Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 354-366Original Article

DESIGN AND CHARACTERIZATION OF LULICONAZOLE-ENCAPSULATED TRANSFEROSOMES IN THERMOSENSITIVE OCULAR GEL

M. DIVYANAND1, SNEH PRIYA1*, MELANIE ASHEL DSOUZA1, MURARI UPADHYAY2

1Nitte (Deemed to be University), NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (NGSMIPS), Department of Pharmaceutics, Mangalore, Karnataka, India. 2Shree Devi College of Pharmacy, Kenjar Airport Road, Mangalore-574142, India

*Corresponding author: Sneh Priya; *Email: snehpriya123@nitte.edu.in

Received: 13 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 08 Sep 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The present study develops and optimizes a thermosensitive in-situ gel containing Luliconazole-loaded transferosomes (LCZ-TFs) to improve ocular bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy through enhanced permeation and prolonged retention.

Methods: Transferosomes (TFs) were prepared using the thin film hydration method. To optimize the formulation, a Box-Behnken design was used to study the effects of three variables: the concentration of soya phosphatidylcholine (SPC), Tween 80, and chloroform and evaluated for their influence on vesicle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and percentage entrapment efficiency (EE). Zeta potential and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) analysis were performed for optimized formulation. The optimized transferosome was incorporated into the thermosensitive in-situ gel containing Pluronic F127 (15% w/v) and Pluronic F68 (1% w/v) and evaluated for in vitro drug release using a membrane diffusion technique and ex vivo permeation studies on goat cornea using a modified Franz diffusion cell.

Results: The optimized TFs showed a particle size of 205.5 nm, PDI of 0.236, and EE of 77.43%. The zeta potential was recorded at −53.9 mV, indicating good stability. TEM revealed well-formed spherical vesicles. Drug release studies demonstrated a sustained release profile from the transferosomes in situ gel with release kinetics following first-order kinetics and Higuchi model mechanisms. In ex vivo permeation studies, the transferosomes in situ gel showed a 1.68-fold higher permeation than the conventional gel. The formulation passed sterility and isotonicity tests and retained antifungal activity comparable to a marketed product, as shown by its zone of inhibition. Additionally, the hen’s egg test–chorioallantoic membrane (HET-CAM) test confirmed the gel was non-irritant and safe for ocular use.

Conclusion: Overall, the transferosomes in situ gel significantly improved ocular retention and prolonged the drug's release, which enhances the therapeutic effectiveness of Luliconazole in treating fungal keratitis.

Keywords: Transferosomes, Luliconazole (LCZ), Box-behnken design, Zeta potetail, In situ gel

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55006 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Keratitis is an inflammation of the corneal tissue, often triggered by microbial infections involving fungi, viruses, bacteria, or protozoa. Among these, fungal keratitis (FK) has become an increasingly reported condition, with Fusarium, Aspergillus, and Candida species being the primary culprits. Other fungi such as Paecilomyces, Scedosporium, and Culvaria have also been implicated in severe cases. This condition can lead to corneal ulceration, scarring, and even blindness if left untreated [1, 2]. While bacterial keratitis typically responds well to treatment, fungal keratitis remains challenging due to delayed diagnosis and limited drug penetration. Commonly used antifungal treatments include topical natamycin and amphotericin B, though no universal standard therapy exists [3, 4]. Current options fall under three main antifungal classes: polyenes, triazoles, and echinocandins.

Luliconazole (LCZ) is a new-generation imidazole antifungal agent with potent activity against fungi that commonly affect the eye, such as Fusarium, Aspergillus, and Candida. Though primarily used for superficial skin infections, recent interest has grown in exploring its ocular applications [5]. LCZ belongs to BCS Class II, signifying low water solubility but high permeability, which severely limits its bioavailability when applied as conventional eye drops [6]. Effective ocular drug delivery remains a major challenge due to the eye's complex anatomy and physiological barriers. Rapid tear turnover, blinking, corneal impermeability, and nasolacrimal drainage drastically reduce drug absorption, resulting in less than 5% of the instilled dose reaching intraocular tissues [7, 8]. The drugs have low aqueous solubility and high molecular weight, further limiting the corneal permeation as seen with natamycin [9]. The drug with small-molecule weight in conventional doses, such as drops, necessarily requires frequent administration to maintain therapeutic levels.

To improve the corneal penetration, residence time and bioavailability of drugs, thereby reducing their dose and dose frequency, Novel Drug Delivery Systems were stated to be developed, such as solid lipid nanoparticles of natamycin [10], liposomes of timolol maleate [11], niosomes of flurbiprofen [12], transferosomes of linoleic acid [13]. The transferosomes, introduced in the 1990s, are ultra-deformable lipid vesicles composed of phospholipids and surfactants (edge activators) [14]. These carriers enhance penetration across biological barriers and protect the drug from degradation. Their flexibility and amphiphilic nature make them highly effective in ocular delivery systems [15]. In addition, the use of in situ gels has gained attention for ophthalmic drug delivery. These formulations are administered as low-viscosity liquids that undergo gelation upon exposure to ocular conditions such as temperature, pH, or ionic strength to form a mucoadhesive gel. This transformation allows prolonged retention on the eye surface, increased contact time with the cornea, and minimizes precorneal drug loss [16]. The integration of transferosomes into an in situ gel matrix combines the advantages of both systems, resulting in enhanced bioavailability and sustained drug release. Uwaezuoke et al. (2022) reported the successful formulation of linoleic acid-based transferosomes for ocular delivery of cyclosporine A, demonstrating superior corneal penetration and prolonged therapeutic effect when compared to conventional systems [17].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

LCZ was obtained from Yarrow Chem Products, Mumbai. Soya lecithin was purchased from HI Media Laboratories, Mumbai. Tween 80 and Chloroform were purchased from Loba Chemie, Mumbai. Methanol, Pluronic F127, and Pluronic F68 were also procured from Loba Chemie, Mumbai.

Preparation and characterisation of luliconazole-loaded transferosomes

Experimental design

To achieve an optimized formulation, a statistical Design of Experiments (DOE) was implemented using Design Expert® software (v11.0.3.0). A three-level, three-factor Box-Behnken design was used to evaluate the effects of key formulation variables: concentration of soya phosphatidylcholine (SPC), Tween 80, and chloroform. The design aimed to minimize vesicle size and polydispersity index (PDI), while maximizing entrapment efficiency (EE%). A total of 14 runs were generated and analysed. The vesicle size (Y1), PDI (Y2), and entrapment efficiency (Y3) were chosen as dependent response variables. The design provided statistical modelling of how independent factors influenced formulation outcomes, helping to determine the most desirable combination for a stable and effective transferosomes system [18].

Formulation of LCZ-TFs

LCF-TF were formulated using the thin-film hydration method. The active drug LCZ, SPC (lipid), and Tween 80 (surfactant) were accurately weighed and dissolved in a chloroform-methanol mixture (ratios varied per DOE design) within a 250 ml round-bottom flask. The organic solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure at 45 °C and 200 rpm using a rotary evaporator, forming a thin lipid film on the flask walls. This film was hydrated with 10 ml of Milli-Q water, and the dispersion was left to swell at room temperature for 2 h. Probe sonication was then performed at 50% amplitude with an alternating 5-second on/off pulse for 20 min to reduce vesicle size and enhance uniformity [18].

Evaluation of LCZ-TFs

Vesicle size and PDI

Vesicle size and polydispersity index of both individual formulations and the optimized batch were measured using a Malvern Zeta sizer at 25 °C with a detection angle of 90°, after suitable dilution in Milli-Q water. These parameters reflect size distribution and uniformity [19]. All the samples were analysed three times, and the results added in the table are the mean with standard deviation.

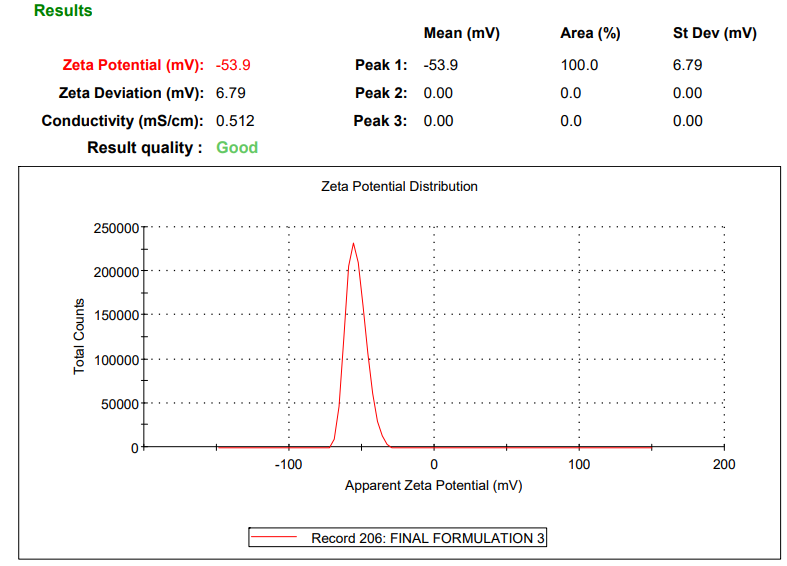

Zeta potential

The zeta potential of the optimized formulation was determined by electrophoretic light scattering using a Malvern ZetaSizer. A high negative potential (−53.9 mV) indicated good physical stability due to electrostatic repulsion between particles [19].

