Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 471-477Original Article

ENHANCED COMBINED EFFECTS OF GARCINIA COWA BARK EXTRACT AND DOXORUBICIN ON CELL CYCLE REGULATION AND P53 EXPRESSION IN T47D BREAST CANCER CELLS

IFORA IFORA1,3, DACHRIYANUS HAMIDI2, MERI SUSANTI2, FATMA S. WAHYUNI2*

1Faculty of Pharmacy, Andalas University, Padang, Indonesia 25163, 2Faculty of Pharmacy, Andalas University, Kampus Limau Manis, 25163 Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia, 3Department of Pharmacology, School of Pharmaceutical Science Padang (STIFARM Padang), West Sumatera, Indonesia, 25147.*Corresponding author: Fatma S. Wahyuni; *Email: fatmasriwahyuni@phar.unand.ac.id

Received: 09 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 04 Sep 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate the effects of ethanol extract of Garcinia cowa bark (EEGCB) and doxorubicin (Dox), both individually and in combination, on cell cycle regulation and protein expression in T47D breast cancer cells.

Methods: T47D cells were treated with EEGCB (130 µg/ml), Dox (0.026 µg/ml), and a combination of both, and flow cytometry was used to analyze cell cycle distribution and the expression of p53, Cyclin D, and Cyclin E.

Results: EEGCB induced apoptosis in T47D cells, increasing the subG1 population (p<0.0001), while Dox caused G2/M arrest (p<0.0001). Combined treatment enhanced both effects. EEGCB upregulated cyclin D/E, yet the combination reduced their expression, suggesting altered cell cycle regulation. Critically, EEGCB alone or with Dox significantly elevated p53 levels (44.6±0.592% and 37.6±1.662%, respectively; p<0.0001), implicating p53 in its anticancer activity. These results demonstrate EEGCB’s dual pro-apoptotic and cell cycle-disrupting effects, with potential chemosensitizing properties.

Conclusion: These findings highlight EEGCB as a potential adjunct to conventional chemotherapy, providing a scientific basis for further exploration in breast cancer therapy.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Cell cycle checkpoints, Flow cytometry, Garcinia cowa, Antineoplastic agents

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.54533 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent malignancies worldwide, accounting for a significant proportion of cancer-related morbidity and mortality [1]. Despite advances in conventional therapies such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted treatments, challenges such as drug resistance, severe side effects, and high recurrence rates persist, underscoring the need for novel therapeutic strategies [2, 3]. Recently, natural products have emerged as promising sources of anticancer agents due to their diverse bioactive compounds, low toxicity, and potential to target multiple molecular pathways [4, 5]. Among these, Garcinia cowa, a tropical plant widely used in traditional medicine, has garnered attention for its pharmacological properties, including anti-inflammatory [6], antioxidant [7, 8], and anticancer activities [7, 9, 10].

The cell cycle is a tightly regulated process, and its dysregulation is a hallmark of cancer. Key regulators such as Cyclin D and Cyclin E play critical roles in the transition from the G1 to S phase, making them attractive targets for anticancer therapies [11]. The tumor suppressor p53 serves as a master regulator of cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and DNA repair, with its dysfunction observed in>50% of human cancers. Restoring wild-type p53 activity represents a compelling therapeutic strategy, as it can simultaneously modulate multiple oncogenic pathways while maintaining genomic stability [12–14]. Doxorubicin (Dox), a widely used chemotherapeutic agent, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [15, 16], but its clinical usefulness is limited by dose-dependent cardiotoxicity [17] and the development of drug resistance [18]. Combining natural products like Garcinia cowa with conventional chemotherapy has emerged as a promising strategy to enhance efficacy while reducing adverse effects.

However, the mechanisms underlying the anticancer effects of Garcinia cowa, particularly in combination with Dox, remain poorly understood. Limited research has explored the combination effect of doxorubicin and Garcinia cowa on cell cycle regulation and protein expression in breast cancer cells. Addressing this gap is crucial for developing novel therapeutic strategies that leverage the benefits of natural products and conventional chemotherapy. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of ethanol extract of Garcinia cowa bark (EEGCB) and doxorubicin (Dox), both individually and in combination, on cell cycle regulation and the expression of p53, Cyclin D, and Cyclin E in T47D breast cancer cells. By elucidating the molecular mechanisms of EEGCB and its potential combination with Dox, this research seeks to contribute to the development of novel combination therapies for breast cancer treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and extract preparation

The stem bark of Garcinia cowa was collected from Kudu Gantiang, Pariaman City, West Sumatra, Indonesia (geographical coordinates: 0°30'42.1"S 100°09'48.7" E). A voucher specimen (No.556-ID/ANDA/XII/2022) was deposited at the Herbarium of Andalas University, where its botanical identity was confirmed by a taxonomist (Dr. Nurainas, Andalas University's Herbarium). The plant material was washed, dried, and ground into a fine powder. Ethanol extraction was performed using the maceration method: 400 g of powdered bark was soaked in 4000 ml of 70% ethanol for 72 h at room temperature. The extract was filtered and concentrated using a rotary evaporator (40–50 °C) under reduced pressure to obtain the crude extract, which was stored at 4 °C in an airtight container until analysis [19].

