Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 120-129Reviewl Article

REGULATORY RELIANCE PATHWAYS: OPPORTUNITIES, CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

GURRAM GNANESHWARI, KIRAN NAGARAJ, SHAILEE DEWAN, VIGNESH MANOHARAN, PRADEEP MANOHAR MURAGUNDI*

Department of Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs and Management, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India

*Corresponding author: Pradeep Manohar Muragundi; *Email: pradeep.mm@manipal.edu

Received: 12 Jul 2025, Revised and Accepted: 21 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

Regulatory reliance allows national agencies to use assessments from trusted regulators instead of repeating the same work. This accelerates approvals, decreases workload, and allows patients to receive safe and effective medications more quickly. Many countries use different forms of reliance procedures, such as work-sharing, mutual recognition, abridged, and verification. These methods are common in regions like the European Union, the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Latin America. Various programs like Project Orbis and The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Collaborative Registration Procedure have reduced review times through collaboration between countries, thereby minimizing resource use and enabling work-sharing. Project Orbis and the Access Consortium have shown the importance of collaborative efforts and their essentiality when dealing with life-threatening diseases. Numerous countries in the Middle East and Asia have used these reliance methods to streamline regulatory processes particularly in public health emergencies. In South African countries, the impact is a 68% reduction in time with regulatory reliance as compared to regular processes. Additionally, the reliance guidelines of WHO initiated the UK’s International Recognition Procedure. During the COVID-19 pandemic regulatory reliance played a pivotal role and facilitated rapid vaccination approvals through international collaboration. Some challenges exist, such as unclear legislation, concerns about independence and legal limitations. Future research should focus on standardizing legislation, modernizing technology like the use of AI-driven evaluations, and improving collaboration as they help to strengthen global coordination to respond to emergencies more promptly. This article explains the reliance pathway and how regulatory decisions from trusted agencies help low-and middle-income countries.

Keywords: Reliance, National regulatory authorities, Low and middle income countries, Orbis and the access consortium

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55010 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

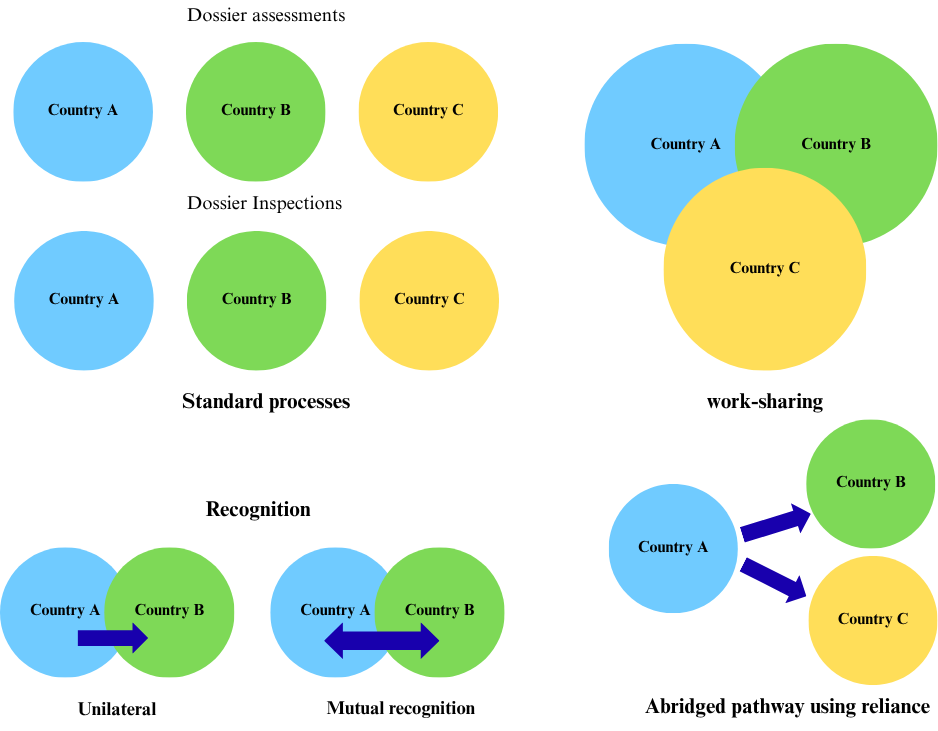

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines Regulatory reliance as “The act whereby the National Regulatory Authority (NRA) in one jurisdiction may take into account and give significant weight to assessments performed by another national regulatory authority or trusted institution, or to any other authoritative information in reaching its own decision. The relying authority remains independent, responsible, and accountable regarding the decisions taken, even when it relies on the decisions and information of others”. Many NRAs are using reliance to use resources better, improve decision-making, and speed up access. This approach reduces duplication, saves time as well as money, and strengthens regulatory oversight [1, 2]. However, many low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) struggle to conduct independent regulatory reviews. Around 70% lack sufficient resources, infrastructure, and trained staff, delaying access to essential medicines and weakening oversight. Based on WHO benchmarking data, only 12% of assessed countries-most of them had fully implemented essential regulatory preparedness indicators, indicating that nearly 70–88% of LMICs lack the capacity for full independent regulatory review [3]. With such struggle, LMICs have reduced the approval times by 50% through reliance pathways, like in South African countries, where the impact is more due to a reduction in time for the process as compared to regular process methods. They should provide clear documentation and make processes simple so that the agencies relying on them do not face unnecessary delays. This approach helps to balance efficiency with accountability, ensuring that reliance remains a trusted and effective regulatory tool [1]. Reliance can also help regulators increase productivity, encourage learning, and establish a more stable medication approval system [4]. Fig. 1 illustrates the major categories of reliance mechanisms, including recognition, work-sharing, and verification [2]. One method that NRAs use is to collaborate through work-sharing, which involves clinical trial supervision, safety monitoring, inspections, quality testing, and medication approvals [3]. Together, regulators can increase effectiveness while upholding strict guidelines for the quality and safety of products. Reliance can be applied at any stage of a product’s life cycle, from initial approval to post-market changes, ensuring timely access to medicines without compromising oversight. The implementation of global reliance has been slow despite its apparent benefits, primarily because of legal constraints, regulatory framework disparities, and worries about national sovereignty. In the context of Post Approval Changes (PAC), the idea of reliance is beneficial since it makes possible to examine changes more quickly once they have previously been evaluated by a reliable source. This guarantees uniform quality of service for patients in various locations while also expediting the approval process [5].

Reliance pathways are available to all regulators, regardless of background or resources. The difference between high-and low-income nations is evident, though. Due to a lack of personnel, resources, and training, many low-income nations find it difficult to perform essential duties, whereas high-income countries have stronger systems and well-trained experts. Applying quality management principles is another challenge, especially without enough funding. The speed and the efficiency of the review and approval of medicines and medical products are impacted by these gaps [2, 6]. Collaborative programs like Project Orbis, launched by the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) in 2019 [7].

