Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 290-301Original Article

DEVELOPMENT AND CHARACTERIZATION OF GLYCYRRHIZIN-LOADED BUCCAL FILM-O-SPRAY: A NOVEL APPROACH TO RECURRENT APHTHOUS STOMATITIS THERAPY

AYESHA SYED*, PREETI KARWA, SOHAL MALLICK, PRITHIVIRAJAN S.

Al-Ameen College of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmaceutics, Rajiv Gandhi University of Health sciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Ayesha Syed; *Email: pharmayesha.syed@gmail.com

Received: 26 May 2025, Revised and Accepted: 26 Sep 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS), affecting 5–50% of the population, is characterized by painful oral ulcers. Conventional therapies often lead to side effects, drug resistance, and secondary infections, underscoring the need for safer and more effective alternatives. This study aimed to develop a glycyrrhizin-based film-forming spray (FFS_GLY) to enhance mucosal drug delivery, prolong retention, and provide rapid relief from oral ulcers.

Methods: A 3³ Box–behnken design was employed to optimize the concentrations of HPMC-E15, Eudragit-S100, and propylene glycol (PG), considering drying time and viscosity as dependent variables. The optimized formulation (F4) was evaluated for physicochemical properties, mucoadhesion, and mucosal drug retention. Each actuation of the spray was standardized to deliver 3 mg of glycyrrhizin. Preclinical efficacy was assessed in wistar rats with acetic acid–induced oral ulcers, supported by histopathological analysis.

Results: The optimized F4 formulation demonstrated a drying time of 75.12±0.05 seconds and viscosity of 19.28±0.019 cPs. It exhibited strong mucoadhesive strength (577.5±0.016 dynes/cm²; 0.05775 N/cm²) and sustained mucosal retention (6.105 mg/cm²) for up to 24 h. Consistent dose delivery was achieved with each spray actuation. In vivo studies showed significant reduction in ulcer diameter compared to controls, while histopathological evaluation confirmed enhanced epithelial regeneration and angiogenesis.

Conclusion: The developed FFS_GLY formulation demonstrated favourable physicochemical characteristics, excellent mucosal retention, and significant therapeutic efficacy in preclinical models. These findings establish FFS_GLY as a safe, effective, and promising alternative for the management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis.

Keywords: Recurrent aphthous stomatitis, Glycyrrhizin, Film-forming spray, Box-behnken design, Mucoadhesive system

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55216 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS), also known as oral ulcers or canker sores, is a common and painful condition affecting the oral cavity. It is identified by the formation of well-defined circular, painful lesions with erythematous borders and a greyish-yellow pseudomembranous base. The primary issue is pain, which can be exacerbated by consuming hot, salty, spicy, or hard/abrasive foods. Eating and drinking can therefore become difficult. Depending on the site of the ulcers, speech can also be affected. The ulcers occur in recurrent bouts, heal and reoccur at varying time intervals. Some individuals experience persistent ulcers and frequent recurrences of this condition [1]. The current treatment of RAS is aimed at ulcer re-epithelialization and reducing mucosal surface inflammation [2].

Currently available treatments for RAS include topical corticosteroids, antiseptic mouthwashes, analgesics and immunomodulatory agents. While these treatments provide symptomatic relief, they come with notable disadvantages. Corticosteroids, for instance, may cause mucosal thinning, delayed wound healing and an increased risk of secondary infections when used for extended periods [3]. Antiseptic mouthwashes can lead to altered taste sensation and oral irritation, limiting patient compliance [4]. Furthermore, many of these treatments rely on conventional dosage forms like ointments, gels, or mouthwashes, which suffer from poor retention at the lesion site, requiring frequent application and reducing efficacy [5].

Natural agents, known for their pharmacological properties, are widely utilized for their anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, analgesic, and immunomodulatory effects. Among these, liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) extract has garnered significant attention for its well-documented anti-ulcerative properties. It has been extensively used in the treatment of gastric and duodenal ulcers within the gastrointestinal tract and as an analgesic for managing spasmodic pain associated with chronic gastritis [6]. Recent investigations have shifted focus to the role of glycyrrhizin, a major active component of liquorice, in pain control and accelerating the healing of aphthous ulcers [7]. Studies indicate that liquorice extract modifies the progression of RAS by reducing lesion size, pain, and duration, thereby significantly expediting the healing process.

In contrast, liquorice extract offers a safer, more effective, and patient-friendly alternative. It eliminates the adverse effects associated with allopathic medications and, with its herbal origin, is suitable for long-term use without compromising safety or tolerability. This makes it a promising candidate for addressing the limitations of current RAS treatments while improving patient satisfaction and therapeutic outcomes [8].

Conventional mucoadhesive delivery platforms such as gels, ointments and patches have been widely employed for localized treatment of oral ulcers, yet each poses inherent drawbacks. Mucoadhesive patches, while capable of prolonged drug release, often face challenges with retention on the constantly mobile and moist oral mucosa. Their relatively rigid structure and bulkiness may lead to discomfort, unintentional detachment during speech or mastication, and difficulties in placement on irregular mucosal surfaces. In contrast, the film-forming spray (FFS) system offers several distinct advantages. Upon application, it forms a thin, flexible and transparent film that conforms closely to the lesion site, ensuring uniform coverage and intimate mucosal contact without causing mechanical irritation. The spray mechanism facilitates precise, painless application to even hard-to-access or sensitive regions of the oral cavity, avoiding the need for manual spreading. Furthermore, the resulting film is non-obstructive, does not interfere with oral functions, and resists wash-off by saliva, thus maintaining prolonged therapeutic presence at the site. These features collectively contribute to enhanced patient comfort, improved adherence, and superior clinical efficacy compared to traditional mucoadhesive formulations.

Film-o-spray or Film-forming spray (FFS) is the trailblazing drug delivery system in recent advances. As it is sprayed to the affected mucosal region, it forms a thin film over the lesion and adheres to the surface of the ulcer base by mucoadhesion using a polymeric agent. The delivery of the drug to the site of action is maintained in a sustained release fashion and saliva washing out of the drug from the site is prevented by the adhesive system [9]. The advantages of designing this film-forming spray are to increase its residence time and be effective over traditional topical gels and pastes. It offers fast and effective relief from mouth ulcer pain in a handy spray. It is easy to apply directly to the affected part of the mouth [2].

This research focuses on developing a mucoadhesive film-forming spray containing glycyrrhizin for the effective management of RAS. This novel approach aims to enhance therapeutic efficacy, ensure sustained drug release, and improved patient compliance compared to conventional treatments [10, 11].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Glycyrrhizin was purchased by TCI Pvt. Ltd., HPMC-E15, Propylene glycol and Ethanol was procured from Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd., and Eudragit-S100 was procured by Otto Chemie Pvt. Ltd.

Method of preparation

Formulation of film-forming solution

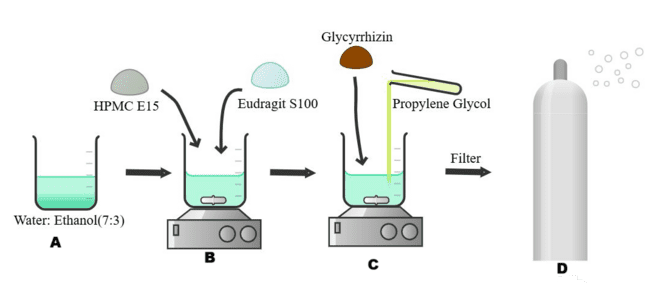

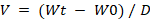

To create a film-forming solution, a combination of selected polymers were dissolved in a 7:3 v/v ethanol: water mixture stirred at 50 rpm using magnetic stirrer. A clear solution free of particles indicated full dissolution. The plasticizer, propylene glycol (PG), was then added to the polymer solution. For 15 min, the resultant mixture was stirred at 50 rpm to guarantee that the plasticizer was distributed evenly. Following careful weighing, glycyrrhizin was gradually added to the polymer-plasticizer solution and with constant stirring at 50 rpm for 30 min [12, 13] (fig. 1).

