Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 343-351Original Article

INVESTIGATION OF LEVOMILNACIPRAN NANOSTRUCTURED LIPID CARRIERS FOR CNS DRUG DELIVERY THROUGH INTRANASAL ADMINISTRATION USING RAT MODEL

PARTHIBAN R.1,2, MOTHILAL M.1*

1Department of Pharmaceutics, SRM College of Pharmacy, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur, Tamil Nadu-603203, India. 2Department of Pharmaceutics, Surya School of Pharmacy, Surya Group of Institutions, Surya Nagar, Vikiravandi, Villupuram Tamil Nadu-603203, India

*Corresponding author: Mothilal M.; *Email: mothipharma78@gmail.com

Received: 09 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 12 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aims to enhance the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of levomilnacipran by developing a nanostructured lipid carrier for nasal delivery, bypassing the blood-brain barrier via olfactory and trigeminal pathways to improve drug availability in treating depression.

Methods: The solvent diffusion approach was used to create levomilnacipran nanostructured lipid carriers (LEV-NLC), which was then tuned for different physicochemical properties. The rat model was used to assess the antidepressant effects of optimised levomilnacipran, in conjunction with biochemical assessment of brain monoamines. In addition, this estimated various pharmacokinetic parameters by measuring levomilnacipran levels in brain and blood plasma at different time intervals.

Results: The optimized LEV-NLC showed a particle size of 121 nm, zeta potential of-25 mV, and entrapment efficiency of 88%. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis revealed spherical nanoparticles with uniform morphology. In vitro release studies demonstrated sustained drug release, with cumulative LEV release of 77.21±3.87% at pH 7.4 and 76.32±3.54% at pH 6.0 over 24 h. Pharmacokinetic analysis showed enhanced bioavailability for LEV-NLC (62%) compared to LEV solution (28%), based on plasma AUC values. In behavioural studies, LEV-NLC significantly reduced immobility (by 101 counts), and increased swimming time (by 128 s), climbing time (by 50 s), and locomotor activity (by 193 counts), indicating antidepressant-like effects. Neurochemical analysis revealed significantly increased serotonin (P<0.01) and noradrenaline (P<0.05) levels in the LEV-NLC group, while dopamine levels showed a non-significant increase (P>0.05).

Conclusion: The pharmacokinetic profile of levomilnacipran in the brain and the brain/blood ratio at various time points were both enhanced by the nose-to-brain delivery of the NLC. Therefore, the intranasal administration of levomilnacipran NLC may hold promise as a treatment for depression.

Keywords: Depression, Levomilnacipran, Nanostructured lipid carrier, Design of experiment, Nasal delivery

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54529 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a serious mental disorder characterized by a chronic low mood, pervasive feelings of hopelessness and sadness, reduced self-esteem, disturbed sleep habits, and often, suicidal ideation [1]. The primary factor contributing to depression is the interruption of neurotransmitter transmission in the brain, namely involving norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine [2, 3]. This disruption results from a complex interaction of various social, psychological, and biological elements [4]. A study by the World Health Organization (WHO) indicates that depression is a significant contributor to disability, affecting more than 350 million people worldwide. Depression is linked to suicides, causing around 1 million fatalities each year [5]. The World Mental Health Survey, done across 17 nations, indicates that the average prevalence of depression is 1 in 20 adults [6]. Consequently, most antidepressants enhance the concentration of monoamines at the synapse via several mechanisms.

The efficacy of these antidepressants in treating patients depends on their sustained and prolonged presence in the brain, where they exert their effects [7]. Currently, antidepressants are predominantly delivered orally due to the prolonged nature of the treatment, which extends over many days. However, the efficacy of oral antidepressants is limited due to their inability to properly penetrate the blood-brain barrier. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) and blood-cerebrospinal fluid (BCSF) barrier inhibit the transfer of medicines from the bloodstream into the central nervous system (CNS) [8]. Furthermore, the variability in drug concentration in the bloodstream following oral administration leads to adverse effects, diminished efficacy, and decreased tolerance to the treatment [8].

For several decades, different classes of antidepressants, such as tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), have been utilised in the management of depression. The likelihood of attaining complete remission after the initial dose of an antidepressant is below 30%, and this probability diminishes further after the unsuccessful first antidepressant attempt. Consequently, researchers and pharmaceutical firms are competing to develop effective antidepressant drugs that provide swift and enduring relief.

This is demonstrated by a series of recently approved antidepressant drugs by the FDA during the past three years, including vilazodone, levomilnacipran, vortioxetine, and others in development. These findings underscore the necessity of developing an intranasal nanoformulation capable of delivering antidepressant medication to the brain non-invasively. This would increase the drug's concentration in the brain, hence decreasing the necessary dosage, side effects, and intolerance. In recent years, the intranasal administration method for delivering therapeutic medications to the central nervous system (CNS) has emerged as a novel approach. The olfactory and/or trigeminal nerve system establishes a distinct link between the olfactory epithelium and the central nervous system (CNS), facilitating the delivery of drugs from the nasal cavity to the brain. This circumvents the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and is enabled by the interconnection between these systems [9]. Numerous recent studies have examined the transfer of pharmaceuticals from the nasal cavity to the brain. This approach presents multiple benefits, such as circumventing the blood-brain barrier and hepatic first-pass metabolism, in addition to being non-invasive and facile to administer [9–11]. Recent Advances in Intranasal Administration for Brain-Targeting Delivery: A Comprehensive Review of Lipid-Based Nanoparticles and Stimuli-Responsive Gel Formulations provides an in-depth look at lipid-based nanoparticles and in situ gel systems for enhancing nose-to-brain drug delivery [12, 13]. A study published in Acta Materia Medica in 2024 explored the use of Solutol HS15 micelles for nose-to-brain delivery. The study showed that these micelles had high encapsulation efficiency and stability, and achieved sustained release of the drug, facilitating penetration of drugs in the olfactory epithelium and targeting brain tissues [14].

The selected pharmacological agent for nasal-to-brain delivery in this trial is Levomilnacipran, a selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Levomilnacipran is the more potent variant of racemic milnacipran, with 90% oral bioavailability and a plasma half-life of 12 h. Levomilnacipran offers a favorable serotonin-to-norepinephrine ratio; however, oral administration may result in numerous side effects, including increased blood pressure and heart rate, constipation, restlessness, tremors, excessive sweating, nausea, headaches, and sleep disturbances [15, 16].

Researchers have developed and examined nanostructured lipid carriers loaded with Levomilnacipran. These carriers are engineered to prolong the duration of the drug's retention in the nasal cavity and diminish its removal via the nasal mucociliary system. This is performed to improve the drug's absorption by the nasal epithelium, including the olfactory areas, for efficient delivery from the nose to the brain [17, 18].

Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) are lipid-based nanocarriers that represent a novel class of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs). Their hybrid lipid core comprises a combination of a solid lipid and a liquid lipid that are spatially incompatible. NLCs present numerous benefits, such as the capability to encapsulate both hydrophobic and hydrophilic pharmaceuticals, facilitate sustained drug release, safeguard against chemical, photochemical, or oxidative degradation, immobilize the drug within a solid matrix, enable straightforward scale-up and manufacturing, maintain low costs, and exhibit minimal toxicity. Moreover, NLCs can encapsulate substantial quantities of pharmaceuticals and address the challenge of drug release from the lipid core [19].

This work aimed to improve a nano-sized drug delivery system for intranasal administration of LEV to the brain and assess its antidepressant efficacy using pharmacodynamic and biochemical analyses in animals. The additional aim of this study was to assess the pharmacokinetics of LEV-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers in the brain and plasma, respectively, to correlate with the results of pharmacodynamic and biochemical investigations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The acquisition of levomilnacipran was made by Sigma Aldrich Co., Ltd. The excipients utilised in the formulation of the nanoparticles were Glycerol monooleate (GMO) and Oleic acid, which were procured from Metro Labs Ltd., Chennai. BASF India Ltd. generously provided Lutrol® F 68 (Poloxamer 188). The ethanol, acetone, and other chemicals were of high-quality analytical reagent grade.

Animals

Adult male Wistar rats (aged 6–8 w) weighing approximately 250 g were selected for pharmacodynamic, biochemical and brain pharmacokinetic studies. The study was approved by the IAEC, Surya School of Pharmacy. Vikiravandi, TamilNadu, India. The IAEC approval number is (932/Po/Pe/S/06/CPCSEA).

Preparation of NLC

Levomilnacipran-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (LEV-NLCs) were formulated using the solvent diffusion method. A lipid phase was prepared by melting 500 μL of glycerol monostearate (GMS) and 50 μl of oleic acid in a 10:1 (v/v) ratio, into which 1 mg of levomilnacipran was incorporated. This mixture was dissolved in a 1:1 (v/v) blend of ethanol and acetone (5 ml each), and heated in a water bath at 35 °C with magnetic stirring at 500 rpm for 10 min until a clear lipid-drug solution was achieved.

The resulting organic solution was rapidly introduced into 10 ml of an aqueous Poloxamer 188 solution (0.5% w/v), maintained at 25 °C, and emulsified using probe sonication at 40% amplitude (~70 watts) for 2 min (pulsed at 5 seconds on, 2 seconds off), forming a primary nanoemulsion.

To enhance mucoadhesiveness and stability, 10 ml of a chitosan solution (2% w/v in 2% acetic acid) was added dropwise under continuous stirring at 400 rpm. The final mixture was subjected to bath sonication at 40 kHz for 30 min, resulting in a homogenous nanosuspension.

Physiochemical evaluation

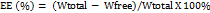

LEV NLC was characterized for particle size, zeta potential, surface morphology and entrapment efficiency (EE). The particle size and zeta potential were measured by Zetasizer (model: Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments, UK). The surface morphology was observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a negative-staining approach. The EE was determined using the following equation,

. In vitro drug release of LEV-NLC was conducted in vitro at pH 7.4 (physiological pH) and pH 6.0 (nasal mucosal pH).

. In vitro drug release of LEV-NLC was conducted in vitro at pH 7.4 (physiological pH) and pH 6.0 (nasal mucosal pH).

Pharmacodynamic investigations

Stress-induced model

Forced swimming test

The forced swimming test was conducted to evaluate and compare the antidepressant efficacy of intranasal LEV-NLC with that of oral/intranasal LEV [20, 21]. Rats were let to swim in a cylindrical glass container filled with water up to the 30 cm mark, compelling them to swim and/or float without the assistance of their tails and rear limbs. Two swimming sessions were undertaken, including a 15-minute pretest prior to drug administration to acclimatize and train the rats for the testing scenario. The test session was conducted for 5 min on day 16, one hour after the final dose. Test sessions were filmed on camera, documenting behavioural swimming, climbing, and immobility.

The locomotor activity of all four groups was documented using a digital photoactometer in a closed box (30 cm × 30 cm) fitted with infrared light-sensitive photocells, 0.5 h following the test session on the 16th day. The activity was quantified as total counts during a 5-minute interval per rat. For the FST, the rats were separated into four groups, each including six rats. The doses were determined by extrapolating the therapeutic dose for people (50 mg/kg/day, oral bioavailability 80%) to rats based on body surface area, utilising a dose conversion factor of 0.018 from humans to rats [22].

Rats in Group 1 and Group 2 received LEV-NLCs (equal to 5 mg/kg/day LEV) and LEV solution (equivalent to 5 mg/kg/day) intranasally for 16 days, respectively. Group 3 received LEV solution (0.5 ml, corresponding to 5 mg/kg/day) via oral gavage for 16 days. Group 4 acted as the control and was administered 100 ml of normal saline solution intranasally for 16 days. For the intranasal method, LEV/lEV NLCs were dissolved or dispersed in 100 ml of normal saline and delivered (50 µl** per nostril) using a polyethene tube (0.1 mm) inserted 5 mm deep into each nostril. The rats were anaesthetized before to dosage and meticulously observed till recovery. All test groups were compared to the control group.

Drug-induced model

Reserpine reversal test (RRT)

In drug-induced models of behavioural depression, the alleviation of reserpine-induced immobility, ptosis, hypothermia, and sedation is utilized to assess the efficacy of antidepressants [23]. Analogous to FST, the rats were categorized into four groups, each including six rats, and were provided identical doses of each formulation. Each group of rats received an intraperitoneal injection of reserpine solution (2 mg/kg). After one hour, the experimental groups were administered their respective treatments, and the reduction in reserpine-induced palpebral ptosis, diarrhea, hypothermia, and immobility was assessed in individual rats from each group at 2-, 4-, and 8-hours’ post-treatment, respectively. Diarrhea and ptosis were assessed using arbitrary scores, graded from 0 to 2, where 0 indicates no symptoms, 2 denotes severe symptoms, and 1 represents moderate severity.

Biochemical estimation of serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine

The rats were euthanized following pharmacodynamic studies, and the concentrations of three neurotransmitters, serotonin, noradrenaline, and dopamine were measured in the brain[24]. A rat brain tissue extract was made in the initial phase. The brains of rats were taken, and the subcortical regions were separated from the cortex and weighed. The tissue was homogenized with 4 cc of HCl-butanol (0.37:1) at 0 °C. The material underwent centrifugation at 1150g at 0 °C for 10 min. An aliquot of supernatant (1 ml) was extracted and combined with heptane-HCl (1.5–0.3 ml, 0.1 M) at 0 °C. After 10 min of vortexing, the tube was centrifuged at 700g for 10 min at 0 °C. 0.25 cc of the aqueous layer was utilized for the measurement of the neurotransmitter as outlined below. To estimate serotonin (5 HT), 0.3 ml of O-phthaldialdehyde reagent (20 mg/100 ml concentrated HCl) was added to the aqueous phase (0.25 ml) as previously reported and heated at 100 °C for 10 min. All materials were equilibrated to room temperature, and absorbance was recorded at 360–470 nm (excitation/emission) using the spectrofluorimeter (Spectrofluorimeter RF5301-PC, Shimadzu, Japan).

