Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 67-77Reviewl Article

PHYTOSOME TECHNOLOGY IN CANCER TREATMENT ENHANCES THE BIOAVAILABILITY OF SECONDARY METABOLITES

MUJIBULLAH SHEIKH1*, ZOYA SHEIKH1, ARFANA SHEIKH1, MAHIN KHAN1, VAISHNAVI SHETE1

Department of Pharmaceutics, Datta Meghe College of Pharmacy DMIHER (Deemed to be University), Wardha, Maharashtra-442001, India

*Corresponding author: Mujibullah Sheikh; *Email: mujib123sheikh@gmail.com

Received: 20 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 09 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Phytosome technology represents a major breakthrough in the delivery of plant-derived secondary metabolites for cancer therapy, addressing fundamental limitations such as poor aqueous solubility, rapid metamorphosis, and reduced bioavailability, which hinders clinical translation. The secondary metabolites flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolic resins exhibit potent anticancer activities by modulating crucial oncogenic nerve pathways e. g., NF-κB (Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells), PI3K (Phosphoinositide 3-kinase), causing apoptosis and inhibiting angiogenesis. However, their hydrophobic nature and volatility in the physiological environment limit their curative efficacy. Phytosomes, which are molecular complexes containing phytochemicals and phospholipids, increase lipid solubility, prevent bioactive compounds from degrading, and facilitate target delivery to the tumor, resulting in refined absorption, dispersed circulation, and reduced systemic toxicity. Preclinical studies have shown that phytosome encapsulation can increase anticancer activity by up to fivefold and synergizes with conventional chemotherapeutics, resulting in increased efficacy in breast and colorectal tumor models. This review critically examines the structural and mechanistic foundations of phytosome technology, its application in improving the pharmacokinetics and therapeutic indices of secondary metabolites, and recent innovations, including nanoparticle incorporation and codelivery systems. By integrating metabolomic profiling with nanocarrier design, phytosomes hold promise as a cornerstone for next-generation, natural product-based precision oncology, overcoming bioavailability barriers and potentiating anticancer effects to advance clinical translation.

Keywords: Phytosome technology, Secondary metabolites, Bioavailability, Cancer pathways, Targeted delivery, Preclinical efficacy

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.54665 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Cancer remains one of the most formidable global health challenges, with an estimated 29.5 million new cases and 16.4 million deaths projected annually by 2040 [1]. Cancer biology, characterized by uncontrolled proliferation, metastasis and resistance to conventional therapies, requires innovative treatment approaches. Unfortunately, while the backbones of oncology, chemotherapy and radiation have various systemic toxicities, off-target effects, and drug and metal resistance, the need for more effective, safer alternatives remains urgent [2, 3]. Plant-derived secondary metabolites, such as flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids and phenolic compounds, have become promising candidates because they modulate important oncogene pathways, induce apoptosis, and inhibit angiogenesis [4]. However, their clinical translation is hindered by intrinsic limitations such as poor aqueous solubility, rapid metabolism and low bioavailability, which impede their clinical translation due to the inability to administer efficacious doses at the pharmacokinally achievable doses [5, 6].

A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, focusing on studies published between January 2010 and March 2025. Keywords such as “phytosome technology,” “secondary metabolites,” “bioavailability,” “cancer therapy,” and “nanocarriers” were used. Only peer-reviewed articles, reviews, and patents related to phytosome technology in cancer treatment were included, while non-English publications and studies unrelated to cancer or lacking methodological detail were excluded. This approach ensured the inclusion of high-quality, relevant literature for this review

Secondary metabolites such as quercetin, curcumin and berberine have very robust anticancer activity against preclinical models that target survival and progression pathway(s), such as NF-κB and PI3K/AKT [7]. Nevertheless, however, they are often hydrophobic and unstable in physiological environments, which limits formulation design and compromises the risk of adverse effects at high doses. Various traditional delivery methods, such as liposomes and surfactant-based systems, have proven successful, but they are not specific or stable enough to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes [8, 9]. Because this gap has been filled, phytosome technology (a phospholipid encapsulation system that forms molecular complexes with phytochemicals that form a membrane mimicking the lipid bilayer of cell membranes to increase absorption and prolong circulation to protect bioactive compounds from degradation) has been developed [10].

The use of phytochemicals represents a paradigm shift in natural product delivery systems. These nanostructures enhance lipid solubility by binding polar phytoconstituents to phospholipids such as phosphatidylcholine and facilitating their traversal across the cellular membrane and accumulation in tumor tissues [11]. Compared with free materials, phytosome-encapsulated metabolites have been shown to have reduced systemic toxicity, and preclinical results have shown that free compounds achieve an approximately fivefold increase in potency in breast cancer models [11]. Examples of recent developments that incorporate their versatility to address different types of cancer include the use of genistein-loaded phytosomes (Patent WO2022135652A1) and the incorporation of silver nanoparticles in formulations (Patent IN202341042728). Phytosomes not only increase bioavailability but also strengthen conventional chemotherapeutics by 124% in a cisplatin–glycyrrhizic acid nanocomplex, first in a colorectal cancer cell system.

This review critically examines the transformative role of phytosome technology in cancer therapy, focusing on its ability to overcome bioavailability barriers and potentiate the anticancer effects of secondary metabolites. We explore the structural and mechanistic foundations of phytosomes, their preclinical efficacy across major cancer types, and innovations in formulation design. By synthesizing recent advances and challenges—from scalability to regulatory hurdles—this article aims to illuminate the path toward clinical translation, positioning phytosomes as a cornerstone of next-generation, natural product-based oncology.

Phytosome technology overview

The technology of preparing complexes of standardized plant extracts or hydrophilic phytoconstituents with phospholipid molecules, in the most common cases—with phosphatydicholine—represents a modern trend in phytopharmaceuticals [11]. These complexes form lipid-compatible vesicular structures, as illustrated in fig. 1A, that encapsulate and enhance the bioavailability, lipid solubility and gastrointestinal solubility of the active compounds (see fig. 1A). Compared with traditional formulations, there are various advantages with this technology. First, it dramatically increases the bioavailability of phytoconstituents by making them more permissive to pass through lipid-rich biomembranes and into the bloodstream [12]. They increase the solubility of bacterioferritins in aqueous media, thereby protecting them from degradation in digestive fluids and intestinal microbes [13]. Second, such phytosomal complexes also prevent the degradation of phytochemicals to prevent improper drug delivery to target tissues. Third, phytosomes have better drug entrapment efficiency and stability because of the chemical bonds between the bioactive compounds and phospholipid molecules [14]. Furthermore, the drug complexation rates of phytosomes are relatively high, and phytosomes are fabricated in a simple and reproducible manner. Therefore, phytosomes enable the delivery of polar phytochemicals owing to their molecular complex versus bilayer vesicle structure, unlike liposomes [15]. As shown in fig. 1B, phytosomes have key applications and obvious advantages that could increase the therapeutic efficacy of phytochemicals. The unique structure of phytosomes and their benefits make phytosome technology an attractive platform for the development of phytosomepreparations for disease treatment, particularly for cancer, neurodegenerative disease, inflammation, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc. (table 1) [16].

Fig. 1: A) Structure of phytosomes [17]. B) highlights key applications and advantages of phytosomes

Table 1: Comparative analysis of liposome and phytosome technologies in drug delivery: Structural, functional, and bioavailability differences with supporting references

| Aspect | Liposomes | Phytosomes | References |

| Structure | Phospholipid bilayer surrounding an aqueous core | Plant actives (e. g., flavonoids) chemically bonded to phospholipids (no core) | [18] |

| Encapsulation | Hydrophilic (core) and hydrophobic (bilayer) compounds | Covalent bonds between active ingredient and phospholipids | [18] |

| Bioavailability | Improves solubility but variable absorption for some actives | Enhanced absorption due to lipid-compatible structure (e. g., 5-10x curcumin) | [19, 20] |

| Applications | Drugs (Doxil), vaccines (mRNA vaccines), nutraceuticals | Herbal extracts (e. g., curcumin, silymarin) in supplements and cosmetics. | [19] |

| Stability | Prone to oxidation, fusion, and leakage. | More stable due to chemical bonding; resistant to GI degradation. | [19, 20] |

| Manufacturing | Hydration, extrusion, or solvent-based methods. | Reaction of actives with phospholipids (stoichiometric ratio). | [19] |

| Phospholipid content | High phospholipid-to-drug ratio needed. | Lower phospholipid content (1:1 or 1:2 ratio with actives). | [20, 21] |

| Examples | Liposomal vitamin C, Doxorubicin (Doxil). | Meriva® (curcumin), Siliphos® (silybin). | [20] |

Key secondary metabolites in cancer

Secondary metabolites have emerged as critical components of tumor progression, survival and therapeutic resistance traits in cancer metabolism [7]. Small molecules that are produced by cells through metabolic pathways that are not directly involved in growth or survival are called secondary metabolites, and they usually provide cells with the capacity to adapt and signal [22]. These metabolites, including lactate, succinate, fumarate, fatty acids and amino acid derivatives, are modulated in cancer cells, resulting in processes such as tumor cell proliferation, immune evasion, angiogenesis and metastasis. For example, lactate, a byproduct of glycolysis, accumulates in the tumor microenvironment and affects how genes are expressed and how immune cell function, fatty acids, and fatty acid products support cell survival and invasion [23]. By understanding the roles of these metabolites in interactions with oncogenic pathways, novel diagnostic biomarkers and targeted therapies may be discovered that could alter the way cancers are treated [24].

