Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 107-121Review Article

INTEGRATIVE SYSTEMS BIOLOGY AND MULTI-OMICS APPROACHES IN ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE: BRIDGING BIOMARKERS, NEUROINFLAMMATION, AND PRECISION MEDICINE

JITHIN MATHEW1*, ANSON SUNNY MAROKY2, SIVARANJINI SINDURAJ3, ANCHU CHANDRABABU4

1Nitte (Deemed to be University), NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Department of Pharmacology, Paneer, Mangalore, Karnataka, India. 2Departments of Pharmacology, Devaki Amma Memorial College of Pharmacy, Malappuram, Affiliated to Kerala University of Health Sciences, Kerala, India. 3Department of Pharmacology, Dr. Moopens College of Pharmacy, Wayanad, Kerala, India. 4Department of Pharmacy Practice, College of Pharmacy, Kannur Medical College, Anjarakandy, Kannur, India

*Corresponding author: Jithin Mathew; *Email: jithinmathew051@gmail.com

Received: 05 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 15 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a gradual decline in cognitive function, driven by synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss, particularly in the hippocampus a region critical for memory and learning. A hallmark of AD pathogenesis is the aggregation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides into toxic oligomers, which initiate a cascade of events leading to amyloid plaque formation, activation of reactive microglia and astrocytes and subsequent neuronal damage. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress plays pivotal roles in AD progression, with the interplay between these processes exacerbating the pathological features of the disease. Pro-inflammatory signaling pathways activated by reactive immune cells and the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) disrupt cellular homeostasis, further accelerating neurodegeneration. This review delves into the intricate mechanisms linking Aβ pathology with inflammatory and oxidative stress responses and highlights how multi-omics and neuroimaging enable precision medicine through molecular and structural brain correlation. Recent advances in understanding the molecular pathways have unveiled potential biomarkers that hold promise for improving diagnostic precision and monitoring disease progression. Furthermore, this review highlights novel therapeutic strategies identified through systems biology approaches, emphasizing their potential to target the multifaceted nature of AD pathophysiology. By exploring the nexus of amyloid pathology, neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, this work aims to provide a comprehensive framework for developing targeted interventions that may mitigate the burden of this devastating disease. This review critically evaluates network-based analyses and case studies in genomics, proteomics and metabolomics that have identified candidate biomarkers and therapeutic targets in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Amyloid-beta, Neuroinflammation, Oxidative stress, Biomarkers, Neurodegeneration, Therapeutic strategies

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54564 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects middle-aged and elderly individuals, leading to cognitive impairment and memory loss. The pathogenesis of AD is multifaceted involving genetic predisposition, environmental influences and lifestyle factors, with evidence suggesting that an active lifestyle may mitigate disease progression. At the molecular level, AD is marked by the accumulation of Aβ plaques and the intracellular aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, contributing to synaptic dysfunction, neuronal loss, and neuroinflammation [1]. Recent critiques of the classical amyloid cascade hypothesis, which posits Aβ as the central driver of AD have highlighted a need for nuanced perspectives. Keep and Hardy (2023) argue that the correlation between Aβ burden and disease severity is weaker than previously assumed, suggesting that downstream pathological events may play a more significant role [2]. Similarly, Volloch and Rits-Volloch (2023) suggest that Aβ might actually help protect the body in some situations, viewing it as a reaction instead of the main cause of neurodegeneration [3]. Oxidative stress plays a central role in AD pathology, driven by an imbalance between ROS, reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and endogenous antioxidant defenses [4]. This disruption leads to oxidative damage including lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and DNA fragmentation which collectively exacerbate neuronal dysfunction [5]. Furthermore, Aβ peptides promote oxidative stress by activating NADPH oxidase, further amplifying neuronal toxicity and synaptic impairment [6]. Notably synaptic dysfunction and loss have been shown to correlate more strongly with cognitive decline than neuronal death itself, highlighting the importance of targeting early pathological changes in AD management [7]. Chronic neuroinflammation has emerged as a key factor in AD progression, distinguishing it from acute inflammatory responses that serve a protective function. Although the central nervous system (CNS) was traditionally considered immune-privileged due to the presence of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and a limited population of resident immune cells, recent evidence suggests otherwise. The BBB is a dynamic structure and its permeability is influenced by aging, trauma, infections and neurodegenerative diseases [8]. Microglia and astrocytes along with infiltrating peripheral immune cells, produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, prostaglandins and reactive species, perpetuating a cycle of chronic inflammation. The activation of microglia in response to Aβ accumulation results in the release of inflammatory mediators further accelerating neuronal damage and synaptic dysfunction [9]. Because oxidative stress, inflammation and nerve damage are all connected, it's important to use treatment methods that address several parts of AD to effectively change its course [10].

The complexity of AD pathogenesis necessitates systems biology (SB) approach to unravel the intricate molecular interactions involved in disease progression [11]. SB integrates network-based analyses with omics-driven methodologies to identify key biomarkers and molecular pathways associated with AD, paving the way for biomarker-guided therapeutic strategies [12]. Notably, biometals such as copper, zinc and iron have been implicated in Aβ aggregation and oxidative damage, underscoring the need for targeted interventions that restore metal homeostasis [13]. Advances in precision medicine, combined with SB-based biomarker discovery, hold promise for early disease detection and the development of personalized therapeutic strategies [14]. This review explores the molecular underpinnings of AD, emphasizing the role of oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and metal dyshomeostasis in disease progression [15]. Additionally, it highlights the application of SB in understanding AD pathology and its potential in guiding future therapeutic innovations [16]. To navigate these interconnected pathological mechanisms, this review adopts a SB approach integrating genomics, proteomics, metabolomics and neuroimaging data to form a unified framework for understanding AD. SB enables network-based analyses to identify critical molecular hubs, uncover novel biomarkers, and guide therapeutic development [17, 18].

This review looks into the complicated biology of AD, focusing on important issues like the buildup of amyloid, clumping of tau protein, cell damage from oxidation and ongoing inflammation in the brain. It presents updated perspectives on conventional hypotheses particularly those concerning Aβ and integrates insights from genomics, proteomics, metabolomics and neuroimaging to construct a systems-level view of the disease. By incorporating network-based analyses and biomarker discovery, the review underscores emerging molecular targets and supports the advancement of personalized, biomarker-driven therapeutic strategies aimed at altering disease progression.

Review: search methodology

A systematic literature review was conducted using databases such as PubMed, science direct, Springer link, Scopus, Google scholar, Wiley online library, and consortia including ADNI and AMP-AD. The search focused on publications from 2010 to 2025, with particular emphasis on recent findings from 2021 onward. Keywords included AD, Aβ, tau protein, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, biomarkers, SB, multi-omics, neuroimaging and related terms. Studies were chosen because they were important for understanding AD, finding biomarkers, and using combined methods that includes genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and imaging. Only peer-reviewed articles involving human, animal, or In vitro models were included while non-peer-reviewed materials, unrelated neurological conditions and outdated research lacking translational relevance were excluded. This approach ensured the inclusion of high-quality evidence-based studies to support a systems-level understanding of AD.

Neuroinflammatory and oxidative mechanisms in AD: an integrative amyloid-tau perspective

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the primary cause of dementia in older adults. It is marked by a gradual deterioration in cognitive abilities, memory impairment and behavioral changes eventually resulting in complete reliance on caregivers [19]. The development of AD is multifactorial, involving a combination of genetic predispositions, environmental factors and internal biological mechanisms [20]. These elements interact intricately, contributing to a progression of the disease that varies from person to person [21].

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of AD, but a unified theory remains elusive, likely due to the multifactorial and complex nature of the disorder [22]. AD is generally classified into two main types: familial alzheimer’s disease (FAD) and sporadic alzheimer’s disease (SAD). FAD accounts for only 1-5% of all AD cases, whereas SAD represents over 95% of cases [23]. In familial cases, individuals with mutations in certain genes have a 50% chance of passing on the condition to their offspring. FAD follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is typically associated with mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, as well as the presenilin 1 (PS1) and presenilin 2 (PS2) genes. This form of AD often manifests between the ages of 30 and 65 and tends to progress rapidly. On the other hand, SAD commonly referred to as late-onset AD, typically appears after the age of 65 and is influenced by a combination of genetic predispositions, environmental factors and comorbid conditions [24]. Non-genetic factors such as lifestyle choices, psychosocial influences, and environmental exposures also contribute to the risk of developing AD potentially by altering biological pathways and interacting with genetic susceptibility [25]. Moreover, different subtypes of AD including typical and atypical forms, may present with a variety of clinical symptoms further complicating diagnosis and treatment [26]. The high failure rate of clinical trials in AD may be attributed to the coexistence of multiple theories regarding its pathogenesis, which complicates the validation of potential therapeutic targets [27]. These complexities will be explored in greater detail in the following sections [28].