The unreacted tissue sample was generated using the identical technique, without the incorporation of O-phthaldialdehyde reagent. To estimate nor-adrenaline and dopamine, 0.06 ml of 0.4 M HCl and 0.1 ml of EDTA sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.9) were added to 0.25 ml of fresh aqueous phase. Additionally, the samples underwent oxidation with the addition of 0.15 ml of iodine solution (0.1 ml in ethanol). After 2 min, the reaction was terminated with 0.15 ml of Na2SO3 solution [Na2SO3 (0.5 g in 2 ml H2O)+NaOH (18 ml, 5 M)]. After 15 min, 0.1 ml of acetic acid (10 M) was introduced to the reaction mixture and heated at 100 °C for 6 min. The samples were equilibrated to room temperature, and absorbance was measured at 395–485 nm for noradrenaline and 330–375 nm for dopamine. The blank samples were prepared by sequentially combining all the chemicals of the oxidation step in reverse order (Na2SO3 solution preceding iodine). The internal standards were prepared by incorporating 250 µg of serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenaline into 0.5 ml of distilled water: HCl-butanol (1:2). Distilled water: HCl-butanol (1:2) was utilized for internal reagent blank samples.

Blood and brain pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of blood and brain were conducted where Group 1 rats received LEV-NLCs (equal to 5 mg/kg/day LEV) via intravenous administration through the tail vein. Rats in Groups 2 and 3 received intranasal administration of LEV solution and LEV-NLC, both equivalent to 5 mg/kg/day of LEV. The pharmacokinetic investigations were conducted for 72 h to elucidate the elimination phase for the determination of several pharmacokinetic parameters. Blood (100 ml) was collected by the tail vein into EDTA-coated tubes and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min to isolate the plasma (50 µl).

LEV was isolated from plasma by liquid extraction, utilising citalopram as an internal reference for quantification by reverse-phase HPLC [25, 26]. At predetermined sampling time points, a 2 pagetmL aliquot was withdrawn for analysis and replaced with an equal amount of fresh phosphate buffer for 24 h. DVF was determined in the samples by reverse-phase HPLC with UV detection at 230 nm using a mobile phase containing a mixture of buffer and acetonitrile in a ratio of 70: 30. The buffer consists of 10 mmol potassium dihydrogen phosphate and 2 mmol 1-octane sulphonic acid sodium salt (pH 6.0). The rats were euthanized at scheduled intervals using cervical dislocation for brain harvest. The brain was extracted from the skull, rinsed with normal saline to eliminate blood stains and impurities, weighed, and preserved at-80 °C for future use. The brain was homogenized using a tissue homogenizer with 2 ml of normal saline to obtain a uniform suspension. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to separate cellular debris. The clear supernatant was carefully collected and utilized for the quantification of drug levels by HPLC, as well as for the biochemical assessment of monoamine neurotransmitters, ensuring precise and consistent analytical results. A modest volume of brain tissue homogenate (200 ml) was utilized to estimate the concentration of LEV in the brain.

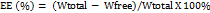

The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and the time to attain maximum plasma concentration (Tmax) were derived from the plasma concentration-time profile. The drug targeting efficacy of the LEV NLCs following intranasal delivery was determined by the drug targeting efficiency (DTE)[26].

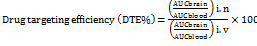

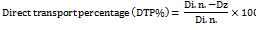

Direct transport percentage (DTP%) of the nose to the brain was calculated as follows:

Where Dz = (Di. v./Pi. v.)×Pi. n. Dz is the brain AUC fraction contributed by systemic circulation through the BBB following intranasal administration.

Di. v. is the AUC0-72 h (brain) intravenous route

Pi. v. is the AUC0-72 h (blood) intravenous route

Di. n. is the AUC0-72h (brain) intranasal route

Pi. n. is the AUC0-72h(blood) intanasal route

Statistical analysis

All the experiments are conducted at least in triplicate and results are expressed as mean±standard error (SE) for all the in vivo data. Other results are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). Statistical comparison of mean values was performed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s t-test. The P<0.05 was considered significant and P<0.01 was considered highly significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Preparation and characterization of LEV-NLCs

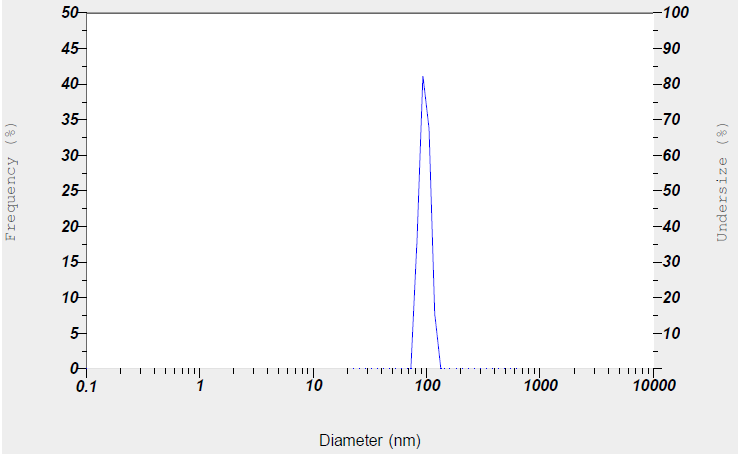

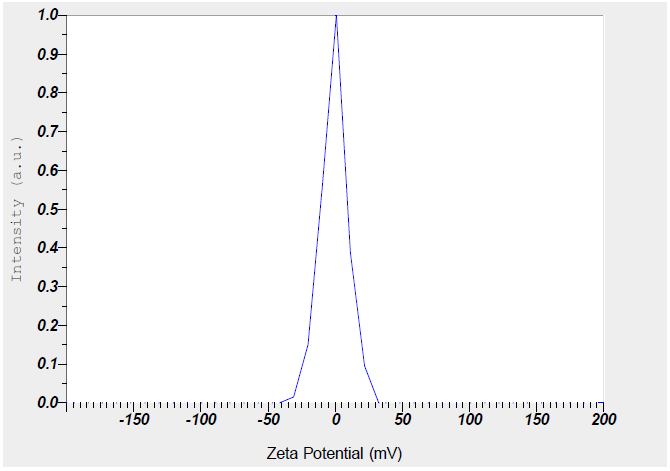

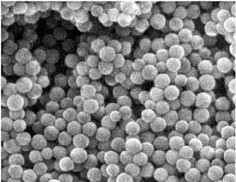

The preparation of LEV-NLC was conducted using the solvent diffusion approach. Glycerol Monostearate (GMS), being a solid lipid, forms the solid matrix. GMS is typically used as the solid lipid component of the NLC. It provides the structural backbone of the nanoparticle. Being solid at both room and body temperature, it creates a stable matrix that can encapsulate the drug. The crystalline structure of a solid lipid matrix can sometimes lead to drug expulsion during storage. However, when mixed with a liquid lipid like oleic acid, GMS can form a less ordered, more amorphous structure. This "imperfect crystal" structure offers more space for drug molecules to be entrapped, leading to higher drug loading capacity and reduced drug leakage. The prepared NLCs were characterized for particle size, zeta potential and surface morphology. The particle size and the Zeta potential of the LEV-NLCs were found to be 121 nm and-25 mV, respectively (fig. 1 and 2) and the NLCs are very well spherical (fig. 3).

