Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 302-307Original Article

CASE-CONTROL STUDY OF IMMUNOGLOBULINES AND PANCREATIC ENZYME ALTERATIONS IN COVID-19 IRAQI PATIENTS

ZAHRAA MOHAMMED ALI NAJI¹, LUBNA A. ALZUBAIDI2, IHAB I. AL KHALIFA3*, SHAIMAA M. MOHAMMED⁴

1Baghdad University, College of Pharmacy, Baghdad, Iraq. 2Al-Mustansiriyah University, Collage of Engineering, Department of Environmental Engineering, Baghdad, Iraq. 3Al-Rasheed University College, Pharmacy Department, Baghdad, Iraq. 4Al-Mustaqbal University, Pharmacy College, Babylon, Iraq

*Corresponding author: Ihab I. Al khalifa; *Email: ehab.kh@alrasheedcol.edu.iq

Received: 28 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 29 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: C-reactive and Pancreatic enzymes changes for COVID-19 patients were estimated.

Methods: Eighty individuals of both sexes, age range (28-69 y), with a mean±SE of (46.2±1.7) were included in this study, Group I: COVID-19 patients and Group II Aged matched healthy people as the control group. Venous blood samples were taken for each individual, serum collected and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique (ELISA) was used to estimate the levels of C-reactive protein, lipase, and amylase, and we used a capture chemiluminescence immunoassay for IgM and an indirect chemiluminescence immunoassay for IgG.

Results: The mean serum levels of IgM, IgG, CRP, were significantly higher in the patient group than in the control group (1.7 vs. 0.7 AU/ml, 2.86 vs. 0.27 AU/ml, 7.6 vs. 4 mg/dl) respectively and pancreatic enzymes (lipase, and amylase) were significantly higher in the patient group than in the control group (86 vs. 54U/l, and 66 vs. 39U/l), respectively.

Conclusion, COVID-19 patients have an increased risk of exocrine secretion (lipase and amylase enzymes) and pancreatic damage. This work highlights the importance of pancreatic enzyme (amylase and lipase) estimation in affected patients.

Keywords: Amylase, Lipase, COVID-19, IgG, IgM

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54773 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the cause of the new condition COVID-19 [1]. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic due to its rapid spread outside China, reaching 114 nations [2, 3].

While the respiratory system is the primary target, Moreover, there have been reports of cardiac, hepatic, and renal involvement [4]. The percentage of COVID-19 cases that affect the gastrointestinal system might vary from 3% to 79% [5]. The pancreas is another organ targeted by viruses [1]. A viral infection affects the organ’s exocrine and endocrine functions [5]. Studies on exocrine function have shown that high enzyme levels (hyperamylasemia and hyperlipasemia) are connected with COVID-19, and isolated and uncommon occurrences of acute pancreatitis have also been reported. Because pancreatic insufficiency in individuals with COVID-19 may be one of the factors aggravating the disease’s clinical progression, it warrants close consideration.

Acute pancreatitis, especially in its severe forms and with a proinflammatory response, may be associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 development, which can lead to an increase in inpatient days and a higher mortality rate [5]. This concerns the pancreatic exocrine and endocrine regions respective angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 (ACE-2) receptors [6]. There is insufficient data to establish a definitive causative mechanism of pancreatic injury related to COVID-19. There have been two prominent theories proposed describing the mechanisms of pancreatic damage seen in SARS-CoV-2 infection, includinga direct and an indirect mechanism. The direct mechanism may be explained by studies showing that pancreatic acinar, ductal, and islet cells highly express ACE2 and TMPRSS2 receptors that promote SARS-CoV-2 cell entry, Liu et al. reported that in healthy individuals, the pancreas was found to express higher levels of ACE2 mRNA than in the lungs [7]. Furthermore, a study conducted by Szlachcic et al. used in vitro models of human pancreatic cells to show that SARS-CoV-2 is capable of infecting and actively replicating in these cell types [8]. Indirect pancreatic injury may be induced by the systemic inflammatory and immune responses induced by SARS-CoV-2 and subsequent endothelial cell damage that mediates the leakage of these proinflammatory substances for distribution to various distant tissues, including the pancreas [9, 10]. Microscopic examination of COVID-19 pancreatic tissues at autopsy revealed the expression of entry receptors, severe fatty replacement of acinar cell mass, arteriosclerosis, and fibrosis [11]. During pancreatic inflammation, activated stellate cells release inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, resulting in pancreatic fibrosis. ACE2 downregulation caused by direct viral infection in pancreatic cells may disrupt ACE2/angiotensin-[1–7] interactions that normally regulate insulin resistance, insulin secretion, and pancreatic B cell survival [12].

