Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 367-380Original Article

MOLECULAR DOCKING AND GRAPHICAL TRAJECTORY ANALYSIS OF CINNAMOMUM ZEYLANICUM COMPOUNDS FOR TARGETING HUMAN MALTASE-GLUCOAMYLASE IN DIABETES MANAGEMENT

VYSHNAVI VISHWANADHAM RAO1,2*, KOPPALA NARAYANAPPA SHANTI2, DINESH SOSALAGERE MANJEGOWDA3

1Department of Chemistry, MES College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Bengaluru-560003, India. 2Department of Biotechnology, PES University, Bengaluru-560085, India. 3Department of Human Genetics, School of Basic and Applied Sciences, Dayananda Sagar University, Bengaluru-560078, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Vyshnavi Vishwanadham Rao; *Email: vyshu.23vrao@gmail.com

Received: 23 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 08 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Maltase-glucoamylase is an essential enzyme involved in the final hydrolysis of dietary carbohydrates into glucose, facilitating postprandial glucose absorption. Its heightened activity exacerbates glucose spikes, a hallmark of type 2 diabetes, making it a pivotal target for therapeutic intervention. This research aims to explore the inhibitory potential of phytocompounds from Cinnamomum zeylanicum as promising enzyme inhibitors, with acarbose serving as a reference standard.

Methods: Eighteen phytocompounds were screened via molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Binding affinity, residue interactions, and structural stability were assessed, alongside pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiling using absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) tools.

Results: Alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran emerged as top candidates with binding energies of-10.21 and-10.17 kcal/mol, respectively, surpassing acarbose (-9.11 kcal/mol). Interaction analysis revealed that alpha-cadinol formed hydrogen bonds with TYR A: 1251 and GLY A: 1588, while cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran engaged residues such as HIS A: 1710 and THR A: 1699 through a combination of hydrogen bonding and aromatic interactions. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed the stability of these complexes, with root mean square deviation values of 0.33 nm for alpha-cadinol and 0.34 nm for cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran, comparable to acarbose. Reductions in solvent accessibility and root mean square fluctuation further demonstrated the stabilising effects of these compounds on the enzyme. Pharmacokinetic profiling revealed favourable absorption and bioavailability for both compounds, suggesting their suitability as oral therapeutics.

Conclusion: These findings highlight alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran as potential alternatives to acarbose with possibly improved safety and efficacy profiles. However, in vitro and in vivo validation is necessary to confirm their therapeutic applicability and establish their metabolic stability. This study offers a significant step toward developing novel enzyme inhibitors for effective diabetes management and paves the way for future experimental and clinical exploration.

Keywords: Alpha-cadinol, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Diabetes management, In silico, Maltase-glucoamylase inhibition, Molecular dynamics, Molecular docking, Phytocompounds

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55175 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) remains a global public health burden with escalating prevalence, morbidity, and economic impact [1, 2]. According to the International diabetes federation (IDF), approximately 537 million adults (ages 20–79) were living with diabetes in 2021, accounting for 10.5% of the global adult population. This number is projected to reach 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045, with over 75% of cases concentrated in low-and middle-income countries [3, 4]. In India, lifestyle transitions have driven DM incidence to an anticipated 69.9 million by 2025, necessitating innovative disease management strategies [5]. DM is characterized by chronic hyperglycemia due to impaired insulin secretion and/or action [6]. Among the enzymes involved in glucose metabolism, human maltase-glucoamylase (MGAM) is pivotal in hydrolysing α-1,4 glycosidic bonds of oligosaccharides to yield glucose [7, 8]. Hyperactivity of MGAM contributes to postprandial hyperglycemia, a defining feature of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), making MGAM inhibition a promising therapeutic strategy [6].

Pharmacological inhibitors like acarbose and miglitol target al. pha-glucosidases, including MGAM, to control glucose surges [9, 10]. However, their gastrointestinal side effects (e. g., bloating, diarrhea) due to undigested carbohydrates have led to a growing interest in plant-derived alternatives with better tolerability [9-11]. Cinnamomum zeylanicum (cinnamon), widely known for its antidiabetic potential, contains compounds such as cinnamaldehyde and procyanidins that have demonstrated glycemic regulatory effects [12, 13].

Computational approaches, including molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, have emerged as powerful tools to screen and validate novel enzyme inhibitors. Studies have reported potent anti-diabetic interactions from phytocompounds targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) (e. g., Punigluconin) [14], sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) and insulin receptors (e. g., herbacetin, sorbifolin) [15], and α-glucosidases (e. g., (4Z,12Z)-cyclopentadeca-4,12-dienone from Grewia hirsuta) [16]. Despite growing evidence supporting the antidiabetic potential of phytocompounds, limited research has comprehensively explored the inhibitory interactions between Cinnamomum zeylanicum bark constituents and MGAM, a critical enzymatic target in postprandial glucose regulation. While previous studies have employed computational approaches on various diabetes-related targets, a focused in silico investigation of MGAM inhibition by bioactive molecules from cinnamon bark remains unexplored. Therefore, the present study introduces a novel direction by integrating molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to systematically evaluate the binding affinity, stability, and interaction profiles of these phytocompounds with MGAM. This in silico approach aims to identify promising, plant-derived MGAM inhibitors, contributing to the development of safer, more tolerable therapeutic alternatives for T2DM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retrieval and preparation of ligands

The structural data for bioactive compounds from Cinnamomum zeylanicum were obtained from the PubChem database to target MGAM. The standard inhibitor, Acarbose, was also retrieved from PubChem and utilised as a reference for comparative analysis. Ligand preparation for virtual screening was conducted using OpenBabel Cheminformatics software, where energy minimisation was applied with the universal force field (UFF) to achieve stable, low-energy conformations. This step was critical for optimising the three-dimensional structures, reducing steric hindrances, and ensuring reliable docking interactions. The prepared ligands were subsequently used for computational evaluation [17].

Preparation of MGAM structure

The crystal structure of the c-terminal subunit of human MGAM complexed with acarbose (PDB ID: 3TOP) was retrieved from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB), a database providing detailed structural information of biological macromolecules (https://www.rcsb.org). This structure was chosen for its high-resolution X-ray diffraction data (2.88 Å), ensuring accuracy in subsequent computational studies. The structure was reported with no mutations and was characterised as a monomer with global stoichiometry A1. Preparation of the MGAM target was conducted using PyMOL a molecular visualization system. Non-structural elements, such as water molecules, were meticulously removed to prevent interference during docking analysis. Polar hydrogen atoms were then added to ensure proper hydrogen bonding and interaction accuracy. This was essential to create a realistic simulation environment that reflects physiological conditions. The prepared MGAM structure was subsequently utilised for advanced molecular docking and dynamic simulation analyses to assess ligand binding [17].

Validation of MGAM structure

The prepared structure of MGAM was subjected to structural validation to ensure its suitability for computational studies. Ramachandran plot analysis was performed using the structure assessment module of the SwissModel,, a tool that provides a comprehensive evaluation of protein structures by assessing backbone dihedral angles (phi and psi) of amino acid residues. This analysis identifies conformational outliers and verifies the stereochemical quality of the protein, confirming the stability and accuracy of the model. The Ramachandran plot generated in this study provided insight into the allowed and disallowed regions of the protein’s conformational space. The secondary structures of the prepared MGAM were further analysed using ProMotif, which identifies and categorizes secondary structural elements, such as alpha helices and beta strands, and provides a detailed assessment of the protein’s structural motifs. This analysis was essential to understand the folding and structural integrity of MGAM, which plays a crucial role in ligand interactions. To evaluate the hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions of MGAM, the ProtScale (https://web.expasy.org/protscale/) tool was employed. ProtScale calculates the hydropathy index across the amino acid sequence, facilitating an understanding of the protein's surface characteristics and potential interaction sites [17].

Virtual Screening of Cinnamomum zeylanicum phytocompounds against HMGA

Molecular docking studies were conducted using AMDock v.1.5.2, a comprehensive software platform that utilizes the AutoDock engine for precise molecular docking simulations. This tool integrates auxiliary software such as Open Babel and PyMOL for pre-docking structural preparation and post-docking analysis. AMDock was chosen for its robust docking capabilities, streamlined interface, and efficient handling of both ligand and target structures, ensuring accurate and reproducible results. The docking analysis evaluated binding affinities (expressed in kcal/mol), predicted inhibition constants (Ki), and ligand efficiency. Ki values were calculated using AutoDock Vina's scoring function with the formula: Ki = exp(ΔG/RT), where ΔG is the binding free energy, R is the universal gas constant (1.985 × 10-3 kcal mol-1K-1), and T is the absolute temperature (298.15 K) [18]. This conversion of binding energy to Ki provided an estimate of the ligand’s inhibitory potential. Compounds were ranked based on their binding affinities, with the most negative binding energy (ΔG) and the lowest Ki values indicating the strongest binding interactions. To validate the docking protocol, a redocking experiment was performed using the co-crystallized ligand acarbose into its original binding site within 3TOP. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the redocked and original acarbose pose was 1.87 Å, confirming the reliability of the docking setup. The binding affinity reported for acarbose in this study represents the average of both original docking and redocking analyses. The validated protocol was then used to dock 18 phytocompounds derived from Cinnamomum zeylanicum using a grid box [19].

