Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 42-51Review Article

ADVANCED FABRICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF SILVER NANOPARTICLES USING AI TECHNIQUES

ZAINAB LAFI1,2*, SINA MATALQAH1,2, SHERINE ASHA3, NISREEN ASHA4, HALA MHAIDAT5, SARA YOUSEF ASHA3

1Pharmacological and Diagnostic Research Center, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Ahliyya Amman University-Amman, Jordan. 2Department of Pharmaceutics and Pharmaceutical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Ahliyya Amman University-Amman, Jordan. 3School of Medicine, University of Jordan-Amman. 4The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences, United States-Oklahoma. 5King Abdullah University Hospital – Irbid, Jordan

*Corresponding author: Zainab Lafi; *Email: z.lafi@ammanu.edu.jo

Received: 13 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 14 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

The integration of machine learning (ML) into nanoscience has transformed the fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), enabling precise control over particle size, shape, and functionalization. This review highlights the application of supervised and unsupervised ML models, such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), support vector machines (SVMs), and decision trees, in optimizing AgNP synthesis parameters, including temperature, pH, and reducing agent concentration. Emphasis is placed on green synthesis methods using plant extracts, where ML predicts eco-friendly conditions with minimal experimental input. Characterization techniques benefit from ML-driven image and spectral data analysis, enhancing speed and accuracy. ML is also pivotal in predicting the toxicity and biocompatibility of AgNPs, reducing reliance on animal testing and enabling safer biomedical applications. ML reduced synthesis optimization time by 30%," and to specify the types of ML techniques applied, like neural networks or support vector machines (SVMs). Furthermore, ML enhances functionalization strategies for drug delivery, biosensing, and environmental remediation. By quantifying performance outcomes and improving reproducibility, ML supports the scalable and sustainable development of AgNPs. This review offers a detailed synthesis of current advances and identifies future opportunities for intelligent, data-driven nanomaterial design.

Keywords: Silver nanoparticles, Machine learning, Green synthesis, Toxicity prediction, Artificial neural networks, Support vector machines, Functionalization, Nanomedicine, Biosensors

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.55011 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are a notable category of an extensive variety of nanoparticles that have attracted much attention in scientific research owing to their distinctive physical, chemical, and biological properties due to their high surface area and quantum effects [1]. These nanoparticles exhibit strong antimicrobial, conductive, and catalytic properties, making them valuable across various fields, such as engineering, medicine, chemistry, and physics.

AgNPs are extensively utilized in the medical field owing to their antimicrobial characteristics, which make them effective in wound dressing [2], coatings for medical instruments [3, 4], and antibacterial formulations [5, 6]. Additionally, they are being investigated for their potential in cancer therapy [7-9], and drug delivery is attributed to their capacity to selectively target cells [10-12].

AgNPs have been applied in the field of electronics, particularly in conductive inks utilized for printed electronics [13], sensors [14], and flexible circuits. The exceptional conductivity of these materials renders them highly suitable for incorporation into advanced electronic devices [15].

Additionally, AgNPs play a significant role in environmental applications, particularly in the purification of water, owing to their effectiveness in eliminating harmful bacteria and pathogens [16, 17]. Additionally, they contribute to pollution management and the treatment of wastewater by facilitating the degradation of pollutants [18].

The emergence of machine learning (ML) has significantly revolutionized scientific inquiry across various fields, including biology [19], physics [20], chemistry [21], medicine, and the social sciences. ML, which is a branch of artificial intelligence (AI), allows computers to identify patterns within data and to make predictions or decisions autonomously without the need for explicit programming (table 1) [22]. Its transformative impact on scientific research can be understood through several principal domains:

Table 1: Impact of using machine learning (ML) in parameters optimization of AgNO₃-based nanoparticle synthesis

| Parameter | Range/levels | Impact on outcome | ML optimization approach | Potential algorithms |

| AgNO₃ Concentration | 0.1–1.0 M | Controls nanoparticle size and yield | Regression, Classification | SVR, Random Forest, ANN |

| Reducing Agent Type | NaBH₄, AA, etc. | Affects reduction rate and morphology | Categorical Feature Encoding | Decision Trees, SVM |

| Reducing Agent Conc. | 0.1–10 mmol | Influences shape and size distribution | Hyperparameter Tuning | Bayesian Optimization |

| pH | 3–12 | Governs nucleation and growth kinetics | Response Surface Modeling | Gaussian Process |

| Reaction Time | 5–120 min | Determines growth completion | Time-Series Prediction | LSTM, ARIMA |

| Temperature | 25–90 °C | Control of reaction kinetics | Regression | XGBoost, ANN |

| Stabilizer Type | PVP, CTAB, etc. | Affects aggregation and stability | Feature Selection | Random Forest, SVM |

| Stirring Speed | 100–1000 rpm | Influences homogeneity | Optimization via DOE+ML | Genetic Algorithm, ANN |

| Precursor-to-Reducing Agent Ratio | 1:1 – 1:10 | Affects size distribution and yield | Multi-Objective Optimization | Evolutionary Algorithms |

ML is a particularly expert at processing extensive datasets, revealing patterns that may be challenging or unfeasible for humans to identify through manual analysis [23]. With scientific research producing a growing volume of data from experiments, simulations, and observations such as genomic information, climate models, and astronomical data, ML algorithms have become crucial for discovering secret insights.

For example, in genomics, ML helps identify patterns in DNA that correspond to diseases or traits [24]; in astronomy, ML is used to classify stars and galaxies from telescope data [25], while in chemistry, ML aids in the discovery of new materials and drug compounds by predicting molecular properties [26].

ML can also be employed to speed up hypothesis testing [27]. Traditionally, scientific research follows a hypothesis-driven approach, wherein a researcher develops a hypothesis and subsequently creates experiments to evaluate it. However, ML facilitates the transition to a data-driven scientific approach wherein hypotheses are derived from initial data analysis. ML models can propose research directions by identifying correlations and patterns within existing datasets, thereby resulting in innovative hypotheses (table 2) [28].

Table 2: Examples of machine learning assisted AgNPs fabrication and optimization

| Type of Ag NPs | Reducing agent | Method | Parameter | Application | ML techniques used | Reference |

| Monodisperse Spherical | Trisodium citrate dihydrate (TSC) | High-throughput microfluidic platform | Nanoparticles with the desired absorbance spectrum. | Relationship between chemical composition and optical properties | DNN BO |

[29] |

| Spherical | Sodium citrate | Ultrasound-intensified Lee-Meisel | Ag: citrate ratio Ultrasound power Reaction | NA | Decision Tree Regressor | [30] |

| Face-centered cubic | Using soluble starches | Green method | Size temperature, Starch stabilizer AgNO3 concentration |

NA | CNN-LSTM hybrid model with accuracy achieved 83.50% of recall. | [31] |

| Spherical | Sodium citrate | High-throughput synthesis | Concentrations of AgNO3 and citrate Reaction conditions |

Ooptical properties absorption spectrum | Nonlinear support vector regression | [32] |

| Spherical | Tannic acid in the presence of trisodium citrate | Continuous flow T-junction device | Temperature, pH, time | NA | DT, RF, XG Boost | [33] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone coated AgNPs with three Sizes | Variable | 721 datasets | Dose, Type, Size Exposure time |

Soil enzyme activity | ANN, GA, RF | [34] |

| Spherical | Titanium citrate and tannic acid | T-junction device | Temperature, Time, chemical Reagent concentration/ratio, Reaction precursors, Reaction ligands, solution reagents, Microreactor channel structure, External stimuli | NA | Tree-based models | [35] |

This has led to breakthroughs in fields such as cancer research, neuroscience, automated experimental processes, robotics, autonomous laboratories, predictive modeling and simulation, reducing bias and improving reproducibility and personalized medicine [36-41].

