Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 159-167Original Article

DESIGN AND IN SILICO EVALUATION OF PHENOXY ACETAMIDE DERIVATIVES AS POTENTIAL ANTIDIABETIC AGENTS

INDHUMATHI S.1, S. SREE NITHI1, GOBIANANTH1, MOHD ABDUL BAQI2*, N. VENKATHESHAN1, GANESH MEENA2, KOPPULA JAYANTHI1*

1Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Arulumigu Kalasalingam College of Pharmacy, Kalasalingam Academy of Research and Education, Krishnan Koil, Tamil Nadu, India. 2Department of Pharmaceutics, Arulumigu Kalasalingam College of Pharmacy, Kalasalingam Academy of Research and Education, Krishnan Koil, Tamil Nadu, India. 3Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Chemistry, Arulumigu Kalasalingam College of Pharmacy, Kalasalingam Academy of Research and Education, Krishnan Koil, Tamil Nadu, India

*Corresponding author: Koppula Jayanthi; *Email: jayanthi.k@akcp.ac.in

Received: 06 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 04 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study explores the interactions of phenoxy acetamide derivatives with AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a key enzyme in metabolic regulation. The goal is to evaluate the AMPK activation potential of these compounds using in silico approaches.

Methods: Molecular docking was performed using the Glide module to assess binding affinity. Binding free energy (ΔG_bind) was calculated using the MM-GBSA method, and pharmacokinetic profiles were evaluated via ADME predictions using QikProp.

Results: Among the tested compounds, 3-chlorophenyl phenoxy acetamide (compound 5) exhibited the highest XP-docking score of –5.22 kcal/mol and a ΔG_bind of –97.78 kcal/mol, indicating strong binding with the AMPK active site. Key interactions included hydrogen bonding with residues PRO127, MET84, ARG117, and TYR120. ADME analysis revealed that all compounds showed low CNS penetration (QPlog BB<–1) and acceptable intestinal absorption (Caco-2>300 nm/s).

Conclusion: Compound 5 demonstrates significant AMPK activation potential and favorable ADME properties, suggesting its promise as a lead compound for type II diabetes therapy.

Keywords: Molecular docking, MM-GBSA, Phenoxy-acetamide, AMPK, ADME, Type II diabetes

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54892 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by persistent hyperglycaemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. It poses a significant global health challenge, affecting over 537 million adults as of 2021, with projections estimating an increase to 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045 [1]. Among its types, type 2 diabetes mellitus T2DM accounts for more than 90% of all diabetes cases and is predominantly associated with insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency [2]. The pathophysiology of T2DM involves a complex interplay of impaired insulin signaling, reduced glucose uptake by peripheral tissues such as skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, hepatic overproduction of glucose, and chronic inflammation [3]. If left untreated, T2DM can lead to serious complications, including cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, and increased mortality. Globally, diabetes was responsible for approximately 6.7 million deaths in 2021, underscoring the urgent need for effective and sustainable therapeutic strategies. Management of T2DM typically involves lifestyle interventions and pharmacological therapy. Insulin, discovered in the early 1920s, was the first antidiabetic drug and remains essential, particularly for type 1 diabetes. The introduction of oral antidiabetic agents, notably sulfonylureas and biguanides such as metformin, expanded treatment options significantly. Metformin continues to be the first-line treatment due to its efficacy, safety profile, and affordability [4]. In recent years, new drug classes have emerged, targeting diverse mechanisms of glucose regulation. These include thiazolidinediones, which enhance insulin sensitivity; DPP-4 inhibitors, which prolong incretin hormone activity; SGLT2 inhibitors, which reduce renal glucose reabsorption; and GLP-1 receptor agonists, which enhance insulin secretion and promote weight loss. Despite these advancements, the therapeutic landscape is still challenged by issues such as drug resistance, adverse effects, and the inability to fully prevent disease progression in many patients. Given the multifactorial nature of T2DM, there remains a pressing need to develop new therapeutic agents that are safer, more effective, and capable of targeting multiple pathways involved in disease progression. In this context, in silico approaches have become an essential tool in modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to identify and optimize lead compounds rapidly and cost-effectively [5]. These computational techniques facilitate virtual screening and prediction of molecular interactions with key antidiabetic targets, streamlining early-phase drug development. Phenoxy acetamide derivatives have recently gained attention due to their structural versatility and broad biological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antidiabetic potential [6]. Their chemical framework allows for functional modifications that may enhance binding affinity and selectivity toward metabolic targets. One particularly promising target in the treatment of T2DM is AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a key regulator of cellular energy homeostasis. Activation of AMPK enhances glucose uptake, fatty acid oxidation, and insulin sensitivity while suppressing hepatic gluconeogenesis. Recent evidence also suggests that AMPK activation can stimulate pancreatic β-cell function and promote insulin secretion, providing a dual therapeutic benefit. Therefore, the identification of small molecules capable of activating AMPK offers a strategic approach to improving glycemic control and preserving β-cell function in diabetic patients. The present study aims to design and evaluate novel phenoxy acetamide derivatives using in silico methodologies to identify promising candidates for antidiabetic therapy. Special emphasis is placed on the interaction of these compounds with AMPK, with the goal of identifying activators that can enhance insulin production and improve metabolic regulation. Molecular docking studies will be employed to investigate their binding affinity and potential efficacy. The findings of this research are expected to contribute to the development of more effective therapeutic agents for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein preparation

The protein structure was prepared using the Protein Preparation Wizard at physiological pH (7.0). Key catalytic residues, such as lysine, were assigned standard protonation states appropriate for this pH. The Schrödinger Suite was employed for computational studies, including molecular docking, MM-GBSA calculations, and ADME predictions. The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) protein structure (PDB ID: 6C9F) was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank for docking analyses. Ligand structures were either obtained from existing databases or designed based on novel 1,3-diamino-3-(dimethylamino)allylidene)amino)phenoxy)-N-phenylacetamide derivatives.