Percentage entrapment efficiency

In this study, the entrapment efficiency of Luliconazole-loaded transferosomes was determined using the centrifugation method. Precisely, 10 ml of each formulation was centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C using a high-speed refrigerated centrifuge. This process allowed for the separation of unentrapped (free) drug in the supernatant from the drug entrapped within the vesicles [19]. Following centrifugation, 1 ml of the clear supernatant was withdrawn and appropriately diluted with simulated tear fluid (STF, pH 7.4). The concentration of free Luliconazole (Cf) was quantified using a UV-visible spectrophotometer at 295 nm, a wavelength optimized for its accurate detection. The total drug content (Ct) was determined from an identical formulation that had not been subjected to centrifugation. The entrapment efficiency was calculated using the formula:

Entrapment efficiency (%) =

Where Ct is the amount of total drug and Cf is the concentration of unentrapped drug.

Formulation and characterization of optimized batch of LCZ-TFs

One-way ANOVA was applied using the commercially accessible software program Design-Expert version 13 to evaluate the effect of process variables on the responses and refine the formulation parameters. The optimization of LCZ-TFs was carried out using constraints with minimum vesicle size, minimum PDI and maximum %EE. The solution with very good desirability (greater than 0.8) was suggested by the software as optimized formulation. 105.5 mg of soya lecithin, 1.08 % of tween 80 and 50.03 % of chloroform were used to formulate the optimized formulation. Vesicle size, size distribution, and %EE of the optimized formulation are achieved similarly to other batches.

Surface morphology by TEM

TEM is the most frequently used imaging method for the evaluation of the structure of transferosomes. It can be used to study the vesicle shape and surface morphology of transferosomes, such as roughness, smoothness and aggregation. One drop of diluted sample was placed on the surface of a carbon-coated copper grid, after staining with one drop of 2% W/W aqueous solution of phosphotungstic acid. Later, the sample was left to dry for 10 min and TEM images were taken [19].

Formulation of transferosomes loaded in situ gel formulation

A 1% thermosensitive in situ gel (IG) was developed for ocular delivery using a blend of Pluronic F127 (15% w/v) and Pluronic F68 (1% w/v) to achieve gelation near physiological temperature (≈37 °C). The polymers were dissolved separately in cold water, refrigerated for 24 h to remove air bubbles, and then combined. For the in situ gel of Luliconazole-loaded transferosome (IGT), 4 ml of LCZ-TFs suspension (equivalent to 100 mg drug) was mixed with 6 ml of the polymeric blend. For the conventional in situ gel with pure drug (IGD), 100 mg of pure LCZ was dispersed in water before blending. Benzalkonium chloride (0.01% w/v) was added as a preservative, and the pH was adjusted to 6.5–7.0. The final formulations were sterilized using 0.22 µm filtration and stored at 4 °C for further evaluation [20, 21].

Evaluation of the transferosomes loaded in situ gel formulation

Determination of the visual appearance

Visual inspection was performed to assess the physical appearance of the in-situ gel formulation. The optimized gel was observed for clarity, consistency, colour, and particulate matter. The formulation was found to be clear, transparent, and free of visible aggregates or precipitation, indicating successful polymer dispersion and physical stability of the preparation.

pH

To ensure ocular compatibility, the pH of the gel was measured using a digital pH meter. The electrode was immersed in the sample, and readings were taken after 1 min equilibration. The pH was close to physiological tear pH (around 7.4), confirming that the formulation is non-irritant and suitable for ophthalmic use [21].

In vitro gelation study

The gelling ability of the in-situ gel was evaluated. A drop of the optimised formulation was added to a vial containing two millilitres of freshly made, 37 °C equilibrated simulated tear fluid (STF) to ascertain the gelling capability. The duration required for the formation of gel and for dissolution of the formed gel [22, 23].

The in vitro gelling capacity was mainly divided into 3 categories based on gelation time and time period the formed gel remains.

(+): Gels in few second and disperse immediately

(++): Immediate gelation, does not disperse rapidly

(+++): gelation after few minutes remains for extended period.

Rheological studies

Rheological behaviour was evaluated to determine flow characteristics before and after gelation. The Brookfield viscometer (Spindle No. 61) was used for this purpose. The viscosity of the in-situ gel was measured at room temperature and physiological body temperature (37 °C) in triplicate. These measurements were crucial in evaluating the formulation’s ability to remain liquid at lower temperatures for ease of installation while effectively transitioning into a gel upon ocular administration [24].

In vitro drug release studies

In vitro release studies of in-situ gel formulations were performed using a dialysis tube with a molecular weight cutoff of 8,000–14,000. The formulation IGD and IGT equivalent to 2 mg of LCZ was placed into a dialysis tube and introduced into 50 ml of simulated tear fluid (STF) maintained at 34.5 °C in a shaking water bath. To ensure reproducibility, three samples were tested concurrently under the same experimental conditions. Sink conditions were maintained in this study. The release medium (3 ml) was withdrawn at appropriate intervals (0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240, 360, 420, and 480 min), and replaced by 3 ml of fresh medium. The collected samples were appropriately diluted and analysed using a UV-visible spectrophotometer at λmax 293 nm to determine the cumulative drug release [25, 26]. The drug release profiles were further analysed using zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, and Korsmeyer-Peppas kinetic models to determine the mechanism of drug release.

Erosion study

The in vitro erosion study was performed to evaluate the gel erosion behaviour of the in situ gel formulation. An accurately measured 1 g quantity of the prepared in situ gel was placed on a pre-weighed 0.22 µm cellulose acetate membrane. The membrane was then placed in a beaker containing 50 ml of STF, pH 7.4, maintained at 35±1 °C. At predetermined time intervals (every hour up to 8 h), the membrane was withdrawn, and excess surface fluid was removed carefully with filter paper. The remaining gel was gently removed, and the membrane was dried and reweighed. The amount of gel eroded at each interval was calculated based on the weight difference. The test was performed in triplicate, and the mean values along with standard deviation were recorded [20].

Ex vivo permeation study

The ex vivo corneal permeation studies were conducted using goat corneas obtained from a licensed local slaughterhouse, where the animals were sacrificed for commercial purposes. Fresh goat eyes were obtained from a local slaughterhouse, and the cornea, along with the scleral tissue, was dissected to facilitate easy handling. These tissues were immediately cleaned with STF, pH 7.4, and wrapped with film to prevent dehydration. Subsequently, they were stored at 4 °C until used within 4 h of harvest. The corneas were mounted between the donor and receptor compartments of Franz diffusion cells. Three simultaneous samples were tested under identical conditions to ensure reproducibility. The donor compartment was loaded with 1 ml of the prepared IGD and IGT formulation, while the receptor compartment contained freshly prepared STF, pH 7.4, maintained at 34±0.5 °C and stirred continuously. Samples were withdrawn at regular intervals up to 8 h and analyzed using UV-Visible spectrophotometry at 296 nm. The cumulative amount of drug permeated per surface area was plotted as a function of time, and flux (μg/cm²/h) and permeability coefficient (cm/h) were calculated. [17, 27].

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad InStat Demo. All experimental results are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were performed using an independent unpaired t-test. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sterility test

Sterility was tested to ensure the formulation’s microbiological safety for ocular use. The test was performed using the direct inoculation method, where the formulation was added to two growth media: fluid thioglycolate medium for bacteria and soybean-casein digest medium for fungi. After incubation, the absence of turbidity or microbial growth confirmed that the in-situ gel formulation is sterile and safe for ophthalmic application [28, 29].

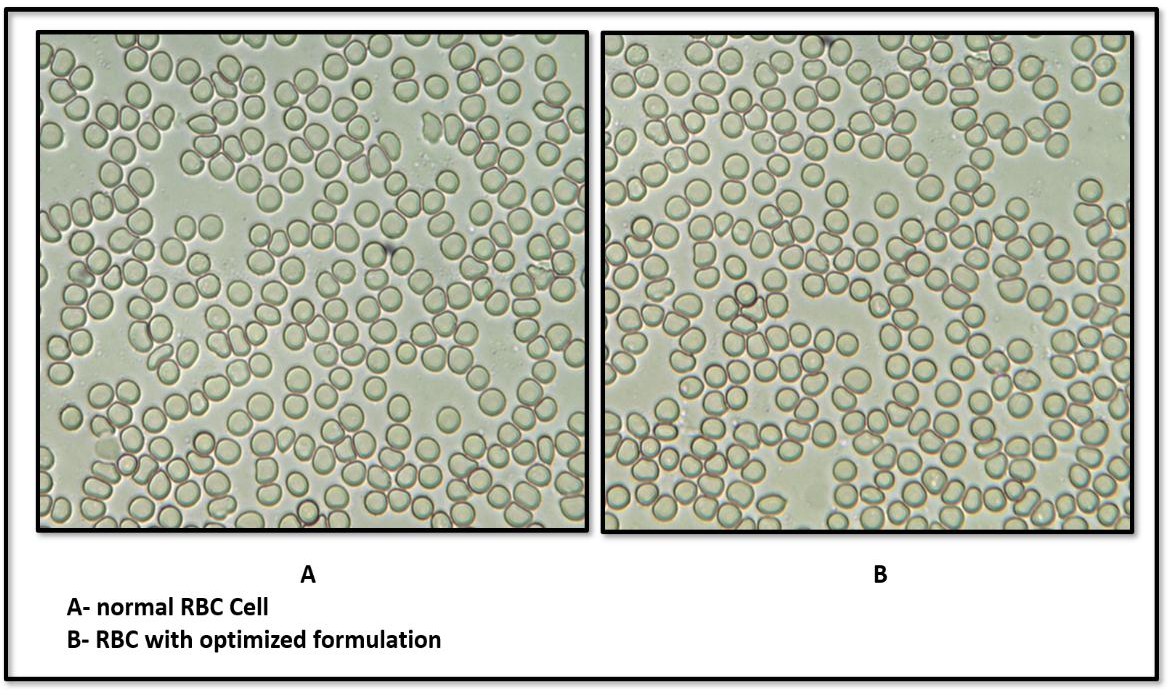

Isotonicity

To evaluate the isotonicity of the optimised formulation, a few drops of blood were mixed with a few drops of the optimised formulation on a glass slide. This mixture was then smeared and observed under a high-resolution Biovis microscope. The procedure was similarly performed using saline water for comparison. The main focus during the observation was on the shape of the red blood cells (RBCs), particularly looking for any signs of shrinkage or bulging. The RBCs from the optimised formulation were compared with those from the saline water to assess differences in cell morphology [28].

