Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 139-145Original Article

IN VITRO COMPARATIVE EFFECTS OF BIOSIMILAR AND REFERENCE BEVACIZUMAB ON OXIDATIVE STRESS, INFLAMMATION, AND CYTOTOXICITY IN RETINAL PIGMENT EPITHELIAL CELLS

PUSSADEE PAENSUWAN1, ROSSUKON KHOTCHARRAT2, WANACHAT THONGSUK1, KANIN LUANGSAWANG2*

1Department of Optometry, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand-65000, Asia. 2Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University Hospital, Phitsanulok, Thailand-65000, Asia

*Corresponding author: Kanin Luangsawang; *Email: kaninl@nu.ac.th

Received: 25 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 30 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: To compare the effects of the bevacizumab biosimilar (bevacizumab-awwb, MVASI®) and reference bevacizumab (Avastin®) on oxidative stress, inflammation, and cytotoxicity in human retinal pigment epithelial (ARPE-19) cells.

Methods: ARPE-19 cells were treated with clinically relevant concentrations of bevacizumab-awwb or reference bevacizumab (0.313 and 0.625 mg/ml) for 24 h. Cell viability was assessed using Alamar blue assay and apoptosis was analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/PI flow cytometry. Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was evaluated by CMH2DCFDA staining and fluorescence quantification. Proinflammatory cytokine secretion (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) was measured using ELISA. Expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (Erk1/2) were determined by capillary-based Western blotting.

Results: Both bevacizumab-awwb and reference bevacizumab had no significant effects on cell viability or apoptosis induction relative to untreated controls (P>0.05), indicating preserved membrane integrity and absence of cytotoxicity after 24 h exposure. ROS production and secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α remained unchanged, suggesting no oxidative or inflammatory response. Notably, bevacizumab-awwb treatment upregulated Nrf2 expression and Erk1/2 phosphorylation, indicating activation of antioxidant-related signaling pathways.

Conclusion: These findings indicate that a clinical dose of bevacizumab-awwb, comparable to its reference biologic, does not induce oxidative stress or inflammation in ARPE-19 cells. Furthermore, it may contribute to oxidative stress modulation through increased Nrf2 expression. Collectively, these results support the use of bevacizumab-awwb as a safe, non-toxic alternative for intravitreal therapy in ophthalmic diseases.

Keywords: Bevacizumab-awwb, Retina, Biosimilar, Inflammation, Oxidative stress

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54738 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Oxidative stress (OS) is a key pathological factor in the development and progression of many retinal diseases, including diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), myopia, retinal vein occlusion (RVO), retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) [1, 2]. OS arises from an imbalance between the generation and elimination of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to the disruption of cellular homeostasis, inflammation, and progressive retinal damage [1, 3]. OS is also known to upregulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression, which plays a critical role in abnormal angiogenesis in the retina [4, 5]. Notably, VEGF itself can induce intracellular ROS accumulation through activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and mitochondrial pathways, further exacerbating oxidative damage and angiogenesis in retinal tissues [6].

Anti-VEGF therapies are widely administered via intravitreal injection in the management of neovascular retinal diseases [4, 7, 8]. Among these therapies, intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin®), a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting VEGF, was originally approved by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2004 for intravenous administration in the treatment of colorectal cancer treatment [9]. Since 2005, it has been widely used off-label for neovascular AMD due to its cost-effectiveness and efficacy comparable to other anti-VEGF agents [10-12]. The primary mechanism of these anti-VEGF drugs involves inhibiting VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. Moreover, it has been shown that anti-VEGF therapy may contribute to OS attenuation by lowering VEGF-A levels, thereby reducing ROS generation [13]. However, the reduction of VEGF-A may adversely affect retinal cell survival under certain conditions, raising safety concerns for anti-VEGF use [13, 14]. Given the therapeutic potential of the anti-VEGF drugs exhibiting antioxidant and anti-angiogenic properties, efforts have been devoted to developing nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems aimed at enhancing pharmacological efficacy and promoting cellular viability [15]. These findings underscore the increasing prominence of anti-VEGF therapies in the management of retinal diseases. Despite their clinical efficacy, the high cost of biologic treatments presents a substantial barrier to treatment accessibility [16]. Therefore, evaluating both the efficacy and safety of biosimilars compared to their reference products (RPs) is important for the treatment of ocular diseases.

Bevacizumab-awwb (MVASI®), the first FDA-approved biosimilar of the licensed RP bevacizumab, was authorized in 2017 for use in various cancers [17]. The clinical and biological properties of bevacizumab-awwb closely resemble those of the RP, with no clinically meaningful differences [18]. Despite its approval for systemic use, the effects of bevacizumab-awwb in ocular applications, particularly its impact on oxidative stress and inflammation in retinal cells, remain insufficiently characterized. Given its cost advantage over reference bevacizumab, it is essential to explore how bevacizumab-awwb influences ROS generation, inflammatory responses, and cellular antioxidative defense mechanisms, thereby supporting its potential as a viable alternative for intravitreal therapy.

Several studies have suggested that VEGF plays a crucial role in a positive feedback loop that enhances antioxidative defense system through the upregulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (Erk1/2) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) [19]. Specifically, Erk1/2 facilitates the nuclear translocation of Nrf2, which subsequently induces the expression of key antioxidant enzymes, including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), thereby mitigating oxidative damage and promoting cellular protection [20]. However, excessive VEGF expression may contribute to cellular stress under pathological conditions. Therefore, elucidating the interaction between the Erk1/2 and Nrf2 signaling in the context of VEGF inhibition may provide important insights into their potential roles in retinal cell homeostasis and therapeutic efficacy.

