Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 271-284Original Article

DEVELOPMENT AND OPTIMIZATION OF ORAL LACIDIPINE PROBILOSOMES: A BOX–BEHNKEN DESIGN-BASED STUDY

FARAH AYMAN ALSHANTIR*, KHALID KADHEM AL-KINANI

Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq

*Corresponding author: Farah Ayman Alshantir; *Email: farah.ayman2200@copharm.uobaghdad.edu.iq

Received: 12 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 16 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to enhance the oral bioavailability of lacidipine (LCDP), a drug with poor aqueous solubility, by formulating it as bilosomes and subsequently converting the optimized formulation (Bopt) into a stable probilosomal powder (PBopt) using freeze-drying.

Methods: Bilosomes of LCDP were produced using ethanol-injection method and optimized utilizing Box-Behnken design (BBD) (a quality by design approach QBD). The optimized bilosome formulation was subsequently transformed to a free-flowing probilosome powder after using the freeze-drying method. Cholesterol (CHO), the surfactant Span®60, and the bile salt sodium deoxycholate (SDC) served as independent formulation factors, while particle size (PS, nm), entrapment efficiency (EE%), and polydispersity index (PDI) were selected as dependent responses.

Results: The optimized probilosome formulation (PBopt), with the highest desirability (0.904), indicating near-optimal performance in achieving the desired formulation characteristics as suggested by BBD, demonstrated a PS of 198.3 nm, a PDI of 0.21, a zeta potential (ZP) of −25 mV, an EE% of 93.7%, and an in vitro drug release of 90.7% within 45 min, corresponding to the Bopt formula. The BBD model showed statistically significant effects (p<0.05) on EE% and PS, indicating robust optimization, while the effect on PDI was non-significant (p>0.05). Stability studies showed that the LCDP PBopt formulation maintained its relative PS and EE% for at least three months, indicating good stability attributes.

Conclusion: Bilosomes are effective nanovesicular carriers that can enhance LCDP oral bioavailability, thus overcoming the inherent drug solubility limitations. Also, the probilosome’s free-flowing powder can be easily converted into oral solid dosage forms, overcoming the drawbacks of liquid formulations. This makes LCDP’s probilosomes as a promising approach in pharmaceutical applications.

Keywords: Bilosome, Probilosome, Ethanol-injection, Solubility, Lacidipine, Box-behnken design

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54567 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Among all drug delivery systems, the oral route remains the most favored route, owing to its non-invasiveness, convenience, affordability, patient adherence, and scalability. Based on recent data, oral medications dominate the pharmaceutical industry, with around 90% of their products are taken orally [1]. Furthermore, around 40% of drugs face development limitations because of poor water solubility and low bioavailability [2]. These limitations are associated with Class II and IV drugs as outlined by the biopharmaceutics classification system [3]. Enhancing drug solubility and bioavailability has become a critical focus in pharmaceutical formulation, as overcoming these barriers is essential for the successful development of new medications.

The widely prescribed antihypertensive agent lacidipine (LCDP), belongs to the dihydropyridine class of calcium channel blockers. LCDP shows greater antioxidant activity compared to other drugs in its class, potentially offering protective benefits against atherosclerosis. It is a highly lipophilic and light-sensitive drug, which affects its slow onset of action and stability, respectively [4]. LCDP belongs to BCS class II drugs, which are defined by inadequate aqueous solubility, thereby restricting their bioavailability (about 10%) when given orally [5, 6].

Lipid-based nanovesicular systems, particularly liposomes and niosomes, have been employed for the oral delivery of lipophilic and hydrophilic drugs. Yet they face drawbacks such as poor stability in the gastrointestinal tract, poor drug encapsulation and scaling up limitations. On the other hand, bilosomes are a new modified version of both liposomes and niosomes [7]. They are classified as self-assembled soft nanocarriers that are assembled from span series, non-ionic surfactants, and bile salts. These components are reported as harmless, biocompatible and biodegradable [8]. The addition of bile salts made the vesicle resist degradation by the GIT enzymes, gives the vesicle negative charge, providing stability and further enhanced drug absorption by the M-cells in the Peyer’s patch, making oral delivery more effective [9, 10]. The idea of using bilosomes stems from their ability to not only enhance the solubility and dissolution of poorly water-soluble pharmaceuticals, but also serving as a protective barrier, which is particularly beneficial for light-sensitive drugs like LCDP [11]. Due to these diverse advantages of bilosomes, they are preferred over conventional vesicular systems.

To boost the stability of the bilosome dispersion, it can be converted into a free-flowing powder form, referred to as probilosomes. This transformation, when compared to liquid preparation, can lead to improvement in handling properties, including ease of distribution, transfer, measurement and storage, while maintaining the integrity and stability of the formulation. Previous studies showed that probilosomes can have perfect restoring ability upon rehydration. After ingestion, it can naturally form the corresponding bilosomes in their liquid state [12].

Among the non-ionic surfactants most frequently used are Spans®. In this study, Span®60 was chosen as the primary non-ionic surfactant over Span® 20 and Span® 80, due to its relatively low hydrophile-lipophile balance value (HLB = 4.7), which facilitates the formation of stable vesicles, and its compatibility with bile salts, which is crucial for maintaining the structural integrity of bilosomes. Additionally, Span®60 has been reported to enhance the entrapment efficiency and stability of lipid-based vesicles, attributed to its long-saturated alkyl chain and high phase transition temperature, suggesting that more stable bilosomes with higher EE are formed when hydrophobicity increases [13].

Reinforcing the relevance of this study, a recent review by Mitrović et al. (2025) has extensively discussed the advantages of bilosomes in enhancing the oral bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs by providing enhanced bioavailability, regulated release, and lower adverse effects, thereby overcoming key formulation challenges [13].

The box-behnken design (BBD) is a rotational design that involves three factors, each at three levels. BBD is a powerful method in response surface methodology since it can estimate quadratic model parameters, develop sequential designs, identify model inadequacies, and include blocks. When comparing it to other surface response designs, BDD shows more benefits in terms of efficiency. Therefore, it requires fewer experimental runs for optimization in comparison to other models [14].

Since LCDP has poor aqueous solubility and limited oral bioavailability, there is quite a need for innovative formulation strategies to enhance LCDP dissolution and absorption. Bilosomes can offer a promising approach to circumvent these challenges through improving solubility, stability in the GIT, and intestinal uptake. Furthermore, the physical stability and practical utility of the formulation, bilosomes, can be achieved by converting bilosomes into a solid-state probilosomal powder through Freeze-drying. Upon ingestion, probilosomes rapidly rehydrate to form bilosomes in situ, thus combining the biopharmaceutical advantages of bilosomes with the storage, handling, and transport benefits of dry powder.

The novelty of this study lies in the systematic formulation and optimization of LCDP-loaded bilosomes using the ethanol-injection method, combined with BBD for robust optimization. Unlike previous bilosome formulations for LCDP or other BCS Class II drugs, this study addresses the critical challenge of enhancing bioavailability while maintaining formulation stability through the innovative transformation of bilosomes into probilosomal powder. This approach ensures improved oral delivery, stability, protection from photo-lability and practical utility, representing a significant advancement over conventional liquid bilosome formulations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

LCDP and cholesterol (CHO) were purchased from (Bide Pharmatech Co., China). Span®60 was purchased from (Loba Chemie Pvt., India) and sodium deoxycholate (SDC) from (Avonchem Ltd., UK.). Dialysis bag (MWCO14 kDa) was purchased from Special Product Laboratory, USA. All the chemical reagents used in the study were obtained from Chemical Laboratories Ltd, UK.

Methods

Preparation of LCDP bilosomes

LCDP-loaded bilosomes were prepared using the ethanol injection method [15, 16]. This method involves two phases: an organic phase and an aqueous phase. Briefly, LCDP, Span®60, and CHO were dissolved in preheated ethanol at 60 °C to form the organic phase. Separately, SDC was added to 15 ml of deionized water, also preheated to 60 °C, to form the aqueous phase. The organic solution was then injected into the aqueous solution at a controlled injection rate of 0.5 ml/min using a syringe with a 22G needle, while being stirred magnetically at 500 rpm using a hot plate magnetic stirrer (Joan lab, China). The turbidity of the solution confirmed the formation of bilosomes. The dispersion was then stirred until the ethanol evaporated completely and then allowed to cool to room temperature [17]. Finally, the dispersion was subjected to ultrasonic probe sonication for 5 min (50 seconds on, 10 seconds off) to obtain a fine-tuned dispersion with a small particle size. To confirm the formation of vesicles, 1 ml of the formulation was examined under a light microscope at varying magnifications (10X and 40X) [18].

Computer-based experimental design

A computer-based experimental design was utilized employing Design Expert® version 13.0.5.0 software. BBD was selected due to its efficiency in evaluating quadratic response surfaces with fewer experimental runs compared to other designs. BBD is advantageous when working with formulations prone to instability, as it avoids extreme combinations (corner points). The design included five center points to enhance accuracy and involved 17 experimental runs [19]. The BBD was utilized to investigate the influence of various formulation variables on different responses. The three independent variables were: (X1: Span® 60 amount), (X2: CHO amount) and (X3: SDC amount). The dependent variables (responses) were: (R1: PS), (R2: PDI) and (R3: EE%) as shown in table 1. Seventeen (17) formulas of LCDP bilosomes were designed using BBD as presented in table 2. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess the significance of the model, with a significance level of α = 0.05 (p<0.05), indicating statistical significance.

