Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 391-405Original Article

GREEN SYNTHESIS OF SPIRULINA OIL-BASED NANOVESICLES AS A BIOENHANCER FOR THE INTRANASAL BRAIN TARGETING OF STATINS: CELL LINE STUDY ON HUMAN BRAIN CANCER CELL SNB-75 AND PHARMACOKINETICS ON RATS

MAHMOUD ELTAHAN1*, DOHA H. ABOU BAKER2, HEBA S. ABBAS3,4, REHAB ABDELMONEM1, MOHAMED EL-NABARAWI5, ALSHAIMAA ATTIA1

1Department of Industrial Pharmacy, College of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Drug Manufacturing, Misr University for Science and Technology, 6th October City, Egypt. 2Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Department, Pharmaceutical and Drug Industries Institute, National Research Center, Cairo, Egypt. 3Department of Microbiology and Immunology, College of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Drug Manufacturing, Misr University for Science and Technology, 6th October City, Egypt. 4Egyptian Drug Authority, previously, National Organization of Drug Control and Research, Giza, Egypt. 5Department of Pharmaceutics and Industrial Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt

*Corresponding author: Mahmoud Eltahan; *Email: mahmoud.eltahan@must.edu.eg

Received: 25 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 14 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study presents a novel glioma treatment strategy using intranasally administered statin-loaded Spirusomes, integrating Spirulina oil as a bioenhancer to potentiate statins’ anticancer effects, optimize bioavailability, and minimize systemic exposure.

Methods: Eight atorvastatin-loaded Spirusome formulae were prepared and assessed concerning vesicle size, charge, entrapment efficiency, and in vitro release profile. F1, containing 10 mg of atorvastatin, 100 mg of lecithin, and 1 mg of Spirulina oil, achieved a desirability score of 0.859 based on Design Expert® analysis. Raman spectroscopy was used to test for any possible drug interactions. In vitro cytotoxicity studies on SNB-75 human brain cancer cells were carried out to evaluate the anticancer efficacy of the optimized Spirusomes. In vivo pharmacokinetic studies on albino rats were used to examine the drug’s pharmacokinetic profile in plasma and brain tissues after intranasal and oral administration.

Results: The optimized formula (F1) achieved nearly complete drug release within 24 h, with no drug interactions confirmed via Raman spectroscopy. In vitro cytotoxicity studies showed an IC50 of 39.48±2.01 µg/ml for atorvastatin-loaded Spirusomes, which was lower than that for plain atorvastatin. In vivo pharmacokinetics revealed a 7-fold increase in brain bioavailability (AUC0-24 = 4660.685±216.849 ng. h/gm), indicating enhanced selectivity following intranasal administration.

Conclusion: This investigation reveals that atorvastatin-loaded Spirusomes might serve as an effective and selective delivery system for brain cancer treatment. The optimized formula demonstrated excellent physicochemical properties, efficient drug release, potent anticancer activity, and promising pharmacokinetics, indicating substantial preclinical potential as a brain-targeted drug delivery system. However, further studies employing glioma-bearing animal models are necessary to evaluate therapeutic efficacy and validate these findings in a disease-relevant context.

Keywords: Spirusomes, Atorvastatin calcium, Pharmacokinetics, Cytotoxicity, Glioma, Spirulina oil

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54735 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Brain cancer (glioma) remains a global health challenge and the most fatal disease, with limited therapeutic options available [1]. According to Alrosan et al., tumor cell proliferation is correlated with the increased demand for cholesterol. Modulating metabolic pathways involved in cholesterol metabolism is a new concept in treating brain tumors. Thus, the suppression of cholesterol biosynthesis would inhibit the growth of glioma tumors and could be a therapeutic strategy for gliomas or other forms of brain cancers [2].

Statins, as lipid-lowering agents, inhibit 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl CoA reductases, which are the rate-limiting enzymes of cholesterol synthesis. Thus, targeting cholesterol synthesis, statin therapy may be able to inhibit the growth of glioma tumors and may become one of the therapeutic approaches used against glioma or other forms of brain cancers [3]. Moreover, statins seem to exhibit pleiotropic effects, such as influencing cell growth and apoptosis [4]. By modulating these pathways, statins can potentially impact various disease processes, including cancer [5].

Among the various statins available, Atorvastatin was selected for this study due to its favorable pharmacodynamic properties and existing evidence of anticancer potential in glioma models [6]. Also, Atorvastatin is a synthetic, poorly water-soluble statin [7]. However, its therapeutic uses have been limited because of its low aqueous solubility (0.1 mg/ml) and poor oral bioavailability [8]. Our attempt to improve its bioavailability and brain targeting comprises the delivery of the drug using a nasal nanovesicular delivery system.

While various nano-vesicular systems have been explored for drug delivery, this study pioneers the use of Spirulina-oil-modified emulsomes (Spirusomes) to create a dual-function delivery system. Unlike conventional vesicular systems, Spirusomes leverage the bioactive properties of Spirulina oil for enhanced cellular uptake and glioma-targeting efficiency.

Emulsomes, which resemble green-synthesized Spirusomes, consist of a solid fat core wrapped by a phospholipid bilayer integrated with cholesterol [9, 10]. It can encapsulate poorly water-soluble drugs in its solid fat core [11, 12], and it can be used as an ideal carrier for enabling the prolonged release of active molecules while dosing frequencies and associated costs are reduced [13]. Other essential advantages of emulsomes include the possibility to target therapeutic agents precisely to particular tissues and organs, thus considerably minimizing systemic side effects and reducing the required dose [14, 15].

The specific targeting of active pharmaceutical agents can be achieved using opsonins, which are circulating serum factors that enhance the uptake of emulsome vesicles. Targeting via this method is applied to neoplastic lesions and different infectious pathologies with reduced adverse effects [16].

The cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis has been used in the therapy of various medical conditions related to its pharmacological properties, which include strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities [17, 18]. In different studies, it was shown that Spirulina oil exhibited a lack of cytotoxicity toward healthy cells for the entire range of concentrations tested (10 – 1000 μg/ml) [19]. Moreover, it can modulate the host’s immune responses in addition to harboring anticancer activities [20].

Therefore, the presence of this oil in the developed nano-form could synergize the effect of statins against brain cancer with no toxic side effects and a highly safe profile. Thus, the formulated nanoparticles, Spirulina oil-modified emulsomes (Spirusomes), are designed for use as a potential approach to enhancing the anticancer activity of the statins.

The intranasal route of administration is a non-invasive method that delivers drugs directly through the nasal cavity, offering a promising approach for targeting brain tissues [21]. This method, through exploiting the unique features of nasal anatomy, will open a direct gateway to the CNS via olfactory and trigeminal neural pathways. This ability to bypass the BBB is of special importance, as this barrier often limits the effectiveness of drugs administered systemically to the brain [22]. The olfactory nerve serves as a key route for this method, allowing the efficient and direct transport of substances to brain tissue with high permeability, reducing systemic side effects, and enabling lower dosing. This delivery method is especially beneficial for treating neurological disorders, brain cancers, and other CNS diseases, where targeted and efficient drug delivery is crucial.

Therefore, the aim of this research study is to introduce intranasally Atorvastatin-loaded Spirulina oil-based nanovesicles (hereafter referred to as Spirusomes) as a potential application in glioma treatment in order to improve the anticancer effects of the drug for treating different types of brain tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Atorvastatin calcium was gifted from EIPICO Ltd Co. (Egypt). Compritol® 888 was a gift sample from Gattefosse Co. (Lyon, France). Lecithin was obtained from Lipoid GmbH (Ludwigshafen, Germany). SNB-75 human brain cancer cells were supplied by the Naval American Research Unit—Egypt (NAmRU). The MTT [3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] cell viability kit and cholesterol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (USA). Spirulina powder was obtained from a national research institution in Egypt. All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Methods

Spirulina oil preparation

Spirulina powder was sourced from a national research institution in Egypt. Using n-hexane, the total S. platensis lipid was extracted. In particular, 100g of the dry ground sample was loaded into an extraction thimble and exposed to 100 ml of the solvent combination for a 4 h Soxhlet extraction. A vacuum rotary evaporator (Laborota 4010 Digital, Heidolph, Schwabach, Germany) was then used to evaporate the solvent. Gravimetric analysis was used to assess the total lipid content [23, 24].

GC-MS analysis

Using a DBWAXtre capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm; Agilent) and an Agilent 7820A GC System connected to a single quadrupole selective mass detector (Agilent 5977E MSD in electron ionization (EI) mode (70 eV)) under temperature gradient elution, the chromatographic technique was adjusted. A 50:1 split ratio was used to inject 1 μl of the sample into helium, the gas carrier, which had a flow rate of 1 ml min−1.

There were four temperatures used: 250 °C for the MS source, 150 °C for the MS quad, 250 °C for the AUX 1, and 250 °C for the intake F. MS scanning was carried out between 45 and 650 Da every 0.5 sec. Starting at 45 °C, the GC oven temperature program increased to 165 °C at a rate of 5 °C min−1 and was held for 15 min. Next, the temperature was raised to 215 °C at a rate of 3 °C min−1 and held for 16 min. In the end, the temperature was raised to 260 °C at a rate of 10 °C per minute and held for two minutes. In total, 78.17 min was the entire run time.

Data was obtained using Mass Hunter GC/MS Acquisition B.07.00, 2013; processing was carried out using Mass Hunter Workstation Software Qualitative Analysis B.06.00, 2012; comparisons and identifications were performed using the Sulpeco 37 component FAME Mix reference standard and the NIST Mass Spectral Search Program, 2012.

Experimental design

A two-level regular factorial design, specifically a 23 configuration, was used via the Design-Expert®13 software (Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) for the formulation and optimization of Spirusomes. As indicated in , three independent variables were studied: the quantity of phosphatidyl choline (PC), the quantity of Spirulina oil, and the hydration media type. A series of dependent responses were studied, including Spirusomes vesicle size, zeta potential, polydispersity index (PDI), atorvastatin entrapment efficiency (EE%), and percent released after 24 h. The data obtained from these responses were analyzed via analysis of variance (ANOVA) at a significant level of 95% (P<0.05). To visualize the inter-relationships of the variables under study, 2D and 3D plots were constructed [25].

Table 1: Independent variables and responses used in the factorial design for the formulation and optimization of spirusomes

| Factors | Factor type | Low actual | High actual |

| X1: PC amount X2: Spirulina oil amount X3: Hydration medium type |

Numeric Numeric Categoric |

100 100 Dist. water |

200 200 Dist. water: ethanol |

| Responses | Desirability constraints | ||

| Y1: Particle size | Minimize | ||

| Y2: Zeta potential (absolute values) | Maximize | ||

| Y3: PDI | Minimize | ||

| Y4: EE % | Maximize | ||

| Y5: In vitro release % (24 h) | Maximize |

*PC: Phosphatidyl choline; PDI: poly dispersibility index; EE%: entrapment efficiency percentage.

Formulation of spirusomes

A systematic optimization process was applied to develop Spirusomes using the thin-film hydration technique outlined by Kamel et al. [26], with minor adjustments tailored to our laboratory setup, incorporating Design Expert® software to ensure precise control over physicochemical parameters. To summarize, Compritol (2% w/v), cholesterol (4% w/v), PC, and Spirulina oil with atorvastatin (1 mg/ml) were dissolved in a mixture of chloroform and methanol (2:1 %v/v), as detailed in .