Molecular docking

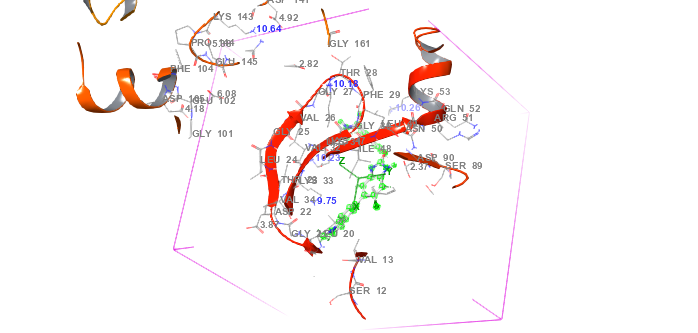

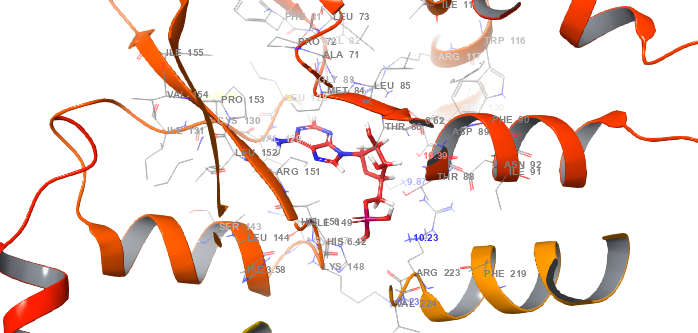

Molecular docking was employed to predict the binding affinities and interaction mechanisms between ligands and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). The objective was to identify the most favorable docked conformations based on e-model, energy, and docking scores. Schrödinger Suite 2021-4 was utilized to process the X-ray crystal structure of AMPK (PDB ID: 6C9F, 2.92 Å resolution), which was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank[7] and prepared using Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard. This process involved adding hydrogen atoms, optimizing protonation states, and ensuring structural integrity for docking studies (Schrödinger, 2021-4). To prevent interference, crystallographic water molecules were removed[8], and any missing side chains were reconstructed using the Prime module [9]. Ligand structures were processed using LigPrep, which generated various conformations and tautomers for ten compounds[10]. Docking simulations were conducted using the OPLS3-2005 force field, recognized for its accuracy in modeling non-covalent interactions while maintaining computational efficiency [11]. The active site was defined using a 20 Å grid box, centered (x = 12.45, y = 18.78, z = 5.63) based on the co-crystallized ligand position on the co-crystallized ligand (fig. 1), to refine the docking calculations. Docking simulations were performed using Glide XP, a robust method for evaluating ligand binding conformations [12]. Docking was performed using the Glide XP protocol with a van der Waals scaling factor of 0.80 and a partial charge cutoff of 0.15. A maximum of 10 poses were generated per ligand. The best docked conformations were selected based on Glide energy, docking scores, and e-model values (Schrödinger, 2021-4). Protein-ligand complexes were visualized to analyze key interactions and conformational stability, as illustrated in fig. 2.

Fig. 1: Protein-ligand interaction grid complex (PDB id: 6C9F) in molecular docking

Fig. 2: Protein-ligand interaction complex (PDB id: 6C9F) in molecular docking

Binding free energy calculations using prime MM-GBSA

The binding free energy of each protein-ligand complex was determined using the Prime MM-GBSA method within Schrödinger Suite 2021-4. This approach provides a comprehensive evaluation of binding affinity by integrating multiple energy contributions. Prime MM-GBSA combines molecular mechanics energies with implicit solvation models to estimate the free energy of binding. The process involves several critical steps, including energy minimization of each protein-ligand complex. This step is performed using the OPLS3e force field, a highly accurate model designed for biomolecular interactions. Energy minimization ensures that the system reaches a stable conformation, improving the reliability of binding energy calculations. The VSGB 2.0 (Variable Dielectric Generalized Born) implicit solvation model was employed to account for solvation effects. This model provides a detailed representation of hydrogen bonding, self-contact interactions, and hydrophobic effects [13]. Solvation effects play a crucial role in ligand binding, influencing molecular interactions within a biological environment. Molecular Mechanics Energy – Represents van der Waals and electrostatic interactions between the protein and ligand. Generalized Born Solvation Energy – Accounts for implicit solvation effects that influence molecular interactions. Surface Area Term – Reflects the hydrophobic effect, contributing to ligand binding stability. The final binding energy is obtained by subtracting the total free energies of the unbound protein and ligand from that of the protein-ligand complex. This calculation provides an estimate of the ligand’s binding affinity to the target protein, offering valuable insights into stability and interaction strength. Additionally, the MM-GBSA method incorporates physics-based corrections to improve accuracy. These corrections address interaction effects that may not be fully captured by standard energy terms, enhancing the reliability of binding energy predictions. Prime MM-GBSA binding free energy calculations were performed after energy minimization of the protein–ligand complex, as well as the separate receptor and ligand. A single minimized snapshot was used for each complex.

ADME calculation

The ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) properties of each protein-ligand complex were evaluated using Schrödinger Suite 2021-4. This assessment involved analyzing protein-ligand systems where protein structures were obtained from experimental data or modelled when required. Ligands were prepared following standard molecular modeling protocols to ensure consistency in structure and conformation. ADME predictions were conducted using the Prime QIKPROP method in Schrödinger Suite, a highly efficient tool for estimating pharmacokinetic properties. The OPLS3-2005 force field was applied, an advanced version of the Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations (OPLS) force field. This updated model is recognized for its improved accuracy in simulating protein-ligand interactions and predicting molecular properties [14]. To achieve precise solvation energy estimations, the VSGB 2.0 (Variable Dielectric Generalized Born) solvation model was utilized. This model effectively captures the dynamic nature of the solvent environment within protein-ligand complexes, ensuring a more realistic representation of solvation effects [15]. Protein and ligand structures were prepared using Schrödinger's molecular modeling tools, which included energy minimization and protonation state assignment at physiological pH. To enhance accuracy, each complex underwent further energy minimization using the OPLS3-2005 force field, ensuring stable low-energy conformations. Finally, the Prime QIKPROP tool was employed to estimate ADME properties, providing precise predictions of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion characteristics. These predictions were based on empirical models, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of pharmacokinetic profiles. ADME properties were predicted using QikProp, and the following descriptors were reported: QPlog Po/w, QPlog HERG, QPlog BB, Caco-2 permeability, human oral absorption, PSA, and compliance with Lipinski’s Rule of Five. Thresholds used for evaluation included QPlog HERG<–5.0 (low cardiotoxicity risk) and Caco-2>300 nm/s (good intestinal absorption).

Compounds used

The study focused on several chemical structures derived from the phenoxy-N-phenylacetamide core, which exhibit anti-diabetic properties by activating the AMPK enzyme, similar to the mechanism of metformin. These compounds contained both polar and non-polar functional groups, which play a crucial role in AMPK activation. The polar groups included Cl, NO₂, NH₂, OH, CN, and F, while the non-polar groups included CH₃, C₆H₅, and Br. The presence of these functional groups enhanced the activation potential of the AMPK enzyme, making these compounds promising candidates for diabetes treatment.

RESULTS

Docking results and analysis

Docking studies were performed using the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) crystal structure (PDB ID: 6C9F) with Schrödinger Suite 2021-4. The virtual screening approach ensured that ligand conformations maintained a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 1.7 Å relative to the co-crystallized structure. To eliminate functional groups that might negatively impact ligand interactions, Lipinski’s rule of five was applied. Several Glide XP-docking parameters were considered to evaluate the screening results, including the Glide score, e-model, van der Waals energy (E_vdw), Coulomb energy (E_coul), and the overall docking energy (Energy).