Screening of polymers

A variety of natural and synthetic polymers viz., xanthan gum, gellan gum, sodium hyaluronate, PVP-K30, PVP-K90, Eudragit-E100, HPMC-E15, and Eudragit-S100 were screened as film-forming agents for preparing an efficient film-forming spray in different solvent systems with polymer concentrations ranging from 0.1% to 2%. The polymers were selected based on drying time, film formation, and adhesion characteristics.

Fig. 1: Method of preparation of film-forming spray (A) Preparation of solvent system using ethanol: water (7:3 v/v). (B) Dissolution of selected polymers (HPMC E15 and Eudragit S100) into the solvent under magnetic stirring at 50 rpm until a clear solution is obtained. (C) Addition of propylene glycol as a plasticizer followed by gradual incorporation of glycyrrhizin with continuous stirring at 50 rpm for 30 min to ensure uniform dispersion. (D) Final solution filtered and transferred into a spray device for administration as a film-forming spray

Screening of solvents

To choose a solvent system that facilitates rapid drying and improves therapeutic efficacy, various solvents viz., ethanol, water and ethanol: water ratios of 7:3, 6:4, 4:6, and 3:7 were screened based on drying time, film formation, and adhesion.

Screening of plasticizer concentration

After a thorough analysis of the literature, propylene glycol (PG) was chosen as the plasticizer. The screening of the concentration of PG was decided by taking its different concentrations (2-8%) and with a constant polymer concentration and solvent volume. The observations are graded for its nature and effect on film formation.

Optimization by design of experiment

Box-Behnken Design (BBD) response surface methodology (RSM) was utilized to systematically investigate and optimize the formulation parameters. The design enabled the instantaneous assessment of selected independent process and formulation variables. A three-factor, three-level design was implemented to evaluate the influence of three independent variables: HPMC-E15 concentration (A), Eudragit-S100 concentration (B), and plasticizer (propylene glycol) concentration (C) on two dependent variables viz., viscosity (Y1) and drying time (Y2).

The factors were assessed at three levels—low (-1), middle (0), and high (+1)—based on initial screening experiments that determined the main variables and their suitable ranges. The selected levels were 1.5%, 2%, and 2.5% for HPMC-E15 (A); 1.5%, 2%, and 2.5% for Eudragit-S100 (B); and 2%, 5%, and 8% for propylene glycol (C). A total of 13 experimental runs were generated using Design Expert software (Version 13.0.3.0, Stat-Ease, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and the levels of these variables are summarized in table 1. The optimization process was guided by the desirability function approach to achieve the desired responses for viscosity and drying time. The model was evaluated by Lack of fit, regression coefficients, ANOVA, polynomial equations and response surface curves.

Table 1: Experimental design and parameters for 33 box behnken design batches of FFS_GLY

| Factors | Levels used | ||

| -1 | 0 | +1 | |

| HPMC E15 | 1.5% | 2% | 2.5% |

| Eudragit-S100 | 1.5% | 2% | 2.5% |

| PG | 2% | 5% | 8% |

| Dependent factors | Constrains | ||

| Viscosity (cPs) | Minimize | ||

| Drying time (sec) | Minimize | ||

Characterization and evaluation of film-forming spray

pH

The pH of the solution was measured using a digital pH meter (Elico L1612, India). Prior to measurement, the pH meter was calibrated using standard buffer solutions with pH values of 4.0, 7.0, and 10.0. The pH meter's electrode was dipped into 20 ml of the formulation and left to stabilize for a minute to measure the pH. Three measurements of each formulation's pH were made, and the average results were reported [14].

Viscosity

The viscosity of the solution was measured using a Brookfield viscometer (DV-II-LV, Brookfield, WI, USA) with spindle S-62. The spindle was revolved at 60 rpm at 25±1 °C. Prior to measurement, the samples were allowed to equilibrate for ten minutes. The viscosity of each formulation was measured using an average of three readings [15].

In vitro drying time

The drying time was determined by spraying the solution onto a glass slide and the time taken for drying was recorded by stopwatch [16].

Ex vivo drying time

The ex-vivo drying time was evaluated by modifying the above method. The buccal mucosa of the sheep was collected within 2 to 4 h after slaughter. The mucosa (5 cm) was placed onto the bottom surface of the beaker, and below that, a water bath was maintained at 37 °C. The solution was sprayed onto the mucosa, and the time taken for drying was recorded using a stopwatch [17].

Mucoadhesive strength

The mucoadhesive strength of the film-forming spray (FFS) was evaluated using a modified physical balance test. Properly sized mucosal pieces were placed on an inverted beaker. The FFS solution was sprayed onto a glass slide, allowing it to form a film, which was then suspended with a string and positioned onto the mucosa with an attached weight to facilitate adhesion. Water was incrementally added dropwise to the beaker on the opposite side of the balance until the adhesive bond between the film and mucosa was disrupted.

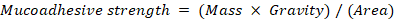

The mucoadhesive strength was calculated using the formula:

Where, M = mass (g), g = gravity (980 cm/s²), and A = 2 × (5+2 cm) = 14 cm².

The force required to separate the sample from the mucosa was recorded as the measure of mucoadhesive strength [18].

Water washability

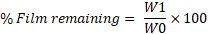

The water washability test was performed to quantitatively evaluate the resistance of the formed film against aqueous exposure. A uniform layer of the film-forming spray was applied to a pre-weighed clean glass slide and allowed to dry completely at room temperature. The dried film-coated slide was weighed again (W0) and then exposed to a gentle stream of distilled water maintained at a flow rate of approximately 100 ml/min. Upon contact with water, a stopwatch was started, and the film was subjected to continuous rinsing for a fixed duration of 10 min. After exposure, the slide was carefully dried using blotting paper and weighed again (W1).

The percentage of film remaining was calculated using the formula:

Where

W0 = Weight of glass slide with dried film before water exposure

W1= Weight of glass slide with remaining film after water exposure and drying [19].

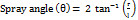

Spray angle and spray pattern

The spray angle was determined by adding 1% methyl blue to the formulation for enhanced visualization. A white sheet of paper was positioned horizontally at a distance of 15 cm from the nozzle [20]. After spraying, the radius of the circle formed on the paper was measured, and the spray angle was calculated using the following formula:

[21]

[21]

Where:

r = radius of the circle formed on the paper

l = distance from the paper surface to the nozzle

Volume per each actuation

The volume per actuation was evaluated to determine the amount of solution dispensed with each spray. To do this, the bottle containing the spray solution was weighed before and after each actuation. The spray volume (V) was then calculated using the formula:

Where V represents the spray volume, Wt is the weight of the solution after actuation, W0 is the weight of the solution before actuation, and D is the specific gravity of the film-forming solution [22].