Table 1: Independent and dependent factors used in BBD for optimization for optimization

| Independent factors | Levels of variables | |

| Low (-1) | High (+1) | |

| X1= Span®60 (mg) | 75 | 300 |

| X2= Cholesterol (mg) | 25 | 70 |

| X3= SDC (mg) | 5 | 15 |

| Dependent variables and their ranges. | ||

| Dependent variables (Responses) | Constraints (In range) | |

| R1= Particle size (nm) | Minimum | |

| R2= PDI | Minimum | |

| R3= EE (%) | Maximum | |

Table 2: Preparation of LCDP bilosomes formulations suggested by the box-behnken design

| Formula | Factors levels in actual values | ||

| Span®60 (mg) | Cholesterol (mg) | SDC (mg) | |

| B1 | 300 | 47.5 | 5 |

| B2 | 187.5 | 47.5 | 10 |

| B3 | 300 | 25 | 10 |

| B4 | 75 | 70 | 10 |

| B5 | 187.5 | 70 | 15 |

| B6 | 75 | 47.5 | 5 |

| B7 | 187.5 | 47.5 | 10 |

| B8 | 187.5 | 70 | 5 |

| B9 | 300 | 70 | 10 |

| B10 | 187.5 | 47.5 | 10 |

| B11 | 75 | 25 | 10 |

| B12 | 300 | 47.5 | 15 |

| B13 | 187.5 | 25 | 5 |

| B14 | 75 | 47.5 | 15 |

| B15 | 187.5 | 47.5 | 10 |

| B16 | 187.5 | 25 | 15 |

| B17 | 187.5 | 47.5 | 10 |

Evaluation of box-behnken design runs

PS, PDI and EE% analysis of LCDP-loaded bilosomes were performed as described in the next sections.

PS and PDI analysis

The average PS and PDI of the prepared bilosomal formulations were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS). To ensure good sample clarity and minimize multiple scattering effects, each bilosomal dispersion (0.5 ml) was diluted with deionized water to a final volume of 10 ml, giving a dilution factor of 1:20. Deionized water was used as a dispersant to maintain vesicle stability. Measurements were performed at 25 °C using a Zetasizer Ultra-red label (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Worcestershire, UK). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate and the results were reported as mean PS (nm) and PDI [20, 21].

Entrapment efficiency measurement

EE% was assessed using an indirect approach, which involved determining the difference between the total amount of LCDP incorporated into the vesicles and the amount remaining in the aqueous phase after separating the supernatant from the nanovesicles [20]. This separation was accomplished by transferring 1.5 ml of bilosomes into an Eppendorf tube and centrifuging it at 15,000 rpm for one hour at 4 °C using a refrigerated centrifuge (HERMLE Benchmark refrigerated microcentrifuge, Germany). The concentration of unentrapped LCDP was measured spectrophotometrically (Shimadzu, model UV-1601 PC, Kyoto, Japan) by measuring the UV absorbance at a wavelength of 283 nm and calculating the corresponding concentration using a well-constructed calibration curve (у = 0.0405x-0.0033, R2 = 0.9992). To measure the total drug content, 1 ml of the bilosomal formulation was disrupted using 9 ml ethanol, which solubilized the encapsulated LCDP, allowing for complete drug release. This disrupted sample was then measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 283 nm using the same calibration curve. EE% was determined using the following equation:

Optimization of LCDP-loaded bilosomes

Design-Expert® version 13.0.5.0 software was employed to determine optimal bilosome formulation to be subjected for further evaluation studies. The selection was by done applying the desirability approach. The desirability values range from 0 (undesired) to 1 (desired) was employed [22]. The objectives of optimization were to obtain a formulation with minimal PS and PDI, alongside the highest EE%, as presented previously in table 1. The optimized LCDP-loaded bilosomes were evaluated for PS, PDI and EE% analysis using the same procedures described earlier in this manuscript.

ZP determination

The ZP of the optimized bilosomal formulation was determined by measuring electrophoretic mobility using a Zetasizer Ultra (red label) (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Worcestershire, UK) at 25 °C. For analysis, 0.5 ml of the formulation was diluted with deionized water to a final volume of 10 ml to ensure suitable conductivity and dispersion. Measurements were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed as the mean ZP (mV) [22].

Drug content determination

An exact volume of 1 ml, equivalent to 0.333 mg of LCDP, was measured and mixed with 9 ml of ethanol. The mixture was then sonicated in a sonication bath for 5 min. From this prepared solution, 1 ml was taken and subsequently diluted with ethanol and sonicated for 15 min. The resulting solution was analyzed for drug content using a UV/VIS spectrophotometer at λmax= 283 [23]. The drug content percentage in the bilosomes was determined using the following equation:

In vitro dissolution studies

Drug release from the optimized bilosome formulation (Bopt) was assessed using the dialysis bag method (MWCO14 kDa). A dialysis bag containing 3.75 ml of preparation was placed in a medium of 250 ml 0.1N HCl buffer (pH 1.2) containing 1% Tween 20 and maintained at 37±0.5 °C in a type II (paddle) USP apparatus. The rotation speed was set at 50 RPM. Dissolution medium of 0.1N HCl containing 1% Tween 20 was chosen to mimic the acidic gastric environment and enhance the solubilization of LCDP, a poorly soluble drug in aqueous media. The addition of 1% Tween 20 improves the wettability and dispersion of LCDP, promoting its release from the bilosomes [24]. This surfactant effect is comparable to the natural wetting and dispersing actions that occur in the GIT. Furthermore, surfactants with higher HLB values, such as Tween 20 (HLB = 16.7), aid in improving the release rates of hydrophobic drugs like LCDP [25]. Samples of 5 ml were taken after regular time intervals (5, 10, 15, 25, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90 and 120 min.) and replaced with fresh buffer. The samples were then filtered and analyzed using UV spectrophotometry at the specified λmax to construct the release profile of the drug from the bilosomes [26].

Preparation of physical mixture (PM)

The PM was created by thoroughly blending LCDP, Span 60, CHO, and SDC in the same proportion as the Bopt formula (5 mg, 75 mg, 47.5 and 10 mg, respectively). It was further compared to LCDP and PBopt in terms of FTIR, DSC and in vitro release profile.

Freeze-drying of optimized LCDP-loaded formula

For long-term stability, lyophilization of fresh Bopt formula was performed using lactose as cryoprotectants (5w/v %). Lactose was selected as the cryoprotectant based on its ability to form an intact, easy-to-redisperse cake with its ability to preserve vesicle structure, PS and EE% during lyophilization. Thus, lactose was deemed most suitable for preserving vesicle integrity during freeze-drying [27]. The lyophilization procedure included exposing the formulation to a primary freezing temperature of (-20 °C) for 24 h. Following this, the formulation underwent lyophilization (CHRIST Alpha 1-2 lD plus freeze-dryer, Germany) for an additional 24 h, with a condenser temperature set at-45 °C and maintained under a vacuum of 7 × 10-2 mbar [28]. The resultant dry, free-flowing probilosome powder (PBopt) was stored in a sealed container for subsequent analysis.

Evaluation of PBopt

The PBopt was subjected to several analyses as for the liquid bilosomes formula (Bopt). These analyses included PS, PDI and ZP, which were determined after resuspending amount of the powder in deionized water and the rest of the procedures are described in the previous sections. Also, EE% and drug content was measured for PBopt using the same procedure described in this manuscript. Additional studies specifically performed for the powder formula (PBopt) are described in detail in the coming sections. Furthermore, the release profile of PBopt was compared with the in vitro release of LCDP solution, Bopt, and PM using the same release conditions described previously in this work.

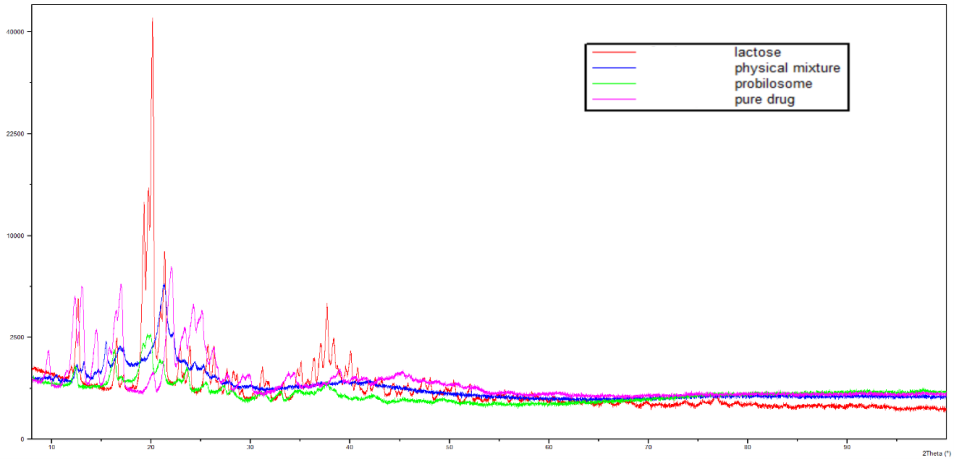

X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) studies

X-ray diffractometry (Shimadzu, Japan) was employed to acquire XRPD patterns of PBopt, PM, lactose, and LCDP. For pattern acquisition, the samples were subjected to X-ray radiation. The scanning angle was adjusted between 5° to 80° of 2θ, with the voltage and current maintained at 40 kV and 40 mA, respectively [21].

