Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 426-435Original Article

FORMULATION STRATEGY FOR STABLE POSACONAZOLE NANOEMULSION: APPLICATION OF PSEUDOTERNARY PHASE DIAGRAM IN PREFORMULATION DESIGN

MOHAMMED SADIK HAMZA1*, ZAINAB THABIT SALEH2

1University of Babylon, College of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmaceutics, Babylon, Iraq. 2University of Baghdad, College of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmaceutics, Baghdad, Iraq

*Corresponding author: Mohammed Sadik Hamza; *Email: mohammed.sadiq2200@copharm.uobaghdad.edu.iq

Received: 15 Mar 2025, Revised and Accepted: 18 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: posaconazole (PCZ), a potent broad-spectrum antifungal agent of the triazole class, is categorized as a Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS) Class II drug due to its poor aqueous solubility and limited oral bioavailability. Conventional PCZ formulations exhibit compromised therapeutic efficacy. This study aimed to develop and characterize an intravaginal nanoemulsion (NE) system as a novel drug delivery system (NDDS) to enhance PCZ solubility, avoid hepatic first-pass metabolism, and ensure rapid and complete drug release.

Methods: A systematic solubility screening of PCZ was conducted using various oils, surfactants, and co-surfactants. Pseudoternary phase diagrams were constructed to identify optimal NE regions. Based on these diagrams, multiple formulations were prepared and evaluated via visual inspection, thermodynamic stability, light transmittance, pH measurement, drug content, dilution test, and droplet size analysis.

Results: Among the tested formulations, F5 was optimized, demonstrating superior physicochemical characteristics. It showed the highest drug content (99.87%±0.20), a droplet size of (102.9±0.12 nm), a polydispersity index (0.28±0.008), and a zeta potential of (-29.45±0.09 mV). In vitro drug release revealed complete PCZ release (100%) within 150 min in citrate phosphate buffer (pH 4.5) with 1% Tween 80.

Conclusion: The optimized NE (F5), composed of 30% Imwitor 988, 30% S-mix (Tween 20: Transcutol, 1:1), 40% distilled water, and 1% PCZ, demonstrated excellent stability and a rapid drug release profile. Compared to clotrimazole-based vaginal tablets, which exhibit slower and incomplete drug release, this nanoemulsion offers enhanced solubility, efficient local delivery, and bypasses hepatic metabolism, making it a promising candidate for vaginal PCZ administration.

Keywords: Posaconazole, Nanoemulsion, Pseudo-ternary phase diagram, Droplet size

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.55055 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Vaginal candidiasis is a common fungal infection typically managed using either oral or vaginal dosage forms. Intravaginal therapy often includes the use of creams or vaginal pessaries. Although creams are generally preferred due to their ease of application and good spreadability, their greasy nature renders them unsuitable for vaginal use, often causing discomfort [1]. Likewise, vaginal pessaries may lead to irritation, inconvenience, or allergic reactions. Oral formulations, while effective, are frequently associated with systemic adverse effects such as cholestasis and hepatocellular damage [2].

In contrast, vaginally administered mucoadhesive formulations have emerged as a promising alternative, offering localized drug delivery with enhanced therapeutic outcomes. This improvement is attributed to high local perfusion, a large absorptive surface, and the avoidance of hepatic first-pass metabolism, all of which contribute to improved safety and efficacy [3]. Posaconazole (PCZ) is a potent antifungal medication from the triazole class. It is part of class II of BCS, and it works by inhibiting the enzyme lanosterol 14α-demethylase. Consequently, it inhibits the biosynthesis of ergosterol, an essential component of the fungal cell membrane, thereby weakening the structure and function of the fungal cell membrane, which is responsible for the antifungal activity of PCZ [4].

PCZ is marketed under the brand name Noxafil, available in various conventional dosage forms, including oral suspension, tablet, and injectable solution. However, these dosage forms do not offer a prolonged duration of action, which improves the efficacy of PCZ. Furthermore, the poor water solubility of PCZ caused low bioavailability. To improve the solubility of PCZ, nanoemulsion (NE) appeared to be a suitable approach. NE consists of oil and water phases stabilized by surfactants and co-surfactants, forming a thermodynamically unstable but kinetically stable system. Their droplet size typically ranges from 5 to 200 nm, and they may appear transparent or semi-transparent, depending on the formulation parameters [5]. These drug delivery systems are considered safe and well-tolerated when administered orally or applied topically to the skin and mucous membranes, making them an effective option for delivering locally acting medications. Nowadays, increasing drug loading and enhancing drug solubility and bioavailability are the most important advantages encouraging the usage of NE as drug delivery carriers. The very small size of NE provides a large surface area, which enhances the solubilization of the drug and facilitates penetration through the skin and epithelial layer [6, 7].

According to various studies, NEs exhibit superior drug solubilization potential compared to simple micellar systems. Additionally, their inherent thermodynamic stability provides significant benefits over less stable dispersions like emulsions and suspensions, as they require minimal energy for production (such as heat or agitation) and demonstrate an extended shelf life [8].

Several factors can influence the preparation of NEs. Firstly selection of the emulsifying agent (emulsifier) should be careful to achieve low interfacial tension, which is an important requirement for the stability of NE, it should be flexible enough or fluid to promote the formation, secondly sufficient concentration of surfactant must be used to produce a good stabilization for droplets in NE, and finally selection of the oil phase used in the formulation of NE should have excellent ability to dissolve the powdered drug [9].

NEs exhibit physical stability against sedimentation and creaming due to their small droplet size. However, Ostwald ripening remains a significant cause of instability, this process involves the migration of molecules from smaller to larger droplets, driven by differences in solubility and interfacial tension. The magnitude of this effect is influenced by the formulation composition and can be minimized through the careful selection of oils, surfactants, and co-surfactants [10].

This study aims to formulate PCZ to increase its solubility, better loading capacity, stability, and better patient compliance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Posaconazole was purchased from Hyper-Chem LTD CO, China. Labrafil M 1944 (LM 1944), Labrafact PG (LA PG), Labrasol ALF (LR ALF), Transcutol (TR), and Cremophor® EL were obtained from Gattefossé (France). Imwitor® 988 (IMW 988) and Miglyol® 812 N (MG812) were supplied by IOI Oleo GmbH (Germany). Propylene glycol (PG) and oleic acid (OA) were purchased from Hyper-Chem LTD CO. Natural oils, including castor, olive, rosemary, and sweet al. mond, were procured from Now Foods (USA).

Citric acid, disodium hydrogen phosphate, and Tween surfactants (grades 20, 40, and 80), along with polyethylene glycol (PEG) with molecular weights of 200, 400, and 600, were obtained from HiMedia Laboratories Ltd. (India). Methanol was sourced from LobaChemie Ltd. (India), and syringe filters were supplied by ChmLab (Spain). Dialysis membrane (MD34–5 M; flat width: 34 mm; molecular weight cutoff: 8000–14,000 Da) was acquired from MYM Biomedical Technology Co. (USA). Deionized distilled water (DD) and all other reagents used were of analytical grade.