Table 1: The XP-docking scores for compounds 1–10 in AMPK catalytic pocket (PDB ID: 6C9F)

| Compound | Gscore | Gvedw | Gecou | Genergy | Emodel |

| 1 | -3.52 | -40.66 | -6.28 | -46.95 | -0.70 |

| 2 | -5.59 | -38.85 | -10.11 | -48.96 | -1.66 |

| 3 | -4.20 | -41.70 | -6.06 | -47.77 | -0.04 |

| 4 | -3.21 | -44.32 | -5.71 | -50.04 | -0.89 |

| 5 | -5.22 | -34.89 | -12.61 | -47.51 | -1.57 |

| 6 | -5.23 | -41.74 | -9.79 | -51.54 | -1.28 |

| 7 | -4.08 | -38.69 | -7.52 | -46.22 | -0.7 |

| 8 | -3.91 | -43.45 | -3.70 | -47.16 | 0 |

| 9 | -3.03 | -43.15 | -5.70 | -48.86 | -0.11 |

| 10 | -4.43 | -41.52 | -6.68 | -48.20 | -0.62 |

| Metformin | -3.16 | -12.80 | -11.86 | -24.67 | -2.44 |

aGlide Score, bGlide Van der Waals Energy, cGlide Coulomb Energy, dGlide Energy, eGlide E-model

Docking analysis revealed that all compounds exhibited favorable binding activity compared to Metformin (standard drug), with compounds 2, 5, and 6 achieving the highest Glide scores of-5.59 kcal/mol,-5.22 kcal/mol, and-5.23 kcal/mol, respectively, indicating strong binding affinity. Compounds 3, 7, and 10 displayed the second-highest Glide scores of-4.20 kcal/mol,-4.08 kcal/mol, and-4.43 kcal/mol, surpassing compounds 4, 1, and 8, which exhibited Glide scores of-3.21 kcal/mol,-3.52 kcal/mol, and-3.91 kcal/mol, respectively. Despite slightly lower binding affinities, these compounds still demonstrated substantial binding potential. However, compound 9 showed weaker binding interactions, with a Glide score of-3.03 kcal/mol. Metformin, used as a reference, exhibited a Glide score of-3.16 kcal/mol, indicating moderate binding affinity. Notably, compounds 2, 6, and 5 demonstrated robust interaction metrics, including van der Waals energy (E_vdw) of-38.85 kcal/mol,-41.74 kcal/mol, and-34.89 kcal/mol, Coulomb energy (E_coul) of-10.11 kcal/mol,-9.79 kcal/mol, and-12.61 kcal/mol, total docking energy (E_energy) of-48.96 kcal/mol,-51.54 kcal/mol, and-47.51 kcal/mol, and E-model (Gemodel) values of-1.66 kcal/mol,-1.28 kcal/mol, and-1.57 kcal/mol. These findings highlight compounds 2, 6, and 5 as the most promising candidates, demonstrating binding affinity comparable to metformin. Their strong interactions with AMPK make them potential drug candidates for further research. Table 1 indicating that values represent single best-scoring poses.

Binding free energy contributions using MM-GBSA

The binding free energy (ΔG_bind) for each compound in complex with AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (PDB ID: 6C9F) is summarized in table 2, as determined using the MM-GBSA technique. The key energy components contributing to ΔG_bind include Coulombic energy (ΔG_Coul), hydrophobic energy (ΔG_Lip), hydrogen bonding energy (ΔG_HB), and van der Waals energy (ΔG_VdW).

Table 2: Binding free energy (MM-GBSA) contribution (kcal/mol) for compounds 1–10 in AMPK complexes

| Compound | GBind | GCoul | GCov | GHB | GLipo | GSolv | Genergy | Gvdw |

| 1 | -84.88 | -66.53 | 15.89 | -3.36 | -19.63 | 39.93 | 5.89 | -50.36 |

| 2 | -50.27 | -5.19 | -6.85 | 0.34 | -11.16 | 11.65 | 7.04 | -36.95 |

| 3 | -67.64 | -30.44 | 2.51 | 1.05 | -15.08 | 31.27 | 10.56 | -52.80 |

| 4 | -54.77 | -26.68 | 6.26 | -3.59 | -14.83 | -25.14 | 9.33 | -42.19 |

| 5 | -97.78 | -28.26 | -0.47 | -3.39 | -10.26 | -9.00 | 2.48 | -44.00 |

| 6 | -70.42 | -23.29 | -12.38 | 0.95 | -10.40 | 11.87 | 5.81 | -35.23 |

| 7 | -93.66 | -36.19 | 0.50 | -4.5 | -17.65 | 26.78 | 8.53 | -58.07 |

| 8 | -50.78 | -4.25 | 3.15 | 6.82 | -19.32 | 10.89 | 9.04 | -52.43 |

| 9 | -59.62 | -27.15 | 6.48 | -2.54 | -13.02 | 34.64 | 9.42 | -54.56 |

| 10 | -51.85 | -15.36 | -5.48 | 2.34 | -11.62 | 29.55 | 4.57 | -49.06 |

| Metformin | -41.76 | -32.85 | 4.89 | -5.91 | 2.60 | 6.94 | 6.20 | -18.82 |

a Free Energy of Binding, b Coulomb Energy, ccovalentd Hydrogen Bonding Energy, eHydrophobic Energy (non-polar contribution estimated by solvent accessible surface area),f solvent g Van der Waals Energy.

Compound 5 exhibited the highest binding free energy of-97.78 kcal/mol, with major contributions from Coulombic energy (-28.26 kcal/mol), hydrophobic energy (-10.26 kcal/mol), and van der Waals energy (-44.00 kcal/mol), indicating significant binding potential. Similarly, compound 7 showed a strong binding free energy of-93.66 kcal/mol, supported by a high Coulombic energy of-36.19 kcal/mol and a moderate hydrophobic contribution of-17.65 kcal/mol. Compound 1 displayed notable characteristics with a binding free energy of-84.88 kcal/mol, featuring a positive Coulombic energy of-66.53 kcal/mol, a high hydrophobic energy of-19.63 kcal/mol, and a lower van der Waals energy of-50.36 kcal/mol. Meanwhile, compound 2 demonstrated weaker binding interactions with a binding free energy of-50.27 kcal/mol, which was lower than that of compound 5. Compound 8 recorded the lowest binding free energy of-50.78 kcal/mol, with minimal contributions from hydrophobic energy (-19.32 kcal/mol) and Coulombic energy (-4.25 kcal/mol). In comparison, the standard drug metformin exhibited a binding free energy of-41.76 kcal/mol, significantly lower than all the tested compounds, indicating that the newly identified compounds may have stronger binding affinities toward AMPK. Among the energy components, van der Waals interactions accounted for approximately 40–45% of the total binding free energy (ΔG_bind) across the top five compounds. Coulombic contributions ranged between 25–35%, supporting the significance of both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions in stabilizing ligand binding.

Hydrogen bonding and amino acid interactions

Table 3 provides a detailed summary of the hydrogen bonds formed between each compound and the amino acid residues within the catalytic pocket of AMPK (PDB ID: 6C9F). These interactions play a crucial role in determining the binding affinity and stability of the protein-ligand complexes, significantly influencing overall molecular interactions and the potential activator efficacy of the compounds.

