Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 90-101Reviewl Article

NANOTECHNOLOGY REVOLUTION IN TREATING VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS: A BREAKTHROUGH BEYOND CONVENTIONAL THERAPIES

DEVANTH D. GOWDA, SHARANYA PARAMSHETTI, MOHIT ANGOLKAR, DARSHAN PATIL, ASHA SPANDANA K. M.*

Department of Pharmaceutics, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research (JSS AHER), Mysuru-570015, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Asha Spandana K M; *Email: asha@jssuni.edu.in

Received: 11 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 22 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is an extremely common infection; millions of women all over the world are affected. The main etiologic agent responsible for its development is Candida albicans. It is characterize by burning, itching and the presence of a thick and white discharge. VVC may be divided into two categories: simple and complex. Recurring forms of the disease pose difficult challenges to clinical management. An ability to form Candida biofilms on vaginal mucosa may be one of the reasons for the development of resistant infections, further increasing resistance towards treatment. The complications in managing infection due to the constantly rising resistance of Candida to commonly used antifungal drugs call for alternative therapies. The conventional methods of treatments, which include topical and oral antifungals, too often result in limited success with recurrence or side effects against such resistant strains. Nanotechnology therefore presents a promising alternative, as Nano-drug delivery systems enhance localized drug delivery by allowing more precise targeting of fungal cells. It can, therefore, overcome the resistance and deficiencies of the conventional mode of therapy. Various studies continue in nano medicine to develop better therapies in order to handle VVC with better outcome and management.

Keywords: Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), Nanotechnology, Nano-drugs, Candida species, Drug resistance, Toxicity, Targeted drug delivery

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.54550 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

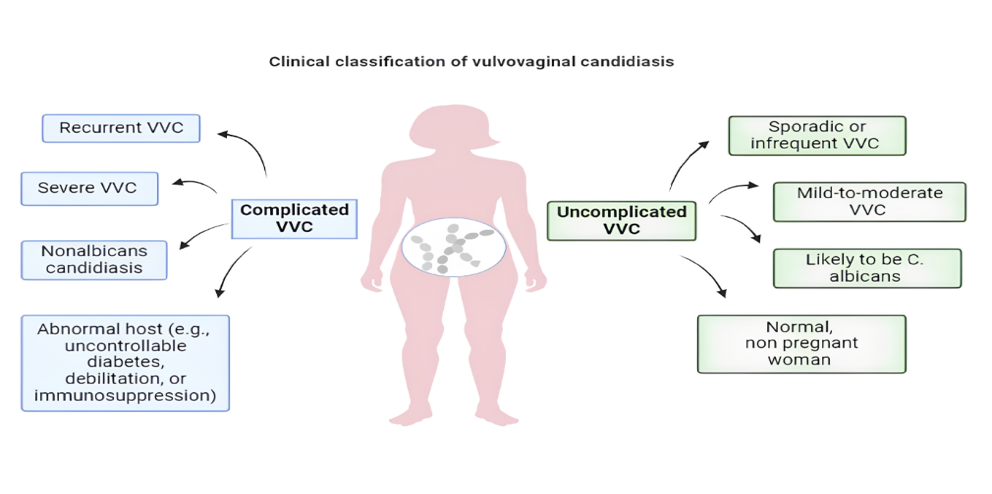

Candida vulvovaginitis, also known as vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), was first reported by Wilkinson in 1849 and remains a significant issue affecting women's quality of life. This condition arises from an overgrowth of yeast in the female reproductive system and is a common reason for gynaecological consultations. About 75% of women experience VVC at some point during their reproductive years, with nearly half having recurrent episodes [1]. Ninety to ninety-five percent of vaginal candidiasis cases are due to Candida albicans; the rest six percent are due to Candida glabrata, tropicalis, krusei, and parapsilosis. Even though Candida albicans typically lives in the normal vaginal microbiota, an imbalance in the vaginal macrobiotic and the yeast's attachment to and colonisation of epithelial cells can cause the yeast to overgrow. The development of virulence factors including blastoconidia and pseudo hyphae, which can harm the vaginal epithelium, as well as the synthesis of enzymes, and phospholipases, are involved in this transition from an asymptomatic to symptomatic infection [2]. The existence of symptoms as stated by the patient is necessary for an accurate diagnosis of VVC. Common symptoms include atypical vaginal discharge that is cheese-like, watery, or sparse, as well as vulvar pruritus, discomfort, dysuria, and dyspareunia. A definitive diagnosis entails identifying Candida species through lab tests and confirming concurrent inflammatory reactions like itching, burning, and irritation. Presence of Candida species alone does not confirm active infection; symptoms of inflammation must accompany their presence to diagnose VVC effectively [3].

Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (RVVC) is defined by frequent occurrences-typically four or more within one year-characterized by distinct clinical features like redness of the external genital area, vaginal discharge, swelling, and sensations of burning or soreness. Diagnosis of RVVC requires laboratory confirmation through culture of Candida species or microscopic examination of wet preparations. It's important to differentiate RVVC from other gynaecological conditions such as bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, and gonorrhoea, as symptoms can overlap. Accurate diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical assessment and specific laboratory results related to Candida species [4]. Candida albicans is actually one of the major organisms responsible for the development of VVC, and it forms biofilms that are extremely complex. These biofilms contribute to treatment challenges because the yeast embedded within them can develop resistance to antifungal medications. While biofilms are also implicated in bacterial vaginosis, conclusive evidence supporting their role in this condition is still being investigated [5]. It is estimated that 5% of women worldwide suffer from RVVC and thus are obliged to put up with three to four yeast infections in a year. Approximately 138 million women are thus affected annually, with an approximate of half a billion affected during their lifetime. The major causes of RVVC include immunological alterations, genetic, physiological changes, and some behavioural habits such as the use of antibiotics and contraceptives in high frequency. One of the major problems associated with RVVC is antifungal resistance, and the main contributing factor involves fungal biofilms. The biofilms protect the fungi from all types of antifungal drugs by creating a barrier that complicates treatment and further promotes their resistance [6]. Several factors are implicated in its etiology, such as disturbed vaginal microbiota, genetic predisposition, and the type of Candida. The healthy vaginal microbiome is mainly colonized by Lactobacillus spp., like L. iners and L. crispatus, and it is crucial for maintaining the health of the vagina through the production of D-lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide, which has candida growth-suppressing activity. Consequently, it favors increased Candida adherence to the mucosal epithelium, facilitating in this way the pathological yeast growth and increasing susceptibility to infection [7].

Nanocarriers like liposomes, nanoemulsions, solid lipid nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, and mesoporous silica nanoparticles can be designed to Improve Drug Solubility and Bioavailability – Several powerful drugs have low water solubility, reducing their absorption and efficacy. Nanocarriers enhance solubility and enhance targeted delivery. Bypass Drug Resistance Mechanisms – Nanocarriers can bypass efflux pumps, extend drug retention at the site of action, and enhance intracellular drug deposition, especially in cancer and antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. Sustained and Controlled Release – Encapsulation within nanocarriers allows extended release of the drug, minimizing the frequency of dosing and reducing side effects. Combination Therapy – With the ability to deliver multiple drugs or bioactive molecules, nanocarriers allow synergistic interactions, lowering the chances of resistance development. Protection against Degradation – Enzyme-degradable drugs (e. g., peptides, nucleic acids) are stabilized by nanocarrier encapsulation, guaranteeing their viability in biological surroundings. The present review gives a critical overview of the current state of affairs concerning VVC, including updated information on the most effective therapeutic approaches, with a particular emphasis on emerging applications of nanosystems. VVC represents an important fungal infection that affects tens of millions of women worldwide; its recurrence generally occurs because Candida species are the main causative agents. The persistence of VVC, along with the development of resistance to antifungal therapy, constitutes a real need to find more active and specific therapeutic approaches. To ensure a comprehensive and up-to-date review of the literature, a systematic search was conducted using major scientific databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, SciVal, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search strategy employed Boolean operators (AND/OR) to refine combinations of the following key terms: “vulvovaginal candidiasis”, “Candida infections”, “nanotechnology”, “nanoformulations”, and “antifungal nanocarriers”. Filters were applied to include only peer-reviewed articles published within the last decade (2014–2025), ensuring the inclusion of the most recent and relevant advancements in the field.

Fig. 1: Diagrammatic representation of the classification of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) into two categories: complicated and uncomplicated VVC. Each type is associated with specific clinical features and patient characteristics

Biofilm formation

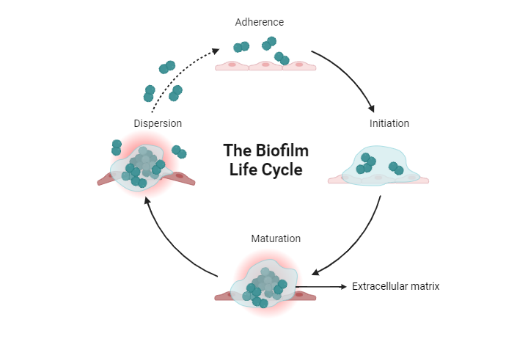

Fungal biofilms play a crucial role in over 60% of human microbial infections, including RVVC. Candida albicans is the primary species used to study biofilm formation in this context. A biofilm consists of a microbial settled community where cells attach irreversibly to surfaces or one another, encased within an extracellular polysaccharide matrix. In RVVC, the following stages describe biofilm progression: adherence, initiation, maturation, and dispersion [8] (fig. 2).