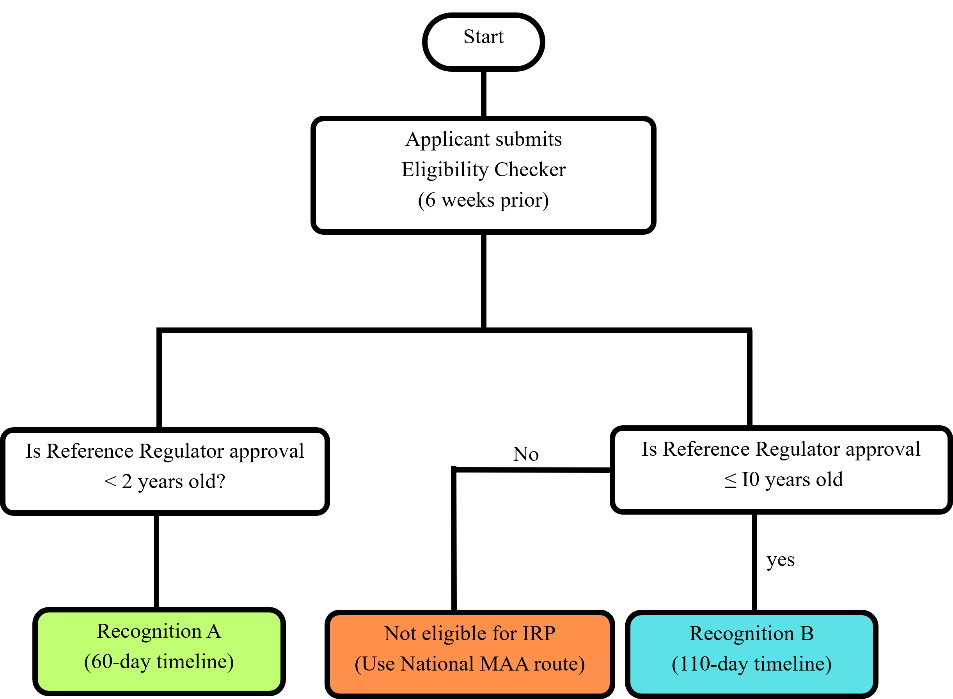

The Access consortium, formed in 2007 and expanded in 2020, supports joint reviews for new drugs, biosimilars, and generics [8]. Since its introduction in 2021, the UK's International Recognition Procedure (IRP) has allowed the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to acknowledge approvals from a number of significant regulators [9]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) takes part in three key regulatory reliance pathways designed to help non-EU countries benefit from its assessments: the European Union (EU) Medicines for All, the WHO collaborative registration, and the recently launched OPEN initiative [10]. These pathways help bring medicines to patients faster while keeping safety standards high [6, 10]. Options to support high-quality regulatory decisions–emphasizing reliance are depicted in fig. 2 [11].

Fig. 1: Types of reliance

Fig. 2: Options to support high-quality regulatory decisions–emphasizing reliance

Though reliance pathways have seen greater uptake in Latin America and the Caribbean, the implementation is uneven and not necessarily aligned with global best practices [10]. These complex developments call for clearer frameworks and more consistent forms of capacity-building support, particularly in LMICs, where regulatory systems can be resource-challenged. Drawing upon worldwide experiences, such as the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic, the article offers insight into ways to utilize reliance mechanisms purposely to promote regulatory oversight and improve access to medicines and health technology. It also looks at international efforts to harmonize post-approval reliance processes and the role of organizations such as WHO and International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) in promoting effective reliance models over time. This article explains the significance, effective products, especially for serious conditions with limited treatment options [1, 2].

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted through databases like PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, along with official resources like WHO, IRIS, and regulatory agency websites like those of the FDA, EMA, and MHRA. Search keywords were combinations of "regulatory reliance," "work-sharing," "mutual recognition," "Project Orbis," "Access Consortium," "Collaborative Registration Procedure," and "pharmaceutical regulation." The literature search was limited to publications, guidance documents, and reports published between 2015 and 2024 in order to capture the most recent innovations and trends related to regulatory reliance models globally. Peer-reviewed and grey literature were both included. Publications only in English were included. Editorials, commentaries, or pieces of opinion and irrelevant content articles were excluded.

Types of reliance

One of the primary types of regulatory reliance pathways is the abridged regulatory pathways that speed up approvals by allowing one regulatory authority to rely on decisions made by another trusted agency, keeping safety and quality standards intact in a timely manner. Recognition happens when a regulator fully accepts another agency’s decision, which can be one-sided or formalized through a mutual agreement. While the work-sharing allows multiple regulators to collaborate on tasks like clinical trial approvals, inspections, and post-market monitoring, reducing duplication. Joint assessments and inspections are examples where agencies review data together to improve efficiency [12]. The other type is the Verification model that permits the importation and local marketing of specific goods after one or more reputable reference organizations have approved them. The primary duty of the importing country's agency is to "verify" that the product meant for local sale has been registered adequately as stated in the application and that the product information for local marketing matches those specified in the reference authorization(s). Equivalence means two highly similar regulatory systems, based on shared standards, guidelines, and joint experiences, leading to consistent oversight and control [11].

Importance of reliance in pharmaceutical industry

Reliance can speed up assessments and cut down on duplication, but it needs to be used cautiously to maintain public confidence. A balanced approach guarantees that choices remain rigorous and objective by permitting independent scrutiny in addition to reliance. The objective is to encourage teamwork in assessments rather than to establish a single point of view. With global regulatory resources available, reliance can help agencies work more efficiently while keeping high standards. However, it should not replace independent evaluation wherever needed. The right balance ensures faster approvals without lowering safety or quality [13].

The increasing supply chains, market globalization, the quick advancement of research, and emergency management are just a few of the many challenges that regulators around the world must deal with. Moreover, the limited financial and human resources must be used to coordinate worldwide regulatory supervision. Thus, it is the responsibility of the international regulatory community to make the best use of these limited resources, prevent duplication, and focus resources and efforts where they are most needed [13]. Reliance is a potent pathway for putting the fundamental good regulatory practices of information sharing and efficiency promotion into effect. National regulators can focus on value-added operations that cannot be handled by others, like vigilance, market monitoring, and supervision of local manufacture and distribution, while utilizing the efforts of other regulatory bodies whenever feasible.

Strong regulatory systems take a lot of resources to establish and operate, including highly qualified personnel and a large financial commitment. In the modern world, Reliance provides a more efficient method of regulating medical products and a more intelligent approach to regulatory monitoring. Access to safe, efficient, and high-quality medical products is facilitated and accelerated, which benefits national governments, industry, international development partners, donors, patients and consumers. Reliance can also enhance regulatory response and preparedness; this proves especially during a public health emergency [6].

Collaborative programs across the globe

Access consortium

The access consortium was formed by a group of regulatory agencies from Australia, Canada, Singapore, and Switzerland (ACSS). The UK MHRA joined in 2020, expanding work-sharing efforts. The consortium reduces duplication, aligns regulations, and speeds up patient access to safe and effective medicines. It has working groups focused on New Actives, Generics, Biosimilars, Advanced Therapies, and Clinical Trials. Key initiatives include the New Active Substance Work Sharing Initiative (NASWSI), Biosimilar Work Sharing Initiative, and Generic Work Sharing Initiative. The COVID-19 pandemic increased the need for faster global access to medicines through collaboration. The Access Consortium is one such effort, helping regulators work together to speed up approvals while maintaining safety and quality standards [14, 15].

The case study of baloxavirmarboxil (xofluza) shows how the ACSS work-sharing initiative helps speed up its approval. Xofluza, an antiviral drug used for the treatment of influenza, went through this process to make regulatory review faster. Canada reviewed Module 3 of Xofluza, Switzerland reviewed Module 4, and Australia reviewed Module 5, showcasing how collaborative regulatory efforts can expedite the review process, leading to its approval in February 2020, reduced the overall review time by approximately 40% compared to traditional independent reviews making the process more efficient [16].