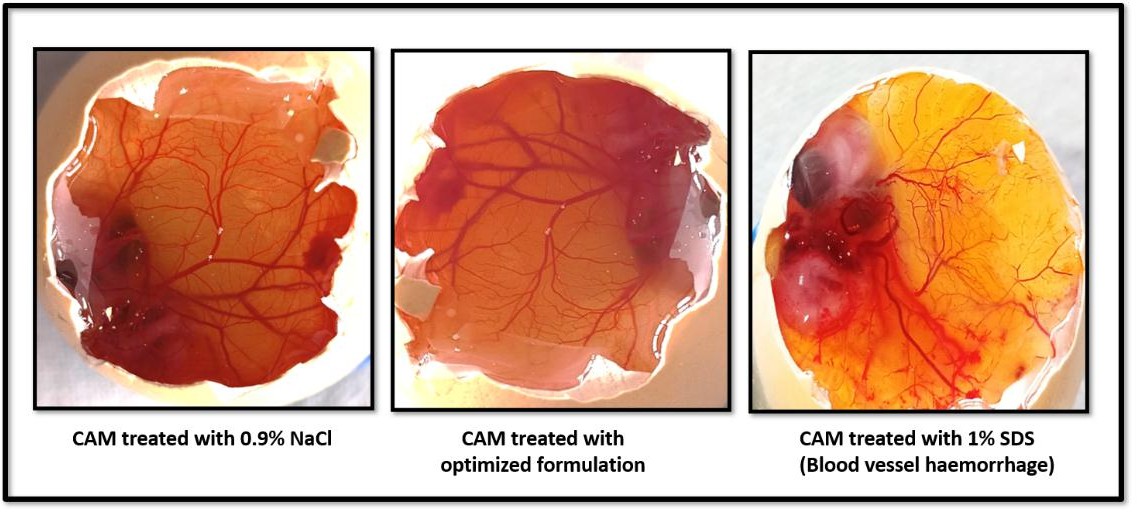

Ocular irritation studies HET-CAM test

Several in vitro methods have been used to investigate the toxicity of potential eye irritants with a view to replacing in vivo eye irritation testing. In the HET-CAM test, chemicals are placed in direct contact with the chorioallantoic membrane of the hen's egg, which mimics the eye’s vasculature very closely [30]. The HET-CAM was utilized to conduct ex vivo ocular irritation and tolerance tests. Freshly gathered fertilized chicken eggs that are not more than seven days old were utilized in this test. Eggs that weighed between 50 and 60 g were used, and any that had physical flaws like cracking were excluded. The chosen eggs were kept in an incubator. To prevent embryo adhesion, eggs were physically rotated five times on each day of incubation; later, eggs were candled, and damaged or nonviable eggs were discarded. After that, the eggs were transferred without rotating to the incubator by holding the larger end of the eggs upward and kept for a full day. On the ninth day, eggs were taken out, and the air cell was marked on the top. Holes were made in the eggshell’s air sac while avoiding harming the chorioallantoic membrane. Using a sterile surgical blade, one egg was first cracked open to examine the development of CAM. The maturation of visible veins on the surface confirmed the development of CAM. Additionally, three groups of eggs containing six eggs each were created: IGT, negative control (0.9% saline, which does not induce irritation), and positive control (10% w/v KOH), which is known to irritate the eyes. Using a micropipette, 0.3 ml of the test sample was added to the CAM surface once the egg surface had been removed, ensuring that at least 50% of the CAM surface was covered. The reactions on the CAM surface were monitored for 300 seconds. The occurrence of each of the endpoints—coagulation, vascular lysis, and haemorrhage was timed and recorded in seconds. The following equation was used to determine the potential irritancy (PI) score based on the duration of time essential for the endpoints to develop [31]:

IS=

Where h: appearance time in seconds of haemorrhage, v: appearance time in seconds of vasoconstriction, c: appearance time in seconds of coagulation

Based on the irritation score, as shown in table 1, the result was analysed.

Table 1: Irritation score value with inference for HET-CAM Test

| Irritation score | Inference |

| 0-0.9 | No irritation |

| 1-4.9 | Weak irritation |

| 5-8.9 | Moderate irritation |

| 9-21 | Severe irritation |

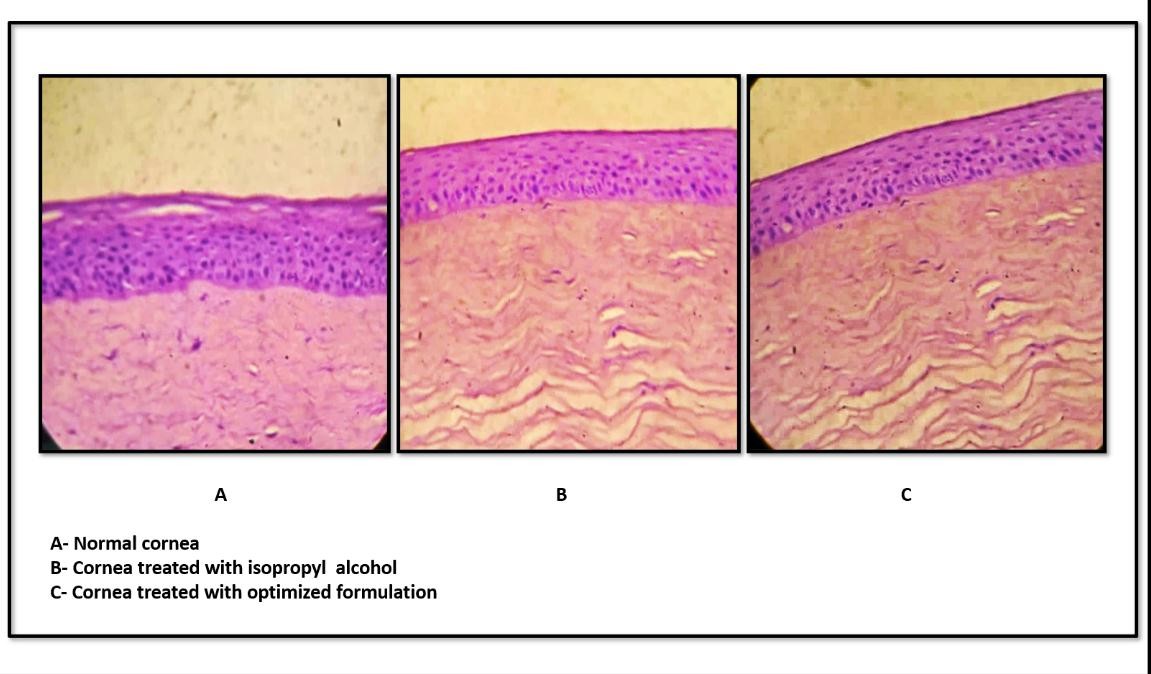

Histopathology studies

To evaluate potential corneal toxicity and ensure tissue compatibility, histopathological analysis was conducted using goat corneas. Fresh eyeballs were collected from a local slaughterhouse and transported under chilled conditions. After isolating and rinsing the cornea with normal saline, the tissues were incubated with the optimized formulation IGT, 0.9% NaCl (as a standard), and an untreated cornea (control) for 6 h. Post-incubation, tissues were sectioned (40 µm) using a cryotome, dehydrated through graded alcohols, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin [16]. The stained sections were then examined under a 40× magnification microscope to assess any structural changes or signs of irritation [25, 32].

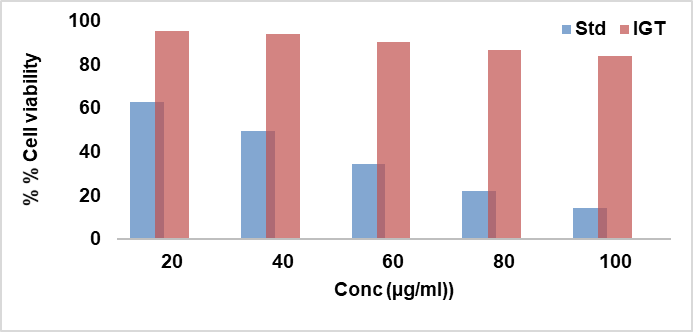

In vitro cytotoxicity study

The methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay was employed to assess human corneal epithelial cells (HCE-2; ATCC CRL-2706) viability after treatment with optimized formulation IGT. Cells were seeded in tissue-culture treated 96-well plates at 1×10⁴ cells/well in 100 µl** medium and allowed to adhere for 24 h. IGT (test sample) was added at 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/ml (n=3 wells per concentration). A standard (ethanol) comparator was run at the same concentrations in parallel. Vehicle control wells received 0.2% DMSO (v/v) in PBS. Plates were incubated for a further 24 h at 37 °C/5% CO₂. After treatment, the medium was removed, and 20 µl** MTT reagent (5 mg/ml in PBS) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C/5% CO₂ to allow formazan formation. Supernatants were discarded, 200 µl** DMSO was added to dissolve crystals (10 min, protected from light), and absorbance was recorded at 550 nm using a microplate reader. Percent cell viability was calculated as:

Percent inhibition = 100 − Viability.