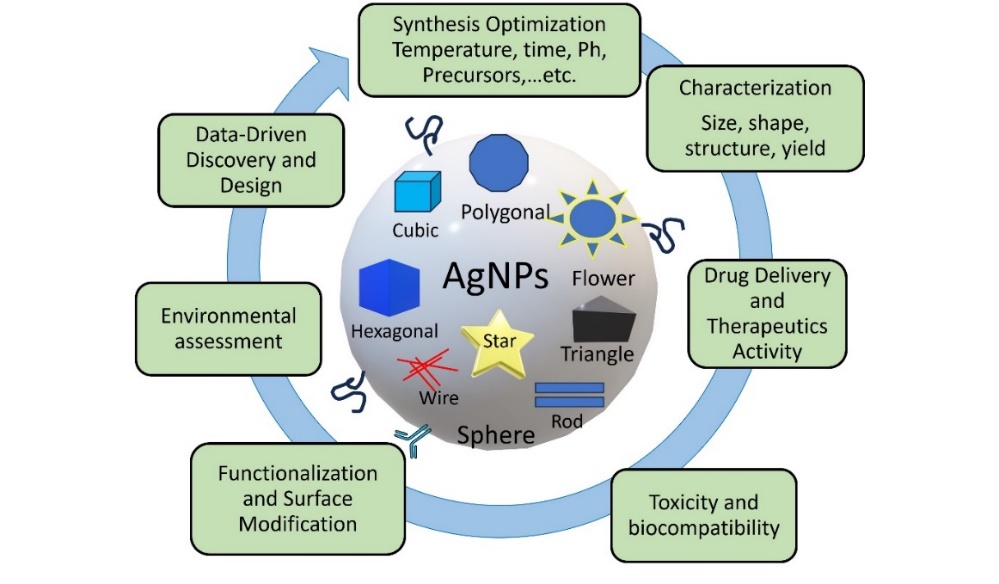

ML plays a transformative role in advancing research on silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), particularly in the areas of synthesis, characterization, functionalization and surface modification; toxicity and biocompatibility; drug delivery and therapeutics; data-driven discovery and design; and, ultimately, environmental role (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Different categories for AgNPs fabrication and optimization that need ML integration" while also showing the versatility of AgNPs shapes

In conclusion, the rationale for integrating machine learning (ML) into silver nanoparticle (AgNP) research stems from the inherent limitations of conventional approaches, which often rely on trial-and-error methods. These traditional techniques are not only time-consuming but also resource-intensive, as they typically involve varying one parameter at a time and conducting numerous experimental trials to achieve optimal results. This approach makes it challenging to simultaneously optimize multiple factors and to handle the complexity of the datasets generated. ML, on the other hand, offers a transformative solution by enabling multi-parameter optimization and efficient handling of large, complex datasets [42]. For instance, ML algorithms such as neural networks and support vector machines (SVMs) can learn from existing data to predict optimal synthesis conditions, significantly reducing the time and resources required for experimentation [43]. Additionally, ML can uncover patterns and relationships within the data that are not readily apparent through conventional methods, leading to more precise and reproducible outcomes. The unique suitability of ML for AgNP research lies in its ability to enhance the precision of nanoparticle synthesis, facilitate green synthesis methods, and improve the characterization of nanoparticles through automated analysis of imaging and spectroscopic data [44, 45]. By addressing the limitations of traditional approaches, ML provides a robust framework for advancing AgNP research and development.

Synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs)

ML has greatly enhanced the synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) by increasing the efficiency, accuracy, and characteristics of the materials involved. The primary contributions include the following:

ML algorithms can predict the most suitable synthesis conditions, such as temperature, pH, and concentration, for producing AgNPs of specific sizes, shapes, and characteristics [46]. For instance, these models can determine the optimal combinations of reductants and stabilizers necessary to regulate particle size and morphology effectively.

As the emphasis on environmentally sustainable practices increases, ML plays a crucial role in optimizing the parameters for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) utilizing biological agents, such as plant extracts. The influence of different biological components on the properties of nanoparticles, including their size and surface charge, has been predicted [47].

The integration of ML in automation significantly decreases the requirement for physical experiments. This is achieved through the application of methodologies such as design of experiments (DoE) in conjunction with machine learning [48], which accelerates the optimization of the synthesis process [49]. Núñez, R. N et al. optimized a method for the synthesis of AgNPs using gallic acid as a reductant via design of experiment strategies based on the response surface methodologies. Fractional factorial design was used in the screening stage, the Box–Behnken method was employed to model the target responses, and the optimization step was performed using the desirability function. They found that the obtained AgNPs presented continuous improvement in the reproducibility of the photophysical properties between batches compared to the synthesis methods reported in the literature. They revealed that ML integration reduced batch-to-batch variability by 20%. Intra-assays, intermediate precision tests and reproducibility tests were performed and confirmed that the different AgNP batches presented equal optical responses, average sizes and size distributions at the 95% confidence level [49]. Additionally, ML techniques are employed to analyze extensive datasets derived from earlier synthesis experiments, revealing hidden patterns that facilitate the prediction of new synthesis pathways. Machine learning (ML) plays a pivotal role in predicting the efficacy of plant extracts used in the green synthesis of AgNPs [50]. One effective approach involves using decision trees to analyze and correlate specific phytochemicals with the resulting nanoparticle size and shape. Decision trees, a type of supervised learning algorithm, can handle complex datasets by breaking down the data into smaller, more manageable subsets based on decision rules derived from the input features. In the AgNPs synthesis, these input features might include the concentration of various phytochemicals present in the plant extracts, such as flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenolic acids [45]. By training the decision tree model on experimental data, it can learn to predict which combinations and concentrations of these phytochemicals are most likely to produce nanoparticles with desired characteristics. For example, the model might reveal that higher concentrations of certain flavonoids correlate with smaller nanoparticle sizes, while specific terpenoids might influence the shape of the nanoparticles. This predictive capability not only enhances the efficiency of the synthesis process but also provides valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of green synthesis, enabling researchers to select the most effective plant extracts for producing high-quality AgNPs [45, 51].

Characterization of silver nanoparticles

Characterizing silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) requires assessment of their size, shape, surface area, and distribution, as these factors significantly influence their potential applications. Machine learning (ML) techniques enhance this process by facilitating the application of computer vision and ML in microscopy analysis, which significantly improves the identification, classification, and quantification of nanoparticles within microscopy images, such as those obtained from transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), for example, can be trained to automatically identify and measure the dimensions of AgNPs in TEM images, reducing the potential for human error and speeding up the characterization process [52]. Additionally, ML models trained on experimental datasets can predict the optical, electrical, and catalytic characteristics of AgNPs by analyzing their synthesis parameters and structural attributes. Uthayakumar et al. optimized the size of AgNPs using an artificial neural network (ANN) model, achieving an R² value of 0.92 for parameter optimization. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was also employed to conduct statistical analysis to determine the influence of process parameters on the size of the AgNP [46]. Uthayakumar, H. et al. optimized the size of AgNPs and evaluated them by using an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was also employed to conduct statistical analysis to determine the influence of the process parameters on the size of the AgNPs [47]. ML algorithms facilitate the interpretation of intricate spectroscopic data, such as UV‒Vis [53], FTIR, and Raman spectroscopy data, by establishing connections between spectral characteristics and the size, shape, and surface chemistry of nanoparticles [54]. Sahin, F., et al. studied the use of an eco-friendly preparation of a surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) substrate for the ML-assisted detection of pesticides in water. The proposed SERS platform was prepared on copy paper by reducing silver salt using the extract of the natural plant Cedruslibani. They reported that the ML-assisted detection of pesticides in water using (SERS) prepared by silver nanoparticles achieved an impressive 95% accuracy. This high level of accuracy demonstrates the effectiveness of combining ML with SERS for sensitive and reliable detection of pollutants in water. The fabricated SERS platform was characterized in detail using SEM, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. The highdensity of silver nanoparticles with an average diameter of 41 nm on the surface of the paper enabled the detection of analytes with nanomolar sensitivity. This SERS capability was used to collect Raman signals of four different pesticides in water [54, 55].