These differences in expression point to a potential pathophysiological mechanism for pancreatic injury caused by SARS-CoV-2 [13]. Elevations in serum lipase or amylase may not always indicate pancreatic damage [14]. The pancreas produces the enzyme lipase, and the kidney is where it is eliminated. An increase in lipase’s serum level may result from reduced excretion, perhaps due to kidney illness. An elevated level of lipase in the serum may also be caused by diarrhea or intestinal irritation [14]. Lipase is an essential enzyme for the breakdown of triglycerides and is released mainly by the pancreas in adults [15]. Lipase and amylase levels are determined by the balance between their production from one side and their clearance from the other. Amylase is a digestive enzyme that facilitates the breakdown of starch. It is mainly secreted by the pancreas and salivary glands, but it can also come from other significant sources, including healthy and unhealthy lungs, the reticuloendothelial system and the kidneys are responsible for amylase clearance [16].

The standard definition of acute pancreatitis (clinically relevant pancreatic injury) requires the presence of at least two of three features, as per the revised Atlanta classification. These features include abdominal pain, increased serum amylase, lipase activity at least three times greater than the upper limit of normal, and characteristic findings of acute pancreatitis on contrast-enhanced computed tomography and, less frequently, magnetic resonance imaging or transabdominal ultrasonography [17].

Increased pancreatic enzyme levels in the blood are linked to numerous problems, such as diabetes, renal failure, and acidosis (9). Additionally, we discovered that in monkeys early in the course of the disease, the epithelial lining of the salivary gland ducts is affected by SARS-CoV [18]. C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute inflammatory protein that the liver synthesizes in response to infections [19, 20]. It is a highly sensitive biomarker for conditions such as infection, inflammation, and tissue damage, and the degree of inflammation is correlated with CRP levels [21]. Besides activating the complement system, CRP can also facilitate phagocytosis when it attaches itself to bacteria [22].

The objective of the current research is to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on pancreatic exocrine function by measuring the blood levels of lipase and amylase enzymes, aiming to identify potential alterations in enzyme activity and their association with disease severity and progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This case-control study was conducted at outpatient clinics from July 2021 to October 2021, following approval from the University of Baghdad College of Pharmacy’s ethical committee (REAFUBCP162621A) dated 01.06.2021, guidelines issued by Council of International Organization of Medical Science (CIOMS) in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO).

Sixty persons were enrolled in this study divided into two groups: Group I: 30 patients of both sexes diagnosed as COVID-19 with a positive result diagnosed via either nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab by Real-Time Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR). Patient’s age range (28-75 y), mean±SE (46.2±1.7). Group II: 30 participants were healthy persons of comparable age served as controls. A 10 ml venous Blood samples were collected from all participants and centrifuged to separate the serum for estimation of Immunoglobulin M (IgM), Immunoglobulin G (IgG) using the MAGLUMI 2019-nCoV IgM/IgG by a capture chemiluminescence immunoassay for IgM and an indirect chemiluminescence immunoassay for IgG (SNIBE company) [23,24]. Furthermore, C-Reactive protein ((CRP) MyBioSource company), amylase (MyBioSource company), and lipase (MyBioSource company) kits were measured using specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique [25]. Comorbid conditions such as metabolic disorders, endocrine disorders, renal disorders, cardiac disorders, respiratory disorders, pancreatitis and chronic liver disease were confirmed with medical history.

Exclusion criteria

children and young subjects (Age<18 y), patients with known case of chronic liver or pancreatic diseases, alcoholism, Moreover patient’s using drugs alter hepatic or pancreatic enzymes as, azathioprine, sulfonamide, valproic acid, Diuretics and estrogens, Pregnant and breastfeeding women.