ADME profiling of the top compounds

Pharmacokinetic analysis is a crucial step in evaluating novel drug-like compounds as it provides insight into their absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiles. Understanding these properties is essential to predict the behavior of a compound within a biological system, ensuring that it possesses the necessary characteristics to become a safe and effective therapeutic agent. Performing in silico ADMET analysis early in the drug discovery process helps streamline the identification of promising candidates by eliminating compounds with poor pharmacokinetic profiles before costly in vitro and in vivo testing. This enhances efficiency and reduces the time and resources needed for drug development [18].

In the present study, based on the docking affinities observed, the top two compounds were subjected to in silico absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) analysis using the SwissADME web server (https://www.swissadme.ch/), a widely recognised tool for evaluating drug-like properties. SwissADME provides comprehensive predictions related to a compound’s pharmacokinetics, physicochemical properties, and drug-likeness by employing advanced algorithms and validated computational models [19]. The tool’s primary function is to assess various parameters, including lipophilicity, solubility, permeability, and potential metabolic pathways. SwissADME integrates multiple prediction models for assessing gastrointestinal absorption and p-glycoprotein substrate potential, which contribute to understanding a compound’s bioavailability and safety profile.

Toxicity profiling of the top compounds

Toxicity prediction is an essential step in drug design, offering crucial insights into the safety profile of potential therapeutic candidates. Computational toxicity assessments provide significant advantages over traditional animal testing by enabling faster, cost-effective evaluations while supporting the reduction of animal use, aligning with ethical research standards. In this study, the ProTox 3.0 web server (https://tox.charite.de/protox3/) was employed to predict the toxicity of the top two compounds with the highest binding to MGMA compounds. ProTox 3.0 integrates models based on molecular similarity, pharmacophore-based, fragment-based, and machine-learning algorithms to estimate compound toxicity. Toxicity is represented as LD50 (lethal dose 50%), expressed in mg/kg body weight, indicating the dose at which 50% of test subjects succumb [20]. This metric is key for classifying compounds according to the globally harmonised system for chemical labelling.

Molecular dynamics simulation

MD simulations were conducted on the crystal structure of the C-terminal subunit of MGAM complexed with acarbose (PDB ID: 3TOP) to explore the stability and dynamic behaviour of protein-ligand interactions. The selected top ligands from the docking analysis, identified as Drug1 (3TOP-TOP1), Drug2 (3TOP-TOP2), and the standard reference drug (3TOP-STD), were included for further analysis [22].

a. System preparation

The ligand topologies were generated using the automated topology builder (ATB) server to ensure compatibility with the Groningen machine for chemical simulations (GROMACS) software, which was employed for MD simulations. The initial protein-ligand complexes were prepared using the pdb2 gmx module in GROMACS, which added hydrogen atoms to the heavy atoms and ensured proper protonation states. The systems were energy-minimised for 1500 steps using the steepest descent algorithm to remove steric clashes and optimise the overall geometry of the complexes [23]. The chemistry at Harvard macromolecular mechanics 27 (CHARMM27) force field was used for protein parameterisation.

b. Solvation and ionic neutralisation

The energy-minimised structures were solvated in a cubic periodic box using the simple point charge (SPCE) water model, which accurately represents water behaviour in simulations. To mimic physiological conditions, Na+and Cl-ions were added to maintain an ionic concentration of 0.15 M, ensuring neutralisation of the system [24].

c. Equilibration and production run

Equilibration was performed in two phases: NVT (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) and NPT (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) ensembles. These phases allowed the system to adapt gradually to simulated conditions, verifying temperature and pressure stability. The NVT equilibration was performed for 100 ps using the V-rescale thermostat at 300 K, followed by 100 ps of NPT equilibration using the Parrinello–Rahman barostat at 1 bar pressure. Each complex was then subjected to a 300 ns production run in the NPT ensemble to simulate the long-term dynamic behaviour of the protein-ligand systems [22]. A time step of 2 femtoseconds (fs) was used for all simulations, with periodic boundary conditions and long-range electrostatics handled using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method. All bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms were constrained using the LINCS algorithm.

Trajectory analysis

a. Root mean square deviation (RMSD)

RMSD analysis was performed to evaluate the stability of the protein-ligand complexes over the simulation time. RMSD measures the average deviation of the backbone atoms from their initial positions, indicating the system’s equilibration and structural changes post-ligand binding. A stable RMSD profile suggests that the complex has reached equilibrium, while large deviations indicate potential conformational instability [25].

b. Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF)

RMSF analysis was conducted to assess the flexibility of individual amino acid residues in the protein. RMSF provides insights into which regions of the protein exhibit high mobility, often correlating with active or binding sites. Residues with high RMSF values suggest flexible regions, whereas low RMSF values indicate structurally stable areas [25].

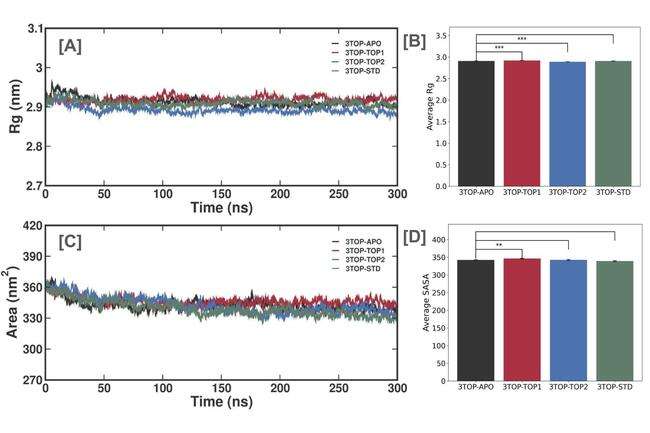

c. Radius of gyration (Rg)

The Rg analysis was used to examine the compactness of the protein throughout the simulation. Rgreflects the distribution of atoms around the centre of mass, providing insights into the folding state and structural stability. A consistent Rg value over the simulation indicates that the protein maintains its structural integrity, whereas significant variations could signal partial unfolding or conformational shifts due to ligand interactions [25].

d. Solvent accessible surface area (SASA)

SASA was calculated to monitor changes in the surface area exposed to the solvent during the simulation. This analysis helps determine how ligand binding affects the protein’s interaction with the surrounding environment. A decrease in SASA suggests that the ligand induces conformational changes, potentially reducing surface exposure, while an increase could imply structural relaxation or an opening of active sites [25].

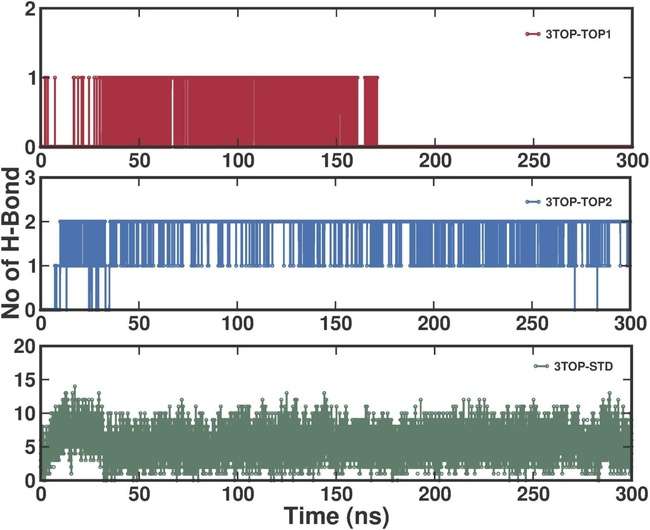

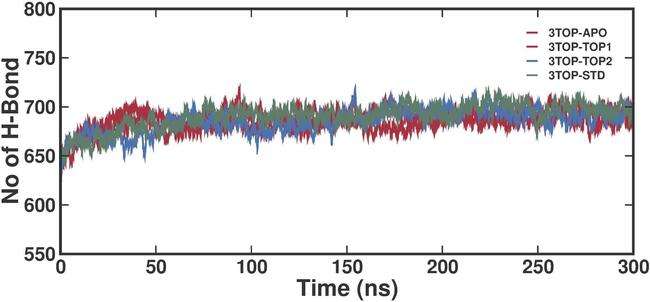

e. Hydrogen bond analysis

Hydrogen bond analysis was performed to evaluate the strength and stability of the interactions between the protein and ligands, as well as within the protein itself. Stable hydrogen bonds contribute significantly to the binding affinity and specificity of the ligand. The analysis included counts of both intermolecular (protein-ligand) and intramolecular (within the protein) hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation [25].

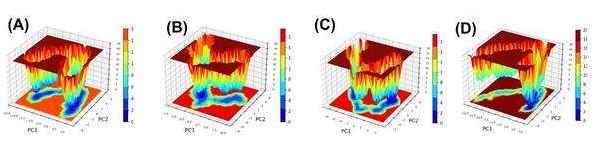

f. Principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA was used to identify the major conformational changes and movement patterns within the protein. This method reduces multidimensional trajectory data into principal components, highlighting dominant motions that reflect significant structural transitions. PCA aids in understanding how ligand binding may alter the global protein dynamics and conformational landscape [25].

g. Free energy landscape (FEL)

FEL analysis was conducted to visualize the conformational space sampled by the protein-ligand complexes over the simulation period. This analysis maps the energy states of the protein, with low-energy basins indicating stable conformations. FEL helps identify the most stable conformational states and understand the potential energy barriers between different states [25].

h. Binding free energy calculation

The Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) approach was employed to estimate the binding free energy of the protein-ligand complexes. The g_mmpbsa utility in GROMACS was used to calculate this energy over the last 50 ns of the simulation with sampling at 1000-frame intervals. This analysis provided a comprehensive understanding of the ligand’s binding efficacy, further validating the interactions observed during the simulation [25].