Fig. 1: Particle size of levomilnacipran NLC

Fig. 2: Zeta potential of levomilnacipran NLC

Fig. 3: TEM image of levomilnacipran NLC at 500 nm magnification

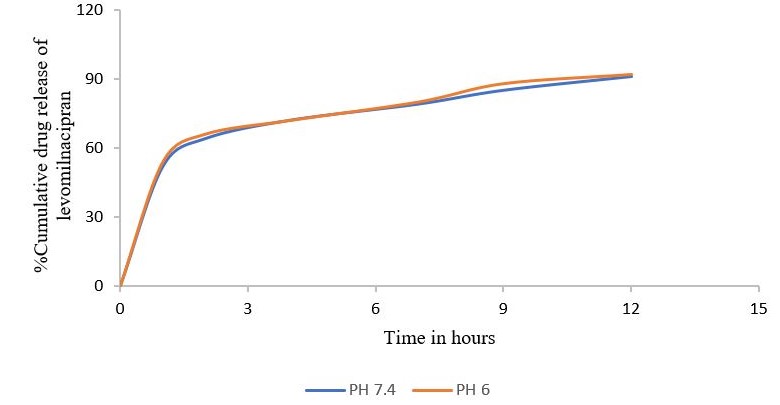

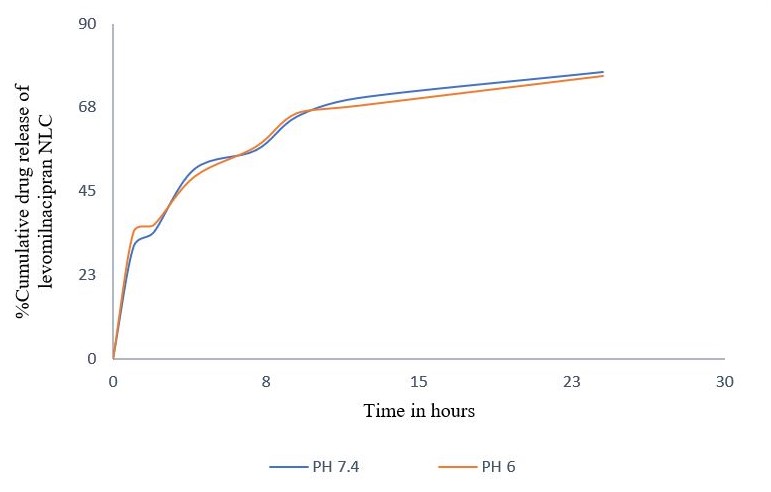

Numerous studies indicate that nanoparticles smaller than 200 nm are readily translocated via the olfactory membrane transcellularly by olfactory neurons to the brain [25, 26]. A zeta potential value of-25 mV indicates a stable system. The % EE was determined to be 88%, indicating that LEV can be effectively encapsulated within the NLCs. The in vitro release of LEV from optimised LEV-NLCs was conducted at pH 7.4 (physiological pH) and pH 6.0 (nasal mucosal pH) (fig. 4 and 5). The release exhibited a biphasic pattern, with 30% (pH 7.4) and 34% (pH 6.0) of the medication released within 1 h, followed by a sustained release characteristic lasting over 24 h. The cumulative percentage release of LEV from LEV-NLC was 77.21±3.87% at pH 7.4 and 76.32±3.54% at pH 6.0 during 24 h. The initial rapid drug release was likely attributable to the release of LEV that was weakly bound to the nanoparticle surface, while the subsequent gradual release may result from LEV being released from the core of the NLC. To statistically assess the in vitro drug release profile of LEV and LEV-NLC at pH 7.4 and 6.0, the similarity factor (f₂) is calculated using the formula: f2=50log([1+1n∑t=1n(Rt−Tt)2]−.5X10). If f₂≥ 50, the two dissolution profiles are considered similar. The f2 value for the two formulations was found to be 84, which demonstrates that it is comparable and no notable variation in their release profile at pH 7.4 compared to pH 6.0.

Fig. 4: Cumulative percentage drug release of levomilnacipran

Fig. 5: Cumulative percentage drug release of levomilnacipran NLC

Pharmacodynamic studies

A toxicity study was carried out and the oral LD50 in rats was observed to be 250 mg/kg. The FST is the most commonly utilized preclinical test for evaluating the antidepressant efficacy of investigational treatment agents in rodents. Since its inception in the early 1970s, the FST has been persistently employed to evaluate the antidepressant efficacy of novel drugs [27]. In forced swim models, animals are driven to swim in an inescapable environment, where, after an initial fight, the mice adopt an immobile posture and float passively with their heads above water, exhibiting no further movement. This immobility was selectively diminished by a range of antidepressant medications [20, 27]. The significance of all three components of the FST, along with locomotor activity, was assessed.

