Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 204-218Original Article

COMPUTATIONAL SCREENING OF NATURAL COMPOUNDS AS POTENTIAL AURORA A KINASE INHIBITORS FOR LEUKEMIA CANCER TREATMENT: A MULTI-STEP IN SILICO APPROACH

JOHRA KHAN*

Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Majmaah University, Majmaah-11952, Saudi Arabia

*Corresponding author: Johra Khan; *Email: j.khan@mu.edu.sa

Received: 19 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 13 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The overexpression of aurora a kinase is associated with leukaemia as it is an essential regulator of mitotic progression, rendering it a promising therapeutic target. This study employed a multi-step in silico strategy that incorporated computational screening, molecular docking, Density Functional Theory (DFT) analysis, free energy calculations (MM-GBSA), and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to evaluate the potential of natural compounds as Aurora A kinase inhibitors.

Methods: An initial virtual screening of 3,093 natural compounds from the Selleckchem library was performed. Drug-likeness was assessed using Lipinski’s Rule of Five, which filters compounds based on key pharmacokinetic parameters: molecular weight (≤ 500 Da), LogP (≤ 5), hydrogen bond donors (≤ 5), and hydrogen bond acceptors (≤ 10). A total of 2,045 compounds that satisfied all these criteria were selected for further analysis and bioactivity evaluation.

Results: After ML-based QSAR screening, molecular docking identified 683 ligands with binding affinities of ≤-6.0 kcal/mol. Out of all natural compounds, PubChem CID: 94381 (Coumarin 7) and PubChem CID: 1830 (7-Iodo-7-deaza-D-guanosine) showed minimal RMSD (0.1-0.3 nm), and high hydrogen bonding (2-6 stable contacts) during the 100 ns MD simulations, suggesting stable binding within the aurora A kinase active site. The strong binding affinity of MM-GBSA was further validated by the binding free energy calculations, which showed favourable values of ΔG =-27.93 kcal/mol (94381) and -27.50 kcal/mol (1830).

Conclusion: Further, with a dipole moment of 2.80 D, 1830 had great electrical stability, and the lowest HOMO-LUMO gap (-0.1580 eV/-0.1311 eV) was observed in 94381, according to DFT calculations, which indicated significant reactivity. Additionally, synthetic accessibility scores of 3.19 and 4.00, respectively, and iLOGP (integrative octanol–water partition coefficient) values of 2.46 (94381) and 1.57 (1830), both compounds showed ideal drug-like characteristics and may be developed further.

Keywords: Aurora a kinase, Molecular docking, Free energy calculations, Acute myeloid leukaemia, Therapeutic target

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55338 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Leukaemia is a blood and bone marrow malignancy that affects individuals worldwide. It has been predicted that adults will be the primary demographic affected by the anticipated 22,010 cases of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) in the United States. Additionally, 11,090 individuals will succumb to AML in the same year [1].

The overexpression and gene amplification of these enzymes are the causes of cancer [2]. The inhibition of these enzymes has been suggested as a potential treatment option for chemotherapy in numerous studies [3]. In 2009, Howard et al. described the FBDD process for the development of Aurora kinase A and B inhibitors that can be employed in cancer chemotherapy [4]. The study of leukaemia is being revolutionised by the identification and inhibition of specific enzymes that are involved in cell division. Enzymes such as aurora kinase A (AURKA) are essential for the regulation of mitosis [5]. Leukaemia is one of the malignancies that are associated with AURKA overexpression, which results in uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumour formation.

Blocking the activity of aurora kinase A is a promising new treatment for leukemia [6]. The disease's progression may be slowed by inhibiting the rapid division of leukemic cells by suppressing this kinase [7]. Computational screening methods have been employed in recent research to identify potential candidates from the natural compound library that may function as aurora kinase A inhibitors [8, 9]. Researchers have devised a multi-step in silico method to expedite the discovery of effective remedies for leukaemia. This method rapidly evaluates a large number of chemicals [10]. In general, the utilisation of natural chemical inhibitors to target aurora kinase A is a promising advancement in the fight against leukaemia, indicating the potential for future treatments that are both more effective and less detrimental.

Current Aurora A kinase inhibitors, while effective, often suffer from off-target toxicity, limited selectivity, and the emergence of drug resistance, which hampers their long-term therapeutic success. These challenges highlight the urgent need for alternative scaffolds with improved safety and efficacy profiles. Natural compounds offer a promising solution due to their intrinsic structural diversity, evolutionary optimization for biological activity, and generally lower toxicity compared to synthetic molecules [11]. In this study, we hypothesize that natural compounds may exhibit high specificity for Aurora A kinase along with favorable ADMET characteristics, making them suitable candidates for targeted therapy. Unlike previous computational approaches (such as Siudem et al., 2023), this work employs a comprehensive in silico strategy that integrates machine learning-based QSAR modeling, molecular docking, MM-GBSA binding energy estimation, molecular dynamics simulations, and DFT analysis to systematically identify and validate potential Aurora A kinase inhibitors from a natural compound library [8].

