. The specificity and safety of CRISPR‒Cas9-mediated gene editing are current topics of interest. Researchers are continuously refining techniques such as base editing, prime editing, and epigenetically designed genome editing [17-19]. Furthermore, the optimization of efficient and safe delivery methods is crucial for the success of CRISPR‒Cas9-based therapies because the ability to target specific cells and tissues and avoid immune clearance is key to the clinical reality [20, 21].

This review provides a critical overview of the dynamic roles of CRISPR‒Cas9 technology in drug delivery and pharmacokinetics and its importance in gene-targeted drug delivery, drug absorption, metabolism, and drug distribution. Also demonstrated how CRISPR‒Cas9 mediated therapies revolutionize the oncological management of rare inherited diseases and regenerative therapy. By combining the disciplines of biopharmaceutics and gene editing, CRISPR‒Cas9 can redesign drug delivery frameworks, leading to next-generation precision medicine strategies that achieve improved drug responses and few side effects.

A comprehensive literature search is conducted using PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus and Web of Science databases to develop this review. A mixture of keywords and MeSH phrases, including “CRISPR‒Cas9,” “Gene Therapy,” “Drug Targeting,” “Pharmacokinetics,” “Clinical Trials,” “Cas9 Diagnostics,” and “Biopharmaceutical Applications,” were used to narrow down the search to publications published between 2021 and 2025. The addition of Boolean operations such as and or enhanced the search functionality. Full-text reviews were conducted on selected publications, and the relevance of articles was assessed by examining their title and abstracts. The minimum criteria for inclusion were peer-reviewed original scientific publications, clinical trial results, and high-impact evaluations of CRISPR‒Cas9 applications in medicine.

Unveiling the potential of CRISPR‒Cas9 in precision medicine

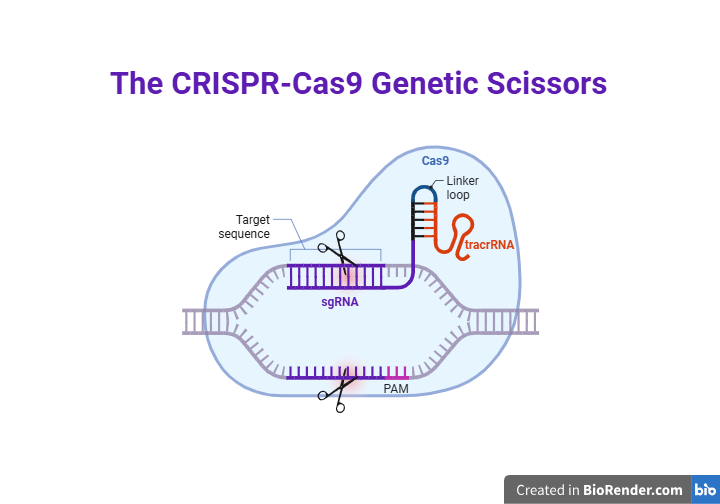

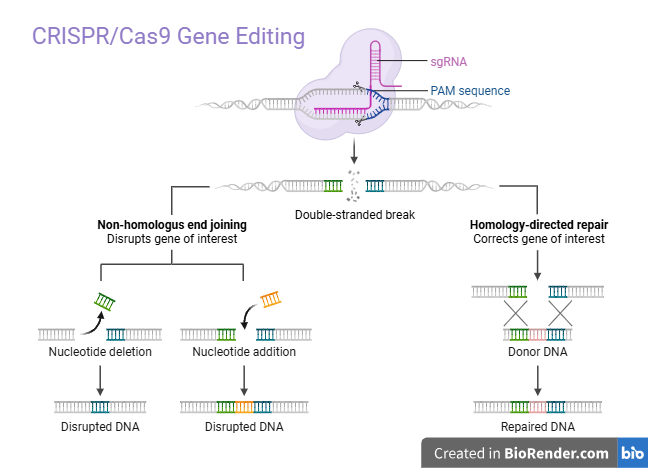

Precision medicine is a rapidly evolving paradigm in healthcare that aims to customize therapy for specific individuals or subpopulations according to lifestyle, environment, and genetic variables. Precision medicine uses cutting-edge technologies to unravel the biological underpinnings of illnesses and provide customized therapies that are more effective and have fewer adverse effects [22]. CRISPR‒Cas9 (fig. 1), which were initially identified as adaptive immune defences in bacteria and archaea have evolved into highly potent genome-editing tools. CRISPR‒Cas9 recognizes a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) and generates one double-strand break (DSB), which is then repaired through Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) or Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) (fig. 2). The biological signal generated by PAM is preserved for future use. The system facilitates highly targeted genetic modifications, leading to significant advancements in biomedical research and gene therapy [23]. Since their first adoption in 2013, the capacity to accurately target, edit, and repair genomic material across various species has been determined. This innovation relies on an endonuclease enzyme, typically CRISPR‒Cas9 Cas9, in conjunction with Single Guide RNA (sgRNA) to recognize and modify certain (DNA) sequences precisely [24]. The key part of the system’s operation is the use of CRISPR‒Cas9 arrays, which are composed of conserved DNA repeats spaced by variable spacer sequences. Space sequences in a specific order develop according to previous interactions, and contact with foreign genetic materials increases the probability of identification and inactivation of foreign DNA. This approach enables researchers to perform targeted genetic modifications and replicate the high specificity and efficiency of their application in various research and clinical applications [25-27].

Fig. 1: CRISPR‒Cas9 genetic scissors: CRISPR‒Cas9 system uses sgRNA-fusion of crRNA and tracrRNA, directs CRISPR‒Cas9 to specific DNA. Cas9 binds to the target site adjacent to the PAM-for CRISPR‒Cas9 recognition and cutting introduce DSB

Fig. 2: Mechanism of genome editing tools: CRISPR‒Cas9 guided by a sgRNA, binds to a target DNA sequence adjacent to a PAM and introduces a DSB. The DSB can be repaired by two main pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) an error-prone DNA repair pathway that can cause gene disruption and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) a precise repair mechanism used to insert or correct gene sequences using a homologous template

CRISPR‒Cas9 and its role in precision medicine

Therapeutic use: CRISPR‒Cas9 provides for the creation of novel cancers, inherited disorders, and infectious diseases. CRISPR‒Cas9 technology provides a cure for previously incurable diseases by correcting disease-causing mutations or eliminating lethal genes. CRISPR‒Cas9 technology provides possible treatments for cancer, inherited disorders, and infectious diseases in novel and unprecedented ways. The deletion of disease-causing mutations or the silencing of lethal genes may lead to once-incurable disorders [28]. For example, CRISPR‒Cas9 can be used in oncology to improve immune cell therapy (Chimeric Antigen Receptor T (CAR-T) cells), treat tumour driver mutations, and bypass drug resistance mechanisms [29]. Gene-editing approaches focusing on underlying genetic defects have been recognized as promising treatments for inherited disorders, including sickle cell anaemia and cystic fibrosis [30].

Biomarker discovery and drug development

The advent of gene-editing technology that functions at the molecular level has truly revolutionized and practically reengineered the entire drug discovery process both deeply and broadly. Such highly effective tools enable researchers to model disease with high efficiency, which makes it easier to identify potential targets for therapies and enables the intelligent design of therapies that act specifically. CRISPR‒Cas9 has also assisted researchers in the discovery of biomarkers for predicting both therapeutic response and a person’s susceptibility to disease [31, 32]. Advances in preventive medicine: CRISPR‒Cas9 is making preventive medicine a reality by enabling the identification of genetic susceptibility to disease beforehand. Precision medicine can apply targeted preventive interventions by identifying vulnerable individuals, lowering the prevalence of illness, and enhancing long-term health outcomes. CRISPR‒Cas9 applications are expected to transform precision medicine as research advances, with innovations leading to advanced therapeutic efficiency, personalization, and accessibility [33, 34].

Enhancing therapeutic efficacy through gene-directed drug delivery

Gene-directed drug delivery is a novel approach that enhances therapeutic efficacy by leveraging endogenous biological processes to produce and regulate therapeutic proteins. This novel technique targets and treats an extensive range of diseases with better results than those obtained from conventional drug delivery. Integrating CRISPR‒Cas9 and other gene-editing techniques with targeted drug delivery systems could lead to genetic modifications while optimizing the delivery of therapeutic agents directly to affected cells [35-37]. Gene therapy is more advanced than drug delivery; it enables the patient’s cells to synthesize therapeutic proteins and therefore does not require repeated external dosing. This outcome not only promises to improve patient complaints with treatment but also represents a potential transformative therapy for rare genetic diseases and commonly acquired disorders such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases [38, 39]. CRISPR‒Cas9 technology leads to gene editing by allowing precise changes to genes that are associated with several diseases. CRISPR‒Cas9 can be formulated with viral vectors in which viruses such as adenoviruses guarantee targeted delivery of gene-editing tools to affected cells. The advantages of adenoviruses are their ability to infect non-dividing cells and their relatively easy large-scale production, which makes them potent vectors for in vivo applications. This strategic combination provides site-specific correction of genetic defects along with simultaneous therapeutic delivery of proteins that have localized and systemic therapeutic functions [40]. Moreover, liposomes, which are nonviral delivery systems, have been shown to be potent mediators that improve the specificity and safety of gene-targeted therapies [41]. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) serve as encapsulants for CRISPR‒Cas9 components, enabling them to deliver targeted delivery to specific tissues, reduce off-target effects and improve gene-editing specificity [42]. This is precisely in line with the development of advanced technologies for gene delivery and the regulation of gene expression, which is essential for diseases where the modulation of genes is essential [43]. The current and future uses of CRISPR‒Cas9 gene editing with gene therapy are highly promising and diverse. The effectiveness of gene therapy is highly improved by increasing the ability to target site-specific genetic defects through CRISPR‒Cas9. The potential for correcting mutations in the genome via CRISPR‒Cas9 could provide a new scope for treating inherited disorders such as sickle cell disease and muscular dystrophy [44].