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis

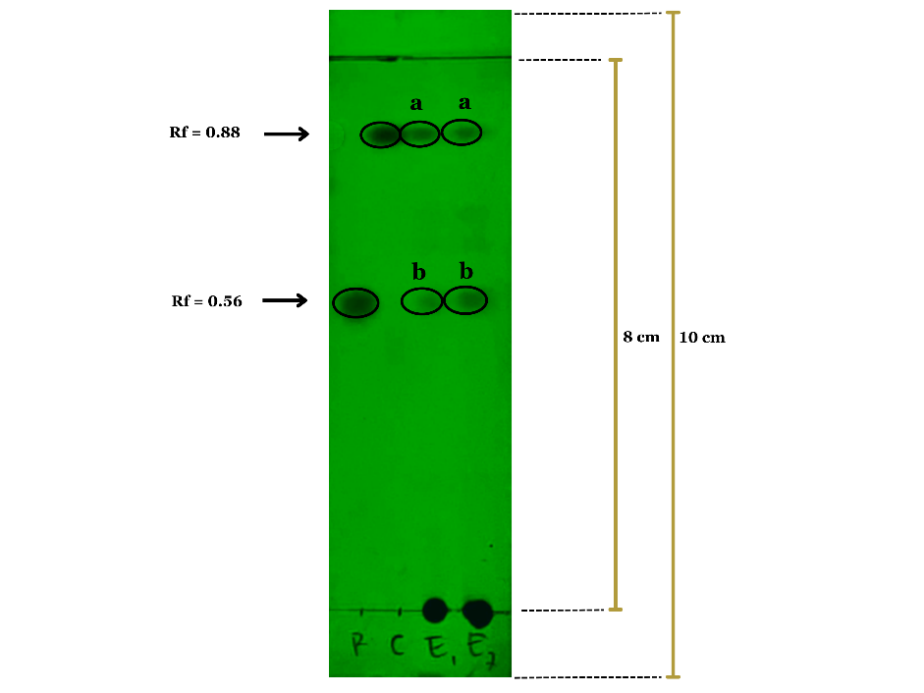

TLC analysis was performed to separate and identify the chemical constituents of the extract. The extract was dissolved in a suitable solvent and spotted onto a pre-coated silica gel TLC plate (60 F254, Merck). The plate was developed in a solvent system optimized for the target compounds (Chloroform: methanol: ethyl acetate: formic acid, 86: 6: 3: 5 v/v/v/v). After development, the plate was dried and visualized under ultraviolet (UV) light at 254 nm. The retention factor (Rf) values of the separated spots were calculated and compared with reference standards (Rubraxathon and cowanin) for identification [20].

Cell culture

T47D breast cancer cells were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium) (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, USA). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂. For experiments, cells were seeded at a density of 5×10⁵ cells/ml and allowed to adhere for 24 h before treatment [21].

Treatment with Garcinia cowa extract and doxorubicin

T47D cells were treated with EEGCB (130 µg/ml), Dox (0.026 µg/ml), or a combination of EEGCB (130 µg/ml)+Dox (0.026 µg/ml) for 48 h. These concentrations were selected based on our prior cytotoxicity studies demonstrating a combination index (CI) of 0.8 (indicating synergy) at this ratio using the Chou-Talalay method [9].

Cell cycle analysis

After treatment, cells were harvested using trypsin-EDTA (Ethylenediamine tetra acetic Acid) (Gibco, USA), washed twice with cold Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), and fixed with 70% ethanol. Fixed cells were washed with PBS (Gibco, USA) and stained with Propidium Iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich) solution (50 µg/ml PI, 0.1% Triton X-100(Merck), and 20 µg/ml RNase A (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in PBS) for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. Cells were analyzed using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer equipped with a 488 nm laser. Fluorescence intensity was measured for at least 10,000 events per sample, and data were analyzed using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) to determine the distribution of cells in the SubG1, G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle [22].

Cyclin D/E expression analysis

T47D cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, treated, and harvested as described above. After harvesting, cells were fixed with 70% ethanol. Fixed cells were washed with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. Non-specific binding was blocked using 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (Merck) in PBS for 30 min. Cells were incubated with a primary anti-Cyclin D and anti-Cyclin E antibody overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with a fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Cells were washed twice with PBS, re suspended in 500 µl** PBS, and analyzed using a BD FACS Calibur flow cytometer. Fluorescence intensity was measured for at least 10,000 events per sample, and data were analyzed using Cell Quest software to quantify total Cyclin D/E expression levels [23].

P53 expression analysis

For p53 detection, T47D cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, treated, and harvested as described above. After harvesting, cells were fixed with 70% ethanol. Fixed cells were washed with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were blocked with 1% BSA/PBS for 30 min and incubated with an anti-p53 primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 500 µl** PBS, and analyzed using a BD FACS Calibur flow cytometer. Fluorescence intensity was measured for at least 10,000 events, and data were analyzed using Cell Quest software [24].

Analysis

Flow cytometry data was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test to compare differences among treatment groups. Data are presented as mean±SD (n ≥ 3). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Analyses were performed using Graph Pad Prism (version 8.4.0), and flow cytometry data were processed with Cell Quest software.

RESULTS

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis of EEGCB, developed on Silica gel 60 F254 plates using chloroform: methanol: ethyl acetate: formic acid (86:6:3:5 v/v/v/v) as mobile phase, revealed two distinct bands with Rf values identical to reference standards when visualized under UV 254 nm. The extract fractions E1a/E2a (Rf=0.88) and E1b/E2b (Rf=0.56) (as illustrated in fig. 1) showed perfect co-migration with cowanin and rubraxanthone standards, respectively, demonstrating excellent separation efficiency of this solvent system for xanthone compounds. The acidic mobile phase (containing 5% formic acid) particularly enhanced the resolution of these polar constituents, as evidenced by the sharp, well-defined spots without tailing. The selective visualization under UV 254 nm further confirmed the presence of conjugated systems characteristic of xanthones. This optimized TLC protocol successfully identified two major xanthones in G. cowa, while the absence of additional bands suggests either complete separation of these dominant compounds or potential limitations in detecting minor metabolites under these specific conditions. These results provide a reliable foundation for subsequent quantitative analysis and bioactivity studies of these isolated xanthones.