At the initial adhesion phase, yeast cells attach to surfaces, establishing a foundation upon which the biofilm grows. Next, during the initiation or proliferation stage, elongated filamentous forms called pseudo hyphae and hyphae emerge, colonizing the growing biofilm. During the maturation process, cells increase production of extracellular polymers, constructing the biofilm's protective matrix, which is essential for resilience against environmental pressures and drug penetration. Lastly, during dispersion, mostly yeast cells detach from the biofilm, potentially spreading the infection further [9].

Fig. 2: Diagrammatic representation of the biofilm life cycle, which describes how microorganisms like bacteria and fungi form and develop biofilms over time

Treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis

Treatment of uncomplicated VVC

Azole antifungals remain the mainstay in the treatment of uncomplicated VVC as they inhibit the synthesis of essential sterols in fungal cells by suppressing the enzyme CYP51.[10] Yet, despite such ubiquitous prescription and use, no substantial distinction in efficacy has been made between systemic and topical azoles, even though the former acts upon the whole body, with greater potential for systemic side effects, including hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal upset, headache, and dangerous drug interactions, particularly during pregnancy. Topical azoles such as clotrimazole, miconazole, and butoconazole are among the most commonly prescribed three-day regimens. Symptoms typically improve after 2-3 days. Although these treatments may have some local reactions, including the feeling of discomfort and itching, they generally remain the treatment of choice due to their localized action with limited risk of serious adverse effects [11].

According to the CDC, uncomplicated VVC is best treated with topical azoles. Nevertheless, oral antifungal fluconazole involves only a single high-dosage treatment and thus still remains popular, despite its link to as high as 50% relapse rates within six months of treatment. In this regard, to satisfy these two issues, one may suggest the combined use of both oral and topical azoles as a promising option in order to reduce the risk of recurrence [12].

Besides classical treatments based on azoles, other approaches have been pursued where probiotics and boric acid-based TOL-463 are showing immense promise. Probiotics have been shown-especially exogenous Lactobacilli-to inhibit in vitro Candida albicans biofilm formation [13]. The efficacy of topical clotrimazole with the Unilen® Microbio+tablet containing oral clotrimazole, live Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains, melatonin, and Lactobacillus acidophilus GLA-14 has been estimated as 90% versus 80% for the second group treated only with medication, while a relapse rate in the latter is almost two times higher. This would suggest that the use of advanced preparations along with classic therapies would promote better general outcomes with less recurrence as well as less consumption of perpetual prescription medication in cases of persistent VVC [12, 14] However, a critical literature review conducted by the CDC did not find sufficient data to recommend the use of probiotics as a standard line of treatment for VVC.

Likewise, TOL-463 is a boric acid and EDTA vaginal anti-infective in gel and insert forms studied for the treatment of VVC. In 2019, in a trial enrolling 106 women, including VVC, bacterial vaginosis, or both, 92% of insert-users and 81% of gel-recipients with VVC recovered. Symptoms improved on average within seven days; 19% of participants reported mild vaginal and vulvar discomfort. Nevertheless, TOL-463 was still more effective against VVC than it was against BV because fewer follow-up therapies were required when using the insert or gel for VVC compared to BV. Due to these promising effects, the CDC has still not included the use of probiotics or even TOL-463 in their guidelines, emphasizing the requirement for further studies to establish their effectiveness and safety [15].

Treatment of complicated VVC

Treatment of VVC with non-albicans species are more difficult, especially those caused by C. glabrata and C. tropicalis, due to the resistance of these species to standard antifungal therapies. About half of the affected women may remain asymptomatic or exhibit minimal symptoms. German guidelines recommend treating C. glabrata infections with local applications of nystatin or ciclopiroxolamine. If these are ineffective, CDC recommends two weeks of daily intravaginal 600 mg boric acid gelatin capsules, although this is with risks to fertility and should be used only in post-childbearing women [16]. A 1995-2004 study by Philipps showed amphotericin B vaginal suppositories effective in 8 out of 10 cases of non-albicans VVC, although some C. glabrata infections persisted [17].

In diabetic patients, it is more common due to the excess sugar in vaginal cells, which favors Candida adhesion and impairs the immune response [18]. Non-albicans Candida species, mainly C. glabrata, are highly prevalent and have reduced susceptibility to conventional therapies. SGLT2 inhibitors, such as dapagliflozin and canagliflozin, used in the management of diabetes, can increase the risk for VVC due to its mode of action of decreasing blood sugar levels and increasing glucose excretion through the urine [19].

Infection with VVC among HIV-infected women can be more frequent, severe, and symptomatic, with more serious symptoms, especially in those with profound immunosuppression. However, they typically respond well to treatment, just like non-HIV-infected women. However, VVC infection does not increase the risk of acquiring HIV infection [20] Generally, the treatment principles of VVC in HIV-infected women are similar to the treatment principles for uncomplicated VVC in non-HIV-infected patients [21].

Treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) in patients with azole intolerance or resistance

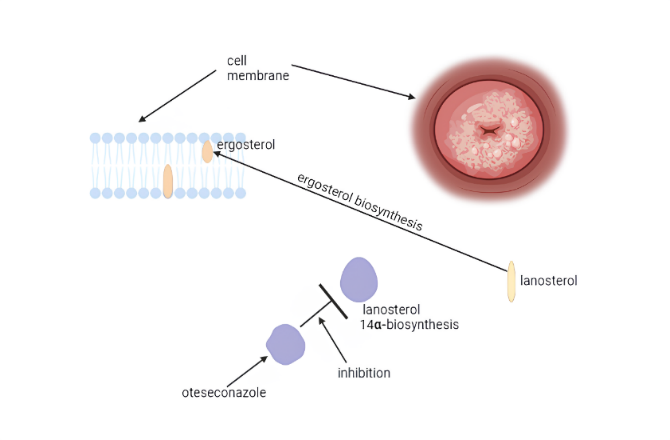

Recent advancements have introduced Oteseconazole, a novel oral azole medication that has gained Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. Distinctively, unlike existing azoles, Oteseconazole exhibits minimal binding affinity toward human Cytochrome P450 subfamily 51 family member polypeptide CYP51, thereby mitigating severe adverse reactions commonly associated with traditional azoles (fig. 3) [22].

According to a 2022 published Phase III trial involving multiple centers, researchers randomly assigned participants to take either oteseconazole or fluconazole. The results demonstrated that a regimen of oteseconazole consisting of 600 mg on day 1 (four doses of 150 mg), followed by 450 mg on day 2 (three doses of 150 mg), proved comparable to fluconazole regarding treating an initial attack of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC). Subsequently, patients received oteseconazole 150 mg daily once per week throughout the follow-up period of eleven weeks during maintenance treatment. This finding suggests that oteseconazole might offer equal effectiveness to standard treatments while possibly reducing the need for frequent dosages. Fluconazole was used as a comparator, and no clinically important changes were reported in this Phase IIa study by Brand et al. using 55 patients. Total there are three different dosing regimens given for the oteseconazole: 300 mg once daily, 600 mg once daily, and 600 mg twice a day while in fluconazole group received 150 mg of fluconazole orally once a daily for three days. Remarkably, oteseconazole had an MIC against the fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata that was only about 1/64 that of fluconazole. Results may indicate greater potency against fluconazole-resistant strains with oteseconazole [23]. A sensitivity analysis, carried out among 219 subjects, revealed that the activity of oteseconazole versus fluconazole varied greatly, with oteseconazole's effects on fungal samples ranging from less than or equal to 0.0005 to more than 0.25 µg/ml, whereas fluconazole exhibited concentrations ranging from under 0.06 to 32 µg/ml [24]. It should be noted that only a limited percentage of participants in each study had C. glabrata identified - approximately 11.8% and 1.8%, respectively. Therefore, one limitation of both investigations is their relatively small sample sizes where this particular strain was concerned [24].

Fig. 3: Diagrammatic representation of the oteseconazole-mechanism of action. Like triazoles, oteseconazole blocks the fungal enzyme lanosterol 14α-demethylase, which is responsible for ergosterol production

Treatment of recurrent VVC

Many women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis around the world suffer from this persistent, refractory infection, which can be extremely incapacitating. Three or more symptomatic bouts of vulvovaginal candidiasis within a year is considered recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis in the United States [10]. Although the Infectious Diseases Society of America and European criteria define RVVC as at least four or more symptomatic episodes within a year, current guidelines for diagnosis and therapy suggest that at least three symptomatic episodes can already establish the diagnosis of RVVC. Until the end of their lifetime, an estimated 372 million women worldwide will have RVVC, which projects to about 3,871 cases per 100,000 women [25]. There is less resistance to treatment when vaginitis is caused by non-C. albicans strains. For the treatment of RVVC, a topical antifungal or 150 mg of oral fluconazole is usually administered for induction for the ensuing 10–14 d. Following induction, there is a six-month maintenance therapy consisting of 150 mg of oral fluconazole. Women with RVVC can become resistant to fluconazole; however before it is confirmed it is necessary that improper medication usage be excluded [19]. Long-term therapy with fluconazole is expensive and can cause numerous side effects. Moreover, this type of therapy alleviates symptoms only in a small number of women, and about 50% of them will develop recurrent disease a few months after treatment is completed [26]. The topical therapies for RVVCs mainly involve vaginal boric acid, miconazole, terconazole, clotrimazole. Some studies claim that azoles are superior drugs in comparison to nystatin [27]. The poor response rate of them indicates that more efficient and safe novel long-term treatments for RVVC are required.

