Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 30-41Review Article

THE ROLE OF ΑIIBΒ3 RECEPTORS IN MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION: MECHANISMS AND THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES

ABU SAFANA BISWASa, GANAVI BETHANAGERE RAMESHAa, KAMSAGARA LINGANNA KRISHNAa*, BHARAT JAYAPRAKASH BYALAHUNASHIa, SEEMA MEHDIa, SUMAN PATHAKb

aDepartment of Pharmacology, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore-570015, Karnataka, India. bDepartment of Dravyaguna, Govt. Ayurvedic Medical College, Shimoga-577201, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Kamsagara Linganna Krishna; *Email: klkrishna@jssuni.edu.in

Received: 07 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 01 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Myocardial infarction (MI), a leading cause of death globally, is primarily caused by coronary artery blockage and the resulting myocardial ischemia. The epidemiology, molecular processes, clinical biomarkers, and treatment approaches of MI are all included in this review. In addition, the traditional antiplatelet treatments and new natural inhibitors such as disintegrin from snake venom, special attention is given to the platelet integrin αIIbβ3 receptor, whose crucial function in MI pathogenesis is reviewed. Several studies conducted between 2018 and 2023 demonstrated that αIIbβ3 plays a crucial role in mediating fibrinogen-dependent platelet aggregation and thrombus stability after plaque rupture. Using αIIbβ3 inhibitors during high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was justified by these findings. The recent studies done in 2024–2025 have broadened our understanding by showing that αIIbβ3 has a role in leukocyte-platelet interactions, thrombosis, inflammatory signalling, and plaque progression, indicating that its functions extend beyond hemostasis. Vascular damage and repair are reviewed in connection with important molecular pathways implicated in MI development, such as PI3K/Akt, Notch, NLRP3/Caspase-1/IL-1β, TLR4/MYD88/NF-κB, JAK/STAT, and TGF-β/SMADs. The growing clinical significance of diagnostic biomarkers such as troponins, CK-MB, VEGF-A₁₆₅b, and MMP-28 is underlined. In summary, αIIbβ3 continues to play a key role in thrombus formation by binding fibrinogen and encouraging platelet aggregation; however, recent data suggest that it also plays a role in vascular inflammation and atherogenesis, making it a viable target for the treatment of MI both acutely and over the long term.

Keywords: Fibronectin, Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, αIIbβ3 receptors, Platelet activation, Fibrinogen, Myocardial infarction

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54646 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

A collection of conditions that impact the heart and blood vessels is collectively referred to as cardiovascular disease (CVD). Heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, stroke, and rheumatic heart disease are the main categories [1]. The term "myocardial infarction" (MI) describes the permanent death of heart muscle tissue brought on by extended myocardial ischemia as a result of decreased or obstructed coronary blood flow [2]. Acute or chronic myocardial ischemia brought on by an imbalance between the supply and demand of oxygen causes MI, the most severe type of coronary heart disease (CHD). Following MI, myocardial injury or necrosis is characterized by increased cardiac biomarkers, supported by clinical evidence that aligns with electrocardiogram changes, imaging confirmation of new damage to viable myocardium, or a sudden abnormality in regional wall motion. One of the clinical indicators of MI is severe and persistent chest pain, which frequently coexists with nausea, sweating, and dyspnea. Angina, ischemic episodes, severe to fatal arrhythmias, and congestive heart failure (CHF) are among the complications of MI [3]. The main cause of MI, also known as a heart attack, is a decrease in or cessation of the blood supply to a portion of the heart, which results in the heart muscle becoming necrotic [4]. Cardiovascular diseases are one of the most prevalent causes of death in the world, with acute cardiovascular events responsible for over 20 million deaths annually [5]. Cases of MI are increasingly reaching levels comparable to those in industrialized nations, emphasizing the need for stronger preventive measures [6]. In India, MI is affecting a growing number of young individuals [7]. MI, a major cause of death worldwide, is particularly prevalent in South Asian countries like India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. In these nations, younger individuals under 45 have a higher MI prevalence than older adults, unlike in developed countries. India has a CVD mortality rate of 272/100,000, exceeding the global average, with MI responsible for 31.7% of deaths, driven by genetic and lifestyle factors [8-13]. Polymorphisms in the ITGB3 gene, which encodes the αIIbβ3 integrin receptor, have been detected among South Asian populations, including Bangladeshi patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. These polymorphisms may lead to higher platelet reactivity and thrombotic risk. Natural compounds isolated from Lespedeza cuneata have shown antiplatelet and antithrombotic properties by inhibiting αIIbβ3, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt signalling pathways [14, 15]. αIIbβ3 receptor inhibitors reduce arterial blockage and improve blood flow to stop further complications by preventing platelet aggregation and thrombus formation in MI. Antagonists of the αIIbβ3 integrin receptor reduce thrombus formation by blocking fibrinogen binding, thereby inhibiting platelet aggregation [16]. The main objective of this review is to investigate the function of αIIbβ3 receptors in MI, with an emphasis on how they contribute to thrombus formation and platelet aggregation. Its objectives are to analyze new and existing αIIbβ3 inhibitors, determine how well they work as treatments, and investigate ways to improve antiplatelet therapy for better MI prevention and management. In this review, a comprehensive literature search was conducted using various search engines such as public databases, including PubMed, the National Library of Medicine, and Google Scholar. The selection criteria encompassed original research articles, meta-analyses, and review articles published between 2018 and 2025. The primary focus was on studies related to the αIIbβ3 receptor, platelet activation and inactivation, myocardial infarction, and coronary heart disease. Additionally, research on αIIbβ3 receptor inhibitors was included to explore their therapeutic significance. The search strategy involved the use of specific keywords to ensure the inclusion of relevant and high-quality studies. This approach provided a comprehensive understanding of the role of αIIbβ3 receptors in cardiovascular diseases.

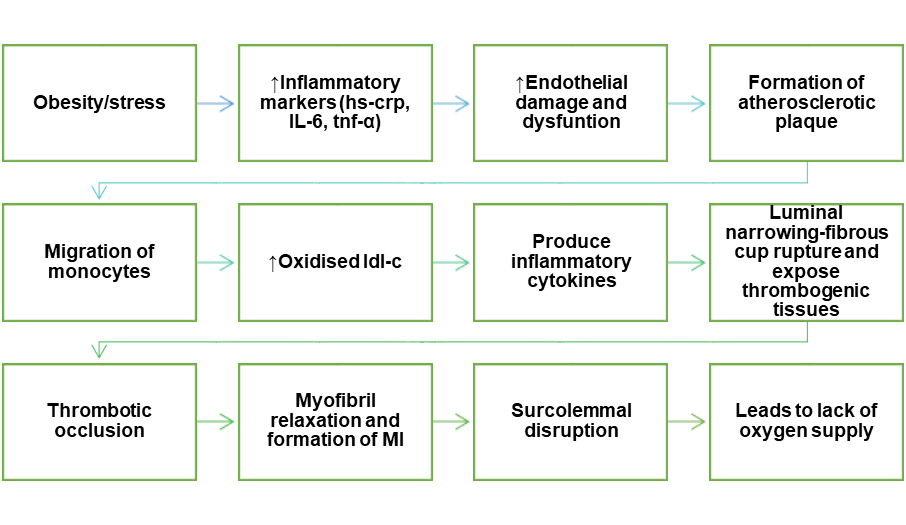

Etiology and pathophysiology

Urban Indians have a higher body mass index (BMI) than rural people, and abdominal obesity is a greater predictor of ischemic heart disease (IHD) risk than overall obesity [17]. Visceral fat causes persistent low-grade inflammation, leading to elevated systemic markers, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), which is a consistent predictor of coronary heart disease (CHD) risk [18]. These inflammatory signals contribute to endothelial dysfunction, which is a characteristic of early atherosclerosis [19].

Endothelial damage exposes subendothelial collagen and von Willebrand factor, which promote platelet attachment. Platelets activate in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines released during metabolic stress (e. g., TNF-α, IL-6), altering the conformation of αIIbβ3 integrin receptors. This alteration allows fibrinogen to bridge across platelets, facilitating aggregation and thrombus formation, which is critical to the etiology of myocardial infarction (MI).

Inflammation-driven activation of αIIbβ3 is a crucial step in thrombotic occlusion of coronary arteries, regardless of the initial trigger (e. g. plaque rupture, erosion, or stress-induced endothelial damage). The resulting ischemia causes myocyte injury, which includes sarcolemmal rupture, calcium overload, myofibril relaxation, and eventually necrosis [21-23] (fig. 1).

Furthermore, psychological stressors-such as social isolation or depression-can activate the sympathoadrenal system, raising circulating catecholamines that further aggravate endothelial dysfunction and promote platelet hyperreactivity [18].

Fig. 1: Schematic representation of the pathophysiology of myocardial infarction: This fig. demonstrates the formation of MI through endothelial damage and its dysfunction by the formation of plaque and the production of inflammatory cytokines

Biomarkers for myocardial infarction

Normal blood myoglobin levels range from 6 to 85 ng/ml; they begin to rise two hours after AMI begins, peak between 6 and 9 h later, and then drop to baseline within a day [24]. Three isoenzymes make up the dimeric enzyme creatine kinase (CK): CK-BB (CK1), CK-MB (CK2), and CK-MM (CK3). M and B are the two subunits that make up CK [25]. There are two groups in CK-MB: MB1 and MB2. MB2 enters the blood, accompanied by a notable shift in the MB2 ratio when AMI occurs. An MB2 ratio of ≥1.5 is thought to indicate AMI. CK-MB has a 97% negative predictive value within the first six hours of AMI diagnosis, making it a very effective biomarker for this diagnosis [26]. Changes in cTn, in conjunction with clinical signs and ECG, may be used to detect AMI early on, following the development of chest discomfort, thereby reducing mortality. There is also a separate risk factor for unfavorable clinical results following MI [27]. VEGF-A165b, the primary anti-angiogenic isoform of VEGF-A, is linked to the size of the infarct in patients with AMI. In aging endothelial cells, dysregulated VEGF-A165b increases the risk of CHD [28, 29]. MMP-28 levels in circulation serve as a signpost for the immediate prognosis of MI patients [30]. A class of zinc ion-dependent proteases known as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) degrade collagen and proteoglycans and are essential for the development of AS [31]. MMPs are essential for both the development of unfavorable outcomes and the remodeling of the heart after MI [32] (table 1).