The amyloid cascade hypothesis and its role in AD

In 1984, researchers Glenner and Wong made a landmark discovery by identifying Aβ in the cortex of AD patients' brains. This pivotal finding provided the foundation for the amyloid cascade hypothesis, which proposes that the accumulation of Aβ plays a central role in the pathogenesis of both idiopathic and non-idiopathic AD (IAD and NIAD) [29]. The hypothesis suggests that Aβ, a key proteolytic fragment derived from the aAPP, initiates a pathological cascade that leads to neurodegeneration and cognitive decline, hallmark features of AD [30]. APP, a type I membrane protein is widely expressed across various tissues, with a predominant presence in neurons, vascular cells and platelets [31]. This large precursor molecule is cleaved by secretases to generate Aβ, which aggregate and forms plaques in the brain. APP undergoes sequential cleavage by β-secretase β-APP-cleaving enzyme 1(BACE1) and γ-secretase, producing the Aβ peptides Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 [14]. These peptides, particularly Aβ42, have been found to aggregate more readily and form toxic oligomers that contribute to the neurodegenerative process in AD. The amyloid cascade hypothesis asserts that the accumulation of Aβ plaques disrupts synaptic function induces neuronal death, and ultimately drives the cognitive decline seen in AD patients [32].

The formation of Aβ plaques begins with the cleavage of APP by beta-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 which generates a 99-amino acid fragment known as C99. This fragment is then further cleaved by γ-secretase to produce Aβ peptides. While Aβ monomers are typically soluble and non-toxic in small quantities, their neurotoxic potential is dramatically enhanced when they undergo oligomerization. The oligomeric forms of Aβ, particularly Aβ42, have a strong tendency to aggregate and deposit in critical regions of the brain, including the hippocampus, olfactory cortex and various areas of the cerebral cortex [33]. This aggregation of Aβ peptides disrupts normal synaptic function impairing neuronal communication and plasticity. Over time, the buildup of amyloid plaques induces a cascade of pathological events, including oxidative stress, inflammation and neuroinflammation, which further exacerbate neuronal damage and contribute to the progressive nature of AD [29]. The presence of these plaques, alongside other pathological hallmarks such as tau tangles, has made Aβ deposition a crucial biomarker for diagnosing AD, reinforcing the idea that the accumulation of Aβ is a central event in the disease's pathogenesis [34].

The relationship between APP processing and the amyloidogenic pathway in AD has been further elucidated through genetic studies. Mutations in the APP gene, as well as duplications or triplications of the APP locus, have been linked to an increased production of Aβ, particularly Aβ42 [35]. These genetic alterations lead to an imbalance in the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, which is thought to be a critical factor in the formation of amyloid plaques and the progression of cognitive decline [36]. Notably, early-onset al. zheimer's disease (EOAD) is strongly associated with such mutations, where the accumulation of Aβ42 is accelerated, leading to the earlier onset of clinical symptoms [37]. The higher amount of Aβ42 compared to Aβ40 in these people is believed to help create more harmful amyloid clumps, which adds to nerve damage and cell death [38]. These genetic findings have reinforced the idea that Aβ accumulation is not just a consequence of aging but can be directly driven by genetic mutations, providing a more mechanistic understanding of AD pathogenesis [39].

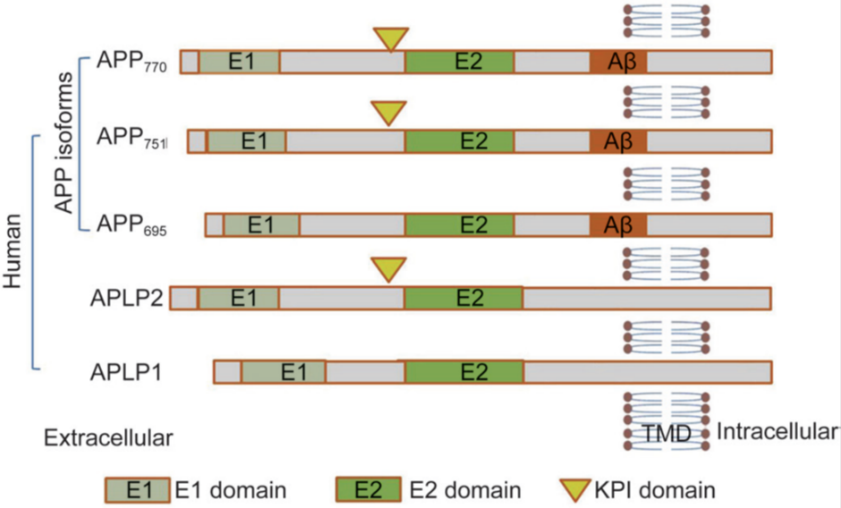

APP itself is a transmembrane protein that plays an important role in neuronal function, particularly in synaptic formation and repair, iron export and anterograde transport [40]. Structurally, APP consists of a large extracellular glycosylated N-terminus, a single transmembrane domain, and a shorter cytoplasmic C-terminus [41]. It belongs to a gene family that also includes amyloid precursor-like protein 1 (APLP1) and amyloid precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2), two related proteins that share some functional similarities with APP. Under normal conditions, APP can be processed through two distinct pathways: the amyloidogenic pathway, which leads to the generation of Aβ peptides, and the non-amyloidogenic pathway, which avoids Aβ production. In the amyloidogenic pathway, APP is first cleaved by β-secretase, generating a membrane-bound C-terminal fragment (C99) that is then further cleaved by γ-secretase to release Aβ peptides [42]. In contrast, the non-amyloidogenic pathway involves cleavage by α-secretase, which releases a soluble fragment (sAPPα) and leaves behind a C-terminal fragment (C83). This non-amyloidogenic pathway is thought to be neuroprotective, as it prevents the formation of Aβ peptides [43]. Importantly, the activity of α-secretase increases with neuronal activity and when muscarinic acetylcholine receptors are activated, indicating that the activity of synapses can affect the balance between the pathways that produce amyloid and those that do not [44]. Disruptions in this balance, particularly an increase in the amyloidogenic pathway, are thought to be a key feature of AD, as they lead to excessive Aβ production and accumulation [45]. This understanding has implications for therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating APP processing and reducing Aβ generation in AD [37].

As research into AD continues to expand, the amyloid cascade hypothesis remains a central framework for understanding the disease's pathophysiology. The role of Aβ in the initiation and progression of AD has been reinforced by genetic, biochemical and neuropathological studies, which have provided substantial evidence for the amyloid hypothesis [46]. However, there is still much to learn about the precise mechanisms through which Aβ induces neuronal damage and cognitive decline. For instance, while Aβ oligomers are known to be toxic, the exact pathways through which they impair synaptic function and promote neurodegeneration are not fully understood [47, 48] moreover, while genetic mutations that increase Aβ production and aggregation have provided insight into AD pathogenesis, the role of other factors, such as tau tangles, neuroinflammation and vascular dysfunction, is also critical to understanding the full scope of AD pathology [49]. The amyloid cascade hypothesis has led to the development of several therapeutic strategies aimed at reducing Aβ accumulation, including the use of anti-amyloid antibodies, γ-secretase inhibitors, and BACE1 inhibitors [50]. These therapies have shown promise in preclinical models, but their efficacy in clinical trials has been mixed, highlighting the complexity of AD and the need for more targeted and effective treatments. Despite these challenges, the continued exploration of Aβ and its role in AD will likely yield valuable insights into the disease's mechanisms and contribute to the development of more effective therapies for AD [51]. Recent studies have cast doubt on the significance of amyloid accumulation, demonstrating tenuous correlations between plaque levels and cognitive impairments, along with the consistent failure of amyloid-targeting drugs in late-stage trials. Kepp et al. (2023) emphasize the significance of examining the mechanisms by which the body eliminates Aβ and the protective strategies it employs, particularly in instances where patients exhibit substantial Aβ accumulation yet maintain cognitive clarity. The findings suggest that an overly reductionist emphasis on amyloid may obscure the complex nature of AD, highlighting the necessity for systems-level models that incorporate genetic, immunological and metabolic networks to comprehend disease heterogeneity and inform treatment development [52].

For many years, the amyloid cascade hypothesis has been the central theory shaping AD research. According to this model, the pathological accumulation of Aβ peptides sets off a cascade of damaging processes, including the abnormal phosphorylation of tau proteins, impairment of synaptic function, and ultimately neuronal loss. However, mounting evidence has challenged the straightforward and linear nature of this hypothesis. Kametani and Hasegawa (2018) found that the amount of amyloid plaques in the brain doesn't always match how much cognitive decline or brain damage a person has experienced. Autopsy findings often show that individuals without cognitive symptoms during their lifetime still exhibit significant amyloid buildup [53]. This paradox is further reinforced by neuroimaging and biomarker research conducted by Morris et al. (2014), Jack et al. (2018), and Villemagne et al. (2013), which reveal marked variability among individuals with similar Aβ burdens. Such findings point to the conclusion that amyloid accumulation alone cannot fully account for the disease’s progression or clinical diversity [54-56].