Table 3: Number of hydrogen bonds and specific amino acid residues involved in compound interactions within the AMPK catalytic pocket (PDB ID: 6C9F)

| Compound | H-bond | Pi-Pi stacking | Amino acids |

| 1 | 5 | 0 | LYS 143, ARG 222, THR 33, ARG 117, MET 36 |

| 2 | 5 | 0 | ARG 117, LYS 126, LYS 163, ARG 131, ARG 222 |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | ASN 147, LYS 148, ARG 223 |

| 4 | 4 | 0 | ARG 117, TYR 120, ARG 223, VAL 129 |

| 5 | 4 | 0 | PRO 127, MET 84, ARG 117, TYR 120 |

| 6 | 5 | 0 | ARG 222, THR 33, ARG 151, HIS 150, ASN 147 |

| 7 | 5 | 0 | ARG 222, MET 34, PRO 127, ARG 117, TYR 120 |

| 8 | 4 | 0 | ARG 222, LYS 143, VAL 122, MET 36 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | PRO 12 |

| 10 | 4 | 0 | ARG 151, ARG 117, MET 34, TYR 120 |

| Metformin | 4 | 0 | ARG 117, MET 84, ARG 223, ASP 89 |

Each compound's hydrogen bond count and interacting amino acid residues are included in the table.

Table 3 summarizes the interactions between each compound and the AMPK catalytic pocket. Most compounds exhibited strong hydrogen bond interactions with key receptor amino acids. Compounds 1, 2, 6, and 7 formed the highest number of hydrogen bonds, with five interactions involving residues such as LYS 143, ARG 222, THR 33, ARG 117, MET 36, LYS 126, LYS 163, ARG 131, HIS 150, ASN 147, MET 34, PRO 127, and TYR 120. This extensive hydrogen bonding indicates that compounds 2 and 6 have strong binding affinity and potential effectiveness as AMPK activators. Compounds 4, 5, 8, and 10 established four hydrogen bonds with key residues, including ARG 117, TYR 120, ARG 223, VAL 129, PRO 127, MET 84, LYS 143, VAL 122, and MET 36. While their interactions were slightly fewer than those of compounds 2 and 6, they still demonstrated significant binding potential. Quantitative analysis revealed that ARG117 was involved in hydrogen bonding interactions in 9 out of 10 compounds, while TYR120 interacted with 6 out of 10 compounds. Other frequently engaged residues included MET84 (4/10) and PRO127 (3/10), indicating consistent binding within the AMPK catalytic pocket. Compound 3 formed three hydrogen bonds, interacting with ASN 147, LYS 148, and ARG 223. Despite having fewer hydrogen bonds, it maintained notable interactions within the catalytic pocket. In comparison, Metformin, the standard drug (STD), formed four hydrogen bonds with ARG 117, MET 84, ARG 223, and ASP 89, indicating a moderate level of interaction. Notably, several tested compounds exhibited better interactions than the standard drug, highlighting their potential as effective AMPK activators.

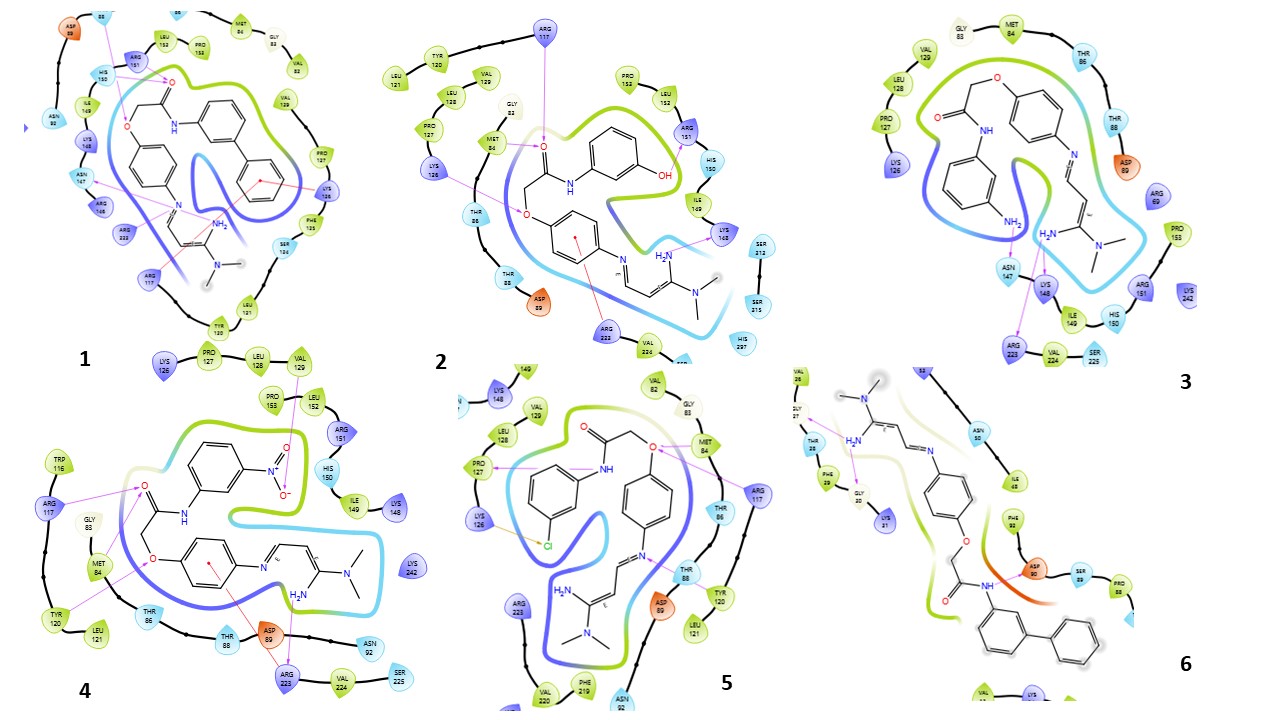

Fig. 3: Compound 1-10 with standard drug 2D interaction diagrams in the AMPK catalytic pocket PDB ID: (6C9F)

Fig. 3 presents the 2D interaction diagrams of the 10 studied compounds, illustrating their interactions within the AMPK catalytic pocket (PDB ID: 6C9F). These diagrams highlight key molecular interactions. Hydrogen bonding interactions involve functional groups such as carbonyl (C=O), amines (NH2, NH), oxygen-containing groups (O), nitro (N), cyanide (CN), and hydroxyl (OH), forming bonds with receptor residues, which are crucial for stabilizing the ligand-receptor complex. Hydrophobic interactions occur between aromatic residues in the receptor and aromatic rings in the compounds, facilitating π-cation interactions. Additionally, the chlorine (Cl) group in the compounds engages in halogen bond interactions with the receptor, further enhancing binding stability. These visual representations in fig. 3 provide an intuitive understanding of how different functional groups contribute to effective binding with AMPK, highlighting the specific residues involved in each interaction.