Cancer metabolism has emerged as a critical area of research, with secondary metabolites playing a significant role in tumor progression, survival, and therapeutic resistance. These metabolites are also natural compounds, such as phenolics, alkaloids, and terpenoids or cannabinoids, that contribute to anticancer effects through different mechanisms. For example, phenolics induce apoptosis and inhibit angiogenesis, whereas alkaloids inhibit signaling pathways and induce apoptosis. Terpenoids exhibit anti-inflammatory effects and modulate metabolic pathways, whereas cannabinoids inhibit tumor growth and induce apoptosis (fig. 2). Understanding these mechanisms presents an opportunity to pilot novel diagnostic biomarkers and targeted therapies, ultimately revolutionizing cancer treatment strategies.

Fig. 2: Key secondary metabolites in cancer treatment

Moreover, recent innovations in plant metabolomics have characterized the exhaustive profile of hundreds of secondary metabolites, allowing researchers to identify precise bioactive compounds and clarify their anticancer mechanism through high-resolution mass spectrometry and NMR strategies [25]. Lipid-based transport arrangements, such as phytosomes, significantly improve flavonoid, terpenoid, and alkaloid solubility, durability, and cell consumption, thus increasing their curative index in preclinical cancer models [21]. Currently, paclitaxel and homoharringtonine, both of which were originally derived from plant secondary metabolites, are pillars in the chemotherapy regimen, whereas the use of curcumin and ingenolmebutatein clinical tests for solid tumors and skin tumors, respectively, continues to advance [26]. Mechanistically, these compounds suppress tumor growth by targeting important oncogenic pathways, including the PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MAPK/ERK, and NFB signaling pathways, thereby promoting apoptosis, the cell cycle, and barricade angiogenesis [27]. Furthermore, certain alkaloids, such as tetrandrine, have demonstrated multidrug resistance reversal properties by modulating efflux transporters and apoptotic regulators, underscoring their potential as adjuvants in combination therapies [28]. As the bioactive phytochemicals of grapevines grow, an integrated approach combining metabolomic screening, target bioassays, and nanocarrier formulation is proposed to accelerate the discovery and optimization of next-generation anticancer agents from secondary metabolites in plants [29].

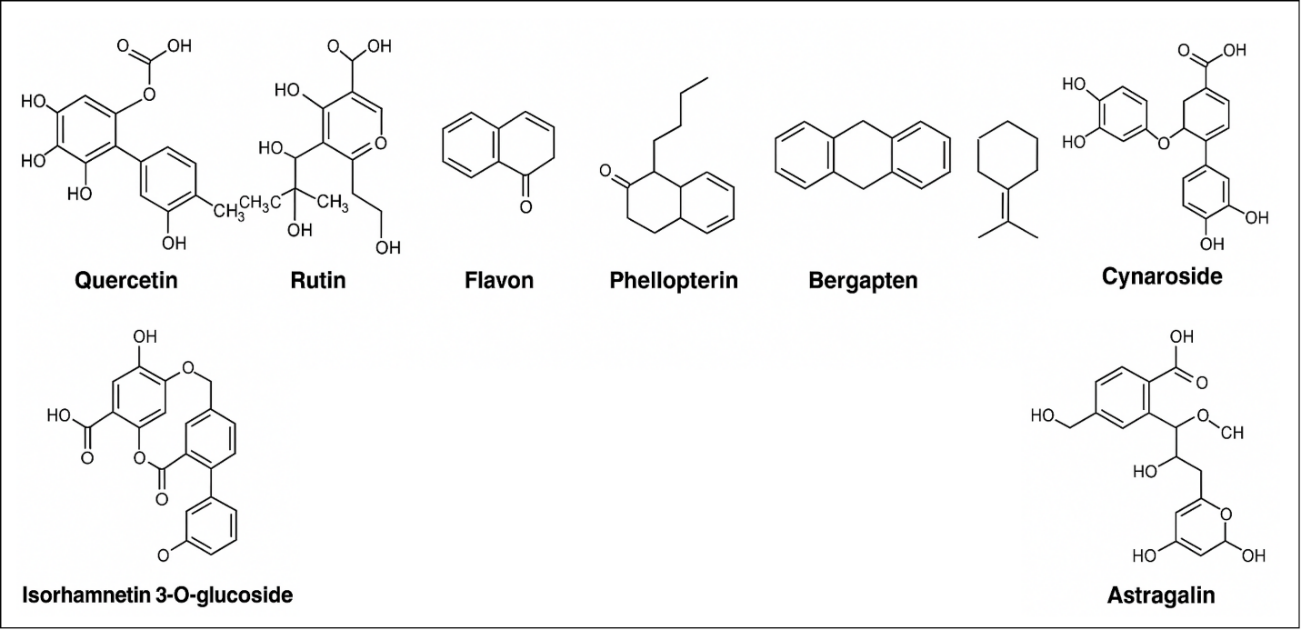

Owing to their multifaceted pharmacological effects, plant secondary metabolites from multiple botanicals have strong anticancer effects [30]. These compounds fall into four main classes, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics, each of which has a distinct mechanism of tumor control, ranging from oxidative stress transition to signal transduction [31]. The flavonoids quercetin, kaempferol, and rutin have been shown to inhibit apoptosis, block cell proliferation, and reduce metastatic dissemination by reducing PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling [21]. A complete picture of their molecular structures, including those of cynaroside, astragalin, isorhamnetin 30-glucoside, quercetin, rutin, flavonol, phellopterin, bergapten, and isoquinoline, is shown in fig. 3 [32].

Fig. 3: Phytosome-based approaches to cancer treatment: chemical structures of phytoconstituents

The encapsulation of flavonoids in a phytosome carrier effectively increased the aqueous solubility, chemical toughness, and gastrointestinal absorption, which are important for improved systemic exposure [21]. Parallel studies revealed that terpenoids—such as curcumin, betulinic acid, and ginsenoside Rg3—exert comprehensive antiproliferative and antiangiogenic actions across multiple cancer models [33]. The phytosome formulation further enhances the curative index of these terpenoids by improving their pharmacokinetic profile and tumor-specific transport [34].

Recent progress in plant metabolomics has led to high-resolution profiling of hundreds of secondary metabolites, accelerating the identification of new anticancer agents via mass spectrometry and NMR-based dereplication [35]. The evolution of this signature indicates that alkaloid subclasses, such as berberine, matrine, and vinca alkaloids, which are powerful modulators of MDR and apoptotic regulators, offer new opportunities for combination therapy [28]. Furthermore, integrative nanocarrier platforms that codeliver phytochemical blends alongside immunomodulators are under investigation for synergistic enhancement of tumor eradication and reduction in systemic side effects [36]. As formulation technologies evolve, the fusion of metabolomic insights with targeted delivery systems promises to usher in a new era of plant‑based precision oncology.

The plant alkaloids berberine, dauricine, and vinblastine exhibit potent anticancer activities through trip program cell passage, cell cycle arrest, and the barricade autophagic persistence nerve pathway [37–39]. Phytosome-based delivery of these alkaloids significantly enhances their pharmacokinetic profile, resulting in significantly increased systemic bioavailability and curative exposure [21]. Similarly, phenolic phytochemicals, including resveratrol and itsdimethylated derivative pterostilbene, effectively suppress malignant cell proliferation and stimulate intrinsic apoptosis [40, 41]. The incorporation of these phenolic resins into phytosomal nanocarriers further enhances their solubility and cell consumption, thus enhancing the target tumor and minimizing undesirable side effects [42]. Recent preclinical and in vivo investigations have confirmed that phytosome‑encapsulated secondary metabolites exhibit superior antitumor efficacy across diverse cancer models, underscoring their translational promise [43, 44].