In this study, we evaluated the comparative effects of bevacizumab-awwb and its reference product on oxidative stress, inflammation, and cytotoxicity in human retinal pigment epithelial (ARPE-19) cells. Specifically, we examined ROS production, apoptosis, proinflammatory cytokine secretion, and the activation of Nrf2 and Erk1/2 pathways. These insights are essential for determining whether bevacizumab-awwb induces stress-related cellular responses in retinal cells, thereby contributing to the growing evidence base supporting its clinical application in ophthalmology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

ARPE-19 cell lines (ATCC CRL-2302, RRID: CVCL 0145, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were purchased from Biomedia (Thailand) CO., Ltd., Lot: 70039146, in February 2022. Cells were authenticated using STR in December 2020. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F12 (DMEM/F12, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The medium was changed three times a week or upon observable color change.

Bevacizumab and bevacizumab-awwb

Bevacizumab Lot: B7263 was purchased from Sawanpracharak Hospital in September 2022, and Bevacizumab-awwb (MVASI®) Lot: 1146995 was purchased from Sangsiri Medical. CO., LTD. in August 2022. The concentration of 0.313 mg/ml was selected to represent the estimated clinical intravitreal concentration of bevacizumab, while 0.625 mg/ml was included to evaluate potential effects at twice the clinical concentration.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined by assessing the reduction of Alamar Blue from its resorufin form to resazurin, which indicates cellular viability. ARPE-19 cells were seeded at a density of 5x103 cells per well. Following a 24 h incubation period, ARPE-19 cells were allocated into the control group (untreated) and experimental group (treated), receiving either 0.313 or 0.625 mg/ml of bevacizumab-awwb or the reference bevacizumab for an additional 24 h. After medium removal, 100 μl of DMEM and 10 μl of Deep Blue Cell Viability™ reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Milano, Italy) were added to each well. The cells underwent a further incubation for 3 h at 37 °C. Cell viability was quantified by measuring the relative fluorescence units (RFU) at an excitation/emission (Ex/Em) wavelength of 530/590 nm using a SpectraMax iD3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Analysis was based on data from three independent experiments. The percentage of cell viability (% cell viability) was calculated using the formula below:

% cell viability = (RFU treated/RFU untreated) × 100

Following ISO 10993-5: 1999 (Biological evaluation of medical devices; Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity), cytotoxicity is identified when the survival rate of test cells falls below 70%.

Cell apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis assay used the Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). ARPE-19 cells were treated with specified concentrations of bevacizumab-awwb and bevacizumab or left untreated for 24 h. After the incubation, cells were harvested and stained with FITC-conjugated Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. The stained cells were analyzed using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA). The proportions of cells in different apoptosis stages—viable (Annexin V-/PI−), early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI−), late apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI+), and necrotic (Annexin V−/PI+)—were quantified as percentages using CellQuestPro software (Becton Dickinson).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation assessment

Cells were cultured in an 8-well chamber slide for 24 h. Oxidative stress was induced by exposing the cells to specified drugs for 60 min. Intracellular ROS generation was quantified using a 5μM chloromethyl derivative of 2′,7′ dichlorodihydrofluorescein (CMH2DCFDA) supplied by ThermoFisher Scientific, following the manufacturer’s instructions for 20 min. Cells exhibiting green fluorescence were examined using a 20× objective lens on a fluorescence microscope (Nikon), employing NIS-Elements D software for image analysis. Quantification of CM-H2DCFDA–stained cells was determined and calculated into mean correlated total cell fluorescence (CTCF) using Image J software (version 1.46r, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html) .In brief, fluorescence images of CM-H2DCFDA–stained cells were first converted to 8-bit grayscale. The background signal was removed by selecting a blank area outside the cell region and using the “subtract background” function with a rolling ball radius of 50 pixels. For each image, a uniform region of interest (ROI) was manually drawn around each cell or cell cluster. The following parameters were measured: Integrated Density (IntDen), Area, and mean Gray Value. Corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) was calculated using the formula:

CTCF = Integrated Density − (Area of ROI × mean fluorescence of background)

Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). All images were processed under identical acquisition settings and exposure times to ensure consistency across samples.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines secretion measurement

To assess the inflammatory response induced by bevacizumab-awwb and reference bevacizumab, the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), were quantified using human-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) by the manufacturer’s instructions. Following 24 h exposure of cells to 0.313 and 0.625 mg/ml of each agent, culture supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove cellular debris. The clarified supernatants were subsequently analyzed using ELISA kits. Cytokine concentrations were determined by interpolation from a standard curve generated for each analyte. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and statistical reliability.

Capillary-based western blot analysis

For the ARPE-19 Cells blot analysis, cells underwent a 24 h treatment with specified drugs. Protein lysates were subsequently extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Milano, Italy) enhanced with a phosphatase/protease inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher Scientific) and maintained on ice for 15 min. Protein concentrations were determined via the Bradford Colorimetric assay (BCA, ThermoFisher Scientific), adhering to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Protein expression analysis employed a capillary-based Western blot system (Simple Western™, Protein Simple, Santa Clara, CA, USA). In this process, protein samples were diluted, and an equal amount of total protein from each sample was assessed for protein expression using the WES system (Protein Simple). The following primary antibodies were used for protein detection: anti-Nrf2 (rabbit mAb, clone D1Z9C, catalog #12721; dilution 1:200) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (rabbitm Ab, clone D13.14.4E, catalog #4370; dilution 1:200) (Cell Signaling), anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (rabbit monoclonal, clone D16H11, catalog #5147; dilution 1:600)(Cell Signaling). Working dilutions were prepared in the antibody diluent provided with the WES system according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Band intensities were quantified using Compass for SW version 6.2.0 software (Protein Simple).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3), representing independent biological replicates, to ensure reproducibility and consistency across experimental conditions. All experimental data were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). The Shapiro–Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of distribution. For datasets with normal distribution, statistical comparisons between two groups were performed using Student’s T-test and One-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was used for multiple group comparisons. In cases where data deviated from normality, the Kruskal–Wallis’s test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, was used as a non-parametric alternative. The statistical analyses were performed using Prism 10 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant at P values less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Cell viability