The statistical estimation of data was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23. The normality of data distribution was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The P-value for measured data was less than 0.05, which means the data are not normally distributed. A nonparametric test was used for analysis, and a student t-test was used to compare the means of the groups. In addition, Spearman’s correlation test was used to analyze the correlations between parameters. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Serum immunoglobulins changes among COVID-19 patents compared to control groups

The result of the present study revealed a significant increase of the median serum immunoglobulins levels (IgM, IgG) (1.7 vs. 0.73AU/ml, 2.86 vs. 0.27 AU/ml) in the patient group compared to that of the control group respectively (P<0.05), as shown in table 1. These findings from IgM and IgG screening may offer significant benefits over nucleic acid detection as a quick, easy, and accurate way to identify possible COVID-19 cases. Additionally, probable cases with negative nucleic acid tests might be identified using IgM and IgG detection. IgG antibodies specific to SARS-CoV-2 are present for at least 8 mo following the onset of symptoms. Three factors have been found as potential predictors of IgG levels: the severity of COVID-19, the length of RNA shedding, and CRP levels. Additionally, 8 mo after infection, several individuals still exhibited detectable levels of IgM [26, 27].

The body’s organs, including the heart, kidneys, and lungs, in addition to the ability to support multiple organ systems, have all been negatively affected by COVID-19 [28]. It has also led to increased rates of morbidity and mortality as well as multiple systemic inflammatory reactions. Individuals who initially have gastrointestinal symptoms advance more quickly than those who do not. It is uncommon for COVID-19 individuals to experience acute pancreatitis induction, which can occur even after the viral infection has cleared. Previous (Almutairi F, et al. 2022) study investigation revealed that a prior COVID-19 infection was the cause of acute pancreatitis. COVID-19-induced acute pancreatitis is dangerous and can manifest quickly, necessitating hospitalization and constant observation to maintain hydration [29].

Serum pancreatic enzymes changes among COVID-19 patents compared to control groups

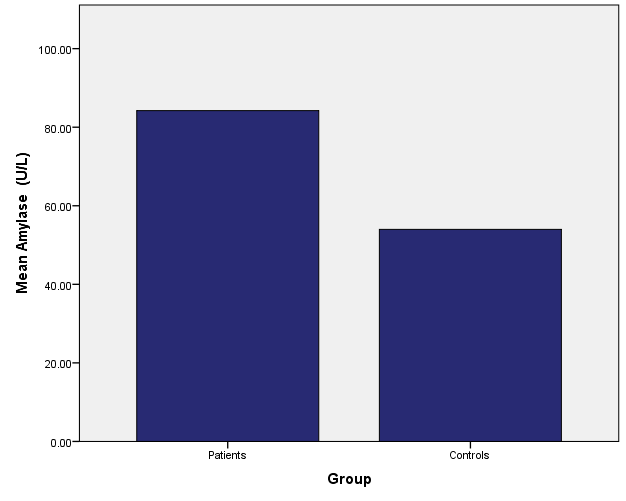

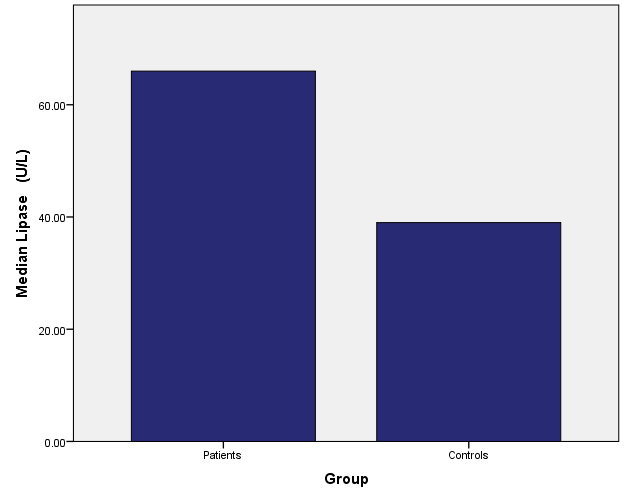

Current study results showed an increase in median patient’s serum pancreatic enzymes Amylase, and Lipase (86 vs. 54 U/l, and 66 vs. 39 U/l) compared to the control group respectively (P<0.05), however, none of the patients’ levels of these pancreatic enzymes reached three times the upper limit of normal as shown in table 1, fig. 1 and 2.

The possible explanation for these changes may be explained According to (Liu F et al. 2020) findings that ACE-2 is expressed in the normal human pancreas but slightly more so than in the lungs. Pancreatic injury can arise from SARS-CoV-2 binding to ACE-2 in the pancreas.