Exploring CRISPR‒Cas9 applications in drug targeting and absorption

Drugs can be targeted and absorbed with high accuracy via CRISPR‒Cas9 technology. It also allows the systematic identification and confirmation of drug targets, particularly in the field of cancer. To identify the essential genes necessary for cancer survival and growth, scientists can use CRISPR‒Cas9 screening to eliminate cancer cell lines and identify undiscovered drug targets [45, 46]. For example, the discovery of the P53 gene as a tumour suppressor has made it easier to develop targeted therapies for numerous malignancies [47]. Moreover, ATM, CDK8, and EZH2 were identified as therapeutic targets in neuroblastoma via CRISPR‒Cas9 knockout screening, and they improved the effectiveness of drugs such as MEK inhibitors, TOP2, and HDAC inhibitors [48]. Scientists are currently investigating how CRISPR‒Cas9 could be utilized to target and absorb drugs. By using the CRISPR‒Cas9 approach, scientists were able to design cells that would absorb and process drugs more efficiently, which in turn increased the effectiveness of the therapeutic response. Moreover, CRISPR‒Cas9 technology has been used to develop targeted drug delivery systems that minimize the adverse effects of achieving the desired drug effect by modulating intestinal epithelial cells and increasing the uptake of drugs associated with oral metabolic disorders [49]. For example, LNP delivery systems have been designed to release CRISPR‒Cas9 components directly into target cells, thus improving efficient genome editing of the liver [50]. Another example involves the release of chemotherapy drugs directly into breast cells via CRISPR‒Cas9 engineering, which results in minimal harm to healthy tissues. The release of CRISPR‒Cas9 through LNPs edited the TTR gene, resulting in a reduction in disease-causing protein, is one of the notable practical uses of this approach for editing transthyretin amyloidosis via CRISPR‒Cas9 and CasT [51].

Despite its immense potential, CRISPR‒Cas9 faces several challenges, including side effects caused by targeted reactions and immune challenges. The safety and effectiveness of these systems are constantly being improved by scientists. Changing gRNA and base editors are the discoveries that aim to address these shortcomings to improve gene editing accuracy. CRISPR‒Cas9 technology is also used to fight drug resistance in cancer treatment by targeting and eliminating genes that cause cancer cells to respond to chemotherapy. Applications that involve therapeutic use in sickle cell anaemia and beta-Thalassemia treatments also suggest the transformative potential of CRISPR‒Cas9 technology in precision medicine. The clinical approval of Casgevy (exa-cel) to treat these conditions highlights its ability to provide potential treatments for genetic disorders [52, 53].

Transforming pharmacokinetics with advanced gene editing tools

Gene editing tools, particularly CRISPR‒Cas9, have transformed pharmacokinetics into genetic modifications that directly affect drug breakdown and distribution [54]. For example, CRISPR‒Cas9 was used to develop rat models with certain genes, such as Cyp, Abcb1, and Oatp1b2. These models are used to understand drug breakdown, chemical toxicity, and carcinogenicity, providing a brief understanding of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics (DMPK) [55]. CRISPR-Cas9-based therapies are becoming pharmacokinetic in clinical settings. Unlike conventional drugs that need repeated doses, CRISPR‒Cas9 therapy can result in permanent genetic changes with a single dose; this approach focuses on rethinking conventional pharmacokinetic models [56]. For example, CRISPR‒Cas9 is used in vivo to treat transthyretin amyloidosis, which lowers the transthyretin protein in the blood and offers long-term treatment from a single treatment [57]. Additionally, the effectiveness and specificity of CRISPR‒Cas9 based therapies are being enhanced by the development of delivery vectors. Novel delivery technologies such as viral vectors and LNPs have enabled the delivery of CRISPR‒Cas9 components to certain tissues, enhancing the therapeutic response and lowering off-target consequences [58]. These innovations directly affect the pharmacokinetics and bio-distribution of editing tools, making them essential for the potent use of CRISPR‒Cas9 in clinical contexts. Furthermore, by facilitating precise genome modifications, CRISPR‒Cas9 has been applied to treat various ailments, such as cancer and other metabolic disorders. This flexibility highlights CRISPR‒Cas9 technology’s wide range of possibilities for developing innovative therapeutic approaches that can be modified to meet the demands of specific patients, enhancing therapy safety and efficacy [59, 60].

Synergy between CRISPR‒Cas9 and biopharmaceutics for precision therapy

The simultaneous application of biopharmaceutics and CRISPR‒Cas9 is transforming precision medicine. Precise genome modifications have been rendered possible by CRISPR‒Cas9, particularly CRISPR‒Cas9, which is used to treat numerous genetic disorders. With the goal of optimizing CRISPR-Cas9-based therapies, biopharmaceutics that focus on the development and administration of biologically produced medications are essential [61]. CRISPR‒Cas9 has been applied in cancer therapy to modify genes involved in tumour development, providing information on tumour biology and potent target therapy. Additionally, various cancer models have been modified via CRISPR-Cas9-based technology, which has enhanced the understanding of carcinogenesis and simplified the development of targeted therapy [62]. Despite these developments, drawbacks such as distribution, off-target effects, and ethical issues exist. Ongoing research remains in progress to address ethical issues concerning gene editing, provide a safer delivery system, and improve the specificity and effectiveness of CRISPR‒Cas9 based systems. Precision therapy could yield targeted, useful, and customized treatments for several diseases in the future owing to the integration of CRISPR‒Cas9 with biopharmaceutics [63, 64].

Optimizing drug distribution and efficacy via CRISPR‒Cas9 systems

The application of CRISPR‒Cas9 systems in the optimization of drug distribution and effectiveness represents a major breakthrough in the medical field, providing precise gene editing capabilities that enhance therapeutic responses. By encouraging targeted modifications within the gene, CRISPR-Cas9, which consists of Cas9 nuclease and sgRNA, makes it simple to generate customized medications. CRISPR‒Cas9 based systems significantly accelerate the process of identifying and validating valuable targets for drug development, revealing reliable biomarkers, and encouraging the development of innovative therapies [65-67]. Researchers should ensure the use of therapeutic compounds, discover novel drug targets, and generate attainable disease models by permitting precise gene editing. A viable gene editing process depends on the effective release of CRISPR‒Cas9 compounds into targeted cells [68].

There have been several proposals to improve the delivery of medication. LNPs promote the cellular uptake of CRISPR‒Cas9 components while decreasing immunogenicity. Recently, LNPs have been optimized for tissue-specific gene-editing applications due to advances in selective organ targeting (SORT) [69]. Another method involves electroporation, which briefly permeates cell membranes and delivers CRISPR‒Cas9 Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) [70]. Additionally, because of their broad infectivity and low immunogenicity, CRISPR‒Cas9 components are often delivered to specific cell types via a viral vector (i. e., optimal therapeutic impact is achieved by using these delivery methods to ensure that CRISPR‒Cas9 components reach their intended targets within the body) [71]. In addition to delivery, CRISPR‒Cas9 systems are essential for improving drug efficacy. Gene therapy is a crucial tool that facilitates the direct correction of genetic mutations, potentially providing new avenues for treating inherited diseases. Blood disorders such as sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia can be treated with gene-editing therapies that modify patient cells to produce healthy red blood cells. By selectively altering genes, CRISPR‒Cas9 facilitates target validation and identification of crucial drug targets involved in disease mechanisms. Moreover, the presence of particular mutations allows scientists to investigate drug resistance mechanisms, which could lead to more efficient therapies [72, 73].