Ex vivo permeation study

Franz diffusion cell was used to determine the permeability of the prepared FFS, using sheep’s buccal mucosa as the membrane. The mucosa was carefully positioned between the two compartments of the diffusion cell, creating a barrier between the donor and receptor compartments. A 5 ml volume of the solution was added to the donor compartment, while the receptor compartment was filled with phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and maintained at 37±0.5 °C. At predetermined intervals, aliquots were withdrawn from the receptor compartment and analysed by UV spectrophotometric technique to assess the permeability properties of the solution across the buccal membrane [23].

Mucosal retention study

At the end of the ex vivo permeation study (24 h), the mucosa was removed. The formulation on the surface of the mucosa was cleaned, and then it was washed repeatedly with pure water. Cleaned mucosal membrane was cut into small pieces and added to normal saline containing 30% (v/v) ethanol. The suspension was subjected to 30 min of sonication, allowed to cool, and subsequently filtered. The mucosal sample extracts were analyzed in UV-Spectrophotometer for the drug retained [24].

Preclinical evaluation of FFS_GLY

All animal experiments were conducted in compliance with Institutional Animal Ethics Committee guidelines (Approval No: AACP/IAEC/42/FEB2024/1). Male wistar rats (180–210 g), bred in the animal house of Al-Ameen College of Pharmacy, were acclimatized for seven days prior to experimentation. The study was divided into two phases: ulcer induction and treatment. Oral ulcers were induced using the acetic acid method, wherein rats were anesthetized with ketamine (10 mg/kg), and a 5 mm filter paper disc soaked in 50% acetic acid (15 µl**) was carefully applied to the oral mucosa for 30 seconds, resulting in reproducible ulcer formation within three days. From day 4 onwards, treatment was initiated by randomly assigning rats into five groups (n = 6 per group): Group I served as the normal control, Group II as the positive control, Group III received marketed drug (0.1% triamcinolone acetonide paste, TCA), Group IV received 3% glycyrrhizin solution, and Group V was treated with the test formulation (FFS_GLY, 3% w/v glycyrrhizin, delivering 3 mg per actuation), which was sprayed once daily. Treatment efficacy was evaluated at different time intervals using macroscopic, histological, and pharmacological parameters to assess healing progression and therapeutic outcomes. [26].

Pharmacodynamic evaluations

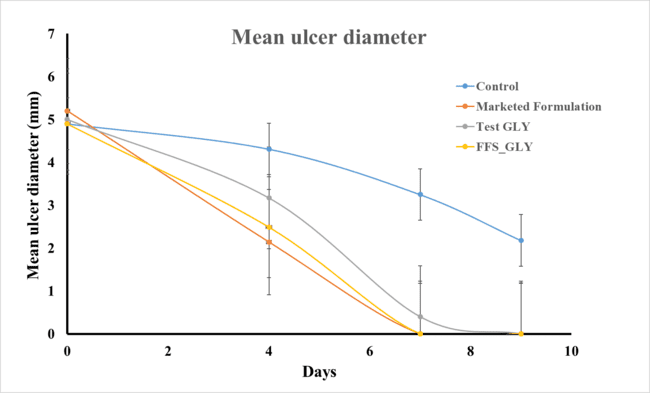

Mean ulcer diameter

The mean ulcer diameter was measured using Vernier calliper after initiation of the ulcer wounds. The measurements were recorded on alternate days on day 0, 4, 7, and 9. The size of the wounds will determine the healing of ulcers in each animal group [27].

Percentage ulcer closure

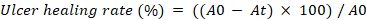

The degree of healing is represented as the percentage contraction of the ulcer area, and it was calculated for each animal using the following formula:

Where A0 and At represent the initial ulcer area and the ulcer area at the time of observation, respectively [28].

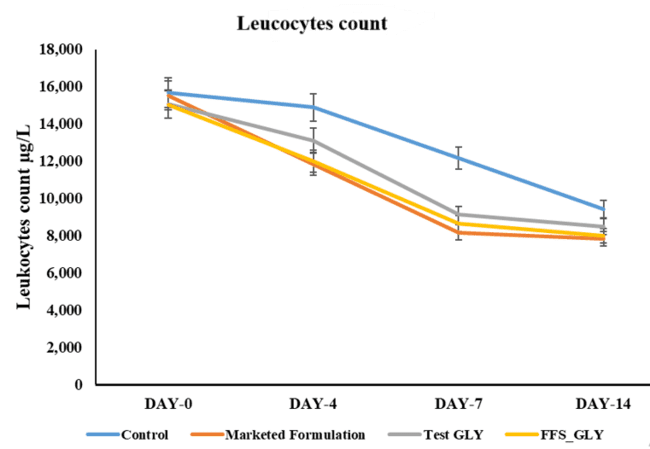

Extent of inflammation by leukocyte examination

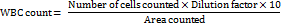

The leukocyte examination was performed by collecting blood samples from the lateral tail vein of rats at different intervals (days 0, 4, 7, and 14) after ulcer induction. To perform the white blood cell (WBC) count, the blood samples were first diluted with a suitable diluent, such as Turk's solution. A drop of this diluted blood was then carefully loaded onto a Neubauer chamber, and a cover slip was placed over the chamber to avoid air bubbles. The chamber was examined under a light microscope, and leukocytes were counted within the designated grid squares, typically the corner squares, due to their larger area. The count of leukocytes was recorded, and the total WBC count was calculated using the standard formula:

This evaluation was performed at different time intervals to estimate the extent and progression of inflammation in the rats following ulcer induction [29].

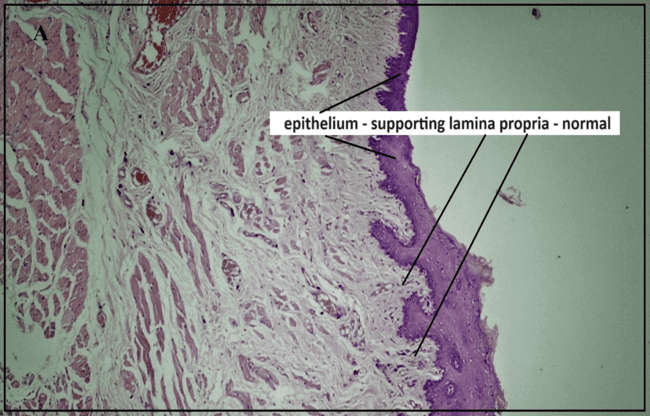

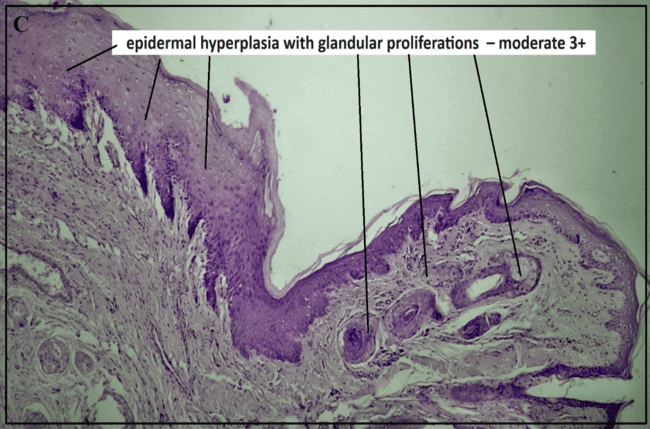

Histopathology analysis

On day 14, animals were euthanized, and oral mucosa tissue specimens were excised and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Bio-Optica) for 24-48 h to preserve the tissue structure. After fixation, the specimens were dehydrated through a series of graded alcohols (70%, 95%, and 100% ethanol), followed by clearing in xylene. The tissues were then imgded in paraffin blocks to allow for precise sectioning. Tissue sections of 4 μm thickness were cut using a microtome and placed on clean glass slides. These sections were then deparaffinised by passing through xylene and rehydrated through a decreasing gradient of alcohol, finally rinsed in distilled water. The tissue was stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histological analysis, where haematoxylin stained the nuclei, and eosin stained the cytoplasm and extracellular components. The staining process was followed by dehydration through alcohol and clearing with xylene, before mounting the slides with a coverslip. The stained sections were then evaluated under a light microscope. The changes in the tissue, including inflammatory cell infiltration, ulceration, and epithelial regeneration, were compared with the healthy oral epithelium to assess the extent of healing and inflammation [30, 31].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Screening of polymer type, solvent and plasticizers concentration