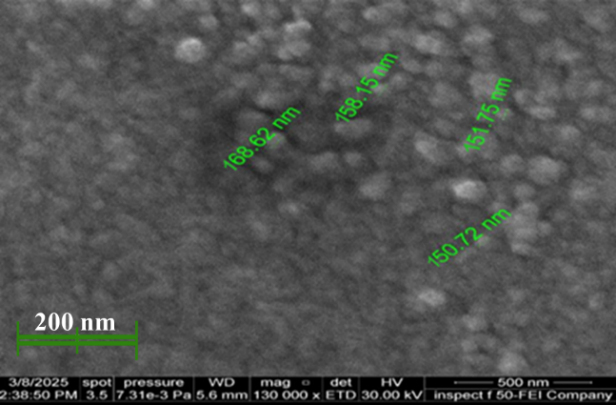

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM)

The surface morphology of the PBopt powder was examined using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) (Tescan, French). This technique was employed to visualize the vesicle structure and assess surface characteristics such as shape, size, and surface texture. A small amount of PBopt was mounted onto a metal stub using double-sided carbon tape and coated with a thin layer of gold under vacuum using a sputter coater. The sample was then imaged under FESEM at an appropriate accelerating voltage [29].

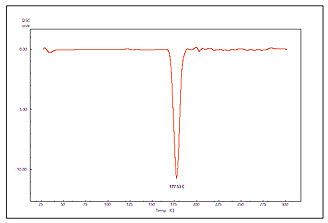

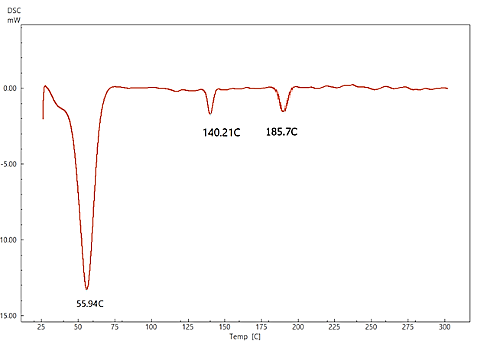

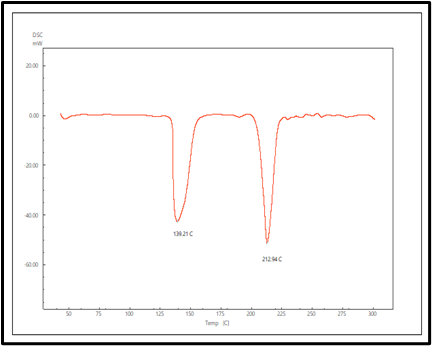

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The DSC (Shimadzu, Japan) was employed to examine the thermal properties of LCDP, CHO, Span®60, SDC, PM, lactose, and PBopt each separately. The samples were analyzed at a heating rate of 10 °C/min over a temperature range of 25 °C to 300 °C. The tests were conducted under a continuous nitrogen flow at a rate of 50 ml/min. This method facilitated the detection of any thermal fluctuations in the samples, potentially uncovering interactions between LCDP and the other excipients, if present [28].

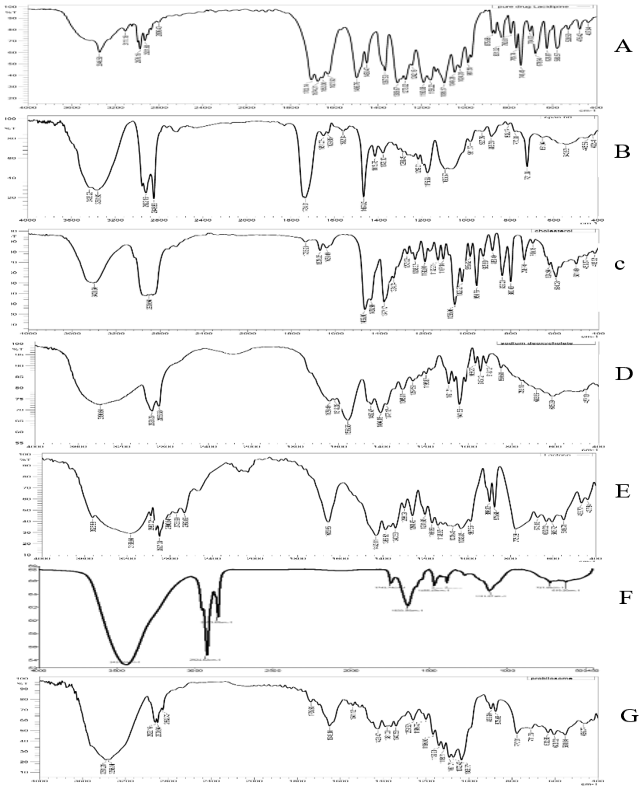

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The FTIR (FTIR-43000 Shimadzu, Japan) spectra of LCDP, CHO, Span®60, SDC, PM, Bopt and PBopt were obtained using infrared spectroscopy. Each sample was meticulously blended with KBr powder and subsequently compressed into transparent discs. The FTIR spectra was obtained within the range of 4000 to 400 cm-1, with a resolution of 4 cm-1 using the instrument [29].

Physical appearance and stability study

The PBopt powder was stored at room temperature for 90 days to evaluate stability in accordance with ICH guidelines for preliminary stability testing [30]. At specific time intervals (0, 30, 60 and 90 days), samples were withdrawn, hydrated with deionized water, and analyzed for PS, EE% and physical appearance [31].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Preparation and characterization of LCDP bilosomes

The ethanol injection method was a successful approach for preparing bilosomes, offering advantages such as rapidity, safety, and reproducibility [32]. The results of the 17 formulations, in terms of PS, PDI, and EE%, are presented in table 3, where most of the formulas are within the nanometer scale with different levels of entrapment efficiencies and homogeneity (PDI).

Table 3: Responses (PS, PDI and EE%) of the prepared LCDP-loaded bilosomes

| Response 1 | Response 2 | Response 3 |

| PS (nm)* | PDI* | EE %* |

| 249.3± 50.85 | 0.4000±0.156 | 95.70±5.37 |

| 217.5±12.43 | 0.2714±0.094 | 92.78± 2.51 |

| 262.5± 29.63 | 0.1854± 0.002 | 92.78± 1.67 |

| 205.0± 81.40 | 0.1831± 0.050 | 96.82± 3.61 |

| 211.9± 12.60 | 0.2929± 0.042 | 91.68± 1.95 |

| 225.0± 30.10 | 0.2198±0.021 | 98.40±6.92 |

| 205.7± 62.30 | 0.2265± 0.072 | 92.50± 1.41 |

| 237.1± 22.80 | 0.2715± 0.003 | 96.20±6.12 |

| 217.0± 44.90 | 0.2560±0.045 | 92.78± 1.39 |

| 206.6±70.21 | 0.2771± 0.028 | 91.80± 1.95 |

| 203.0± 39.30 | 0.2201± 0.060 | 94.14± 1.20 |

| 253.9± 65.20 | 0.4273± 0.053 | 89.00±1.04 |

| 248.7± 50.50 | 0.4456± 0.011 | 96.72± 2.91 |

| 192.5± 48.30 | 0.1749± 0.062 | 92.62± 1.76 |

| 210.0± 27.30 | 0.3461± 0.023 | 92.32± 1.60 |

| 244.6±67.30 | 0.3636±0.008 | 88.30±1.10 |

| 218.0± 37.80 | 0.3740± 0.002 |

|

*Experiments were done as triplicate with results represent mean±standard deviation.

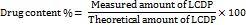

On the other hand, the light microscopy findings are presented in fig. 1, demonstrating the formation of spherical, uniformly distributed vesicles, indicating the successful assembly of the bilosomal components and substantiate the effectiveness of the ethanol injection method in the formulation of bilosomes. Also, the vesicles appeared to be well-dispersed without any sign of aggregation. The overall findings could indicate the stability of the formulation at this stage, prior to more detailed characterization of the nanostructure nature with advanced techniques like DLS and FESEM.

A B

Fig. 1: Optical microscope morphological pictures. A-under 40X, B-under 10X magnification

Analysis of Box-Behnken Design

The outcomes, R1: PS, R2: PDI, and R3: EE%, were individually examined and applied to linear, two-factor interaction (2FI), quadratic, and cubic models using linear regression. The model exhibiting the highest adjusted R² and prediction precision was chosen. As presented in table 4, the predicted R² values for all outcomes, except for PDI, demonstrate a reasonable correlation with the adjusted R², with discrepancies of less than 0.2. Nevertheless, the negative predicted R² value for PDI suggests that the overall mean functions as a more reliable predictor for this outcome [21].

Table 4: Output data of the box-behnken design

| Responses | R² | Adjusted R² | Predicted R² | Significant factors |

| PS | 0.9770 | 0.9475 | 0.9124 | X1, X2, X3 |

| PDI | 0.6425 | 0.1829 | -3.0259 | None |

| EE% | 0.9933 | 0.9848 | 0.9727 | X1, X2, X3 |

A

B

C

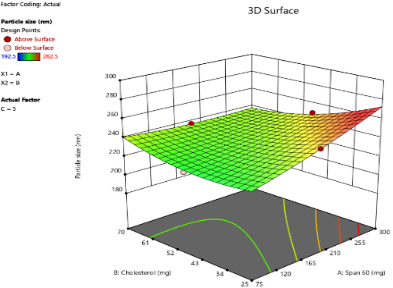

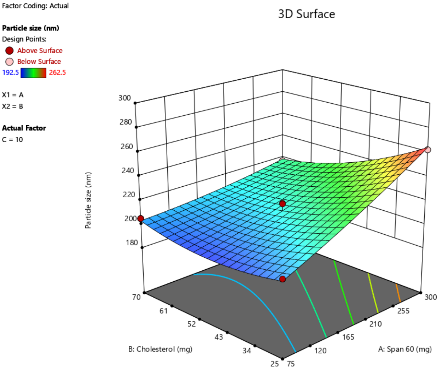

Fig. 2: Response surface 3D plots of independent variables effects on PS, as the amount of SDC increased from 5 mg to 10 mg to 15 mg. (A-5 mg SDC, B-10 mg SDC, C-15 mg SDC)

Effect of formulation variables on PS

The PS of oral bilosomes significantly impacts their performance and effectiveness, especially in terms of drug release rate. Smaller particles generally lead to faster release rates, which is particularly beneficial for drugs requiring a rapid onset of action, such as LCDP [13]. The bilosome vesicles prepared in this study were in the nanoscale range, with diameters varying from 192.5 nm to 262.5 nm, as presented in table 3. The impact of independent variables on PS is depicted in 3D plots illustrated in fig. 2. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the significance of independent factors on PS, with the findings demonstrating that Span®60 (X1), CHO (X2), and SDC (X3) have a significant influence on PS (p<0.05). Concerning the effect of Span®60 (X1) on PS, the results indicate a notably positive influence (p<0.0001), suggesting that an increase in the amount of Span®60 results in a larger PS. This can be attributed to the excess surfactant, which may induce vesicle aggregation or the formation of thicker bilayers, both of which contribute to an overall larger size. Similar findings have been reported by Mohanty et al. [33].