Instruments used in the study included a water bath shaker (GFL, Karl Kolb, Germany) and a digital centrifuge (Hettich® EBA 20C, Germany). Glass centrifuge tubes were used during solubility screening. Particle size and zeta potential were measured using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, UK). UV absorbance was determined using a Shimadzu UV/VIS Spectrophotometer (UV-1700 PharmaSpec, Shimadzu®, Japan). pH measurements were conducted using a Hanna pH meter (Hanna Instruments®, Italy). Surface morphology and elemental composition were examined using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM-EDX, MIRA III, TESCAN®, Czech Republic).

Research on solubility

Labrafil M1944 (LM1944), Labrafact PG (LA PG), Miglyol 812 N (MG812), Imwitor 988(IMW988), oleic acid (OA), castor oil, rosemerry oil, sweet al. mond oil, and olive oil were among the oils studied to determine the PCZ solubility. Surfactants studied were Tween 20, 40, and 80, Cremophor EL (CE), and Labrasol ALF(LR). Transcutol (TR), PEG 200, PEG 400, PEG 600, and propylene glycol (PG) were used as co-surfactants, also determining the PCZ solubility in citrate phosphate buffer with 1% Tween 80, PH 4.5. In a water bath, each 2 ml of the listed substances with an excess amount of drug (PCZ) was shaken for 72 h (h) at 37±0.5 °C. After reaching equilibrium, the mixture was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was then diluted using methanol, and the concentration of PCZ was determined spectrophotometrically at 262 nm [11].

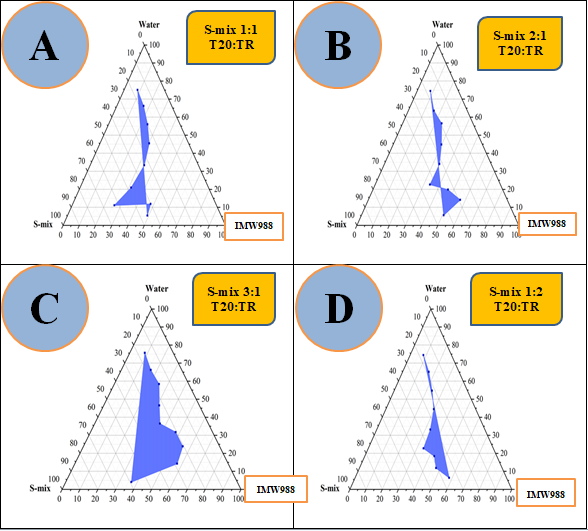

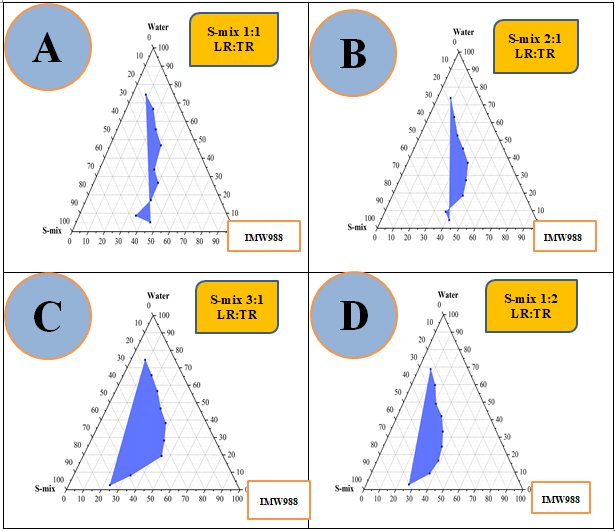

Productive of pseudo-ternary phase diagrams

Based on the solubility studies, IMW 988, Tween 20 (T20), Labrasol ALF (LR), and Transcutol (TR) were selected as the oil, surfactant, and co-surfactant, respectively, for the preparation of the NEs. Pseudo-ternary phase diagrams were constructed using the water titration method to identify the NE regions and select the optimal combination. Surfactant and co-surfactant, which are both represented as S-mix, were mixed at various weight ratios (1:1, 2:1, 3:1, and 1:2 w/w) to determine the phase diagram's productivity. For each ratio, oil was added and blended using a vortex mixer to form a mixture with nine different S-mix ratios (ranging from 1:9to9:1w/w). The homogeneous yellowish-transparent S-mix was titrated by adding distilled water (DD) slowly, drop by drop, with continuous gentle magnetic stirring. To verify the phase clarity, the mixture was visually inspected after each water addition. Titration was stopped once the system turned turbid or formed a viscous, gel-like texture. The percentage weights of oil, S-mix, and water in the mixture were then calculated to define the phase boundaries in each diagram, and the data were plotted using Original Lab software. The NE's area, which is considered to be visually clear, was the shaded one in a triangle plot with one apex representing the oil, the second one representing water, and the third representing the S-mix at a fixed weight ratio [12-14].

The method used for the preparation of NE

The phase inversion composition (PIC) method, also referred to as the self-nanoemulsification technique, has garnered significant attention across various fields, including pharmaceutical sciences. This method enables the formation of NEs at ambient temperature without the use of organic solvents or the application of heat. By gradually introducing water into an oil-surfactant mixture under gentle stirring while maintaining a constant temperature, kinetically stable NEs with fine droplet sizes can be successfully prepared [15].

Formulation of PCZ NE

As listed in table 1, numerous O/W NE formulations have been created by employing a water titration strategy by pseudo-ternary phase diagrams. To prepare 10 gm of 1% PCZ NE, the primary emulsion was produced by dissolving 100 mg of PCZ in IMW988 (the selected oil according to the solubility study) with an appropriate ratio of S-mix (T20 and TR) and (LR ALF and TR) both of which were previously weighed in a beaker and stirred continuously on the magnetic stirrer at room temperature (~ 500 rpm) for ten minutes until a clear solution was achieved. DD was then added to the clear solution with continuous stirring until a clear NE was formed. The prepared NEs were subjected to ultrasonic homogenization using a Power Sonic 410 probe sonicator (HWASHIN®, Korea) operating at 20 kHz frequency and 15% amplitude for 2 min. The process was carried out in a pulsed mode (2 seconds on, 2 seconds off) to minimize thermal stress. Immediately after sonication, the formulations were placed in an ice-cold beaker to ensure efficient cooling and to preserve formulation stability [16]. The resulting NEs were then transferred into clean glass tubes and stored at 4 °C for further evaluation. The derived final formula (F1–F40) underwent optimization and then characterization.

Optimization of NE

The prepared nanoemulsions were subjected to thermodynamic stability evaluation. Initially, each formulation was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 30 min. Formulations that showed no signs of phase separation were then subjected to six heating–cooling cycles between 4 °C and 45 °C, followed by three freeze–thaw cycles at −20 °C and 25 °C. Each cycle included a minimum storage period of 48 h at the respective temperature. Only formulations that passed all preliminary stability tests were selected for further physical characterization [17, 18].

Characterization of NEs

Particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), % transmittance, dilution test, drug content, morphological investigations, and drug release are considered only a few of the physicochemical criteria used to define or characterize the NE.

Particle size and polydispersity index measurement

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was employed using a Malvern Zeta sizer (UK) to determine the globule size and PDI of the NE formulations. A volume of 10 ml of distilled water (DD) was added to each 0.5 ml aliquot of the mixture before measurement to ensure appropriate dilution. For each formulation, the mean droplet size and PDI were recorded and reported [19, 20].