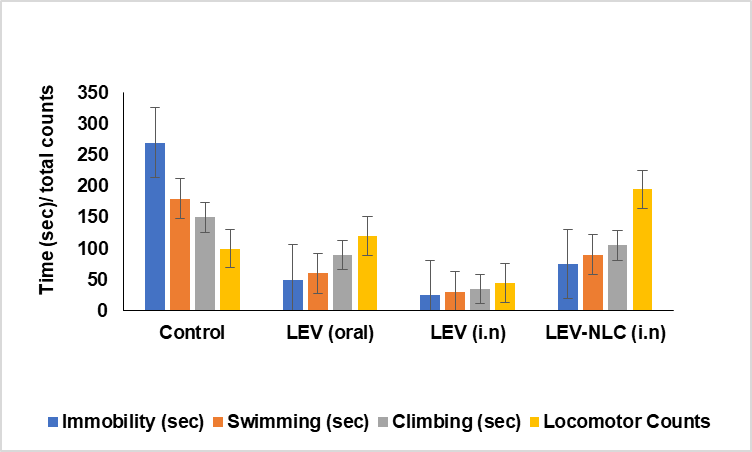

The 16-day chronic antidepressant treatment regimen was implemented, as it is established that the therapeutic effects of antidepressants require several days or weeks to manifest [21, 28]. The 16-day medication administration according to the previously documented procedure [24]. The control group, comprising depressed rats, had the greatest immobility and the lowest frequencies of swimming, climbing, and locomotor activity. The prolonged administration of LEV-NLCs markedly diminished immobility by 101 from 270 counts, increased swimming time by 128 from 50 seconds, climbing time by 50 from 16 seconds, and locomotor activity by 193 from 84 countsrelative to the control group (fig. 6). This indicates that LEV-NLCs maintained consistent therapeutic concentrations of LEV in the brain, alleviating depressive symptoms. Several previous research has established that an enhancement in swimming and climbing behaviours in the FST transpires solely when antidepressant medication elevates the amounts of neurotransmitters, specifically serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, in the nerve terminals [25]. Conversely, treatment with the LEV solution reduced immobility and enhanced swimming duration (P<0.05), although did not significantly improve climbing time or locomotor count compared to the depressed control group. The short residence duration of the LEV solution in the nasal cavity may have resulted in insufficient maintenance of therapeutic levels of LEV in the brain for optimal antidepressant efficacy. The oral administration of LEV yielded a less effective antidepressant response compared to LEV (intranasally) and LEV-NLCs. LEV-NLC significantly reduced immobility time compared to the control (p<0.01), with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 3.53; 95% CI for mean difference: 26.1–63.9 seconds). Nevertheless, LEV (oral) reduced the immobility of rodents (P<0.05), but failed to significantly improve swimming, climbing, and locomotor activity counts. This may result from the synergistic effects of inadequate LEV penetration into the brain, gastrointestinal breakdown, first-pass metabolism, and active efflux by P-glycoprotein and other efflux transporters located at the blood-brain barrier. Numerous studies indicate that the cerebral absorption of medicines is diminished if they are metabolized and/or expelled by transporters at the blood-brain barrier [26]. The results align with previous studies indicating that oral medication administration yields lower antidepressant efficacy compared to intranasal delivery to the brain [27].

Fig. 6: Evaluation of the antidepressant activity of LEV-NLC in chronic depressed rats. Data was expressed in mean±SD, (n=3)

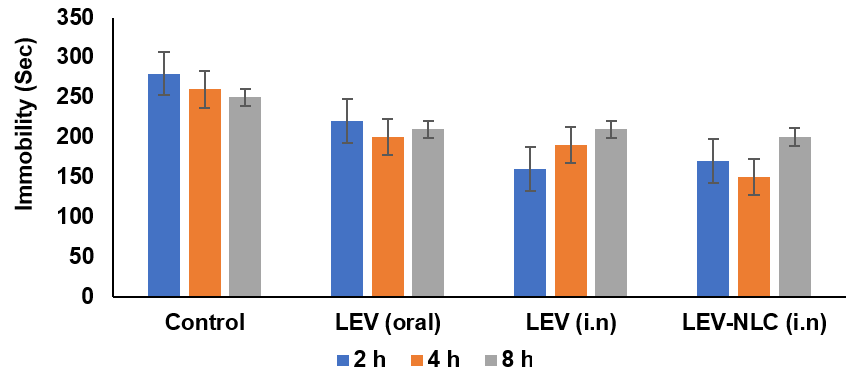

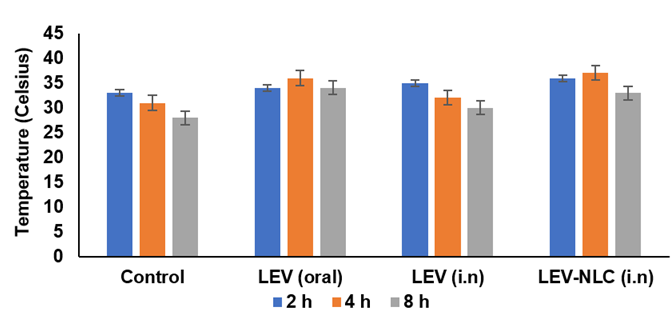

The RRT is among the most prevalent models for drug-induced depression [31]. Reserpine is known to irreversibly inhibit Vesicular monoamine transporters (VMAT) and alter monoaminergic transmission in the brain. The obstruction of VMAT transporters inhibits the vesicular absorption of monoamines and their subsequent release into the synaptic cleft for postsynaptic neuronal activation [32]. The reduction of monoamines at nerve terminals results in behavioural manifestations such as hypothermia, ptosis, immobility, and diarrhea [31, 32]. All three formulations diminished reserpine-induced immobility in rats; however, only the LEV solution (i. n., 2 h) and LEV-NLCs (i. n., 2 h, 4 h) achieved a statistically significant reduction (P<0.05) (fig. 7). All three formulations similarly mitigated reserpine-induced hypothermia in rats; however, these differences were statistically insignificant when compared to the control group (fig. 8).

Fig. 7: Effect of LEV-NLC on the reserpine-induced immobility and ptosis. Data was expressed in mean±SD, (n=3)

Fig. 8: Effect of LEV-NLC on the reserpine-induced hypothermia and diarrhoea in rats. Data was expressed in mean±SD, (n=3)

Nevertheless, the ptosis and diarrhoea induced by reserpine were only faintly antagonized by LEV-NLCs (fig. 7 and 8). Consequently, these formulations demonstrated superior and more distinct antidepressant efficacy in chronic forced swim test models compared to the drug-induced depression model. Consequently, monoamine concentrations were assessed in the brains of rats subjected to the forced swim test (FST). There was a marginal reversal in temperature observed with LEV-NLC compared to the control, due to poor levels of monoamine concentration in synaptic terminals, which is much required for thermoregulation.

Biochemical studies

A multitude of theories, hypotheses, and mechanisms have been offered about depression. The predominant explanation about the pathophysiology of depression is the monoamine hypothesis, which posits that a functional shortage of monoamines, including serotonin, noradrenaline, and dopamine in the central nervous system, is associated with depressive symptoms [4]. Most commonly utilized antidepressants elevate the concentration of neurotransmitters in the brain [33].

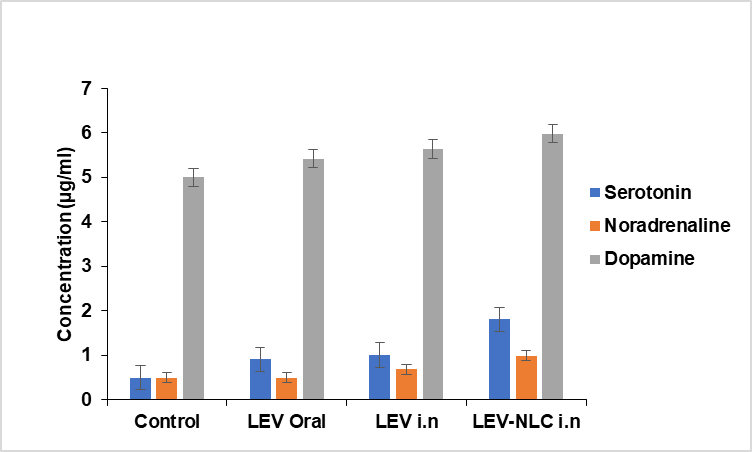

Consequently, we examined the alterations in brain monoamine levels and their association with the antidepressant efficacy in several groups of rats utilized in the Forced Swim Test (FST). Fig. 9 illustrates the concentrations of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine in the brain following the forced swim test (FST). Serotonin levels were significantly elevated in LEV-NLC group (p<0.01) compared to the control, with a mean difference of 12.3 ng/g (95% CI: 6.2–18.4 ng/g, d = 2.1). These findings indicated that intranasal delivery of LEV-NLCs significantly increased serotonin (P<0.01) and noradrenaline (P<0.05) levels compared to the depressed control, with noradrenaline levels being restored more successfully.