Additionally, evidence from single-cell RNA sequencing revealed that the pancreatic islets and exocrine glands both expressed ACE-2 [30]. According to the same study, 7.46% of patients with severe COVID-19 had pancreatic alterations; the most common changes were focal pancreatic enlargement or dilatation of the pancreatic duct in the absence of acute necrosis. Three of the 13 patients in the same research who had suffered pancreatic damage had higher entry levels of lipase and amylase. According to the study’s findings, pancreatic damage can happen to some COVID-19 patients, primarily to those who are very sick [30].

Previous study by (McNabb-Baltar et al. 2020) of the 71 patients with confirmed COVID-19 included nine individuals had hyperlipasemia, 2.8% of the participants, there were no clinical signs of acute pancreatitis, yet the lipase result was more than three times the upper limit of normal (>180 U/l). Out of these nine patients, six (66.7%) had anorexia, five (55.6%) diarrhea, five (55.6%) nausea, and three (33.3%) abdominal discomfort [31].

Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) changes among COVID-19 patents compared to control groups

Current study results revealed median serum CRP elevation reaching 7.5 mg/dl vs. 4 mg/dl to that of control (table 1). Since CRP is potential independent predictor of COVID-19 severity, Patients with a CRP level of more than 64.75 mg/l also had a higher risk of serious consequences. Furthermore, CRP serum levels can predict a patient’s illness development and the severity of COVID-19 [27].

Correlation study

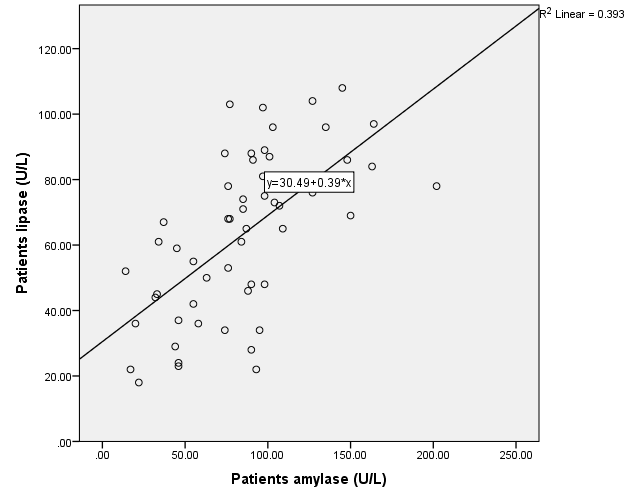

Moreover, correlation study results showed that even though the patients in this study had a significant increase in the median serum levels of lipase and amylase, none reached three times the upper limit of normal. The positive correlation between their serum levels (ρ = 0.627, p = 0.000) as shown in table 2, fig. 3. Suggesting that, instead of more involved and costly methods like imaging tests, measuring these enzymes is a quick and inexpensive way to rule out the development of acute pancreatitis complications.

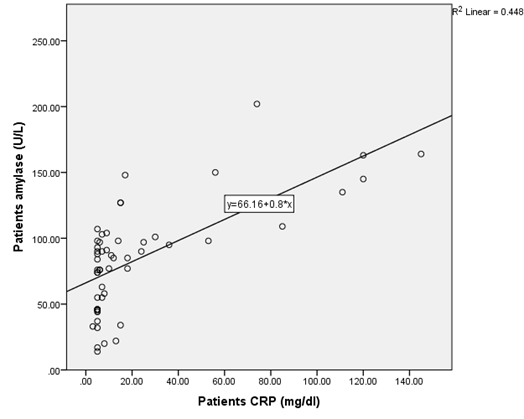

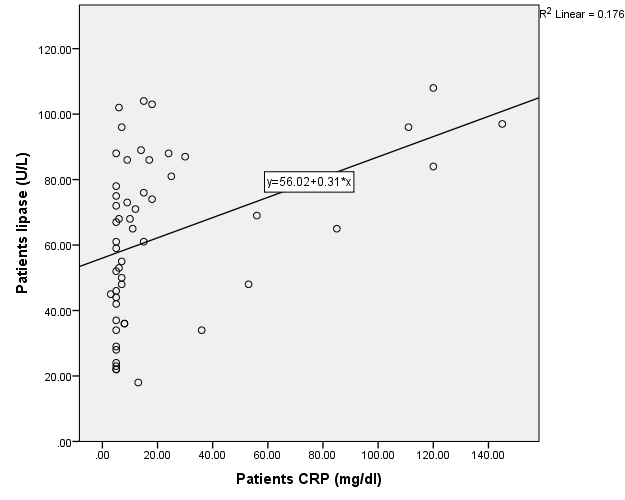

The presence of a positive correlation between serum levels of CRP with both amylase (ρ = 0.655, p = 0.000) and lipase (ρ = 0.53, p = 0.000) fig. 4 and 5, points to the need to estimate inflammatory markers such as CRP when monitoring the COVID-19 disease process and to study the relation of these parameters with clinical presentation of these patients.