As a result, research focus has gradually shifted toward soluble Aβ oligomersshort-lived, mobile aggregates of Aβwhich are now regarded as more harmful to neurons than the more stable, fibrillar plaques. These oligomers disrupt normal synaptic activity, enhance oxidative stress and trigger harmful calcium influx into neurons. Importantly, they also contribute to tau pathology by activating specific kinases, including glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5), and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), leading to tau hyperphosphorylation [57-59]. The interaction between Aβ and tau is not simply one-directional; rather, they act in concert to intensify neuronal damage, with their synergistic effects accelerating the degenerative process [60].

Considering these developments, the repeated failure of clinical trials targeting Aβ alone has prompted a re-evaluation of treatment strategies. There is a growing recognition that effective therapeutic interventions must go beyond amyloid reduction and instead address multiple aspects of AD pathology, such as tau dysregulation, neuroinflammation, oxidative injury, and synaptic impairment. As noted by Panza et al. (2019) [61], this shift underscores the necessity for integrated and multi-targeted treatment approaches that reflect the disease’s complex and multifactorial nature. Ultimately, this evolving model portrays AD as a network disorder requiring comprehensive and adaptive therapeutic solutions for meaningful clinical benefit.

The amyloid cascade hypothesis remains a cornerstone in the study of AD proposing that the accumulation of Aβ peptides is a central driver of the disease's pathogenesis. The sequential cleavage of APP by β-and γ-secretases generates Aβ peptides, which aggregate into plaques that disrupt neuronal function and contribute to cognitive decline [62]. Genetic changes and differences in how APP is processed are important in AD, especially in early-onset cases, where an uneven ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 speeds up plaque buildup. The balance between the amyloidogenic and non-amyloidogenic pathways of APP processing is vital for preserving neuronal health, and disruptions in this balance are central to AD development [63]. While the amyloid cascade hypothesis has provided valuable insights into AD pathogenesis, the exact mechanisms through which Aβ induces neurodegeneration remain an area of active research. Continued exploration of Aβ and its interactions with other pathological factors will be critical for developing effective therapies aimed at slowing or halting the progression of AD [33].

Fig. 1: Schematic representation of human APP isoforms and APP-like proteins (APLP1 and APLP2). APP isoforms, ranging from 695 to 770 amino acids, differ in their domain composition [62]. Tau hyper phosphorylation and neurofibrillary tangle formation in AD pathogenesis

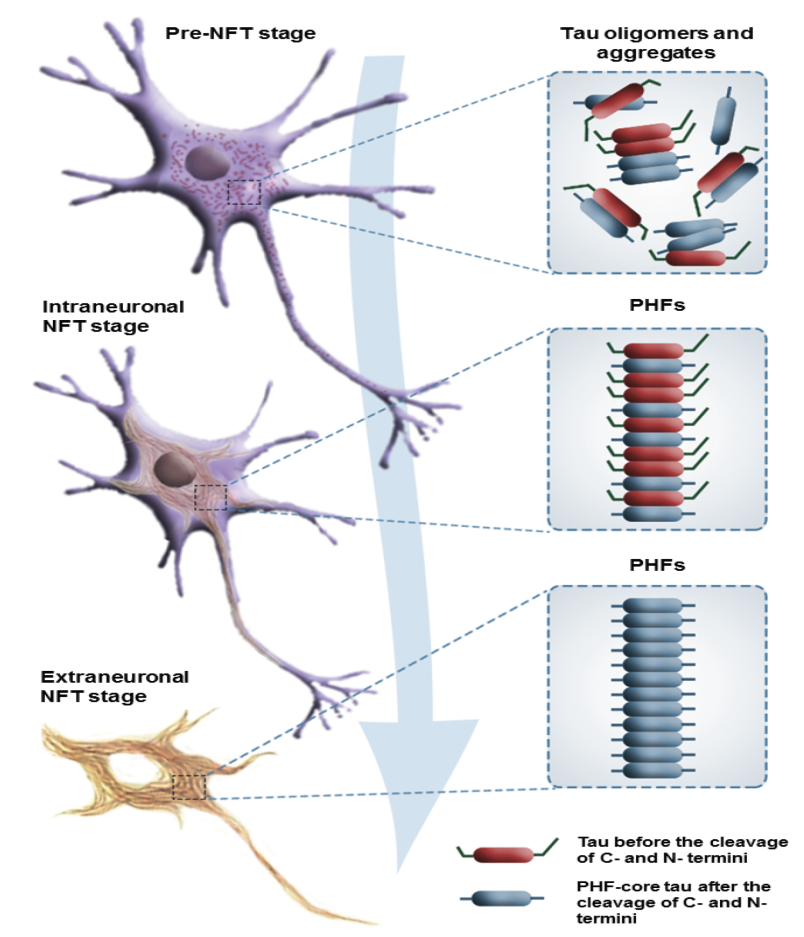

The formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, constitutes a hallmark feature of AD. Tau proteins are highly soluble and predominantly expressed in neurons, where they perform essential roles in stabilizing microtubules [64]. These cytoskeletal structures are integral to maintaining cellular architecture facilitating axonal transport, and supporting various intracellular processes including cell division. Tau's ability to bind microtubules depends on its microtubule-binding domain, which comprises repeat sequences that anchor it to these cytoskeletal components, ensuring their structural integrity and functional stability [65]. Under physiological conditions, tau helps maintain microtubule dynamics, which is critical for the proper functioning of neurons. However, in AD, tau undergoes pathological hyperphosphorylation, a process that compromises its microtubule-stabilizing function [66]. This modification reduces tau’s affinity for microtubules, causing it to detach and aggregate into insoluble twisted filaments, eventually forming NFTs within neurons. The buildup of NFTs interferes with the transport of materials along axons, weakens communication between synapses and eventually causes nerve cell death, which contributes to the memory loss seen in AD [67].

Tau protein exists in multiple isoforms, generated through alternative splicing of the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) gene. These isoforms vary in the number of repeat sequences within their microtubule-binding domains, classified as three-repeat (3R) or four-repeat (4R) tau [68]. Both isoforms are essential for microtubule stability, but their balance is tightly regulated under normal conditions. In AD and other tauopathies, this balance is disrupted, and abnormal hyper phosphorylation of tau leads to its aggregation [69]. The process is mediated by a complex interplay of kinases and phosphatases, with kinases such as GSK-3β and CDK5 playing prominent roles in promoting tau phosphorylation [70]. Once hyperphosphorylated, tau loses its ability to stabilize microtubules, triggering cytoskeletal collapse and impairing neuronal function. These pathological changes are not limited to AD; NFTs also characterize other neurodegenerative disorders, including frontotemporal dementia and progressive supranuclear palsy, illustrating the wider importance of tau pathology in neurodegeneration [71].

While Aβ aggregation has traditionally been considered the primary driver of AD, growing evidence highlights the critical role of tau pathology in the disease’s progression. Tau pathology correlates more strongly with the severity of neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment compared to Aβ deposition [72]. The interplay between Aβ and tau remains an area of active investigation, with studies suggesting that Aβ accumulation may act as a trigger for tau hyperphosphorylation, amplifying the neurodegenerative cascade. This complex relationship has significant implications for therapeutic strategies. Interventions targeting tau pathology, including tau aggregation inhibitors, kinase inhibitors and immunotherapies aimed at clearing hyperphosphorylated tau, are being actively explored [73]. By addressing tau pathology alongside Aβ, these approaches hold promise for mitigating neuronal dysfunction and slowing the progression of AD. Understanding the intricate mechanisms underlying tau’s role in NFT formation and its interplay with other pathological features continues to be a critical focus in the quest for effective treatments for AD [74].

New findings suggest that prion-like mechanisms mediate the intercellular spread of misfolded tau proteins from neuron to neuron. The transmission causes the normal tau proteins in target cells to misfold in a specific way, using exosomes and other biological methods. These processes are involved in the disease's normal progression of tau pathology [75].

Tau accumulation can be visualized in vivo owing to advances in positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. There are strong correlations between tau accumulation in specific brain areas and cognitive impairment in AD patients, 18F Flortaucipir, a tau-specific PET tracer finds. These imaging methods offer a multimodal pathway to follow the disease progress and can enhance the disease precision diagnosis if combined with proteome analysis [76].

Fig. 2: The progression of cytoskeletal changes associated with tau pathology is categorized into three distinct stages: the pre-tangle (pre-NFT) stage, the intraneuronal stage, and the extraneuronal stage [71], https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29071478

Advancing biomarker discovery in AD: insights into pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic strategies

An ideal biomarker for AD should accurately reflect the progression of pathological changes and be applicable in a variety of settings. Primarily, biomarkers should aid in the early and differential diagnosis of AD by detecting or suggesting the underlying brain alterations, even during the asymptomatic and preclinical stages of the disease [77]. A deeper understanding of the biomarker patterns preceding clinical symptoms could help distinguish between individuals at risk for AD and older adults undergoing normal age-related changes. Additionally, biomarkers should correlate with disease progression, allowing for the differentiation of various stages of AD pathology and predicting the potential for further cognitive decline [78]. They should also aid in distinguishing AD from other forms of dementia. Furthermore, biomarkers could enhance drug development efforts by facilitating the identification of new therapeutic targets, screening potential agents and monitoring the effectiveness and appropriate dosage of treatments, as well as supporting subject selection in clinical trials [79].