A new era of drug delivery: integrating CRISPR‒Cas9 in biopharmaceutical development

The development of CRISPR-Cas9-based technologies has led to an entirely new age of biopharmaceutical research, especially drug delivery. This gene-editing technology promises improved accuracy and effective treatment by editing genetic components with previously unimaginable efficiencies. CRISPR-Cas9-based technologies facilitate easier identification and confirmation of target drugs. By identifying disease pathways, scientists are able to identify new therapeutic molecules through the use of base gene modifications, gene knockdowns, and knock-ins [74]. The duration required to introduce innovative medicine to the market is reduced by the possibility of editing genes effectively, which is aiding biopharmaceutical research and development. CRISPR‒Cas9 based technology has various effects on medicine delivery, one of which involves the possibility of using curative elements to target expected genetic locations [75]. Although gene editing is a highly compressed process, CRISPR‒Cas9 technologies may amplify therapeutic effects while reducing off-target effects. This technology is most effective in the treatment of infectious infections, tumours, and gene-related problems [76]. Reliable delivery systems are the most important factor in the successful application of CRISPR‒Cas9 drugs. The efficacy and safety of CRISPR‒Cas9 based drugs have been greatly enhanced by the development of lipid-based carrier viral vectors and nanoparticle-mediated delivery. To increase the bioavailability of gene-editing components and their stability and specificity, new delivery systems are necessary [77]. Some CRISPR‒Cas9 based drugs are in clinical trials, and their potential in therapeutic applications is indicated. For example, Casgevy (exa-cel) is a CRISPR-based therapy that edits individual hematopoietic stem cells that are approved specifically for the treatment of sickle cell disease, and beta-thalassemia. CRISPR‒Cas9 based HIV and cancer immunotherapy are promising areas in which rapid response therapy has emerged [78]. Although it has tremendous potential, CRISPR‒Cas9 technology has several limitations, such as immune responses, potential off-target effects and ethical issues. More research is needed to enhance the specificity and safety of CRISPR‒Cas9 based drugs. As delivery technologies and gene-editing machinery advance, the use of CRISPR‒Cas9 technology for therapeutic applications will expand. This will allow the development of highly effective treatments [79].

Gene editing in pharmacokinetics: Redefining drug targeting strategies

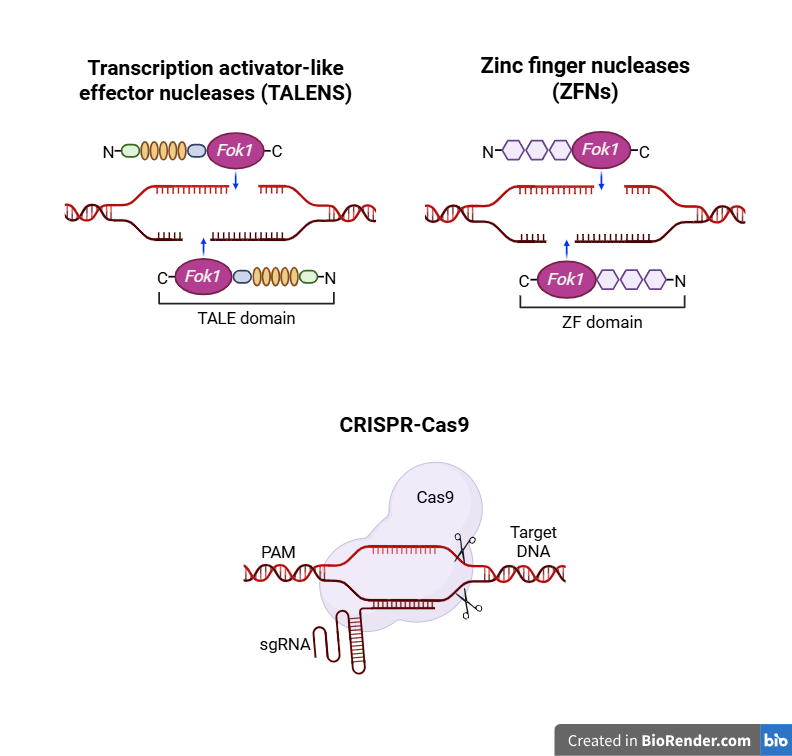

The pharma industry is using gene editing, an emerging technology that greatly improves the processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. This is particularly notable. This will transform drug-targeting strategies by creating new avenues to increase therapeutic effectiveness, individualize drugs, and reduce adverse effects. Advanced tools that encompass transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) (fig. 3), zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) (fig. 3), and CRISPR‒Cas9 (fig. 3) improve specific gene alterations that impact drug delivery and metabolism. Although all these three tools reply on engineered nucleases, they vary significance in ease of design, targeting range, delivery potential, and clinical applications, which is explained in (table 1). CRISPR‒Cas9 is particularly appealing due to its ease and flexibility for use in various laboratories for research and medical applications. However, TALENs and ZFNs are still of considerable use when more specificity or PAM-independent cleavage is required. Altogether, these platforms comprise a rather flexible set of tools for therapeutic genome editing. This will transform drug-targeting strategies by creating new avenues to increase therapeutic effectiveness, individualize drugs, and reduce adverse effects [80].

Fig. 3: Genome-editing tools: transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN), zinc finger nucleases (ZFN) and CRISPR‒Cas9

Table 1: Comparative analysis of gene-editing tools (CRISPR‒Cas9 TALENs, and ZFNs)

| Feature | CRISPR–Cas9 | TALENs | ZFNs |

| Ease of design | Simple (requires gRNA) | Moderate (custom protein per target) | Complex (modular protein domains) |

| Targeting flexibility | High (PAM-dependent) | Very high (no strict motif needed) | Moderate |

| Editing efficiency | High | Moderate to high | Moderate |

| Specificity | Improved with high-fidelity Cas9 | High | High |

| Off-target effects | Possible; mitigated with variants | Low | Low |

| Delivery methods | Viral/non-viral (LNPs, AAVs, etc.) | Mainly viral vectors | Mainly viral vectors |

| Clinical trials (as of 2025) | Dozens (e. g., Casgevy, EDIT-101) | Few (e. g., sickle cell trials) | Very limited |

| Cost and scalability | Low-cost, scalable | Labor-intensive | Labor-intensive |

Gene editing has a significant effect on drug metabolism by optimizing therapeutic efficacy and customizing treatment to avoid adverse effects. For example, it enables one to modify drug metabolism and transport genes to improve pharmacokinetics for individualized therapy. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes play large roles in the activity level and half-life of products. Gene editing of the genes encoding P450 enzymes allows the design of slow or fast drug processing [81]. Similarly, gene editing via the CRISPR‒Cas9 platform may knock out cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6), a gene editing drug transporter, to increase drug amounts in target tissues or accelerate clearance. Knockout of the ATP-binding cassette sub-family b member (ABCB1) Multidrug Resistance Protein 1 (MDR1) gene encoding P-glycoprotein (P-gp) enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy in drug-resistant cancers [82]. Investigations of gene-editing approaches have included lipid metabolism for drug distribution enhancement. They demonstrated that CRISPR‒Cas9 based Solute Carrier Organic Anion Transporter Family Member 1B1 (SLCO1B1) gene editing enhanced statin uptake, reducing the variability in cholesterol-lowering effects [83]. These treatments increase drug bioavailability and therapeutic efficiency. Prodrugs can be thought of as drugs that are converted by enzymes into their active forms. This process can be either enhanced or diminished through gene expression via gene editing. For example, by modifying carboxylesterase 1 (CES1), irinotecan bioactivation was improved, which was then expected to provide greater therapeutic benefits [84]. Similar studies have been carried out on the DPYD gene to determine ways to reduce serious toxicity in patients receiving fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy. The most recent report by described the use of CRISPR‒Cas9 technology to restore mutations in the DPYD gene as a means of lowering the side effects of cancer therapy and improving treatment outcomes. Owing to their potential, such mechanisms increase pharmacological efficacy while simultaneously targeting off effects. The challenge posed by adverse effects on drug metabolism presents a further challenge. Hence, off-target effects can provoke unforeseen changes in drug metabolism, which emphasizes a very stringent validation process. The regulatory framework should incorporate safety and efficacy within the mandate of ethics to govern its systematic application[85,86]. Recently described the ethical implications of germline editing of drug metabolism genes, thereby substantiating the extreme need for the stringent regulation of inflammation before its clinical application. With the advent of innovative strategies for gene editing, pharmacokinetics has begun to usher in personalized therapeutics that focus precisely on individual genetic attributes. In directing pharmacological selection via predictive modelling applications, the incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) might offer services. Thus, gene therapy strategies for pharmacokinetic disorders could offer potential therapeutic avenues, indicating hope in precision medicine [87].

