Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 454-464Original Article

DESIGN AND EVALUATION OF NEOMYCIN SULFATE-LOADED SOLID LIPID NANOPARTICLES (SLNs) FOR OCULAR ADMINISTRATION

VEEKSHA S. SHETTY, SANDEEP DS*

Nitte (Deemed to be University), NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (NGSMIPS), Department of Pharmaceutics, Mangalore, India

*Corresponding author: Sandeep DS; *Email: sandypharama@gmail.com

Received: 17 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 02 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The current study aimed to formulate and evaluate solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) loaded with Neomycin Sulfate for ocular administration for the management of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Methods: The formulation of Neomycin Sulfate-loaded SLNs was carried out using the solvent evaporation and ultrasonication methods. Optimization of SLNs was performed using a 32 full factorial statistical design, and the optimized batch of SLNs was evaluated for various parameters.

Results: The optimized formulation exhibited a mean particle size of 178.2±2.23 nm with an entrapment efficiency of 85.6%, which was in good agreement with the predicted values obtained using Design Expert software. The formulation revealed a sustained drug release pattern with a maximum drug release of 82.11±0.34% lasting 8 h with Higuchi's drug release kinetics mechanism. The Hen’s egg test-Chorioallantoic membrane (HET-CAM) assay revealed that the optimized formulation was non-irritating and non-toxic for ocular use. Additionally, histopathological analysis showed no structural damage to the cornea, confirming the formulation’s safety for ocular administration. Short-term stability studies on the optimized formulation demonstrated that it remained stable, with no notable changes in the assessed parameters over 3 mo.

Conclusion: From the above outcomes of the study results, we conclude that Neomycin sulfate-loaded SLNs could be a potential drug delivery approach for the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis in the eye.

Keywords: SLNs, Neomycin sulfate, DoE, Particle size, Zeta potential, HET-CAM test

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54617 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

The eye’s intricate anatomical and physiological barriers, such as the aqueous humor-blood and blood-retinal barriers, can hinder effective drug delivery to the retina, limiting treatment efficacy. However, recent advancements in nano-delivery systems show promise in overcoming these barriers, enhancing biocompatibility, stability, efficiency, and sustainability while also enabling better control of ocular drug delivery [1].

Antibiotics used in ophthalmic treatments should efficiently control bacterial infections while requiring minimal administration frequency and dosing, ultimately improving patient outcomes. Commonly used antibiotics for eye infections include tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and penicillin. The growing issue of antibiotic resistance underscores the need to develop alternative drug delivery systems [2].

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) have become increasingly popular within nanoscale drug delivery systems due to their distinctive features and benefits. SLNs have revolutionized drug carrier systems with their versatility and efficiency in encapsulating and delivering active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Composed of solid lipids and surfactants, SLNs offer significant advantages over traditional drug carriers, such as liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles, due to their inherent properties [3, 4].

Neomycin sulfate, an aminoglycoside antibiotic, exhibits broad-spectrum activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. It exerts its antibacterial effect by binding to the 30s ribosomal subunit, thereby inhibiting protein synthesis in bacterial cells [5].

This study focused on the formulation and characterization of Neomycin sulfate for ocular administration. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) containing Neomycin sulfate were prepared using solvent evaporation and ultrasonication methods with glyceryl monostearate (GMS) serving as the lipid matrix. Optimization of SLNs was conducted using a 32 full factorial design, which considered GMS concentration and sonication time as independent variables. Their impact on dependent factors, such as particle size and entrapment efficiency, was evaluated. Numerical optimization was performed using response surface methodology (RSM) with Design Expert software [6, 7].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Neomycin sulfate pure API was procured from Kemwell Biopharma Pvt. Ltd, Bengaluru, India. Glyceryl monostearate (GMS), Pluronic F-127, chloroform, methanol, and Sodium chloride were obtained from Loba Chemie, Mumbai, India.

Methods

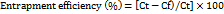

FTIR spectral study

FTIR spectral analysis was conducted using an Alpha Bruker IR Spectrophotometer to evaluate the compatibility between Neomycin sulfate and the lipid carrier. Spectra of the pure drug, lipid, and their physical mixture were recorded and compared with reference standards. Key functional group peaks were identified to assess potential interactions, ensuring that the drug and lipid were compatible or not [8].

Optimization of neomycin sulfate-loaded SLNs

The SLNs of Neomycin sulfate were optimized while targeting lipid concentration (mg) and sonication time (min) as independent factors at three distinct levels. The impact of such variables was evaluated on the particle size (nm) and entrapment efficiency (%) as dependent variables by employing a second-order polynomial equation generated by polynomial regression using a quadratic response surface design. This statistical method, applied with Design Expert® software (Version 11.03.0 64-bit, Stat-Ease, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), explored the relationships between the independent variables and the selected dependent factors. To optimize the formulations, response surface methodology (RSM) was employed, leveraging statistical and mathematical methods. This method optimizes numerical parameters influencing the response surface and quantifies the relationships between these parameters at different levels through the resulting response surfaces [9].

The suggested model can be elucidated through a quadratic equation that demonstrates the impact of coefficients, interactions, and polynomial terms [10, 11].

Y = b0+b1X1+b2X2+b12X1X2+b11X12+b22X22+. (Eq. 1)

Where Y represents the observed outcome corresponding to each combination of factor levels, b0 is an intercept, b1 to b22 represent regression coefficients derived from the empirical data of Y obtained through experimentation, and A and B represent the coded levels of independent variables. The different levels of independent factors used in formulation trials for optimizing Neomycin sulfate SLNs are represented in table 1.

Table 1: 32factorial design variables for Neomycin sulfate loaded Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs)

| Factors | Levels, actual (coded) |

| -1 (low) | |

| Independent variables | 30 |

| A = Lipid concentration(mg) | |

| B = Sonication time (min) | 15 |

| Dependent variables | |

| R1= Particle size(nm) | Minimum |

| R2= Entrapment efficiency (%) | Maximum |

Preparation of neomycin sulfate SLNs

Using the solvent evaporation/ultrasonication method, the SLNs of Neomycin sulfate were formulated. At first, GMS was dissolved in an equal ratio (1:1) mixture of methanol and chloroform. This lipid solution was added dropwise to a 5% aqueous solution of poloxamer 407, in which the drug had been previously dissolved, followed by magnetic stirring at a temperature of 60-70 °C to facilitate the evaporation of the organic solvents. After the evaporation, heating was stopped, and the magnetic stirring was continued for about 6 h to allow pre-size reduction of the SLN dispersion before ultrasonication. The SLN dispersions were then sonicated for varying periods using a probe sonicator set to a fixed amplitude and frequency. The final SLN dispersion was filtered through syringe filters with a membrane pore size of 0.22 µm to retain the sterility of the formulation [12].

Evaluation of Neomycin sulfate SLNs

Particle size and PDI

The particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) of all the SLNs, including the optimized formulation, were assessed using dynamic light scattering (DLS) with a Malvern Zetasizer. Prior to each measurement, the system was allowed to equilibrate, and the samples were diluted with ultra-pure water [13].

Entrapment efficiency (%)

Using a cold centrifuge, the entrapment efficiency (%) of all the formulated and optimized SLNs of Neomycin sulfate was measured using the centrifugation method. The SLNs were subjected to centrifugation at 12000 rpm for about 40 min, and the supernatant liquid was filtered and diluted with simulated tear fluid (STF). The concentration of the free drug was measured by a UV spectrophotometer. The entrapment efficiency of the drug was estimated using the following formula [14].

Where Ct is the amount of total drug and Cf is the concentration of the unentrapped drug.

Zeta potential measurement

Using a Malvern Zetasizer, the zeta potential of the optimized formulation was assessed at 25ºC with 90° detection angle following dilution with ultra-pure water [15].

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis

The morphological characteristics of the optimized formulation were examined using TEM analysis. For sample preparation, a droplet of SLN dispersion was placed onto a 400-mesh carbon-coated copper grid, with excess solution carefully blotted using tissue paper. Staining was performed using 2% w/v of phosphotungstic acid. After air-drying at ambient temperature, the samples were imaged at 4000X magnification under an accelerating voltage of 200 kV [16].

pH

A digital pH meter was used to measure the pH of the optimized SLNs of Neomycin sulfate [17].