Screening of polymer types

The screening of natural and synthetic polymers revealed significant differences in film formation, drying time, and adherence, directly influencing their suitability for film-forming spray formulations (table 2). Among natural polymers, xanthan gum (0.1% and 0.3%) failed to form consistent films due to its high viscosity, lack of cohesive strength, and poor flexibility, leading to brittle or uneven films. Although its combination with gellan gum (1:1 and 1:1.5) improved drying times to 30 and 28 min, respectively, weak adherence limited its effectiveness. Gellan gum combined with sodium hyaluronate (1:1 and 2:1) demonstrated improved film properties, reducing drying time to 23–26 min with enhanced flexibility and adhesion. Sodium hyaluronate (0.5%) alone produced films with good adherence and moderate strength but lacked sufficient mechanical robustness for standalone use [32].

Among synthetic polymers, PVP-K30 (2%) failed to form a cohesive film due to its low molecular weight and insufficient polymeric interactions. At 3%, film integrity improved, achieving a 25-minute drying time with good adherence, though overall performance remained suboptimal. A 1:1 combination of PVP-K30 and sodium hyaluronate enhanced elasticity, adhesion, and solubility, reducing drying time to 23 min with improved film consistency. Eudragit-E100, HPMC-E15, and Eudragit-S100 demonstrated superior film-forming ability due to their balanced hydrophobic-hydrophilic nature, plasticity, and rapid solvent evaporation, resulting in faster drying times (20.3–22 min) and excellent adherence [33].

The choice of solvent system further influenced film performance. A 7:3 ethanol-water system significantly reduced drying time while improving film uniformity. Ethanol decreased polymer swelling and enhanced film strength, while water maintained flexibility, preventing brittleness. PVP-K30 and K90 dried within 2.46 and 3.04 min, respectively, with excellent film quality. Eudragit-E100 and HPMC-E15 dried even faster (1.50–2.12 min) with superior adherence, while Eudragit-S100 (1% and 2%) exhibited strong film formation with drying times of 1.54–1.56 min. The best results were achieved with a 1:1 or 2:1 combination of HPMC-E15 and Eudragit-S100, producing a 1.58-minute drying time with superior film formation (+++) [34].

Overall, polymer selection was based on mechanical strength, film flexibility, adherence, and drying efficiency. Poor film-forming agents such as xanthan gum and low-concentration PVP-K30 were eliminated due to inadequate film integrity and slow drying. HPMC-E15 and Eudragit-S100 emerged as the optimal candidates due to their excellent film-forming properties, rapid drying, strong adhesion, and enhanced stability, making them ideal for buccal film-forming spray formulations [35].

Screening of solvent system

A 7:3 ethanol-to-water ratio was selected as the optimal solvent system for buccal film formulations due to its ability to enhance polymer dissolution, accelerate solvent evaporation, and improve film formation. Ethanol, a volatile solvent, ensures rapid drying, critical for spray applications, and effectively dissolves hydrophobic polymers like Eudragit-E100 and Eudragit-S100, preventing phase separation. Water maintains polymer flexibility, avoiding brittleness in high-ethanol formulations. This ratio balances fast drying, optimal flexibility, and uniform film formation while ensuring ideal sprayability and viscosity, making it ideal for buccal film sprays [36] (table 3).

Screening of plasticizer concentration

Propylene glycol (PG) was tested at 2–8% (table 4), with 5% PG providing the optimal balance of viscosity and film integrity. As a plasticizer, PG enhances film flexibility, uniformity, and adhesion, crucial for maintaining film performance on mucosal surfaces. The 5% concentration ensures ideal sprayability and film quality, making it essential for the formulation [37].

Optimization design

Optimization of film-forming spray using response surface methodology

To achieve an optimal balance between viscosity and drying time, response surface methodology (RSM) was utilized through a Box-Behnken Design (BBD) in Design Expert software (version 13.0.0). The formulation was optimized by systematically evaluating the effects of HPMC-E15 (A), Eudragit-S100 (B), and propylene glycol (PG) (C) as independent variables. A 13-run BBD was employed with three factors at three levels, allowing for the efficient assessment of main, interaction, and quadratic effects while minimizing experimental runs. Compared to the central composite design, BBD requires fewer experiments while effectively detecting curvatures in response, making it highly suitable for optimizing formulation parameters.

Table 2: Screening of polymers types and its concentration

| Water as solvent system | |||||||

| Batch | Natural polymers | Polymers | Amount (%) w/w | Drying time (min) | Film formation | Adherence | |

| F1 | Xanthan Gum | 0.1% | - | - | - | ||

| F2 | Xanthan Gum | 0.3% | - | - | - | ||

| F3 | Gellan Gum | 0.3% | - | - | - | ||

| F4 | Gellan Gum | 0.5% | - | - | - | ||

| F5 | Xanthan gum+Gellan gum | 1:1 | 30+ | + | - | ||

| F6 | Xanthan gum+Gellan gum | 1:1.5 | 28 | + | - | ||

| F7 | Sodium Hyaluronate | 0.25% | - | - | - | ||

| F8 | Sodium Hyaluronate | 0.5% | 28 | + | + | ||

| F9 | Xanthan gum+sodium hyaluronate | 1:0.5 | 26 | + | + | ||

| F10 | Xanthan gum+sodium hyaluronate | 1:1 | 22 | + | + | ||

| F11 | Gellan gum+Sodium hyaluronate | 2:1 (1%:0.5%) | 26 | ++ | + | ||

| F12 | Gellan gum+Sodium hyaluronate | 1:1 | 23 | + | + | ||

| F12 | Synthetic polymers | PVP-K30 | 2% | - | - | - | |

| F13 | PVP-K30 | 3% | 25 | + | + | ||

| F14 | PVP-K30+Sodium hyaluronate | 1:1 | 23 | + | ++ | ||

| F15 | Eudragit-E100 | 2% | 22 | + | + | ||

| F16 | HPMC-E15 | 2% | 20.31 | + | + | ||

| F17 | Eudragit-S100 | 2% | 21.5 | + | + | ||

| Combination of Ethanol+Water as solvent system | |||||||

| F15 | Synthetic polymers | PVP K30 | 2% | 2.46 | ++ | + | |

| F16 | PVP K90 | 1% | 3.04 | + | + | ||

| F18 | Eudragit-E100 | 2% | 2.12 | ++ | ++ | ||

| F19 | HPMC-E15 | 1% | 1.50 | ++ | ++ | ||

| F20 | HPMC-E15 | 2% | 1.52 | ++ | ++ | ||

| F21 | Eudragit-S100 | 1% | 1.54 | ++ | + | ||

| F22 | Eudragit-S100 | 2% | 1.56 | ++ | ++ | ||

| F23 | HPMC E15+Eudragit-S100 | 1:1 | 1.58 | +++ | ++ | ||

| F24 | HPMC E15+Eudragit-S100 | 2:1 | 1.58 | +++ | +++ | ||

Note: Film formation (Excellent+++, Good++, Acceptable+,-No film formed), Adherence (Excellent+++, Good++, Acceptable+).