Application of silver nanoparticles

The utilization of ML in research extends the implementation of AgNPs to include AgNPs, which are extensively utilized in antimicrobial applications, and ML models can forecast the effectiveness of specific syntheses against different bacterial strains, thereby optimizing nanoparticles for both medical and industrial uses [46].

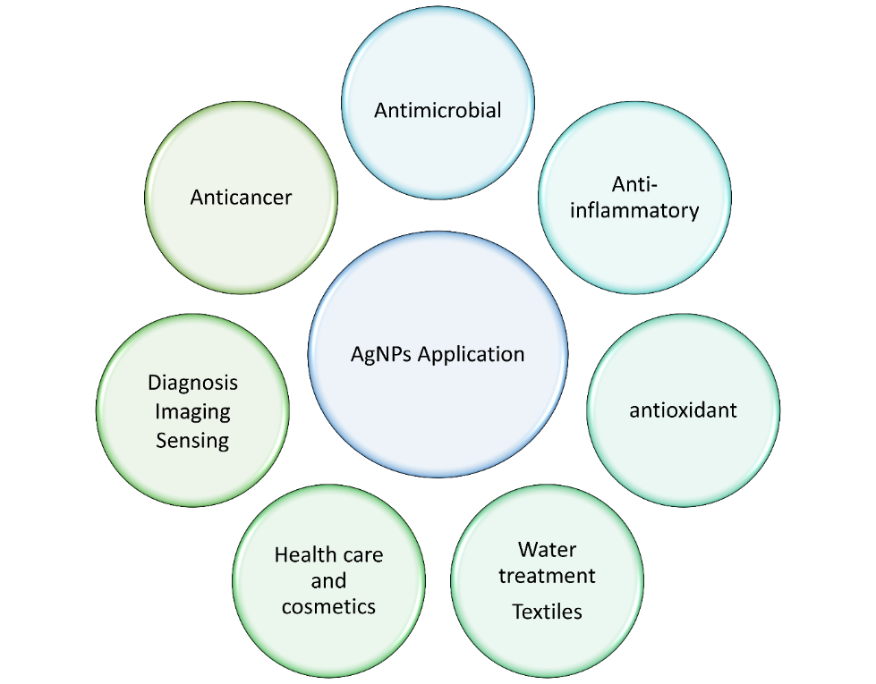

ML models are employed to forecast the catalytic activity of AgNPs in various chemical reactions, including applications in environmental remediation, such as pollutant degradation, and industrial catalysis. These models can identify correlations between the characteristics of nanoparticles and their reaction efficiency, thereby informing the development of more efficient catalysts (fig. 2) [56, 57].

Fig. 2: Illustration scheme of different applications of AgNPs

AgNPs are frequently utilized in biosensors and environmental sensors. ML techniques are employed to improve the sensitivity and specificity of these sensors by forecasting the impact of variations in AgNP size, shape, or surface modifications on their performance [58]. Machine learning (ML) provides a powerful approach for optimizing silver nanoparticle (AgNP) synthesis by analyzing the complex relationships between multiple reaction parameters and their outcomes [59]. Traditional experimental methods rely on trial and error, which can be time-consuming and inefficient. By using ML, researchers can predict optimal conditions for AgNP formation based on historical data, reducing the need for extensive laboratory work [60]. Key factors such as silver nitrate concentration, reducing agent type, pH, temperature, and reaction time significantly influence the size, shape, and stability of AgNPs [61]. ML models, including regression techniques, neural networks, and evolutionary algorithms, can identify patterns and suggest ideal synthesis conditions with high precision. This approach not only improves reproducibility but also accelerates the discovery of novel nanoparticle formulations with tailored properties for specific applications [43]. The integration of ML with real-time monitoring and automation holds great potential for further refining nanoparticle fabrication processes, leading to more efficient and scalable production methods.

Functionalization of silver nanoparticles and surface modification

ML is becoming increasingly important for the functionalization and surface modification of AgNPs. Functionalization involves the attachment of chemical or biological molecules [62, 63] to the surfaces of AgNPs to enhance their characteristics for various applications [46]. Chatterjee et al. prepared silver nanoclusters (AgNCs) and silver quantum clusters (AgQCs) via the modification of organic chelating motifs by covalent or noncovalent bonds; these nanoclusters represent an ideal type of hybrid nanomaterial for sensing materials and discussed their applications in metal ions and biomolecule sensing [64]. Similarly, Zhang X et al. synthesized hyaluronic acid-coated silver nanoparticles (HA-Ag NPs) that are spherical, ultrasmall and monodisperse and exhibited excellent long-term stability and low cytotoxicity and could be used as a nanoplatform for X-ray computed tomography (CT) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging after being radiolabeled with 99mTc [4, 65]. ML contributes to the optimization of these processes by increasing efficiency and precision and facilitating the discovery of innovative functionalization techniques. This process is essential for adjusting the properties of AgNPs, including their stability, biocompatibility, and reactivity. Support vector machines (SVMs) can be used to rank the biocompatibility of various functionalizing agents for silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). This ML model helped in selecting the most appropriate coatings based on predicted biocompatibility, ensuring the nanoparticles were suitable for applications such as imaging and drug delivery [34].

ML has enabled improvements in methods such as the determination of the most appropriate functionalizing agents, such as polymers, proteins, or small molecules, for specific applications [46, 57]. Additionally, ML algorithms are employed to predict the impact of various surface ligands or coatings on the physicochemical characteristics of AgNPs. This approach encompasses the prediction of stability across diverse environments, such as variations in pH and ionic strength, as well as within biological systems such as the bloodstream and tissues. Such predictive capabilities facilitate more precise applications in areas such as drug delivery and biosensing [66]. The surface energy of AgNPs is essential for their interactions with biological cells, other nanoparticles, and solvents. ML aids in optimizing surface modifications to regulate the aggregation, dispersion, and functionalization efficiency of AgNPs [67].