Table 2: Cytotoxic activities of various compounds against cancer cell lines

| Compound/Class | Source/Type | Cancer cell line(s) | IC₅₀ value(s) | Notes | Ref |

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | Flavonoid (Salsola oppositifolia) | MCF-7 (breast) | 18.2 μg/ml | Potent activity against hormone-dependent breast cancer cells. | [45] |

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside | Flavonoid (Salsola oppositifolia) | MCF-7 (breast), LNCaP (prostate) | 25.2 μg/ml (MCF-7), 20.5 μg/ml (LNCaP) | Effective against both breast and prostate cancer cell lines. | [46] |

| Methanol extract | Flavonoid-rich extract (Cassia angustifolia) | MCF-7 (breast) | 4.0 μg/μl | Demonstrated strong cytotoxicity. | [47] |

| Ethanol extract | Flavonoid-rich extract (Cassia angustifolia) | HeLa (cervical), MCF-7 (breast) | 8.18 μg/μl (HeLa), 8.79 μg/μl (MCF-7) | Moderate cytotoxic effects. | [48] |

| Compound 3 | Alkaloid-like compound | Multiple (e. g., SK-MEL-28, MOLT-4) | 1.8–7.8 μM | Broad-spectrum activity across various cancer cell lines. | [49] |

| Lipojesaconitine | Diterpenoid alkaloid | MCF-7 (breast), A549 (lung) | 6.7 μM (MCF-7), 7.3 μM (A549) | Notable cytotoxicity in breast and lung cancer cells. | [50] |

| Compound 3 (Buxus microphylla) | Triterpenoid alkaloid | MCF-7 (breast), A549 (lung) | 4.51 μM (MCF-7), 11.76 μM (A549) | Selective cytotoxicity observed. | [51] |

Exploring the anticancer potential of plant‑derived secondary metabolites across diverse tumor cell lines highlights their pivotal role in modern oncology drug discovery [26]. In in vitro IC₅₀assessment, flavonoids exhibit strong cytotoxicity against breast, lung, and hepatic carcinoma cells by disrupting the critical proliferation nerve pathway and causing cell cycle arrest [52]. Moreover, alkaloids exhibit potent apoptotic initiation and proliferation inhibition in a melanoma model via caspase‑dependent cascades [53]. These phytochemicals, as flexible scaffolds for targeted therapy, effectively suppress metastasis and angiogenesis while maintaining selectivity for malignant cells [27, 28]. These findings are supported by the IC₅₀ values presented in table 2, which highlight the strong effectiveness of these secondary metabolites across a range of cancer types. The variation in IC₅₀ values among different cell lines also suggests that secondary metabolites can be tailored to selectively target specific forms of cancer, thereby increasing the precision of oncological treatments [54].

Progress in dispensing arrangements, such as phytosomes, has significantly improved the bioavailability and curative value of secondary metabolites, facilitating excessive simplified consumption and prolonging their release within the tumor microenvironment [21]. Structure-guided optimization of flavonoid-derived functions has led to the evolution of analogs with improved pharmacokinetic profiles and target receptor affinities that propel the use of natural-product chemotherapeutics in the clinic [55]. Moreover, to increase the identification and rational design of fresh plant-derived anticancer agents, high-throughput screening channels should be integrated with computational docking methods, traditional phytochemistry methods and novel drug discovery methods [56–58].

Flavonoids, a multifaceted group of plant-derived secondary metabolites, exhibit a wide spectrum of curative properties that significantly contribute to human viability. The powerful antioxidant activity of these compounds neutralizes free radicals, thus protecting cell components from oxidative damage. This antioxidative capacity is complemented by its anti-inflammatory properties, which contribute to reducing the risk of vascular disorders by modulating the inflammatory nerve pathway [59]. Flavonoids in oncology have been shown to inhibit cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis, making them very useful agents for cancer prevention and therapy [60]. Moreover, their neuroprotective and cardioprotective effects are well documented, together with surveys that demonstrate their obligation to maintain nervous and cardiac tissues in opposition to different stress and injury conditions. Moreover, the antibacterial properties of flavonoids make them more powerful in fighting bacterial diseases, with a wide range of uses in medicine [61]. The categorization of secondary metabolites into classes such as alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, and polyphenols is essential for understanding their specific curative potential in cancer therapy. This classification is represented in fig. 4, which shows the essential compounds in every group. In particular, the alkaloids vinblastine [62], vincristine [63], and camptothecin [64] have been detected for their potent anticancer activities. Vinblastine and vincristine act by disrupting the formation of microtubules, thus separating cells in metaphase from those undergoing apoptosis. Camptothecin, however, inhibits DNA topoisomerase I, resulting in DNA damage and subsequent cell death. These compounds exemplify the potential of plant-derived alkaloids in the development of effective anticancer therapies [65].

Flavonoids, such as apigenin, genistein, and kaempferol, are organic compounds found in various fruits and vegetables. These bioactive molecules have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that contribute to their ability to inhibit cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis. The mechanism involves modulating essential cellular nerve pathways, including the PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling cascades, leading to cell cycle progression and programmed death in cancer cells [66].

Fig. 4: Overview of secondary metabolites and their classifications, including key compounds with anticancer properties

In cancer prevention, terpenoids such as lycopene and gamma-tocopherol play important roles. Lycopene, which is derived mainly from tomato, accumulates in prostate tissues and has been shown to suppress tumor evolution by suppressing angiogenesis and apoptosis in prostate and breast cancer cells. The gamma-tocopherol structure of vitamin E contributes to cancer prevention through its antioxidant effects, which reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, which are crucial for the progression of cancer [67].

Polyphenols such as curcumin, resveratrol, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) have promising anticancer activities [68]. Curcumin, derived from turmeric, regulates a variety of molecular targets, including transcriptional and expansion factors, notably in the fight against tumor growth and metastasis. Resveratrol, which is produced from grapes and red wine, has anticancer effects through apoptosis and the inhibition of angiogenesis. EGG, a key catechin of green tea, inhibits tumor cell proliferation and apoptosis via the signal nerve pathway [69].

The bioavailability of these phytochemicals is typically restricted by their reduced solubility and firmness. To overcome this obstacle, sophisticated distribution frameworks for phytosomes have been developed. Phytosomes are complexes of phospholipids and phytoconstituents that increase the solubility, absorption, and curative efficiency of bioactive compounds [70]. Compared with its pure form, the phytosomal form of apigenin has demonstrated improved bioavailability and hepatoprotective properties [71].

In addition to phytosomes, nanoformulations such as liposomes, micelles, and nanoparticles have been developed to improve the delivery and efficiency of phytochemicals. These nanoparticles protect the active compound from degeneration, increase its stability, and facilitate target delivery to the tumor site, thus increasing its curative capacity [68]. EGCG-loaded nanoparticles in a prostate cancer model improved cell consumption and anticancer activity [69].

The secondary metabolites of medicinal plants, including alkaloids, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds, show significant anticancer activities. Vincristine and vinblastine interfere with the formation of mitotic spindles, which is essential for the detection and inhibition of metaphase progression. Flavonoids such as quercetin and curcumin facilitate apoptosis in a number of cancer cells, including prostate, breast, and melanoma cells, by modulating the central nervous system. Phenolic intensifiers, which are abundant in medicinal plants, have anticancer effects through their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities and support tumor suppression [72].

Aquatic algae are becoming increasingly important as valuable bioactive compounds with powerful anticancer uses, especially in treating lung cancer. For example, fucoidan, a sulfated polysaccharide derived from brown algae that prefers Sargassum fusiforme, has been demonstrated to induce apoptosis in lung cancer cells by modulating the mitochondrial nerve pathway and caspase activation [73]. Furthermore, compounds such as dieckol and phlorofucofuroeckol A from brown algae exhibit significant anticancer activities by suppressing cell migration and invasion as well as by inducing apoptosis in lung cancer cells [74]. These conclusions suggest a synergistic effect between marine bioactives and standard chemotherapeutic agents, promoting treatment efficacy and reducing side effects.

In addition, marine microalgae prefer Dunaliella tertiolecta, which produces carotenoids identical to violaxanthin and has antiproliferative effects on breast cancer cell lines [75]. The various chemical compositions of marine algal compounds enable them to target several nerve pathways involved in tumor progression, including angiogenesis, apoptosis, and immune transition [76]. This multidisciplinary method not only enhances anticancer efficacy but also contributes to the fight against drug resistance, highlighting the importance of incorporating marine extracts into cancer therapy methods.

Mechanism of action: phytosome-based enhancement of bioavailability

Phytosomes, which significantly increase the bioavailability of plant bioactive compounds, have transformed the landscape of drug delivery structures. The present high-tech dispatch machines use phospholipid complexes that closely reproduce the architecture of the natural membrane, particularly the lipid bilayer [77]. The aforementioned complex facilitates efficient interactions with the cell membrane, primarily aimed at improving the absorption of phytochemicals in the Gl tract [78]. Phytosomes, as shown in fig. 5, are able to enter the cell membrane and facilitate the efficient transport of active compounds. They mimic the human body's cellular lipid structure and provide a protective shield against phytochemicals and harsh gastrointestinal conditions to ensure targeted transport to specific tissues [79]. In addition, phytosomes support the continuation of the durability and curative potential of the bioactive component throughout the delivery process by mimicking cell membrane activity [80]. This architectural change, which aims at improving the location and allocation of active molecules in sought-after areas, ultimately enhances curative efficacy [81].