Stability studies

The stability study was conducted by subjecting the optimised IGT formulation to different temperature conditions, including 4 °C±2 °C (refrigerator) and room temperature (25 °C±2 °C/60%±5% RH) for a duration of 1 mo. The Samples were withdrawn periodically (0, 15 and 30 d), and evaluated for vesicle size, viscosity, and drug content.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Formulation and characterization of LCZ-TFs

Statistical analysis of the design of experiments

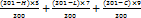

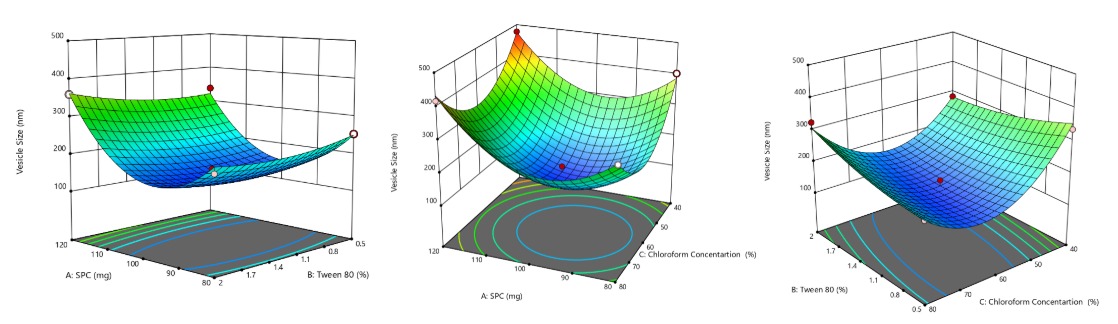

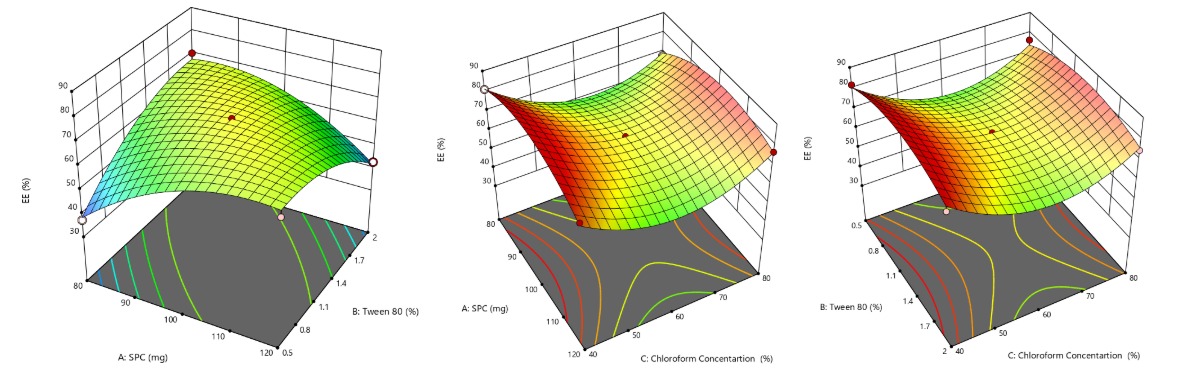

A box–behnken experimental design was employed to systematically explore the effect of three formulation variables, i. e., SPC, Tween 80, and chloroform, on critical quality attributes of Luliconazole-loaded transferosomes. Using the thin-film hydration technique, 14 distinct formulations were developed and assessed for vesicle size, PDI, zeta potential, and % EE. The detailed results for all 14 batches are presented in tables 2 and 3, and a visual representation of factor influences is provided in fig. 1 to 3.

Vesicle size

The mean vesicle size of LCZ-TFs formulations, as presented in tables 2 and 3, ranged from 123.7 to 477.16 nm, indicating successful development of nanometric vesicles across all 14 batches. An initial reduction in vesicle size was observed with increasing concentrations of soya phosphatidylcholine (SPC), attributed that, at lower concentrations, SPC promotes the formation of smaller, more uniform vesicles due to effective packing and bilayer formation[33]. However, beyond a certain concentration of SPC, a rise in size occurred. It may be that at higher concentrations of SPC, vesicles may begin to aggregate, leading to larger sizes. This is supported by findings that excess components can destabilize smaller vesicles, resulting in larger dispersed particles [29]. Tween 80 was also showing a similar way of response, i. e., at lower concentrations, which contributed to smaller vesicles, possibly due to its integration into the lipid bilayer via hydrogen bonding with the lecithin head group. However, at higher concentrations, Tween 80 appeared to disrupt membrane integrity, leading to an increase in vesicle size [33]. Statistical evaluation through regression analysis revealed a significant model with an F-value of 24.99. The model's robustness was supported by a high predicted R² of 0.7771 and an adjusted R² of 0.9432, suggesting strong predictive accuracy. The quadratic regression equation for vesicle size (Y) in terms of coded factors was:

Vesicle Size (Y) = 141.27+50.98A+4.71B – 27.97C+15.06AB+6.85AC+39.51BC+130.99A²+18.60B²+131.06C²

Where A, B, and C represent the coded values of SPC, Tween 80, and chloroform concentration, respectively. Positive coefficients indicate synergistic effects, while negative coefficients suggest antagonistic interactions. The 3D response surface plots (fig. 1) illustrate the interactive effects of these variables on vesicle size. These findings affirm that the formulation components notably influenced vesicle characteristics, with the regression model statistically validated (p<0.05), as summarised in table 3 and fig. 1.

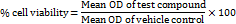

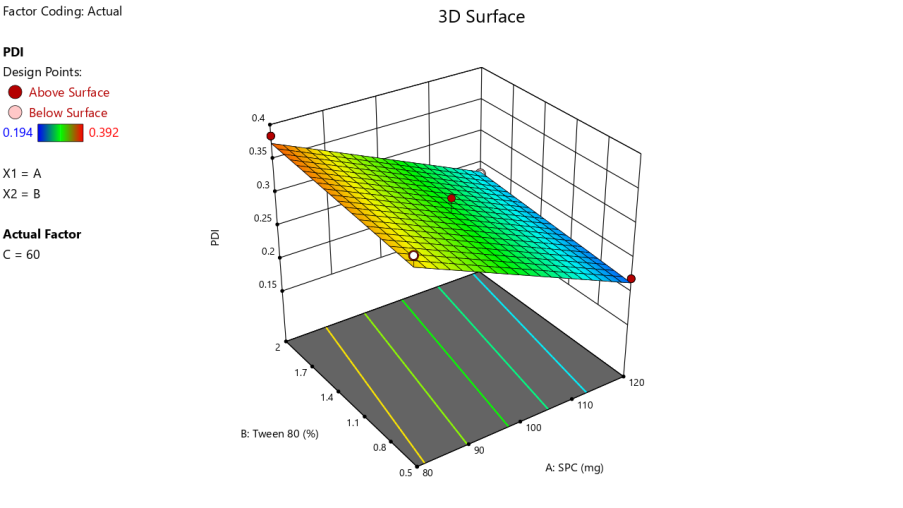

Polydispersity index (PDI)

The PDI values of LCZ-TFs formulations, as presented in tables 2 and 3, ranged from 0.194 to 0.392, indicating a uniform vesicle size distribution in all batches. A PDI below 0.5 reflects good homogeneity, essential for consistent drug release. A decrease in PDI was observed with increasing SPC concentration, suggesting improved vesicle uniformity. Tween 80 exhibited a consistent PDI-reducing effect, highlighting its stabilizing role [28]. Regression analysis confirmed the model's significance (F-value: 21.79), with a predicted R² of 0.7546 and an adjusted R² of 0.8275, validating model reliability. The regression equation derived was linear:

PDI = 0.2941 – 0.0685A+0.0109B+0.0559C

Where A, B, and C represent SPC, Tween 80, and chloroform concentrations. The response surface plot (fig. 2) demonstrates the individual and interactive effects of these variables on PDI.

Entrapment efficiency (EE)

Entrapment efficiency is a critical parameter that reflects the ability of the vesicular system to encapsulate and retain the active pharmaceutical ingredient within the carrier matrix. A higher entrapment efficiency indicates a better capacity of the formulation to deliver a sustained and controlled release of the drug, which is particularly important in ocular applications where drug bioavailability is inherently low. The entrapment efficiency of LCZ-TFs formulations, presented in table 2, ranged from 37.31 to 81.77%. Higher concentrations of SPC led to improved entrapment efficiency, likely due to the increased formation of transferosome vesicles with a larger core, which can accommodate more drug. Similarly, increasing surfactant concentration positively influenced entrapment efficiency, as higher surfactant levels enhanced vesicle formation, leading to higher drug encapsulation [34]. Statistical analysis confirmed the significance of the quadratic model (p<0.05), with an F-value of 29.03, indicating a strong influence of the independent variables on entrapment efficiency. The Predicted R² (0.7591) was in close agreement with the Adjusted R² (0.9510), affirming the model's reliability. The regression equation for entrapment efficiency is:

% EE = 70.45+0.7275A+0.9162B – 3.25C – 13.70AB+2.59AC+0.0225BC – 9.38A² – 7.39B²+15.11C²

Where A, B, and C represent SPC, Tween 80, and chloroform concentrations, respectively. Significant coefficients are denoted by an asterisk. The response surface plot (fig. 3.4) illustrates the effects and interactions of the variables on entrapment efficiency.