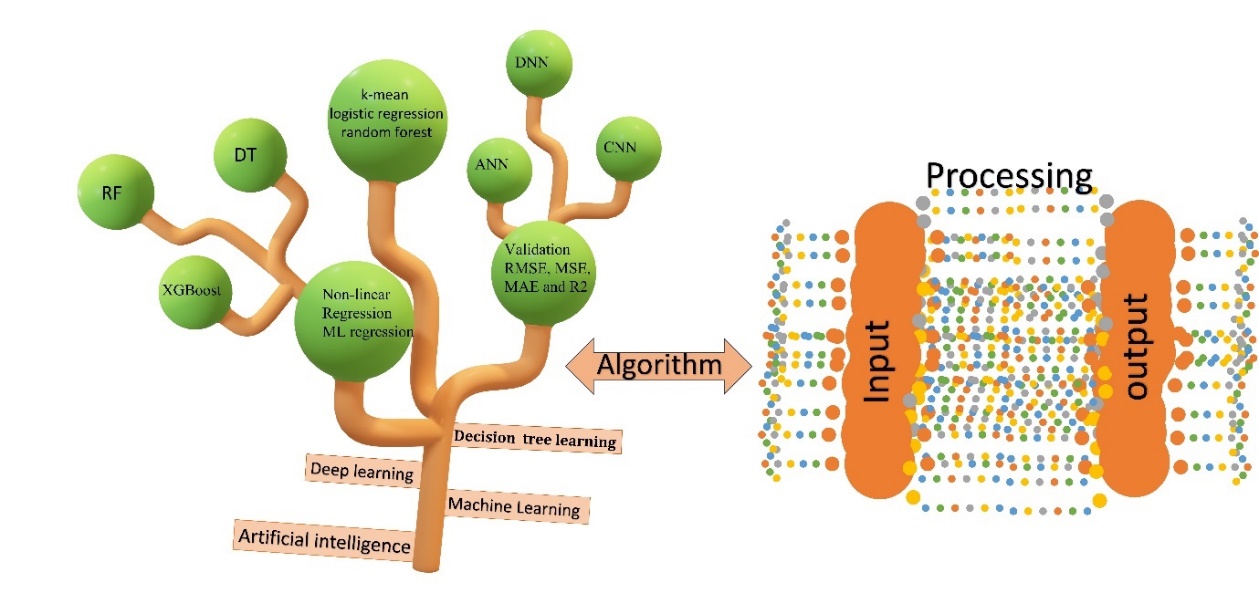

Additionally, ML plays a crucial role in identifying patterns within extensive experimental datasets, facilitating the exploration of novel functionalization strategies [68]. ML tools use extensive datasets to investigate various combinations of surface ligands or polymers that may yield distinctive surface properties. This exploration can result in novel approaches to enhancing the stability, bioavailability, or catalytic efficiency of AgNPs [69]. With the growing emphasis on sustainability, ML plays a crucial role in identifying and enhancing environmentally sustainable functionalization methods. For instance, the application of green functionalization methods using plant extracts or biomolecules can be investigated by employing ML models trained on historical experimental data (fig. 3) [70].

Accurate characterization of functionalized or surface-modified AgNPs is essential for understanding how these modifications impact their behavior in different environments. ML enhances the characterization process by two means: ML techniques, such as computer vision, can be employed to obtain microscopy images (TEM, SEM) of functionalized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), enabling researchers to efficiently evaluate surface modifications. Similarly, spectroscopy data (e. g., FTIR and Raman) pertaining to surface ligands can be analyzed by ML models to ascertain the extent of functionalization [71]. The other technique is to use ML algorithms that are trained to predict how surface modifications will affect nanoparticle interactions with their surroundings. For example, predictive models can assess how altered AgNPs engage with proteins in biological contexts or with pollutants in environmental scenarios [72]. ML helps optimize AgNP functionalization for specific applications: AgNPs are widely used for their antimicrobial properties. ML models can predict which surface modifications optimize or refine the antibacterial or antiviral efficacy of AgNPs. For example, these models recommend surface alterations that enhance the interaction with bacterial cell membranes or viral particles [73]. In nanomedicine, the functionalization of AgNPs with ligands or polymers enhances their capacity to selectively target diseased cells, such as cancer cells. ML plays a crucial role in predicting which surface modifications optimize cellular uptake, minimize toxicity, or facilitate drug release at the intended site [74].

Fig. 3: Illustration scheme of different ML types used in AgNPs good formulation prediction

Surface-modified AgNPs are used in catalysis, particularly in environmental and industrial applications. ML models are used to predict which functionalization approaches will enhance catalytic efficiency, including enhancing reaction selectivity or minimizing energy consumption during chemical transformations [75, 76].

Additionally, functionalized AgNPs are frequently employed in the development of biosensors and chemical sensors. ML assists in forecasting the impact of surface modifications on the sensitivity and selectivity of these sensors, thereby informing the design of highly precise sensing platforms [77].

Different ML techniques are employed in functionalization research: models such as decision trees, support vector machines (SVMs), and neural networks are used to predict the best functionalization agents or surface modifiers based on known datasets [78, 79]. Clustering techniques are used to group AgNPs based on their surface properties or performance in specific applications, helping to identify which functionalization methods lead to similar outcomes [80]. On the other hand, reinforcement learning helps optimize surface modification protocols by dynamically adjusting experimental conditions based on feedback from early experiments, and deep learning is useful for analyzing complex data such as microscopy images or spectroscopic signals [81].

Prediction of silver nanoparticle toxicity

The prediction of AgNP toxicity using ML approaches is a developing area in which data-driven models are utilized to evaluate the potential risks of AgNP exposure [82, 62]. ML models can facilitate the prediction of AgNP toxicity (table 3), thereby minimizing the necessity for extensive biological testing by offering toxicity forecasts prior to experimental validation [83].

Table 3: Some common ML approaches used in the prediction of silver nanoparticle toxicity include the following

| Machine learning approach | Description | Examples |

| Supervised Learning | Trained on labelled data to predict toxicity levels of new nanoparticles. | Random Forest, SVMs, Neural Networks [84] |

| Unsupervised Learning | Clustering methods identify groups of nanoparticles with similar toxicity profiles, even without labels. | K-Means, Hierarchical Clustering [70] |

| Regression Models | Predict quantitative toxicity endpoints such as IC50, cell viability, or oxidative stress levels. | Various regression techniques [69] |

| Classification Models | Categorize nanoparticles as toxic or non-toxic based on physicochemical properties. | Decision Trees, SVM, Logistic Regression [85] |

| Deep Learning | Captures complex relationships in large datasets using neural networks. | Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) [81] |

The fundamental characteristics involved in predicting the toxicity of nanoparticles generally encompass physicochemical properties, including particle size, shape, surface area, zeta potential, and aggregation state [86]. Additionally, the chemical composition of nanoparticles, such as surface coatings, ligands, and dopant elements, plays a crucial role [87, 88]. The environmental conditions, such as temperature, pH, ionic strength, and duration of exposure, are also significant [89]. Furthermore, biological interactions, including cell type, exposure dose, duration, and specific toxicity biomarkers, are essential considerations. These attributes are utilized to train models that establish correlations between the properties of nanoparticles and their toxic outcomes [48].

The application of ML in forecasting the toxicity of AgNPs has several advantages. This approach facilitates the swift evaluation of the toxicological effects of novel nanoparticles, thereby minimizing both time and financial expenditure [90]. Validation metrics, for example, stating that "ANN models achieved 85% accuracy in predicting in vivo toxicity." Furthermore, using interpretability tools like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to provide insights into the factors influencing toxicity predictions, such as identifying particle size as a dominant factor. Additionally, these models possess the ability to reveal intricate correlations between the characteristics of nanoparticles and their biological impacts, which may be challenging to identify using conventional statistical approaches. Additionally, these ML models reduce the use of animal testing for toxicity assessments.

ML provides a robust array of tools for forecasting the toxicity of AgNPs by synthesizing information from diverse sources and revealing patterns that may not be readily apparent [91]. These models can assist in the safe development of nanomaterials and reduce potential hazards linked to their application in consumer and medical products. Nevertheless, continuous enhancements in data quality, model interpretability, and generalization are crucial for broader implementation.

Challenges and future directions

The combination of ML and AgNP research presents promising prospects but also introduces several challenges [16, 92]. The following is a summary of the challenges faced and potential future directions in this developing area.

High-quality, large datasets are often required for training ML models [93]. However, obtaining reliable and standardized data on the synthesis, properties, and behavior of AgNPs is challenging due to varying experimental conditions [46]. Additionally, experimental results from different laboratories can be difficult to compare due to variability in protocols, particle sizes, surface coatings, and environmental factors [46]. Many datasets contain incomplete or biased information, which can skew ML model predictions [85].