The possibility of the use of phytosome-based formulations in the treatment of a wide range of chronic diseases has also been highlighted in recent surveys. Flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids encapsulated in phytosomeshave shown promising results because of their current poor water solubility and minimal permeability, two major limitations of conventional herbal therapy. Increased bioavailability is related to increased pharmacokinetic efficiency and better clinical outcomes [82]. Moreover, phytosomes extend the targeted transition of the molecular nerve pathway involved in inflammation, oxidative stress, and cancer progression, including the PI3K/Akt and NF-B signaling cascades [83]. Furthermore, these frameworks present decreased systemic toxicity corresponding to their ability to guide curative agents, particularly in the treatment of the site, to minimize off-target effects [84]. As exploration progresses, phytosome tools are becoming increasingly modern platforms for personalized and correct medicine, especially in the formulation of next-generation herbal medicines.

The modified phytochemical encapsulation of phytosomes results in increased resistance to Gl enzymes, decreased degeneration, and improved retention of active compounds in the small intestine [34]. This increase in firmness directly contributes to increased systemic robustness, ensuring prolonged circulation and bioactivity of the curative agent [85]. Phytosome formulations extend the half-life and function of phytochemicals below physiological conditions by protecting bioactive molecules from enzymatic dislocation and microbial metamorphosis [86]. Such systematic encapsulation contributes significantly to maintaining drug authority during gastrointestinal tract infection and maintains longer curative effects [87]. Compared with standard herbal infusions, phytosome innovations significantly increase the number of phytochemicals absorbed in systemic circulation and thus increase pharmacologic efficiency [88]. The increased bioavailability provided by phytosomes has been demonstrated to increase clinical effects, as increased plasma concentrations of active ingredients translate into increased therapeutic response [89]. As a recent development in nanocarrier design, phytosome technology integrates protective lipid complexation with optimized delivery, which contributes to better drug distribution in the body. The present flexible delivery platform is an essential addition to the pharmacokinetic performance of a number of phytochemicals, confirming the promise of transforming botanical medicines [90].

Fig. 5: Mechanism of the involvement of phytosome-encapsulated secondary metabolites in enhancing cancer. © Copyright 2025 • Dove Medical Press Ltd. [21]

Furthermore, phytosome encapsulation has been shown to increase the anticancer activity of secondary metabolites via a number of mechanisms, together with increased solubility and membrane permeability, which contributes to increased plasma bioactive concentrations [21]. Furthermore, the phospholipid-based carrier facilitates deep penetration into cancer cells, resulting in increased intracellular incorporation of the curative agent. This improved uptake enables a highly potent transition of a significant oncogenic nerve pathway, including NF-B and P|3K/AKT, which are fundamental to tumor cell resilience and proliferation [21]. By overcoming traditional bioavailability barriers, phytosome systems effectively target and inhibit these signaling cascades, leading to enhanced apoptotic induction and reduced cancer cell growth [91].

Anticance efficacy of phytosome-encapsulated metabolites

Inhibition of cancer pathways

Phytosome-encapsulated metabolites exhibit outstanding efficacy in suppressing key cancer nerve pathways and represent a significant increase over their unencapsulated counterparts. Research suggests that these formulations target essential oncogenic signaling cascades, including the NF-B and PI3K/AKT nerve pathways, which are essential for cancer cell proliferation, strength, and metastasis [21, 92]. The increased bioavailability obtained by phytosome encapsulation enables such bioactive compounds to reach high intracellular concentrations, allowing them to interact smoothly with their molecular targets in the confines of cancer cells [93]. Phytosome-encapsulated flavonoids and terpenoids have a more potent inhibitory effect on this nerve pathway, notably with a striking downregulation of the prosurvival protein and activation of the apoptotic mechanism in various cancer cells [94].

The molecular mechanism underlying the improved anticancer effects of phytosome formulations extends beyond better bioavailability to include enhanced cellular consumption and interaction with specific molecular targets[95]. The phospholipid component of phytosomes makes it easier to penetrate the cell membrane so that the encased material can be more concentrated inside the cell [96]. Moreover, phytosome encapsulation ensures that these bioactive molecules reach cancer cells in their integral, active form and continue their ability to modulate the oncogenic nerve pathway effectively [97]. Recent research has shown that phytosome-encapsulated secondary metabolites can simultaneously target several cancer-related nerve pathways, offering a multitarget technique that may help to elucidate the compensatory mechanism commonly detected in cancer cells, leading to treatment resistance [98].

Enhanced antiproliferative effects

The antiproliferative capacity of secondary metabolites is significantly enhanced when they are delivered via phytosome technology, as evidenced by numerous preclinical studies across various cancer models. A particularly striking demonstration method was derived from the analysis of Moringa oleifera leaf polyphenols encased in phytosomes (MoPs), which showed remarkable antiproliferative effects on the 4T1 breast cancer cell line. The study reported that MoP exhibited an inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 7.73±2.87 μg/ml, representing a dramatic improvement over nonencapsulated polyphenols (212.9±1.30 μg/ml) and even outperforming the conventional chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin (68.35±3.508 μg/ml) in the same model. This significant increase in potency, approximately 28-fold greater than that of the unencapsulated form, underlines the revolutionary potential of phytosome innovation to increase the anticancer properties of the plant compound [99].

To combine different factors beyond simple bioavailability, it may be impossible to detect superior antiproliferative effects detected by phytosome-encapsulated metabolites [100]. Phytosome formulations have the ability to overcome several drug resistance mechanisms, which regularly limits the effectiveness of conventional anticancer agents [101]. The use of a single nerve pathway by phytosomes may bypass the outflow transporter admire P glycoprotein, allowing the encapsulated compound to spread inside immune cancer cells at curative concentrations [102]. Furthermore, phytosome encapsulation seems to improve the selectivity of these compounds for cancer cells above normal cells, as indicated by the enhanced selectivity index reported in several studies. The current improved selectivity contributes to a broader curative window, allowing for additional productive cancer cell targets during the minimization of side effects in healthy tissues, a crucial consideration for translating the above promising preclinical results into clinical applications [103].

Reduced side effects

A significant advantage of phytosome-encapsulated metabolites in cancer treatment is their improved safety profile and reduced adverse effects compared with both conventional formulations of the same compounds and standard chemotherapeutic agents [104]. The increased bioavailability obtained by encapsulating phytosomes enables a powerful curative effect at a low dose, thus reducing the exposure to possibly harmful metabolites and minimizing dose-dependent side effects [34]. This rule has been skillfully demonstrated in a study on CAT-encapsulated SMEDDS, a self-microemulsifying drug transport organization, where the encapsulation of PF403 (a CAT3 metabolite) in the GI tract and plasma significantly reduced the coevals of PF403 (a CAT metabolite) in the Gl tract and plasma, significantly reducing gastrointestinal side effects as well as strong antiglioma effects [105]. This metamorphosis modification tactic demonstrates that the selective encapsulation of bioactive compounds can modify their pharmacokinetic profiles to increase their curative index [106].

Safety surveys on phytosome formulations have several motivating effects via several models. For example, acute toxicity assessment of Moringa oleifera polyphenol-loaded phytosomes in Swiss albino mice revealed that these phytosomes are safe at doses less than 2000 mg/kg, suggesting a wide safety margin for clinical development [103]. The decreased toxicity of phytosome formulations may be attributed to a number of variables, including a more specific tissue target restricting the exposure of nontarget organs, safety against the formation of reactive, alternatively poisonous metabolites, and improved stability, which prevents the development of undesirable byproducts [107]. In cancer therapy, treatment-limiting toxicities regularly prevent patients from receiving an optimum curative dose or, alternatively, from completing complete treatment programs. The phytosome-encapsulated metabolite has the potential to improve simultaneously life satisfaction and treatment effects in patients with cancer by allowing a more tolerable and renewable treatment regime [108].

