Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 64-73Review Article

PECTIN BEADS IN DRUG DELIVERY: EXTRACTION, FORMULATION, AND PHARMACEUTICAL APPLICATIONS

SARAVANAN MUNIYANDY*

*Department of Pharmacy, Fatima College of Health Sciences, PO Box: 3798, AI, Mafraq, Abu Dhabi, The United Arab Emirates.

*Corresponding author: Saravanan Muniyandy; *Email: drmsaravanan@gmail.com

Received: 06 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 16 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Pectin is a natural, non-toxic biopolymer derived from plant cell walls, where it constitutes approximately one-third of the dry weight in most higher plants. Predominantly concentrated in the middle lamella, it has traditionally been used in the food industry for its thickening, gelling, and stabilizing properties. However, its unique resistance to gastric and intestinal enzymatic degradation, coupled with fermentability by colonic bacteria, has led to its emerging role in pharmaceutical applications, particularly in targeted drug delivery. The gelling characteristics of pectin depend on its source, molecular weight, and degree of esterification (DE), factors that influence its suitability as a carrier for bioactive agents. Despite the increasing interest in pectin-based systems, previous reviews have largely focused on its conventional uses, lacking depth in recent advancements within pharmaceutical and biomedical domains. This review addresses those lacunae by offering an updated and detailed examination of pectin's pharmaceutical relevance, with a special focus on pectin beads (PB). It outlines the complete process for preparing the PB formulation, including solution preparation, incorporation of active agents, cross-linking, droplet optimization, hardening, washing, and drying. Furthermore, the article examines the gelation and swelling properties of PB, as well as their morphological and physicochemical characterization using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and zeta potential analysis. Emphasis is placed on their versatile pharmaceutical applications, such as regulated drug release, colon-specific delivery, iron supplementation, immunization, and enhanced stability via polymeric coatings like chitosan and alginate. By synthesizing current findings, this review provides a comprehensive resource for researchers investigating the potential of pectin in modern therapeutic systems.

Keywords: Pectin beads (PB), Targeted drug delivery, Biopolymer, Controlled release, Colon-specific delivery, Pharmaceutical applications

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.54903 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

The majority of plant cell walls consist of pectin, a heterogeneous anionic polymer. Pectin is a natural biopolymer that has garnered considerable interest in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors. It is non-toxic and primarily broken down by bacteria in the colon without being affected by enzymes in the stomach or intestines [1]. It has traditionally served as a thickening, gelling, and stabilizing agent in the food and beverage industry, with its use now extending to various other sectors. Pectin's distinctive features have enabled its effective use as a medium for encapsulating and transporting various medications, proteins, and cells.

Pectin is a complex polysaccharide that constitutes about one-third of the dry weight of cell walls in most higher plants, although grass species contain much lower amounts. It is most concentrated in the middle lamella of the cell wall, with levels decreasing towards the primary wall and plasma membrane. The gelling properties of pectin are largely influenced by its molecular weight and DE, leading to source-dependent variations in gel formation [2]. Commercially, pectin is primarily obtained from citrus peels and apple pomace, which are by-products of juice and cider production. While apple pomace contains 10–15% pectin by dry weight, citrus peels have a higher pectin content, ranging from 20–30%. Other potential sources of pectin include sugar beet processing residues, sunflower heads remaining after oil extraction, and waste from mango processing.

Search strategy

To ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant literature, a structured search methodology was employed. The following electronic databases were systematically explored: PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Keywords used in the search included: "pectin beads," "drug delivery," "controlled release," "colon-targeted delivery," "biopolymer encapsulation," "calcium pectinate," and “mucoadhesive drug systems." Filters were applied to restrict the search to peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2000 and 2024. Articles were included based on their focus on pectin-based drug delivery systems, particularly those involving PB formulations, their physicochemical properties, or pharmaceutical applications. Exclusion criteria involved non-English publications, studies focused solely on food or industrial uses of pectin, and duplicate records. Reference lists of key articles were also screened to identify additional relevant studies.

Extraction of pectin

Pectin is typically extracted from raw plant materials using a hot, diluted mineral acid solution with a pH close to 2. The length of the extraction process depends on factors such as the type of raw material, the desired pectin characteristics, and the specific manufacturing techniques employed by each producer, which vary between them. During extraction, the hot pectin solution must be separated from the remaining solid matter, a process complicated by the soft texture of the material and the increased viscosity of the solution, which rises with both pectin concentration and molecular weight. To further purify the extract, filtration aids may be employed, followed by vacuum concentration. To produce powdered pectin, a concentrated extract-commonly derived from apples or citrus fruits, is mixed with alcohol, typically isopropanol, causing the pectin to precipitate out in a gel-like form. The gel is further crushed, rinsed to eliminate residual moisture, dried, and pulverized. The resultant pectin often possesses an esterification (or methoxylation) level of around 70%. The hydrolysis of this pectin by ammonia transforms certain ester groups into amide groups, yielding "amidated low methoxyl pectins."

Chemistry of pectin

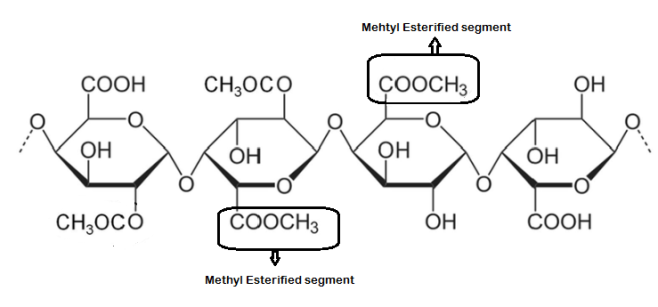

Calcium chloride (CaCl₂) is frequently utilized as a cross-linking agent to create macroscopic gels from low-methoxy pectins, in addition to pectin-based micro and nanoparticles, without requiring expensive apparatus or extreme processing temperatures [3]. Pectins are categorized into two primary types depending on their methyl-esterification degree (DM): high methyl-esterified (HM) pectins, which possess a DM exceeding 50%, and low methyl-esterified (LM) pectins, with a DM below 50% [4]. Pectin is a primarily linear polysaccharide found in plants, known for its diverse molecular structure and composition, which can vary depending on the plant source and extraction conditions. Typically, pectin chains consist of several hundred to nearly a thousand sugar residues, with molecular weights ranging from approximately 50,000 to 150,000 daltons. Variations in pectin composition can be observed between different samples and even within a single sample, influenced by the analytical methods used. It contains neutral sugars, such as rhamnose (Rha), which adds bends to the linear chain, while branched side chains include sugars like arabinose, galactose, and xylose [5]. The main structure generally consists of several hundred galacturonic acid (GalA) units linked by α-(1→4) bonds, with varying degrees of esterification. X-ray diffraction studies show that the galacturonan regions of sodium pectate adopt a helical structure, with three sugar units per turn and a repeating distance of 1.31 nm [6]. This helical form is consistent across sodium and calcium pectates, pectic acids, and pectinic acids, though the spatial arrangement of the helices may differ in the crystalline form. Pectin is classified based on its DE, which represents the proportion of esterified galacturonic acid (GalA) units relative to the total galacturonic acid (GalA). Its polygalacturonic acid backbone contains methyl-esterified segments, while ions like sodium, potassium, or ammonium may neutralize unesterified carboxyl groups. Pectin is commonly synthesized in a highly esterified state. It can undergo de-esterification in HM-pectins (High Methoxyl Pectin), which are soluble in hot water and are often used in conjunction with dispersing agents, such as dextrose, to prevent aggregation and form gels when sufficient soluble solids are present, and the pH is around 3.0. These gels exhibit thermal reversibility (fig. 1). Fig. 1 demonstrates the structural configuration of the polygalacturonic acid backbone in pectin, highlighting methyl-esterified galacturonic acid residues. These methyl groups influence the polymer’s ability to form three-dimensional networks through ionic interactions and hydrogen bonding, particularly with multivalent cations. The illustration clarifies the molecular segments responsible for cross-linking and gelation behavior.