Drug content

Using UV spectroscopy, the drug content of the optimized formulation was estimated. The procedure involves the dilution of 1 ml of formulation with 100 ml of STF to achieve a 100µg/ml concentration. The diluted samples were analyzed, and the obtained absorbance was recorded as a percentage [18].

Drug release study

The drug release study of the optimized formulation was conducted using Franz diffusion cell apparatus. The assembly included a donor chamber and a receptor chamber to enable the permeation of SLNs across a commercial semi-permeable cellophane membrane. 1 ml of formulation was placed on the donor chamber, which was sealed with a cellophane membrane. The receptor compartment contained 25 ml of simulated tear fluid (STF), continuously stirred by a magnetic stirrer. The assembly was maintained at a temperature of 37±0.5 °C with constant stirring at 50 rpm. At predetermined intervals (0.5,1,2,3,4,5,6,7 and 8 h), 1 ml samples were withdrawn from the receptor chamber and replaced with an equal volume of fresh STF. The withdrawn samples were diluted with 10 ml of STF and analyzed with a UV spectrophotometer at 305 nm. The cumulative drug release percentage (% CDR) was estimated from the data obtained. Additionally, curve fitting analysis was performed to generate the drug release profile [19, 20].

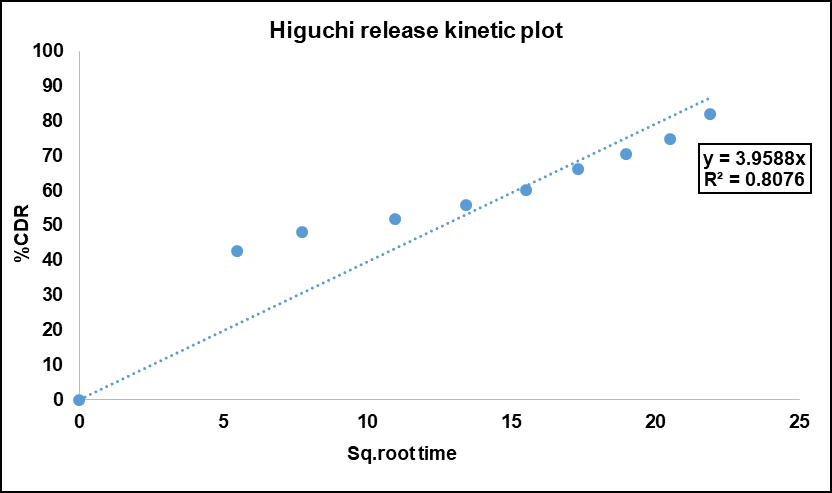

Drug release kinetics

The drug release mechanism was investigated by analyzing the release data with zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, and Korsmeyer-Peppas kinetic models. The model demonstrating the highest R2 value was identified as the principal release mechanism [21, 22].

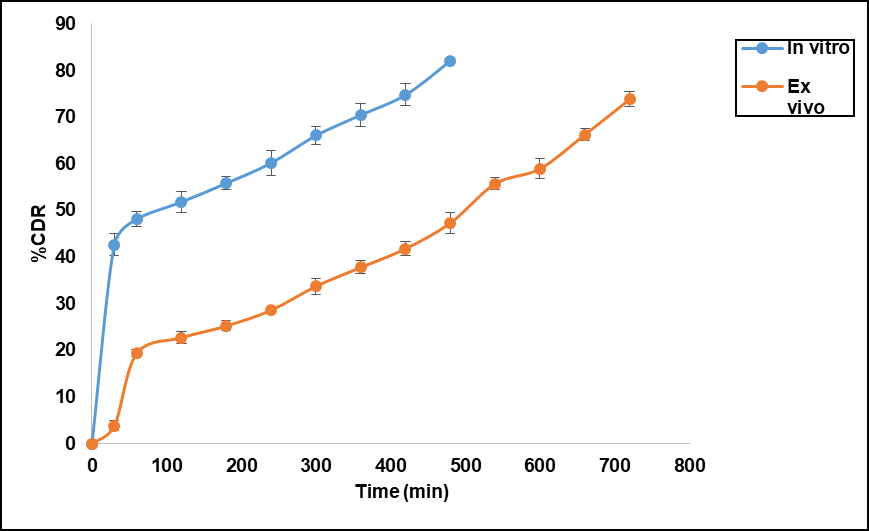

Ex vivo permeation studies

To investigate the permeation of the formulation through the corneal membrane, goat cornea was used. The entire goat eyeball was obtained from a slaughterhouse and transported to the lab in normal saline for preservation. After separating the cornea, it was rinsed with cold normal saline. The cornea was then soaked in freshly prepared STF and left overnight to facilitate easier permeation of the formulation. The permeation study was conducted using the Franz diffusion cell, following the same procedure as the drug release study, with the dialysis membrane replaced by the corneal membrane. The study was carried out for 12 h [23].

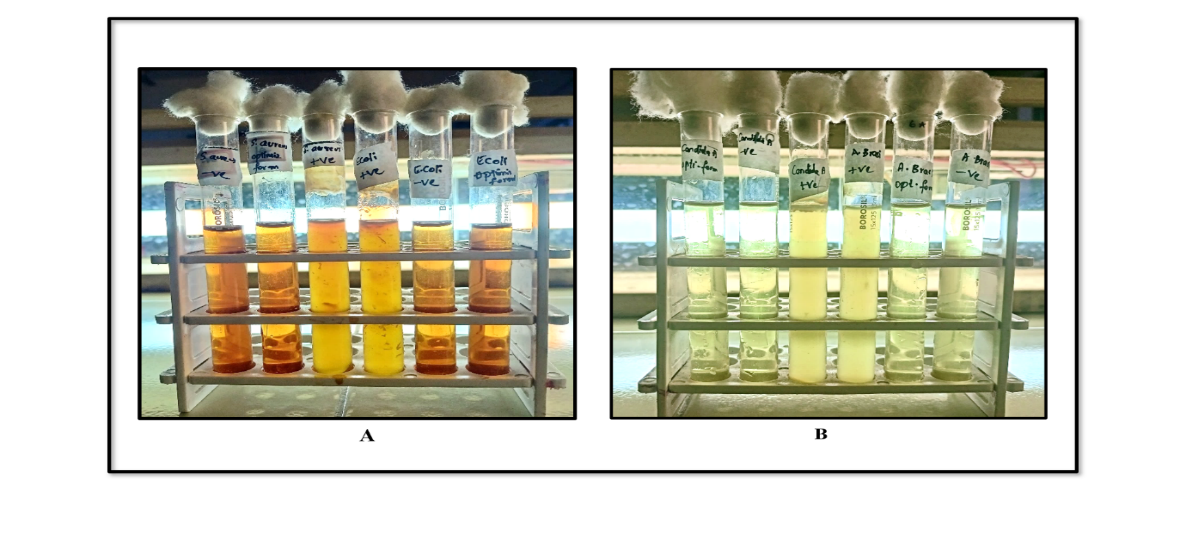

Sterility test

Sterility test was conducted using the direct inoculation method as specified by the Indian Pharmacopoeia (IP) procedure. The inoculated media underwent a 7 d incubation period, followed by a visual examination for microbial growth. The sterility of the formulation was assessed by comparison with positive and negative controls [24].