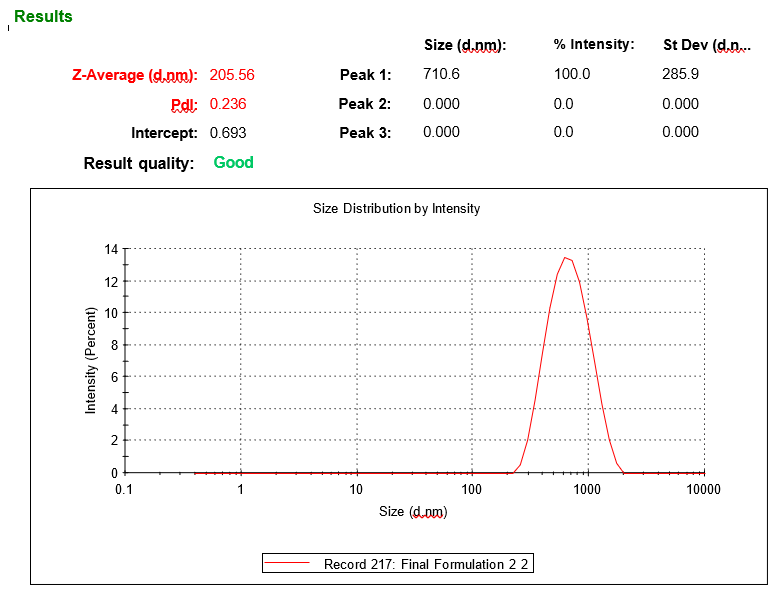

Optimization of LCZ-TFs

The optimization done according to every response, taking into consideration minimum particle size, PDI and maximum %EE. The solution given by the software containing 105.5 mg of soya lecithin, 1.08 % of tween 80 and 50.03 % of chloroform was utilized to prepare the optimized formula. The predicted value of vesicle size, PDI and %EE was found to be 211.5 nm, 0.246 and 75%, respectively, whereas the observed value is 205.5 nm, 0.236 shown in fig. 4, and 77.48%, with a percentage error of<±5% of the predicted value, which is acceptable. Bhujbal et al. (2021) reported similar results with tonabersat-loaded transferosomes (126.4 nm, PDI 0.16 %EE 80.98%), supporting that vesicle sizes around 100–300 nm with low PDI are ideal for ocular retention and minimal irritation and good corneal penetration [35]. Zeta potential of optimized formulation was found to be-53.9 mV as shown in fig. 5, indicating that the formulation is stable.

Table 2: Response parameters of luliconazole transferosome formulations based on box-behnken design

Form code |

Drug mg |

Factor | Response | ||||

| A. SPC mg | B tween 80 % | C chloroform conc % | Vesicle size±SD nm | PDI±SD | EE±SD % | ||

| F1 | 10 | 80 | 0.5 | 60 | 252.5±3.79 | 0.367±0.015 | 37.31± 2.67 |

| F2 | 10 | 120 | 0.5 | 60 | 338.2±5.07 | 0.221±0.009 | 64.52± 2.16 |

| F3 | 10 | 80 | 2 | 60 | 213.4±3.20 | 0.384±0.015 | 70.26± 1.82 |

| F4 | 10 | 120 | 2 | 60 | 359.3±5.39 | 0.233±0.009 | 42.65± 1.57 |

| F5 | 10 | 80 | 1.25 | 40 | 402.8±6.04 | 0.343±0.014 | 81.08± 3.46 |

| F6 | 10 | 120 | 1.25 | 40 | 477.2±7.16 | 0.194±0.008 | 79.01± 1.42 |

| F7 | 10 | 80 | 1.25 | 80 | 315.8±4.74 | 0.381±0.012 | 68.18± 2.23 |

| F8 | 10 | 120 | 1.25 | 80 | 417.6±6.26 | 0.279±0.011 | 76.47± 3.18 |

| F9 | 10 | 100 | 0.5 | 40 | 335.8±5.04 | 0.201±0.008 | 81.77± 2.47 |

| F10 | 10 | 100 | 2 | 40 | 284.6±4.27 | 0.215±0.009 | 79.85± 1.94 |

| F11 | 10 | 100 | 0.5 | 80 | 218.2±3.27 | 0.348±0.014 | 76.46± 3.28 |

| F12 | 10 | 100 | 2 | 80 | 325.1±4.88 | 0.392±0.013 | 74.63± 1.34 |

| F13 | 10 | 100 | 1.25 | 60 | 158.8±2.38 | 0.243±0.010 | 70.25± 2.51 |

| F14 | 10 | 100 | 1.25 | 60 | 123.7±1.86 | 0.316±0.013 | 70.65± 3.07 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD, (n=3)

Fig. 1: 3D response surface curve representing the effect of SPC, tween 80 and chloroform on vesicle size

Fig. 2: 3D response surface curve representing the effect of SPC, tween 80 and at 60% chloroform on PDI

Fig. 3: 3D response surface curve representing the effect of SPC, tween 80 and chloroform on % EE

Table 3: Summary of regression analysis and ANOVA

| S. No. | Factor | Vesicle size (Adjusted R2= 0.9432) | PDI (Adjusted R2 = 0.8275) | % EE (Adjusted R2 = 0.9510) | |||

| Estimated beta coefficient | ‘P’ value | Estimated beta coefficient | ‘P’ value | Estimated beta coefficient | ‘P’ value | ||

| Intercept | +141.27 | +0.2941 | <0.001 | +70.45 | 0.0027 | ||

| A-SPC | +50.98 | 0.0038 | -0.0685 | 0.3468 | +0.7275 | 0.531 | |

| B-Tween 80 | +4.71 | 0.6064 | +0.0109 | 0.0005 | +0.9162 | 0.436 | |

| C-Chloro Conc | -27.97 | 0.0296 | +0.0559 | - | -3.25 | 0.037 | |

| AB | +15.06 | 0.2759 | - | - | -13.70 | 0.0008 | |

| AC | +6.85 | 0.5968 | - | - | +2.59 | 0.1596 | |

| BC | +39.51 | 0.0297 | - | - | +0.0225 | 0.9888 | |

| A² | +130.99 | 0.0006 | - | - | -9.38 | 0.0050 | |

| B² | +18.60 | 0.2360 | - | - | -7.39 | 0.0117 | |

| C² | +131.06 | 0.0006 | - | - | +15.11 | 0.0008 | |

| Lack of Fit | 0.6310 | 0.9019 | 0.0599 | ||||

Fig. 4: Vesicle size analysis of optimzed LCZ-TEs by Zeta sizer

Fig. 5: Zeta potential of optimized LCZ TFs

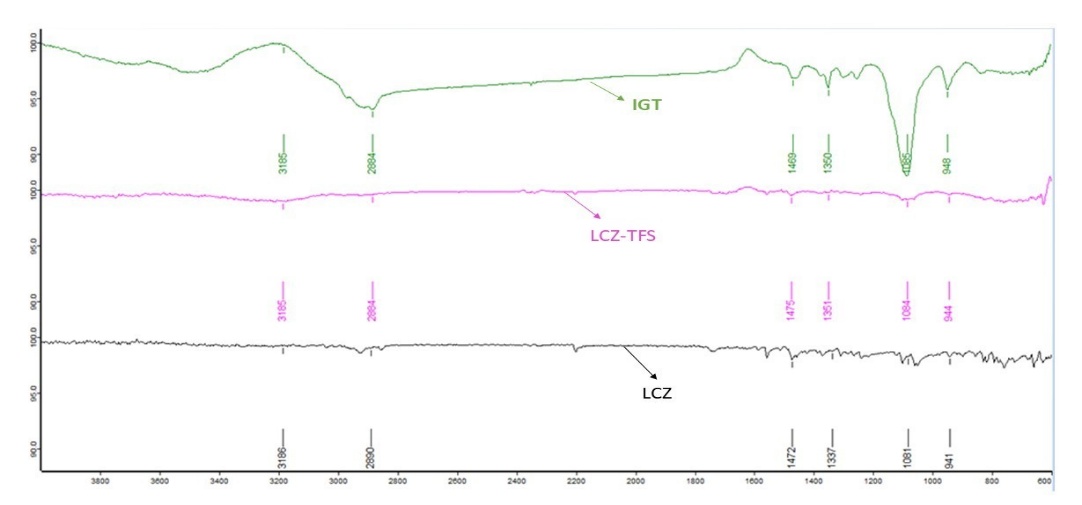

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) compatibility study

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to assess potential interactions between LCZ and the selected excipients. The FTIR spectra of pure LCZ exhibited characteristic absorption peaks at 3312.28, 2925.15, 2853.10, 1725.30, 1552.18, and 1041.22 cm⁻¹, corresponding to N-H (amine) stretching, C-H (alkane) stretching, C-H (alkane) stretching, C=O (carbonyl) stretching, C=C (aromatic) stretching, and C-O (ether) stretching functional groups. These peaks were carefully compared with those observed in the optimized formulation of LCZ-TFs and IGT, as shown in fig. 6. The spectra of the formulation LCZ-TFs and IGT retained all major characteristic peaks of LCZ without any significant shifts, broadening, or disappearance, indicating the absence of chemical interactions between the drug and excipients. Additionally, the excipient-specific peaks were also present and remained unaltered, further supporting the chemical compatibility of the components. These findings suggest that Luliconazole remained chemically stable throughout the formulation process. No evidence of drug degradation or formation of new peaks was observed. Therefore, the FTIR analysis confirms that there was no significant interaction between Luliconazole and the excipients used in the formulation, affirming the drug's compatibility and stability in the developed system.

Fig. 6: FTIR spectrum of LCZ, LCZ-TFS and IGT

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis

TEM was utilized to evaluate the surface morphology and structural integrity of the optimized LCZ-TFs. The TEM images (fig. 7) revealed that the vesicles were uniformly spherical in shape, with a smooth surface and clearly defined boundaries. The absence of aggregation or deformation among the vesicles indicates a stable and well-dispersed nano system. The vesicles exhibited a distinct core and lipid bilayer outline, confirming successful encapsulation of the drug within the phospholipid matrix. These morphological characteristics affirm the nano-structural integrity of the formulation and its potential suitability for ocular delivery, where uniformity, stability, and nanoscale size are critical for enhanced permeation and patient compliance.