Fig. 1: Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis of EEGCB and reference standards (rubraxanthone and cowanin) under UV 254 nm detection

Table 1: TLC analysis of Garnicinacowa bark extract

| Sample | Rf Value | Putative compound |

| Garcinia cowa extract (E1 a) | 0.88 | Cowanin |

| Garcinia cowa extract (E1 b) | 0.56 | Rubraxanthone |

| Garcinia cowa extract (E2 a) | 0.88 | Cowanin |

| Garcinia cowa extract (E2 b) | 0.56 | Rubraxanthone |

| Rubraxanthone (Standard) (R) | 0.56 | Rubraxanthone |

| Cowanin (Standard) (C) | 0.88 | Cowanin |

Cell cycle arrest activity of Garcinia cowa bark ethanol extract in T47D breast cancer cells

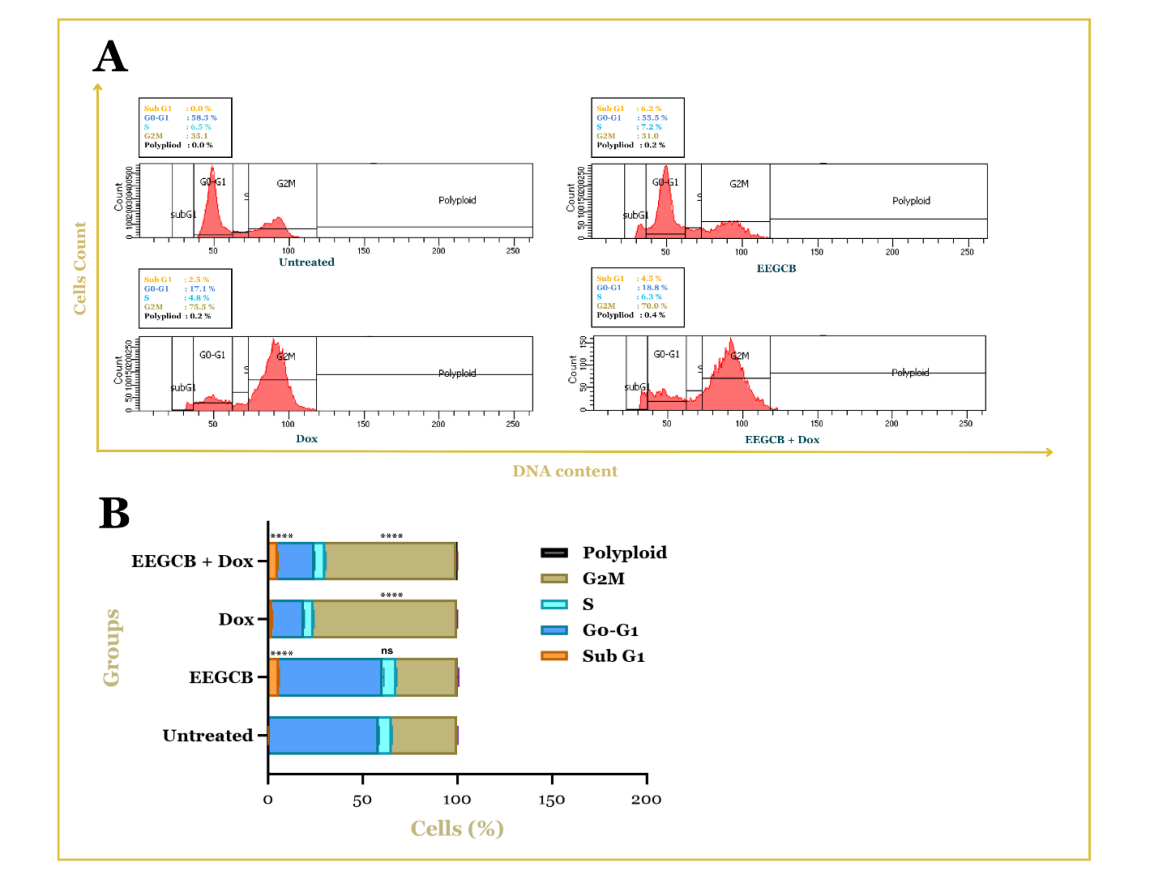

Flow cytometric analysis revealed distinct alterations in the cell cycle distribution of T47D breast cancer cells following treatment with EEGCB, Dox, or their combination. Untreated cells exhibited a typical cell cycle profile with a predominant population in the G0/G1 phase. Treatment with EEGCB (130 µg/ml) resulted in a noticeable increase in the subG1 population (p<0.0001), indicative of apoptotic cell death, while minimally affecting other cell cycle phases. Doxorubicin (0.026 µg/ml) treatment led to a significant accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase (p<0.0001). Notably, the combination of EEGCB and Dox (130 µg/ml+0.026 µg/ml) showed significantly stronger effects than either treatment alone, characterized by a substantial increase in both the subG1 and G2/M populations (p<0.0001). This suggests an enhanced cytotoxic effect, potentially through the combined induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. The quantitative analysis of cell cycle distribution is presented in fig. 2, illustrating the percentage of cells in each phase across the different treatment groups.

Fig. 2: Cell cycle distribution in T47D breast cancer cells analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative histograms showing the distribution of cells in different phases of the cell cycle (SubG1, G0/G1, S, G2/M, and polyploid) after treatment with vehicle (Untreated), EEGCB, Dox, or the combination of EEGCB+Dox. (B) Quantification of cell cycle phase distribution, presented as the percentage of cells in each phase. Results are presented as mean±SD (n = 3). Ns: non-significant, **** p<0.0001 compared to the untreated group