Table 3: Selection of solvents and their solvents

| S. No. | Solvents | Solubility of polymer | Drying time (min) |

| Water | Insoluble | - | |

| Water: Ethanol (7:3) | Insoluble | - | |

| Water: Ethanol (6:4) | Insoluble | - | |

| Water: Ethanol (4:6) | Moderately soluble | 2.14 | |

| Water: Ethanol (3:7) | Highly soluble | 1.56 |

Table 4: Screening of plasticizer concentration

| S. No. | Concentration | Physical state (Nature of liquid) | Film brittleness and cracking |

| 0.5% | Watery | + | |

| 1% | Watery | + | |

| 2% | Less viscous | - | |

| 3% | Less viscous | - | |

| 4% | viscous | - | |

| 5% | viscous | - |

n=3., ‘+’: less brittleness and no cracking; ‘-’: brittleness and cracking

Polynomial equations and statistical analysis

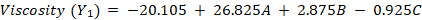

The optimization study yielded the following polynomial equations describing the influence of the independent variables:

The equations indicate that increasing HPMC-E15 (A) significantly increases both viscosity (+26.825) and drying time (+9.062). Eudragit-S100 (B) has a minor positive effect on viscosity (+2.875) and drying time (+0.755), whereas PG (C) slightly decreases viscosity (-0.925) but increases drying time (+0.586). The absence of interaction terms (AB, AC and BC) confirms that the factors act independently, following an orthogonal BBD structure, ensuring unbiased estimation and model reliability.

ANOVA analysis demonstrated that the model was statistically significant (p<0.0001) for both viscosity (Y₁) and drying time (Y₂). The adjusted R² values (0.657 for Y₁ and 0.571 for Y₂) indicated a good model fit, with predicted R² values confirming reasonable predictive accuracy. The model F-values (5.13 for Y₁ and 4.79 for Y₂) further validated its statistical significance, while lack-of-fit F-values (3.08 for Y₁ and 0.59 for Y₂) confirmed the model’s suitability by showing that lack of fit was not significant relative to pure error.

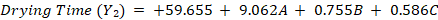

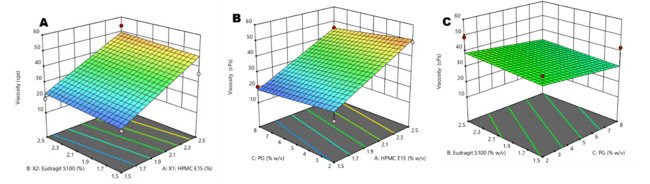

Response surface analysis

Response surface plots illustrated a linear effect of the independent variables on viscosity (fig. 2) and drying time (fig. 3). Increasing the concentrations of HPMC-E15, Eudragit-S100, and PG proportionally increased viscosity (adjusted R² = 0.657, predicted R² = 0.446) and drying time (adjusted R² = 0.571, predicted R² = 0.294). These findings highlights the direct relationship between polymer concentration and film properties, ensuring systematic control over formulation characteristics.

Fig. 2: Response Surface Plots showing the effect of formulation variables on viscosity: (a) Effect of HPMC E15 and Eudragit S100 (b) Effect of propylene glycol (PG) and Eudragit S100 (c) Effect of propylene glycol (PG) and HPMC E15

Fig. 3: Response surface plots showing the effect of formulation variables on drying time: (a) Effect of HPMC E15 and Eudragit S100 (b) Effect of propylene glycol (PG) and Eudragit S100(c) Effect of propylene glycol (PG) and HPMC E15

The optimized film-forming spray (FFS) formulation exhibited the desired viscosity, rapid drying time, and superior film-forming properties, making it a promising candidate for therapeutic application. The overlay plot provided a visual representation of the optimal range for independent variables, confirming the robustness of the selected formulation. The results for optimization have been illustrated in table 5, and the predictive accuracy of the model was validated through checkpoint formulations, as shown in 1table 6.

Table 5: Experimentally determined values of viscosity and drying time of FFS_GLY by 33 box-behnken design

| S. No. | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Response 1 | Response 2 |

| Run | A: HPMC E15 (%) | B: Eudragit S100 (%) | C: PG (%) | Viscosity (cPs) | Drying time (sec) |

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 2 | 48.8±0.0054 | 82.03±0.012 |

| 2 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 5 | 35.5±0.0063 | 83.44±0.009 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | 18.5±0.0048 | 72.08±0.011 |

| 4 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 19.2±0.0051 | 75.12±0.013 |

| 5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 54±0.0087 | 89.32±0.015 |

| 6 | 1.5 | 2 | 8 | 20.5±0.0036 | 84.52±0.010 |

| 7 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 5 | 18.7±0.0061 | 76.29±0.012 |

| 8 | 2.5 | 2 | 2 | 49.2±0.0072 | 85.24±0.009 |

| 9 | 2 | 1.5 | 2 | 41.5±0.0049 | 84.36±0.014 |

| 10 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 29.5±0.0017 | 83.22±0.007 |

| 11 | 2 | 1.5 | 8 | 42.3±0.0055 | 83.18±0.012 |

| 12 | 2.5 | 2 | 8 | 45.5±0.0071 | 86.26±0.013 |

| 13 | 2 | 2.5 | 8 | 27.5±0.0064 | 83.82±0.008 |

n=6, Data given in mean±SD

Table 6: Check point formulation parameters and result

| Independent variables | Dependent variables | Predicted values | Experimental value |

A= HPMC-E15 B= Eudragit-S100, C=PG |

Viscosity (cPs) | 20.76 | 19.28±0.019 |

| Drying time (sec) | 76.71 | 75.56±0.025 |

n=6, Data given in mean±SD

Characterization

pH

The pH values of all formulations were in the range of 6.52-6.72, with the optimized F4 formulation exhibiting a pH of 6.68, closely matching the natural buccal pH (6.8). This ensures mucosal compatibility, minimizes irritation, and enhances patient comfort. A pH near physiological levels also promotes drug stability and solubility, facilitating efficient drug release and absorption while maintaining mucosal integrity [38].

Viscosity

The viscosity of formulations F1–F13 ranged from 17±0.05 to 55±0.05 cPs (table 5), with the optimized F4 formulation at 19.28±0.019 cPs, which is within the acceptable limit (<30 cPs) for fast-film sprays (FFS). An optimal viscosity is essential for easy spraying, uniform film formation, and effective mucoadhesion without excessive thickness. This enhances spreadability, bioavailability, and controlled drug release, ensuring efficient therapeutic action while maintaining patient compliance [39].

In vitro drying time

The in vitro drying time of F1–F13 ranged from 72.08 to 89.32 seconds (table 5), with the optimized F4 formulation drying in 75.12±0.12 seconds. Rapid drying is crucial for buccal formulations, as it ensures quick film formation and adherence to the buccal mucosa, preventing premature loss due to saliva wash-off. The optimal drying time of F4 enhances drug retention and facilitates controlled drug release, making it a suitable candidate for buccal delivery [40].