Fig. 1: Polygalacturonic acid backbone with methyl-esterified segments of Pectin (Created by the author), chemical structures of representative sugar units in pectin. The rightmost unit contains a methyl-esterified galacturonic acid segment, indicated as the methyl-esterified segment

Characteristics of pectin

Pectinic and pectic acid salts with monovalent cations (e. g., alkali metals) are often water-soluble, but those with divalent or trivalent cations exhibit limited solubility or are insoluble [7]. Upon the addition of dry powdered pectin to water, it rapidly hydrates and aggregates into clumps. Clumping can be prevented by pre-mixing the pectin with a water-soluble carrier or utilizing pectin that has been specifically processed to enhance dispersibility [8]. The degree of ionization is regulated by the DE, influencing the number of negative charges in pectin, a linear polyanion (polycarboxylate) who’s negatively charged carboxylate groups electrostatically resist one another, hence inhibiting the aggregation of polymer chains [9]. Decreasing the pH diminishes the ionization of carboxylate groups, hence reducing their hydration and promoting the aggregation of polymer chains to create a gel. Pectins in solution are progressively degraded by desertification and depolymerization, with the rate of degradation affected by pH, water activity, and temperature, and have optimal stability at around pH 4.

Pectin beads (PB)

PBs are biopolymeric carriers extensively researched for pharmaceutical and medical applications due to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mucoadhesive characteristics. They are very efficacious in regulated medication delivery, safeguarding active ingredients from gastric degradation and enabling targeted release in the colon, which is advantageous for treating inflammatory bowel diseases (Sriyamornsak, 2003 [10].

PB has shown promise in enhancing the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs, making them a valuable tool in improving drug delivery systems. The ability of PB to control drug release rates also makes them suitable for sustained or prolonged drug delivery, ensuring a consistent therapeutic effect over an extended period. The versatility and effectiveness of PB make them a promising option for various pharmaceutical formulations and medical treatments.

Their capacity to encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic pharmaceuticals enhances solubility and bioavailability. Liu et al. (2007) [11]. PB are utilized in wound healing and tissue engineering due to their gelling properties and moisture retention, which facilitate cellular proliferation. These adaptable technologies enable the provision of enduring, patient-focused therapy solutions. However, PB may not be suitable for all types of pharmaceutical formulations, as they may not provide the necessary sustained release or targeted delivery required for certain drugs. The gelling properties of pectin may hinder drug release in some cases, limiting its effectiveness in certain applications [12].

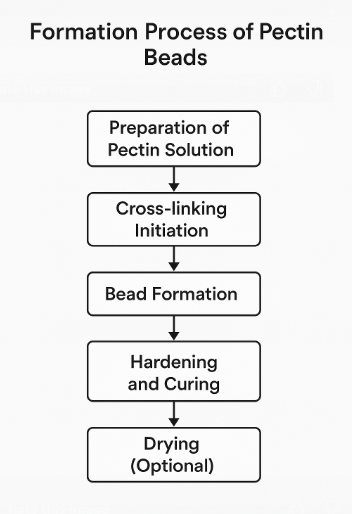

Stages of PB formation

Preparation of pectin solution

Pectin, a natural polysaccharide derived from plant cell walls, is dissolved in distilled water or buffer to form a viscous aqueous solution. The concentration of pectin typically ranges from 1% to 5% w/v, depending on the desired bead firmness and drug loading capacity. The solution may also include therapeutic agents such as anti-inflammatory drugs, proteins, or probiotics-which are uniformly dispersed under constant stirring. The pH and temperature of the solution are carefully controlled to maintain the solubility and integrity of both pectin and the encapsulated substances.

Incorporation of active agents

Hydrophilic or hydrophobic drugs can be incorporated at this stage. Hydrophobic drugs may require emulsification using surfactants or cosolvents to ensure uniform distribution within the pectin matrix. For bioactive compounds sensitive to heat or pH, gentle mixing and ambient temperature conditions are used to preserve activity.

Cross-linking and bead formation

The prepared pectin solution is extruded dropwise into a gently stirred solution of CaCl₂, typically at a concentration of 1–3% w/v. The calcium ions induce ionic cross-linking of pectin chains by binding to the carboxyl groups present in the galacturonic acid residues, leading to the rapid formation of a gel network. Upon contact, each droplet instantaneously gels into a spherical or near-spherical bead.

Optimization of droplet formation

The bead size and morphology are influenced by several factors, including the droplet generation technique, which can be achieved using a syringe, nozzle, or peristaltic pump. Height of droplet fall: affects sphericity and impact force. The viscosity of the pectin solution: Higher viscosity leads to larger bead diameters. Stirring speed of the CaCl₂ bath: ensures uniform shape and prevents aggregation.

Hardening and curing

After initial gelation, the beads are left in the CaCl₂solution for a defined period (usually 15–60 min) to complete cross-linking. This curing stage ensures the mechanical stability and integrity of the beads for handling or further processing.

Washing

The beads are then filtered and thoroughly washed with deionized water to remove excess calcium ions and surface-adhered, unencapsulated drugs or polymers. This process ensures that the beads are clean and free of any contaminants that could affect the final product. Once the washing is complete, the beads are dried and then subjected to further processing or analysis. The cleanliness of the beads is crucial to ensure the effectiveness and quality of the final encapsulated product. This rigorous cleaning process is essential to guarantee the purity and safety of the encapsulated drug or polymer. Any remaining contaminants could alter the properties or performance of the final product, potentially leading to health risks or decreased efficacy. By extensive washing and drying of the beads, manufacturers can confidently proceed with the encapsulation process, ensuring the result meets the necessary standards and specifications. Clean beads also help to prevent any unwanted reactions or interactions that could occur during storage or use of the final product.

Drying

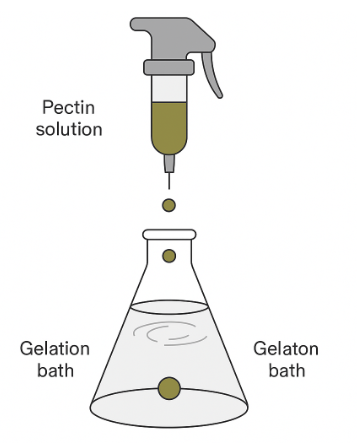

Wet PB may be used directly for colon-targeted delivery or as a tissue scaffold. Drying (via air-drying, oven-drying, or lyophilization) can enhance shelf life and modify release characteristics. For example, freeze-drying produces porous beads ideal for rapid drug rehydration or delivery. These porous beads can also be easily coated to control drug release rates further. Freeze drying can help maintain the stability of sensitive drugs that may degrade in the presence of moisture [13]. Overall, the drying process plays a crucial role in optimizing the performance and effectiveness of wet polymeric biomaterials (PB) for various applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering. While drying can enhance shelf-life and modify release characteristics, it may also lead to changes in the physical and chemical properties of the drug, potentially affecting its efficacy or stability. Additionally, the freeze-drying process can be time-consuming and costly, making it less feasible for large-scale production (fig. 2). Fig. 2 outlines the stepwise process in pectin bead formation, including solution preparation, drug incorporation, ionic cross-linking, and drying. The fig. illustrates how calcium ions interact with carboxyl groups of galacturonic acid units to create a cohesive hydrogel network—referred to as ionotropic gelation—leading to spherical bead formation with desired mechanical properties.

|

|

Fig. 2: Formation of PB (Created by the author)