Another Pathway, launched in December 2023, the Promise Pilot Pathway provides priority review for unmet medical needs, cutting assessment time from 225 to 180 d. Eligible drugs must treat serious conditions with no alternative. Work-sharing enables agencies divide assessments while keeping independent decisions, example is the COVID-19 Working Group, created in 2020, that speeded up the vaccine approvals. Work-sharing can be resource-intensive, but it ensures timelines approvals for several markets. The Promise Pilot Pathway strengthens regulatory alignment, helping patients get critical medicines sooner [15].

Project orbis

Project Orbis is a program started by the U. S. FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE) in May 2019 to speed up the approval of cancer drugs worldwide. Table 1 depicts the types of Project Orbis and the comparison of submission timelines [17]. It lets multiple countries review new treatments at the same time, cutting down delays in different regions. The first review included the U. S. FDA, Australia’s TGA, and Health Canada. Other countries have since joined, including Brazil (ANVISA), Great Britain (MHRA), Israel (Ministry of Health), Singapore (HSA), and Switzerland (Swissmedic) [18].

Type A (Regular Orbis) involves submissions to Project Orbis partner agencies within 30 d of the original FDA submission. This category allows the greatest degree of collaboration throughout the review process, including shared review documents, discussion between regulatory agencies, and shared clarification requests. Type A facilitates near-simultaneous review and fosters strong alignment between international regulators. Type B (Modified Orbis) applies when submissions to Orbis partners occur more than 30 d after submission to the FDA [17]. While the collaboration is less intensive than in Type A, it still permits the sharing of FDA review reports, some participation in clarification exchanges, and involvement in select multi-country meetings. There may be opportunities for concurrent or overlapping review, though not to the same extent as Type A. Type C (Written Report Only Orbis) is the least collaborative model and is used when the FDA has issued its positive decision and completed its review and when Orbis partners start their review. The FDA shares its final review documents with the participating agencies, but there will not be a concurrent review, and the agencies will not be working in a collaborative manner during the review process. This type is meant to enable independent decision-making with reference to the FDA’s conclusions. Project Orbis helps new cancer drugs reach patients sooner [10, 19].

Table 1: Comparison of submission timelines for orbis types

| Orbis type | Submission timeline | Submission overlaps with FDA | Sharing of FDA reviews | Multi-country review meetings (POP TCONs) | Reference |

| Type A | Application submission to Project Orbis partners ≤ 1 mo of FDA submission | Expected | Yes | Yes | [10, 17] |

| Type B | Application submission to Project Orbis partners>1 mo of FDA submission | Expected | Yes | Yes | [10, 17] |

| Type C | Any time after FDA submission | Permitted | Yes | No | [10, 17] |

WHO

The WHO Reliance Guidelines emphasize using reliance as a regulatory approach to improve drug approvals, especially in countries with limited resources. Reliance allows NRAs to utilize the scientific evaluations, inspections, and assessments from Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRAs) while still maintaining independent decision-making. This method, a core principle of WHO Good Reliance Practices (GRP), helps reduce duplication of efforts, optimize resources, and speed up patient access to quality-assured medicines [20].

In 2015, WHO introduced the Collaborative Registration Procedure (CRP), which helps put reliance into practice. By giving NRAs access to SRAs complete scientific evaluations, inspection reports, and regulatory dossiers, the CRP greatly reduces review times, ensuring quicker patient access, receive necessary medicines faster. The CRP has proven particularly helpful in LMICs, where delays are frequently caused by a lack of regulatory capacity. Particularly for essential medications that are used to treat HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, contraception, and haemophilia. Till date the CRP has facilitated 59 regulatory approvals in 23 countries.

To enhance the effectiveness of the CRP and WHO’s reliance on improving initiatives, several steps are needed. First, the WHO should focus on increasing participation from both NRAs and pharmaceutical companies to ensure more stakeholders benefit from reliance-based approvals. Second, clear guidelines should be set for managing post-approval changes to maintain consistent regulatory oversight for CRP-approved medicines. Third, real-time communication platforms like WHO’s Med Net should be further developed to improve information sharing between NRAs, SRAs, and applicants.

Additionally, NRAs must show a stronger commitment to adhering to set procedural timelines to reduce unpredictability and inefficiencies in the approval process. By making these adjustments, the WHO can strengthen the CRP and reliance initiatives, making the regulatory process more efficient and accelerating access to critical medicines worldwide [21].

Regulatory reliance enables NRAs, especially LMICs, to leverage assessments conducted by more established agencies, reducing duplication and accelerating approvals. The study found that non-reference NRAs relied entirely on this approach, while reference NRAs used reliance in 40% of cases. With a median authorization review period of only 15 d, both the independent and reliant pathways were able to obtain approvals quickly.

Even though they weren't necessary for quick approval, dependence channels were crucial in enabling a prompt response. The study highlights the need for clearer and more transparent dependency paths, especially for NRAs with limited funding. It also stresses that the approval of new medications in LMICs and future health emergencies can benefit from the lessons learned from the COVID-19 vaccination authorizations. For medicines to be approved more quickly and effectively around the globe, it will be essential to strengthen reliance mechanisms and harmonize global regulatory systems [22].

Reliance pathway across nations

United Kingdom

The IRP was introduced by the UK’s MHRA to streamline the evaluation of Marketing Authorization Applications (MAAs). Effective from 1 January 2024, the IRP replaces earlier reliance procedures like the European Commission Decision Reliance Procedure (ECDRP) and Mutual Recognition Decentralised Reliance Procedure (MRDCRP). The MHRA was able to issue a UK Marketing Authorisation (UKMA) through these processes, which were effectively post-Brexit transitional provisions [23]. It leverages approvals from trusted regulatory authorities to expedite the UK’s assessment process while maintaining robust, independent decision-making. The procedure will run alongside MHRA’s other international collaborations, like Project Orbis, for innovative cancer treatments, and Access Consortium, a work-sharing arrangement covering new active substances, biosimilars, and generics. The IRP is available for applications involving chemical and biological new active substances, generics, hybrids, biosimilars, and fixed combination products. Herbal, homeopathic, and bibliographic applications are not accepted. Products may be submitted if approved by one of MHRA’s reference regulators. These regulators include authorities in Australia, Canada, Switzerland, Singapore, Japan, the US, and the EU/European Economic Area (EEA). Standalone approval from these regulators is required for submission [24].

The IRP has two routes: Recognition A (60-day timeline for approvals within two years) and Recognition B (110 d timeline for complex cases or approvals up to 10 y old). Fig. 3 depicts the flowchart of IRP pathways. Applicants must confirm eligibility six weeks before submission. The electronic Common Technical Document (eCTD) dossier must include RR (Reference Regulator) assessment reports, product details, and post-authorization changes. Recognition a follows strict timelines with no clock stops. Recognition B allows added flexibility, including extra manufacturing sites and updated data, with a clock stop at Day 70 for responses [23].

Post-authorization procedures like variations, line extensions, and renewals can be submitted under IRP. Variations must match RR approvals, while renewals must be filed within 60 d of the RR’s final decision. Market Authorisation Holder (MAHs) may change their RR if justified, with details in the cover letter. The dossier must include key regulatory documents to ensure compliance while making approvals more efficient [23].