The behavior of AgNPs is influenced by various factors, ranging from atomic interactions to the properties of bulk materials, which complicates the modeling of all pertinent factors. AgNPs exhibit size, shape, and surface-dependent properties [82]. The challenge is to account for this variability in a model that generalizes across a wide range of conditions. Additionally, simulating AgNP interactions at the atomic or molecular level often requires high-performance computing, which may be limited by certain researchers or institutions.

Determining the appropriate features for ML models is essential. In AgNP research, these features could encompass physical characteristics, environmental factors, and biological interactions, which may be challenging to quantify or may interact in nonobvious ways [94]. The development of suitable descriptors that capture the essential physics and chemistry underlying AgNP behaviors is still a growing area of research. Many researchers, as illustrated in table 4, have used data from literature as an input parameter for the ML algorithm to predict the optimum conditions and effectiveness of AgNPs.

Table 4: Examples of data collected from literature and used in machine learning for predicting optimum parameter and therapeutic effects of AgNPs

| Type of Ag NPs | Studies used | Parameter | Application | ML techniques used | Reference |

| AgNPs is developed for the energy of Fermi level | NA | Multi-structure/single-property relationship | Electron Transfer Property | k-mean, logistic regression and random forest | [95] |

| Spherical, Hexagonal, Rod, Spindle, Disc, Cubic | Different synthesis method of 60 studies | Hydrodynamic size (nm), Zeta potential, Core size (nm), exposure dose (μg/ml)duration, Surface area, Aggregation | Antibacterial | ML algorithms | [96] |

| Different types | 100 studies | Size, Temperature, Starch stabilizer, AgNO3, Concentration, Bacterial concentration | Antibacterial | ML algorithms | [50] |

| Different types | 70 studies | Hydrodynamic size (nm), Zeta potential, Core size (nm), Exposure dose (μg/ml) duration | Antibacterial/ anti-MDR |

ML | [55] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone coated AgNPs with three Sizes | 721 datasets | Dose, Type, Size, Exposure time | Soil enzyme activity | ANN, GA, RF | [34] |

| Different types | 1315 dataset from 40 studies | Types of cell lines, exposure time, particle size, hydrodynamic diameter, zeta potential, wavelength, concentration, and cell viability | Relationship between the physical parameters of NPs and their cytotoxicity | Decision Tree (DT) and Random Forest (RF) | [97] |

| Different types | 50 studies | Hydrodynamic size, Zeta potential, Core size, Shape, Exposure and duration, Surface area, Aggregation, Coating | Antibacterial Antifungal |

Four different machine-learning regression algorithms and validated the models' performance using four metrics, such as RMSE, MSE, MAE and R2 | [43] |

| Different shapes | All AgNPs produced from te year 2004 to 2022 | Reactant concentrations, Experimental conditions Physicochemical properties |

Antibacterial efficiencies and toxicological profiles | Regression machine learning algorithm | [98] |

The future of combining ML with silver AgNP research promises transformative advancements in nanotechnology, with the potential to revolutionize both scientific understanding and practical applications [99, 100]. As the availability of data increases and models become more sophisticated, ML will enable the rapid and accurate prediction of AgNP toxicity, environmental impact, and efficacy under real-world conditions. Multi-omics integration, ecotoxicological models, and hybrid approaches combining ML with physics-based simulations will allow more precise insights into how AgNPs interact with biological systems and ecosystems [101]. Additionally, the development of explainable AI will enhance model interpretability, allowing researchers to understand the underlying mechanisms of nanoparticle toxicity [102]. In the long term, ML-driven personalized risk assessments, automated nanoparticle design, and sustainable manufacturing practices will emerge, minimizing environmental damage and enhancing the safety of nanomaterials across a range of industries, including medicine, electronics, and consumer products. Finally, implementing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles is crucial to ensure high-quality, standardized datasets for training ML models. Leveraging cloud computing resources can effectively handle the computational demands of simulating AgNP interactions and processing large datasets. Additionally, utilizing synthetic data generation techniques helps balance datasets, address data scarcity, and improve model robustness [103, 104]. Future research should focus on integrating explainable AI techniques, such as LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), to enhance the transparency and interpretability of ML models used in AgNP research. Additionally, the development of ML-DFT (Density Functional Theory) hybrid models can provide more accurate predictions by combining the strengths of machine learning and quantum mechanical simulations. To support collaborative research and reproducibility, establishing open-source repositories for sharing datasets, models, and code is essential [76].

CONCLUSION

Integrating machine learning with silver nanoparticle research holds tremendous promise for advancing our understanding and application of these materials. However, addressing challenges such as data quality, model interpretability, and interdisciplinary collaboration will be key to realizing the full potential of this approach. Future advancements in explainable AI, high-throughput data generation, and hybrid modeling techniques will further enhance the capabilities of ML in nanoscience.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Zainab Lafi1*, Idea, Writing about Silver nanoparticles, Drawing, editing and validation

Sina Matalqah1, Writing about Silver nanoparticles, editing and validation

Sherine Asha2, Writing drafts about machine learning and constructing tables

Hala Mhaidat3, Writing drafts about machine learning and constructing tables

Nisreen Asha4, Writing drafts about machine learning and drawing images

This review article synthesizes previously published research and does not involve any new studies with human participants or animals conducted by the authors. All sources referenced in this manuscript have adhered to the respective ethical guidelines and standards of their original publications.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Zhang XF, Liu ZG, Shen W, Gurunathan S. Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization properties, applications and therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(9):1534. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091534, PMID 27649147.

Kalantari K, Mostafavi E, Afifi AM, Izadiyan Z, Jahangirian H, Rafiee Moghaddam R. Wound dressings functionalized with silver nanoparticles: promises and pitfalls. Nanoscale. 2020;12(4):2268-91. doi: 10.1039/c9nr08234d, PMID 31942896.

Eby DM, Luckarift HR, Johnson GR. Hybrid antimicrobial enzyme and silver nanoparticle coatings for medical instruments. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2009;1(7):1553-60. doi: 10.1021/am9002155, PMID 20355960.

Matalqah S, Lafi Z, Asha SY. Hyaluronic acid in nanopharmaceuticals: an overview. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46(9):10444-61. doi: 10.3390/cimb46090621, PMID 39329973.

Jain J, Arora S, Rajwade JM, Omray P, Khandelwal S, Paknikar KM. Silver nanoparticles in therapeutics: development of an antimicrobial gel formulation for topical use. Mol Pharm. 2009;6(5):1388-401. doi: 10.1021/mp900056g, PMID 19473014.

Otunola GA, Afolayan AJ. In vitro antibacterial, antioxidant and toxicity profile of silver nanoparticles green synthesized and characterized from aqueous extract of a spice blend formulation. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2018;32(3):724-33. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2018.1448301.

Badnore AU, Sorde KI, Datir KA, Ananthanarayan L, Pratap AP, Pandit AB. Preparation of antibacterial peel-off facial mask formulation incorporating biosynthesized silver nanoparticles. Appl Nanosci. 2019;9(2):279-87. doi: 10.1007/s13204-018-0934-2.

Zhao Y, Zeng Q, Wu F, Li J, Pan Z, Shen P. Novel naproxen peptide conjugated amphiphilic dendrimer self-assembly micelles for targeting drug delivery to osteosarcoma cells. RSC Adv. 2016;6(65):60327-35. doi: 10.1039/C6RA15022E.