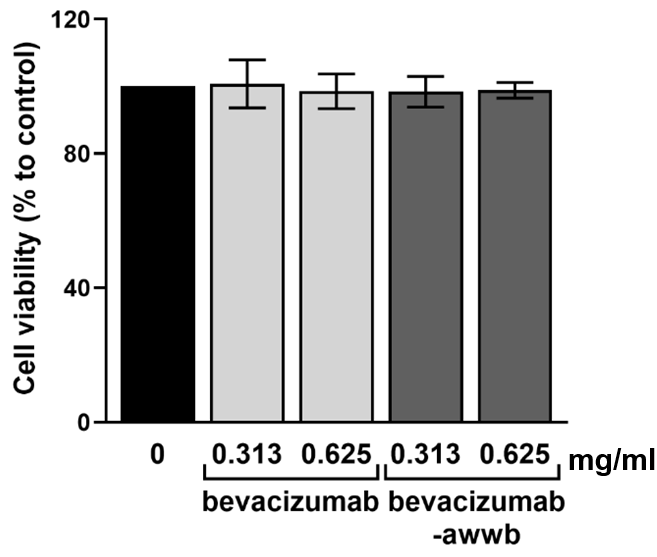

Using the Alamar blue assay, we initially evaluated the cytotoxic effects of bevacizumab-awwb and reference bevacizumab on ARPE-19 cells at clinically relevant concentrations (0.313 and 0.625 mg/ml). After exposure to both therapeutic agents, there was no statistically significant difference in cell viability was observed (P>0.05) (fig. 1). The results indicated a high percentage of viable cells in the treated groups compared to the untreated control. These findings suggest that bevacizumab-awwb, at clinically relevant doses, does not affect the biological status of ARPE-19 cells, consistent with the effect of reference bevacizumab.

Cell apoptosis

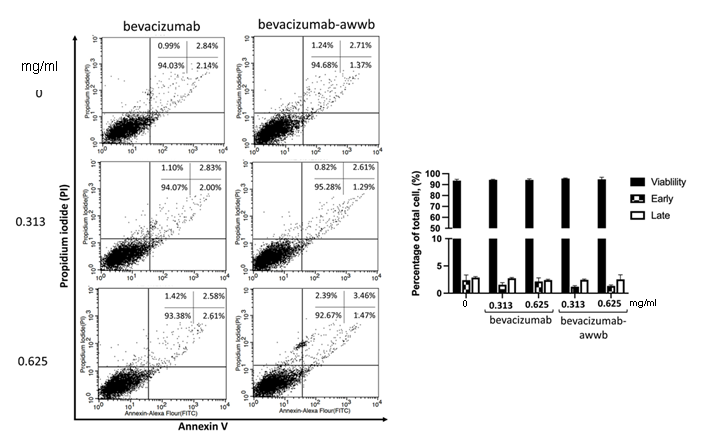

The high viability of ARPE-19 cells after exposure to bevacizumab-awwb and bevacizumab suggests that the integrity of the cell membrane remains intact, thereby preventing the induction apoptosis. The effect of bevacizumab-awwb and bevacizumab on the progression of apoptosis in ARPE-19 cells was examined by quantifying Annexin V-and PI-stained cells. After treatment, cells exposed to both drugs demonstrated a predominance of viability, with a high percentage of cells negative for both Annexin V and PI staining (fig. 2). Moreover, there was no significant difference in the rates of early and late apoptosis between treated cells and untreated controls, indicating that clinically relevant doses of bevacizumab-awwb and bevacizumab do not compromise the cell membrane integrity of APRE-19 cells, thereby preserving cell viability.

Fig. 1: Effect of 0.313 mg/ml and 0.625 mg/ml of bevacizumab and bevacizumab-awwb on ARPE-19 cell viability after 24 h of treatment. Neither clinically relevant concentrations of bevacizumab nor bevacizumab-awwb affect cell viability

Fig. 2: The effect of bevacizumab-awwb and bevacizumab on ARPE-19 cell apoptosis. Cells were treated with bevacizumab-awwb and bevacizumab for 24 h. Then, cells were probed with Annexin V (5 μl) and PI (5 μl). The percentage of drug-induced apoptotic cells is shown in the graph representing the mean±SD. Data are representative of three independent experiments