Gelation properties of PB

Pectin's primary role is to form gels, particularly when combined with sugar and acid. This gelling action results from the partial removal of water from the pectin structure, positioning it between a completely dissolved and a precipitated state due to its unique molecular arrangement. Pectin functions within specific constraints. High methoxyl (HM) pectin, unlike low methoxyl (LM) pectin, has fewer free acid groups, which prevents it from forming gels or precipitating in the presence of calcium ions [14]. However, under certain conditions, HM pectin can precipitate in the presence of specific metal ions such as copper or aluminum. The aggregation of pectin is mainly influenced by hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions [15]. Gel formation occurs when hydrogen bonds are established between the free carboxyl groups and the hydroxyl groups of adjacent pectin chains. In neutral to slightly acidic environments, most of the unesterified carboxyl groups in pectin exist as partially ionized salts. The ionized groups impart a negative charge to the molecule, attracting layers of water. Upon the addition of acid, carboxylate ions mostly transform into un-ionized carboxylic acid. This shift diminishes the affinity of pectin for water molecules and the repulsive forces among pectin strands. The incorporation of sugar diminishes pectin hydration by competing for water, hence decreasing the molecule's dispersibility. Unlike HM-pectin, LM-pectins (Low Methoxyl Pectin) require divalent cations, often calcium, for effective gelation. The commonly accepted 'egg-box' model is often used to describe this process [16]. However, Racape and colleagues found that this model alone could not fully account for the gelation of amidated pectins. They suggested that the amide groups in the pectin chain contribute to gel formation by promoting stronger hydrogen bonding. In the pharmaceutical industry, pectin is valued for its positive impact on blood cholesterol levels. The various cross-linking agents used in pectin gel production offer the advantage of modifiable material properties, including mechanical strength, degradation rate, and biological reactions. The modifiable characteristics of pectin gels make them suitable for several biological applications. Pectin gels cross-linked with Ca²⁺ exhibit greater flexibility compared to those cross-linked with Zn²⁺. The classical “egg-box” model describes ionic gelation of low-methoxyl pectin through the coordination of calcium ions with carboxyl groups on adjacent galacturonic acid chains. However, Racape et al. demonstrated that this model alone is insufficient to explain the gelation behavior of amidated pectin. In amidated pectin, some carboxyl groups are replaced with amide groups (–CONH₂), which cannot form ionic bonds with calcium. Instead, these amide groups participate in hydrogen bonding, contributing additional intermolecular interactions that stabilize the gel matrix. Thus, in amidated pectin, both ionic (Ca²⁺-carboxyl) and hydrogen bonding (via amide groups) mechanisms operate synergistically to form and reinforce the gel structure. While calcium is the most widely used cross-linking ion due to its safety and simplicity, zinc offers distinct advantages in pharmaceutical applications. Zinc-crosslinked pectin beads form stronger gels with reduced swelling in acidic conditions, providing better protection for encapsulated drugs and enabling sustained release. This increased gel strength results from zinc’s higher affinity for pectin and tighter cross-linking. In contrast, calcium-crosslinked beads offer greater flexibility and are more commonly accepted for clinical use. Therefore, the choice between zinc and calcium should be based on the drug’s stability, desired release profile, and target site within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Swelling properties of PB

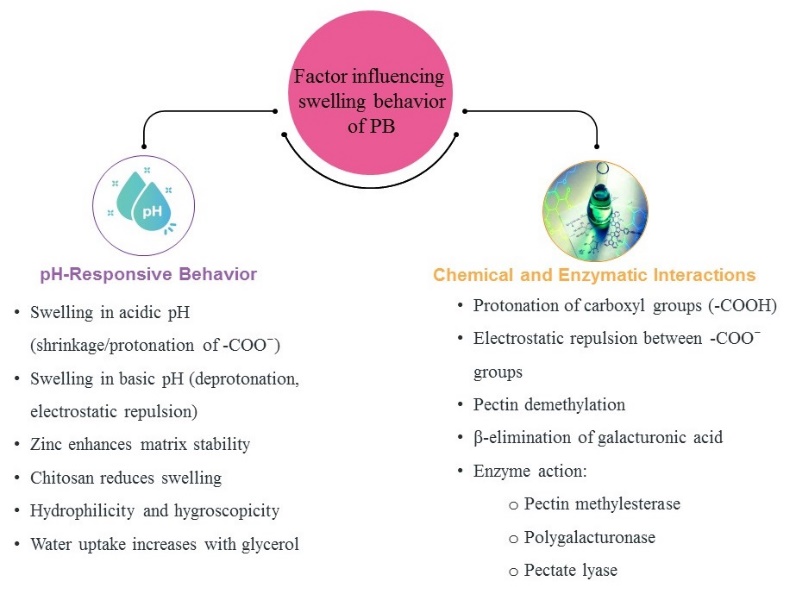

The swelling behavior of pectin beads (PB) is governed by a combination of pH-responsive characteristics and chemical/enzymatic interactions, as summarized in fig. 3. In acidic environments, the protonation of carboxylic groups (–COOH) leads to shrinkage due to reduced electrostatic repulsion, whereas in alkaline pH, deprotonation results in increased ionization and swelling via electrostatic repulsion between –COO⁻ groups. Furthermore, zinc ions enhance matrix stability, while chitosan coatings are known to suppress swelling due to strong ionic interactions. Hydrophilicity and hygroscopicity of the matrix are increased in the presence of glycerol, contributing to higher water uptake. Fig. 3 clearly illustrates how these pH-responsive factors, in conjunction with enzymatic actions (e. g., pectin methyl esterase, polygalacturonase, and pectate lyase), work synergistically to regulate PB swelling under GI conditions.

The integration of zinc as a counter-ion resulted in PB demonstrating greater durability in the upper GI tract compared to those formed with calcium [17]. This results from zinc's greater binding ability and heightened affinity for pectin, along with the augmented gel strength of zinc pectinate. These characteristics led to less swelling in the dissolving medium, hence facilitating a prolonged drug release. Nevertheless, enteric capsules were crucial to protect the pectin matrix from chemical degradation caused by acidic and basic environments at pH 1.2 and 7.4. The degree of swelling markedly affects the drug-release properties of delivery devices. The swelling behavior of iron-PB was found to be dependent on the pH, with a decrease in swelling observed in the acidic gastric environment (pH 1.25). In line with prior research, the swelling of PB was greater in a simulated intestinal setting (pH 8) compared to the acidic condition [18]. This variation in swelling is attributed to the electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged carboxyl groups (-COO-) of pectin, which is an anionic polyelectrolyte. The conformation of these molecules is affected by the pH of their surroundings. Acidic conditions lead to the protonation of carboxyl groups, reducing electrostatic repulsion owing to the presence of H⁺ ions. Consequently, the polymer chains become more compact, reducing water infiltration and polymer solubility. At elevated pH values, carboxyl groups stay ionized, enhancing hydrophilicity and promoting polymer network expansion via electrostatic repulsion, hence increasing water absorption. At pH 8, the polymer exhibits enhanced swelling capacity. Hydroxyl ions play a role in this process by promoting the release of Fe(II), which acts as a cross-linking agent between pectin strands, thus increasing water absorption [19]. The chemical makeup of the iron-PB and commercial citrus pectin was examined through X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis. The findings indicated a significant rise in iron concentration following encapsulation. The inherent cations of commercial pectin, including K⁺ and Cu²⁺, diminish during gelation, signifying the replacement of Fe²⁺. The iron was entirely encapsulated within the beads, but the sulfate ions from the iron salt were partially preserved.

The pH-responsive swelling behavior of pectin beads plays a crucial role in protecting drugs during GI transit. In acidic gastric environments (pH 1.2), reduced swelling limits water penetration and drug diffusion, effectively shielding acid-sensitive compounds from degradation. This characteristic is particularly beneficial for delivering unstable drugs, such as proteins, peptides, or azathioprine, ensuring their integrity until they reach the intestine or colon. At higher pH values, the ionization of carboxyl groups enhances bead hydration and swelling, allowing for controlled and site-specific drug release. This dual mechanism supports targeted delivery and improves the bioavailability of therapeutic agents.

The increased swelling of PCaC beads in an acidic environment results from the protonation of amine groups, leading to the production of cationic NH₃⁺groups [20]. This generates electrostatic repulsion among polymer chains, resulting in a more elongated and hydrated conformation. PB demonstrated enhanced swelling relative to the chitosan-coated counterparts. The investigation of chitosan-coated PB revealed that the pectin carboxyl groups did not undergo protonation after coating, which contrasts with the findings from FTIR analysis in this study [21]. In cases of rapid and significant bead swelling, the release of Cwp84 in the simulated intestinal medium (SIM) is minimal, around 5%. This result highlights the effectiveness of zinc-pectinate beads in controlling protein release in the simulated intestinal media, even in the absence of pancreatic [22]. When the beads were transferred to a simulated colonic medium (SCM) containing pectinolytic enzymes, approximately 80% of the encapsulated protein was released after 2 h, and 90-95% was released after 5 h [23].

SCM was prepared to mimic the enzymatic and pH conditions of the human colon. The medium consisted of 50 mmol sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.8), containing 1 mg/ml pectinase (from Aspergillus niger) and 0.5 mg/ml polygalacturonase. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C to assess enzymatic activity. The enzymatic profile was selected to simulate the microbial degradation of pectin in the colon, specifically the cleavage of galacturonic acid chains through hydrolysis and β-elimination [24]. For studies evaluating pectin bead degradation, PB was immersed in SCM for up to 6 h and analyzed for swelling, size, and drug release behavior. This substantial release is attributed to the enzymatic breakdown of the bead matrix. The pectinolytic enzymes involved are pectin methylesterase, which removes methoxy groups from pectin, and two forms of pectin depolymerase. Polygalacturonase, a hydrolase, cleaves glycosidic bonds next to free carboxyl groups in the galacturonan chain, while pectate lyases break these bonds by β-elimination, generating a double bond between the C4 and C5 carbon atoms of the monomer [25].