Ong C, Lim JZ, Ng CT, Li JJ, Yung LY, Bay BH. Silver nanoparticles in cancer: therapeutic efficacy and toxicity. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20(6):772-81, PMID 23298139.

Prasher P, Sharma M, Mudila H, Gupta G, Sharma AK, Kumar D. Emerging trends in clinical implications of bio-conjugated silver nanoparticles in drug delivery. Colloid and Interface Science Communications. 2020;35:100244. doi: 10.1016/j.colcom.2020.100244.

Mandal AK, JO N. Silver nanoparticles as drug delivery vehicle against infections. Glob J Nanomed. 2017;3(2):1-4. doi: 10.19080/GJN.2017.03.555607.

Patra S, Mukherjee S, Barui AK, Ganguly A, Sreedhar B, Patra CR. Green synthesis characterization of gold and silver nanoparticles and their potential application for cancer therapeutics. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2015;53:298-309. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.04.048, PMID 26042718.

Mo L, Guo Z, Yang L, Zhang Q, Fang Y, Xin Z. Silver nanoparticles based ink with moderate sintering in flexible and printed electronics. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2124. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092124, PMID 31036787.

Sudarman F, Shiddiq M, Armynah B, Tahir DJ. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) synthesis methods as heavy-metal sensors: a review. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. 2023;20(8):9351-68. doi: 10.1007/s13762-022-04745-0.

Khalil AM, Hassan ML, Ward AA. Novel nanofibrillated cellulose/polyvinylpyrrolidone/silver nanoparticles films with electrical conductivity properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;157:503-11. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.10.008, PMID 27987955.

Yu Y, Zhou Z, Huang G, Cheng H, Han L, Zhao S. Purifying water with silver nanoparticles (AgNPs)-incorporated membranes: recent advancements and critical challenges. Water Res. 2022;222:118901. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118901, PMID 35933814.

Zahoor M, Nazir N, Iftikhar M, Naz S, Zekker I, Burlakovs J. A review on silver nanoparticles: classification various methods of synthesis and their potential roles in biomedical applications and water treatment. Water. 2021;13(16):2216. doi: 10.3390/w13162216.

Rani P, Kumar V, Singh PP, Matharu AS, Zhang W, Kim KH. Highly stable AgNPs prepared via a novel green approach for catalytic and photocatalytic removal of biological and non-biological pollutants. Environ Int. 2020;143:105924. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105924, PMID 32659527.

Greener JG, Kandathil SM, Moffat L, Jones DT. A guide to machine learning for biologists. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(1):40-55. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00407-0, PMID 34518686.

Karniadakis GE, Kevrekidis IG, Lu L, Perdikaris P, Wang S, Yang LJ. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat Rev Phys. 2021;3(6):422-40. doi: 10.1038/s42254-021-00314-5.

He L, Bai L, Dionysiou DD, Wei Z, Spinney R, Chu C. Applications of computational chemistry, artificial intelligence and machine learning in aquatic chemistry research. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2021;426:131810. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.131810.

Fantin Irudaya Raj E, Balaji M. Application of deep learning and machine learning in pattern recognition. Advance concepts of image processing and pattern recognition: an effective solution for global challenges: springer; 2022. p. 63-89.

Paullada A, Raji ID, Bender EM, Denton E, Hanna AJ. Data and its (dis)contents: a survey of dataset development and use in machine learning research. Patterns (N Y). 2021;2(11):100336. doi: 10.1016/j.patter.2021.100336, PMID 34820643.

Libbrecht MW, Noble WS. Machine learning applications in genetics and genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16(6):321-32. doi: 10.1038/nrg3920, PMID 25948244.

Baqui PO, Marra V, Casarini L, Angulo R, Diaz Garcia LA, Hernandez Monteagudo C. The miniJPAS survey: star galaxy classification using machine learning. A&A. 2021;645:A87. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202038986.

Artrith N, Butler KT, Coudert FX, Han S, Isayev O, Jain A. Best practices in machine learning for chemistry. Nat Chem. 2021;13(6):505-8. doi: 10.1038/s41557-021-00716-z, PMID 34059804.

Braca P, Millefiori LM, Aubry A, Marano S, De Maio A, Willett PJ. Statistical hypothesis testing based on machine learning: large deviations analysis. IEEE Open Journal of Signal Processing. 2022;3:464-95.

Sarker IH. Machine learning: algorithms real world applications and research directions. SN Comput Sci. 2021;2(3):160. doi: 10.1007/s42979-021-00592-x.

Mekki Berrada F, Ren Z, Huang T, Wong WK, Zheng F, Xie J. Two-step machine learning enables optimized nanoparticle synthesis. NPJ Comput Mater. 2021;7(1):55. doi: 10.1038/s41524-021-00520-w.

Dong B, Xue N, Mu G, Wang M, Xiao Z, Dai L. Synthesis of monodisperse spherical AgNPs by ultrasound intensified lee-meisel method and quick evaluation via machine learning. Ultrason Sonochem. 2021;73:105485. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105485, PMID 33588207.

Mathumathi M, Vetriselvi T, Matheswaran P, Nandhini R, Selvi A. Silver nano-particles size prediction using deep learning model with green method. Mater Today Proc. 2022;69:1193-9. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2022.08.253.

Kashiwagi T, Sue K, Takebayashi Y, Ono T. High-throughput synthesis of silver nanoplates and optimization of optical properties by machine learning. Chem Eng Sci. 2022;262:118009. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2022.118009.

Nathanael K, Cheng S, Kovalchuk NM, Arcucci R, Simmons MJ. Optimization of microfluidic synthesis of silver nanoparticles: a generic approach using machine learning. Chem Eng Res Des. 2023;193:65-74. doi: 10.1016/j.cherd.2023.03.007.

Zhang Z, Lin J, Chen Z. Predicting the effect of silver nanoparticles on soil enzyme activity using the machine learning method: type size dose and exposure time. J Hazard Mater. 2023;457:131789. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131789, PMID 37301072.

Prasad A, Santra TS, Jayaganthan R. A study on prediction of size and morphology of ag nanoparticles using machine learning models for biomedical applications. Metals. 2024;14(5):539. doi: 10.3390/met14050539.

Kourou K, Exarchos TP, Exarchos KP, Karamouzis MV, Fotiadis DI, Journal SB. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2014.11.0052015;13:8-17.

Vu MT, Adalı T, Ba D, Buzsaki G, Carlson D, Heller K. A shared vision for machine learning in neuroscience. J Neurosci. 2018;38(7):1601-7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0508-17.2018, PMID 29374138.

Xie Y, Sattari K, Zhang C, Lin J. Toward autonomous laboratories: convergence of artificial intelligence and experimental automation. Progress in Materials Science. 2023 Feb;132:101043. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2022.101043.

Siau K, Wang W. Building trust in artificial intelligence machine learning and robotics. Cutter Business Technology Journal. 2018;31(2):47-53.

Peng J, Han H, Yi Y, Huang H, Xie LJ. Machine learning and deep learning modeling and simulation for predicting. Chemosphere. 2022 Dec;308(Pt 1):136353. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136353.

Pineau J, Vincent Lamarre P, Sinha K, Lariviere V, Beygelzimer A, D Alche Buc F. Improving reproducibility in machine learning research (a report from the neurips 2019 reproducibility program). Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2021;22(164):1-20.

Huang G, Guo Y, Chen Y, Nie Z. Application of machine learning in material synthesis and property prediction. Materials (Basel). 2023;16(17):5977. doi: 10.3390/ma16175977, PMID 37687675, PMCID PMC10488794.