Ex-vivo drying time

The three best formulations (F3, F4, and F7) were selected based on viscosity and drying time for further evaluation (fig. 4). Ex-vivo drying time results (table 7) indicate that the drying times were 43.85±0.017, 46.18±0.010, and 45.44±0.008 seconds, respectively. These values demonstrate a faster drying rate in ex-vivo compared to in vitro conditions. The reduced ex-vivo drying time can be attributed to factors such as mucosal absorption, biological surface interaction, and enhanced moisture wicking, which facilitate quicker solvent evaporation. Achieving an optimal drying time is crucial for effective film formation, ensuring strong mucosal adhesion, sustained drug release, and improved therapeutic efficacy in buccal drug delivery [41].

Mucoadhesion test

Mucoadhesive strength plays a crucial role in buccal film-forming sprays, directly impacting drug retention and therapeutic efficacy. An ideal adhesive force should ensure prolonged mucosal contact without causing discomfort or tissue damage. Reported mucoadhesive strengths for buccal films range from 6.5 N to 7.3 N for optimal adhesion without irritation. The mucoadhesive strength of selected three formulations is depicted in table 7 and fig. 5. Formulation F4, with a mucoadhesive strength of 577.5 dynes/cm² (~0.05775 N/cm²), exhibits moderate adhesion, likely minimizing discomfort while ensuring adequate drug retention. Excessive adhesion may cause mucosal injury and complicate film removal, whereas insufficient adhesion risks premature detachment and reduced efficacy. Thus, optimizing mucoadhesive properties is critical to achieving a balance between strong adhesion and patient comfort, ensuring effective and sustained buccal drug delivery [42].

Water washability

The water washability test was conducted to assess the resistance of the formulated films to aqueous exposure. As shown in table 7, all tested formulations exhibited a high percentage of film retention after continuous rinsing, indicating minimal wash-off and good film integrity. This performance highlights the effective film-forming ability of the formulations, supported by the cohesive strength and hydrophobic nature of the selected polymers. The films were able to maintain their structure under simulated aqueous conditions, suggesting that they can adhere well to application surfaces and resist premature disintegration. Such water-resistant behavior is desirable for formulations intended for use in moist environments, as it contributes to prolonged residence time and consistent therapeutic performance.

Fig. 4: Ex-vivo drying time; A. represents FFS sprayed at 0 min, B. Represents dried film at 46.18 sec

Table 7: Ex-vivo drying time, Mucoadhesion and water washability test and their observations

| Evaluation parameters | F3 | F4 | F7 |

| Ex-vivo drying time | 43.85±0.017 sec | 46.18±0.010 sec | 45.44±0.008 sec |

| Mucoadhesion test | 0.03178±0.0087 N/cm2 | 0.05775±0.015 N/cm2 | 0.05035±0.003 N/cm2 |

| Water washability Grading | 90.28±1.03% | 92.96±0.98% | 89.98±1.06% |

n=6, Data given in mean±SD

Spray pattern and spray angle

The spray angle of F4 was determined to be 10.28º (fig. 6), indicating a narrow and focused spray pattern, which ensures targeted delivery and efficient drug distribution. A precise spray pattern enhances drug coverage on the buccal mucosa, ensuring uniform deposition, which is vital for buccal drug administration [44].

Volume per spray

The volume per spray for F4 was 0.097 ml (97 µl**/spray), an optimal dose ensuring uniform drug distribution and precise targeting at the application site [45].

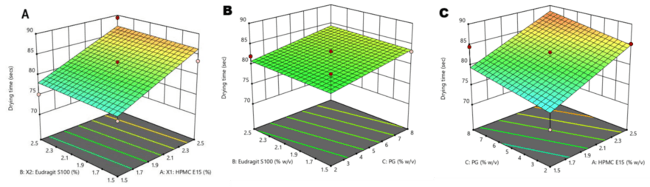

Ex-vivo permeation study

The ex-vivo permeation study revealed that pure glycyrrhizin (GLY) exhibited 8% permeation through the buccal mucosa over 24 h, while the test formulation (FFS_GLY) demonstrated 13% permeation (fig. 7). The presence of PG enhanced permeation by 3%, improving drug penetration and retention. This supports the formulation’s ability to deliver the drug efficiently to the buccal mucosa, ensuring topical action and controlled release over an extended period [46].

Mucosal drug retention study

The mucosal drug retention of formulation F4 was found to be 6.105 mg/cm² after 24 h, indicating strong bioadhesion and prolonged residence time on the buccal mucosa. This high level of retention is particularly significant, as it directly supports the observed in vivo ulcer healing outcomes, where animals treated with F4 exhibited faster re-epithelialization, reduced inflammation, and enhanced tissue regeneration compared to controls. The ability of the formulation to remain adhered at the ulcer site for extended periods ensures sustained local availability of glycyrrhizin, thereby maintaining therapeutic concentrations at the target tissue. These ex vivo findings, when viewed alongside the in vivo healing response, reinforce the potential of F4 as a clinically viable system for localized, sustained-release buccal drug delivery [47].

Preclinical evaluation of FFS_GLY

Mean ulcer diameter

The mean ulcer diameter data (table 8 and fig. 8) showed that both the test formulation (FFS_GLY) and the marketed formulation (topical steroid) resulted in a significant reduction in ulcer diameter over 7 days, indicating positive healing progress. Among the tested groups, the FFS_GLY formulation demonstrated the most rapid and complete healing, with the ulcer diameter reaching zero by day 6, comparable to the marketed formulation, which also achieved complete healing around the same time. The Test GLY (3% glycyrrhizin solution) showed slower healing than both FFS_GLY and the marketed product, but still achieved complete recovery by day 8. In contrast, the control group exhibited a gradual and incomplete healing trend, with ulcer diameter remaining above 2 mm even on day 8. This clear difference underscores the effectiveness of FFS_GLY in promoting ulcer healing. The formulation's buccal compatibility, sustained release properties, and non-synthetic nature enhance its potential for safe and effective topical application, supporting its therapeutic efficacy in buccal ulcer treatment [48].

Fig. 5: Percentage comparative drug permeation of pure glycyrrhizin and test FFS

Fig. 6: Mean ulcer diameter following different treatments

Table 8: Mean ulcer diameter and their observations on day 0, 4, 7 and 9

| S. No. | Group | Day-0 | Day-4 | Day-7 | Day-9 |

| Control | 4.9±0.05 | 4.31±0.07 | 3.25±0.14 | 2.18±0.12 | |

| Marketed Formulation | 5.2±0.05 | 2.14±0.05 | 0.0±0.00 | 0.0±0.00 | |

| Test GLY | 5.0±0.08 | 3.17±0.10 | 0.40±0.05 | 0.0±0.00 | |

| Test FFS | 4.9±0.06 | 2.49±0.06 | 0.0±0.00 | 0.0±0.00 |

n=6, p=0.001, Data given in mean±SD

Extent of inflammation by leukocyte examination

The extent of inflammation was assessed by leukocyte counts (fig. 9). Normal leukocyte counts for male wistar rats ranged from 4,400 to 14,800 cells/mm³. After ulcer induction, the count increased to 15,000–15,800 cells/mm³ across all groups, indicating an inflammatory response. Over the 14 d treatment period, a progressive decrease in leukocyte levels was observed in all treated groups. The test formulation (FFS_GLY) showed the most pronounced reduction in leukocyte count by day 14, reaching levels close to the physiological norm, followed closely by the marketed formulation. The Test GLY (3% glycyrrhizin solution) exhibited a moderate reduction, while the control group maintained relatively higher leukocyte levels throughout, indicating persistent inflammation. The faster and more consistent reduction in leukocyte count with FFS_GLY highlights its superior anti-inflammatory potential. This suggests that FFS_GLY is not only effective in reducing inflammation but also offers better therapeutic outcomes than the marketed topical steroid, supporting its potential as a buccal delivery formulation for enhanced healing and inflammation control [49].