Aurora kinases (Aurora kinase A) have been identified as a validated target protein in leukaemia malignancies, including acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukamia (ALL). Due to the overexpression of these kinases, which are essential for the modulation of the cell cycle, leukaemia induces chromosomal instability, uncontrolled proliferation, and tumour growth [12]. This study employed an in silico approach to identify the binders of aurora kinase A. A comparable analysis was conducted. The objective of this study was to utilise computational methods to specifically target the aurora kinase A. The investigation necessitated the creation of a machine learning methodology to evaluate 3093 distinct natural compounds. The compounds that were selected through machine learning (ML)-based screening underwent additional molecular docking analysis. Furthermore, the following were conducted to determine the most effective compound: Root mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Hydrogen Bonds (H-bonds), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Free Energy Landscape (FEL), and Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA). The investigation led to the identification of the promising binder for aurora kinase A. In order to identify prospective inhibitory compounds, this investigation employed computational methodologies such as molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and binding free energy calculations. This exhaustive approach, which prioritises binding free energy and structural stability, establishes a standard for computational drug discovery pipelines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein structure selection

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) was searched to find the structure of aurora kinase A [13]. The PDB file was downloaded after selecting the PDB ID 2X6D [14]. The 285 residue protein is a homomer with theco-crystallized6-bromo-7-[4-(4-chlorobenzyl) piperazin-1-yl]-2-[4-(morpholin-4-ylmethyl)phenyl]-3h-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (X6D). Additionally, in following analysis, X6D was used as a control. The Aurora A kinase structure (PDB ID: 2X6D) was selected for this study due to its reliable resolution of 2.80 Å, absence of mutations, and the presence of a co-crystallized inhibitor, which provided a well-defined active site suitable for docking studies. Although a few residues were missing, they were located outside the binding pocket and thus were not modeled, as they did not influence ligand interaction. Additionally, explicit protonation of ionizable residues, was not performed, as the standard protonation state at physiological pH was retained throughout the docking and simulation processes. During docking, the protein structure was analysed for residues in the binding sites and additional structural preparation was carried out.

Compound library

A screening method was carried out using Lipinski's Rule of Five (ROF) to evaluate the pharmacokinetics and drug-likeness of the compounds. The potential of a compound as an orally active medication can be assessed using Lipinski's ROF, a metric that is generally acknowledged [15, 16]. Important molecular characteristics included molecular weight ≤ 500 daltons, LogP (octanol-water partition coefficient) ≤ 5, hydrogen bond donors ≤ 5, and hydrogen bond acceptors ≤ 10. Drug candidate with acceptable physiochemical properties were guaranteed by these metrics. Lipinski's Rule of Five emphasises the significance of identifying molecules with suitable pharmacokinetic parameters for optimisation and additional evaluation by eliminating compounds that did not meet al. l requirements.

ML-based QSAR

The quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) technique was used in drug development to demonstrate adaptability and accuracy. While QSAR has relied on standard machine learning methods, new technologies like deep learning and big data have purposefully improved the processing of unstructured data, allowing QSAR to reach its full potential [17]. In this study, six regression models were used for QSAR: decision tree, random forest, gradient boosting, support vector regression, and bayesian ridge.

Further, known Aurora kinase A inhibitors were retrieved from the CHEMBL database, which is available at (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/), in order to build the QSAR model [18]. We used the CHEMBL database to look for “Serine/Threonine-protein kinase Aurora A” and then we extracted the compounds from the target that had the most compounds with known IC50 values. In this case, the compounds that had IC50 measured in nM were selected. Antibiotics are classified according to their IC50, which is the lowest amount (measured in nM). The RDkit algorithms were used to determine the compound characteristics, and then the QSAR model was developed [19]. Here, ML models were formed to predict IC50 using the morgan descriptor. Morgan fingerprints were selected as the descriptors for this study due to their proven ability to capture essential structural features of compounds, particularly in large-scale QSAR modeling. These fingerprints are based on the extended connectivity (ECFP) algorithm, which encodes information about atom pairs and their environments. Morgan fingerprints are widely recognized for their high predictive power, especially in predicting bioactivity, as they encode both local and global molecular interactions in a compact format. Compared to other descriptors like MACCS and ECFP, Morgan fingerprints are computationally efficient and have shown superior performance in many virtual screening and QSAR studies [20].

Finally, 70% of the compounds were used for model training, whilst 30% were made use of as test compounds. During the process of training the machine learning model, the data used to evaluate the model (test set) was kept separate from the data used to train the model. In addition, the models were tested for validity by calculating their coefficient of determination (R2) and using the model with the greatest value for screening. The model fits the data well if the R2 value is high, which indicates a strong link between the actual and anticipated values. Subsequently, the optimal QSAR models that had been developed were used to calculate the bioactivity (IC50) of the natural chemicals. The compounds that demonstrated greater activity relative to the control, X6D, were selected for further screening utilising molecular docking.