Table 1: Current and emerging therapeutic strategies targeting AD pathophysiology

| Category | Therapy/candidate | Mechanism of action | Stage | Key insights | References |

| Current approved therapies | |||||

| Cholinesterase inhibitors | Donepezil, Rivastigmine, Galantamine | Inhibit acetylcholinesterase to enhance cholinergic transmission | FDA approved | Improves symptoms but no impact on disease progression | [80] |

| NMDA receptor antagonist | Memantine | Modulates glutamatergic signaling to reduce excitotoxicity | FDA approved | Offers modest cognitive benefits in moderate-to-severe AD. | [81] |

| Anti-amyloid therapy | Lecanemab, Aducanumab | Monoclonal antibodies targeting Aβ plaques | FDA Approved | Slows cognitive decline; mixed clinical efficacy | [82] |

| Emerging therapeutic candidates | |||||

| Anti-tau therapy | BIIB080 (Antisense oligonucleotide) | Reduces tau mRNA and protein expression | Phase 1/2 | Demonstrated dose-dependent tau reduction | [83] |

| Neuroinflammation modulators | AL002, Neflamapimod | Modulate microglial activity and inflammatory signaling | Phase 2 | Aim to restore immune homeostasis. | [84] |

| Microbiome-based modulators | GV-971 (Oligomannate) | Alters gut-brain axis, reduces neuroinflammation | Approved in china; global phase 3 | Improved cognition, novel anti-inflammatory mechanism | [85] |

| Synaptic modulators | CT1812 | Sigma-2 receptor antagonist; displaces toxic Aβ oligomers | Phase 2 | Targets synaptic toxicity mechanisms | [86] |

| -Driven Approaches | Biomarker-guided interventions | Stratifies patients using omics/imaging data | Investigational | Enhances personalized treatment strategies | [87] |

Biomarkers play a crucial role in the early diagnosis, disease staging, prognosis assessment and evaluation of treatment responses. Additionally, they assist in clarifying disease mechanisms and developing innovative therapeutic strategies [88]. Neuropathologically, AD is characterized by the postmortem accumulation of extracellular Aβ plaques, also referred to as senile plaques, and iNFTs formed by abnormally phosphorylated tau protein. In addition to cognitive testing, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of Aβ42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau were among the first biological markers used in diagnosing AD [89].

Oxidative stress is considered a significant factor in AD pathogenesis due to the brain’s high glucose-driven metabolism, limited antioxidant defenses, abundance of active transition metals, and susceptibility to lipid peroxidation, which can catalyze radical formation [90]. Biomarkers linked to oxidative stress in AD include 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT), 8-hydroxyguanosine (8-OHGua), 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), 5-hydroxycytosine, 5-hydroxyuracil, neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and 8-hydroxyadenine. Neuroinflammation, characterized by the activation of glial cells, is another key aspect of AD pathology [91].

Recent research has identified several neuroinflammatory biomarkers linked to microglial cells and astrocytes, providing valuable insights into the disease’s mechanisms and aiding in early detection and diagnosis [92].

Table 2: Reactive species, analytical methods, and precursors in Neuroinflammation: implications for Alzheimer's pathogenesis

| Reactive species | Method of analysis | Precursor | Reference |

| H-formaldehyde | Cell survival assay | Methanol | [93] |

| 4-HNE (4-Hydroxy-2-hexanal) | HPLC/GC | ω-6 fatty acid | [94] |

| MDA (Malondialdehyde) | HPLC/GC | ω-6 fatty acid, ω-3 fatty acid | [94] |

| 5-HEPE (5-Hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid) | UPLC ESI-MS/MS | ω-3 fatty acid | [93] |

Fluid biomarkers in AD: Insights into neuroinflammation and peripheral signatures

Due to its direct connection with the CNS CSF serves as a valuable source for AD biomarkers. CSF reflects the condition of the CNS, and thus, changes in brain pathology are mirrored by alterations in the composition of the CSF. Over the years, CSF biomarker discovery has significantly advanced both research and clinical practices, enhancing our understanding of AD's natural progression [6]. Additionally, the measurement of specific AD biomarkers, such as Aβ, Tau, and pTau, in CSF has become a standard inclusion in the criteria for in vivo AD diagnosis [14].

The exploration of fluid biomarkers has significantly enhanced our understanding of AD pathophysiology, providing invaluable information regarding early diagnosis, disease monitoring and potential therapeutic targets. Traditionally, CSF biomarkers such as decreased amyloid-β42 (Aβ42) and elevated total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau181) have served as core diagnostic indicators. Despite their clinical relevance, the invasive nature of CSF collection has limited its widespread use in routine screening. Consequently, the research focus has shifted toward the identification of non-invasive blood-based biomarkers that can reliably reflect AD pathology [95].

However, the invasive nature of lumbar puncture for CSF collection, along with the associated risks and costs, has limited its widespread use in routine clinical settings, particularly due to patients’ reluctance to undergo such procedures repeatedly. This limitation has shifted the focus toward more accessible biological sources, with blood emerging as the primary alternative [9]. Blood collection is routine, less invasive, and inexpensive and can be easily repeated, making it ideal for use in large-scale population studies. Consequently, blood-based biomarkers have gained attention as viable tools for monitoring disease progression and treatment efficacy in clinical practice [15].

Among these, plasma phosphorylated tau at threonine 217 (p-tau217) has emerged as a particularly robust biomarker. Its levels demonstrate strong concordance with amyloid and tau PET imaging and are highly predictive of cognitive decline, outperforming p-tau181 in discriminative capacity between AD and other neurodegenerative disorders [96]. Additionally, more focus has been given to exosomal microRNAs (miRNAs)—tiny RNA molecules that do not code for proteins, are found in small bubbles outside cells, can pass through the BBB, and can be measured in the blood. Some miRNAs, like miR-132, miR-193b, and miR-34a, are linked to processes related to AD, including how synapses adapt, the addition of phosphate groups to tau proteins, and the processing of amyloid precursor proteins [97].

The rationale for using blood in AD biomarker research lies in the compromised BBB in AD patients, which facilitates the leakage of molecules from the CSF into the bloodstream. These molecules reflect the pathological changes occurring in the brain, making them potential peripheral biomarkers of CNS conditions [13].

However, the use of blood biomarkers faces several challenges due to the complexity of AD pathology and the nature of the blood sample. Biomarker concentrations in blood are typically lower than in CSF, as they are diluted when entering the bloodstream. Additionally, the integrity of the BBB can vary across individuals with AD, affecting the extent of molecule leakage [98]. Furthermore, proteins that cross the BBB may undergo proteolysis in peripheral fluids, complicating the detection of intact biomarkers. Systemic inflammation can also accompany AD, potentially influencing blood protein levels and masking brain-specific biomarkers with peripheral signals. Lastly, the complex composition of blood, including antibodies and other molecules, may interfere with the sensitivity and specificity of biomarker detection assays, further complicating their analysis [99].

Another critical dimension of AD pathology is neuroinflammation, which is now recognized as a central contributor to disease progression. In this context, profiling of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in CSF and plasma has provided further insight. These mediators can be grouped according to their functional roles for ease of understanding and interpretation [99].

Cytokines

These are released by peripheral immune cells, and resident glial cells facilitate bidirectional communication between the AD brain and the periphery [100]. While the exact source of circulating cytokines remains unclear, profiling them could provide insights into the inflammatory response during AD progression. However, findings on circulating cytokines in AD patients remain inconsistent, likely due to variations in detection methods [101].

Proinflammatory cytokines

Interlukein-6(IL-6), interlukein-1β (IL-1β), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are important substances that cause inflammation in AD, produced in the central nervous system by glial cells that come into contact with Aβ and by monocytes/macrophages in the body during strong immune reactions [99]. Studies report both increased and unchanged peripheral levels of these cytokines in AD patients compared to healthy controls. IL-6 and IL-1β levels are lower in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients than in AD, while TNF-α levels vary with disease stage, being lower in mild-to-moderate AD and higher in severe cases. Notably, IL-6 levels in AD patients show a significant correlation between matched CSF and blood samples [102]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, like IL-1β), IL-6) and TNF-α, are often found at higher levels in AD patients and are known to cause activation of glial cells and damage to neurons [103].

