Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 277-289Original Article

DETERMINATION OF PROTEIN TRANSPORTERS FOR THE ABSORPTION OF ZN-PEPTIDES FROM HOLOTHURIA SCABRA THROUGH NETWORK PHARMACOLOGY WITH MOLECULAR SIMULATION APPROACH

GITA SYAHPUTRA1,2* , MELVA LOUISA3, MASTERIA YUNOVILSA PUTRA1, RINA WIJAYANTI2, NUNIK GUSTINI1, A’LIYATUR ROSYIDAH1

1Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Islam Sultan Agung, Sermarang, 50112, Indonesia.2Research Center for Vaccine and Drugs, National Research and Innovation Agency, Bogor-16911, Indonesia. 3Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta-10430, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Gita Syahputra; *Email: gitasyahputra@unissula.ac.id, gita002@brin.go.id

Received: 14 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 08 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to identify key genes and proteins involved in zinc homeostasis and to evaluate the potential of sea cucumber (Holothuria scabra) peptides as zinc-binding agents targeting the zinc transporter protein ZIP2, which plays a central role in zinc deficiency.

Methods: Bioinformatics analyses were conducted to identify genes associated with zinc deficiency and related pathways. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks were used to determine key target genes involved in zinc homeostasis. Molecular docking simulations assessed the binding affinity of six H. scabra peptides to the ZIP2 protein compared with ZnSO₄ and Zn-carnosine as controls. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, including RMSD and RMSF analyses, were performed to evaluate the stability and interaction dynamics of the most promising peptide–protein complex.

Results: A total of 90 target genes associated with zinc deficiency were identified, involving multiple biological processes and pathways. Ten key protein-coding genes were found to play significant roles in zinc homeostasis, including nine zinc transporter genes (SLC39A2, SLC30A3, SLC39A4, SLC30A2, SLC30A4, SLC39A13, SLC29A8, TEX11, and C904f84) and one zinc-sensing receptor gene (GPR39). PPI network analysis revealed SLC39A2 (ZIP2) as the central gene in zinc homeostasis. Among the six tested peptides, the PY peptide exhibited the most favorable binding affinity to ZIP2 (-6.1 kcal/mol), surpassing both control compounds. MD simulations indicated stable interaction of the PY peptide at the active site of ZIP2 throughout the observation period.

Conclusion: The study highlights SLC39A2 (ZIP2) as a pivotal protein in zinc homeostasis and identifies the PY peptide from H. scabra as a promising zinc-binding agent. These in silico findings provide a foundation for future in vitro and in vivo investigations into potential peptide-based interventions for zinc deficiency.

Keywords: Collagen peptides, Holothuria scabra, Intestines, Molecular simulation, Zinc transporters

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55054 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Zinc deficiency is caused by the insufficient intake or dysregulation of zinc metabolism. Zinc deficiency causes a variety of health issues in humans, including growth retardation, cognitive impairment, immune system dysfunction, neurological dysfunction, increased oxidative stress, and cytokine production [1]. Due to the high demand for this micromineral during growth and development, children are particularly vulnerable to zinc deficiency. Long-term zinc inadequacy damages children’s health, resulting in growth retardation [2–7]. Therefore, zinc deficiency is regarded as a major health problem worldwide, especially in developing countries, highlighted by the World Health Organization [8, 9]. Zinc deficiency related to nutrition insufficiency, however, is more often the result of inadequate absorption of zinc from the diet. The human body’s zinc homeostasis is mostly governed by intestinal absorption [10].

Zinc transport was initially thought to occur via co-transport with aspartate, cysteine, and histidine, which shows the highest absorption concentration [11]. Zinc transport-specific genes in cell membranes were later discovered in mammals [12]. In mammals, zinc transporters are classified into two types: ZIP (Zrt-and Irt-like proteins and SLC39A, which increases zinc levels in the cytosol) and ZNT (solute-linked carrier 30 and SLC30A, which decreases zinc levels in the cytosol). In addition, metallothionein is involved in zinc transport in a cellular context. These genes play specific roles in zinc transport in specific organs of the human body, particularly the digestive tract, which is the primary location of zinc deficiency conditions [13]. Although zinc is absorbed throughout the small intestine, the primary site of intestinal absorption and the main type of transporters in humans are still debated.

Zinc mineral supplementation therapy is a global strategy employed by the Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization to address mineral deficiency [14]. However, both organic and inorganic zinc supplements have drawbacks, including the risk of gastrointestinal irritation, a lack of absorption potency, and low bioavailability [14, 15]. As a result, peptide-bound zinc supplementation of peptides was developed, resulting in a third-generation zinc supplement that is expected to outperform the previous generations [2]. Targeted therapy on transporter proteins in the digestive tract is expected to be effective in zinc deficiency therapy [16]. While general classes of zinc transporters are known, detailed understanding of specific transporters critical for peptide-bound zinc absorption in the intestine remains limited, justifying the computational approach to identify and characterize these interactions. Therefore, more studies are needed to ensure that peptide-bound zinc supplementation therapy is effective.

Thus, peptide-bound zinc supplementation of peptides is carried out, and a third-generation zinc supplement is expected to improve the previous generation of zinc supplements [2]. Peptide-bound zinc’s solubility and stability in the intestinal tract are increasing, and these factors make zinc bioavailability beneficial and harmless to organisms [17]. Related studies have been published on the discovery of collagen peptides in nature in several food sources, such as whey [18], octopus [17], sesame [19], oyster [20], and fish by-products [21]. In a previous study, peptides in these food sources were used for zinc binding, and the peptides reported from sea cucumber were WLTPTYPE from whole protein in sea cucumber [22]. Our previous research has successfully mapped the potential of secondary metabolites from Holothuria scabra as phytate inhibitors of the zinc transporter [23]. In addition, we report on the potential as a zinc chelating peptide by ex vivo evaluation test, which will be discussed in silico in this paper [24]. In addition, a human zinc transporter protein model that is not yet available in protein databases has been successfully homology modelled and characterized for use as a molecular simulation of drug candidate compounds [25]. However, more research on the peptides from sea cucumber collagen is needed to discover their bioactivity.

The most recent bioinformatics techniques for studying drug and protein or transporter interactions are network pharmacology and molecular simulation approaches. Network pharmacology techniques are used to collect specific gene and protein data from databases, particularly for proteins located in the intestines, thereby identifying transporters in zinc absorption. Furthermore, the bioinformatics approach can provide a scientific foundation for predicting the mechanism of action of peptide-bound zinc therapy against specific transporters. The present study examined the molecular interactions between collagen peptides from sea sand cucumbers H. scabra and target transporters affecting zinc absorption in the intestine in silico.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of target transporters in zinc absorption

The DisGeNET database (www.disgenet.org) was utilized to determine the target gene encoding proteins that affect zinc deficiency. DisGeNET is a database for obtaining information about the relationships between genes and certain diseases. The keywords used were “zinc deficiency (CUI: C0235950)”. Ninety genes that affect zinc deficiency were obtained. All obtained genes were downloaded in xlsx format. Metascape was used to analyze the pathways from 90 target gene-encoding proteins that affect “zinc deficiency” [26].

Protein-protein network constructions in zinc deficiency

The STRING database (www.string-db.org) was utilized to predict the network construction and protein-protein interactions with the highest confidence (0.900). In addition, for visualization, we used Cytoscape 3.9.0 (www.cytoscape.org) on the 90 genes obtained from DisGeNET. As for the topology calculation, the CytoNCA tool on Cytoscape was used, and the CytoCluster tool was used to divide genes based on their clusters. The topology and cluster analysis of the zinc transporter protein were used to determine the genes with the most significant influences on zinc deficiency [26, 27].

Pathway in target-disease and the target-pathway network

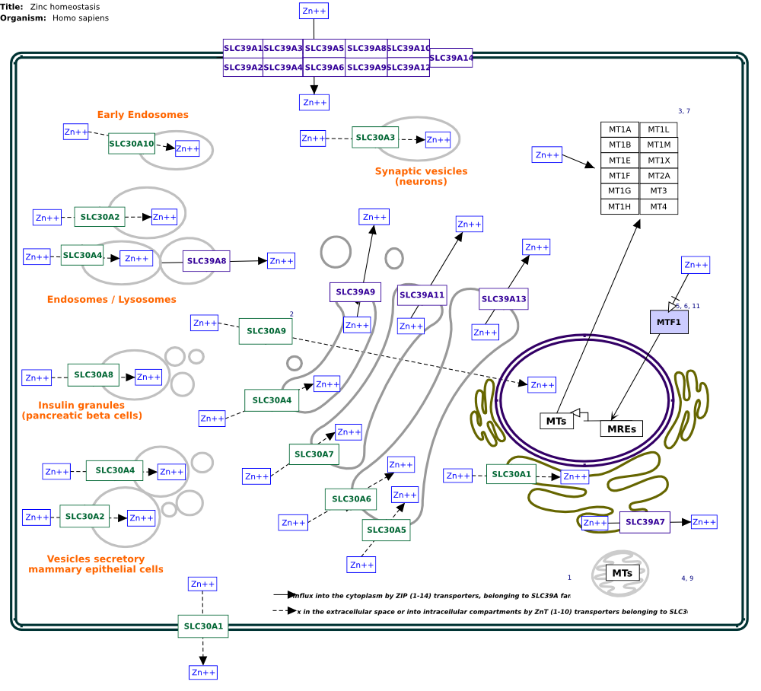

Proteins with the best topology analysis results in the zinc transporter cluster were further examined with gene ontology (GO) analysis using ShinnyGO 0.82 (https://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/database), with the analyzed components being biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. As for pathway visualization using wikipathways (www.wikipathways.org) with the keyword “zinc homeostasis” [27].

