Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 52-63Review Article

NEUROPROTECTIVE ROLES OF BDNF AND NGF IN ARSENIC-INDUCED NEUROTOXICITY: MECHANISMS AND THERAPEUTIC IMPLICATIONS

AYUSH CHAURASIA1 , ZEESHAN ANSARI1, G. HEMA2, ANJU SINGH1, AJAY KUMAR GUPTA*1

, ZEESHAN ANSARI1, G. HEMA2, ANJU SINGH1, AJAY KUMAR GUPTA*1

1School of Pharmaceutical Sciences (formerly University Institute of Pharmacy), Chhatrapati Shahu Ji Maharaj University campus, Kanpur-208024, India. 2Department of Biotechnology, Maharani’s Science College for Women, Maharani Cluster University, Palace Road, Bangalore, India

*Corresponding author: Ajay Kumar Gupta; *Email: ajaykumargupta@csjmu.ac.in

Received: 24 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 18 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Arsenic-induced neurotoxicity is increasingly recognized as a major global health issue, leading to both developmental and degenerative neurological impairments, therefore, arsenic is becoming one of the potent environmental neurotoxins that can lead to significant health risks, particularly through long-term exposure via water, food, and air. Arsenic exposure can initiate a range of pathological events such as-disruption of mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammatory processes, which result in neuronal damage and cognitive dysfunction. Conversely, neurotrophins growth factors that regulate neuronal survival, growth, and function, are emerging as promising neuroprotective agents against such neurotoxic effects. This article explores the neuroprotective roles of BDNF (Brain-derived neurotrophic factor) and NGF (Nerve growth factor) in counteracting arsenic-induced neurodegeneration, through the analysis of epidemiology and mechanism-based preclinical studies of last decade.

Arsenic disrupts neurotrophin signaling by inhibiting Trk (Tropomyosin receptor kinase) receptor phosphorylation and downstream survival pathways PI3K-AKT (Phosphoinositide 3-kinase–Protein kinase B), ERK-CREB (Extracellular signal-regulated kinase-cAMP response element-binding protein), thus contributing to neurodegeneration. In animal models, BDNF supplementation exhibited reduction in oxidative stress by 45–60%, neuronal apoptosis declined by about 55%, and improvement in cognitive function up to 40%. Additionally, NGF supplementation shows a 40-55% reduction in apoptosis. By integrating toxicological mechanisms with therapeutic perspectives, this narrative review underscores the potential of neurotrophin-based strategies to mitigate arsenic-related neurodegeneration and highlights future research directions for translational applications.

Keywords: Arsenic, Neurotoxicity, Neurotrophins, BDNF, NGF, Neuroprotection

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54728 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Surrounding of the animal kingdom directly or indirectly affect their nervous systems, heavy metal contaminations are emerging as major threat for animal kingdom. Arsenic is among the top five contaminants that affecting health. The earth's crust includes naturally occurring arsenic, which is dangerous in its inorganic trivalent form rather than its biological form. Global arsenic exposure primarily occurs through contaminated drinking water and food, especially in countries such as Bangladesh, India, China, Mexico, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Nepal, The United States, Cambodia, Mongolia, and Chile over 140 million people are estimated to consume water exceeding the WHO provisional guideline of 10 µg/l, making it a critical public health concern. Hence, like other parts of the world, Asia is believed to be more severely impacted by Arsenic contamination [1]. Furthermore, it was ranked as a top priority on the ATSDR (Agency for toxic substances and disease registry's) list until 2020 [2, 3]. Due to its high reducing potential and interactions with various molecules, particularly sulfur, chloride, and oxygen, arsenic can create organic compounds by bonding with carbon-containing molecules [4]. Nearly every individual is now at risk of chronic exposure to either low or high levels of this toxicant. Inhalation and ingestion are the two major routes through which arsenic enters the human body. However, compared to the pentavalent version, trivalent arsenic oxide is more lipid soluble, and it can also be absorbed through the skin to a certain extent. Recent studies indicate that general public exposure to arsenic primarily occurs through the consumption of Arsenic contaminated food and water, while inhalation plays a less significant role. The majority of arsenic that is ingested or inhaled is rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream through the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. Once absorbed, approximately 95% to 99% of trivalent arsenic is processed in the body and binds to hemoglobin within erythrocytes and is subsequently transported to various organs such as liver, kidneys, skin, and lungs. The liver can convert (in a limit) the arsenic that enters the body into a less harmful methylated derivative, which is eliminated through urine [5].

A family of proteins known as neurotrophins helps neurons grow, survive, and differentiate. In 1988, the word "neurotrophin" was initially came out. After the finding that neurotrophins, which are survival factors, may be secreted by neuronal cells. After a thorough investigation, it was discovered that neurotrophins control the formation, preservation, and death of neurons in both the PNS (Peripheral nervous system) and CNS (Central nervous system), respectively. In mammals, the four key neurotrophins are NGF, BDNF, NT-3 (Neurotrophin-3) and NT-4/5 (Neurotrophin-4/5). NGF was the first of these neurotrophins to be identified by Levi-Montalcini and Hamburger in the 1950s, who found that a protein released by a mouse sarcoma tumor placed near a developing chicken’s spinal cord could stimulate neurite outgrowth originating from sympathetic neurons, that protein was later named as NGF [6]. The discovery of novel soluble growth factors was made possible by the discovery of NGF, the first growth factor ever discovered, having nourishing impact on sympathetic and sensory neurons. BDNF, the second identified member of the neurotrophic factor family, was obtained from pig brain after it was demonstrated in 1982 to support the viability of a subgroup of neurons in the dorsal root ganglia. Additional neurotrophin family members, including NT-3 and NT-4/5, have been recognized; each exhibits a distinct pattern of supportive effects on specific neuron subpopulations in the PNS and CNS [7]. NT-3 is highly expressed in the hippocampus and has been shown to enhance BDNF mRNA levels and alter BDNF signaling. It can also promote neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity. NT-4/5 functions similarly to BDNF by attaching itself to TrkB (Tropomyosin receptor kinase B) and encouraging neuronal growth [8, 9]. Although oxidative damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation have been well-documented in arsenic-induced neurotoxicity, the role of neurotrophins such as BDNF and NGF in mediating these effects is not fully understood. While previous reviews have explored neurotrophin involvement in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [6, 10]. They often overlook their potential role in environmental neurotoxic exposures. Similarly, arsenic-related reviews have focused primarily on redox imbalance and inflammatory signaling with limited integration of neurotrophin signaling pathway [11]. This review aims to bridge this knowledge gap by synthesizing recent findings on the modulation of BDNF and NGF in arsenic-induced neurotoxicity and evaluating their therapeutic potential.

Methodology

A wide-ranging literature search was conducted across databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus via keywords such as “Neurotoxicity,” “Arsenic,” “Neuroprotection,” “Neurotrophins,” and “BDNF and NGF.” Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to refine the search queries. In addition, the reference lists of relevant papers were examined to identify additional studies not captured in the initial search. The search covered publications of the last decade.

Included studies were peer-reviewed and taken articles that are published in English. The review considered original research articles involving in vivo animal models that assessed arsenic-induced neurotoxicity. Review articles relevant to the molecular mechanisms of arsenic toxicity and neurotrophin signaling were also included to support background context and interpretation.

In vitro studies, editorials, conference abstracts, non-peer-reviewed materials, studies not reporting relevant neurotoxic outcomes and articles unrelated to neurotrophins or arsenic-induced neurotoxicity were excluded from this review. No formal quality assessment tools were applied due to the narrative nature of the review.

Arsenic occurrence

A metalloid named arsenic could occur in water, soil, and air due to sources that are both environmental and anthropogenic. It occurs in forms that are inorganic and organic, and it has been found in a variety of oxidation states (−3, 0,+3,+5). Both arsenic (iii) and (v) oxidation states of arsenic are the main considerations of toxicology researchers when it comes to exposure in the environment. As5+(Arsenate) and As3+(Arsenite), which are the more commonly recognized arsenic compounds, represent the negatively charged forms of arsenic acid and arsenous acid, respectively [12]. A major worldwide health issue affecting millions of people is the toxicity of arsenic. As a result of arsenic that comes from geological sources pouring into manufacturing and other industrial operations, in addition to poisoning drinking water in aquifers [13]. The toxicity of arsenic varies widely among mammals, and humans are likely to be more vulnerable than the majority of test animals [14]. Humans, along with a number of other organisms utilize methylation to detoxify inorganic arsenic, mostly forming DMA (Dimethylarsinic acid). DMA is less noxious, less likely to interact with bodily tissue, and more easily excreted through urine compared to inorganic arsenic [13]. The main ways that this metalloid is exposed are through tainted water and food. In many regions, arsenic levels in drinking water exceed recommended exposure limits. According to a tentative WHO recommendation, more than 142 million individuals in 50 countries are exposed to arsenic-contaminated water with concentrations exceeding 10μg/l [15]. Groundwater in several nations, such as India, Bangladesh, Mexico, Chile, China, Argentina, and the United States, naturally contains high levels of arsenic. It a toxicant that affects almost all organs and tissues, it has been linked to serious health consequences, such as skin lesions, multiple forms of cancer, and cardiovascular, respiratory, and gastrointestinal disorders. Additionally, this metalloid poses significant neurotoxic risks, contributing to peripheral neuropathies, encephalopathy, and neurobehavioral alterations [11]. It has also been linked to neurodegeneration. Even though epidemiological and toxicological research has demonstrated the neurotoxic effects of arsenic, this subject is still developing. It ranks as the fifth most prevalent element in the human body and is widely found in water, air, soil, and throughout the geological layers. Arsenic compounds are classified into two categories: iAs (Inorganic) and organic. iAs exists in two primary state-As³⁺ and As⁵⁺. In addition to being employed as an alloying element in electronics, iAs is now utilized as a wood preservative in agricultural products and in the treatment of leukemia. The WHO-recommended exposure limits of 10 parts per billion have been exceeded by at least 140 million individuals across 50 nations. The content of iAs in groundwater might surpass 1000 parts per billion in polluted locations [16].