Percentage transmittance (T%)

The optical clarity of the formulated samples was evaluated using a Shimadzu UV-1700 PharmaSpec UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Japan). For each formulation, 1 ml was accurately diluted 1:100 with distilled water (DD), and measurements were performed at 650 nm, employing DD as the blank reference [21].

Dilution test

To evaluate the phase inversion behavior of the NE, a dilution study was conducted. Specifically, 1 ml of the optimized NE formulation was carefully mixed with 10 ml of distilled water (DD) in a test tube, and the mixture was closely monitored for any signs of phase inversion or instability [22].

Table 1: Composition of PCZ NE

| Formula code | IMW988 oil %(w/w) | Surfactant | Co-surfactant | S-Mix ratio | S-Mix % (w/w) | DD% (w/w) |

| F1 | 10 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 1:1 | 18 | 72 |

| F2 | 15 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 1:1 | 20 | 65 |

| F3 | 20 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 1:1 | 20 | 60 |

| F4 | 25 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 1:1 | 25 | 50 |

| F5 | 30 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 1:1 | 30 | 40 |

| F6 | 15 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 2:1 | 22 | 63 |

| F7 | 20 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 2:1 | 22 | 58 |

| F8 | 25 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 2:1 | 25 | 50 |

| F9 | 30 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 2:1 | 28 | 42 |

| F10 | 10 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 3:1 | 18 | 72 |

| F11 | 15 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 3:1 | 22 | 63 |

| F12 | 20 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 3:1 | 25 | 55 |

| F13 | 25 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 3:1 | 30 | 45 |

| F14 | 30 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 3:1 | 35 | 35 |

| F15 | 35 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 3:1 | 40 | 25 |

| F16 | 15 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 1:2 | 19 | 66 |

| F17 | 20 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 1:2 | 22 | 58 |

| F18 | 25 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 1:2 | 23 | 52 |

| F19 | 30 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 1:2 | 26 | 44 |

| F20 | 35 | Tween20 | Transcutol | 1:2 | 35 | 30 |

| F21 | 10 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 1:1 | 18 | 72 |

| F22 | 15 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 1:1 | 20 | 65 |

| F23 | 20 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 1:1 | 25 | 55 |

| F24 | 25 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 1:1 | 25 | 50 |

| F25 | 30 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 1:1 | 30 | 40 |

| F26 | 10 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 2:1 | 20 | 70 |

| F27 | 15 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 2:1 | 25 | 60 |

| F28 | 20 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 2:1 | 25 | 55 |

| F29 | 25 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 2:1 | 30 | 45 |

| F30 | 30 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 2:1 | 35 | 35 |

| F31 | 10 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 3:1 | 20 | 70 |

| F32 | 15 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 3:1 | 30 | 55 |

| F33 | 20 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 3:1 | 30 | 50 |

| F34 | 25 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 3:1 | 35 | 40 |

| F35 | 30 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 3:1 | 30 | 40 |

| F36 | 10 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 1:2 | 28 | 62 |

| F37 | 15 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 1:2 | 35 | 45 |

| F38 | 20 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 1:2 | 40 | 40 |

| F39 | 25 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 1:2 | 45 | 30 |

| F40 | 30 | Labrasol ALF | Transcutol | 1:2 | 45 | 25 |

*For all NE formulations (F1-F40), 10 gm of 1% PCZ was added to each formula.

Drug content measurement

A specific volume of the nanoemulsion (NE) formulation was taken and diluted in a suitable volumetric flask using a known amount of methanol to achieve an appropriate concentration for measurement. The diluted sample was then filtered through a 0.45 µm syringe filter to remove any impurities and undissolved particles. The drug content of PCZ in the filtered solution was measured using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer at the selected maximum wavelength (λ max = 262 nm) [23].

In vitro drug release study of posaconazole nanoemulsion

In vitro release profiles of PCZ-NE formulations (F5, F15, F18, F20, F25, F30, F34, and F40), which successfully passed the thermodynamic stability tests, were selected for further in vitro release evaluation. The study was performed using a USP dissolution apparatus II at 37±0.5 °C with continuous stirring at 50 rpm. A 1.5 ml sample (containing 15 mg of PCZ) from each NE was loaded into a dialysis bag (molecular weight: 8000–14,000 Da), which was immersed in a vessel containing 500 ml of citrate phosphate buffer (pH 4.5) with 1% Tween 80 [24].

At defined time intervals (5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min), 2 ml samples were withdrawn and replaced with 2 ml fresh medium to maintain sink conditions. The amount of PCZ released into the medium was quantified spectrophotometrically at 262 nm.

Zeta potential for optimized formulas

The zeta potential of the optimized formula (F5) was assessed to evaluate the stability of the NE by measuring its overall surface charge, whether positive or negative [25].

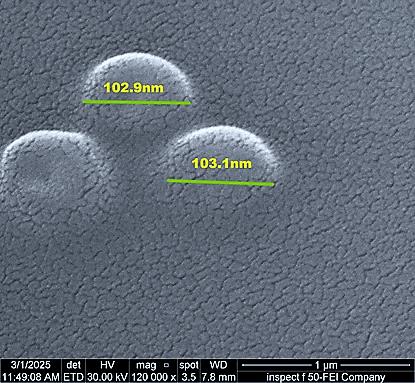

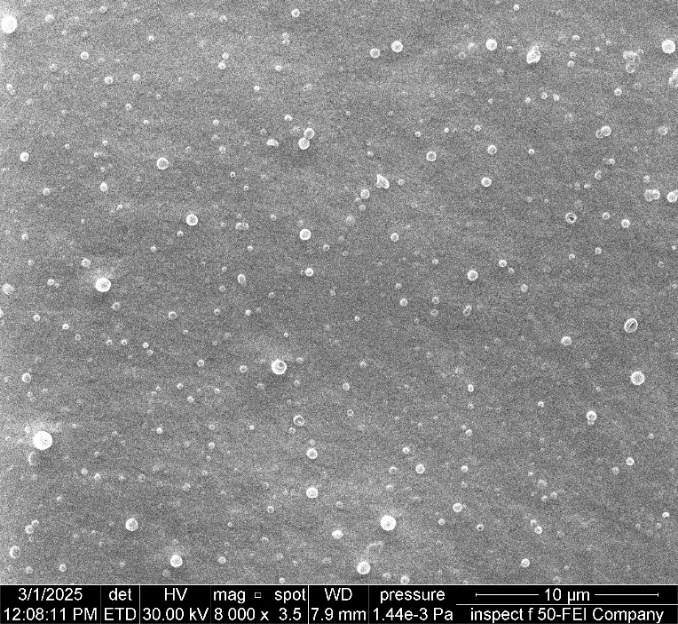

Field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM)

PCZ NE (F5) was examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM). It is a device for analyzing the surface roughness that is used to explain the size and shape of the droplets in the PCZ NE [26].