Advancing drug delivery mechanisms with CRISPR‒Cas9 technology

Delivery of CRISPR–Cas9 modules is a major determinant of genome editing application efficiency and safety. Several delivery vehicles are widely used, including viral vectors like adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) and lentiviruses, and non-viral systems such as LNPs. Each system has unique properties regarding delivery efficacy, immunogenicity, and cargo capacity [88]. AAVs are preferred for gene therapy as they are weakly immunogenic and support long-term, stable gene expression. Even with these advantages, AAVs possess a limited payload capacity of around 4.7 kilobases (kb), which restricts the size of the genes that can be delivered. Further, their native tropism is predominantly liver-specific, and it is difficult to redirect this to other tissues for gene delivery, hence restricting their application to certain therapeutic use. Lentiviral vectors have an advantage in gene therapy as they can be packed with higher genetic constructs and can integrate into the host genome stably, with therapeutic gene expression being maintained for longer periods. The integration, though, is dangerous through pathways like insertional mutagenesis, leading to disruption of essential genes and risk of oncogenesis, making safety a concern. Choosing the most suitable vector for gene therapy involves considering the benefits and drawbacks to achieve therapeutic advantages while minimizing harm to the patient [89]. Non-viral delivery technologies have come into focus over the last decade with the possibility of advantages over conventional viral vectors, especially in gene therapy and mRNA delivery. Among them, LNPs are one of the front-line technologies. One of the latest developments in the area is the creation of selective organ targeting LNPs (SORT-LNPs), which are specially designed to allow the targeted and transient delivery of therapeutic compounds to specific organs or tissues [90]. SORT-LNPs are designed to be tailored on different parameters, such as lipid composition, size, and surface characteristics, which make them efficient for targeting a specific cell type. Targeting not only increases the efficacy of the delivered payload but also minimizes off-target effects to a great extent, avoiding unwanted side effects in off-target organs. Optimized nanoparticles also minimize immune responses, thus improving the overall safety profile. This specificity in targeting lies at the core of the development of personalized medicine, with treatments being made specifically to suit each patient. CRISPR‒Cas9 delivery is problematic in light of the potential for drug delivery in the future due to innovation. Epidemiologic studies indicate that the use of gene-editing technologies that involve both base and prime editing results in more precise genetic modifications with fewer harmful side effects [91].

Innovations in drug transport and metabolism through CRISPR‒Cas9 systems

Through precise gene modifications, CRISPR‒Cas9 systems have revolutionized drug transport and metabolism research, allowing pharmacokinetic control by altering the ADME functions. Through its ability to target specific drug transporters and metabolic enzymes, CRISPR‒Cas9 technology develops personalized pharmacotherapies and enhances drug effectiveness with reduced adverse effects [92]. Table 2 summarizes the key applications of CRISPR‒Cas9 in drug delivery, while table 3 highlights the gene targets and their implications in pharmacokinetics.

CRISPR‒Cas9 in drug transport

Medical science identifies drug transporters from solute carrier (SLC) and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) families as essential determinants of drug tissue distribution and bioavailability. Through CRISPR‒Cas9 techniques, scientists generate therapeutic benefits by controlling the expression and functions of these transporters. A noteworthy example shows how the SLCO1B1 genetic elements control the development of hepatic organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1 B1 (OATP1B1). Through its regulatory function, Statin transporters control the cellular penetration of medication types such as simvastatin and atorvastatin. A CRISPR‒Cas9 system enhances statin uptake and minimizes myopathy risk when it targets the PDZ-domain scaffolding protein to increase SLCO1B1 c.521T>C transporter entry points for cell membranes.

The P-gp cancer resistance transporter activity is disrupted through CRISPR‒Cas9 knockout of ABCB1 in oncology-driven tissues, making cells unable to expel chemotherapeutic drugs, including doxorubicin and paclitaxel. Drug retention increases in cancer cells, leading to better treatment response. The sustained therapeutic effect becomes limited by alternate transporter expression, such as ABCG2 (BCRP), so multi-layered gene editing approaches targeting numerous resistance pathways become essential for achieving durable therapeutic responses [93].

CRISPR‒Cas9 in drug metabolism

Drug metabolism primarily depends on the CYP enzyme superfamily because these enzymes control drug clearance and systemic exposure. CRISPR‒Cas9 technology enables exact adjustments of these enzymes, providing a better therapeutic prognosis. One key enzyme, CYP2D6, leads opioid and antidepressant, and beta-blocker metabolism, yet demonstrates extensive natural variability because of inherited polymorphisms in genes. CRISPR‒Cas9 disruption of ultrarapid drug metabolizer genes prevents dangerous accumulation of metabolites, and CRISPR activation in poor metabolizers properly controls drug absorption rates. The modifications in this method target heme-binding domains and promoter elements as treatments for enzymatic problems. Through CRISPR‒Cas9 manipulation of pregnane X receptor response elements, regulatory regions, transplant medicine scientists now possess control over tacrolimus metabolism by Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4). The expression changes in enzyme patterns induced by CRISPR‒Cas9 result in intractable metabolic outcomes from cytochrome P450 3A5 (CYP3A5) and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and sulfotransferases, raising concerns about optimal immunosuppressant concentrations [94]. Research teams implementing CRISPR methods have discovered ways to reduce Cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2) metabolic function, which helps control negative reactions to stimulants in sensitive patients who do not tolerate these drugs well. Correcting CYP1A2 requires special treatment because this enzyme works on key medications like clozapine, resulting in drug safety challenges. Urgent implementation of systems biology models and metabolic pathway simulations is necessary because of the complex requirements for designing CRISPR‒Cas9 based interventions. Future research should concentrate on implementing base editing or prime editing techniques that prevent DNA double-strand breaks in gene editing methods. Safe gene expression modification tools derived from epigenomic editing appear to present DNA-sequence-independent solutions. Real-time drug metabolism control based on patient physiological states becomes possible through CRISPR‒Cas9 technology we target area may alter additional genes that regulate pharmacokinetic processes, thus affecting drug safety outcomes. The functional similarity among members of enzyme families and transporters undermines targeted genomic modifications, making it necessary to use multiple genetic targets instead of single-gene edits. The deployment of CRISPR‒Cas9 components requires improvement for efficiency and tissue-targeted delivery, specifically in liver and intestinal tissue. The ongoing development of ethical frameworks matches the evolution of regulatory standards regarding gene modifications to germline cells and somatic cell edits for non-fatal human conditions [95].

Strategies to mitigate off-target effects

Off-target activity is a major problem in CRISPR‒Cas9 based genome editing since off-target genomic modifications may lead to genotoxicity or unintended phenotypes. To address this problem, some strategies have been established to enhance targeting specificity. High-fidelity Cas9 variants, including eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1, and HypaCas9, have engineered mutations that minimize non-specific DNA binding without compromising efficient on-target cleavage. Base editing and prime editing allow for accurate nucleotide conversions without inducing double-strand breaks, minimizing the risks of off-target effects. Base editors use catalytically dead CRISPR‒Cas9 proteins fused with deaminase enzymes to edit single DNA bases. Prime editors utilize a reverse transcriptase fused with a Cas9 nickase, directed by a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA), which enables flexible and accurate sequence editing. These advancements represent significant progress in improving safety profiles of genome editing. Additionally, complementary off-target discovery platforms like guide with synthetic biological approaches that employ biosensors and regulatory circuits. What results from these latest advancements will lead to a new era based on precision pharmacology through genome engineering [96].

Limitations and future directions

Numerous difficulties persist which hinder the implementation of CRISPR‒Cas9 technology for drug transport and metabolism applications. Genome modifications made outside th-seq, Digenome-seq, and CIRCLE-seq allow for the verification and optimization of CRISPR‒Cas9 constructs intended for therapeutic applications.

Table 2: Applications of CRISPR‒Cas9 in drug delivery

| Application | Example | Mechanism | Clinical status | Reference |

| Cancer therapy | CRISPR-engineered CAR-T cells for leukemia and lymphoma | CRISPR edits immune cells to enhance tumour targeting | Phase I/II | [97] |

| Genetic disorder treatment | CRISPR-based therapy for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia | Corrects genetic mutations to restore normal function | Phase II | [98] |

| Metabolic disorders | CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 gene editing for personalized pharmacokinetics | Modifies genes regulating drug metabolism to optimize dosing | Preclinical | [99] |

| Overcoming drug resistance | ABCB1 (MDR1) gene knockout to enhance chemotherapy efficacy | Knocks out genes responsible for drug resistance in cancer cells | Preclinical | [100] |

| Enhanced drug absorption | SLCO1B1 gene editing to enhance statin uptake |

Modifies transporter proteins to improve bioavailability |

Preclinical | [101] |

| Targeted drug delivery | Lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-mediated CRISPR therapy for liver diseases | CRISPR-loaded nanoparticles direct drugs to specific tissues | Preclinical | [102] |

| Infectious disease treatment | CRISPR-based antiviral therapies for HIV and hepatitis B | CRISPR targets and destroys viral or bacterial genomes | Preclinical | [103] |

| Prodrug activation | CES1 gene editing for irinotecan activation in colorectal cancer | Enhances enzyme activity to optimize drug conversion | Preclinical | [104] |

Table 3: CRISPR‒Cas9 in pharmacokinetics-gene targets and its therapeutic applications

| Gene targeted | Function | CRISPR-based modification | Therapeutic application | Clinical status | Reference |

| CYP2D6 | Metabolizes antidepressants and Opioids | Gene editing to control metabolism rate | Personalized dosing for psychiatric and pain medications | Preclinical | [105] |