The IRP streamlines access to the UK market by eliminating unnecessary regulatory procedures, speeding up market entry, which benefits both patients and the industry. Recognition B, however, may extend timelines due to additional requirements such as Environmental Risk Assessments (ERAs) or manufacturing site inspections. Advanced therapy medicinal products and orphan drugs are only eligible for Recognition B because of their complexity. Applications can be rejected if the evidence is not enough, so it's important to follow MHRA guidelines. Despite the challenges, the IRP offers benefits like faster access to advanced therapies, less regulatory burden, and better international cooperation. It shows MHRA's focus on efficiency, innovation, and public health protection, using global experience while keeping UK-specific oversight. This approach helps regulate effectively while speeding up new treatments for patients [25, 26].

South Africa

In 2018, South Africa made a major change when the Medicines Control Council (MCC) became the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA). This study looks at how SAHPRA's new processes affect its ability to regulate medicines and health products. It focuses on improvements like faster approval times, simpler regulatory pathways, and enhanced review practices [27].

When SAHPRA took over, it faced a backlog of applications left by the MCC, which had struggled with slow approval times, delaying patient access to medicines. To address this, SAHPRA created a backlog stream for applications submitted before February 1, 2018, while applications after that date followed the regular process. Through the use of streamlined regulatory processes, like verification and abbreviated reviews, SAHPRA relied on decisions from trusted agencies like the FDA, EMA, and WHO, which helped reduce unnecessary work [27].

The results show a noticeable improvement in processing times. For the backlog stream, the average approval times were 257 d for generic medicines and approval times for New Chemical Entities (NCEs) are now 303 d, a 68% reduction from the regular process, where NCEs took an average of 792 d. Under the MCC, approval times were between 1,175 and 2,124 d from 2015 to 2017. These improvements are due to the use of new regulatory pathways and process enhancements and better resource management [28].

Standard operating procedures, tracking systems, and an electronic document management system are examples of good review practices that have helped SAHPRA increase efficiency and transparency. Compliance is guaranteed by the quality management department. There are still issues, like lengthy validation processes for applications that are backlogged, the need for more transparent benefit-risk assessment frameworks, and approval. While the approval times still fall short of international standards, the study shows progress in reforming the regulatory system. It recommends using risk-based review methods, making assessment results public, and setting realistic performance targets. By adopting global best practices, SAHPRA can improve public health and strengthen its role [29].

Fig. 3: Flowchart of IRP pathways

Other countries

Several countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and beyond have implemented reliance pathways to expedite drug approvals. Saudi Arabia introduced reliance pathways in 2016, offering a Verification Procedure (30 d review for products approved by both EMA and FDA) and an Abridged Procedure (60 d review for products approved by either EMA or FDA). Egypt adopted similar pathways in 2018, with a Verification Review (30 d approval) and an Abridged Review (60 d approval if launched within a year of reference approval). Jordan established its reliance model in 2017, allowing a Verification Procedure (60 d review for dual EMA and FDA approvals) and an Abridged Procedure (90 d review for a single SRA approval). The United Arab Emirates (UAE) launched a Fast-track Registration for innovative medicines in 2018, while Kuwait set a six-month reliance approval timeline. Bahrain introduced a one-month conditional license in 2018 [30]. Beyond Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Pakistan follows reliance on WHO-prequalified products and approvals from stringent regulatory authorities to fast-track approvals. Malaysia allows reliance on approvals from the EMA, FDA, and other recognized agencies for a streamlined registration process. Georgia utilizes reliance pathways by accepting approvals from the EU, US, and other reference agencies to simplify registration, especially under its new fast-track procedures. These reliance models significantly reduce approval timelines, ensuring faster patient access to essential medicines. Details on eligibility criteria, submission procedures, and timelines for various countries are highlighted in table 2.

Table 2: Details on the eligibility criteria, the submission procedure, and the timeline of various countries

| Country | Eligibility criteria | Procedure | Timeline |

| Saudi Arabia [31] | Verification: Approval and marketing by both the EMA and the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Abridged: Approval and marketing by either EMA or FDA. |

Verification/Abridged | Verification: 30 d Abridged: 60 d |

| Egypt [30] | Verification: Approval by both EMA and FDA. Abridged: Approval by either EMA or FDA. |

Verification/Abridged | Verification: 30 d Abridged: 60 d |

| Jordan [32] | Verification: Approval by both EMA and FDA. Abridged: Approval by either EMA or FDA. |

Verification/Abridged | Verification: 60 d-Abridged: 90 d |

| United Arab Emirates [30] | Approval by EMA, FDA, Swissmedic, Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), or Health Canada (HC). | Verification | Verification: 30 d |

| Pakistan [33] | Approvals from WHO-prequalified products or Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRA) like EMA, FDA. | Verification/Abridged | 150 d |

| Malaysia [34] | Recognition of approvals from EMA, FDA. | Verification/Abridged | Verification: 90 d-Abridged: 120 d |

| Georgia [30] | Acceptance of EU, US, and other reference agency approvals for simplified registration. | Verification/Abridged | Depends on the reference agency approval. |

Importance of reliance during the COVID-19 pandemic

Regulatory reliance was instrumental in the expeditious development, clearance, and monitoring of COVID-19 drugs and vaccines, balancing fast access and risk of doing harm with continued safety and effectiveness. Many NRAs, particularly those with limited resources, used reliance pathways to expedite their decision-making processes during the pandemic. By trusting WHO, USFDA, and EMA to assess the safety and effectiveness of vaccines and treatments, countries could allow for their use by forgoing lengthy local review processes. This approach greatly decreased delays and the amount of time required for drug registration while also assisting in the rapid distribution of COVID-19 countermeasures throughout the world [35].

The USFDA’s Fast Track Designation, introduced in 1988, helps speed up the approval of treatments for serious conditions by allowing early communication and rolling reviews. It can grant approval even with limited data if the drug shows promise. During emergencies like COVID-19, both Fast Track and reliance pathways played a key role by reducing delays and improving access to critical medicines when time was limited [36].

Reliance mechanisms, which encourage collaboration and shared evaluations at both regional and international levels, helped optimize the use of regulatory resources. LMICs particularly benefited from such collaborative efforts, including WHO’s prequalification system and regional initiatives like the East African Community Medicines Regulatory Harmonization. These programs enabled countries with weaker regulatory frameworks to access safe, well-reviewed COVID-19 treatments. Reliance also played a vital role in pharmacovigilance and post-market surveillance, allowing NRAs to implement international risk management strategies, conduct joint safety evaluations, and share adverse event data through platforms like VigiBase [35, 37].

The COVID-19 pandemic sped up regulatory teamwork, leading to joint inspections and new tracking systems. Drug companies like Sanofi and Roche have tested reliance models to see how they work in real life [37].

Reliance pathways also supported Emergency Use Listings (EULs) during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing faster approvals based on prior evaluations. Countries approving vaccines already authorized elsewhere benefited from relying on existing safety and efficacy data instead of conducting their own trials. This strategy helped overcome legal and logistical challenges. Reliance pathways played a significant role in rapidly registering and monitoring COVID-19 vaccines and treatments, improving regulatory efficiency and fostering global collaboration. It also ensured effective and consistent vaccine distribution globally [37].

Together, reliance and Real-World Evidence (RWE) help speed up approvals. For example, RWE played a key role in granting Emergency Use Authorization (EUAs) for COVID-19 vaccines and Pfizer’s antiviral, and it continues to support new-label claims like preventing COVID-19 and expanding indications for internal medicine and cancer treatments. In South Africa, RWE from Pfizer’s clinical trials was utilized by SAHPRA to support its EUAs decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic. A reliance on global real-world data allowed SAHPRA to make regulatory decisions in a timely manner in the context of limited local resources and exemplifies the power of RWE and reliance pathways together to increase access to important therapies [38].