RESULTS

Validation of the MGMA target

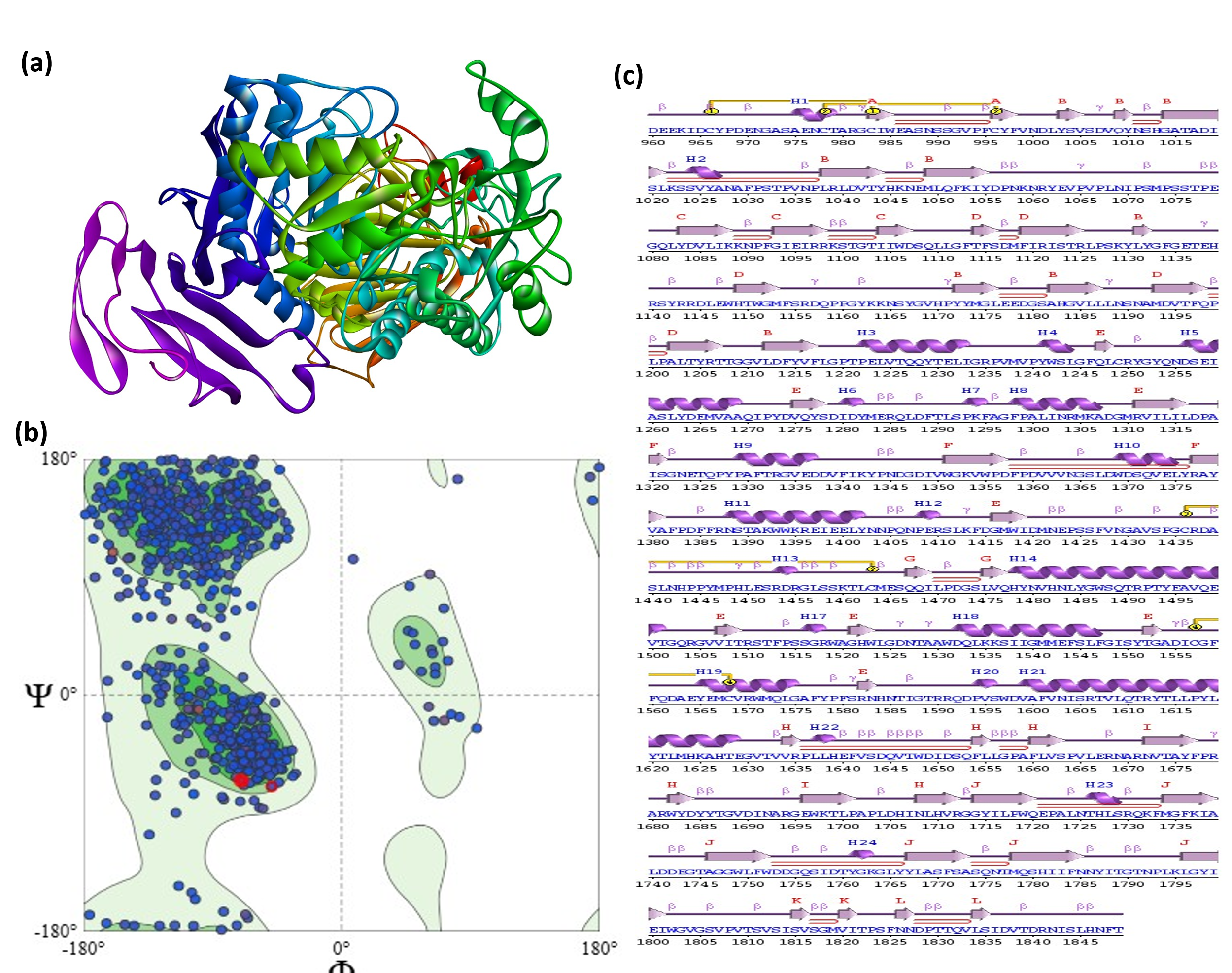

The structural validation of the MGAM (fig. 1a) protein was performed using tools integrated within the SwissModel structure assessment suite. The Ramachandran plot analysis revealed (fig. 1b) that 84.46% of residues lie in the most favoured regions, with only 3.27% in outlier regions, indicating satisfactory stereochemical quality. Additionally, the structure exhibited 2 C-beta deviations, suggesting minimal side-chain steric strain. The model also achieved a QMEANDisCo Global score of 0.91±0.05, reflecting high overall confidence in both local and global structural geometry. Secondary structure analysis from ProMotif highlights a robust composition with 24 helices, 12 beta-sheets, 49 strands, 95 beta-turns, and 4 disulfide bonds, characteristic of a mixed alpha-beta fold typical for enzymes (fig. 1c). These structural features indicate a stable and functional protein fold capable of supporting extensive ligand interactions. While minor deviations, such as the single disallowed residue and unusual dihedral scores, exist, they are not expected to significantly affect docking or molecular dynamics simulations and may even provide beneficial flexibility for ligand binding. The validated MGAM structure was used for subsequent computational analyses, including molecular docking and trajectory simulations, with the structural metrics affirming its integrity and suitability for investigating protein-ligand interactions.

Virtual screening

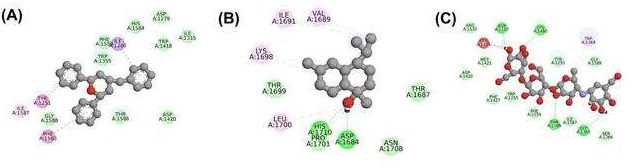

In this study, 18 bioactive compounds from the methanolic extract of Cinnamomum zeylanicum were screened against MGAM using molecular docking. The primary objective was to compare the binding interactions and affinities of these phytocompounds with the standard drug (STD) acarbose. Docking analyses identified alpha-cadinol (TOP1) and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran (TOP2) as the top-performing ligands, with docking scores of-10.21 kcal/mol and-10.17 kcal/mol, respectively, both surpassing the binding affinity of acarbose (-9.11 kcal/mol) (table 1). These results suggest that the identified phytocompounds possess superior inhibitory potential against MGAM compared to the standard. The docking interactions highlight diverse stabilising forces, including hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts. For TOP1 (alpha-cadinol), key residues such as TRP A: 1355, PHE A: 1560, and HIS A: 1584 played a crucial role in ligand stabilisation through aromatic interactions. Similarly, TOP2 (cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran) demonstrated robust binding involving residues like HIS A: 1710, ASP A: 1684, and LEU A: 1700, reflecting its ability to form strong hydrogen-bond networks and hydrophobic interactions within the MGAM active site. Comparatively, acarbose (STD) showed weaker binding interactions, relying primarily on residues such as ARG A: 1510 and ASP A: 1157 to stabiliseits complex (fig. 2).

Fig. 1: Comprehensive structural validation of the MGAM target protein, (a) 3D ribbon representation of the MGAM protein, illustrating a mixed alpha-beta fold with distinct helices and beta-sheets critical for enzymatic function. (b) Ramachandran plot showing backbone dihedral angle distribution, with 84.46% of residues in most favored regions and 3.27% in outlier regions, confirming acceptable stereochemical quality. (c) Detailed secondary structure analysis reveals a rich composition of 24 helices, 12 beta-sheets, 49 strands, 95 beta-turns, and 15 gamma-turns, along with 4 disulfide bonds

Table 1: Binding affinities and residue interactions of phytocompounds and acarbose with MGAM

| Ligand ID | Docking score (kcal/mol) | Ligand name | Key interacting residues |

| 3TOP-TOP1 | -10.21 | alpha-cadinol | ILE A: 1251, PHE A: 1560, GLY A: 1588, TYR A: 1587, ASP A: 1279, HIS A: 1584, TRP A: 1355, THR A: 1586, ASP A: 1420. |

| 3TOP-TOP2 | -10.17 | cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran | ILE A: 1691, VAL A: 1689, LYS A: 1698, LEU A: 1700, THR A: 1699, HIS A: 1710, ASP A: 1684, ASN A: 1708. |

| 3TOP-STD | -9.11 | acarbose | ARG A: 1510, ASP A: 1157, SER A: 1421, LYS A: 1460, TYR A: 1251, GLY A: 1588, PHE A: 1359, THR A: 1586, MET A: 1420. |

Fig. 2: Visualization of protein-ligand interactions for top phytocompounds and standard drug, The 2D interaction maps illustrate the binding interactions of (A) 3TOP-TOP1 (alpha-cadinol), (B) 3TOP-TOP2 (cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran), and (C) 3TOP-STD (Acarbose) with the MGAM target protein. Key residues involved in the binding include aromatic and hydrophobic interactions with residues such as TRP A: 1355, HIS A: 1710, and ASP A: 1157, and hydrogen bonds critical for stabilization. The ligands TOP1 and TOP2 exhibited stronger binding affinities compared to the standard drug, making them promising candidates for further studies

ADME prediction

Both compounds exhibit molecular weights that are well within the favorable range for drug-like molecules. This ensures their compatibility with oral drug delivery, as lower molecular weights generally enhance membrane permeability and systemic absorption. Importantly, both compounds satisfy the Lipinski rule of five, passing all criteria related to hydrogen bond donors, hydrogen bond acceptors, molecular weight, and lipophilicity. Rotatable bonds and structural flexibility are also crucial considerations in drug design. The alpha-cadinol, with 16 rotatable bonds, is more structurally flexible than cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran, which has only 4 rotatable bonds. This reduced flexibility in cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran may contribute to improved binding affinity and specificity, as excessive molecular flexibility can sometimes lead to reduced target engagement. However, alpha-cadinol’s higher flexibility might confer advantages in interacting with a broader range of targets. Both compounds are classified as soluble based on their Log S values, indicating favorable solubility in aqueous environments, a key property for effective drug absorption. Their high gastrointestinal (GI) absorption further supports their potential for oral administration, suggesting that they can efficiently permeate the intestinal barrier and enter systemic circulation (table 2).

The cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran is a P-gp substrate, meaning it may be susceptible to efflux by cellular transporters, potentially reducing its intracellular concentrations. Alpha-cadinol, in contrast, is not a P-gp substrate, which could result in better retention within target cells and improved therapeutic efficacy. Both compounds pass multiple drug-likeness filters, including Ghose, Veber, and Egan screening, reinforcing their suitability as orally bioavailable drug candidates. Their bioavailability scores, at 0.55, reflect a reasonable potential for systemic exposure upon oral administration, although this could be further optimized through structural modifications. Neither compound raised Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) alerts, indicating a low likelihood of non-specific interactions that could interfere with assay results. However, alpha-cadinol triggered one Brenk alert, which signals a potential liability requiring attention during further development. The cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran had no Brenk alerts, suggesting a cleaner pharmacophoric profile (table 2).

Table 2: ADMET profile and drug-likeness evaluation of top compound

| Properties | Alpha-cadinol | Cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran |

| Molecular weight | 222.37 g/mol | 328.45 g/mol |

| Rotatable bonds | 16 | 4 |

| H-bond donors | 1 | 0 |

| H-bond acceptors | 1 | 1 |

| TPSA | 20.23 Ų | 9.23 Ų |

| Solubility (Log S) | Soluble | Soluble |

| iLOGP | 3.15 | 3.75 |

| Gastrointestinal Absorption | High | High |

| Blood-brain barrier permeation | Yes | No |

| Caco-2 Permeability | -4.825 | -4.837 |

| P-gp substrate | No | Yes |

| Lipinski screening | Yes | Yes |

| Ghose screening | Yes | Yes |

| Veber screening | Yes | Yes |

| Egan screening | Yes | Yes |

| Bioavailability | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| PAINS alerts | No alerts | No alerts |

| Brenk alerts | One alert | No alerts |

| Synthetic accessibility | 4.29 | 3.52 |

Toxicity profiling

The toxicity class screening criteria classify substances based on LD50 values:

Class I (LD50 ≤ 5 mg/kg): Fatal if swallowed.

Class II (5<LD50 ≤ 50 mg/kg): Fatal if swallowed.

Class III (50<LD50 ≤ 300 mg/kg): Toxic if swallowed.

Class IV (300<LD50 ≤ 2000 mg/kg): Harmful if swallowed.

Class V (2000<LD50 ≤ 5000 mg/kg): May be harmful if swallowed.

Class VI (LD50>5000 mg/kg): Non-toxic.

The toxicity profiles of alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran reveal distinct safety characteristics that influence their potential therapeutic applications. Both compounds demonstrate an absence of hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, and cytotoxicity, indicating minimal risk for systemic organ damage. However, specific toxicity alerts differentiate their safety profiles: alpha-cadinol shows a potential for respiratory toxicity, which could necessitate careful consideration of delivery routes and formulations to avoid adverse respiratory effects. While cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran presents neurotoxicity and warrants detailed evaluations of its effects on the nervous system, particularly during prolonged use (table 3).

Molecular dynamics simulation

The all-atom MD simulation is a suitable method for examining the structural dynamics of proteins and their interactions with ligands. This technique has revolutionized the field of computer-aided drug design and discovery, as it allows for a detailed analysis of molecular systems at the atomic level. In this study, MD simulations were performed to investigate the dynamic changes that occur upon binding of the target protein. Several parameters, such as RMSD, RMSF, Rg, SASA, and inter-and intra-hydrogen bonding, were calculated for both the protein and protein-ligand complex.

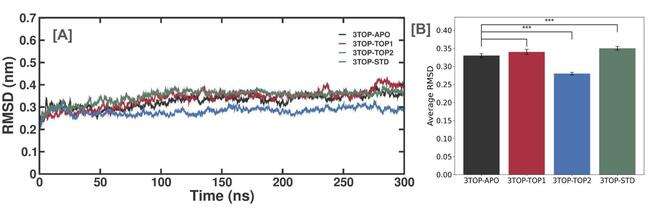

a. RMSD analysis

The RMSD analysis was performed to evaluate the stability of the protein-ligand complexes over the 300 ns molecular dynamics simulation. This analysis provides a quantitative measure of the deviation of the protein’s backbone atoms over time, offering insights into how stable the systems remained when bound to different ligands. The RMSD plots (fig. 3) show that all complexes, including the 3TOP-APO (unbound), 3TOP-TOP1, 3TOP-TOP2, and 3TOP-STD (standard reference), reached equilibrium within the first 10 ns, indicating initial stability across the board.

The RMSD trajectories suggest that 3TOP-APO maintained an average RMSD of 0.35±0.03 nm, showing consistent stability throughout the simulation period. The 3TOP-TOP1 and 3TOP-TOP2 complexes displayed average RMSD values of 0.33±0.03 nm and 0.34±0.04 nm, respectively, while the standard 3TOP-STD complex showed an average RMSD of 0.28±0.02 nm. These values indicate that all protein-ligand complexes remained within an acceptable range of structural deviation, implying stable binding interactions and minimal structural perturbations during the simulation. The slightly lower RMSD observed for the standard 3TOP-STD complex compared to the novel ligands suggests that Acarbose formed a slightly more stable interaction with the MGAM subunit. The RMSD values for 3TOP-TOP1 and 3TOP-TOP2 were close to that of the standard, indicating that these novel ligands exhibited comparable stability, which is a positive indication of their potential as effective inhibitors.

Table 3: Predicted toxicity profiles and organ toxicity of the top compounds

| Properties | Alpha-cadinol | Cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran |

| Predicted LD50 | 2830 mg/kg | 250 mg/kg |

| Predicted Toxicity | Class 5 | Class 3 |

| Hepatoxicity | Inactive | Inactive |

| Neurotoxicity | Inactive | Active |

| Nephrotoxicity | Inactive | Inactive |

| Cardiotoxicity | Inactive | Inactive |

| Carcinogenicity | Inactive | Inactive |

| Mutagenicity | Inactive | Inactive |

| Cytotoxicity | Inactive | Inactive |

| Respiratory Toxicity | Active | Inactive |

Fig. 3: RMSD trajectory analysis of MGAM and its complexes with novel ligands and standard drug during a 300 ns simulation, (A) RMSD trajectories of the unbound protein (3TOP-APO), alpha-cadinol (3TOP-TOP1), cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran (3TOP-TOP2), and Acarbose (3TOP-STD) complexes over 300 ns. All systems reached equilibrium within 10 ns, indicating stability. (B) Average RMSD values for the respective systems, showing that 3TOP-TOP1 and 3TOP-TOP2 exhibited similar stability to the standard drug (3TOP-STD), while the unbound protein (3TOP-APO) had slightly higher deviation. Statistical significance is indicated (p<0.001) between groups, indicating the stability differences

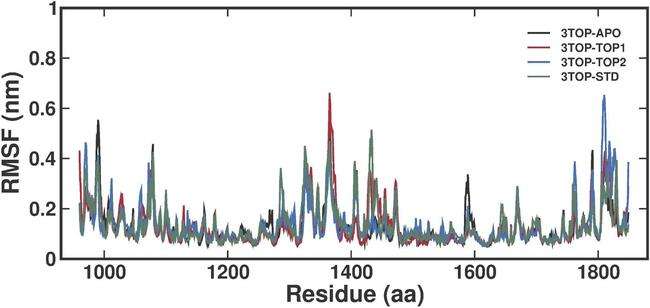

b. RMSF analysis

The RMSF analysis evaluates the flexibility of individual amino acid residues in the MGAM protein across its unbound and ligand-bound states. This analysis provides insights into the local dynamics of the protein structure, highlighting regions of high or low flexibility that are critical for ligand binding and protein function. The RMSF analysis revealed distinct patterns of residue flexibility for the unbound MGAM protein (3TOP-APO) and its ligand-bound complexes (3TOP-TOP1, 3TOP-TOP2, and 3TOP-STD). The unbound protein exhibited higher fluctuations, particularly around residues ~1400 and ~1800, likely corresponding to flexible loop regions or solvent-exposed segments, reflecting the inherent flexibility of the structure in the absence of ligand stabilisation. These fluctuations suggest a dynamic role for these regions in substrate access and accommodation. Upon binding with alpha-cadinol (3TOP-TOP1), the RMSF values for these regions decreased significantly, indicating that the ligand interacts with critical residues near 1400 and 1580, effectively stabilizing the binding site and reducing overall flexibility. This stabilization suggests that alpha-cadinol induces a more rigid conformation, potentially enhancing inhibitory activity. Similarly, cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran (3TOP-TOP2) also reduced fluctuations around residues 1200–1400 and ~1800, though slightly higher flexibility was observed compared to 3TOP-TOP1, particularly in terminal loops. This may reflect a more dynamic binding mode, allowing the protein to adopt conformations conducive to inhibitor binding. Acarbose (3TOP-STD), the standard drug, demonstrated the lowest RMSF values, particularly near residues 1400 and 1800, emphasizing its strong interactions and minimal structural perturbations (fig. 4).