Anti-inflammatory cytokines

Interleukin-10 (IL-10), interleukin-4 (IL-4) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) are anti-inflammatory cytokines that help mitigate proinflammatory activation in AD. They suppress macrophage activation and proinflammatory cytokine synthesis. IL-10 modulates glial activation, fostering neuroprotection, while IL-4 promotes neuroprotective phenotypes in astrocytes and microglia, enhancing learning and memory [104]. TGF-β aids in neuroprotection through microglia-mediated Aβ degradation. Peripheral levels of IL-10 and IL-4 in AD patients are generally unchanged, while TGF-β levels are significantly elevated, with higher concentrations in mild-to-moderate AD and lower levels in severe AD. These findings highlight cytokine dysregulation in AD progression [105]. Anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as (IL-10) and (TGF-β), may offer neuroprotective effects by modulating immune responses. However, dysregulation in their signaling can also impair the clearance of neurotoxic proteins [106].

Chemokines

These mediators are crucial for leukocyte activation and migration, resulting in targeted immune responses. In AD, neuroinflammation is characterized by upregulation of plaque-associated chemokines and their receptors, which promotes the recruitment of peripheral monocytes and activation of glial cells. This process plays a significant role in the development of neuroinflammation, contributing to the progression of AD pathology [107]. Chemokines, particularly monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2), C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5), and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), play key roles in the recruitment of immune cells to the central nervous system and are associated with disease progression and cognitive impairment [106].

Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1)

MCP-1, also known as CCL2 is a key chemokine in AD, involved in recruiting immune cells to senile plaques. MCP-1 expression is linked to Aβ pathology, with its upregulation in microglia, astrocytes and human monocytes in response to Aβ [108]. While MCP-1's production may initially help eliminate Aβ deposits, its overexpression in later stages of AD may exacerbate neuroinflammation. Clinical studies show increased CCL2 levels in both CSF and peripheral samples of AD patients, with higher concentrations observed in MCI patients. Some chemokines may also have neuroprotective roles, despite primarily promoting inflammation [109].

CX3CL1 (Fractalkine)

Soluble fractalkine, a chemoattractant for natural killer (NK) cells expressed by neurons and glial cells in the CNS, plays an anti-inflammatory role by regulating microglial activation and preventing neurotoxicity. Elevated levels of fractalkine have been observed in both central and peripheral samples from patients with MCI, compared to those with severe AD [110]. This suggests that, in AD progression, fractalkine may lose its ability to control microglial activation, potentially contributing to neurodegeneration. These findings highlight its dual role in inflammation regulation during AD pathogenesis [111] and these findings underscore the necessity of adopting a multifactorial biomarker approach, as no single marker sufficiently captures the complex, multifaceted nature of AD. A growing consensus supports the integration of amyloid, tau, neurodegeneration and inflammatory markers into composite panels, which could substantially enhance diagnostic precision and facilitate individualized treatment strategies [109].

Genetic and protein biomarkers in AD: insights into pathogenesis and diagnostic advancements

The genotypic analysis of apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene polymorphic alleles is also used as a prognostic marker of late-onset AD. Although studies regarding these diagnostic markers for AD are in progress, large variability and inconsistency exist between studies, delaying the markers' use as a diagnostic tool for AD in the clinical setting [25]. A lot of different mutations of them have been reported. However, their potential use as prodromal AD biomarkers remains uncertain. Recently, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) identified putative novel candidate genes, including complement component (3b/4b) receptor 1 (CR1), clusterin (CLU), phosphatidylinositol binding clarithrin assembly protein (PICALM) and bridging integrator 1 (BIN1) and another GWAS showed that common variants in MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2uAP, CD33 and EPHA1 are also associated with late-onset AD [112]. In addition, several studies showed that circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood serum have characteristic changes in AD patients, suggesting that miRNAs could be used in AD diagnosis, solely or in combination with other AD biomarkers [113].

APP

Aβ plaques, formed by extracellular Aβ protein aggregation in the brain, are key neuropathological markers of AD. Aβ was first identified by Glenner and Wong (2012) in amyloid plaques linked to cerebrovascular amyloidosis and AD [77]. Subsequent research revealed that Aβ is derived from APP), as identified through cloning and gene mapping. APP is processed via two proteolytic pathways: the non-amyloidogenic pathway, where α-secretase generates sAPPα and C83 fragments, and the amyloidogenic pathway, where β-secretase (BACE1) produces sAPPβ and C99. γ-Secretase cleaves C99 to form Aβ peptides, which aggregate into amyloid plaques. While Aβ40 is the most common form, Aβ42, a longer variant, is more strongly linked to AD. Mutations in APP, often autosomal dominant, can lead to early-onset AD, with certain mutations like A673T showing protective effects [27].

Presenilin and γ-secretase complexes

The first evidence of genetic linkage for AD was found on chromosome 14, with a locus (AD3) associated with aggressive AD forms mapped to 14q24.3. A gene named (PSEN1), found in this area, was recognized as an important part of the γ-secretase complex and connected to early-onset AD [22]. Over 180 mutations in PSEN1 have been identified, causing severe AD with complete penetrance. PSEN2, a homolog of PSEN1, also harbors mutations associated with early-onset AD, though with later onset and lower penetrance. PSEN2 mutations increase β-secretase activity through reactive oxygen species-dependent mechanisms [114].

Apolipoprotein E (APOE)

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) facilitates cholesterol transport to neurons via APOE receptors and binds to Aβ peptide, influencing its aggregation and clearance. Three alleles, E2, E3, and E4, result from non-synonymous SNPs in exon 4 of the APOE gene. The E4 allele significantly increases the risk of AD-), while the E2 allele offers protective effects [19]. APOE isoforms regulate brain Aβ metabolism, lipid transport, neuronal signaling and neuroinflammation. The E4 allele is linked to sporadic late-onset AD, making APOE genotyping a valuable tool for assessing AD risk and planning healthcare strategies across populations [115].

Although the roles of APOE ε4, presenilin mutations, and retromer dysfunction have been well-characterized in the genetic landscape of AD, recent findings from GWAS have significantly expanded our understanding of the disease's genetic etiology. Among the newly identified loci, rare variants in the TREM2 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2) gene have garnered considerable attention. These variants, particularly R47H, are linked to a two-to four-fold increased risk of late-onset AD. Functionally, TREM2 plays a key role in microglial activity, especially in regulating phagocytosis and neuroinflammation. Mutations in this gene are believed to compromise microglial response to amyloid deposition, thereby promoting neurodegenerative changes [116, 117].

Another key gene linked to susceptibility, found through GWAS, is ABCA7 (ATP-binding cassette sub-family A member 7), which helps with moving fats and clearing amyloid-beta. Variants that cause loss of function in ABCA7 are believed to disrupt these processes, possibly speeding up the buildup of amyloid and problems with synapses. Loss-of-function variants in ABCA7 are thought to impair these physiological processes, potentially accelerating amyloid accumulation and synaptic dysfunction [118]. These findings reinforce the view that immune modulation and lipid metabolism are integral components of AD pathogenesis, complementing existing hypotheses centered on amyloid-beta and tau protein pathology. The identification of these genes represents a pivotal step in unraveling the polygenic and multifactorial nature of AD.

Retromer protein complex

The retromer protein complex helps move transmembrane proteins from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network and is made up of Vps35, Vps26, Vps29, SNX1, SNX2, and possibly SNX5/6 in mammals. Retromer dysfunction has been linked to late-onset AD [119]. Studies show reduced VPS35 and VPS26 levels in AD, with retromer disruption increasing Aβ levels. Conversely, overexpression of retromer components decreases Aβ. The neuronal receptor sorLA, a retromer candidate, is downregulated in late-onset AD, influencing APP processing. Retromer defects likely prolong APP and its cleaving enzymes’ co-residence in organelles, enhancing APP processing and Aβ production, contributing to AD pathology [120].

Clinical implications of polygenic risk scores in AD the development of polygenic risk scores (PRS) a promising approach for quantifying cumulative genetic risk in complex disorders such as AD. Unlike traditional single-gene analyses, PRSs amalgamate the effects of numerous common and rare genetic variants to generate an individualized risk profile. This approach enables finer stratification of at-risk populations, especially among individuals who may not carry the well-established APOE ε4 allele but still harbor elevated risk due to the presence of multiple low-effect variants [121].

From a clinical perspective, PRSs have shown potential in enhancing early disease detection, refining patient selection for preventive interventions, and facilitating the design of personalized therapeutic strategies. Their utility has also been explored in enriching cohorts for clinical trials, particularly those targeting preclinical or prodromal stages of AD [122]. Nevertheless, several limitations must be addressed before their integration into routine clinical practice, including population-specific variability, reduced accuracy in non-european ancestry groups and the lack of universally accepted scoring thresholds [123].

Despite these challenges, the application of PRS in conjunction with known genetic markers such as TREM2, ABCA7, and APOE has the potential to significantly advance precision medicine approaches in AD. This integration of genetic risk profiling could eventually inform clinical decisions and guide the development of targeted therapies aimed at delaying or preventing disease onset [124].