ROS production

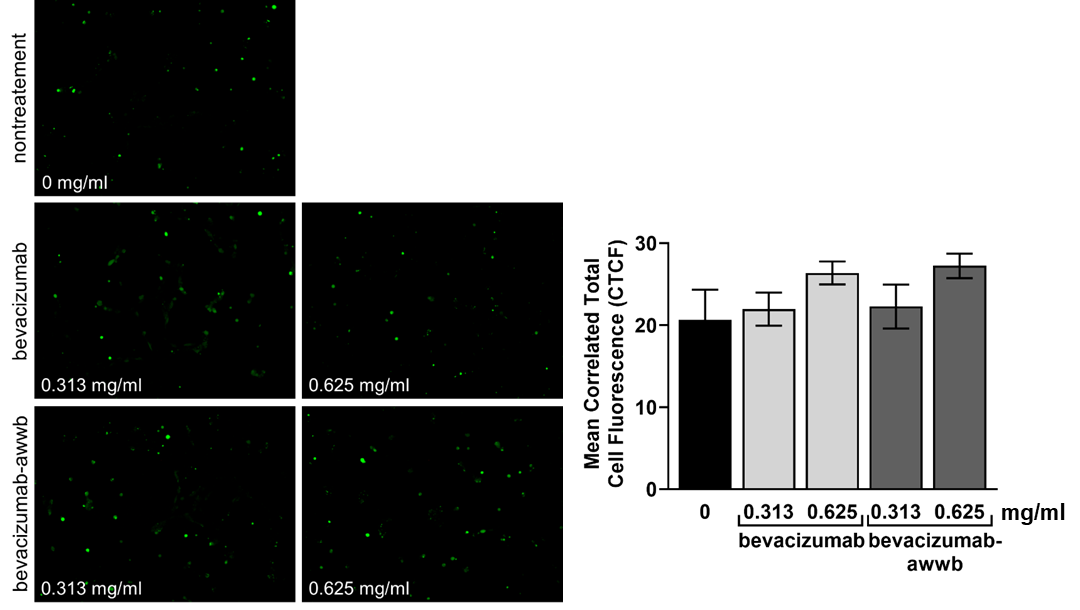

The accumulation of intracellular ROS is a key contributor to oxidative stress and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various age-related, vision-threatening ocular diseases [21]. To evaluate whether bevacizumab-awwb and bevacizumab influence ROS generation, ARPE-19 cells were treated with each agent and subsequently stained with CM-H₂DCFDA. As shown in fig. 3, both drugs induced a concentration-dependent trend toward increased ROS-associated fluorescence. However, the fluorescence intensity did not differ significantly from that of untreated controls. These results suggest that neither bevacizumab-awwb nor bevacizumab promotes intracellular ROS accumulation, indicating a lack of oxidative stress induction in retinal pigment epithelial cells.

Fig. 3: Generation of intracellular ROS level. Cells were treated with bevacizumab or bevacizumab-awwb for 60 min. The intracellular ROS accumulation was measured by the fluorescence probe CMH2DCFDA. The fluorescence images were taken under a fluorescence microscope. The means of correlated total cell fluorescence in each group were quantified using ImageJ software. Data is represented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments

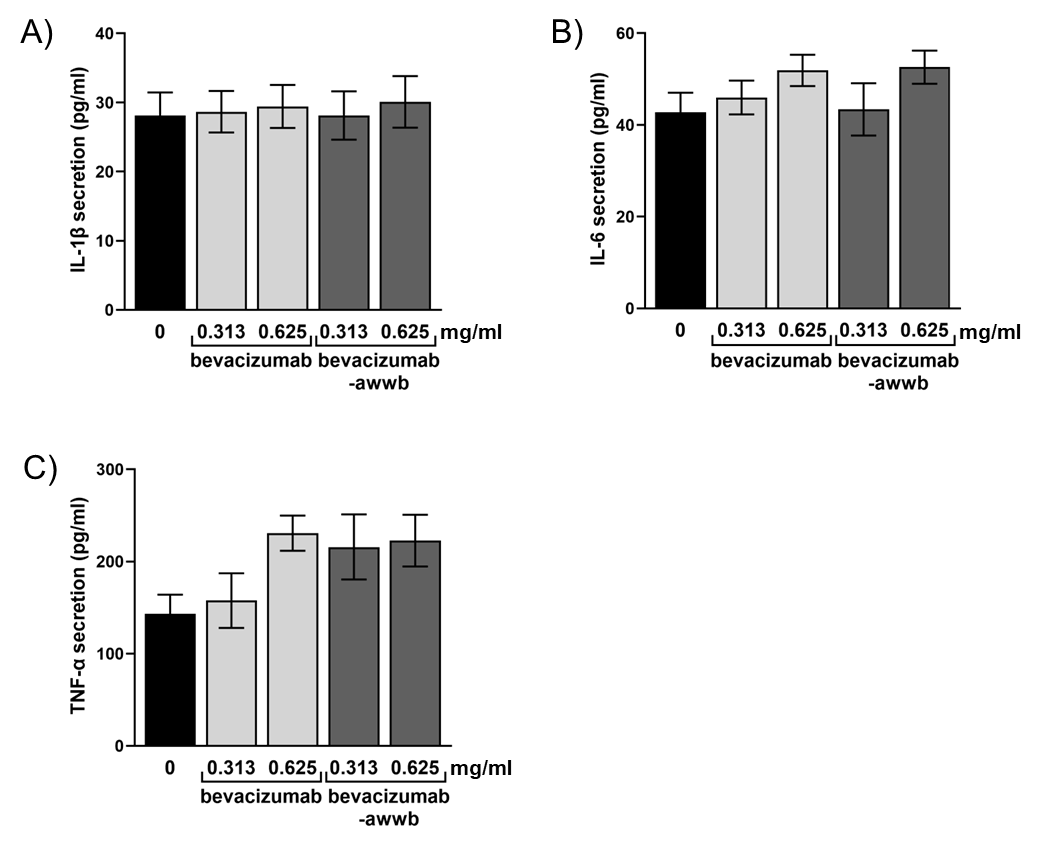

Pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion

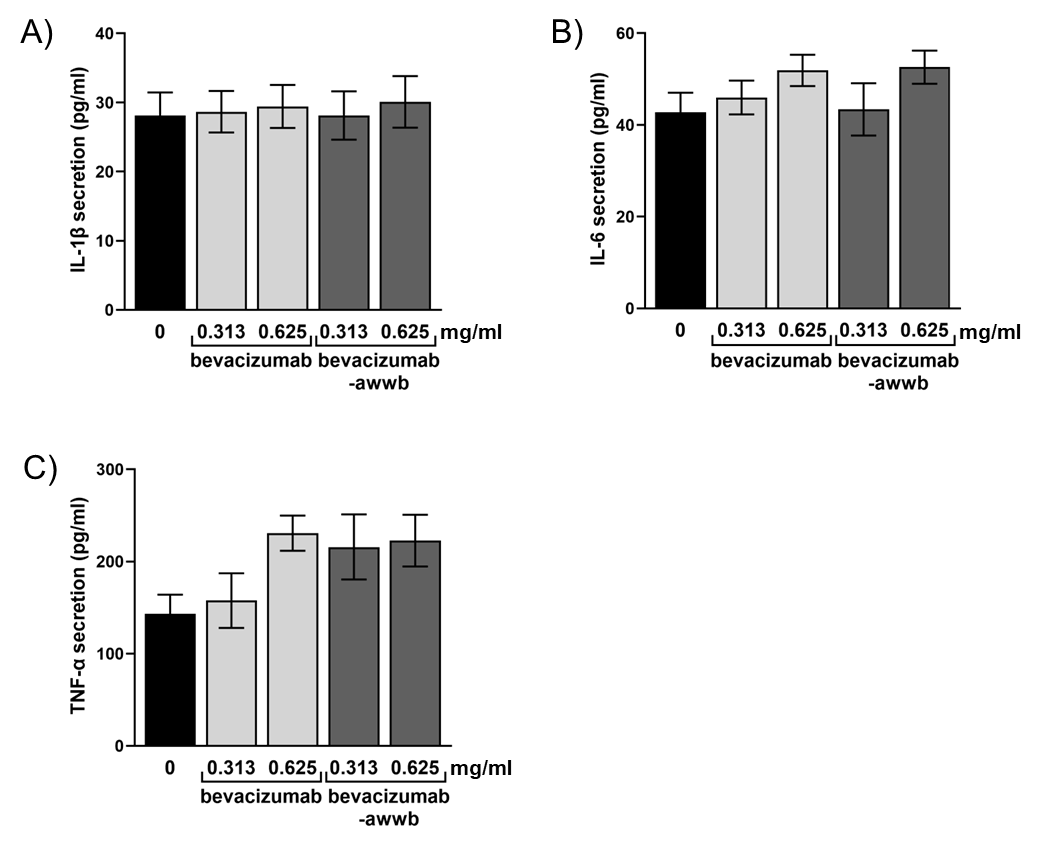

The analysis demonstrated that treatment with bevacizumab-awwb did not result in a statistically significant alteration in the levels of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, compared to untreated controls (P>0.05) (fig. 4). These results suggest that a clinically relevant dose of bevacizumab-awwb does not induce cytokine production. Although a slight increase in cytokine levels was observed at higher drug concentrations, this change was not statistically significant. Therefore, the findings indicate that bevacizumab-awwb does not provoke a pronounced inflammatory response in cells, consistent with the inflammatory response profile observed with bevacizumab treatment.

Fig. 4: Pro-inflammatory cytokines production. Cells were treated with bevacizumab or bevacizumab-awwb for 24 h, and cytokine release was examined using ELISA. (A) IL-1β level, (B) IL-6 level, and (C) TNF-α level. Results were expressed as mean±SD of three separate experiments