Molecular docking

The compound library preparation process began with a search of the Selleckchem database for the natural compounds (https://www.selleckchem.com/screening/natural-product-library.html). The retrieved compounds were later converted into SMILES for PubChem CID using the “PubChem Identifier Exchange Service” [21]. By removing duplicate entries from both conversion processes, distinct CIDs were obtained. Then, the CIDs corresponding to the 3D-SDF structures were acquired using the PubChem API. The other 2D-SDF structures were gathered and transformed into 3D-SDF in the meantime. After that, the 3D-SDF files were optimized using the MMFF94 force field, and Open-babel was used to convert these to PDBQT [22]. The addition of hydrogen was also done by open-Babel programme. Using AutodockTools [23], grid box was created around native ligand residues. Specific docking parameters were set to achieve optimal results. In this context docking was run at an exhaustiveness of 100, with an energy range of 4 kcal/mol, and predicted 10 ligand-protein interaction poses. Molecular docking was carried out using AutoDock Vina [24],

PSICHIC

The PSICHIC (Physicochemical graph neural network) model represents a cutting-edge methodology for drug development, demonstrating exceptional efficacy in forecasting protein-ligand interactions [25]. This encompasses AURKA inhibitors, utilised in the treatment of leukaemia. Its interpretable fingerprints, which identify essential ligand and protein residues in binding interactions, are among its most significant advantages. These fingerprints enhance our comprehension of drug specificity by elucidating selectivity determinants and mechanisms governing protein-ligand interactions. According to binding affinity prediction, PSICHIC matches or surpasses state-of-the-art structure-based methods, despite being trained just on sequence-based protein-ligand pairings, unlike conventional structure-based methods that rely on explicit 3D structural data. The prediction accuracy of 0.96 for functional effects is remarkable, and the information it offers regarding a drug's possible impact on the body are vital. An efficient and effective method for in silico drug screening, the model predicts binding affinity and categorises compounds as potential antagonists. The best compounds were selected for further screening.

DFT

Among the several approaches to ab initio calculations of atomic, molecular, crystal, surface, and interaction properties, density functional theory (DFT) ranks high [26]. One popular theoretical tool in quantum chemistry is density-functional theory (DFT). An immediate method for the development of novel pharmaceuticals and the improvement of current ones [27]. Using a Python tool, we determined the DFT of every top ligand. The total formal charge and the electronic structure studies of a molecule from the PDB file was calculated using RDKit and Python-based simulation of chemistry framework (PySCF) [28]. A hybrid functional that combines an exact Hartree-Fock exchange with a DFT exchange-correlation term was employed to analyse the entire geometry. This functional is the Becke, 3-parameter Lee-Yang-Parr correlation (B3LYP) functional [29] with the basic set 6-31G* basis set[30]. B3LYP/6-31G* has been previously reported as a reliable method for evaluating molecular orbitals and reactivity descriptors in drug-like molecules and natural products (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theochem.2005.04.023, https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202205735, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35933-8). Although functionals like M06-2X with larger basis sets (e. g., 6-311++G**) may offer improved accuracy for noncovalent interactions, they are computationally intensive and more suitable for small systems or final validation steps. Therefore, B3LYP/6-31G* was selected for its efficiency in screening a large number of compounds in this study. Further, the DFT calculations using the B3LYP functional was used to compute the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) energy, DFT energy, SCF convergence, HOMO, LUMO energies, and dipole moment magnitude. The top compounds based on the calculation were further used for the Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation.

ADMET

Further the physiochemical properties of the selected compounds were predicted using ADMET. The physicochemical and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties computed using SwissADME [31] and the ProTox-3.0 server [32].

MD simulation

The molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the protein-ligand complex were performed using the Gromacs 2022.4 package [33]. The top docked pose was used in the 100 ns MD simulation. The topology of the molecules was defined using CHARMM36 [34] force field parameters, which were subsequently assigned to both the ligands and protein. The CGneFF [35] server was used to develop the topologies and force-field parameters of the hit compound and control inhibitor. The penalty scores shown in supplementary table S7 from CGenFF indicate that the ligand parameterization with CHARMM36 is reasonable for most compounds. A charge penalty under 10 and param penalty under 60 are typically considered acceptable for simulations using CHARMM36, suggesting that the force field is well-suited for these ligands. Afterward, the Ewald Particle Mesh approach was employed to compute the electrostatic force over a distance [36]. The system was placed into the solvation box and hydrated using the TIP3P model. Following that, Na+and Cl-ions were added to achieve the neutralisation [37]. The system underwent 50,000 reduction steps using the steepest descent (SD) method to remove steric clashes. Later, the LINCS algorithm [38] was employed to constrain the bonds, achieving stability in the system. In addition, the entire system was raised to a temperature of 310 K using a time step of 2 fs for a simulation time of 100 ps in the NVT ensemble and pressure (NPT) for a duration of 1 ns each at 310 K and 1 atmosphere. Far along, the coordinates of the structure were recorded every 10 ps during the entire 100 ns (100,000 ps) during the production run. An outcome of the MD was analysed through root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) in the GROMACS to determine the conformational stability and variation. Moreover, the velocity scaling [39] approach was used as a temperature coupling to stimulate at constant temperature. Subsequently, the Parrinello-Rahman pressure coupling method was used to ensure a consistent pressure throughout the production process [40].