Peptides isolated from Holothuria scabra

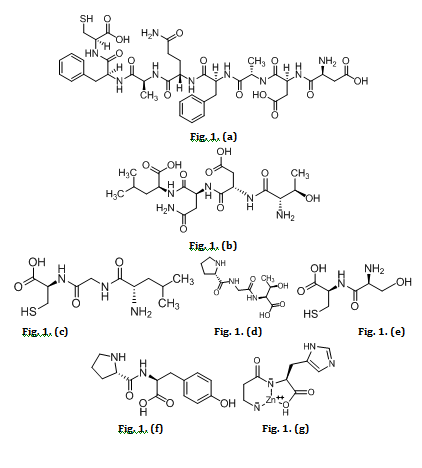

Six peptides isolated from H. scabra (DDAFQAFC, TDNL, LGC, PGT, SC, and PY) have been registered in patent number P00202211622 [24, 28]. The peptide structure visualization in fig. 1. In briefly, before HPLC analysis, H. scabra peptides (HsP) hydrolysates were prepared and then filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter to ensure sample clarity and protect the HPLC system. Based on the resulting chromatogram, two distinct fractions, HsP1-1 and HsP1-2, were carefully collected. These collected peptide fractions, HsP1-1 and HsP1-2, were subsequently reacted with zinc to evaluate their binding capabilities. The purified HsP1-1 fraction, identified for its superior Zn(II)-chelating capacity compared to HsP1-2, underwent further analysis using LCMS-8060 Triple Quadrupole LC-MS/MS.

ADMET prediction of peptides from Holoturia scabra

SwissADME (www.swissadme.ch) was used to predict the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion (ADME) of the six peptides from H. scabra. ADME analysis of peptides also includes drug-likeness analysis based on Lipinsky’s rule of five and its oral bioavailability [26]. AdmetSAR 2.0 (https://lmmd.ecust.edu.cn/admetsar3/index.php) was used to predict the toxicity of peptides [29].

Fig. 1: Peptides from Holothuria scabra (a) DDAFQAFC, (b) TDNL, (c) LGC, (d) PGT, (e) SC, (f) PY, (g) Zinc-carnosine

Molecular docking of peptides with target proteins

Molecular dockings were conducted on six peptides from collagen hydrolysates: DDAFQAFC, TDNL, LGC, PGT, SC, and PY. The target protein was based on the results of prior steps. Molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina software with AutoDock Tools 1.5.6 (www.vina.scripps.edu). The peptide structure was visualized and prepared using MarvinSketch 20.12 (www.chemaxon.com), while the target protein structure was visualized and prepared using Biovia Discovery Studio 19.1.0 (www.discover.3ds.com). This study was through a blind docking technique with the grid box size: x, y, and z sizes of 52, 54, 80, respectively. Molecular docking used is flexible docking to determine the most stable conformation and orientation with minimal energy between the peptide and ZIP2 receptor [30]. All peptide and target protein structures were saved in. pdb and. pdbqt formats [26, 27].

Molecular dynamics simulation

The validity of molecular docking is validated by using molecular dynamics simulation. In this study, peptide PY with the best Gibbs energy will be complexed with ZIP2 protein, one of the receptors obtained through network pharmacology. MD simulation starts from energy minimization in the system. The temperature is increased from 0 to 298 K with an NVT-constant parameter of 500 ps, the temperature is kept at 298 K at a pressure of 1 atm using a Langevin thermostat [31–33].

The protein binding complex with the test compound in pdb form is then input into the (www.yasara.org) and run with the md_run. mcr file. In the md_run. mcr file, several parameters need to be considered; the pH used, which is 7.4; ions Na and Cl, a temperature of 298K, the shape of the cube simulation box, a duration of 50 ns or 50000 ps, a save interval of 10000 ps or every 10ns, and an Amber14 forcefield. The results of Rg, RMSD, and RMSF from molecular dynamics simulations are analyzed and visualization in YASARA analysis functions [34, 35].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ninety targeted genes expressed proteins related to zinc deficiency

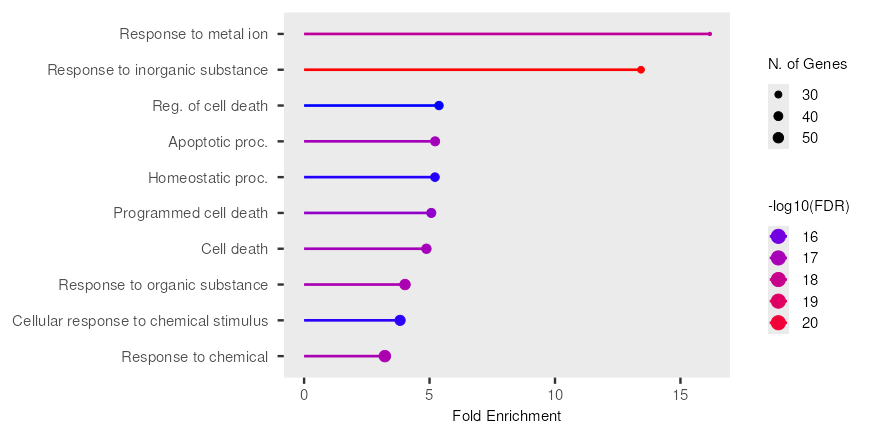

Target genes expressing proteins (obtained using the keyword “zinc deficiency” through DisGeNET showed 90 target genes (Suppl data 1). The biological process of these genes is shown in fig. 2. According to the figure, of the 90 genes that were obtained the biological process enrichment from gene ontology analysis.

Fig. 2: Biological process enrichment from gene ontology analysis. Y-axis: Lists various biological processes (GO terms) that have been identified as enriched. X-axis: Represents "N. of Genes," indicating the number of genes associated with each particular GO term that were found to be enriched in the dataset

The fig. 2 illustrates the results of a gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, specifically highlighting biological processes that are significantly over-represented within a given gene set. The x-axis represents "Fold Enrichment," indicating how many times more frequently a GO term appears in the gene set compared to random expectation. The y-axis lists various biological processes. The size of each circle corresponds to the "N. of Genes" associated with that particular GO term, with larger circles indicating a greater number of genes. The color of each bar and circle denotes the statistical significance of the enrichment, expressed as "-log10(FDR)" (False Discovery Rate). A higher-log10(FDR) value, depicted by a shift from purple to red, signifies a more statistically significant enrichment.

From the plot, "Response to metal ion" exhibits the highest fold enrichment and is highly significant, as indicated by its deep purple colour. Similarly, "Response to inorganic substance" also shows a substantial fold enrichment and is among the most significant terms, appearing in red. Several GO terms related to cell death, including "Reg. of cell death," "Apoptotic proc.," "Programmed cell death," and "Cell death," are enriched to a lesser extent but still show notable significance (blue/purple). Other enriched terms include "Homeostatic proc.," "Response to organic substance," "Cellular response to chemical stimulus," and "Response to chemical," all displaying varying degrees of enrichment and statistical significance. The varying sizes of the circles across different terms suggest that the enriched biological processes involve different numbers of genes, providing insight into the scale of genetic involvement for each GO term.

In reference to biological processes related to inflammation and the immune system. Zinc influences the production of numerous cytokines, which are signaling molecules that orchestrate the immune response. It can both positively and negatively regulate cytokine expression, depending on the specific cytokine and cellular context [36, 37]. Zinc deficiency is often associated with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This occurs through several mechanisms, including the dysregulation of NFĸB and impaired antioxidant defenses. Zinc is a crucial component of superoxide dismutase (SOD), an enzyme that helps neutralize harmful reactive oxygen species produced during inflammation. Zinc deficiency can impair SOD activity, leading to increased oxidative stress, which further fuels inflammation. Zinc contributes to the production of NK cells by stem cells [11, 38]. Research on young stem cells shows that zinc can increase the development of CD34+cells (expressing CD56+CD16-phenotype). Meanwhile, old stem cells express CD56-, CD16+or CD56+, CD16+through the increased expression of GATA-3 as a transcription factor [39]. According to in vivo studies and studies in humans, zinc deficiency is associated with decreased cytotoxicity in the cells [40]. Research related to zinc supplementation in children with diarrhea has reported that oral rehydration solution therapy decreased the duration of acute diarrhea for 17 h [41]. Zinc deficiency is associated with immunity and prognosis of many diseases, including the common cold, sepsis, and malaria [42, 43]. Hence, the data obtained through database construction indicates the relevance of clinical, animal, and in vitro studies on inflammatory, immune, and infectious mechanisms due to zinc deficiency.

Related to the biological function of transporters, zinc needs to be transported and distributed within the scope of cell organelles to accomplish many functions. The process of transport and distribution occurs through a complex mechanism that involves genes that express transporter proteins. The estimated total amount of zinc in the human body is no more than 2.6 g, with most of it distributed in bones and skeletal muscles. Zinc distribution in the body binds to albumin and transferrin proteins with high binding affinity [44, 45]. Studies involving genetic knockout or knockdown of specific transporter genes have revealed their necessity for development and organ-specific functions. For example, mutations in SLC30A2 (encoding ZnT2), which transports zinc into milk vesicles, can impair zinc secretion into breast milk, affecting infant zinc nutrition. Mutations in SLC39A4 (encoding ZIP4), a key intestinal zinc importer, cause Acrodermatitis Enteropathica, a severe genetic disorder characterized by profound zinc deficiency [46, 47].

Several genes targeted in the zinc homeostasis pathway

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) by network pharmacology is beneficial to finding the target protein/gene of a drug candidate, thereby increasing efficiency in discovering new drugs [48]. It was carried out using the STRING database and the visualization of analysis funds using Cytoscape software on 90 target proteins. The results of the Cytoscape analysis through cluster construction on CytoCluster revealed three clusters in 90 target proteins that affect “zinc deficiency.” One of the clusters is a collection of genes that express 10 target proteins on zinc homeostasis (table 1, fig. 3). This research using highest confidence (0.900) for reducing false positives to focus on strong related genes in zinc deficiency to experimentally supported interactions.