Remdesivir's quick approval and distribution during the COVID-19 pandemic were made possible by Reliance. To facilitate faster decision-making, US, Japan, and EU collaborated to share clinical trial data and evaluations. Access was streamlined when the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW) granted Special Approval for Emergency (SAE), which is based on the FDA's EUA. The EMA shared key clinical trial data and rolling review outcomes with Japan via a joint regulatory platform, enabled by existing confidentiality arrangements among the EMA, FDA, and MHLW/PMDA. This continuous information exchange allowed Japan to avoid duplicating full reviews and instead build on the work already conducted by the EMA and FDA. The Remdesivir case clearly demonstrates how international collaboration and reliance frameworks can accelerate access to critical medicines in public health emergencies while maintaining regulatory rigor [39].

WHO's COVAX-the vaccines pillar of the ACT‑Accelerator-serves as a global collaborative tool that supports regulatory reliance by harmonizing data sharing, procurement, and distribution of COVID‑19 vaccines. Coordinated by Gavi, CEPI, WHO, and UNICEF, COVAX aggregates clinical and real-world data across participating countries to inform regulatory decisions, negotiate equitable pricing, and ensure rapid, fair vaccine access, particularly in LMICs. For example, the COVAX Facility and its Gavi Advance Market Commitment enabled pooled purchasing and shared regulatory dossiers, reducing duplicative reviews and enabling swift emergency authorizations across multiple jurisdictions. COVAX exemplifies how collaborative platforms can extend beyond financing to strategically support reliance pathways-facilitating global alignment on data, regulatory standards, and decision timelines during public health emergencies [40].

The USFDA granted EUA for the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine just 26 d after submission of pivotal trial data, compared to the typical 6–10 mo timeline for full review [41]. Similarly, South Africa’s SAHPRA leveraged global data and real-world evidence to issue Section 21 authorizations within 24 h to 6 w, cutting traditional approval timelines by over 70% [42, 43]. Additionally, clinical trial protocols related to COVID-19 were fast-tracked and approved within 7–10 working days, as reported in SAHPRA’s 2021–22 annual report. WHO’s EULs process approved the Pfizer vaccine only 19 d after UK approval, supporting rapid reliance-based pathways. Through the COVAX facility, over 1.8 billion vaccine doses were distributed across 140 lMICs within two years, with many nations achieving access within 30–45 d of initial international authorization [44, 45].

Challenges

Regulatory reliance can help agencies work more efficiently, but several challenges can limit its success. There are significant differences in laws, regulations, cultures, and proficiency levels across different regulatory systems. First and foremost, a lack of a legal foundation for regulatory reliance may cause misunderstandings, delays, and duplications in the relying authority's approval process. However, being legally prepared is difficult and time-consuming [46]. Even with laws in place, political commitment alone may not be enough to ensure strong government support. Limited access to complete regulatory reports can also slow the process, requiring contracts to protect confidential information. Language differences make communication harder and increase translation costs. Countries often have different regulatory standards, which can create conflicts when assessing products. Reliance paths are used less frequently because some regulators prefer independent evaluations that are concerned about confidentiality or are just ignorant of them. Relying on other authorities is more difficult because many agencies are hesitant to accept clinical data from different countries. The caliber of reliance judgments may also be impacted by variations in the regulatory authorities' areas of expertise [47].

Adoption may also be slowed by internal agency resistance, frequently resulting from a lack of knowledge about reference agencies' operations. The effectiveness of reliance routes may be increased by removing these obstacles via improved training, communication, and policy alignment. Adoption may also be slowed by internal agency resistance, frequently resulting from a lack of knowledge about reference agencies' operations. The effectiveness of reliance routes may be increased by removing these obstacles via improved training, communication, and policy alignment [47]. It is difficult for NRAs to implement dependence routes consistently, as there is no internationally recognized structure. This results in uncertainties about the choice of model, the information needed, and the scope of regulatory assessment [48].

Different versions of products marketed in different markets

When a company makes different versions of a product at various sites for different markets, regulatory agencies must inspect each site separately. This can create complications in regulatory approvals and oversight, especially when each version has slight differences in formulation or manufacturing processes. Agencies relying on reports from trusted regulatory bodies must ensure they are reviewing the same version of the product to avoid issues. If not, there could be variations in the product’s efficacy, safety, and quality across different regions markets, potentially affecting patient outcomes. A notable example is Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty), which had formulation differences between the U. S. and EU versions-particularly in the buffer system used Phosphate-buffered saline in the U. S. vs. Tris buffer in the EU) and storage requirements. These differences led to regulatory delays, as authorities could not rely directly on each other's assessments without confirming that the data corresponded to the same product version [1].

Overly redacted inspection and assessment reports

A global regulatory environment can limit information sharing because many regulatory bodies still follow old confidentiality rules. Inspection and assessment reports that are overly redacted can become useless and slow down the process. When key details are missing, authorities either need to ask for more information or do their own checks, which cause delays. Confidentiality rules need to be updated to strike a balance between transparency and protecting important information to help streamline the process [1].

In response to this need for mutual support, the WHO is recommending the use of Good Reliance Practices (GRelP). These GRelP address the need to share unredacted or minimally redacted reports amongst trusted authorities through the agreement of formal confidentiality measures, as well as developing clearer and more proactive communications and transparency protocols that facilitate mutual reliance and the protection of sensitive proprietary information [20].

A major obstacle to relying on the previous regulatory work of others is the differing approaches that regulatory authorities (RAs) take with regard to the classification of post-approval changes. For example, a formulation change may be considered “minor” in one jurisdiction, but “major” in another jurisdiction, leading to differing expectations when bringing a product to market.

A comparative Table-3 illustrates that many RAs categorize changes (for example, Europe has "Type IA", "Type IB", and "Type II", while the, WHO, U. S or Canada has "minor" and "major") would help demonstrate the inconsistency of these regulatory classifications across various jurisdictions. Some other countries (like Australia-Therapeutic Goods Administration and South Africa-South African Health Products Regulatory Authority) also include decisional classifications (i. e., category 1/2, or type I/II with some additional notification pathways). Additionally, few countries regulatory agencies (UAE-Ministry of Health and Prevention, Malaysia-National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency, and Saudi Arabia-Saudi Food and Drug Authority) use major and minor variations, some of which include notifications or administrative changes. When comparing this inconsistency visually, it will be easier to explain how this inconsistency leads to complications of relying on others' regulatory work and also demonstrates the need for the global convergence of classification systems and regulations [49].

Table 3: Post-approval change (PAC) classifications by various countries

| Country | Classification of post-approval changes |

| USA (FDA) | Major, Moderate, Minor |

| EU (EMA) | Type IA, Type IB, Type II |

| Australia (TGA) | Category 1, Category 2, Notifications |

| South Africa (SAHPRA) | Type I (Major), Type II (Moderate), Notifications |

| United Arab Emirates (MOHAP) | Major Variation, Minor Variation |

| Malaysia (NPRA) | Major Variation, Minor Variation, Notification |

| Saudi Arabia (SFDA) | Major Variation, Minor Variation, Administrative Change |

| WHO (GRelP) | Major, Moderate, Minor |

Assessor reluctance to adopt reliance pathways

Regulatory assessors may be hesitant to adopt reliance mechanisms due to concerns about job security and changes to their roles. To address this, it’s important to emphasize the benefits of reliance, such as increased efficiency, faster approvals, and the opportunity for assessors to focus on higher-value tasks like risk-based assessments and post-market surveillance. Streamlining routine tasks allows assessors to develop new skills, engage in strategic decisions, and contribute to global harmonization and policy development. Training programs can help assessors transition into elevated roles, ensuring their professional growth. Clear communication from leadership is essential to reassure assessors that reliance mechanisms will enhance, not reduce, their importance in the regulatory system [5].