Comparatively, all ligand-bound systems exhibited reduced flexibility relative to the unbound state, with alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran demonstrating stabilizing effects similar to Acarbose. The slightly higher fluctuations in the 3TOP-TOP2 complex suggest a potential advantage in terms of binding dynamics, while the conserved low RMSF values in core regions across all systems highlight their structural importance for maintaining stability. These findings suggest that alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran stabilize MGAM effectively, reducing flexibility in critical regions essential for enzymatic activity, which is indicative of strong ligand binding and potential therapeutic efficacy (fig. 4).

c. Rg analysis

The Rg analysis provides a measure of the compactness of the MGAM protein’s structure over the 300 ns MD simulation, offering insights into ligand-induced conformational changes. The unbound protein (3TOP-APO) displayed the highest average Rg value of 3.02±0.04 nm, reflecting an expanded conformation associated with greater flexibility and solvent accessibility. This dynamic behavior is characteristic of the protein in its unbound state, facilitating substrate binding and release. In contrast, the alpha-cadinol-bound complex (3TOP-TOP1) exhibited a reduced average Rg value of 2.95±0.03 nm, indicating that the ligand induces a more compact conformation, stabilizing the active site and constraining structural flexibility. A similar trend was observed for cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran (3TOP-TOP2), which showed an average Rg value of 2.96±0.03 nm, slightly higher than 3TOP-TOP1, suggesting marginally greater flexibility that could be attributed to differences in binding dynamics or interaction profiles. The standard drug Acarbose (3TOP-STD) exhibited the lowest Rg value of 2.91±0.02 nm, demonstrating the most compact conformation and underscoring its strong stabilizing effect on MGAM, consistent with its known efficacy as an enzyme inhibitor. The reduction in Rg across all ligand-bound systems compared to the unbound protein highlights the stabilizing effect of ligand binding, with alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran inducing conformations comparable to that of Acarbose (fig. 5a and 5b). These reductions suggest that the ligands not only promote structural compactness but also minimize conformational fluctuations, ensuring stable binding interactions.

Fig. 4: RMSF analysis of MGAM residues in unbound and ligand-bound states over a 300 ns MD simulation, The RMSF plot compares residue-level fluctuations for the unbound protein (3TOP-APO), alpha-cadinol (3TOP-TOP1), cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran (3TOP-TOP2), and Acarbose (3TOP-STD). Peaks in flexibility are observed near residues 1400 and 1800, corresponding to loop regions and solvent-exposed areas. Ligand-bound systems exhibit reduced fluctuations compared to the unbound protein, with Acarbose (3TOP-STD) showing the lowest fluctuations, followed closely by 3TOP-TOP1 and 3TOP-TOP2

Fig. 5: Rg and SASA analyses of the MGAM protein and its complexes during a 300 ns molecular dynamics simulation, (A) Rg trajectories showing the compactness of the unbound protein (3TOP-APO) and ligand-bound systems (3TOP-TOP1, 3TOP-TOP2, 3TOP-STD). Ligand binding reduces structural expansion compared to the unbound state. (B) Average Rg values indicate the unbound protein has the highest Rg (3.02±0.04 nm), while Acarbose (3TOP-STD) achieves the most compact structure (2.91±0.02 nm). (C) SASA trajectories display the solvent-exposed surface area, with ligand binding reducing solvent accessibility. (D) Average SASA values show significant reductions upon ligand binding, with Acarbose having the lowest SASA (339.1±4.3 nm²). Statistical differences highlight the stabilizing effects of ligands on MGAM structure (p<0.001 for Rg, p<0.01 for SASA)

d. SASA analysis

The SASA analysis evaluates the extent of the MGAM protein's surface exposed to solvent molecules over a 300 ns MD simulation, offering valuable insights into ligand-induced conformational changes. The unbound MGAM protein (3TOP-APO) displayed the highest average SASA value of 362.7±5.3 nm², indicative of a flexible, expanded structure with increased solvent exposure, consistent with its dynamic behavior in the absence of ligand stabilization. Binding of alpha-cadinol (3TOP-TOP1) reduced the average SASA to 345.3±4.7 nm², reflecting a more compact conformation and decreased solvent exposure, particularly in the active-site regions, highlighting the stabilizing effects of ligand binding. Similarly, the 3TOP-TOP2 complex (cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran) exhibited a slightly lower SASA of 341.8±5.1 nm², suggesting an even tighter protein conformation, potentially due to stronger interactions that restrict residue flexibility and solvent accessibility. The standard drug Acarbose (3TOP-STD) demonstrated the lowest SASA of 339.1±4.3 nm², representing the most compact and stable protein-ligand conformation, consistent with its established efficacy as an MGAM inhibitor. These results collectively reveal that ligand binding significantly reduces SASA compared to the unbound state, with alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran achieving compactness comparable to Acarbose. The slightly higher SASA for 3TOP-TOP1 compared to 3TOP-TOP2 indicates subtle differences in binding-induced dynamics, with cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran inducing a tighter interaction profile (fig. 5c and 5d). The highest SASA in the unbound protein underscores its inherent flexibility and solvent exposure, further emphasizing the stabilizing role of ligand binding. These reductions in SASA validate the ability of the novel ligands to shield the protein’s active site, minimize structural fluctuations, and promote inhibitory activity, supporting their potential as promising therapeutic candidates for diabetes management.

Interestingly, while trajectory-based SASA calculations indicate that acarbose induces the most compact protein conformation with the lowest average surface exposure (339.1±4.3 nm²), the solvation energy component in the MM-PBSA analysis appears comparatively high. This observation is not contradictory but rather reflects the physicochemical profile of acarbose itself. As a pseudo-tetrasaccharide with multiple hydroxyl groups and polar moieties, acarbose possesses a high solvation energy due to extensive hydrogen bonding potential with solvent molecules. The energy penalty incurred during desolvation is, therefore, greater than that observed for more hydrophobic ligands such as alpha-cadinol and cis-4-benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran. However, this desolvation cost is effectively counterbalanced by highly favorable electrostatic and van der Waals interactions within the MGAM binding site, resulting in a net binding energy that remains consistent with its well-established inhibitory potency. This interplay is characteristic of hydrophilic drugs: although they exhibit higher solvation penalties, they often achieve deep binding through strong polar contacts, particularly in enzyme targets with hydrophilic active sites like MGAM. The low SASA values observed during simulation indicate that once acarbose is bound, it promotes a stable and conformationally restricted protein structure. These findings underscore that solvation energy should not be interpreted in isolation but as part of the complete thermodynamic profile of ligand binding. When trajectory-based structural metrics (SASA, Rg) and energetic components (MM-PBSA) are interpreted together, they reaffirm the superior stabilizing effect of acarbose and validate the computational pipeline used in this study.

e. Inter-hydrogen bond analysis

Inter-Hydrogen bond (H-bond) analysis assesses the number and stability of H-bonds formed between MGAM and its ligands over the 300 ns MD simulation, providing insights into their role in stabilizing protein-ligand interactions and influencing inhibitory efficacy. The 3TOP-TOP1 complex (alpha-cadinol) formed the fewest H-bonds, averaging approximately 1 bond per frame with intermittent durations of bond absence, suggesting transient and less stable interactions. This indicates a binding mechanism reliant more on hydrophobic and van der Waals forces rather than polar interactions. The 3TOP-TOP2 complex (cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran) exhibited a slightly higher average of up to 2 H-bonds, with moderate stability and transient interactions, reflecting a stronger reliance on hydrogen bonding compared to 3TOP-TOP1, but still dependent on other non-polar forces like π-π stacking for stabilization. In contrast, the standard drug Acarbose (3TOP-STD) displayed the highest and most consistent H-bonding, averaging 10–15 H-bonds throughout the simulation, underscoring its strong and stable interaction with MGAM and aligning with its role as a potent enzyme inhibitor. This abundance of persistent H-bonds contributes significantly to the compact and rigid conformations observed in Rg and SASA analyses. Comparatively, Acarbose’s superior H-bond profile highlights its optimized binding efficiency, while the novel ligands, though forming fewer H-bonds, demonstrate the potential for structural stabilization and compactness. These findings suggest that alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran could benefit from optimization to improve their polar interaction profiles, enhancing their inhibitory potential (fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Time-resolved inter-hydrogen bond analysis for MGAM-ligand complexes during a 300 ns molecular dynamics simulation, the number of hydrogen bonds formed between MGAM and the ligands (3TOP-TOP1, 3TOP-TOP2, 3TOP-STD) is shown over the simulation time. 3TOP-TOP1 (alpha-cadinol) exhibited transient H-bonding, averaging ~1 H-bond per time frame, while 3TOP-TOP2 (cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran) demonstrated moderate stability with up to 2 H-bonds forming intermittently. Acarbose (3TOP-STD) displayed the highest and most consistent H-bond count (10–15 bonds), indicating strong and stable interactions.

f. Intra-hydrogen bond analysis

Intra-hydrogen bond (H-bond) analysis evaluates the stability and internal structural integrity of the MGAM protein during the MD simulation. These intra-protein hydrogen bonds contribute significantly to maintaining the protein's tertiary structure, ensuring functional stability and flexibility required for enzymatic activity. The unbound MGAM protein displayed an average intra-H-bond count of approximately 670–680 bonds, with a slight upward trend over the simulation period. This result suggests that even in the absence of ligand stabilization, MGAM maintains substantial internal structural integrity, relying on its intrinsic hydrogen bonding network. The gradual increase in H-bonds may indicate compensatory internal stabilization as the protein adjusts to the solvent environment during the simulation. The 3TOP-TOP1 complex demonstrated a slightly higher average intra-H-bond count of approximately 680–690 bonds, reflecting enhanced structural stability compared to the unbound state. This increase in intra-H-bonds suggests that alpha-cadinol binding induces conformational changes that stabilize internal hydrogen bonding networks, likely through interactions that reinforce key secondary and tertiary structural elements. The profile shows a consistent trend with minimal fluctuations, indicating stable structural integrity throughout the simulation. The 3TOP-TOP2 complex exhibited an intra-H-bond count in the range of 685–695 bonds, slightly higher than that of 3TOP-TOP1. This result suggests that cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran induces more significant structural stabilization compared to alpha-cadinol. The higher intra-H-bond count may be attributed to stronger or more extensive interactions between the ligand and protein residues, promoting a tighter and more stable internal hydrogen bond network. The Acarbose complex (3TOP-STD) showed the highest average intra-H-bond count, approximately 690–700 bonds, indicating the strongest internal stabilization among all systems. This result is consistent with Acarbose's known efficacy as a potent inhibitor, which stabilizes the protein structure through optimized interactions.