Table 1: Key biomarkers implicated in myocardial infarction: biological functions and clinical utility

| Biomarker | Biological function | Plaque instability | Clinical utility in MI | References |

| VEGF-A₁₆₅b | Anti-angiogenic isoform of VEGF-A; regulates vascular homeostasis | Inhibits pro-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms; dysregulation promotes endothelial dysfunction, enhancing platelet adhesion | Predicts infarct size; elevated in CHD and aging vessels | [33, 34, 29] |

| MMP-28 | ECM remodeling enzyme; degrades collagen and proteoglycans | Weakens fibrous cap of plaques, increasing rupture risk | Prognostic marker for post-MI outcomes | [35-37] |

| CK-MB | Myocardial isoenzyme; released during necrosis | Indicates myocardial injury, indirectly associated with thrombosis | Diagnostic biomarker for AMI in early phase | [38-40] |

| cTn | Cardiac troponin, released during myocyte injury | Necrosis triggered by thrombotic occlusion | Gold standard for AMI diagnosis and risk stratification | [41-43] |

| Myoglobin | Oxygen-binding protein, released quickly after injury | Very early marker; nonspecific to thrombotic process | Early rule-out tool; rapid kinetics | [44-46] |

Clinical diagnosis and therapeutic strategies of mi

Elevated cardiac troponin (cTn) levels, along with prolonged chest pain, electrocardiographic abnormalities, and regional wall motion defects, are key diagnostic indicators of recent-onset ischemia. Angiographic detection of a coronary thrombus also supports the clinical diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI) [47]. For suspected MI, the point-of-care hs-cTn I-Triage True test provides excellent diagnostic accuracy, comparable to or better than major laboratory-based assays [48].

Initial treatment includes oxygen, nitroglycerin to relieve chest discomfort, and aspirin to inhibit platelet aggregation [49]. Reperfusion therapy-achieved through thrombolytics, mechanical recanalization, or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (αIIbβ3) receptor inhibitors-is critical for restoring coronary blood flow and reducing mortality in ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) [50]. The current gold standard is primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), followed by stent deployment [51]. Despite significant improvements in door-to-balloon times, STEMI mortality has plateaued [52]. Consequently, emphasis has shifted toward reducing total ischemia time ‒from symptom onset to reperfusion [53].

Among αIIbβ3 inhibitors, abciximab is notable for its irreversible binding and prolonged platelet receptor occupancy, which increases the risk of bleeding and thrombocytopenia, thereby limiting its use primarily to high-risk PCI cases. In contrast, eptifibatide‒a reversible inhibitor with a shorter half-life, is preferred in many clinical settings due to a more favorable safety profile. Comparative studies in STEMI and NSTEMI cohorts undergoing PCI have demonstrated similar efficacy between abciximab and eptifibatide, but a lower incidence of major bleeding events with eptifibatide [54, 55].

Furthermore, pre-PCI administration of αIIbβ3 inhibitors has been shown to improve preprocedural infarct artery perfusion, accelerate ST-segment resolution, limit infarct size, and improve survival-effects that are observed regardless of concurrent P2Y₁₂ receptor inhibition [56, 57].

Role of molecular pathways for myocardial infarction

The PI3K/Akt, Notch, NLRP3/Caspase-1/IL-1β, TLR4/MYD88/NF-κβ, JAK/STAT, and TGF-β/SMAD Signalling pathways play critical roles in myocardial infarction (MI) by regulating inflammation, fibrosis, apoptosis, and myocardial repair. PI3K/Akt and Notch pathways promote cell survival and fibrosis inhibition, while NLRP3, TLR4, and JAK/STAT pathways contribute to inflammation, cytokine release, and tissue damage. The TGF-β/SMAD pathway drives myocardial fibrosis post-MI, making these Signalling mechanisms crucial therapeutic targets for managing MI outcomes (table 2).

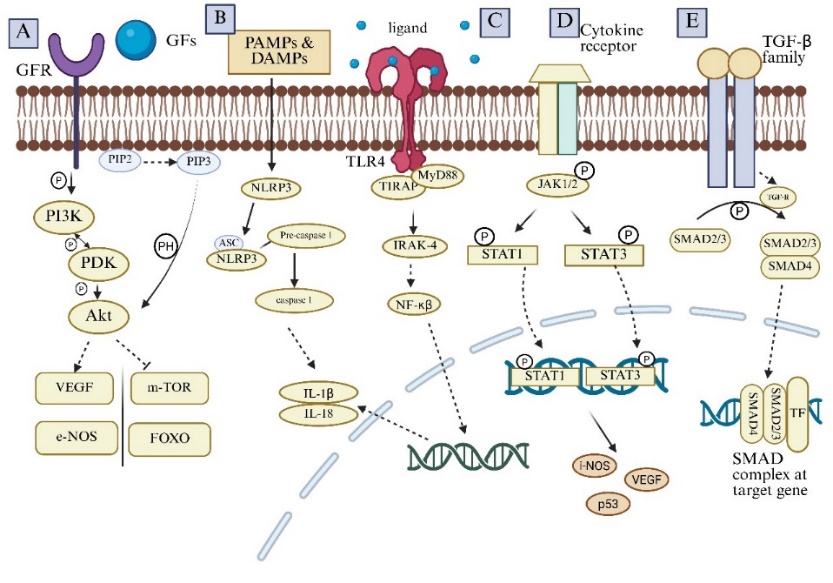

Role of PI3K/AKT pathway in myocardial infarction

Researchers have discovered that the PI3K/Akt pathway plays a crucial role in the development, progression, and management of MI [58]. Cellular stimuli, either internal or external, activate the components of this pathway [59]. It is linked to migration, apoptosis, survival, and other pathological or physiological processes according to a growing body of research [60]. Researchers believe that phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) negatively regulates PI3K/Akt by dephosphorylating Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) to Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) [61], thereby contributing to pathogenic events in the ischemic myocardium [62] (fig. 2A).

Role of NOTCH signalling pathway in myocardial Infarction

For cardiac fibrosis to develop, the Notch pathway is necessary. The production of α-SMA is directly regulated by activating the major effector CSL in vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells [63]. Numerous studies have shown that activating the Notch1 Signalling pathway prevents cardiac fibrosis [64]. Researchers have developed many treatments to explore the possibility of using miRNAs or stem cells to reduce fibrosis [65].

Role of NLRP3/CASPASE-1/IL-1β signalling pathway in myocardial infarction

Activating signal co-integrator (ASC) adaptor molecules bind to NLRP3 during activation, and the two molecules combine with pro-caspase-1. After transforming pro-caspase-1 into caspase-1, the NLRP3 inflammasome catalyzes the conversion of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms, IL-1β and IL-18 [66]. In the inflammatory response that follows myocardial infarction (MI), IL-1β and IL-18 control the production of cytokines, the recruitment of immune cells, and the turnover of extracellular matrix, leading to inflammation and tissue damage [67]. Mounting evidence shows that inflammatory responses following MI cause myocardial injury, repair, and scarring. These responses lead to leukocyte buildup, production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and myocardial damage [68] (fig. 2B).

Role of TLR4/MYD88/NF-κβ-Signalling pathway in myocardial infarction

Activated TLR4 increases proinflammatory cytokine expression, exacerbates the already damaged myocardium, and triggers inflammatory reactions [69]. Interestingly, there is no correlation between the degree of inflammation, the TLR4-Signalling pathways, and the severity of the infarct. Furthermore, a clinical investigation discovered that TLR4, miR-6778-3p, miR-520a-3p, miR-149-5p, and the platelet-activating factor receptor (PTAFR) all had an impact on the development of AMI from stable CAD [70] (fig. 2C).

Role of JAK/STAT signalling pathway in myocardial infarction

Researchers have demonstrated that persistent activation of STAT transcription factors-specifically STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5-contributes to various malignant changes [71]. By inducing nitric oxide synthesis via IL-6, the STAT3 target gene iNOS reduces cardiac contractility [72] (fig. 2D). Clinicians must carefully regulate JAK/STAT activation in MI patients and develop a well-defined treatment plan to balance JAK/STAT Signalling and shield the heart from pathophysiological stress [73].

Role of TGF-β/SMADs signalling pathway in myocardial infarction

At present, the human TGF-β family consists of the following proteins: TGF-β, growth and differentiation factor (GDF), inhibin, activin, and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) [74]. Following the binding of the TGF-β family to TGFβRII, cellular kinases phosphorylate certain serine and threonine residues on TGFβRI, leading to the formation of a heterocomplex [75]. The receptor complex regulates target gene transcription after interacting with the downstream effector SMAD proteins [76]. The TGF-β complex enters the nucleus as an R‒SMAD‒Co‒SMAD complex, transduces specific signals to control target gene transcription, and forms heteromers with Co‒SMADs and R‒SMADs to produce its biological effects [77]. Following MI, TGF-β/SMAD Signalling plays a role in myocardial fibrosis [78]. Following MI, cardiac fibroblasts initiate the TGF-β1/SMAD Signalling pathway and also release the pro-fibrotic cytokine TGF-β1 [79]. Furthermore, the expressions of TGF-β1 and downstream SMAD2/3/4 varyingly increase in the infarct and infarct perimeter areas [80] (fig. 2E).

Fig. 2: Various targeted pathways for myocardial infarction

Fig. 2A. PI3K/Akt pathway: The primary molecule in the process, Akt, is activated when PI3K changes PIP2 into PIP3. Finally, PDK phosphorylates Akt and controls cardiac recovery after MI by binding to the Pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of Akt. This process occurs via the downstream Signalling pathway.

Fig. 2B. NLRP3/CASPASE-1/IL-1β pathway: PAMPs and DAMPs activate NLRP3, and then it binds to ASC. NLRP3 convert pro-caspase 1 to caspase 1. This catalyzed Pro-IL-1β and Pro-IL-18 to IL-1β and IL-18.