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | Efflux transporter for chemotherapy drugs | Knockout to prevent drug resistance | Enhances chemotherapy efficacy in resistant tumors | Preclinical | [106] |

| SLCO1B1 | Regulates statin uptake | Enhances transporter expression | Reduces variability in cholesterol-lowering drug response | Preclinical | [107] |

| DPYD | Metabolizes Fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy drugs | Gene correction to reduce toxicity | Prevents adverse effects in cancer patients | Preclinical | [108] |

| CES1 | Activates prodrugs like irinotecan | Modulation for enhanced drug activation | Improves chemotherapy response in colorectal cancer | Preclinical | [109] |

| CYP3A4 | Metabolizes immunosuppressants and anticancer drugs | Gene editing to regulate metabolism | Optimizes dosing in organ transplants and cancer therapy | Preclinical | [110] |

| NAT2 | Acetylation of drugs affecting metabolism | Modification to balance acetylation rates | Reduces drug toxicity in treatments like tuberculosis | Preclinical | [111] |

| GSTP1 | Detoxifies chemotherapy drugs like cisplatin | Knockout to reduce drug resistance | Enhances efficacy of chemotherapy in lung and ovarian cancers | Preclinical | [112] |

| UGT1A1 | Glucuronidation ofirinotecan and bilirubin metabolism | Modulation to regulate enzyme levels | Minimizes side effects of irinotecan in cancer treatment | Preclinical | [113] |

| SLC22A1 (OCT1) | Organic cation transporter for metformin and anticancer drugs | Upregulation to enhance drug uptake | Improves efficacy of metformin in diabetes management | Preclinical | [114] |

| CYP2C19 | Metabolizes proton pump inhibitors, antidepressants, and clopidogrel | Correction to optimize drug metabolism | Prevents treatment failures in patients with genetic variants | Preclinical | [115] |

| HMGCR | Key enzyme in cholesterol synthesis (statin target) | Gene silencing for cholesterol reduction | Alternative therapy for hypercholesterolemia | Preclinical | [116] |

| OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 | Liver uptake transporters affecting drug clearance | Modifications to improve hepatic drug uptake | Optimizes dosing of statins and anticancer agents | Preclinical | [117] |

| PEPT1 (SLC15A1) | Peptide transporter in the intestine | Enhanced expression to improve oral drug absorption | Increases bioavailability of peptide-based medications | Preclinical | [118] |

| MDR1 (ABCB1) | Multidrug resistance protein affecting chemotherapy drugs | Knockout to prevent drug efflux | Overcomes chemotherapy resistance in cancers like breast and colorectal | Preclinical | [119] |

| BCRP (ABCG2) | Efflux transporter affecting cancer drug retention | Inhibition to increase intracellular drug concentration | Enhances effectiveness of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy | Preclinical | [120] |

| SULT1A1 | Sulfotransferase enzyme involved in drug metabolism | Modulation to enhance drug activation | Optimizes metabolism of anti-inflammatory and anticancer drugs | Preclinical | [121] |

Clinical translation and ongoing trials

To enhance the practical applicability of the CRISPR‒Cas9-based system in treatment, it is essential to accentuate the clinical trials currently afoot, which truly depict the advancement of therapy-oriented concerning the disease. For example, the Casgevy (exa-cel), developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR‒Cas9 Therapeutics, was approved in the UK and the US for sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia, the first CRISPR–Cas-based drug approval. The trial NCT04853576 is on the use of CRISPR‒Cas9 editing of haemopoietic stem cells for fetal haemoglobin reactivation in SCD patients [122]. Also, under the registration number NCT03872479, EDIT-101 addresses Leber Congenital Amaurosis 10 (LCA10) through the subretinal injection, making it the first CRISPR‒Cas9 trial on human eyes in the field of ophthalmology [123]. In cancer therapy, NCT04278590 is an allogeneic CRISPR‒Cas9 edited CAR T cell therapy called CTX110 for B cell malignancy [124]. NTLA-2002, the in vivo CRISPR‒Cas9 gene therapy for HAE, demonstrated a 95% reduction of HAE attacks in the first stage of the clinical trial [125]. Furthermore, Excision Bio Therapeutics’ EBT-101 uses a CRISPR‒Cas9 based excision strategy to try to eliminate HIV [126]. Regional safety concerns play a crucial role in carrying these treatments from the lab to the patient’s bedside. Gene-editing medications were regulated by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and classified as advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs). These treatments must strictly adhere to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs). Treatments should also include long-term follow-up for patients, which may extend up to 15 y in some cases. Lastly, accurate preclinical validation, an Investigational New Drug (IND) application, and compliance with International regulations are required before any trials can begin. In EU member states, national bioethics committees can influence the approval for trials, especially for first-in-human studies. The EMA excludes germline editing and requires environmental risk assessments for gene-editing products that meet the criteria for being classified as genetically modified organisms. To maintain compliance, uphold ethical integrity, and foster consumer trust, researchers and developers must strategically navigate these region-specific frameworks.

The growing number of CRISPR–Cas9 based clinical studies demonstrates significant progress in integrating gene-editing therapies into standard medical practices despite existing regulatory challenges. The beneficial and secure use of CRISPR–Cas9 technology in precision medicine requires the alignment of global regulations and the establishment of clear ethical guidelines as the field advances [127].

CRISPR‒Cas9 based diagnostics: emerging tools for precision medicine

The CRISPR‒Cas9 technology has over the years been applied to enhance diagnosis related techniques. The following are some of the recent tools in the CRISPR–Cas9 system; Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter (SHERLOCK) and DNA Endonuclease Targeted CRISPR‒Cas9 Trans Reporter (DETECTR) are among the widely used platforms that base the activity of CRISPR associated protein 13 (Cas13) and CRISPR‒Cas9 associated protein 12 (Cas12) collateral respectively. They can detect viral and bacterial antigens for clinical and field diagnostic purposes, as well as tumour-specific genes. Specific high-sensitivity enzymatic reporter unlocking (SHERLOCK) is used to identify RNA present in pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 and can also be used to detect some STDs like chlamydia and gonorrhoea. Also, there are over-the-counter CRISPR‒Cas9 diagnostic kits in clinical development to achieve the goal of widespread use and monitoring in nonclinical applications. Cas12a-based DNA Endonuclease Targeted CRISPR‒Cas9 trans reporter (DETECTR) has successfully detected other DNA viruses, including HPV, and has the possibility of application in cervical cancer screenings. They provide results within one hour, do not need many instruments, and can be used at the point of care. Apart from infectious diseases, CRISPR‒Cas9 is further used in diagnostics, detecting circulating tumor nucleic acids for early cancer diagnosis through liquid biopsy. Modern bioengineering has advanced to include microfluidics, wearable sensors, and paper-based assays, making these technologies suitable for low-resource environments. They also have the capability for personalized drug tracking to evaluate pharmacogenomics signatures and therapeutic outcomes at an individual level. Altogether, SHERLOCK, DNA Endonuclease Targeted CRISPR‒Cas9 Trans Reporter (DETECTR), and similar systems based on the CRISPR‒Cas9 technology are already an emerging field in precision medicine. They are fast, accurate, and deployable in the field, making them valuable supplements to CRISPR‒Cas9 therapeutics for customizing treatment plans and improving patient lives [128-130].

CONCLUSION

CRISPR‒Cas9 technology has revolutionized drug delivery and pharmacokinetics, enabling gene-editing activity to target specific sites with a greater therapeutic effect. With the capacity to activate drugs at target sites, and maximize metabolism, and bioavailability, CRISPR‒Cas9-based methods tend to displace conventional drug delivery systems. Through specific targeting genes in metabolism (CYP2D6, CYP3A4), transport (ABCB1, SLCO1B1), and activation (CES1), CRISPR‒Cas9 has rendered it possible to precisely handle pharmacokinetic applications. Application in gene modification, CAR-T cell therapy, and LNP administration has improved cancer, β-thalassemia, and sickle cell disease treatment approaches. Enhanced tissue-specific targeting, less toxicity, and increased absorption have resulted from integration with biopharmaceutical techniques. Despite limitations which include adverse reactions and off-target modifications, constant improvements in delivery techniques and editing precision are advancing CRISPR‒Cas9-based pharmacotherapy further into clinical practice and enhancing this technique as an integral component of future precision medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors express their thanks and gratitude to Saveetha Institute Medical and Technical Science, Thandalam, for providing support for publishing this research article. The graphical abstract and images were created by using BioRender.com (https://biorender.com/).

FUNDING

There is no funding source for this article.