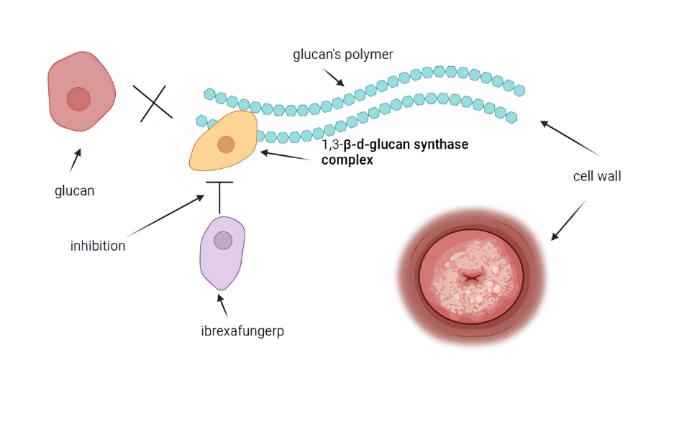

In June 2021, the FDA approved ibrexafungerp, a new oral glycan synthase inhibitor (fig. 4), for treating RVVC in postmenopausal women [28]. Ibrexafungerp is effective against various Candida strains resistant to azoles and echinocandins. Ibrexafungerp is administered in doses of 300 mg, taken orally as 150 mg twice daily. In vitro, the concentration-dependent fungicidal activities against Candida spp. by ibrexafungerp were determined. There was no effect from the presence of azole resistance on this activity [28]. Compared to placebo, ibrexafungerp showed statistically and clinically meaningful induction of a clinical response and prolonged symptom resolution in patients with acute VVC in the phase III clinical trials. Summary of studies regarding oteseconazole and ibrexafungerp for the treatment of VVC is presented in table 1.

Fig. 4: Diagrammatic representation of the ibrexafungerp mechanism of action which inhibits the 1, 3-β-d-glucan synthase complex noncompetitively and thus prevents the production of 1, 3-β-d-glucan. Inhibition of the glucan synthase complex causes cell instability, followed by lysis. Although the mechanism is similar to that for echinocandins, the latter has an entirely different structural makeup

Table 1: Summary of the existing research related to the effectiveness of ibrexafungerp and oteseconazole in VVC treatment

| Author of the study | Year of publication | Number of patients | Dose | Duration of symptom resolution | Adverse effect |

| Brand SR et al. [23] | 2022 | 55 | VT-1161 regimens included 300 mg once daily for 3 d, 600 mg once daily for 3 d, or 600 mg twice daily for 3 d. Fluconazole, 150 mg as a single dose, was also administered. | 28 d | Infections: nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infections, bacterial vaginitis, nausea. |

| Martens M G et al. [24] | 2022 | 219 | A single 600 mg oral dose of oteseconazole was administered on day 1 as 4 × 150 mg, and on day 2, 450 mg was administered as 3 × 150 mg with matching placebo capsules. Alternatively, three sequential oral doses of fluconazole were given. | 2 w | Urinary tract infection, bacterial vaginosis, headache, nausea, diarrhea, upper respiratory tract infection, fever. |

| Schwebke et al. [29] | 2022 | 366 | Patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either 300 mg of ibrexafungerp twice daily or a placebo. | 25 d | Side effects related to treatment include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, pneumonia, and bronchial hyperactivity. |

| Grant LM et al. [28] | 2022 | 1 | The dosage of Ibrexafungerp was 375 mg twice a day, over a course of three days and with an additional dose on day 14 of 375 mg twice. | The symptoms recurred in this regimen before day 14 of the patient. | Fatigue, nausea. |

Drawbacks and challenges associated with conventional treatments for vulvovaginal candidiasis

Conventional treatments for vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) encounter various challenges and limitations. These include issues with of acute VVC infections, which can result in ineffective treatment and incomplete resolution of symptoms [30]. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) presents a notable challenge due to the rising occurrence of non-albicans Candida species. Some species are innately resistant to usual antifungals like fluconazole, and early initiation of supportive treatment for a longer period is required [31]. Furthermore, the scarcity of effective pharmacological options and the elevated incidence of azole resistance, notably in Candida glabrata infections, complicate the management of RVVC. Addressing these challenges necessitates evidence-based protocols that take into account the availability of treatments at a national level [32, 33].

Limited FDA-approved treatments for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, prompting the need for alternative therapies [30]. This makes treating recurrent Candida glabrata vulvovaginal candidiasis very challenging in view of high rates of azole resistance, limited treatment options, and protracted therapy regimens required [32]. Traditional treatments for vulvovaginal candidiasis are hindered by issues such as antifungal resistance, adverse effects, and frequent recurrence, prompting the need for extended maintenance therapy and alternative treatment approaches to address these challenges [31]. Traditional treatments for vulvovaginal candidiasis encounter difficulties such as the requirement for better taste masking, enhanced bioavailability, and improved sensory properties in formulations [33]. Standard treatments for vulvovaginal candidiasis are limited by factors such as short duration of action and potential side effects, highlighting the need for advancements in delivery systems to enhance both effectiveness and safety [34].

Nano drug delivery systems against candidiasis

Need to develop nano drug delivery system against vulvovaginal candidiasis above conventional treatment

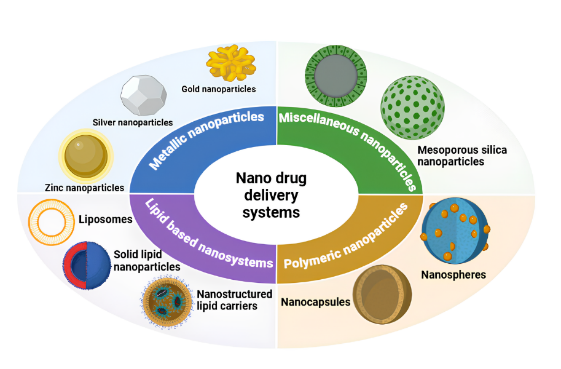

The advancement of nano drug delivery systems for treating vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is critical given the drawbacks of conventional treatments, which frequently result in adverse effects and diminished effectiveness against VVC [35]. Nanosystems like liposomes, nanoparticles (fig. 5), and micelles enhance drug delivery, bio distribution, and retention in vulvovaginal tissues, effectively overcoming the limitations of conventional therapies [36]. Research indicates that nanodrug delivery systems such as hypericin-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers and chitosan nanoparticles containing miconazole and farnesol demonstrate substantial antifungal effectiveness against Candida albicans, the primary cause of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), in both laboratory and animal studies. These findings highlight their potential as promising alternatives for VVC treatment [37]. These advanced drug delivery systems have the potential to improve treatment effectiveness, minimize side effects, address microbial resistance, and offer prolonged drug release. Their development is crucial in advancing the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC).

Nano drug delivery systems such as PDT-mediated hypericin-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) demonstrate superior effectiveness against vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) compared to traditional treatments. They effectively tackle resistance and reduce adverse effects associated with current antifungal therapies [35]. Nano drug delivery systems provide extended drug release, better retention, and increased uptake in vulvovaginal tissues, overcoming drawbacks of traditional treatments for candidiasis [36]. Nanosystems such as AmB-loaded PLGA-PEG nanoparticles combined with ultrasound improve drug delivery, enhance efficacy, decrease fungal burden, enhance tissue integrity, and regulate cytokines and oxidative stress, surpassing conventional treatment methods [38]. With rising cases of vulvovaginal candidiasis and limited antifungal therapies available, there is a growing interest in investigating lycopene and mesoporous silica nanoparticles as potential alternative treatments.

Fig. 5: Diagrammatic representation of the various types nano drug delivery system used in vulvovaginal candidiasis

Metallic nanoparticles

Research into metals in nanoparticle synthesis dates back to the 19th century with research done by Michael Faraday. The researcher found metallic particles in solutions and called them metallic colloids. Metal nanoparticles are defined based on size, and normally, they measure between 1 and 100 nanometer [39]. These include the inhibition of pathogen resistance, potential antifungal and antibacterial capabilities, chemical stability, reduced toxicity, fewer adverse effects, and the ability to adjust the size of the pores [40].

They also exert their antibacterial activity via the production of reactive oxygen species that will later accumulate on the cell surface, thus hindering the formation of the cell membrane, and block certain enzymes [41]. Again, these ROS are toxic because they lead to DNA damage and may activate programmed cell death pathways [42]. One major drawback of MNPs is their expensiveness and the fact that, due to their large surface energy, they frequently don't easily form stable colloidal suspensions because of aggregation via metal-metal bonds. This problem could, however, be successfully overcome by the co-use of a type of reducing agent or stabiliser, such as PVA. Aside from some basic Lewis sites with strong affinity for MNPs, it contains a number of long organic chains which may act as steric hindrances to prevent these bonds from forming [43]. hindrances to prevent these bonds from forming [43].