Statistical analysis

All experimental data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to compare the mean values of droplet size and in vitro drug release among the tested NE formulations. A p-value less than 0.05 (p<0.05) was considered statistically significant, while values greater than 0.05 (p>0.05) were regarded as non-significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Studies on solubility

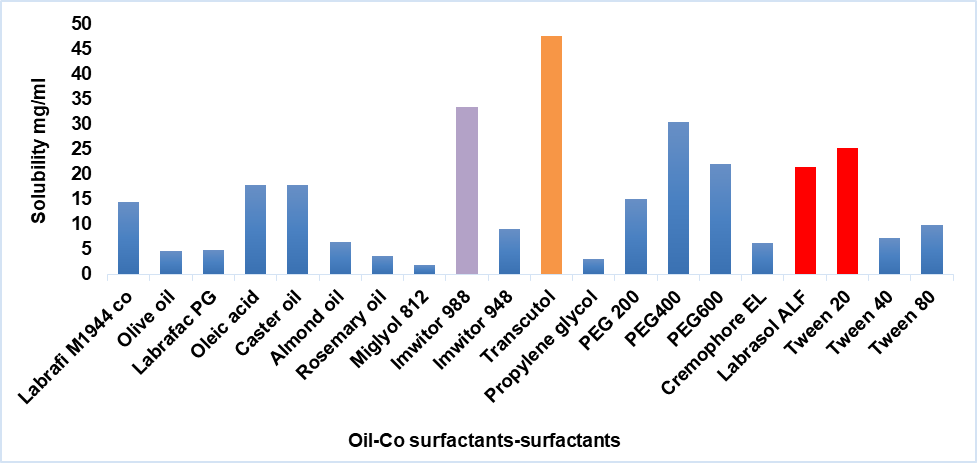

Fig. 1 displays the amount of PCZ soluble in various oils, surfactants, and co-surfactants. The results showed that IMW988, T20, and LR solubilize 33.477±2.05, 25.24±2.86, and 21.339±1.35 mg/ml of PCZ as an ideal oil and surfactant, respectively. The addition of a co-surfactant aimed at increasing the mixture's ability to load drugs; TR was chosen as a co-surfactant because of its effective solubilizing action (47.59±2.71 mg/ml).

Fig. 1: Graphical representation of PCZ solubility in various oils, surfactants, and co-surfactants prepared in this study

Excipient selection and safety justification for vaginal use

-Imwitor® 988 (Glyceryl Monocaprylate): Imwitor 988 was selected as the oil phase due to its superior solubilizing capacity for PCZ, showing the highest solubility among the tested oils. It also contributed to the physical stability of the NE during the stability study. It is used in vaginal pharmaceutical formulations and is considered safe and non-irritant [27].

-Tween® 20 (Polysorbate 20): Tween 20, a non-ionic surfactant, was selected based on its superior solubilizing capacity for PCZ among the tested surfactants. In addition to its emulsification efficiency in oil-in-water systems, it facilitates NE formation by reducing interfacial tension and enhancing droplet dispersion [28]. Tween 20 was chosen based on its documented safety and effectiveness in promoting drug release in Intravaginal delivery systems. Its role in enhancing the solubility and dissolution of poorly water-soluble drugs has been demonstrated in previous studies by Ball and Woodrow, 2014 [29]. Polysorbate 20 is listed in the FDA Inactive Ingredient Database and approved for use in vaginal formulations, confirming its regulatory safety for mucosal application [30].

-Transcutol® (diethylene glycol monoethyl ether) was selected as a cosurfactant due to its excellent ability to solubilize PCZ and form a stable NE with Tween 20 and Imwitor 988. It reduces interfacial tension and enhances droplet dispersion. Furthermore, Transcutol® is widely approved for pharmaceutical use in topical and mucosal applications, with a well-established safety profile. It has been used clinically without reports of adverse effects, even in pregnant women, confirming its suitability for use in this formulations [31].

Fig. 2: Pseudo-ternary phase diagrams of the IMW988, T20, and TR (S-mix) with water system were constructed at ambient temperature using S-mix weight ratios of 1:1 (A), 2:1 (B), 3:1 (C), and 1:2 (D)

The rational selection of formulation components plays a pivotal role in the successful development of NEs. A suitable oil phase, preferably one with high solubilizing capacity not only enhances drug solubility but also enables optimal drug loading. The surfactant, particularly those with high HLB values (>10), is essential for stabilizing oil-in-water systems and facilitating efficient drug entrapment within the hydrophobic core. Nonetheless, surfactants alone may be insufficient to achieve the desired reduction in interfacial tension. In such cases, co-surfactants are incorporated to disrupt rigid interfacial films, enhance fluidity, and promote the spontaneous formation of stable NEs [32].

Fig. 3: Pseudo-ternary phase diagrams of the IMW988, LR: TR (S-mix), and water system were constructed at ambient temperature using S-mix weight ratios of 1:1 (A), 2:1 (B), 3:1 (C), and 1:2 (D)

Table 2: Thermodynamic stability study result

F- code |

Centrifugation test | Heating-cooling cycle | Freeze-thaw cycle | F- code |

Centrifugation test | Heating-cooling cycle | Freeze-thawing cycle |

| F1 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F21 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- |

| F2 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F22 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- |

| F3 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F23 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- |

| F4 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F24 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- |

| F5 | pass | pass | pass | F25 | pass | Pass | pass |

| F6 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F26 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- |

| F7 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F27 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- |

| F8 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F28 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- |

| F9 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F29 | pass | fail (phase separation) | ----- |

| F10 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F30 | pass | Pass | pass |

| F11 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F31 | pass | fail (phase separation) |

---- |

| F12 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F32 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- |

| F13 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F33 | pass | fail (phase separation) | ----- |

| F14 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F34 | pass | Pass | pass |

| F15 | pass | pass | pass | F35 | pass | fail (phase separation) | ----- |

| F16 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F36 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- |

| F17 | pass | fail (phase separation) |

----- | F37 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ---- |

| F18 | pass | pass | pass | F38 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- |

| F19 | fail (phase separation) | ----- | ----- | F39 | pass | Pass | pass |

| F20 | pass | pass | pass | F40 | pass | Pass | pass |

*Note: "Pass" indicates no phase separation observed after the corresponding test. "Fail (phase separation)" indicates visible phase separation. (----) indicates that the formulation was not subjected to the test due to failure in a previous step. All tests were performed in triplicate.

Thermodynamic stability studies results

Thermodynamic stability studies were performed on all prepared NE formulations to ensure their robustness and suitability for further development. As detailed in table 2, all formulations showed signs of phase separation except for F5, F15, F18, F20, F25, F30, F34, F39, and F40, which remained physically stable without any visible phase separation, cracking, or significant changes in odor or color. These stable formulations were selected for subsequent characterization. Such assessments, which typically include centrifugation and freeze-thaw cycling, are crucial for identifying NEs capable of maintaining integrity under stress conditions [34].

Characterization of NEs

Droplet size measurement and polydispersity index (PDI)

The formulations that successfully passed the thermodynamic stability tests, specifically F5, F15, F18, F20, F25, F30, F34, F39, and F40, were selected for further evaluation and characterization. These NEs exhibited nanoscale dimensions, as shown in table 3, where the globule size was influenced by the oil content relative to different S-mix ratios. This integration potentially reduces the surface tension at the interfacial layer, leading to a smaller droplet curvature radius and promoting the formation of clear systems. Accordingly, the ratio of surfactant to co-surfactant plays a critical role in modulating droplet size [35]. For optimal formulation, the (PDI) should remain below 0.5, reflecting a consistent and narrow droplet size distribution [36]. The globule size increases significantly (p<0.05) with increasing concentration of IMW988, and the S-mix ratio also had a statistically significant impact on the particle size of NE (p<0.05).