As for the effect of CHO (X2) on PS, an increase in CHO concentration led to an enlargement of the vesicles. CHO had a significant positive effect on PS (p = 0.0004), suggesting that its incorporation into the bilosome increases PS due to enhanced bilayer rigidity and reduced flexibility. Moreover, higher CHO content impedes lipid packing within the vesicles, resulting in a greater dispersion of the aqueous phase inside, which in turn causes an increase in PS. These results are consistent with the findings of previous study conducted by Sukanya Patil et al. [34]. SDC has a negative effect on PS (p = 0.0041), in other words, higher SDC amounts lead to smaller vesicles. The size-reducing effect is strongly linked to its ability to decrease surface tension and interfacial tension, leading to formation of smaller and more stable vesicles [35].

A

B

C

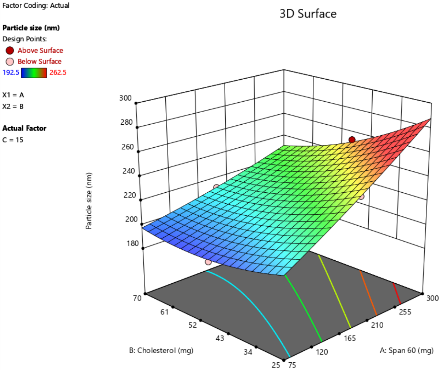

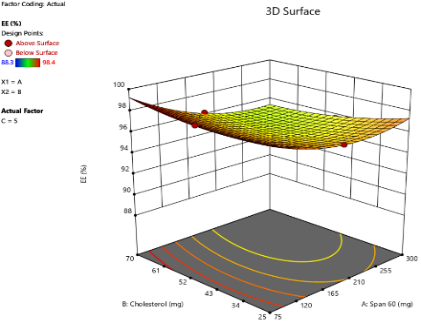

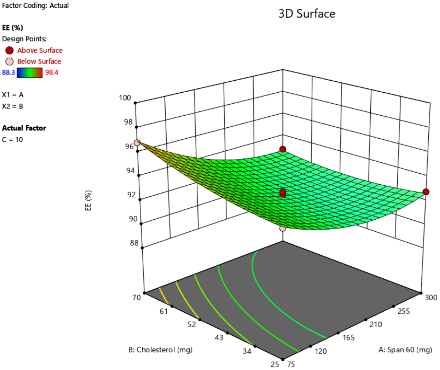

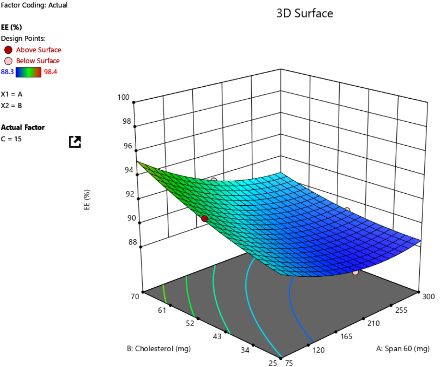

Fig. 3: Three-dimensional response surface plots showing the effect of independent variables on EE% at varying concentrations of SDC: (A) 5 mg, (B) 10 mg, and (C) 15 mg

Effect of formulation variables on PDI

PDI measures the uniformity of formulation. A PDI value close to 0 indicates a homogeneous population, while a PDI value close to 1 signifies a highly polydisperse system [36]. In this investigation, the PDI values varied between 0.1749 and 0.4456, suggesting monodispersed systems. The ANOVA analysis revealed that none of the independent variables had a significant impact on the PDI values. Comparable results have been observed in the study by Al-Sawaf et al. [22]. The negative predicted R2 (-3.0259) for the PDI model does not inherently signify weak model quality; rather, it may stem from low variability in PDI measurements instead of high variability. Since the model is unable to identify minor changes within uniform data sets (0.1749-0.4456), even small prediction errors can result in a negative R2, especially when the data points are highly consistent. The consistently low PDI values in this investigation were attributable to a rigorous experimental method with accurate measurements conducted in triplicate, which minimized random errors and enhanced reproducibility. Therefore, the negative predicted R2 should be interpreted as an indication of methodological precision rather than a lack of predictive accuracy [37].

Effects of formulation variables on EE%

The EE% of the prepared bilosome formulations ranged from 88.3% to 98.4%. ANOVA analysis results indicate that Span®60 (X1), CHO (X2), and SDC (X3) significantly affect EE% (p<0.05). The effect of Span®60 (X1) on EE% shows a positive correlation within an optimal range (p<0.0001), likely due to enhanced bilayer stability and reduced permeability. However, the 3D plot suggests that exceeding this optimal level does not further improve EE%. As shown in fig. 3, higher levels of SDC or CHO weaken the positive impact of Span®60 due to bilayer destabilization. Excessive Span®60 can disrupt the vesicle structure, thereby reducing EE%. Additionally, an interaction between Span®60 and SDC occurs, where SDC acts as an edge activator, enhancing bilayer flexibility. At low levels of SDC, Span®60 stabilizes the vesicle and improves EE%. However, at high SDC levels (>10 mg), excessive bilayer fluidity can lead to drug leakage, thereby reducing EE%. These findings are in agreement with a previous study conducted by Arunothayanun et al., suggesting that an optimal Span®60 amount balances drug rigidity and retention [38]. Regarding the effect of CHO on EE%, the 3D plot shows a negative effect (p = 0.0006), indicating that increasing CHO consistently decreases EE%. This negative impact is due to CHO filling gaps created by the improper arrangement of other lipid molecules. At higher CHO concentrations, the vesicle's ability to retain solutes diminishes, thus reducing EE% [39]. As for SDC’s effect on EE%, it shows both positive and negative effects (p<0.0001). Low levels of SDC (5 mg) enhance EE% by improving membrane flexibility and drug entrapment. However, high levels of SDC (>10 mg) decrease EE% by acting as a solubilizing surfactant, reducing vesicle compactness, promoting drug leakage, and lowering encapsulation efficiency [40, 41].