Gold nanoparticles

The biochemical, sensory, optical, and electrical features make gold a very promising material for controlled release in the therapeutic field. Moreover, gold is biocompatible with low toxicity [44]. Another consideration is the ease of production and modification of gold nanoparticles. With these considerations in mind, some research estimating the potential of AuNPs against Candida albicans was performed, mostly related to cutaneous candidiasis and VVC [44].

In these studies, AuNPs varied in size from 7 to 37 nm and exhibited different morphologies, including spherical, polygonal, and triangular shapes [42]. The size of AuNPs thus proved to be dependent while showing activities against Candida [45].

In vitro cytotoxicity studies by Rahimi et al. showed that AuNPs had very low potential for damaging erythrocytes and fibroblast cells. Accordingly, the results shown here demonstrate that the use of AuNPs could be a great option to treat candidiasis [46]. AuNPs are used in the treatment candidiasis because of they are biocompatible and have low cytotoxicity. The cytotoxicity of AuNPs in vitro has been found to be responsible for minimal damage to fibroblast and erythrocyte cells, and these cells are involved in tissue integrity and immunological function.

Silver nanoparticles

Another very promising kind of MNPs is represented by silver nanoparticles, largely applied as antimicrobials due to the potent antimicrobial effect they can exercise beyond microbial resistance [47].

Several studies have been done to determine the feasibility of treating candidiasis using AgNPs, given the antibacterial properties of silver [48]. Studies were done in vitro, whereby spherical AgNPs with sizes ranging between 2 and 15 nm were generated, and their efficiency against Candida tropicalis, Candida albicans, and fluconazole-resistant clinical isolates checked [49]. Since the observations were done in vitro, from these, it was possible to determine that AgNPs had antifungal potential.

Zinc nanoparticles

It is believed that zinc-containing nanoparticles, such as zinc oxide nanoparticles, have more potential as MNPs for controlled drug release than other metals because of their low toxicity and good biocompatibility [50]. Accordingly, the studies combined zinc with other drugs, such as nystatin and fluconazole, for a second line of treatment against Candida spp. Table 2 summarizes the various research conducted using MNP.

Lipid based nanosystems

There are many types of lipid-based nanosystems; all of them have different physicochemical constituents and features to reach specific therapeutic targets and responses. This article aims to present each system in as simple a way as possible while analysing their efficacy for the treatment of candidiasis. Table 3 is a compilation of recent studies on lipid-based nanosystems for candidiasis treatment. This has been raised with regard to the, bioactive substance, or molecule, therapeutic target and system composition, and development procedures.

a. Liposomes (LP)

Liposomes are spherical vesicles consisting of one or more phospholipid bilayers and surround a core of aqueous solution. Due to their structure, liposomes can entrap both hydrophilic, or water-soluble, substances as well as hydrophobic, or fat-soluble, substances; hence, they can be greatly applicable in pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and biomedical fields. Liposomes are similar to natural biological membranes, which gives them improved biocompatibility and flexibility. This technological development has tremendously enhanced the drug delivery of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic pharmaceuticals with very important clinical ramifications. Biocompatibility and biodegradability of the liposomes have further made them one of the primary delivery systems for pharmaceuticals [54].

Table 2: Summary of the studies according to the studied pathogen, types of MNPs used, and biological assays that were employed in treating candidiasis

| Metallic nanoparticle | Drug or active ingredients | Method of synthesis | Pathogens | Biological assay | Primary microbiological tests | Reference |

| Gold nanoparticle | Indolicidin | Synthesis using citrate as the reducing agent. | C. albicans isolated from burn injuries | In vitro | Nanoparticle with BR1 8 mm MIC Free indolicidin 50 mg/ml Gold nanoparticles 24.37 mg/ml Gold nanoparticles conjugated with indolicidin 12.5 mg/ml MFC Free indolicidin 150 mg/ml Gold nanoparticles 97.5 mg/ml | [51] |

| Silver nanoparticle | Amphotericin B | Green synthesis using Maytenusroyleanus extract as the reducing agent | C. albicans and C. tropicalis | In vitro | MIC: Non-incorporated nanoparticles: 125 mg/ml for C. albicans and 62.5 mg/ml for C. tropicalis. Incorporated nanoparticles: 5 mg/ml on C. albicans, 1.5 mg/ml on C. tropicalis. |

[52] |

| Zinc oxide nanoparticle | Fluconazole | Synthesized by wet chemical method | C. albicans isolated from vaginal samples | In vitro | MIC: Zinc oxide nanoparticles conjugated with fluconazole: 32–256 µg/ml. | [53] |

Liposomes offer huge therapeutic potential as carriers for the transportation of payloads and drugs to specified locations. The concept of such targeted delivery is referred to as the "magic bullet," a term coined in 1906 [55]. This encapsulation by liposomes thus improves the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic attributes of therapeutic agents, allowing for controlled and sustained release of drugs. Such controlled release minimizes the toxic effects in comparison with the same drug given without a delivery system [56]. Liposomes are defined as lipid bilayers to an aqueous medium that are continuous and sealed in vesicles. Sterols, antioxidants, and phospholipids, whether synthetic or natural, are usually the general components that make up the liposomes [39].

In the course of research in developing a drug delivery system using liposomes, several research groups have already been proved to be effective in controlling candidiasis. In the 1980s, one major study was conducted by Lopez-Berestein et al. (1984), where these researchers encapsulated amphotericin B in liposomes and used it to treat disseminated candidiasis in neutropenic mice infected with C. albicans. Multilamellar liposomes of AMB were synthesised without deoxycholate and single-and multiple-dose therapy studies were carried out. The results showed that free AMB did not cure the neutropenic infected mice; however, it did reduce the microbial load. In sharp contrast to this, however, all study animals could be significantly cured with the liposome-encapsulated AMB. The conclusion the authors drew was that the formulation of AMB into multilamellar liposomes allows for an effective treatment of the systemic infection by C. albicans and justifies the application of encapsulated drugs at high doses in neutropenic patients [57].

b. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs)

NLC is considered as the third and second generations of NE and SLN, respectively. NLCs are colloidal nanosystems with a hydrophobic core arranged in a solid lattice structure and incorporated in an aqueous surfactant shell [58]. The procedure for the preparation and assessment of its characteristics, as well as its biocompatibility, is almost identical to those of SLN. However, NLC has the advantage over SLN due to the partial substitution of SL with liquid lipid [59].

This partial substitution gives a system that accommodates the positive points of solid lipids, such as improved stability and controlled drug release, at the same time as it reduces some of the crystallization problems brought by solid lipids [60]. By this, it reduces the possibilities of drug expulsion during formulation and storage owing to reduced possibilities of polymorphic transitions. Furthermore, the introduction of the oil increases the drug loading capacities further into the structures of the nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) [61].

Song et al. detected increased permeability and stratum corneum retention of voriconazole in the Gel-NLC system [62]. Another paper showed that incorporating voriconazole into the latter improved its anti-Candida action. It lowered the biofilm cells' density and very substantially raised hyphal-to-yeast morphogenesis [63].

c. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs)

SLNs are colloidal systems in the submicronic range, mostly between 50 and 100 nm. These were developed in the early 1990s. Being the second generation of nanoemulsions (NE), they were considered a technological advancement with respect to this previous one since solid lipids replaced the oily component, providing better control over release and increasing system stability and that of the medication contained within [58].

According to the systematic review by Doktorovova et al. (2014), SLNs generally showed very low toxicity when various studies were considered from a nanotoxicological point of view. SLN dispersions are composed of solid lipids and surfactants in amounts of 1-30 weight percent and 0.5-5 weight percent, respectively. Various preparative techniques such as organic solvent-based techniques and different high-and low-energy techniques may be used for the preparation of SLNs. Some of the common production techniques are high-pressure homogenization, ultrasonication, microemulsions, solvent evaporation, solvent diffusion, and solvent injection [64].

Dynamic light scattering is normally utilized in measurement investigations at metrics like hydrodynamic diameter, polydispersity index, and zeta potential of the nanostructures. Electron microscopy techniques are exploited to investigate size and morphology.

d. Lipidic nanocapsules (LNC)

Lipid nanocapsules are a novel nano drug delivery system that Heurtault et al. developed at the start of the 2000s. Regarding that, LNCs are colloidal systems in core-shell structures, measuring between 20 and 100 nm. They have an oily nucleus consisting of medium-chain triglycerides, while they are covered by a pegylated surfactant and lecithin shell. Owing to these constituents, the lipid nanocapsules are highly biocompatible and can be administered via oral, topical, or parenteral routes [65].