The high and consistent H-bond count throughout the simulation underscores the compact and rigid structural conformation induced by Acarbose binding (fig. 7). The ligand binding enhances the internal hydrogen bonding network of MGAM, with all ligand-bound systems displaying higher H-bond counts compared to the unbound protein. Among the ligands, Acarbose exhibited the most pronounced stabilization, followed closely by cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran and alpha-cadinol.

Fig. 7: Time-resolved intra-hydrogen bond analysis for MGAM-ligand complexes during a 300 ns molecular dynamics simulation, the graph illustrates the number of intra-hydrogen bonds formed within MGAM in its unbound (3TOP-APO) and ligand-bound states (3TOP-TOP1, 3TOP-TOP2, 3TOP-STD) over the simulation. The unbound protein displayed a relatively lower average H-bond count (~670–680), indicating a less stabilized internal structure. Ligand binding enhanced the intra-H-bond network, with 3TOP-TOP1 (alpha-cadinol) averaging ~680–690 bonds, 3TOP-TOP2 (cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran) showing ~685–695 bonds, and 3TOP-STD (Acarbose) exhibiting the highest count (~690–700), highlighting its superior stabilizing effect

g. PCA analysis

In the PCA analysis, the trajectories are projected onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2), and the PCA captures the dominant motions and highlights the structural diversity of each system. The PCA plot for the unbound protein (3TOP-APO) shows a broader conformational space, indicating higher flexibility and structural diversity. The spread along both PC1 and PC2 reflects the absence of ligand-induced stabilization, allowing the protein to sample a wide range of conformations. This variability is characteristic of unbound states, where the protein retains flexibility to accommodate potential ligand binding. The 3TOP-TOP1 complex demonstrates a more confined conformational space compared to the unbound protein. The PCA plot reveals a relatively restricted motion, indicative of ligand-induced stabilization. Alpha-cadinol binding likely reduces structural flexibility, constraining the protein to a subset of stable conformations. The PCA plot for the 3TOP-TOP2 complex shows further reduction in conformational sampling compared to 3TOP-TOP1. The compact motion along PC1 and PC2 indicates that cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran induces a tighter and more stable binding conformation. This reduced flexibility may be attributed to stronger interactions between the ligand and MGAM, which restrict the protein's ability to explore alternative conformations. The PCA plot for the Acarbose complex (3TOP-STD) exhibits the most confined conformational space among all systems. This observation highlights the strong stabilizing effect of Acarbose, which effectively locks the protein into a narrow range of stable conformations. The ligand-bound systems exhibit progressively restricted motions, with Acarbose (3TOP-STD) showing the most confinement (fig. 8). Among the novel ligands, cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran (3TOP-TOP2) induces greater restriction compared to alpha-cadinol (3TOP-TOP1), indicating its stronger stabilizing effect. This reduction in conformational space is critical for effective inhibition, as it reflects the ability of ligands to stabilize the protein in inhibitor-bound states, preventing unnecessary flexibility that could disrupt binding.

h. FEL analysis

The FEL visualizes stable conformations as low-energy basins by mapping the conformational states based on their free energy levels, which indicate energetically favorable structural states. The FEL plots compare the stability of unbound MGAM (3TOP-APO) and its ligand-bound complexes. The FEL for the unbound protein (fig. 9A) displays multiple shallow basins distributed across a wide area, reflecting the high conformational flexibility and dynamic nature of MGAM in its unbound state. The broader distribution of low-energy states indicates that the protein samples numerous conformations, consistent with the lack of ligand-induced stabilization. This flexibility allows the protein to dynamically adapt to substrate binding but also suggests lower structural stability. The FEL for the 3TOP-TOP1 complex (fig. 9B) shows a more defined and deeper low-energy basin compared to the unbound state, suggesting improved structural stability upon ligand binding. The presence of fewer basins and a more concentrated low-energy region highlights the stabilization effect of alpha-cadinol. The FEL for the 3TOP-TOP2 complex (fig. 9C) exhibits an even deeper and more centralized low-energy basin compared to 3TOP-TOP1. This indicates stronger structural stabilization by cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran. The tighter energy distribution reflects the ligand's ability to constrain the protein in a highly stable conformation, reducing unnecessary flexibility while maintaining key dynamic properties essential for ligand binding and inhibition. The FEL for the Acarbose complex (fig. 9D) features the deepest and most confined low-energy basin among all systems. This demonstrates that Acarbose induces the highest degree of structural stabilization, locking MGAM into a single, energetically favorable conformation. The ligand binding reduces the conformational diversity of MGAM by stabilizing the protein in fewer low-energy states. The unbound protein exhibits a broad distribution of shallow basins, reflecting high flexibility and lower stability. In contrast, ligand-bound systems progressively show more defined and deeper basins, with Acarbose inducing the most stable conformation. Among the novel ligands, cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran demonstrates superior stabilization compared to alpha-cadinol, as evidenced by the depth and concentration of its low-energy basin.

Fig. 8: PCA analysis of MGAM protein and its complexes over a 300 ns molecular dynamics simulation, PCA projections onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) reveal the conformational space sampled by unbound MGAM (3TOP-APO) and ligand-bound systems (3TOP-TOP1, 3TOP-TO9P2, and 3TOP-STD). The unbound protein shows a broad conformational space, reflecting high flexibility, while ligand binding reduces conformational diversity. Acarbose (3TOP-STD) exhibits the most confined conformational space, highlighting its strong stabilizing effect. Among the novel ligands, cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran (3TOP-TOP2) shows tighter confinement compared to alpha-cadinol (3TOP-TOP1), indicating a stronger stabilizing interaction.

Fig. 9: FEL analysis of MGAM protein and its complexes during a 300 ns molecular dynamics simulation, FEL plots for (A) unbound MGAM (3TOP-APO), (B) alpha-cadinol-bound MGAM (3TOP-TOP1), (C) cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran-bound MGAM (3TOP-TOP2), and (D) Acarbose-bound MGAM (3TOP-STD) display the energy landscapes sampled during the simulation. The unbound protein exhibits broad and shallow basins, indicating high conformational flexibility, while ligand-bound systems show progressively deeper and more confined basins, reflecting enhanced structural stability

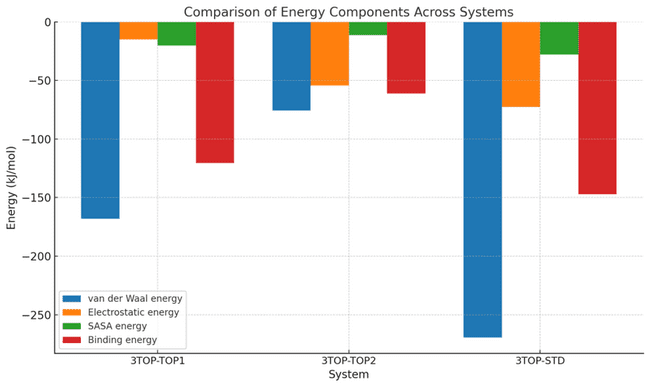

i. Binding free energy calculation

The binding free energy calculations provide a detailed breakdown of the interactions between the MGAM protein and its ligands, highlighting the key contributions of van der Waals energy, electrostatic energy, SASA energy, and the total binding energy. For 3TOP-TOP1 (alpha-cadinol), the binding energy is moderate at-20.332±1.088 kJ/mol, driven primarily by van der Waals interactions (-168.194±7.325 kJ/mol) that dominate the stabilisation. The electrostatic contribution is minimal (-14.922±4.614 kJ/mol), indicating weak polar interactions, while the SASA energy (83.080±11.020 kJ/mol) reflects substantial solvent exposure, reducing overall binding efficiency. These data suggest that alpha-cadinol’s stabilisation relies heavily on hydrophobic interactions, leaving room for improvement in polar interactions and reducing solvent accessibility.