The selected ranges for phosphatidylcholine (100–200 mg) and Spirulina oil (100–200 μg/ml) were based on preliminary optimization trials, which demonstrated stable vesicle formation, nanoscale particle size, and high drug entrapment within these levels. The hydration medium (distilled water vs. water–ethanol mixture) was included as a categorical factor to assess its influence on vesicle characteristics. These factor ranges are also in line with previous emulsome and lipid nanocarrier studies reported in the literature [16, 26-28].

Following this, solvents were evaporated using a Rota Vap (Eyela rotavapor, USA) at 60 °C and a speed of 120 rpm for 60 min. The formed thin film was hydrated using different media. F1 to F4 were hydrated using distilled water, and F5 to F8 were hydrated using a 2:1 %v/v water to ethanol mixture. Then, the samples were allowed to rotate for 1 h. Subsequently, ELMA-sonic ultrasonic S 100 H sonication (ELMA Corp., Germany) at 40% frequency was employed for 15 min to homogenize the mixture and obtain Spirusomes in the nano-size range.

Table 2: Composition of spirusomes prepared via the thin-film hydration method

| Formula | PC Amount (mg) | Spirulina oil (μg/ml) | Cholesterol (%w/v) |

Compritol (%w/v) |

Hydration media | |

| Dist. water (ml) | Ethanol (ml) | |||||

| F1 | 100 | 100 | 4 | 2 | 10 | - |

| F2 | 200 | 100 | 4 | 2 | 10 | - |

| F3 | 100 | 200 | 4 | 2 | 10 | - |

| F4 | 200 | 200 | 4 | 2 | 10 | - |

| F5 | 100 | 100 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 3 |

| F6 | 200 | 100 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 3 |

| F7 | 100 | 200 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 3 |

| F8 | 200 | 200 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 3 |

| *PC: Phosphatidyl choline |

Characterization of spirusomes

All experiments were performed in triplicate (n=3), which is consistent with prior nanocarrier-based studies evaluating vesicle characteristics, cytotoxicity, and pharmacokinetics under similar experimental conditions [20, 29]. This sample size is commonly used to ensure data reproducibility while minimizing biological and technical variability. Further studies with expanded sample sizes are planned for future confirmatory analyses.

Vesicle size and zeta potential

A Malvern Zetasizer from Malvern Instrument Ltd., UK, was employed to analyze the vesicle size of the formulated Spirusomes through dynamic light scattering at a consistent temperature of 25±2 °C. Concurrently, the zeta potential of the specific ATOR-SP system was also determined at the same temperature using a 90° scattering angle. To obtain readings within the sensitivity range of the instrument, the prepared Spirusomes were diluted 10 times with distilled water before the measurements. The mean values from triplicate measurements were recorded and reported for each parameter [30, 31].

Entrapment efficiency (EE%)

The EE% of atorvastatin in various Spirusome formulations was determined via the dialysis method. Briefly, 1 ml of Spirusomes was poured into a dialysis bag with a molecular weight cutoff of 12 kDa, and the bag was immersed in 30 ml of an aqueous solution (dialysis medium) and stirred with a paddle at a controlled temperature (37±0.5 °C) [32]. Dialysis was conducted for 2 h. Samples were withdrawn and further filtered with a 0.45 μm membrane filter. The concentrations of atorvastatin were estimated using UV spectroscopy (Shimadzu-1650 PC double beam, Japan) at 248 nm (λmax). The EE% values were calculated using the following equation [33]:

Where

Dt denotes the total amount of atorvastatin in the prepared Spirusomes.

Dd denotes the amount of atorvastatin that diffused into the receiver medium.

In vitro release studies

In vitro release studies of spirusomes were performed via the cellulose tube diffusion method. The cellulose tube was soaked overnight in the release media before the experiment. Thereafter, 1 ml of spirusomes was introduced into the cellulose tube. A dissolution medium comprising a 100 ml phosphate-buffered solution (PBS), pH of 7.4 at 37±0.5 °C, was used for the experiment, to which the cellulose-containing spirusomes were added, and rotation was carried out at a speed of 100 rpm within the medium [34].

Samples of 2 ml were withdrawn from the released media at preselected time points of 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 24 h. After collection, the samples were filtered and assayed using a spectrophotometric method at a wavelength of λmax 248 nm via UV spectroscopy (Shimadzu-1650 PC double beam, Japan). The assays were carried out in triplicate, and the results are reported as mean values±standard deviations [35].

Optimization of spirusomes

Numerical optimization was carried out via Design Expert® software with desirability constraints according to the description of the variables in , aiming to predict the level required to attain the optimal characteristics of Spirusomes. Desirability serves as an objective function that aims to maximize or minimize various factors within predefined limits [36]. The desirability scale runs between zero, representing situations out of the set limit that are undesirable, and one for attaining a certain set goal.

Morphological examination of the optimized spirusomes using TEM

The determination of the morphological features of the prepared optimized Spirusomes was carried out via transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In typical preparations, samples were diluted to appropriate optical densities with distilled water. The diluted sample (one drop) was placed onto a copper grid and allowed to dry for 10 min. Subsequently, staining was carried out using Phosphotungstic acid, and the sample was permitted to dry at room temperature for another 10 min. An examination of the sample was conducted using TEM equipment (JEOL, JEM-1230, Tokyo, Japan) [37, 38].

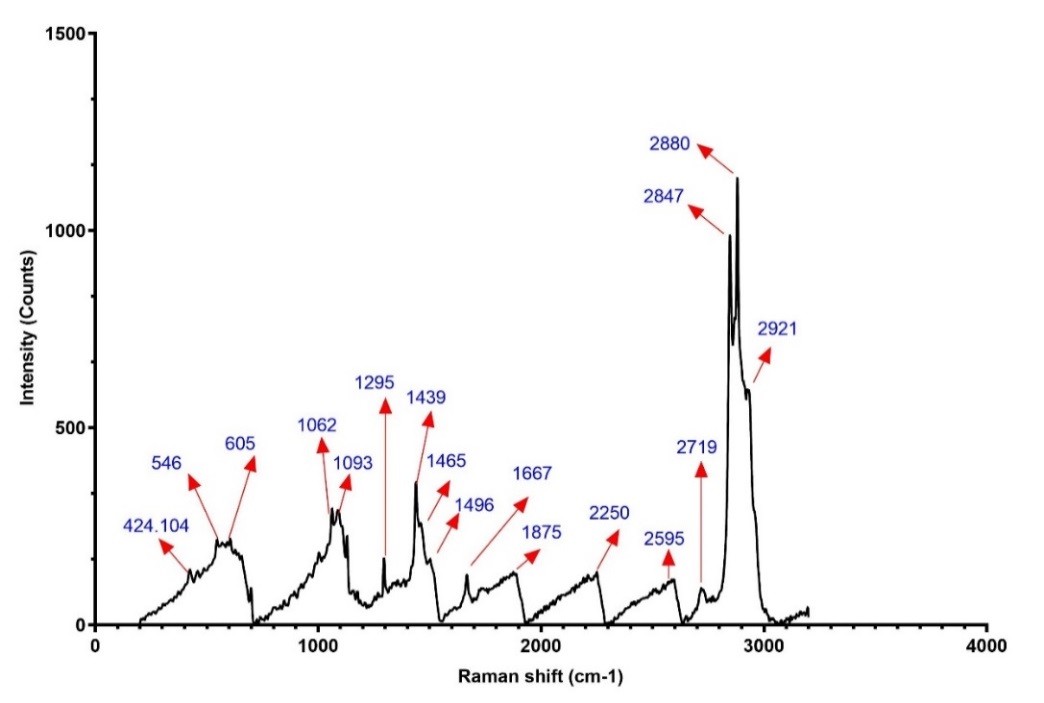

Compatibility study of the optimized spirusomes with the formulated additives using raman spectroscopy

To explore potential interactions between atorvastatin and other components within the optimized Spirusomes formulation, a Raman spectrometer was employed. Raman spectra were acquired for the optimized Spirusomes using Horiba Lab RAM HR Evolution (Edison, NJ, USA). The analysis was conducted at 25 °C, utilizing a 532 nm He-Cd laser line with grating 1800 (450-850 nm) and a 5% neutral density filter. The acquisition time was set at 20 sec without any delay. Measurements were carried out within the wavelength range of 200 to 3200 cm-1 to discern potential alterations, shifts in peaks, or broadening in the spectra [39].

Atorvastatin powder analysis using the Raman spectrometer as prescribed by Lim et al. [40] exhibited distinct peaks across a wide wavenumber range of 1800 cm−1 to 500 cm−1, i. e., peaks were seen at 1600 cm−1, 1525 cm−1, 1000 cm−1, and 885 cm−1.

In vitro anti-tumor activity of the optimized spirusomes in human brain cancer cells

Cell line

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the College of Pharmacy, Misr University for Science and Technology (approval code: IP09, 06-03-2023), Egypt, following the guidelines outlined in the WHO Guiding Principles on Human Cell, Tissue, and Organ Transplantation.

Human brain cancer cells, SNB-75, were provided by the Naval American Research Unit-Egypt. The cell line was authenticated via short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and was routinely tested and confirmed to be free of mycoplasma contamination using PCR-based methods prior to experiments. The cytotoxicity against these cancer cells was investigated using a modified MTT [3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay [41].

Cell viability assay

Human brain cancer cells (SNB-75, 10 × 10³ cells/well) were plated in 96-well microtiter plates with fresh complete growth media and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under 5% CO₂ in a water-jacketed incubator. After aspirating the media, the cells were combined with a fresh serum-free medium and treated with either pure atorvastatin, atorvastatin-loaded emulsomes, optimized Spirusomes, or Staurosporine (as a control) to obtain final concentrations of 0.4, 1.6, 6.3, 25, and 100 µg. The concentration range of 0.4 to 100 µg/ml was selected based on preliminary screening experiments conducted in our lab and aligned with previously reported statin-based cytotoxicity studies on glioma and other cancer cell lines. This range captures both sub-therapeutic and cytotoxic levels to enable accurate IC₅₀ determination [5, 42]. The cells were then incubated for another 48 h. After this period, the medium was removed and replaced with 40 µl** of MTT salt solution [3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] at a concentration of 2.5 mg/ml in each well. The plates were incubated for an additional four hours at 37 ºC with 5% CO₂. The reaction was halted, and the formed crystals were dissolved by adding 200 µl** of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) overnight at 37 °C. Absorbance was subsequently measured at 595 nm using a microplate reader, with 620 nm as the reference wavelength [41, 43].

Statistical comparisons between IC₅₀ values were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test to identify significant pairwise differences. Differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05 [44].