Fig. 2C. TLR-4 pathway: When TLR4 detects its ligand, it attracts the MYD88 adaptor protein. MYD88 starts a sequence of intracellular Signalling processes upon binding. The NF-κβ is activated as a result of these events. Target gene transcription is started by NF-κβ once it is translocated to the nucleus.

Fig. 2D. JAK/STAT Signalling pathway: When cytokines attach to receptors, the receptor molecules dimerize, which then attract STAT protein towards the docking site formed by these phosphorylated tyrosine sites. When STATs are phosphorylated and activated, they can move to the nucleus, form dimers, and regulate gene expression.

Fig. 2E. TGF-β/SMADs signalling pathway: TGF-β ligands attach to the TGF receptor, phosphorylate SMAD2/3, and form the SMAD complex, which moves inside the cell nucleus and affects how certain genes are expressed.

Table 2: Summarization of various targeted pathways for myocardial infarction

| Pathways | Descriptions | Clinical prospections | References |

| PI3K/AKT Pathway | This pathway can influence the inflammatory response, which is a significant component of the healing process after a heart attack. | Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) | [81] |

| Notch Signalling Pathway | This pathway has been shown to promote cardiomyocyte survival. It may also promote angiogenesis in the heart, which is crucial for restoring blood supply to damaged areas after MI (MI). | Liraglutide | [82] |

| NLRP3/CasPase-1/IL-1β signalling Pathway | This pathway is part of the innate immune response. NLRP3 senses damage-associated molecular patterns released from injured cardiac cells. IL-1β and other pro-inflammatory cytokines are processed and activated by caspase-1. | NLRP3-inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 | [83] |

| TLR4/MYD88/NF-κβ signalling Pathway | After TLR4 recognizes its ligand, it recruits an adaptor protein called MYD88. After binding, MYD88 initiates a series of intracellular Signalling events. The stimulation of NF-κβ is the result of these events. After moving to the nucleus, NF-κβ starts the transcription of particular target genes. | Metformin and methotrexate | [84,85] |

| JAK/STAT Signalling Pathway | Activated JAKs phosphorylate STAT proteins, leading to their dimerization and activation. STAT acts as a transcription factor and regulates gene expression, which can influence the extent and duration of the inflammatory response following an MI. This pathway also affects processes like angiogenesis, fibrosis, and cell proliferation. | Ruxolitinib, Erythropoietin | [86,87] |

| TGF-β/SMADS Signalling Pathway | Activated TGF-β phosphorylates specific intracellular proteins called SMADs. The SMAD complex translocates inside the cell nucleus and influences the stimulation of specific genes. This pathway can influence the balance between tissue repair and pathological remodeling. | Simvastatin | [88] |

Novel targeted pathway for myocardial infarction

Basic of αIIbβ3 receptor

The α and β subunits of integrins, a significant class of transmembrane glycoproteins (GP) receptors, each possess a cytoplasmic domain, a transmembrane domain, and an extracellular domain [89]. One of the integrins in the β3 subfamily is αIIbβ3. There is a 36% sequence identity between the two components, αIIbβ3 and αVβ3, and they both share the same β3 subunit [90, 91]. Integrin αIIbβ3 is present on megakaryocytes, platelets, basophils, tumor cells, and mast cells [92]. Numerous studies and reviews have focused on the structure of αIIbβ3 and the fundamentals of the inside-out and outside-in Signalling pathways that activate αIIbβ3 and other integrins [93, 94]. Upon activation, αIIbβ3 functions as a receptor for ligands that can bind to other αIIbβ3 on nearby platelets. von Willebrand factor and fibrinogen are αIIbβ3 ligands that mediate this cross-bridging activity [95]. However, various αIIbβ3 ligands, including thrombospondin, vitronectin, fibronectin, and CD40 ligand, can alter platelet aggregation [96, 97]. It became evident that blocking αIIbβ3's ligand-binding function would prevent platelet aggregation and, thus, restrict the formation of thrombus as the molecular details demonstrating its crucial involvement in platelet aggregation came to light [97].

The physiology of αIIbβ3 receptor for myocardial infarction

Integrin αIIbβ3 or GPIIb/IIIa is essential for hemostasis and has about 80,000 copies per platelet [98]. A transmembrane domain, a thigh domain, two calf domains, a head, and a cytoplasmic tail, the primary ligand-binding region, make up the 1,008 amino acid α-subunit of αIIbβ3 [99, 100]. A cytoplasmic tail, the transmembrane a membrane-proximal β-tail domain (βTD domain), a total of four EGF domains, a hybrid domain, and a β3A domain are all present in the 762 amino acid β-subunit of αIIbβ3 [100, 101]. When activated, the disulfide-bonded single polypeptide chain that makes up the β3 subunit rearranges by producing free thiols through a disulfide exchange reaction [102].

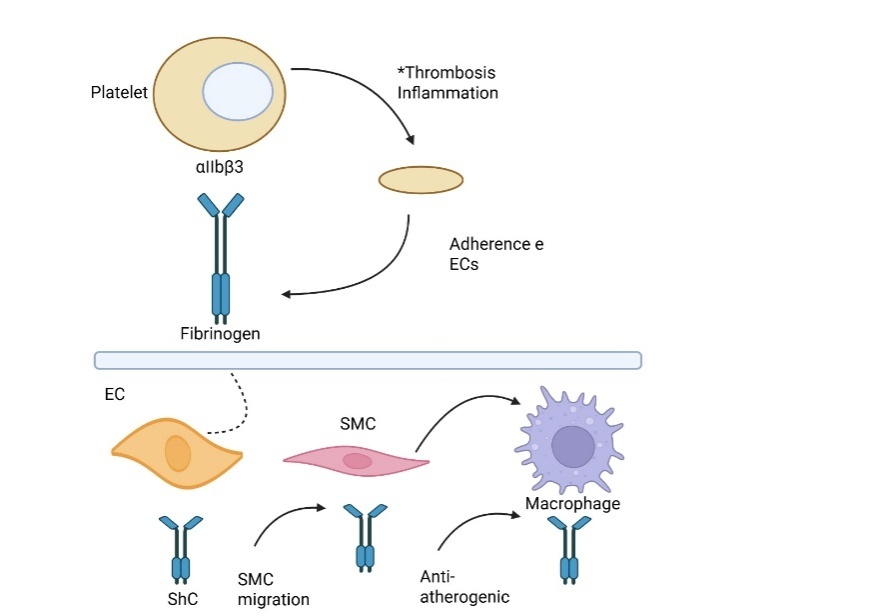

The expression of αIIbβ3 is inextricably linked to the activation of the platelet cascade. In resting platelets, αIIbβ3 is inactive [103]. However, upon activation of signal transduction within the platelets, fibrinogen binding and αIIbβ3 receptor activation further enhance platelet aggregation [104]. Inhibitors of platelet αIIbβ3 receptors have been shown in numerous clinical trials to be useful in treating and preventing unstable angina pectoris or MI caused by acute ischemic episodes [105]. It is currently debatable whether platelet αIIbβ3 promotes the formation of atherosclerotic plaques [106]. According to reports, animals predisposed to AS (LDL-R-null mice and ApoE-null) show increased vulnerability to atherosclerotic lesions and inflammation brought on by a high-fat diet in the absence of integrin β3 [107]. Subsequent investigations revealed that atherosclerotic lesions worsened after β3 deletion or β3_/_ bone marrow transplantation due to an increase in smooth muscle cells (SMCs) incorporated into the plaque. The authors suggest that the primary factor behind this progression is the loss of macrophage β3 [108]. Nonetheless, some reports refute the aforementioned research. This apparent contradiction may arise from the cell-specific functions of β3: while platelet β3 (as αIIbβ3) promotes thrombosis and inflammation, macrophage β3 may play an anti-atherogenic role by limiting SMC migration. Additionally, β3 integrin is shared between αIIbβ3 (platelets) and αvβ3 (monocytes, ECs, and SMCs), which may confound global knockout studies (fig. 3). Furthermore, αvβ3 is known to mediate platelet adhesion and promote lesion development, which complicates interpretation.

To resolve these discrepancies, future studies should employ cell-type-specific β3 deletions, combined with single-cell omics and in vivo imaging, to delineate the differential contributions of platelet vs. macrophage β3. Investigating functional redundancy between αIIbβ3 and αvβ3, as well as integrin cross-talk in atherosclerotic environments, will be essential to clarify their roles [109-111].

The interaction between soluble fibrinogen and αIIbβ3 is responsible for platelet adherence to ECs. Activated ECs cannot be securely adhered to by platelets deficient in αIIbβ3 [112]. Atherosclerotic lesions in the carotid artery and aortic arch were significantly reduced or absent in ApoE-/-mice deficient in GPIIb, indicating a potential role of GPIIb in the progression of AS. The authors speculate that this might be due to fewer platelets being recruited and sticking to active ECs [113]. In GPIIb or GPIIIa-deficient AS-prone mice, the degree of atherosclerotic lesions may be correlated with the vitronectin receptor αVβ3 [114]. Finally, αVβ3 has been detected on monocytes and vascular cells, while αIIbβ3 only functions on platelets and megakaryocytes. Furthermore, αVβ3 is necessary to promote platelet adhesion [115].

Fig. 3: Role of integrin αIIbβ3 and fibrinogen in thrombosis, inflammation, and vascular cell interactions

This diagram depicts the role of integrin αIIbβ3 in platelet adhesion, promoting thrombosis and inflammation. Fibrinogen acts as a key ligand, mediating interactions between platelets and endothelial cells (ECs). It also influences smooth muscle cell (SMC) migration and macrophage responses in the vascular wall. These interactions contribute to vascular remodeling and may play anti-atherogenic or pro-atherogenic roles depending on the cellular context.