National “Requirements” that need reassessment

Some countries enforce outdated regulatory requirements that may no longer be necessary in a modern, interconnected regulatory landscape. Re-examining the requirements, including local laboratory testing for product authorization and redundant lot release procedures at the local level when such data can be easily retrieved internationally through established standards, the continued demand for Certificates of Pharmaceutical Products (COPP) While this may help with the facilitation of access to Medicines, Wherever database compliance exists for regulators, they therefore need to re-evaluate their reliance frameworks. That would eliminate duplication and create efficiencies in the regulatory process [1].

Aligning the "Description of differences" Template with the common technical document (CTD) format

The CTD format, which is used globally to standardize the submission of regulatory information for pharmaceuticals, includes the "Description of Differences" template. Modules covering every facet of the product dossier, from manufacturing and quality to safety and efficacy data, are included in the CTD format. Applicants can make sure that their submissions comply with international standards and streamline the reliance process across jurisdictions by matching the "Description of Differences" template with the CTD format [10].

Standardizing terminology for a clear reliance process

To guarantee uniformity and clarity in the reliance process, consistent vocabulary and definitions must be used in addition to these instruments. As advised by numerous international organizations, creating a uniform lexicon of reliance phrases will assist prevent misunderstandings and guarantee that all parties involved are in agreement with the standards and expectations for reliance. This is especially crucial when it comes to PACs, since disparities in nomenclature can cause the approval process to drag on and become complicated [11].

Challenges posed by procedural differences among NRAs

Another significant obstacle is the variations in NRA procedures. These variations may show up as distinct change classes, different documentation specifications, and different PAC approval schedules. For example, one NRA may swiftly approve a modification that it deems minor, but another may label the same change as serious, requiring a thorough review. Because NRAs may not always agree on the classification or significance of a particular modification, these discrepancies make it challenging to apply reliance consistently across countries [11].

The need for standardized documentation in regulatory convergence

The implementation of uniform documentation requirements is a crucial component of regulatory convergence. At the moment, NRAs might differ greatly in the amount of information needed in regulatory submissions; some need a great deal of documentation, while others are more lenient. Because of this discrepancy, businesses seeking to use reliance paths may have to compile multiple copies of the same dossier in order to satisfy the requirements of different NRAs. Companies might concentrate more on guaranteeing the quality and safety of their products if documentation requirements were standardized, which would expedite the reliance process and lessen their administrative load [5].

Future perspectives

To be prepared for future pandemics, it is essential to increase global coordination among all NRAs and promote a unified emergency response. To achieve this, both the WHO and the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA) should continue to play a key role in facilitating alignment among the NRAs and other stakeholders [50]. The USFDA has already demonstrated success in this area, having implemented various approaches to promote innovation among biopharmaceutical companies developing therapies for rare and life-threatening diseases. Such global examples can serve as practical models for LMICs aiming to strengthen their regulatory preparedness.

In future emergency scenarios, whether involving vaccines or other critical medicines, LMICs such as the CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States), LATAM (Latin America), and GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) can significantly benefit from the expertise and resources of well-established regulatory authorities in the USA and Europe. Because of their strong infrastructure and scientific expertise, these authorities frequently approve medications after thorough evaluations, and thus their judgments can be trusted.

In LMICs, many NRAs lack the resources and training necessary to carry out their regulatory responsibilities efficiently. Regular training based on organizational and individual requirements should address this. To increase performance, NRAs must also carefully plan and allocate their resources. It is necessary to resolve internal problems that hinder the implementation of training lessons. To make learning more applicable, real-world examples from LMICs should be incorporated into future teaching. Where feasible, other competent institutions should help by offering training. The WHO should also focus on enhancing training initiatives by learning from previous mistakes [51].

The creation of thorough guidelines for GRP should be given top priority by the ICH. Higher levels of guideline harmonization and standard convergence have been linked to increased reliance on regulatory frameworks [52].

Harmonization towards a single worldwide regulatory standard for data requirements is also crucial, as it is the broad implementation of ICH and WHO principles. These advancements would accelerate patient access to essential and innovative medications by streamlining drug development processes, optimizing the use of limited regulatory resources, and reducing complexity [38].

In a worldwide society with limited resources and rising health needs, regulatory dependence is a sensible strategy for regulating medical products. When properly applied, it guarantees quicker access to safe and effective therapies, which benefits patients, industry, and regulators [52]. Similar to reliance, other pathways can be used during the pandemic.

In Singapore, the Pandemic Special Access Route (PSAR) started in December 2020 to speed up access to essential vaccines, medicines, and medical devices during pandemics. It enables the Health Sciences Authority (HSA) review COVID-19 vaccines and treatments sooner through a rolling submission process. Companies send data as studies progress so HSA can begin evaluations without waiting for an entire dataset. This process has helped approve two COVID-19 vaccines quickly while keeping high-quality, safety, and effectiveness standards.

Cloud-based technologies for sharing regulatory information are among the most exciting trends. By enabling real-time access, sharing, and review of regulatory data, these technologies enables NRAs in many jurisdictions to communicate and work together more effectively. To speed up the decision-making process for PACs, a cloud-based system allows a relying NRA to easily access the assessment reports and inspection findings of a reference NRA. These technologies increase transparency and trust among regulatory bodies while streamlining reliance procedures.

By increasing the effectiveness and precision of regulatory evaluations, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning are becoming more potent instruments that have the potential to strengthen reliance further. AI algorithms, for instance, can be used to examine extensive data from post-market surveillance, clinical trials, and other sources to spot possible trends and safety flags. Especially in verification-based reliance pathways, specific machine learning algorithms hold promise for enhancing verification-based reliance. For instance, Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools used to extract and compare the key regulatory decision elements, such as benefit-risk conclusions, adverse event trends, and study endpoints from publicly available assessment reports issued by Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRAs). This could help National Regulatory Authorities (NRAs) verify regulatory decisions in a more structured and consistent manner. Similarly, supervised learning models (e. g., random forests, gradient boosting machines) can be trained on historical post-approval change (PAC) classifications. These models could predict the risk level for PACs according to the product lifecycle phase and the established regulatory precedent, which should minimize the discrepancies among agencies. Unsupervised learning methods will allow the users of PACs to cluster similar regulatory decisions, as well as identify the outlier or divergence patterns. Taken together, these AI applications would assist NRAs in directing their limited resources to areas of greatest uncertainty and allow both reproducibility and evidence-based decision making. One promising approach is the development of WHO-oriented virtual training modules developed specifically for LMICs for the real-life challenges they face. The workshops should include actual case studies, simulations, and training on using digital tools, including AI-assisted regulatory platforms. Establishing such structured and recurring training systems can build long-term competency, strengthen reliance networks, and promote global regulatory harmonization. Ras can then concentrate their resources on the most critical concerns by using these insights to guide reliance-based regulatory decisions.