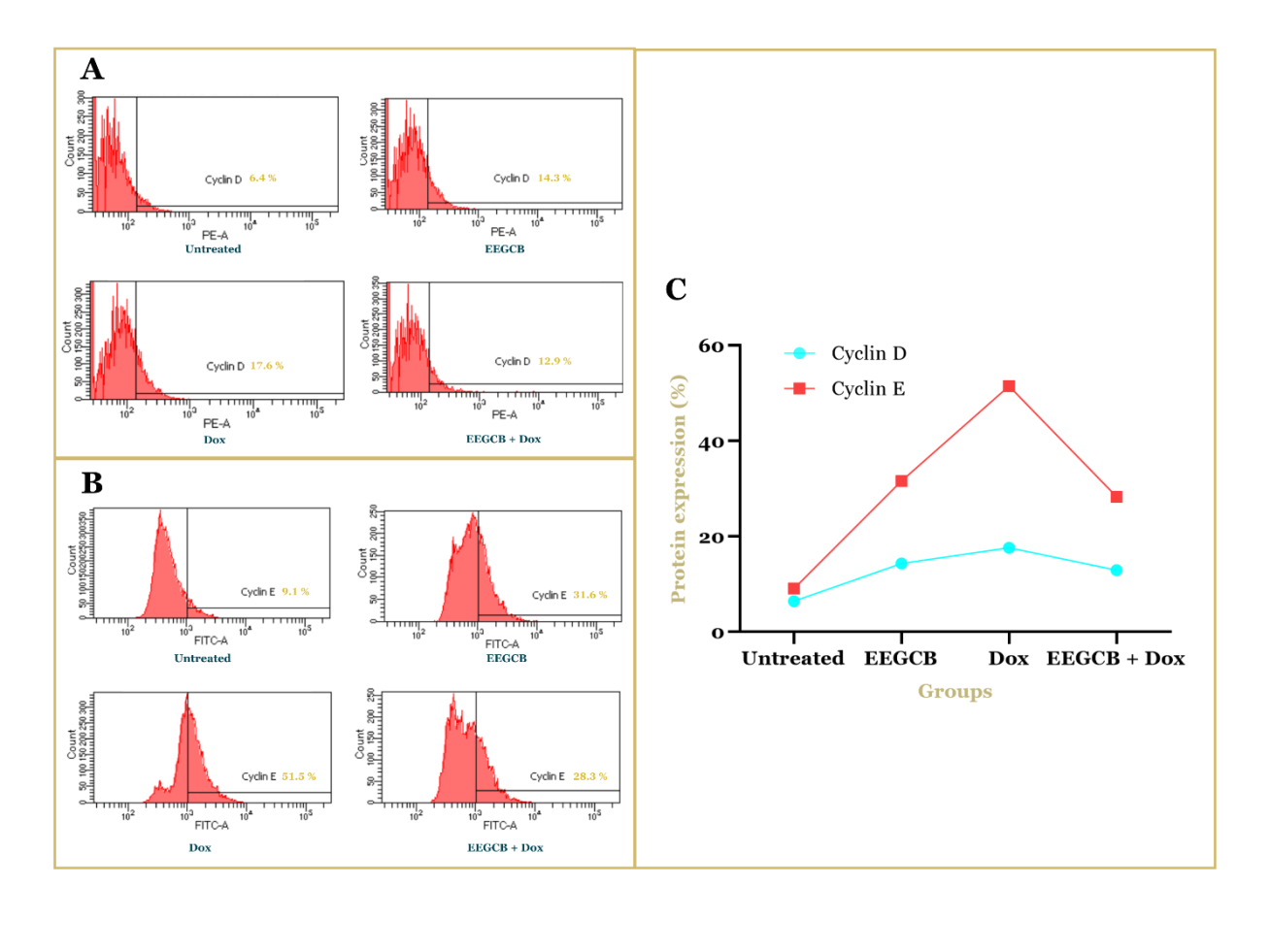

Ethanol extract of Garcinia cowa bark modulates cyclin D/E expression in T47D breast cancer cells.

Flow cytometry analysis showed significant changes in the expression of cyclin D and E proteins in T47D breast cancer cells treated with EEGCB, Dox, or a combination of both. Untreated cells (control) showed basal expression of cyclin D and E. Treatment with EEGCB (130 µg/ml) caused an increase in cyclin D and E expression compared to the control. Doxorubicin (0.026 µg/ml) increased cyclin E expression, while cyclin D expression was also increased compared to the control. Interestingly, the combination of EEGCB and Dox (130 µg/ml+0.026 µg/ml) showed a complex effect. The expression of cyclin D and cyclin E decreased compared to administration alone, in line with the effect of EEGCB, as illustrated in fig. 3. These results indicate a complex interaction between EEGCB and Dox in modulating the expression of cyclins D and E in T47D cells.

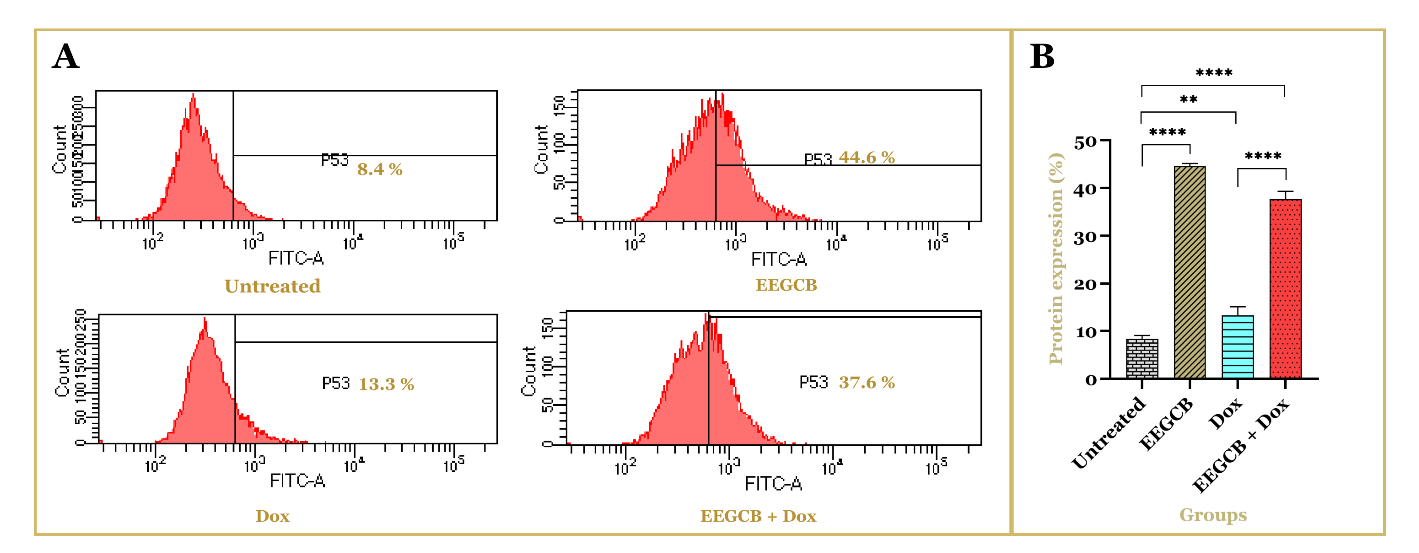

Effect of Garcinia cowa bark ethanolic extract on p53 protein expression in T47D breast cancer cells