The results are arranged based on betweenness using CytoNCA. Betweenness ranks the number of shortest paths that pass through each node of the network. The shortness of paths in any given node is used as an indicator of importance. Betweenness centrality is often chosen as a primary topological parameter for ranking importance in networks because it effectively identifies nodes that act as bridges or intermediaries in the flow of information, resources, or influence within a network. The betweenness rank described in fig. 3 shows that there are 10 important target protein genes in zinc homeostasis [49]. Nine genes—SLC39A2, SLC30A3, SLC39A4, SLC30A2, SLC30A4, SLC39A13, SLC29A8, TEX11, and C904f84—play a role in zinc transporters [50, 51]. The TEX11 gene expresses Testis-expressed protein 11 with the synonym ZIP4 on zinc transport in the testis (UniProtKB: Q8IYF3) [52], while the C904f84 (SHOC1) gene expresses the shortage chiasmata protein one ortholog with the synonym ZIP2 (UniProtKB: Q5VXU9) [53]. While, GPR39 gene expresses G-protein coupled receptor 39 (UniProtKB; O43194) play role is zinc sensing receptor for detecting changes in extracellular zinc levels and initiate signalling pathways in response [54]. Nine genes from the zinc transporter family, both from the ZnT and ZIP families, are associated with zinc deficiency based on PPI analysis (table 1). The SLC39A2 gene has the highest betweenness, indicating that it has many network links between nodes in the zinc homeostasis gene cluster.

Fig. 3: Cytoscape analysis using CytoCluster found three clusters distinguished by colour: blue, purple, and green. One of the clusters comprises genes that express target proteins dominated by the zinc homeostasis family (purple). Ten of the target genes contained in the cluster are dominated by the zinc transporter family (SLC39A and SLC30A)

Table 1: PPI network topology data of gene clusters in zinc homeostasis

| Symbol | Ensembl Gene ID | Betweenness | Entrez | Species | Chr | Position (Mbp) | Description |

| SLC39A2 | ENSG00000165794 | 17.4 | 29986 | Human | 14 | 20.9993 | solute carrier family 39 member 2 |

| TEX11 | ENSG00000120498 | 16.0 | 56159 | Human | X | 70.5289 | testis expressed 11 |

| SLC30A3 | ENSG00000115194 | 9.4 | 7781 | Human | 2 | 27.2537 | solute carrier family 30 member 3 [ |

| SLC39A4 | ENSG00000147804 | 8.4 | 55630 | Human | 8 | 144.4097 | solute carrier family 39 member 4 |

| SLC30A2 | ENSG00000158014 | 7.0 | 7780 | Human | 1 | 26.0373 | solute carrier family 30 member 2 |

| SLC30A4 | ENSG00000104154 | 1.0 | 7782 | Human | 15 | 45.4796 | solute carrier family 30 member 4 |

| SLC39A8 | ENSG00000138821 | 0.4 | 64116 | Human | 4 | 102.2511 | solute carrier family 39 member 8 |

| SLC39A13 | ENSG00000165915 | 0.4 | 91252 | Human | 11 | 47.4071 | solute carrier family 39 member 13 |

| GPR39 | ENSG00000183840 | 0.0 | 2863 | Human | 2 | 132.4168 | G protein-coupled receptor 39 |

C9ORF84 (SHOC1) |

ENSG00000165181 | 0.0 | 158401 | Human | 9 | 111.79 | shortage in chiasmata 1 |

Table 1 provides of genes implicated in zinc homeostasis, a critical physiological process. Among these, the Solute Carrier (SLC) families, specifically SLC39A (ZIP transporters) and SLC30A (ZnT transporters), represent the primary machinery for cellular zinc transport. ZIP transporters, such as SLC39A2, SLC39A4, SLC39A8, and SLC39A13, facilitate the influx of extracellular zinc into the cytoplasm or its release from intracellular organelles, thereby increasing intracellular zinc concentrations. Conversely, ZnT transporters, including SLC30A2, SLC30A3, and SLC30A4, are responsible for reducing cytoplasmic zinc levels by either promoting its efflux from the cell or sequestering it into intracellular vesicles. The intricate balance between these two families is paramount for maintaining appropriate intracellular zinc concentrations, which in turn influences a myriad of cellular processes, including enzyme activity, gene expression, and signalling pathways [55]. As for GPR39 gene functions as a zinc-sensing G protein-coupled receptor. It is activated by extracellular zinc ions, leading to downstream signalling pathways that can influence various cellular processes, including ion transport, cell growth, and inflammatory responses. Its role as a direct sensor of zinc levels positions it as a key regulator in maintaining zinc homeostasis by initiating cellular adaptations to changes in zinc availability [56]. For C9ORF84 gene, also known as SHOC1, is involved in meiotic recombination and chromosome synapsis, similar to TEX11. Its primary function is in maintaining genomic integrity during cell division. While not directly a zinc transporter, its inclusion in a zinc homeostasis network might suggest that zinc plays a regulatory role in these fundamental cellular processes, or that SHOC1's activity is sensitive to cellular zinc levels [53].

Fig. 4. (a)

Fig. 4. (b)

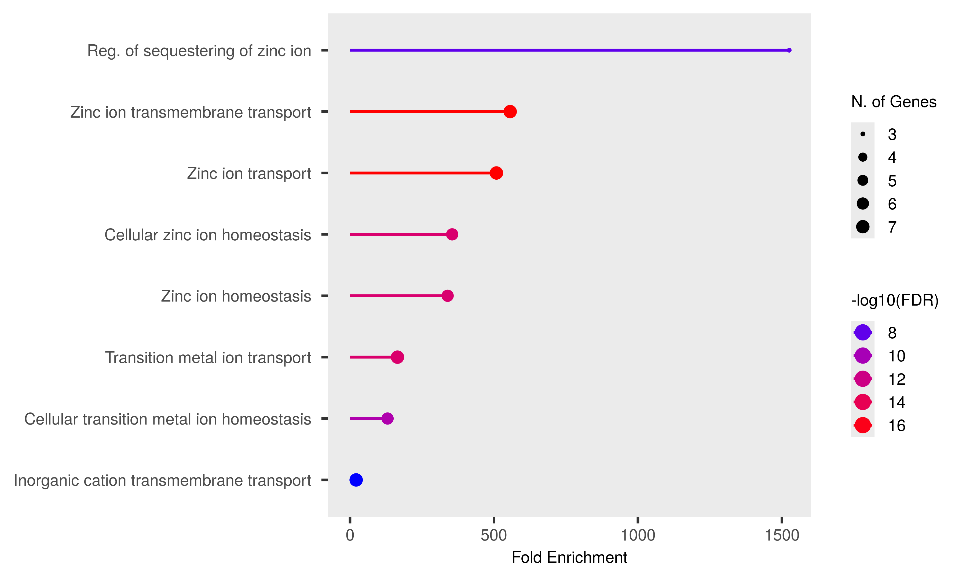

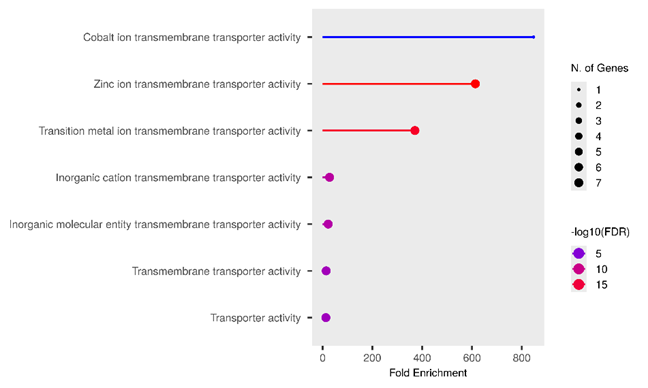

Fig. 4. (c)

Fig. 4: Gene ontology analysis of 10 target proteins in a zinc homeostasis cluster under zinc deficiency conditions: (a) biological process, (b) cellular component, and (c) molecular function

According to PPI analysis, SLC39A2 is an important gene in regulating zinc transport in organisms. However, further analysis needs to be done to simulate animal models to determine the expression of the SLC39A2 gene and other interacting genes. The SLC39A2 is a gene encoding human ZIP2 located on human chromosome number 14, with its protein sequence and reference number NM_014579, is composed of 309 amino acids, including 26 amino acid signal peptides. ZIP2 gene expression is also found in the small intestine, liver, spleen, and bone marrow [51]. Consequently, while SLC39A2 is indisputably implicated in zinc transport and the maintenance of cellular zinc levels, its direct contribution to systemic zinc deficiency, in a similar conspicuous manner as a complete loss of SLC39A4 function, is less pronounced. Instead, its impact is more likely observed in tissue-specific dysregulation of zinc homeostasis, contributing to local zinc deficiencies that can underpin various pathological conditions, including inflammatory responses and certain diseases like carotid artery disease and potentially even cancer. Further research is underway to fully elucidate the intricate role of SLC39A2 in the broader landscape of human health and its precise correlation with various forms of zinc deficiency.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis is a fundamental computational method in systems biology employed to identify statistically significant functional categories within a given gene list. The three bubble plots collectively indicate that the analyzed gene set is highly enriched for biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions pertaining to metal ion homeostasis and transport, particularly zinc. The consistently highest and most statistically significant enrichments in "Regulation of sequestering of zinc ion" (fig. 4. (a)), "Late endosome" (fig. 4. (b)), and "Cobalt/Zinc ion transmembrane transporter activity" (fig. 4. (c)) strongly suggest a crucial role for these genes in the intracellular and extracellular management of these essential elements.