Fig. 9: Effect of LEV-NLC on neurotransmitter level in the brain of rats, data was expressed in mean±SD, (n=3)

The dopamine level was elevated in the LEV-NLCs-treated rats, although this rise was statistically insignificant when compared to the depressed control (p>0.05). This aligns with the known pharmacodynamic action of levomilnacipran as an SNRI, which predominantly inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, exerting minimal direct influence on dopaminergic pathways. Additionally, the reserpine-induced monoamine depletion model may necessitate specific dopaminergic interventions to achieve a meaningful restoration of dopamine levels. The findings align with earlier research indicating that monoamines, particularly serotonin and noradrenaline, are reduced under stressful conditions, as evidenced in depressed rats [34]. LEV-NLCs enabled the transport of LEV to the brain, while LEV inhibited the absorption of serotonin and noradrenaline, thereby augmenting their concentration in the nerve terminals.

LEV-NLCs significantly restored monoamine neurotransmitter levels in chronically depressed rats, resulting in improved swimming, climbing, and locomotor activity compared to control. LEV (i. n.) therapy cons increased noradrenaline levels but did not significantly elevate serotonin and dopamine levels. Conversely, LEV (oral) did not produce any significant alteration (p>0.05) in the levels of three neurotransmitters, which exhibited a strong association with the outcomes of pharmacodynamic tests. The data suggest that chronic depression in rats is primarily influenced by alterations in noradrenaline levels in the brain, while being less affected by variations in dopamine levels. The findings align with prior research indicating that behavioural depression induced by uncontrolled shock is more responsive to fluctuations in noradrenaline levels in the brain than to serotonin or dopamine levels [35]. The concentrations of LEV in the brain and systemic circulation were determined to corroborate these assertions.

Blood and brain pharmacokinetics

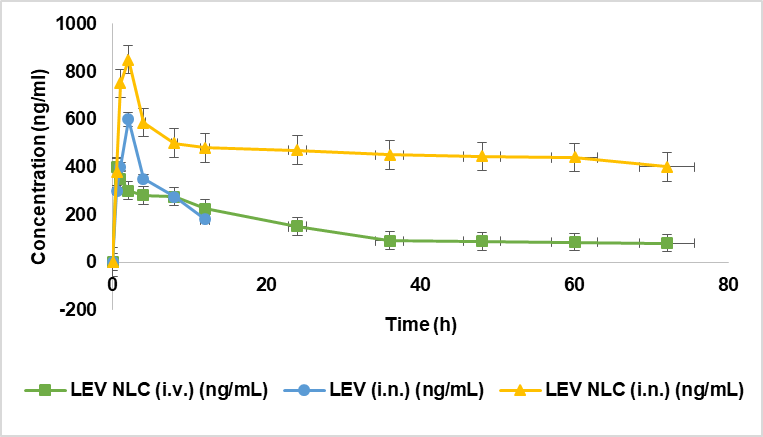

The concentrations of LEV in the brain and blood plasma were analyzed at various time points up to 72 h after the administration of LEV-NLCs (intranasally), LEV solution (intranasally), and LEV-NLCs (intravenously). The brain homogenate exhibited a greater LEV concentration following intranasal injection of LEV-NLCs (900±80 ng/ml) compared to intravenous treatment (400±40 ng/ml) (Fig. 10). Other pharmacokinetic characteristics, including half-life, AUC, and AUMC, were observed to be elevated in the brain for LEV-NLCs (i. n.) compared to LEV-NLCs (i. v.). The elimination rate of LEV-NLCs (i. n.) was substantially reduced (p<0.05) in the brain. At beginning time points, brain tissue concentration/time profiles appear analogous for all three formulations; nevertheless, they diverge dramatically at subsequent time points. Nevertheless, LEV-NLCs administered intravenously were capable of sustaining LEV in the brain for an extended duration, albeit at significantly lower concentrations compared to LEV-NLCs administered intranasally.

These findings demonstrate that NLC may deliver LEV to the brain via distinct nasal-to-brain transport pathways and sustain its effective therapeutic concentration for over 72 h in the brain. Consequently, intranasal transport from the nose to the brain constitutes a superior method for the non-invasive administration of LEV to the brain. Research indicates that a therapeutically delivered drug via the intranasal route accesses the brain through various extracellular and intracellular mechanisms, including olfactory and trigeminal nerve pathways [36, 37]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that mucoadhesive nanoparticles may deliver encapsulated medications to the brain via distinct nasal-to-brain transport pathways, sustaining effective therapeutic concentrations in the brain for extended periods. The mucoadhesive nanoparticulate technology of LEV-NLCs enhanced the retention duration of LEV in the nasal cavity to maintain its effective therapeutic concentration in the brain. Moreover, CN utilized in nose-to-brain formulations has been shown to augment paracellular transport across epithelial tight junctions through its specific interaction with the protein kinase C pathway or its electrostatic interaction with negatively charged sialic acid residues on mucosal epithelial cells [38]. In addition, Chitosan, a natural polysaccharide derived from chitin, has mucoadhesive properties that significantly improve drug delivery to the brain, particularly through intranasal administration. Chitosan adheres to the nasal mucosa due to its positive charge, which interacts with the negatively charged mucin, prolonging the residence time of the drug at the absorption site, enhancing uptake. Chitosan transiently opens tight junctions between epithelial cells, improving the paracellular transport of drugs that typically can't cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), also, by bypassing the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB), bypassing the BBB. Chitosan’s properties facilitate better penetration through the olfactory and trigeminal nerve pathways, improving the drug delivery to the brain. The LEV-NLCs (intranasally) enhanced the pharmacokinetic profile of LEV in the brain, restoring monoaminergic neurotransmitter levels and improving pharmacodynamic responsiveness. Most startling findings were achieved following the administration of LEV (i. n.). Despite exhibiting a more rapid absorption rate in the brain compared to LEV-NLCs, it possessed a significantly brief residence period in the brain, possibly attributable to the mucociliary removal of LEV from the nasal cavity.