The findings of this study indicate that treatment with EEGCB alone or in combination with Dox significantly increased p53 protein expression in T47D breast cancer cells. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the untreated control group exhibited the lowest percentage of p53-positive cells (8.4±0.700%), while treatment with EEGCB (130 µg/ml) alone resulted in a substantial increase (44.6±0.592%). The combination of EEGCB (130 µg/ml) and Dox (0.026 µg/ml) also showed a notable elevation (37.6±1.662%), whereas Dox (0.026 µg/ml) alone induced only a moderate rise (13.3±1.808%), as illustrated in fig. 4. Statistical analysis confirmed that the upregulation of p53 protein expression in the EEGCB and combination groups was significantly higher than in the untreated and Dox-treated groups (****p<0.0001). These results suggest that EEGCB is pivotal in enhancing p53 expression, potentially contributing to its anticancer properties.

Fig. 3: Flow cytometric analysis of Cyclin D and Cyclin E protein expression in T47D breast cancer cells. (A) Representative histograms showing Cyclin D expression (PE-A channel). (B) Representative histograms showing Cyclin E expression (FITC-A channel). (C) Quantification of Cyclin D and Cyclin E protein expression, presented as the percentage of positive cells. Cells were treated with vehicle (Untreated), EEGCB (130 µg/ml), Dox (0.026 µg/ml), or the combination of EEGCB+Dox (130 µg/ml+0.026 µg/ml) for 48h

Fig. 4: Effect of EEGCB and Dox on p53 protein expression in T47D breast cancer cells. Flow cytometry analysis was performed to assess p53 protein expression in untreated cells, EEGCB-treated cells, Dox-treated cells, and cells treated with the combination of EEGCB and Dox. (A) The representative histograms illustrate the percentage of p53-positive cells in each treatment group. (B) The bar graph presents the quantification of p53 protein expression (%), showing a significant increase in the EEGCB and combination groups compared to untreated and Dox-treated cells (**p<0.01, ****p<0.0001). Data are presented as mean±SD (n = 3)

DISCUSSION

The TLC analysis of EEGCB revealed distinct bands corresponding to Rf values of 4.5 and 7, matching the reference standards rubraxanthone (Rf=0.56) and cowanin (Rf=0.88), respectively. These results corroborate previous findings that identified xanthone compounds in related Garcinia cowa [20, 25]. The excellent separation achieved using the chloroform: methanol: ethyl acetate: formic acid (86:6:3:5 v/v/v/v) solvent system demonstrates its effectiveness for xanthone analysis, consistent with the methodology reported by previous studies [20]. The presence of these characteristic xanthones supports the plant's traditional medicinal uses, as these compounds are known for their antioxidant [26, 27] and anti-inflammatory properties [28, 29]. However, the absence of additional bands suggests potential limitations in detecting minor metabolites under these conditions. These findings validate the presence of bioactive xanthones in G. cowa and highlight the need for complementary analytical techniques, such as LC-MS, to fully characterize its phytochemical profile.

The flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle and Cyclin D, E, and p53 expression was performed using optimized concentrations derived from dose-response relationships (EEGCB: IC50 = 130 μg/ml; doxorubicin: IC50 = 0.026 μg/ml). The combination ratio (130 μg/ml EEGCB+0.026 μg/ml Dox) was specifically selected based on our prior demonstration of synergistic interaction (combination index [CI] = 0.8 via Chou-Talalay analysis) [9]. The observed increase in the subG1 population in T47D cells treated with EEGCB suggests a potent induction of apoptosis, a critical mechanism in cancer cell elimination. This finding aligns with previous studies indicating that bioactive compounds within Garcinia cowa possess the capacity to trigger mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in various cancer cell lines [30–32]. Dox, a well-established chemotherapeutic agent, elicited a distinct cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase, consistent with its known mechanism of action involving topoisomerase II inhibition and subsequent DNA damage [33, 34]. The concomitant increase in the subG1 population following Dox treatment further underscores its pro-apoptotic activity. Notably, the enhanced combinatorial effect observed with the EEGCB and Dox combination, as evidenced by the substantial elevation of cells in both the subG1 and G2/M phases, highlights the potential for EEGCB to enhance Dox-mediated cytotoxicity. These findings are further supported by previous studies demonstrating that both curcumin-doxorubicin and resveratrol-doxorubicin combinations can induce cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells [35, 36]. Collectively, these findings suggest that EEGCB holds promise as a standalone anticancer agent or as a valuable adjunct to conventional chemotherapy.