Fig. 7: TEM images of optimised TFS vesicle

Formulation and characterisation of in situ gel of luliconazole-loaded transferosomes (IGT)

The optimized LCZ-TFs were incorporated into a thermosensitive IG using Pluronic F127 and Pluronic F68 to enhance ocular bioavailability and retention. An IGD with a pure drug was prepared for comparison. Both formulations were evaluated for general appearance, pH, gelling capacity, gelation temperature, viscosity, and drug content. The results are summarised in table 4.

General appearance

The IGT and IGD formulations were found to be off-white, translucent, and free from particulate matter. The in-situ gels exhibited pourable consistency at room temperature, which is desirable for ocular administration. The clarity and uniformity observed indicate good formulation stability and patient acceptability.

pH evaluation

The pH values for both formulations were measured at 7.3±0.1, which falls within the physiologically acceptable range for ocular application (6.8–7.4). Maintaining physiological pH ensures comfort and minimizes irritation upon instillation.

Gelling capacity and gelation temperature

The gel base consisted of Pluronic F127 (15% w/v) and Pluronic F68 (1% w/v), which remained in a liquid state at refrigerated temperatures and transformed into a gel at physiological temperatures (37–38 °C). Based on literature values indicating gelation at 28 °C for 20% Pluronic F127 and 74.7 °C for Pluronic F68, a 15:1 ratio was selected to achieve optimal gelation near body temperature [21, 36]. Both IGT and IGD formulations exhibited immediate gelation upon contact with simulated tear fluid (pH 7.4), showing a gelling grade of +++, indicative of strong and stable gel formation. The measured gelation temperatures were 32.8±0.4 °C for IGT and 34.5±0.5 °C for IGD, aligning well with ocular surface temperature (~34 °C), thus allowing ease of instillation and rapid in situ gelation. The incorporation of Pluronic polymers played a key role in enabling this thermosensitive behavior, thereby enhancing ocular retention.

Rheological properties

Viscosity measurements at 10 °C and 37 °C confirmed the thermo-responsive behaviour of the gels. At 37 °C, IGT exhibited a viscosity of 29.67±0.90 cP, slightly higher than IGD (27.86±1.43 cP), suggesting enhanced network density due to the presence of transferosomes. This increased viscosity supports prolonged ocular residence. At 10 °C, both gels maintained lower viscosities (14.1±0.72 cP for IGT and 12.3±0.85 cP for IGD), confirming ease of administration at ambient conditions.

Table 4: The result of general appearance, pH, gelling capacity, viscosity and drug content

| Evaluation parameters | Results | |

| IGD | IGT | |

| Appearance | Off white | Off white |

| pH | 7.3±0.1 | 7.3±0.1 |

| Gelling capacity | +++ | +++ |

| Gelation Temperature (Tg) | 34.5±0.5 | 32.8±0.4 |

| Drug content | 97.8±0.58 | 95.9±0.71 |

| Viscosity in cp | 10̀ °C | 12.3±0.85 |

| 37 °C | 27.86±1.43 | |

Data are expressed as mean±SD, (n=3), IGD= Conventional In situ gel contain pure drug, IGT== In Situ Gel of Luliconazole-loaded Transferosomes

Drug content

Drug content analysis revealed 95.9±0.71% for IGT and 97.8±0.58% for IGD, indicating uniform drug distribution within the gel matrices. The slightly reduced drug content in IGT could be attributed to drug encapsulation within lipid vesicles, which may influence release during assay. These findings confirm that the incorporation of transferosomes into the thermosensitive in situ gel system improves key physicochemical parameters critical for ocular drug delivery. The IGT formulation exhibited favourable characteristics such as physiological pH, efficient gelling behaviour, appropriate viscosity, and consistent drug loading, making it a promising system for enhancing the ocular bioavailability of Luliconazole.

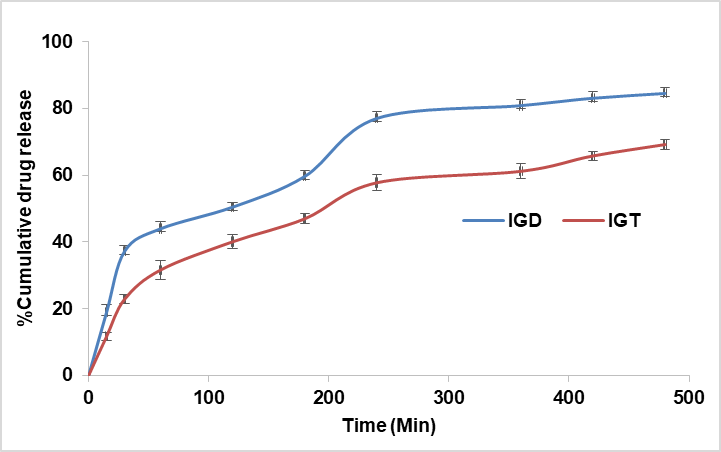

In vitro drug release study

The drug release behaviour of IGT and IGD was studied using a semi-permeable cellophane membrane in Franz diffusion cells. The release profile of IGT demonstrated a sustained and prolonged release of LCZ over 8 h compared to the conventional IGD formulation, as shown in fig. 8. Drug release data were fitted to various kinetic models to determine the mechanism of release. Both the in situ gels, i. e., IGT and IGD, followed Higuchi kinetics with the highest regression coefficient (R²=0.997 and 0.985), respectively, as shown in table 5. The best fit of the release data to the Higuchi model indicates that diffusion is the primary mechanism governing drug release from the transferosomal in situ gel. This is consistent with the structural characteristics of transferosomes, which possess a flexible lipid bilayer that acts as a semipermeable membrane, facilitating sustained and controlled diffusion of the encapsulated drug. Moreover, when incorporated into an in situ gel matrix, the overall release process becomes further modulated by the gel’s viscosity and mesh structure. However, the dominant release behaviour remains diffusion-driven due to the gradual migration of drug molecules from the lipid vesicles through the gel matrix to the external medium [37, 38].

Fig. 8: Comparative in vitro drug release study of different in situ gels

Table 5: Drug release kinetics of luliconazole-loaded in situ gel formulations

| Form. code | Kinetic model | ||||||||

| Zero order | First order | Higuchi model | Korsemayer-peppas model | ||||||

| R2 | K | R2 | K | R2 | k | R2 | k | n | |

| IDG | 0.957 | 0.140 | 0.981 | -0.001 | 0.985 | 0.035 | 0.972 | 0.140 | 0.705 |

| IGT | 0.989 | 0.120 | 0.991 | -0.009 | 0.997 | 0.037 | 0.984 | 0.023 | 0.680 |

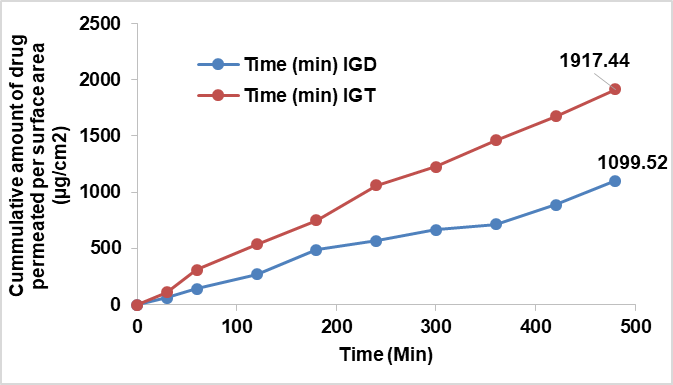

Ex vivo permeation study

As no marketed ophthalmic formulation of luliconazole is available, therefore, the ex vivo ocular permeability parameter of IGT was compared with that of IGD, and the results are shown in table 6. The ex vivo permeation study conducted using goat cornea demonstrated a significantly higher (p<0.001) cumulative drug permeation from the transferosomes in situ gel (IGT) (1917.44±2.78 µg/cm) compared to the plain in situ gel (IGD) (1099.52±4.07 µg/cm²) over 8 h. The enhanced permeation observed with IGT may be due to the presence of Tween 80 and ethanol. Tween 80, a non-ionic surfactant, serves as an effective edge activator in transferosome formulations. It enhances vesicle deformability by inserting itself into the phospholipid bilayer, disrupting lipid packing and thereby increasing membrane fluidity [39]. This improved flexibility enables transferosomes to traverse narrow intercellular spaces, such as those in the corneal epithelium, without compromising vesicle integrity. Additionally, Tween 80 reduces surface tension, preventing vesicle aggregation and promoting the stability of the ultra-deformable system. Ethanol disrupts the orderly packing of membrane lipids in the corneal epithelium, increasing membrane fluidity and permeability. It also induces a transient loosening of tight junctions by modifying tight junction protein structures, thereby facilitating paracellular drug transport. IGT showed higher steady-state flux and permeability coefficient, confirming improved trans corneal delivery. These findings support the effectiveness of transferosome-based gels in enhancing ocular drug permeation and sustaining drug release.