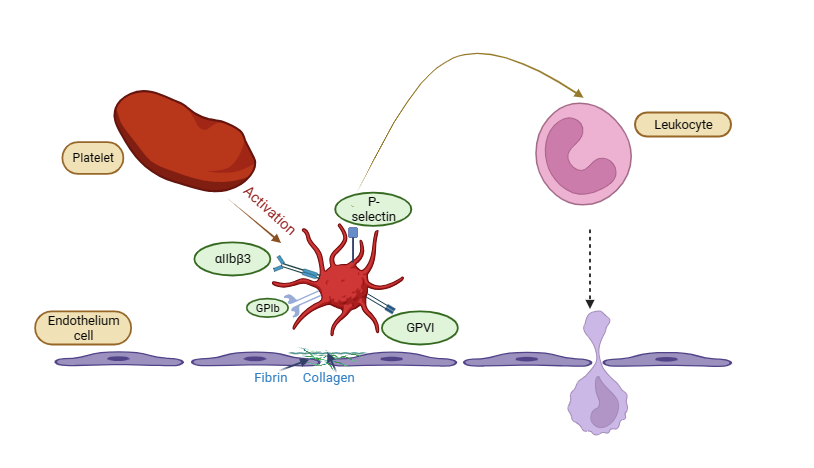

AS can be reduced by inhibiting αvβ3, which also suppresses inflammation and smooth muscle recruitment [116]. Platelets, as inflammatory mediators, work with ECs and leukocytes, particularly monocytes, to produce atherosclerotic lesions [117]. Numerous adhesion receptors are expressed by the activated platelets. After activation of platelets express multiple adhesion receptors that facilitate platelet adhesion by binding to matrix proteins. Receptors on endothelial cells (ECs) or leukocytes such as P‒selectin‒PSGL‒1 and Clec2‒PDPN interact with GPIb‒vWF, GPVI‒collagen, and GPIIb‒IIIa‒fibrinogen, promoting platelet attachment and clot formation. When platelets are activated, they also release other inflammatory chemicals, such as growth factors, chemokines, and cytokines [118] (fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Depicting the role of αIIbβ3 receptor in atherothrombotic plaque, platelet activation and adhesion to the endothelium, mediated by GPIb, GPVI, and αIIbβ3 receptors, which interact with fibrin and collagen. P-selectin on activated platelets facilitates leukocyte recruitment, contributing to inflammation and thrombosis. The leukocyte appears to migrate through the endothelial barrier, indicating an inflammatory response

MI occurs when an atherosclerotic plaque in a coronary artery becomes unstable [119]. The so-called atherothrombotic stroke is caused by a rupture of the plaque that exposes the necrotic core-the primary thrombogenic substrate-to the bloodstream. On the affected vascular surface, this sets off the clotting cascade and platelet activation, adhesion, and aggregation [120]. Therefore, the pathophysiology of MI is significantly influenced by platelet activation-dependent thrombus development, which adheres to a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque site. Platelets play active roles in early myocardial infarction (MI) by contributing to plaque disruption, thrombotic occlusion, vasoconstriction, intracanal thrombus formation, and inflammatory reactions in the ischemic myocardium [121]. Initiating thrombotic occlusion, which causes tissue damage within the ischemic myocardium's microcirculation and impedes cardiac recovery, is a critical function of platelets [122]. The severity of MI and cardiac contractile dysfunction is determined by these events [123]. Patients with acute MI experienced concurrent increases in plasma thioredoxin levels and platelet aggregability, which were linked to a decreased left ventricular ejection fraction [124]. Higher platelet reactivity is observed in patients with more extensive coronary AS, which may partially explain their increased risk of periprocedural MI [125]. Even with coronary stenting, about one-third of STEMI patients experience a "no-reflow" syndrome, which is linked to either insufficient or excessive platelet inhibition during MI [126]. Furthermore, these STEMI patients have shorter intervals between diagnosis and angiography and are more likely to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) after angiography [127]. Patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), especially those with STEMI, have significantly higher expression levels of platelet P-selectin, which are correlated with indicators of myocardial necrosis (creatine kinase-MB and troponin I) [128].

The current inhibitors acting on the αIIbβ3 receptor

A monoclonal antibody fragment called abciximab irreversibly and non-competitively blocks αIIbβ3 receptors. Selective, reversible antagonists of αIIbβ3 include tirofiban, a nonpeptide, and eptifibatide, a hexapeptide [129]. Several oral antagonists, including orbofiban, sibrafiban, xemilofiban, lotrafiban, and roxifiban, have previously been assessed [130, 131]. These have been linked to an increased incidence of thrombocytopenia, longer bleeding times, and increased mortality (including cardiovascular mortality) [132]. For myocardial infarction, these antagonists have been discontinued. The Fab segment of a mouse/human chimeric antibody is called abciximab (47.6 kDa). Abciximab binds to the integrin receptor's β3 chain, preventing ligands from accessing the binding pocket [133, 134]. Platelet function recovers within 24 to 36 h of treatment, but abciximab remains bound to platelets for two weeks by attaching primarily to the β3 subunit’s ligand-binding pocket and also to the KQAGDV sequence of the αIIb subunit [135, 136].

Abciximab blocks ligands' access to binding pockets via conformational effects or steric hindrance [137]. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that abciximab increased the risk of minor bleeding and thrombocytopenia in STEMI patients undergoing PCI but reduced short-term mortality, recurrent MI, revascularization, and improved myocardial perfusion [138]. The cyclic heptapeptide eptifibatide (Integrin; 832 Da) is derived from the disintegrin barbourin (P22827), a venomous substance of the southeastern pygmy rattlesnake, and has a homo-arginine–glycine–aspartic acid (hArg–Gly–Asp) sequence. Eptifibatide has a half-life of 2.5 h for plasma elimination [139]. Based on the KGD motif of barbourin, eptifibatide was created by substituting a homoarginine residue for lysine in order to increase affinity [140]. Eptifibatide inhibits the fibrinogen binding domain and stops platelet thrombi from forming by binding to the pocket between the αIIb and β3 subunits. Given that the binding site is situated within αIIbβ3's ligand-binding pocket [141, 142]. A study showed that, for a subset of STEMI patients receiving successful primary PCI, an eptifibatide bolus alone was non-inferior in terms of infarct size and reduced the risk of significant bleeding events by over 50%, bolus-plus-infusion treatment [143]. Bleeding is a common side effect of these medications, and thrombocytopenia is an uncommon but potentially fatal consequence due to the development of autoantibodies against these drugs. Prompt identification is essential to avoid worse outcomes [144].

Natural inhibitors acting on the αIIbβ3 receptor

A wide range of anticoagulant and antiplatelet proteins are expressed by bloodsucking parasites, including mosquitoes, ticks, insects, leeches, sand flies, hookworms, and bats, which interfere with the host's hemostatic system [145]. The venom found in the glands of snakes, particularly vipers (venomous snakes), is rich in proteins that alter blood coagulation, causing organ deterioration and widespread tissue damage [146].

Snakes such as Agkistrodon halys blomhoffi (basic), Vipera russelli, Naja nigricollis (basic), N. m. mossambica (CM-III), and Crotalus durissus terrificus have the ability to act as potent anticoagulants and inhibit blood coagulation [147-148].

Disintegrins such as echistatin, triflavin, and bitistatin, isolated from viperid snake venoms, exert their effects by binding to the RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) recognition site on platelet αIIbβ3 integrins, thereby blocking fibrinogen crosslinking and aggregation [149].

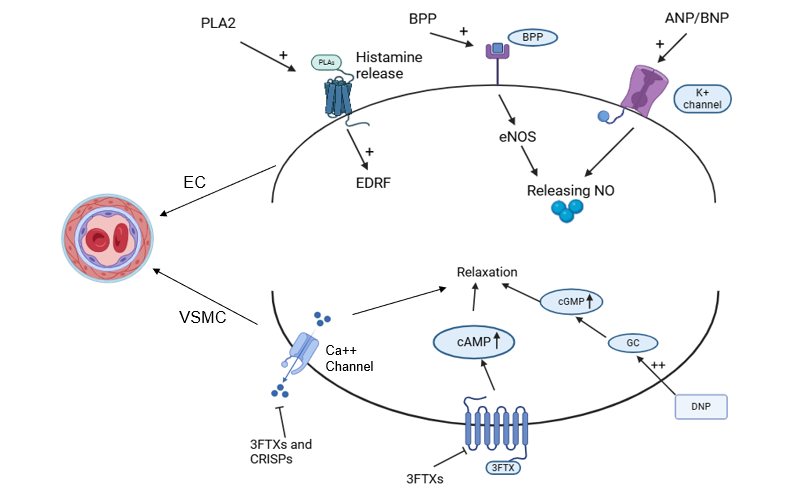

Numerous proteins found in snake venom, including PLA2, BPPs, ANP/BNP, 3FTXs, CRISPs, DNP, and others, affect blood vessels through vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells [150]. By blocking Ca²⁺ channels, activating K⁺ channels, or promoting the release of NO, they function as vasodilators. Various factors, such as blood flow, acetylcholine, bradykinin, and histamine, can cause endothelial cells (ECs) to release vasodilators [151]. Nitric oxide (NO) is released by ECs and diffuses into vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) [152]. After binding to several receptors such as H1, bradykinin, and K+channels, PLA2, BPPs, and ANP/BNP proteins promote the release of NO, which is produced by eNOS [153]. Increased amounts of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) result from NO activating soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) [154]. By phosphorylating Ca2+channels, decreasing Ca2+inflow, and activating K+channels, cGMP triggers protein kinase G (PKG), which results in hyperpolarization and relaxation [155] (fig. 5).

Despite these promising findings, several challenges hinder the clinical translation of these natural inhibitors. Their peptidic nature often results in poor oral bioavailability and susceptibility to enzymatic degradation, necessitating parenteral administration. Moreover, the potential immunogenicity of these compounds raises concerns about adverse immune responses upon repeated administration. Currently, there is a paucity of randomized clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of these natural inhibitors in humans, limiting their integration into standard therapeutic protocols [156].

Fig. 5: VSMC and ECs interaction by bioactives, the graph illustrates the mechanisms underlying blood vessel relaxation by concentrating on the interactions between endothelial cells (ECs) and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) in arteries as a result of PLA2, BPPs, ANP/BNP, 3FTXs, CRISPs, and DNP, respectively [125]

Herbal drugs in the treatment of myocardial infarction

Herbal drugs have been used for cardiovascular diseases since ancient times. Herbs are effective and low-risk options for treating myocardial infarction. Below are various herbal drugs that are used to treat myocardial infarction.

