Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 227-237Original Article

FORMULATION AND EVALUATION OF DRY POWDER INHALABLE NANOPARTICLES FOR THE TREATMENT OF COVID-19

SAGAR VS1*, JANAKIRAMAN K.1, AKHIL2, JOYSA RUBY J.2

1Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar, Chidambaram-608002, Tamil Nadu, India. 2Acharya BM Reddy College of Pharmacy, Soldevanahalli, Hesaraghatta Road, Bengaluru, Karnataka-560107, India

*Corresponding author: Sagar VS; *Email: vemalasagar@gmail.com

Received: 03 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 14 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This work sought to develop and assess remdesivir (REM) nanoparticles to achieve increased pulmonary administration, prolonged drug release, and enhanced bioavailability through a polymer-based nanoparticulate system.

Methods: REM nanoparticles were synthesised utilising Poloxamer 407 and HPMC E3 by a solvent evaporation method. The formulation was analysed for drug content, particle size (PS), surface morphology, and thermal properties. In vitro drug release tests were performed to assess the release profile for 48 h. Kinetic modelling was conducted to ascertain the release mechanism, and stability experiments were executed to evaluate long-term formulation stability.

Results: The nanoparticulate system has a PS of 228.3±37.64 to 492.22±174.6 nm and zeta potential (ZP) of-17±5.31 to-27.3±6.76 mV. The F4 nanoparticles exhibited precise drug content and homogenous PS, with Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) examination indicating a well-defined surface shape suitable for pulmonary delivery. In vitro release experiments demonstrated a sustained release profile, with 78.96% cumulative release over 48 h. The release mechanism was determined to be non-Fickian diffusion or erosion-controlled. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) analysis verified the total encapsulation of the medication within the polymer matrix. Stability experiments revealed no substantial alterations in PS, polydispersity index (PDI), ZP throughout the storage period.

Conclusion: The optimised REM nanoparticle formulation (F4) demonstrated favourable attributes for regulated pulmonary drug administration, featuring prolonged release and stable physicochemical features. These findings indicate significant industrial and therapeutic potential; nevertheless, additional clinical assessment is required to verify in vivo efficacy and safety.

Keywords: Remdesivir, Poloxamer 407, HPMC E3, Solvent evaporation method, Prolonged drug release, Bioavailability

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54859 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

In 2019, 2019-nCoV, now SARS-CoV-2, was discovered in Wuhan, Hubei province, China [1]. Coronaviruses have a lipid covering and a positive-sense RNA viral genome coated in spike-like projections that resemble crowns under the microscope. Their diameter ranges from 60 nm to 140 nm. Large droplets from coughing and sneezing by sick patients spread the virus [2]. The nasal cavity has larger virus loads than the throat, whereas symptomatic and asymptomatic patients have similar viral burdens [3]. In ideal conditions, ejected droplets can spread 1-2m, settle on surfaces, and survive for several days. Hydrogen peroxide and sodium hypochlorite deactivate it quickly [4]. Transmission occurs by inhaling droplets or touching infected surfaces and then touching the nose, mouth, or eyes [5]. SARS-CoV-2 employs its spike (S) glycoprotein on its surface. This protein has two subunits, S1, that attach to host cells and contain a Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) that binds to Angiotensin Converting Enzyme(ACE) 2 in the respiratory system, heart, lungs, intestines, kidneys, and bladder. After attaching S2 to the cell membrane, the host enzyme Transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) activates the virus, which penetrates and replicates. As infection develops, Interleukin(IL)-6, Tumor Necrosis Factor(TNF)-α, and cytokines cause extensive inflammation and organ damage [6]. Different processes cause pulmonary edema and vascular permeability in individuals with severe COVID-19. Virus-caused endothelial cell damage and perivascular inflammation cause microvascular injury and microthrombosis. The virus also affects the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) by binding to ACE2 inhibitors. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 activates toll-like receptors (TLRs), leading to pro-IL-1β production and lung inflammation [7-9].

SARS-CoV-2 mostly damages the respiratory system but also the GI tract, heart, lungs, kidneys, and brain. Viral toxicity, RAS pathway disruption, immunological dysfunction, and thrombosis harm organs. COVID-19 can cause myocarditis, vascular irritation, and arrhythmias. Leukopenia in COVID-19 may be caused by ACE-2-mediated lymphocyte death, direct viral invasion of lymph organs, or cytokine-induced apoptosis. Pre-existing coronary artery disease, systemic inflammation, decreased coronary blood flow, and microthrombosis can cause acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Platelet inhibition by viruses can cause thrombocytopenia [10, 11]. COVID-19 is treated worldwide with antiviral medications including remdesivir (REM), lopinavir, antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, and immunomodulatory therapies like tocilizumab, lenzilumab, and ravulizumab [12]. Wide-spectrum adenosine nucleotide analogue antiviral prodrug REM targets RNA viruses such as filoviruses, coronaviruses, and paramyxoviruses. By inhibiting RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase, the cyano group's steric blockage in the third ribose moiety delays chain termination, preventing viral propagation [13-15]. Nanoparticles increase bioavailability, specificity, and selectivity and extend pharmacological effects, improving therapeutic efficacy. Thus, nanocarriers may improve REM remediation by enhancing water solubility and stability, minimizing side effects [16, 17]. Nanosuspensions (NS) transport active components or medications to specific tissues, cells, or organs. The surface modification of nano-suspension permits site-specific drug release with minimal systemic side effects and improved therapeutic efficiency [18]. This study highlights antiviral NS and improves REM medication delivery solubility for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

REM was provided as complimentary samples from Hetero Drugs, Hyderabad, India. Poloxamer 407 and HPMC E3 were supplied by TCI Chemicals, India. All solvents were of analytical grade.

Methods

Pre-formulation studies

Preformulation studies serve as the initial phase of drug development, examining the chemical, physical, and mechanical properties of a new drug. The primary objective is to assess the drug's physicochemical attributes to enhance the drug delivery system, ensure excipient compatibility, and evaluate key factors such as solubility and melting point [19].

Solubility studies

Solubility studies were conducted using different solvents, including methanol, ethanol, water, chloroform, Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), acetonitrile, and acetone. The drug's solubility was visually evaluated and categorized as soluble, slightly soluble, or freely soluble [20].

Melting point determination

The melting point of REM was measured using Thiele’s tube apparatus. The drug was placed in acapillary tube, and the temperature at which it began to melt was observed and documented [21].

Compatibility studies using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

FT-IR was utilized to evaluate the compatibility between the pure drug and polymers. The samples were analyzed within a spectral range of 4000 cm⁻¹ to 400 cm⁻¹ and compared with reference FT-IR spectra [22].

Determination of λmax of REM

REM's maximum absorption wavelength (λmax) was determined using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer. A solution of REM was prepared and scanned within the 200–800 nm range, with the highest absorption observed at 247 nm.

Standard calibration curve of REM

A standard calibration curve for REM was established using serial dilutions. Different concentrations (10–50 µg/ml) were prepared and analyzed with a UV-Visible spectrophotometer at 247 nm [23].

Formulation, design, and optimization

During the nanoparticle formulation, different polymer concentrations were evaluated to optimize drug encapsulation.