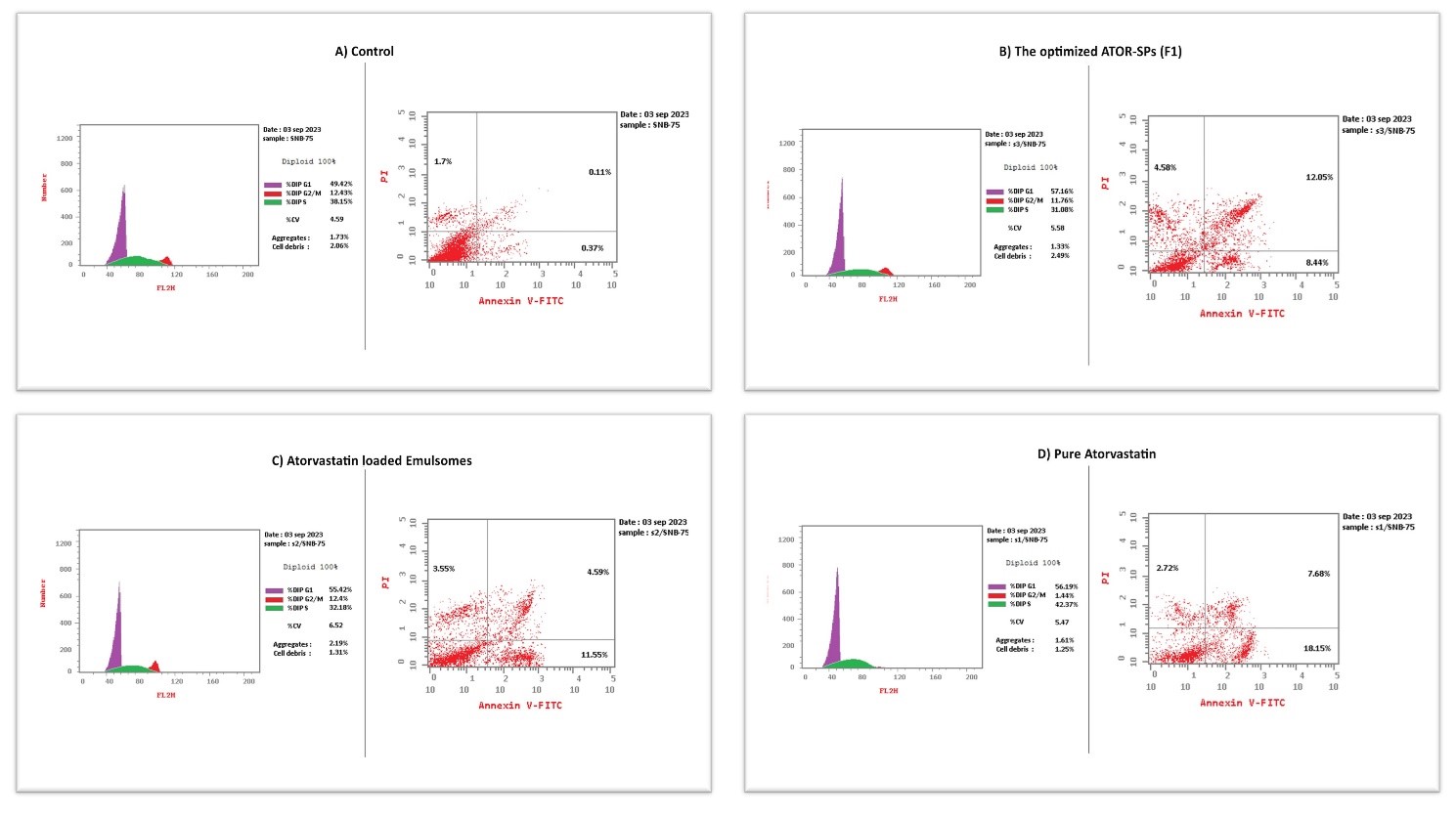

Cell cycle analysis

Human brain cancer cells (SNB-75) were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 (RPMI 1640) medium. The cells were then treated with 10 μg/ml PpCBF for 48 h. After treatment, the cells were collected and preserved overnight at- 20 °C in 70% ice-cold ethanol. Following fixation, the cells were rinsed with PBS in the dark for 30 min at 37 °C and then resuspended in 1 ml of PBS containing 1 mg/ml RNase (Sigma) and 50 μg/ml PI (Sigma). The DNA content was analyzed using flow cytometry (Beckman, USA). Sample concentrations were based on the IC50 values determined via the cell viability assay. The Cell Quest acquisition program (BD Biosciences) was employed to analyze cell cycle phase distributions [45].

In vivo pharmacokinetic study

Forty-two male albino rats (weighing 200-250 gm) were obtained from the breeding unit of the animal house at a local university, all animals and the experimental protocol were approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the College of Pharmacy, Misr University for Science and Technology (approval code: IP 09, 06-03-2023), Egypt, following the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. The rats were kept in an environment of controlled temperature (25±2 °C) and controlled relative humidity (55±5% RH) for one week before starting the experiment. The selected healthy male albino rats were divided and labeled into two groups (twenty-one rats n=21 in each). Group (1) received an atorvastatin calcium suspension via oral administration, and Group (2) received optimized Spirusomes via nasal administration. According to the animal-corrected dose of atorvastatin calcium depending on the human dose, all rats received atorvastatin equivalent to 1 mg/kg [46].

For intranasal dosing, rats were slightly anesthetized using anesthetic ether. Following this, the rats were held in a diagonal position supported from the back to receive the 40 μl animal-corrected dose of optimized Spirusomes (F1) (20 μl per nostril) via a microinjector fitted with a soft polyethylene tube with an internal diameter of 0.10 mm, targeting the nasal olfactory region [46]. For oral administration, the rats were given the equivalent dose using an oral feeding needle.

At various time intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 24 h) after both the oral and nasal administration of atorvastatin, three rats were euthanized via slaughtering at each time point. Blood samples were collected from the trunk into heparinized tubes and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min. The separated plasma was saved in a separate tube. To study atorvastatin brain accumulation, the skulls were removed, and then, the brain tissue samples were collected and homogenized using distilled water (three times its volume) at 24,000 rpm for 1 minute and transferred into tubes. Both the brain tissue and the separated plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis [47].

Pharmacokinetic analysis

The biological analysis of atorvastatin in the collected blood samples and brain tissue was carried out using a rapid HPLC. A Shimadzu LC-2010C HT system (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan) was utilized, which included a quaternary pump, CTO-10AS oven, and SPD-M20A photodiode array detector. The chromatographic separation of all drugs and internal standard (IS) was carried out using a reversed-phase LiChroCART® Purospher Star column (3 μm particle size, 4 mm internal diameter, 55 mm length; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) at 35 °C. The analysis was performed in the isocratic mode with a mobile phase composed of acetonitrile, methanol, and 2% (v/v) acetic acid (37.5:2.5:60, v/v/v) at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Atorvastatin was detected at a wavelength of 248 nm. The data were analyzed using version 1.5 of Analyst software (Foster, CA) [30, 48]. The average concentrations of atorvastatin in plasma and brain samples were graphed over time. All pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using a non-compartmental method via Phoenix™ WinNonlin® (version 8.4; Pharsight, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), including the maximum brain or plasma concentrations (Cmax) and time to obtain the maximum brain or plasma concentrations (Tmax). Moreover, the area under the curve (AUC) and the terminal half-life were measured [49, 50].

Brain targeting index (BTI) calculation

The brain targeting index (BTI) was calculated using the following formula [51]:

The BTI was determined at two points: (1) the Cmax and (2) AUC from 0 to 24 h (AUC0−24) and from 0 to infinity (AUC0−∞) for both oral and intranasal routes.

RESULTS

Spirulina fatty acids profile

The total lipid content was 7.02% by dry weight. The GC chromatogram revealed the presence of thirteen compounds. Six of these thirteen compounds are major compounds, while the remaining seven are minor compounds. The following were identified as major compounds: palmitic acid>gamma-linolenic acid>linoleic acid>oleic acid>stearic acid>palmitoleic acid () [52, 53].

Palmitic acid (C16:0) was found to be the predominant saturated fatty acid, while oleic acid and palmitoleic acid were established as the predominant monounsaturated fatty acids. However, oleic acid was present in S. platensis in trace amounts [54].

Generally, the predominant fatty acids were saturated palmitic acid (42.12%), monounsaturated fatty acids (16.73%), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (33.79%). The content of linoleic acid in the analyzed S. platensis was approximately the same as that reported for Spirulina sp. (12%–21%) and S. platensis (11%) [54]. However, alpha-linolenic acid was not identified in the current study compared to the published values of alpha-linolenic acid in Spirulina sp. (6%) and in S. platensis (17%) [53]. The same studies showed that S. platensis is a potential source of γ-linolenic acid, a highly valuable polyunsaturated fatty acid of excellent economic interest. γ-linolenic acid was identified as the initial intermediary in the conversion of linoleic acid to arachidonic acid. Moreover, it was observed that γ-linolenic acid can selectively destroy tumor cells without affecting normal cells, indicating its potential for medicinal use. Natural sources contain varying levels of γ-linolenic acid, rarely exceeding 25%. Hence, there has always been a keen interest in producing higher concentrations of γ-linolenic acid.

Table 3: Fatty acids profile of the cyanobacteria S. platensis

| Category | Fatty acids | % of total fatty acids |

| Saturated fatty acids 48.59 % | Palmitic acid | 42.12 |

| Stearic acid | 5.65 | |

| Lignoceric acid | 0.48 | |

| Margaric acid | 0.18 | |

| Arachidic acid | 0.16 | |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids 16.73 % | Oleic acid | 12.79 |

| Palmitoleic acid | 3.36 | |

| Trans-10-Heptadecenoic acid | 0.40 | |

| Elaidic acid | 0.18 | |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids 33.79 % | Gamma-Linolenic acid | 17.26 |

| Linoleic acid | 16.17 | |

| Eicosadienoic acid | 0.20 | |

| Dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid | 0.16 |

Characteristics of the prepared spirusomes

Effect of the different variables on Y1 (particle size)