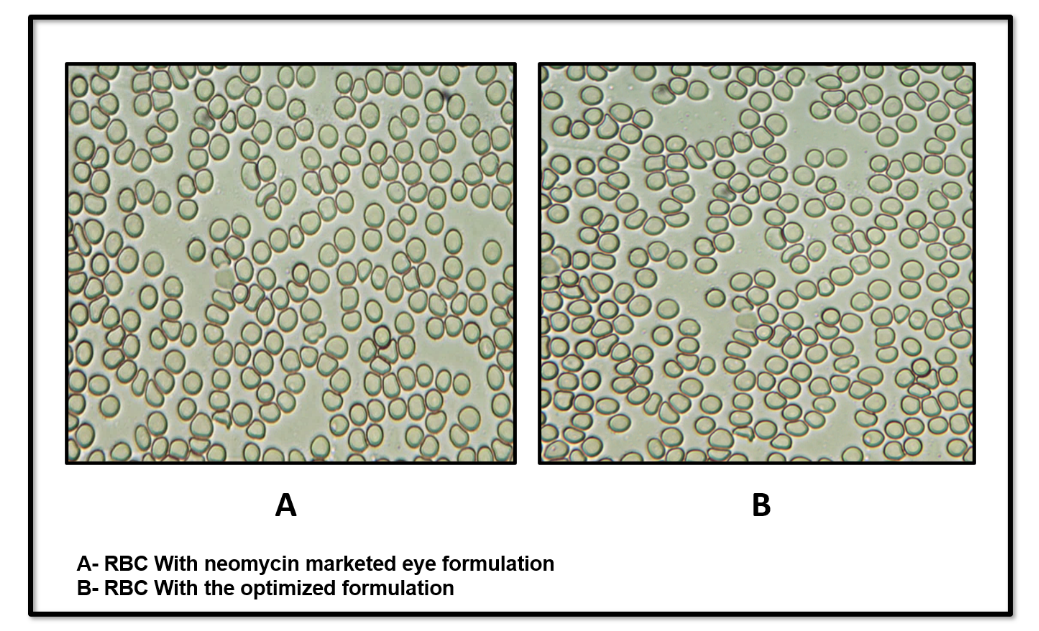

Isotonicity test

To assess the isotonicity, the optimized formulation was mixed with fresh human blood on a glass slide, smeared, and analyzed using a Biovis particle size analyzer. Commercial eye drops were similarly tested as a reference standard. RBC morphology was microscopically examined for osmotic effects (swelling, bulging of RBCs) by comparing the test sample with the reference formulation [25].

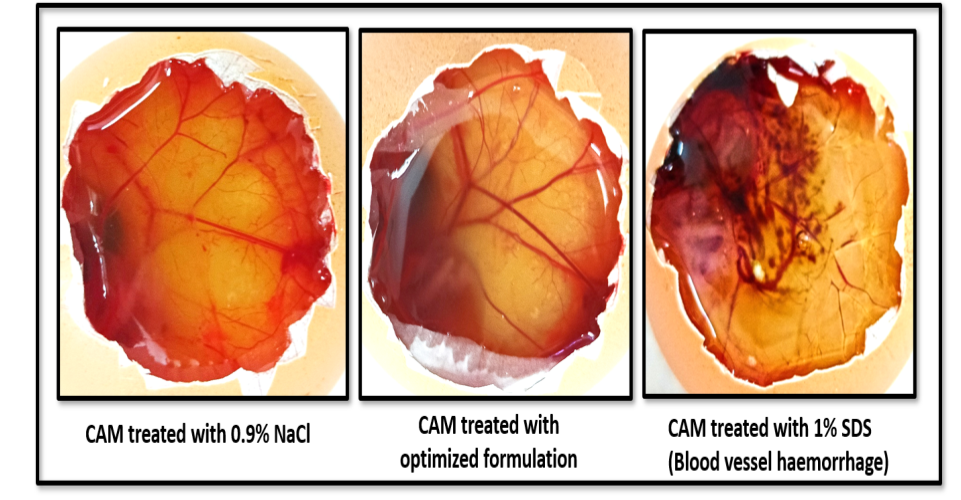

In vitro ocular irritancy evaluation by Hen’s egg test-chorioallantoic membrane (HET-CAM) test

Freshly collected white Leghorn chicken eggs, weighing 50-60 g and not older than 7 days, were selected for the study. Eggs with physical damage or cracks were excluded. The eggs were categorized into 3 groups, each containing 3 eggs. The negative control group received 0.3 ml of normal saline (0.9% NaCl), the test group was treated with 0.3 ml of optimized formulation, and the positive control group was exposed to 0.3 ml of 1% Sodium dodecyl sulphate (1% SDS) to induce potential irritation. All the eggs were incubated at 37±0.5 °C and 58±2% relative humidity, with manual rotation five times daily for about 8 days. After confirming embryonic development by candling, the eggs were positioned large-end up without rotation for a complete 24 h. Test solutions were applied to the CAM, and the irritation effects, such as haemorrhage, coagulation, and vascular lysis, were observed for 5 min [26].

The formula for determining the irritation score (IS) is provided below, along with the corresponding values and their inferences in table 3.

IS = ( ) X 5+(

) X 5+( ) X 7+(

) X 7+( ) X 9

) X 9

Where,

H-Hemorrhage

L-Lysis of blood vessels

C-Coagulation

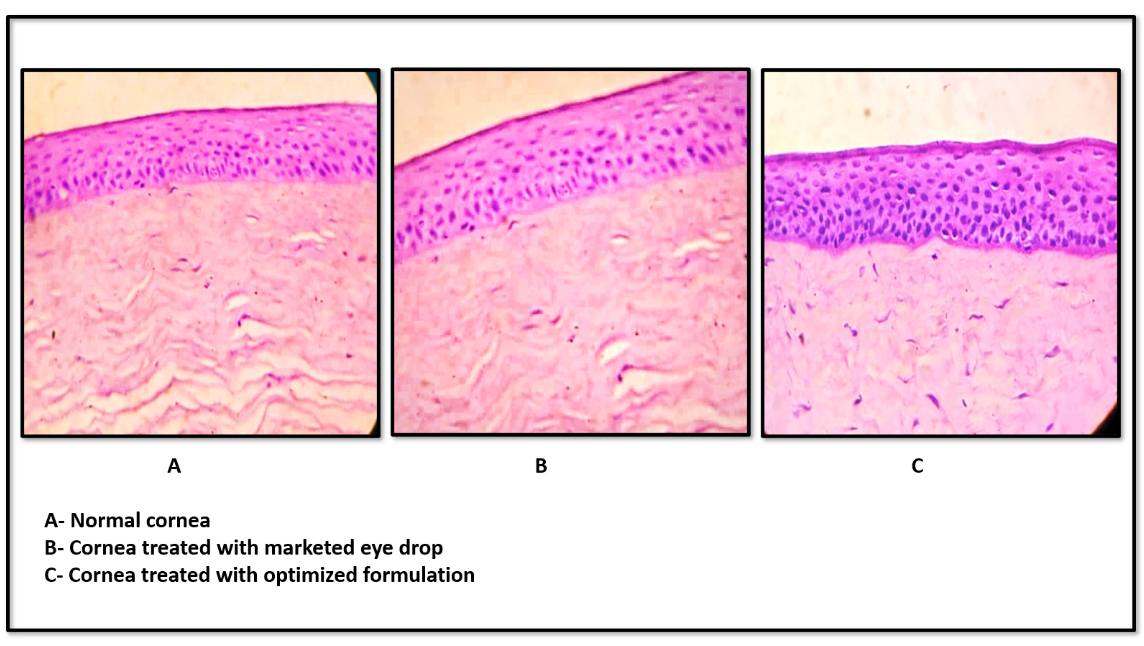

Ex vivo corneal histopathology study

The corneas were carefully removed from the goat eyeballs, following the same procedure used in the ex vivo drug permeation study. The excised corneal tissue was then immersed in normal saline (control), marketed neomycin sulfate eye drops (standard), and the optimized formulation (test) for 8 h. Post-treatment, corneal tissues were cryosectioned into 40 µm transverse slices using a Leica cryotome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), dehydrated through an ethanol series, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Slides were examined under 40X magnification using an inverted microscope, with histopathological analysis focusing on tissue integrity and morphological changes [27].

Table 3: Irritation score value with inference for HET-CAM Test

| Irritation score | Inference |

| 0-0.9 | No irritation |

| 1-4.9 | Weak irritation |

| 5-8.9 | Moderate irritation |

| 9-21 | Severe irritation |

Stability studies

The optimized formulation was subjected to short-term stability studies as per ICH recommended conditions (25 °C/60% RH and 40 °C/75%) for 3 mo by preserving the formulation in sterile vials. The formulation was assessed for essential parameters such as particle size, PDI, entrapment efficiency, and drug content at 0, 1, 2, and 3 mo [28].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

FTIR spectral study

The IR spectra of Neomycin sulfate exhibited the absorption bands at 3250, 3450, and 1001 cm-1, which correlate with O-H (alcohol) stretching, NH2 (amine) stretching, and C-O-C (ether) stretching functional groups (fig. 3A). On the other hand, the IR spectra of pure GMS displayed distinctive peaks at 3003, 1046, 3303, and 1729 cm-1, signifying the existence of O-H (alcohol) stretching, C-O-C (ether) stretching and C=O (ketone) functional groups (fig. 3b). The IR spectrum of physical mixture of Neomycin sulfate with GMS showed significant peaks at 3200, 3410, 1046 and 1729 cm-1 which correspond to O-H (alcohol) stretching, NH2 (amine) stretching, C-O-C (ether) stretching, and C=O (ketone) functional groups (fig. 3c). The FTIR analysis revealed that the main peaks for the drug, lipid, and their physical blend were the same, with no extra peaks detected, indicating no chemical interaction between the drug and lipids.