RESULTS

Binding site residues

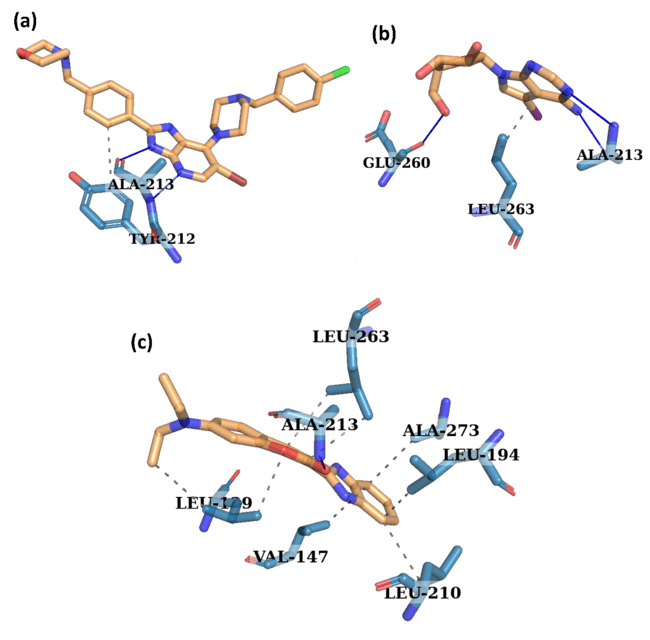

The serine/threonine kinase aurora kinase A is essential for the construction of the mitotic spindle, the maturation of the centrosome, and the alignment of the chromosomes during cell division. The overexpression of aurora kinase A has been linked to a variety of cancer types, rendering it a critical target for the development of anticancer treatments. The co-crystallized structure of 6-bromo-7-[4-(4-chlorobenzyl) piperazin-1-yl]-2-[4-(morpholin-4-ylmethyl)phenyl]-3h-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (X6D), an inhibitor, complexed with aurora kinase A was retrieved using the PDB ID: 2X6D. When this small-molecule inhibitor binds to the ATP-binding pocket of the kinase, the protein's inactive conformation is stabilised. Structural investigations of the binding interaction have identified significant residues that enhance ligand affinity through hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic forces. As shown in fig. 1, the binding site residues are Lys143, Phe144, Lys141, Gly142, Gly140, Gly145, Asn146, Arg137, Leu164, Leu139, Val147, Val163, Leu164, Arg137, Asp274, Glu260, Ala273, Arg220, Thr217, Asp274, Ala160, Ala273, Leu210, Tyr212, Leu194, Pro214, Ala213, Leu263, Leu215, and Gly216 which are found at the binding pocket of the known inhibitor X6D. Here, Ala213 showed hydrogen bond with the inhibitor X6D and the rest showed hydrophobic contacts. The co-crystallized structure elucidates the molecular mechanisms underlying the inhibition of aurora kinase A, providing a basis for designing of specific kinase inhibitors that are both safe and efficacious for therapeutic applications.

Fig. 1: Binding site residues of aurora kinase A (PDB ID: 2X6D) surrounding the inhibitor 6-bromo-7-[4-(4-chlorobenzyl)piperazin-1-yl]-2-[4-(morpholin-4-ylmethyl)phenyl]-3h-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (X6D) with distance 6 Å, (a) 3D conformation (b) Interaction (Hydrogen bonds-green and Hydrophobic contacts-black)_(c) Binding site residues of binding pocket

Virtual screening based on drug-likeness

The Selleckchem natural chemical library was systematically screened through to identify potential drug-like molecules for Aurora Kinase A inhibition, starting with 3,093 natural compounds. Natural compounds were prioritized due to their structural diversity, which enhances the likelihood of novel bioactivity, and their reduced toxicity profiles, making them promising candidates for drug development. Additionally, many have evolved to interact with biological targets effectively. As a result of the removal of duplicate entries and invalid values, the dataset was initially refined to 2,894 unique compounds. Lipinski's Rule of Five, which evaluates molecular weight, hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, lipophilicity (logP), and other pharmacokinetic parameters, was used to further screen the compounds to ensure that they possessed drug-like qualities. Lipinski's Rule of Five (Ro5) is an effective approach for determining a compound's oral bioavailability [41]. In the majority of cases, an orally active substance must satisfy at least one of the following criteria: Molecular weight: ≤ 500 Daltons, logP (Octanol-Water Partition Coefficient): ≤ 5, hydrogen bond donors: ≤ 5 (sum of OH and NH groups), hydrogen bond acceptors: ≤ 10 (sum of O and N atoms).