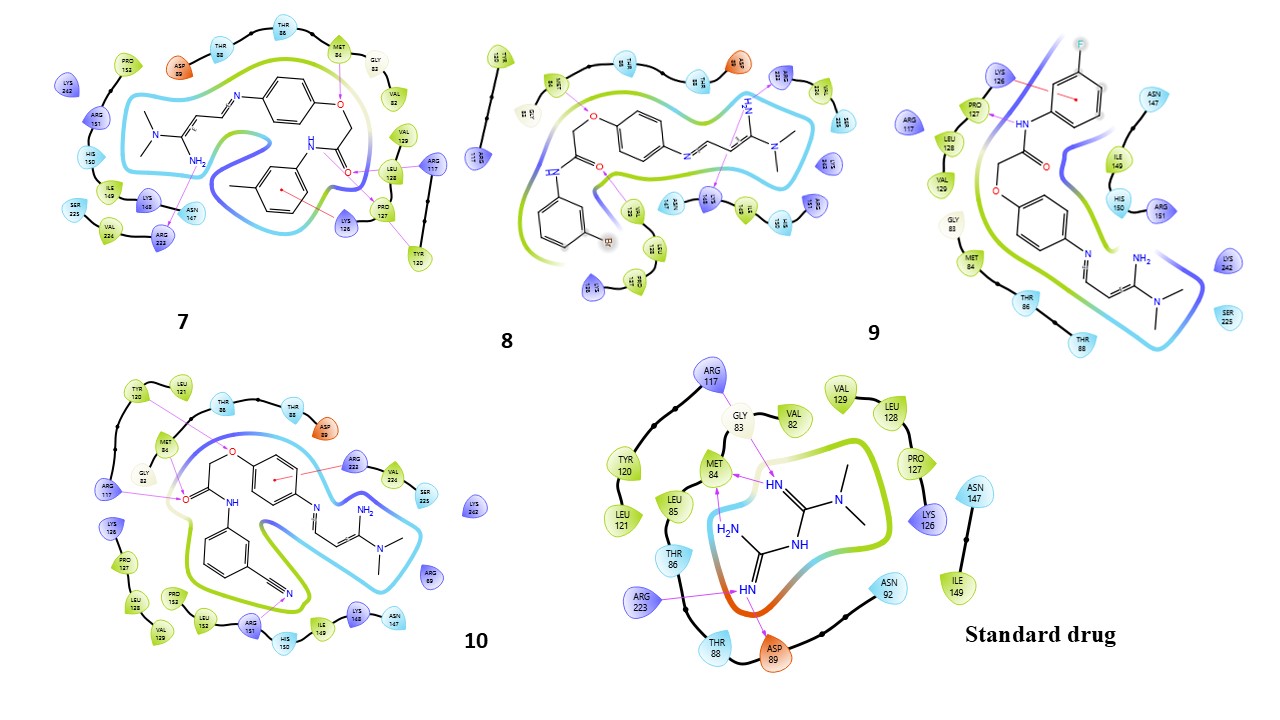

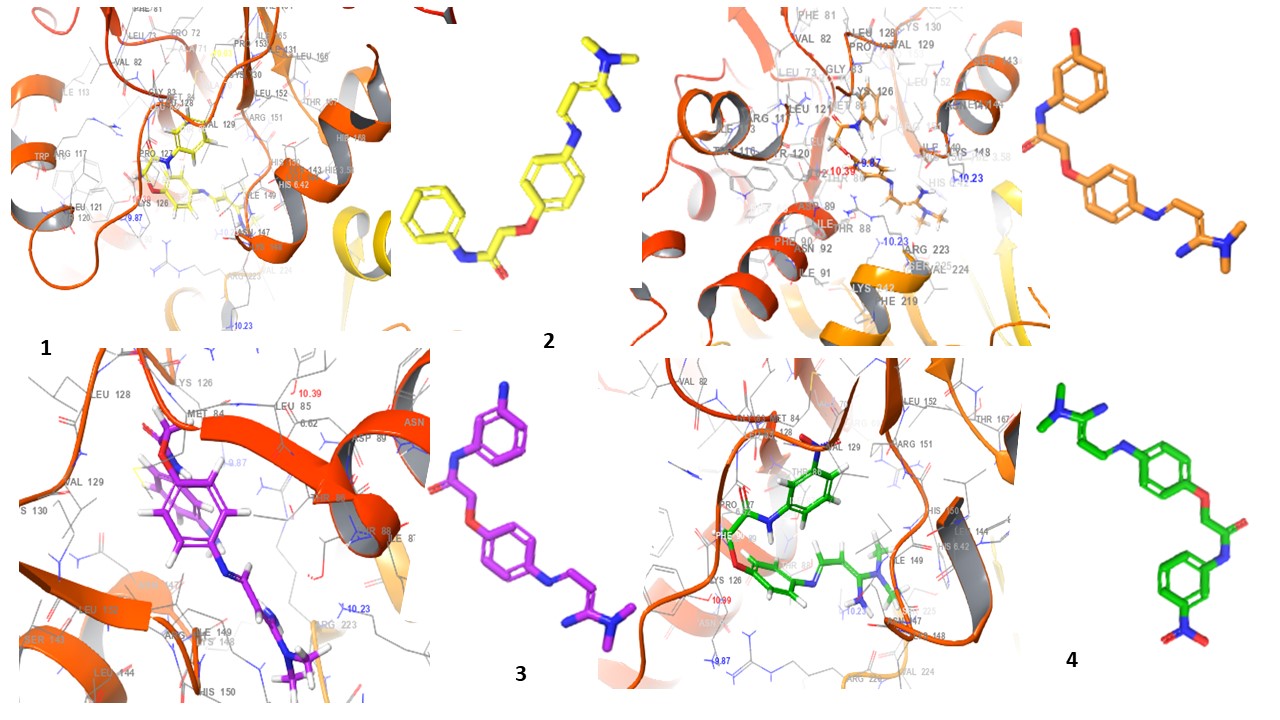

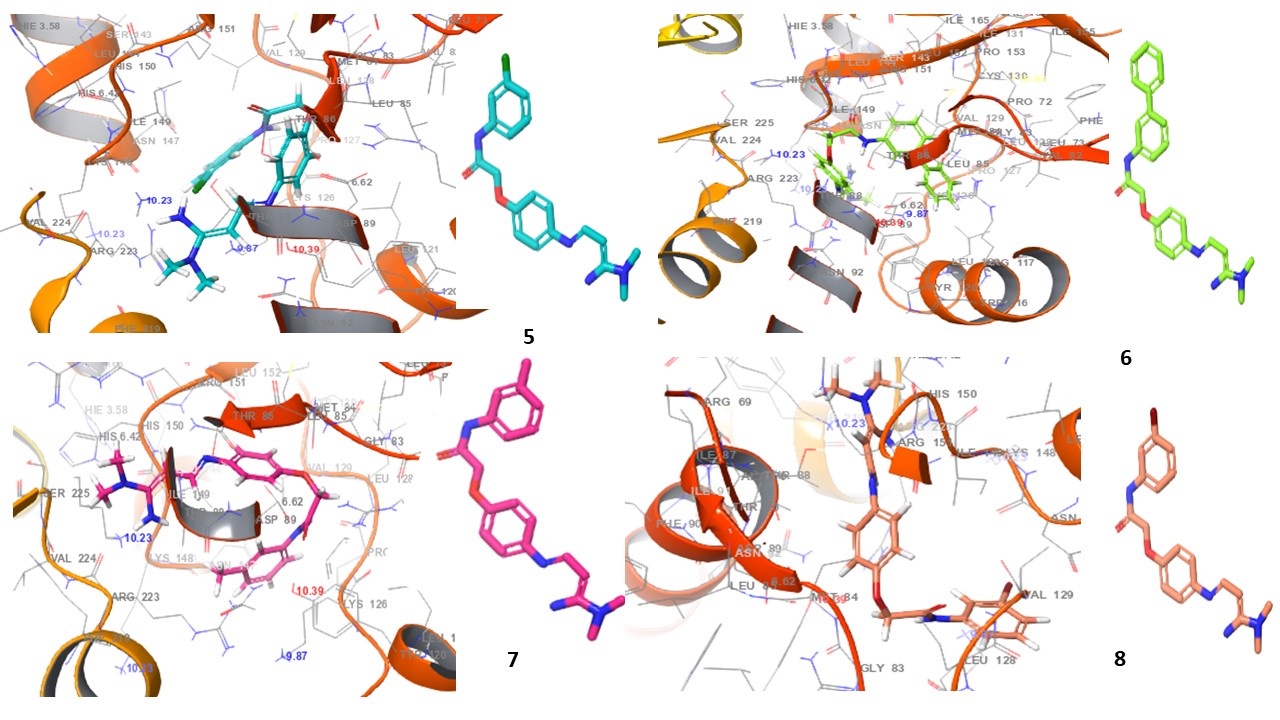

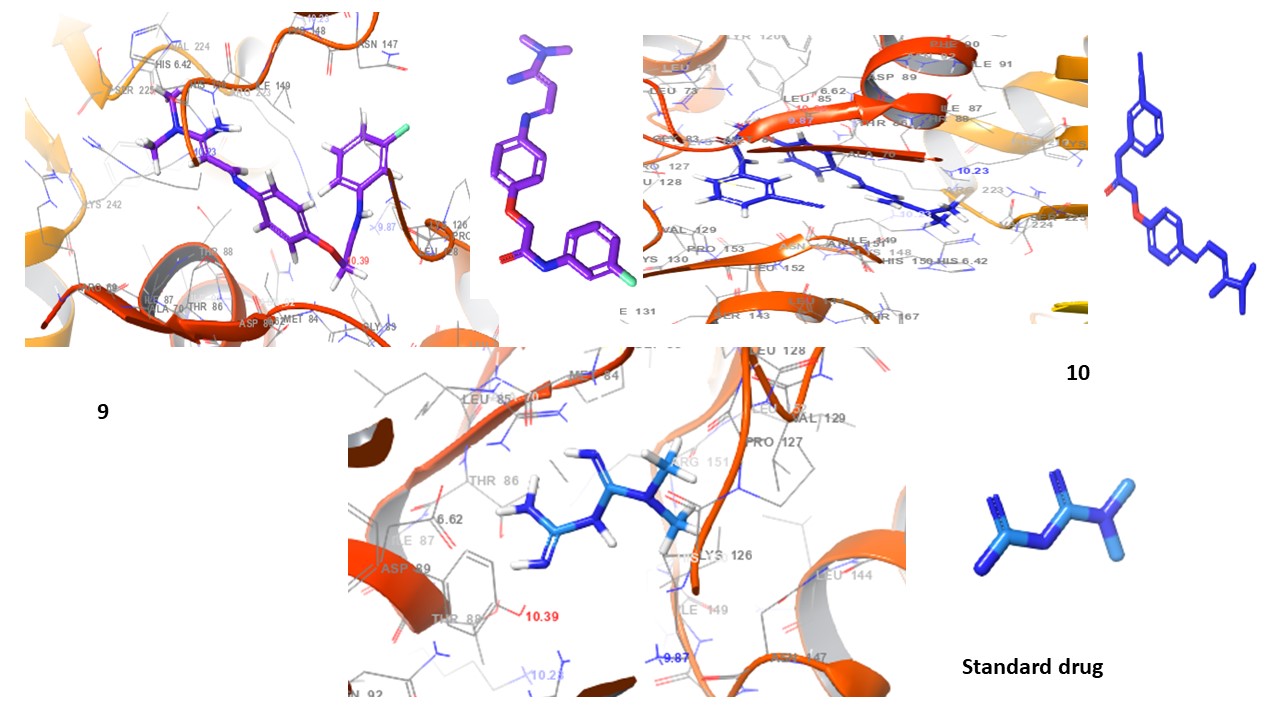

Fig. 4: 3D Interaction diagrams of compounds (1-10) and standard drug in the AMPK catalytic pocket PDB ID: (6C9F)

Fig. 4 presents the 3D interaction diagrams of the ten studied compounds within the AMPK catalytic pocket (PDB ID: 6C9F). These diagrams depict the spatial arrangement of each compound, showcasing its binding orientation and fit within the receptor’s active site. The visualizations highlight key molecular interactions, including hydrogen bonding involving functional groups such as carbonyls (C=O), amines (NH2, NH), oxygen-containing groups (O), nitro (N), cyanide (CN), and hydroxyls (OH), which interact with receptor residues to enhance stability. Hydrophobic interactions are also observed, where aromatic residues in the receptor engage with the aromatic rings of the compounds, facilitating π-cation interactions. Additionally, the chlorine (Cl) group in the compounds participates in halogen bond interactions with the receptor. This 3D perspective provides valuable insights into molecular contacts, ligand-receptor stability, and the overall impact of these interactions on binding affinity and receptor function.

ADME study results

The ADME properties of the ten compounds were analyzed to evaluate their pharmacokinetic and safety profiles. Table 4 summarizes the results, followed by a detailed interpretation of these findings.