Development of REM-loaded NS

REM-loaded NS were synthesized utilizing a solvent–antisolvent precipitation technique under probe sonication. In summary, 100 mg of REM and variable quantities of Poloxamer 407 (generally 15 mg) were solubilized in 10 ml of methanol to create the organic phase. Independently, 0.2–1% w/v HPMC-E3 (for instance, 500 mg in 50 ml) was suspended in filtered water to create the aqueous phase as reported in table 1. The organic solution was incrementally introduced into the aqueous phase by a syringe or pipette during continuous sonication with a 6 mm probe (Ultrasonic Processor VCX 750, Sonics and Materials Inc., USA). Sonication was conducted for 30 min at an amplitude of 40 µm (50% power), with a pulse cycle of 10 seconds on and 1 second off, resulting in an energy input of 120 J/ml. A 5% w/v trehalose solution was included as a cryoprotectant. The resultant NS were frozen at −80 °C for 12 h and subsequently lyophilized at −55 °C under vacuum (<0.01 mbar) for 48 h to yield dry nanopowder for subsequent analysis [24].

Table 1: Composition of REM loaded NS (F1-F8)

| Formulation | REM (mg) | Poloxamer 407 (mg) | HPMC E3 (% w/v in 50 ml) | Methanol (ml) | Water (ml) |

| F1 | 100 | 15 | 0.2% | 10 | 50 |

| F2 | 100 | 15 | 0.5% | 10 | 50 |

| F3 | 100 | 10 | 0.5% | 10 | 50 |

| F4 | 100 | 20 | 0.5% | 10 | 50 |

| F5 | 100 | 10 | 0.8% | 10 | 50 |

| F6 | 100 | 15 | 1.0% | 10 | 50 |

| F7 | 100 | 20 | 0.2% | 10 | 50 |

| F8 | 100 | 5 | 0.5% | 10 | 50 |

REM-Remdesivir, NS-Nano suspension

NS characterization studies

Mean particle size (PS), zeta potential (ZP), and polydispersity index (PDI)

PS, PDI, and ZP of the NS were assessed via dynamic light scattering (DLS) utilising a Malvern Nano S90 instrument. Before measurement, samples were diluted tenfold with deionised water. All analyses were conducted at 25 °C and a scattering angle of 90°. ZP was assessed via a disposable cell employing the electrophoretic mobility approach. Measurements were performed in triplicate, and results were presented as averages [25].

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of the nanoparticles was examined using SEM. The samples were coated with gold and analysed at different magnifications under a 15 kV voltage [26].

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The Perkin Elmer DSC instrument was utilised to examine the thermal characteristics of REM and REM nanoparticles. The samples were incrementally heated from 30 °C to 300 °C, and the heat absorption was observed.

In vitro evaluation

Drug content estimation

After dissolving the REM nanoparticles in ethanol, they were centrifuged to separate the different components. After that, the supernatant was diluted, and UV-visible spectroscopy was used to analyze and quantify the amount of medication present.

Drug release studies

An evaluation of the nanoparticle medication release was carried out at 37 °C utilising the dialysis bag method. Samples were collected at predetermined intervals to analyze drug diffusion, and UV spectroscopy was utilized [20].

Stability studies

Stability assessments of the lyophilised REM nanoparticles were performed in compliance with ICH recommendations. The samples were maintained at 40 °C and 75% relative humidity for three months, during which PS, PDI, and ZP were evaluated [27].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Pre-formulation studies

Pre-formulation experiments were conducted to assess the physical features of the medication. The research encompassed the determination of lambda max, solubility analysis, preparing a standard plot, and assessing compatibility.

Preliminary solubility analysis of REM

Pre-formulation tests evaluated solubility and compatibility, indicating that REM showed inadequate water solubility but exhibited enhanced solubility in alcohols and other solvents, aligning with its designation as a BCS Class IV medication. The solubility of REM in various solvents is presented in table 1.