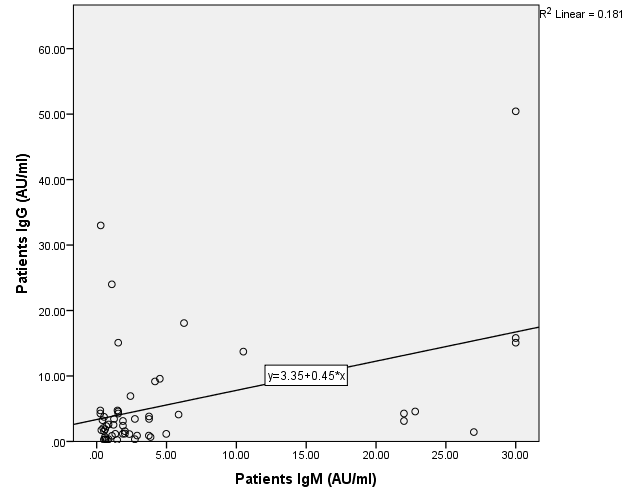

Although acute pancreatitis is not common in COVID-19 patients, pancreatic damage can occur in one-third of cases. Given that concurrent increase of lipase and amylase may be linked to a worse prognosis, this warrants additional investigation and suggests that patients should continue to be closely monitored, even after they have fully recovered, particularly in light of the positive correlation between IgM and IgG serum levels (ρ = 0.295, P = 0.031) table 2, fig. 6.

Table 1: Median, interquartile range, and P-values of studied parameters in patient and control groups

| Parameter | Group | Median | IQR | P-value |

| Age (y) | Patients | 43.5 | 25.25 | 0.401 |

| Controls | 43 | 23 | ||

IgM AU/ml |

Patients | 1.7 | 3.27 | 0.006* |

| Controls | 0.73 | 0.99 | ||

IgG AU/ml |

Patients | 2.86 | 3.47 | 0.002* |

| Controls | 0.27 | 0.45 | ||

| CRP (mg/dl) | Patients | 7.5 | 13 | 0.014* |

| Controls | 4 | 2 | ||

Amylase U/l |

Patients | 86 | 48.7 | 0.000* |

| Controls | 54 | 42 | ||

Lipase U/l |

Patients | 66 | 41 | 0.001* |

| Controls | 39 | 37 |

IgG: immunoglobulin G, IgM: immunoglobulin M, AU: absorbance unit, IQR: interquartile range, *(P<.0.05) significantly different compared to control

Fig. 1: Median of serum amylase levels for patient and control groups

Fig. 2: Median of serum lipase levels for patient and control groups

Fig. 3: Correlation of Amylase with Lipase in the patient’s group

Fig. 4: Correlation of CRP with Amylase in the patient’s group

Fig. 5: Correlation of CRP with lipase in the patient’s group

Table 2: Spearman correlation study between estimated parameters

| Parameter | Correlation | Age | Amylase | Lipase | IgG | IgM |

Amylase U/l |

ρ | 0.255 | - | 0.627** | 0.102 | 0.069 |

| P-value | 0.062 | - | 0.000 | 0.464 | 0.619 | |

Lipase U/l |

ρ | 0.133 | 0.627** | - | 0.087 | 0.166 |

| P-value | 0.337 | 0.000 | - | 0.533 | 0.229 | |

CRP Mg/dl |

ρ | 0.429** | 0.655** | 0.535** | 0.107 | 0.093 |

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.439 | 0.504 | |

IgM AU/ml |

ρ | –0.149 | 0.069 | 0.166 | 0.295* | - |

| P-value | 0.283 | 0.619 | 0.229 | 0.031 | - | |

IgG AU/ml |

ρ | –0.075 | 0.102 | 0.087 | - | 0.295* |

| P-value | 0.589 | 0.464 | 0.533 | - | 0.031 |

(P<0.05) is significantly different compared to the control * P<0.01) is highly significantly different compared to control*