Table 4: ADME properties of compounds 1-10 and standard drug

| Comp | CNS | SASA | Donar HB | Accept HB | Qplog Po/w | Qplog HERG | QPP Caco(nm/s) |

QPlogBB | Human oral absorption | PSA | Rule of five |

| 1 | -2 | 654.437 | 3 | 5.25 | 3.627 | -6.212 | 1101.86 | -1.003 | 3 | 79.266 | 0 |

| 2 | -2 | 681.127 | 4 | 6 | 3.02 | -6.256 | 406.189 | -1.583 | 3 | 100.15 | 0 |

| 3 | -2 | 691.486 | 4.5 | 6.25 | 2.759 | -6.442 | 279.04 | -1.801 | 3 | 104.85 | 0 |

| 4 | -2 | 676.578 | 3 | 6.25 | 2.943 | -5.847 | 158.38 | -1.959 | 3 | 120.651 | 0 |

| 5 | -1 | 626.66 | 3 | 5.25 | 3.785 | -5.41 | 1408.78 | -0.737 | 3 | 77.824 | 0 |

| 6 | -2 | 789.74 | 3 | 5.25 | 5.292 | -7.58 | 1101.24 | -1.188 | 3 | 78.006 | 0 |

| 7 | -2 | 681.133 | 3 | 5.25 | 3.874 | -6.115 | 1045.43 | -1.049 | 3 | 76.927 | 0 |

| 8 | -1 | 696.615 | 3 | 5.25 | 4.296 | -6.362 | 1139.99 | -0.855 | 3 | 78.535 | 0 |

| 9 | -1 | 692.566 | 3 | 5.25 | 4.041 | -6.594 | 1165.82 | -0.93 | 3 | 79.063 | 0 |

| 10 | -2 | 649.456 | 3 | 6.75 | 3.026 | -5.716 | 550.078 | -1.32 | 3 | 103.133 | 0 |

| Standard | -2 | 342.372 | 5 | 3.5 | -0.778 | -2.971 | 184.592 | -1.022 | 2 | 102.134 | 0 |

CNS: Central Nervous System Penetration (values ≤-2 indicate low CNS penetration). SASA: Solvent Accessible Surface Area (in Ų), indicative of molecular surface interaction. Donor HB/Acceptor HB: Number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors. QPlog P o/w: Octanol-water partition coefficient, indicating lipophilicity. QP Caco: Permeability across Caco-2 cell monolayers (nm/s), reflecting intestinal absorption. QPlog HERG: Potential for interaction with the HERG channel (negative values indicate a lower risk of cardiotoxicity). PSA: Polar Surface Area (in Ų), affecting drug permeability. QPlog BB: Blood-brain barrier permeability (negative values indicate low permeability). Human Oral Absorption: Predicted oral absorption potential. Rule of Five: Compliance with Lipinski's Rule of Five.

The ADME analysis indicates that all compounds exhibit minimal CNS penetration, with values of-2 or lower, reducing the risk of CNS side effects. Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) values range from 789.74 to 626.66 Ų, suggesting favorable surface interactions and efficient absorption. Hydrogen bond donors range from 3 to 4.5, while acceptors vary between 5.25 and 6.75, ensuring optimal hydrogen bonding for target interactions. Lipophilicity (QPlog P) values range from 5.29 to 2.75, demonstrating a balanced absorption profile. Caco-2 permeability spans from 1408.78 to 158.38 nm/s, with higher values indicating enhanced intestinal absorption. Cardiotoxicity risk (QPlog HERG) remains low, ranging from-7.58 to-5.41, while negative QPlog BB values-1.95 to 0.73 suggest limited blood-brain barrier penetration. Most compounds adhere to Lipinski’s Rule of Five, supporting good oral bioavailability. Overall, these ADME profiles highlight the compounds as promising candidates for further development as safe and effective therapeutic agents.

Comparative analysis of compounds with standard drug

The comparative analysis of ten compounds against AMPK, using metformin as the benchmark, highlights their therapeutic potential. Docking studies reveal that compounds 2, 5, and 6 exhibit the highest binding affinities at-5.59,-5.23, and-5.22 kcal/mol, outperforming the standard drug-3.16 kcal/mol. MM-GBSA analysis further supports this, with compounds 5 and 7 showing the strongest binding free energies of-97.78 and-93.66 kcal/mol, compared to metformin-41.76 kcal/mol. Additionally, compounds 5 and 7 form the highest number of hydrogen bonds 5 with key AMPK residues, surpassing the standard drug, which forms 4 hydrogen bonds. ADME analysis confirms minimal CNS penetration, low cardiotoxicity risk, favorable oral absorption, and optimal lipophilicity for all compounds. Despite variations in hydrogen bonding and binding free energy, these compounds—particularly compound 5-demonstrate strong potential as effective AMPK activators, making them promising candidates for further development.

DISCUSSION

The molecular docking and ADME analyses highlight the potential of the studied compounds, particularly compound 5, 3-chlorophenyl-phenoxy acetamide, as promising therapeutic agents targeting AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a crucial regulator in diabetes management. These compounds exhibit strong binding affinities to AMPK, with docking scores of-5.22 kcal/mol, significantly outperforming the standard drug Metformin-3.16 kcal/mol [16]. Binding free energy calculations further reinforce their potential, with compound 5 showing a binding free energy of-97.78 kcal/mol, indicating robust and stable interactions with AMPK [17]. The extensive hydrogen bonding observed with key residues such as PRO 127, MET 84, ARG 117, and TYR 120 enhances binding efficiency, suggesting strong AMPK activation [18].

ADME profiling further confirms the favorable pharmacokinetic properties of all tested compounds, including minimal CNS penetration, good oral absorption potential, and low cardiotoxicity risk, making them safer alternatives compared to conventional synthetic drugs [19]. These properties, combined with their ability to target the AMPK pathway, suggest their potential as complementary agents in type 2 diabetes treatment, where maintaining intracellular glucose homeostasis is critical. To further validate these findings, future studies should focus on binding affinity assays such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), molecular dynamics simulations, and comprehensive in vitro and in vivo efficacy studies in diabetes models [20]. Additionally, detailed toxicity assessments and advanced ADME profiling will be essential to confirm the safety and efficacy of these compounds as therapeutic agents [21]. The integration of these novel compounds into diabetes treatment regimens holds significant potential for improving patient outcomes. When compared to established AMPK activators such as A-769662 and salicylate, which bind at the allosteric ADaM site, our phenoxy-acetamide derivatives engage with key catalytic site residues (e. g., ARG117, MET84, PRO127), suggesting a distinct binding mode. Additionally, compound 5 demonstrated stronger binding energies than reported values for A-769662 (ΔG_bind ~ –80 to –90 kcal/mol) [22], indicating potential for improved potency or selectivity. The phenoxy-acetamide scaffold introduced in this study represents a structurally novel approach to AMPK modulation, distinct from well-studied activators such as A-769662 and salicylate. While A-769662 binds at the ADaM site and is limited by off-target effects and low solubility, and salicylate demonstrates weak binding and poor specificity, our compounds target the AMPK catalytic site with enhanced affinity and favorable ADME profiles. Specifically, compound 5 demonstrates stronger binding energy (ΔG_bind = –97.78 kcal/mol) and improved pharmacokinetics compared to these traditional ligands. To validate these computational findings, we propose conducting AMPK phosphorylation assays in HepG2 hepatocyte cells, using compound 5 andrelated analogs. Phosphorylation of the AMPK α-subunit at Thr172, measured via Western blot, would serve as a key biomarker of activation. Enhanced glucose uptake or reduced gluconeogenesis in treated cells would further support the therapeutic relevance of these compounds [23]. In terms of lead optimization, future chemical modifications could include replacement of the nitro group (to reduce potential cytotoxicity) and introduction of polar moieties (e. g., hydroxyl or amide groups) to improve water solubility and bioavailability. Structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies will guide these modifications, with a focus on retaining high-affinity binding while improving drug-likeness and safety.