Neurotoxic effects of arsenic on the nervous system

Effects on gestational development and growth

We currently lack a comprehensive knowledge of iAs neurotoxicity throughout pregnancy and development. However, it has been shown by toxicological and epidemiological investigations that encounter with iAs during development has affects the cognitive and intellectual performance are discussed in table 1. Moreover, even below the current safety recommendations, iAs exposures have been linked to reduced overall IQ and alterations in memory function. Children in Bangladesh, the United States, and Mexico are affected by iAs concentrations in water between 5 and 50 ppb, exhibiting neurobehavioral alterations, including decline in long-term storage, motor function, IQ, cognitive function, and language abilities. NaAsO2 (Sodium Arsenite) exposure during pregnancy increases its accumulation in the brain of offspring mice and disrupts their memory and learning processes. Additionally, behavioral abnormalities and abnormal prefrontal cortical region development in adult-born offspring are caused by prenatal exposure of mice to NaAsO2 [17].

Effects on the adult nervous system

Numerous studies have shown a strong link between iAs exposure and changes in adult mental health and cognitive function, although epidemiological evidence regarding the effects of iAs exposure in adults remains limited, as presented in table 1 [18]. These effects include peripheral nerve dysfunction, delayed nerve signal transmission, nerve damage, and sensory processing changes [19]. Following a single exposure to iAs, four individuals developed peripheral neuropathy, which manifested as severe disturbances in sensory nerve action potentials and decreased motor conduction velocity. In the sciatic nerves of rats exposed to iAs, neurofilament and fibroblast proteins also abolished. Additionally, iAs exposure in rats causes oxidative damage, demyelination, and structural abnormalities in peripheral nerve axons, which may result in reduced information transmission from peripheral sensory receptors to the CNS [20].

Neural degeneration

Neurodegeneration cannot be shown by exposure to iAs alone, according to several studies. Yet, the neurotoxic effects of iAs may be correlated with or work in concert with the molecular causes of neurodegeneration, including inflammation, ROS (Reactive oxygen species) imbalance, and disruption of mitochondrial function. A case-control study found that higher concentrations of iAs and DMA, along with reduced selenium levels in urine, were linked to a heightened risk of developing AD (Alzheimer's disease). iAs has the ability to cause dementia and vascular damage in vivo [21]. Chronic iAs exposure causes behavioral deficits in rats along with elevated BACE-1 (β-secretase 1) activity, Aβ (Amyloid-β) formation, and RAGE (Receptor for advanced glycation end products) Expression. In transgenic AD animal models, iAs has been correlated with bioenergetic dysfunction and disruptions in redox metabolism, exacerbating Aβ accumulation and phosphorylated Tau immunoreactivity [22]. When iAs are mixed with other heavy metals, their pro-amyloidogenic effects are amplified, and it is linked to linked to oxidative damage and neuroinflammation. Consequently, iAs raises pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in astrocytes, which are correlated with increased BACE-1 and APP (Amyloid precursor protein) levels. Although it does not directly cause neurodegeneration in vivo, iAs can synergize with dopamine to cause neurotoxicity and increase the biomarkers of proteotoxic stress, leading to the accumulation and oligomerization of α-synuclein, a primary pathological characteristic of PD (Parkinson's disease). According to these results, exposure to iAs may make people more vulnerable to neurodegeneration [17].

Table 1: Overview of inorganic arsenic-induced neurotoxicity in humans and animal models

| Subject | Exposure conditions | Dose/Duration | Reported neurotoxic outcomes | References |

| Human (Adult) | Long-term exposure in Bangladesh | 129–265 μg/l | Progressive reduction in plasma cholinesterase, an enzyme linked to liver and neural function. | [23] |

| Indian population; decreased exposure from 190.1 to 37.94μg/l over 5 y | 190.1 to 37.94 μg/l for 5 y | Increased cases of neuropathy, eye irritation, and respiratory symptoms. | [24] | |

| Chronic exposure in India | 129 μg/l | Elevated neuropathy-related markers like miR-29a and PMP22. | [25] | |

| Single arsenic dose | 250–20,000 μg/l single dose | Peripheral nerve impairment, slower motor signals, and abnormal sensory responses. | [1] | |

| Sub-chronic | 10,000-50,000 μg/l/7 mo | Peripheral nerve disturbances manifest as ongoing weakness, numbness, or pain. | [26] | |

| Human (Child) | Bangladesh | 10 μg/l | Impaired coordination and fine motor function. | [27] |

| Mexico | 63 μgAs/g creatinine | Deficits in verbal intelligence, comprehension, and memory. | [1] | |

| Mexico | >50 μg/l | ↓cognitive, visual-spatial, and motor performance. | [28] | |

| U. S.; exposure. | >5μg/l/7.3 y | Lower IQ, memory, and reasoning abilities. | [29] | |

| Rats (Wistar) | Wistar, prenatal to 4 mo. | 3000μg/l | Behavioral issues and elevated Alzheimer’s biomarkers. | [30] |

| Acute exposure | 15–20 mg/kg/single dose | Structural protein loss and cytoskeletal abnormalities. | [31] | |

| Sub-acute exposure | 10 mg/kg/30 days | ↑ Lipid peroxidation, ↓ NCV, conduction area, myelin thickness, axonal area and perimeter. | [32] | |

| Mice | CD-1 mice, (pregnancy exposure) | 20,000 μg/l/during gestation | Altered transporter/receptor expression in brain regions; memory impairment. | [33, 34] |

| C57BL/6 strain | 100,000 μg/l | Reduced synaptic transporters and receptors in striatum. | [35] | |

| Swiss Webster, chronic exposure | 100 μg/l | Increased neurodegeneration markers in striatum and cortex. | [36] |

Abbreviations: ↑: Increase; ↓: Decrease; μg/l: micrograms per liter; NCV: Nerve conduction velocity; μgAs/g: micrograms arsenic per g of creatinine; miR-29a: MicroRNA-29a; PMP22: Peripheral myelin protein 22.

Mechanisms underlying arsenic-induced toxicity

Arsenic-mediated oxidative stress mechanisms

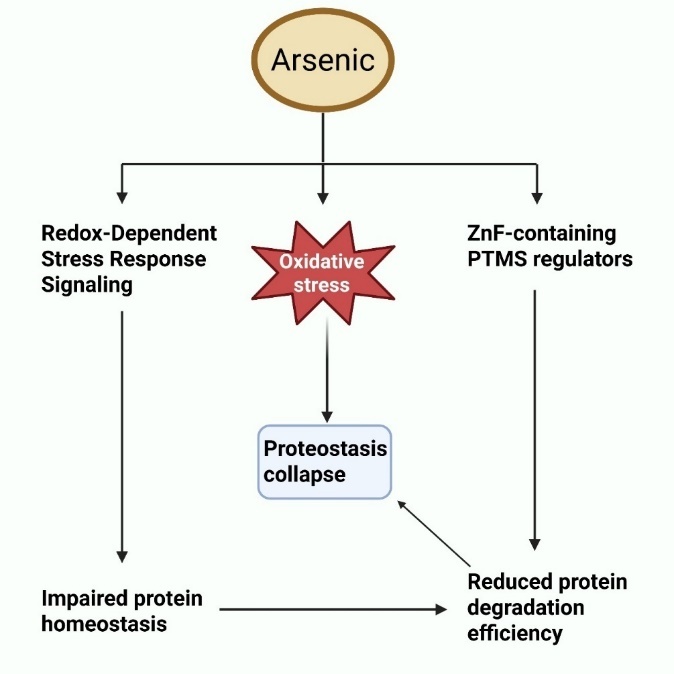

Arsenic toxicity is primarily driven by the production of oxidative stress, as evidenced by several in vitro and in vivo studies. After exposure, it has been demonstrated that ROS, including superoxide anion radical and hydrogen peroxide, increase in a variety of tissues. A very complicated cycle links oxidative stress and inflammation. ROS can activate several transcription factors, which in turn enhance the expression of pro-oxidant and antioxidant enzymes, as well as inflammatory cytokines [37]. Moreover, they can activate and attract phagocytic leukocytes to inflammatory areas, where they can release enzymes that intensify oxidative stress and raise inflammation. Inflammation and oxidative stress are major contributors to chronic illnesses as shown in [fig. 1]. Therefore, several in vivo models, especially at lower doses or shorter durations, have shown no significant increase in ROS generation, suggesting that arsenic-induced oxidative stress may be tissue-specific or dose-dependent. These discrepancies may reflect compensatory antioxidant responses or limitations in detection sensitivity [38].

Fig. 1: Oxidative stress pathways triggered by arsenic: interference with ZnF (Zinc Finger) proteins and redox-responsive stress response pathways, resulting in disrupted proteostasis, compromised protein stability, and diminished protein degradation efficiency

The following are several ways that arsenic is thought to cause oxidative damage in cells: (i) It is commonly known that arsenic changes mitochondria, reduces membrane potential, and weakens the mitochondrial membrane. These structural changes serve as key locations for excessive superoxide anion generation, initiating a cascade of reactions that culminate in elevated free radical formation. The oxidative defense mechanism breaks down, and harmful symptoms show up when oxidative stress levels keep rising [39].

(ii) The electron transport activity within mitochondria, particularly at complexes I and III, is a major contributor to O₂⁻ (Superoxide anion) formation. Arsenic-induced suppression of succinate dehydrogenase and impairment of oxidative phosphorylation contribute to excess O₂⁻ formation and oxidative stress [40].

(iii) ROS can also be produced by arsenic through processes that include NADPH (Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) oxidase. The e-from internal NADPH are transferred across the membrane by this membrane-bound enzyme, where they combine with oxygen molecules to produce O₂⁻ [41]. In cultured human endothelial cells, arsenic functions as an external stimulus that activates Ras family proteins, such as cdc42, leading to the stimulation of NADPH oxidase and subsequent production of ROS [42].

(iv) Additionally, arsenic can produce ROS by interfering with the NOS (Nitric oxide synthase) enzyme system. L-arginine and molecular oxygen are converted into NO (Nitric Oxide) by NOS iso-enzymes without generating superoxide [43]. This connection is broken by arsenic exposure, which results in ROS.

(v) Under normal conditions, the metabolism of Arsenic (III) to Arsenic (V) promotes the production of H₂O₂ (Hydrogen peroxide) [44].

(vi) Dimethylarsinic peroxyl radicals, which are metabolic byproducts of DMA, are among the intermediate arsine species that are produced during the generation of ROS [45].