While the 3TOP-TOP2 (cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran), the binding energy improves significantly to-61.020±7.594 kJ/mol, supported by a balance of van der Waals (-75.723±11.445 kJ/mol) and electrostatic interactions (-54.428±9.046 kJ/mol). The stronger electrostatic energy highlights the role of hydrogen bonding or ionic interactions in stabilising the complex. The SASA energy (80.560±5.143 kJ/mol) is slightly lower than for alpha-cadinol, suggesting reduced solvent exposure and a more compact conformation. This combination of stronger polar interactions and better solvent shielding results in a more stable binding interaction compared to 3TOP-TOP1. The binding energy for 3TOP-STD (Acarbose) is the strongest among all systems, measured at-147.218±11.759 kJ/mol, demonstrating its superior inhibitory efficiency. This is largely driven by substantial van der Waals contributions (-269.456±21.566 kJ/mol) and the highest electrostatic energy (-72.673±19.623 kJ/mol) observed across the systems, indicating robust hydrophobic and polar interactions. Despite the high SASA energy (222.660±28.917 kJ/mol), which suggests significant solvent exposure, Acarbose achieves remarkable stabilisation due to its optimised binding profile. The large negative binding energy reflects its ability to induce a highly stable and energetically favourable conformation in MGAM. Acarbose exhibits the strongest overall stabilisation, leveraging synergistic hydrophobic and polar interactions, despite higher solvent exposure. Cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran achieves a balanced interaction profile, with moderate van der Waals and strong electrostatic contributions, resulting in a stable and compact binding state. In contrast, alpha-cadinol demonstrates weaker binding, driven predominantly by van der Waals interactions and limited by poor electrostatic interactions and higher solvent exposure. These results suggest that optimising polar interactions and minimising solvent exposure for alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran could further enhance their binding efficacy, making them promising candidates for MGAM inhibition.

Table 4: Binding energy components for MGAM ligand complexes

| System | Van der waal energy | Electrostatic energy | SASA energy | Binding energy |

| 3TOP-TOP1 | -168.194+/-7.325 kJ/mol | -14.922+/-4.614 kJ/mol | 83.080+/-11.020 kJ/mol | -20.332+/-1.088 kJ/mol |

| 3TOP-TOP2 | -75.723+/-11.445 kJ/mol | -54.428+/-9.046 kJ/mol | 80.560+/-5.143 kJ/mol | -61.020+/-7.594 kJ/mol |

| 3TOP-STD | -269.456+/-21.566 kJ/mol | -72.673+/-19.623 kJ/mol | 222.660+/-28.917 kJ/mol | -147.218+/-11.759 kJ/mol |

Fig. 10: Comparison of energy components contributing to the binding free energy of MGAM protein complexes during molecular dynamics simulations, The graph depicts energy contributions to the total binding free energy for 3TOP-TOP1 (alpha-cadinol), 3TOP-TOP2 (cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran), and 3TOP-STD (Acarbose). Van der Waals energy dominates the stabilizing forces across all systems, with Acarbose exhibiting the strongest contribution. Electrostatic energy is notably higher in 3TOP-STD and 3TOP-TOP2, highlighting their robust polar interactions. SASA energy, indicative of solvent exposure, is highest for Acarbose, yet it achieves the lowest binding energy due to its optimized interaction network. Statistical variations are shown to emphasize the relative strengths and weaknesses of the ligands

DISCUSSION

MGAM is a membrane-bound enzyme that plays a pivotal role in human carbohydrate metabolism. It is a part of the α-glucosidase family and is highly expressed in the brush border membrane of intestinal epithelial cells, where it contributes to the terminal steps of starch digestion. MGAM hydrolyzes maltose, maltotriose, and other oligosaccharides derived from dietary starches and glycogen, cleaving their α-1,4-glycosidic bonds to produce glucose [26]. This enzymatic activity is essential for energy homeostasis, as glucose serves as the primary energy substrate for most cellular processes. Structurally, MGAM is composed of two homologous catalytic subunits, the N-terminal and C-terminal domains, each of which can independently hydrolyze oligosaccharides. These domains exhibit overlapping substrate specificities but vary in their catalytic efficiencies, enabling MGAM to efficiently process a broad range of dietary carbohydrates. This dual-domain configuration and substrate versatility make MGAM an indispensable enzyme in carbohydrate digestion [27].

In diabetes pathogenesis, MGAM assumes a critical role due to its influence on postprandial glucose levels. T2DM, characterised by chronic hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, is closely linked to aberrant glucose metabolism. MGAM’s enzymatic activity directly impacts the rate at which glucose is released into the bloodstream following the ingestion of carbohydrate-rich meals. Dysregulated or excessive MGAM activity exacerbates postprandial hyperglycemia, a hallmark of T2DM, by rapidly converting dietary oligosaccharides into glucose, overwhelming the impaired insulin response typical of diabetic individuals [26, 29]. This uncontrolled glucose influx not only contributes to the development of insulin resistance but also induces oxidative stress and inflammation, further aggravating the metabolic dysregulation in diabetes. Moreover, sustained postprandial hyperglycemia has been implicated in microvascular and macrovascular complications such as nephropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular disease, underscoring the pathological significance of MGAM in diabetes [27]. MGAM’s role in diabetes pathogenesis is not limited to its enzymatic activity. Emerging evidence suggests that MGAM may influence gut microbiota composition and function, indirectly affecting glucose metabolism. The hydrolysis of oligosaccharides by MGAM releases glucose that can be absorbed by enterocytes or utilized by gut microbes [26,]. Alterations in MGAM activity may shift the microbial ecosystem, leading to dysbiosis, which has been linked to metabolic disorders including diabetes. The enzyme’s activity also modulates the release of glucose into the gut lumen, influencing incretin hormone secretion such as glucagon-like peptide-1, which plays a vital role in insulin secretion and glycemic control [29]. These multifaceted interactions between MGAM activity, glucose metabolism, and gut microbiota highlight its central role in the metabolic network that governs diabetes pathophysiology.

Given its significant contributions to glucose homeostasis and its pathological implications in diabetes, MGAM is an attractive therapeutic target. The inhibition of MGAM has been shown to effectively reduce postprandial glucose excursions, making it a viable strategy for managing hyperglycemia [10]. MGAM inhibitors achieve this by binding to the enzyme’s active site, competitively inhibiting substrate hydrolysis, and thereby delaying glucose absorption. This reduction in glucose influx not only improves glycemic control but also alleviates the burden on pancreatic β-cells, potentially slowing the progression of diabetes [30]. MGAM inhibition may positively influence gut microbiota by reducing the availability of simple sugars that fuel pathogenic bacteria, thereby promoting a healthier microbial balance. These multifaceted benefits underscore the therapeutic potential of MGAM as a target for diabetes management [26].

Inhibitors of MGAM, such as acarbose [9], miglitol [10], and voglibose [31], have been widely studied and used clinically. These drugs act by mimicking the natural substrates of MGAM, binding to the enzyme with high affinity, and preventing the hydrolysis of oligosaccharides. Acarbose, a complex oligosaccharide derived from microbial fermentation, is one of the most well-known alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. It inhibits MGAM by occupying its active site, forming transient complexes with catalytic residues, and blocking substrate access. This competitive inhibition reduces the enzymatic breakdown of carbohydrates, leading to delayed glucose absorption and a flattening of postprandial glucose peaks [10, 31]. Miglitol and voglibose employ similar mechanisms of action but differ in their molecular structures and pharmacokinetics, offering alternative options for patients with varying therapeutic needs. However, these drugs are not without limitations. Their primary site of action is the gastrointestinal tract, where undigested carbohydrates ferment and produce gas, leading to side effects such as bloating and diarrhea. These adverse effects often limit their widespread use, despite their efficacy in reducing postprandial hyperglycemia [10, 31].

Acarbose, in particular, has been extensively studied as a standard for MGAM inhibition. As a competitive inhibitor, acarbose binds to the active site of MGAM with high specificity, blocking the hydrolysis of oligosaccharides and delaying glucose release [9, 32]. Its multiple hydroxyl groups enable strong hydrogen bonding with catalytic residues, enhancing its inhibitory potency. Acarbose’s low systemic absorption ensures that its action remains localized to the intestinal lumen, minimizing systemic side effects [33]. However, this low absorption also limits its potential for broader systemic benefits. Despite these limitations, acarbose has been shown to improve glycemic control, reduce glycemic variability, and lower the risk of cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients. Its well-characterized mechanism of action and established efficacy make it a valuable comparator for evaluating new MGAM inhibitors [34].

In this study, molecular docking was used to evaluate 18 phytocompounds from the methanolic extract of Cinnamomum zeylanicum against MGAM, focusing on their ability to bind and inhibit the enzyme. Docking simulations identified alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran as the top candidates based on their binding affinities, which were higher than that of acarbose. Visualisations of docking interactions revealed distinct binding profiles. Alpha-cadinol formed key interactions with residues such as TYR A: 1251 and GLY A: 1588, while cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran interacted with residues like HIS A: 1710 and THR A: 1699. Acarbose, as expected, showed strong interactions with residues common to the active site, including THR A: 1586 and ARG A: 1510. The presence of common interacting residues among these ligands supports their ability to effectively modulate MGAM activity. Both alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran exhibit features that position them as strong candidates for MGAM modulation. The hydroxyl groups in alpha-cadinol allow it to form hydrogen bonds with key active site residues, stabilizing its interaction with MGAM. Similarly, cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran’s aromatic rings facilitate π-π stacking interactions, enhancing binding affinity and specificity. Acarbose also relies on hydroxyl group interactions, creating a shared basis for comparison among these compounds. The structural diversity and binding profiles of the top compounds suggest that they may inhibit MGAM through complementary mechanisms. This dual potential for competitive inhibition, coupled with favorable pharmacokinetics observed in ADMET profiling, makes these ligands promising therapeutic candidates. Future studies may explore whether these ligands can provide sustained modulation of MGAM activity, potentially offering advantages over acarbose, particularly in terms of side effect profiles and systemic absorption.