Table 3: Biomarkers and its analytical methods targeting neuroinflammation in alzheimer’s Pathogenesis

| Biomarker | Observation | Method of analysis | Reference |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) | • Increased CSF and plasma levels in AD patients • Associated with Aβ plaques, white matter damage, cognitive decline |

Enzyme linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) | [67, 115, 125] |

| Soluble TREM2 (sTREM2) | • Elevated in CSF of AD • Increased in autosomal dominant AD | ELISA (C57BL/6J mouse model) | [113, 120] |

| Chitinase-3-like protein 1 (YKL-40) | • Elevated plasma levels in early AD • Levels may vary with sex and ethnicity | ELISA | [126] |

| S100B | • Moderately elevated levels in AD. | ECLIA (Electrochemiluminescence IA) | [127] |

| Monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) | • Increased activity in cortical and hippocampal regions of AD patients | PET) | [108] |

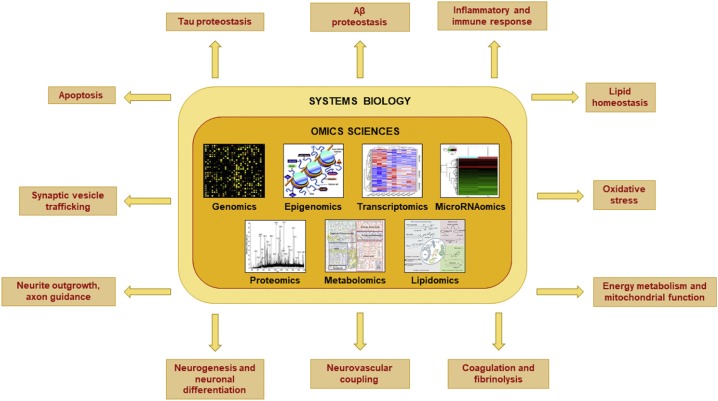

Integrative systems biology in AD: bridging multi-omics and neuroimaging for precision medicine

SB is an integrative, hypothesis-free approach that investigates biological processes using network theory [119]. It explores molecular interactions, such as those between DNA and proteins, RNA and proteins, and metabolites, within a systemic context over time. SB aims to understand how these interconnected networks are organized and function in both health and disease states [128]. Aging, a key risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases (ND) like AD), has been extensively studied using omics technologies at the molecular level. These studies have identified mechanisms such as genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, dysregulated protein homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, and stem cell deficiencies, all of which contribute to the aging process and age-related diseases [113].

Despite the complexities in understanding the interactions among these mechanisms, SB provides valuable tools for exploring the intricate phenotypes of aging and disorders like AD. Although the integrative systems-level knowledge of preclinical AD remains in early stages, the ongoing development of omics-guided drug discovery and biomarker co-development is anticipated to help identify early biological markers of AD [129]. These advances are crucial for enabling personalized or stratified treatment approaches. This highlights the latest advancements in omics biomarkers for AD including genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, and outlines SB network methods for integrating multi-omics data. It also explores how combining neuroimaging with omics data can further support personalized medicine in AD management [114].

The combination of multi-omics data with Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has emerged as a robust strategy to deepen our understanding of complex neurological diseases, particularly AD. Multi-omics approaches, which analyze multiple biological layers such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, provide a detailed molecular landscape of disease states. When integrated with MRI, offering high-resolution structural and functional brain information, this methodology enables the identification of early biomarkers predictive of cognitive decline and disease progression [129].

Recent advances have demonstrated the effectiveness of this integrative approach. For instance, Hassan et al. (2025) created the MINDSETS framework, which combines different types of biological data with long-term MRI scans to tell apart AD from vascular dementia with about 89% accuracy. This approach incorporates radiomic features extracted from MRI scans combined with clinical, cognitive, and genetic datasets, enhancing diagnostic precision and supporting personalized medicine strategies [130].

Similarly, Luo et al. (2025) developed a multi-omics predictive model for early Parkinson’s disease by fusing radiomics signatures derived from MRI with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and genetic information. Their model achieved a high predictive accuracy, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.928, underscoring the promise of integrating diverse biological data with imaging to improve early disease detection and prognosis [131].

These studies exemplify the potential of combining multi-omics and MRI modalities to provide comprehensive insights into neurodegenerative disorders, facilitating earlier diagnosis, more accurate disease classification, and tailored therapeutic interventions. This integrative strategy represents a significant advancement in the application of systems biology to clinical neuroscience.

Synergizing neuroimaging and omics data: A Novel framework for disease modeling in AD

Over the past decade, cross-disciplinary and omics-based integrative approaches, such as neuroimaging-omics, have gained significant traction in neuroscience clinical research [132]. These approaches offer promising potential in unraveling the connections between genetic mutations, gene expression patterns and protein-protein interactions that are linked to distinct brain network patterns, both structural and functional and their associated pathophysiological trajectories [133].

Several international initiatives have been launched in this field, including the imaging genetics for mental disorders in adolescents (IMAGEN) and enhancing neuroimaging genetics through meta-analysis (ENIGMA) studies, which aim to uncover the genetic and neurobiological foundations of cognition, behavior and their related disorders as reflected in structural and functional brain endorphin [134]. These initiatives contribute to advancing knowledge about the genetic and biological drivers of brain changes, at both regional and network levels, by using integrative multi-modal approaches that capture diverse temporal and spatial scales (i. e., systems neurophysiology [135].

Integrating omics and neuroimaging data offers a valuable opportunity to identify and better understand previously unexplored genotypic and phenotypic variability in AD, with the aim of discovering clusters of genetic, biological and phenotypic markers (intermediate brain endophenotypes) to inform preventive strategies and personalized medicine (PM) approaches [136].

Given the vast and complex nature of the data generated by neuroimaging-omics research, there is an increasing demand for novel integration and analytical methods. For instance, GWAS have highlighted genetic factors contributing to the onset and progression. Unsupervised clustering techniques have been used to categorize patients based on brain phenotypes and genetic data, as well as blood-based biomarkers. A cutting-edge approach known as imaging genetics, which combines genome-wide association data with neuroimaging results, has enabled the identification of genes associated with brain imaging endophenotypes, such as brain atrophy [137]. GWAS has found a number of AD risk loci, such as Clusterin (CLU) and MS4A6E. Subsequent imaging genetics studies investigated the relationship between these genetic variants and cortical thickness, a neuroimaging endophenotype crucial for AD. For example, studies have shown that risk alleles in CLU are linked to changes in the microstructure of white matter, which could be a sign of a link to the development of AD. Changes in cortical thickness have also been linked to variants in MS4A6E, especially in areas that are more likely to atrophy due to AD [138]. These results give us some information about the molecular causes of AD but it's important to remember that imaging-genetic connections don't always hold up. Different imaging methods, sample sizes, and analysis methods used in different studies could cause results that don't match up. So, imaging genetics could help us understand the links between genetic risk and neurodegeneration, but more research using standardized methods is needed to confirm these links and fully use their potential to help us understand the causes of AD [139].

Furthermore, this imaging genetics approach has been employed to investigate the genetic factors contributing to changes in brain structural connectivity in AD, as well as the relationship between genetic variants and functional brain networks or their subcomponents [140].

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) and resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) studies have shown that the APOE ε4 allele is associated with altered resting-state activity in key macroscale brain networks, such as the default mode network, in cognitively healthy individuals and those experiencing aging [141].

Over the past decade, significant advancements in multi-omics biomarker profiling have greatly enhanced our understanding of alzheimer's pathophysiology, revealing complex biological signatures linked to disease progression [144]. The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) with larger patient cohorts has led to the identification of over 50 AD-associated genes, highlighting diverse molecular pathways contributing to disease onset. Parallel studies of genomics and transcriptomics have underscored the influence of genetic risk factors on gene expression, while epigenomic profiling has exposed AD-related DNA methylation and histone modifications that may be influenced by environmental factors. Additionally, proteomics and metabolomics have provided valuable insights into protein abundance and metabolic dysregulation in AD [145]. Collectively, these omics approaches have identified the dysregulation of key biological processes such as proteostasis, inflammation, lipid metabolism and oxidative stress, which play a crucial role in AD pathogenesis [144]. The application of SB frameworks enables the exploration of how multifactorial perturbations lead to disease by altering network states. This multi-omics data-driven strategy not only deepens our understanding of AD mechanisms but also holds promise for improving patient stratification and enabling personalized treatments, potentially at early or preclinical stages. While the field is still developing, ongoing efforts to integrate various omics layers with clinical and neuroimaging data, along with the establishment of collaborative initiatives, are poised to advance the precision medicine paradigm for AD, offering more tailored, effective therapies for individuals across the disease continuum [146]. SB and multi-omics have helped us understand important molecular processes in AD, but a closer look shows that there are big problems with translating these findings into real life. Integrative network models have found new therapeutic targets, like TREM2 and CTSB, that have been tested in systems related to AD. However, discoveries based on proteomics often don't work well when repeated because of batch effects, differences in how samples are prepared and differences in the instruments used. These technical problems, along with the fact that there are no standard pipelines for normalizing, integrating and interpreting data, make it hard to compare studies and use them in clinical settings. To move these tools from discovery to precision medicine, it is important to set up standardized workflows and data standards for the whole cohort [147-149].