ABBREVATIONS

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR), CRISPR‒associated protein 9 (Cas9), Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), Double-Strand Break (DSB), Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), Guide RNA (gRNA), Single Guide RNA (sgRNA), CRISPR RNA (crRNA), Trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T), Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV), Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP), Selective Organ Targeting Lipid Nanoparticle (SORT-LNP), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC), ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily B Member 1 (ABCB1), Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (ABCG2), Solute Carrier Organic Anion Transporter Family Member 1B1 (SLCO1B1), Organic Cation Transporter 1 (OCT1), Peptide Transporter 1 (PEPT1), Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase (DPYD), UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1), Sulfotransferase Family 1A Member 1 (SULT1A1), Carboxylesterase 1 (CES1),Cytochrome P450 (CYP), N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2), Glutathione S-transferase Pi 1 (GSTP1), 3Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase (HMGCR), Artificial Intelligence (AI), Prime Editing Guide RNA (pegRNA), Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter unLOCKing (SHERLOCK), DNA Endonuclease Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter (DETECTR), Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), European Medicines Agency (EMA), Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Jubilee R: conceived the idea, supervision, and revision of article. Dharshini J H: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. All authors performed the literature search and made the initial draft. Ethical approval and informed consent

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Landsberger M, Gandon S, Meaden S, Rollie C, Chevallereau A, Chabas H. Anti-CRISPR phages cooperate to overcome CRISPR-Cas immunity. Cell. 2018;174(4):908-916.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.058, PMID 30033365.

Choi JH, Yoon J, Chen M, Shin M, Goldston LL, Lee KB. CRISPR/cas based nanobiosensor using plasmonic nanomaterials to detect disease biomarkers. BioChip J. 2025;19(2):167-81. doi: 10.1007/s13206-024-00183-x, PMID 40575544.

Rabiee N, Rabiee M. Engineered metal organic frameworks for targeted CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2025 Mar 12;8(4):1028-49. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.5c00047, PMID 40242591.

Franco BB, Agilandeswari P, Karthik L. Computational screening of potent anti-inflammatory compounds for human mitogen activated protein kinase: a comprehensive and combined in silico approach. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2024 Nov 15;16(6):21-32. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2024v16i6.6023.

Han W, She Q. CRISPR history: discovery characterization and prosperity. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2017;152:1-21. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.10.001, PMID 29150001.

Troder SE, Zevnik B. History of genome editing: from meganucleases to CRISPR. Lab Anim. 2022;56(1):60-8. doi: 10.1177/0023677221994613, PMID 33622064.

Tao S, Hu C, Fang Y, Zhang H, Xu Y, Zheng L. Targeted elimination of vancomycin resistance gene vanA by CRISPR-Cas9 system. BMC Microbiol. 2023;23(1):380. doi: 10.1186/s12866-023-03136-w, PMID 38049763.

Lin Y, Wu J, Gu W, Huang Y, Tong Z, Huang L. Exosome liposome hybrid nanoparticles deliver CRISPR/Cas9 system in MSCs. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2018;5(4):1700611. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700611, PMID 29721412.

Javed M, Hussain S, Khan MA, Tajammal A, Fatima H, Amjad M. Potential of scorpion venom for the treatment of various diseases. Int J Chem Res. 2022 Jul;6(3):1-9. doi: 10.22159/ijcr.2022v6i3.204.

Dwivedi J, Kaushal S, Jeslin D, Karpagavalli L, Kumar R, Dev D. Gene augmentation techniques to stimulate wound healing process: progress and prospects. Curr Gene Ther. 2024 Oct 23;25(4):394-416. doi: 10.2174/0115665232316799241008073042, PMID 39444185.

Xia Y, Sun L, Liang Z, Guo Y, Li J, Tang D. The construction of a PAM-less base editing toolbox in Bacillus subtilis and its application in metabolic engineering. Chem Eng J. 2023 Aug 1;469:143865. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2023.143865.

Fogleman S, Santana C, Bishop C, Miller A, Capco DG. CRISPR/Cas9 and mitochondrial gene replacement therapy: promising techniques and ethical considerations. Am J Stem Cells. 2016;5(2):39-52. PMID 27725916.

Fokum E, Zabed HM, Guo Q, Yun J, Yang M, Pang H. Metabolic engineering of bacterial strains using CRISPR/Cas9 systems for biosynthesis of value added products. Food Biosci. 2019 Apr;28:125-32. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2019.01.003.

Shin JW, Kim KH, Chao MJ, Atwal RS, Gillis T, MacDonald ME. Permanent inactivation of huntington’s disease mutation by personalized allele specific CRISPR/Cas9. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(20):4566-76. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw286, PMID 28172889.

Wang G, Li J. Review analysis and optimization of the CRISPR Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 system. Med Drug Discov. 2021;9:100080. doi: 10.1016/j.medidd.2021.100080.

Yang H, Wang J, Zhao M, Zhu J, Zhang M, Wang Z. Feasible development of stable HEK293 clones by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated site specific integration for biopharmaceuticals production. Biotechnol Lett. 2019;41(8-9):941-50. doi: 10.1007/s10529-019-02702-5, PMID 31236787.

Ameya KP, Sekar D. Letter to the editor on targeted gene therapy for cancer: the impact of microRNA multipotentiality. Med Oncol. 2024 Nov 5;41(12):307. doi: 10.1007/s12032-024-02550-y, PMID 39500782.

Billon P, Bryant EE, Joseph SA, Nambiar TS, Hayward SB, Rothstein R. CRISPR-mediated base editing enables efficient disruption of eukaryotic genes through induction of stop codons. Mol Cell. 2017;67(6):1068-1079.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.008, PMID 28890334.

Jiang L, Ingelshed K, Shen Y, Boddul SV, Iyer VS, Kasza Z. CRISPR/Cas9-induced DNA damage enriches for mutations in a p53-linked interactome: implications for CRISPR based therapies. Cancer Res. 2022;82(1):36-45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-1692, PMID 34750099.

Santiago Fernandez O, Osorio FG, Quesada V, Rodriguez F, Basso S, Maeso D. Development of a CRISPR/Cas9-based therapy for hutchinson gilford progeria syndrome. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):423-6. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0338-6, PMID 30778239.

Gao J, Luo T, Lin N, Zhang S, Wang J. A new tool for CRISPR-Cas13A-based cancer gene therapy. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020 Sep 16;19:79-92. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2020.09.004, PMID 33102691.

Ravichandran M, Maddalo D. Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for advancing precision medicine in oncology: from target discovery to disease modeling. Front Genet. 2023 Oct 16;14:1273994. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1273994, PMID 37908590.

Huang YY, Zhang XY, Zhu P, Ji L. Development of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated technology for potential clinical applications. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10(18):5934-45. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i18.5934, PMID 35949837.

Ansori AN, Antonius Y, Susilo RJ, Hayaza S, Kharisma VD, Parikesit AA. Application of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology in various fields: a review. Narra J. 2023;3(2):e184. doi: 10.52225/narra.v3i2.184, PMID 38450259.

Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157(6):1262-78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010, PMID 24906146.

Goldberg GW, Marraffini LA. Resistance and tolerance to foreign elements by prokaryotic immune systems curating the genome. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(11):717-24. doi: 10.1038/nri3910, PMID 26494050.

Kolanu ND. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing: curing genetic diseases by inherited epigenetic modifications. Glob Med Genet. 2024;11(1):113-22. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-1785234, PMID 38560484.

SS, Augustine D, Mushtaq S, Baeshen HA, Ashi H, Hassan RN. Revitalizing oral cancer research: Crispr-Cas9 technology the promise of genetic editing. Front Oncol. 2024 Jun 10;14:1383062. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1383062, PMID 38915370.

Rabaan AA, Al Saihati H, Bukhamsin R, Bakhrebah MA, Nassar MS, Alsaleh AA. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in cancer treatment: a future direction. Curr Oncol. 2023;30(2):1954-76. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30020152, PMID 36826113.

Park SH, Bao G. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing for curing sickle cell disease. Transfus Apher Sci. 2021;60(1):103060. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2021.103060, PMID 33455878.

Lipert BA, Siemens KN, Khan A, Airey R, Dam GH, Lu M. CRISPR screens with trastuzumab emtansine in HER2-positive breast cancer cell lines reveal new insights into drug resistance. Breast Cancer Res. 2025;27(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s13058-025-02000-1, PMID 40165206.

Benfatto S, Sercin O, Dejure FR, Abdollahi A, Zenke FT, Mardin BR. Uncovering cancer vulnerabilities by machine learning prediction of synthetic lethality. Mol Cancer. 2021;20(1):111. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01405-8, PMID 34454516.

Davis DJ, Yeddula SG. CRISPR advancements for human health. Mo Med. 2024;121(2):170-6. PMID 38694604.

Frangoul H, Altshuler D, Cappellini MD, Chen YS, Domm J, Eustace BK. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jan 21;384(3):252-60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031054, PMID 33283989.

Ginn SL, Amaya AK, Alexander IE, Edelstein M, Abedi MR. Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide to 2017: an update. J Gene Med. 2018;20(5):e3015. doi: 10.1002/jgm.3015, PMID 29575374.

Wang D, Tai PW, Gao G. Adeno associated virus vector as a platform for gene therapy delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(5):358-78. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0012-9, PMID 30710128.