CONCLUSION

The molecular docking and ADME analyses strongly suggest that the studied compounds, particularly compound 5 (3-chlorophenyl-phenoxy acetamide), have significant potential as AMPK activators for diabetes treatment. These compounds exhibit higher binding affinities and greater stability within the AMPK catalytic pocket compared to the standard drug Metformin, indicating their strong activator potential. Key molecular interactions, including extensive hydrogen bonding with crucial AMPK residues PRO 127, MET 84, ARG 117, TYR 120, contribute to their enhanced binding efficiency. Additionally, their favorable ADME properties, such as good oral absorption, minimal CNS penetration, and low cardiotoxicity risk, support their potential as safe and effective therapeutic agents. Overall, these findings highlight the promise of these compounds in diabetes management. Further experimental validation through biophysical binding studies, molecular dynamics simulations, and in vitro/in vivo efficacy assessments will be essential to confirm their therapeutic viability. If successfully developed, these compounds could offer a new avenue for improving glucose regulation and diabetes treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Arulumigu Kalasalingam College of Pharmacy, Virudhunagar, Tamil Nadu, for providing facilities for conducting Research.

FUNDING

No funding was received for this work.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Koppula Jayanthi-Conceptualization, validation, original draft preparation, and data curation. Dr. Mohd Abdul Baqi-Data curation, and Dr. Narayana Venkateswaran Review and editing. S. Gobi Ananth, Indhumathi, and Sree Nithi-Data curation, methodology, and writing review.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(2):88-98. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.151, PMID 29219149.

Goldstein BJ. Insulin resistance as the core defect in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90(5A):3G-10G. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02553-5, PMID 12231073.

Sanches JM, Zhao LN, Salehi A, Wollheim CB, Kaldis P. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes and the impact of altered metabolic interorgan crosstalk. FEBS Journal. 2023 Feb;290(3):620-48. doi: 10.1111/febs.16306, PMID 34847289.

Solini A, Trico D. Clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of metformin in different patient populations: a narrative review of real-world evidence. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024 Aug;26 Suppl 3:20-30. doi: 10.1111/dom.15729, PMID 38939954.

Sadybekov AV, Katritch V. Computational approaches streamlining drug discovery. Nature. 2023;616(7958):673-85. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05905-z, PMID 37100941.

Hendawy OM. A comprehensive review of recent advances in the biological activities of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles. Arch Pharmazie. 2022 Jul;355(7):e2200045. doi: 10.1002/ardp.202200045, PMID 35445430.

Li Y, Peng J, Li P, Du H, Li Y, Liu X. Identification of potential AMPK activator by pharmacophore modeling molecular docking and QSAR study. Comp Biol Chem. 2019;79:165-76. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2019.02.007, PMID 30836318.

Baqi MA, Jayanthi K, Rajeshkumar R. Molecular docking insights into probiotics sakacin p and sakacin a as potential inhibitors of the cox-2 pathway for colon cancer therapy. Int J Appl Pharm. 2025;17(1):153-60. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2025v17i1.52476.

Sherman W, Beard HS, Farid R. Use of an induced fit receptor structure in virtual screening. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006 Jan;67(1):83-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2005.00327.x, PMID 16492153.

Badavath VN, Sinha BN, Jayaprakash V. Design in silico docking and predictive ADME properties of novel pyrazoline derivatives with selective human MAO inhibitory activity. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(12):277-82.

Imam SS, Imam ST, Mdwasifathar K, Kumar R, Ammar MY. Interaction between ace 2 and SARS-CoV-2, and use of EGCG and theaflavin to treat COVID 19 in initial phases. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2022;14(2):5-10. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2022v14i2.1945.

Jayanthi K, Ahmed SS, Baqi MA, Afzal Azam M. Molecular docking dynamics of selected benzylidene amino phenyl acetamides as TMK inhibitors using high throughput virtual screening (HTVS). Int J Appl Pharm. 2024;16(3):290-7. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i3.50023.

Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT. Glide: a new approach for rapid accurate docking and scoring. 1 method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem. 2004 Mar 1;47(7):1739-49. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430, PMID 15027865.

Divyashri G, Krishna Murthy TP, Sundareshan S, Kamath P, Murahari M, Saraswathy GR. In silico approach towards the identification of potential inhibitors from Curcuma amada Roxb against H. pylori: ADMET screening and molecular docking studies. Bioimpacts. 2021;11(2):119-27. doi: 10.34172/bi.2021.19, PMID 33842282.

Mulakala C, Viswanadhan VN. Could MM-GBSA be accurate enough for calculation of absolute protein/ligand binding free energies? J Mol Graph Model. 2013;46:41-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2013.09.005, PMID 24121518.

Abdalla M, Ogunlana AT, Akinboade MW, Muraina RO, Adeosun OA, Okpasuo OJ. Allosteric activation of AMPK ADaM’s site by structural analogs of epigallocatechin and galegine: computational molecular modeling investigation. In Silico Pharmacol. 2025 Jan 30;13(1):19. doi: 10.1007/s40203-025-00311-x, PMID 39896884.

Mofidifar S, Sohraby F, Bagheri M, Aryapour H. Repurposing existing drugs for new AMPK activators as a strategy to extend lifespan: a computer aided drug discovery study. Biogerontology. 2018;19(2):133-43. doi: 10.1007/s10522-018-9744-x, PMID 29335817.

Potunuru UR, Priya KV, Varsha MK, Mehta N, Chandel S, Manoj N. Amarogentin a secoiridoid glycoside activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) to exert beneficial vasculo metabolic effects. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2019;1863(8):1270-82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.05.008, PMID 31125678.

Alghamdi SS, Suliman RS, Aljammaz NA, Kahtani KM, Aljatli DA, Albadrani GM. Natural products as novel neuroprotective agents; computational predictions of the molecular targets ADME properties and safety profile. Plants (Basel). 2022;11(4):549. doi: 10.3390/plants11040549, PMID 35214883.

Joshi T, Singh AK, Haratipour P, Sah AN, Pandey AK, Naseri R. Targeting AMPK signaling pathway by natural products for treatment of diabetes mellitus and its complications. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(10):17212-31. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28528, PMID 30916407.

Zolnik BS, Sadrieh N. Regulatory perspective on the importance of ADME assessment of nanoscale material containing drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61(6):422-7. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.006, PMID 19389437.

Gu X, Bridges MD, Yan Y, De Waal PW, Zhou XE, Suino Powell KM. Conformational heterogeneity of the allosteric drug and metabolite (ADaM) site in AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). J Biol Chem. 2018;293(44):16994-7007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004101, PMID 30206123.

Rajan P, Natraj P, Ranaweera SS, Dayarathne LA, Lee YJ, Han CH. Anti-adipogenic effect of the flavonoids through the activation of AMPK in palmitate (PA)-treated HepG2 cells. J Vet Sci. 2022;23(1):e4. doi: 10.4142/jvs.21256, PMID 35088951.