Inadequate absorption or penetration may be indicated by deviations from these criteria, which are used to assess the medicinal-likeness of substances. Ro5 is utilised as a filter in virtual screening to identify pharmaceuticals that possess favourable pharmacokinetic properties. In a similar investigation, Nogara et al. (2015) utilised the ZINC database and Ro5 to identify acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, thereby reducing the number of potential candidates before conducting a molecular docking study [42]. Similar to this, Daisy et al. (2011) implemented ligand-based virtual screening to investigate the potential antidiabetic properties of natural substances [43]. The selection of compounds for further investigation was facilitated by the use of Ro5 to determine the degree of similarity between the compounds and pharmaceuticals.

The number of compounds with promising physicochemical properties for use in drug development was further decreased by this screening step to 2,045 as shown in supplementary file S1. Among the 2,045 drug-like compounds that passed Lipinski’s Rule of Five filtering, the mean molecular weight was 350.65 Da, and the mean logP was 1.03, indicating a favorable balance between size and lipophilicity. The average number of hydrogen bond donors was 3.06, and acceptors was 5.9, supporting their potential for oral bioavailability and permeability. In order to evaluate the compounds' potential as inhibitors of Aurora Kinase A, additional computational study was performed on them. This study included further ML-based QSAR screening and molecular docking.

QSAR and machine learning-based screening

The study enhanced the identification of potent aurora kinase a inhibitors by a machine learning-based qsar (quantitative structure-activity relationship) screening method. Upon querying the chembl database for the aurora a protein Serine/Threonine-protein kinase, 3,787 compounds with IC50 values (indicative of inhibitory activity) were identified in the ChEMBL4722 dataset. Data preparation techniques were implemented to ensure that machine learning models received high-quality data. The dataset was streamlined to 3,563 compounds by excluding null values from the SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings and standard IC50 values. A curated dataset of 2,974 compounds was obtained for model training following additional filtering based on reported nanomolar (nM) IC50 values. Ultimately, 70% of the compounds were employed to train the model, while 30% were employed as test compounds. Additionally, we employed the models with the highest coefficients of determination (R2) to filter them and verify their validity. A high R2 value (0.68) indicates that the model is well-suited to the data. This is supported by a strong correlation between the actual and projected values as listed in table 1. Although other models, including Linear Regression (R² = –9.41), were evaluated, only the Random Forest model (R² = 0.68) was used for compound selection due to its superior predictive performance. The validation metrics for the Random Forest model are provided in the supplementary table S6, which includes R², Q², RMSE (Root mean Squared Error), MSE (mean Squared Error), and MAE (mean Absolute Error) for each fold of the 3-fold cross-validation. These metrics demonstrate the model’s ability to generalize, with the R² values ranging from 0.67 to 0.69 and corresponding Q² values between 0.65 and 0.67, confirming robust predictive performance. The RMSE and MAE values further emphasize the model’s accuracy in predicting bioactivity (IC₅₀) for the test compounds. The bioactivity (IC50) of the 2,045 natural compounds obtained from the previous screening method was subsequently determined by employing the most effective QSAR model (Random Forest). The compounds that exhibited greater activity than the control (X6D), were selected for further analysis as shown in supplementary file S2.

The Random Forest model effectively prioritized inhibitor candidates, and since a large number of compounds showed better predicted activity than the control (X6D), all 2,045 were advanced to molecular docking for further validation. This concept combines ligand-based and data-driven approaches to enhance the efficiency of identifying compounds that inhibit aurora kinase A.

Table 1: The correlation coefficient models used for QSAR screening

| Model | R-squared | mean squared error | Correlation value |

| Bayesian Ridge | 0.59 | 0.01 | 0.77 |

| Linear Regression | -9.41 | 2.35 | 0.03 |

| Random Forest Regressor | 0.68 | 0.007 | 0.83 |

| Decision Tree Regressor | 0.52 | 0.01 | 0.76 |

| SVR | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.77 |

Molecular docking against aurora a kinase

The binding affinity of the compounds that were screened against aurora a kinase was evaluated using molecular docking. The aurora kinase A was docked with inhibitor 6-bromo-7-[4-(4-chlorobenzyl) piperazin-1-yl]-2-[4-(morpholin-4-ylmethyl) phenyl]-3h-imidazo [4,5-b]pyridine (X6D) and aligned with the crystal structure (PDB ID: 2X6D) as shown in supplementary fig. S1. It was observed that the RMSD was 0.00 Å, thus validating the docking process. The objective was to identify inhibitors that exhibited robust interactions. Initially, 2,045 compounds were selected for docking based on the results of the previous screening and QSAR analysis. In order to enhance precision, duplicate compound IDs (CIDs) were removed from the dataset after 3D structures were obtained from which resulted in 1,653 compounds. These 1,634 molecules were docked to the active site of the aurora a kinase as shown in fig. 1 using molecular docking process. The docking findings was analysed in accordance with docking score (binding energy), with a criterion of-6 kcal/mol, to identify an inhibitor that demonstrated potential. Finally, 683 compounds were selected for post-docking evaluation due to their compliance with this prerequisite. The optimal docking energy (binding energy) of active pharmaceuticals is-6 kcal/mol, according to previous studies [44–46]. In addition, previous studies have employed docking scores below-6 kcal/mol as a threshold for the identification of potential binders, as this indicates a high binding affinity [47]. According to supplementary file S3, 683 compounds exhibit a high affinity for protein binding, as evidenced by docking scores that are less than-6 kcal/mol. The 683 natural compounds were subsequently employed for screening.