More specifically, fig. 4. (a), which focuses on Biological Processes, demonstrates that these genes are actively involved in the regulation and transport of zinc ions. "Reg. of sequestering of zinc ion" exhibits the highest Fold Enrichment (>1500) and an exceptionally high statistical significancs (−log10(FDR)approx16). Zinc serves as a vital cofactor for hundreds of enzymes and structural proteins, in addition to its roles in cellular signaling and immune responses [57]. Therefore, a tight regulation of zinc availability and localization is paramount for cellular function. This finding is consistent with literature indicating that zinc dyshomeostasis can contribute to various pathological condition [58]. Furthermore, the Cellular Component analysis in fig. 4. (b) predominantly highlights the localization of these genes to organelles involved in the endosomal-lysosomal/vacuolar pathway, notably the "Late endosome" and "Lysosomal membrane," with the highest Fold Enrichments (approximately 22 and 19, respectively) and high significance (−log10(FDR) approx2.75). Endosomes and lysosomes are critical sorting and degradation centers that also play a role in the storage and release of metal ions [59]. This correlation suggests that zinc management may be highly integrated with the cellular endomembrane system, facilitating regulated zinc uptake, storage, or release. Fig. 4. (c), illustrating Molecular Functions, confirms metal ion transporter activity as a dominant function, with "Cobalt ion transmembrane transporter activity" and "Zinc ion transmembrane transporter activity" being the most enriched and significant categories. Although "Cobalt ion transmembrane transporter activity" shows the highest Fold Enrichment (approximately 850) with only one gene, "Zinc ion transmembrane transporter activity" also possesses very high enrichment (approximately 600) but involves a larger number of genes (6-7 genes). This underscores that specific mechanisms for zinc and other transition metal transport across membranes are core functions of this gene set, highlighting the importance of transmembrane proteins in maintaining metal homeostasis [60].

Fig. 5: Zinc homeostasis pathway related with zinc transporters

Furthermore, Wikipathway was used to determine the target proteins in a clear zinc homeostasis pathway (fig. 5). SLC39A2, SLC30A3, SLC39A4, SLC30A2, SLC30A4, SLC39A13, and SLC29A8 are found in the cell membrane and the endosome. The zinc transport mechanism at the cellular level begins when zinc ions pass through the proteins in the SLC39A family (i. e., SLC39A1-SLC30A14, which are in the cell membrane). Afterward, zinc binds to the metallothionein family (MTs), which comprises MT1A-MT1H, MT1L, MT1M, MT1X, MT2A, MT3, and MT4. Zinc ions in the cytoplasm are distributed in organelles such as endosomes, neurons, lysosomes, and many other organelles with specific zinc transporter proteins. The zinc transporter family that functions to transport zinc from the cytoplasm to cell organelles is the SLC30A family: SLC30A1-SLC30A10. The zinc ions that are transported from the cell organelles to the cytoplasm are facilitated specifically by the SLC39A protein. Zinc ions from the cytoplasm to the blood vessels (to be distributed to other organs) exit through the cell membrane facilitated by the SLC30A1 gene.

Toxicity and ADME prediction properties of six peptides

In the table 2 described the toxicity properties of six peptides from Holothuria scabra by AdmetSAR. In essence, AdmetSAR leverages a combination of diverse machine learning algorithms, trained on extensive datasets of chemical structures and their associated ADMET properties, to generate its toxicity predictions [61]. The choice of algorithm often depends on the specific ADMET endpoint being predicted (e. g., Ames mutagenesis, hERG inhibition, acute toxicity, carcinogenicity), as some algorithms perform better for certain types of data or prediction tasks.

The AMES test is a widely utilized biological assay that evaluates chemical compound's mutagenic potential. The bacterium utilizes specific strains of Salmonella typhimurium, which have been genetically modified to be incapable of synthesizing histidine. The peptides as "non-AMES toxic" in the data signifies that they did not demonstrate mutagenic potential in the Ames test. This outcome is considered favorable, as it suggests a low propensity to induce DNA damage or mutations. A carcinogen is any substance, radionuclide, or radiation that promotes carcinogenesis, the formation of cancer. This classification is often based on long-term animal studies, epidemiological data, and mechanistic understanding. "Non-carcinogens" in the data means that the peptides are not currently classified as carcinogens. This is another favorable safety indicator. LD50, or Median Lethal Dose, is a metric used to quantify the acute toxicity of a substance. It represents the dose that is lethal to 50% of the exposed animal population (e. g., rats) within a given time period. A higher LD50 is indicative of lower acute toxicity, signifying that a greater dose is required to cause death in half of the population. The LD50 values, ranging from 1.8808 to 2.1232 mol/kg, signify the concentration that results in 50% of the rats tested perishing. The hERG potassium channel is critical for cardiac repolarization; its inhibition can prolong the QT interval, risking a fatal arrhythmia called Torsades de Pointes. This renders hERG inhibition a major drug development safety concern. The "weak inhibitor" designation in the data indicates that these peptides demonstrate some, albeit not potent, hERG channel inhibition. While weak inhibition is generally preferable to strong inhibition, any hERG inhibition must be meticulously evaluated during drug development, as its significance can vary based on the therapeutic dose and other factors.

Table 2: Toxicity properties of zinc-binding peptides

| Peptide | AMES toxicity | Carcinogens | Rat acute toxicity LD50 (mol/kg) | hERG inhibitor |

| DDAFQAFC | Non-AMES toxic | Non-carcinogens | 1.9497 | Weak inhibitor |

| TDNL | Non-AMES toxic | Non-carcinogens | 2.0234 | Weak inhibitor |

| LGC | Non-AMES toxic | Non-carcinogens | 2.0117 | Weak inhibitor |

| PGT | Non-AMES toxic | Non-carcinogens | 2.0402 | Weak inhibitor |

| SC | Non-AMES toxic | Non-carcinogens | 1.8808 | Weak inhibitor |

| PY | Non-AMES toxic | Non-carcinogens | 2.1232 | Weak inhibitor |

| Zn-carnosine | Non-AMES toxic | Non-carcinogens | 2.0025 | Weak inhibitor |

Table 3: ADME properties of zinc-binding peptides based on Lipinski’s rule and physiochemistry

| Peptide | MW (g/mol) | H acc | H don | log P | Theoretical pI | Molar refractivity |

Formula | Solubility in water |

| DDAFQAFC | 915.97 | 15 | 13 | -3.42 | 3.35 | 223.23 | C40H53N9O14S | High |

| TDNL | 461.472 | 10 | 8 | -3.66 | 3.82 | 105.92 | C18H31N5O9 | High |

| LGC | 291.37 | 5 | 5 | -0.92 | 5.92 | 72.00 | C11H21N3O4S | High |

| PGT | 273.289 | 6 | 5 | -2.37 | 6.39 | 64.13 | C11H19N3O5 | High |

| SC | 208.23 | 5 | 5 | -2.11 | 5.81 | 47.06 | C6H12N2O4S | High |

| PY | 278.308 | 5 | 4 | 0.72 | 6.45 | 71.96 | C14H18N2O4 | Hgh |

| Zn-carnosine | 289.60 | 5 | 4 | -2.22 | 7.94 | 55.56 | C9H14N4O3Zn | High |

From table 3, described the Lipinski's Rule of Five is a heuristic employed to predict whether a small molecule has the properties necessary for passive oral absorption. The parameters designed to prioritize candidates in the context of drug discovery. Oral bioavailability is defined as the actual proportion of a pharmaceutical agent that reaches systemic circulation. It is influenced by a number of factors, including absorption and metabolism. Peptides frequently violate Lipinski's rules because their absorption mechanisms are often active and transporter-mediated, rather than purely passive diffusion.

The physicochemical data provided elucidates critical attributes of a diverse set of peptides, offering insights into their potential biological behaviours and suitability for various applications. The molecular weight (MW) is a fundamental determinant, with values ranging from 208.23 g/mol (SC) to 915.97 g/mol (DDAFQAFC). This broad range suggests varied membrane permeability and potential bioavailability profiles, with smaller peptides like SC generally exhibiting greater potential for cellular uptake. Furthermore, the number of hydrogen bond acceptors (H acc) and donors (H don), ranging from 5-15 and 4-13, respectively, directly correlates with the peptides' hydrophilicity and aqueous solubility. All compounds consistently demonstrate high solubility, a desirable trait for pharmaceutical formulation [62].

The analysis of log P values, ranging from-3.66 (TDNL) to 0.72 (PY), provides further insight into the lipophilicity of these peptides. The predominantly negative log P values indicate a strong preference for aqueous environments, suggesting robust water solubility but potentially limited passive diffusion across lipid bilayers. Conversely, PY, with its positive log P, represents the most lipophilic entity within the dataset, potentially offering a slight advantage in membrane permeability. Furthermore, the theoretical isoelectric point (pI) varies from 3.35 (DDAFQAFC) to 7.94 (Zn-carnosine), thus revealing a spectrum from acidic to slightly basic peptides. This variation in pI is crucial for understanding the net charge of each peptide at different physiological pH values, thereby influencing their interactions with charged biomolecules and their behaviour in separation techniques [61].

A critical consideration for the oral bioavailability of these peptides is their compliance with established pharmacokinetic predictors, such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, which was primarily designed for small-molecule drugs. It is noteworthy that DDAFQAFC (MW 915.97 g/mol, Molar Refractivity 223.23) and TDNL (MW 461.472 g/mol, Molar Refractivity 105.92) evidently contravene the molecular weight (≤500 g/mol) and frequently, implicitly, the molar refractivity rules of thumb, indicating substantial constraints on passive diffusion across biological membranes. This deviation suggests that their oral bioavailability via conventional passive transport mechanisms would likely be poor. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that peptides frequently contravene Lipinski's rules due to their larger size, inherent polarity, and susceptibility to enzymatic degradation. Consequently, achieving oral bioavailability for such peptides, if targeted for oral supplementation, would necessitate specialised formulation strategies, including the use of protease inhibitors, absorption enhancers, or the exploitation of specific active transport systems within the gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, although conventional small-molecule predictions indicate difficulties, the capacity of these peptides to function as efficacious oral supplements is a subject that merits further exploration, incorporating the utilisation of sophisticated delivery technologies. [63–66].