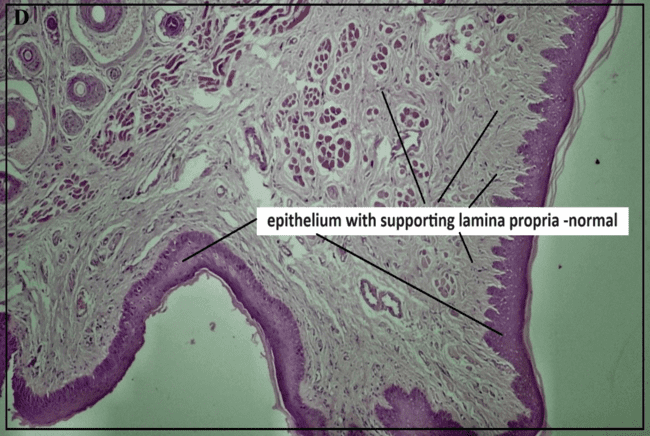

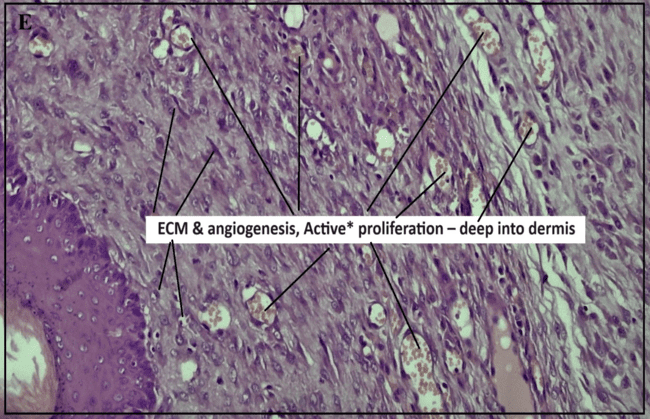

Histopathology study

The histopathological study (fig. 9) assessed healing response, cellular infiltration, and tissue abnormalities. The normal control group (A) showed intact epithelium and normal lingual papillae, while the ulcer initiation group (B) exhibited epithelial hyperplasia, inflammation, and submucosal necrosis, indicating significant tissue damage. The positive control group (C) showed moderate epidermal and glandular hyperplasia with inflammation, confirming the ulcer model's effectiveness. The marketed drug (0.1% TCA) (Group D) led to normalized epithelial structure and angiogenesis, demonstrating effective healing.

In contrast, the test formulation (FFS_GLY) treatment displayed active epithelial proliferation, ECM formation, and deep dermal angiogenesis, indicating a robust healing response. This suggests that FFS_GLY not only matches but may surpass the healing efficacy of the marketed formulation, making it a promising therapeutic option for recurrent oral ulcers [1].

Fig. 7: Leucocyte count following different treatments on day 0, 4, 9, and 14

Fig. 8: Histopathological study reports of buccal mucosa under different treatment conditions: (a) Positive control (b) Ulcer-induced buccal mucosa(c) Pure glycyrrhizin (d) Marketed group, (e) test FFS group

CONCLUSION

The study successfully formulated and optimized a glycyrrhizin-based film-forming spray (FFS_GLY) for the effective management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS). The optimized formulation demonstrated rapid drying time, strong mucoadhesion, and sustained mucosal drug retention, ensuring prolonged therapeutic action at the ulcer site. Preclinical evaluations revealed significant ulcer healing, enhanced epithelial regeneration, and angiogenesis, with statistically significant improvements in ulcer diameter reduction (p<0.05) and WBC normalization (p<0.05) compared to untreated and standard steroid-treated groups. While FFS_GLY offers clear advantages over conventional therapies—such as localized delivery, reduced systemic exposure, and improved patient compliance—potential scalability challenges, such as nozzle clogging due to polymeric components, were noted. These can be mitigated through optimization of polymer concentration, particle size reduction via micronization or homogenization, use of anti-clogging nozzle designs, and periodic cleaning protocols during large-scale production, ensuring robust manufacturability. These findings position FFS_GLY as a promising alternative for RAS treatment. However, further clinical studies are warranted to confirm its safety and therapeutic efficacy in human populations. This novel glycyrrhizin-based approach represents a meaningful advancement in oral care and lays the groundwork for future innovation in patient-friendly mucosal therapies.

FUNDING

This study was carried out independently, without any external financial support.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

The author contributions are as follows: Ayesha Syed and Preeti Karwa were responsible for conceptualization, supervision, and review and editing of the manuscript. Sohal Mallick contributed to writing the original draft, writing, and data interpretation. Prithivirajan S was involved in investigation and writing the original draft.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Dorsareh F, Radan M, Yadegari Z, Agha Hosseini F. The effects of glycyrrhizin mouthwash on recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a randomized clinical trial. Oral Dis. 2020;26(3):655-61.

Akintoye SO, Greenberg MS. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Dent Clin North Am. 2014;58(2):281-97. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2013.12.002, PMID 24655523.

Rivera C. Essentials of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: an update. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24(6):e709-20.

Shulman JD. An exploration of point annual and lifetime prevalence in characterizing recurrent aphthous stomatitis in USA children and youths. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33(9):558-66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00241.x, PMID 15357677.

Altenburg A, Abdel Naser MB, Seeber H, Abdallah M, Zouboulis CC. Practical aspects of management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(8):1019-26. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02393.x, PMID 17714120.

Belenguer Guallar I, Jimenez Soriano Y, Claramunt Lozano A. Treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. A literature review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014;6(2):e168-74. doi: 10.4317/jced.51401, PMID 24790718.

Preeti L, Magesh KT, Rajkumar K, Karthik R. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15(3):252-6. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.86669, PMID 22144824.

Scully C, Porter S. Oral mucosal disease: recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(3):198-206. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.07.201, PMID 17850936.

Altenburg A, El Haj N, Micheli C, Puttkammer M, Abdel Naser MB, Zouboulis CC. The treatment of chronic recurrent oral aphthous ulcers. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(40):665-73. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0665, PMID 25346356.

Shashy RG, Ridley MB. Aphthous ulcers: a difficult clinical entity. Am J Otolaryngol. 2000;21(6):389-93. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2000.18872, PMID 11115523.

Nolan A, Lamey PJ, Milligan KA, Forsyth A. Recurrent aphthous ulceration and food sensitivity. J Oral Pathol Med. 1991;20(10):473-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00406.x, PMID 1753349.

Slebioda Z, Szponar E, Kowalska A. Etiopathogenesis of recurrent aphthous stomatitis and the role of immunologic aspects: literature review. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2014;62(3):205-15. doi: 10.1007/s00005-013-0261-y, PMID 24217985.

Chiang CP, Yu Fong Chang J, Wang YP, Wu YH, Wu YC, Sun A. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis etiology serum autoantibodies anemia hematinic deficiencies and management. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118(9):1279-89. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.10.023, PMID 30446298.