PSICHIC

The PSICHIC (Physicochemical graph neural network) method was implemented to predict binding affinity in order to further refine the pool of potential aurora a kinase inhibitors. While docking scores provide a structural estimate of binding affinity, they are limited by rigid receptor assumptions and scoring function biases. PSICHIC was employed post-docking to incorporate data-driven predictions of binding affinity based on learned physicochemical patterns, offering an orthogonal and complementary evaluation. This integration of structure-based and machine learning-based methods improves confidence in the prioritization of lead compounds. As a reference point for compound selection, the control compound used for comparison had a projected binding affinity of 6.9. All 683 compounds that secured the top scores in the molecular docking phase had their predicted binding affinities evaluated using the PSICHIC platform. In comparison to the control, 34 of the molecules found showed more stable and strong interactions (>6.9) with aurora a kinase supplementary file S4 provides these selected compounds with their binding affinity. Following this, additional analysis was conducted on these 34 compounds to determine their viability as lead candidates.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) computations were conducted to further improve and assess the electronic characteristics of the control compound and the top-scoring 34 compounds. The electronic distribution, reactivity, and stability of molecules can be better understood by DFT evaluations of dipole moment, HOMO and LUMO energies, and other quantum chemical descriptors. The DFT calculations were listed in supplementary file S5. After conducting DFT calculations on all 34 compounds and the control, the four compounds with the best electronic characteristics and stability were selected to undergo molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

A narrower HOMO–LUMO gap typically indicates higher electrophilicity and chemical reactivity, which may facilitate more favorable interactions with the active site of Aurora A kinase. Based on their DFT features as shown in table 2, PubChem CIDs: 94381 (Coumarin 7), 135402019 (Hypoxanthine), 1830 (7-Iodo-7-deaza-D-guanosine), and 2673 (Cefradin) were selected for additional investigation. The lowest HOMO-LUMO gap (-0.1580/-0.1311 eV) and excellent electronic stability with a moderate dipole moment (2.64 D) were observed by 94381, which may indicate high reactivity and possible bioactivity, among the compounds. 1830 emerges as a viable candidate for further examination owing to its stable equilibrium (-7781.95 Ha), moderate dipole moment (2.80 D), and minimal HOMO-LUMO gap (-0.1054/-0.0775 eV). 135402019 was selected for its possible stability and interaction with the protein because of its low energy (-890.26 Ha), moderate dipole moment (4.38 D), and small HOMO-LUMO gap (-0.1055/-0.0918 eV).

Despite compound 2673 exhibiting an atypically high dipole moment (426.86 D), which may result from structural asymmetry or limitations in conformational optimization, it was retained for comparative analysis. Biologically, such a high dipole moment implies significant charge separation, potentially reducing membrane permeability and compromising binding orientation within the aurora a active site. Furthermore, its positive HOMO–LUMO gap (0.0411/0.0611 eV) suggests low electrophilicity and limited chemical reactivity, making it less likely to form stable or meaningful interactions with the target kinase. All selected compounds successfully converged in self-consistent field (SCF) calculations, affirming their electronic stability and rendering them robust candidates for subsequent molecular dynamics simulations and ADMET evaluations.

Table 2: DFT calculation including energy, HOMO energy, LUMO energy, and dipole magnitude of the top four compounds

| PubChem ID | Energy | HOMO energy | LUMO energy | Dipole magnitude | Charge | Spin | Num electrons | SCF converged |

| 1830 | -7781.95 | -0.10 | -0.07 | 2.80 | 0 | 0 | 184 | TRUE |

| 2673 | -1455.97 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 426.86 | -1 | 0 | 170 | TRUE |