Fig. 1: (A) FTIR of pure neomycin sulfate, (B) FTIR of pure GMS, (C) FTIR of physical mixture of Neomycin sulfate and GMS

Optimization of neomycin sulfate SLNs

Using a 32 full factorial statistical design, 10 SLN formulations were developed with varying lipid concentration and sonication time. The SLNs were fabricated through solvent evaporation and ultra sonication methods. Particle size and entrapment efficiency were measured to find the optimal formulation. Particle sizes ranged from 168.3 to 355.1 nm, and the entrapment efficiency was in the range of 78.6 to 90.4%.

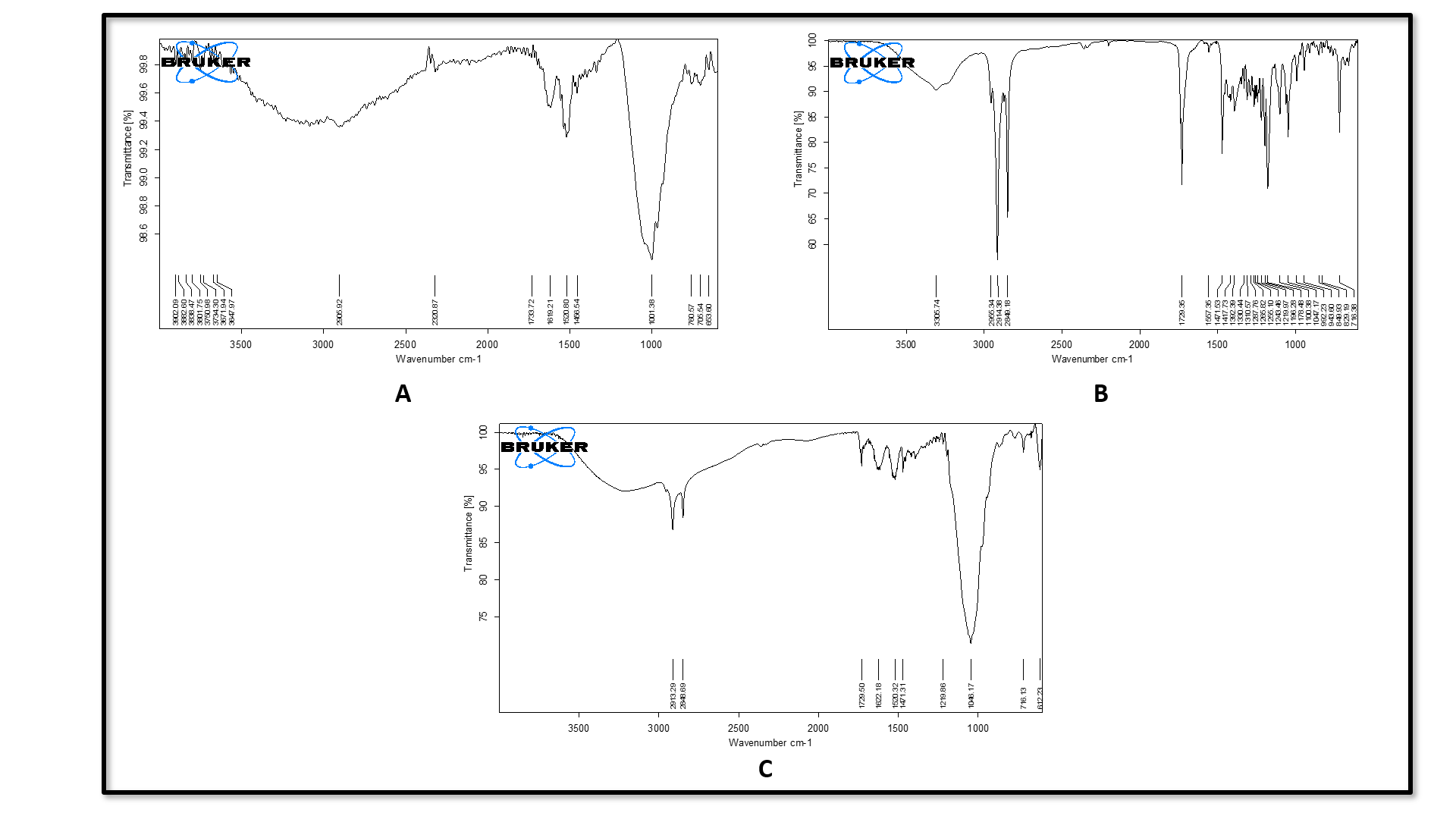

Influence of particle size (R1) on independent factors

The model for factor particle size has an F-value of 22.18 and a P-value of 0.0051 in the ANOVA analysis. Good model predictability was confirmed, with the Predicted R2 (0.8599) closely matching the adjusted R2 (0.9217), the difference being within the acceptable threshold of 0.2. The resulting linear equation from the regression analysis is expressed as follows.

Particle size =+301.08+24.20 A-61.85 B-26.87 AB+2.79 A²-64.86 B² (coded terms) Where, A-Lipid concentration (mg) and B-sonication time (min).

Analysis of the contour (fig. 2A) and 3D surface plots (fig. 2B) indicates that sonication time (B) is the dominant factor affecting particle size. Increasing sonication time initially leads to larger particles, likely due to aggregation, but extended sonication significantly reduces particle size as evidenced by the strong negative linear (-61.85B) and quadratic (-64.86B²) terms, suggesting a non-linear effect where prolonged sonication enhances particle size reduction. In contrast, lipid concentration (A) has a relatively minor impact with a modest positive linear effect (+24.20A) and a small quadratic contribution (+2.79A²), indicating a slight increase in particle size with higher lipid concentrations, possibly due to increased droplet coalescence. Overall, sonication time is the most significant variable for particle size reduction, while lipid concentration has a less significant effect.

Fig. 2: Contour (A) and 3D surface plot (B) of particle size against independent factors