Measuring percentage transmittance (T%)

The light transmission percentage (T%) of the formulations was measured. As shown in table 3, the formulations exhibited transmission values close to 100%, indicating excellent optical clarity and stability, which can be attributed to uniform droplet distribution within the NEs [37].

PH evaluation

The obtained results indicated that all the prepared NE were clear and had a pH value between (4.95-7.03), and this range of pH will be not irritant to the vagina [38].

Estimate of drug content

The prepared PCZNE formulation contained more than 95% of the drug, as shown in table 3. These formulations all met British pharmacopeia requirements and fell within a tolerable range (95.0%-105.0%), indicating that none of the prepared formulations had any drug precipitate [39].

Table 3: Droplet size, PDI, % T, Drug content, and PH of stable formulas

| Formula code | IMW 988 (w/w) % | S-mix Ratio | S-mix (w/w)% | Particle size (nm) | Polydispersity Index (PDI) |

Light transmittance (T%) | Drug Content% | PH |

| F5 | 30 | 1:1 | 30 | 102.9±0.12 | 0.28±0.008 | 97.7±0.001 | 99.87±0.2 | 5.12±0.2 |

| F15 | 35 | 3:1 | 40 | 294.8±0.47 | 0.88±0.09 | 94.6±0.003 | 95.15±0.4 | 4.95±0.15 |

| F18 | 25 | 1:2 | 23 | 145.5±0.42 | 0.34±0.02 | 95.8±0.001 | 96.75±0.45 | 5.17±0.25 |

| F20 | 35 | 1:2 | 35 | 134.8±0.63 | 0.24±0.019 | 96.1±0.006 | 96.37±0.2 | 5.66±0.1 |

| F25 | 30 | 1:1 | 30 | 312.5±0.55 | 0.15±0.01 | 92±0.004 | 95±0.32 | 5.81±0.4 |

| F30 | 30 | 2:1 | 35 | 300.2±0.33 | 0.25±0.016 | 93±0.002 | 96.1±0.6 | 6.39±0.2 |

| F34 | 25 | 3:1 | 35 | 280.1±0.53 | 0.23±0.088 | 94.2±0.001 | 97±0.1 | 5.79±0.6 |

| F39 | 25 | 1:2 | 45 | 216.5±0.22 | 0.19±0.05 | 92.1±0.003 | 96.8±0.5 | 6.99±0.3 |

| F40 | 30 | 1:2 | 45 | 278.7±0.43 | 0.24±0.02 | 93.5±0.002 | 95.9±0.3 | 7.03±0.2 |

*Data are expressed as mean±SD (n = 3).

Factors affecting particle size in the NE formula

Effect of oil concentration (IMW 988)

The oil phase (IMW 988) varied between 25%, 30%, and 35% across formulations. An increase in oil concentration generally led to an increase in particle size, as observed in F15 (294.8 nm containing 35% oil), F25 (312.5 nm containing 30% oil), and F30 (300.2 nm containing 30% oil). Conversely, formulations with lower oil concentrations, F18 (145.5 nm containing 25% oil), F39 (216.5 nm containing 25% oil), and F34 (280.1 nm containing 25% oil) showed smaller particle sizes. This trend suggests that higher oil content increases droplet size due to the greater internal phase volume, which challenges emulsification [40].

Effect of S-mix ratio and concentration

The effect of S-mix Ratio, Tween 20 (surfactant), and Transcutol (co-surfactant) works synergistically to reduce interfacial tension and stabilize oil droplets. At a F15 (3:1) ratio, the excess Tween 20 may not effectively integrate with Transcutol, leading to incomplete interfacial film formation around oil droplets. This reduces stabilization efficiency, allowing droplets to coalesce into larger particles (294.8 nm), while in F5(1:1) ratio, smaller particles(102.9 nm) [41].

Increasing the total S-mix concentration (e. g., from 30% to 45%) led to reduced particle size and PDI. For example, F39 (45% S-mix, 1:2 ratio) exhibited a relatively small size (216.5 nm) and low PDI (0.19) the quantitative ratio of a surfactant to a co-surfactant affects globule size differently [35]. Varying the S-mix ratio (surfactant: co-surfactant) also influenced droplet size: F5 (1:1) 102.9 nm, F18 (1:2) 145.5 nm, and F20 (1:2) 134.8 nm. These results indicate that the S-mix ratio needs to be optimized for each oil phase concentration to achieve minimal droplet size and a stable NE.

Effect on polydispersity index (PDI)

The lowest PDI (0.19) was recorded for F39 (Labrasol: Transcutol 1:2, 45% S-mix and 25% IMW988), indicating a highly uniform and monodisperse system. The highest PDI (0.88) was in F15, which had high oil (35%) and 40% S-mix in a 3:1 ratio, suggesting this composition resulted in a less stable and heterogeneous emulsion. The lower the homogeneity of the particles in the formulation, the higher the PDI [42]. The PDI for each formulation was less than 0.5, indicating a uniform and constrained globule size distribution.

Effect of particle size on transmitted light percentage (T%)

The droplet size of the NE plays a crucial role in determining its light transmittance percentage. Typically, smaller droplets in NEs tend to scatter less light, leading to higher transmittance values and thus producing clear emulsions. In contrast, larger droplets cause increased light scattering, which reduces the proportion of transmitted light, as reported by Drais HK and Hussein AA during their formulation of carvedilol NE in 2015 [37]. Nevertheless, this correlation is complex because various factors may also impact both droplet size and transmittance. These factors include the type and concentration of oil and surfactant, the preparation method of the NE, and the properties of the dispersed phase, as highlighted by Sakini SJ and Maraie NK in 2019[43]. According to the results presented in table 3, all developed formulations exhibited excellent clarity and efficient light transmission, with transmittance percentages approaching 100%. These findings are consistent with those reported by Jaiswal M in 2015, who developed NE as an advanced drug delivery system [44].