| 94381 | -1062.44 | -0.15 | -0.13 | 2.64 | 0 | 0 | 158 | TRUE |

| 135402019 | -890.263 | -0.10 | -0.09 | 4.38 | 0 | 1 | 123 | TRUE |

ADMET profiling

The top four compounds (94381, 135402019, 1830, and 2673) selected from DFT analysis were assessed for their pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and drug-likeness using ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling. These characteristics can be used to evaluate the compounds' potential for further preclinical development. Table 3 listed the ADMET properties of the four selected compounds. The molecular weights of all the four compounds were below 350 Da, and they both comply with the drug-likeness standard. All four of these substances are well-suited for oral administration due to their high gastrointestinal (GI) absorption rates. The bioavailability of compounds that are highly soluble compared to the control. 1830, 2673, and 94381 fall within the ideal iLOGP (integrative octanol–water partition coefficient) range (1-3), making them suitable drug candidates with balanced solubility and permeability. According to the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), the Hazard Communication Standard (HCS) categorizes compounds based on their oral LD₅₀ values into six toxicity classes: Class I (LD₅₀ ≤ 5 mg/kg, fatal if swallowed), Class II (5<LD₅₀ ≤ 50, fatal), Class III (50<LD₅₀ ≤ 300, toxic), Class IV (300<LD₅₀ ≤ 2000, harmful), Class V (2000<LD₅₀ ≤ 5000, may be harmful), and Class VI (LD₅₀>5000, non-toxic). Based on this classification, the compounds 2673, 94381, and 135402019 were assigned to toxicity classes IV and V, which are considered acceptable for early drug development. In terms of synthetic accessibility (SA), 94381 (SA: 3.19) and 135402019 (SA: 3.51) had the lowest scores, indicating they are easier to synthesize. Since SA scores ≤ 4 are generally preferred in early drug discovery, these compounds are considered favorable for lead optimization and preclinical advancement. To eliminate false positives in early screening, PAINS (Pan-assay interference compounds) filters were applied using PAINS-1, PAINS-2, and PAINS-3 substructure filters via the Swiss ADME platform. These filters help identify compounds with problematic substructures known to interfere non-specifically in biological assays. All compounds successfully passed in vitro and in vivo investigations without eliciting a PAINS (Pan Assay Interference Compounds) alarm.

When compared to the clinical Aurora A inhibitor Alisertib (supplementary table S0), both 1830 and 94381 demonstrated lower molecular weights, better solubility, higher GI absorption, and more optimal iLOGP values[48]. Alisertib, despite being clinically used, exhibits low oral absorption, poor solubility, and a higher synthetic accessibility score (4.12), which may limit its formulation and delivery. In contrast, 1830 and 94381 combine favorable pharmacokinetic properties with ease of synthesis, supporting their potential as next-generation Aurora A inhibitors with improved drug ability. These two candidates were thus prioritized for further molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and binding free energy evaluations to confirm their stability and interaction profiles.

The results of this study indicate that the four molecules exhibit drug-like characteristics, particularly in terms of its potential for being absorbed orally. Based on these findings, further research into the hit compound would warrant drug-like behaviour against the disease. The binding stability and interaction characteristics of these compound bound with Aurora A kinase was further evaluated through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of top three compounds

RMSD

Fig. 2 shows the results of the Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations using Root mean Square Deviation (RMSD) analysis. This study illustrates on the structural stability and binding interactions of the compounds that were selected with Aurora A kinase. The structural stability of aurora A kinase (Cα atoms) when bound to the compounds (94381, 135402019, 1830, and 2673) throughout 100 ns of MD simulation is depicted in the fig. 2(a). The protein-ligand complex of control has the RMSD in the range 0.3-0.4 nm with few fluctuations, indicating slight structural aberrations. It was observed that the protein when bound to 1830, demonstrates strong stability with RMSD values varying about 0.2-0.3 nm. An extremely stable protein-ligand interaction is indicated by 2673 lowest RMSD of in the range 0.15 to 0. 2 nm. Tight binding with minimal structural variation is shown by minimal fluctuations. Compound 94381 exhibited considerable stability with RMSD values ranging from 0.2-0.25 nm. Similarly, both 2673 and 135402019 exhibits stable RMSD in the range 0.15 nm to 0.2 nm. Overall, 2673 and 135402019 exhibit the most stable binding associations with aurora a kinase due to their low RMSD values and minimal variations.

During 100 ns of MD simulation, the stability of the aurora A kinase binding site and the ligands (1830, 2673, 94381, and 135402019) as well as the control molecule are depicted in the RMSD plot in fig. 2(b). There is a high RMSD for 2673 and 135402019. It was observed that these ligands departed from the binding site as they show substantial fluctuation of RMSD in the range 10-25 nm range with time. This indicated that the ligand dissociated from the active site and their binding stability is weak. The RMSD is low for 1830 and 94381. The RMSD of these ligands remains modest in the range 0.2-0.5 nm all through the 100 ns MD run. Their consistent RMSD values, in contrast to those of 2673 and 135402019, show improved binding affinity and stability, suggesting robust retention in the binding pocket.

The control ligand exhibits elevated RMSD values 0.4–0.5 nm, signifying fluctuations and potential rearrangement within the binding pocket as shown in fig. 2(c). The 1830 and 94381 demonstrate reduced and consistent RMSD. Both ligands (1830 and 94381) exhibit RMSD values in the range between 0.1 and 0.3 nm, with slight variations. The low RMSD values suggest robust retention in the binding site, indicating elevated binding stability. The two most promising Aurora A kinase inhibitors, 1830 and 94381, show the best binding stability. 2673 and 135402019 are instable since their high RMSD values suggest that they left the binding site, thus they were not used for further analysis. The compounds 2673 and 135402019, both showed ligand dissociation during the 100 ns MD simulation, evidenced by large RMSD fluctuations ranging from 10 to 25 nm. Due to this lack of binding stability, these compounds were excluded from further binding free energy analysis and prioritization.