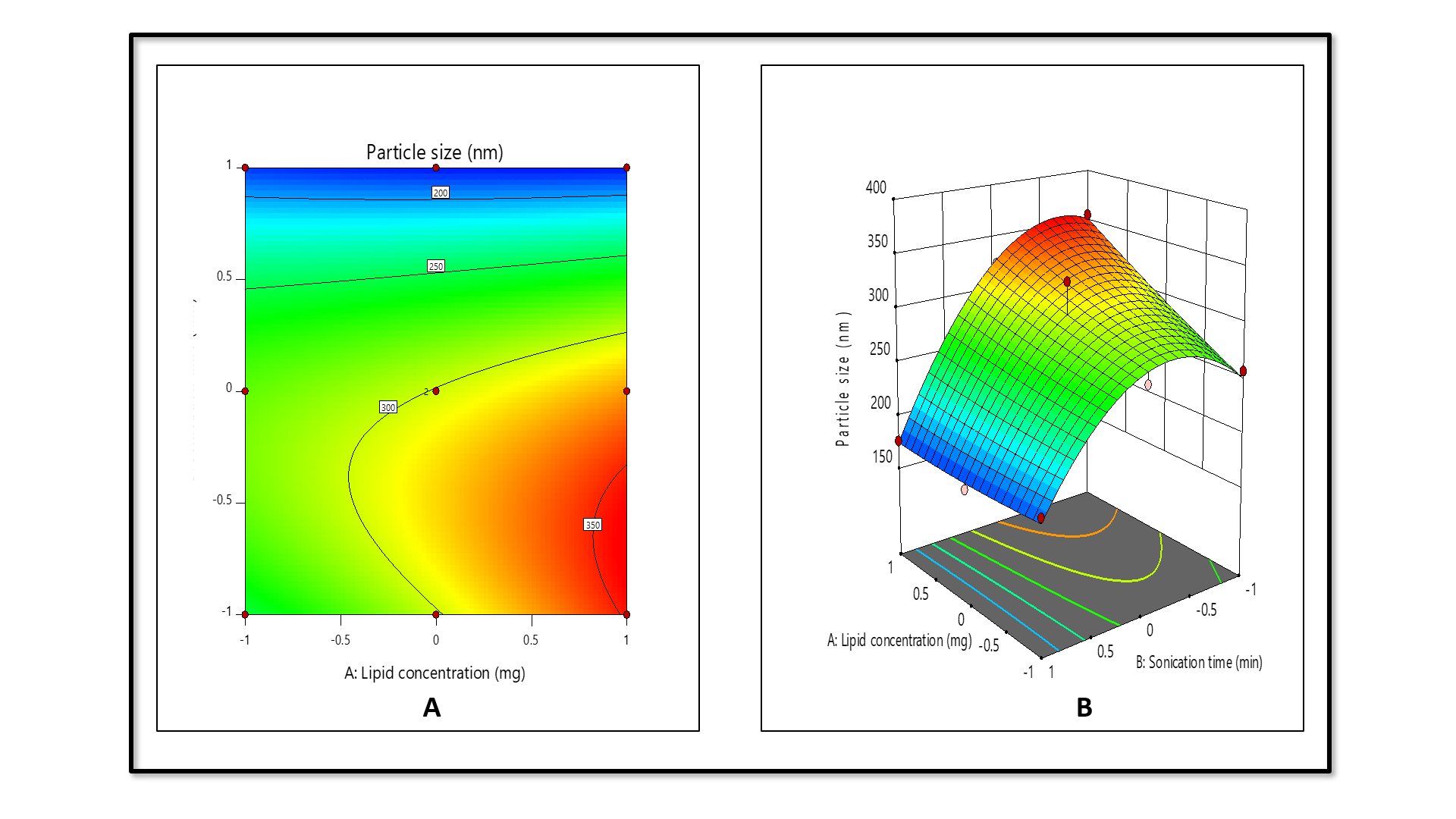

Influence of entrapment efficiency (R2) on independent factors

The quadratic model for entrapment efficiency (%) demonstrated F-value = 6.61, P-value = 0.0249, confirming the predicted R2 (0.5318) in compliance with adjusted R2 (0.6515), since the difference was less than 0.2.

The derived regression equation for Neomycin sulfate SLNs entrapment efficiency was written as follows:

% Entrapment efficiency =+85.79+2.10A+1.35 B-3.45 AB+9.31 A²-8.50 B2 (coded factors)

Where A-Lipid concentration (mg) and B-sonication time (min)

The contour (fig. 3C) and 3D surface plots (fig. 3D) reveal that lipid concentration (A) is the primary factor, significantly enhancing % entrapment efficiency, as indicated by the positive linear (+2.10A) and strong quadratic (+9.31A²) terms, likely due to increased availability of lipid material for encapsulating the active compound. Conversely, sonication time (B) has a lesser impact, with a modest positive linear effect (+1.35B) overshadowed by a substantial negative quadratic term (-8.50B²), suggesting that prolonged sonication reduces entrapment efficiency, possibly by disrupting the lipid matrix. The interaction term (-3.45AB) indicates a notable interaction effect, where the combined influence of higher lipid concentration and extended sonication time moderately reduces entrapment efficiency, potentially due to over-processing that destabilizes the lipid structure. It was found that entrapment efficiency was greatly influenced by lipid concentration, and sonication time had a negative effect on entrapment efficiency.

Percentage error between predicted and observed results

The optimized SLN formulation displayed a mean particle size of 178.2±3.22 nm with an entrapment efficiency of 85.6±2.17. The experimental results for both factors were deviated by less than±5% from the predicted values, confirming high reproducibility. Statistical analysis confirmed significance at a 95% confidence level. Table 4 represents the selected solution along with the percentage error between predicted and observed values.

Table 4: Selected solution and the % error between the predicted and observed values

| Factors | Responses | ||

| A: Lipid concentration (mg) | B: Sonication time(min) | Particle size(nm) | Entrapment efficiency (%) |

| Predicted | |||

| 30 | 25 | 174.371 | 87.140 |

| Observed | |||

| 178.2±3.22 | 85.6±2.17 | ||

| %Error | 3.629 | 1.54 |

Results are given in mean ±SD, n=3

Fig. 3: Contour (C) and 3D surface plot (D) of entrapment efficiency (%) against independent factors

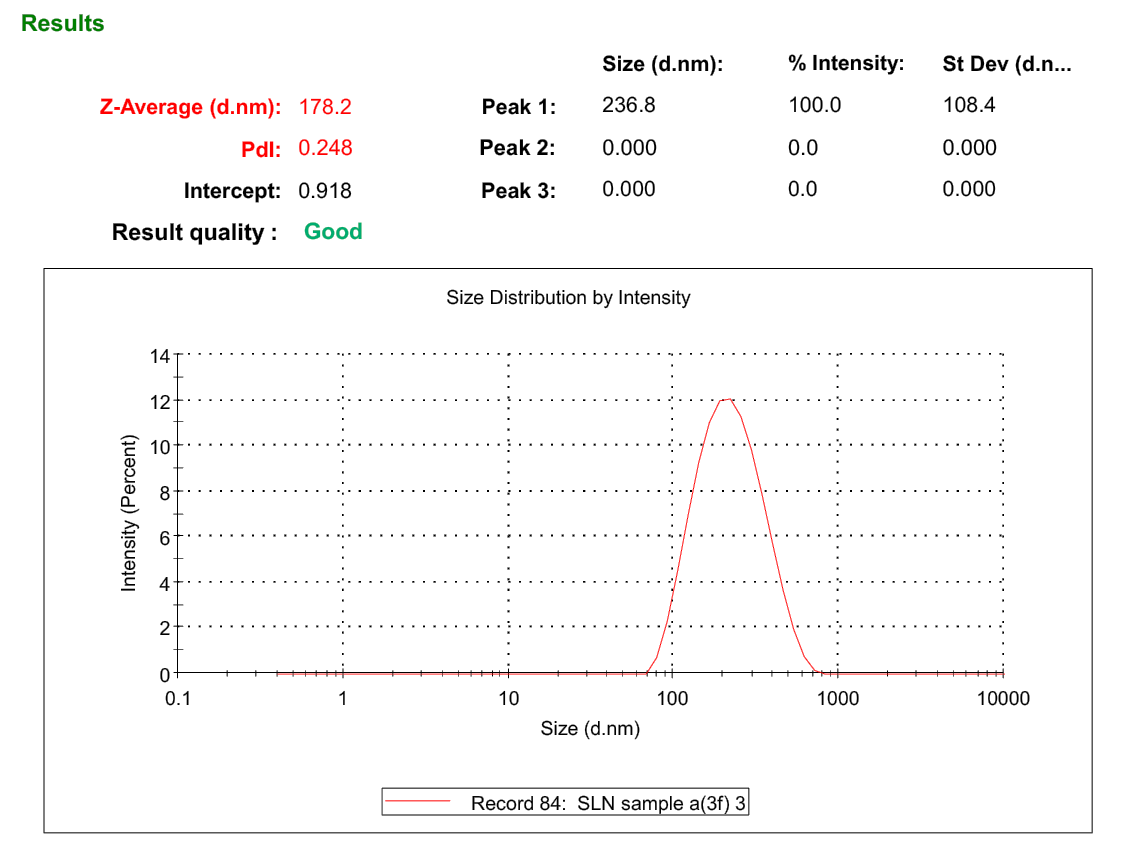

Particle size and PDI of optimized formulation

The optimized formulation exhibited a mean particle size of 178.2 ±3.22 with a PDI of 0.246 (fig. 4), which reveals that optimized SLNs were within the nano-formulation size scale, commonly ranging between 1 and 1000 nm. SLNs within this size range are known to offer several advantages, including enhanced solubility, bioavailability, and increased cellular uptake, making them highly suitable for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. The PDI is a critical parameter that reflects the uniformity of particle size distribution within the sample. PDI values less than 0.3 are generally considered acceptable for SLNs, suggesting a narrow size distribution and stable system. In a previous study, chitosan-based nanoparticles of Nemoycin sulfate formulations predicted lesser entrapment with more than 200 nm particle sizes [20]. In the current study, the results of the particle size of the formulation predicted a size of less than 200 nm, which is ideal for the enhanced permeation of the drug through the corneal surface of the eye. Furthermore, the uniform distribution of particles observed in the formulation indicates successful drug entrapment during the formulation process. This uniformity is essential for consistent performance, especially in the drug delivery systems, where particle size can significantly influence the release profile and therapeutic efficacy.