Fig. 6: Correlation of IgM with IgG in the patient’s group

Because COVID-19-positive patients have a complex pathophysiologyand according to previous study by (Prasad H, et al. 2023) conclusion that should be careful if there is simultaneous elevation of amylase and lipase, as it may be associated with a worse prognosis [32], it is impossible to ascertain the pathophysiological mechanism underlying the elevated levels of lipase and amylase in COVID-positive patients, as it primarily appears to have a multifactorial pathogenesis. More comprehensive research on the extrapulmonary symptoms of COVID-19 is required to understand better the pathophysiological rationale for the rise of pancreatic enzymes in COVID-19-positive patients.

LIMITATIONS OF STUDY

This case study has numerous limitations. Due to the nature of the study, establishing a causal relationship between COVID-19 and the onset of acute pancreatitis is not possible. We did not conduct a systematic review. Therefore, future studies must be conducted to investigate the associated pathophysiological mechanism in more detail. Attention should also be paid to the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms and their timing concerning COVID-19 testing, as well as to more common laboratory and imaging findings.

CONCLUSION

The current study made clear how critical it is to estimate various characteristics of COVID-19 patients because the virus can target many organs, including the pancreas. Estimating pancreatic enzymes for infection assessment was shown to be easy and inexpensive compared to other instruments, such as imaging tests, which may not be accessible to all COVID-19 patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Dr. Salema Sultan Salman, Ph. D. Science of Physics, Remote Sensing, College of Pharmacy, University of Baghdad, Iraq, for her contribution to the graphic illustration, statistical and analytical study.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: Zahraa Mohammed Ali Naji, interpretation of laboratory measurements and ELISA Technique: Zahraa Mohammed Ali Naji and Shaimaa. M. Mohammed, drafting of the manuscript: Zahraa Mohammed Ali Naji, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Ihab I. Alkhalifa. and Shaimaa. M. Mohammed, clinical diagnosis and measurements of clinical PASI diagnostic tool by: Shaimaa. M. Mohammed and Lubna A. Alzubaidi.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

Pribadi RR, Simadibrata M. Increased serum amylase and/or lipase in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients: is it really pancreatic injury? JGH. 2021;5(2):190-2. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12436, PMID 33553654.

World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. (n. d.), 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features evaluation and treatment coronavirus (COVID-19). StatPearls, Treasure Island, FL; 2020. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk554776.

Yao XH, Li TY, He ZC, Ping YF. A pathological report of three COVID-19 cases by minimally invasive autopsies. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020 May 8;49(5):411–7. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200312-00193.

Zippi M, Hong W, Traversa G, Maccioni F, De Biase D, Gallo C. Involvement of the exocrine pancreas during COVID-19 infection and possible pathogenetic hypothesis: a concise review. Infez Med. 2020;28(4):507-15. PMID 33257624.

Yang JK, Lin SS, Ji XJ, Guo LM. Binding of SARS coronavirus to its receptor damages islets and causes acute diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2010;47(3):193-9. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0109-4, PMID 19333547.

Liu F, Long X, Zhang B, Zhang W, Chen X, Zhang Z. ACE2 expression in pancreas may cause pancreatic damage after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):2128-30.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.040, PMID 32334082.

Szlachcic WJ, Dabrowska A, Milewska A, Ziojla N, Blaszczyk K, Barreto Duran E. SARS-CoV-2 infects an in vitro model of the human developing pancreas through endocytosis. iScience. 2022;25(7):104594. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104594, PMID 35756892.

Wu CT, Lidsky PV, Xiao Y, Lee IT, Cheng R, Nakayama T. SARS-CoV-2 infects human pancreatic β cells and elicits β cell impairment. Cell Metab. 2021;33(8):1565-76.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.05.013, PMID 34081912.

Correia De Sa T, Soares C, Rocha M. Acute pancreatitis and COVID-19: a literature review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;13(6):574-84. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i6.574, PMID 34194615.

Muller JA, Groß R, Conzelmann C, Kruger J, Merle U, Steinhart J. SARS-CoV-2 infects and replicates in cells of the human endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Nat Metab. 2021;3(2):149-65. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00347-1, PMID 33536639.

Memon B, Abdelalim EM. ACE2 function in the pancreatic islet: implications for relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and diabetes. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2021;233(4):e13733. doi: 10.1111/apha.13733, PMID 34561952.