In the Atharvaveda, Numerous terrestrial plants, including Trigonella foenum-graecum L. (fenugreek), Curcuma longa L. (turmeric), Allium sativum L. (garlic), Commiphora mukul Engl. (guggul), Ocimum sanctum L. (tulsi), Allium cepa (onion), and Terminalia arjuna (arjuna) have been found to exhibit lipid-lowering and cardio-protective properties in an ancient treatise of Ayurveda, one of the Indian medical systems [157]. Lavender oil provides benefits such as reduced heart rate and blood pressure. It has a calming effect on the mind. Garlic is an effective remedy for chest discomfort in hypertensive patients, as well as those recovering from a heart attack. Turmeric's anti-inflammatory properties help alleviate chest pain, and long-term use may help prevent heart problems. Patients with AS who suffer from heart disease can benefit from brewed parsley leaf and fruit [158].

Future prospects of drug discovery for mi

More specialized and customized treatment plans could result from advancements in personalized medicine and genomics. Understanding the genetic components that contribute to myocardial infarction, such as genetic variations in genes like CYP2C19, which influence the metabolism of clopidogrel, a commonly prescribed antiplatelet medication-may facilitate the customization of therapies for individual patients, improving outcomes and mitigating side effects [159]. Research on using stem cells to repair injured cardiac tissue is highly promising, and the effectiveness and safety of various types of stem cells for heart repair are being investigated in clinical trials. Research is also being conducted on immune response modification to reduce inflammation and promote tissue recovery following a heart attack. Restorative therapies that modulate the immune system’s response could be useful in minimizing damage and accelerating healing. Maintaining mitochondrial health and function is essential for cellular energy synthesis and overall cell survival, and treatments to preserve mitochondrial function are currently under investigation.

CONCLUSION

The platelet surface receptor αIIbβ3-also referred to as integrin αIIbβ3 or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa-is essential for platelet aggregation and thrombus development. This heterodimeric transmembrane protein is present on the surface of platelets. When a myocardial infarction, also referred to as a heart attack, occurs, the αIIbβ3 receptor does not play a direct role in the initiation of the event. Rather, its importance is related to the later phases of thrombus development and the rupture of the atherosclerotic plaque. Collagen fibers in the arterial wall become visible when the plaque bursts, triggering a chain of events that activate platelets. Activated platelets adhere to the wound site and undergo further activation. Following activation, platelets undergo a process known as conformational shift, which enables them to express the surface αIIbβ3 receptor. Platelet aggregation depends on this receptor. The αIIbβ3 receptor binds to fibrinogen, allowing activated platelets to clump together and form a stable blood clot, with fibrinogen acting as a link between them. At the site of plaque rupture, the clumped platelets and fibrin network combine to form a thrombus (clot). This thrombus has the potential to completely or partially block blood flow through the affected artery. If the coronary artery is completely blocked by the thrombus, blood flow to a portion of the heart muscle may be drastically decreased or cease. This results in ischemia, or inadequate blood flow, which can eventually lead to a heart attack or myocardial infarction, the destruction of heart muscle tissue. It’s important to note that antiplatelet therapies, including aspirin and drugs targeting αIIbβ3 receptors, are commonly used in the treatment of heart attacks to prevent further clotting and reduce the risk of recurrence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the Department of Pharmacology, the Principal, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysuru for his support and for providing the necessary infrastructure to write this review.

FUNDING

Nil

ABBREVIATION

ACS: Acute coronary syndrome; BMI: body mass index; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; CK: Creatin kinase; cTn: cardiac troponin; CVD: Cardio-vascular disease; ECG: Electrocardiogram; ECs: Endothelial cells; e-NOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase; FOXO: Fork head box subfamily O; GFR: Growth factor receptor; GSK-3β: Glycogen synthase kinase 3β; hs-CRP: highly sensitive C-reactive protein; IHD: Ischemic Heart Disease.; IKK: IκB kinase; IL: Interleukin i-NOS: Inducible nitric oxide synthase; IRAK-4: IL-1 receptor-associated kinase-4 JAK: Janus kinase; LDL-C: Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; LOX: Lipoxygenase LRP: LDL receptor-related protein; MAPK: Mitogen-activated protein kinases; MI: Myocardial infarction; MMP: Matrix metalloproteinase; MSC: Mesenchymal Stem Cell; m-TOR: Mammalian target of rapamycin complex; NF-κβ: Nuclear factor-κB; NLR: NOD-like receptor; PDK: Phosphoinositide dependent kinase; PI3K: Phosphoinositide-3 kinase; PIP: Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PTEN: Phosphatase and tensin homolog; SMAD: Small mother against decapentaplegic; STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; TF: Transcriptional factor; TIRAP: Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adapter protein; TLR: Toll like receptor 4; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Abu Safana Biswas-Conceptualization, Writing – original draft collection of materials, collating the information and Software; Ganavi Bethanagere Ramesha-Writing – review and editing; Kamsagara Linganna Krishna-Conceptualization, Supervision; Bharat Jayaprakash Byalahunashi-Writing – review and editing; Seema Mehdi-Writing – review and editing; Suman Pathak-Writing – review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

Panda P, Verma HK, Lakkakula S, Merchant N, Kadir F, Rahman S. Biomarkers of oxidative stress tethered to cardiovascular diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022(1):9154295. doi: 10.1155/2022/9154295, PMID 35783193.

Smit M, Coetzee AR, Lochner A. The pathophysiology of myocardial ischemia and perioperative myocardial infarction. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34(9):2501-12. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2019.10.005, PMID 31685419.

Fathima SN. An update on myocardial infarction. Vol. 1. Current Research and Trends in Medical Science and Technology; 2021. p. 1-162.

Elsaka O. Pathophysiology investigations and management in cases of myocardial infarction. Asian J Adv Med Sci. 2022;4(1):1-14.

Sagheer U, Al Kindi S, Abohashem S, Phillips CT, Rana JS, Bhatnagar A. Environmental pollution and cardiovascular disease: Part 1 of 2: air pollution. JACC Adv. 2024;3(2):100805. doi: 10.1016/j.jacadv.2023.100805, PMID 38939391.

Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Hinderliter AL, Cole S, Lavie CJ. Cardiology and lifestyle medicine. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2023 Mar-Apr;77:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2023.04.004, PMID 37059409.

Sreeniwas Kumar A, Sinha N. Cardiovascular disease in India: A 360 degree overview. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020;76(1):1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2019.12.005, PMID 32020960.

Chong B, Jayabaskaran J, Jauhari SM, Chan SP, Goh R, Kueh MT. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: projections from 2025 to 2050. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2024:zwae281. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwae281, PMID 39270739.

Chadwick Jayaraj J, Davatyan K, Subramanian SS, Priya J. Epidemiology of myocardial infarction. In: Pamukcu B, editor. Myocardial infarction. IntechOpen; 2019. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.74768.

De Filippis EM, Collins BL, Singh A, Biery DW, Fatima A, Qamar A. Women who experience a myocardial infarction at a young age have worse outcomes compared with men: the mass general brigham YOUNG-MI registry. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(42):4127-37. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa662, PMID 33049774.

Kundu J, James KS, Hossain B, Chakraborty R. Gender differences in premature mortality for cardiovascular disease in India, 2017-18. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):547. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15454-9, PMID 36949397.

Mritunjay M, Ramavataram DV. Predisposing risk factors associated with acute MI (AMI): a review. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2021;15(2):406-17. doi: 10.37506/ijfmt.v15i2.14343.

Rathore A, Sharma AK, Murti Y, Bansal S, Kumari V, Snehi V. Medicinal plants in the treatment of myocardial infarction disease: a systematic review. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2024;20(4):e290424229484. doi: 10.2174/011573403X278881240405044328, PMID 38685783.

Islam MR, Nova TT, Momenuzzaman NA, Rabbi SN, Jahan I, Binder T. Prevalence of CYP2C19 and ITGB3 polymorphisms among Bangladeshi patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. Sage Open Med. 2021 Aug 26;9:20503121211042209. doi: 10.1177/20503121211042209, PMID 34471538.

Akram AW, Saba E, Rhee MH. Antiplatelet and antithrombotic activities of Lespedeza cuneata via pharmacological inhibition of integrin αIIbβ3, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT pathways and FeCl3-induced murine thrombosis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2024;2024(1):9927160. doi: 10.1155/2024/9927160, PMID 38370873.

De Luca G, Verburg A, Hof AV, Ten Berg J, Kereiakes DJ, Coller BS. Current and future roles of glycoprotein IIb–IIIa inhibitors in primary angioplasty for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Biomedicines. 2024;12(9):2023. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12092023, PMID 39335537.

Rai M, Sinha A, Roy S. A review on the chemical induced experimental model of cardiotoxicity. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2024 Jul 1;16(7):1-11. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2024v16i7.51028.

Severino P, D Amato A, Pucci M, Infusino F, Adamo F, Birtolo LI. Ischemic heart disease pathophysiology paradigms overview: from plaque activation to microvascular dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):8118. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218118, PMID 33143256.

Valikeserlis I, Athanasiou AA, Stakos D. Cellular mechanisms and pathways in myocardial reperfusion injury. Coron Artery Dis. 2021;32(6):567-77. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000997, PMID 33471478.

Jan B, Dar MI, Choudhary B, Basist P, Khan R, Alhalmi A. Cardiovascular diseases among Indian older adults: a comprehensive review. Cardiovasc Ther. 2024;2024(1):6894693. doi: 10.1155/2024/6894693, PMID 39742010.

Poredos P, Poredos AV, Gregoric I. Endothelial dysfunction and its clinical implications. Angiology. 2021;72(7):604-15. doi: 10.1177/0003319720987752, PMID 33504167.

Bai B, Yin H, Wang H, Liu F, Liang Y, Liu A. The combined effects of depression or anxiety with high sensitivity C-reactive protein in predicting the prognosis of coronary heart disease patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24(1):717. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-06158-4, PMID 39438827.

Gulati R, Behfar A, Narula J, Kanwar A, Lerman A, Cooper L. Acute myocardial infarction in young individuals. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(1):136-56. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.05.001, PMID 31902409.

Asl SK, Rahimzadegan M. The recent progress in the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction based on myoglobin biomarker: nano-aptasensors approaches. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2022 Mar 20;211:114624. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2022.114624, PMID 35123334.