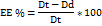

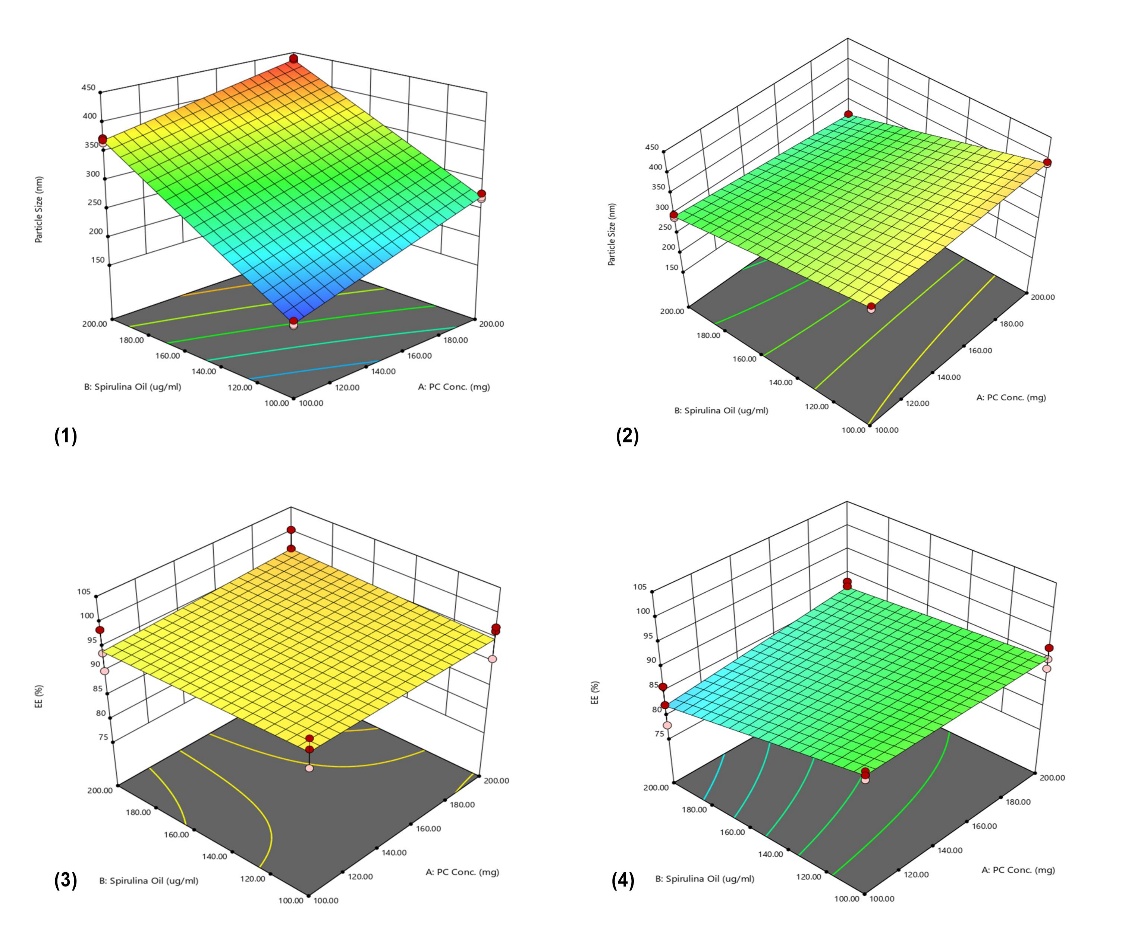

Referring to the results detailed in (particle size ranges from 173.7±4.36 for F1 to 436.5±3.45 for F4), it was observed that as the amount of PC and Spirulina oil increased, a significant increase in particle size (F=1513.48, P<0.0001) was observed. Moreover, when comparing formulations using the same amounts of PC and Spirulina oil but different hydration media, there was a consistent increase in particle size when the hydration medium shifted from distilled water to a mixture of distilled water and ethanol. This shift seemed to result in larger particle sizes in F5 to F8 compared to their F1 to F4 counterparts.

Fig. 1: 3D surface plots of phosphatidylcholine concentration and Spirulina oil amount Vs. Particle size when hydration media is (1) distilled water, (2) water–ethanol mixture, and Vs. Entrapment efficiency when hydration media is (3) distilled water, and (4) water–ethanol mixture. Data represent mean±SD, n = 3

Table 4: The particle size, zeta potential values, PDIs, and EE% of the prepared spirusomes

| No. | Particle size (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) | PDI | EE (%) |

| F1 | 173.7±4.36 | -30±2.47 | 0.374±0.132 | 95.17±2.9 |

| F2 | 272.6±4.8 | -25±1.52 | 0.717±0.155 | 94.91±3.49 |

| F3 | 369.4±4.16 | -17.6±4.25 | 0.571±0.191 | 94.25±4.14 |

| F4 | 436.5±3.45 | -20±3.53 | 0.675±0.129 | 96.35±4.02 |

| F5 | 370.4±4.41 | -24.8±2.59 | 0.547± 0.151 | 90.03±0.86 |

| F6 | 390.5±2.67 | -29.3±2.12 | 0.664±0.129 | 90.14±2.13 |

| F7 | 296.3±3.98 | -31.6±0.52 | 0.603±0.161 | 82.2±4.13 |

| F8 | 266.2±0.9 | -30.1±3.71 | 0.549±0.146 | 87.1±1.27 |

*PDI: Poly dispersibility index; EE%: entrapment efficiency percentage, *All data are represented as mean±SD, n3. The following 3D plots () describe the effect of different factors (A, B, and C) on the particle size of the formulated Spirusomes.

Effect of the different variables on Y2 (zeta potential) and Y3 (PDI)

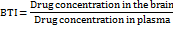

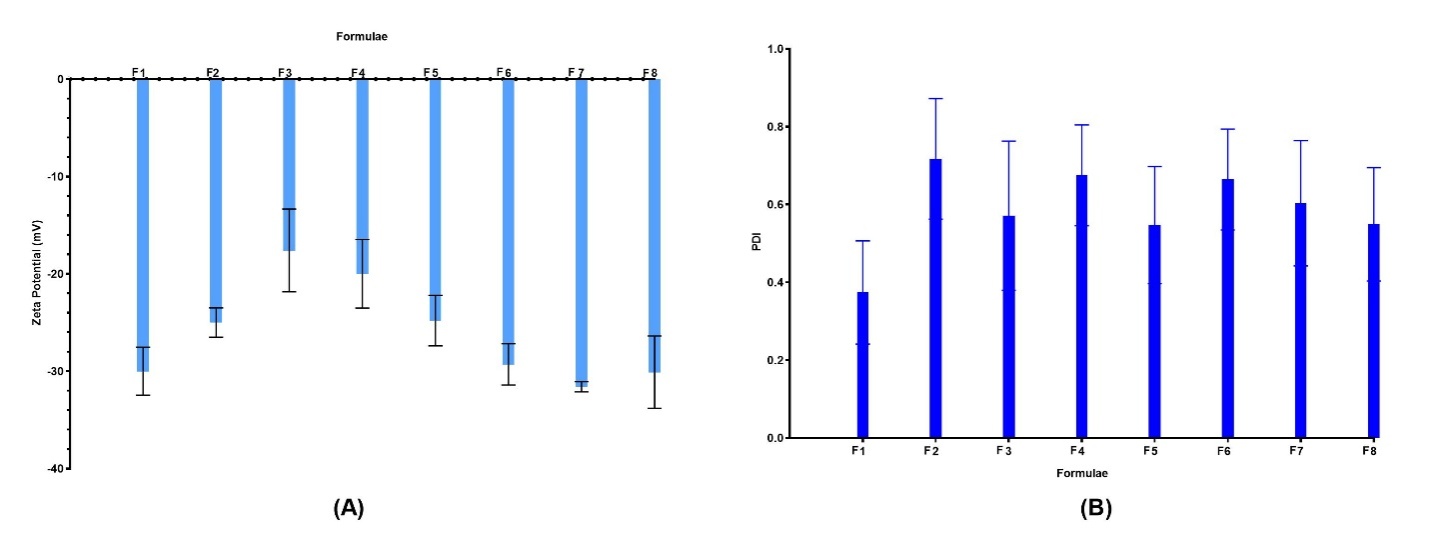

As indicated in and , across all formulae, a high negative surface charge was observed, ranging from-17.6±4.25 for F3 to-31.6±0.52 mV for F7. The PDIs for the formulated Spirusomes were consistently below 1, affirming uniformity in the size distribution [22].

Effect of the different variables on Y4 (Entrapment efficiency %)

As shown in and , while most formulae demonstrated a high entrapment efficiency ranging from 82.2±4.13 for F7 to 96.35±4.02 for F4, there was a significant difference in EE% among them (F=7.29, P<0.0005), suggesting that the composition might have influenced the entrapment of atorvastatin within the Spirusomes.

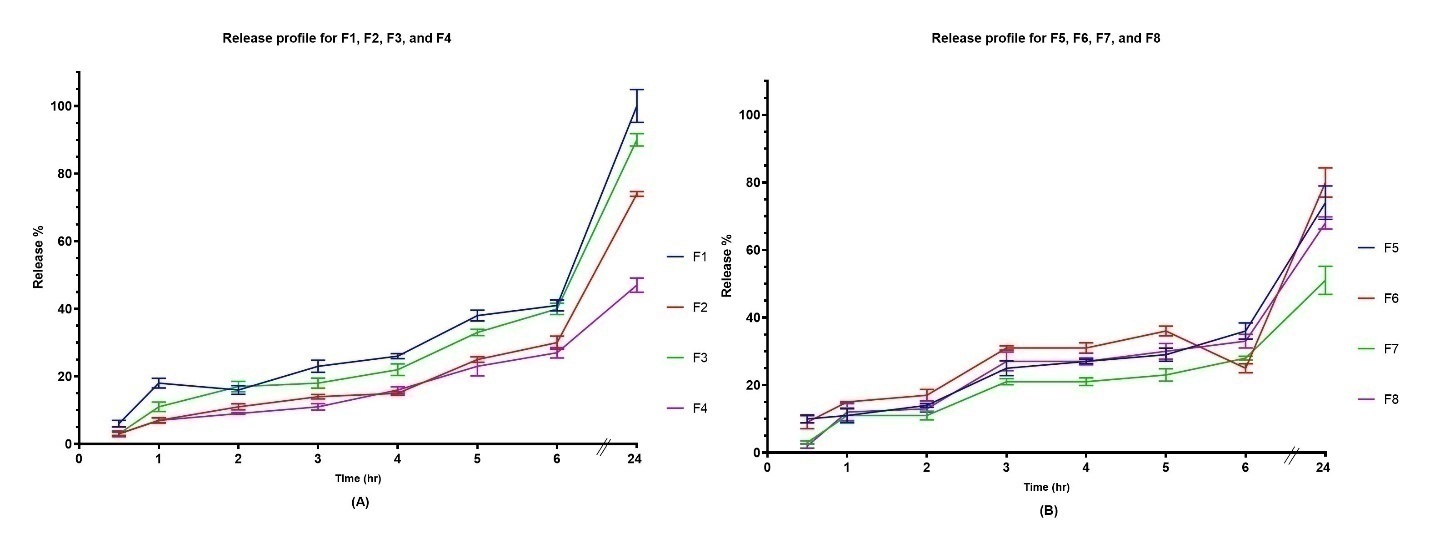

Effect of the different variables on Y5 (Release %)

The in vitro drug release studies of Spirusomes are represented graphically in . The results indicate that there is a significant difference (F = 53, p-value<0.0001) in the cumulative release percentage among the different formulations at Q 24h. Variations in the release profiles are based on the formulation parameters, such as the amount of PC, the concentration of Spirulina oil, and the type of hydration media used (distilled water or a mixture of distilled water and ethanol).

Fig. 2: (A) Zeta potential of different formulations showing colloidal stability; (B) PDI values reflecting particle size uniformity. Data represent mean±SD, n = 3. Error bars indicate standard deviation

Fig. 3: In vitro release profiles of atorvastatin from Spirusome formulations over 24 h. (A) Release from formulations F1–F4 (hydrated with distilled water), (B) F5–F8 (hydrated with water–ethanol mixture). All data are presented as mean±SD, n = 3

Optimization of the prepared spirusomes

displays the extensive outcomes derived from the regression analysis, covering all recorded responses. The results reveal a strong correlation between the predicted R2 values and the adjusted R2 values across all investigated responses. The model consistently demonstrated high precision ratios, surpassing the optimal value of 4. Meanwhile,

Table 6, generated using the Design Expert software, shows the top four potential solutions. Notably, F1 stands out with a desirability value of 0.859.