Hikmet F, Mear L, Edvinsson A, Micke P, Uhlen M, Lindskog C. The protein expression profile of ACE2 in human tissues. Mol Syst Biol. 2020;16(7):e9610. doi: 10.15252/msb.20209610, PMID 32715618.

De Madaria E, Siau K, Cardenas Jaen K. Increased amylase and lipase in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: don’t blame the pancreas just yet! Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1871. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.044, PMID 32330475.

Pieper Bigelow C, Strocchi A, Levitt MD. Where does serum amylase come from and where does it go? Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1990;19(4):793-810. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8553(21)00514-8, PMID 1702756.

Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG. Classification of acute pancreatitis 2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-11. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779.

Hameed AM, Lam VW, Pleass HC. Significant elevations of serum lipase not caused by pancreatitis: a systematic review. HPB (Oxf). 2015;17(2):99-112. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12277.

Liu L, Wei Q, Alvarez X, Wang H, Du Y, Zhu H. Epithelial cells lining salivary gland ducts are early target cells of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the upper respiratory tracts of rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2011;85(8):4025-30. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02292-10, PMID 21289121.

Khalil RH, Al Humadi N. Types of acute phase reactants and their importance in vaccination. Biomed Rep. 2020;12(4):143-52. doi: 10.3892/br.2020.1276, PMID 32190302.

Kamal EM, Abd El Hakeem MA, El Sayed AM, Ahmed MM. Validity of c-reactive protein and procalcitonin in the prediction of bacterial infection in patients with liver cirrhosis. Minia Journal of Medical Research. 2019;30(3):124-7. doi: 10.21608/mjmr.2022.221909.

Sproston NR, Ashworth JJ. Role of C-reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:754. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00754, PMID 29706967.

Gershov D, Kim S, Brot N, Elkon KB. C-reactive protein binds to apoptotic cells protects the cells from assembly of the terminal complement components and sustains an antiinflammatory innate immune response: implications for systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2000;192(9):1353-64. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1353, PMID 11067883.

Campbell AK, Patel A. A homogeneous immunoassay for cyclic nucleotides based on chemiluminescence energy transfer. Biochem J. 1983;216(1):185-94. doi: 10.1042/bj2160185, PMID 6316935.

Shah K, Maghsoudlou P. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA): the basics. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2016;77(7):C98-101. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2016.77.7.C98, PMID 27388394.

Jia X, Zhang P, Tian Y, Wang J, Zeng H, Wang J. Clinical significance of an IgM and IgG test for diagnosis of highly suspected COVID-19. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:569266. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.569266, PMID 33912572.

Guo J, Li L, Wu Q, Li H, Li Y, Hou X. Detection and predictors of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels in COVID-19 patients at 8 m after symptom onset. Future Virol. 2021;16:795-804. doi: 10.2217/fvl-2021-0141, PMID 34804188.

Sadeghi Haddad Zavareh M, Bayani M, Shokri M, Ebrahimpour S, Babazadeh A, Mehraeen R. C-reactive protein as a prognostic indicator in COVID-19 patients. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2021;2021:5557582. doi: 10.1155/2021/5557582, PMID 33968148.

Mokhtari T, Hassani F, Ghaffari N, Ebrahimi B, Yarahmadi A, Hassanzadeh G. COVID-19 and multiorgan failure: a narrative review on potential mechanisms. J Mol Histol. 2020;51(6):613-28. doi: 10.1007/s10735-020-09915-3, PMID 33011887.

Almutairi F, Rabeie N, Awais A, Samannodi M, Aljehani N, Tayeb S. COVID-19 induced acute pancreatitis after resolution of the infection. J Infect Public Health. 2022;15(3):282-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.01.003, PMID 35077949.

Liu F, Long X, Zhang B, Zhang W, Chen X, Zhang Z. ACE2 expression in pancreas may cause pancreatic damage after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):2128-30.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.040, PMID 32334082.

Mc Nabb Baltar J, Jin DX, Grover AS, Redd WD, Zhou JC, Hathorn KE. Lipase elevation in patients with COVID-19. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(8):1286-8. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000732, PMID 32496339.

Prasad H, Ghetla SR, Butala U, Kesarkar A, Parab S. COVID-19 and serum amylase and lipase levels. Indian J Surg. 2023;85(2):337-40. doi: 10.1007/s12262-022-03434-z, PMID 35578610.