Ghosh A, Datta P, Dhingra M. Higher levels of creatine kinase MB (CK-MB) than total creatine kinase (CK): a biochemistry reporting error or an indicator of other pathologies? Cureus. 2023;15(12):e50792. doi: 10.7759/cureus.50792, PMID 38239552.

Aydin S, Ugur K, Aydin S, Sahin I, Yardim M. Biomarkers in acute myocardial infarction: current perspectives. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2019 Jan 17;15:1-10. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S166157, PMID 30697054.

Bularga A, Lee KK, Stewart S, Ferry AV, Chapman AR, Marshall L. High sensitivity troponin and the application of risk stratification thresholds in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2019;140(19):1557-68. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.119.042866, PMID 31475856.

Rios Navarro C, Hueso L, Diaz A, Marcos Garces V, Bonanad C, Ruiz Sauri A. Implicacion de la isoforma antiangiogenica VEGF-A165b en la angiogenesis y la funcion sistolica tras un infarto de miocardio reperfundido. Revista Espanola De Cardiologia. 2021;74(2):131-9. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2020.03.029.

Kikuchi R, Stevens M, Harada K, Oltean S, Murohara T. Anti-angiogenic isoform of vascular endothelial growth factor a in cardiovascular and renal disease. Adv Clin Chem. 2019;88:1-33. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2018.10.001, PMID 30612603.

Wu Y, Pan N, An Y, Xu M, Tan L, Zhang L. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for myocardial infarction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:617277. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.617277, PMID 33614740.

Mierke CT. Bidirectional mechanical response between cells and their microenvironment. Front Phys. 2021 Oct 20;9:749830. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2021.749830.

Nielsen SH, Mouton AJ, De Leon Pennell KY, Genovese F, Karsdal M, Lindsey ML. Understanding cardiac extracellular matrix remodeling to develop biomarkers of mioutcomes. Matrix Biol. 2019;75:43-57. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2017.12.001.

Boudria A, Abou Faycal C, Jia T, Gout S, Keramidas M, Didier C. VEGF165b, a splice variant of VEGF-A, promotes lung tumor progression and escape from anti-angiogenic therapies through a β1 integrin/VEGFR autocrine loop. Oncogene. 2019;38(7):1050-66. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0486-7, PMID 30194450.

Kuppuswamy S, Annex BH, Ganta VC. Targeting anti-angiogenic VEGF165b-VEGFR1 signaling promotes nitric oxide independent therapeutic angiogenesis in preclinical peripheral artery disease models. Cells. 2022;11(17):2676. doi: 10.3390/cells11172676, PMID 36078086.

Luchian I, Goriuc A, Sandu D, Covasa M. The role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-13) in periodontal and peri-implant pathological processes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1806. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031806, PMID 35163727.

Olejarz W, Lacheta D, Kubiak Tomaszewska G. Matrix metalloproteinases as biomarkers of atherosclerotic plaque instability. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):3946. doi: 10.3390/ijms21113946, PMID 32486345.

De Leon Pennell KY, Iyer RP, Ma Y, Yabluchanskiy A, Zamilpa R, Chiao YA. The mouse heart attack research tool 1.0 database. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;315(3):H522-30. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00172.2018, PMID 29775405.

Jiang XT, Ding L, Huang X, Lei YP, Ke HJ, Xiong HF. Elevated CK-MB levels are associated with adverse clinical outcomes in acute pancreatitis: a propensity score matched study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Sep 8;10:1256804. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1256804, PMID 37746074.

Ghorbaninezhad F, Bakhshivand M, Saeedi H, Alizadeh N. The association of elevated levels of LDH and CK-MB with cardiac injury and mortality in COVID-19 patients. Immuno Analysis. 2022;2(1):8. doi: 10.34172/ia.2022.08.

Schneider U, Mukharyamov M, Beyersdorf F, Dewald O, Liebold A, Gaudino M. The value of perioperative biomarker release for the assessment of myocardial injury or infarction in cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022;61(4):735-41. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezab493, PMID 34791135.

Canty Jr JM. Myocardial injury troponin release and cardiomyocyte death in brief ischemia failure and ventricular remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022;323(1):H1-H15. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00093.2022, PMID 35559722.

Long B, Long DA, Tannenbaum L, Koyfman A. An emergency medicine approach to troponin elevation due to causes other than occlusion myocardial infarction. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(5):998-1006. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.12.007, PMID 31864875.

Muzyk P, Twerenbold R, Morawiec B, Ayala PL, Boeddinghaus J, Nestelberger T. Use of cardiac troponin in the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Kardiol Pol. 2020;78(11):1099-106. doi: 10.33963/KP.15585, PMID 32847343.

Adepu KK, Anishkin A, Adams SH, Chintapalli SV. A versatile delivery vehicle for cellular oxygen and fuels or metabolic sensor? A review and perspective on the functions of myoglobin. Physiol Rev. 2024;104(4):1611-42. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2023, PMID 38696337.

Asl SK, Rahimzadegan M. The recent progress in the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction based on myoglobin biomarker: nano-aptasensors approaches. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2022;211:114624. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2022.114624, PMID 35123334.

Mueller C, Mockel M, Giannitsis E, Huber K, Mair J, Plebani M. Use of copeptin for rapid rule out of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2018;7(6):570-6. doi: 10.1177/2048872617710791, PMID 28593800.

Michaud K, Basso C, d’Amati G, Giordano C, Kholova I, Preston SD. Diagnosis of myocardial infarction at autopsy: AECVP reappraisal in the light of the current clinical classification. Virchows Arch. 2020;476(2):179-94. doi: 10.1007/s00428-019-02662-1, PMID 31522288.

Boeddinghaus J, Nestelberger T, Koechlin L, Wussler D, Lopez Ayala P, Walter JE. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with point of care high sensitivity cardiac troponin I. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(10):1111-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.065, PMID 32164884.

Alkhaqani AL, Ali BR. Evidence based nursing care of patient with acute myocardial infarction: case report. Int J Nurs Health Sci. 2022;4(1):1-7. doi: 10.33545/26649187.2022.v4.i1a.31.

Vogel B, Claessen BE, Arnold SV, Chan D, Cohen DJ, Giannitsis E. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):39. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0090-3, PMID 31171787.

Vidal Cales P, Cepas Guillen PL, Brugaletta S, Sabate M. New interventional therapies beyond stenting to treat ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2021;8(9):100. doi: 10.3390/jcdd8090100, PMID 34564118.

Bansal SS, Bansal S, Swaroop C. Door to balloon time in St-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI): a prospective study. CA. 2022;11(3):10-6. doi: 10.9734/CA/2022/v11i330196.

Writing Committee Members, Lawton JS, Tamis Holland JE, Bangalore S, Bates ER, Beckie TM, Bischoff JM, Bittl JA, Cohen MG, Di Maio JM, Don CW. ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21-129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006.

Sharifi Rad J, Sharopov F, Ezzat SM, Zam W, Ademiluyi AO, Oyeniran OH. An updated review on glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors as antiplatelet agents: basic and clinical perspectives. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2023;30(2):93-107. doi: 10.1007/s40292-023-00562-9, PMID 36637623.

Capodanno D, Milluzzo RP, Angiolillo DJ. Intravenous antiplatelet therapies (glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors and cangrelor) in percutaneous coronary intervention: from pharmacology to indications for clinical use. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;13:1753944719893274. doi: 10.1177/1753944719893274, PMID 31823688.

Hu X, Wang W, Ye J, Lin Y, Yu B, Zhou L. Effect of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor duration on the clinical prognosis of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with no-/slow-reflow phenomenon. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Nov;143:112196. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112196, PMID 34560551.

Redfors B, Dworeck C, Haraldsson I, Angeras O, Odenstedt J, Ioanes D. Pretreatment with P2Y12 receptor antagonists in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report from the swedish coronary angiography and angioplasty registry. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(15):1202-10. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz069, PMID 30851037.

Ghafouri Fard S, Khanbabapour Sasi A, Hussen BM, Shoorei H, Siddiq A, Taheri M. Interplay between PI3K/AKT pathway and heart disorders. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49(10):9767-81. doi: 10.1007/s11033-022-07468-0, PMID 35499687.

Yue Z, Chen J, Lian H, Pei J, Li Y, Chen X. PDGFR-β signaling regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and myocardial regeneration. Cell Rep. 2019;28(4):966-978.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.065, PMID 31340157.

Miricescu D, Totan A, Stanescu Spinu II, Badoiu SC, Stefani C, Greabu M. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in breast cancer: from molecular landscape to clinical aspects. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):173. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010173, PMID 33375317.

Wang Q, Wang J, Xiang H, Ding P, Wu T, Ji G. The biochemical and clinical implications of phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten in different cancers. Am J Cancer Res. 2021;11(12):5833-55. doi: 10.7150/ajcr.64841, PMID 35018228.

Feng Q, Li X, Qin X, Yu C, Jin Y, Qian X. PTEN inhibitor improves vascular remodeling and cardiac function after myocardial infarction through PI3k/Akt/VEGF signaling pathway. Mol Med. 2020;26(1):111. doi: 10.1186/s10020-020-00241-8, PMID 33213359.

Kachanova O, Lobov A, Malashicheva A. The role of the notch signaling pathway in recovery of cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(20):12509. doi: 10.3390/ijms232012509, PMID 36293363.

Peng X, Wang S, Chen H, Chen M. Role of the Notch1 signaling pathway in ischemic heart disease (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2023;51(3):27. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2023.5230, PMID 36799152.

Zhou Q, Rong C, Gu T, Li H, Wu L, Zhuansun X. Mesenchymal stem cells improve liver fibrosis and protect hepatocytes by promoting microRNA-148a-5p-mediated inhibition of Notch signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):354. doi: 10.1186/s13287-022-03030-8, PMID 35883205.

Kelley N, Jeltema D, Duan Y, He Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome: an overview of mechanisms of activation and regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(13):3328. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133328, PMID 31284572.

Abbate A, Toldo S, Marchetti C, Kron J, Van Tassell BW, Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 and the inflammasome as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2020;126(9):1260-80. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.120.315937, PMID 32324502.