Fig. 3: Exploratory, high-throughput omics techniques reveal important molecular and cellular pathways linked to the pathophysiology of (AD). The most common sources of data are open multi-omics repositories like the cancer genome atlas (TCGA, for reference pipelines), accelerating medicines partnership–alzheimer’s disease (AMP-AD), and the AD Neuroimaging Initiative(ADNI) Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression is used to pick important features, dimensionality reduction methods like principal component regression (PCA) and t-distributed stochastic neighbor imgding (t-SNE) help group data, and weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) is used to find key genes and hidden patterns. R/Bioconductor, cytoscape, and python-based platforms are examples of frequently used tools. Recent multi-cohort omics integration studies describe representative pipelines [142, 143]

Computational advances in integrating multi-omics data for AD research

Recently,SB has emerged as a powerful framework for deciphering the complex molecular underpinnings of neurodegenerative diseases, particularly AD. The integration of multi-omics data. However, extracting meaningful insights from these high-dimensional datasets necessitates the use of sophisticated computational approaches. Key tools such as WGCNA, machine learning algorithms, and multi-omics factor analysis plus (MOFA+) have proven instrumental in advancing our understanding of AD by enabling data-driven discovery and patient stratification [150].

WGCNA

WGCNA is widely used in transcriptomic analysis to uncover clusters of co-expressed genes that may be linked to clinical or pathological features. In the context of AD, this method has facilitated the identification of gene modules and hub genes associated with cognitive decline and neuropathological changes. For example, Chen et al. (2024) applied WGCNA to hippocampal gene expression data and identified genes such as cathepsin B (CTSB) and TREM2, which showed strong associations with amyloid plaque burden and memory deficits. These findings highlight the potential of WGCNA in elucidating disease-related molecular pathways and identifying potential therapeutic targets [151].

Machine learning applications

Machine learning (ML) techniques have become indispensable in analyzing complex biomedical data, particularly in AD research. Algorithms such as support vector machines, random forests and deep learning models are capable of uncovering intricate patterns and making accurate predictions from multi-modal datasets. Recent studies) demonstrated the effectiveness of deep learning in distinguishing early-stage AD patients from cognitively healthy individuals by integrating proteomic profiles with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features. The model achieved high diagnostic accuracy and identified predictive markers linked to neurodegeneration, underscoring the potential of ML in precision diagnostics and early intervention [152].

Integrative multi-omics analysis with (MOFA+)

MOFA+is a versatile framework that integrates multiple omics layers using unsupervised learning to identify latent factors representing both shared and unique sources of variation. Its application in AD research has provided insights into the molecular heterogeneity of the disease. Müller et al. (2024) utilized MOFA+to analyze transcriptomic, epigenomic and metabolomic data from AD brain samples, revealing distinct molecular subtypes associated with different clinical trajectories. This integrative approach offers a pathway toward personalized medicine by facilitating biomarker discovery and enhancing our understanding of disease mechanisms [153].

CONCLUSION

AD is a complicated brain condition characterized by the interaction of amyloid and tau problems, oxidative stress, and long-term brain inflammation, requiring a move towards combined and tailored treatment methods. This review emphasizes the critical role of SB and multi-omics approaches in elucidating AD pathophysiology, identifying clinically actionable biomarkers, and advancing precision diagnostics. To accelerate clinical translation, future research should prioritize the establishment of longitudinal, large-scale multi-omics cohorts spanning the full spectrum of AD progression, thereby enabling the temporal mapping of molecular alterations and facilitating early detection efforts. Standardizing data acquisition and analysis pipelines across platforms is equally important to ensure reproducibility and cross-study comparability. Moreover, the integration of omics-based biomarker discovery with neuroimaging and cognitive profiling will enhance patient stratification and support the development of tailored therapeutic interventions. Bridging the gap between molecular discovery and clinical application will require streamlined translational pipelines and coordinated collaboration between academic institutions, regulatory bodies, and industry partners; by harnessing the combined potential of high-throughput omics, advanced computational tools, and neuroimaging analytics, the field is poised to define robust molecular signatures that inform disease prognosis and guide personalized treatment strategies, ultimately paving the way for more effective and targeted approaches to managing AD. Standardized multi-omics consortia and unified data repositories, similar to ADNI and AMP-AD, will enable future reproducible, cross-cohort analyses. Predictive modeling, patient classification, and biomarker identification can all be improved by integrating AI and machine learning frameworks. To define the course of illness, future studies must focus on multimodal, longitudinal studies that combine neuroimaging, transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic data. Establishing translational pipelines that link biomarker discoveries with treatment development and clinical trials is crucial to realizing the promise of precision medicine in AD.

ABBREVIATIONS

AD: Alzheimer’s Disease, Aβ: Amyloid-beta, APP: Amyloid Precursor Protein, APOE: Apolipoprotein E, MAPT: Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau, NFT: Neurofibrillary Tangle, ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species, RNS: Reactive Nitrogen Species, CNS: Central Nervous System, BBB: Blood-Brain Barrier, FAD: Familial Alzheimer’s Disease, SAD: Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease, EOAD: Early-Onset al. zheimer’s Disease, BACE1: Beta-site APP-Cleaving Enzyme 1, GSK-3β: Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta, CDK5: Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 5, MAPKs: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases, CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid, PET: Positron Emission Tomography, MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging, GWAS: Genome-Wide Association Studies, PRS: Polygenic Risk Scores, CLU: Clusterin, CR1: Complement Receptor 1, PICALM: Phosphatidylinositol Binding Clathrin Assembly Protein, BIN1: Bridging Integrator 1, TREM2: Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2, ABCA7: ATP-Binding Cassette Sub-Family A Member 7, MS4A6E: Membrane-Spanning 4-Domains Subfamily A Member 6E, sTREM2: Soluble Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2, GFAP: Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein, YKL-40: Chitinase-3-like Protein 1, MAO-B: Monoamine Oxidase B, SB: Systems Biology, MOFA+: Multi-Omics Factor Analysis Plus, WGCNA: Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis, MDA: Malondialdehyde, 4-HNE: 4-Hydroxy-2-hexenal, 3-NT: 3-Nitrotyrosine, 8-OHdG – 8: Hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine, 8-OHGua: 8-Hydroxyguanosine, NT-3: Neurotrophin-3, IL-1β: Interleukin-1 beta, IL-6: Interleukin-6, TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha, IL-10: Interleukin-10, TGF-β: Transforming Growth Factor-beta, MCP-1:Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1,CX3CL1:Fractalkine, APLP1: Amyloid Precursor-Like Protein 1, APLP2: Amyloid Precursor-Like Protein 2, sAPPα: Soluble Amyloid Precursor Protein Alpha, C99 – C-terminal 99 Amino Acid Fragment, C83: C-terminal 83 Amino Acid Fragment, VPS: Vacuolar Protein Sorting, SNX: Sorting Nexin, ADNI: Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, AMP-AD: Accelerating Medicines Partnership Alzheimer’s Disease, ENIGMA: Enhancing NeuroImaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis, IMAGEN: Imaging Genetics.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Jithin Mathew: Conceptualization, data curation, writing original draft, writing-review and editing. Anson Sunny Maroky: Writing original draft, writing-review and editing. Sivarangini S: Investigation, Supervision. Anchu Chandrababu: Investigation, Supervision.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

Lai Y, Lin C, Lin X, Wu L, Zhao Y, Lin F. Identification and immunological characterization of cuproptosis related molecular clusters in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022 Jul 28;14:932676. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.932676, PMID 35966780.

Moebius HJ, Church KJ. The case for a novel therapeutic approach to dementia: small molecule hepatocyte growth factor (HGF/MET) positive modulators. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;92(1):1-12. doi: 10.3233/JAD-220871, PMID 36683507.

Volloch V, Rits Volloch S. Amyloid beta as a protective factor rather than a pathogen in Alzheimer’s disease: revisiting the Aβ paradox. Neurobiol Aging. 2023;125:45-54. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2023.01.004.

Bellomo G, Toja A, Paolini Paoletti F, Ma Y, Farris CM, Gaetani L. Investigating alpha-synuclein co-pathology in Alzheimer’s disease by means of cerebrospinal fluid alpha-synuclein seed amplification assay. Alzheimers Dement. 2024 Apr;20(4):2444-52. doi: 10.1002/alz.13658, PMID 38323747.

Andrade Guerrero J, Santiago Balmaseda A, Jeronimo Aguilar P, Vargas Rodriguez I, Cadena Suarez AR, Sanchez Garibay C. Alzheimer’s disease: an updated overview of its genetics. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Feb 13;24(4):3754. doi: 10.3390/ijms24043754, PMID 36835161.