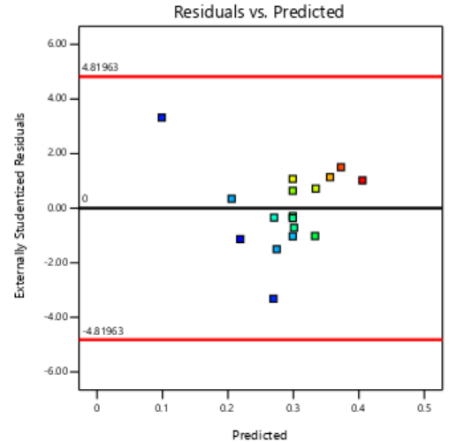

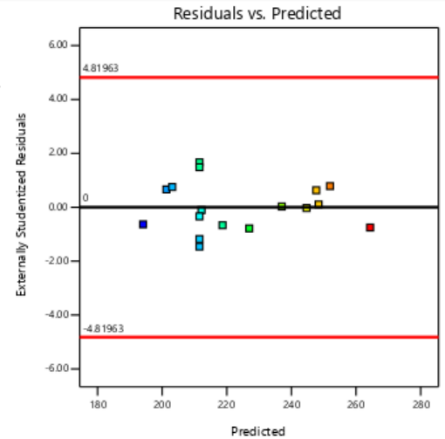

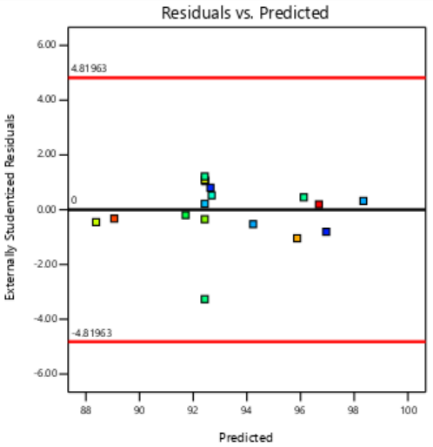

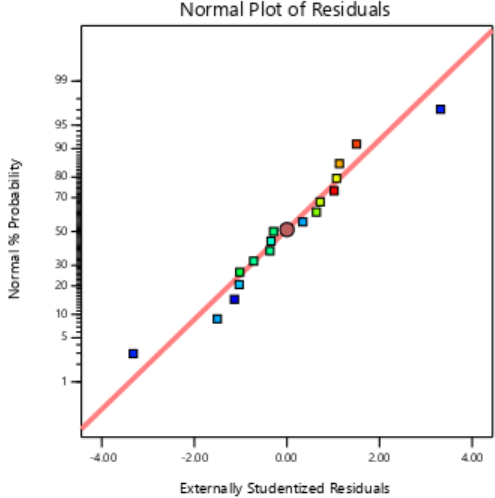

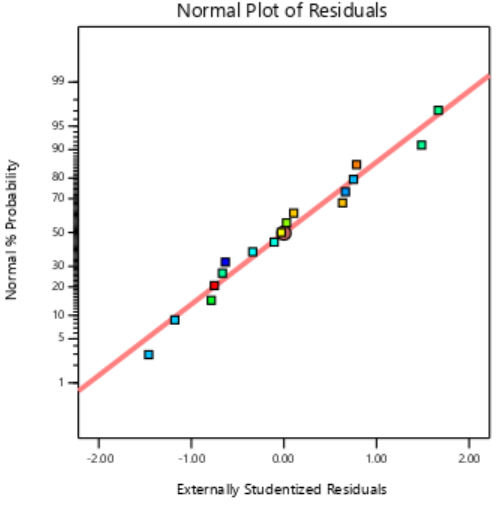

Diagnostic plots of PS, PDI and EE% responses

The residual diagnostics, including the Residuals vs. Predicted plot and the Normal Plot of Residuals, confirms the adequacy of the model assumptions. It is confirmed by the random scattered points between the red boarder lines in the Residuals vs. Predicted plot in fig. 4 which indicates homoscedasticity, while the linearity of the Normal Plot of Residuals illustrated in fig. 5 demonstrated normal distribution [42, 43].

PS PDI EE%

Fig. 4: Residual vs predicted plots of responses of PS, PDI and EE%

PS PDI EE%

Fig. 5: Externally studentized plots of responses of PS, PDI and EE%

Optimization of LCDP-loaded bilosomes

Design experts employed the desirability function to select the ideal bilosome formulation for subsequent investigation and assessment. The selected bilosome formulation and its corresponding desirability value, predicted and actual dependent variables (PS, PDI and EE%) are shown in table 5.

Trade-offs between PS, PDI, and EE% during optimization

During the optimization process of bilosome formulations, achieving a desirable balance between PS, PDI, and EE% involves significant trade-offs. An increase in Span®60 improves EE% due to vesicle bilayer stabilizing and reducing permeability, but it concurrently leads to larger vesicles due to vesicle aggregation and thicker bilayers, thereby increasing PS. CHO also contributes to larger PS and has a negative impact on EE% by reducing the vesicle's ability to retain the drug, owing to its rigidifying effect on the bilayer structure. In contrast, SDC reduces PS by lowering surface and interfacial tension, promoting smaller vesicles; however, while low concentrations of SDC improve EE% by enhancing membrane flexibility, higher concentrations lead to drug leakage and decreased EE% due to excessive bilayer fluidity. Interestingly, PDI remained largely unaffected by these formulation variables, indicating a consistently uniform system across different formulations. Thus, the formulation process involves a critical balancing act: maximizing EE% and minimizing PS without compromising vesicle stability or introducing excessive heterogeneity, which could indirectly impact PDI.

Table 5: Desirability and predicted vs. actual dependent variables of Bopt formulation

| Formula | Desirability | Predicted/actual PS | Predicted/actual PDI | Predicted/actual EE% |

| Bopt | 0.904 | 198.956/189.3 | 0.102/0.221 | 96.515/94.6 |

Statistical validation and adequacy of BBD models

The statistical analysis of the BBD models for PS, PDI, and EE% revealed satisfactory fitting parameters. Additionally, the lack-of-fit test for the BBD models of PS, PDI, and EE% showed non-significant p-values (p>0.05) with F-values of 0.2464, 0.2844, and 2.7300, respectively, indicating that the models adequately fit the experimental data.

Evaluation of Bopt

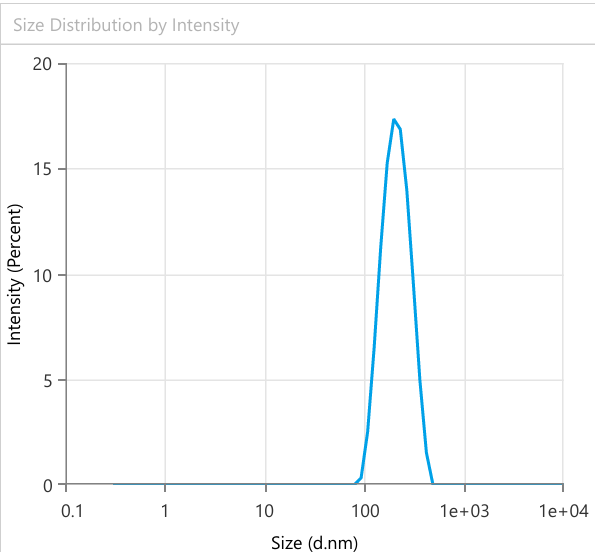

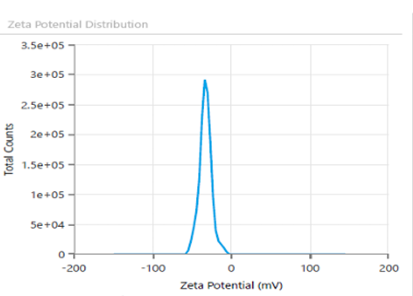

PS, PDI, EE% and ZP

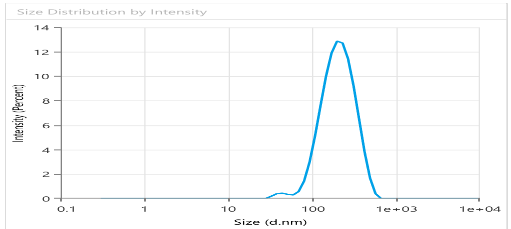

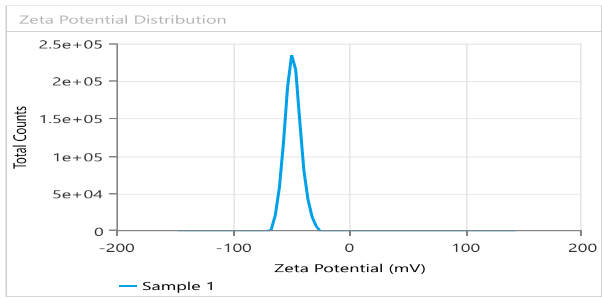

Fig. 6 provides PS =189.3± 12.4 nm, PDI = 0.221± 0.03 and EE% =94.6%±1.72, showing suitable results as predicted by the Design expert. It is important to control the PS in the nanosized range, since smaller particles are taken up more easily by cells and larger particles tend to aggregate. As for PDI value, getting nearer to 0 ensures uniform monodisperse system and predictable drug release. In like manner, low EE% indicates high loss of drug, making the formulation inefficient and high EE% denotes drug is successfully captured and contained within the bilosome particles. ZP is a crucial parameter for evaluating the stability of colloidal dispersion. It quantifies the electrostatic potential difference between the dispersed particles and the surrounding medium. A high ZP value suggests greater stability, as it reflects strong repulsive forces between the particles. In contrast, a low ZP value indicates instability, where attractive forces cause the particles to aggregate [44]. Fig. 7 illustrates ZP of-48.24 mV ±1.09, indicating high stability of the formulation. Possible source for the charge is the anionic surfactant (SDC) contributed to the formula, giving negative charge to the surface of the vesicles.

Fig. 6: Quantitative analysis of Bopt formula PS using dynamic light scattering

Fig. 7: ZP and surface charge analysis of Bopt formula evaluating stability

Drug content determination

The measured drug content was found to be 97.9 ± 0.5%, indicating a high level of drug incorporation in the formulation. This result suggests that LCDP was uniformly distributed throughout the bilosomal matrix, with minimal drug loss during the preparation process. The obtained value shows a good reconciliation with the theoretical drug content, reflecting on the effectiveness of the ethanol injection method in facilitating drug entrapment and incorporation into the bilosomal vesicles [45].

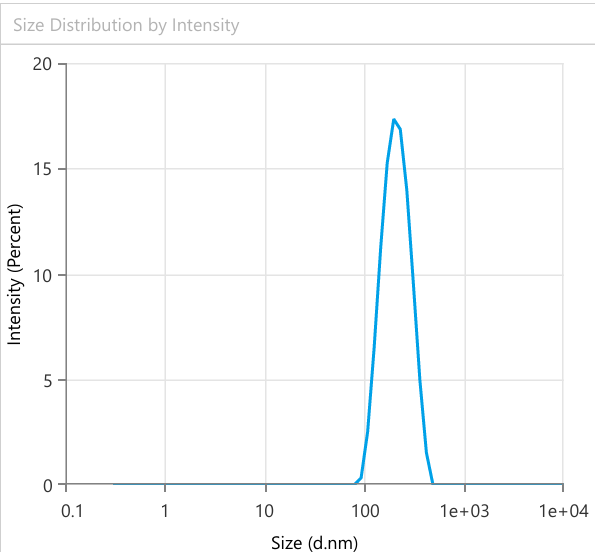

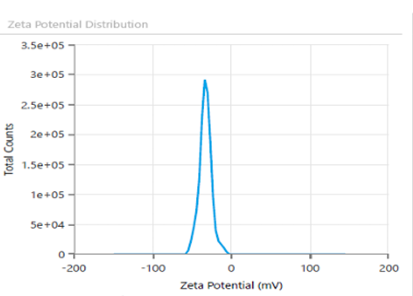

Evaluation of PBopt, PS, PDI, EE% and ZP

The lyophilized probilosome formulation was investigated after resuspension in deionized water. The PBopt formulation exhibited an EE% (93.7%), PS (198.3 nm), PDI (0.21), ZP (-25 mV±3.2) as shown in fig. 8. The reconstituted LCDP bilosomes prepared from PBopt powder showed no significant changes (p ˃0.05) in PS, PDI, ZP and EE %. Furthermore, the lyophilization process yielded 85.5%, based on the recovery of 758.7 mg of powder from an initial formulation weight of 887.5 mg, demonstrating the efficiency and practicality of the freeze-drying process. To assess the performance of PBopt, a comparison was made with the study by Guan et al. on gelatin-thickened freeze-dried bilosomes (pro-G-BLs) for oral cyclosporine a delivery. The PBopt formulation showed a PS of 198.3 nm, PDI of 0.21, and EE% of 93.7%, while the pro-G-BLs had a PS of approximately 200 nm and EE% of 83.7%. The superior EE% of PBopt can be attributed to the BBD-driven optimization, while the gelatin thickening in pro-G-BLs primarily enhanced stability during freeze-drying. Both formulations exhibited a narrow size distribution, indicating good homogeneity [12].