Currently, two major processes are used for the preparation of lipid nanocapsules (LNC)

Reversible Temperature Using temperature without an organic solvent, polyethoxylated surfactants change their affinity through reversible temperature using just temperature. For an Interfacial Deposition of a Preformed Polymer, a water-miscible solvent is used to dissolve a polymer and a lipophilic medicine. The solution is added and magnetically stirred with an aqueous medium and a nonionic surfactant. A quite fast diffusion time occurs in the water; hence, the nanocapsules spontaneously form [65].

One of the major advantages of the LNC structure is enhanced rigidity, provided by the surfactant shell. Due to this, they become less sensitive to instability problems like Ostwald ripening and allow a high drug loading capacity [66]. Because of its powerful use, research teams have integrated azoles such as clotrimazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole into the nano drug delivery system to improve the treatment of candidiasis. In 2013, Santos et al. demonstrated that clotrimazole added to LNCs for the treatment of VVC did not lessen the medication's effectiveness against fluconazole-resistant strains of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata [67]. Lipid nanocapsules and nanostructured lipid carriers were developed by Domingues Bianchin et al. with the goal of reversing fluconazole resistance. Investigations took place on Candida albicans and other candida strains that prove these nanosystems restore the resistance. Another azole drug, itraconazole, showed improved activity against Candida albicans in vitro and in vivo when combined with LNCs [68].

Table 3: Summary of the research in the field of lipid-based nanosystems against candidiasis on a system type, bioactive chemical or compound, therapeutic target, system composition, and method used for the creation of a system basis

| System | Biologically active molecule or compound | Therapeutic target | Composition | Development method | Primary microbiological tests | Ref |

| Liposomes | Quercetin and gallic acid | Vulvovaginal candidiasis | Soybean lecithin | FLH followed by sonication | There was no cytotoxicity of polyphenol-liposomes against RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. | [69] |

Nano structured lipid carriers |

P. graveolens essential oil | Vulvovaginal candidiasis | Medium-chain triglycerides; Sorbitan monooleate; quitosan; water | HPH | MIC (mg/ml): C. albicans – ATCC18804: 512; CA01: 512 C. tropicalis – CT72A: 256; CT56: 256 C. krusei – ATCC6258: 512; CK02: 256 C. glabrata – CG40039: 256; RL24: 512 C. parapsilosis – RL01: 512; RL20: 128 |

[70] |

Solid lipid Nano particle |

Clotrimazole and Alphalipolic | Vulvovaginal candidiasis | dimethyldioctadecylammoniumbromide, TweenRV 80/Gliceryloleate | PIT | The MIC90, incorporated into SLN, remained at the level of 0.03 mg/ml, whereas cationic SLN showed a significant reduction to 0.015 mg/ml. | [71] |

Lipidic Nano capsule |

Itraconazole | Cutaneuscandidiais | Kolliphor RV HS 15, Labrafac, LipoidRV S-75, Carbopol 974 P # | PIT | ITC encapsulation into LNC improved its anti-C. albicans activity; showing a 29.37±0.25 mm diameter of the inhibition zone, compared to ITC solution. | [72] |

Polymeric nanoparticles (PN)

Since the 1970s, polymeric nanoparticles have been developed, which are colloidal systems. Nanometric systems fall within the size range from 5 nm to 1000 nm, although most of them measure between 100 and 500 nm. PNs can be obtained either from synthetic or natural polymers. There are two categories of PNs: nanocapsules-that actually include a polymeric wall surrounding an oily or watery core-and nanospheres, consisting of only a polymer matrix without any distinct core.

By combining different polymers, PNs can be prepared that will modulate physicochemical properties related to solubility, surface charge, encapsulation efficiency, and release profile. In the case of nanoparticle-based carriers, the goals of nanoparticle-based treatments of candidiasis are: to enhance the therapeutic efficacy and penetration, to lessen the toxicity, to target the site of infection, and to circumvent some of the disadvantages of conventional drugs [73].

Polymeric nanoparticles have been used for drug delivery against VVC. It has been revealed that miconazole, after being encapsulated into polymeric nanosystems, increased the drug efficacy compared to free administration [74]. In addition, reduced adverse effects were found after oral administration of Amphotericin B (AmB) [75].

Polymeric nanoparticles have reportedly shown potential in improving candidiasis treatment. However, very few studies table 4 have tried to analyze the nanoparticles' effect on the virulence of newly emerging non-albicans Candida strains.

Table 4: Summary of the literature regarding polymeric nanoparticle research for the treatment of candidiasis, considering the composition

Biologically active molecule or compound |

Therapeutic target | Composition | Development method | Main biological results | Ref |

| Miconazole and Farnesol | Vulvovaginal candidiasis | Chitosan and TPP | Solvent displacement | The in vitro cytotoxicity assay on fibroblast cells BALB/c 3T3 showed that the miconazole did not provide any toxicity up to a concentration of 125 µg/ml, very much like the nanoparticles. According to the MIC test, efficacy for NPs with miconazole/farnesol was determined at 2.0 µg/ml. | [74] |

| Amphotericin B | Vulvovaginal candidiasis | Eudragit RL100 coated with hyaluronic acid chitosan and TPP | Nano precipitation | After 48 h, the inhibition zone measured 12.50±1.37 mm. The in vivo assay revealed complete removal of C. albicans in 24 h. | [75] |

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN)

Due to their unique characteristics, mesoporous silica nanoparticles have been among the promising matrices for the preparation of controlled drug-delivery systems [76]. During the synthesis of mesoporous silica nanoparticles, several factors can be individually regulated: the kind and concentration of chemicals used, the reaction temperature, the pH level, and the source of silica-all of which finally govern the physical and chemical properties of these materials [77]. The surface area is about 1000 m2/g, and it has good biocompatibility and chemical and thermal stability. Because the surface area is large, high medication dosage could be incorporated. Besides, the pore volume of the MSNs is modulable and about 1 cm³/g with an orderly arrangement in the mesopore diameters, ranging from 2 to 20 n [78]. Furthermore, modifying the surface of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) through chemical alteration of the silanol groups enables targeted drug delivery to specific locations, enhancing their potential as promising nanocarriers [78]. The outstanding properties of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) have facilitated the development of novel drug delivery systems for treating various diseases [79]. There is limited literature reporting the use of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) against candidiasis. However, all research conducted so far on the issue has shown that MSN added to the nano drug delivery system might be one way of developing the effectiveness of such antifungals as econazole and tebuconazole [80]. This strain thus uptakes the medication more fully, exerting stronger antifungal effects on Candida albicans. In addition, such systems also showed a high degree of biocompatibility, with low cytotoxicity and no skin irritation. In this regard, the usage of rose Bengal as a dye, after encapsulation into mesoporous silica nanoparticles, has been exploited for Candida albicans photodynamic therapy. Such a formulation exhibited high antimicrobial activity of 88.62±3.4% and an antibiofilm effect compared to the free dye upon light irradiation [81]. Although research is limited, there is promise in the potential presented by mesoporous silica nanoparticles as an alternative for candidiasis treatment. Further studies are needed, especially the evaluation of their efficiency against other Candida spp. strains.

Toxicity of nanoparticles used in the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis

It is considered that nanoparticles are harmful because of their unique physicochemical features, resulting in negative health impacts on people (92). Size, shape, surface charge, and other features of nanomaterial exposure influence the toxicity after their delivery to different organs, depending on nanoparticle attributes and physiological parameters of individuals [82]. Nanoparticles are so tiny that they may avoid these biological barriers, enter into the blood circulation system, interact with organs or tissues, and disturb normal biological activities [83]. It can induce oxidative stress, inflammation, genotoxicity, immunological dysregulation, cellular damage, and finally organ damage, especially in the liver, kidneys, reproductive system, and cardiovascular system [84]. Thus, the toxicity of nanoparticles is related to reactive species production, cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and neurotoxicity.

Nanoparticles' toxicity is a concern due to potential long-term health effects, especially inhalation risks. Understanding elimination pathways and non-inhalation routes is crucial for safety in consumer products [85]. Nanoparticles can induce toxicity by interacting with cells, potentially causing adverse health effects. Mitigation strategies like coating, doping, and antioxidants can help reduce nanotoxicity risks in biomedical applications [86].

Studies on the in vivo and in vitro models are mainly done on nanoparticles, which are intended for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Such investigations can enable the determination of distribution and elimination of the nanoparticles from the body, as well as unfavorable immunological reactions they can provoke or cause harm to different organs and tissues.

Taslima T. Lina et al. conducted study on "Intravaginal poly-(D, L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (polyethylene glycol) drug-delivery nanoparticles induce pro-inflammatory responses with Candida albicans infection in a murine model" [87]. The study encompasses both in vitro and in vivo components to investigate the toxicity and biological responses induced by poly-(D, L-lactic-co-glycolic acid)-(polyethylene glycol) (PLGA-PEG) nanoparticles in the presence of Candida albicans [87].

Clinical trials on nanoparticles

There are several nanoparticle-based formulations being developed and tested against VVC, and some preclinical and early clinical trials have not been reported with promising outcomes, indicating the improved antifungal activity with reduced recurrences of the nanoparticles. Some of the challenges in producing nanoparticles are on a consistent and repeatable basis; and long-term regulatory or safety issues when they are used. Outperforming the possible resistance mechanisms of Candida species against nanoparticle-based therapies.