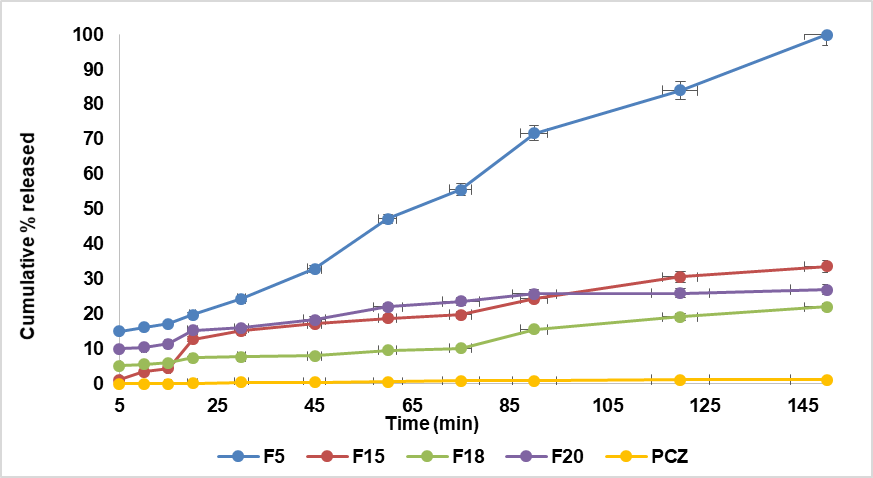

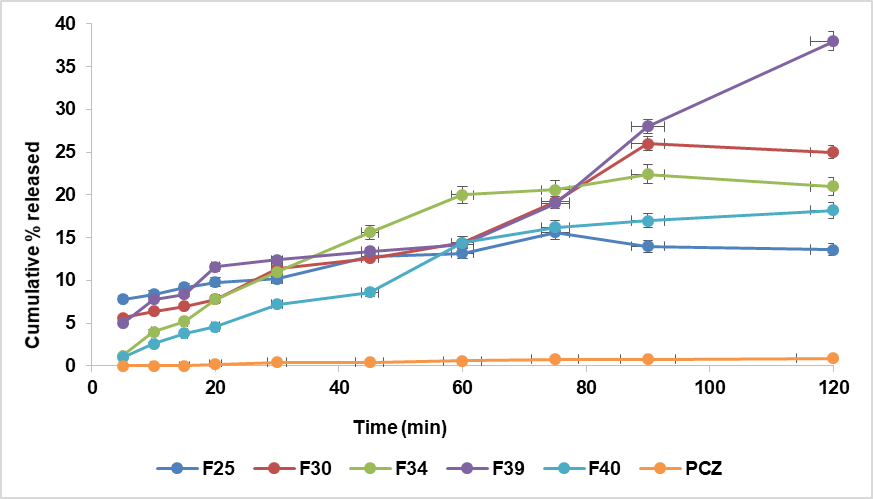

In vitro drug release study

The in vitro release profile of the prepared formulations is shown in fig. 4. The pure drug (PCZ) released 1.2% at the end of 150 min, while the drug released from NEs formula F5 at the end of 150 min was 100%, F15 (30.6%), F18(22%), and F20(15.6%). But at end 120 min F25(13.6%), F30 (13.8%), F34(19.8%),F39(38%), and F40(18.2%). Droplet size affects the drug's quantitative release from the NE formulation [45]. As the droplet size decreased, the cumulative percentage of drug released significantly increased (p<0.05). Therefore, the smallest droplet size observed in F5 resulted in the highest cumulative drug release.

A

B

Fig. 4: The S-mix: oil ratio influences the PCZ NE and pure medication release profiles. A-The S-mix T20: TR B-The S-mix LR: TR, *Data are presented as mean±SD (n = 3), with error bars representing standard deviation

The NE formula (F5) achieved 100% drug release within 150 min, indicating a rapid onset of action suitable for the acute management of vaginal candidiasis. This fast and complete release contrasts with conventional Intravaginal antifungal formulations, such as clotrimazole vaginal tablets reported by Rao et al. (2021), which exhibit a slower and incomplete release ranging from 61% to 78% over 8 h [46]. The superior dissolution efficiency of F5 is attributed to its droplet-based NE structure, which enhances drug solubility and diffusion. Unlike traditional formulations that may delay therapeutic action, F5 provides prompt and complete drug availability, positioning it as a promising alternative for rapid symptom relief in acute infections.

Selection of optimum formulas for PCZ NEs

Based on the characterization study’s findings, the prepared NE F5 was chosen as the best formula because of its good droplet size, PDI, T%, drug content, and high accumulation percentage in vitro release.

Zeta potential for optimized formula

The zeta potential of the optimized NE (F5) was –29.45±0.09 mV, slightly below the ±30 mV threshold typically associated with ideal electrostatic stability. However, the formulation demonstrated excellent physical stability, which is primarily attributed to steric stabilization provided by the non-ionic excipients Tween 20 and Transcutol. These surfactants form a stabilizing steric layer around the droplets that prevents their close approach and coalescence, ensuring NE stability regardless of the zeta potential value [47].

Field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM)

Fig. 5 shows that the optimized formula F5 exhibited a spherical shape with a particle size of (102.9±0.12 nm), confirming its nanoscale nature. The relatively small droplet diameter can be attributed to the incorporation of co-surfactant molecules into the surfactant layer, which reduces the fluidity and surface viscosity of the interfacial film. This action decreases the radius of curvature of the micro droplets, thereby enhancing transparency and contributing to the formation of clear NE systems [48]. To quantitatively support the morphological observation of spherical droplets, the sphericity index (SI) was calculated using the formula:

SI = 4π × (Area)/(Perimeter)2

Fifteen individual droplets were analyzed using ImageJ software, and the average sphericity was found to be 0.88±0.07, indicating a high degree of roundness and confirming the nearly spherical morphology of the droplets in F5.

|

|

| Mag 120,000 X | Mag 8,000 X |

Fig. 5: FESEM of optimized formula (NE F5)

Kinetics models of PCZ NE release

The mathematical model exhibiting the highest R² value was considered the most suitable for describing the release kinetics. The zero-order model demonstrated the strongest correlation (R² = 0.9458), followed by the first-order model (R² = 0.9122), the Higuchi model (R² = 0.9068), and the Korsmeyer–Peppas model (R² = 0.9099) with a slope (n) value of 0.8166, as detailed in table (4). The obtained n value suggests a combination of two transport mechanisms: Fickian diffusion and Case II transport, reflecting anomalous (non-Fickian) release kinetics. n controlled release systems, the drug release rate is generally influenced by a combination of diffusion and polymer relaxation mechanisms (Case II transport). For hydrophobic drugs in oil-in-water (O/W) NE systems, the release process involves multiple sequential steps, beginning with drug partitioning from the oil phase into the surfactant layer, followed by subsequent diffusion into the aqueous medium [49].

Table 4: The release kinetic modeling data mechanism of F5 (PCZ NE)

| Zero-order R2 | 1stOrder R2 | Higuchi model R2 | Korsmeyer –model R2 | n | Release mechanism |

| 0.9458 | 0.9122 | 0.9068 | 0.9099 | 0.8166 | Anomalous transport kinetics |

Although complete drug release was achieved within 150 min, the pattern of release remained consistent with zero-order kinetics, as the rate of drug release appeared nearly constant over time. The simultaneous fit to the Korsmeyer–Peppas model, with n = 0.8166, further supports a biphasic release mechanism initially characterized by rapid diffusion of surface-localized drug (burst release), followed by sustained release governed by matrix diffusion. This behavior aligns with the physicochemical nature of NEs, where both surface dynamics and internal diffusion pathways contribute to the overall release profile. Therefore, the zero-order model and the Korsmeyer–Peppas fit are not contradictory, but instead complementary representations of different phases in the same release process.

The model that yielded the highest coefficient of determination (R²), with a value approaching unity, was designated as the best-fitting kinetic model [50].

Zero-order kinetics is considered the optimal model for achieving sustained pharmacological effects because it represents a slow, controlled drug release profile. This kinetic model describes dosage forms that deliver a constant amount of drug per unit time, independent of concentration. It applies particularly when the drug diffusion rate is lower than the dissolution rate into the receptor medium, creating a saturated solution. As such, zero-order kinetics is commonly used to explain the release mechanisms in controlled dosage forms such as osmotic systems, matrix-based systems, or coated formulations. However, this model reflects an idealized scenario rarely encountered in practice, as it has limited adjustable parameters and inherent constraints. In contrast, first-order kinetics describes a release pattern where the drug release rate is directly proportional to the remaining drug content in the formulation. Accordingly, the amount of drug released per unit of time progressively declines as the release period advances.