Kologrivova I, Shtatolkina M, Suslova T, Ryabov V. Cells of the immune system in cardiac remodeling: main players in resolution of inflammation and repair after myocardial infarction. Front Immunol. 2021 Apr 2;12:664457. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.664457, PMID 33868315.

Xiao Z, Kong B, Yang H, Dai C, Fang J, Qin T. Key player in cardiac hypertrophy emphasizing the role of toll-like receptor 4. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020 Nov 26;7:579036. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.579036, PMID 33324685.

Xiao SJ, Zhou YF, Wu Q, Ma WR, Chen ML, Pan DF. Uncovering the differentially expressed genes and pathways involved in the progression of stable coronary artery disease to acute myocardial infarction using bioinformatics analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(1):301-12. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202101_24396, PMID 33506919.

Verhoeven Y, Tilborghs S, Jacobs J, De Waele J, Quatannens D, Deben C. The potential and controversy of targeting STAT family members in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;60:41-56. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.10.002, PMID 31605750.

Harhous Z, Booz GW, Ovize M, Bidaux G, Kurdi M. An update on the multifaceted roles of STAT3 in the heart. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019 Oct 25;6:150. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00150, PMID 31709266.

Billah M, Ridiandries A, Allahwala UK, Mudaliar H, Dona A, Hunyor S. Remote ischemic preconditioning induces cardioprotective autophagy and signals through the IL-6-dependent JAK-STAT pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(5):1692. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051692, PMID 32121587.

Tzavlaki K, Moustakas A. TGF-β signaling. Biomolecules. 2020;10(3):487. doi: 10.3390/biom10030487, PMID 32210029.

Annett S, Moore G, Robson T. FK506 binding proteins and inflammation related signalling pathways; basic biology current status and future prospects for pharmacological intervention. Pharmacol Ther. 2020 Nov;215:107623. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107623, PMID 32622856.

Lai LY, Gracie NP, Gowripalan A, Howell LM, Newsome TP. SMAD proteins: mediators of diverse outcomes during infection. Eur J Cell Biol. 2022;101(2):151204. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2022.151204, PMID 35131661.

Ahuja S, Zaheer S. Multifaceted TGF-β signaling a master regulator: from bench to bedside intricacies and complexities. Cell Biol Int. 2024;48(2):87-127. doi: 10.1002/cbin.12097, PMID 37859532.

Hanna A, Frangogiannis NG. The role of the TGF-β superfamily in myocardial infarction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019 Sep 18;6:140. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00140, PMID 31620450.

Saadat S, Noureddini M, Mahjoubin Tehran M, Nazemi S, Shojaie L, Aschner M. Pivotal role of TGF-β/Smad signaling in cardiac fibrosis: non-coding RNAs as effectual players. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020 Jan 20;7:588347. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.588347, PMID 33569393.

Carver W, Fix E, Fix C, Fan D, Chakrabarti M, Azhar M. Effects of emodin a plant derived anthraquinone on TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblast activation and function. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236(11):7440-9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30416, PMID 34041746.

Zhuang Z, Yu D, Yi X, Xiao D, Jiang S, He R. Phosphatase and tensin homolog regulates arthro fibrotic myofibroblast proliferation via PI3K/AKT signalling pathways. Chin J Tissue Eng Res. 2019;23(5):767. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.0541.

Saad MA, Eltarzy MA, Abdel Salam RM, Ahmed MA. Liraglutide mends cognitive impairment by averting Notch signaling pathway overexpression in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Life Sci. 2021 Jan 15;265:118731. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118731, PMID 33160995.

Wu D, Chen Y, Sun Y, Gao Q, Li H, Yang Z. Target of MCC950 in inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation: a literature review. Inflammation. 2020;43(1):17-23. doi: 10.1007/s10753-019-01098-8, PMID 31646445.

Feng YY, Wang Z, Pang H. Role of metformin in inflammation. Mol Biol Rep. 2023;50(1):789-98. doi: 10.1007/s11033-022-07954-5, PMID 36319785.

Ismail R, Habib HA, Anter AF, Amin A, Heeba GH. Modified citrus pectin ameliorates methotrexate induced hepatic and pulmonary toxicity: role of Nrf2, galectin-3/TLR-4/NF-κB/TNF-α and TGF-β signaling pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2025 Jan 23;16:1528978. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1528978, PMID 39917614.

Delen E, Doganlar O. The dose dependent effects of ruxolitinib on the invasion and tumorigenesis in gliomas cells via inhibition of interferon gamma depended JAK/STAT signaling pathway. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2020;63(4):444-54. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2019.0252, PMID 32492985.

Luo Y, Ali T, Liu Z, Gao R, Li A, Yang C. EPO prevents neuroinflammation and relieves depression via JAK/STAT signaling. Life Sci. 2023;333:122102. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.122102, PMID 37769806.

Tang B, Kang P, Zhu L, Xuan L, Wang H, Zhang H. Simvastatin protects heart function and myocardial energy metabolism in pulmonary arterial hypertension induced right heart failure. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2021;53(1):1-12. doi: 10.1007/s10863-020-09867-z, PMID 33394312.

Arnaout MA. The integrin receptors: from discovery to structure to medicines. Immunol Rev. 2025;329(1):e13433. doi: 10.1111/imr.13433, PMID 39724488.

Kaneva VN, Martyanov AA, Morozova DS, Panteleev MA, Sveshnikova AN. Platelet integrin αIIbβ3: mechanisms of activation and clustering; involvement into the formation of the thrombus heterogeneous structure. Biochem Moscow Suppl Ser A. 2019;13(2):97-110. doi: 10.1134/S1990747819010033.

Litvinov RI, Mravic M, Zhu H, Weisel JW, DeGrado WF, Bennett JS. Unique transmembrane domain interactions differentially modulate integrin αvβ3 and αIIbβ3 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(25):12295-300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904867116, PMID 31160446.

Xin H, Huang J, Song Z, Mao J, Xi X, Shi X. Structure signal transduction activation and inhibition of integrin αIIbβ3. Thromb J. 2023 Feb 13;21(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12959-023-00463-w, PMID 36782235.

Huang J, Li X, Shi X, Zhu M, Wang J, Huang S. Platelet integrin αIIbβ3: signal transduction regulation and its therapeutic targeting. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0709-6, PMID 30845955.

Ludhiadch A, Muralidharan A, Balyan R, Munshi A. The molecular basis of platelet biogenesis activation aggregation and implications in neurological disorders. Int J Neurosci. 2020;130(12):1237-49. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2020.1732372, PMID 32069430.

Cognasse F, Duchez AC, Audoux E, Ebermeyer T, Arthaud CA, Prier A. Platelets as key factors in inflammation: focus on CD40L/CD40. Front Immunol. 2022 Feb 3;13:825892. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.825892, PMID 35185916.

Montecino Garrido H, Trostchansky A, Espinosa Parrilla Y, Palomo I, Fuentes E. How protein depletion balances thrombosis and bleeding risk in the context of platelet’s activatory and negative signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(18):10000. doi: 10.3390/ijms251810000, PMID 39337488.

Van Den Kerkhof DL, Van Der Meijden PE, Hackeng TM, Dijkgraaf I. Exogenous integrin αIIbβ3 inhibitors revisited: past present and future applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(7):3366. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073366, PMID 33806083.

Ma Q, Dong J, Hindman B. Integrins: form and role in myofibroblast differentiation and function. In: Myofibroblasts: origins, function and role in disease. Nova Science Publishers; 2016.

Ahmed MU. Role of GPVI/fibrinogen interplay in platelet activation, thrombus formation and stability. Strasbourg, France: Universite de Strasbourg; 2020.

Hashemzadeh M, Haseefa F, Peyton L, Shadmehr M, Niyas AM, Patel A. A comprehensive review of the ten main platelet receptors involved in platelet activity and cardiovascular disease. Am J Blood Res. 2023;13(6):168-88. doi: 10.62347/NHUV4765, PMID 38223314.

Jiang L, Yuan C, Flaumenhaft R, Huang M. Recent advances in vascular thiol isomerases: insights into structures functions in thrombosis and antithrombotic inhibitor development. Thromb J. 2025;23(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s12959-025-00699-8, PMID 39962537.

Wang L, Tang C. Targeting platelet in atherosclerosis plaque formation: current knowledge and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24):9760. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249760, PMID 33371312.

Zhang Y, Ehrlich SM, Zhu C, Du X. Signaling mechanisms of the platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX complex. Platelets. 2022;33(6):823-32. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2022.2071852, PMID 35615944.

Flora GD, Nayak MK. A brief review of cardiovascular diseases, associated risk factors and current treatment regimes. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;25(38):4063-84. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190925163827, PMID 31553287.

Gawaz M, Geisler T, Borst O. Current concepts and novel targets for antiplatelet therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20(9):583-99. doi: 10.1038/s41569-023-00854-6, PMID 37016032.

Ilyas I, Little PJ, Liu Z, Xu Y, Kamato D, Berk BC. Mouse models of atherosclerosis in translational research. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2022;43(11):920-39. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2022.06.009, PMID 35902281.

Misra A, Feng Z, Chandran RR, Kabir I, Rotllan N, Aryal B. Integrin beta3 regulates clonality and fate of smooth muscle derived atherosclerotic plaque cells. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2073. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04447-7, PMID 29802249.

Lariviere M, Bonnet S, Lorenzato C, Laroche Traineau J, Ottones F, Jacobin-Valat MJ. Recent advances in the molecular imaging of atherosclerosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2020;46(5):563-86. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1701019, PMID 32604420.

Hsia CW, Huang WC, Jayakumar T, Hsia CH, Hou SM, Chang CC. Garcinol acts as a novel integrin αIIbβ3 inhibitor in human platelets. Life Sci. 2023;326:121791. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121791, PMID 37211346.

Lickert S, Kenny M, Selcuk K, Mehl JL, Bender M, Früh SM. Platelets drive fibronectin fibrillogenesis using integrin αIIbβ3. Sci Adv. 2022;8(10):eabj8331. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj8331, PMID 35275711.