CONCLUSION

The Reliance Pathway, which leverages assessments from trusted regulatory authorities, has emerged as a crucial mechanism to accelerate drug registration, especially in LMICs. By adopting this approach, National Regulatory Authorities (NRAs) can optimize limited resources, shorten approval timelines, uphold regulatory autonomy, and improve access to quality-assured medicines. Programs like the WHO Collaborative Registration Procedure (CRP) exemplify the success of reliance, promoting global harmonization and expediting approvals. South Africa’s SAHPRA, for example, adopted abridged and verification review models after transitioning from the Medicines Control Council, relying on trusted agencies such as the EMA, FDA, and WHO. This shift resulted in a 68% reduction in approval times, helping to clear backlogs and speed up access to essential medicines. Despite these benefits, reliance remains underutilized due to inefficient procedures, limited acceptance, and challenges in PAC management. To unlock its full potential, reliance requires stronger engagement from NRAs, improved communication with reference agencies, and standardized PAC criteria. Enhancing real-time data sharing platforms can reduce duplication, streamline workflows, and ensure timely access to safe, effective medicines. Strengthening reliance pathways also involves raising stakeholder awareness, especially in resource-limited settings, and building capacity through support from established regulatory agencies. Organizations like the ICH can further support global alignment by developing guidance such as the Good Reliance Practices (GRelP) and harmonizing PAC classifications, including standard definitions of “minor” and “major” variations. A comparative PAC classification framework could help identify discrepancies and foster convergence. Aligning reliance practices with ICH standards ensures accelerated yet rigorous regulatory reviews, promoting equitable access to essential medications while safeguarding public health through enhanced trust, efficiency, and international cooperation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, for library access and support provided for this literature search.

FUNDING

This study received no external funding.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Gurram Gnaneshwari: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–Original Draft Preparation. Kiran Nagaraj: Visualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing–Review. Shailee Dewan: Methodology, Writing–Review and Editing

Vignesh Manoharan: Writing–Review and Editing. Pradeep Manohar Muragundi: Conceptualization, Project Administration, Resource, Supervision, Validation, Visualization.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no relevant affiliations or financial interests that could appeared as a conflict of interest concerning the subject matter or materials discussed in this paper.

REFERENCES

Reliance-Based Regulatory Pathways The Key to Smart(Er) Regulation? Global Forum; 2022. Available from: https://globalforum.diaglobal.org/issue./reliance-based-regulatory-pathways-the-key-to-smarter-regulation/. [Last accessed on 24 Feb 2025].

COVID-19 Vaccines Safety Surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/covid-19vaccines-safety-surveillance-manual/covid19vaccines_introduction_manual. [Last accessed on 10 Jul 2025].

Khadem Broojerdi A, Alfonso C, Ostad Ali Dehaghi R, Refaat M, Sillo HB. Worldwide assessment of low and middle-income countries regulatory preparedness to approve medical products during public health emergencies. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Aug 13;8:722872. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.722872, PMID 34485350, PMCID PMC8414408.

IFPMA. IFPMA Position Paper on Regulatory Reliance. Geneva: International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations. Available from: https://www.ifpma.org/publications/ifpma-position-paper-on-regulatory-reliance/. [Last accessed on 26 Feb 2025].

Mangia F, Lin YM, Armando J, Dominguez K, Rozhnova V, Ausborn S. Unleashing the power of reliance for post approval changes: a journey with 48 National Regulatory Authorities. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2024;58(6):997-1005. doi: 10.1007/s43441-024-00677-8, PMID 39048766.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Regulatory Reliance Principles: Concept Note and Recommendations. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization. Available from: https://prais.paho.org/en/paho-regulatory-reliance-principles-concept-note-and-recommendations/. [Last accessed on 10 Jul 2025].

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). International Regulatory Collaboration: Project Orbis Update. In: Silver Spring, MD: FDA; 2023. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media. [Last accessed on 02 Mar 2025].

Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), Australia Canada Singapore, Switzerland United Kingdom (Access) Consortium. Canberra (AU): TGA. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/about-tga/international/australia-canada-singapore-switzerland-united-kingdom-access-consortium. [Last accessed on 02 Mar 2025].

International Recognition Procedure. London (UK): GOV. UK. UK: Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/international-recognition-procedure/international-recognition-procedure. [Last accessed on 02 Mar 2025].

Citeline. Regulatory Reliance Pathways: Challenges and Opportunities Ahead Citeline. Available from: https://.citeline.com/ps149684 /regulatory-reliance-pathwayschallenges-and-opportunities-ahead. [Last accessed on 02 Mar 2025].

Center for Innovation in Regulatory Science (CIRS). CIRS RD Briefing 82-Regulatory Reliance Pathways: Opportunities and Barriers. In: London, UK: CIRS; Available from: https://www.cirsci.org/publications/cirs-rd-briefing-82regulatory-reliance-pathways-opportunities-and-barriers. [Last accessed on 02 Mar 2025].

International Pharmaceutical Regulators Programme (IPRP). IPRP Questions and Answers on Reliance. Geneva: IPRP; 2023 Jun 13. Available from: https://admin.iprp.global/sites/default/files/2023-06/IPRP_RelianceQ%26As_2023_0613.pdf. [Last accessed on 25 Jun 2025].

Saint Raymond A, Valentin M, Nakashima N, Orphanos N, Santos G, Balkamos G. Reliance is key to effective access and oversight of medical products in case of public health emergencies. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2022 Jul;15(7):805-10. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2022.2088503, PMID 35945703.

Org R. Access Consortium A Global Collaborative Pathway. Gand L Scientific; 2023. Available from: https://gandlscientific.s3-assets.com/manan-shah-raps-blog-0723.pdf. [Last accessed on 02 Mar 2025].

Access Consortium Promise Pilot Pathway: Benefit and Requirements. DLRC Group. Available from: https://www.dlrcgroup.com/access-consortium-promise-pilot-pathway-benefit-and-requirements. [Last accessed on 04 Mar 2025].

Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) Project Orbis. Canberra (AU): TGA. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/project-orbis.

Shum M. Work sharing reliance and other novel approaches to accelerating review approvals and access. Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/presentation-work-sharing-reliance-approaches-accelerating-review-approvals-access.pdf. [Last accessed on 04 Mar 2025].

Project Orbis. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Available from: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-orbis. [Last accessed on 04 Mar 2025].

Project Orbis: global collaborative oncology review program–05/13/2021. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA); 2021 May 13. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/science-research/fda-grand-rounds/project-orbisglobal-collaborative-oncology-review-program-05132021-05132021. [Last accessed on 07 Mar 2025].

World Health Organization (WHO), translator. 1033-annex 10: Good Reliance Practices in the Regulation of Medical Products. In: Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/annex-10-trs-1033. [Last accessed on 08 Mar 2025].

Vaz A, Roldao Santos M, Gwaza L, Mezquita Gonzalez E, Pajewska Lewandowska M, Azatyan S. WHO collaborative registration procedure using stringent regulatory authorities medicine evaluation: reliance in action? Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2022 Jan;15(1):11-7. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2022.2037419, PMID 35130803.

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). MHRA Grants First Approval via the New International Recognition Procedure. London, UK: GOV. UK. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/mhra-grants-first-approval-via-the-new-international-recognition-procedure-in-30-d. [Last accessed on 11 Mar 2025].

DLRC Group. A first look: MHRA’s new International Recognition Procedure. DLRC Group. Available from: https://www.dlrcgroup.com/ready-for-january2024-a-first-look-at-mhras-new-international-recognition-procedure-irp. [Last accessed on 12 Mar 2025].