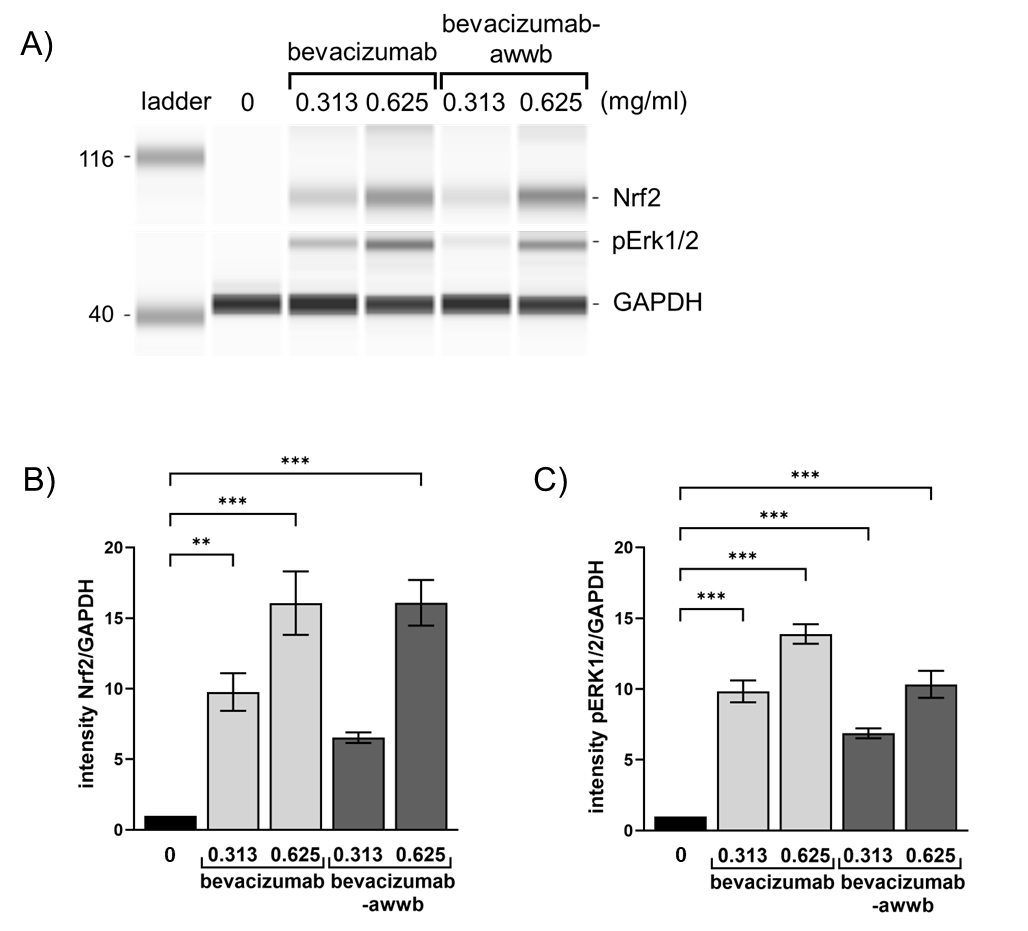

Western blot analysis

The expression of anti-inflammatory-related proteins following cell treatment was assessed via Western blot analysis to further elucidate the mechanisms by which bevacizumab-awwb reduced proinflammatory cytokine release. As shown in fig. 5, treatment with bevacizumab-awwb induced a significant dose-dependent upregulation of Nrf2 expression compared to untreated controls. Moreover, a significant increase in Erk1/2 protein phosphorylation was observed following drug exposure. These findings demonstrate that bevacizumab-awwb effectively mitigates ROS accumulation and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion by promoting Nrf2 and pErk1/2 activation, indicating an efficacy comparable to that of bevacizumab.

Fig. 5: Capillary electrophoresis (CE) based Western blot images. Cells were treated with bevacizumab or bevacizumab-awwb for 24 h. Cell lysates were collected and subjected to capillary-based Western blotting by probing with anti-Nrf2, anti-pErk1/2 and anti-GAPDH antibodies. (A) Gel-like image viewed from Western blot assay. (B, C) value in A, quantifying protein band intensity, are presented as the ratio of Nrf2 or pErk1/2 to corresponding GAPDH relative to the protein of choice expressed in control ARPE-19. Data are representative of three experiments (mean±SD). **P<0.01, *** P<0.001

DISCUSSION

Biosimilars are designed to be highly similar to their reference products in terms of safety, purity, and potency, with no clinically meaningful differences in therapeutic outcomes [22]. They may exhibit minor variations in clinically inactive components, such as stabilizers and buffers, which do not affect clinical safety or efficacy. In the United States, four bevacizumab biosimilars have been approved for intravenous oncologic applications, namely bevacizumab-awwb (MVASI®), bevacizumab-bvzr (Zirabev®), bevacizumab-maly (Almysys®), and bevacizumab-adcd (Vegzelma®), with bevacizumab-awwb being the first FDA-approved bevacizumab biosimilar for this indication [23]. In clinical settings, comparable safety and efficacy profiles have been observed between intravenous bevacizumab and its biosimilar, bevacizumab-awwb (MVASI®) [24].

In this study, we evaluated the effects of bevacizumab-awwb (a bevacizumab biosimilar) in comparison to reference bevacizumab (RP) on cell viability, apoptosis, and cellular biological changes, including ROS production and proinflammatory cytokine induction in ARPE-19 cells. Our findings revealed that a clinically relevant dose of bevacizumab-awwb does not adversely affect the survival rate or cell membrane integrity of ARPE-19 cells, mirroring the outcomes observed with the reference product, as evidenced by a high number of viable cells and low incidence of apoptotic cells.

Numerous studies have previously reported that human retinal pigment epithelial cells remain unaffected by bevacizumab [23, 25-27]. This study corroborates those findings, demonstrating similar cell viability with the clinically relevant concentrations of bevacizumab and bevacizumab-awwb. It employed standard assays to ascertain the relative safety of bevacizumab-awwb in this in vitro model.

Diabetic macular edema (DME) and retinal vein occlusion (RVO) are frequently associated with elevated vitreous cytokine levels, a phenomenon that is gradually attenuated through intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy [28-30]. Several previous studies have reported inconsistent inflammatory responses following anti-VEGF treatment in ocular cells. For instance, some investigations have shown that bevacizumab or other anti-VEGF agents can induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α in retinal pigment epithelial or endothelial cells, particularly under stress conditions such as high-glucose exposure or hypoxia. In contrast, our findings demonstrate that neither bevacizumab-awwb nor bevacizumab elicited the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in ARPE-19 cells under basal conditions. This observation is consistent with previous reports suggesting that bevacizumab biosimilars exhibit no clinically significant differences in immunogenicity compared to their reference biologics [18]. These discrepancies in cytokine responses may arise from variations in experimental conditions, as our study assessed the drug's effect under basal conditions without additional stress induction. While bevacizumab biosimilars are designed to mimic the mechanism of action of the reference product, variability in immune response and cytokine production may still occur at the cellular level.

Although our findings demonstrate that bevacizumab-awwb treatment upregulates Nrf2 expression and promote Erk1/2 phosphorylation in ARPE-19 cells, the underlying mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated. A plausible explanation is that VEGF inhibition transiently elevates intracellular ROS levels, which serve as signaling molecules facilitating the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 [19]. This proposed mechanism aligns with our observations, in which both bevacizumab and bevacizumab-awwb exhibited a trend toward increased ROS levels, although the differences were not statistically significant. Nevertheless, even modest ROS elevation may serve as a sufficient intracellular signal to activate Nrf2, as evidenced by the upregulation of Nrf2 expression observed in our Western blot analysis. Upon nuclear translocation, Nrf2 binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs), inducing the transcription of cytoprotective genes such as HO-1, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and NQO1, which collectively act to neutralize ROS and limit oxidative damage [31-34]. Taken together, these findings suggest that both agents may enhance the antioxidant defense mechanisms of RPE cells through Nrf2-mediated signaling pathways triggered by VEGF inhibition.