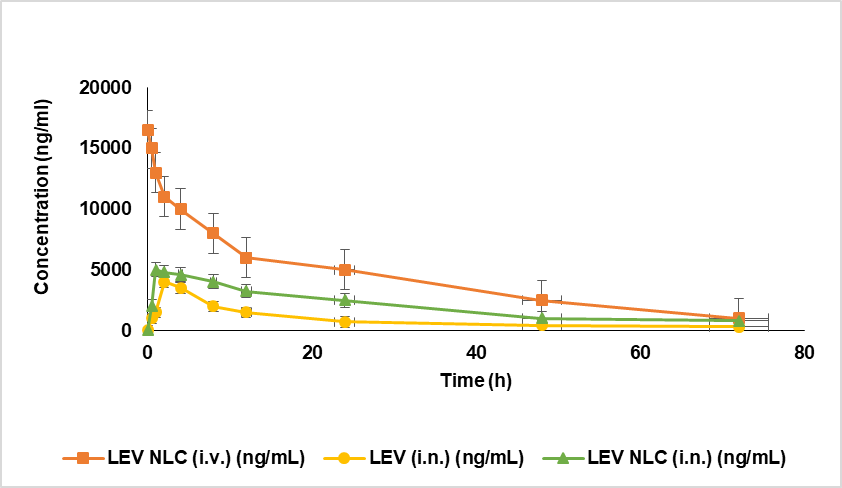

The swift absorption can be attributed to the low molecular weight of LEV (246.17 Da), which enhances its passage through the tight junctions of epithelial cells and its transport via trigeminal and olfactory nerve pathways to the brain.[39]. In systemic circulation, LEV-NLC nanoparticles achieved a lower peak plasma concentration (4800±200 ng/ml) compared to LEV-NLCs administered intravenously (16000±200 ng/ml) (Fig. 11). These findings align with previous research indicating that medicines can be absorbed into systemic circulation via the respiratory areas of the nasal cavity, albeit at significantly lower levels than through the intravenous route.

LEV (i. n.) was found in plasma beyond 24 h due to ongoing absorption from respiratory areas; nevertheless, its plasma concentration suggests that the majority of the dose was eliminated by mucociliary clearance. To evaluate the extent of brain-specific delivery of levomilnacipran, the brain-to-blood drug concentration ratio was calculated at multiple time points following administration. This ratio was obtained by dividing the drug concentration measured in brain homogenate by the corresponding concentration in plasma. Since plasma concentrations are expressed in ng/ml and brain tissue is a solid matrix, normalization was performed by converting brain concentrations to equivalent fluid-based units. This was achieved by applying a standard brain tissue density value of 1.04 g/ml, allowing for accurate and meaningful comparison between the two biological compartments. The resulting brain-to-blood ratios served as a quantitative indicator of drug targeting efficiency to the central nervous system. Notably, formulations administered via the intranasal route, particularly LEV-NLCs, demonstrated consistently higher brain-to-blood ratios, highlighting the enhanced potential of this delivery strategy for direct nose-to-brain transport and improved central therapeutic availability.

The systemic bioavailability of LEV-NLCs (i. n.) and LEV (i. n.) was determined to be 62% and 28%, respectively, based on their plasma AUC values. The DTE indicates the average distribution of LEV between the brain and blood over time, whereas DTP represents the percentage of LEV transported directly to the brain via nasal routes. The DTE and DTP for LEV-NLCs (i. n.) were determined to be 450 and 86, while for LEV (i. n.) they were 200 and 55, respectively. The elevated DTE and DTP values of LEV-NLCs indicate superior brain targeting efficiency compared to the other two formulations.

Although the study established the promising brain-targeting capability and antidepressant effectiveness of intranasally delivered LEV-NLCs, certain limitations must be acknowledged. Notably, no histopathological analysis of the nasal mucosa was performed to evaluate potential tissue irritation or damage resulting from chronic intranasal administration. This is particularly relevant considering the use of chitosan as a mucoadhesive polymer and the repeated dosing regimen. Furthermore, the study did not include a comprehensive assessment of drug biodistribution across non-target organs. As a result, it remains uncertain whether the observed increase in brain concentration might be accompanied by off-target accumulation in peripheral tissues. Future investigations incorporating nasal tissue toxicity studies and systemic organ-level pharmacokinetics are warranted to ensure the safety and specificity of this delivery strategy.

Fig. 10: Effect of LEV-NLC on brain concentration, data was expressed in mean ±SD, (n=3)

Fig. 11: Effect of LEV NLC on plasma concentration, data was expressed in mean±SD, (n=3)

CONCLUSION

This study optimised a nanostructured drug delivery device for the cerebral administration of LEV. The tailored LEV-NLCs markedly enhanced the cerebral uptake of LEV. Pharmacodynamic analysis and monoamine levels in the brain demonstrate that LEV-NLCs significantly alleviated depressive symptoms in rats. The results imply that nose-to-brain transfer is a feasible non-invasive method for treating depression and other neurological disorders. Nonetheless, these formulations require thorough preclinical investigations in advanced animal models to forecast their effectiveness in people. A considerable effort is needed for the advancement of delivery systems capable of targeting the olfactory region of the nose exclusively.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the article as follows: Study conception and design: Parthiban Ramalingam, Mothilal. M; Data collection: Parthiban Ramalingam; Analysis and interpretation of results: Parthiban Ramalingam, Mothilal. M.; Draft manuscript: Parthiban Ramalingam, Mothilal. M. The authors reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Kircanski K, Lieberman MD, Craske MG. Feelings into words: contributions of language to exposure therapy. Psychol Sci. 2012 Oct;23(10):1086-91. doi: 10.1177/0956797612443830, PMID 22902568.

Ravikumar L, Velmurugan R, Vidiyala N, Sunkishala P, Teriveedhi VK. Nanotechnology-driven therapeutics for liver cancer: clinical applications and pharmaceutical insights. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2025 Feb 7;18(2):8-26. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2025v18i2.53429.

Janadri S, Dadmi S. Mudagal Mp, Sharma Ur, Vada S, Haribabu T. Alzheimer’s disease: comprehensive insights into risk factors, biomarkers and advanced treatment approaches. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2025 Jan 15;17(1):1-10.

Lenox RH, Frazer A, Lenox RH, Frazer A. Mechanism of action of antidepressants and mood stabilizers. In: Davis KL. Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C, editors, Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation Of Progress. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. p. 1139-63.

Marcus M, Yasamy MT, Van Ommeren MV, Chisholm D, Saxena S. Depression: A Global Public Health Concern; 2012. doi: 10.1037/e517532013-004.

Kessler RC, Aguilar Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18(1):23-33. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00001421, PMID 19378696.

Nutt DJ. Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69 Suppl E1:4-7. PMID 18494537.

Kilts CD. Potential new drug delivery systems for antidepressants: an overview. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64 Suppl 18:31-3. PMID 14700453.

Kumar M, Misra A, Babbar AK, Mishra AK, Mishra P, Pathak K. Intranasal nanoemulsion-based brain targeting drug delivery system of risperidone. Int J Pharm. 2008 Jun;358(1-2):285-91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.03.029, PMID 18455333.