The flow cytometric analysis of cyclin D and E expression in T47D breast cancer cells revealed intriguing patterns following treatment with EEGCB, Dox, and their combination. While both EEGCB and Dox monotherapies increased cyclin D and E expression compared to untreated cells, the combination treatment paradoxically reduced their expression levels below those observed with single-agent treatments. This unexpected finding suggests a complex regulatory interaction between these compounds in cell cycle control. The observed upregulation of cyclins D and E by EEGCB alone (130 µg/ml) may reflect a compensatory cellular response to phytochemical-induced stress, as certain plant-derived compounds have been shown to transiently activate cell cycle proteins before inducing growth arrest [37, 38]. Similarly, Dox-induced cyclin E elevation (0.026 µg/ml) aligns with its known ability to disrupt normal cell cycle progression through DNA damage response pathways [39]. The paradoxical downregulation of Cyclin D/E by the EEGCB-Dox combination, despite the upregulation by individual treatments, can be explained by several mechanisms as follows: individual treatments can partially inhibit pathways such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR (upstream of Cyclin D) or MAPK (Cyclin E), but the combination can completely suppress these signals [40, 41]. The combination treatment's suppressive effect on cyclin expression provides compelling evidence of molecular interactions between EEGCB and Dox. This phenomenon may result from EEGCB’s potential to interfere with Dox-induced compensatory mechanisms or to enhance Dox's ability to disrupt cyclin-dependent kinase complexes [42, 43]. The differential modulation of cyclin D (G1/S regulator) and cyclin E (S phase promoter) suggests that the combination may target multiple cell cycle checkpoints simultaneously, potentially explaining its enhanced cytotoxic effects observed in previous cell cycle analyses. These findings are consistent with previous reports on natural product combinations, where both arctigenin-doxorubicin and resveratrol-doxorubicin were shown to induce cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells through suppression of the Cyclin D1/CDK4/RB pathway [44]. These findings highlight the importance of investigating natural product-chemotherapy interactions at the molecular level to better understand their therapeutic potential and optimize combination strategies for breast cancer treatment.

This study demonstrated that EEGCB (130 µg/ml) significantly upregulated p53 protein expression in T47D breast cancer cells, both as monotherapy and in combination with doxorubicin (Dox, 0.026 µg/ml). Flow cytometry analysis showed a substantial increase in p53-positive cells in the EEGCB-treated group (44.6±0.592%), surpassing the Dox-treated group (13.3±1.8-8%). The combination of EEGCB and Dox also enhanced p53 expression (37.6±1.662%), demonstrating a combined effect exceeding individual treatments. Previous studies have highlighted the anticancer properties of Garcinia-derived xanthones, which are known to activate tumor suppressor pathways, including p53-mediated apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [45–47]. Our findings are consistent with previous findings that reported that xanthones from Garcinia cowa induce apoptosis in human cancer cell lines [48]. Although the EEGCB+Dox combination showed lower p53 expression than EEGCB alone, this may reflect MDM2-mediated degradation during DNA damage response [49] or activation of p53-independent death pathways [50]. The slightly reduced p53 expression in the combination group compared to EEGCB alone suggests potential molecular interactions between EEGCB and Dox, which warrant further investigation. The upregulation of p53 expression following treatment with EEGCB, Dox, or their combination serves as a key indicator of programmed apoptosis pathway activation. These findings align with previous reports on natural product-induced apoptosis, including studies demonstrating that resveratrol-doxorubicin combination therapy induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells through modulation of the BAX: BCL-2 ratio and caspase-9 activation [51]. Similarly, concurrent administration of curcumin and doxorubicin has been shown to enhance apoptotic induction in breast cancer cells [52].

Given its potent effect on p53 expression, EEGCB holds promise as an adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, particularly in combination with standard chemotherapeutic agents. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying these interactions and validate the findings in in vivo models.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that EEGCB exerts its anticancer effects through a novel, multi-targeted mechanism in T47D breast cancer cells. Specifically, EEGCB: (1) induces apoptosis via p53 pathway activation, (2) exhibits enhanced combinatorial effect with doxorubicin by potentiating G2/M phase arrest, and (3) uniquely modulates cyclin D/E expression in a manner distinct from conventional chemotherapy. Notably, the extract's ability to simultaneously regulate multiple cell death and cell cycle pathways, while showing superior p53 activation compared to doxorubicin alone, reveals its potential as both a primary therapeutic agent and chemopotentiator. These findings not only validate the traditional medicinal use of G. cowa but also provide a mechanistic foundation for developing innovative, plant-based combination therapies for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. The dual targeting of tumor suppressor pathways and cell cycle regulators by EEGCB represents a promising strategy to overcome limitations of current monotherapies, warranting further investigation into its active phytoconstituents and in vivo efficacy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to express our gratitude to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia for funding this research. Special thanks to Prof. Masashi Kawaichi of the Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Japan, for providing the T47D breast cancer cells. We also extend our appreciation to the UGM laboratory team for their invaluable assistance and to the Department of Pharmacology at STIFARM Padang for their support in manuscript preparation.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia under the Basic Research Scheme (Doctoral Dissertation Research cluster; Contract No. 041/E5/PG.02.00. PL/2024, Subcontract No. 14/UN16.19/PT.01.03/PL/2024). The authors gratefully acknowledge this financial support.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

In this study, Ifora Ifora contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, visualization, software, investigation, and writing of the original draft. Dachriyanus Hamidi was responsible for validation, supervision, investigation, and writing, review, and editing. Meri Susanti contributed to resources, project administration, and writing-review and editing. Fatma S. Wahyuni was involved in conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing-review and editing, as well as funding acquisition.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660, PMID 33538338.

Harbeck N, Penault Llorca F, Cortes J, Gnant M, Houssami N, Poortmans P. Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019 Sep;5(1):66. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0111-2, PMID 31548545.

Novirianthy R, Syukri M, Gondhowiardjo S, Suhanda R, Mawapury M, Pranata A. Treatment acceptance and its associated determinants in cancer patients: a systematic review. Narra J. 2023;3(3):e197. doi: 10.52225/narra.v3i3.197, PMID 38450342.

Chunarkar Patil P, Kaleem M, Mishra R, Ray S, Ahmad A, Verma D. Anticancer drug discovery based on natural products: from computational approaches to clinical studies. Biomedicines. 2024;12(1):201. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12010201, PMID 38255306.