Furthermore, we observed that cells treated with the drugs exhibited a significant and dose-dependent increase in pErk1/2 expression. This suggests that bevacizumab-awwb administration may affect the expression of Nrf2 protein through the accompanying upregulation of pErk1/2 expression in ARPE-19 cells [31, 32]. Together, these results are consistent with the observation that both drugs did not induce ROS accumulation or proinflammatory cytokines release, possibly due to shared specific components or mechanisms of action [11-12]. Considering the accumulation of oxidative damage and chronic inflammation characteristic of many retinal diseases, the induction of Nrf2 expression by bevacizumab-awwb may offer cellular protection against oxidative stress in retinal cells [32].

Nevertheless, the current assessment of cell viability is limited to a single 24 h exposure period and two drug concentrations. To comprehensively evaluate the safety profile of bevacizumab-awwb, future studies should incorporate prolonged exposure durations and a broader range of clinically relevant concentrations to assess potential long-term cytotoxicity and biological effects [11]. Furthermore, conclusions regarding enhanced antioxidant capacity remain confined to upstream pathway activation. To substantiate these findings, future studies should include quantitative assessments of Nrf2-regulated antioxidant enzymes, such as HO-1, NQO1, and GPx, to determine whether these molecular changes translate into functional antioxidant protection at the protein level [31].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study provided comparative in vitro nonclinical data between bevacizumab-awwb (a biosimilar) and bevacizumab (RP) on ARPE-19 cells. Similar to the bevacizumab reference, we found that the bevacizumab-awwb exhibited no differences in safety profile. Bevacizumab-awwb did not disturb the viability of ARPE-19 cells or induce cell apoptosis following exposure to the drug. Furthermore, bevacizumab-awwb might diminish ROS generation and proinflammatory cytokines secretion through upregulation of Nrf2 transcription factor protein expression, accompanied by pErk1/2 expression. Our data suggests that the biosimilar bevacizumab-awwb is non-toxic to ARPE-19 cells and elicits an inflammatory response comparable to that of the reference biologics, bevacizumab. Nevertheless, these findings are based on an in vitro models; further validation in preclinical animal studies or with patient-derived retinal tissues is necessary to confirm their clinical relevance and support potential translational applications.

FUNDING

This research was funded by National Science, Research, and Innovation Fund (NSRF), Grant number R2566B080”.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, K. L.; methodology, K. L. and P. P.; validation, K. L. and P. P.; formal analysis, K. L. and P. P.; investigation, K. L. and P. P.; resources, K. L. and P. P.; data curation, K. L.; writing—original draft preparation, K. L., P. P., R. K., and W. T.; writing—review and editing, K. L. and P. P.; visualization, K. L. and P. P.; supervision, K. L.; project administration, K. L.; funding acquisition, P. P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Shu DY, Chaudhary S, Cho KS, Lennikov A, Miller WP, Thorn DC. Role of oxidative stress in ocular diseases: a balancing act. Metabolites. 2023;13(2):187. doi: 10.3390/metabo13020187, PMID 36837806.

Chan TC, Wilkinson Berka JL, Deliyanti D, Hunter D, Fung A, Liew G. The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis and treatment of retinal diseases. Exp Eye Res. 2020;201:108255. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108255, PMID 32971094.

Ung L, Pattamatta U, Carnt N, Wilkinson Berka JL, Liew G, White AJ. Oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species: a review of their role in ocular disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017;131(24):2865-83. doi: 10.1042/CS20171246, PMID 29203723.

Rossino MG, Lulli M, Amato R, Cammalleri M, Monte MD, Casini G. Oxidative stress induces a VEGF autocrine loop in the retina: relevance for diabetic retinopathy. Cells. 2020;9(6):1452. doi: 10.3390/cells9061452, PMID 32545222.

I GJ, Sd I, KK, KP, NS MA. Comparative study of anti-angiogenic activities of medicinal plants and their therapeutic potential in angiogenesis-dependent disorders. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;9(1):219-22.

Ushio Fukai M, Nakamura Y. Reactive oxygen species and angiogenesis: NADPH oxidase as target for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2008;266(1):37-52. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.044, PMID 18406051.

Chen R, Lee C, Lin X, Zhao C, Li X. Novel function of VEGF-B as an antioxidant and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Res. 2019;143:33-9. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.03.002, PMID 30851357.

Khandelwal G, Kumar K, Dubey A, Som V. Evaluation of visual outcome and clinical response of intravitreal anti VEGF agents in various indications. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2024;17(1):53-6. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2024.v17i1.49123.

Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2335-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691, PMID 15175435.

Comparison of Age related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) Research Group, Martin DF, Maguire MG, Fine SL, Ying GS, Jaffe GJ. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two year results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(7):1388-98. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.053, PMID 22555112.

Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, Jampol LM, Bressler NM, Bressler SB. Aflibercept bevacizumab or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: two-year results from a comparative effectiveness randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1351-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.02.022, PMID 26935357.

Hykin P, Prevost AT, Vasconcelos JC, Murphy C, Kelly J, Ramu J. Clinical effectiveness of intravitreal therapy with ranibizumab vs aflibercept vs bevacizumab for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(11):1256-64. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.3305, PMID 31465100.