A B

Fig. 8: PS (A) and ZP (B) analysis of PBopt: implications for nanometer range and stability

Determination of drug content

It was found that there was no significant drug loss during lyophilization process by assessing drug content, which was found to be 92±5% indicating uniform distribution of LCDP in the entire bilosomal formulation.

X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) study

The XRD patterns of pure LCDP, PM, Lactose, and PBopt are presented in fig. 9. Characteristic peaks at 17, 22, and 25.12 (2θ) were observed in the XRD pattern of pure LCDP, indicating that the drug is in a crystalline state. The XRD profile of the PBopt formula displayed several characteristic peaks of pure LCDP, with slight shifts observed in some. Notably, some peaks present in pure LCDP were absent, and the intensity of the peaks in PBopt was significantly reduced compared to that of pure LCDP. These findings suggest that the drug in the probilosome formulation is amorphous compared to the pure drug. The amorphous state of the drug can enhance its solubility and bioavailability. Amorphous drugs typically demonstrate greater solubility and faster dissolution rates than their crystalline forms, resulting in improved oral bioavailability. Qian et al., documented correlation between reduced crystallinity and improved dissolution, reporting that reduced crystallinity plays a pivotal role in enhancing the drug’s dissolution behavior. Amorphous forms of drugs are thermodynamically more favorable for dissolution due to their higher energy state and lack of long-range molecular order, which promotes faster molecular dispersion in aqueous environments [46].

Fig. 9: Comparative XRPD analysis patterns of pure LCDP, PM, Lactose, and PBopt to investigate crystallinity

Fig. 10: Image of FESEM of PBopt formula showing bilosome vesicle in nanometer range

A B C

D E F

G

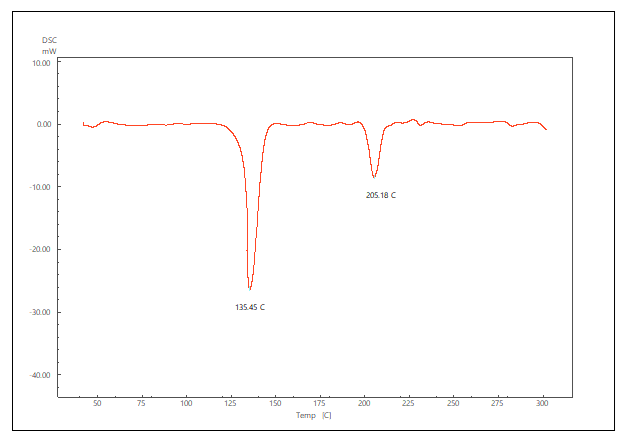

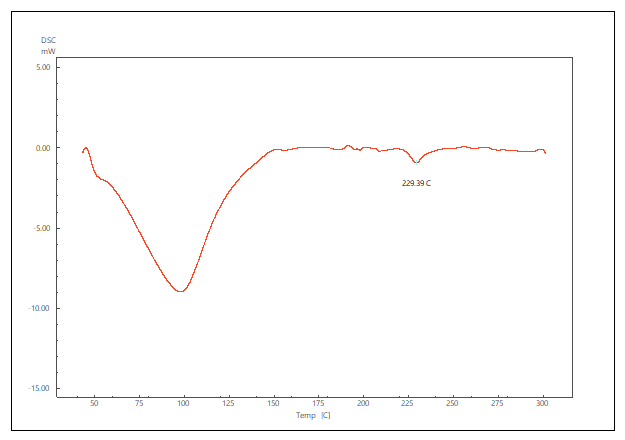

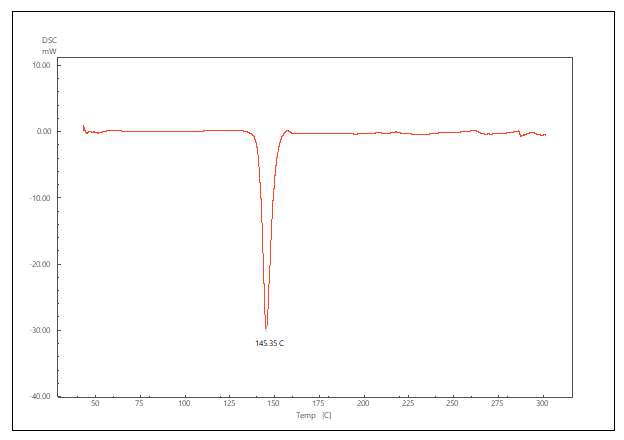

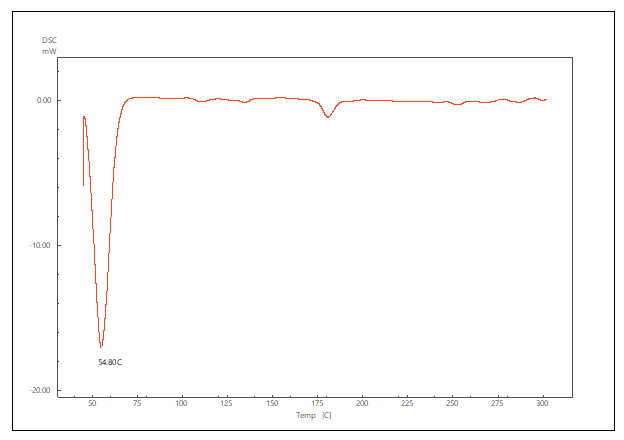

Fig. 11: DSC thermogram of pure LCDP, PM, PBopt, Span®60, CHO, SDC and lactose are shown (A, B, C, D, E, F and G), respectively

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM)

The FESEM images demonstrated that the LCDP probilosomes exhibited a spherical morphology with a consistent distribution, as shown in fig. 10. The size of the LCDP bilosomal vesicles were within the nanometer range (≈150.72–168.62 nm). However, the PS measured by DLS was larger (198.3 nm) than that observed in the FESEM images. This discrepancy is expected, as DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter, which includes layers of water surrounding the bilosome, resulting in larger sizes in solution, whereas FESEM analysis was conducted on dry particles [47].

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The DSC thermogram of pure LCDP, PM, PBopt, Span®60, CHO, SDC and lactose are shown in fig. 11. As depicted in the figure, pure LCDP exhibited a sharp endothermic peak at 177.53 °C, which corresponds to the drug's melting point. The absence of LCDP peak in the DSC thermogram of the probilosome provides robust evidence that LCDP is in the amorphous form and has been encapsulated within the bilosome vesicle. The two endothermic peaks in the probilosome DSC thermogram correspond to lactose, showing a reduction in intensity and melting points to 135.45 °C and 205.18 °C, likely due to dilution with other components. The DSC thermogram of the PM of PBopt shows distinct peaks for Span®60, lactose and LCDP, showing a reduction in intensity and melting points to 55.9 °C, 140.21 °C and 185.7 °C, which could also be attributed to dilution with other components. Notably, the absence of LCDP’s melting peak in the DSC thermogram of the PBopt formula aligns with the XRPD results, in which the characteristic crystalline peaks of LCDP were also absent, confirming its amorphous state. This transition enhances dissolution due to increased molecular disorder and thermodynamic energy, thereby improving solubility [46].

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR is a highly effective technique for identifying and assessing any potential chemical interactions between LCDP and excipients during probilosome formulation. The FTIR spectra fig. 12 of pure LCDP, Span®60, CHO, SDC, lactose, Bopt, and PBopt are presented to assess compatibility and structural integrity. Characteristic peaks at 3346.5 and 2976.16 cm⁻¹, corresponding to N-H and C-H stretching in pure LCDP. In both Bopt and PBopt formulations, these peaks exhibited reduced intensity and slight shifts due to hydrogen bonding. No substantial alterations and no new peaks appeared were observed in the major functional group regions pre-and post-lyophilization, with only minor variations in intensity and amplitude, confirming the compatibility of LCDP and the components used. Table 6 summarizes the key FTIR peaks across the samples, outcomes indicate the compatibility of the drug with the excipient used in the formulation of bilosomes.