Table 1: Solubility profile of REM

| S. No. | Solvent | Solubility |

| 1 | Water | Practically insoluble |

| 2 | DMSO | Readily soluble |

| 3 | Chloroform | Sparingly soluble |

| 4 | Methanol | Readily soluble |

| 5 | Acetone | Readily soluble |

| 6 | Ethanol | Readily soluble |

REM: Remdesivir

FTIR studies

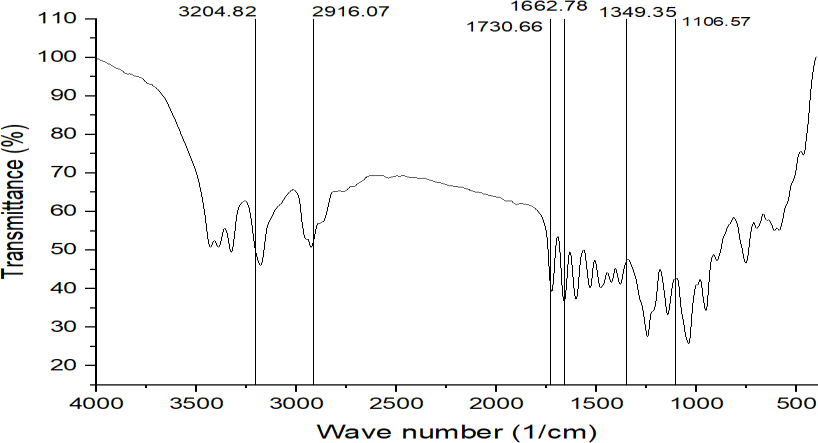

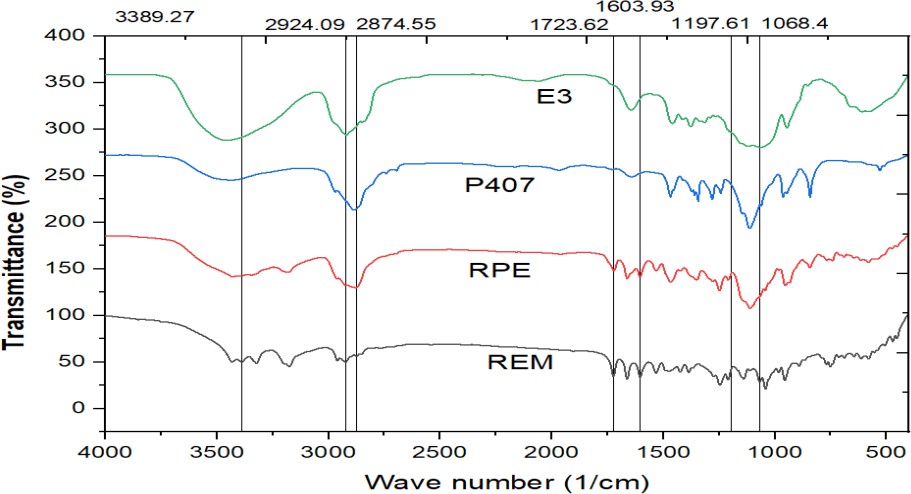

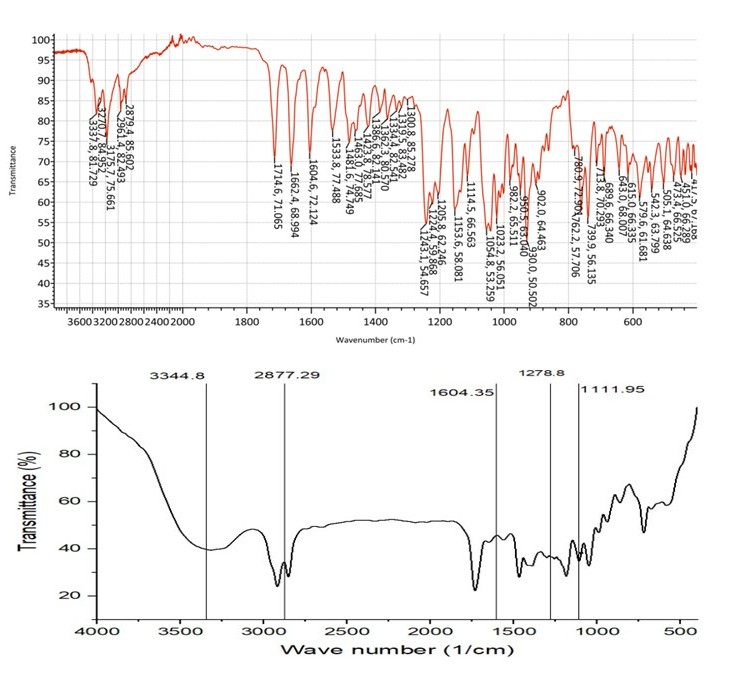

FT-IR spectroscopy was utilised to assess the compatibility of the medications and polymers in the nanoparticle compositions. The FT-IR spectra of pure REM are presented in fig. 1, whereas the spectra of REM, Poloxamer-407, HPMC E-3, and their physical mixing were examined using a Hitachi 3400S (Japan) and depicted in fig. 2.

Fig. 1: FT-IR spectrum of REM, REM: Remdesivir

Fig. 2: FT-IR spectrum of REM+RPE+P407+E3, REM: Remdesivir, RPE: Drug loaded formulation, P407-poloxamer 407, E3-HPMC E3

The FT-IR spectra of REM (pure drug), RPE (drug-loaded formulation), P407 (polymer), and E3(HPMC E3) provide valuable information about the chemical structure and potential interactions within the formulation. REM has distinct peaks at 3389.27 cm⁻¹ (O-H/N-H stretching), 2924.09 and 2874.55 cm⁻¹ (C-H stretching), 1723.62 cm⁻¹ (C=O stretching), and 1197.61 and 1068.4 cm⁻¹ (C-O-C/C-N stretching), indicating functional groups. These peaks are still present in the RPE spectrum, but with lower intensity and small shifts, indicating that REM may be hydrogen-bonding or dispersed molecularly within the formulation matrix. The P407 spectrum shows peaks associated with polyether structures, such as O-H stretching and C-O-C vibrations, but no indication of new chemical bond formation. In the E3 spectrum, identical peaks are retained with modest changes, particularly in the hydroxyl and carbonyl areas, showing non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding between REM, P407, and excipients. The absence of new peaks across all spectra suggests that REM retains its chemical integrity, and there were no significant chemical interactions or degradation throughout formulation, showing high component compatibility.

Melting point analysis

The melting point determination was performed using Thiele's tube technique. The measured melting point varied between 127 and 129 °C, affirming the pure compound's identity as REM.

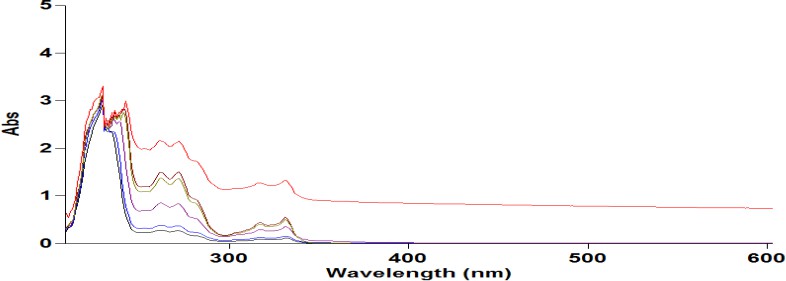

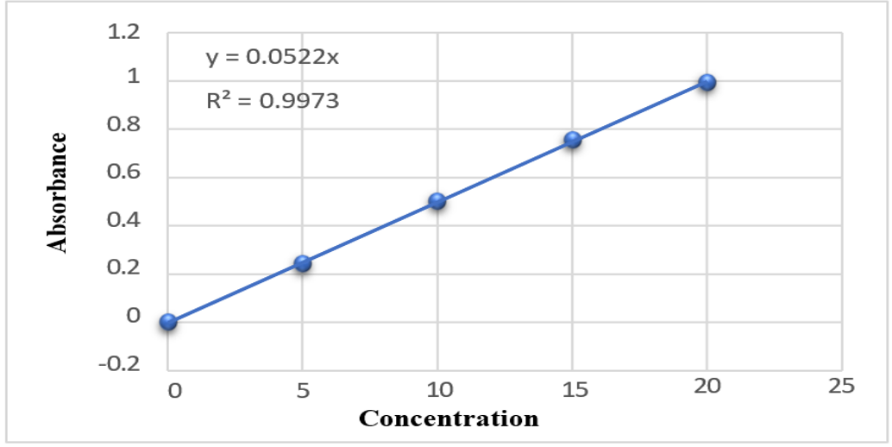

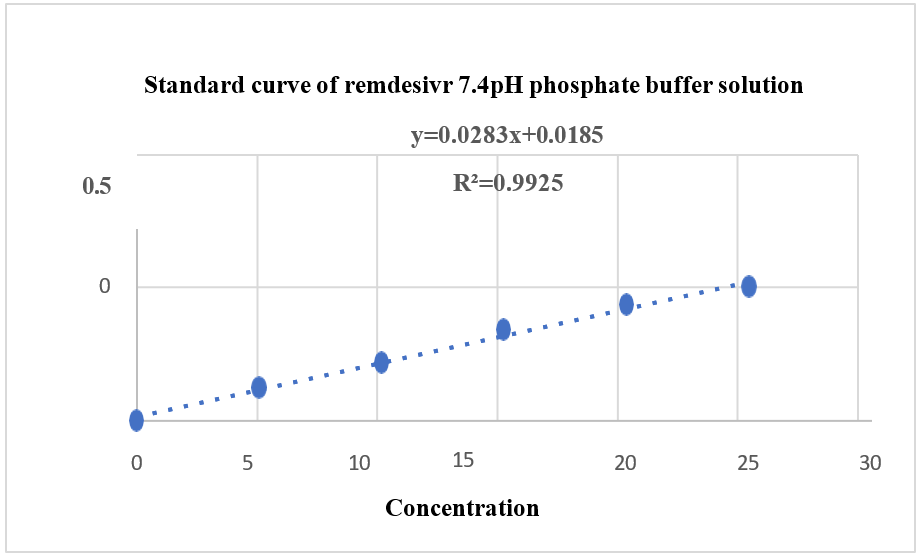

Determination of λmax by UV-visible spectroscopy standard plot of REM

A REM solution was produced in distilled water and analysed for absorbance in the 200–800 nm range with a UV spectrophotometer (Agilent Technology, Cary 60). The highest absorbance was recorded at 247 nm, aligning with the documented USP peak illustrated in fig. 3. A standard plot for REM was produced utilising a UV-visible spectrophotometer at 247 nm, employing water as the blank, as illustrated in fig. 4 and 5. Absorbance measurements were conducted for values between 0 and 20 µg/ml. The regression coefficient (R²) was determined to be 0.9973.