Table 5: Design summary of the 3FI full factorial design

| Response | Y1: Particle size | Y2: Zeta potential (absolutes) |

Y3: Poly dispersibility index (PDI) | Y4: Entrapment efficiency % | Y5: In vitro release % (Q 6h) |

| Minimum | 170.38 | 13.08 | 0.26 | 77.99 | 46.32 |

| Maximum | 439.72 | 34.23 | 0.87 | 100.33 | 103.08 |

| R2 | 0.9985 | 0.8115 | 0.3958 | 0.7612 | 0.9587 |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.9978 | 0.729 | 0.1314 | 0.6567 | 0.9406 |

| Pre. R-squared | 0.9966 | 0.5759 | 0.3595 | 0.4627 | 0.9070 |

| Adequate precision | 120.251 | 8.565 | 3.938 | 7.852 | 24.452 |

Table 6: The four possible best solutions were found using the Design Expert software

| No. | Phospholipid conc. | Spirulina oil amount | Hydration media | EE (%) | Size (nm) |

Charge (mV) |

PDI | Release (%) |

Desirability |

| 1 | 100 | 100 | Dist. Water | 95.169 | 173.7 | -29.9 | 0.37 | 99.99 | 0.859 |

| 2 | 100 | 108.02 | Dist. Water | 95.096 | 189.3 | -29.005 | 0.38 | 99.22 | 0.830 |

| 3 | 100 | 200 | Dist. to ethanol | 87.1 | 266.2 | -30.09 | 0.54 | 68.3 | 0.533 |

| 4 | 99.99 | 200 | Dist. to ethanol | 86.99 | 266.8 | -30.13 | 0.55 | 67.91 | 0.530 |

*PDI: Poly dispersibility index; EE%: entrapment efficiency percentage

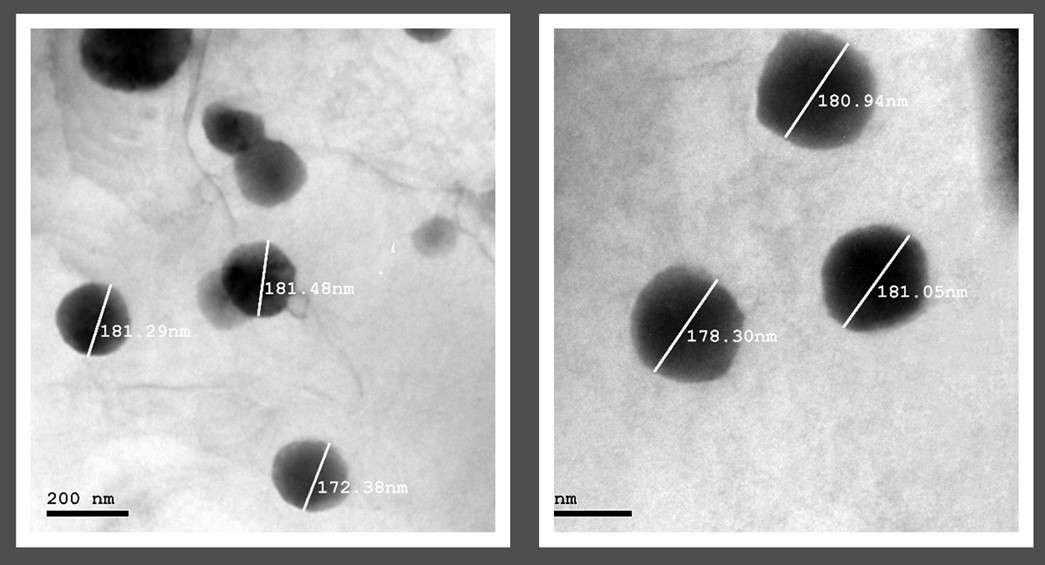

Morphological examination for the optimized Spirusomes using TEM

The TEM image shown in illustrates the formulated Spirusomes, with the particle sizes ranging from 172 to 181 nm, aligning with the Zetasizer measurements. Notably, the produced shape was distinctly spherical, with no observable aggregation, highlighting the uniformity and homogeneity of the prepared particles.

Fig. 4: Transmission electron microscopy image of the optimized Spirusomes (F1), showing spherical morphology and nanoscale particle size distribution. The scale bar indicates magnification. Particles appear discrete and well-dispersed

Investigation into the compatibility of optimized spirusomes with the formulated additives using Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy was performed on the optimized Spirusomes (F1), as depicted in . The analysis indicated that there were no significant changes, shifts, or broadening observed in the characteristic peaks of atorvastatin, indicating the absence of chemical interactions between the excipients and the administered drug.

In vitro anti-tumor activity of the optimized spirusomes in human brain cancer cells

The antitumor efficiency of the pure atorvastatin, atorvastatin-loaded emulsomes, and optimized Spirusomes was investigated against human brain cancer cell SNB-75. The optimized Spirusomes (F1) improved the cytotoxicity against SNB-75 (IC50=16.584±0.84) compared to atorvastatin-loaded emulsomes (the same as the optimized formula without Spirulina oil) (IC50=39.485±2.01) and pure atorvastatin (10.79±0.55) (). The enhanced cytotoxicity of pure atorvastatin is attributed to the use of 100% atorvastatin, whereas the prepared nanoparticles used 10% atorvastatin.

Flow cytometry analysis () revealed viable cells that stained negative with PI and annexin V (lower left), which represent 86.93 % of the untreated control cells, followed by brain cancer cells treated with atorvastatin-loaded emulsomes (80.31%), those treated with the optimized Spirusomes (F1) (74.4%), and then the cells treated with pure atorvastatin (71.45%).

Early apoptotic cells stained positive for annexin V (lower right), which represents 18.15% of cancer cells treated with pure atorvastatin, followed by atorvastatin-loaded Emulsomes (11.55%) and then the optimized Spirusomes (F1) (8.44%). Secondary necrotic cells or late apoptotic cells stained positive for both PI and annexin V (upper right), which represent 12.05 % of the cancer cells treated with the optimized Spirusomes (F1) followed by cells treated with pure atorvastatin (7.68%) and then the cancer cells treated with atorvastatin-loaded emulsomes (4.59%). In the control (untreated) cells, the percentage of early and late apoptosis was very low at 0.37% and 0.11%, respectively.

The upper left quadrant (negative for Annexin V and positive for PI) indicates primary necrotic cells. This population was minimal across all groups, suggesting that cell death occurred mainly via apoptosis rather than necrosis.

Fig. 5: Raman spectrum of optimized spirusomes (F1). The spectrum shows characteristic peaks for atorvastatin and lipid components, with no significant shifts, indicating physical compatibility and absence of chemical interaction between excipients and the drug

Fig. 6: Flow cytometry analysis of SNB-75 glioma cells stained with annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) to evaluate apoptosis. (A) Untreated control, (B) Spirusomes (F1), (C) Atorvastatin-loaded emulsomes, and (D) Pure atorvastatin

Table 7: In vitro cytotoxicity of the prepared formulation against human brain cancer cell line determined via the MTT assay

| Concentration (µg/ml) |

% Cell viability | |||

| Pure atorvastatin | Atorvastatin-loaded emulsomes | Optimized spirusomes (F1) | Staurosporine | |

| 0.4 | 78.37 | 84.68 | 79.145 | 65.937 |

| 1.6 | 68.873 | 82.41 | 67.602 | 57.847 |

| 6.3 | 55.576 | 71.75 | 57.717 | 49.088 |

| 25 | 41.605 | 58.03 | 46.684 | 40.815 |

| 100 | 30.025 | 35.17 | 36.352 | 31.083 |

| IC50 | 10.794±0.55 | 39.485±2.01 | 16.584±0.84 | 5.2839±0.27 |

| *IC50: half-maximal inhibitory concentration, *Data presented as mean±SD, n3. | ||||

Statistical analysis of IC₅₀ values was conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The results showed a statistically significant difference between the IC₅₀ of optimized Spirusomes (F1) and all other groups (p<0.01). This confirms that the presence of Spirulina oil in Spirusomes significantly enhanced the cytotoxicity of atorvastatin compared to its emulsome-loaded form.

In vivo pharmacokinetics assay

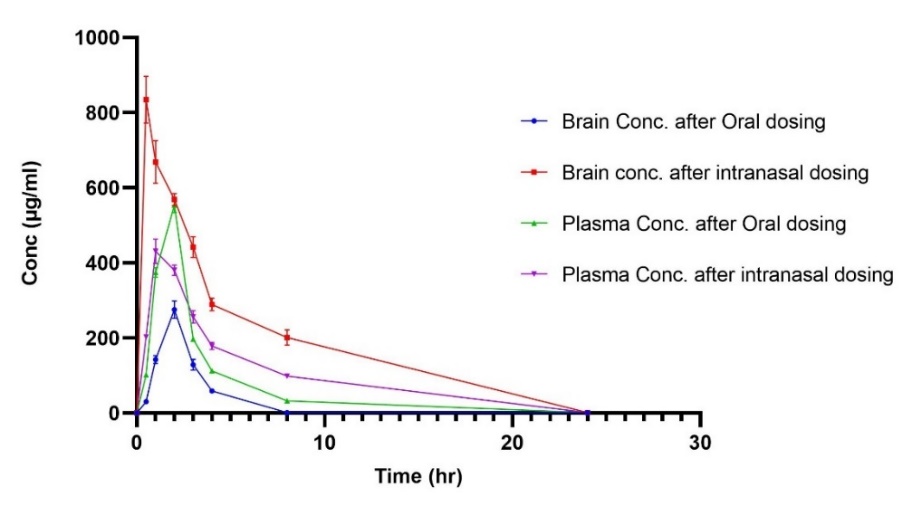

The in vivo study was conducted on healthy albino rats to compare the plasma and brain pharmacokinetics of orally administered atorvastatin calcium suspension to those of the optimized intranasal Spirusomes (F1). The mean plasma and brain concentrations of the drug over time for both administration routes are depicted in , with the corresponding pharmacokinetic parameters summarized in .

The brain data indicated that the intranasal administration of the optimized Spirusomes (Gp2) resulted in a significantly higher brain concentration (AUC0-24= 4660.685±216.849 ng. h/gm) compared to the oral administration of the atorvastatin suspension (Gp1) (AUC0-24= 676.925±11.69 ng. h/gm) (P = 0.0007). Regarding the peak time (Tmax), the optimized Spirusomes administered intranasally reached the peak brain concentration in 0.5 h, significantly faster than the 2 h required for the oral atorvastatin suspension.

Plasma data showed that the oral administration of the atorvastatin suspension resulted in higher maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax = 553.65±0.768 ng/ml) compared to the intranasal administration of the optimized formula (Cmax = 430.98±0.589 ng/ml). However, the area under the curve (AUC₀-₂₄) for plasma was significantly lower after oral administration (1683.0525±26.535 ng. h/ml) compared to intranasal administration (2486.725±47.5 ng. h/ml) (P = 0.0001).

Brain targeting index (BTI)

The BTI values for the optimized Spirusomes are presented in , the BTI for oral administration was below 1 for all parameters, indicating suboptimal brain targeting. In contrast, the BTI for intranasal administration was greater than 1, suggesting effective brain targeting [55].