Glycerol significantly increased the water absorption ability of pectin gels, supporting their known hydrophilic and hygroscopic properties. The incorporation of glycerol resulted in films exhibiting greater water absorption compared to those without it. Consistent with earlier studies, both pectin-glycerol gel beads and calcium-cross-linked pectin gel beads, created through the ionotropic gelation technique, demonstrated swelling when exposed to gastric fluid while retaining most of their structural integrity [26]. However, hydrogel beads composed of commercial pectins (such as citrus or apple) and cross-linked with calcium ions did not traverse the upper GI tract after 4-6 h. The beads developed under stomach settings did not rapidly dissolve their polymer matrix. Still, they swiftly disintegrated upon transitioning from the acidic environment of simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2) to the neutral pH of simulated intestinal fluid (pH 6.8). Sucrose, frequently utilized in the production of HM pectin gels, may be replaced by glucose, fructose, or polyols such as ethylene glycol or glycerin. The swelling properties of pectin-based hydrogel beads, both with and without a chitosan coating, were evaluated using simulated digestive fluids prepared under simulated gastric conditions. The beads exhibited expected shrinkage, mostly attributed to the protonation of dissociated carboxylic groups in the galacturonic acid backbone [27]. The protonation reduces electrostatic repulsion, leading to particle contraction. Some carboxylic groups strengthen the gel network, whereas others when released and dissociated, can promote the degradation of PB in acidic environments for both high and low-methyl-esterified pectins. Upon exposure to simulated intestinal fluid (pH 7), both coated and untreated hydrogel beads initiated disintegration. Although the particle size remained unchanged after 60 min, shrinkage and degradation were apparent by 120 min, resulting in complete disintegration upon reintroduction of the beads into the intestinal medium following size analysis. Similar behavior has been observed with chitosan-coated alginate hydrogel beads, characterized by a rapid release of the encapsulated substance during the intestinal phase.

Wong et al. demonstrated that alginate-chitosan beads exhibited significant swelling (86%) and high water absorption (593%), which facilitated thymoquinone release through diffusion-driven mechanisms described by the Korsmeyer–Peppas model. [28] This behavior is particularly relevant to pectin-based systems, as PBs also rely on matrix swelling and degradation for controlled release, especially under colonic conditions. The release of thymoquinone was primarily enabled via diffusion through the expanding matrix, as clarified by the Korsmeyer–Peppas model. Fructose or polyols, such as ethylene glycol or glycerol, were involved (fig. 3). These findings support the hypothesis that modifying PBs with chitosan or alginate could similarly enhance drug release profiles.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of PB

The influence of pectin’s Degree of Methylation (DM) on the morphology of the gels was observable exclusively through SEM analysis. SEM imaging of the dehydrated glycerol gel beads revealed a surface characterized by protrusions and depressions [29]. As glycerol content increased, the surface defects of the gel beads decreased. These anomalies may indicate an uneven distribution of glycerol across the gel matrix. The formation of surface cracks was probably a result of the swift drying process that occurred when the pectin solution was introduced into a 50% glycerol-ethanol mixture and subsequently washed with ethanol. The presence of surface imperfections on the dried glycerol gel beads signifies that the glycerol distribution was heterogeneous inside the gel matrix [30]. The decrease in surface defects with higher glycerol concentration may indicate a more homogeneous distribution of glycerol within the gel. The appearance of surface cracks is likely due to the accelerated drying process, which may have caused stress on the gel beads [31]. Future studies may investigate various drying methodologies to minimize surface cracking and enhance the overall morphology of the gel beads. SEM images of calcium pectinate beads revealed surface cracks in all tested pectin concentrations. The fissures varied in size from 2 to 11 µm. The analysis of pore radius, pore volume, and adsorption isotherms indicated that the beads were essentially nonporous. The differences in isotherm profiles at different pectin concentrations were attributed to the existence and size of surface cracks, with greater variances associated with bigger fractures. The surface area analysis confirmed that the beads were inside the micro particle range.

The beads formed matrix structures that may contain active chemicals on their surface and within their core. The size, shape, and stability of the beads were mostly influenced by the concentrations of pectin and the gelation medium. Generally, increased levels of polymer and gelation bath led to reduced bead diameters; nevertheless, both low and high pectin concentrations produced beads that were flattened or irregularly shaped. Beads consisting of 6% pectin and 2% CaCl₂ had a spherical morphology and smooth surfaces [32]. Augmented surface cross-linking in calcium pectinate beads improved encapsulation effectiveness and decreased the release rate of active chemicals. The beads exhibited a smooth, spherical shape without any visible pores, but some surface wrinkles were observed. Confocal microscopy revealed fluorescence of chitosan around the bead, confirming that this polysaccharide served as a coating on the pectin particle. The utilization of chitosan as a coating on PB suggests potential applications in drug delivery or food encapsulation, capitalizing on the advantageous biodegradable and biocompatible characteristics of both substances. Future studies may investigate the release kinetics of encapsulated medicines from these coated beads and the viability of targeted distribution within specific biological systems. The characterization of these chitosan-coated PB offers significant prospects for use in several sectors.

Particle size and zeta potential of PB

The iron-PB's size and surface charge (zeta potential) were evaluated using dynamic light scattering (DLS) [33]. The beads exhibited nearly neutral surface charges in both mediums, with zeta potential values recorded at 1.1±0.7 mV in distilled water and 1.2±0.9 mV after undergoing simulated GI digestion. The focus was mainly on the particle size post-digestion, as the GI tract is the target site. After digestion, the smallest particle fraction showed a Z-average diameter of 4.6±1.2 µm and a polydispersity index (PDI) of 5.3±1.4 [34]. These results suggest that digestive conditions significantly compromised bead integrity, reducing their size from an initial range of 1–2 mm. The high PDI indicates a diverse particle size distribution, likely due to structural degradation during the digestion process. The beads, prepared through ionotropic gelation in acidic media, exhibit maximum pectin gel stability at pH 4.

The digestive conditions significantly compromised bead integrity, reducing their size from an initial range of 1–2 mm. A high PDI reflects substantial heterogeneity in particle size, which can negatively impact drug delivery performance. Such variability may result in inconsistent drug release profiles, which can affect therapeutic efficacy and patient compliance. Moreover, high PDI poses challenges in achieving reproducibility and scalability during manufacturing, complicating quality control and regulatory compliance. Therefore, controlling PDI is crucial for ensuring uniform drug release, stability, and industrial feasibility of PB-based formulations. In pharmaceutical development, a low PDI (typically<0.3) indicates a narrow size distribution, contributing to predictable pharmacokinetics and better control over the release rate of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). Uniform particles are more likely to exhibit consistent swelling, erosion, and degradation patterns, which are essential for sustained or targeted delivery systems. Uniformity in particle size enhances flow properties and packing during processing, facilitating efficient encapsulation, coating, and downstream handling. Regulatory agencies also emphasize particle uniformity as a key quality attribute. Hence, maintaining an optimal PDI is a critical parameter in the design and large-scale production of robust, reliable, and patient-friendly drug delivery systems.

The enlargement of pores observed in simulated gastric fluid is likely due to bead swelling. In contrast, under alkaline conditions, pectin undergoes β-elimination of galacturonic acid residues, resulting in polymer chain scission, reduced viscosity, and diminished gel stability [35]. Pectin demethylation can occur under such conditions. The simulated intestinal phase was identified as the primary factor contributing to bead disintegration and size reduction in this study. For targeted colon delivery of β-lactamases, calcium-pectinate beads were formulated using low-methoxyl pectin via the ionotropic gelation technique [36]. An increase in CaCl₂ concentration in the gelation medium often resulted in larger bead sizes, attributed to enhanced calcium retention inside the beads. The enlargement was ascribed to improved water retention due to the hygroscopic characteristics of CaCl₂.

Even after removing free calcium from the beads, the average particle size showed no significant variation across various CaCl₂ concentrations. Extending the duration of immersion in CaCl₂ solution at a fixed concentration did not significantly affect bead diameter since calcium saturation was attained during the first hour. Under these conditions, with stable calcium and water concentrations, the size of the beads remained constant. The swift gelation of pectin facilitated the effective entrapment of β-lactamases inside the calcium pectinate beads. The concentration of pectin significantly influenced bead size, with higher pectin concentrations leading to smaller microspheres. As polymer content rises, the viscosity of the solution increases significantly. The increased viscosity reduces surface tension, resulting in the formation of smaller PB [37]. Elevated pectin concentrations may lead to reduced microsphere dimensions due to increased viscosity.