Synthesis of phytosome containing secondary metabolites

The phytosome formulation includes the incorporation of the bioactive plant component into a phospholipid-rich lipid matrix, which significantly enhances phytochemical bioavailability and molecular durability [19, 109]. The common manufacturing method consists of solvent vaporization, thin film hydration, and antisolvent precipitation methods, each of which is adapted to facilitate uniform and complex formation [110]. These procedures initiate the interaction between the hydrophilic molecule of the phytochemical and lipophilic composition of the phospholipid, forming a vesicular phytosome that is able to translocate the productive membrane [111]. The physicochemical characteristics of the target secondary metabolite, ensuring effective incorporation into the lipid architecture, determine the choice of the appropriate encapsulation system. To optimize phytosome efficacy, critical parameters such as the phospholipid‑to‑metabolite molar ratio, processing temperature, and mixing conditions are adjusted to maximize encapsulation efficiency and maintain bioactive potency [34]. The overall picture of the resulting phytosome nanoparticles, via vibrant light dispersal (DLS) for atom size distribution and zeta ability evaluation alongside scanning electron microscopy (SEM), confirms their firmness and suitability for curative applications [112, 113].

Phytosome technology has led to marked improvements in phytochemical bioavailability and therapeutic potency but faces inherent challenges in terms of physicochemical stability, industrial scalability, and manufacturing reproducibility [31, 114]. Ensuring long‑term stability requires optimized storage—ideally at 25 °C—and the incorporation of excipients such as surfactants, natural antioxidants, and cryoprotectants to inhibit lipid oxidation, prevent nanoparticle aggregation, and maintain vesicle integrity [115]. Transitioning from laboratories to large-scale development requires the acceptance of incessant management schemes, such as flow reactors and microfluidic media, which continue encapsulation productivity and nanoarchitecture under high-throughput conditions [85]. Capturing Calibers via Design Standard Ship Method Analytical technology enables real-time monitoring of important caliber attributes—particle size circulation, zeta power, and entrapment efficiency—to ensure consistency and performance throughout scale-up. Ultimately, compliance with relevant standards, including top-quality manufacturing practices, ICH Q8-Q10 guidelines, and country-specific phytopharmaceutical legal acts enforced by authorities such as the US FDA and CDSCO, is essential for procuring safety, batch-to-batch homogeneity, and trade mandates [87].

Future perspectives and directions

The progress of phytosome-encapsulated metabolites in cancer therapy is poised to extend inside the clarity of oncology, together with the evolution of tendencies focused on custom formulations adapted to the human inherited profile, metabolism, or tumor microenvironments. Progress on multiomics techniques (e. g., metabolomics and proteomics) will enable the identification of fresh secondary metabolites and the optimization of phytosomal composition for synergies with the oncogenic nerve pathway. Scholars are examining hybrid dispatch structures that integrate phytosomes with stimuli-responsive nanoparticles, otherwise immune checkpoint inhibitors, to increase tumorigenic accretion and overcome drug resistance.

Scalable manufacturing approaches, such as microfluidic synthesis and 3D-printed dose configurations, are already being developed to address new challenges in batch-to-batch variability and industrial manufacturing. Moreover, the design of phospholipid‒metabolite complexes with optimized firmness and release dynamics is accelerated by the use of a machine learning-driven molecular mold, which reduces the reliance on the experimental trial-and-error method. For the validation of the extended safety and standardized dose regimens for synthetic therapy in combination with traditional chemotherapeutics, future clinical trials are needed.

Further promising preclinical data on neuroprotection, cardiometabolic disturbances, and antiaging interventions should be added to the scope of phytosome use beyond oncology. Theranostic phytosome developments, including imaging agents for real-time monitoring of therapy, represent a breakthrough in personalized medicine. As control standards for sophisticated phytopharmaceuticals, cooperation between nanotechnologists, pharmacists, and botanists will be essential to translate the above developments into clinically feasible treatments.

CONCLUSION

Phytosome technology has emerged as a revolutionary platform for the delivery of plant-derived secondary metabolites for cancer therapy, effectively overcoming the longstanding obstacles of insoluble solubility, rapid metamorphosis, and limited bioavailability, which hinders their clinical translation. These phytosomes not only improve the absorption and systemic exposure of important anticancer compounds, such as flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics, but also protect them from gastrointestinal and metabolic decline, thus maximizing their curative potential. Preclinical research has consistently shown that compared with their free counterparts, phytosome-encapsulated phytochemicals have superior antitumor activity, reduced systemic toxicity, and better pharmacokinetic profiles. Moreover, the integration of the phytosome machinery with advances in plant metabolomics and nanocarrier frameworks will accelerate the design and optimization of bioactive compounds, paving the way for a precision oncology approach utilizing a multidisciplinary secondary metabolite mechanism. Owing to difficulties related to scalability, supervisory approval, and delays in clinical validation, this review highlights phytosomes as a cornerstone of next-generation, innate product-based cancer therapy, contributing to a promising path toward safer, more powerful, and targeted cancer therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Mahin Khan, Zoya Sheikh, Arfana Sheikh, and Vaishnavi Shete contributed to the literature review, drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Mujibullah Sheikh served as the corresponding author, coordinated the writing process, and finalized the manuscript for submission.

All authors reviewed and approved the final version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING

Funding: Open access funding was provided by the Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research. No funding is involved while preparing the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

NF-κB (Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells), PI3K/AKT (Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Protein Kinase B), GI (Gastrointestinal), NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance), MDR (Multidrug Resistance), MAPK/ERK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase/Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase).

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed equally

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229-63. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834, PMID 38572751.

Kumar S, Shukla MK, Sharma AK, Jayaprakash GK, Tonk RK, Chellappan DK. Metal-based nanomaterials and nanocomposites as promising frontier in cancer chemotherapy. Med. 2023;4(2):e253. doi: 10.1002/mco2.253, PMID 37025253.

He Y, Chen H, Li W, Xu L, Yao H, Cao Y. 3-bromopyruvate loaded bismuth sulfide nanospheres improve cancer treatment by synergizing radiotherapy with modulation of tumor metabolism. J Nanobiotechnology. 2023 Jul 5;21(1):209. doi: 10.1186/s12951-023-01970-8, PMID 37408010.

Shukla S, Mehta A. Anticancer potential of medicinal plants and their phytochemicals: a review. Braz J Bot. 2015 Jun 1;38(2):199-210. doi: 10.1007/s40415-015-0135-0.

Zheng C, Li M, Ding J. Challenges and opportunities of nanomedicines in clinical translation. BIO Integr. 2021 Jul 1;2(2):57. doi: 10.15212/bioi-2021-0016.

Kesharwani SS, Mallya P, Kumar VA, Jain V, Sharma S, Dey S. Nobiletin as a molecule for formulation development: an overview of advanced formulation and nanotechnology-based strategies of nobiletin. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020 Aug 5;21(6):226. doi: 10.1208/s12249-020-01767-0, PMID 32761293.

Khan A, Siddiqui S, Husain SA, Mazurek S, Iqbal MA. Phytocompounds targeting metabolic reprogramming in cancer: an assessment of role mechanisms, pathways and therapeutic relevance. J Agric Food Chem. 2021 Jun 30;69(25):6897-928. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c01173, PMID 34133161.

Maviah MB, Farooq MA, Mavlyanova R, Veroniaina H, Filli MS, Aquib M. Food protein-based nanodelivery systems for hydrophobic and poorly soluble compounds. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020 Mar 9;21(3):101. doi: 10.1208/s12249-020-01641-z, PMID 32152890.

Wang G, Wang J, Wu W, Tony To SS, Zhao H, Wang J. Advances in lipid-based drug delivery: enhancing efficiency for hydrophobic drugs. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015 Sep 2;12(9):1475-99. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1021681, PMID 25843160.

Pal P, Dave V, Paliwal S, Sharma M, Potdar MB, Tyagi A. Phytosomes nanoarchitectures promising clinical applications and therapeutics. In: Dave V, Gupta N, Sur S, editors. Nanopharmaceutical advanced delivery systems. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2021. p. 187-216. doi: 10.1002/9781119711698.ch9.

Kapse MV, Mulla JA. Unlocking the potential of phytosomes: a review of formulation techniques, evaluation methods and emerging applications. Acta Mater Med. 2024 Dec 28;3(4):509-20. doi: 10.15212/AMM-2024-0055.

Agarwal A, Chakraborty P, Chakraborty DD, Saharan VA. Phytosomes: complexation utilisation and commerical status. J Biol Act Prod Nat. 2012 Jan 1;2(2):65-77. doi: 10.1080/22311866.2012.10719111.

Li H, Xia X, Tan X, Zang J, Wang Z, Ei Seedi HR. Advancements of nature nanocage protein: preparation, identification and multiple applications of ferritins. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022 Sep 1;62(25):7117-28. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1911925, PMID 33860692.

Lu M, Qiu Q, Luo X, Liu X, Sun J, Wang C. Phyto-phospholipid complexes (phytosomes): a novel strategy to improve the bioavailability of active constituents. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2019 May 1;14(3):265-74. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2018.05.011, PMID 32104457.

Kamireddy S, Sangeetha SS, Roy H. Quercetin phytosomes: a comprehensive approach for the preparation and optimization using box-behnken design. Int J Appl Pharm. 2025 May 8;17(4):344-57. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2025v17i4.54075.