Fig. 12: FTIR of pure LCDP, Span®60, CHO, SDC, lactose, Bopt, and PBopt. (A, B, C, D, E, F and G) respectively showing drug-excipient compatibility

Table 6: Summary of comparative FTIR analysis showing key peaks and their shifts

| Functional group/vibration | Pure LCDP (A) |

Span®60 (B) | CHO (C) | SDC (D) | Lactose (E) | Bopt (F) | PBopt (G) | Shift/observation |

| N-H stretching (amide) | 3346.5 cm⁻¹ | 3361.93 cm-1 | 3400.5 cm-1 | 3396.6 cm⁻¹ | 3350.4 cm⁻¹ | 3437.53 cm⁻¹ | 3356.1 cm⁻¹ | Slight upward shift (hydrogen bonding) |

| C-H stretching | 2976.16 cm⁻¹ | 2922.16 cm⁻¹ | 2900.9 cm⁻¹ | 2920.2 cm⁻¹ | 2987.08 cm⁻¹ | 2924.62 cm⁻¹ | 2922.1 cm⁻¹ | Slight shift from matrix imgding |

In vitro release studies

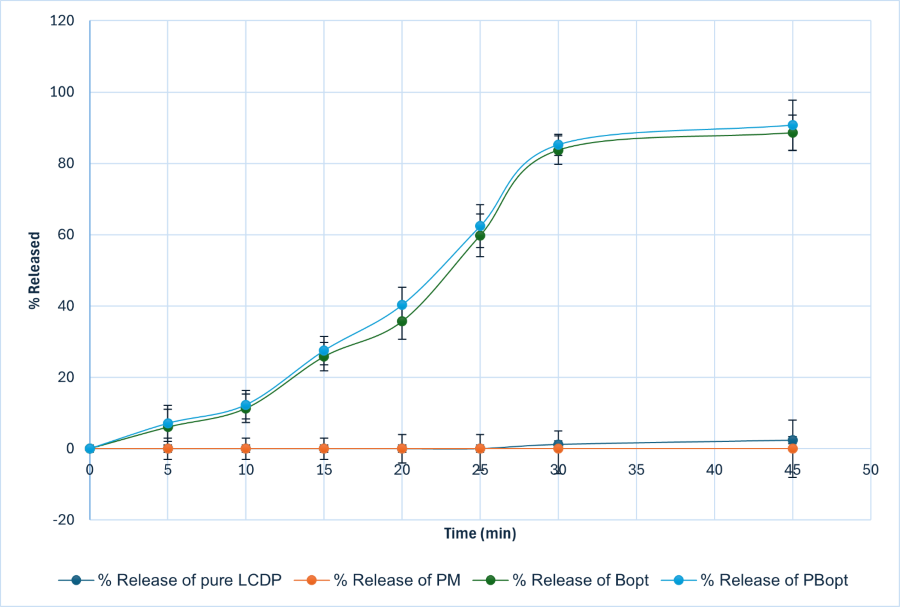

The in vitro release studies of LCDP were conducted in 0.1 N HCl+1% Tween 20 at 37±0.5 °C, and the results demonstrate a significant enhancement in drug dissolution when formulated as a bilosome. The release profile of raw LCDP was extremely poor, with only 3.62% released at 120 min, which is expected due to its high hydrophobicity and poor aqueous solubility. Similarly, the PM of LCDP with excipients showed negligible improvement, with a release of only 3.3% at 120 min, indicating that simple mixing does not enhance solubility or dissolution. In contrast, Bopt and PBopt exhibited a significant increase in dissolution, achieving 88.56% and 90.7% respectively, release within 45 min. The rapid dissolution in the first 30–45 min suggests that bilosomes released drug at slower rate, which is indication of strong and stable inner micellar core [48]. This is further supported by the role of SDC as an edge activator, which enhances bilayer flexibility and facilitates drug release. SDC, acting as a fluidizing agent, reduces the packing density of lipid molecules in the bilosome, making the bilayer more flexible and improving the drug’s release from the formulation [35]. On the other hand, these findings confirm that bilosomes significantly enhance LCDP dissolution, which is crucial for improving its oral bioavailability, given its classification as a BCS Class II drug. The reconstituted LCDP bilosomes prepared from PBopt powder did not show significant in vitro release characteristics compared with those of LCDP bilosomes before drying, as demonstrated in fig. 13. The study demonstrates that probilosome-based formulations have the potential to overcome the solubility limitations of LCDP, offering a promising approach for its effective oral delivery.

Table 7: Physical stability of PBopt demonstrating color consistency and retention of PS and EE% over 90 d along with drug leakage %

| Physical appearance | PS (nm) | EE% | Drug leakage% | |

| Day 0 |  White White |

198.3± 25.2 | 93.7± 1.4 | __ |

| Day 30 |  White White |

201.6± 17.1 | 93.3± 2.7 | 0.43 |

| Day 60 |  White White |

210.8± 15.9 | 92.8± 2.3 | 0.96 |

| Day 90 |  White White |

212.8± 10.3 | 92.77± 3.4 | 0.99 |

*value represent mean±standard deviation (n = 3).

Fig. 13: In vitro % release in 0.1 N HCl+1% Tween 20 at 37±0.5 °C of Pure LCDP, PM, Bopt and PBopt. Bopt and PBopt formulations exhibit enhanced release compared to pure LCDP and PM. Both Bopt and PBopt show similar release profiles, with closely aligned release percentages at all time points, reaching maximum releases of 88.56% and 90.7%, respectively.

Physical appearance and stability study

Stability studies are essential to evaluate the potential leakage of active pharmaceutical ingredients from the vesicles upon storage. Over the 90-d observation period, the PBopt powder retained a clear and consistent appearance, with no visible changes in color or morphology. Additionally, PS and EE% analysis showed no significant differences between freshly prepared (day 0) and stored (day 90) formula. This suggests that the formulation maintained its structural integrity and encapsulation efficiency, further supporting its stability under the given storage conditions. Outcomes are shown in table 6.

CONCLUSION

This study successfully developed and optimized LCDP-loaded bilosomes using the ethanol injection method combined with Box-Behnken design approach. The optimized formulation (Bopt) demonstrated favorable characteristics especially small PS, high EE%, and enhanced in vitro drug release properties. To improve physical stability and handling, the optimized bilosomal dispersion was lyophilized into a probilosomal powder (PBopt), which helped also in retaining the critical quality attributes during a three-month stability study. Findings confirms that bilosomes can serve as a promising nanovesicular carriers for enhancing the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs such as LCDP and alike drugs. The probilosome powder offers a scalable and patient-friendly alternative to liquid bilosomes, with potential for industrial adoption, thus enhancing the feasibility of translating the formulation into commercial pharmaceutical applications. Additionally, the transformation into a dry probilosomal form provides additional advantages in terms of stability, ease of handling, and pharmaceutical suitability, making this approach a nice strategy for future oral drug delivery systems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors express their gratitude to the College of Pharmacy, the University of Baghdad, and the Department of Pharmaceutics for providing all the necessary means to accomplish this study.

FUNDING

There is no funding to report.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization-Khalid Kadhem Al-Kinani, Farah Ayman Al-Shantir; Design-FA, KA; Supervision-KA; Formal analysis-FA; Methodology-FA; Writing original draft-FA; writing review and editing-KA; Critical review-KA; Data collection and/or processing-FA; Analysis and/or Interpretation-FA.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The authors report no financial or any other conflicts in this work.

REFERENCES

Alqahtani MS, Kazi M, Alsenaidy MA, Ahmad MZ. Advances in oral drug delivery. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Feb 19;12:618411. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.618411, PMID 33679401.

Vimalson DC, Parimalakrishnan S, Jeganathan NS, Anbazhagan S. Techniques to enhance solubility of hydrophobic drugs: an overview. Asian J Pharm. 2016;10(2):S67-S75. doi: 10.22377/ajp.v10i2.625.

Benet LZ. The role of BCS (Biopharmaceutics Classification System) and BDDCS (Biopharmaceutics drug disposition classification system) in drug development. J Pharm Sci. 2013 Jan;102(1):34-42. doi: 10.1002/jps.23359, PMID 23147500.

Luca MD, Ioele G, Spatari C, Ragno G. Photodegradation of 1, 4-dihydropyridine antihypertensive drugs: an updated review. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018 Jan 1;10(1):8. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2018v10i1.22562.

Dahash RA, Rajab NA. Formulation and investigation of lacidipine as a nanoemulsions. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2020 Jan 1;29(1):41-54. doi: 10.31351/vol29iss1pp41-54.

Moataz El Dahmy R, Hassen Elshafeey A, Ahmed El Feky Y. Fabrication optimization and evaluation of lyophilized lacidipine loaded fatty based nanovesicles as orally fast disintegrating sponge delivery system. Int J Pharm. 2024 Apr;655:124035. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.124035, PMID 38527564.

He H, Lu Y, Qi J, Zhu Q, Chen Z, Wu W. Adapting liposomes for oral drug delivery. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019 Jan;9(1):36-48. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.06.005, PMID 30766776.

Kumar GP, Rajeshwarrao P. Nonionic surfactant vesicular systems for effective drug delivery an overview. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2011 Dec;1(4):208-19. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2011.09.002.

Binsuwaidan R, Sultan AA, Negm WA, Attallah NG, Alqahtani MJ, Hussein IA. Bilosomes as nanoplatform for oral delivery and modulated in vivo antimicrobial activity of lycopene. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022 Aug 24;15(9):1043. doi: 10.3390/ph15091043, PMID 36145264.

Ismail A, Teiama M, Magdy B, Sakran W. Development of a novel bilosomal system for improved oral bioavailability of sertraline hydrochloride: formulation design in vitro characterization and ex vivo and in vivo studies. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2022 Jul 8;23(6):188. doi: 10.1208/s12249-022-02339-0, PMID 35799076.

Pucek A, Tokarek B, Waglewska E, Bazylinska U. Recent advances in the structural design of photosensitive agent formulations using soft colloidal nanocarriers. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Jun 24;12(6):587. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12060587, PMID 32599791.