Variables such as stirring velocity and droplet size may also considerably affect bead size. The relationship between polymer content and bead size may be nonlinear and may vary depending on the specific solution parameters. Increasing the stirring velocity may enhance turbulence in the solution, leading to the formation of bigger beads despite a higher polymer concentration. The initial dimensions of the droplets dispersed in the fluid may also affect the ultimate size of the microspheres. Therefore, while developing a technique for microsphere manufacturing, it is essential to consider all these factors and adjust the parameters to get the desired bead size. The average diameter of the hydrogel beads ranged from 3.0±0.1 mm to 4.5±0.1 mm, with pectin content significantly influencing this parameter. The pectin concentration determines the solution's viscosity, which is essential during processing. In simple dripping, drop formation at the needle tip is primarily governed by gravitational force and surface tension, with viscosity having a minimal impact within the range of 10 to 100 mPa·s. The final dimensions of hydrogel beads depend on the initial droplet size and the modifications that occur during crosslinking, with the latter being the principal factor influencing bead size variability. Electrostatic dripping during ionic gelation can significantly reduce particle size when required. This method also has the benefit of producing beads with uniform size distribution and improved sphericity. When an electric current is applied, charged molecules move toward the droplet surface, therefore reducing surface tension due to the repulsion between similar charges. As a result, electrostatic pressure shapes the droplet into a conical configuration, ultimately resulting in the expulsion of smaller droplets from the apex of the solution (table 1 and 1A).

Table 1: Controlled release formulation of PB

| Author(s) | Formulation | Title of the research | Feature of the formulation |

| Atara, S. A., and Soniwala, M. [38] | Pectin–CaCl₂ Beads | Formulation and Evaluation of Pectin-CaCl₂ Beads of Azathioprine for Colon-Targeted Drug Delivery System | Eudragit S100 coating for colon-specific sustained release |

| Kamble, D., et al. [39]. | Pectin-HPMC Coated Floating Beads | Investigation of Pectin-HPMC-Coated Floating Beads for Pulsatile Release of Piroxicam | Floating mechanism for stomach-targeted pulsatile delivery |

| Rebitski, E. P., et al. [40] | Chitosan–Pectin Core–Shell Beads | Encapsulating Metformin–Clay Intercalation Compounds | Mucoadhesive bio-nanocomposite for extended delivery |

| Ramteke, K. H., and Nath, L [41]. | Pectin–Bora Rice Beads | Formulation and Evaluation of Pectin-Bora Rice Beads | Natural polymer blend for colon targeting |

| Skowron, K., et al. [42] | Bipolymeric Pectin Millibeads | Controlled and Targeted Release of Mesalazine | Functional polymers for colon-targeted delivery |

| Aydin and Akbuga, 1996 [43] | LM-Pectin Gel Beads | PB prepared by ionotropic gelation | Simple gelation method using Ca²⁺ ions |

| Sriamornsak and Nunthanid, 1998, 1999 [44] | LM-Pectin (Amidated) Gel Beads | Sustained release drug delivery using calcium pectinate gel beads | Sustained release behavior in vitro |

| Munjeri et al., 1998; Musabayane et al., 2000 [45, 46] | LM-Pectin (Amidated) Gel Beads | In vitro and in vivo studies of pectin hydrogel beads | Oral delivery with animal pharmacokinetic data |

| Pillay et al., 2002 [47] | LM-Pectin Gel Beads | Cross-linked alginate–pectinate–cellulose acetate spheres | Multi-polymer network for improved drug entrapment |

| Munjeri et al., 1997 [48] | LM-Pectin (Amidated) Gel Beads | Chitosan-polyelectrolyte complex around calcium pectinate beads | Improved stability and modified release |

| Sriamornsak, 1998, 1999 [49, 50] | LM-Pectin (Amidated) Gel Beads | Calcium pectinate gel beads for protein delivery | Protein encapsulation and protection |

Pharmaceutical applications of PB

Oral drug delivery

Pectin gels provide significant advantages for oral drug delivery systems due to their inherent pH responsiveness, mucoadhesive properties, and high swelling capacity. These characteristics make them especially effective for protecting and delivering sensitive pharmaceutical compounds through the harsh environments of the GI tract. One of the critical benefits of pectin-based systems is their ability to swell in response to the pH variations along the GI tract. Specifically, enhancing the swelling of pectin gels in the acidic environment of the stomach can prolong gastric residence time, which not only aids in delayed and sustained drug release but may also contribute to appetite control by enhancing the feeling of satiety. The swelling mechanism is largely governed by the hydrophilic carboxylic acid (COOH) groups present on the galacturonic acid backbone of pectin [51]. These groups attract and retain water, leading to matrix expansion. The extent of swelling can be further modulated by cross-linking the polymer chains with divalent or trivalent cations (e. g., Ca²⁺ or Al³⁺), which reinforces the gel network, enhancing mechanical stability and resistance to premature degradation. This cross-linking not only improves the robustness of the beads under gastric conditions but also facilitates controlled and site-specific drug release, ensuring consistent therapeutic efficacy over time. Beads were spherical, with diameters of 4–5 mm before drying. Upon drying, their moisture content decreased from 90% to around 7–15%, resulting in a significant reduction in bead size.

Orally administered drugs frequently encounter multiple barriers, such as degradation by gastric acid, enzymatic hydrolysis by proteases, and microbial fermentation in the colon. Pectin beads (PBs) serve as protective carriers, encapsulating APIs within their gel matrix to prevent premature breakdown and ensure the targeted delivery of bioactive compounds to specific sites, such as the intestine or colon. In recent developments, composite hydrogels comprising pectin and other biopolymers, such as gellan gum (GG), have been engineered to optimize drug delivery properties [52]. These GG: P (Gellan Gum: Pectin) formulations form mucoadhesive microcapsules through ionic cross-linking with Ca²⁺ or Al³⁺, which significantly enhances their retention at mucosal sites and regulates drug diffusion rates. For example, GG: P beads have demonstrated the ability to slow the release of ketoprofen under acidic pH (simulated gastric conditions) while extending its release under neutral to basic conditions (pH 7.4), mimicking intestinal environments.

Furthermore, these beads have shown excellent biocompatibility in Caco-2 and HT29-MTX cell line models, indicating their safety and suitability for oral administration. Beyond pharmaceuticals, PBs are increasingly being explored for nutraceutical and cosmeceutical applications, including the encapsulation of natural or synthetic fragrances. Due to the high volatility of these aromatic compounds, they are often unstable in open systems. PBs help stabilize such ingredients by entrapping them within a hydrogel matrix, thereby extending their shelf life, controlling their release, and enhancing their sensory effect upon oral consumption or topical application [53]. Overall, the multifunctional nature of pectin-based gels and beads—encompassing their physicochemical tunability and ability to protect and sustain the release of encapsulated compounds-positions them as a versatile and promising platform in advanced drug delivery systems.

Table 1A: Key studies on pectin bead formulations, encapsulated drugs, target sites, and outcomes

| Author(s) | Title of the research | Drug encapsulated | Targeted site | Critical results/findings |

| Atara, S. A., and Soniwala, M. [38] | Formulation and Evaluation of Pectin-CaCl₂ Beads of Azathioprine for Colon-Targeted Drug Delivery System | Azathioprine | Colon | Optimized formulation showed 86.24% drug entrapment and pH-dependent release, favouring colonic delivery. |

| Kamble, D., et al. [39]. | Investigation of Pectin-HPMC-Coated Floating Beads for Pulsatile Release of Piroxicam | Piroxicam | Stomach | Beads exhibited lag time of 6 h with maximum release after lag period, confirming pulsatile pattern. |

| Rebitski, E. P., et al. [40] | Encapsulating Metformin–Clay Intercalation Compounds | Metformin | Intestine | Enhanced mucoadhesion and sustained release over 12 h with improved bioavailability. |

| Ramteke, K. H., and Nath, L [41]. | Formulation and Evaluation of Pectin-Bora Rice Beads | Glipizide | Colon | Achieved 84.29% drug entrapment and controlled release at pH 6.8 with delayed onset. |

| Skowron, K., et al. [42] | Controlled and Targeted Release of Mesalazine | Mesalazine | Colon | Provided pH-dependent release with minimal drug loss in gastric conditions |