(vii) Methylated 3+organic arsenicals undergo an antioxidative reaction with SH-(Sulfhydryl groups) proteins and prevent them from functioning, which causes oxidative stress [46]. Elevated ROS can also damage nuclear and mitochondrial DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid), inducing base modifications, strand breaks, and cross-linking. This activates DNA damage response pathways such as p53 (Tumor protein p53) and PARP (Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase), which can lead to neuronal apoptosis or impaired gene transcription essential for synaptic function. In the brain, such DNA damage contributes to hippocampal atrophy and cognitive dysfunction seen in arsenic-exposed models [47].

Mitochondrial dysfunctions

The operation of other cellular machinery and mitochondria has a complicated interaction that impacts cell viability. Cells rely on mitochondria for energy, and they play crucial roles in the electron transport chain and oxidative phosphorylation [48]. They are yet another significant generator of free radicals in cells. When animals are exposed to xenobiotics like arsenic, their mitochondrial function is disrupted [49]. This is demonstrated by the suppression of mitochondrial oxygen consumption, which results in a disordered membrane potential. A discrepancy in energy expenditure and consumption results from reductions in ATP (Adenosine triphosphate) synthesis and membrane stability [50]. Numerous earlier investigations have revealed that mitochondrial impairment and redox imbalance are the main mechanisms by which arsenic causes neurotoxicity [51]. There have been significant efforts to look at a variety of molecular processes in neuropathological studies in arsenic-induced mitochondrial dysfunction [52]. Studies indicate that arsenic disrupts mitochondrial respiratory function, leading to an overproduction of ROS in several cell types, including neurons [53]. Twelve weeks of arsenic exposure has been found to compromise the function of key mitochondrial enzymes in the brain, particularly those associated with complexes I, II, and IV. Through competition with phosphate because of their similar chemical structures, arsenate can have a major effect on the generation of ATP. This process is called arsenolysis, and it occurs as part of glycolysis. Within this metabolic process, phosphate and G3P (D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate) are normally linked by enzymes to generate 1,3-BPG (1,3-bisphosphoglycerate). In addition to the conventional 1,3-BPG, 1-As-3PG (Anhydride 1-arsenato-3-phosphoglycerate) is formed when arsenate is present because phosphate is substituted with arsenate. The arsenic–oxygen bonds are, on average, around 10% longer than phosphorus–oxygen bonds, making the resulting anhydride unstable and prone to hydrolysis into As5+and 3-phosphoglycerate [54]. The generation of ATP is depleted by these steps. Glycolysis produces ATP when phosphate is present, but this is greatly impaired when As5+is present.

Arsenolysis also affects ATP synthesis at the oxidative phosphorylation stage in the mitochondria [55]. When succinate is present, ADP (Adenosine-5-diphosphate) and As5+are used to create ADP– As5+at the submitochondrial level [56]. When arsenate is present instead of phosphate, ADP– As5+is created because of structural similarities with phosphate. ADP-As5+, in contrast to ATP, is unstable and undergoes further hydrolysis, which results in a considerable reduction in ATP. Dehydrogenase activity was suppressed in mice exposed subchronically to low levels of arsenic trioxide. DNA from the nucleus and mitochondria encode these complexes. More research is needed to describe molecular mechanisms that result in altered gene expression when exposed to arsenic. The mechanisms leading to mitochondrial membrane failure are activated by cellular metabolism and calcium. The alterations in membrane stability, lipid profile, cytoskeletal structure, and reactive species that contribute to cellular dysfunction may all be further explained by these two variables [57]. There is little scientific proof of a connection between neurotoxicity and intracellular calcium levels and dysfunctional mitochondria.

Inflammation

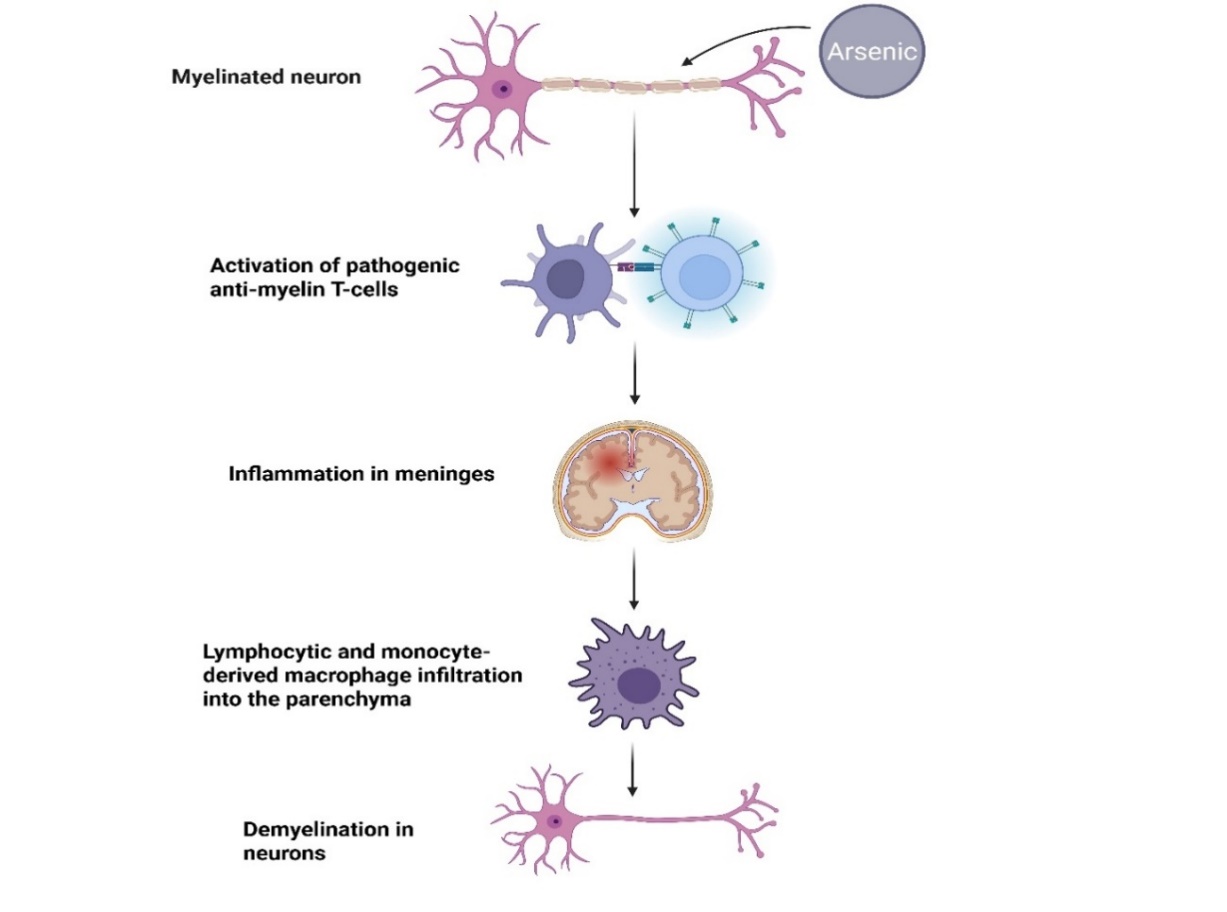

With prolonged arsenic exposure, neurotoxic effects arise, including the disruption of myelination, which impairs neuronal integrity and communication. Arsenic exposure leads to ROS imbalance, triggering the initiation of oxygen-derived free radicals and nitrogen-derived free radicals, which results in cellular damage and initiates cellular inflammatory activity in the CNS [54]. This pro-inflammatory environment stimulates microglia and astrocytes, triggering the production of cytokines like IL-1β (Interleukin-1 beta), IL-6 (Interleukin-6), and TNF-α (Tumor necrosis factor-alpha), which further amplify neurotoxicity [58]. Prolonged arsenic exposure is associated with disruption of myelination, impairing neuronal integrity and communication. When pathogenic anti-myelin T-cells are activated, meningeal damage and macrophage invasion occur, both of which contribute to demyelination. This process results in a loss of trophic support to neurons, leading to decreased nerve conduction velocity and impairments in both motor and sensory functions, as shown in [fig. 2] [54].