Maeder ML, Stefanidakis M, Wilson CJ, Baral R, Barrera LA, Bounoutas GS. Development of a gene editing approach to restore vision loss in leber congenital amaurosis type 10. Nat Med. 2019;25(2):229-33. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0327-9, PMID 30664785.

Pan X, Veroniaina H, Su N, Sha K, Jiang F, Wu Z. Applications and developments of gene therapy drug delivery systems for genetic diseases. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2021;16(6):687-703. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2021.05.003, PMID 35027949.

Kumar SR, Markusic DM, Biswas M, High KA, Herzog RW. Clinical development of gene therapy: results and lessons from recent successes. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2016 May 25;3:16034. doi: 10.1038/mtm.2016.34, PMID 27257611.

Huang J, Zhou Y, Li J, Lu A, Liang C. CRISPR/Cas systems: delivery and application in gene therapy. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022 Nov 22;10:942325. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.942325, PMID 36483767.

Luiz MT, Dutra JA, Tofani LB, De Araujo JT, Di Filippo LD, Marchetti JM. Targeted liposomes: a nonviral gene delivery system for cancer therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(4):821. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14040821, PMID 35456655.

Yin X, Harmancey R, McPherson DD, Kim H, Huang SL. Liposome based carriers for CRISPR genome editing. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):12844. doi: 10.3390/ijms241612844, PMID 37629024.

Rittiner J, Cumaran M, Malhotra S, Kantor B. Therapeutic modulation of gene expression in the disease state: treatment strategies and approaches for the development of next-generation of the epigenetic drugs. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022 Oct 17;10:1035543. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1035543, PMID 36324900.

Abdelnour SA, Xie L, Hassanin AA, Zuo E, Lu Y. The potential of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing as a treatment strategy for inherited diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Dec 15;9:699597. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.699597, PMID 34977000.

Sekine R, Kawata T, Muramoto T. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated targeting of multiple genes in dictyostelium. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8471. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26756-z, PMID 29855514.

He J, Biswas R, Bugde P, Li J, Liu DX, Li Y. Application of CRISPR-Cas9 system to study biological barriers to drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(5):894. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14050894, PMID 35631480.

Munoz Fontela C, Mandinova A, Aaronson SA, Lee SW. Emerging roles of p53 and other tumour suppressor genes in immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(12):741-50. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.99, PMID 27667712.

Kim Y, Lee HM. CRISPR-Cas system is an effective tool for identifying drug combinations that provide synergistic therapeutic potential in cancers. Cells. 2023;12(22):2593. doi: 10.3390/cells12222593, PMID 37998328.

Ali NM. Role of CRISPR-Cas systems in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease and precision periodontal therapy. Trends Pharm Biotechnol. 2024;2(2):38-49. doi: 10.57238/tpb.2024.153196.1022.

Kazemian P, Yu SY, Thomson SB, Birkenshaw A, Leavitt BR, Ross CJ. Lipid-Nanoparticle based delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing components. Mol Pharm. 2022;19(6):1669-86. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.1c00916, PMID 35594500.

Nayak V, Patra S, Singh KR, Ganguly B, Kumar DN, Panda D. Advancement in precision diagnosis and therapeutic for triple negative breast cancer: harnessing diagnostic potential of CRISPR-cas and engineered CAR T-cells mediated therapeutics. Environ Res. 2023;235:116573. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.116573, PMID 37437865.

Frangoul H, Altshuler D, Cappellini MD, Chen YS, Domm J, Eustace BK. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):252-60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031054, PMID 33283989.

Hussain W, Mahmood T, Hussain J, Ali N, Shah T, Qayyum S. CRISPR/Cas system: a game changing genome editing technology to treat human genetic diseases. Gene. 2019 Feb 15;685:70-5. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.10.072, PMID 30393194.

Liu J, Lu J, Yao B, Zhang Y, Huang S, Chen X. Construction of humanized CYP1A2 rats using CRISPR/Cas9 to promote drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic research. Drug Metab Dispos. 2023 Oct 26;52(1):56-62. doi: 10.1124/dmd.123.001500, PMID 37884392.

Lu J, Liu J, Guo Y, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Wang X. CRISPR-Cas9: a method for establishing rat models of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11(10):2973-82. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.01.007, PMID 34745851.

Maduelosi BI. The impact of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) in pharmacy; 2024. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/123449.

Aimo A, Castiglione V, Rapezzi C, Franzini M, Panichella G, Vergaro G. RNA-targeting and gene editing therapies for transthyretin amyloidosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19(10):655-67. doi: 10.1038/s41569-022-00683-z, PMID 35322226.

Yin H, Song CQ, Dorkin JR, Zhu LJ, Li Y, Wu Q. Therapeutic genome editing by combined viral and non-viral delivery of CRISPR system components in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(3):328-33. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3471, PMID 26829318.

Desai DA, Schmidt S, Cristofoletti R. A quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) platform for preclinical to clinical translation of in vivo CRISPR-Cas therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2024 Sep 20;15:1454785. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1454785, PMID 39372210.

Wei T, Cheng Q, Farbiak L, Anderson DG, Langer R, Siegwart DJ. Delivery of tissue targeted scalpels: opportunities and challenges for in vivo CRISPR/Cas-based genome editing. ACS Nano. 2020;14(8):9243-62. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c04707, PMID 32697075.

Prajapati RN, Bhushan B, Singh K, Chopra H, Kumar S, Agrawal M. Recent advances in pharmaceutical design: unleashing the potential of novel therapeutics. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2024;25(16):2060-77. doi: 10.2174/0113892010275850240102105033, PMID 38288793.

Wang SW, Gao C, Zheng YM, Yi L, Lu JC, Huang XY. Current applications and future perspective of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01518-8, PMID 35189910.

Dubey AK, Mostafavi E. Biomaterials mediated CRISPR/Cas9 delivery: recent challenges and opportunities in gene therapy. Front Chem. 2023 Sep 28;11:1259435. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2023.1259435, PMID 37841202.

Piergentili R, Del Rio A, Signore F, Umani Ronchi FU, Marinelli E, Zaami S. CRISPR-Cas and its wide ranging applications: from human genome editing to environmental implications technical limitations hazards and bioethical issues. Cells. 2021;10(5):969. doi: 10.3390/cells10050969, PMID 33919194.

Chanchal DK, Chaudhary JS, Kumar P, Agnihotri N, Porwal P. CRISPR-based therapies: revolutionizing drug development and precision medicine. Curr Gene Ther. 2024;24(3):193-207. doi: 10.2174/0115665232275754231204072320, PMID 38310456.

Selvakumar SC, Preethi KA, Ross K, Tusubira D, Khan MW, Mani P. CRISPR/Cas9 and next generation sequencing in the personalized treatment of cancer. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01565-1, PMID 35331236.

Kolanu ND. CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing: curing genetic diseases by inherited epigenetic modifications. Glob Med Genet. 2024;11(1):113-22. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-1785234, PMID 38560484.

Wang HX, Li M, Lee CM, Chakraborty S, Kim HW, Bao G. CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing for disease modeling and therapy: challenges and opportunities for nonviral delivery. Chem Rev. 2017;117(15):9874-906. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00799, PMID 28640612.

Mao K, Tan H, Cong X, Liu J, Xin Y, Wang J. Optimized lipid nanoparticles enable effective CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in dendritic cells for enhanced immunotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2025;15(1):642-56. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2024.08.030, PMID 40041907.

Xiong B, Li Z, Liu L, Zhao D, Zhang X, Bi C. Genome editing of ralstonia eutropha using an electroporation based CRISPR-Cas9 technique. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11(1):172. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1170-4, PMID 29951116.

Asmamaw Mengstie MA. Viral vectors for the in vivo delivery of CRISPR components: advances and challenges. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022 May 12;10:895713. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.895713, PMID 35646852.

Li H, Yang Y, Hong W, Huang M, Wu M, Zhao X. Applications of genome editing technology in the targeted therapy of human diseases: mechanisms advances and prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):1. doi: 10.1038/s41392-019-0089-y, PMID 32296011.

Hou J, He Z, Liu T, Chen D, Wang B, Wen Q. Evolution of molecular targeted cancer therapy: mechanisms of drug resistance and novel opportunities identified by CRISPR-Cas9 screening. Front Oncol. 2022 Mar 17;12:755053. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.755053, PMID 35372044.

Gallego C, Goncalves MA, Wijnholds J. Novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of retinal degenerative diseases: focus on CRISPR/Cas-based gene editing. Front Neurosci. 2020 Aug 20;14:838. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00838, PMID 32973430.

Papasavva P, Kleanthous M, Lederer CW. Rare opportunities: CRISPR/Cas-based therapy development for rare genetic diseases. Mol Diagn Ther. 2019;23(2):201-22. doi: 10.1007/s40291-019-00392-3, PMID 30945166.

Saw PE, Cui GH, Xu X. Nanoparticles mediated CRISPR/Cas gene editing delivery system. ChemMedChem. 2022;17(9):e202100777. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202100777, PMID 35261159.