Aware CB, Patil DN, Suryawanshi SS, Mali PR, Rane MR, Gurav RG. Natural bioactive products as promising therapeutics: a review of natural product-based drug development. S Afr J Bot. 2022;151:512-28. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2022.05.028.

Dewi IP, Dachriyanus, Aldi Y, Ismail NH, Hefni D, Susanti M. Comprehensive studies of the anti-inflammatory effect of tetraprenyltoluquinone a quinone from Garcinia cowa Roxb. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024 Feb;320:117381. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.117381, PMID 37967776.

Rahman AU, Panichayupakaranant P. Exploring the diverse biological activities of Garcinia cowa: implications for future cancer chemotherapy and beyond. Food Biosci. 2024;61:104525. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.104525.

Andayani R, Armin F, Mardhiyah A. Determination of the total phenolics and antioxidant activity in the rind extracts of Garcinia mangostana L, Garcinia Cowa roxb, and garcinia atroviridis griff. Ex T. Anders. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2020;13(8):149-52. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2020.v13i8.36525.

Ifora I, Hamidi D, Susanti M, Hefni D, Wahyuni FS. Enhancing chemotherapeutic efficacy: synergistic cytotoxic effect of garcinia cowa bark extract and doxorubicin in T47D breast cancer cells. Trop J Nat Prod Res. 2025 Jan 31;9(1):67-72. doi: 10.26538/tjnpr/v9i1.10.

Ifora I, Hamidi D, Susanti M, Wahyuni FS. Synergistic anti-migration effects of garcinia cowa and doxorubicin in T47D breast cancer cells: a scratch assay analysis. J Drug Delivery Ther. 2025;15(2):74-8. doi: 10.22270/jddt.v15i2.7022.

Otto T, Sicinski P. Cell cycle proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017 Jan;17(2):93-115. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.138, PMID 28127048.

Levine AJ. Targeting the P53 protein for cancer therapies: the translational impact of P53 research. Cancer Res. 2022;82(3):362-4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-2709, PMID 35110395.

Wang H, Guo M, Wei H, Chen Y. Targeting p53 pathways: mechanisms structures and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):1-35.

Marei HE, Althani A, Afifi N, Hasan A, Caceci T, Pozzoli G. p53 Signaling in cancer progression and therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):703. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-02396-8, PMID 34952583.

Kciuk M, Gielecinska A, Mujwar S, Kolat D, Kaluzinska Kolat Z, Celik I. Doxorubicin an agent with multiple mechanisms of anticancer activity. Cells. 2023 Feb;12(4):659. doi: 10.3390/cells12040659, PMID 36831326.

Sukardiman S, Balqianur T. The role of ethyl acetate fraction of andrographis paniculata and doxorubicin combination toward the increase of apoptosis and decrease of VEGF protein expression of mice Fibrosarcoma cells. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(4):347-50.

Rawat PS, Jaiswal A, Khurana A, Bhatti JS, Navik U. Doxorubicin induced cardiotoxicity: an update on the molecular mechanism and novel therapeutic strategies for effective management. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;139:111708. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111708, PMID 34243633.

Mollaei M, Hassan ZM, Khorshidi F, Langroudi L. Chemotherapeutic drugs: cell death and resistance related signaling pathways are they really as smart as the tumor cells? Transl Oncol. 2021;14(5):101056. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101056, PMID 33684837.

Abubakar AR, Haque M. Preparation of medicinal plants: basic extraction and fractionation procedures for experimental purposes. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2020;12(1):1-10. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_175_19, PMID 32801594.

Hamidi D, Aulia H, Susanti M. High-performance thin-layer chromatography: densitometry method for determination of rubraxanthone in the stem bark extract of Garcinia cowa Roxb. Pharmacogn Res. 2017;9(3):230-3. doi: 10.4103/pr.pr_144_16, PMID 28827962.

Yusuf H, Novia H, Fahriani M. Cytotoxic activity of ethyl acetate extract of Chromolaena odorata on MCF7 and T47D breast cancer cells. Narra J. 2023;3(3):1-9. doi: 10.52225/narra.v3i3.326.

Kim KH, Sederstrom JM. Assaying cell cycle status using flow cytometry. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2015 Jul;111:28.6.1-28.6.11. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2806s111, PMID 26131851.

Toprak SK, Dalva K, Cakar MK, Kursun N, Beksac M. Flow cytometric evaluation of cell cycle regulators (cyclins and cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors) expressed on bone marrow cells in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia and multiple myeloma. Turk J Haematol. 2012 Mar;29(1):17-27. doi: 10.5505/tjh.2012.33602, PMID 24744619.

Al Zouabi NN, Roberts CM, Lin ZP, Ratner ES. Flow cytometric analyses of p53-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cancer cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2255:43-53. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1162-3_5, PMID 34033093.

Dewi IP, Dachriyanus, Aldi Y, Ismail NH, Osman CP, Putra PP. A new xanthone from Garcinia cowa Roxb. and its anti-inflammatory activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2025 Mar;343:119380. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2025.119380, PMID 39929399.

Gondokesumo ME, Pardjianto B, Sumitro SB, Widowati W, Handono K. Xanthones analysis and antioxidant activity analysis (applying ESR) of six different maturity levels of mangosteen rind extract (Garcinia mangostana linn.). Pharmacogn J. 2019 Mar;11(2):369-73. doi: 10.5530/pj.2019.11.56.

Francik R, Szkaradek N, Zelaszczyk D, Marona H. Antioxidant activity of xanthone derivatives. Acta Pol Pharm. 2016 Nov;73(6):1505-9. PMID 29634104.

Zhang H, Li X, Kang M, Li Z, Wang X, Jing X. Sustainable ultrasound assisted extraction of Polygonatum sibiricum saponins using ionic strength responsive natural deep eutectic solvents. Ultrason Sonochem. 2023;100:106640. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106640, PMID 37816271.

Nhan NT, Nguyen PH, Tran MH, Nguyen PD, Tran DT, To DC. Anti-inflammatory xanthone derivatives from Garcinia delpyana. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2021 May 4;23(5):414-22. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2020.1767079, PMID 32432493.