Guan P, Lu Y, Qi J, Wu W. Readily restoring freeze dried probilosomes as potential nanocarriers for enhancing oral delivery of cyclosporine A. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2016 Aug 1;144:143-51. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.04.006, PMID 27085046.

Mitrovic D, Zaklan D, Danic M, Stanimirov B, Stankov K, Al Salami H. The pharmaceutical and pharmacological potential applications of bilosomes as nanocarriers for drug delivery. Molecules. 2025 Mar 6;30(5):1181. doi: 10.3390/molecules30051181, PMID 40076403.

Ferreira SL, Bruns RE, Ferreira HS, Matos GD, David JM, Brandao GC. Box-behnken design: an alternative for the optimization of analytical methods. Anal Chim Acta. 2007;597(2):179-86. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2007.07.011, PMID 17683728.

Kakkar S, Kaur IP. Spanlastics a novel nanovesicular carrier system for ocular delivery. Int J Pharm. 2011 Jul;413(1-2):202-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.04.027, PMID 21540093.

Shanta Taher S, Sadeq ZA, Al Kinani KK, Alwan ZS. Solid lipid nanoparticles as a promising approach for delivery of anticancer agents: review article. Mil Med Sci Lett. 2022 Sep 2;91(3):197-207. doi: 10.31482/mmsl.2021.042.

Abdelbary AA, Abd Elsalam WH, Al Mahallawi AM. Fabrication of novel ultradeformable bilosomes for enhanced ocular delivery of terconazole: in vitro characterization ex vivo permeation and in vivo safety assessment. Int J Pharm. 2016 Nov;513(1-2):688-96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.10.006, PMID 27717916.

Al Edhari GH, Al Gawhari FJ. Study the effect of formulation variables on preparation of nisoldipine loaded nano bilosomes. IJPS. 2023 Nov 4;32 Suppl:271-82. doi: 10.31351/vol32issSuppl.pp271-282.

Ameeduzzafar ANK, Alruwaili NK, Imam SS, Alotaibi NH, Alhakamy NA, Alharbi KS. Formulation of chitosan polymeric vesicles of ciprofloxacin for ocular delivery: box-behnken optimization in vitro characterization HET-CAM irritation and antimicrobial assessment. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020 Jul 5;21(5):167. doi: 10.1208/s12249-020-01699-9, PMID 32504176.

Sabri L, Khalil M. Impact of formulation variables on meloxicam spanlastics preparation. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2024 Dec 20;33(4):59-68. doi: 10.31351/vol33iss4pp59-68.

Al Sarraf MA, Hussein AA, Al Kinani KK. Formulation characterization and optimization of zaltoprofen nanostructured lipid carriers (Nlcs). Int J Drug Deliv Technol. 2021 Apr 1;11(2):434-42.

Al Sawaf OF. Novel probe sonication method for the preparation of meloxicam bilosomes for transdermal delivery: part one. Journal of Research in Medical and Dental Science. 2023;11(6):5-12.

Al Khalidi MM, Jawad FJ. Enhancement of aqueous solubility and dissolution rate of etoricoxib by solid dispersion technique. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2020 Jan 1;29(1):76-87. doi: 10.31351/vol29iss1pp76-87.

Chaudhari SP, Dugar RP. Application of surfactants in solid dispersion technology for improving solubility of poorly water soluble drugs. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2017 Oct;41:68-77. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2017.06.010.

Ching YC, Gunathilake TM, Chuah CH, Ching KY, Singh R, Liou NS. Curcumin/Tween 20-incorporated cellulose nanoparticles with enhanced curcumin solubility for nano-drug delivery: characterization and in vitro evaluation. Cellulose. 2019 Jun 29;26(9):5467-81. doi: 10.1007/s10570-019-02445-6.

Jassim ZE, Al Kinani KK, Alwan ZS. Preparation and evaluation of pharmaceutical cocrystals for solubility enhancement of dextromethorphan HBr. Int J Drug Deliv Technol. 2021 Oct 1;11(4):1342-9. doi: 10.25258/ijddt.11.4.37.

Jain S, Indulkar A, Harde H, Agrawal AK. Oral mucosal immunization using glucomannosylated bilosomes. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2014;10(6):932-47. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2014.1800, PMID 24749389.

Al gharani H, Al kinani K. Development and characterization of acemetacin nanosuspension based oral lyophilisates. J Res Pharm. 2025 Apr 8;29(2):626-38. doi: 10.12991/jrespharm.1664881.

Ali SK, Al Akkam EJ. Oral nanobilosomes of ropinirole: preparation compatibility and ex-vivo intestinal absorption study. J Adv Pharm Educ Res. 2023;13(4):8-15. doi: 10.51847/B7uaDLOWfq.

International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human use. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline Stability Testing of new Drug Substances and Products; 2003. p. 1-18.

Zafar A, Alruwaili NK, Imam SS, Alsaidan OA, Yasir M, Ghoneim MM. Development and evaluation of luteolin loaded pegylated bilosome: optimization in vitro characterization and cytotoxicity study. Drug Deliv. 2021 Jan 6;28(1):2562-73. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2021.2008055, PMID 34866534.

Du G, Sun X. Ethanol injection method for liposome preparation. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2622:65-70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-2954-3_5, PMID 36781750.

Mohanty D, Rani MJ, Haque MA, Bakshi V, Jahangir MA, Imam SS. Preparation and evaluation of transdermal naproxen niosomes: formulation optimization to preclinical anti-inflammatory assessment on murine model. J Liposome Res. 2020 Oct 1;30(4):377-87. doi: 10.1080/08982104.2019.1652646, PMID 31412744.

Patil S, Agnihotri J. Formulation development optimization and characterization of anti-fungal topical biopolymeric film using a niosomal approach. Int J Sci Res Arch. 2023 Jan 30;8(1):194-209. doi: 10.30574/ijsra.2023.8.1.0031.

Salem HF, Nafady MM, Ali AA, Khalil NM, Elsisi AA. Evaluation of metformin hydrochloride tailoring bilosomes as an effective transdermal nanocarrier. Int J Nanomedicine. 2022 Mar 17;17:1185-201. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S345505, PMID 35330695.

Ahmed S, Kassem MA, Sayed S. Bilosomes as promising nanovesicular carriers for improved transdermal delivery: construction, in vitro optimization, ex vivo permeation and in vivo evaluation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020 Dec 8;15:9783-98. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S278688, PMID 33324052.

Li J. Assessing the accuracy of predictive models for numerical data: not r nor r2, why not? Then what? PLOS One. 2017 Aug 24;12(8):e0183250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183250, PMID 28837692.

Arunothayanun P, Bernard MS, Craig DQ, Uchegbu IF, Florence AT. The effect of processing variables on the physical characteristics of non-ionic surfactant vesicles (niosomes) formed from a hexadecyl diglycerol ether. Int J Pharm. 2000 May;201(1):7-14. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00362-8, PMID 10867260.

Balakrishnan P, Shanmugam S, Lee WS, Lee WM, Kim JO, Oh DH. Formulation and in vitro assessment of minoxidil niosomes for enhanced skin delivery. Int J Pharm. 2009 Jul;377(1-2):1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.04.020, PMID 19394413.

Zafar A, Alruwaili NK, Imam SS, Hadal Alotaibi N, Alharbi KS, Afzal M. Bioactive apigenin loaded oral nano bilosomes: formulation optimization to preclinical assessment. Saudi Pharm J. 2021 Mar;29(3):269-79. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2021.02.003, PMID 33981176.

Tripathi M, Gharti L, Bansal A, Kaurav H, Sheth S. Intranasal mucoadhesive in situ gel of glibenclamide loaded bilosomes for enhanced therapeutic drug delivery to the brain. Pharmaceutics. 2025 Feb 4;17(2):193. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics17020193, PMID 40006560.

Meng J, Sturgis TF, Youan BB. Engineering tenofovir loaded chitosan nanoparticles to maximize microbicide mucoadhesion. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2011 Sep;44(1-2):57-67. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2011.06.007, PMID 21704704.

Abul Kalam M, Khan AA, Khan S, Almalik A, Alshamsan A. Optimizing indomethacin loaded chitosan nanoparticle size encapsulation and release using box–behnken experimental design. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016 Jun;87:329-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.02.033, PMID 26893052.

Elkomy MH, Eid HM, Elmowafy M, Shalaby K, Zafar A, Abdelgawad MA. Bilosomes as a promising nanoplatform for oral delivery of an alkaloid nutraceutical: improved pharmacokinetic profile and snowballed hypoglycemic effect in diabetic rats. Drug Deliv. 2022 Dec 31;29(1):2694-704. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2022.2110997, PMID 35975320.

Khudhair AS, Sabri LA. Preparation and evaluation of topical hydrogel containing ketoconazole loaded bilosomes. Acta Pharm Sci. 2024;62(4):762-77. doi: 10.23893/1307-2080.APS6250.

Qian K, Stella L, Jones DS, Andrews GP, Du H, Tian Y. Drug rich phases induced by amorphous solid dispersion: arbitrary or intentional goal in oral drug delivery? Pharmaceutics. 2021 Jun 15;13(6):889. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13060889, PMID 34203969.

Egla M, Nawal Ayash Rajab. Sericin based paclitaxel nanoparticles: preparation and physicochemical evaluation. Iraqi Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2025;33(4SI);169-78. doi: 10.31351/vol33iss(4SI)pp169-178.

Islam N, Zahoor AF, Syed HK, Iqbal MS, Khan IU, Abbas G. Improvement of solubility and dissolution of ebastine by fabricating phosphatidylcholine/ bile salt bilosomes. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2020;33(5Suppl):2301-6. PMID 33832904.