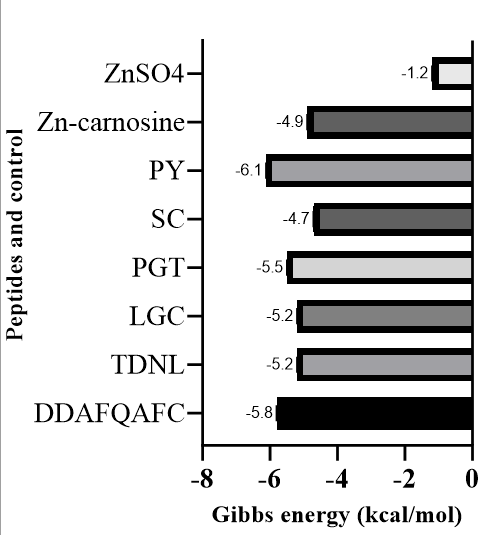

Peptide PY has stability energy to bind with ZIP2 protein

Based on the provided data from the fig. 6, the strongest binding interactions, indicated by the most negative Gibbs energy values, are observed for PY (-6.1 kcal/mol) and DDAFQAFC (-5.8 kcal/mol). These highly negative values suggest that PY and DDAFQAFC form exceptionally stable and highly favourable complexes or interactions with the target, surpassing all other compounds.

Fig. 6: Gibbs energy graph of zinc-binding peptides against the ZIP2 target protein. The most potent zinc peptide is PY (-6.1 kcal/mol), which is better than Zinc-carnosine (-4.9 kcal/mol)

Fig. 6 demonstrated, PY and DDAFQAFC exhibit significantly more negative Gibbs energy values than Zn-carnosine. The former exhibits a Gibbs energy value of-6.1 kcal/mol, and the latter a Gibbs energy value of-4.9 kcal/mol. This finding suggests that the distinctive chemical structures and larger molecular surfaces of PY and DDAFQAFC facilitate more extensive and energetically favourable interactions with the target in comparison to the chelated zinc-carnosine complex. While Zn-carnosine demonstrates a favourable interaction, it is noteworthy that its potency in this regard is significantly lower than that of PY and DDAFQAFC [67]. A comparison between the two zinc-containing compounds is particularly insightful. Zn-carnosine (-4.9 kcal/mol) demonstrates a substantially more negative Gibbs energy than ZnSO4 (-1.2 kcal/mol). This marked difference underscores the notion that the chelation of zinc by carnosine significantly enhances the overall binding affinity or interaction strength with the target. It has been demonstrated that a simple inorganic zinc salt, such as ZnSO₄, exhibits only a very weak and much less favourable interaction. This finding suggests that the carnosine moiety in Zn-carnosine plays a crucial role in mediating the interaction, likely by providing additional binding points or stabilising the complex. This process would render the zinc more "bioavailable" or effective in its interaction with the specific target [68–70].

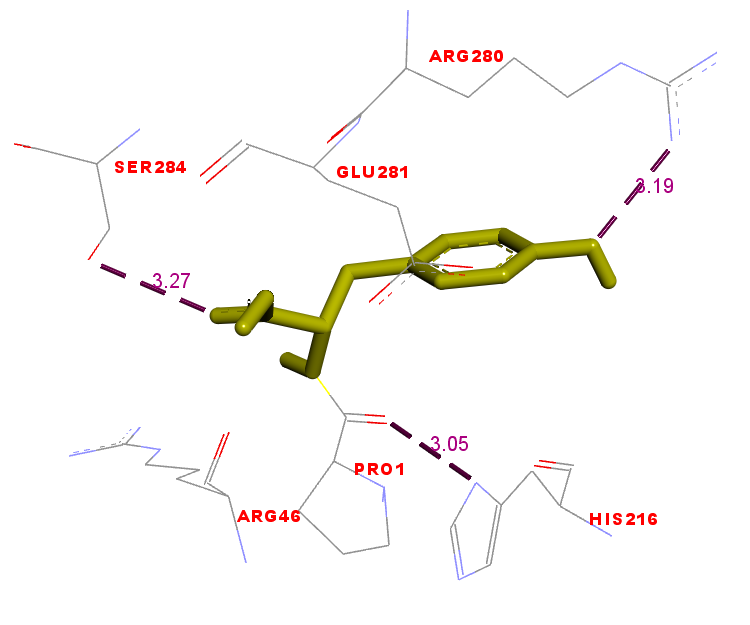

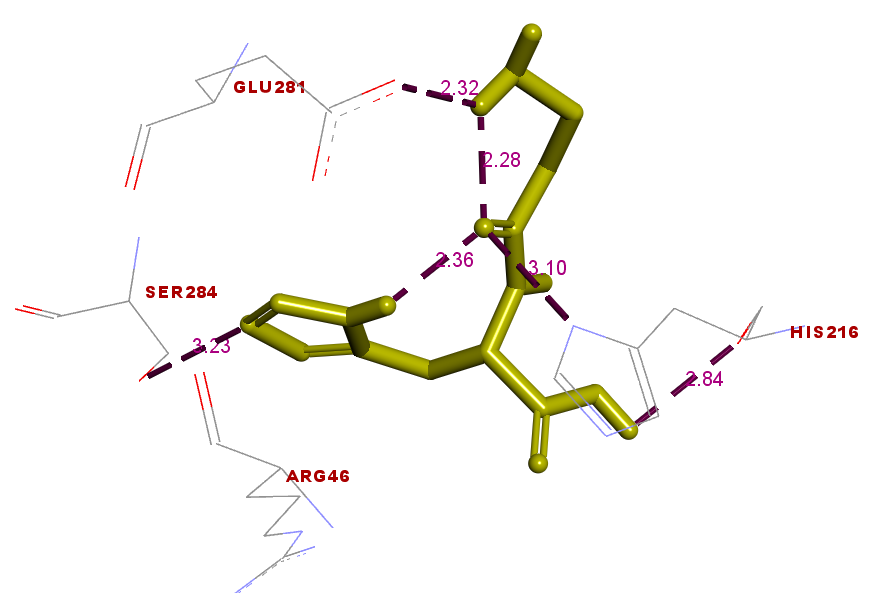

Interactions of molecules include hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic interactions between the amino acids on the binding side of the ZIP2 protein to the peptide. The geometry interaction of the PY peptide and Zn-carnosine with the ZIP2 protein is shown in fig. 7. The presence of hydrogen bonds formed between the PY peptide and the ZIP2 protein—namely, at His (216), Arg (280), and Ser (284)—can also be seen (fig. 7. (a)). While in the Zn-carnosine control, hydrogen bonds are formed at Glu (281), Arg (280), Ser (284), and Lys (291) (fig. 7. (b)). In addition, there is an interaction in the hydrophobic area between Peptide PY and the ZIP2 protein. The hydrogen bond interaction and hydrophobic area formed on the amino acid binding side of ZIP2 suggest that the peptide PY and Zn-carnosine interact on the same ZIP2 binding site. The geometry and energy of the complex formed between the PY peptide and the ZIP2 receptor indicate a potential zinc-binding peptide that could exhibit stability in its binding to the ZIP2 protein. Some zinc-binding peptides that have been done in previous studies are peptides with the sequence His-Leu-Arg-Gln-Glu-Glu-Lys-Glu-Glu-Val-Thr-Val-Gly-Ser-Leu-Lys derived from the oyster [20]. In addition, peptides with smaller sizes were obtained from sesame, with peptide sequences Leu-Ala-Asn; Ser-Met; and Asn-Cys-Ser, which can bind 56-71% zinc [19]. The bioactivity of peptides depends on the structure of their amino acid composition, sequence, and size [14]. The mechanism of zinc-chelating peptides has not been revealed, so there is a need for in-depth investigation. The molecular docking in this study can be a simulation that illustrates the interaction between the zinc transporter in zinc transport through its binding to the peptide.

Fig. 7. (a) Fig. 7. (b)

Fig. 7: Interactions between the PY peptide (yellow) and (a) Zn-carnosine (yellow) (b) docked to the ZIP2 protein

Fig. 8. (a)

Fig. 8. (b)

Fig. 8. (c)