Fig. 3: Graph showing λmax of REM at 247 nm, REM: Remdesivir

Fig. 4: Standard calibration of REM by UV-Visible spectroscopy, REM: Remdesivir

Fig. 5: Standard calibration plot of REM 7.4 pH phosphate buffer solution by UV-Visible spectroscopy, REM: Remdesivir

Formulation design and optimization of REM NanoParticles

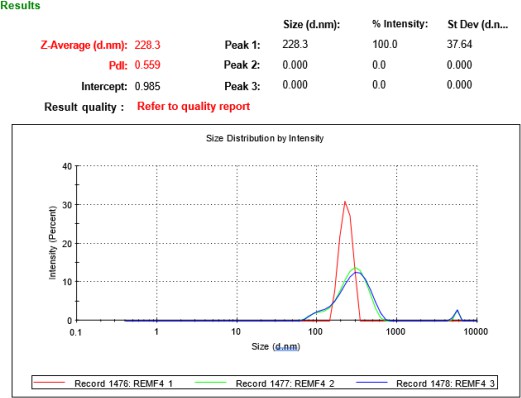

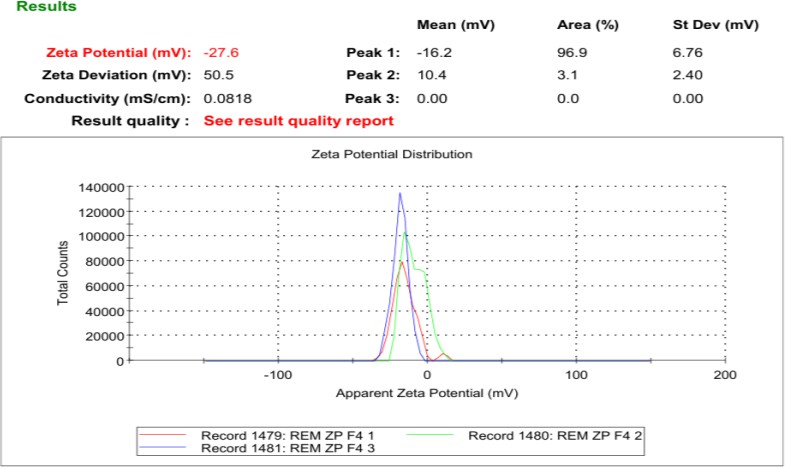

Table 2 summarizes the PS, PDI, ZP, and drug content for eight REM-loaded NS formulations, indicating significant variability in physicochemical properties attributed to variations in formulation composition and processing conditions. The average particle sizes varied from 228.3±37.64 nm to 492.2±174.6 nm, with PDI values ranging from 0.341 to 0.559, suggesting a moderate size distribution. The values were obtained through DLS under standardized conditions in water (viscosity: 0.8872 mPa·s; refractive index: 1.330), with the refractive index of REM estimated at 1.580. Formulations F2, F4, and F7 exhibited smaller particle sizes, which is beneficial for improving drug solubility and bioavailability through increased surface area. F4 exhibited the lowest PS and the highest drug content, suggesting effective drug loading and uniform particle dispersion. F4 demonstrated the most significant negative ZP, which promotes colloidal stability via electrostatic repulsion, thereby decreasing the probability of aggregation. In contrast, F5, F6, and F8 demonstrated larger PS values (>400 nm), with F6 presenting the highest size and the lowest drug content, indicating poor drug entrapment efficiency or aggregation during processing. F8 exhibited a significant particle size with the lowest ZP, suggesting inadequate stability and drug loading efficiency. PDI values indicate potential particle heterogeneity or aggregation; however, SEM verified the existence of distinct, spherical particles with limited clustering. The observed discrepancy is attributable of loosely associated aggregates during SEM sample preparation, highlighting the impact of analytical techniques on particle characterization. The ZP values for the formulations varied from −17.0±5.31 mV to −27.3±6.76 mV, indicating moderate colloidal stability. While ZP exceeding 30 mV is typically favored for suspension stability, this standard is less significant for dry powder inhalers (DPIs), where the emphasis is on redispersibility within the pulmonary environment. Inhaled particles interact with the lung's surfactant layer, potentially modifying surface charge and contributing to stabilization. The inclusion of Poloxamer 407 and HPMC E3 facilitates steric stabilization, thereby reducing aggregation during deposition in the respiratory tract. F4 was chosen as the best formulation due to its superior physicochemical profile. It had the lowest PDI and the smallest PS, which is good for deep lung deposition. The batch with the highest drug content and the lowest ZP was F4, indicating effective drug loading. F7 had comparable drug content and a tiny PS, but its greater PDI and lower ZP indicated reduced physical homogeneity and moderate stability. F4 was the best lyophilization and pulmonary delivery trial option [28, 29].

Table 2: Results of mean PS, ZP, and drug content of REM of F1 to F8

| S. No. | PS(nm) | PDI | ZP(mV) | Drug content in 1 mg/ml |

| F1 | 373.5±101.7 | 0.487±0.02 | -17.0±5.31 | 0.722 |

| F2 | 268.3± 69.68 | 0.459±0.03 | -20.3±5.65 | 0.867 |

| F3 | 293.1±119.4 | 0.429±0.04 | -17.8±4.32 | 0.785 |

| F4 | 228.3±37.64 | 0.341±0.04 | -27.3±6.76 | 1.011 |

| F5 | 432.2±152.6 | 0.558±0.05 | -19.4±5.67 | 0.756 |

| F6 | 492.22±174.6 | 0.559±0.03 | -21.8±4.92 | 0.643 |

| F7 | 277.4±70.86 | 0.453±0.02 | -20.6±6.89 | 0.967 |

| F8 | 404±132.6 | 0.519±0.04 | -19.1±4.67 | 0.543 |

Data was calculated triplicates and represented as mean±SEM, PS: Particle size, PDI: Polydispersity index, ZP: Zeta potential

Fig. 6: Mean PS and PDI of a non-optimized formula of F4 and an optimized formula of F4, PS: Particle size, PDI: Polydispersity index

Fig. 7: Mean Zeta size of an optimized formulation of F4, REM: Remdesivir

FT-IR spectrum of DPI formulation

The FT-IR analysis of plain REM and the F4 formulation (fig. 8) indicates that the distinctive peaks of REM—specifically the O–H/N–H stretching at 3204.82 cm⁻¹, C–H stretching at 2916.07 cm⁻¹, and the prominent carbonyl (C=O) stretch at 1730.66 cm⁻¹—are preserved in the F4 formulation, albeit with minor shifts and variations in intensity. In the F4 spectra, the O–H/N–H peak is observed at 3344.8 cm⁻¹ and exhibits a broader profile, suggesting possible hydrogen bonding interactions with excipients. Correspondingly, the C–H stretch transitions to 2877.29 cm⁻¹, while the aromatic/N/N-H bending band shifts from 1662.78 cm⁻¹ in the unmodified drug to 1604.35 cm⁻¹ in F4, indicating modifications in the molecular environment resulting from the formulation. The persistence of C–O–C and C–N stretching bands at approximately 1278.8 and 1111.95 cm¹ further substantiates the structural integrity of REM in the formulation. No new peaks or loss of essential functional groups were found, showing that the formulation procedure did not chemically modify the medication. The spectral alterations indicate physical interactions, primarily hydrogen bonding, between REM and formulation excipients, affirming that F4 provides a stable and suitable NS without jeopardising the drug's chemical identity.