The docking results strongly validate the hypothesis that both alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran can effectively bind to the MGAM active site. Alpha-cadinol exhibited the highest docking score, with residues such as TYR A: 1251 and GLY A: 1588 playing critical roles in its interaction, similar to acarbose. Cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran, with a slightly lower docking score, demonstrated interactions with HIS A: 1710 and ASP A: 1684, indicative of stable and specific binding. The comparable docking scores of these compounds to acarbose suggest their potential for comparable or superior inhibitory activity. The structural insights gained from docking visualizations further highlight their ability to interact with conserved residues essential for MGAM catalysis, supporting their candidacy for further development. The structural analysis of alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran reveals unique attributes that contribute to their inhibitory potential. Both compounds contain aromatic rings, facilitating π-π stacking interactions within the MGAM active site. This property is shared with acarbose, although the latter’s larger size and polysaccharide structure lead to a different binding profile. Alpha-cadinol’s hydroxyl group enhances solubility and hydrogen bonding, aligning it closely with acarbose’s binding strategy. Cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran’s balanced hydrophobic and aromatic interactions distinguish it from both alpha-cadinol and acarbose. The structural features of these compounds, coupled with their docking profiles, underscore their potential to reduce postprandial hyperglycemia by targeting MGAM. These findings align with the observed inhibitory activity of acarbose, providing a benchmark for evaluating the therapeutic potential of the phytocompounds. These compounds offer a broader therapeutic scope compared to acarbose, with the potential for enhanced binding efficiency and reduced side effects.

Although alpha-cadinol and cis-4-benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran exhibited favorable binding affinity and pharmacokinetic properties, toxicity predictions highlighted potential liabilities that must be addressed in early-phase lead optimization. Alpha-cadinol, a sesquiterpenoid alcohol with a compact hydrophobic backbone and a free hydroxyl group, was predicted to exhibit respiratory toxicity. This concern is pharmacologically plausible, as structurally similar volatile sesquiterpenes have been known to accumulate in lung tissue due to their high lipophilicity (logP>3.5) and low aqueous solubility, leading to irritation or delayed pulmonary clearance. A rational strategy to reduce this liability involves decreasing the compound’s lipophilicity by functionalizing the isopropyl side chain or hydroxyl moiety with polar substituents (e.g., sulfonates or glycosides), thereby improving aqueous solubility and systemic clearance. Additionally, esterification of the hydroxyl group may reduce bioactivation potential in pulmonary microsomes, which is a known route of metabolic toxicity for small terpenoids.

Cis-4-benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran (TOP2) raised neurotoxicity concerns, likely due to its rigid tri-aromatic framework. Highly planar, lipophilic compounds with molecular weights below 450 Da and TPSA<70 Ų are known to cross the BBB, where unintentional off-target effects on neurotransmitter transporters or ion channels can occur. To address this, one approach is to introduce polar functional groups (e. g., hydroxyl or carboxyl groups) on the benzyl ring to increase TPSA and reduce CNS penetration. Alternatively, replacing one of the phenyl rings with a saturated or heterocyclic bioisostere could retain binding affinity while minimizing neuroactive potential. Such rational modifications, guided by predictive ADME-tox tools, will not only mitigate off-target effects but also improve drug-like properties, paving the way for safer and clinically viable MGAM inhibitors.

While the computational findings strongly support the therapeutic promise of alpha-cadinol and cis-4-benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran as MGAM inhibitors, it is important to explicitly acknowledge the absence of experimental validation. To substantiate these in silico predictions, in vitro α-glucosidase inhibition assays are essential to confirm enzymatic binding and inhibitory efficacy. Furthermore, in vivo pharmacokinetic studies in appropriate animal models are necessary to evaluate absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and potential organ-specific toxicity, particularly respiratory and neurotoxic effects. These experimental approaches will provide critical translational evidence for the compounds’ safety and therapeutic potential, informing rational lead optimization and guiding future preclinical development.

CONCLUSION

The present study provides valuable insights into the inhibitory potential of alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran. Computational methods, though informative, cannot fully replicate the complexity of biological systems. Experimental validation through in vitro enzymatic assays and in vivo studies is essential to confirm the efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity profiles of the identified compounds. Additionally, the long-term effects of these phytocompounds on gut microbiota and metabolic pathways require investigation to ensure safety and efficacy in clinical applications. Despite these limitations, the study highlights the therapeutic potential of alpha-cadinol and cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran as novel MGAM inhibitors, offering a promising avenue for diabetes management. These findings underscore the value of integrating computational and experimental approaches to accelerate the discovery of effective, safe, and targeted therapeutics.

FUNDING

Nil

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ADMET-Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity, BBB-Blood-Brain Barrier, DM-Diabetes Mellitus, FEL-Free Energy Landscape, GI-Gastrointestinal, IDF-International Diabetes Federation, kcal/mol-Kilocalories per mole, LD50-Lethal Dose 50%, MD-Molecular Dynamics, MGAM-Maltase-Glucoamylase, MM-PBSA-Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area, PAINS-Pan-Assay Interference Compounds, PCA-Principal Component Analysis, PDB-Protein Data Bank, PDBsum-Protein Data Bank Summary, PPARγ-Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma, Rg-Radius of Gyration, RMSD-Root mean Square Deviation, RMSF-Root mean Square Fluctuation, SASA-Solvent Accessible Surface Area, SIRT6Sirtuin-6, SPCE-Simple Point Charge, STD-Standard Drug (Acarbose), T2DM-Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, TOP1-Alpha-cadinol (Top-performing ligand 1), TOP2-Cis-4-Benzyl-2,6-diphenyltetrahydropyran (Top-performing ligand 2), UFF-Universal Force Field.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

V. V. R., K. N. S., performed the research. D. S. M. designed the research study. A. K. contributed essential manuscript validations. V. V. R. and A. K. analysed the data and wrote the paper.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

Tomic D, Shaw JE, Magliano DJ. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18(9):525-39. doi: 10.1038/s41574-022-00690-7, PMID 35668219, PMCID 9169030.

GBD. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2023;402(10397):203-34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01301-6, PMID 37356446, PMCID PMC10364581.

Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:(109119). doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119. PMID 34879977, PMCID PMC11057359.

Bergman M, Tuomilehto J. International diabetes federation position statement on the 1 h post-load plasma glucose for the diagnosis of intermediate hyperglycaemia and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2024;210:(111636). doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2024.111636, PMID 38537890.

Das AK, Ghosh D, Ghosh J. Assessment of patients’ knowledge, attitude and practice regarding diabetes mellitus in a tertiary Care Hospital in eastern India. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2023;16(1):29-34. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2023.v16i1.46328.

Rajueni K, Ambekar R, Solanki H, Momin AA, Pawar S. Assessment of the possible causes of diabetes mellitus developed in patients post-COVID-19 treatment in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2021;13(9):11-5. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2021v13i9.42508.

Molecular docking simulation of mangostin derivatives and curcuminoid on maltase-glucoamylase target for searching anti-diabetes drug candidates. 1st International Conference on Biomedical Engineering (IBIOMED). IEEE; 2016.

Andayani N, Mulatsari E. Molecular structure similarity analysis using Tanimoto coefficient and its correlation analysis with Maltase-glucoamylase inhibitory activity of Nigella sativa’s compounds. J Nat Prod Degener Dis. 2024;2(1):48-57. doi: 10.58511/jnpdd.v2i1.7385.

Pyner A, Nyambe Silavwe H, Williamson G. Inhibition of human and rat sucrase and maltase activities to assess antiglycemic potential: optimization of the assay using acarbose and polyphenols. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65(39):8643-51. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b03678. PMID 28914528.

Prasetyanti IK, Sukardiman S, Suharjono S. ADMET prediction and in silico analysis of mangostin derivatives and sinensetin on maltase-glucoamylase target for searching anti-diabetes drug candidates. Pharmacogn J. 2021;13(4):883-9. doi: 10.5530/pj.2021.13.113.

Dinesh S, Sharma S, Chourasiya R. Therapeutic applications of plant and nutraceutical-based compounds for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A narrative review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2024;20(2):e050523216593. doi: 10.2174/1573399819666230505140206, PMID 37151065.

Beheshti AS, Qazvini MM, Abeq M, Abedi E, Fadaei MS, Fadaei MR. Molecular, cellular, and metabolic insights of cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) advantages in diabetes and related complications: condiment or medication? Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2025;398(4):3513-26. doi: 10.1007/s00210-024-03644-0, PMID 39589531.

Zare R, Nadjarzadeh A, Zarshenas MM, Shams M, Heydari M. Efficacy of cinnamon in patients with type II diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(2):549-56. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.03.003, PMID 29605574.

Elkhattabi L, Zouhdi S, Moussetad F, Kettani A, Barakat A, Saile R. Molecular docking analysis of PPARγ with phytochemicals from Moroccan medicinal plants. Bioinformation. 2023;19(7):795-806. doi: 10.6026/97320630019795, PMID 37901293, PMCID PMC10605085.

Singh P, Singh VK, Singh AK. Molecular docking analysis of candidate compounds derived from medicinal plants with type 2 diabetes mellitus targets. Bioinformation. 2019;15(3):179-88. doi: 10.6026/97320630015179, PMID 31354193, PMCID PMC6637395.

Vijh D, Gupta P. GC-MS analysis, molecular docking, and pharmacokinetic studies on Dalbergia sissoo barks extracts for compounds with anti-diabetic potential. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):24936. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-75570-3, PMID 39438536, PMCID PMC11496555.

Jayasurya, Swathy, Susha, Sharma S. Molecular docking and investigation of Boswellia serrata phytocompounds as cancer therapeutics to target growth factor receptors: an in silico approach. Int J App Pharm. 2023;15(4):173-83. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2023v15i4.47833.