The Higuchi model describes drug release as a diffusion-controlled process governed by Fick’s Law, where the amount of drug released is proportional to the square root of time (in hours). This model is particularly applicable to both water-soluble and poorly soluble drugs imgded within solid or semisolid matrices. However, the Higuchi equation has notable limitations, as it overlooks critical factors such as polymer swelling and relaxation that can influence drug transport. Although theoretically stronger than zero-and first-order models, the Higuchi model still overlooks key physicochemical factors affecting drug release [51].

When the primary release mechanisms involve a combination of drug diffusion (Fickian transport) and Case II transport (non-Fickian) governed by polymer relaxation phenomena, the semi-empirical Korsmeyer model is commonly applied to describe solute release. This model is particularly useful when the exact contributing factor is unknown or when drug release arises from a combination of relatively independent processes: one based on Fick’s Law-driven diffusion and the other resulting from hydrogel swelling and relaxation (dynamic expansion), which leads to a transition from a semi-rigid to a more fluid state, known as Case II transport. In this equation, both drug diffusion and hydrogel relaxation are considered determinant processes influencing drug release, thus taking into account the formulation’s structural characteristics [52]. However, due to the extremely small particle sizes involved, physical constraints often make it challenging to precisely define the drug release profile from colloidal carriers [53].

CONCLUSION

In this study, posaconazole NEs were successfully formulated using the pseudo-ternary phase diagram method. The phase diagrams facilitated the identification of optimal NE regions through variation in the proportions of oil, surfactant, co-surfactant, and water. The selected formulations exhibited desirable characteristics, including visual clarity, uniformity, and stability.

The findings demonstrate that the use of pseudo-ternary phase diagrams is an effective preformulation strategy for developing stable and transparent NEs. The optimized formulation enhanced the solubility and local availability of PCZ, presenting a promising alternative to conventional vaginal antifungal therapies. This NE system is expected to provide faster drug release, improved mucosal penetration, and potentially greater clinical efficacy with fewer systemic side effects.

Future work may include in vivo efficacy evaluation to further validate the therapeutic performance, along with quantitative assessment of mucoadhesive properties to optimize vaginal retention. Additionally, accelerated storage stability testing under conditions such as 40 °C/75% RH is recommended to support regulatory requirements and confirm the formulation’s robustness under stress conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are thankful to the University of Baghdad, College of Pharmacy, for their valuable support and guidance throughout the preparation of this manuscript.

FUNDING

As this is an original research article, no funding was received for this study.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Zainab Thabit Saleh supervised the research and guided the experimental design. Mohammed Sadik Hamza conducted the laboratory work, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the review and final editing of the article.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

Kumar K, Thorat YS, Kunjwani HK, Bindurani R. Formulation and evaluation of medicated suppository of clindamycin phosphate. Int J Biol Pharm Res. 2013;4(9):627-33.

Thorat YS, Hosmani AH. Treatment of mouth ulcer by curcumin loaded thermoreversible mucoadhesive gel: a technical note. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(10):399-402.

Afzaal H, Shahiq UZ Zaman, Saeed A, Hamdani SD, Raza A, Gul A. Development of mucoadhesive adapalene gel for biotherapeutic delivery to vaginal tissue. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1017549. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1017549, PMID 36249754.

US Food and Drug Administration. Noxa fil (posaconazole) prescribing information. In: Silver Spring, MD: FDA; 2014. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/205053s1lbl.pdf. [Last accessed on 15 Apr 2020].

Azeem A, Rizwan M, Ahmad FJ, Iqbal Z, Khar RK, Aqil M. Nanoemulsion components screening and selection: a technical note. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2009;10(1):69-76. doi: 10.1208/s12249-008-9178-x, PMID 19148761.

Patel MR, Patel RB, Parikh JR, Solanki AB, Patel BG. Effect of formulation components on the in vitro permeation of microemulsion drug delivery system of fluconazole. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2009;10(3):917-23. doi: 10.1208/s12249-009-9286-2, PMID 19609836.

Mohamed MI. Optimization of chlorphenesin emulgel formulation. American Association of Plastic Surgeons J. 2004;6(3):81-7. doi: 10.1208/aapsj060326.

Shafiq Un Nabi S, Shakeel F, Talegaonkar S, Ali J, Baboota S, Ahuja A. Formulation development and optimization using nanoemulsion technique: a technical note. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2007;8(2):28. doi: 10.1208/pt0802028, PMID 17622106.

Aulton ME, Taylor KM, editors. Chapter 27. Aulton’s pharmaceutics: the design and manufacture of medicines. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2018. p. 450-1.

Hamid KM, Wais M, Sawant G. A review on nanoemulsions: formulation composition and applications. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2021 Apr;14(4):22-8. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2021.v14i4.40859.

Zhou H, Yue Y, Liu G, Li Y, Zhang J, Gong Q. Preparation and characterization of a lecithin nanoemulsion as a topical delivery system. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2009;5(1):224-30. doi: 10.1007/s11671-009-9469-5, PMID 20652152.

Puppala RK, A VL. Optimization and solubilization study of nanoemulsion budesonide and constructing pseudo-ternary phase diagram. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019;12(1):551-3. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2019.v12i1.28686.

Almajidi YQ, Mahdi ZH, Maraie NK. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of montelukast sodium oral nanoemulsion. Int J App Pharm. 2018;10(5):49-53. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2018v10i5.28367.

Suminar MM, Jufri M. Physical stability and anti-oxidant activity assay of a nanoemulsion gel formulation containing tocotrienol. Int J Appl Pharm. 2017;9(1):140-3. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2017.v9s1.74_81.

Patel HC, Parmar G, Seth AK, Patel JD, Patel SR. Formulation and evaluation of O/W nanoemulsion of ketoconazole. PSM. 2013;4(4):338-51.

Mohamadi Saani SS, Abdolalizadeh J, Zeinali Heris S. Ultrasonic/sonochemical synthesis and evaluation of nanostructured oil in water emulsions for topical delivery of protein drugs. Ultrason Sonochem. 2019 Jul;55:86-95. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.03.018, PMID 31084795.

Patel G, Shelat P, Lalwani A. Statistical modeling optimization and characterization of solid self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system of lopinavir using design of experiment. Drug Deliv. 2016;23(8):3027-42. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2016.1141260, PMID 26882014.

Mundada VP, Sawant KS. Enhanced oral bioavailability and anticoagulant activity of dabigatranetexilate by self-micro emulsifying drug delivery system: systematic development in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo evaluation. J Nanomed Nanotechnol. 2018;9(1):1-13.

Alshahrani SM. Preparation characterization and in vivo anti-inflammatory studies of ostrich oil-based nanoemulsion. J Oleo Sci. 2019;68(3):203-8. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess18213, PMID 30760670.