Fig. 9: Comparative ex vivo drug permeation study of different formulations in situ gels

Table 6: Permeated amount of LCZ at 480 min flux, and permeability coefficient

| Form code | Permeated amount at 480 min (µg/cm2) | Flux (µg/cm2 min) | Permeability constant (Kp) × 10-3(cm2/min) |

| IGD | 1099.52±4.07 | 2.291 | 0.229 |

| IGT | 1917.44±2.78 | 3.995 | 0.399 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD, (n=3)

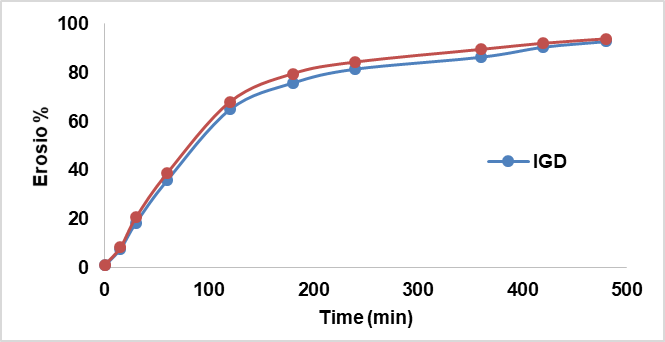

Erosion behaviour study

The erosion behaviour of the IGT and IGD was evaluated at 37±0.5 ° cover 8 h. Both formulations displayed a gradual and linear erosion pattern, reaching approximately 94% erosion at the end of the study. Although IGD showed in fig. 10, slightly faster erosion at earlier time points, the overall erosion profiles of IGT and IGD were comparable. This suggests that incorporation of transferosomes into the thermosensitive gel matrix did not significantly impact the gel's structural integrity. The observed erosion kinetics support a controlled and sustained drug release mechanism.

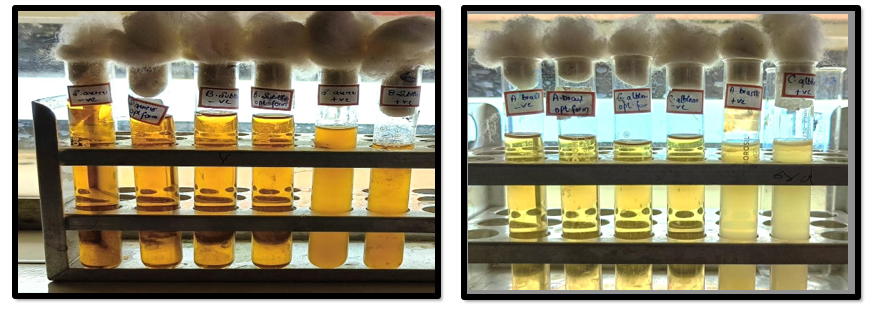

Sterility testing

The sterility of the optimized IGT formulation was confirmed using the direct inoculation method, as per pharmacopeial guidelines. Fluid thioglycolate and soya bean casein digest media were used to detect bacterial and fungal contamination, respectively. After seven days of incubation, no turbidity or microbial growth was observed in the test samples, while the positive controls showed visible contamination and the negative controls remained sterile. These findings, supported by fig. 11, indicate an effective aseptic formulation and the preservative efficacy of 0.01% benzalkonium chloride, confirming the microbiological safety of the IGT for ocular application.

Fig. 10: Erosion curve of different in situ gels

Fig. 11: Sterility test of IGT for bacteria and fungi

Table 7: Sterility test of optimised IGT

| Medium used | Microorganism | Positive control | Negative control | IGT |

| Fluid thioglycolate medium | S. aureus | + | - | - |

| E. choli | + | - | - | |

Soyabean-caseindigest medium |

C. albicans | + | - | - |

| A. brasiliensis | + | - | - |

Isotonicity test

The isotonicity of the optimized IGT formulation was confirmed by microscopic examination of RBCs following exposure. The RBCs retained their characteristic biconcave shape, with no signs of lysis, shrinkage, or swelling, comparable to the response observed with a marketed eye drop (fig. 12). This indicates that the formulation is isotonic and physiologically compatible, ensuring comfort and safety upon ocular administration.

Ocular irritation (HET-CAM) test

The HET-CAM test was performed to assess the ocular irritation potential of the optimized IGT formulation using chick embryo membranes, as shown in fig. 13. The irritation score for IGT (0.07) was comparable to the negative control (0.05, 0.9% NaCl), both of which showed no signs of irritation. In contrast, the positive control (1% SDS) exhibited severe irritation (mean score 13.45), confirming that the IGT formulation was non-irritant and safe for ocular application.

Fig. 12: Isotonicity test for (A). Normal RBC Cell (B) IGT at 100x

Fig. 13: HET-CAM test results

Ex vivo corneal histopathology study

Histological examination of goat corneas treated with the optimized IGT revealed intact epithelial layers, well-organised stromal architecture, and normal endothelium, with no signs of necrosis, inflammation, or edema, as shown in fig. 14. These findings were comparable to both untreated and standard-treated corneas, confirming that the IGT formulation is non-irritant and safe for ocular application. The results further corroborate the ocular biocompatibility observed in isotonicity and HET-CAM studies.

Fig. 14: Ex vivo corneal histopathology study

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity of various concentrations of IGT and standard (ethanol) on HCE-2cells was evaluated for 24 h by MTT assay. Percentage cell viability is plotted against concentration (µg/ml) as shown in fig. 15. The standard showed clear, concentration-dependent cytotoxicity toward HCE-2 cells, with percent inhibition increasing from 38.25% at 20 µg/ml to 86.09% at 100 µg/ml. The calculated IC₅₀ was 39.33 µg/ml, indicating moderate potency under these assay conditions. In contrast, IGT exhibited minimal cytotoxicity across 20–100 µg/ml. Inhibition rose modestly from 4.92% (20 µg/ml) to 16.86% (100 µg/ml), corresponding to 95.08–83.14% viability relative to vehicle control. An IC₅₀ was not estimable within the tested range (≤ 100 µg/ml). The MTT data demonstrate that, while the standard compound is cytotoxic to HCE-2 cells in a dose-dependent manner, IGT maintains high cell viability (≥ 83%) even at the highest tested concentration, supporting a favourable in vitro cytocompatibility profile for ocular applications within the tested concentration range [40].

Fig. 15: Dose–response cytotoxicity of IGT and standard compound on human corneal epithelial (HCE-2) cells, assessed by MTT assay after 24 h exposure

Table 8: Stability data of optimized IGT formulation

| Condition | Time in day | Apperance | Particle size (nm) | Drug content % | Vicosity at 37 °C cp |

| 4 °C±2 °C (Refrigerated | 0 | Off white | 210.4 | 95.9 | 29.67 |

| 15 | Off white | 210.9 | 95.1 | 29.04 | |

| 30 | Off white | 213.1 | 94.3 | 28.23 | |

25 °C±2 °C /60%±5% RH |

0 | Off white | 210.4 | 95.9 | 29.67 |

| 15 | Off white | 212.3 | 94.2 | 28.12 | |

| 30 | Off white | 217.5 | 92.6 | 27.23 |

Stability studies

The stability study was conducted for the optimized IGT formulation, and the results are shown in table 8. The formulation remained physically stable without any signs of phase separation or turbidity. There were only minimal changes observed in vesicle size, viscosity and drug content, all of which remained within acceptable pharmacopeial limits, confirming that the formulation was stable under both storage conditions.

Scalability and production considerations

From an industrial translation perspective, scaling up the production of the developed transferosomal in situ gel poses several practical challenges. When scaling up, conventional batch preparation techniques may result in differences in the distribution of vesicle sizes and the effectiveness of drug encapsulation. The production of vesicles with consistent size and composition can be done continuously by using emerging technologies like microfluidics, which provide precise control over mixing parameters. This approach improves reproducibility, reduces operator variability, and is easily adjustable to good manufacturing practice (GMP) settings. Complementary approaches, including high-pressure homogenization for uniform particle size reduction and tangential flow filtration for scalable purification, can be integrated into production pipelines. By implementing these continuous, scalable processes, the drawbacks of conventional approaches can be addressed, enabling a smooth transition from bench-scale research to commercial manufacturing.

CONCLUSION

A novel luliconazole-loaded transferosomes in situ gel was successfully developed to enhance ocular permeability and retention for the treatment of fungal keratitis. The optimized formulation demonstrated favourable physicochemical characteristics, including nanosized vesicles, high entrapment efficiency, and ideal gelling properties suitable for ocular application. In vitro and ex vivo studies confirmed sustained drug release, enhanced corneal permeation, and diffusion-controlled kinetics. The IGT showed excellent ocular compatibility with no signs of irritation or tissue damage, as evidenced by HET-CAM, isotonicity, and histopathological evaluations. Overall, the developed IGT offers a promising, safe, and effective alternative for ocular delivery of luliconazole in managing fungal keratitis. For advancing the formulation toward clinical application, future in vivo studies should be conducted using suitable animal models, such as rabbits, to evaluate ocular safety, therapeutic efficacy, and pharmacokinetic behaviour in a living system.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

M. Divyanand: Concept, Literature Search, Materials and Design, Data Collection, Processing, Analysis and/or Interpretation, Writing; Sneh Priya: Concept, Resources, Materials, Design, Supervision, Analysis and/or Interpretation, Writing, Critical Reviews; Melanie Ashel Dsouza: Data Collection, Processing, Analysis and/or Interpretation; Murari Upadhyay: Interpretation, Writing, Critical Reviews.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Raj N, Vanathi M, Ahmed NH, Gupta N, Lomi N, Tandon R. Recent perspectives in the management of fungal keratitis. J Fungi (Basel). 2021 Oct 26;7(11):907. doi: 10.3390/jof7110907, PMID 34829196, PMCID PMC8621027.

Cabrera Aguas M, Khoo P, Watson SL. Infectious keratitis: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022 Jul;50(5):543-62. doi: 10.1111/ceo.14113, PMID 35610943.

Awad R, Ghaith AA, Awad K, Mamdouh Saad M, Elmassry AA. Fungal keratitis: diagnosis management and recent advances. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024 Jan 10;18:85-106. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S447138, PMID 38223815, PMCID PMC10788054.