| Aydin and Akbuga, 1996 [43] | PB prepared by ionotropic gelation | Salbutamol sulfate | GI tract | Demonstrated high encapsulation efficiency and sustained release profile in simulated GI fluids. |

| Sriamornsak and Nunthanid, 1998, 1999 [44] | Sustained release drug delivery using calcium pectinate gel beads | BSA (model protein) | Colon | Achieved over 70% release in colonic conditions after 6 h; minimal degradation in gastric pH. |

| Munjeri et al., 1998; Musabayane et al., 2000 [45, 46] | In vitro and in vivo studies of pectin hydrogel beads | Chloroquine, Insulin | GI tract | In vivo data confirmed effective delivery with pharmacological activity and protection from degradation. |

| Pillay et al., 2002 [47] | Cross-linked alginate–pectinate–cellulose acetate spheres | Theophylline (model) | Colon | Achieved extended release over 24 h with reduced burst effect and good matrix stability. |

| Munjeri et al., 1997 [48] | Chitosan-polyelectrolyte complex around calcium pectinate beads | Indomethacin, Sulphamethoxazole | Colon | Improved resistance to enzymatic degradation and pH-controlled release beyond small intestine. |

| Sriamornsak, 1998, 1999 [49, 50] | Calcium pectinate gel beads for protein delivery | Proteins | Colon | Efficient protein loading with controlled release and protection in acidic medium. |

Nasal drug delivery

Iron in fortified foods can cause ionic gelation, a phenomenon where interactions with divalent cations lead to the formation of polymeric beads. This process involves cations binding to carbohydrate chains, resulting in the creation of stable cross-linked networks that are insoluble in aqueous media [54].

Intranasal drug delivery offers a non-invasive and patient-friendly alternative to parenteral routes, making it especially suitable for the treatment of localized conditions such as nasal allergies, sinus infections, congestion, and inflammation. Beyond local effects, the nasal route also enables systemic drug delivery due to the rich vascularization of the nasal mucosa, which facilitates rapid absorption and a more rapid onset of action. However, a significant limitation of this route is the short residence time of drugs in the nasal cavity due to mucociliary clearance. To overcome this, mucoadhesive polymers, such as pectin, have gained considerable attention for their ability to prolong drug retention and enhance bioavailability. Pectin, a natural anionic polysaccharide, exhibits excellent mucoadhesive properties owing to its capacity to form non-covalent interactions—such as hydrogen bonding and electrostatic attraction—with mucin, the principal glycoprotein in mucus. These interactions result in increased viscosity of the formulation and stronger adhesion to the mucus layer, thus reducing drug clearance and enhancing absorption. The effectiveness of pectin-based systems in nasal drug delivery has been demonstrated using various chemically modified pectins, including low-esterified (P-25), high-esterified (P-93), and amine-functionalized (P-N) variants. These forms differ in surface charge and interact with the mucosal environment in distinct ways, offering versatility in tailoring the formulation to the desired pharmacokinetic profile. Moreover, pectin-based nasal formulations have been found not only to improve the bioavailability of conventional drugs but also to enable the delivery of sensitive biomolecules, such as peptides, proteins, and vaccines. The ability of pectin to create a sustained release matrix within the nasal cavity makes it a promising excipient for future innovations in both local and systemic nasal therapies. Overall, pectin-based intranasal delivery systems represent a promising platform that combines biocompatibility, mucoadhesion, and functional adaptability to enhance therapeutic efficacy and patient compliance.

Colonic drug delivery

The colon, characterized by relatively low protease activity, neutral pH, and prolonged transit time, presents favorable conditions for targeted drug delivery, especially for macromolecules like proteins and peptides that are otherwise prone to degradation in the upper GI tract. Pectin, a plant-derived polysaccharide, is particularly suited for such delivery systems due to its resistance to enzymatic digestion in the stomach and small intestine. It remains stable in these harsh environments but is selectively degraded in the colon by bacterial enzymes—specifically pectinolytic enzymes such as pectin lyases, pectate lyases, and polygalacturonases—produced by the gut microbiota. One widely used approach to leverage this property involves the formation of calcium-pectinate (Ca-pectinate) beads via ionotropic gelation, where calcium ions cross-link with the negatively charged carboxyl groups on pectin chains [55]. This mild encapsulation method preserves the structural and functional integrity of sensitive bioactive compounds, making it ideal for protein and peptide delivery. For instance, β-lactamase enzymes have been successfully encapsulated within pectin beads for colonic release, where they serve to degrade residual β-lactam antibiotics [56]. This strategy helps in preserving the natural colonic microbiota and reduces the selective pressure that drives antimicrobial resistance.

Beyond peptide and enzyme delivery, pectin beads have been employed for micronutrient supplementation, such as iron delivery. Iron-loaded PBs, especially those incorporating ferrous sulfate, offer a novel route to enhance iron bioavailability in the colon, which can be beneficial for individuals with iron deficiency anaemia or malabsorption disorders. These iron-PB systems are designed to release their payload specifically in the lower gut, potentially minimizing GI irritation commonly associated with conventional iron supplements. Comprehensive characterization of these systems is crucial for evaluating their suitability in pharmaceutical applications. Techniques such as SEM have been employed to evaluate surface morphology and structural integrity, while thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) offers insights into their thermal stability. In vitro intestinal transport models, such as Caco-2 monolayers, have been employed to study absorption kinetics and ensure that the encapsulated compounds maintain their bioactivity after release [57]. Collectively, these findings highlight the significant potential of pectin-based beads in site-specific oral delivery and micronutrient supplementation.

Immunization and advanced delivery systems

Colon-targeted delivery systems are also valuable for immunization purposes, especially for protein-based drugs that require protection from enzymatic degradation and have inherently poor oral bioavailability. Oral administration of such bio macromolecules is often limited by their susceptibility to proteolytic enzymes in the stomach and small intestine, as well as by their poor permeability across the intestinal epithelium. Pectin’s natural resistance to gastric and intestinal enzymatic breakdown, along with its excellent biocompatibility and mucoadhesive properties, makes it an ideal candidate for non-parenteral immunization platforms. When used in the form of pectin beads or hydrogels, this polysaccharide can encapsulate antigens or protein-based therapeutics, shielding them during transit through the upper GI tract and enabling their release in the colon, where enzymatic activity is minimal and immune tissue such as Peyer’s patches is more accessible [58]. This approach not only improves antigen stability and absorption but also reduces the frequency of administration compared to traditional injection-based regimens. Moreover, colon-targeted systems can be engineered for sustained or pulsatile release, allowing for prolonged antigen exposure and potentially enhancing immune response. These delivery platforms represent a promising avenue for the oral administration of vaccines, especially in pediatric, geriatric, or needle-averse populations, where ease of administration and patient compliance are critical.

Chitosan and alginate-coated PB

Amidated pectin hydrogel beads have been created as a platform for the controlled release of chloroquine. Chitosan solution has been applied to albumin and alginate microspheres to improve their properties. Chitosan-coated cisplatin albumin microcapsules demonstrated enhanced antitumor activity compared to uncoated versions [59]. The release of cisplatin was effectively controlled by using chitosan. The chitosan coating enhanced the stability of the microspheres, allowing for slower and extended drug release. This controlled-release method improved treatment effectiveness while reducing the potential adverse effects associated with cisplatin administration. The incorporation of chitosan into albumin and alginate microspheres holds considerable promise for enhancing drug delivery systems in cancer therapy. A modified method was employed to develop chitosan-enhanced alginate gel beads, where the encapsulation process relies on electrostatic interactions during the formation of the reinforced gels. However, additional studies are necessary to assess the long-term stability and biocompatibility of these chitosan-reinforced alginate gel beads in vivo before their potential in cancer therapy can be confirmed. The properties of amidated PB can be altered by creating a polyelectrolyte complex membrane around them using cationic polymers like chitosan, following techniques similar to those used for alginate gel beads [60]. Chitosan, due to its cationic polyelectrolyte nature, can strongly interact with mucus or negatively charged mucosal surfaces through electrostatic attraction. The combination of chitosan-reinforced alginate gel beads and amidated polybutadiene (PB) exhibits considerable promise for targeted cancer therapy; nonetheless, further investigation and assessment are required. This interaction may enhance the mucoadhesive characteristics of the beads, facilitating prolonged drug release and increased therapeutic effectiveness. Moreover, chitosan's capacity to enhance cellular uptake and penetration may augment the efficacy of the drug delivery system. The application of a chitosan coating on PB markedly decreased albumin release at pH 5 and other pH levels. In uncoated beads, an elevation in CaCl₂ concentration diminished albumin release by enhancing cross-linking and restricting bead swelling. The release of albumin from chitosan-coated beads remained consistent despite a reduction in swelling, potentially attributed to the creation of a chitosan-pectin complex. The structural properties of pectin caused chitosan-coated PB to show less swelling in acidic conditions and greater swelling in alkaline environments. Albumin release was constrained at pH 5 and maximized at pH 7.4, suggesting that the chitosan coating markedly affects the release profile, likely due to robust ionic interactions at pH 5.