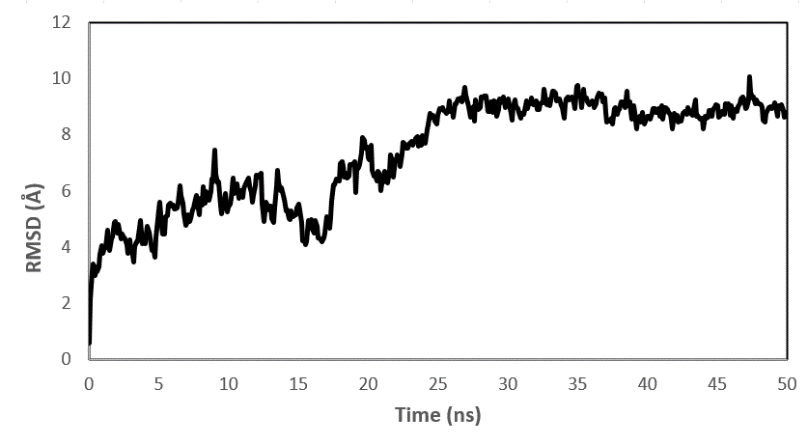

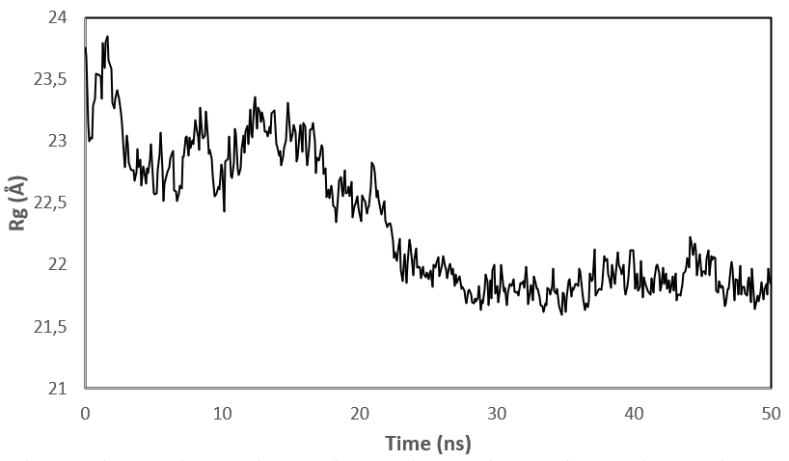

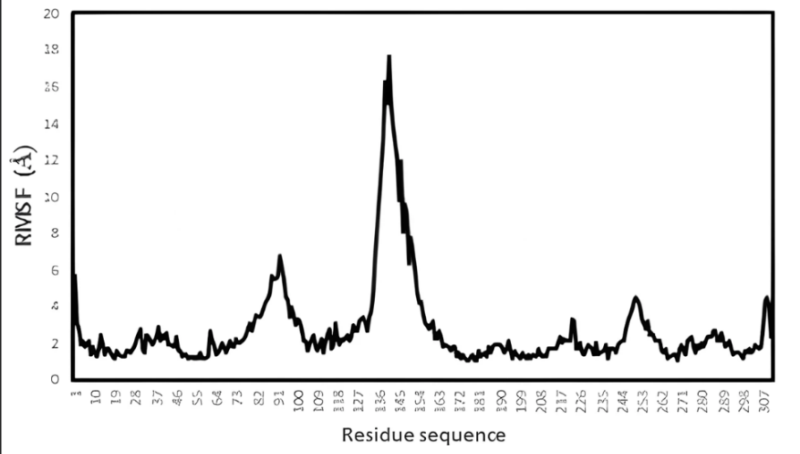

Fig. 8: (a) RMSD value of the complex PY peptide with ZIP2 protein protein (b) Rg value of the complex PY peptide with ZIP2 protein (c) RMSF value of the complex PY peptide with ZIP2 protein of ZIP2

Peptide PY is stable with ZIP2 protein in simulations

Molecular dynamics analysis was conducted to determine and validate the stability of ligand-protein complexes from molecular docking results according to fluctuations in the stability of interacting atoms in ligands and proteins. The simulation was performed computationally with physical and environmental parameters by the human body's reaction conditions of ligand and protein complexes [35]. Fig. 7 shows that the PY peptide is a potential peptide for interacting through hydrogen bonds with the binding site of the ZIP2 protein. To validate the structural stability of the complex between ZIP2 and peptide PY, we use several parameters, namely, root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and radius of gyration (Rg). RMSD is a parameter that analyzes the complex stability within a certain simulation period. RMSF is a measurement to see the flexibility of each residue in the protein. Meanwhile, Rg parameter is used to determine stability with changes in protein size and monitor protein formation complex process [31, 33, 35].

The RMSD result on the ZIP2 protein shows that there is an equilibrium phase, this protein has stability after 25 ns until the completion of the simulation (fig. 8.(a)). This indicates that the complex between ZIP2 and peptide PY is stable until the end of the simulation. Fluctuations occur at the beginning of the simulation up to 25 ns, this is due to interactions between each residue in the ZIP2 protein, including electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and interactions between ZIP2 and molecules in the peptide PY ligand. Fluctuations decrease after 25 ns until the end of the simulation, which indicates the stability of the complex between the ZIP2 protein and peptide PY.

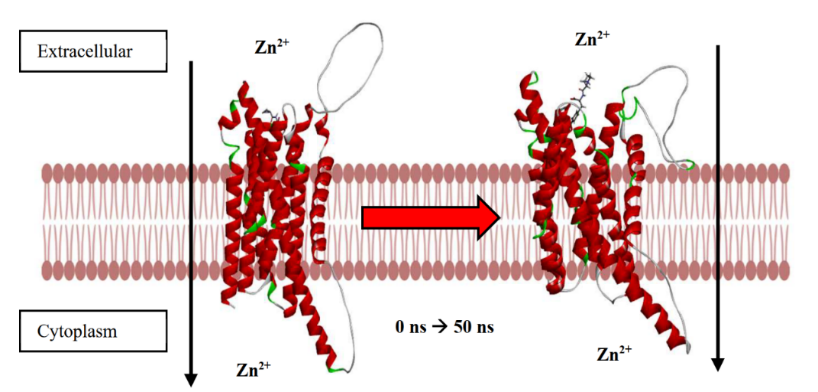

Fig. 9. (a)

Fig. 9. (b)

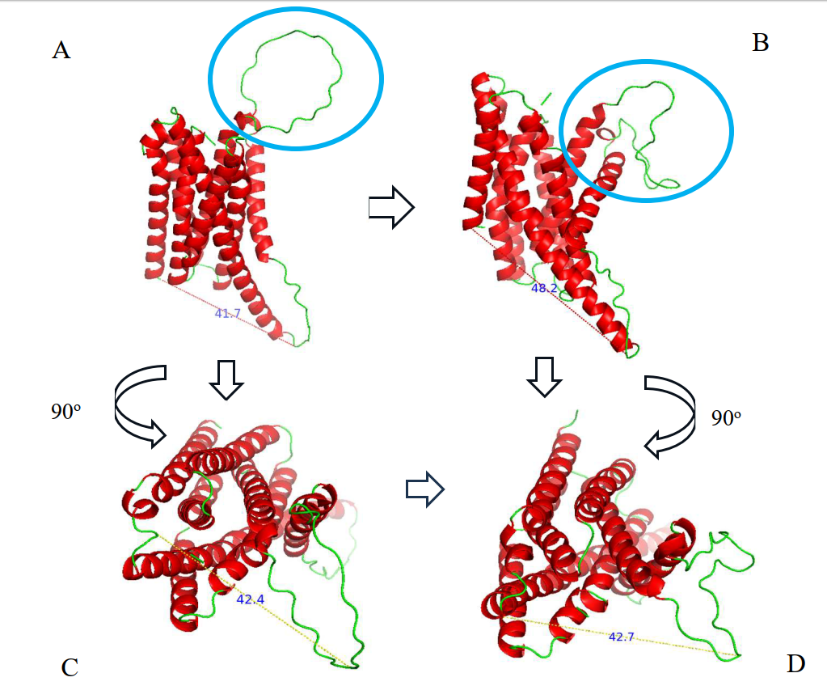

Fig. 9: (a) Conformational change of ZIP2 when interacting with PY peptide at 0 ns to 50 ns (b) A) ZIP2 structure before simulation, B) ZIP2 structure after 50 ns simulation, C) Transverse ZIP2 structure (rotated 90 ) before simulation, D) Transverse ZIP2 structure (rotated 90 ) after 50 ns simulation. There is a change in distance in the zinc-binding domain in the exterior of the ZIP2 protein in the extracellular part and in the zinc-binding domain in the exterior of the ZIP2 protein in the cytoplasmic part

Meanwhile, at the beginning of the simulation, the ZIP2 complex and peptide PY experienced a considerable distance, around 23.8 Å, and began to get closer as the simulation progressed until the final simulation process was recorded at a distance of 21.6 Å. Based on the Rg data (fig. 8. (b)), it can be analyzed that, during the simulation, the ZIP2 complex and peptide PY experienced stability until the end of the simulation by observing the absence of high distance fluctuations. The results of the RMSF of amino acids show a point of fluctuation that tends to be stable, specifically at amino acid residues 191-300 (fig. 8. (c)).

Furthermore, in fig. 7. (a) shows that the PY peptide interacts with hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with ZIP2 proteins at several residues, specifically between residues 200-300. The interaction of ZIP2 and peptide PY is based on molecular docking, the residue interactions on the PY peptide and ZIP2 protein are found at the stable residues on ZIP2. This can be seen from the stable slight fluctuations in residues 200-300 during molecular dynamics simulations (fig. 8. (c)). The fluctuations observed in RMSD, RMSF, and Rg values reflect the inherent flexibility of ZIP2, a characteristic crucial for its role as a zinc transporter [55].

The dynamic conformational shifts observed in the ZIP2 protein upon binding with the PY peptide, as illustrated in fig. 9. (a), provide valuable insights into the potential mechanism by which this peptide facilitates zinc transport. In the fig. 9. (b), the subtle increase in the extracellular zinc-carrying domain's distance (42.4 Å to 42.7 Å) after 50 ns might seem minimal, but it could represent a critical step in facilitating zinc accessibility. In the context of ion transporters, even small conformational changes can significantly alter substrate affinity and transport kinetics [16]. For instance, studies on other metal transporters have shown that minor structural rearrangements can create transient binding sites or lower the energy barrier for ion translocation. The more pronounced expansion of the cytoplasmic domain (41.7 Å to 48.2 Å) suggests a potential mechanism for releasing zinc into the intracellular environment. This observation is consistent with the "alternating access" model, a widely accepted mechanism for membrane transport, where transporters undergo conformational changes to expose substrate-binding sites on opposite sides of the membrane [31]. This model has been extensively studied in various ion transporters, highlighting the importance of domain movements in facilitating substrate release.