Hoffman JJ, Burton MJ, Leck A. Mycotic keratitis a global threat from the filamentous fungi. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7(4):273. doi: 10.3390/jof7040273, PMID 33916767.

Yang J, Liang Z, Lu P, Song F, Zhang Z, Zhou T. Development of a luliconazole nanoemulsion as a prospective ophthalmic delivery system for the treatment of fungal keratitis: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(10):2052. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14102052, PMID 36297487.

Mahmood A, Rapalli VK, Waghule T, Gorantla S, Singhvi G. Luliconazole-loaded lyotropic liquid crystalline nanoparticles for topical delivery: QbD-driven optimization in vitro characterization and dermatokinetic assessment. Chem Phys Lipids. 2021 Jan 1;234:105028. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2020.105028, PMID 33309940.

Bachu RD, Chowdhury P, Al Saedi ZH, Karla PK, Boddu SH. Ocular drug delivery barriers role of nanocarriers in the treatment of anterior segment ocular diseases. Pharmaceutics. 2018 Feb 27;10(1):28. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10010028, PMID 29495528.

Shahab MS, Rizwanullah M, Alshehri S, Imam SS. Optimization to development of chitosan decorated polycaprolactone nanoparticles for improved ocular delivery of dorzolamide: in vitro ex vivo and toxicity assessments. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;163:2392-404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.185, PMID 32979440.

Mascarenhas M, Chaudhari P, Lewis SA. Natamycin ocular delivery: challenges and advancements in ocular therapeutics. Adv Ther. 2023 Aug;40(8):3332-59. doi: 10.1007/s12325-023-02541-x, PMID 37289410.

Khames A, Khaleel MA, El Badawy MF, El Nezhawy AO. Natamycin solid lipid nanoparticles sustained ocular delivery system of higher corneal penetration against deep fungal keratitis: preparation and optimization. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:2515-31. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S190502, PMID 31040672.

Tan G, Yu S, Pan H, Li J, Liu D, Yuan K. Bioadhesive chitosan-loaded liposomes: a more efficient and higher permeable ocular delivery platform for timolol maleate. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017 Jan 1;94(A):355-63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.10.035, PMID 27760378.

El Sayed MM, Hussein AK, Sarhan HA, Mansour HF. Flurbiprofen loaded niosomes in gel system improves the ocular bioavailability of flurbiprofen in the aqueous humor. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2017 Jun 3;43(6):902-10. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2016.1272120, PMID 27977311.

Janga KY, Tatke A, Dudhipala N, Balguri SP, Ibrahim MM, Maria DN. Gellan gum-based sol-to-gel transforming system of natamycin transfersomes improves topical ocular delivery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019 Sep 1;370(3):814-22. doi: 10.1124/jpet.119.256446, PMID 30872389.

Gupta R, Kumar A. Transfersomes: the ultra-deformable carrier system for non-invasive delivery of drug. Curr Drug Deliv. 2021 May 1;18(4):408-20. doi: 10.2174/1567201817666200804105416, PMID 32753015.

Batur E, Ozdemir S, Durgun ME, Ozsoy Y. Vesicular drug delivery systems: promising approaches in ocular drug delivery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024 Apr 16;17(4):511. doi: 10.3390/ph17040511, PMID 38675470.

Noreen S, Ghumman SA, Batool F, Ijaz B, Basharat M, Noureen S. Terminalia arjuna gum/alginate in situ gel system with prolonged retention time for ophthalmic drug delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020 Jun 1;152:1056-67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.193, PMID 31751751.

Uwaezuoke O, Du Toit LC, Kumar P, Ally N, Choonara YE. Linoleic acid-based transferosomes for topical ocular delivery of cyclosporine a. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Aug;14(8):1695. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14081695, PMID 36015321.

Abdallah MH, Abu Lila AS, Shawky SM, Almansour K, Alshammari F, Khafagy ES. Experimental design and optimization of nano-transfersomal gel to enhance the hypoglycemic activity of silymarin. Polymers. 2022 Jan 27;14(3):508. doi: 10.3390/polym14030508, PMID 35160498.

Pratiksha NP, Priya S, Sanjana KPS, Khandige PS. Transethosomes for enhanced transdermal delivery of methotrexate against rheumatoid arthritis: formulation optimisation and characterisation. Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(6):122-32. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i6.51772.

Lou J, Hu W, Tian R, Zhang H, Jia Y, Zhang J. Optimization and evaluation of a thermoresponsive ophthalmic in situ gel containing curcumin-loaded albumin nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014 May 21;9:2517-25. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S60270, PMID 24904211.

Al Khateb K, Ozhmukhametova EK, Mussin MN, Seilkhanov SK, Rakhypbekov TK, Lau WM. In situ gelling systems based on pluronic F127/Pluronic F68 formulations for ocular drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2016 Apr 11;502(1-2):70-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.02.027, PMID 26899977.

Vijayashree R, Priya S, Jyothi D, James JP. Formulation and characterisation of gastroretentive in situ gel loaded with Glycyrrhiza glabra L. extract for gastric ulcer. Int J Appl Pharm. 2024 Mar;16(2):76-85. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i2.49033.

M SS, Priya S, Maxwell AM. Formulation and evaluation of novel in situ gel of lafutidine for gastroretentive drug delivery. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11(8):88-94. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i8.25582.

Bachhav HD, Savkare AN, Karmarkar RI, Derle DI. Development of poloxamer based thermosensitive in situ ocular gel of betaxolol hydrochloride. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(6):287-91.

Kandpal N, Dhuliya R, Padiyar N, Singh A, Khaudiyal S, Ale Y. Innovative niosomal in-situ gel: elevating ocular drug delivery synergies. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2024;14(9):001-17. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2024.191581.

Mohammed MI, Makky AM, Abdellatif MM. Formulation and characterization of ethosomes bearing vancomycin hydrochloride for transdermal delivery. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014 Nov 1;6(11):190-4.

Sampathi S, Maddukuri S, Ramavath R, Dodoala S, Kuchana V. Modified cyclodextrin based thermosensitive in situ gel for voriconazole ocular delivery against fungal keratitis. Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(1):150-60. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i1.48817.

Mahajan A, Patel P, Kareliya N. Ophthalmic pH triggered in situ gelling system of tobramycin: formulation and optimization using factorial design. Int J Pharm Investig. 2020 Apr 1;10(2):151-5. doi: 10.5530/ijpi.2020.2.28.

Singh MA, Dev DH. Acacia catachu gum in situ forming gels with prolonged retention time for ocular drug delivery. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022;15(9):33-40. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022.v15i9.45269.

Protocol IC. ICCVAM-recommended test method protocol: Hen’s egg test chorioallantoic membrane (HET-CAM) test method. NIH Publ. 2010;13:B30-8.

Khin SY, Soe HM, Chansriniyom C, Pornputtapong N, Asasutjarit R, Loftsson T. Development of fenofibrate/randomly methylated β-cyclodextrin loaded Eudragit® RL 100 nanoparticles for ocular delivery. Molecules. 2022 Jul 25;27(15):4755. doi: 10.3390/molecules27154755, PMID 35897940.

Furukawa M, Sakakibara T, Itoh K, Kawamura K, Sasaki S, Matsuura M. Histopathological evaluation of the ocular irritation potential of shampoos make-up removers and cleansing foams in the bovine corneal opacity and permeability assay. J Toxicol Pathol. 2015;28(4):243-8. doi: 10.1293/tox.2015-0022, PMID 26538816.

Song F, Yang G, Wang Y, Tian S. Effect of phospholipids on membrane characteristics and storage stability of liposomes. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2022 Oct 1;81:103155. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2022.103155.

Zubaydah WO, Andriani R, Suryani S, Indalifiani A, Jannah SR, Hidayati D. Optimization of soya phosphatidylcholine and Tween 80 as a preparation of diclofenac sodium transfersome vesicles using design-expert. JFG. 2023;9(1):84-98. doi: 10.22487/j24428744.2023.v9.i1.16085.

Bhujbal S, Rupenthal ID, Agarwal P. Formulation and characterization of transfersomes for ocular delivery of tonabersat. Pharm Dev Technol. 2025 May 15;30(5):558-71. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2025.2501991.

Mazyed EA, Abdelaziz AE. Fabrication of transgelosomes for enhancing the ocular delivery of acetazolamide: statistical optimization in vitro characterization and in vivo study. Pharmaceutics. 2020 May 20;12(5):465. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12050465, PMID 32443679.

Eleraky NE, El Badry M, Omar MM, El Koussi WM, Mohamed NG, Abdel Lateef MA. Curcumin transferosome loaded thermosensitive intranasal in situ gel as prospective antiviral therapy for SARS-CoV-2. Int J Nanomedicine. 2023;18:5831-69. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S423251, PMID 37869062.

Kharwade R, Ali N, Gangane P, Pawar K, More S, Iqbal M. DOE-assisted formulation optimization and characterization of tioconazole loaded transferosomal hydrogel for the effective treatment of atopic dermatitis: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Gels. 2023 Apr 4;9(4):303. doi: 10.3390/gels9040303, PMID 37102915.

Reddy YD, Sravani AB, Ravisankar V, Prakash PR, Reddy YS, Bhaskar NV. Transferosomes: a novel vesicular carrier for transdermal drug delivery system. J Innov Pharm Biol Sci. 2015;2(2):193-208.

Wroblewska K, Kucinska M, Murias M, Lulek J. Characterization of new eye drops with choline salicylate and assessment of their irritancy by in vitro short time exposure tests. Saudi Pharm J. 2015 Sep 1;23(4):407-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2014.11.009, PMID 27134543.