Fast Tracking Approval of Medicines–UK Publishes Detailed Guidance. Covington & Burling. LLP. Inside EU Life Sciences; 2023 Sep 11. Available from: https://www.com/2023/09/11/fast-tacking-approval-of-medicines-ukpublishes-detailed-guidance-on-its-new-international-recognition-procedure. [Last accessed on 12 Mar 2025].

Pharma Lex. UK’s IRP Paves the Way for Faster Market Access. Pharma Lex; Available from: https://www.pharmalex.com/thoughtleadership/blogs/understanding-the-uksinternational-recognition-procedure. [Last accessed on 14 Mar 2025].

Danks L, Semete Makokotlela B, Otwombe K, Parag Y, Walker S, Salek S. Evaluation of the impact of reliance on the regulatory performance in the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority: implications for African regulatory authorities. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Oct 23;10:1265058. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1265058, PMID 37937144, PMCID PMC10626996.

Keyter A, Salek S, Danks L, Nkambule P, Semete Makokotlela B, Walker S. South African regulatory authority: the impact of reliance on the review process leading to improved patient access. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Jul 23;12:699063. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.699063, PMID 34366850, PMCID PMC8342884.

South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA). Reliance guideline. Pretoria (ZA): SAHPRA. Available from: https://www.sahpra.org.za/document/reliance-guideline. [Last accessed on 21 Mar 2025].

Expediting Access Through Reliance Pathways: Mena Region. Biomapas. Available from: https://www.biomapas.com/expediting-access-through-reliance-pathways-mean-region. [Last accessed on 24 Mar 2025].

Regulatory framework for drugs approval. Saudi Food and Drug Authority. In: Riyadh: SFDA. Available from: https://www.sfda.gov.sa/en/regulations/65436. [Last accessed on 24 Mar 2025].

Jordan FDA Adopts Reliance Review Model. Global Forum; 2019 Oct. Available from: https://globalforum.diaglobal.org/issue./jordan-fda-adopts-reliance-review-model. [Last accessed on 24 Mar 2025].

Pakistan Reliance Guidance for Pharmaceutical Regulatory Processes. Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan. 2nd ed. 2023. Islamabad: DRAP. Available from: https://www.dra.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads.2023/01relaince-mechansim-in-regulatory-processess.pdf. [Last accessed on 31 Mar 2025].

National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency (NPRA). Guideline on facilitated registration pathway: abbreviated and verification review. In: Ministry of Health Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur (MY), NPRA; 2019 Mar. Available from: https://www.npra.gov.my/easyarticles/images/users/1051/facilitatedregistration-pathway-guideline_final.pdf. [Last accessed on 31 Mar 2025].

Van Der Zee IT, Vreman RA, Liberti L, Garza MA. Regulatory reliance pathways during health emergencies: enabling timely authorizations for COVID-19 vaccines in Latin America. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2022 Aug 30;46:e115. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2022.115, PMID 36060200, PMCID PMC9426952.

Pavithra GM, Maanvizhi S. Fast track USA regulatory approval for drugs to treat emerging infectious diseases. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2021 Jul;14(7):1-4. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021.v14i7.41761.

COVID-19 vaccines: safety surveillance manual stakeholders. World Health Organization (WHO); 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032781. [Last accessed on 24 Mar 2025].

Patel P, Macdonald JC, Boobalan J, Marsden M, Rizzi R, Zenon M. Regulatory agilities impacting review timelines for Pfizer/BioNTech's BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: a retrospective study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Nov 8;10:1275817. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1275817, PMID 38020129, PMCID PMC10664654.

Saint Raymond A, Sato J, Kishioka Y, Teixeira T, Hasslboeck C, Kweder SL. Remdesivir emergency approvals: a comparison of the U.S., Japanese, and EU systems. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(10):1095-101. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2020.1821650, PMID 32909843.

COVAX Explained. Gavi the Vaccine Alliance; 2021. Available from: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/covax-explained. [Last accessed on 25 Jun 2025].

Pfizer Corona Virus Vaccine FDA Emergency Use Authorization. Axios; 2020 Nov 20. Available from: https://www.axios.com/2020/11/20/pfizer-coronavirus-vaccine-fda-emergency-use-authorization. [Last accessed on 02 Aug 2025].

Matwadia E. Three ways COVID sped up SA’s medicine approvals process and how it can help the National Health Insurance Scheme. Johannesburg: the Mail and Guardian; 2022 Nov 7. Available from: https://mg.co.za/health/2022-11-07-three-ways-covid-sped-up-sas-medicine-approvals-process-and-how-it-can-help-the-national-health-insurance-scheme. [Last accessed on 02 Aug 2025].

South African Health Products Regulatory Authority. SAHPRA annual report 2021/22. Available from: https://www.sahpra.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/202122sahpra-annual-report.pdf. [Last accessed on 02 Aug 2025].

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. COVAX timeline. Available from: https://www.gavi.org/covax/timeline?utm. [Last accessed on 02 Aug 2025].

Mao W, Zimmerman A, Urli Hodges E, Ortiz E, Dods G, Taylor A. Comparing research and development launch and scale up timelines of 18 vaccines: lessons learnt from COVID-19 and implications for other infectious diseases. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(9):e012855. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012855, PMID 37696544.

Xu M, Zhang L, Feng X, Zhang Z, Huang Y. Regulatory reliance for convergence and harmonisation in the medical device space in Asia-Pacific. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(8):e009798. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009798, PMID 35985696.

Mukonzo JK, Ndagije HB, Sabblah GT, Mathenge W, Price DA, Grasela TH. Expanding regulatory science: regulatory complementarity and reliance. Clin Transl Sci. 2024 Jan 1;17(1):e13683. doi: 10.1111/cts.13683, PMID 37957894.

Sok Bee L. Benefits and challenges of reliance pathways; 2019. Available from: https://apac-asia/images/achievements/pdf/8th/5_ra/12_benefits% 20and%20challenges%20of%20reliance%20pathways.pdf. [Last accessed on 24 Mar 2025].

De Lucia ML, Comesana C, Rodriguez H, Dangy Caye A. Impact assessment of divergence on post approval changes classifications of Latin America region with Europe and the United States, and propositions to harmonize classification based on risk as a path to build the trust between national regulatory agencies. Clin Ther. 2024 Feb;46(2):164-72. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2023.11.005, PMID 38092583.

Geraci G, Bernat J, Rodier C, Acha V, Acquah J, Beakes Read G. Medicinal product development and regulatory agilities implemented during the early phases of the COVID-19 Pandemic: experiences and implications for the future an industry view. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2023 Sep;57(5):940-51. doi: 10.1007/s43441-023-00536-y, PMID 37266868, PMCID PMC10237066.

Dehaghi RO, Khadem Broojerdi A, Paganini L, Sillo HB. Collaborative training of regulators as an approach for strengthening regulatory systems in LMICs: experiences of the WHO and Swissmedic. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 May 18;10:1173291. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1173291, PMID 37275356, PMCID PMC10233123.

Doerr P, Valentin M, Nakashima N, Orphanos N, Santos G, Balkamos G. Reliance: a smarter way of regulating medical products the IPRP survey. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021 Feb;14(2):173-7. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2021.1865798, PMID 33355025.

Importance of Reliance to Support Strengthening Latin American and Caribbean Regulatory Systems. Available from: https://pharmaboardroom.com/articles/importance-of-reliance-to-support-strengthening-latin-american-caribbean-regulatory-systems. [Last accessed on 24 Mar 2025].