McGrowder DA, Miller F, Vaz K, Nwokocha C, Wilson Clarke C, Anderson Cross M. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: current evidence and future perspectives. Brain Sci. 2021 Feb;11(2):215. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11020215, PMID 33578866.

Ma YN, Xia Y, Karako K, Song P, Tang W, Hu X. Serum proteomics reveals early biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: the dual role of APOE-ε4. BioSci Trends. 2025 Mar 6;19(1):1-9. doi: 10.5582/bst.2024.01365, PMID 39842814.

Hu Y, Cho M, Sachdev P, Dage J, Hendrix S, Hansson O. Fluid biomarkers in the context of amyloid targeting disease modifying treatments in Alzheimer’s disease. Med. 2024 Oct 11;5(10):1206-26. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2024.08.004, PMID 39255800.

Kitsak M, Sharma A, Menche J, Guney E, Ghiassian SD, Loscalzo J. Tissue specificity of human disease module. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35241. doi: 10.1038/srep35241, PMID 27748412.

Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature. 2016;537(7620):347-55. doi: 10.1038/nature19949, PMID 27629641.

Huang S, Wang YJ, Guo J. Biofluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: progress problems and perspectives. Neurosci Bull. 2022 Jun;38(6):677-91. doi: 10.1007/s12264-022-00836-7, PMID 35306613.

Liu Y, Tan Y, Zhang Z, Yi M, Zhu L, Peng W. The interaction between ageing and Alzheimer’s disease: insights from the hallmarks of ageing. Transl Neurodegener. 2024;13(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s40035-024-00397-x, PMID 38254235.

Chaudhuri S, Cho M, Stumpff JC, Bice PJ, IS O, Ertekin Taner N. Cell specific transcriptional signatures of vascular cells in Alzheimer’s disease: perspectives pathways and therapeutic directions. Mol Neurodegener. 2025;20(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13024-025-00798-0, PMID 39876020.

Lista S, Imbimbo BP, Grasso M, Fidilio A, Emanuele E, Minoretti P. Tracking neuroinflammatory biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: a strategy for individualized therapeutic approaches? J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21(1):187. doi: 10.1186/s12974-024-03163-y, PMID 39080712.

Colvee Martin H, Parra JR, Gonzalez GA, Barker W, Duara R. Neuropathology neuroimaging and fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024 Mar 27;14(7):704. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14070704, PMID 38611617.

McInvale JJ, Canoll P, Hargus G. Induced pluripotent stem cell models as a tool to investigate and test fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Brain Pathol. 2024 Jul;34(4):e13231. doi: 10.1111/bpa.13231, PMID 38246596.

Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Miller MJ, Aisen PS, Albala B, Beckett LA. Increasing participant diversity in AD research: plans for digital screening blood testing and a community engaged approach in the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging Initiative 4. Alzheimers Dement. 2023 Jan;19(1):307-17. doi: 10.1002/alz.12797, PMID 36209495.

Dias D, Socodato R. Beyond amyloid and tau: the critical role of microglia in Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. Biomedicines. 2025;13(2):279. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines13020279, PMID 40002692.

Buccellato FR, D Anca M, Fenoglio C, Scarpini E, Galimberti D. Role of oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s disease and neurodegeneration: from pathogenic mechanisms to biomarker discovery. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Sep 26;10(9):1353. doi: 10.3390/antiox10091353, PMID 34572985.

Kazemeini S, Nadeem Tariq A, Shih R, Rafanan J, Ghani N, Vida TA. From plaques to pathways in Alzheimer’s disease: the mitochondrial neurovascular metabolic hypothesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Oct 21;25(21):11720. doi: 10.3390/ijms252111720, PMID 39519272.

Tripathi PN, Lodhi A, Rai SN, Nandi NK, Dumoga S, Yadav P. Review of pharmacotherapeutic targets in Alzheimer’s disease and its management using traditional medicinal plants. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2024;14:47-74. doi: 10.2147/DNND.S452009, PMID 38784601.

Fisar Z. Linking the amyloid tau and mitochondrial hypotheses of Alzheimer’s disease and identifying promising drug targets. Biomolecules. 2022 Nov 11;12(11):1676. doi: 10.3390/biom12111676, PMID 36421690.

Gaur A, Kaliappan A, Balan Y, Sakthivadivel V, Medala K, Umesh M. Sleep and Alzheimer: the link. Maedica (Bucur). 2022 Jan;17(1):177-85. doi: 10.26574/maedica.2022.17.1.177, PMID 35733758.

Dominguez Gortaire J, Ruiz A, Porto Pazos AB, Rodriguez Yanez S, Cedron F. Alzheimer’s disease: exploring pathophysiological hypotheses and the role of machine learning in drug discovery. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 Mar 3;26(3):1004. doi: 10.3390/ijms26031004, PMID 39940772.

Gueorguieva I, Chua L, Willis BA, Sims JR, Wessels AM. Disease progression model using the integrated Alzheimer’s disease rating scale. Alzheimers Dement. 2023 Jun;19(6):2253-64. doi: 10.1002/alz.12876, PMID 36450003.

Armstrong RA. The pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: a reevaluation of the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;2011:630865. doi: 10.4061/2011/630865, PMID 21331369.

Levin J, Voglein J, Quiroz YT, Bateman RJ, Ghisays V, Lopera F. Testing the amyloid cascade hypothesis: prevention trials in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Dec;18(12):2687-98. doi: 10.1002/alz.12624, PMID 35212149.

Zhao B, Zang P, Quan M, Wang Q, Guo D, Jia J. The effect of APOE ε4 on Alzheimer’s disease fluid biomarkers: a cross sectional study based on the coast. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2025 Jan;31(1):e70202. doi: 10.1111/cns.70202, PMID 39749650.

Volloch V, Rits Volloch S. The amyloid cascade hypothesis 2.0: generalization of the concept. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2023;7(1):21-35. doi: 10.3233/ADR-220079, PMID 36777328.

Kepp KP, Robakis NK, Hoilund Carlsen PF, Sensi SL, Vissel B. The amyloid cascade hypothesis: an updated critical review. Brain. 2023 Oct;146(10):3969-90. doi: 10.1093/brain/awad159, PMID 37183523.

Reitz C. Alzheimer’s disease and the amyloid cascade hypothesis: a critical review. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:369808. doi: 10.1155/2012/369808, PMID 22506132.

Alka T. Novel heterocyclic hybrids as promising scaffold for the management of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2025;17(2):1-15. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i2.52596.

El Assal MI, Samuel D. Optimization of rivastigmine chitosan nanoparticles for neurodegenerative Alzheimer in vitro and ex vivo characterizations. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2022;14(1):17-27. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2022v14i1.43145.

Chukwu LC, Ekenjoku JA, Ohadoma SC, Olisa CL, Okam PC, Okany CC. Advances in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: a re-evaluation of the amyloid cascade hypothesis. World J Adv Res Rev. 2023 Mar;17(2):882-904. doi: 10.30574/wjarr.2023.17.2.20200335.

Alawode DO, Fox NC, Zetterberg H, Heslegrave AJ. Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers revisited from the amyloid cascade hypothesis standpoint. Front Neurosci. 2022 Apr 27;16:837390. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.837390, PMID 35573283.

Naseem S, Temirak A, Imran A, Jalil S, Fatima S, Taslimi P. Therapeutic potential of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles as potential lead compounds for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. RSC Adv. 2023;13(26):17526-35. doi: 10.1039/D3RA01953E, PMID 37304812.

Garcia Garcia A, Rojas S, Rodriguez Dieguez A. Therapy and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: from discrete metal complexes to metal organic frameworks. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11(30):7024-40. doi: 10.1039/D3TB00427A, PMID 37435638.

Frisoni GB, Altomare D, Thal DR, Ribaldi F, Van Der Kant R, Ossenkoppele R. The probabilistic model of Alzheimer disease: the amyloid hypothesis revised. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2022;23(1):53-66. doi: 10.1038/s41583-021-00533-w, PMID 34815562.

Janadri S, Dadmi S, Mudagal MP, Sharma UR, Vada S, Haribabu T. Alzheimer’s disease: comprehensive insights into risk factors, biomarkers, and advanced treatment approaches. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2025;17(1):1-10. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i1.6039.

Kurkinen M, Fulek M, Fulek K, Beszlej JA, Kurpas D, Leszek J. The amyloid cascade hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease: should we change our thinking? Biomolecules. 2023;13(3):453. doi: 10.3390/biom13030453, PMID 36979388.

Akila S, Malar Vizhi S, Vijayalakshmi P, Clara Mary A, Rajalakshmi M. Prediction of anti-Alzheimer’s activity of flavonoids targeting CD33 through in silico approach. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2021;13(4):64-6. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2021v13i4.42746.

Kametani F, Hasegawa M. Reconsideration of amyloid hypothesis and tau hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2018 Jan 22;12:25. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00025, PMID 29440986.