Fig. 4: Particle size and PDI of optimized Neomycin sulfate SLNs

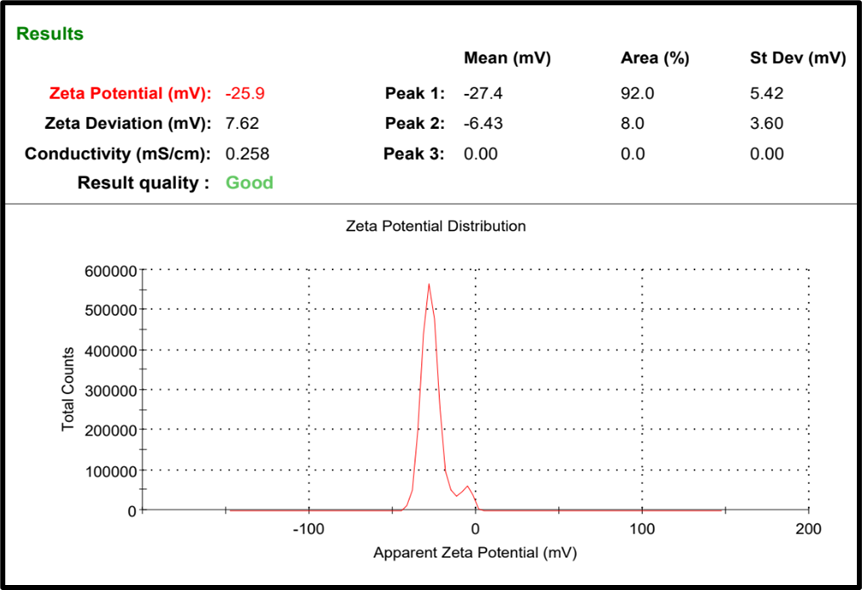

Zeta potential

Zeta potential is a key indicator of the surface charge of nanoparticles and plays a critical role in predicting the physical stability of colloidal systems. The optimized formulation exhibited a zeta potential of-25.9 mV (fig. 5). In general, zeta potential values greater than ±25 mV are considered to confer moderate to good stability due to the electrostatic repulsion between particles, which prevents aggregation. In this case, the obtained zeta potential result suggests that SLNs possess sufficient surface charge to maintain colloidal stability. The negative surface charge can influence the residence time of SLNs in the ocular region. On the other hand, the formation of stable negative surface charge can be attributed to the specific lipid composition of SLNs and the potential release of fatty acids over time through hydrolysis. These released fatty acids can further contribute to the negative zeta potential, potentially improving long-term colloidal stability of the system. In the ocular environment, the corneal and conjunctival epithelial surfaces are negatively charged due to the presence of sialic acid residues in mucin and anionic components of the tear film. This leads to electrostatic repulsion between negatively charged SLNs and the ocular surface, which can reduce mucoadhesion and residence time. Further, studies suggest that a moderately negative zeta potential (in the range of -15 to -30 mV) provides a balance between colloidal stability and acceptable mucoadhesion [15].

Fig. 5: Zeta potential of optimized Neomycin sulfate SLNs

pH and drug content (%)

The pH is a crucial factor for ocular administration, as any deviation from the normal eye pH could cause irritation. The pH of the optimized formulation was found to be 7.2±1.46, which falls within the ophthalmic range of 7-7.4. Additionally, the drug content analysis showed that the drug was uniformly distributed throughout the formulation, with a maximum of 93.05% drug content.

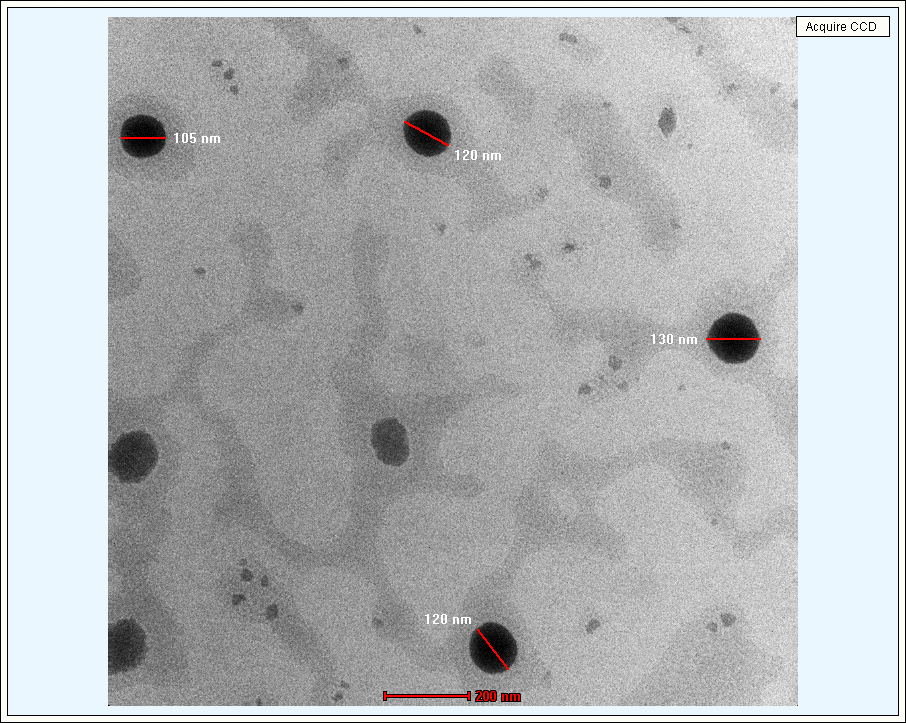

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to assess the morphology of the optimized formulation. The TEM images (fig. 6) showed well-defined spherical structures coated with polymer, and their sizes aligned with the particle size data obtained from dynamic light scattering analysis. Notably, the presence of a visible polymer coating surrounding the lipid core in the TEM image suggests successful encapsulation and surface modification of the SLNs. This lipid vesicular system can enhance mucoadhesion by interacting with mucins on the ocular surface, thereby increasing the retention time of the formulation. It is particularly valuable in overcoming the challenges posed by rapid clearance mechanisms of the eye, such as tear turnover and blinking. Additionally, the absence of aggregation or morphological deformities suggests that the formulation is physically stable and unlikely to induce ocular irritation upon administration.