The number of clinical trials of nanoparticles for treating VVC is still small but on the rise. Nanoformulations with different functionalized nanoparticles have been under trial by researchers to enable the improvement of the efficacy and safety of the therapies against VVC. Such nanoparticles are loaded with antifungal drugs like miconazole, fluconazole, and luliconazole, showing very promising results when tested at preclinical and clinical stages.

Miconazole-loaded nanoparticles coated with hyaluronic acid have been shown to offer continuous medication release and an increased concentration at the site of infection in the treatment of VVC. One study with luliconazole-loaded electrospun nanofibers showed a remarkable anticandidal action, so it would show a new potential therapeutic option in treating VVC [88]. The whole thing, though there are some clinical trials and research under development, still more large-scale clinical trials are necessary to establish the nanoparticle-based treatments as safe and effective for treating VVC.

Table 5: List of patent related to the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis

| S. No. | Patent no | Patent title | Grant date | Field of invention | Ref |

| 1 | 6,153,635/USOO6153635A | Methods and kits for treating vulvovaginal candidiasis with miconazole nitrate | NOV 28,2000 | Invention relates to methods for the treatment of Vulvovaginal candidiasis with miconazole nitrate | [89] |

| 2 | US 2006/0165803 A1 | Pharmaceutical compositions of sertaconazole for vaginal use | Jul. 27, 2006 | The invention is related to formulations of sertaconazole for vaginal use in the management of vulvovaginal candidiasis. | [90] |

| 3 | US 7456,207 B2 |

Vaginal pharmaceutical compositions and methods for preparing them |

Nov. 25, 2008 | The invention relates compositions and treatments for bacterial vaginal infections. | [91] |

| 4 | CN103127490B |

Medicinal composition for treating vulvovaginal candidiasis |

Oct 04 2006 | The present invention relates to pharmaceutical art, particularly a kind of pharmaceutical composition for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. | [92] |

| 5 | US 11,197,909 B2 |

Compositions and methods for the treatment of fungal infections |

Dec. 14, 2021 | The disclosure relates to the field of treatment of fungal infections | [93] |

| 6 | EP1700599B1 |

Fulvic acid and its use in the treatment of candida infections |

Oct 08 1999 | This invention relates to fulvic acid and its use in the treatment of candida infections. | [94] |

Patent

Patents are highly important in the development of medical therapies because they inspire innovation by granting temporary exclusivity to the inventor of a particular work. This temporary exclusivity is very important to companies since it offers a financial motive necessary to invest in the prolonged periods required in research and development. The patent protection enables companies to realize their investments through commercialization of innovations without immediate competition. This interaction is crucial for the elaboration of new and better treatments, mainly regarding medical therapies. Table 5 explain some patent related to vulvovaginal candidiasis.

Future perspective

The future outlook on vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) focuses on comprehending the delicate interplay between Candida species, host immune defenses, and local microbial populations to devise successful treatments. Studies emphasize the significance of factors that affect the shift from a harmless state to a pathogenic one, including the immune response, the composition of the microbiota, and the transition of Candida from yeast to hyphal forms. [95]. Research highlights the necessity for better diagnostic methods, evidence-based treatments, and well-informed healthcare providers to tackle the challenges experienced by women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) [96]. New therapeutic and preventive measures are being explored to address the complexities of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), focusing on developing alternative treatments and strategies to tackle issues such as resistant Candida strains and recurrent infections [97]. Moreover, pinpointing previously unidentified risk factors associated with intestinal and vaginal dysbiosis through laboratory diagnostics can offer crucial insights for enhancing VVC management and lowering recurrence rates [98].

Clinical trials with natural products, such as extracts from Ageratinapichinchensis, Calendula officinalis, garlic tablets, and propolis, have already demonstrated therapeutic potential for RVVC. However, most plant extracts that exhibit in vitro biological activity often poorly work in in vivo models. In fact, many active components of these extracts, like flavonoids, tannins, and terpenes, are highly soluble in water but very poorly absorbed. The poor absorption results from their inability to diffuse through cell lipid membranes or a big molecular size that dims their effectiveness [99].

With respect to Candida albicans-caused VVC, future treatment options do seem bright for the purpose of developing nanosystems. Several techniques based on nanocarriers have been investigated for their potential activity against Candida albicans, including lycopene-impregnated mesoporous silica nanoparticles[100], hypericin-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers [101], and farnesol and miconazole-loaded chitosan nanoparticles ([102]. It has been shown that such nanosystems demonstrated enhanced therapeutic efficacy, including strong antifungal action, decreased toxicity in the in vivo models, and prevention of the transition from a yeast to hyphae. Additionally, nanostructured lipid carriers have shown significant reductions in fungal burden, highlighting their potential as an effective strategy for VVC therapy [101].

CONCLUSION

Vulvovaginal candidiasis remains one of the most common and persistent opportunistic infections, whose management is already being complicated by problems related to biofilm formation, antifungal resistance, and recurrence. Classic treatments for the disease, though often successful in uncomplicated VVC, are inadequate in treating recurrent or complicated VVC because of these emerging issues. There is, thus, an urgent need to explore new strategies with which to improve treatment outcomes and decrease recurrence rates with rising incidence rates of antifungal resistance. Nanotechnology potentially represents a very promising strategy to improve treatment against VVC, wherein nano-systems can be employed for targeted drug delivery and evading various obstacles of traditional therapies. Clinical trials assessed the effectiveness of nanoparticles in enhancing the efficacy of treatments, but their toxicity should be well considered. Nano-based therapies may further represent a perspective opening up new horizons in the management of VVC due to enhanced and more personalized treatments. Further research and development will be required to realize fully this area of nanotechnology for the benefit of the patient.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude towards the leadership and management of JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research (JSSAHER), Mysuru, India for providing all the obligatory facilities for completion of this comprehensive review.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, A. S., and D. D. G.; Methodology, D. D. G., S. P. and M. A.; Software, M. A. D. P, and S. P.; Validation and formal analysis, A. S.; Investigation, D. D. G., S. P.; Resources, A. S., M. A., and D. P.; Data curation, D. D. G., S. P and M. A.; Writing-original draft preparation D. D. G; Writing-review and editing, A. S.,S. P., D. P., and M. A.; Visualization and supervision, A. S.; Project administration, A. S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests

REFERENCES

Teixeira AD, Quaresma ADV, Branquinho RT, Santos SLEN, Magalhaes JTD, Silva FHRD, Marques MBDF, Moura SALD, Barboza APM, Araujo MGDF, Silva GRD. Miconazole-loaded nanoparticles coated with hyaluronic acid to treat vulvovaginal candidiasis. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2023 Sep 1;188:106508. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2023.106508.

Felix TC, De Brito Roder DV, Dos Santos Pedroso R. Alternative and complementary therapies for vulvovaginal candidiasis. Folia Microbiol. 2019;64(2):133-41. doi: 10.1007/s12223-018-0652-x, PMID 30269301.

Otoo Annan E, Senoo Dogbey VE. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: assessing the relationship between feminine/vaginal washes and other factors among Ghanaian women. BMC Public Health. 2024 Jan 5;24(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-17668-x, PMID 38183091.

Blostein F, Levin Sparenberg E, Wagner J, Foxman B. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Ann Epidemiol. 2017 Sep;27(9):575-582.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.08.010, PMID 28927765.

Zahra Javanmard, Maryam Pourhajibagher, Abbas Bahador. Advancing anti-biofilm strategies: innovations to combat biofilm-related challenges and enhance efficacy. Journal of Basic Microbiology. 2024 Oct;64(12):e2400271. doi: 10.1002/jobm.202400271.

Bhattacharya S, Sae Tia S, Fries BC. Candidiasis and mechanisms of antifungal resistance. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Jun 9;9(6):312. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060312, PMID 32526921.

Sarpong AK, Odoi H, Boakye YD, Boamah VE, Agyare C. Resistant Candida albicans implicated in recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) among women in a tertiary healthcare facility in Kumasi, Ghana. BMC Womens Health. 2024 Jul 19;24(1):412. doi: 10.1186/s12905-024-03217-6, PMID 39030542.

Le PH, Linklater DP, Medina AA, Mac Laughlin S, Crawford RJ, Ivanova EP. Impact of multiscale surface topography characteristics on Candida albicans biofilm formation: from cell repellence to fungicidal activity. Acta Biomater. 2024 Mar 15;177:20-36. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2024.02.006, PMID 38342192.

Alvarez L, Kumaran KS, Nitha B, Sivasubramani K. Evaluation of biofilm formation and antimicrobial susceptibility (drug resistance) of Candida albicans isolates. Braz J Microbiol. 2025 Mar 1;56(1):353-64. doi: 10.1007/s42770-024-01558-w, PMID 39500825.

Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015 Jun 5;64(3):1-137. PMID 26042815.

Nyirjesy P, Brookhart C, Lazenby G, Schwebke J, Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: a review of the evidence for the 2021 centers for disease control and prevention of sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2022 Apr 13;74Suppl 2:S162-8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab1057, PMID 35416967.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/index.html. [Last accessed on 12 Mar 2025].