Apoptosis

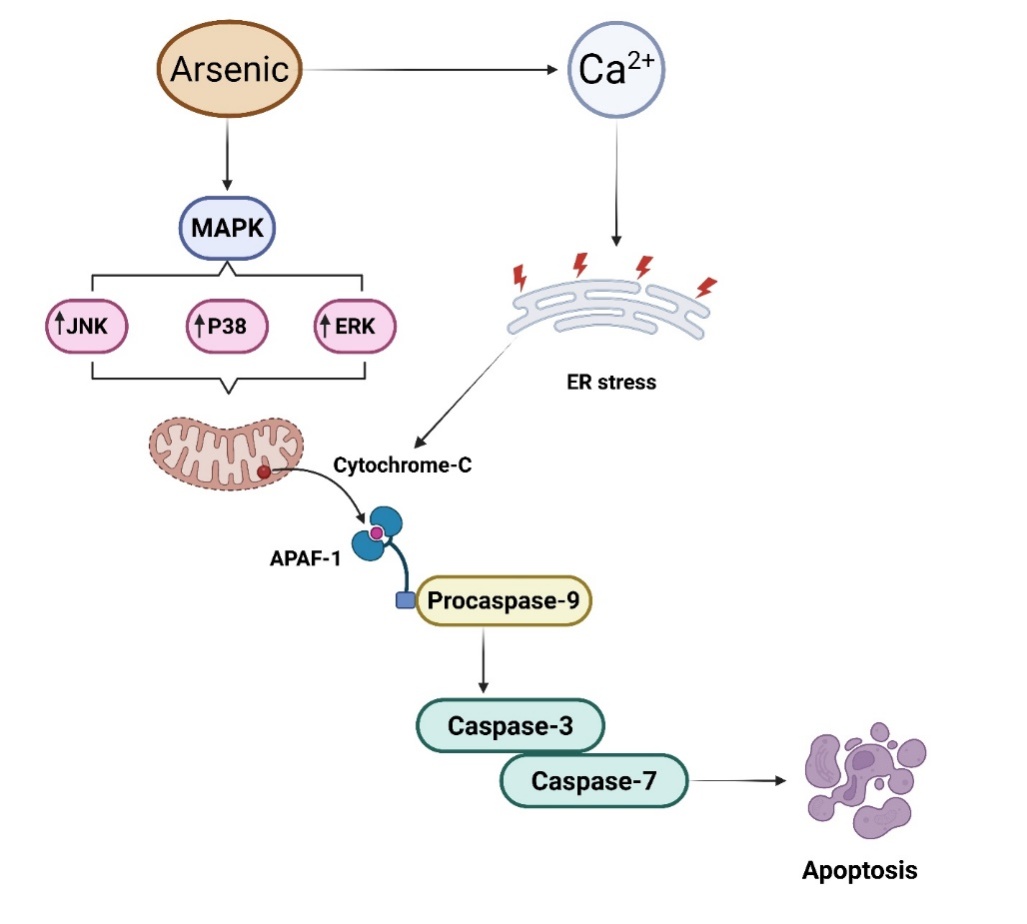

By triggering MAPK (Mitogen-activated protein kinase) signaling, which is primarily mediated by JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase), p38 (Tumor protein p38), and ERK (Extracellular signal-regulated kinase), arsenic exposure causes caspase-dependent death in neuronal cells as shown in [fig. 3]. These kinases react to oxidative stress triggered by arsenic, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptotic cascade activation. Apoptosis in arsenic toxicity can proceed via both the intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (death receptor) pathways. The intrinsic pathway involves mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and cytochrome c release, activating caspase-9 [59]. In contrast, the extrinsic pathway involves activation of death receptors like CD95 (also known as Fas) or TNF-α, which recruit adaptor proteins (e. g., FADD-FAS-associated protein with death domain) to activate caspase-8. Both cascades converge on caspase-3, leading to programmed cell death [60]. Interestingly, some studies report necrotic features such as cell swelling, plasma membrane rupture, and inflammatory infiltration in cortical neurons exposed to high arsenic doses. This suggests that the type of cell death may depend on arsenic dose, cell type, or energy availability. In some cases, necroptosis, a regulated form of necrosis, may be involved. Understanding this balance between apoptosis and necrosis is critical for targeting protective therapies [61]. Additionally, arsenic disrupts intracellular Ca²⁺ (Calcium) homeostasis, promoting endoplasmic reticulum stress and mPTP (Mitochondrial permeability transition pore) opening. This enhances apoptotic signaling by elevating the levels of key pro-apoptotic factors such as cytochrome c and AIF (Apoptosis-inducing factor) [17].

Fig. 2: Pathogenic anti-myelin T-cell activation causes demyelination, subsequently leading to inflammation of the meninges and infiltration of the brain parenchyma by lymphocytes, as well as macrophages derived from monocytes, which ultimately deprives neurons of trophic support

Fig. 3: Arsenic exposure triggers caspase-dependent apoptosis in neuronal cells via MAPK signaling (JNK, p38, ERK), oxidative damage, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cyt-C release activates caspases, contributing to neuronal apoptosis, further amplified by ER stress and disrupted Ca²⁺ homeostasis. MAPK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase; JNK: Jun N-terminal kinase; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; APAF-1: Apoptotic protease activating factor-1

Effects on nerve conduction

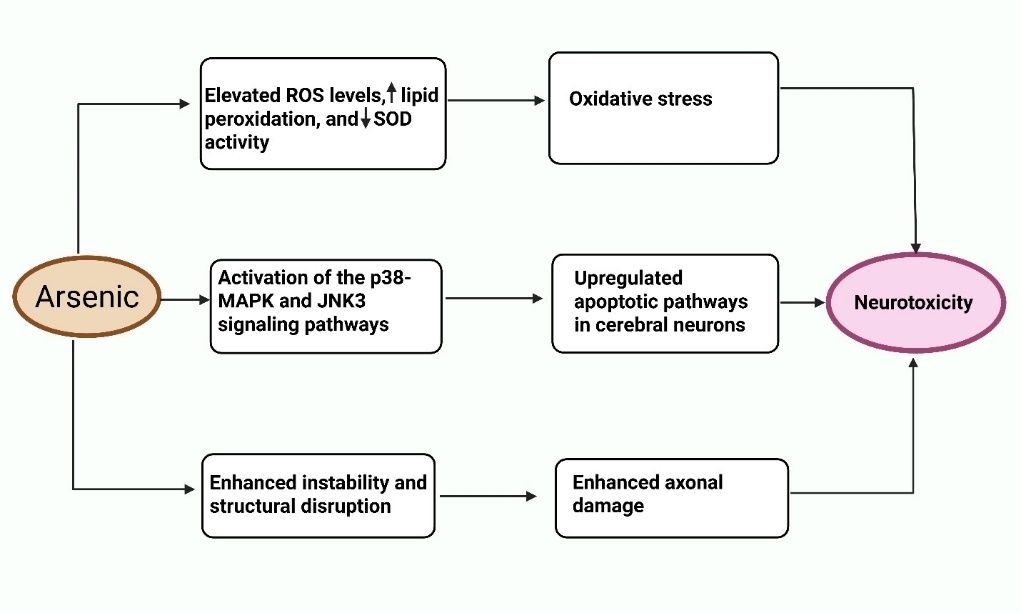

Numerous mechanisms for arsenic-induced neurotoxicity have been identified, as shown in [fig. 4]. The speed at which an electrical impulse passes through a neuron is measured by motor and sensory nerve conduction [62]. During a NCV (Nerve conduction velocity) test, electrodes placed on the skin are used to stimulate a specific nerve. This examination evaluates the extent of nerve damage and impaired function. A decline in neural transmission velocity in the sural-saphenous region, which plays a role in conveying sensory information from the skin, has been recognized as an initial sign of prolonged arsenic-related peripheral neuropathy. Prolonged arsenic exposure has been linked with reduced nerve conduction velocity in Taiwanese adolescents [63]. The median, sural, ulnar, and saphenous nerves all exhibited a significant reduction in nerve conduction in those who were exposed to arsenic long-term. CMAPs (Compound muscle action potentials) were also affected. It has been shown that the NCV of taller patients (>163 cm) is lower than that of shorter subjects. Sensory nerves exhibit greater sensitivity compared to motor nerves in symmetrical peripheral neuropathy, according to several studies, and the larger arm neurons are significantly impacted [54]. Axis cylinders disintegrated, and the number of myelin fibers decreased as a result of myelin breakdown and resorption on the distal part of nerves brought on by arsenic exposure. Arsenic exposure is associated with encephalopathy and impairments of superior brain functioning, according to several additional investigations [64]. Besides its direct effects on neuronal systems, arsenic has been shown to induce oxidative stress, inflammation, and tissue damage in non-neuronal organs. In a rat model, Arsenicum album administration resulted in elevated HDL (High-density lipoprotein) levels and mild liver and kidney toxicity, potentially linked to underlying oxidative and inflammatory responses [65].

Epigenetic modifications in arsenic neurotoxicity

Arsenic-induced neurotoxicity involves not only oxidative and inflammatory processes but also epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation, histone modification, and miRNA (microRNA) regulation. Chronic arsenic exposure has been shown to induce global hypomethylation and gene-specific promoter hypermethylation in brain tissues, leading to altered gene expression patterns linked to neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration [66].

Specifically, miRNAs such as miR-124, miR-29a, and miR-210 are dysregulated by arsenic and have been implicated in pathways related to neuronal apoptosis, inflammation, and synaptic plasticity. These miRNAs can also regulate neurotrophin signaling components such as Trk receptors and downstream PI3K/AKT cascades, suggesting a functional cross-talk between arsenic-induced epigenetic changes and neurotrophin-mediated protection [67].

Fig. 4: Schematic representation of the key molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in arsenic-induced neurotoxicity. Arsenic exposure initiates a cascade of neurotoxic events through three major pathways: (i) increased oxidative stress due to ROS imbalance and decreased antioxidant defense; (ii) activation of p38-MAPK and JNK3 signaling pathways leading to neuronal apoptosis; and (iii) cytoskeletal instability and axonal degeneration, all contributing to neuronal dysfunction

Table 2: Summary of major neurotrophins involved in arsenic-induced neurotoxicity and their neuroprotective roles

| Neurotrophins | Receptor | Functions | Arsenic-induced disruption | Protective role | References |

| BDNF | TrkB | Supports synaptic plasticity, cognition, and neuron survival | Inhibits TrkB phosphorylation, suppresses PI3K-Akt, RAS-MEK-ERK, and PLCγ pathways | 70–80% reduction in memory impairment | [10, 69, 70] |

| NGF | TrkA | Promotes survival and differentiation of sensory neurons | Arsenic impairs NGF-mediated signaling, affecting survival pathways | 40-55% reduction in apoptotic motor neurons | [6, 71, 72] |

| NT-3 | TrkC | Involved in neurogenesis, BDNF signaling, and synaptic plasticity | Disrupted expression under arsenic exposure, indirect BDNF suppression | Boost neuronal and oligodendrocyte differentiation by approximately 10-12% | [8, 9] |

| NT-4/5 | TrkB | Similar function to BDNF in supporting neurons | Limited data, but presumed similar TrkB-related suppression | 16% absolute reduction in neuronal loss. | [9, 69] |

PI3K-Akt: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase–Protein kinase B; RAS-MEK-ERK: Rat sarcoma–Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase–Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; PLCγ: Phospholipase C gamma.