Mary P, Mujeeb A. A machine learning framework for the prediction of antibacterial capacity of silver nanoparticles. Nano Express. 2024;5(2):025022. doi: 10.1088/2632-959X/ad4c80.

Findlay MR, Freitas DN, Mobed Miremadi M, Wheeler KE. Machine learning provides predictive analysis into silver nanoparticle protein corona formation from physicochemical properties. Environ Sci Nano. 2018;5(1):64-71. doi: 10.1039/C7EN00466D, PMID 29881624.

Rufina R, DJ, Uthayakumar H, Thangavelu P. Prediction of the size of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using RSM-ANN-LM hybrid modeling approach. Chem Phys Impact. 2023;6:100231. doi: 10.1016/j.chphi.2023.100231.

Furxhi I, Faccani L, Zanoni I, Brigliadori A, Vespignani M, Costa AL. Design rules applied to silver nanoparticles synthesis: a practical example of machine learning application. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2024;25:20-33. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2024.02.010, PMID 38444982.

Uthayakumar H, Thangavelu P. Prediction of the size of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using RSM-ANN-LM hybrid modeling approach. Chemical Physics Impact. 2023 Jun;6:100231. doi: 10.1016/j.chphi.2023.100231.

Alshaer W, Nsairat H, Lafi Z, Hourani OM, Al Kadash A, Esawi E. Quality by design approach in liposomal formulations: robust product development. Molecules. 2022;28(1):10. doi: 10.3390/molecules28010010, PMID 36615205.

Nunez RN, Veglia AV, Pacioni NL. Improving reproducibility between batches of silver nanoparticles using an experimental design approach. Microchemical Journal. 2018;141:110-7. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2018.05.017.

Saadat A, Dehghani Varniab A, Madani SM. Prediction of the antibacterial activity of the green synthesized silver nanoparticles against gram negative and positive bacteria by using machine learning algorithms. J Nanomater. 2022;2022(1):4986826. doi: 10.1155/2022/4986826.

Mungwari CP, King'ondu CK, Sigauke P, Obadele BA. Conventional and modern techniques for bioactive compounds recovery from plants. Sci Afr. 2025;27:e02509. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2024.

Lee B, Yoon S, Lee JW, Kim Y, Chang J, Yun J. Statistical characterization of the morphologies of nanoparticles through machine learning based electron microscopy image analysis. ACS Nano. 2020;14(12):17125-33. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c06809, PMID 33231065.

Klinavicius T, Khinevich N, Tamuleviciene A, Vidal L, Tamulevicius S, Tamulevicius T. Deep learning methods for colloidal silver nanoparticle concentration and size distribution determination from UV–vis extinction spectra. J Phys Chem C. 2024;128(23):9662-75. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.4c02459.

Sahin F, Celik N, Camdal A, Sakir M, Ceylan A, Ruzi M. Machine learning assisted pesticide detection on a flexible surface enhanced raman scattering substrate prepared by silver nanoparticles. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2022;5(9):13112-22. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.2c02897.

Hassan SA, Ghadam P, editors. Random forest model resolves the challenges against multi-drug resistant bacteria by AgNPs. Chem Process. 2023;9:2-4. doi: 10.3390/ecsoc-27-16150.

Khan MS, Sidek LM, Kumar P, Alkhadher SA, Basri H, Zawawi MH. Machine learning based model to predict catalytic performance on removal of hazardous nitrophenols and azo dyes pollutants from wastewater. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;278(3):134701. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134701, PMID 39151852.

Ibrahim S, Ahmad Z, Manzoor MZ, Mujahid M, Faheem Z, Adnan AJ. Optimization for biogenic microbial synthesis of silver nanoparticles through response surface methodology, characterization their antimicrobial antioxidant and catalytic potential. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):770. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80805-0, PMID 33436966.

Ramalingam M, Jaisankar A, Cheng L, Krishnan S, Lan L, Hassan A. Impact of nanotechnology on conventional and artificial intelligence based biosensing strategies for the detection of viruses. Discov Nano. 2023;18(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s11671-023-03842-4, PMID 37032711.

Jamkhande PG, Ghule NW, Bamer AH, Kalaskar MG. Metal nanoparticles synthesis: an overview on methods of preparation advantages and disadvantages and applications. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2019;53:101174. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101174.

Karimadom BR, Kornweitz H. Mechanism of producing metallic nanoparticles with an emphasis on silver and gold nanoparticles using bottom-up methods. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2968. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102968, PMID 34067624.

Sarkar A, Kapoor S, Mukherjee T. Synthesis and characterisation of silver nanoparticles in viscous solvents and its transfer into non-polar solvents. Res Chem Intermed. 2010;36(4):411-21. doi: 10.1007/s11164-010-0151-4.

Lafi Z, Alshaer W, Hatmal MM, Zihlif M, Alqudah DA, Nsairat H. Aptamer-functionalized pH-sensitive liposomes for a selective delivery of echinomycin into cancer cells. RSC Adv. 2021;11(47):29164-77. doi: 10.1039/d1ra05138e, PMID 35479561, PMCID PMC9040599.

Al Azzawi H, Alshaer W, Esawi E, Lafi Z, Abuarqoub D, Zaza R. Multifunctional nanoparticles recruiting hyaluronic acid ligand and polyplexes containing low molecular weight protamine and ATP-Sensitive DNA motif for doxorubicin delivery. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022;69:103169. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103169.

Chatterjee S, Lou XY, Liang F, Yang YW. Surface functionalized gold and silver nanoparticles for colorimetric and fluorescent sensing of metal ions and biomolecules. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2022;459:214461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214461.

Zhang X, Yao M, Chen M, Li L, Dong C, Hou Y. Hyaluronic acid coated silver nanoparticles as a nanoplatform for in vivo imaging applications. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(39):25650-3. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b08166, PMID 27645123.

Mohseni Dargah M, Falahati Z, Dabirmanesh B, Nasrollahi P, Khajeh K. Machine learning in surface plasmon resonance for environmental monitoring. In: Artificial intelligence and data science in environmental sensing. Elsevier; 2022. p. 269-98. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-90508-4.00012-5.

Rezic I, Somogyi Skoc MJ. Computational methodologies in synthesis preparation and application of antimicrobial polymers biomolecules and nanocomposites. Polymers (Basel). 2024;16(16):2320. doi: 10.3390/polym16162320, PMID 39204538.

Matalqah S, Lafi Z, Mhaidat Q, Asha N, Yousef Asha S. Applications of machine learning in liposomal formulation and development. Pharm Dev Technol. 2025;30(1):126-36. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2024.2448777.

Jia Y, Hou X, Wang Z, Hu X. Machine learning boosts the design and discovery of nanomaterials. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 2021;9(18):6130-47. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c00483.

Konstantopoulos G, Koumoulos EP, Charitidis CA. Digital innovation enabled nanomaterial manufacturing; machine learning strategies and green perspectives. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2022;12(15):2646. doi: 10.3390/nano12152646, PMID 35957077.

Bekoz Ullen N, Karabulut G. Karakus SJJoME, performance. Assessing the surface properties of plant extract-based silver nanoparticle coatings on 17-4 PH stainless steel foams using artificial intelligence-supported RGB analysis: a comparative study. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2023;32(23):10637-54. doi: 10.1007/s11665-023-08322-5.

Winkler DA, Burden FR, Yan B, Weissleder R, Tassa C, Shaw S. Modelling and predicting the biological effects of nanomaterials. SAR QSAR Environ Res. 2014;25(2):161-72. doi: 10.1080/1062936X.2013.874367, PMID 24625316.

Mirzaei M, Furxhi I, Murphy F, Mullins M. A machine learning tool to predict the antibacterial capacity of nanoparticles. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021;11(7):1774. doi: 10.3390/nano11071774, PMID 34361160.