Wahyuni FS, Febria S, Arisanty D. Apoptosis induction of cervical carcinoma HeLa cells line by dichloromethane fraction of the rinds of garcinia cowa roxb. Phcog J. 2017;9(4):475-8. doi: 10.5530/pj.2017.4.76.

Sae Lim P, Seetaha S, Tabtimmai L, Suphakun P, Kiriwan D, Panichayupakaranant P. Chamuangone from Garcinia cowa leaves inhibits cell proliferation and migration and induces cell apoptosis in human cervical cancer in vitro. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2020;72(3):470-80. doi: 10.1111/jphp.13216, PMID 31875979.

Xia Z, Zhang H, Xu D, Lao Y, Fu W, Tan H. Xanthones from the leaves of garcinia cowa induce cell cycle arrest apoptosis and autophagy in cancer cells. Molecules. 2015;20(6):11387-99. doi: 10.3390/molecules200611387, PMID 26102071.

Marinello J, Delcuratolo M, Capranico G. Anthracyclines as topoisomerase II poisons: from early studies to new perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(11):3480. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113480, PMID 30404148.

Lee J, Choi MK, Song IS. Recent advances in doxorubicin formulation to enhance pharmacokinetics and tumor targeting. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(6):802. doi: 10.3390/ph16060802, PMID 37375753.

Sarkar E, Khan A, Ahmad R, Misra A, Raza ST, Mahdi AA. Synergistic anticancer efficacy of curcumin and doxorubicin combination treatment inducing S-phase cell cycle arrest in triple negative breast cancer cells: an in vitro study. Cureus. 2024 Dec;16(12):e75047. doi: 10.7759/cureus.75047, PMID 39749050.

Mirzaei S, Gholami MH, Zabolian A, Saleki H, Bagherian M, Torabi SM. Resveratrol augments doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy: a novel therapeutic strategy. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2023 Feb;16(3):280-306. doi: 10.2174/1874467215666220415131344, PMID 35430977.

Qi F, Zhang F. Cell cycle regulation in the plant response to stress. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1765. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01765, PMID 32082337.

Hashim GM, Shahgolzari M, Hefferon K, Yavari A, Venkataraman S. Plant-derived anti-cancer therapeutics and biopharmaceuticals. Bioengineering. 2024;12(1):7. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering12010007, PMID 39851281.

Choi SY, Shen YN, Woo SR, Yun M, Park JE, Ju YJ. Mitomycin C and doxorubicin elicit conflicting signals by causing accumulation of cyclin E prior to p21WAF1/CIP1 elevation in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2012 Jan;40(1):277-86. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1184, PMID 21887464.

Yesilkanal AE, Johnson GL, Ramos AF, Rosner MR. New strategies for targeting kinase networks in cancer. J Biol Chem. 2021 Oct;297(4):101128. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101128, PMID 34461089.

Shi A, Liu L, Li S, Qi B. Natural products targeting the MAPK-signaling pathway in cancer: overview. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024 Jan;150(1):6. doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-05572-7, PMID 38193944.

Jabbour Leung NA, Chen X, Bui T, Jiang Y, Yang D, Vijayaraghavan S. Sequential combination therapy of CDK inhibition and doxorubicin is synthetically lethal in p53-mutant triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016 Apr;15(4):593-607. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0519, PMID 26826118.

Thorn CF, Oshiro C, Marsh S, Hernandez Boussard T, McLeod H, Klein TE. Doxorubicin pathways: pharmacodynamics and adverse effects. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2011 Jul;21(7):440-6. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32833ffb56, PMID 21048526.

Lee MG, Lee KS, Nam KS. Combined doxorubicin and arctigenin treatment induce cell cycle arrest associated cell death by promoting doxorubicin uptake in doxorubicin resistant breast cancer cells. IUBMB Life. 2023 Sep;75(9):765-77. doi: 10.1002/iub.2772, PMID 37492896.

Shan T, Ma Q, Guo K, Liu J, Li W, Wang F. Xanthones from mangosteen extracts as natural chemopreventive agents: potential anticancer drugs. Curr Mol Med. 2011 Nov;11(8):666-77. doi: 10.2174/156652411797536679, PMID 21902651.

Kurniawan YS, Priyangga KT, Jumina PHD, Pranowo HD, Sholikhah EN, Zulkarnain AK. An update on the anticancer activity of xanthone derivatives: a review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021 Nov;14(11):1144. doi: 10.3390/ph14111144, PMID 34832926.

Oriola AO, Kar P. Naturally occurring xanthones and their biological implications. Molecules. 2024;29(17):4241. doi: 10.3390/molecules29174241, PMID 39275090.

Xu XH, Liu QY, Li T, Liu JL, Chen X, Huang L. Garcinone E induces apoptosis and inhibits migration and invasion in ovarian cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10718. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11417-4, PMID 28878295.

Qin JJ, Li X, Hunt C, Wang W, Wang H, Zhang R. Natural products targeting the p53-MDM2 pathway and mutant p53: recent advances and implications in cancer medicine. Genes Dis. 2018 Sep;5(3):204-19. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2018.07.002, PMID 30320185.

Al Madhagi H. Natural products induced cancer cell paraptosis. Food Sci Nutr. 2024;12(11):9866-71. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.4461, PMID 39619980.

Rai G, Mishra S, Suman S, Shukla Y. Resveratrol improves the anticancer effects of doxorubicin in vitro and in vivo models: a mechanistic insight. Phytomedicine. 2016;23(3):233-42. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.12.020, PMID 26969377.

Ashrafizadeh M, Zarrabi A, Hashemi F, Zabolian A, Saleki H, Bagherian M. Polychemotherapy with curcumin and doxorubicin via biological nanoplatforms: enhancing antitumor activity. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Nov;12(11):1084. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12111084, PMID 33187385.