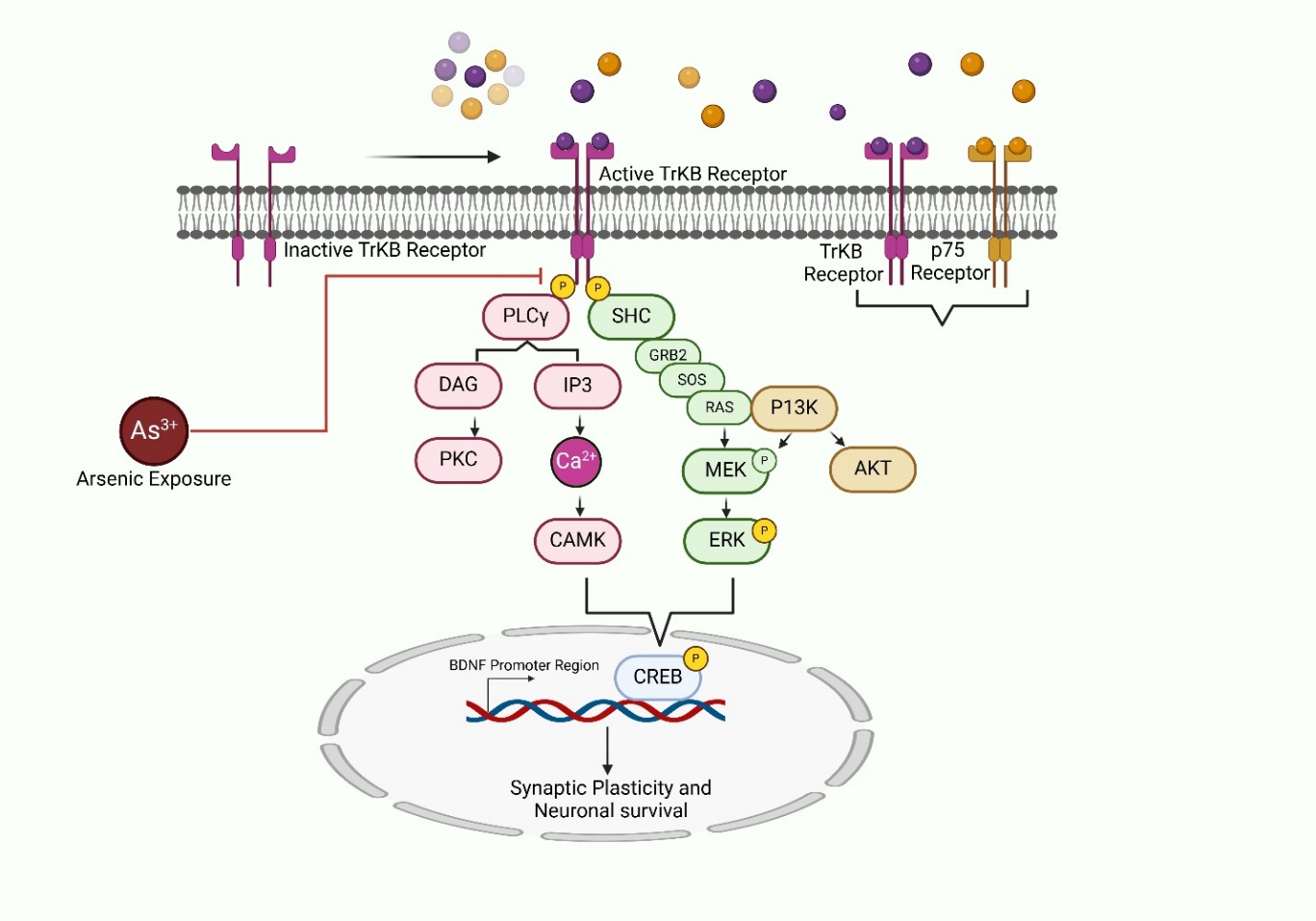

Physiological role of neurotrophins in arsenic-induced neurotoxicity

Neurotrophins, such as BDNF, are essential for preserving synaptic plasticity, neuronal survival, and cognitive processes [68]. These growth factors exert their effects primarily via stimulation of Trk receptors, particularly TrkB, initiating multiple intracellular signaling cascades vital for neuronal health. For better understanding, the roles of various neurotrophins in arsenic-related neuronal damage are summarized in table 2, which provides a comparative summary of their functions, disrupted signaling pathways, and neuroprotective potential. However, exposure to arsenic significantly disrupts neurotrophin signaling pathways, contributing to neurodegeneration and cognitive impairments. Arsenic exposure impairs the activation of TrkB receptors by inhibiting their phosphorylation, leading to the suppression of key downstream cascades like PI3K-AKT and RAS-MEK-ERK (Rat sarcoma–Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase–Extracellular signal-regulated kinase). These pathways are crucial for regulating transcription of neuroprotective genes via the activation of the CREB at the BDNF promoter region [69] [fig. 5]. Illustrates the impact of arsenic on these signaling mechanisms, highlighting how arsenic inhibits TrkB activation, resulting in reduced BDNF expression and subsequent neuronal damage. Additionally, arsenic-induced disruption of the PLCγ (Phospholipase C gamma) pathway interferes with intracellular calcium levels and the activation of CaMK (Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase), further exacerbating neuronal dysfunction. The inhibition of these pathways compromises synaptic plasticity and neuronal survival, as illustrated in the diagram.

In a study performed by Pandey et al., focusing on the role of E2 (Estrogen) and neurotrophins, particularly BDNF, in mediating these effects. Adult rats were exposed to varying doses of arsenic (1x and 10x), with male and ovariectomized female rats used as models for E2 deficiency. Behavioral assessments included passive avoidance and Y-maze tests to measure learning and memory. Results indicated that male rats experienced significant neuronal loss and cognitive decline compared to females, particularly at higher arsenic doses. E2 deficiency in females accelerated neuronal apoptosis and impaired cognitive function, while E2 treatment mitigated these effects, demonstrating the neuroprotective effects of neurotrophins in arsenic induced neurotoxicity [70]. These findings highlight the sex-specific modulation of neurotrophin pathways, with E2 acting as a key enhancer of BDNF expression via ERα-CREB (Estrogen receptor-α) signaling. Female brains may be more resilient to arsenic-induced neurotoxicity due to this hormonal regulation. This aligns with evidence that estrogen enhances synaptic plasticity, TrkB signaling, and mitochondrial function. However, ovariectomized or postmenopausal models lacking estrogen show a sharper decline in BDNF and more severe cognitive deficits. Future studies should explore gender-specific dosing and hormonal co-therapies in arsenic neurotoxicity management.

Similarly, in another study Mehta et al., examined the physiological function of neurotrophins in arsenic-induced neurotoxicity, specifically looking at how RES (Resveratrol) and As₂O₃ (Arsenic Trioxide) interact to affect neurobehavioral functions and neurochemical alterations in female mice's hippocampal regions. Adult mice were exposed to As₂O₃ at doses of 2 and 4 mg/kg BW as well as 40 mg/kg BW in combination with RES over a 45-day period. The findings indicated that arsenic exposure resulted in increased anxiety, decreased locomotion, and cognitive impairments, which were associated with reduced ERα expression and lowered levels of BDNF and NMDAR 2B (N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subtype 2B) in hippocampal tissues. Notably, RES supplementation restored cognitive functions and reversed the downregulation of neurotrophins, suggesting its potential as a protective compound against arsenic toxicity [10].

Emerging biomarkers for early detection of arsenic toxicity

Beyond BDNF and NGF, additional biomarkers are being explored to detect early-stage arsenic-induced neurotoxicity. These include serum and CSF (Cerebrospinal fluid) levels of BDNF, which may serve as non-invasive indicators of neuronal stress [73]. Altered levels of NFL (Neurofilament light chain), S100β (S100 Calcium-binding protein beta), GFAP (Glial fibrillary acidic protein), and oxidative stress markers like 8-OHdG8 (Hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine) have also been observed in arsenic-exposed subjects. Integration of such biomarkers with miRNA profiles may offer a multiparametric approach for early diagnosis, disease monitoring, and therapeutic response prediction [74].

Fig. 5: Mechanisms of arsenic-induced neurotoxicity showing the disruption of neurotrophin signaling pathways. Arsenic exposure inhibits TrkB receptor activation, suppressing downstream pathways such as PI3K-AKT, RAS-MEK-ERK, and PLCγ-CaMK, ultimately leading to decreased CREB activation and BDNF transcription. This cascade of events contributes to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal apoptosis. PLCγ: phospholipase C gamma; CaMK: Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase; CREB: Cyclic AMP-Responsive Element-Binding Protein; PI3K-AKT: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase–Protein kinase; RAS-MEK-ERK: Rat sarcoma–Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase–Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

Therapeutic implications and future perspectives

Rationale for the development of small molecules targeting neurotrophin receptors

Neurotrophins have less-than-ideal pharmacological characteristics, such as low stability, probably low oral bioavailability, restricted penetration of the BBB (Blood-brain barrier), and restricted parenchymal diffusion in the CNS [75]. Adverse consequences are also more likely due to the extremely pleiotropic actions of neurotrophins, which are produced by activating their multi-receptor signaling complexes [76]. These effects include worsening of some types of brain damage and upregulation of pain transmission [77]. The lack of knowledge regarding the integration of neurotrophin signaling processes with underlying disease mechanisms presents another difficulty in the therapeutic use of neurotrophin proteins. There are three stages to consider when developing neurotrophin-based treatment approaches [78]. Neurotrophin proteins have been administered by a variety of peripheral and central nervous system pathways during "phase one" in the intervention of AD, ALS (Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), PD, diabetic neuropathy, and hereditary neuropathy [71]. Neurotrophins are thought to have protective effects against a range of critical mechanisms, including excitotoxicity, oxidative damage, and hypoxia-ischemia, and they may also aid in regeneration [79]. Neurotrophin proteins are delivered in the vicinity of specific neurons by gene therapy or cell transplant techniques in "phase two," which is a response to the hypothesis that lack of effectiveness is primarily caused by restricted bioavailability at target neurons. Many issues with administering neurotrophin proteins still exist, despite increasingly sophisticated delivery methods [80]. Targeting certain neurotrophin receptors with small molecule ligands that have advantageous medicinal qualities to either enhance beneficial activities or inhibit particular pathological pathways is known as "phase three" of neurotrophin-based therapeutic development [81]. One of the most promising small molecules under investigation is LM11A-31-a, a non-peptide ligand targeting the p75NTR (p75 neurotrophin receptor). Preclinical studies in AD models have shown that LM11A-31 can prevent synaptic loss, reduce tau phosphorylation, and improve cognitive performance, without activating pain pathways typically associated with NGF. This molecule successfully crossed the BBB and showed neuroprotective activity in both in vitro and in vivo settings. A Phase 2a clinical trial (NCT03069014) evaluating LM11A-31 in mild-to-moderate AD patients demonstrated favorable safety and tolerability, although cognitive endpoints showed modest benefits, suggesting further trials are needed to establish efficacy [82]. The p75NTR has become a particularly intriguing target for brain damage and degeneration. According to recent research, p75NTR expression is elevated in several clinical contexts and may be involved in controlling cell survival in neurodegenerative diseases, spinal cord injuries, and CNS axonal damage [80].