Fig. 8: FT-IR spectra of REM and optimized formulation F4, REM: Remdesivir

SEM

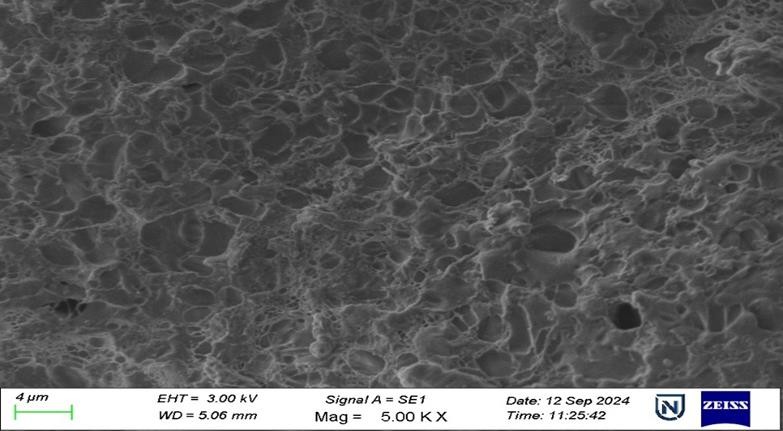

The SEM picture of the F4 formulation (fig. 9), taken at 10,000× magnification, displays a porous and interconnected surface morphology characterised by a sponge-like network. This structure signifies the successful creation of a NS matrix in which drug nanoparticles are likely incorporated within or adsorbed onto the carrier network. The existence of uniformly distributed pores and surface roughness indicates a substantial surface area, which can markedly improve the dissolving rate and bioavailability of weakly water-soluble pharmaceuticals such as REM. The lack of substantial crystalline formations suggests that the medication may exist in an amorphous or molecularly dispersed state, enhancing solubility. The image exhibits no indications of aggregation, suggesting excellent dispersion stability, probably due to optimised formulation conditions and the appropriate application of stabilisers. The SEM study substantiates that the F4 formulation exhibits an advantageous nanostructured architecture, enhancing its drug loading and release properties.

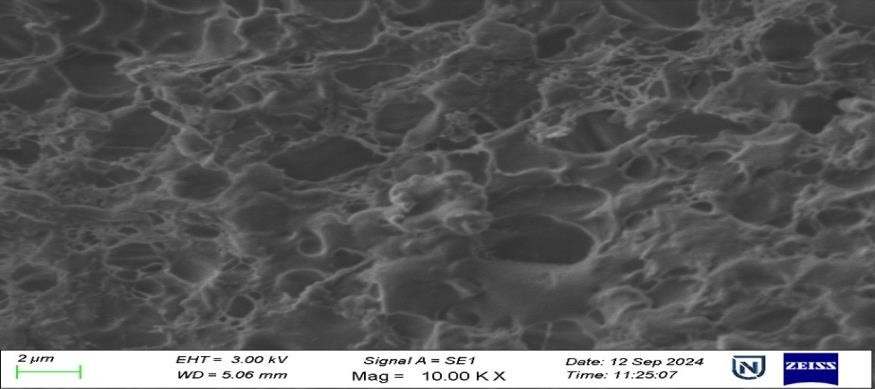

Thermal analysis was performed utilizing DSC to assess REM's physical state and thermal behavior within the nanoparticle matrix. The DSC thermogram of pure REM exhibited a distinct endothermic peak at around 127.6 °C, confirming its crystalline characteristics. In contrast, the REM-loaded nanoparticle formulations, especially F4, did not display a distinct melting peak. The thermogram of F4 (fig. 10) exhibited a broad endothermic transition in the range of 90–120 °C, which is likely associated with the loss of moisture or volatiles attributed to hydrophilic excipients, including HPMC and Poloxamer 407. The lack of REM's distinct melting point and the modified thermal profile suggest that the drug has shifted into an amorphous or molecularly dispersed state within the polymeric matrix, resulting from rapid precipitation and solid-state dispersion during solvent evaporation and lyophilization. This transformation improves the dissolution characteristics of the drug. The TGA analysis indicated that the REM-loaded nanoparticles demonstrate enhanced thermal stability relative to the pure drug, with negligible weight loss of around 300 °C and substantial decomposition occurring only beyond 300–350 °C. The derivative thermogravimetric curve validated the initiation of thermal degradation at elevated temperatures, thereby supporting the stability of the formulation. The thermal data validate REM's effective encapsulation and amorphization, indicating enhanced stability and the lack of drug-excipient incompatibility, thereby supporting the NS system's suitability for improved solubility, stability, and bioavailability.

Fig. 9: SEM images of REM nanoparticles at a magnification of 5.00 KX and 10.00 KX DSC, SEM: Scanning electron microscopy, REM: Remdesivir, DSC: Differential scanning calorimetry

Fig. 10: Differential scanning calorimetry curve of REM and formulation F4, REM: Remdesivir

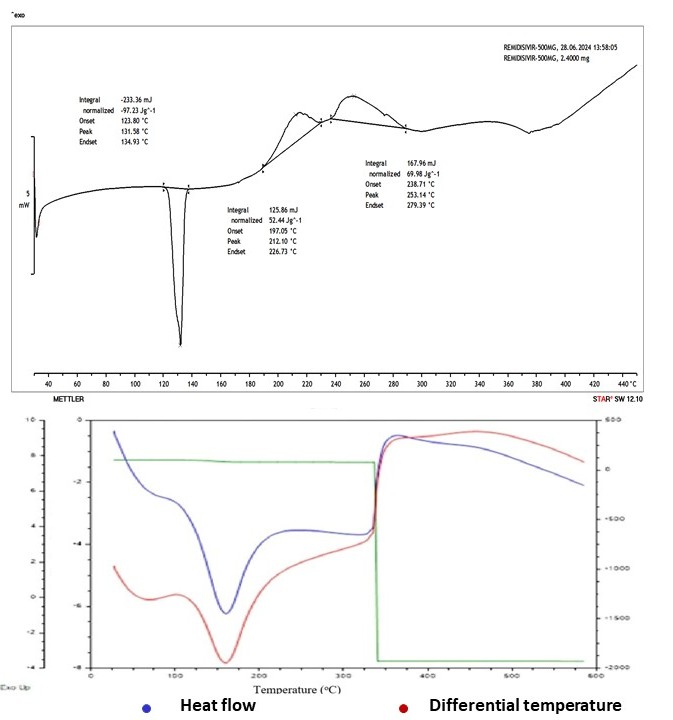

X-ray diffraction studies (XRD)

The XRD analysis confirmed the conversion of REM from its original crystalline structure to an amorphous state in the nanoparticle formulations. The XRD pattern of pure REM exhibited distinct and sharp peaks at 2θ values of 6.7°, 9.4°, and 19.1°, indicative of its crystalline structure. The REM-loaded nanoparticle formulations, especially F4 (fig. 11), displayed a broad halo with no distinct peaks, suggesting a primarily amorphous structure. The lack of crystallinity indicates that REM experienced a physical transformation during formulation, likely resulting from the rapid precipitation and solid-state dispersion caused by the solvent–antisolvent process, lyophilization, and potential interactions with the excipients. A quantitative crystallinity index was calculated through integrated peak area analysis, indicating that the relative crystallinity of the nanoparticles was less than 10% compared to pure REM. This means it indicates considerable amorphization, which benefits poorly water-soluble drugs such as REM, as the amorphous state generally provides improved solubility and accelerated dissolution rates. The absence of distinct crystalline peaks corresponds with the DSC results, which showed no characteristic melting endotherm for REM. This reinforces the conclusion that the drug is molecularly dispersed or stabilized within an amorphous solid dispersion. The XRD results indicate successful amorphization of REM in the F4 formulation, enhancing solubility, bioavailability, and formulation stability.