Matsubara VH, Wang Y, Bandara HM, Mayer MP, Samaranayake LP. Probiotic lactobacilli inhibit early stages of Candida albicans biofilm development by reducing their growth cell adhesion and filamentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016 Jul;100(14):6415-26. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7527-3, PMID 27087525.

Stabile G, Gentile RM, Carlucci S, Restaino S, De Seta F. A new therapy for uncomplicated vulvovaginal candidiasis and its impact on vaginal flora. Healthcare (Basel). 2021 Nov 16;9(11):1555. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9111555, PMID 34828601.

Marrazzo JM, Dombrowski JC, Wierzbicki MR, Perlowski C, Pontius A, Dithmer D. Safety and efficacy of a novel vaginal anti-infective, TOL-463, in the treatment of bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis: a randomized single blind phase 2, controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Feb 15;68(5):803-9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy554, PMID 30184181.

Fernandes Costa A, Evangelista Araujo D, Santos Cabral M, Teles Brito I, Borges De Menezes Leite L, Pereira M. Development characterization and in vitro in vivo evaluation of polymeric nanoparticles containing miconazole and farnesol for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Med Mycol. 2019 Jan 1;57(1):52-62. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx155, PMID 29361177.

Phillips AJ. Treatment of non-albicans Candida vaginitis with amphotericin B vaginal suppositories. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jun 1;192(6):2009-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.03.034, PMID 15970877.

Farr A, Effendy I, Frey Tirri B, Hof H, Mayser P, Petricevic L. Guideline: Vulvovaginal candidosis (AWMF 015/072, level S2k). Mycoses. 2021 Jun;64(6):583-602. doi: 10.1111/myc.13248, PMID 33529414.

Donders G, Sziller IO, Paavonen J, Hay P, De Seta F, Bohbot JM. Management of recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis: narrative review of the literature and European expert panel opinion. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:934353. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.934353, PMID 36159646.

Anne Edwards, Riina Rautemaa Richardson, Caroline Owen, Bavithra Nathan. British association for sexual health and HIV national guideline for the management of vulvovaginal candidiasis (2019). Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31(12):1124-44. doi: 10.1177/0956462420943034, PMID 32883171.

AIDS Info A. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV. In: United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. Available from: https://www.pededose[ch]/de/file/show?filename=Opportunistic_Infections_Adult_Adolescents_online_202011. [Last accessed on 12 Mar 2025].

Warrilow AG, Hull CM, Parker JE, Garvey EP, Hoekstra WJ, Moore WR. The clinical candidate VT-1161 is a highly potent inhibitor of Candida albicans CYP51 but fails to bind the human enzyme. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014 Dec;58(12):7121-7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03707-14, PMID 25224009.

Brand SR, Sobel JD, Nyirjesy P, Ghannoum MA, Schotzinger RJ, Degenhardt TP. A randomized phase 2 study of VT-1161 for the treatment of acute vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Oct 5;73(7):e1518-24. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1204, PMID 32818963.

Martens MG, Maximos B, Degenhardt T, Person K, Curelop S, Ghannoum M. Phase 3 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of oteseconazole in the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis and acute vulvovaginal candidiasis infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Dec;227(6):880.e1-880.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.07.023, PMID 35863457.

Denning DW, Kneale M, Sobel JD, Rautemaa Richardson R. Global burden of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 Nov;18(11):e339-47. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30103-8, PMID 30078662.

Lirio J, Giraldo PC, Amaral RL, Sarmento AC, Costa AP, Gonçalves AK. Antifungal (oral and vaginal) therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019 May 22;9(5):e027489. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027489, PMID 31122991.

Philips N, Burchill D, O Donoghue D, Keller T, Gonzalez S. Identification of benzene metabolites in dermal fibroblasts as nonphenolic: regulation of cell viability, apoptosis lipid peroxidation and expression of matrix metalloproteinase 1 and elastin by benzene metabolites. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;17(3):147-52. doi: 10.1159/000077242, PMID 15087594.

Grant LM, Orenstein R. Treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis with ibrexafungerp. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2022 Sep 3;10:23247096221123144. doi: 10.1177/23247096221123144, PMID 36059275.

Schwebke JR, Sobel R, Gersten JK, Sussman SA, Lederman SN, Jacobs MA. Ibrexafungerp versus placebo for vulvovaginal candidiasis treatment: a phase 3, randomized controlled superiority trial (VANISH 303). Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(11):1979-85. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab750, PMID 34467969.

Neal CM, Martens MG. Clinical challenges in diagnosis and treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Sage Open Med. 2022;10:20503121221115201. doi: 10.1177/20503121221115201, PMID 36105548.

Lauryn Nsenga, Felix Bongomin. Recurrent candida vulvovaginitis. Venereology. 2022 May;1(1):114-23. doi: 10.3390/venereology1010008.

Neda Taghinejadi, Monique I Andersson, Emily Lord. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis with Candida glabrata a management conundrum. 2022 Sep;33(10):939-42. doi: 10.1177/09564624221118739.

Re AC, Martins JF, Cunha Filho M, Gelfuso GM, Aires CP, Gratieri T. New perspectives on the topical management of recurrent candidiasis. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2021 Aug 1;11(4):1568-85. doi: 10.1007/s13346-021-00901-0, PMID 33469892.

Kaur S, Kaur S. Recent advances in vaginal delivery for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2021;14(3):281-91. doi: 10.2174/1573405616666200621200047, PMID 32564767.

Sato MR, Oshiro Junior JA, Rodero CF, Boni FI, Araujo VH, Bauab TM. Photodynamic therapy mediated hypericin-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers against vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Mycol Med. 2022 Nov;32(4):101296. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2022.101296, PMID 35660541.

Chindamo G, Sapino S, Peira E, Chirio D, Gallarate M. Recent advances in nanosystems and strategies for vaginal delivery of antimicrobials. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021 Jan 26;11(2):311. doi: 10.3390/nano11020311, PMID 33530510.

Carvalho GC, Marena GD, Leonardi GR, Sabio RM, Correa I, Chorilli M. Lycopene mesoporous silica nanoparticles and their association: a possible alternative against vulvovaginal candidiasis? Molecules. 2022;27(23):8558. doi: 10.3390/molecules27238558, PMID 36500650.

Yang M, Cao Y, Zhang Z, Guo J, Hu C, Wang Z. Low intensity ultrasound-mediated drug-loaded nanoparticles intravaginal drug delivery: an effective synergistic therapy scheme for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Nanobiotechnology. BioMed Central. 2023;21(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s12951-023-01800-x, PMID 36782198.

Dos Santos Ramos MA, Da Silva PB, Sposito L, De Toledo LG, Bonifacio BV, Rodero CF. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems for control of microbial biofilms: a review. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:1179-213. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S146195, PMID 29520143.

Prashant V, Kamat. Photophysical photochemical and photocatalytic aspects of metal nanoparticles. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2002;106(32):7729-44. doi: 10.1021/jp0209289.

Weir E, Lawlor A, Whelan A, Regan F. The use of nanoparticles in anti-microbial materials and their characterization. Analyst. 2008 Jul;133(7):835-45. doi: 10.1039/b715532h, PMID 18575632.

Tokeer Ahmad, Irshad A Wani, Irfan H Lone, Aparna Ganguly. Antifungal activity of gold nanoparticles prepared by solvothermal method. Materials Research Bulletin. 2013;48(1):12-20. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2012.09.069.

Kumar M, Varshney L, Francis S. Radiolytic formation of Ag clusters in aqueous polyvinyl alcohol solution and hydrogel matrix. Radiation Physics and Chemistry. 2005 May 1;73(1):21-7. doi: 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2004.06.006.

Austin LA, Mackey MA, Dreaden EC, El Sayed MA. The optical photothermal and facile surface chemical properties of gold and silver nanoparticles in biodiagnostics therapy and drug delivery. Arch Toxicol. 2014 Jul;88(7):1391-417. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1245-3, PMID 24894431.

Da Silva PB, Machado RT, Pironi AM, Alves RC, De Araujo PR, Dragalzew AC. Recent advances in the use of metallic nanoparticles with antitumoral action review. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26(12):2108-46. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180214102918, PMID 29446728.

Rahimi H, Roudbarmohammadi S, Delavari H HH, Roudbary M. Antifungal effects of indolicidin conjugated gold nanoparticles against fluconazole-resistant strains of Candida albicans isolated from patients with burn infection. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019 Jul 17;14:5323-38. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S207527, PMID 31409990.

Baygar T, Sarac N, Ugur A, Karaca IR. Antimicrobial characteristics and biocompatibility of the surgical sutures coated with biosynthesized silver nanoparticles. Bioorg Chem. 2019 May;86:254-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.12.034, PMID 30716622.

Alimehr S, Shekari Ebrahim Abad H, Shahverdi A, Hashemi J, Zomorodian K, Moazeni M. Comparison of difference between fluconazole and silver nanoparticles in antimicrobial effect on fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis. 2015;3(2):e21481. doi: 10.5812/pedinfect.21481.

Aftab Ahmad, Yun Wei, Fatima Syed, Kamran Tahir, Raheela Taj, Arif Ullah Khan. Amphotericin B-conjugated biogenic silver nanoparticles as an innovative strategy for fungal infections. Microb Pathog. 2016 Oct:99:271-81. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.08.031.