Alharbi WS, Almughem FA, Almehmady AM, Jarallah SJ, Alsharif WK, Alzahrani NM. Phytosomes as an emerging nanotechnology platform for the topical delivery of bioactive phytochemicals. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Sep;13(9):1475. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13091475, PMID 34575551.

Kumar A, Kumar B, Singh SK, Kaur B, Singh S. A review on phytosomes: novel approach for herbal phytochemicals. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017 Oct 1;10(10):41-7. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i10.20424.

Singh M, Devi S, Rana VS, Mishra BB, Kumar J, Ahluwalia V. Delivery of phytochemicals by liposome cargos: recent progress challenges and opportunities. J Microencapsul. 2019 Apr 3;36(3):215-35. doi: 10.1080/02652048.2019.1617361, PMID 31092084.

Lu M, Qiu Q, Luo X, Liu X, Sun J, Wang C. Phyto-phospholipid complexes (phytosomes): a novel strategy to improve the bioavailability of active constituents. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2019 May;14(3):265-74. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2018.05.011, PMID 32104457.

Karimi N, Ghanbarzadeh B, Hamishehkar H, Keivani F, Pezeshki A, Gholian MM. Phytosome and liposome: the beneficial encapsulation systems in drug delivery and food application. Appl Food Biotechnol. 2015 Jun 30;2(3):17-27. doi: 10.22037/afb.v2i3.8832.

Mardiana L, Milanda T, Hadisaputri YE, Chaerunisaa AY. Phytosome enhanced secondary metabolites for improved anticancer efficacy: mechanisms and bioavailability review. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2025 Jan 11;19:201-18. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S483404, PMID 39816849.

Turgeon BG, Bushley KE. Secondary metabolism. In: Borkovich KA, Ebbole DJ, editors. Cellular and molecular biology of filamentous fungi. Washington, DC, USA: ASM Press; 2010. p. 376-95. doi: 10.1128/9781555816636.ch26.

Baryla M, Semeniuk Wojtas A, Rog L, Kraj L, Malyszko M, Stec R. Oncometabolites a link between cancer cells and tumor microenvironment. Biology. 2022 Feb;11(2):270. doi: 10.3390/biology11020270, PMID 35205136.

Qiu S, Cai Y, Yao H, Lin C, Xie Y, Tang S. Small molecule metabolites: discovery of biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Mar 20;8(1):132. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01399-3, PMID 36941259.

Dabbousy R, Rima M, Roufayel R, Rahal M, Legros C, Sabatier JM. Plant metabolomics: the future of anticancer drug discovery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024 Oct;17(10):1307. doi: 10.3390/ph17101307, PMID 39458949.

Seca AM, Pinto DC. Plant secondary metabolites as anticancer agents: successes in clinical trials and therapeutic application. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Jan 16;19(1):263. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010263, PMID 29337925.

AP, Paul S. Plant secondary metabolites in cancer treatment: a mini review. OAJMB. 2024 Apr 2;9(2):1-4. doi: 10.23880/oajmb-16000291.

Jamal A, Arif A, Shahid MN, Kiran S, Batool Z. Plant secondary metabolites inhibit cancer by targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR): an updated review on their regulation and mechanisms of action. Asian Pac J Cancer Biol. 2025 Jan 12;10(1):191-206. doi: 10.31557/apjcb.2025.10.1.191-206.

Situmorang PC, Ilyas S, Nugraha SE, Syahputra RA, Nik Abd Rahman NM. Prospects of compounds of herbal plants as anticancer agents: a comprehensive review from molecular pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2024 Jul 22;15:1387866. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1387866, PMID 39104398.

Roy A, Khan A, Ahmad I, Alghamdi S, Rajab BS, Babalghith AO. Flavonoids a bioactive compound from medicinal plants and its therapeutic applications. Bio Med Res Int. 2022 Jun 6;2022:5445291. doi: 10.1155/2022/5445291, PMID 35707379.

Koppula S, Shaik B, Maddi S. Phytosomes as a new frontier and emerging nanotechnology platform for phytopharmaceuticals: therapeutic and clinical applications. Phytother Res. 2025;39(5):2217-49. doi: 10.1002/ptr.8465, PMID 40110760.

Pandey P, Lakhanpal S, Mahmood D, Kang HN, Kim B, Kang S. An updated review summarizing the anticancer potential of flavonoids via targeting NF-kB pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1513422. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1513422, PMID 39834817.

Hilal B, Khan MM, Fariduddin Q. Recent advancements in deciphering the therapeutic properties of plant secondary metabolites: phenolics terpenes and alkaloids. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024 Jun 1;211:108674. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.108674, PMID 38705044.

Toma L, Deleanu M, Sanda GM, Barbalata T, Niculescu LS, Sima AV. Bioactive compounds formulated in phytosomes administered as complementary therapy for metabolic disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jan;25(8):4162. doi: 10.3390/ijms25084162, PMID 38673748.

Dabbousy R, Rima M, Roufayel R, Rahal M, Legros C, Sabatier JM. Plant metabolomics: the future of anticancer drug discovery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024 Oct;17(10):1307. doi: 10.3390/ph17101307, PMID 39458949.

Kawish SM, Sharma S, Gupta P, Ahmad FJ, Iqbal M, Alshabrmi FM. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery platform for simultaneous administration of phytochemicals and chemotherapeutics: emerging trends in cancer management. Part & Part Syst Charact. 2024;41(12):2400049. doi: 10.1002/ppsc.202400049.

Li Q, Zhao H, Chen W, Huang P. Berberine induces apoptosis and arrests the cell cycle in multiple cancer cell lines. Arch Med Sci. 2023 Sep 1;19(5):1530-7. doi: 10.5114/aoms/132969, PMID 37732040.

Wu MY, Wang SF, Cai CZ, Tan JQ, Li M, Lu JJ. Natural autophagy blockers dauricine (DAC) and daurisoline (DAS) sensitize cancer cells to camptothecin-induced toxicity. Oncotarget. 2017 Sep 8;8(44):77673-84. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20767, PMID 29100416.

Salerni BL, Bates DJ, Albershardt TC, Lowrey CH, Eastman A. Vinblastine induces acute cell cycle phase-independent apoptosis in some leukemias and lymphomas and can induce acute apoptosis in others when Mcl-1 is suppressed. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010 Apr;9(4):791-802. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0028, PMID 20371726.

Tsai HY, Ho CT, Chen YK. Biological actions and molecular effects of resveratrol pterostilbene and 3-hydroxypterostilbene. J Food Drug Anal. 2017 Jan 1;25(1):134-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.07.004, PMID 28911531.

Liu Y, You Y, Lu J, Chen X, Yang Z. Recent advances in synthesis bioactivity and pharmacokinetics of pterostilbene an important analog of resveratrol. Molecules. 2020 Nov 6;25(21):5166. doi: 10.3390/molecules25215166, PMID 33171952.

Singh A, Srivastav S, Singh MP, Singh R, Kumar P, Kush P. Recent advances in phytosomes for the safe management of cancer. Phytomed Plus. 2024 May 1;4(2):100540. doi: 10.1016/j.phyplu.2024.100540.

Kadriya A, Falah M. Nanoscale phytosomes as an emerging modality for cancer therapy. Cells. 2023;12(15):1999. doi: 10.3390/cells12151999, PMID 37566078.

Gaikwad SS, Morade YY, Kothule AM, Kshirsagar SJ, Laddha UD, Salunkhe KS. Overview of phytosomes in treating cancer: advancement challenges and future outlook. Heliyon. 2023 Jun 1;9(6):e16561. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16561, PMID 37260890.

Basim S, Kasim AA. Cytotoxic activity of the ethyl acetate extract of Iraqi Carica papaya leaves in breast and lung cancer cell lines. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2023 Feb 1;24(2):581-6. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2023.24.2.581, PMID 36853308.

Li J, Shen S, Liu Z, Zhao H, Liu S, Liu Q. Synthesis and structure-activity analysis of icaritin derivatives as potential tumor growth inhibitors of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Nat Prod. 2023 Feb 24;86(2):290-306. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.2c00908, PMID 36745506.

He M, Yasin K, Yu S, Li J, Xia L. Total flavonoids in Artemisia absinthium L. and evaluation of its anticancer activity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan;24(22):16348. doi: 10.3390/ijms242216348, PMID 38003540.

Shoaib M, Ghias M, Shah SW, Ali N, Umar MN, A. Synthetic flavonols and flavones: a future perspective as anticancer agents. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2019;32(3):1081-9. PMID 31278723.