Molecular dynamics simulations, as employed in this study, are increasingly recognized for their ability to capture the dynamic nature of protein-ligand interactions, offering a more realistic representation compared to static docking models [35]. The identification of the loop structure (residues 127-159) as a key zinc-binding domain is particularly significant. Loop regions are known for their flexibility and adaptability, allowing them to participate in substrate recognition and binding [33]. Similar loop-mediated binding mechanisms have been observed in other metal transporters, where loop regions contribute to substrate selectivity and binding affinity. The observed opening of this loop during the simulation suggests a potential mechanism by which the PY peptide facilitates zinc transfer by creating a more accessible binding site. The observed conformational changes in ZIP2 are consistent with the understanding that zinc transporters undergo significant structural rearrangements to shuttle zinc ions across membrane [56]. Studies on other members of the ZIP family have also reported ligand-induced conformational changes, highlighting the importance of structural flexibility in zinc transport. The observed conformational changes in ZIP2, particularly the opening of the loop structure and the expansion of zinc-carrying domains, provide compelling evidence for the potential of the PY peptide to enhance zinc transport.

CONCLUSION

In this study, the target protein in zinc deficiency was determined through network pharmacology, followed by molecular simulation analysis (i.e., molecular docking and molecular dynamics) to determine the activity of six sea cucumber H. scabra collagen bioactive peptides. In network pharmacology, protein-protein interaction (PPI) was used to determine the target protein in zinc deficiency through the interactions of 90 genes. Ten genes were found to play a role in zinc transport, with SLC39A2 having the highest zinc deficiency-related gene interaction. The SLC39A2 gene expresses the ZIP2 protein, a zinc transporter found in the intestine. Six peptides—DDAFQAFC, TDNL, LGC, PGT, SC, and PY—were successfully recognized as zinc binders and underwent molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations to determine their interaction patterns with the ZIP2 protein. It is known that the six test peptides have more potential in their interactions with ZIP2 compared with the control Zn-carnosine and ZnSO4. For molecular dynamics simulation, the interaction of ZIP2 with the PY peptide was analyzed, which is the peptide with the best stable interaction energy of-6.1 kcal/mol. Meanwhile, the RMSD, RMSF, and Rg results of the interaction of ZIP2 with the PY peptide indicate stability after seven ns until the end of the 50-ns simulation. The results showed that the six bioactive peptides of sea cucumber collagen have potential application as one of the supplement materials for zinc binding, and molecular simulations are known to have the potential for stable binding and delivering zinc to the ZIP2 target protein. It is believed that after the peptide successfully delivers zinc through the zinc transporter, the availability of zinc at the cellular level is sufficient to reduce the impact of zinc deficiency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank to Immanuelle Kezia and Laboratory of Bioinformatic Core Facilities, IMERI, University of Indonesia, for allowing us to use their server to conduct the molecular dynamic simulation. This research was funded by a research program (DIPA Rumah Program) at the Research Organization for Health, The National Research and Innovation Agency, Republic of Indonesia (BRIN), fiscal year: 2024.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

G. S, M. L: conceptualization, investigation, reviewing and editing; G. S, M. L.: investigation, methodology, writing an original draft; G. S, M. Y. P.: research design, data analysis; G. S, R. W, A. R, N. G,: data curation, writing—reviewing and editing, G. S: funding acquisition, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

Ohashi W, Fukada T. Contribution of zinc and zinc transporters in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019:8396878. doi: 10.1155/2019/8396878, PMID 30984791.

Guo H, Yu Y, Hong Z, Zhang Y, Xie Q, Chen H. Effect of collagen peptide-chelated zinc nanoparticles from pufferfish skin on zinc bioavailability in rats. J Med Food. 2021;24(9):987-96. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2021.K.0038. PMID 34448624.

Stammers AL, Lowe NM, Medina MW, Patel S, Dykes F, Pérez-Rodrigo C et al. The relationship between zinc intake and growth in children aged 1-8 y: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(2):147-53. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.204, PMID 25335444.

Sharif Y, Sadeghi O, Dorosty A, Siassi F, Jalali M, Djazayery A, et al. Association of vitamin D, retinol and zinc deficiencies with stunting in toddlers: findings from a national study in Iran. Public Health. 2020;181:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.10.029, PMID 31887436.

Gibson RS, Manger MS, Krittaphol W, Pongcharoen T, Gowachirapant S, Bailey KB, et al. Does zinc deficiency play a role in stunting among primary school children in NE Thailand? Br J Nutr. 2007;97(1):167-75. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507250445, PMID 17217573.

Umeta WM. Role of zinc in stunting of infants and children in rural Ethiopia. Wageningen university and research ProQuest dissertations and theses; 2003.

Bening S, Margawati A, Rosidi A. Zinc deficiency as risk factor for stunting among children aged 2-5 y. Universa Med. 2017;36(1):11. doi: 10.18051/UnivMed.2017.v36.11-18.

Santos CA, Fonseca J, Lopes MT, Carolino E, Guerreiro AS. Serum zinc evolution in dysphagic patients that underwent endoscopic gastrostomy for long-term enteral feeding. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26(2):227-33. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.022016.03, PMID 28244699.

Narvaez Caicedo C, Moreano G, Sandoval BA, Jara Palacios MA. Zinc deficiency among lactating mothers from a peri-urban community of the Ecuadorian Andean region: an initial approach to the need of zinc supplementation. Nutrients. 2018;10(7):869. doi: 10.3390/nu10070869, PMID 29976875.

Wapnir RA. Zinc deficiency, malnutrition and the gastrointestinal tract. J Nutr. 2000;130(5S Suppl):1388S-92S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.5.1388S, PMID 10801949.

Gammoh NZ, Rink L. Zinc in infection and inflammation. Nutrients. 2017;9(6):624. doi: 10.3390/nu9060624, PMID 28629136.

Brown KH, Wuehler SE, Peerson JM. The importance of zinc in human nutrition and estimation of the global prevalence of zinc deficiency. Food and nutrient bulletin. Food Nutr Bull. 2001;22(2):113-25. doi: 10.1177/156482650102200201.

Cragg RA, Phillips SR, Piper JM, Varma JS, Campbell FC, Mathers JC. Homeostatic regulation of zinc transporters in the human small intestine by dietary zinc supplementation. Gut. 2005;54(4):469-78. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.041962, PMID 15753530.

Udechukwu MC, Collins SA, Udenigwe CC. Prospects of enhancing dietary zinc bioavailability with food-derived zinc-chelating peptides. Food Funct. 2016;7(10):4137-44. doi: 10.1039/c6fo00706f, PMID 27713952.

Sun X, Sarteshnizi RA, Boachie RT, Okagu OD, Abioye RO, Pfeilsticker Neves RP, et al. Peptide-mineral complexes: understanding their chemical interactions, bioavailability, and potential application in mitigating micronutrient deficiency. Foods. 2020;9(10):1402. doi: 10.3390/foods9101402, PMID 33023157.

Kambe T, Hashimoto A, Fujimoto S. Current understanding of ZIP and ZnT zinc transporters in human health and diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(17):3281-95. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1617-0, PMID 24710731.

Fang Z, Xu L, Lin Y, Cai X, Wang S. The preservative potential of Octopus scraps peptides-zinc chelate against Staphylococcus aureus: its fabrication, antibacterial activity and action mode. Food Control. 2019;98:24-33. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.11.015.

Udechukwu MC, Downey B, Udenigwe CC. Influence of structural and surface properties of whey-derived peptides on zinc-chelating capacity, and in vitro gastric stability and bioaccessibility of the zinc-peptide complexes. Food Chem. 2018;240:1227-32. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.063, PMID 28946246.

Wang C, Wang C, Li B, Li H. Zn(II) chelating with peptides found in sesame protein hydrolysates: identification of the binding sites of complexes. Food Chem. 2014;165:594-602. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.05.146, PMID 25038717.

Chen D, Liu Z, Huang W, Zhao Y, Dong S, Zeng M. Purification and characterization of a zinc-binding peptide from oyster protein hydrolysate. J Funct Foods. 2013;5(2):689-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.01.012.

Meng K, Chen L, Xia G, Shen X. Effects of zinc sulfate and zinc lactate on the properties of tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus) skin collagen peptide chelate zinc. Food Chem. 2021;347:129043. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129043, PMID 33476919.

Liu X, Wang Z, Yin F, Liu Y, Qin N, Nakamura Y. Zinc-chelating mechanism of sea cucumber (Stichopus japonicus)-derived synthetic peptides. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(8):438. doi: 10.3390/md17080438, PMID 31349695.

Syahputra G, Gustini N, Louisa M, Fadilah F, Putra MY. Analysis of sea cucumber metabolites as phytate inhibitor in human ZiP transporter: molecular docking study. In: Nurlaila I, Ulfa Y, Anastasia H, Putro G, Rachmalina R, Ika Agustiya R, Sari Dewi Panjaitan N, Sarassari R, Lystia Poetranto A, Septima Mariya S, editors. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference for the Health Research-BRIN (ICHR 2022). Dordrecht: Atlantis Press International BV; 2023. p. 65-74. doi: 10.2991/978-94-6463-112-8_7.

Syahputra G, Sandhiutami NM, Hariyatun H, Hapsari Y, Gustini N, Sari M. Purification and characterization of a novel zinc chelating peptides from Holothuria scabra and its ex vivo absorption activity in the small intestine. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2024;14:235-46. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2024.180224.

Syahputra G, Gustini N, Louisa M, Putra M, Fadilah A. Structural prediction of human ZIP2 and ZIP4 based on homology modelling and molecular simulation. Int J Appl Pharm. 2023;15(5):287-93. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i5.48240.

Zuhri UM, Purwaningsih EH, Fadilah FF, Yuliana ND. Network pharmacology integrated molecular dynamics reveals the bioactive compounds and potential targets of Tinospora crispa Linn. as insulin sensitizer. PLOS One. 2022;17(6):e0251837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251837, PMID 35737707.