Ranjbar M, Brinkmann MP, Zapf D, Miura Y, Rudolf M, Grisanti S. Fc receptor inhibition reduces susceptibility to oxidative stress in human RPE cells treated with bevacizumab but not aflibercept. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;38(2):737-47. doi: 10.1159/000443030, PMID 26871551.

Dithmer M, Kirsch AM, Grafenstein L, Wang F, Schmidt H, Coupland SE. Uveal melanoma cell under oxidative stress influence of VEGF and VEGF-inhibitors. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2019;236(3):295-307. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-103002, PMID 28376556.

Jiang P, Choi A, Swindle Reilly KE. Controlled release of anti-VEGF by redox-responsive polydopamine nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2020;12(33):17298-311. doi: 10.1039/D0NR03710A, PMID 32789323.

Van Asten F, Michels CT, Hoyng CB, Van Der Wilt GJ, Klevering BJ, Rovers MM. The cost-effectiveness of bevacizumab, ranibizumab and aflibercept for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration a cost-effectiveness analysis from a societal perspective. PLOS One. 2018;13(5):e0197670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197670, PMID 29772018.

Casak SJ, Lemery SJ, Chung J, Fuchs C, Schrieber SJ, Chow EC. FDA’s approval of the first biosimilar to bevacizumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(18):4365-70. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0566, PMID 29743182.

Xu X, Zhang S, Xu T, Zhan M, Chen C, Zhang C. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab biosimilars compared with reference biologics in advanced non-small cell lung cancer or metastatic colorectal cancer patients: a network meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:880090. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.880090, PMID 35865968.

Li L, Pan H, Wang H, Li X, Bu X, Wang Q. Interplay between VEGF and Nrf2 regulates angiogenesis due to intracranial venous hypertension. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37338. doi: 10.1038/srep37338, PMID 27869147.

Johnson JA, Johnson DA, Kraft AD, Calkins MJ, Jakel RJ, Vargas MR. The Nrf2-ARE pathway: an indicator and modulator of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1147:61-9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.036, PMID 19076431.

Nita M, Grzybowski A. The role of the reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in the pathomechanism of the age-related ocular diseases and other pathologies of the anterior and posterior eye segments in adults. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:3164734. doi: 10.1155/2016/3164734, PMID 26881021.

Kumar G, Dsouza H, Menon N, Srinivas S, Vallathol DH, Boppana M. Safety and efficacy of bevacizumab biosimilar in recurrent/ progressive glioblastoma. E Cancer Medical Science. 2021;15:1166. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2021.1166, PMID 33680080.

Malik D, Tarek M, Caceres Del Carpio J, Ramirez C, Boyer D, Kenney MC. Safety profiles of anti-VEGF drugs: bevacizumab ranibizumab, aflibercept and ziv-aflibercept on human retinal pigment epithelium cells in culture. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98Suppl 1:i11-6. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305302, PMID 24836865.

Jin R, Ogbomo AS, Accortt NA, Lal LS, Bishi G, Sandschafer D. Real world outcomes among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated first line with a bevacizumab biosimilar (bevacizumab-awwb). Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2023;15:17588359231182386. doi: 10.1177/17588359231182386, PMID 37360769.

Shokoohi S, Iovieno A, Yeung SN. Effect of bevacizumab on the viability and metabolism of human corneal epithelial and endothelial cells: an in vitro study. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2021;10(8):32. doi: 10.1167/tvst.10.8.32, PMID 34323952.

Chae JB, Rho CR, Shin JA, Lyu J, Kang S. Effects of ranibizumab bevacizumab and aflibercept on senescent retinal pigment epithelial cells. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2018;32(4):328-38. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2017.0079, PMID 30091312.

Luthra S, Narayanan R, Marques LE, Chwa M, Kim DW, Dong J. Evaluation of in vitro effects of bevacizumab (Avastin) on retinal pigment epithelial neurosensory retinal and microvascular endothelial cells. Retina. 2006;26(5):512-8. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000222547.35820.52, PMID 16770256.

Hildebrandt J, Kackenmeister T, Winkelmann K, Dorschmann P, Roider J, Klettner A. Pro-inflammatory activation changes intracellular transport of bevacizumab in the retinal pigment epithelium in vitro. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022;260(3):857-72. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05443-2, PMID 34643794.

Lim JW. Intravitreal bevacizumab and cytokine levels in major and macular branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmologica. 2011;225(3):150-4. doi: 10.1159/000322364, PMID 21150231.

Suzuki Y, Suzuki K, Yokoi Y, Miyagawa Y, Metoki T, Nakazawa M. Effects of intravitreal injection of bevacizumab on inflammatory cytokines in the vitreous with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2014;34(1):165-71. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182979df6, PMID 23851630.

Weng B, Zhang X, Chu X, Gong X, Cai C. Nrf2-Keap1-ARE-NQO1 signaling attenuates hyperoxia-induced lung cell injury by inhibiting apoptosis. Mol Med Rep. 2021;23(3):221. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2021.11860, PMID 33495821.

Loboda A, Damulewicz M, Pyza E, Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development oxidative stress response and diseases: an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(17):3221-47. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2223-0, PMID 27100828.

Li N, Alam J, Venkatesan MI, Eiguren Fernandez A, Schmitz D, Di Stefano E. Nrf2 is a key transcription factor that regulates antioxidant defense in macrophages and epithelial cells: protecting against the proinflammatory and oxidizing effects of diesel exhaust chemicals. J Immunol. 2004;173(5):3467-81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3467, PMID 15322212.

He F, Ru X, Wen T. NRF2, a transcription factor for stress response and beyond. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(13):4777. doi: 10.3390/ijms21134777, PMID 32640524.