Alavi M, Kowalski R, Capasso R, Douglas Melo Coutinho H, Rose Alencar De Menezes. Various novel strategies for functionalization of gold and silver nanoparticles to hinder drug resistant bacteria and cancer cells. Micro Nano Bio Aspects. 2022;1(1):38-48. doi: 10.22034/mnba.2022.152629.

Yang Y, Wang K, Liu X, Xu C, You Q, Zhang Y. Environmental behavior of silver nanomaterials in aquatic environments: an updated review. The Science of the Total Environment. 2023;907(26)167861. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167861.

Oluwagbade E. Integrating explainable AI techniques to enhance transparency in predictive maintenance models; 2025.

Tun WS, Talodthaisong C, Daduang S, Daduang J, Rongchai K, Patramanon R. A machine learning colorimetric biosensor based on acetylcholinesterase and silver nanoparticles for the detection of dichlorvos pesticides. Mater Chem Front. 2022;6(11):1487-98. doi: 10.1039/D2QM00186A.

Prasad A, Santra TS, Jayaganthan RJ. A study on prediction of size and morphology of ag nanoparticles using machine learning models for biomedical applications. Metals. 2024;14(5):539. doi: 10.3390/met14050539.

Yaqub ZT, Oboirien BO. Machine learning applications for nano-synthesized materials production and utilization. In: Nanomaterials for sustainable hydrogen production and storage. CRC Press; 2024. p. 123-35. doi: 10.1201/9781003371007-7.

Shrivas K, Wu HF. Applications of silver nanoparticles capped with different functional groups as the matrix and affinity probes in surface-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight and atmospheric pressure matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization ion trap mass spectrometry for rapid analysis of sulfur drugs and biothiols in human urine. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008;22(18):2863-72. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3681.

Tao H, Wu T, Aldeghi M, Wu TC, Aspuru Guzik A, Kumacheva E. Nanoparticle synthesis assisted by machine learning. Nature Reviews Materials. 2021;6(8):701-16. doi: 10.1038/s41578-021-00337-5.

Verma SK, Nandi A, Simnani FZ, Singh D, Sinha A, Naser SS. In silico nanotoxicology: the computational biology state of art for nanomaterial safety assessments. Materials & Design. 2023;235:112452. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112452.

Mao BH, Luo YK, Wang BJ, Chen CW, Cheng FY, Lee YH. Use of an in silico knowledge discovery approach to determine mechanistic studies of silver nanoparticles induced toxicity from in vitro to in vivo. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2022;19(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12989-022-00447-0, PMID 35031062.

Masarkar A, Maparu AK, Nukavarapu YS, Rai B. Predicting cytotoxicity of nanoparticles: a meta-analysis using machine learning. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2024;7(17):19991-20002. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.4c02269.

Bilgi E, Karakus CO. Machine learning-assisted prediction of the toxicity of silver nanoparticles: a meta-analysis. Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 2023;25(8):157. doi: 10.1007/s11051-023-05806-2.

Turan NB, Erkan HS, Engin GO, Bilgili MS. Nanoparticles in the aquatic environment: usage properties transformation and toxicity a review. 2019;130:238-49. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2019.08.014.

Fahmy HM, Mosleh AM, Elghany AA, Shams Eldin E, Abu Serea ES, Ali SA. Coated silver nanoparticles: synthesis cytotoxicity and optical properties. RSC Adv. 2019;9(35):20118-36. doi: 10.1039/c9ra02907a, PMID 35514687.

Alshaer W, Zraikat M, Amer A, Nsairat H, Lafi Z, Alqudah DA. Encapsulation of echinomycin in cyclodextrin inclusion complexes into liposomes: in vitro anti-proliferative and anti-invasive activity in glioblastoma. RSC Adv. 2019;9(53):30976-88. doi: 10.1039/c9ra05636j, PMID 35529392.

Reidy B, Haase A, Luch A, Dawson KA, Lynch IJ. Mechanisms of silver nanoparticle release transformation and toxicity: a critical review of current knowledge and recommendations for future studies and applications. Materials (Basel). 2013;6(6):2295-350. doi: 10.3390/ma6062295, PMID 28809275.

Desai N, Pande S, Salave S, Singh TR, Vora LK. Antitoxin nanoparticles: design considerations functional mechanisms and applications in toxin neutralization. Drug Discovery Today. 2024;29(8):104060. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2024.104060.

Weldon BA. Tarnished: the toxic potential of silver nanoparticles; 2016.

Leong SX, Leong YX, Koh CS, Tan EX, Nguyen LB, Chen JR. Emerging nanosensor platforms and machine learning strategies toward rapid point-of-need small molecule metabolite detection and monitoring. Chem Sci. 2022;13(37):11009-29. doi: 10.1039/d2sc02981b, PMID 36320477.

Lwakatare LE, Raj A, Crnkovic I, Bosch J, Olsson HH. Large-scale machine learning systems in real-world industrial settings: a review of challenges and solutions. Information and Software Technology. 2020;127:106368. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2020.106368.

Hughes A, Liu Z, Reeves ME. PAME: plasmonic assay modeling environment. PeerJ Computer Science. 2015;1:e17. doi: 10.7717/peerj-cs.17.

Sun B, Fernandez M, Barnard AS. Machine learning for silver nanoparticle electron transfer property prediction. J Chem Inf Model. 2017;57(10):2413-23. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.7b00272, PMID 28938072.

Mirzaei M, Furxhi I, Murphy F, Mullins M. A machine learning tool to predict the antibacterial capacity of nanoparticles. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021;11(7):1774. doi: 10.3390/nano11071774, PMID 34361160.

Desai AS, Ashok A, Edis Z, Bloukh SH, Gaikwad M, Patil R. Meta-analysis of cytotoxicity studies using machine learning models on physical properties of plant extract derived silver nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):4220. doi: 10.3390/ijms24044220, PMID 36835640, PMCID PMC9966579.

Furxhi I, Faccani L, Zanoni I, Brigliadori A, Vespignani M, Costa AL. Design rules applied to silver nanoparticles synthesis: a practical example of machine learning application. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2024;25:20-33. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2024.02.010, PMID 38444982, PMCID PMC10914561.

Kant K, Beeram R, Cabaleiro LG, Cao Y, Quesada Gonzalez D, Guo H. Road map for plasmonic nanoparticle sensors: current progress challenges and future prospects. Nanoscale Horizons. 2024 Nov 19;9(12):2085-166. doi: 10.1039/d4nh00226a.

Tovar Lopez FJ. Recent progress in micro and nanotechnology enabled sensors for biomedical and environmental challenges. Sensors (Basel). 2023;23(12):5406. doi: 10.3390/s23125406, PMID 37420577.

Bedia C. Metabolomics in environmental toxicology: applications and challenges. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry. 2022;34:e00161. doi: 10.1016/j.teac.2022.e00161.

Jia X, Wang T, Zhu HJ. Advanc Comp Toxicol Interpretable Mach Learn. Environmental Science & Technology. 2023;57(46):17690-706. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.3c00653.

Singh AV, Ansari MH, Rosenkranz D, Maharjan RS, Kriegel FL, Gandhi K. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in computational nanotoxicology: unlocking and empowering nanomedicine. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9(17):e1901862. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201901862, PMID 32627972.

Shatkin JA, Ong K, Ede JJ. Minimizing risk: an overview of risk assessment and risk management of nanomaterials protocols and industrial innovations. Metrology and Standardization of Nanotechnology. 2017:381-408. doi: 10.1002/9783527800308.ch24.