Arwansyah A, Arif AR, Ramli I, Hasrianti H, Kurniawan I, Ambarsari L. Investigation of active compounds of Brucea Javanica in treating hypertension using A network pharmacology-based analysis combined with homology modeling, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. Chemistry Select. 2022;7(1):e202102801. doi: 10.1002/slct.202102801.

Proses Fraksinasi GS. Peptida Kolagen Teripang dan Struktur Peptida yang Dihasilkannya; 2022.

Yang H, Lou C, Sun L, Li J, Cai Y, Wang Z. AdmetSAR 2.0: web-service for prediction and optimization of chemical ADMET properties. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(6):1067-9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty707, PMID 30165565.

Ciemny M, Kurcinski M, Kamel K, Kolinski A, Alam N, Schueler Furman O. Protein-peptide docking: opportunities and challenges. Drug Discov Today. 2018;23(8):1530-7. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.05.006, PMID 29733895.

Roe DR, Cheatham TE. PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J Chem Theor Comput. 2013;9(7):3084-95. doi: 10.1021/ct400341p, PMID 26583988.

Mortier J, Rakers C, Bermudez M, Murgueitio MS, Riniker S, Wolber G. The impact of molecular dynamics on drug design: applications for the characterization of ligand-macromolecule complexes. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20(6):686-702. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.01.003, PMID 25615716.

Hashemzadeh H, Javadi H, Darvishi MH. Study of structural stability and formation mechanisms in DSPC and DPSM liposomes: a coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1837. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58730-z, PMID 32020000.

Sala D, Giachetti A, Rosato A. Insights into the dynamics of the human zinc transporter ZnT8 by MD simulations. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61(2):901-12. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c01139, PMID 33508935.

Arwansyah A, Arif AR, Syahputra G, Sukarti S, Kurniawan I. Theoretical studies of thiazolyl-pyrazoline derivatives as promising drugs against malaria by QSAR modelling combined with molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. Mol Simul. 2021;47(12):988-1001. doi: 10.1080/08927022.2021.1935926.

Foster M, Samman S. Zinc and Regulation of inflammatory cytokines: implications for cardiometabolic disease. Nutrients. 2012;4(7):676-94. doi: 10.3390/nu4070676.

Prasad AS. Effects of zinc deficiency on Th1 and Th2 cytokine shifts. J Infect Dis. 2000;182 Suppl 1:S62-8. doi: 10.1086/315916, PMID 10944485.

Maares M, Haase H. Zinc and immunity: an essential interrelation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016;611:58-65. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.03.022, PMID 27021581.

Muzzioli M, Stecconi R, Moresi R, Provinciali M. Zinc improves the development of human CD34+ cell progenitors towards NK cells and increases the expression of GATA-3 transcription factor in young and old ages. Biogerontology. 2009;10(5):593-604. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9201-3, PMID 19043799.

Mocchegiani E, Giacconi R, Cipriano C, Malavolta M. NK and NKT cells in aging and longevity: role of zinc and metallothioneins. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29(4):416-25. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9298-4, PMID 19408107.

Gregorio GV, Dans LF, Cordero CP, Panelo CA. Zinc supplementation reduced cost and duration of acute diarrhea in children. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(6):560-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.08.004, PMID 17493510.

Maret W. Zinc in cellular regulation: the nature and significance of “zinc signals”. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(11):2285. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112285, PMID 29088067.

Overbeck S, Rink L, Haase H. Modulating the immune response by oral zinc supplementation: A single approach for multiple diseases. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2008;56(1):15-30. doi: 10.1007/s00005-008-0003-8, PMID 18250973.

Maares M, Haase H. A guide to human zinc absorption: general overview and recent advances of in vitro intestinal models. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):762. doi: 10.3390/nu12030762, PMID 32183116.

Livingstone C. Zinc: physiology, deficiency, and parenteral nutrition. Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;30(3):371-82. doi: 10.1177/0884533615570376, PMID 25681484.

Chowanadisai W, Lonnerdal B, Kelleher SL. Identification of a mutation in SLC30A2 (ZnT-2) in women with low milk zinc concentration that results in transient neonatal zinc deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(51):39699-707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605821200, PMID 17065149.

Dufner-Beattie J, Weaver BP, Geiser J, Bilgen M, Larson M, Xu W. The mouse acrodermatitis enteropathica gene Slc39a4 (Zip4) is essential for early development and heterozygosity causes hypersensitivity to zinc deficiency. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(12):1391-9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm088, PMID 17483098.

Boezio B, Audouze K, Ducrot P, Taboureau O. Network-based approaches in pharmacology. Mol Inform. 2017;36(10):1-10. doi: 10.1002/minf.201700048, PMID 28692140.

Adnan M, Jeon BB, Chowdhury MH, Oh KK, Das T, Chy MN. Network pharmacology study to reveal the potentiality of a methanol extract of Caesalpinia sappan L. wood against type-2 diabetes mellitus. Life (Basel). 2022;12(2):277. doi: 10.3390/lIFE12020277, PMID 35207564.

Inoue Y, Hasegawa S, Ban S, Yamada T, Date Y, Mizutani H. ZIP2 protein, a zinc transporter, is associated with keratinocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(31):21451-62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.560821, PMID 24936057.

Liuzzi JP, Cousins RJ. Mammalian zinc transporters. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:151-72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132402. PMID 15189117.

Yang F, Silber S, Leu NA, Oates RD, Marszalek JD, Skaletsky H. TEX11 is mutated in infertile men with azoospermia and regulates genome-wide recombination rates in mouse. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7(9):1198-210. doi: 10.15252/EMMM.201404967, PMID 26136358.

Guiraldelli MF, Felberg A, Almeida LP, Parikh A, de Castro RO, Pezza RJ. SHOC1 is a ERCC4-(HhH)2-like protein, integral to the formation of crossover recombination intermediates during mammalian meiosis. PLOS Genet. 2018;14(5):e1007381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007381. PMID 29742103.

Jiang Y, Li T, Wu Y, Xu H, Xie C, Dong Y. GPR39 overexpression in OSCC promotes YAP-sustained malignant progression. J Dent Res. 2020;99(8):949-58. doi: 10.1177/0022034520915877, PMID 32325008.

Kambe T, Hashimoto A, Fujimoto S. Current understanding of ZIP and ZnT zinc transporters in human health and diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(17):3281-95. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1617-0, PMID 24710731.

Laitakari A, Liu L, Frimurer TM, Holst B. The zinc-sensing receptor GPR39 in physiology and as a pharmacological target. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8):3872. doi: 10.3390/IJMS22083872, PMID 33918078.

Maret W. Zinc and human disease. Met Ions Life Sci. 2013;13:389-414. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_12, PMID 24470098.

Fukada T, Yamasaki S, Nishida K, Murakami M, Hirano T. Zinc homeostasis and signaling in health and diseases: zinc signaling. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2011;16(7):1123-34. doi: 10.1007/S00775-011-0797-4, PMID 21660546.

Blaby-Haas CE, Merchant SS. Lysosome-related organelles as mediators of metal homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(41):28129-36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.592618. PMID 25160625.

Murdoch CC, Skaar EP. Nutritional immunity: the battle for nutrient metals at the host–pathogen interface. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20(11):657-70. doi: 10.1038/S41579-022-00745-6, PMID 35641670.

Yang H, Lou C, Sun L, Li J, Cai Y, Wang Z. AdmetSAR 2.0: web-service for prediction and optimization of chemical ADMET properties. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(6):1067-9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty707, PMID 30165565.

Lippens JL, Egea PF, Spahr C, Vaish A, Keener JE, Marty MT. Rapid LC-MS method for accurate molecular weight determination of membrane and hydrophobic proteins. Anal Chem. 2018;90(22):13616-23. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03843, PMID 30335969.

Nicze M, Borowka M, Dec A, Niemiec A, Bułdak L, Okopien B. The current and promising oral delivery methods for protein- and peptide-based drugs. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(2):815. doi: 10.3390/ijms25020815, PMID 38255888.

Jash A, Ubeyitogullari A, Rizvi SS. Liposomes for oral delivery of protein and peptide-based therapeutics: challenges, formulation strategies, and advances. J Mater Chem B. 2021;9(24):4773-92. doi: 10.1039/d1tb00126d, PMID 34027542.

Senel S, Kremer M, Nagy K, Squier C. Delivery of bioactive peptides and proteins across oral (buccal) mucosa. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2001;2(2):175-86. doi: 10.2174/1389201013378734, PMID 11480421.

Richard J. Challenges in oral peptide delivery: lessons learnt from the clinic and future prospects. Ther Deliv. 2017;8(8):663-84. doi: 10.4155/tde-2017-0024, PMID 28730934.

Mahmood A, FitzGerald AJ, Marchbank T, Ntatsaki E, Murray D, Ghosh S. Zinc carnosine, a health food supplement that stabilises small bowel integrity and stimulates gut repair processes. Gut. 2007;56(2):168-75. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.099929, PMID 16777920.

Chen D, Liu Z, Huang W, Zhao Y, Dong S, Zeng M. Purification and characterisation of a zinc-binding peptide from oyster protein hydrolysate. J Funct Foods. 2013;5(2):689-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.01.012.

M Chinonye Udechukwu, Stephanie A Collins, Chibuike C Udenigwe. Prospects of enhancing dietary zinc bioavailability with food-derived zinc-chelating peptides. Food Funct. 2016 Oct 12;7(10):4137-44. doi: 10.1039/c6fo00706f.

Udechukwu MC, Collins SA, Udenigwe CC. Prospects of enhancing dietary zinc bioavailability with food-derived zinc-chelating peptides. Food Funct. 2016;7(10):4137-44. doi: 10.1039/C6FO00706F, PMID 27713952.