Table 8: Pharmacokinetic parameters of atorvastatin calcium after oral and intranasal administration in plasma and brain tissues

| PK parameters | After oral administration | After intranasal administration | ||

| Plasma | Brain | Plasma | Brain | |

| Cmax (ng/ml) – (ng/gm) | 553.65±0.768 | 275.25±0.111 | 430.98±0.589 | 834.66±0.939 |

| Tmax (h) | 2.000 | 2.000 | 1.000 | 0.500 |

| AUC0-24 (ng. h/ml) – (ng. h/gm) | 1683.0525±26.535 | 676.925±11.69 | 2486.725±47.5 | 4660.685±216.849 |

| AUC0-∞ (ng. h/ml) – (ng. h/gm) | 1705.2±17.03 | 697.74±3.109 | 2508.457±58.34 | 4676.88±224.9 |

| T1/2 (h) | 3.25±0.087 | 5.066±1.35 | 2.743±0.29 | 2.41±0.32 |

| *PK: Pharmacokinetics; Cmax: maximum concentration; Tmax: time required for maximum concentration; AUC: area under the curve; T1/2: half-life., *All data are represented as mean±SD, n3. | ||||

Fig. 7: Pharmacokinetic profiles of atorvastatin in plasma and brain after oral and intranasal administration in rats. The curves represent mean drug concentrations over time for oral atorvastatin suspension and intranasally administered Spirusomes (F1). Data are presented as mean±SD, n = 3. Error bars indicate standard deviation

Table 9: Brain targeting index (BTI) of spirusomes after oral and intranasal administration

| Parameters | After oral administration | After intranasal administration |

| Cmax BTI | 0.497 | 1.937 |

| AUC0−24 BTI | 0.402 | 1.874 |

| AUC0−∞ BTI | 0.409 | 1.864 |

| *BTI: Brain targeting index. |

DISCUSSION

The size of particles plays a critical role in many aspects of drug delivery. It can significantly influence drug entrapment, release kinetics, and the ability of drugs to cross the blood–brain barrier [56]. A reduction in particle size has several advantages. It increases surface area, which may allow for increased drug permeability. Systems with smaller sizes are also less likely to be detected and taken up by the immune system, which may result in better circulation and delivery [57, 58].

The increase in particle size with higher concentrations of PC and Spirulina oil suggests that these lipophilic components could play a part in forming larger particle sizes in the resulting Spirusomes due to their role as base materials [59]. Moreover, the gradual increase in particle size observed while transferring from distilled water to a mixture of distilled water and ethanol can be attributed to the function of ethanol in increasing the solubility of lipids, thereby increasing the amount of phospholipid bilayers [60, 61].

The surface charge of nanoparticles is one of the important factors that could affect the efficacy of any intranasal drug delivery system, especially in targeting the brain. It has a negative charge because of sialic acid residues from the nasal mucosa [62]. Despite experiencing a certain degree of electrostatic repulsion due to the negatively charged nature of the nanoparticles [63], they are effective for intranasal delivery because of their lower toxicity [64], improved colloidal stability, and reduced interaction with mucin, which decreases rapid clearance via mucociliary action and therefore prolongs their residence time in the nasal cavity [65]. This is complemented by the mucoadhesive properties conferred by lecithin, a major component of the formulated nanoparticles. Considering the olfactory and trigeminal neural pathways, and particularly in light of studies indicating that only negatively charged nanoparticles (with a zeta potential<−20 mV) adhere to neurons, our results are consistent with these findings [66].

The pronounced negative surface charge noted across all formulations may be indicative of the significant electrostatic stabilization inherent in the Spirusomes [67]. More likely, this observed negative charge is due to the structural composition of Spirusomes, particularly the roles played by soya PC and Compritol [9, 68]. It was found that the negative charge identified at the surface of the prepared compounds was attributed to the composition of negatively charged phospholipids at the outer surface [69].

The PDI was the measure used to assess the uniformity of vesicle size in the formulation. As PDI values are increased, the population becomes heterogeneous; therefore, it would be subject to aggregation and hence bring about instability in the formulation [70]. On the other hand, low values of PDI indicate a more consistent homogeneous size distribution [71, 72]. According to the literature, a PDI value between 0.1 and 0.7 indicates a distribution of particle sizes that is almost homogenous, while a PDI value above 0.7 suggests high variability in macromolecular sizes in the solution [73]. The homogeneity in the size distribution could be attributed to the zeta potential obtained for all formulated samples, which generates repulsive forces between formed particles. Furthermore, the tiny size of the particles in the prepared formulations could also be responsible for such observations [74].

The marked differences found in entrapment efficiency (EE %) among different formulations suggest that the composition of Spirusomes is essential for atorvastatin entrapment. Higher levels of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and Spirulina oil enhance the EE% of lipophilic atorvastatin in the Spirusomes matrix. Formula F4, which has the highest EE% of 96.35±4.02, may suggest that certain ratios or higher concentrations of these components could result in more effective drug entrapment [9, 75].

Notably, the nature of the medium of hydration does not seem to follow a consistent trend in the percentage of EE%, which is in line with the findings reported by Elnady et al. [13].

The significant differences in the drug release profiles among the formulations indicate the impact of formulation parameters on the kinetics of drug release. Formulations with higher amounts of PC tend to exhibit more controlled release profiles, which may be due to enhanced vesicle stability and the reduced leakage of entrapped atorvastatin calcium [74].

The Spirulina oil concentration in the formulation has a nonlinear effect on the drug release dynamic. While increasing the Spirulina oil concentration usually results in a higher release percentage, this trend has not been consistently observed in the entire formulation. For instance, Formula F4, while having a higher Spirulina oil concentration than Formula F3, surprisingly exhibited lower release percentages. This inconsistency therefore, underlines the complex interactions among formulation constituents and their influence on the kinetics of drug release.

Hydration media constitute another important factor affecting vesicles' release behavior. Generally, formulae containing water and ethanol (Formulae F5-F8) present lower values of cumulative release compared with those using only water (Formulae F1-F4). Such an impact could be attributed to ethanol's presence in the vesicle's structure. It is known that ethanol disrupts the lipid bilayer, rendering it thinner and more permeable. While this can be favorable initially by enhancing drug release, the structural integrity of the vesicles is compromised, resulting in poorer drug entrapment and thus poor long-term diffusion [76]. It has been shown that ethanol can reduce the d-spacing of bilayers, which may result in the closer packing of the lipid molecules themselves and potentially alter sustained release patterns. This occurs in systems such as ethosomes, where ethanol enhances drug penetration but simultaneously alters vesicle stability and release over time [77, 78].

Moreover, after GC-MS analysis, the composition of Spirulina oil was found to be rich in oleic acid and palmitic acid, making it a suitable lipid source for the formation of Spirusomes. The presence of oleic acid enhances membrane fluidity, facilitates cellular uptake, and improves drug permeability, while palmitic acid contributes to structural stability and controlled drug release. These properties enable Spirusomes to mimic traditional emulsomes while offering a green synthesis approach that eliminates the need for synthetic lipid components. The natural lipid profile of Spirulina oil ensures biocompatibility and sustainability, rendering Spirusomes a promising eco-friendly nanocarrier. Furthermore, the bioactive nature of Spirulina-derived lipids may introduce additional therapeutic benefits, further enhancing the potential of Spirusomes in drug delivery applications [79, 80].

The close relationship between the predicted R² and adjusted R² for all responses investigated within the optimization process demonstrates the reliability and robustness of the regression model. High precision ratios, consistently above the desired value of 4, also reflect the model's remarkable accuracy. The results indicate that the model is suitably designed for investigating the design space, thus serving as an essential instrument for forecasting and enhancing formulation parameters [81].

The cell line results indicated that the optimized Spirusomes (F1) significantly improved cytotoxicity against human brain cancer cell SNB-75 compared to atorvastatin-loaded emulsomes and pure atorvastatin. A lower IC50 value for pure atorvastatin is attributed to the higher concentration of the drug used in its pure form [82]. Despite the enhanced delivery properties of the nanocarrier. This apparent discrepancy can be explained by the immediate availability of the full drug dose in solution when using free atorvastatin, which facilitates rapid interaction with cellular targets. In contrast, atorvastatin in the Spirusomes is encapsulated, resulting in a sustained release profile that delays its full cytotoxic potential during the exposure period. This controlled release is beneficial in vivo for prolonged therapeutic effect and reduced systemic toxicity, but it may cause an underestimation of cytotoxic potency in short-term in vitro assays. Similar observations have been reported with other nanocarrier systems [83].

However, the optimized Spirusomes (F1) exhibited better performances than the atorvastatin-loaded emulsomes, which might be justified by the presence of Spirulina oil. The enhanced cytotoxicity observed may be attributed, in part, to the intrinsic bioactivity of the oil itself. Spirulina oil contains high levels of γ-linolenic acid (GLA), which has been reported to exert pro-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects in various cancer models [84]. GLA can modulate membrane lipid composition and promote the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), contributing to cancer cell apoptosis [85].

Additionally, the lipophilic nature of the Spirulina oil may enhance the cellular uptake of the nanocarrier through improved membrane interaction or endocytic pathways, thereby facilitating more efficient intracellular delivery of atorvastatin [86]. This dual role—bioactive lipid-mediated cytotoxicity and enhanced drug delivery—may collectively account for the improved therapeutic profile of Spirusomes compared to emulsomes formulated with inert oils.

The flow cytometry analysis emphasizes the cytotoxic effects of different formulations on cancer cells, by which the optimized Spirusomes (F1) produce a higher percentage of early and late apoptotic cells compared to atorvastatin-loaded emulsomes. The presence of Spirulina oil in optimized Spirusomes (F1) appears to enhance the pro-apoptotic characteristics of the formulation, as evidenced by the higher percentages of apoptotic and necrotic cells compared to the other treatments [87].

These results are in line with previous studies that investigated the potential antitumor effects of statins, especially their ability to induce apoptosis in cancerous cells [2, 82, 88]. However, the higher levels of apoptosis observed with the optimized Spirusomes (F1) indicate that the design of this formulation, particularly the presence of Spirulina oil, may contribute substantially to improvements in the therapeutic efficacy of atorvastatin on brain cancer cells. Similarly, the low levels of both early and late apoptosis in untreated control cells show that the cytotoxic effects are a result of the specific actions of the treatments being administered.

In the in vivo pharmacokinetic study, the significantly higher brain concentration observed following the intranasal administration of the optimized Spirusomes (F1) compared to the oral administration of atorvastatin suspension suggests that the intranasal route is more effective for delivering the drug to the brain. The enhanced brain exposure (AUC₀-₂₄ = 4660.685±216.849 ng. h/gm) can be attributed to the highly negatively charged, nanosized formulation (173.7±4.36 nm,-29.9 mV), which facilitates drug accumulation in brain tissue via various nerve pathways while also bypassing mucociliary clearance, as previously explained. This is further supported by the fact that intranasal administration bypasses first-pass metabolism, allowing for more direct transport to the brain via the olfactory and trigeminal pathways [89-91].

The observed higher plasma AUC following intranasal administration of the optimized Spirusomes (F1) compared to oral administration can be explained by several well-documented mechanisms. The nasal route bypasses hepatic first-pass metabolism, which can significantly degrade atorvastatin during oral absorption due to its extensive hepatic extraction [92, 93]. Furthermore, the high vascularization of the nasal mucosa facilitates rapid and efficient systemic absorption, particularly for lipophilic compounds like atorvastatin [94].

In addition, lipid-based nanocarriers such as Spirusomes may exploit lymphatic drainage pathways, which further aid in systemic delivery and protection of the drug from enzymatic degradation [95]. Therefore, the elevated AUC values for intranasal administration likely reflect the combined effect of avoiding first-pass metabolism, enhanced vascular absorption, and protective encapsulation within Spirulina oil-based vesicles.