Field EA, Allan RB. Review article: oral ulceration aetiopathogenesis clinical diagnosis and management in the gastrointestinal clinic. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(10):949-62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01782.x, PMID 14616160.

Sharda N, Sharma A, Sharma A, Singh V, Sharma V. Therapeutic options in recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a review. J Adv Med Scie Res. 2019;7(6):105-10.

Armanini D, Fiore C, Mattarello MJ, Bielenberg J, Palermo M. History of the endocrine effects of licorice. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2002;110(6):257-61. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34587, PMID 12373628.

Fiore C, Eisenhut M, Krausse R, Ragazzi E, Pellati D, Armanini D. Antiviral effects of Glycyrrhiza species. Phytother Res. 2008;22(2):141-8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2295, PMID 17886224.

Kao TC, Wu CH, Yen GC. Bioactivity and potential health benefits of licorice. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(3):542-53. doi: 10.1021/jf404939f, PMID 24377378.

Biondi DM, Rocco C, Ruberto G. New dihydrostilbene derivatives from Glycyrrhiza glabra leaves. J Nat Prod. 2005;68(1):109-12. doi: 10.1021/np050034q.

Hattori T, Ikematsu S, Koito A, Matsushita S, Maeda Y, Hada M. Preventive effect of glycyrrhizin on HIV replication in patients with hemophilia. Japan J Cancer Res. 1989;80(4):334-9. doi: 1016/0166‑3542(89)90035‑1.

Isbrucker RA, Burdock GA. Risk and safety assessment on the consumption of licorice root (Glycyrrhiza sp.) its extract and powder as a food ingredient with emphasis on the pharmacology and toxicology of glycyrrhizin. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2006;46(3):167-92. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.06.002, PMID 16884839.

Sahebkar A, Henrotin Y. Analgesic efficacy and safety of Phytalgic®, a dietary supplement containing Urtica dioica, fish oil and vitamin E, in osteoarthritis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2016;23(10):1075-81.

Gupta VK, Fatima A, Faridi U, Negi AS, Shanker K, Kumar JK. Antimicrobial potential of Glycyrrhiza glabra roots. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;116(2):377-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.037, PMID 18182260.

Sun Y, Liu N, Guan X, Wu H, Xu F, Sun J. Pharmacological effects of glycyrrhizic acid and its metabolites in inflammation and cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2019;144:212-26. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1001018.

Li JY, Cao HY, Liu P, Cheng GH, Sun MY. Glycyrrhizic acid in the treatment of liver diseases: literature review. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:872139. doi: 10.1155/2014/872139, PMID 24963489.

Shen F, Zhang Y, Yao Y, Liu H, Li L. Advances in glycyrrhizic acid-based nanomedicine for cancer therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:730765.

Geethangili M, Tzeng YM. Review of phytochemistry and pharmacology of Glycyrrhiza uralensis. J Food Drug Anal. 2011;19(2):230-44. doi: 10.1016/S1021‑9498(11)60036-4.

Jin J, Shuang S, Zhang Z, Wu D, Guo Q, Zhang J. Glycyrrhizic acid nanoparticles inhibit inflammation in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;31:311-7.

Shaikh R, Raj Singh TR, Garland MJ, Woolfson AD, Donnelly RF. Mucoadhesive drug delivery systems. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3(1):89-100. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.76478, PMID 21430958.

Andrews GP, Laverty TP, Jones DS. Mucoadhesive polymeric platforms for controlled drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;71(3):505-18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.09.028, PMID 18984051.

Carvalho FC, Bruschi ML, Evangelista RC, Gremiao MP. Mucoadhesive drug delivery systems. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2010;46(1):1-17. doi: 10.1590/S1984-82502010000100002.

Gandhi RB, Robinson JR. Oral cavity as a site for bioadhesive drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1994;13(1-2):43-74. doi: 10.1016/0169-409X(94)90026-4.

Nafee NA, Boraie MA, Ismail FA, Mortada LM. Design and characterization of mucoadhesive buccal patches containing cetylpyridinium chloride. Acta Pharm. 2003;53(3):199-212. PMID 14769243.

Bruschi ML, De Freitas O. Oral bioadhesive drug delivery systems. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2005;31(3):293-310. doi: 10.1081/ddc-52073, PMID 15830725.

Carvalho FC, Salata GC, Calio ML, Gremiao MP. Development and in vitro evaluation of polysaccharide-based film-forming systems for buccal delivery of dexamethasone. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;87(1):467-73. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.07.046.

Broy P, Berard A. Gestational exposure to antidepressants and the risk of spontaneous abortion: a review. Curr Drug Deliv. 2010;7(1):76-92. doi: 10.2174/156720110790396508, PMID 19863482.

Shaikh HK, Kshirsagar RV, Patil SG. Formulation and evaluation of in situ gel of metronidazole for the treatment of periodontitis. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21(4):493-7.

Thakur N, Garg G, Sharma PK, Kumar N, Gupta UD. Formulation and evaluation of fast-dissolving oral film of diltiazem hydrochloride. Arch PharmSci Res. 2011;3(1):132-6.

Cilurzo F, Musazzi UM, Franze S, Selmin F, Minghetti P. Orodispersible dosage forms with taste masking properties: an overview. Int J Pharm. 2018;536(2):419-28.

Peh KK, Wong CF. Polymeric films as vehicle for buccal delivery: swelling mechanical and bioadhesive properties. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 1999;2(2):53-61. PMID 10952770.

Irfan M, Rabel S, Bukhtar Q, Qadir MI, Jabeen F, Khan A. Orally disintegrating films: a modern expansion in drug delivery system. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24(5):537-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.02.024, PMID 27752225.

Guo JH. Investigating the surface free energy and adhesion of hydrocolloids on soft tissues. J Adhes Sci Technol. 1994;8(4):393-401.

Siepmann J, Peppas NA. Modeling of drug release from delivery systems based on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC). Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;48(2-3):139-57. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00112-0, PMID 11369079.

Vuddanda PR, Mishra A, Singh SK. Development and characterization of novel flavonoid-based mucoadhesive film for oral care. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2017;18(3):938-46.

Qiu Y, Park K. Environment-sensitive hydrogels for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;53(3):321-39. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00203-4, PMID 11744175.

Nayak AK, Pal D. Development of pH-sensitive tamarind seed polysaccharide-alginate composite beads for controlled diclofenac sodium delivery using response surface methodology. Int J Biol Macromol. 2011;49(4):784-93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.07.013, PMID 21816168.

Hernandez Garcia D, Granado Serrano AB, Martin Gari M, Naudi A, Serrano JC. Efficacy of Panax ginseng supplementation on blood lipid profile. A meta-analysis and systematic review of clinical randomized trials. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;243:112090. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112090, PMID 31315027.

Bhatia M, Sood S, Kumar V, Mittal A. Evaluation of anti-ulcer activity of Ocimum sanctum Linn. In rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43(6):640-4.

Bhattamisra SK, Koh HM, Lim SY, Choudhury H, Al Hanbali OA. Gastroprotective effect of azilsartan on ethanol and indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2019;392(12):1581-92.

Takeuchi K, Amagase K. Roles of cyclooxygenase prostaglandin E2 and EP receptors in mucosal protection and ulcer healing in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24(18):2002-11. doi: 10.2174/1381612824666180629111227, PMID 29956615.