The therapeutic potential of neurotrophins is limited by poor BBB permeability and rapid enzymatic degradation. Recent advances in nanotechnology and exosome-based delivery systems offer promising solutions [83]. Nanoparticles conjugated with targeting ligands can deliver BDNF/NGF across the BBB with sustained release, while engineered exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells provide a biocompatible platform with low immunogenicity and high CNS targeting efficiency [84]. Hybrid strategies combining neurotrophins with antioxidants or miRNAs may further enhance therapeutic impact. However, these approaches require optimization of dose, targeting, and safety profiles in large-animal and human models [85].

Neuroprotection against Aβ-induced degeneration

Although reducing Aβ accumulation is a viable strategy for preventing AD neurodegeneration, new research suggests that reducing Aβ alone may not be enough therapy [86]. It has been shown that Aβ depletion in vitro is hazardous, and it may have vital physiological functions in controlling excitatory transmission and cognition [87]. Furthermore, Aβ-based treatments are unlikely to enhance the function or plasticity of damaged neurons and won't target the non-Aβ pathways that underlie the development of the illness [88]. While dual-target strategies aiming to reduce Aβ burden and enhance neurotrophin signaling appear synergistic in theory, the practicality is complex. For instance, Aβ-targeting therapies (e. g., aducanumab) reduce amyloid plaques but do not reverse synaptic damage, while neurotrophins like BDNF may restore synaptic function without reducing plaque load. Thus, combinatorial strategies must carefully balance timing, dosage, and patient selection [89]. Additionally, overexpression of neurotrophins or indiscriminate p75NTR modulation may lead to off-target effects, including altered pain sensitivity, unintended activation of pro-apoptotic pathways, or glial cell hyperactivation [90]. There are several ways in which small medicines that target p75NTR may alter the pathophysiological processes underlying AD. The RAGE receptor, which binds advanced glycation end products, cell surface APP, p75NTR, the α7nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, and BBP-1 (Branchpoint binding protein), a GPCR (G protein-coupled receptor). The distributional similarities between p75NTR and neurons that are susceptible to degeneration in AD, such as those in the entorhinal cortex, neocortex, hippocampus, and basal forebrain, indicate that p75NTR may mediate Aβ toxicity, making it an especially interesting target for preventing Aβ's harmful effects. On the other hand, p75NTR expression seems to be elevated in AD tissue in the entorhinal cortex, neocortex, and hippocampus, with neurons expressing more p75NTR seemingly being relatively immune to neurodegenerative features. Based on research showing that Aβ raises p75NTR levels in neuronal cultures and that downregulating p75NTR expression increases susceptibility to Aβ, it is plausible that Aβ may cause upregulation of p75NTR expression and that p75NTR signaling can promote protective signaling [91].

Neuroprotection against oxidative stress and excitotoxicity

Potential causes of AD and other neuropathological conditions for which neuroprotection is being sought include oxidative stress and excitotoxicity [92]. Degenerative signaling is triggered by oxidative stress, which also activates stress kinases like JNK [93]. It has been demonstrated that, depending on the model used, neurotrophins either prevent or enhance oxidative stress-induced mortality [94]. Responses to neurotrophins are determined by several factors, such as specific oxidative stress test settings and whether death happens by necrosis (which neurotrophins enhance) or apoptosis (which neurotrophins inhibit). Through the p75NTR connection, NGF has been demonstrated to stop cell death in an excitotoxicity paradigm [95].

Despite promising preclinical findings, translation to clinical success has been limited. For example, recombinant NGF in Phase I/II trials for peripheral neuropathy showed modest efficacy but significant adverse effects such as injection site pain and hyperalgesia [96]. Similarly, BDNF gene therapy has faced challenges related to vector safety, delivery precision, and immune activation. Small molecules like LM22A-4 (a TrkB agonist) have shown benefits in animal models of Rett syndrome and Huntington’s disease, but human trials are currently lacking [97].

Furthermore, off-target effects remain a key concern, particularly with p75NTR modulators, which can interact with signaling pathways like RhoA (Ras homolog family member A), JNK, and NF-κB (Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells), potentially causing pro-inflammatory or pro-apoptotic effects in non-neuronal tissues [98]. Therefore, targeted delivery systems and highly selective modulators are essential for minimizing systemic toxicity and optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Arsenic-induced neurotoxicity remains a serious global health concern, contributing to cognitive deficits, neurodevelopmental disorders, and neurodegeneration. Its pathological effects are primarily driven by oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, apoptosis, and impaired neurotransmission. However, arsenic disrupts Trk receptor activation, impairing essential pathways such as PI3K-Akt, RAS-MEK-ERK, and PLCγ-CaMK, which leads to reduced BDNF expression, increased oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis, accelerating neurodegeneration. Neurotrophins such as BDNF and NGF offer significant neuroprotective potential, but their therapeutic application faces challenges due to poor bioavailability and delivery barriers. Emerging approaches, including small-molecule mimetics and targeted delivery systems, hold promise. Future research should focus on optimizing these strategies and identifying early biomarkers to enable timely intervention and improve clinical outcomes.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Ayush Chaurasia and Zeeshan Ansari, P.G. research scholars, prepared the present article under the mentorship and supervision of Dr. Ajay Kumar Gupta, with co-mentorship provided by Dr. G. Hema and Dr. Anju Singh, who also contributed to the manuscript's editing and refinement.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Sharma A, Kumar S. Arsenic exposure with reference to neurological impairment: an overview. Rev Environ Health. 2019 Dec 18;34(4):403-14. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2019-0052, PMID 31603861.

Bhat A, Ravi K, Tian F, Singh B. Arsenic contamination needs serious attention: an opinion and global scenario. Pollutants. 2024 Apr 8;4(2):196-211. doi: 10.3390/pollutants4020013.

Desai S, Wilson J, Ji C, Sautner J, Prussia AJ, Demchuk E. The role of simulation science in public health at the agency for toxic substances and disease registry: an overview and analysis of the last decade. Toxics. 2024 Nov 12;12(11):811. doi: 10.3390/toxics12110811, PMID 39590991.

Hassan Z, Westerhoff HV. Arsenic contamination of groundwater is determined by complex interactions between various chemical and biological processes. Toxics. 2024 Jan 19;12(1):89. doi: 10.3390/toxics12010089, PMID 38276724.

Ganie SY, Javaid D, Hajam YA, Reshi MS. Arsenic toxicity: sources pathophysiology and mechanism. Toxicol Res (Camb). 2024 Jan 1;13(1):tfad111. doi: 10.1093/toxres/tfad111, PMID 38178998.

Begni V, Riva MA, Cattaneo A. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor in physiological and pathological conditions. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017 Jan 1;131(2):123-38. doi: 10.1042/CS20160009, PMID 28011898.

Franco ML, Comaposada Baro R, Vilar M. Neurotrophins and neurotrophin receptors. In: Hormonal signaling in biology and medicine. Elsevier; 2020. p. 83-106. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-813814-4.00005-5.

Pae CU, Marks DM, Han C, Patkar AA, Steffens D. Does neurotropin-3 have a therapeutic implication in major depression? Int J Neurosci. 2008 Jan 7;118(11):1515-22. doi: 10.1080/00207450802174589, PMID 18853330.

Zhang W, Li Z, Lan W, Guo H, Chen F, Wang F. Bioengineered silkworm model for expressing human neurotrophin-4 with potential biomedical application. Front Physiol. 2022;13:1104929. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.1104929, PMID 36685209.

Mehta K, Pandey KK, Kaur B, Dhar P, Kaler S. Resveratrol attenuates arsenic induced cognitive deficits via modulation of estrogen-NMDAR-BDNF signalling pathway in female mouse hippocampus. Psychopharmacol (Berl). 2021 Sep 28;238(9):2485-502. doi: 10.1007/s00213-021-05871-2, PMID 34050381.

Islam K, Wang QQ, Naranmandura H. Molecular mechanisms of arsenic toxicity; 2015. p. 77-107.

Karim Y, Siddique AE, Hossen F, Rahman M, Mondal V, Banna HU. Dose-dependent relationships between chronic arsenic exposure and cognitive impairment and serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Environ Int. 2019 Oct;131:105029. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105029, PMID 31352261.

Vahter M, Concha G. Role of metabolism in arsenic toxicity. Pharmacol toxicol. 2001 Jul;89(1):1-5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2001.d01-128.x, PMID 11484904.

Flora SJ. Arsenic. In: Handbook of arsenic toxicology. Elsevier; 2015. p. 1-49. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-418688-0.00001-0.

Frisbie SH, Mitchell EJ. Arsenic in drinking water: an analysis of global drinking water regulations and recommendations for updates to protect public health. PLOS One. 2022 Apr 6;17(4):e0263505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263505, PMID 35385526.

Yadav RS, Shukla RK, Sankhwar ML, Patel DK, Ansari RW, Pant AB. Neuroprotective effect of curcumin in arsenic-induced neurotoxicity in rats. Neurotoxicology. 2010 Sep;31(5):533-9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2010.05.001, PMID 20466022.

Garza Lombo C, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI, Gonsebatt ME, Franco R. Arsenic induced neurotoxicity: a mechanistic appraisal. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2019 Dec 21;24(8):1305-16. doi: 10.1007/s00775-019-01740-8, PMID 31748979.

Grozio A, Sociali G, Sturla L, Caffa I, Soncini D, Salis A. CD73 protein as a source of extracellular precursors for sustained NAD+biosynthesis in FK866-treated tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2013 Sep;288(36):25938-49. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.470435, PMID 23880765.

Mukherjee SC, Rahman MM, Chowdhury UK, Sengupta MK, Lodh D, Chanda CR. Neuropathy in arsenic toxicity from groundwater arsenic contamination in West Bengal, India. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 2003 Mar;38(1):165-83. doi: 10.1081/ese-120016887, PMID 12635825.

Kaushal P, Kumar P, Dhar P. Ameliorative role of antioxidant supplementation on sodium arsenite-induced adverse effects on the developing rat cerebellum. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2020 Oct;11(4):455-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2018.02.138, PMID 30635247.

Jiang S, Su J, Yao S, Zhang Y, Cao F, Wang F. Fluoride and arsenic exposure impairs learning and memory and decreases mGluR5 expression in the hippocampus and cortex in rats. PLOS One. 2014 Apr 23;9(4):e96041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096041, PMID 24759735.