Siddique AB, Ebrahim H, Mohyeldin M, Qusa M, Batarseh Y, Fayyad A. Novel liquid-liquid extraction and self-emulsion methods for simplified isolation of extra-virgin olive oil phenolics with emphasis on (-)-oleocanthal and its oral anti-breast cancer activity. PLOS One. 2019;14(4):e0214798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214798, PMID 30964898.

Pratiwi L, Fudholi A, Martien R, Pramono S. Design and optimization of self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems (SNEDDS) of ethyl acetate fraction from mangosteen peel. Int J PharmTech Res. 2016;9(6):380-7.

Maraie NK, Almajidi YQ. Application of nanoemulsion technology for preparation and evaluation of intranasal mucoadhesivenanoinsitu gel for ondansetron HCl. J Glob Pharm Technol. 2018;10(3):431-42.

Baloch J, Sohail MF, Sarwar HS, Kiani MH, Khan GM, Jahan S. Self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS) for improved oral bioavailability of chlorpromazine: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(5):210. doi: 10.3390/medicina55050210, PMID 31137751.

Shiva KY, Naveen KN, SharadaGoranti SKD. Development of intravaginal metronidazole gel for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis: effect of mucoadhesive natural polymers on the release of metronidazole. Int J PharmTech Res. 2010;2(3):1746-50.

Piazzini V, D Ambrosio M, Luceri C, Cinci L, Landucci E, Bilia AR. Formulation of nanomicelles to improve the solubility and the oral absorption of silymarin. Molecules. 2019;24(9):1688. doi: 10.3390/molecules24091688, PMID 31052197.

Affandi MM, Julianto T, Majeed A. Development and stability evaluation of astaxanthinnanoemulsion. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2011;4(1):142-8.

IOI Oleo GmbH. IMWITOR® 988 technical data sheet. Hamburg, Germany; 2020.

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PubChem compound summary for CID 443314, polysorbate 20. Bethesda: National Library of Medicine (US). Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Polysorbate-20.

Ball C, Woodrow KA. Electrospun solid dispersions of Maraviroc for rapid intravaginal preexposure prophylaxis of HIV. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(8):4855-65. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02564-14, PMID 24913168.

US Food and Drug Administration. Inactive ingredient database. In: Silver Spring, MD: FDA; 2025. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/iig/.

Musakhanian J, Osborne DW, Rodier JD. Skin penetration and permeation properties of transcutol® in complex formulations. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2024;25(7):201. doi: 10.1208/s12249-024-02886-8, PMID 39235493.

Amin N, Das B. A review on formulation and characterization of nanoemulsion. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2019;11(4):1-5. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2019v11i4.34925.

Kawakami K, Yoshikawa T, Hayashi T, Nishihara Y, Masuda K. Microemulsion of astaxanthinnanoemulsion. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2011;4(1):142-8.

Hanifah M, Jufri M. Formulation and stability testing of nanoemulsion lotion containing Centella asiatica extract. J Young Pharm. 2018;10(4):404-8. doi: 10.5530/jyp.2018.10.89.

Sadoon NA, Ghareeb MM. Formulation and characterization of isradipine as oral nanoemulsion. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2020;29(1):143-53. doi: 10.31351/vol29iss1pp143-153.

Hadi AS, Ghareeb MM. Rizatriptan benzoate nano-emulsion for intranasal drug delivery: preparation and characterization. IJDDT. 2022;2(2):546-52.

Drais HK, Hussein AA. Formulation and characterization of carvedilolnanoemulsion oral liquid dosage form. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(12):209-16.

Ahmad FJ, Alam MA, Khan ZI, Khar RK, Ali M. Development and in vitro evaluation of an acid buffering bioadhesive vaginal gel for mixed vaginal infections. Acta Pharm. 2008;58(4):407-19. doi: 10.2478/v10007-008-0023-2, PMID 19103575.

British Pharmacopoeia. XXX. London: Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency; 2016. p. 741.

An Y, Yan X, Li B, Li Y. Microencapsulation of capsanthin by self-emulsifying nanoemulsions and stability evaluation. Eur Food Res Technol. 2014;239(6):1077-85. doi: 10.1007/s00217-014-2328-3.

Mohammadi M, Elahimehr Z, Mahboobian MM. Acyclovir loaded nanoemulsions: preparation characterization and irritancy studies for ophthalmic delivery. Curr Eye Res. 2021;46(11):1646-52. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2021.1929328, PMID 33979552.

Elmataeeshy ME, Sokar MS, Bahey El Din M, Shaker DS. Enhanced transdermal permeability of terbinafine through novel nanoemulgel formulation; development in vitro and in vivo characterization. Future J Pharm Sci. 2018;4(1):18-28. doi: 10.1016/j.fjps.2017.07.003.

Sakini SJ, Maraie NK. Optimization and in vitro evaluation of the release of class II drug from its nanocubosomal dispersion. Int J Appl Pharm. 2019;11(2):86-90. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2019v11i2.30582.

Jaiswal M, Dudhe R, Sharma PK. Nanoemulsion: an advanced mode of drug delivery system. 3 Biotech. 2015;5(2):123-7. doi: 10.1007/s13205-014-0214-0, PMID 28324579.

Hamed SB, AbdAlhammid SN. Formulation and characterization of felodipine as an oral nanoemulsions. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2021;30(1):209-17. doi: 10.31351/vol30iss1pp209-217.

Rao MR, Paul G. Vaginal delivery of clotrimazole by mucoadhesion for treatment of candidiasis. J Drug Delivery Ther. 2021;11(6):6-14. doi: 10.22270/jddt.v11i6.5116.

Mc Clements DJ. Nanoemulsions versus microemulsions: terminology differences and similarities. Soft Matter. 2012;8(6):1719-29. doi: 10.1039/C2SM06903B.

Gao ZG, Choi HG, Shin HJ, Park KM, Lim SJ, Hwang KJ. Physicochemical characterization and evaluation of a microemulsion system for oral delivery of cyclosporin A. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 1998;161(1):75-86. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(97)00325-6.

Youssef AA, Cai C, Dudhipala N, Majumdar S. Design of topical ocular ciprofloxacin nanoemulsion for the management of bacterial keratitis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021;14(3):210. doi: 10.3390/ph14030210, PMID 33802394.

Barradas TN, Senna JP, Cardoso SA, De Holanda E Silva KG, Elias Mansur CR. Formulation characterization and in vitro drug release of hydrogel thickened nanoemulsions for topical delivery of 8-methoxypsoralen. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2018;92:245-53. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.06.049, PMID 30184748.

Geeva Prasanth A, Sathish Kumar A, Sai Shruthi B, Subramanian S. Kinetic study and in vitro drug release studies of nitrendipine loaded arylamide grafted chitosan blend microspheres. Mater Res Express. 2019;6(12). doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/ab5811.

Karthikeyan M, Deepa MK, Bassim E, Rahna CS, Sree Raj KR. Investigation of kinetic drug release characteristics and in vitro evaluation of sustained release matrix tablets of a selective COX-2 inhibitor for rheumatic diseases. J Pharm Innov. 2020 Jun;16:551-7. doi: 10.1007/s12247-020-09459-9.

Magalhaes NS, Cave G, Seiller M, Benita S. The stability and in vitro release kinetics of a clofibride emulsion. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 1991;76(3):225-37. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(91)90275-S.