Dehnoee A, Kalbasi RJ, Tavakoli S, Zangeneh MM, Zangeneh A, Delnavazi MR. Anticancer potential of furanocoumarins and flavonoids of Heracleum persicum fruit; 2023. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3073212/v1.

Tuzimski T, Petruczynik A, Plech T, Kapron B, Makuch Kocka A, Szultka Mlynska M. Determination of selected isoquinoline alkaloids from Chelidonium majus Mahonia aquifolium and Sanguinaria canadensis extracts by liquid chromatography and their in vitro and in vivo cytotoxic activity against human cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Mar 28;24(7):6360. doi: 10.3390/ijms24076360, PMID 37047332.

Nazemoroaya Z, Sarafbidabad M, Mahdieh A, Zeini D, Nyström B. Use of Saponinosomes from Ziziphus spina-christi as anticancer drug carriers. ACS Omega. 2022 Aug 16;7(32):28421-33. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c03109, PMID 35990496.

Mir SA, Dar A, Hamid L, Nisar N, Malik JA, Ali T et al. Flavonoids as promising molecules in the cancer therapy: an insight. Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov. 2024 Jan 1;6:100167. doi: 10.1016/j.crphar.2023.100167, PMID 38144883.

Dhyani P, Quispe C, Sharma E, Bahukhandi A, Sati P, Attri DC et al. Anticancer potential of alkaloids: a key emphasis to colchicine, vinblastine, vincristine, vindesine, vinorelbine and vincamine. Cancer Cell Int. 2022 Jun 2;22(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12935-022-02624-9, PMID 35655306.

Ionkova I, Shkondrov A, Zarev Y, Kozuharova E, Krasteva I. Anticancer secondary metabolites: from ethnopharmacology and identification in native complexes to biotechnological studies in species of genus Astragalus L. and Gloriosa L. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022 Sep;44(9):3884-904. doi: 10.3390/cimb44090267, PMID 36135179.

Shin SA, Moon SY, Kim WY, Paek SM, Park HH, Lee CS. Structure-based classification and anti-cancer effects of plant metabolites. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Sep 6;19(9):2651. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092651, PMID 30200668.

Sevastre AS, Manea EV, Popescu OS, Tache DE, Danoiu S, Sfredel V et al. Intracellular pathways and mechanisms of colored secondary metabolites in cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 1;23(17):9943. doi: 10.3390/ijms23179943, PMID 36077338.

Puskulluoglu M, Michalak I. The therapeutic potential of natural metabolites in targeting endocrine-independent HER-2-negative breast cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2024 Mar 4;15:1349242. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1349242, PMID 38500769.

Fakhri S, Moradi SZ, Farzaei MH, Bishayee A. Modulation of dysregulated cancer metabolism by plant secondary metabolites: a mechanistic review. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022 May 1;80:276-305. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.02.007, PMID 32081639.

Zhan X, Li J, Zhou T. Targeting Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress response signaling pathways as new therapeutic strategy for pituitary adenomas. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Mar 24;12:565748. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.565748, PMID 33841137.

Barani M, Sangiovanni E, Angarano M, Rajizadeh MA, Mehrabani M, Piazza S. Phytosomes as innovative delivery systems for phytochemicals: a comprehensive review of literature. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021 Oct;16:6983-7022. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S318416, PMID 34703224.

Hashemzadeh H, Hanafi Bojd MY, Iranshahy M, Zarban A, Raissi H. The combination of polyphenols and phospholipids as an efficient platform for delivery of natural products. Sci Rep. 2023 Feb 13;13(1):2501. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-29237-0, PMID 36781871.

PubChem. Available from: https://pubchem.vinblastine.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/13342. [Last accessed on 19 Apr 2025].

PubChem. Available from: https://pubchem.vincristine.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5978. [Last accessed on 19 Apr 2025].

Liu Z, Zheng Q, Chen W, Wu M, Pan G, Yang K. Chemosensitizing effect of Paris saponin I on camptothecin and 10-hydroxycamptothecin in lung cancer cells via p38 MAPK, ERK, and Akt signaling pathways. Eur J Med Chem. 2017 Jan 5;125:760-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.09.066, PMID 27721159.

Singh S, Pandey VP, Yadav K, Yadav A, Dwivedi UN. Natural products as anti-cancerous therapeutic molecules targeted towards topoisomerases. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2020 Nov 1;21(11):1103-42. doi: 10.2174/1389203721666200918152511, PMID 32951576.

Sudhakaran M, Sardesai S, Doseff AI. Flavonoids: new frontier for immuno-regulation and breast cancer control. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019 Apr;8(4):103. doi: 10.3390/antiox8040103, PMID 30995775.

Ranjan A, Ramachandran S, Gupta N, Kaushik I, Wright S, Srivastava S. Role of phytochemicals in cancer prevention. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Jan;20(20):4981. doi: 10.3390/ijms20204981, PMID 31600949.

Chimento A, D’Amico M, De Luca A, Conforti FL, Pezzi V, De Amicis F. Resveratrol, epigallocatechin gallate and curcumin for cancer therapy: challenges from their pro-apoptotic properties. Life (Basel). 2023 Jan 17;13(2):261. doi: 10.3390/life13020261, PMID 36836619.

Maleki Dana P, Sadoughi F, Asemi Z, Yousefi B. The role of polyphenols in overcoming cancer drug resistance: a comprehensive review. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2022 Jan 3;27(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s11658-021-00301-9, PMID 34979906.

Kumar Vishwakarma D, Narayan Mishra J, Kumar Shukla A, Pratap Singh A. Phytosomes as a novel approach to drug delivery system. In: Afrin F, Bhuniya S, editors. Smart drug delivery systems-futuristic window in cancer therapy. IntechOpen; 2024. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.113914.

Shriram RG, Moin A, Alotaibi HF, Khafagy ES, Al Saqr A, Abu Lila AS. Phytosomes as a plausible nano-delivery system for enhanced oral bioavailability and improved hepatoprotective activity of silymarin. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022 Jun 24;15(7):790. doi: 10.3390/ph15070790, PMID 35890088.

Zandavar H, Afshari Babazad M. Secondary metabolites: alkaloids and flavonoids in medicinal plants. In: Ivanišová E, editor. Herbs and spices-new advances. IntechOpen; 2023. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.108030.

Saadaoui I, Rasheed R, Abdulrahman N, Bounnit T, Cherif M, Al Jabri H. Algae-derived bioactive compounds with anti-lung cancer potential. Mar Drugs. 2020 Apr 8;18(4):197. doi: 10.3390/md18040197, PMID 32276401.

Tamzi NN, Rahman MM, Das S. Recent advances in marine-derived bioactives towards cancer therapy. Int J Transl Med. 2024 Dec;4(4):740-81. doi: 10.3390/ijtm4040051.

Martínez KA, Saide A, Crespo G, Martin J, Romano G, Reyes F. Promising antiproliferative compound from the green microalga dunaliella tertiolecta against human cancer cells. Front Mar Sci. 2022 Feb 17;9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.778108.

Frazzini S, Rossi L. Anticancer properties of macroalgae: a comprehensive review. Mar Drugs. 2025 Feb;23(2):70. doi: 10.3390/md23020070, PMID 39997194.

Hu Y, Lin Q, Zhao H, Li X, Sang S, McClements DJ. Bioaccessibility and bioavailability of phytochemicals: influencing factors, improvements, and evaluations. Food Hydrocoll. 2023 Feb;135:108165. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.108165.

Liu Y, Li S, Liu X, Sun H, Yue T, Zhang X. Design of small nanoparticles decorated with amphiphilic ligands: self-preservation effect and translocation into a plasma membrane. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019 Jul 10;11(27):23822-31. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b03638, PMID 31250627.

Jogpal V, Sanduja M, Dutt R, Garg V, Tinku. Advancement of nanomedicines in chronic inflammatory disorders. Inflammopharmacology. 2022 Apr;30(2):355-68. doi: 10.1007/s10787-022-00927-x, PMID 35217901.

Ames CL, Klompen AM, Badhiwala K, Muffett K, Reft AJ, Kumar M. Cassiosomes are stinging-cell structures in the mucus of the upside-down jellyfish cassiopea xamachana. Commun Biol. 2020 Feb 13;3(1):67. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-0777-8, PMID 32054971.

Paul W, Sharma CP. Inorganic nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery. In: Biointegration of medical implant materials. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2020. p. 333-73. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-102680-9.00013-5.

Umashankar DD. Plant secondary metabolites as regenerative medicine. J Phytopharmacol. 2020 Aug 12;9(4):270-3. doi: 10.31254/phyto.2020.9410.

Chauhan D, Yadav PK, Sultana N, Agarwal A, Verma S, Chourasia MK. Advancements in nanotechnology for the delivery of phytochemicals. J Integr Med. 2024 Jul;22(4):385-98. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2024.04.005, PMID 38693014.