Yadalam PK, Arumuganainar D, Anegundi RV, Shrivastava D, Alftaikhah S, Almutairi HA. CRISPR-cas-based adaptive immunity mediates phage resistance in periodontal red complex pathogens. Microorganisms. 2023;11(8):2060. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11082060, PMID 37630620.

Ameya KP, Sekar D. Letter to the editor on targeted gene therapy for cancer: the impact of microRNA multipotentiality. Med Oncol. 2024;41(12):307. doi: 10.1007/s12032-024-02550-y, PMID 39500782.

Teh SW, Elderdery A, Rampal S, Subbiah SK, Mok PL. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 transfection of guide RNA targeting on MMP9 as anti-cancer therapy in human cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma cell line A431. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2023;27(4):255-62. doi: 10.5114/wo.2023.135364, PMID 38405210.

Gao NC, Wang R, Zhang L, Yue C. Visualization analysis of CRISPR gene editing knowledge map based on citespace. Biol Bull Russ Acad Sci. 2021;48(6):705-20. doi: 10.1134/S1062359021060108, PMID 34955625.

Wang L, Zhou B, Li D. Genome editing technology and medical applications. Sci China Life Sci. 2024;67(12):2537-9. doi: 10.1007/s11427-024-2773-3, PMID 39560684.

Li B, Niu Y, Ji W, Dong Y. Strategies for the CRISPR-based therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2020;41(1):55-65. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2019.11.006, PMID 31862124.

Tachibana Iimori R, Tabara Y, Kusuhara H, Kohara K, Kawamoto R, Nakura J. Effect of genetic polymorphism of OATP-C (SLCO1B1) on lipid lowering response to HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2004;19(5):375-80. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.19.375, PMID 15548849.

Azrak RG, Yu J, Pendyala L, Smith PF, Cao S, Li X. Irinotecan pharmacokinetic and pharmacogenomic alterations induced by methylselenocysteine in human head and neck xenograft tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4(5):843-54. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0315, PMID 15897249.

Sullivan KE, Kumar S, Liu X, Zhang Y, De Koning E, Li Y. Uncovering the roles of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase in fatty acid induced steatosis using human cellular models. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):14109. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-17860-2, PMID 35982095.

Vora LK, Gholap AD, Jetha K, Thakur RR, Solanki HK, Chavda VP. Artificial intelligence in pharmaceutical technology and drug delivery design. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(7):1916. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15071916, PMID 37514102.

Mayorga Ramos A, Zuniga Miranda J, Carrera Pacheco SE, Barba Ostria C, Guaman LP. CRISPR-Cas based antimicrobials: design challenges and bacterial mechanisms of resistance. ACS Infect Dis. 2023;9(7):1283-302. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00649, PMID 37347230.

Mashel TV, Tarakanchikova YV, Muslimov AR, Zyuzin MV, Timin AS, Lepik KV. Overcoming the delivery problem for therapeutic genome editing: current status and perspective of non-viral methods. Biomaterials. 2020 Nov;258:120282. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120282, PMID 32798742.

Sahel DK, Vora LK, Saraswat A, Sharma S, Monpara J, D’Souza AA. CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing for tissue specific in vivo targeting: nanomaterials and translational perspective. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10(19):e2207512. doi: 10.1002/advs.202207512, PMID 37166046.

Kuruvilla J, Sasmita AO, Ling AP. Therapeutic potential of combined viral transduction and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in treating neurodegenerative diseases. Neurol Sci. 2018;39(11):1827-35. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3521-0, PMID 30076486.

Brezgin S, Kostyusheva A, Bayurova E, Volchkova E, Gegechkori V, Gordeychuk I. Immunity and viral infections: modulating antiviral response via CRISPR–Cas systems. Viruses. 2021;13(7):1373. doi: 10.3390/v13071373, PMID 34372578.

Ciarimboli G. Overcoming biological barriers: importance of membrane transporters in homeostasis disease and disease treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):7212. doi: 10.3390/ijms24087212, PMID 37108379.

Girardi E, Cesar Razquin A, Lindinger S, Papakostas K, Konecka J, Hemmerich J. A widespread role for SLC transmembrane transporters in resistance to cytotoxic drugs. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16(4):469-78. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0483-3, PMID 32152546.

Shi M, Wang C, Ji J, Cai Q, Zhao Q, Xi W. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of SGLT1 inhibits proliferation and alters metabolism of gastric cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2022 Feb;90:110192. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.110192, PMID 34774990.

Bayanova M, Zhenissova A, Nazarova L, Abdikadirova A, Sapargalieyva M, Malik D. Influence of genetic polymorphisms in CYP3A5, CYP3A4, and MDR1 on tacrolimus metabolism after kidney transplantation. J Clin Med Kazakhstan. 2024;21(2):11-7. doi: 10.23950/jcmk/14511.

Wang Y, Fang Z, Hong M, Yang D, Xie W. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in drug metabolism and disposition implications in cancer chemo resistance. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10(1):105-12. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.09.011, PMID 31993309.

Ottaviano G, Georgiadis C, Gkazi SA, Syed F, Zhan H, Etuk A. Phase 1 clinical trial of CRISPR-engineered CAR19 universal T cells for treatment of children with refractory B cell leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(668):eabq3010. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq3010, PMID 36288281.

McManus M, Frangoul H, Steinberg MH. Crispr based gene therapy for the induction of fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell disease. Expert Rev Hematol. 2024;17(12):957-66. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2024.2429605, PMID 39535263.

Shilbayeh S AR, Adeen IS, Alhazmi, AS, Ibrahim, SF, Enazi, F Shilbayeh SA, Adeen IS, Alhazmi AS, Ibrahim SF, Al Enazi FA, Ghanem EH. The frequency of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4/5 genotypes and the impact of their allele translation and phenoconversion predicted enzyme activity on risperidone pharmacokinetics in Saudi children with autism. Biochem Genet. 2024;62(4):2907-32. doi: 10.1007/s10528-023-10580-w, PMID 38041757.

Wang YJ, Zhang YK, Zhang GN, Al Rihani SB, Wei MN, Gupta P. Regorafenib overcomes chemotherapeutic multidrug resistance mediated by ABCB1 transporter in colorectal cancer: in vitro and in vivo study. Cancer Lett. 2017 Mar 14;396:145-54. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.03.011, PMID 28302530.

Romaine SP, Bailey KM, Hall AS, Balmforth AJ. The influence of SLCO1B1 (OATP1B1) gene polymorphisms on response to statin therapy. Pharmacogenomics J. 2010;10(1):1-11. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.54, PMID 19884908.

Hussain MS, Bisht AS, Ali H, Gupta G. Glutathione responsive nanoparticles for optimized Cas9/sgRNA gene editing delivery. Curr Drug Targets. 2025 Apr 11;26(9):587-90. doi: 10.2174/0113894501370119250409074208, PMID 40231529.

Kumar A, Combe E, Mougene L, Zoulim F, Testoni B. Applications of CRISPR/Cas as a toolbox for hepatitis B virus detection and therapeutics. Viruses. 2024;16(10):1565. doi: 10.3390/v16101565, PMID 39459899.

Xie FW, Peng YH, Chen X, Chen X, Li J, Yu ZY. Regulation and expression of aberrant methylation on irinotecan metabolic genes CES2, UGT1A1 and GUSB in the in vitro cultured colorectal cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2014;68(1):31-7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2013.06.013, PMID 24439671.

Pankowicz FP, Barzi M, Legras X, Hubert L, Mi T, Tomolonis JA. Reprogramming metabolic pathways in vivo with CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to treat hereditary tyrosinaemia. Nat Commun. 2016b;7(1):12642. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12642, PMID 27572891.

Lewis M, Prouzet Mauleon V, Lichou F, Richard E, Iggo R, Turcq B. A genome scale CRISPR knock out screen in chronic myeloid leukemia identifies novel drug resistance mechanisms along with intrinsic apoptosis and MAPK signaling. Cancer Med. 2020;9(18):6739-51. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3231, PMID 38831555.

Fontana AC. Current approaches to enhance glutamate transporter function and expression. J Neurochem. 2015 Sep;134(6):982-1007. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13200, PMID 26096891.

Cring MR, Sheffield VC. Gene therapy and gene correction: targets progress and challenges for treating human diseases. Gene Ther. 2022;29(1-2):3-12. doi: 10.1038/s41434-020-00197-8, PMID 33037407.

Yerrakula G, George SG, D KK, PR, NJ: AVK, Venkatachalam S. Effect of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism of human carboxyl esterase 1 on the bioactivation of dabigatran etexilate. Int J App Pharm. 2022 Sep 7;14(5):208-13. doi:10.22159/ijap.2022v14i5.44682.

Zhang X, Lin Y, Wu Q, Wang Y, Chen GQ. Synthetic biology and genome editing tools for improving PHA metabolic engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2020;38(7):689-700. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.10.006, PMID 31727372.