Kannan GM, Tripathi N, Dube SN, Gupta M, Flora SJ. Toxic effects of arsenic (III) on some hematopoietic and central nervous system variables in rats and guinea pigs. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2001 Jan 31;39(7):675-82. doi: 10.1081/clt-100108508, PMID 11778665.

Ali N, Hoque MA, Haque A, Salam KA, Karim MR, Rahman A. Association between arsenic exposure and plasma cholinesterase activity: a population based study in Bangladesh. Environ Health. 2010 Dec 10;9(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-9-36, PMID 20618979.

Paul S, Das N, Bhattacharjee P, Banerjee M, Das JK, Sarma N. Arsenic induced toxicity and carcinogenicity: a two wave cross sectional study in arsenicosis individuals in West Bengal, India. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2013 Mar 19;23(2):156-62. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.91, PMID 22990472.

Chatterjee D, Bandyopadhyay A, Sarma N, Basu S, Roychowdhury T, Roy SS. Role of microRNAs in senescence and its contribution to peripheral neuropathy in the arsenic-exposed population of West Bengal, India. Environ Pollut. 2018 Feb;233:596-603. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.09.063, PMID 29107899.

Mochizuki H, Phyu KP, Aung MN, Zin PW, Yano Y, Myint MZ. Peripheral neuropathy induced by drinking water contaminated with low-dose arsenic in Myanmar. Environ Health Prev Med. 2019 Dec 23;24(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12199-019-0781-0, PMID 31014238.

Parvez F, Wasserman GA, Factor Litvak P, Liu X, Slavkovich V, Siddique AB. Arsenic exposure and motor function among children in Bangladesh. Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Nov;119(11):1665-70. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103548, PMID 21742576.

Rosado JL, Ronquillo D, Kordas K, Rojas O, Alatorre J, Lopez P. Arsenic exposure and cognitive performance in Mexican schoolchildren. Environ Health Perspect. 2007 Sep;115(9):1371-5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9961, PMID 17805430.

Wasserman GA, Liu X, LoIacono NJ, Kline J, Factor Litvak P, Van Geen A. A cross sectional study of well water arsenic and child IQ in Maine schoolchildren. Environ Health. 2014 Dec 1;13(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-13-23, PMID 24684736.

Nino SA, Martel Gallegos G, Castro Zavala A, Ortega Berlanga B, Delgado JM, Hernandez Mendoza H. Chronic arsenic exposure increases Aβ (1−42) production and receptor for advanced glycation end products expression in rat brain. Chem Res Toxicol. 2018 Jan 16;31(1):13-21. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.7b00215, PMID 29155576.

Tam LM, Wang Y. Arsenic exposure and compromised protein quality control. Chem Res Toxicol. 2020 Jul 20;33(7):1594-604. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00107, PMID 32410444.

Nino SA, Chi Ahumada E, Ortiz J, Zarazua S, Concha L, Jimenez Capdeville ME. Demyelination associated with chronic arsenic exposure in Wistar rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2020 Apr;393:114955. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2020.114955, PMID 32171569.

Ramos Chavez LA, Rendon Lopez CRR, Zepeda A, Silva Adaya D, Del Razo LM, Gonsebatt ME. Neurological effects of inorganic arsenic exposure: altered cysteine/glutamate transport, NMDA expression and spatial memory impairment. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015 Feb 9;9:21. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00021.

Nelson Mora J, Escobar ML, Rodriguez Duran L, Massieu L, Montiel T, Rodriguez VM. Gestational exposure to inorganic arsenic (iAs3+) alters glutamate disposition in the mouse hippocampus and ionotropic glutamate receptor expression leading to memory impairment. Arch Toxicol. 2018 Mar 4;92(3):1037-48. doi: 10.1007/s00204-017-2111-x, PMID 29204679.

Sung K, Kim M, Kim H, Hwang GW, Kim K. Perinatal exposure to arsenic in drinking water alters glutamatergic neurotransmission in the striatum of C57BL/6 mice. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2019 Jan 10;187(1):224-9. doi: 10.1007/s12011-018-1374-2, PMID 29748927.

Cholanians AB, Phan AV, Ditzel EJ, Camenisch TD, Lau SS, Monks TJ. From the cover: arsenic induces accumulation of α-synuclein: implications for synucleinopathies and neurodegeneration. Toxicol Sci. 2016 Oct;153(2):271-81. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw117, PMID 27413109.

Lu TH, Su CC, Chen YW, Yang CY, Wu CC, Hung DZ. Arsenic induces pancreatic β-cell apoptosis via the oxidative stress-regulated mitochondria-dependent and endoplasmic reticulum stress-triggered signaling pathways. Toxicol Lett. 2011 Feb 25;201(1):15-26. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.11.019, PMID 21145380.

Sides TR, Nelson JC, Nwachukwu KN, Boston J, Marshall SA. The influence of arsenic co-exposure in a model of alcohol induced neurodegeneration in C57BL/6J mice. Brain Sci. 2023 Nov 24;13(12):1633. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13121633, PMID 38137081.

Corsini E, Asti L, Viviani B, Marinovich M, Galli CL. Sodium arsenate induces overproduction of interleukin-1α in murine keratinocytes: role of mitochondria. J Invest Dermatol. 1999 Nov;113(5):760-5. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00748.x, PMID 10571731.

Hendry J, Fraser S, White J, Rajan P, Hendry DS. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) for malignant phenotype leydig cell tumours of the testis: a 10 y experience. Springerplus. 2015;41:20. doi: 10.1186/s40064-014-0781-x, PMID 25625040.

Butterfield DA, Castegna A, Lauderback CM, Drake J. Evidence that amyloid beta-peptide induced lipid peroxidation and its sequelae in Alzheimer’s disease brain contribute to neuronal death1. Neurobiol Aging. 2002 Sep;23(5):655-64. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00340-2, PMID 12392766.

An Y, Liu T, Liu X, Zhao L, Wang J. Rac1 and Cdc42 play important roles in arsenic neurotoxicity in primary cultured rat cerebellar astrocytes. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016 Mar 2;170(1):173-82. doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0456-7, PMID 26231544.

Mount CW, Monje M. Wrapped to adapt: experience-dependent myelination. Neuron. 2017 Aug;95(4):743-56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.009, PMID 28817797.

Bustaffa E, Stoccoro A, Bianchi F, Migliore L. Genotoxic and epigenetic mechanisms in arsenic carcinogenicity. Arch Toxicol. 2014 May 2;88(5):1043-67. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1233-7, PMID 24691704.

Frost GR, Li YM. The role of astrocytes in amyloid production and Alzheimer’s disease. Open Biol. 2017 Dec 13;7(12):170228. doi: 10.1098/rsob.170228, PMID 29237809.

Firdaus F, Zafeer MF, Waseem M, Ullah R, Ahmad M, Afzal M. Thymoquinone alleviates arsenic-induced hippocampal toxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction by modulating mPTP in Wistar rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018 Jun;102:1152-60. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.159, PMID 29710533.

Vazquez Cervantes GI, Gonzalez Esquivel DF, Ramirez Ortega D, Blanco Ayala T, Ramos Chavez LA, Lopez Lopez HE. Mechanisms associated with cognitive and behavioral impairment induced by arsenic exposure. Cells. 2023 Oct 28;12(21):2537. doi: 10.3390/cells12212537, PMID 37947615.

Mao J, Yang J, Zhang Y, Li T, Wang C, Xu L. Arsenic trioxide mediates HAPI microglia inflammatory response and subsequent neuron apoptosis through p38/JNK MAPK/STAT3 pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2016 Jul;303:79-89. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2016.05.003, PMID 27174766.

Saha S, Sadhukhan P, Mahalanobish S, Dutta S, Sil PC. Ameliorative role of genistein against age-dependent chronic arsenic toxicity in murine brains via the regulation of oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling cascades. J Nutr Biochem. 2018 May;55:26-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.11.010, PMID 29331881.

Loos B, Cogill S, Mangali A. Establishing a risk profile for metal neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration in key South African mining: a local water quality assessment report to the water research commission; 2023.

Cheng H, Yang B, Ke T, Li S, Yang X, Aschner M. Mechanisms of metal-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in neurological disorders. Toxics. 2021 Jun 17;9(6):142. doi: 10.3390/toxics9060142, PMID 34204190.

Hussain F, Warraich UE, Jamil A. Redox signalling autophagy and ageing; 2022. p. 117-45.

Sun Q, Li Y, Shi L, Hussain R, Mehmood K, Tang Z. Heavy metals induced mitochondrial dysfunction in animals: molecular mechanism of toxicity. Toxicology. 2022 Mar;469:153136. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2022.153136, PMID 35202761.

Thakur M, Rachamalla M, Niyogi S, Datusalia AK, Flora SJ. Molecular mechanism of arsenic-induced neurotoxicity, including neuronal dysfunctions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Sep 17;22(18):10077. doi: 10.3390/ijms221810077, PMID 34576240.

Sadiku OO, Rodriguez Seijo A. Metabolic and genetic derangement: a review of mechanisms involved in arsenic and lead toxicity and genotoxicity. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2022 Dec 30;73(4):244-55. doi: 10.2478/aiht-2022-73-3669, PMID 36607725.

Shahid ul Islam, editor. Advanced materials for wastewater treatment. John Wiley & Sons; 2017.

Tripathi S, Fhatima S, Parmar D, Singh DP, Mishra S, Mishra R. Therapeutic effects of coenzymeq10, biochanin A and Phloretin against arsenic and chromium induced oxidative stress in mouse (Mus musculus) brain. 3 Biotech. 2022 May 21;12(5):116. doi: 10.1007/s13205-022-03171-w, PMID 35547012.

Kushwaha S, Saji J, Verma R, Singh V, Ansari JA, Mishra SK. Microglial neuroinflammation independent reversal of demyelination of corpus callosum by arsenic in a cuprizone induced demyelinating mouse model. Mol Neurobiol. 2024 Sep 14;61(9):6822-41. doi: 10.1007/s12035-024-03978-z, PMID 38353925.

Khan H, Bangar A, Grewal AK, Bansal P, Singh TG. Caspase-mediated regulation of the distinct signaling pathways and mechanisms in neuronal survival. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022 Sep;110:108951. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108951, PMID 35717837.