Sirelkhatim A, Mahmud S, Seeni A, Kaus NH, Ann LC, Bakhori SK. Review on zinc oxide nanoparticles: antibacterial activity and toxicity mechanism. Nanomicro Lett. 2015;7(3):219-42. doi: 10.1007/s40820-015-0040-x, PMID 30464967.

Lewis MA, Williams DW. Diagnosis and management of oral candidosis. Br Dent J. 2017 Nov 10;223(9):675-81. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.886, PMID 29123282.

Shah CP, McKey J, Spirn MJ, Maguire J. Ocular candidiasis: a review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008 Apr;92(4):466-8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.133405, PMID 18369061.

Hajjar TH, Jebali A, Hekmati Moghaddam S. The inhibition of Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinase by triangular gold nanoparticles. Nanomed J. 2015;2(1):54-9. doi: 10.7508/NMJ.2015.01.006.

Allen TM, Cullis PR. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013 Jan;65(1):36-48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037, PMID 23036225.

Klaus Strebhardt, Axel Ullrich. Paul ehrlichs magic bullet concept: 100 y of progress. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008 Jun;8(6):473-80. doi: 10.1038/nrc2394.

Deshpande PP, Biswas S, Torchilin VP. Current trends in the use of liposomes for tumor targeting. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2013 Sep;8(9):1509-28. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.118, PMID 23914966.

Lopez Berestein G, Hopfer RL, Mehta R, Mehta K, Hersh EM, Juliano RL. Liposome-encapsulated amphotericin B for treatment of disseminated candidiasis in neutropenic mice. J Infect Dis. 1984 Aug;150(2):278-83. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.2.278, PMID 6470530.

Pardeshi C, Rajput P, Belgamwar V, Tekade A, Patil G, Chaudhary K. Solid lipid-based nanocarriers: an overview. Acta Pharm. 2012 Dec;62(4):433-72. doi: 10.2478/v10007-012-0040-z, PMID 23333884.

Doktorovova S, Souto EB, Silva AM. Nanotoxicology applied to solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers a systematic review of in vitro data. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2014 May;87(1):1-18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.02.005, PMID 24530885.

Wong HL, Bendayan R, Rauth AM, Li Y, Wu XY. Chemotherapy with anticancer drugs encapsulated in solid lipid nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007 Jul 10;59(6):491-504. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.008, PMID 17532091.

Iqbal MA, Md S, Sahni JK, Baboota S, Dang S, Ali J. Nanostructured lipid carriers system: recent advances in drug delivery. J Drug Target. 2012 Dec;20(10):813-30. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2012.716845, PMID 22931500.

Seh Hyon Song, Kyung Min Lee, Jong Boo Kang, Sang Gon Lee, Myung Joo Kang, Young Wook Choi. Improved skin delivery of voriconazole with a nanostructured lipid carrier-based hydrogel formulation. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2014;62(8):793-8. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c14-00202.

Tian B, Yan Q, Wang J, Ding C, Sai S. Enhanced antifungal activity of voriconazole-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers against Candida albicans with a dimorphic switching model. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017 Sep 26;12:7131-41. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S145695.

Gordillo Galeano A, Mora Huertas CE. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers: a review emphasizing on particle structure and drug release. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2018 Dec;133:285-308. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.10.017, PMID 30463794.

Huynh NT, Passirani C, Saulnier P, Benoit JP. Lipid nanocapsules: a new platform for nanomedicine. Int J Pharm. 2009 Sep 11;379(2):201-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.04.026, PMID 19409468.

Quintanar Guerrero D, Allemann E, Doelker E, Fessi H. Preparation and characterization of nanocapsules from preformed polymers by a new process based on emulsification diffusion technique. Pharm Res. 1998;15(7):1056-62. doi: 10.1023/a:1011934328471, PMID 9688060.

Santos SS, Lorenzoni A, Ferreira LM, Mattiazzi J, Adams AI, Denardi LB. Clotrimazole-loaded Eudragit® RS100 nanocapsules: preparation, characterization and in vitro evaluation of antifungal activity against Candida species. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2013 Apr 1;33(3):1389-94. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.12.040, PMID 23827586.

Domingues Bianchin M, Borowicz SM, Da Rosa Monte Machado G, Pippi B, Staniscuaski Guterres S, Raffin Pohlmann A, Meneghello Fuentefria A, Clemes Kulkamp Guerreiro I. Lipid core nanoparticles as a broad strategy to reverse fluconazole resistance in multiple Candida species. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019 Mar 1;175:523–9. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.12.011.

Giordani B, Basnet P, Mishchenko E, Luppi B, Skalko Basnet N. Utilizing liposomal quercetin and gallic acid in localized treatment of vaginal candida infections. Pharmaceutics. 2019 Dec 20;12(1):9. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12010009, PMID 31861805.

Dos Santos MK, Kreutz T, Danielli LJ, De Marchi JG, Pippi B, Koester LS. A chitosan hydrogel thickened nanoemulsion containing Pelargonium graveolens essential oil for treatment of vaginal candidiasis. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020 Apr 1;56:101527. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.101527.

Carbone C, Fuochi V, Zielinska A, Musumeci T, Souto EB, Bonaccorso A. Dual drugs delivery in solid lipid nanoparticles for the treatment of Candida albicans mycosis. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2020 Feb;186:110705. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110705, PMID 31830707.

El Sheridy NA, Ramadan AA, Eid AA, El Khordagui LK. Itraconazole lipid nanocapsules gel for dermatological applications: in vitro characteristics and treatment of induced cutaneous candidiasis. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019 Sep 1;181:623-31. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.05.057, PMID 31202972.

Kamaly N, Xiao Z, Valencia PM, Radovic Moreno AF, Farokhzad OC. Targeted polymeric therapeutic nanoparticles: design, development and clinical translation. Chem Soc Rev. 2012 Apr 7;41(7):2971-3010. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15344k, PMID 22388185.

Amaral AC, Saavedra PH, Oliveira Souza AC, De Melo MT, Tedesco AC, Morais PC. Miconazole-loaded chitosan-based nanoparticles for local treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis fungal infections. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019 Feb 1;174:409-15. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.11.048, PMID 30481701.

Adelaide Fernandes Costa, Deize Evangelista Araujo, Mirlane Santos Cabral. Development characterization and in vitro in vivo evaluation of polymeric nanoparticles containing miconazole and farnesol for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Med Mycol. 2019 Jan 1;57(1):52-62. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx155.

Lombardo D, Kiselev MA, Caccamo MT. Smart nanoparticles for drug delivery application: development of versatile nanocarrier platforms in biotechnology and nanomedicine. J Nanomater. 2019;2019(1):1-26. doi: 10.1155/2019/3702518.

Sabio RM, Meneguin AB, Ribeiro TC, Silva RR, Chorilli M. New insights towards mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a technological platform for chemotherapeutic drugs delivery. Int J Pharm. 2019 Jun 10;564:379-409. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.04.067, PMID 31028801.

Manzano M, Vallet Regi M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery. Adv Funct Materials. 2020;30(2):1902634. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201902634.

Mendiratta S, Hussein M, Nasser HA, Ali AA. Multidisciplinary role of mesoporous silica nanoparticles in brain regeneration and cancers: from crossing the blood–brain barrier to treatment. Part Part Syst Char. 2019;36(9):1900195. doi: 10.1002/ppsc.201900195.

Mas N, Galiana I, Hurtado S, Mondragon L, Bernardos A, Sancenon F. Enhanced antifungal efficacy of tebuconazole using gated pH-driven mesoporous nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014 May 23;9(1):2597-606. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S59654, PMID 24920897.

Parasuraman P, Antony A, SBS, Sharan A, Syed A, Ahmed M. Antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation of fungal biofilm using amino functionalized mesoporous silica rose bengal nanoconjugate against Candida albicans. Sci Afr. 2018 Nov 1;1:e00007. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2018.e00007.

Bain A, Vasdev N, Tekade M, Mishra DK, Sengupta P, Tekade RK. Toxicity of nanomaterials. In: Public health and toxicology issues drug research, Vol 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2024. p. 679-706. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-15842-1.00023-5.

Zoroddu MA, Medici S, Ledda A, Nurchi VM, Lachowicz JI, Peana M. Toxicity of nanoparticles. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21(33):3837-53. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140601162314, PMID 25306903.

Muhammad Umar Ijaz, Ali Akbar, Asma Ashraf. Toxicity of nanoparticles in biological systems. Materials Research Foundations. 2024;161:245-66. doi: 10.21741/9781644902998-9.

Sharifi S, Behzadi S, Laurent S, Forrest ML, Stroeve P, Mahmoudi M. Toxicity of nanomaterials. Chem Soc Rev. 2012 Feb 27;41(6):2323-43. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15188f, PMID 22170510.

Sharma N, Kurmi BD, Singh D, Mehan S, Khanna K, Karwasra R. Nanoparticles toxicity: an overview of its mechanism and plausible mitigation strategies. J Drug Target. 2024 May 27;32(5):457-69. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2024.2316785, PMID 38328920.