Fig. 6: TEM Images of optimized Neomycin sulfate SLNs

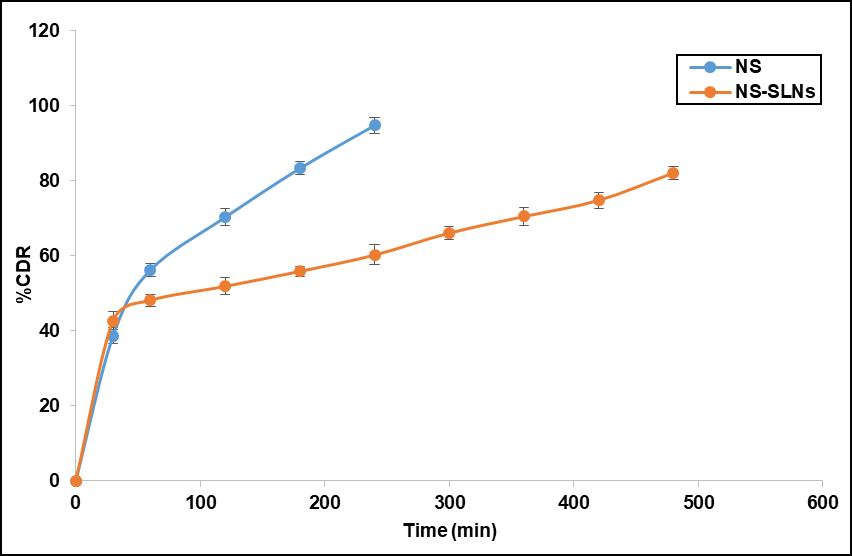

In vitro drug release study

The drug release study was conducted for both free Neomycin sulfate and the optimized formulation (fig. 7). Pure Neomycin sulfate (NS) shows a rapid drug release, up to 94 % within 90 min. This fast release is likely due to the fact that NS is in its free form, not encapsulated or bound to any matrix. The optimized formulation (NS-SLNs) exhibited maximum drug release of 82.11±0.34% throughout 8 h. The release study exhibited a biphasic release pattern, characterized by an initial burst release within the first 50 min, followed by a prolonged and controlled release. The burst release observed at the beginning of the study can be attributed to the rapid diffusion of the drug, Neomycin sulfate, which is loosely associated with the surface or outer layers of SLNs. Research studies claim that for nanoparticulate drug delivery systems, the drug on the outer surface of the particles is more readily available for release. During the early stage of release, the drug molecules can quickly migrate out of the nanoparticle matrix and diffuse through the membrane of the release medium. Following the burst release, the drug release slowed down significantly, entering a sustained release phase. This prolonged release can be attributed to the interaction between the lipid core and the polymeric shell that encapsulates the drug. Moreover, the polymeric coating surrounding the lipid core likely contributes to the prolonged release. The swelling and erosion of the polymeric matrix play a key role in controlling the rate of drug release [29].

Fig. 7: Drug release profile of optimized formulation. Error bars indicate SD values

Drug release kinetics

The release kinetics of neomycin sulfate from SLNs were evaluated using various mathematical models. The main focus of the data analysis was to determine the statistical significance of the coefficients. Notably, the Higuchi model exhibited good linearity, with an R² value of 0.9741 (fig. 8). The Higuchi model assumes a relatively uniform drug distribution within the matrix. In SLNs, even though some drug resides on the surface, the majority is distributed within the lipid core, creating a pseudo-homogeneous system that supports Higuchi kinetics. The majority of Neomycin sulfate is encapsulated within the lipid core. The drug entrapped in the core must diffuse through the lipid matrix to reach the SLN surface and release into the medium. This process is slower due to the hydrophobic nature of the lipid core. The sustained release system, which dominates the drug release profile, aligns closely with Higuchi kinetics because it is controlled by the gradual diffusion of the drug through the matrix, modulated by the physical state and swelling of the lipid.

Fig. 8: Higuchi release kinetics model of Neomycin sulfate-loaded SLNs

Ex-vivo drug permeation study

The ex vivo drug permeation study for the optimized formulation was conducted using a goat's eye corneal membrane as a diffusion barrier, providing a more realistic environment, and was performed over 12 h. The results demonstrated sustained drug release from the optimized formulation, with over 60% (fig. 9) of the drug released during this time. This release was slower compared to the in vitro studies, likely due to the properties of the corneal membrane. The cornea, consisting of multiple layers (epithelium, stroma, and endothelium), has a more complex structure than the simpler membranes used in in vitro tests. These additional layers create a greater challenge for drug diffusion, resulting in a slower release rate. The sustained release profile of SLNs, driven by the diffusion-controlled mechanism and further slowed down by the corneal barrier, ensuring more consistent drug concentration in the ocular tissues such as the cornea and conjunctiva. Unlike traditional eye drops, which exhibit rapid clearance from the ocular surface due to tear turnover and nasolacrimal drainage, SLNs can adhere to the ocular surface or penetrate superficial layers, acting as a depot for prolonged release.

Fig. 9: Comparative study of Ex-vivo drug permeation with in vitro drug release of optimized formulation. Error bars indicate SD values

Sterility test

Sterility evaluation is crucial for ophthalmic products, and the results confirmed that the optimized formulation was sterile. No microbial growth, including bacteria or fungi, was observed after a 7 d incubation period, when compared to the positive and negative controls (fig. 10 A and B). This indicates that the formulation meets the sterility test standards. The sterility test results for the optimized Neomycin sulfate SLN formulation are presented in table 6.

Table 6: The results of the sterility test for the optimized formulation

| Medium used | Test microorganism | Positive control | Negative control | Optimized formulation |

| Fluid thioglycolate medium | S. aureus | + | - | - |

| E. coli | + | - | - | |

Soybean-casein digest medium |

C. albicans | + | - | - |

| A. brasiliensis | + | - | - |

Where+indicates microbial growth, -indicates no microbial growth

Fig. 10: Sterility test for bacteria (A) and fungi (B)

Isotonicity test

The isotonicity test, an essential part of ophthalmic formulation development, was performed using red blood cells (RBCs). The optimized formulation was compared to a marketed eye drop to assess its effect on RBC morphology (fig. 11 A and B). The results showed that the optimized formulation exhibited no changes in RBC shape, similar to the marketed product. There was no swelling or shrinkage of the RBCs, confirming that the optimized formulation was isotonic with blood.

In vitro ocular irritation study by HET-CAM test

The HET-CAM assay was conducted to determine the ocular safety of the optimized formulation. Upon application to the CAM of chick embryo, the irritation potential was assessed and compared with both negative control (0.9% NaCl) and positive control (1% SDS), as shown in fig. 12. The positive control triggered a strong irritant response, with a mean score of 14.58±1.28, evident by vascular damage and haemorrhage. In contrast, the optimized formulation produced a very low irritation score of 0.09±1.33, falling well within the non-irritant range (table 7). Combined with the absence of visual signs of irritation, these findings indicated that the formulation was likely safe and non-toxic for ocular delivery.

Ex-vivo corneal histopathology study

Examination of corneal tissue via ex vivo histopathology showed no structural variations between the control, standard, and optimized formulations. This suggests that the optimized formulation is biocompatible, as it preserved the normal structure of corneal cells, similar to the tissue treated with both normal saline and the marketed formulation (fig. 13).

Fig. 11: Isotonicity test for marketed product (A) and for optimized formulation (B)

Table 7: Results of HET-CAM test for optimized formulation

| Test compound | Mean irritation score* | Inference |

| 0.9 % NaCl (Negative control) | 0.07±0.68 | No irritation |

| 1% SDS (Positive control) | 14.58±1.28 | Severe irritation |

| Optimized formulation | 0.09±1.33 | No irritation |

*Results are given in mean ±SD, n=3

Fig. 12: HET-CAM test images

Fig. 13: Ex-vivo histopathology test images

Stability studies

The stability study data of optimized formulation (table 8) demonstrated no wide differences in the results of particle size, PDI, % EE, and drug content when stored at room temperature of 25 °C, whereas slight variations were observed in % EE and drug content when stored at 40 °C at 3rd month. Since the obtained results were not more than a 5% variation, the formulation was found to be stable at both temperatures. Additionally, there were no signs of any colour change, sedimentation, and aggregation, that revealed that optimized SLNs retained good stability with no drug degradation.

Table 8: Stability study results of optimized formulation

| Temperature | Month | Particle size | PDI | % EE | % Drug content |

| 25 °C | 0 | 176.3±2.12 | 0.215±1.33 | 84.3±1.77 | 92.64±2.43 |

| 1 | 173.1±2.64 | 0.238±2.56 | 81.2±2.26 | 90.23±2.14 | |

| 2 | 172.5±2.33 | 0.264±2.25 | 82.6±1.66 | 90.18±1.46 | |

| 3 | 174.2±2.06 | 0.303±1.84 | 80.4±1.54 | 91.33±1.94 | |

| 40 °C | 0 | 176.4±1.17 | 0.312±1.63 | 81.4±2.33 | 89.67±0.74 |

| 1 | 181.2±1.06 | 0.286±0.78 | 78.8±1.68 | 87.38±1.59 | |

| 2 | 180.6±2.17 | 0.314±2.15 | 76.4±2.31 | 86.52±2.07 | |

| 3 | 183.4±2.11 | 0.318±1.53 | 75.7±1.84 | 84.66±2.13 |

Results are given in mean ±SD, n=3

CONCLUSION

In the present study, an attempt was made to formulate and evaluate the Neomycin sulfate-SLNs for ocular administration. The SLNs were formulated using the solvent evaporation technique, followed by probe sonication, utilizing GMS as the lipid base. A 32 full factorial design was applied to optimize the SLNs through the Design Expert® software. The resulting optimized SLNs displayed particle size (nm) and entrapment efficiency (%) values that were within ±5% of the anticipated outcomes. TEM analysis confirmed the spherical shape of the particles. The optimized formulation exhibited a sustained drug release profile over 8 h, adhering to Higuchi release kinetics. Tests for sterility and isotonicity verified that the formulation was both sterile and compatible with blood. The HET-CAM assay indicated no ocular irritation, and the ex vivo histopathology study evidenced no damage to corneal tissue, reinforcing the ocular safety of the formulation. Short-term stability studies of 3 mo revealed that the formulation was stable with no wide differences in the evaluated parameters. In conclusion, Neomycin sulfate-loaded SLNs offer a promising alternative to traditional eye drops, potentially addressing their limitations in treating bacterial conjunctivitis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank the NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (Deemed to be University), Mangaluru, for providing necessary support.