Jain M, Chauhan AK. Role of integrins in modulating smooth muscle cell plasticity and vascular remodeling: from expression to therapeutic implications. Cells. 2022;11(4):646. doi: 10.3390/cells11040646, PMID 35203297.

Gao B, Xu J, Zhou J, Zhang H, Yang R, Wang H. Multifunctional pathology mapping theranostic nanoplatforms for US/MR imaging and ultrasound therapy of atherosclerosis. Nanoscale. 2021;13(18):8623-38. doi: 10.1039/D1NR01096D, PMID 33929480.

Filippi A, Constantin A, Alexandru N, Voicu G, Constantinescu CA, Rebleanu D. Integrins α4β1 and αVβ3 are reduced in endothelial progenitor cells from diabetic dyslipidemic mice and may represent new targets for therapy in aortic valve disease. Cell Transplant. 2020 Jan-Dec;29:963689720946277. doi: 10.1177/0963689720946277, PMID 32841051.

Li Y, Gao Q, Shu X, Xiao L, Yang Y, Pang N. Antagonizing αvβ3 integrin improves ischemia mediated vascular normalization and blood perfusion by altering macrophages. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Feb 24;12:585778. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.585778, PMID 33716733.

Yurdagul Jr A. Crosstalk between macrophages and vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerotic plaque stability. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42(4):372-80. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.121.316233, PMID 35172605.

Dziedzic A, Bijak M. Interactions between platelets and leukocytes in pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2019;28(2):277-85. doi: 10.17219/acem/83588, PMID 30411550.

Romanova VO, Kuzminova NV, Romanova LO, Lozinsky SE, Knyazkova II, Kulchytska OM. Indicators of nonspecific systemic inflammation as criteria for destabilization of the course of coronary artery disease. WOMAB. 2022;18(82):153-7. doi: 10.26724/2079-8334-2022-4-82-153-157.

Lordan R, Tsoupras A, Zabetakis I. Platelet activation and prothrombotic mediators at the nexus of inflammation and atherosclerosis: potential role of antiplatelet agents. Blood Rev. 2021;45:100694. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2020.100694, PMID 32340775.

Fuentes E, Moore Carrasco R, De Andrade Paes AM, Trostchansky A. Role of platelet activation and oxidative stress in the evolution of myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2019;24(6):509-20. doi: 10.1177/1074248419861437, PMID 31280622.

Ziegler M, Wang X, Peter K. Platelets in cardiac ischaemia/reperfusion injury: a promising therapeutic target. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115(7):1178-88. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz070, PMID 30906948.

Walsh TG, Poole AW. Do platelets promote cardiac recovery after myocardial infarction: roles beyond occlusive ischemic damage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;314(5):H1043-8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00134.2018, PMID 29547023.

Kei CY, Singh K, Dautov RF, Nguyen TH, Chirkov YY, Horowitz JD. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: evolving understanding of pathophysiology clinical implications and potential therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(14):11287. doi: 10.3390/ijms241411287, PMID 37511046.

Soud M, Ho G, Hideo Kajita A, Yacob O, Waksman R, McFadden EP. Periprocedural myocardial injury: pathophysiology prognosis and prevention. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21(8):1041-52. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.04.011, PMID 32586745.

Zuccarelli V, Andreaggi S, Walsh JL, Kotronias RA, Chu M, Vibhishanan J. Treatment and care of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction-what challenges remain after three decades of primary percutaneous coronary intervention? J Clin Med. 2024;13(10):2923. doi: 10.3390/jcm13102923, PMID 38792463.

Burlacu A, Tinica G, Artene B, Simion P, Savuc D, Covic A. Peculiarities and consequences of different angiographic patterns of STEMI patients receiving coronary angiography only: data from a large primary PCI registry. Emerg Med Int. 2020;2020(1):9839281. doi: 10.1155/2020/9839281, PMID 32765909.

Udaya R, Sivakanesan R. Synopsis of biomarkers of atheromatous plaque formation rupture and thrombosis in the diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2022;18(5):53-62. doi: 10.2174/1573403X18666220411113450, PMID 35410616.

Khatib R, Wilson F. Pharmacology of medications used in the treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. In: Encyclopedia of cardiovascular research and medicine. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2018. p. 68-88. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809657-4.99756-4.

Lin FY, Li J, Xie Y, Zhu J, Huong Nguyen TT, Zhang Y. A general chemical principle for creating closure stabilizing integrin inhibitors. Cell. 2022;185(19):3533-3550.e27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.08.008, PMID 36113427.

Tonin G, Klen J. Eptifibatide an older therapeutic peptide with new indications: from clinical pharmacology to everyday clinical practice. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5446. doi: 10.3390/ijms24065446, PMID 36982519.

Rikken SA, Van ’t Hof AW, Ten Berg JM, Kereiakes DJ, Coller BS. Critical analysis of thrombocytopenia associated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and potential role of zalunfiban a novel small molecule glycoprotein inhibitor in understanding the mechanism(s). J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(24):e031855. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.123.031855, PMID 38063187.

Stoffer K, Bistas KG, Reddy V, Shah S. Abciximab. In: Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Nesic D, Zhang Y, Spasic A, Li J, Provasi D, Filizola M. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the αIIbβ3-abciximab complex. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(3):624-37. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313671, PMID 31969014.

Yang M, Kholmukhamedov A. Platelet reactivity in dyslipidemia: atherothrombotic signaling and therapeutic implications. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021;22(1):67-81. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2021.01.256, PMID 33792249.

Janus Bell E, Mangin PH. The relative importance of platelet integrins in hemostasis thrombosis and beyond. Haematologica. 2023;108(7):1734-47. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2022.282136, PMID 36700400.

Wang L, Wang J, Li J, Walz T, Coller BS. An αIIbβ3 monoclonal antibody traps a semiextended conformation and allosterically inhibits large ligand binding. Blood Adv. 2024;8(16):4398-409. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2024013177, PMID 38968144.

Bai N, Niu Y, Ma Y, Shang YS, Zhong PY, Wang ZL. Evaluate short term outcomes of abciximab in st-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Interv Cardiol. 2022;2022(1):3911414. doi: 10.1155/2022/3911414, PMID 35685429.

Oliveira IS, Manzini RV, Ferreira IG, Cardoso IA, Bordon KC, Machado AR. Cell migration inhibition activity of a non-RGD disintegrin from Crotalus durissus collilineatus venom. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2018 Oct;24:28. doi: 10.1186/s40409-018-0167-6, PMID 30377432.

Fischer F, Buxy S, Kurz DJ, Eberli FR, Senn O, Zbinden R. Efficacy and safety of abbreviated eptifibatide treatment in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2021 Jan 15;139:15-21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.09.054, PMID 33065082.

Mahajan P, Ayub F, Azimi R, Adoni N. Eptifibatide induced profound thrombocytopaenia: a rare complication. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(6):e241594. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-241594, PMID 34127501.

Islam A, Emran TB, Yamamoto DS, Iyori M, Amelia F, Yusuf Y. Anopheline antiplatelet protein from mosquito saliva regulates blood feeding behavior. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):3129. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39960-2, PMID 30816309.

Huang J, Song W, Hua H, Yin X, Huang F, Alolga RN. Antithrombotic and anticoagulant effects of a novel protein isolated from the venom of the Deinagkistrodon acutus snake. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;138:111527. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111527, PMID 33773469.

Tan CH, Tan KY, Ng TS, Tan NH, Chong HP. De novo venom gland transcriptome assembly and characterization for Calloselasma rhodostoma (Kuhl, 1824), the Malayan pit viper from Malaysia: unravelling toxin gene diversity in a medically important basal crotaline. Toxins. 2023;15(5):315. doi: 10.3390/toxins15050315, PMID 37235350.

Kolvekar N, Bhattacharya N, Mondal S, Sarkar A, Chakrabarty D. Daboialipase a phospholipase A2 from vipera russelli russelli venom posesses anti-platelet, anti-thrombin and anti-cancer properties. Toxicon. 2024;239:107632. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2024.107632, PMID 38310691.

Nafiseh NN, Hossein V, Nasser MD, Mojtaba N, Minoo A, Mohammad Ali B. Analysis and identification of putative novel peptides purified from Iranian endemic Echis carinatus Sochureki snake venom by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Arch Razi Inst. 2023;78(5):1503-27. doi: 10.22092/ARI.2023.78.5.1503, PMID 38590689.

Pushpa Arokia Rani A, Serena MC Connell M. Snake venom. In: Manjur Shah M, Sharif U, Rufai Buhari T, Sabiu Imam T, editors. Snake venom and ecology. IntechOpen; 2022. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.101716.

Frangieh J, Rima M, Fajloun Z, Henrion D, Sabatier JM, Legros C. Snake venom components: tools and cures to target cardiovascular diseases. Molecules. 2021;26(8):2223. doi: 10.3390/molecules26082223, PMID 33921462.

Jackson WF. Calcium dependent ion channels and the regulation of arteriolar myogenic tone. Front Physiol. 2021 Nov 8;12:770450. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.770450, PMID 34819877.

Mendez Barbero N, Gutierrez Munoz C, Blanco Colio LM. Cellular crosstalk between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in vascular wall remodeling. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(14):7284. doi: 10.3390/ijms22147284, PMID 34298897.

Cesar PH, Braga MA, Trento MV, Menaldo DL, Marcussi S. Snake venom disintegrins: an overview of their interaction with integrins. Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20(4):465-77. doi: 10.2174/1389450119666181022154737, PMID 30360735.

Krishnan SM, Kraehling JR, Eitner F, Benardeau A, Sandner P. The impact of the nitric oxide (NO)/soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) signaling cascade on kidney health and disease: a preclinical perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1712. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061712, PMID 29890734.

Holland NA, Francisco JT, Johnson SC, Morgan JS, Dennis TJ, Gadireddy NR. Cyclic nucleotide directed protein kinases in cardiovascular inflammation and growth. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2018;5(1):6. doi: 10.3390/jcdd5010006, PMID 29367584.

Upadhyay RK. Antihyperlipidemic and cardioprotective effects of plant natural products: a review. Int J Green Pharm. 2021 Apr 9;15(1):1-19. doi: 10.22377/ijgp.v15i1.3011.