Pons-Faudoa FP, Ballerini A, Sakamoto J, Grattoni A. Advanced implantable drug delivery technologies: transforming the clinical landscape of therapeutics for chronic diseases. Biomed Microdevices. 2019 Jun;21(2):47. doi: 10.1007/s10544-019-0389-6, PMID 31104136.

Sakure K, Patel A, Pradhan M, Badwaik HR. Recent trends and future prospects of phytosomes: a concise review. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2024;86(3):772-90. doi: 10.36468/pharmaceutical-sciences.1334.

Phytosome. A fatty solution for efficient formulation of phytopharmaceuticals; 2024 Oct 22. Research Gate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280996888_Phytosome_A_Fatty_Solution_for_Efficient_Formulation_of_Phytopharmaceuticals. [Last accessed on 19 Apr 2025].

Koppula S, Shaik B, Maddi S. Phytosomes as a new frontier and emerging nanotechnology platform for phytopharmaceuticals: therapeutic and clinical applications. Phytother Res. 2025;39(5):2217-49. doi: 10.1002/ptr.8465, PMID 40110760.

Vighne RC, Deore SL, Baviskar BA. A comparative investigation on the phytosomes of diverse bioactive nootropic medicinal herbs. Pharmacogn Rev. 2025;18(36):117-26. doi: 10.5530/phrev.20241898.

Talebi M, Shahbazi K, Dakkali MS, Akbari M, Almasi Ghale R, Hashemi S. Phytosomes: a promising nanocarrier system for enhanced bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy of herbal products. Phytomed Plus. 2025 May 1;5(2):100779. doi: 10.1016/j.phyplu.2025.100779.

Gaikwad SS, Morade YY, Kothule AM, Kshirsagar SJ, Laddha UD, Salunkhe KS. Overview of phytosomes in treating cancer: advancement, challenges, and future outlook. Heliyon. 2023 May 24;9(6):e16561. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16561, PMID 37260890.

Usman M, Khan WR, Yousaf N, Akram S, Murtaza G, Kudus KA. Exploring the phytochemicals and anti-cancer potential of the members of fabaceae family: a comprehensive review. Molecules. 2022 Jun 16;27(12):3863. doi: 10.3390/molecules27123863, PMID 35744986.

Iqubal MK, Chaudhuri A, Iqubal A, Saleem S, Gupta MM, Ahuja A. Targeted delivery of natural bioactives and lipid-nanocargos against signaling pathways involved in skin cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2021 Dec 1;28(39):8003-35. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666201104151752, PMID 33148148.

Chaudhary K, Rajora A. Phytosomes: a critical tool for delivery of herbal drugs for cancer. Phytochem Rev. 2025 Feb 1;24(1):165-95. doi: 10.1007/s11101-024-09947-7.

Mairuae N, Noisa P, Palachai N. Phytosome-encapsulated 6-gingerol- and 6-shogaol-enriched extracts from Zingiber officinale roscoe protect against oxidative stress-induced neurotoxicity. Molecules. 2024 Dec 22;29(24):6046. doi: 10.3390/molecules29246046, PMID 39770133.

Mouhid L, Corzo Martinez M, Torres C, Vazquez L, Reglero G, Fornari T. Improving in vivo efficacy of bioactive molecules: an overview of potentially antitumor phytochemicals and currently available lipid-based delivery systems. J Oncol. 2017;2017(1):7351976. doi: 10.1155/2017/7351976, PMID 28555156.

Gupta MK, Sansare V, Shrivastava B, Jadhav S, Gurav P. Comprehensive review on use of phospholipid-based vesicles for phytoactive delivery. J Liposome Res. 2022 Jul 3;32(3):211-23. doi: 10.1080/08982104.2021.1968430, PMID 34727833.

Barani M, Sangiovanni E, Angarano M, Rajizadeh MA, Mehrabani M, Piazza S. Phytosomes as innovative delivery systems for phytochemicals: a comprehensive review of literature. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021 Oct 15;16:6983-7022. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S318416, PMID 34703224.

Singh D, Shukla G. The multifaceted anticancer potential of luteolin: involvement of NF-κB, AMPK/mTOR, PI3K/Akt, MAPK, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways. Inflammopharmacology. 2025 Feb 1;33(2):505-25. doi: 10.1007/s10787-024-01596-8, PMID 39543054.

Wanjiru J, Gathirwa J, Sauli E, Swai HS. Formulation, optimization, and evaluation of Moringa oleifera Leaf polyphenol-loaded phytosome delivery system against breast cancer cell lines. Molecules. 2022 Jul 11;27(14):4430. doi: 10.3390/molecules27144430, PMID 35889305.

Upaganlawar A, Polshettiwar S, Raut S, Tagalpallewar A, Pande V. Effective cancer management: inimitable role of phytochemical-based nano-formulations. Curr Drug Metab. 2022 Sep 1;23(11):869-81. doi: 10.2174/1389200223666220905162245, PMID 36065928.

Khan T, Gurav P. Phytonanotechnology: enhancing delivery of plant-based anti-cancer drugs. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:1002. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.01002, PMID 29479316.

Dutt Y, Pandey RP, Dutt M, Gupta A, Vibhuti A, Raj VS. Liposomes and phytosomes: nanocarrier systems and their applications for the delivery of phytoconstituents. Coord Chem Rev. 2023 Sep 15;491:215251. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215251.

Wanjiru J, Gathirwa J, Sauli E, Swai HS. Formulation, optimization, and evaluation of Moringa oleifera Leaf polyphenol-loaded phytosome delivery system against breast cancer cell lines. Molecules. 2022 Jan;27(14):4430. doi: 10.3390/molecules27144430, PMID 35889305.

Maheshwari P, Daniel V. Advanced applications of phytosomes in cancer therapy: innovations, challenges, and future perspectives. Int J Newgen Res Pharm Healthc. 2024 Dec 31:156-75. doi: 10.61554/ijnrph.v2i2.2024.101.

Wang H, Li L, Ye J, Dong W, Zhang X, Xu Y. Improved safety and anti-glioblastoma efficacy of CAT3-encapsulated SMEDDS through metabolism modification. Molecules. 2021 Jan;26(2):484. doi: 10.3390/molecules26020484, PMID 33477555.

Klojdova I, Milota T, Smetanova J, Stathopoulos C. Encapsulation: a strategy to deliver therapeutics and bioactive compounds? Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023 Mar;16(3):362. doi: 10.3390/ph16030362, PMID 36986462.

Komeil IA, Abdallah OY, El-Refaie WM. Surface-modified genistein phytosome for breast cancer treatment: in vitro appraisal, pharmacokinetics, and in vivo antitumor efficacy. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2022 Dec 1;179:106297. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2022.106297, PMID 36156294.

Strohbehn GW, Stadler WM, Boonstra PS, Ratain MJ. Optimizing the doses of cancer drugs after usual dose finding. Clin Trials. 2024 Jun 1;21(3):340-9. doi: 10.1177/17407745231213882, PMID 38148731.

Deleanu M, Toma L, Sanda GM, Barbalata T, Niculescu LS, Sima AV. Formulation of phytosomes with extracts of ginger rhizomes and rosehips with improved bioavailability, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in vivo. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Apr;15(4):1066. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15041066, PMID 37111552.

PK, RK. Phytosome technology: a novel breakthrough for the health challenges. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e68180. doi: 10.7759/cureus.68180, PMID 39347133.

Gnananath K, Sri Nataraj K, Ganga Rao B. Phospholipid complex technique for superior bioavailability of phytoconstituents. Adv Pharm Bull. 2017 Apr;7(1):35-42. doi: 10.15171/apb.2017.005, PMID 28507935.

SEM and DLS: complementary techniques for particle analysis. Nanoscience Analytical; 2024. Available from: https://www.nanoscience-analytical.com/sem-dls-complementary-techniques-for-particle-analysis. [Last accessed on 20 Apr 2025].

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) nanoparticle analysis. Available from: https://nanocomposix.nanocomposix.com/products/dynamic-light-scattering-dls-nanoparticle-analysis. [Last accessed on 20 Apr 2025].

Tafish AM, El-Sherbiny M, Al-Karmalawy AA, Soliman OA, Saleh NM. Carvacrol-loaded phytosomes for enhanced wound healing: molecular docking, formulation, DoE-aided optimization, and in vitro/in vivo evaluation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2023 Oct 12;18:5749-80. doi: 10.2147/ijn.S421617, PMID 37849641.

Dewi MK, Muhaimin M, Joni IM, Hermanto F, Chaerunisaa AY. Fabrication of phytosome with enhanced activity of Sonneratia alba: formulation modeling and in vivo antimalarial study. Int J Nanomedicine. 2024 Sep 11;19:9411-35. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S467811, PMID 39282578.