Roy S, Narzary B, Ray A, Bordoloi M. Arsenic-induced instrumental genes of apoptotic signal amplification in death survival interplay. Cell Death Discov. 2016 Oct 17;2(1):16078. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2016.78, PMID 27785370.

Chen J, Jin Z, Zhang S, Zhang X, Li P, Yang H. Arsenic trioxide elicits prophylactic and therapeutic immune responses against solid tumors by inducing necroptosis and ferroptosis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023;20(1):51-64. doi: 10.1038/s41423-022-00956-0, PMID 36447031.

Ghosh J, Sil PC. Mechanism for arsenic-induced toxic effects. In: Handbook of arsenic toxicology. Elsevier; 2023. p. 223-52. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-89847-8.00022-5.

Ghosh S, Dungdung SR, Chowdhury ST, Mandal AK, Sarkar S, Ghosh D. Encapsulation of the flavonoid quercetin with an arsenic chelator into nanocapsules enables the simultaneous delivery of hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs with a synergistic effect against chronic arsenic accumulation and oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011 Nov;51(10):1893-902. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.019, PMID 21914470.

Gibson GE, Chen HL, Xu H, Qiu L, Xu Z, Denton TT. Deficits in the mitochondrial enzyme α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase lead to Alzheimer’s disease-like calcium dysregulation. Neurobiol Aging. 2012 Jun;33(6):1121.e13-24. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.11.003, PMID 22169199.

Monisha A, Bhuvaneshwari S, Velarul S, Sathiya Vinotha A, Umamageswari MS, Vijayamathy A, Karthikeyan TM. Acute toxicity study of arsenicum album in Wistar albino rats. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2024 Dec 1:16(12):37-41. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2024v16i12.52513.

Du X, Tian M, Wang X, Zhang J, Huang Q, Liu L. Cortex and hippocampus DNA epigenetic response to a long-term arsenic exposure via drinking water. Environ Pollut. 2018 Mar;234:590-600. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.11.083, PMID 29223816.

Tyler CR, Labrecque MT, Solomon ER, Guo X, Allan AM. Prenatal arsenic exposure alters REST/NRSF and microRNA regulators of embryonic neural stem cell fate in a sex dependent manner. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2017 Jan;59:1-15. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2016.10.004, PMID 27751817.

Silakarma D, Sudewi AA. The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in cognitive functions. Bali Med J. 2019 Aug 1;8(2):518-25. doi: 10.15562/bmj.v8i2.1460.

Ali NH, Al Kuraishy HM, Al Gareeb AI, Alexiou A, Papadakis M, AlAseeri AA. BDNF/TrkB activators in Parkinson’s disease: a new therapeutic strategy. J Cell Mol Med. 2024 May 16;28(10):e18368. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.18368, PMID 38752280.

Pandey R, Garg A, Gupta K, Shukla P, Mandrah K, Roy S. Arsenic induces differential neurotoxicity in male female and E2-deficient females: comparative effects on hippocampal neurons and cognition in adult rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2022 May 17;59(5):2729-44. doi: 10.1007/s12035-022-02770-1, PMID 35175559.

Mansoor S, Jindal A, Badu NY, Katiki C, Ponnapalli VJ, Desai KJ. Role of neurotrophins in the development and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: a systematic review. Cureus. 2024 Nov 19;16(11):e74048. doi: 10.7759/cureus.74048, PMID 39712854.

Hui L, Yuan J, Ren Z, Jiang X. Brief Communication nerve growth factor reduces apoptotic cell death in rat facial motor neurons after facial nerve injury. Neurosciences. 2015 Jan;20(1):65–8. PMID 25630785.

Segaran RC, Chan LY, Wang H, Sethi G, Tang FR. Neuronal development-related miRNAs as biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease depression schizophrenia and ionizing radiation exposure. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28(1):19-52. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666200121122910, PMID 31965936.

Maciejska A, Skorkowska A, Jurczyk J, Pomierny B, Budziszewska B. Biomarkers of neurotoxicity. Biomarkers in Toxicology. 2022. p. 1-30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-87225-0_17-1.

Bahlakeh G, Rahbarghazi R, Mohammadnejad D, Abedelahi A, Karimipour M. Current knowledge and challenges associated with targeted delivery of neurotrophic factors into the central nervous system: focus on available approaches. Cell Biosci. 2021 Oct 12;11(1):181. doi: 10.1186/s13578-021-00694-2, PMID 34641969.

Xu M, Niu Q, Hu Y, Feng G, Wang H, Li S. Proanthocyanidins antagonize arsenic induced oxidative damage and promote arsenic methylation through activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:8549035. doi: 10.1155/2019/8549035, PMID 30805085.

Liang C, Wu X, Huang K, Yan S, Li Z, Xia X. Domain and sex specific effects of prenatal exposure to low levels of arsenic on children’s development at 6 m of age: findings from the Ma’anshan birth cohort study in China. Environ Int. 2020 Feb;135:105112. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105112, PMID 31881426.

Weissmiller AM, Wu C. Current advances in using neurotrophic factors to treat neurodegenerative disorders. Transl Neurodegener. 2012 Dec 26;1(1):14. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-1-14, PMID 23210531.

Nordvall G, Forsell P, Sandin J. Neurotrophin targeted therapeutics: a gateway to cognition and more? Drug Discov Today. 2022 Oct;27(10):103318. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2022.07.003, PMID 35850433.

Bahlakeh G, Rahbarghazi R, Mohammadnejad D, Abedelahi A, Karimipour M. Current knowledge and challenges associated with targeted delivery of neurotrophic factors into the central nervous system: focus on available approaches. Cell Biosci. 2021 Oct 12;11(1):181. doi: 10.1186/s13578-021-00694-2, PMID 34641969.

Mansoor S, Jindal A, Badu NY, Katiki C, Ponnapalli VJ, Desai KJ. Role of neurotrophins in the development and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: a systematic review. Cureus. 2024 Nov 19;16(11):e74048. doi: 10.7759/cureus.74048, PMID 39712854.

Shanks HR, Chen K, Reiman EM, Blennow K, Cummings JL, Massa SM. p75 neurotrophin receptor modulation in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: a randomized placebo-controlled phase 2a trial. Nat Med. 2024 Jun 17;30(6):1761-70. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-02977-w, PMID 38760589.

Yadav K, Vijayalakshmi R, Kumar Sahu K, Sure P, Chahal K, Yadav R. Exosome based macromolecular neurotherapeutic drug delivery approaches in overcoming the blood-brain barrier for treating brain disorders. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2024 Jun;199:114298. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2024.114298, PMID 38642716.

Yang YP, Nicol CJ, Chiang MC. A review of the neuroprotective properties of exosomes derived from stem cells and exosome coated nanoparticles for treating neurodegenerative diseases and stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 Apr 21;26(8):3915. doi: 10.3390/ijms26083915, PMID 40332773.

Abdolahi S, Zare Chahoki A, Noorbakhsh F, Gorji A. A review of molecular interplay between neurotrophins and miRNAs in neuropsychological disorders. Mol Neurobiol. 2022 Oct 2;59(10):6260-80. doi: 10.1007/s12035-022-02966-5, PMID 35916975.

Li J, Liao W, Huang D, Ou M, Chen T, Wang X. Current strategies of detecting Aβ species and inhibiting Aβ aggregation: status and prospects. Coord Chem Rev. 2023 Nov;495:215375. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215375.

Tzioras M, McGeachan RI, Durrant CS, Spires Jones TL. Synaptic degeneration in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2023 Jan 13;19(1):19-38. doi: 10.1038/s41582-022-00749-z, PMID 36513730.

Baazaoui N, Iqbal K. Alzheimer’s disease: challenges and a therapeutic opportunity to treat it with a neurotrophic compound. Biomolecules. 2022 Oct 2;12(10):1409. doi: 10.3390/biom12101409, PMID 36291618.

Gao L, Zhang Y, Sterling K, Song W. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in Alzheimer’s disease and its pharmaceutical potential. Transl Neurodegener. 2022 Jan 28;11(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40035-022-00279-0, PMID 35090576.

Mocchetti I, Speidell A. Neurotrophins: decades of discoveries. In: Gendelman HE, Ikezu T, editors. Neuroimmune pharmacology and therapeutics. Berlin: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 283-98. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-68237-7_17.

Ni R, Marutle A, Nordberg A. Modulation of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and fibrillar amyloid-β interactions in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013 Jan 10;33(3):841-51. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121447, PMID 23042213.

Ellinsworth DC. Arsenic reactive oxygen and endothelial dysfunction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015 Jun;353(3):458-64. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.223289, PMID 25788710.

Stern M, Mc New JA. A transition to degeneration triggered by oxidative stress in degenerative disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2021 Mar 6;26(3):736-46. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00943-9, PMID 33159186.

Benfato ID, Quintanilha AC, Henrique JS, Souza MA, Dos Anjos Rosario B, Beserra Filho JI. Long-term calorie restriction prevented memory impairment in middle-aged male mice and increased a marker of DNA oxidative stress in hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2024 Mar;209:107902. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2024.107902, PMID 38336097.

Turkistani A, Al kuraishy HM, Al Gareeb AI, Albuhadily AK, Elhussieny O, AL Farga A, Aqlan F, Saad HM, Batiha GES. The functional and molecular roles of p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75 NTR) in epilepsy. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2024 Dec 22;16. doi: 10.1177/11795735241247810.

Sorensen LB, Gazerani P, Sluka KA, Graven Nielsen T. Repeated injections of low-dose nerve growth factor (NGF) in healthy humans maintain muscle pain and facilitate ischemic contraction-evoked pain. Pain Med. 2020 Dec 25;21(12):3488-98. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa315, PMID 33111942.

Li W, Bellot Saez A, Phillips ML, Yang T, Longo FM, Pozzo Miller L. A small molecule TrkB ligand restores hippocampal synaptic plasticity and object location memory in rett syndrome mice. Dis Model Mech. 2017 Jul 1;10(7):837-45. doi: 10.1242/dmm.029959, PMID 28679669.

Li Q, Hu YZ, Gao S, Wang PF, Hu ZL, Dai RP. ProBDNF and its receptors in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: novel insights into the regulation of metabolism and mitochondria. Front Immunol. 2023 Apr 18;14:1155333. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1155333, PMID 37143663.