FUNDING

Nil

ABBREVIATIONS

SLNs: Solid lipid nanoparticles; GMS: Glyceryl monostearate; ANOVA: Analysis of variance; DoE: Design of experiments; PDI: Polydispersibility index; FTIR: Fourier transform infrared; STF: Simulated tear fluid; TEM: Transmission electron microscope; % EE: Percentage entrapment efficiency; rpm: Revolutions per minute; % CDR: Percentage cumulative drug release; hrs: hours; HET-CAM: Hen’s Egg test-Chorioallantoic membrane; FTG: Fluid thioglycolate medium; SCDM: Soyabean casein digest medium; SDS: Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate; °C: Degree Celsius; IS: Irritation score.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Both authors contributed significantly to this work; Veeksha S Shetty designed the work, prepared the manuscript, and took part in the execution of the data. Sandeep DS drafted, revised the manuscript, reviewed the final version, and approved the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there were no competing interests found.

REFERENCES

Seyfoddin A, Shaw J, Al-Kassas R. Solid lipid nanoparticles for ocular drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 2010;17(7):467-89. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2010.483257, PMID 20491540.

Snyder RW, Glasser DB. Antibiotic therapy for ocular infection. West J Med. 1994;161(6):579-84. PMID 7856158.

Khames A, Khaleel MA, El-Badawy MF, El-Nezhawy AO. Natamycin solid lipid nanoparticles-sustained ocular delivery system of higher corneal penetration against deep fungal keratitis: preparation and optimization. IJN. 2019;14:2515-31. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S190502.

Duong VA, Nguyen TT, Maeng HJ. Preparation of solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers for drug delivery and the effects of preparation parameters of solvent injection method. Molecules. 2020;25(20):4781. doi: 10.3390/molecules25204781, PMID 33081021.

Ghasemiyeh P, Mohammadi Samani S. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers as novel drug delivery systems: applications, advantages and disadvantages. Res Pharm Sci. 2018;13(4):288-303. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.235156, PMID 30065762.

Hosny KM, Naveen NR, Kurakula M, Sindi AM, Sabei FY, Fatease AA. Design and development of neomycin sulfate gel loaded with solid lipid nanoparticles for buccal mucosal wound healing. Gels. 2022;8(6):385. doi: 10.3390/gels8060385, PMID 35735729.

Mulani H, Bhise KS. QbD approach in the formulation and evaluation of miconazole nitrate-loaded ethosomal cream-o-gel. Int Res J Pharm Sci. 2017;8(1):1-37.

Hosny KM, Naveen NR, Kurakula M, Sindi AM, Sabei FY, Fatease AA. Design and development of neomycin sulfate gel loaded with solid lipid nanoparticles for buccal mucosal wound healing. Gels. 2022;8(6):385. doi: 10.3390/gels8060385, PMID 35735729.

Patil J, Rajput R, Nemade R, Naik J. Preparation and characterization of artemether-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles: a 32 factorial design approach. Materials Technology. 2020;35(11-12):719-26. doi: 10.1080/10667857.2018.1475142.

Weissman SA, Anderson NG. Design of experiments (DoE) and process optimization. A review of recent publications. Org Process Res Dev. 2015;19(11):1605-33. doi: 10.1021/op500169m.

Kraisit P, Hirun N, Mahadlek J, Limmatvapirat S. Fluconazole-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) as a potential carrier for buccal drug delivery of oral candidiasis treatment using the Box-Behnken design. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021;63:1024-37. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102437.

Kelidari HR, Saeedi M, Akbari J, Morteza Semnani K, Gill P, Valizadeh H. Formulation optimization and in vitro skin penetration of spironolactone-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2015;128:473-9. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.02.046, PMID 25797482.

Öztürk AA, Yenilmez E, Şenel B, Kıyan HT, Güven UM. Effect of different molecular weight PLGA on flurbiprofen nanoparticles: formulation, characterization, cytotoxicity, and in vivo anti-inflammatory effect by using HET-CAM assay. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020;46(4):682-95. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2020.1755304, PMID 32281428.

Mahmoud RA, Hussein AK, Nasef GA, Mansour HF. Oxiconazole nitrate solid lipid nanoparticles: formulation, in vitro characterization and clinical assessment of an analogous loaded carbopol gel. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020;46(5):706-16. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2020.1752707, PMID 32266837.

de Campos AM, Diebold Y, Carvalho EL, Sánchez A, Alonso MJ. Chitosan nanoparticles as new ocular drug delivery systems: in vitro stability, in vivo fate, and cellular toxicity. Pharm Res. 2004;21(5):803-10. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000026432.75781.cb, PMID 15180338.

Shirisha S, Saraswathi A, Sahoo SK, Rao YM. Formulation and evaluation of nisoldipine-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers: application to transdermal delivery. Ind J Pharm Educ Res. 2020;54(2s):s117-27. doi: 10.5530/ijper.54.2s.68.

Iriventi P, Gupta NV, Osmani RA, Balamuralidhara V. Design & development of nanosponge loaded topical gel of curcumin and caffeine mixture for augmented treatment of psoriasis. Daru. 2020;28(2):489-506. doi: 10.1007/s40199-020-00352-x, PMID 32472531.

Patel AH, Dave RM. Formulation and Evaluation of Sustained Release in situ ophthalmic Gel of neomycin sulphate. Bol Pharm Res. 2015;5(1):1-5.

Gokhale JP, Mahajan HS, Surana SJ. Quercetin-loaded nanoemulsion-based gel for rheumatoid arthritis: in vivo and in vitro studies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;112:108622. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108622, PMID 30797146.

Supriya A, Sundaraseelan J, Srinivas Murthy BR, Bindu Priya M. Formulation and in vitro characterization of neomycin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. Acta Sci Pharm Sci. 2018;2(2):34-40.

Dash S, Murthy PN, Nath L, Chowdhury P. Kinetic modeling on drug release from controlled drug delivery systems. Acta Pol Pharm. 2010;67(3):217-23. PMID 20524422.

Lokhandwala H, Deshpande A, Deshpande SH. Kinetic modeling and dissolution profiles comparison: an overview. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2013;4(1):728-33.

Sah AK, Suresh PK, Verma VK. PLGA nanoparticles for ocular delivery of loteprednol etabonate: a corneal penetration study. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2017;45(6):1-9. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2016.1203794, PMID 27389068.

Indian pharmacopoeia. 6th ed. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Controller of Publications. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2007. p. 56-60.

Ganesh NS, Ashir TP, Vineeth C. Review on approaches and evaluation of in situ ocular drug delivery system. Int Res J Pharm Biosci. 2017;4(3):23-33.

Wilson SL, Ahearne M, Hopkinson A. An overview of current techniques for ocular toxicity testing. Toxicology. 2015;327:32-46. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.11.003, PMID 25445805.

Khan N, Aqil M, Imam SS, Ali A. Development and evaluation of a novel in situ gel of sparfloxacin for sustained ocular drug delivery: in vitro and ex vivo characterization. Pharm Dev Technol. 2015;20(6):662-9. doi: 10.3109/10837450.2014.910807, PMID 24754411.

Sun K, Hu K. Preparation and characterization of tacrolimus-loaded SLNs in situ gel for ocular drug delivery for the treatment of immune conjunctivitis. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2021;15:141-50. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S287721, PMID 33469266.

Bachu RD, Chowdhury P, Al-Saedi ZH, Karla PK, Boddu SH. Ocular drug delivery barriers-Role of nanocarriers in the treatment of anterior segment ocular diseases. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(1):28. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10010028, PMID 29495528.