Fig. 11: Powder X-ray diffraction pattern for REM and formulation F4, REM: Remdesivir

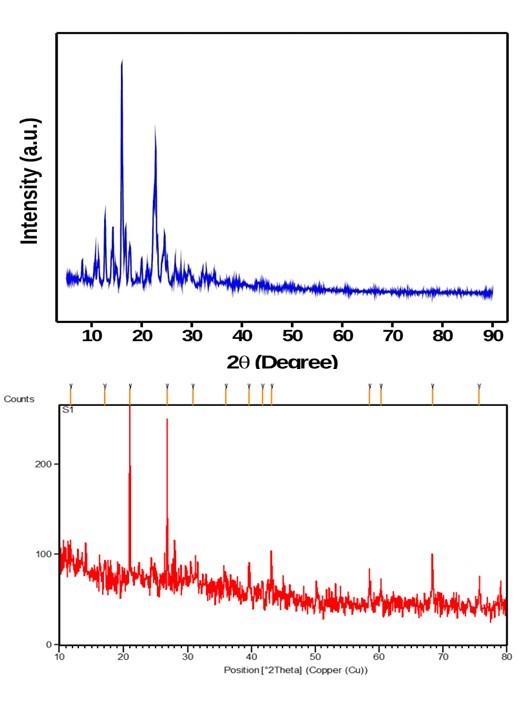

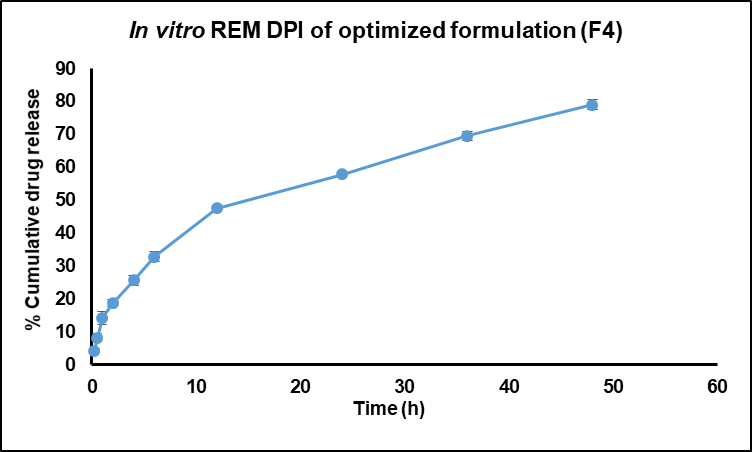

Fig. 12: In vitro REM DPI of optimized formulation (F4), REM: Remdesivir, DPI: Dry Powder inhalation

In vitro drug release studies

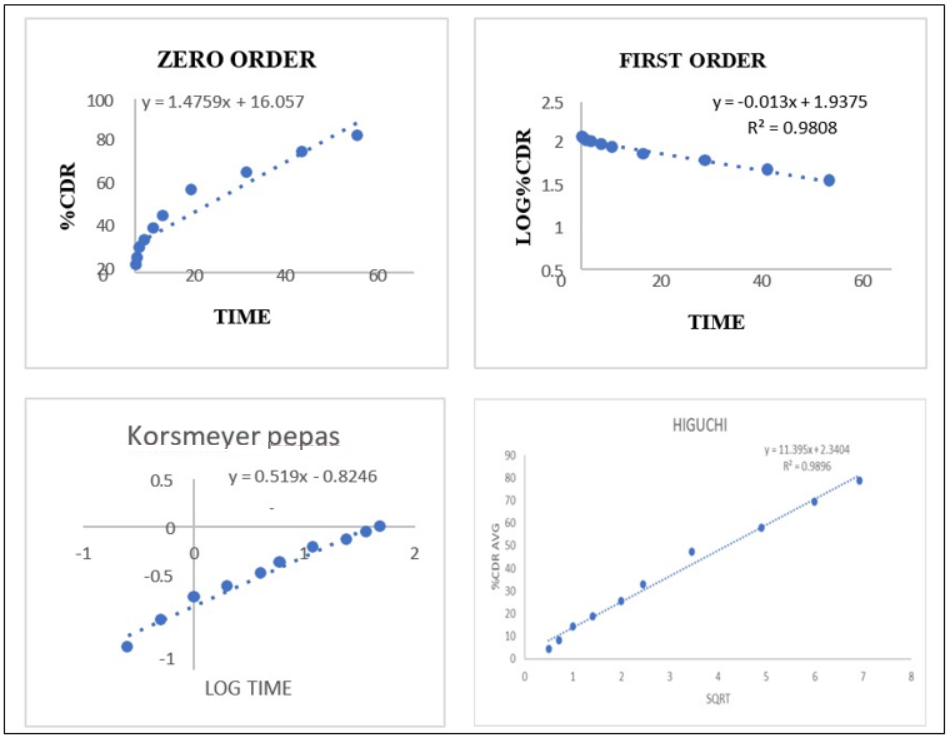

The in vitro release study of REM-loaded nanoparticles, particularly the F4 formulation, utilized a dialysis membrane with a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of 12–14 kDa to facilitate free drug diffusion while retaining the nanoparticle matrix. The release medium, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), was maintained at 50 ml to ensure sink conditions, exceeding three times the saturation solubility of REM (approximately 0.12 mg/ml) to prevent saturation effects. The release profile (fig. 12) exhibited a sustained and controlled release over 48 h, beginning with an initial release of 4.36±0.63% at 0.25 h, which increased to 14.25±4.94% at 1 hour, 32.85±2.48% at 6 h, 47.52±3.14% at 12 h, 57.84±2.52% at 24 h, and culminating at 78.96±0.49% at 48 h. The low standard deviations indicate the reproducibility and stability of the formulation. The biphasic release pattern, marked by an initial moderate release followed by a sustained phase, suggests a mechanism that involves both surface diffusion of loosely bound REM and prolonged release driven by polymer matrix erosion and diffusion. The analysis of release kinetics corroborates this finding, as the first-order model demonstrates the best fit (R² = 0.9808), suggesting a concentration-dependent release mechanism. The Higuchi model showed significant correlation (R² = 0.9396), suggesting a diffusion-controlled mechanism. In contrast, the Korsmeyer-Peppas model produced an n value of 0.519, indicating non-Fickian or anomalous transport that encompasses both diffusion and matrix erosion. The zero-order model exhibited a suboptimal fit, indicating that a constant release rate was not attained. The release behavior of the REM-loaded F4 NS indicates effective sustained drug delivery, potentially enhancing antiviral efficacy, reducing dosing frequency, and improving patient compliance relative to immediate-release formulations [30].