Al Ghananeem AM, Saeed H, Florence R, Yokel RA, Malkawi AH. Intranasal drug delivery of didanosine-loaded chitosan nanoparticles for brain targeting; an attractive route against infections caused by aids viruses. J Drug Target. 2010 Jun;18(5):381-8. doi: 10.3109/10611860903483396, PMID 20001275.

Md S, Khan RA, Mustafa G, Chuttani K, Baboota S, Sahni JK. Bromocriptine-loaded chitosan nanoparticles intended for direct nose to brain delivery: pharmacodynamic pharmacokinetic and scintigraphy study in mice model. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013 Feb;48(3):393-405. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.007, PMID 23266466.

Ramalingam P, Dutta G, Mohan M, Sugumaran A. Solid lipid nanoparticle a complete tool for brain-targeted drug delivery. Curr Issues Pharm Med Sci. 2025 Mar 31;38(1):11-21. doi: 10.12923/cipms-2025-0002.

Parthiban R, MM, Bhupathyraaj M, Sridhar SB, Shareef J, Thomas S. An overview of various approaches for brain-targeted drug delivery system. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis. 2024 Jan;14(1):1-8. doi: 10.4103/ijnpnd.ijnpnd_72_23.

Lee D, Minko T. Nanotherapeutics for nose-to-brain drug delivery: an approach to bypass the blood-brain barrier. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Nov 30;13(12):2049. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13122049, PMID 34959331.

Mann JJ. The medical management of depression. N Engl J Med. 2005 Oct 27;353(17):1819-34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050730, PMID 16251538.

Perry R, Cassagnol M. Desvenlafaxine: a new serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor for the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder. Clin Ther. 2009 Jan;31(1):1374-404. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.07.012, PMID 19698900.

Pawar D, Goyal AK, Mangal S, Mishra N, Vaidya B, Tiwari S. Evaluation of mucoadhesive PLGA microparticles for nasal immunization. AAPS J. 2010 Jun;12(2):130-7. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9169-1, PMID 20077052.

Huang Q, Chen Y, Zhang W, Xia X, Li H, Qin M. Nanotechnology for enhanced nose-to-brain drug delivery in treating neurological diseases. J Control Release. 2024 Feb;366:519-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.12.054, PMID 38182059.

Velmurugan R, Selvamuthukumar S. Development and optimization of ifosfamide nanostructured lipid carriers for oral delivery using response surface methodology. Appl Nanosci. 2016 Feb;6(2):159-73. doi: 10.1007/s13204-015-0434-6.

Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Jalfre M. Behavioural despair in rats and mice: strain differences and the effects of imipramine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978 Oct;51(3):291-4. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90414-4, PMID 568552.

Kitada Y, Miyauchi T, Satoh A, Satoh S. Effects of antidepressants in the rat forced swimming test. Eur J Pharmacol. 1981 Jun;72(2-3):145-52. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90269-7, PMID 7195816.

Paget GE, Barnes JM. Toxicity tests. In: Evaluation of drug activities. Elsevier; 1964. p. 135-66. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4832-2845-7.50012-8.

Costa E, Garattini S, Valzelli L. Interactions between reserpine chlorpromazine and imipramine. Experientia. 1960 Oct;16(10):461-3. doi: 10.1007/BF02171155, PMID 13695781.

Schlumpf M, Lichtensteiger W, Langemann H, Waser PG, Hefti F. A fluorometric micromethod for the simultaneous determination of serotonin noradrenaline and dopamine in milligram amounts of brain tissue. Biochem Pharmacol. 1974 Sep;23(17):2437-46. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90235-4, PMID 4429570.

Md S, Khan RA, Mustafa G, Chuttani K, Baboota S, Sahni JK. Bromocriptine-loaded chitosan nanoparticles intended for direct nose-to-brain delivery: pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic and scintigraphy study in mice model. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013 Feb;48(3):393-405. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.007, PMID 23266466.

Raut BB, Kolte BL, Deo AA, Bagool MA, Shinde DB. A rapid and sensitive HPLC method for the determination of venlafaxine and O‐Desmethylvenlafaxine in human plasma with UV detection. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 2003 Apr;26(8):1297-313. doi: 10.1081/JLC-120020112.

Lucki I. The forced swimming test as a model for core and component behavioral effects of antidepressant drugs. Behav Pharmacol. 1997 Nov;8(6-7):523-32. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199711000-00010, PMID 9832966.

Berney P. Dose response relationship of recent antidepressants in the short-term treatment of depression. Dial Clin Neurosci. 2005 Sep 30;7(3):249-62. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2005.7.3/pberney, PMID 16156383.

Reneric JP, Bouvard M, Stinus L. In the rat forced swimming test chronic but not subacute administration of dual 5-HT/NA antidepressant treatments may produce greater effects than selective drugs. Behav Brain Res. 2002 Nov;136(2):521-32. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00203-6, PMID 12429415.

Reneric JP, Lucki I. Antidepressant behavioral effects by dual inhibition of monoamine reuptake in the rat forced swimming test. Psychopharmacol (Berl). 1998 Mar 11;136(2):190-7. doi: 10.1007/s002130050555, PMID 9551776.

Hermann DM, Bassetti CL. Implications of ATP-binding cassette transporters for brain pharmacotherapies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007 Mar;28(3):128-34. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.01.007, PMID 17275929.

Alam MI, Baboota S, Ahuja A, Ali M, Ali J, Sahni JK. Intranasal administration of nanostructured lipid carriers containing CNS acting drug: pharmacodynamic studies and estimation in blood and brain. J Psychiatr Res. 2012 Sep;46(9):1133-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.05.014, PMID 22749490.

Richelson E. Antidepressants and brain neurochemistry. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990 Sep;65(9):1227-36. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62747-5, PMID 2169557.

Arnsten AF. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009 Jun;10(6):410-22. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648, PMID 19455173.

Weiss JM, Goodman PA, Losito BG, Corrigan S, Charry JM, Bailey WH. Behavioral depression produced by an uncontrollable stressor: relationship to norepinephrine dopamine and serotonin levels in various regions of rat brain. Brain Res Rev. 1981 Oct;3(2):167-205. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(81)90005-9.

Illum L. Transport of drugs from the nasal cavity to the central nervous system. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000 Jul;11(1):1-18. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(00)00087-7, PMID 10913748.

Thorne RG, Frey WH. Delivery of neurotrophic factors to the central nervous system: pharmacokinetic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(12):907-46. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140120-00003, PMID 11735609.

Artursson P, Lindmark T, Davis SS, Illum L. Effect of chitosan on the permeability of monolayers of intestinal epithelial cells (Caco-2). Pharm Res. 1994;11(9):1358-61. doi: 10.1023/a:1018967116988, PMID 7816770.

Pund S, Rasve G, Borade G. Ex vivo permeation characteristics of venlafaxine through sheep nasal mucosa. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013 Jan;48(1-2):195-201. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.10.029, PMID 23159662.