The faster Tmax observed with intranasal administration (0.5 h) compared to oral administration (2 h) underscores the efficiency of direct brain delivery through the intranasal route, which bypasses the gastrointestinal tract and avoids the delays associated with oral administration. This direct transport to the brain may involve both the olfactory and trigeminal nerves, as well as systemic circulation, contributing to quicker drug absorption and brain penetration [96].

The higher maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) observed with oral administration likely result from the larger surface area and higher vascularity of the gastrointestinal tract compared to the nasal cavity [97]. However, the lower AUC₀-₂₄ for plasma following oral administration indicates that first-pass metabolism significantly reduces the systemic availability of the drug when taken orally [98].

The increased bioavailability of atorvastatin in brain tissues (increased selectivity) following intranasal administration can also be attributed not only to the nanosized formulation but also to the mucoadhesive properties of lecithin in the formulation, which enhances the contact time within the nasal cavity, allowing higher drug concentrations to reach the brain [99].

BTI is a crucial parameter for evaluating the effectiveness of drug targeting to the brain. In this study, the BTI for intranasal administration was greater than 1, demonstrating efficient brain targeting. The BTI values for intranasal administration were 1.937 for Cmax, 1.874 for AUC0−24, and 1.864 for AUC0−∞, all of which indicate substantial drug accumulation in the brain relative to the plasma [55, 100].

This study used non-compartmental analysis (NCA) to estimate pharmacokinetic parameters. While suitable for basic profiling, NCA lacks detail on drug distribution dynamics. Future studies will apply compartmental modeling to better understand atorvastatin transport between the plasma and the brain compartments.

Overall, these findings suggest that intranasal administration of the optimized Spirusomes offers a more efficient and targeted approach for delivering atorvastatin to the brain, potentially improving therapeutic outcomes for brain cancer conditions.

CONCLUSION

This study provides a paradigm shift in glioma treatment by integrating Spirulina oil into nano-vesicular Spirusomes for intranasal administration. The optimized formulation demonstrated superior brain penetration, enhanced anticancer efficacy, and a promising pharmacokinetic profile, positioning Spirusomes as a transformative platform for targeted brain cancer therapy.

The optimized formula exhibited satisfying stringent requirements with respect to particle size, zeta potential, and drug loading efficiency, resulting in a noteworthy desirability score of 0.859. Importantly, it’s in vitro release profile revealed nearly complete drug release within 24 h, without any discernible drug interaction with the additives employed in the formulation process.

Significantly, in vitro experiments conducted on brain cancer cells demonstrated the substantially lower concentrations of statins required to inhibit cell growth compared to other experimental formulations. These findings underscore the potential of the green-synthesized Spirusomes as a highly promising delivery system for drugs such as statins in the treatment of brain cancer, representing a significant advancement in therapeutic strategies.

While the current study demonstrates promising pharmacokinetic and cytotoxic profiles for the Spirusomes formulation, it is important to acknowledge that these findings are limited to healthy animal models and in vitro assays. Future work should involve evaluating the therapeutic efficacy and safety of Spirusomes in orthotopic glioma models to validate their potential for brain-targeted cancer therapy. This step is essential to confirm the observed cytotoxic advantages in a disease-relevant biological environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are thankful to Misr University for Science and Technology, College of Pharmacy, and SEF MUST for providing all necessary equipment and resources. We also extend our sincere appreciation to the Egyptian National Research Center for their invaluable support throughout this research study.

FUNDING

This research received no external funding.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Mahmoud Eltahan: Methodology, Writing – original draft, and corresponding author. Doha H. Abou Baker: Methodology, Resources, review and editing. Heba S Abbas: Methodology, Resources, and Writing – review and editing. Rehab Abdelmonem: Conceptualization, Validation, Resources, Supervision, and Writing – review and editing. Mohamed El-Nabarawi: Conceptualization and Supervision. Alshaimaa Attia: Conceptualization, Validation, Methodology, and Writing – review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Qiu Q, Ding X, Chen J, Chen S, Wang J. Nanobiotechnology based treatment strategies for malignant relapsed glioma. J Control Release. 2023 Jun;358:681-705. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.05.016, PMID 37196900.

Alrosan AZ, Heilat GB, Al Subeh ZY, Alrosan K, Alrousan AF, Abu Safieh AK. The effects of statin therapy on brain tumors particularly glioma: a review. Anti Cancer Drugs. 2023;34(9):985-94. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000001533, PMID 37466094.

Zhou X, Wu X, Wang R, Han L, Li H, Zhao W. Mechanisms of 3-hydroxyl 3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase in alzheimers disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;25(1):170. doi: 10.3390/ijms25010170, PMID 38203341.

Dong H, Li M, Yang C, Wei W, He X, Cheng G. Combination therapy with oncolytic viruses and immune checkpoint inhibitors in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: an approach of complementary advantages. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12935-022-02846-x, PMID 36604694.

Sarbassova G, Nurlan N, Raddam Al Shammari B, Francis N, Alshammari M, Aljofan M. Investigating potential anti-proliferative activity of different statins against five cancer cell lines. Saudi Pharm J. 2023;31(5):727-35. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2023.03.013, PMID 37181137.

Zarif Attalla K, Hassan DH, Teaima MH, Yousry C, El Nabarawi MA, Said MA. Enhanced intranasal delivery of atorvastatin via superparamagnetic iron-oxide loaded nanocarriers: cytotoxicity and inflammation evaluation and in vivo in silico and network pharmacology study for targeting glioblastoma management. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2025;18(3):421. doi: 10.3390/ph18030421, PMID 40143197.

Telange DR, Bhaktani NM, Hemke AT, Pethe AM, Agrawal SS, Rarokar NR. Development and characterization of pentaerythritol EudragitRS100 co-processed excipients as solid dispersion carriers for enhanced aqueous solubility in vitro dissolution and ex vivo permeation of atorvastatin. ACS Omega. 2023;8(28):25195-208. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c02280, PMID 37483203.

Ariaeinia M, Rahimpour E, Mirzaeei S, Fathi Azarbayjani A, Jouyban A. Thermodynamic analysis of atorvastatin calcium in solvent mixtures at several temperatures. Phys Chem Liq. 2023;61(4):275-84. doi: 10.1080/00319104.2023.2208255.

Singh S, Khurana K, Chauhan SB, Singh I. Emulsomes: new lipidic carriers for drug delivery with special mention to brain drug transport. Future J Pharm Sci. 2023;9(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s43094-023-00530-z.

Yadav AK, Jain K. Novel carrier systems for targeted and controlled drug delivery: springer; 2024 Dec 23.

Abdelbari MA, Elshafeey AH, Abdelbary AA, Mosallam S. Implementing nanovesicles for boosting the skin permeation of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2023;24(7):195. doi: 10.1208/s12249-023-02649-x, PMID 37770750.

Demirci Z, Islek Z, Siginc HI, Sahin F, Ucisik MH, Bolat ZB. Curcumin loaded emulsome nanoparticles induces apoptosis through p53 signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer cell line PANC-1. Toxicol In Vitro. 2025 Jan;102:105958. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2024.105958, PMID 39442639.

Elnady RE, Amin MM, Zakaria MY. A review on lipid based nanocarriers mimicking chylomicron and their potential in drug delivery and targeting infectious and cancerous diseases. AAPS Open. 2023;9(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s41120-023-00080-x.

El Zaafarany GM, Soliman ME, Mansour S, Awad GA. Identifying lipidic emulsomes for improved oxcarbazepine brain targeting: in vitro and rat in vivo studies. Int J Pharm. 2016;503(1-2):127-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.02.038, PMID 26924357.

Aldawsari HM, Ahmed OA, Alhakamy NA, Neamatallah T, Fahmy UA, Badr-Eldin SM. Lipidic nano sized emulsomes potentiates the cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of raloxifene hydrochloride in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells: factorial analysis and in vitro anti-tumor activity assessment. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(6):783. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13060783, PMID 34073780.

Alhakamy NA, Badr Eldin SM, Ahmed OA, Asfour HZ, Aldawsari HM, Algandaby MM. Piceatannol loaded emulsomes exhibit enhanced cytostatic and apoptotic activities in colon cancer cells. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020;9(5):419. doi: 10.3390/antiox9050419, PMID 32414040.

Bigagli E, D Ambrosio M, Cinci L, Pieraccini G, Romoli R, Biondi N. A comparative study of metabolites profiles anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of methanolic extracts from three arthrospira strains in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Algal Res. 2023;73(11):103171. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2023.103171.

Gomez PI, Mayorga J, Flaig D, Castro Varela P, Jaupi A, Ulloa PA. Looking beyond Arthrospira: comparison of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of ten cyanobacteria strains. Algal Res. 2023 Jul;74:103182. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2023.103182.

Czerwonka A, Kalawaj K, Slawinska Brych A, Lemieszek MK, Bartnik M, Wojtanowski KK. Anticancer effect of the water extract of a commercial Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) product on the human lung cancer A549 cell line. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018 Oct;106:292-302. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.116, PMID 29966973.

El Menshawe SF, Shalaby K, Elkomy MH, Aboud HM, Ahmed YM, Abdelmeged AA. Repurposing celecoxib for colorectal cancer targeting via pH-triggered ultra-elastic nanovesicles: pronounced efficacy through up-regulation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway in DMH-induced tumorigenesis. Int J Pharm X. 2024 Jun;7:100225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpx.2023.100225, PMID 38230407.

Al Jayoush AR, Hassan HA, Asiri H, Jafar M, Saeed R, Harati R. Niosomes for nose to brain delivery: a non-invasive versatile carrier system for drug delivery in neurodegenerative diseases. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2023 Nov;89:105007. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2023.105007.

Centis V, Vermette P. Physico-chemical properties and cytotoxicity assessment of PEG-modified liposomes containing human hemoglobin. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2008;65(2):239-46. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.04.009, PMID 18538549.

Liu S, Abu Hajar HA, Riefler G, Stuart BJ. Lipid extraction from Spirulina sp. and Schizochytrium sp. using supercritical CO2 with methanol. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018(1):2720763. doi: 10.1155/2018/2720763, PMID 30627545.

Neag E, Stupar Z, Varaticeanu C, Senila M, Roman C. Optimization of lipid extraction from Spirulina spp. by ultrasound application and mechanical stirring using the Taguchi method of experimental design. Molecules. 2022;27(20):6794. doi: 10.3390/molecules27206794, PMID 36296385.

Abo El Enin HA, Mostafa RE, Ahmed MF, Naguib IA, A Abdelgawad M, Ghoneim MM. Assessment of nasal brain targeting efficiency of new developed mucoadhesive emulsomes encapsulating an anti-migraine drug for effective treatment of one of the major psychiatric disorders symptoms. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(2):410. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14020410, PMID 35214142.

Kamel R, AbouSamra MM, Afifi SM, Galal AF. Phyto-emulsomes as a novel nano-carrier for morine hydrate to combat leukemia: in vitro and pharmacokinetic study. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022 Sep;75:103700. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103700.

Karroum R, Ucısık MH. Efficacy and safety of sulforaphane loaded emulsomes as tested on MCF7 and MCF10A cells. Turk J Biochem. 2024;49(5):629-36. doi: 10.1515/tjb-2023-0210.

Yassein AS, Elamary RB, Alwaleed EA. Biogenesis characterization and applications of Spirulina selenium nanoparticles. Microb Cell Factories. 2025;24(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12934-025-02656-6, PMID 39915798.