Fig. 13: Represents various drug release kinetic models of REM nanoparticles, REM: Remdesivir

Stability studies

Lyophilized REM-loaded nanoparticles were tested for stability at 25±2 °C and 60±5% relative humidity for 45 d. Reconstituted in filtered water, samples were analyzed for PS, PDI and ZP. Table 3 displays a small particle size increase from 228.3±37.64 nm to 246±0.94 nm and a decrease in PDI from 0.559±0.03 to 0.341±0.04 after 45 d. ANOVA revealed no significant changes (p > 0.05), demonstrating nanoparticles' physical stability. Due to bigger particles settling or aggregating during storage, redispersion results in a more uniform particle distribution, lowering PDI. A stable ZP during the investigation supported the formulation's colloidal stability. While accelerated stability data at 40 °C/75% RH are being obtained, the 45-day study at 25 °C/60% RH provides preliminary formulation stability assurance. In accordance with ICH Q1A(R2) recommendations, long-term stability testing spanning 6 to 12 mo will be performed to validate shelf life and appropriateness for inhalation application.

Table 3: Stability studies

| Stability parameters | Conditions | Test period | ||

At temperature 25±2 °C and 60±5%RH |

15 d | 30 d | 45 d | |

| PS(nm) | 228.3±37.64 | 230± 01.03 | 246±0.94 | |

| PDI | 0.559±0.03 | 0.457±0.021 | 0.341±0.04 | |

| ZP(mV) | -27.3±6.76 | -24.97±1.76 | -28.4±1.6 |

Value expressed as mean±SD, n=3, PS: Particle size, PDI: Polydispersity index, ZP: Zeta potentia

This paper details the formulation and physicochemical analysis of REM-loaded dry powder nanoparticles, emphasizing their potential for pulmonary administration. While essential aerosol performance metrics-namely mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD), fine particle fraction (FPF), and in vitro lung deposition via an Andersen cascade impactor-are presently being examined and will be disclosed in subsequent research, the detected particle size (~200–400 nm) and advantageous surface properties endorse their appropriateness for inhalation. The optimized formulation (F4) exhibited a controlled particle size of 228.3±37.6 nm and a ZP of –27.3±6.76 mV, closely matching previously documented inhalable REM systems, such as those by Sahakijpijarn et al., which indicated particle sizes of 200–300 nm and ZP ranging from –20 to –30 mV. The analogous attributes substantiate the aerodynamic and colloidal properties of the F4 formulation for respiratory targeting.

The choice of Poloxamer 407 and HPMC E3 as excipients was predicated on their recognized biocompatibility, regulatory endorsement, and functional benefits in nanoparticle stabilization and controlled release. Poloxamer 407 functions as a steric stabilizer by diminishing surface tension and inhibiting aggregation, whereas HPMC E3 creates a hydrated matrix that retards drug transport, facilitating sustained release. This aqueous NS method eliminates the necessity for organic solvents in PLGA systems and provides a more regulated release profile. The F4 formulation exhibited near first-order release kinetics (R² = 0.9808), achieving approximately 79% cumulative release over 48 h. This outcome is advantageous compared to the burst-release behavior typically seen in PLGA-based carriers, fulfilling the requirement for both rapid and sustained drug action in pulmonary therapies. While in vivo pharmacokinetic comparisons among pulmonary, intravenous, and oral routes are pending, the existing in vitro results, corroborated by studies on inhalable antiviral nanoparticles, robustly indicate the formulation's potential for superior lung targeting, enhanced bioavailability, and prolonged therapeutic efficacy. These results establish the F4 formulation as a promising, efficient, and therapeutically pertinent choice for the pulmonary administration of REM in antiviral therapy [31-37].

Future perspectives

The invention of dry powder inhalable nanoparticles for COVID-19 treatment offers an innovative and focused strategy with considerable prospects for future advancement. Subsequent investigations should concentrate on in vivo efficacy studies and clinical trials to confirm the safety, pulmonary deposition, and therapeutic results of the nanoparticles in human participants. Enhancing particle engineering techniques to optimise aerodynamic behaviour and deep lung penetration will improve formulation efficacy. There is potential to investigate combination therapies integrating antiviral, anti-inflammatory, or immunomodulatory drugs inside a singular nanoparticle system for synergistic effects. Furthermore, modifying this inhalable nanoparticle platform for various respiratory viral illnesses or novel pathogens could position it as a comprehensive pulmonary medication delivery system. Integrating smart inhaler technology for real-time monitoring and dosage regulation signifies a viable avenue to improve patient adherence and treatment efficacy.

CONCLUSION

The extensive development and evaluation of REM nanoparticles (F4) yielded promising results regarding drug content, PS, morphology, and drug release behavior. By leveraging the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, the nanoparticles were optimized using Poloxamer 407 and HPMC E3, facilitating targeted pulmonary delivery of REM. The drug content estimation was accurate, and SEM analysis revealed a well-controlled surface morphology, which is crucial for enhancing bioavailability. In vitro drug release studies demonstrated a sustained and controlled release, with 78.96% cumulative release over 48 h, supporting prolonged therapeutic effects and reducing the need for frequent dosing. The release mechanism followed a non-Fickian diffusion or erosion-controlled process, typical of nanoparticle-based systems. Stability studies confirmed the formulation's stability, showing no significant changes in PS, PDI, or ZP during storage, ensuring its quality maintenance. Furthermore, DSC thermograms indicated complete drug incorporation within the polymer matrix. Although the formulation shows strong industrial potential, particularly for scale-up, its efficacy and safety should be verified through clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors sincerely thank the Department of Pharmacy, Annamalai University, administration, and faculty for providing the necessary support and facilities for their research. They also thank the faculty for their continuous encouragement and guidance throughout their academic journey.

FUNDING

Nil

ABBREVIATIONS

REM: Remdesivir, RBD: Receptor Binding Domain, ACE: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, TMPRSS: Transmembrane Serine Protease, DSC: Differential Scanning Calorimetry, SEM: Scanning Electron Microscopy, XRD: X-Ray Diffraction, FT-IR: Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, PDI: Poly Dispersity Index, API: Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients, IL: Interleukin, TNF: Tumor Necrosis Factor, RAS: Renin-Angiotensin System, TLRs: Toll-Like Receptors, ACS: Acute Coronary Syndrome, NS: Nano Suspensions, DMSO: DiMethyl Sulfoxide, RPM: Revolutions Per Minute, w/v: Weight/Volume, g/mole: Grams Per Mole, h/h: Hour/Hours, %: Percent, C: Degree Celsius, Nm: Nanometers, min/min: Minutes, g/mg: Gram/Milligram, µg: Microgram, w/w: Weight/Weight, SD: Standard Deviation, ZP: Zeta Potential

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Sagar VS conducted comprehensive research and authored the manuscript. Janakiraman K, Akhil, and Joysa Ruby J played a key role in analyzing the complete dataset and provided guidance and oversight throughout the project's duration.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors affirm the absence of any actual, possible, or perceived conflicts of interest in this research

REFERENCES

Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020 Feb 15;395(10223):470-3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9, PMID 31986257.

Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in germany. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 5;382(10):970-1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468, PMID 32003551.

Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 19;382(12):1177-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737, PMID 32074444.

Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect. 2020 Mar;104(3):246-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022, PMID 32035997.

World Health Organization. Situation reports. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situationreports/.

Cascella M, Rajnik M, Aleem A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features evaluation and treatment of coronavirus (COVID-19). In: Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; 2025 Jan. PMID 32150360.

Teuwen LA, Geldhof V, Pasut A, Carmeliet P. COVID-19: the vasculature unleashed. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020 Jul;20(7):389-91. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0343-0, PMID 32439870.

Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis thrombosis and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 9;383(2):120-8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432, PMID 32437596.

Van De Veerdonk FL, Netea MG, Van Deuren M, Van Der Meer JW, De Mast Q, Bruggemann RJ. Kallikrein kinin blockade in patients with COVID-19 to prevent acute respiratory distress syndrome. eLife. 2020 Apr 27;9:e57555. doi: 10.7554/eLife.57555, PMID 32338605.

Coopersmith CM, Antonelli M, Bauer SR, Deutschman CS, Evans LE, Ferrer R. The surviving sepsis campaign: research priorities for coronavirus disease 2019 in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 1;49(4):598-622. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004895, PMID 33591008.

Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jul 1;5(7):811-8. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017, PMID 32219356.

Lin HX, Cho S, Meyyur Aravamudan V, Sanda HY, Palraj R, Molton JS. Remdesivir in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment: a review of evidence. Infection. 2021 Jun;49(3):401-10. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01557-7, PMID 33389708.

Pennington E, Bell S, Hill JE. Should video laryngoscopy or direct laryngoscopy be used for adults undergoing endotracheal intubation in the pre-hospital setting? A critical appraisal of a systematic review. J Paramed Pract. 2023;15(6):255-9. doi: 10.1002/14651858, PMID 38812899.

Gottlieb RL, Vaca CE, Paredes R, Mera J, Webb BJ, Perez G. Early remdesivir to prevent progression to severe COVID-19 in outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jan 27;386(4):305-15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116846, PMID 34937145.

Lee TC, Murthy S, Del Corpo O, Senecal J, Butler Laporte G, Sohani ZN. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022 Sep;28(9):1203-10. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.04.018, PMID 35598856.

Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A, Cortes J, Shah S, Ayala M. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jun 17;362(24):2260-70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002315, PMID 20525995.

Bakheit AH, Darwish H, Darwish IA, Al Ghusn AI. Remdesivir. Profiles Drug Subst Excip Relat Methodol. 2023;48:71-108. doi: 10.1016/bs.podrm.2022.11.003, PMID 37061276.

Aman KS, Alka V, Shivam J, Abhishek M, Imran K, Harsh S. Nanosuspension as novel drug delivery approach: a review. Int J Pharm Res App. 2024 Mar;9(2):472-83. doi: 10.35629/7781-0902472483.

Verma G, Mishra MK. Pharmaceutical preformulation studies in formulation and development of new dosage form: a review. Int J Pharm Res Rev. 2016 Oct;5(10):12-20.

Gorniak A, Czapor Irzabek H, Zlocinska A, Gawin Mikolajewicz A, Karolewicz B. Screening of fenofibrate simvastatin solid dispersions in the development of fixed-dose formulations for the treatment of lipid disorders. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Feb 10;15(2):603. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15020603, PMID 36839925.

Humeniuk R, Mathias A, Cao H, Osinusi A, Shen G, Chng E. Safety tolerability and pharmacokinetics of remdesivir an antiviral for treatment of COVID-19 in healthy subjects. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13(5):896-906. doi: 10.1111/cts.12840, PMID 32589775.

Afifi SA, Hassan MA, Abdelhameed AS, Elkhodairy KA. Nanosuspension: an emerging trend for bioavailability enhancement of etodolac. Int J Polym Sci. 2015;2015(2):1-16. doi: 10.1155/2015/938594.

Thummar K, Pandya M, Patel N, Rawat F, Chauhan S. Quality by design based development and validation of UV-spectrometric method for the determination of remdesivir in bulk and marketed formulation. Int J Pharm Sci Drug Res. 2022;14(4):385-90. doi: 10.25004/IJPSDR.2022.140404.

Sahakijpijarn S, Moon C, Koleng JJ, Christensen DJ, Williams RO. Development of remdesivir as a dry powder for inhalation by thin film freezing. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Oct 22;12(11):1002. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12111002, PMID 33105618.

Sahu BP, Hazarika H, Bharadwaj R, Loying P, Baishya R, Dash S. Curcumin docetaxel co-loaded nanosuspension for enhanced anti-breast cancer activity. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016 Aug;13(8):1065-74. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2016.1182486, PMID 27124646.

Chary SS, Bhikshapathi DV, Vamsi NM, Kumar JP. Optimizing entrectinib nanosuspension: quality by design for enhanced oral bioavailability and minimized fast-fed variability. BioNanoScience. 2024 May;14(4):4551-69. doi: 10.1007/s12668-024-01462-5.

Al Ashmawy AZ, Balata GF. Formulation and in vitro characterization of nanoemulsions containing remdesivir or licorice extract: a potential subcutaneous injection for coronavirus treatment. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2024 Feb;234:113703. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2023.113703, PMID 38096607.

Patton JS, Byron PR. Inhaling medicines: delivering drugs to the body through the lungs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007 Jan;6(1):67-74. doi: 10.1038/nrd2153, PMID 17195033.

Zhang L, Zhou R. Structural basis of the potential binding mechanism of remdesivir to SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Phys Chem B. 2020;124(32):6955-62. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c04198, PMID 32521159.

Muller RH, Keck CM. Twenty years of drug nanocrystals: where are we and where do we go? Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;80(1):1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.09.012, PMID 21971369.

Mansour HM, Rhee YS, Wu X. Nanomedicine in pulmonary delivery. Int J Nanomedicine. 2009;4:299-319. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s4937, PMID 20054434.

Labiris NR, Dolovich MB. Pulmonary drug delivery. Part I: physiological factors affecting therapeutic effectiveness of aerosolized medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003 Dec;56(6):588-99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01892.x, PMID 14616418.

Sahakijpijarn S, Smyth HD, Miller DP, Weers JG. Post inhalation cough with therapeutic aerosols: formulation considerations. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020 Jul;165-166:127-41. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.05.003, PMID 32417367.

Srinivasan G, Shetty A. Advancements in dry powder inhaler. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(2):8-12. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i2.14282.

Khalifa NE, Nur AO, Osman ZA. Artemether loaded ethyl cellulose nanosuspensions effects of formulation variables physical stability and drug release profile. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2017 Jun 1;9(6):90-6. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2017v9i6.18321.

Patel RK, Singh PK, Pandey R, Patel B, Mishra S. Amino acid status of bovine milk under seasonal variation around Singrauli district. Int J Chem Res. 2021;5(3):1-4. doi: 10.22159/ijcr.2021v5i3.170.

Aher SS, Sagar TM, Saudagar RB. Nanosuspension: an overview. Integr J Curr Pharm Rese. 2017 May;9(3):19-23. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2017.v9i3.19584.