LIMITATIONS

While pectin beads (PB) demonstrate considerable potential in pharmaceutical applications, several limitations must be acknowledged. PB tends to be unstable in alkaline environments due to β-elimination reactions, which lead to polymer degradation and reduced gel integrity, particularly in intestinal conditions. The freeze-drying process, though useful for improving shelf life and porosity, is costly, time-consuming, and difficult to scale up, often resulting in bead cracking or structural inconsistencies. The use of chitosan coatings, despite improving mucoadhesion and sustained drug release, may introduce immunogenic risks, particularly in individuals sensitive to shellfish-derived components. Moreover, critical research gaps remain, such as the need for comprehensive in vivo studies evaluating PB for nasal drug delivery and insufficient data on the long-term physical and chemical stability of these formulations under varied storage conditions. Addressing these limitations through targeted research and formulation optimization is essential for the successful clinical translation of PB-based drug delivery systems.

CONCLUSION

The review provides a comprehensive analysis of pectin beads (PB) from extraction to their pharmaceutical applications. The stages of PB formation, including pectin solution preparation, active agent incorporation, and optimization, highlight the precise control over drug release. Gelation, swelling, and SEM analyses offer insights into the physicochemical properties of PB, while particle size and zeta potential assessments contribute to understanding their stability and functionality. The scope of this review emphasizes the potential of PB in targeted drug delivery, immunization, and coating with materials such as chitosan and alginate. This work underscores the growing importance of PB in advancing pharmaceutical formulations.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Jiang P, Ren Y, Zhang Y. Effects of pectin on intestinal microbiota and human health. TNS. 2023;4(1):321-30. doi: 10.54254/2753-8818/4/20220581.

Liang WL, Liao JS, Qi JR, Jiang WX, Yang XQ. Physicochemical characteristics and functional properties of high methoxyl pectin with different degree of esterification. Food Chem. 2022;375:131806. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131806, PMID 34933235.

Saldivar Guevara MM, Saucedo Rivalcoba VE, Rivera Armenta JL, Elvira Torales LI. Evaluation of a cross linking agent in the preparation of films based on chitosan and pectin for food packaging applications. Cellulose Chem Technol. 2022;56(9-10):1061-70. doi: 10.35812/CelluloseChemTechnol.2022.56.94.

Yu Y, Cui L, Liu X, Wang Y, Song C, Pak U. Determining methyl-esterification patterns in plant-derived homogalacturonan pectins. Front Nutr. 2022;9:925050. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.925050, PMID 35911105.

Pieczywek PM, Cybulska J, Zdunek A. An atomic force microscopy study on the effect of β-galactosidase α-L-rhamnosidase and α-L-arabinofuranosidase on the structure of pectin extracted from apple fruit using sodium carbonate. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):4064. doi: 10.3390/ijms21114064, PMID 32517129.

Paoletti S, Donati I. pH effects on the conformations of galacturonan in solution: conformational transition and loosening extension and stiffness. Polysaccharides. 2023;4(3):271-324. doi: 10.3390/polysaccharides4030018.

Ortenzi MA, Antenucci S, Marzorati S, Panzella L, Molino S, Rufian Henares JA. Pectin-based formulations for controlled release of an ellagic acid salt with high solubility profile in physiological media. Molecules. 2021;26(2):433. doi: 10.3390/molecules26020433, PMID 33467593.

Nguyen TT, Hirano T, Chamida RN, Septiani EL, Nguyen NT, Ogi T. Porous pectin particle formation utilizing spray drying with a three-fluid nozzle. Powder Technol. 2024;440:119782. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2024.119782.

Paoletti S, Donati I. pH effects on the conformations of galacturonan in solution: conformational transition and loosening extension and stiffness. Polysaccharides. 2023;4(3):271-324. doi: 10.3390/polysaccharides4030018.

Kedir WM, Deresa EM, Diriba TF. Pharmaceutical and drug delivery applications of pectin and its modified nanocomposites. Heliyon. 2022;8(9):e10654. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10654, PMID 36164543.

Huang ST, Yang CH, Lin PJ, Su CY, Hua CC. Multiscale structural and rheological features of colloidal low-methoxyl pectin solutions and calcium induced sol-gel transition. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2021;23(35):19269-79. doi: 10.1039/D1CP02778F, PMID 34524316.

Kapoor DU, Garg R, Gaur M, Pareek A, Prajapati BG, Castro GR. Pectin hydrogels for controlled drug release: recent developments and future prospects. Saudi Pharm J. 2024;32(4):102002. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2024.102002, PMID 38439951.

Emrich T, Stracke JO, Guo X, Damhjell K, Moelleken J, Vogel R. Increasing robustness, reliability and storage stability of critical reagents by freeze drying. Bioanalysis. 2021;13(10):829-40. doi: 10.4155/bio-2020-0299, PMID 33890493.

Wu CL, Liu ZW, Liao JS, Qi JR. Effect of enzymatic de-esterification and RG-I degradation of high methoxyl pectin (HMP) on sugar acid gel properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;265(1):130724. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130724, PMID 38479656.

Feng S, Yi J, Ma Y, Bi J. The role of amide groups in the mechanism of acid induced pectin gelation: a potential pH-sensitive hydrogel based on hydrogen bond interactions. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;141:108741. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108741.

Cao L, Lu W, Mata A, Nishinari K, Fang Y. Egg box model-based gelation of alginate and pectin: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;242:116389. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116389, PMID 32564839.

Liu ZH, Ai S, Xia Y, Wang HL. Intestinal toxicity of Pb: structural and functional damages effects on distal organs and preventive strategies. Sci Total Environ. 2024;931:172781. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172781, PMID 38685433.

Qian Q, Liang J, Ren Z, Sima J, Xu X, Rinklebe J. Digestive fluid components affect speciation and bioaccessibility and the subsequent exposure risk of soil chromium from stomach to intestinal phase in in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. J Hazard Mater. 2024;463:132882. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132882, PMID 37939559.

Begum RA, Fry SC. Arabinogalactan proteins as boron acting enzymes cross linking the rhamnogalacturonan-II domains of pectin. Plants (Basel). 2023;12(23):3921. doi: 10.3390/plants12233921, PMID 38068557.

Bertsch Socorro A. Fermentation of by-products from the dairy and cereal industry by lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus and saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front Nutr . 2019 Apr 12;6:42. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00042.

Roushenas S, Nikzad MF, Ghoreyshi AA, Ghorbani M. Magnetic pectin nanocomposite for efficient adsorption of heavy metals from aqueous solution. J Water Environ Nanotechnol. 2022;7(1):69-88. doi: 10.22090/jwent.2022.01.006.

Jiang B, Yu D, Zhang Y, Hamza T, Feng H, Hoag SW. Delivery of a therapeutic antibody to the lower gastrointestinal tract for the treatment of clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Pharm Dev Technol. 2023;28(2):232-9. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2023.2174553, PMID 36789978.

Sabater C, Blanco Doval A, Margolles A, Corzo N, Montilla A. Artichoke pectic oligosaccharide characterisation and virtual screening of prebiotic properties using in silico colonic fermentation. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;255:117367. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117367, PMID 33436200.

Butte K, Momin M, Deshmukh H. Optimisation and in vivo evaluation of pectin-based drug delivery system containing curcumin for colon. Int J Biomater. 2014;2014:924278. doi: 10.1155/2014/924278, PMID 25101127.

Suberkropp K. Pectin-degrading enzymes: polygalacturonase and pectin lyase. In: Barlocher F, Gessner MO, Graca MA, editors. Methods to study litter decomposition: a practical guide. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 419-24. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-30515-4_45.

Vityazev FV, Khramova DS, Saveliev NY, Ipatova EA, Burkov AA, Beloserov VS. Pectin glycerol gel beads: preparation characterization and swelling behaviour. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;238:116166. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116166, PMID 32299571.