Baiomy AM, Younis MK, Kharshoum RM, Alsalhi A, Zaki RM, Afzal O. Optimized delivery of enalapril maleate via polymeric Invasomal in situ gel for glaucoma treatment: in vitro, in vivo, and histological studies. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2025 Apr;106:106685. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2025.106685.

Shulyak N, Liushuk K, Semeniuk O, Yarema N, Uglyar T, Popovych D. Study of the dissolution kinetics of drugs in solid dosage form with lisinopril and atorvastatin and intestinal permeability to assess their equivalence in vitro. Pharmacia. 2022;69(1):61-7. doi: 10.3897/pharmacia.69.e77319.

Patil PS, Dhawale SC. Development of ritonavir loaded nanoparticles: in vitro and in vivo characterization. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11(3)284-8. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i3.23145.

Ramesh D, Bakkannavar SM, Bhat VR, Pai KS, Sharan K. Comparative study on drug encapsulation and release kinetics in extracellular vesicles loaded with snake venom L-amino acid oxidase. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2025;26(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s40360-025-00938-8, PMID 40340782.

Wu KW, Sweeney C, Dudhipala N, Lakhani P, Chaurasiya ND, Tekwani BL. Primaquine loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) and nanoemulsion (NE): effect of lipid matrix and surfactant on drug entrapment in vitro release and ex vivo hemolysis. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2021;22(7):240. doi: 10.1208/s12249-021-02108-5, PMID 34590195.

Alhakamy NA, Badr Eldin SM, Aldawsari HM, Alfarsi A, Neamatallah T, Okbazghi SZ. Fluvastatin loaded emulsomes exhibit improved cytotoxic and apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2021;22(5):177. doi: 10.1208/s12249-021-02021-x, PMID 34128106.

Elgendy HA, Makky AM, Elakkad YE, Awad HH, Hassab MA, Younes NF. Atorvastatin loaded lecithin coated zein nanoparticles based thermogel for the intra-articular management of osteoarthritis: in silico, in vitro, and in vivo studies. J Pharm Investig. 2024;54(4):497-518. doi: 10.1007/s40005-024-00666-x.

Chopra A, Singh S, Kanoungo A, Singh G, Gupta NK, Sharma S. Multi-objective optimization of nitrile rubber and thermosets modified bituminous mix using desirability approach. PLOS One. 2023;18(2):e0281418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0281418, PMID 36809361.

Asfour MH, Salama AA. Coating with tripolyphosphate crosslinked chitosan as a novel approach for enhanced stability of emulsomes following oral administration: Rutin as a model drug with improved anti-hyperlipidemic effect in rats. Int J Pharm. 2023 Sep 25;644:123314. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2023.123314, PMID 37579826.

Mahajan A, Kaur S, Kaur S. Design formulation and characterization of stearic acid-based solid lipid nanoparticles of candesartan cilexetil to augment its oral bioavailability. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11(4):344-50. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i4.23849.

Sun Z, Lin B, Yang X, Zhao B, Zhang H, Dong Q. Review of the application of Raman spectroscopy in qualitative and quantitative analysis of drug polymorphism. Curr Top Med Chem. 2023;23(14):1340-51. doi: 10.2174/1568026623666221223113342, PMID 36567287.

Lim YI, Han J, Woo YA, Kim J, Kang MJ. Rapid quantitation of atorvastatin in process pharmaceutical powder sample using Raman spectroscopy and evaluation of parameters related to accuracy of analysis. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2018 Jul 5;200:26-32. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.04.017, PMID 29660679.

El Menshawi BS, Fayad W, Mahmoud K, El Hallouty SM, El Manawaty M, Olofsson MH. Screening of natural products for therapeutic activity against solid tumors. Indian J Exp Biol. 2010;48(3):258-64. PMID 21046978.

Ahmadi Y, Fard JK, Ghafoor D, Eid AH, Sahebkar A. Paradoxical effects of statins on endothelial and cancer cells: the impact of concentrations. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12935-023-02890-1, PMID 36899388.

Abou Baker DH, Abbas HS. Antimicrobial activity of biosynthesized Cuo/Se nanocomposite against Helicobacter pylori. Arab J Chem. 2023;16(9):105095. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105095.

Moriasi G, Ngugi M, Mwitari P, Omwenga G. Cytotoxicity antiprostate cancer effects and phytochemical composition of the dichloromethane stem bark extract of Acacia gerrardii (Benth.). Next Res. 2025;2(1):100167. doi: 10.1016/j.nexres.2025.100167.

Wlodkowic D, Skommer J, Darzynkiewicz Z. Flow cytometry based apoptosis detection. Apoptosis: methods and protocols. 2nd ed; 2009. p. 19-32.

Sil S, Roy UK, Biswas S, Mandal P, Pal K. A study to compare hypolipidemic effects of Allium sativum (Garlic) alone and in combination with atorvastatin or ezetimibe in experimental model. Serbian Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2021;22(1):11-9. doi: 10.2478/sjecr-2020-0058.

Gadhave D, Tupe S, Tagalpallewar A, Gorain B, Choudhury H, Kokare C. Nose to brain delivery of amisulpride loaded lipid based poloxamer gellan gum nanoemulgel: in vitro and in vivo pharmacological studies. Int J Pharm. 2021 Sep 25;607:121050. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121050, PMID 34454028.

Stanisz B, Kania L. Validation of HPLC method for determination of atorvastatin in tablets and for monitoring stability in solid phase. Acta Pol Pharm. 2006;63(6):471-6. PMID 17438862.

Kumar T, Panigrahi B, Nariya M, Thakar A. Pharmacokinetic analysis of Tulasi Swarasadi Taila administered through Nasya (therapeutic nasal administration) and oral route in albino rats. AYU (An Int Q J Res Ayurveda). 2023;44(3):107-13. doi: 10.4103/ayu.ayu_366_21.

Seo YB, Kim JH, Song JH, Jung W, Nam KY, Kim N. Safety and pharmacokinetic comparison between fenofibric acid 135 mg capsule and 110 mg enteric coated tablet in healthy volunteers. Transl Clin Pharmacol. 2023;31(2):95-104. doi: 10.12793/tcp.2023.31.e7, PMID 37440778.

Omar SH, Osman R, Mamdouh W, Abdel Bar HM, Awad GA. Bioinspired lipid-polysaccharide modified hybrid nanoparticles as a brain-targeted highly loaded carrier for a hydrophilic drug. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;165(A):483-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.170, PMID 32987085.

Sahil S, Bodh S, Verma P. Spirulina platensis: a comprehensive review of its nutritional value antioxidant activity and functional food potential. J Cell Biotechnol. 2024;10(2):159-72. doi: 10.3233/JCB-240151.

Nikolova K, Gentscheva G, Gyurova D, Pavlova V, Dincheva I, Velikova M. Metabolomic profile of Arthrospira platensis from a Bulgarian bioreactor a potential opportunity for inclusion in dietary supplements. Life (Basel). 2024;14(2):174. doi: 10.3390/life14020174, PMID 38398682.

Begum N, Qi F, Yang F, Khan QU, Faizan FQ, Fu Q. Nutritional composition and functional properties of a platensis derived peptides: a green and sustainable protein rich supplement. Processes. 2024;12(11):2608. doi: 10.3390/pr12112608.

Cai Z, Lei X, Lin Z, Zhao J, Wu F, Yang Z. Preparation and evaluation of sustained release solid dispersions co-loading gastrodin with borneol as an oral brain targeting enhancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2014;4(1):86-93. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2013.12.012, PMID 26579369.

Banks WA, Sharma P, Bullock KM, Hansen KM, Ludwig N, Whiteside TL. Transport of extracellular vesicles across the blood brain barrier: brain pharmacokinetics and effects of inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4407. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124407, PMID 32575812.

Xia HM, Su LN, Guo JW, Liu GM, Pang ZQ, Jiang XG. Determination of vinpocetine and its primary metabolite apovincaminic acid in rat plasma by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2010;878(22):1959-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.05.029, PMID 20561830.

Danaei M, Dehghankhold M, Ataei S, Hasanzadeh Davarani F, Javanmard R, Dokhani A. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(2):57. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10020057, PMID 29783687.

Malviya V. Preparation and evaluation of emulsomes as a drug delivery system for bifonazole. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 2021;55(1):86-94. doi: 10.5530/ijper.55.1.12.

Vyas SP, Subhedar R, Jain S. Development and characterization of emulsomes for sustained and targeted delivery of an antiviral agent to liver. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006;58(3):321-6. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.3.0005, PMID 16536898.

Ucisik MH, Sleytr UB, Schuster B. Emulsomes meet S-layer proteins: an emerging targeted drug delivery system. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2015;16(4):392-405. doi: 10.2174/138920101604150218112656, PMID 25697368.

Clementino AR, Pellegrini G, Banella S, Colombo G, Cantu L, Sonvico F. Structure and fate of nanoparticles designed for the nasal delivery of poorly soluble drugs. Mol Pharm. 2021;18(8):3132-46. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.1c00366, PMID 34259534.

Tang Q. Structure and rheological properties of airway mucus and counterion condensation around charged nanoparticles. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2021. doi: 10.17615/jf89-br13.

Knudsen KB, Northeved H, Ek PK, Permin A, Andresen TL, Larsen S. Differential toxicological response to positively and negatively charged nanoparticles in the rat brain. Nanotoxicology. 2014;8(7):764-74. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2013.829589, PMID 23889261.

Dunnhaupt S, Kammona O, Waldner C, Kiparissides C, Bernkop Schnurch A. Nano-carrier systems: strategies to overcome the mucus gel barrier. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015 Oct;96:447-53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.01.022, PMID 25712487.

Dante S, Petrelli A, Petrini EM, Marotta R, Maccione A, Alabastri A. Selective targeting of neurons with inorganic nanoparticles: revealing the crucial role of nanoparticle surface charge. ACS Nano. 2017;11(7):6630-40. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b00397, PMID 28595006.

Dudhipala N, Veerabrahma K. Candesartan cilexetil loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for oral delivery: characterization pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation. Drug Deliv. 2016;23(2):395-404. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.914986, PMID 24865287.

Xu Q, Nakajima M, Liu Z, Shii T. Soybean based surfactants and their applications. In: Ng TB, editor. Soybean applications and technology. InTech; 2011. p. 341-64. doi: 10.5772/15261.

Aldawsari HM, Ahmed OA, Alhakamy NA, Neamatallah T, Fahmy UA, Badr Eldin SM. Lipidic nano-sized emulsomes potentiates the cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of raloxifene hydrochloride in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells: factorial analysis and in vitro anti-tumor activity assessment. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(6):783. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13060783, PMID 34073780.

Sultana S, Alzahrani N, Alzahrani R, Alshamrani W, Aloufi W, Ali A. Stability issues and approaches to stabilised nanoparticles based drug delivery system. J Drug Target. 2020;28(5):468-86. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2020.1722137, PMID 31984810.

Helmy HS, El Sahar AE, Sayed RH, Shamma RN, Salama AH, Elbaz EM. Therapeutic effects of lornoxicam loaded nanomicellar formula in experimental models of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:7015-23. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S147738, PMID 29026298.

Salama AH, Abdelkhalek AA, Elkasabgy NA. Etoricoxib loaded bio-adhesive hybridized polylactic acid based nanoparticles as an intra-articular injection for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Int J Pharm. 2020 Mar 30;578:119081. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119081, PMID 32006623.