Morales E, Quilaqueo M, Morales Medina R, Drusch S, Navia R, Montillet A. Pectin chitosan hydrogel beads for delivery of functional food ingredients. Foods. 2024;13(18):2885. doi: 10.3390/foods13182885, PMID 39335814.

Wong SK, Lawrencia D, Supramaniam J, Goh BH, Manickam S, Wong TW. In vitro digestion and swelling kinetics of thymoquinone loaded Pickering emulsions incorporated in alginate chitosan hydrogel beads. Front Nutr. 2021;8:752207. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.752207, PMID 34671634.

Wu B, Li Y, Li Y, Li H, Li L, Xia Q. Encapsulation of resveratrol loaded pickering emulsions in alginate/pectin hydrogel beads: improved stability and modification of digestive behavior in the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;222(A):337-47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.09.175, PMID 36152701.

Lin D, Cai B, Wang L, Cai L, Wang Z, Xie J. A viscoelastic PEGylated poly(glycerol sebacate)-based bilayer scaffold for cartilage regeneration in full-thickness osteochondral defect. Biomaterials. 2020;253:120095. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120095, PMID 32445809.

Heda GD. A simple method of drying polyacrylamide slab gels that eliminates cracking. BioTechniques. 2021;70(1):54-7. doi: 10.2144/btn-2020-0117, PMID 33222512.

Popov S, Paderin N, Khramova D, Kvashninova E, Melekhin A, Vityazev F. Characterization and biocompatibility properties in vitro of gel beads based on the pectin and κ-carrageenan. Mar Drugs. 2022;20(2):94. doi: 10.3390/md20020094, PMID 35200624.

Hu C, Yuan X, Zhao R, Hong B, Chen C, Zhu Q. Scale-up preparation of manganese iron prussian blue nanozymes as potent oral nanomedicines for acute ulcerative colitis. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13(16):e2400083. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202400083, PMID 38447228.

Hoseini B, Jaafari MR, Golabpour A, Momtazi Borojeni AA, Karimi M, Eslami S. Application of ensemble machine learning approach to assess the factors affecting size and polydispersity index of liposomal nanoparticles. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):18012. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-43689-4, PMID 37865639.

Zheng L, Xu Y, Li Q, Zhu B. Pectinolytic lyases: a comprehensive review of sources category property structure and catalytic mechanism of pectate lyases and pectin lyases. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2021;8(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s40643-021-00432-z, PMID 38650254.

Ozakar RS. Development and in vitro characterization of gastroretentive formulations as calcium pectinate hydrogel pellets of pregabalin by ionotropic gelation method. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 2022;56(1s):s9-s20. doi: 10.5530/ijper.56.1s.38.

Handschuh Wang S, Wang B, Wang T, Stadler FJ. Measurement principles for room temperature liquid and fusible metals surface tension. Surf Interfaces. 2023;39:102921. doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2023.102921.

Atara SA, Soniwala MM. Formulation and evaluation of pectin calcium chloride beads of azathioprine for colon targeted drug delivery system. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;10(1):172-9. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2018v10i1.23175.

Kamble D, Singhavi D, Tapadia S, Khan S. Investigation of pectin hydroxypropyl methylcellulose coated floating beads for pulsatile release of piroxicam. Turk J Pharm Sci. 2020;17(5):542-8. doi: 10.4274/tjps.galenos.2019.99896, PMID 33177936.

Rebitski EP, Darder M, Carraro R, Aranda P, Ruiz Hitzky E. Chitosan and pectin core shell beads encapsulating metformin clay intercalation compounds for controlled delivery. New J Chem. 2020;44(24):10102-10. doi: 10.1039/C9NJ06433H.

Ramteke KH, Nath L. Formulation evaluation and optimization of pectin bora rice beads for colon targeted drug delivery system. Adv Pharm Bull. 2014;4(2):167-77. doi: 10.5681/apb.2014.025, PMID 24511481.

Faulkner B, Delgado Charro MB. Cardiovascular paediatric medicines development: have paediatric investigation plans lost heart? Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(12):1176. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12121176, PMID 33276598.

Li Y, Wu B, Li Y, Li H, Ji S, Xia Q. pH-responsive pickering emulsions pectin hydrogel beads for loading of resveratrol: preparation characterization and evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2023;79:104008. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.104008.

Sriamornsak P. Sustained release drug delivery system using calcium pectinate gel coated pellets. Pharma Indochina. 1997;103.

Reichembach LH, De Oliveira Petkowicz CL, Guerrero P, De La Caba K. Pectin and pectin/chitosan hydrogel beads as coffee essential oils carrier systems. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;151:109814. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.109814.

Ramadan H, Moustafa N, Ahmed RR, El Shahawy AA, Eldin ZE, Al Jameel SS. Therapeutic effect of oral insulin chitosan nanobeads pectin dextrin shell on streptozotocin diabetic male albino rats. Heliyon. 2024;10(15):e35636. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35636, PMID 39170289.

Ananthu MK, Chintamaneni PK, Shaik SB, Thadipatri R, Mahammed N. Artificial neural networks in optimization of pharmaceutical formulations. Saudi J Med PharmSci. 2021;7(8):368-78.

Deshmukh R. Bridging the gap of drug delivery in colon cancer: the role of chitosan and pectin based nanocarriers system. Curr Drug Deliv. 2020;17(10):911-24. doi: 10.2174/1567201817666200717090623, PMID 32679018.

Zhou P, Zheng M, Li X, Zhou J, Li W, Yang Y. Load mechanism and release behaviour of synephrine loaded calcium pectinate beads: experiments characterizations theoretical calculations and mathematical modeling. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;242(3):125042. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125042, PMID 37230446.

Pawar AP, Prabakaran V, Gadhe AR, Marathe A. Effect of calcium tartarate and sodium bicarbonate as internal gelling agent on entrapment of metronidazole in calcium pectinate beads. World J Pharm Res. 2024;13(3):1017-26.

Mishra RK, Banthia AK, Majeed AB. Pectin based formulations for biomedical applications: a review. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2012;5(4):1-7.

Nataraj D, Reddy N. Chemical modifications of alginate and its derivatives. Int J Chem Res. 2020;4(1):1-17. doi: 10.22159/ijcr.2020v4i1.98.

Morales E, Quilaqueo M, Morales Medina R, Drusch S, Navia R, Montillet A. Pectin chitosan hydrogel beads for delivery of functional food ingredients. Foods. 2024 Sep 12;13(18):2885. doi: 10.3390/foods13182885, PMID 39335814.

Poojari R, Srivastava R. Composite alginate microspheres as the next-generation egg-box carriers for biomacromolecules delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2013;10(8):1061-76. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.796361, PMID 23651345.

Duan H, Wang X, Azarakhsh N, Wang C, Li M, Fu G. Optimization of calcium pectinate gel production from high methoxyl pectin. J Sci Food Agric. 2022;102(2):757-63. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.11409, PMID 34216009.

Mishra A, Maity D, Pradhan D, Halder J, Rajwar TK, Rai VK. Development and evaluation of novel amoxicillin and phytic acid loaded gastro-retentive mucoadhesive pectin microparticles for the management of Helicobacter pylori infections. J Pharm Innov. 2024;19(2):6. doi: 10.1007/s12247-024-09820-2.

Zhang M, Su Y, Li J, Chang C, Gu L, Yang Y. Fabrication of phosphatidylcholine-EGCG nanoparticles with sustained release in simulated gastrointestinal digestion and their transcellular permeability in a Caco-2 monolayer model. Food Chem. 2023;437(1):137580. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137580, PMID 39491254.

Park JI, Cho SW, Kang JH, Park TE. Intestinal peyer’s patches: structure function and in vitro modeling. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2023;20(3):341-53. doi: 10.1007/s13770-023-00543-y, PMID 37079198.

Kotb ES, Alhamdi HW, Alfaifi MY, Darweesh O, Shati AA, Elbehairi SE. Examining the quaternary ammonium chitosan Schiff base-ZnO nanocomposite’s potential as protective therapy for rats cisplatin induced hepatotoxicity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;276(1):133616. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133616, PMID 39009258.

Bediako JK, El Ouardi Y, Massima Mouele ES, Mensah B, Repo E. Polyelectrolyte and polyelectrolyte complex incorporated adsorbents in water and wastewater remediation a review of recent advances. Chemosphere. 2023;325:2023.138418. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138418.