Table 3: ADMET properties of the three compounds and the control (X6D)

| Properties | Control (X6D) | 1830 | 2673 | 94381 | 135402019 |

| MW | 581.93 | 392.15 | 349.4 | 333.38 | 252.23 |

| Rotatable bonds | 6 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| H-bond acceptors | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| H-bond donors | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| MR | 162.76 | 77.6 | 93.34 | 101.39 | 59.93 |

| TPSA | 60.52 | 126.65 | 138.03 | 62.13 | 113.26 |

| iLOGP | 4.68 | 1.57 | 1.53 | 2.46 | 0.45 |

| Solubility Class | Poorly soluble | Soluble | Very soluble | Moderately soluble | Very soluble |

| GI absorption | High | High | High | High | High |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| PAINS alerts | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Leadlikeness violations | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Synthetic Accessibility | 3.73 | 4 | 4.84 | 3.19 | 3.51 |

| Toxicity Class | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

Fig. 2: Post MD simulation analysis (a) RMSD of the protein Cα atoms when bound to the compounds (b) RMSD of the ligands 1830, 2673, 94381 and 135402019 along with control (c) RMSD of the ligands control (X6D), 1830 and 94381

Further triplicates were performed for control (X6D), 1830 and 94381. Supplementary fig. S2 shows the RMSD of the protein during the 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation for three replicate runs of the control (X6D), 1830, and 94381 compounds. The RMSD profiles for all three compounds (shown in red, black, and green for Runs 1, 2, and 3, respectively) demonstrate that the systems reached stable equilibration after an initial fluctuation phase, with minimal variation in RMSD values across runs. This stability suggests that the simulations are reliable and reproducible, with consistent structural behavior observed in all replicate runs, supporting the robustness of the binding and ligand-protein interactions for these compounds. Supplementary fig. S3 shows the RMSD of the ligand during the 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations for three replicate runs of the control (X6D), 1830, and 94381 compounds. The RMSD profiles for all three compounds (colored in red, black, and green for Runs 1, 2, and 3, respectively) demonstrate stable binding throughout the simulation, with fluctuations indicating ligand accommodation within the protein binding site. The stability of the RMSD in all three runs further supports the consistency and reproducibility of the ligand-protein interactions, suggesting reliable binding behavior across multiple simulation replicates.

Energy and pressure stability

Additionally, energy stability plots were analysed for the control (X6D) and the selected compounds (1830, 2673, 94381, and 135402019) to assess the equilibration of the system during the 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations. These plots, shown in supplementary fig. 4 (a-e), demonstrate that the systems reached energy stabilization after an initial equilibration phase, with minimal fluctuations observed after 20 ns, confirming the convergence of the simulations. This suggests that the systems were well-equilibrated before further analysis, ensuring the reliability of the subsequent molecular interaction studies.

Further, pressure stability plots are provided for the control (X6D) and the selected compounds (1830, 2673, 94381, and 135402019) to assess the stability of the pressure during the 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations. These plots, shown in supplementary fig. S5 (a-e), demonstrate that the pressure remained stable throughout the simulation, with minor fluctuations around the desired target value, indicating proper functioning of the barostat and system equilibration. The stability in pressure further supports the convergence of the simulations and the reliability of the data for subsequent analysis.

RMSF

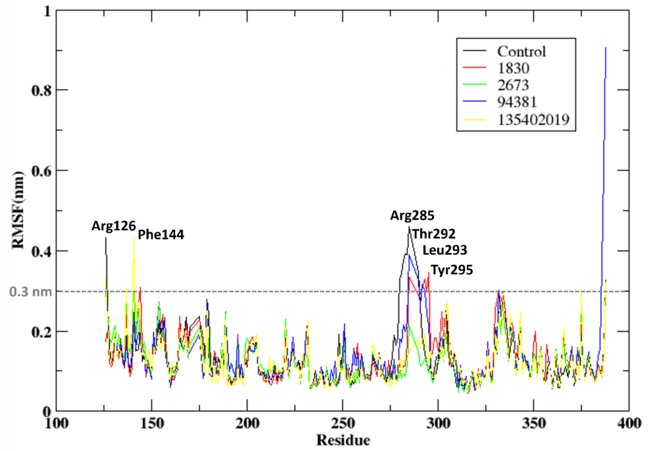

The Root mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis elucidates the residue-level flexibility of Aurora A kinase in complex with the control ligand (X6D) and the compounds 1830 and 94381. Fig. 3 showed the RMSF of the residues of the protein when bound to the compounds and the control. The RMSF values were consistently low, indicating that ligand binding stabilised the protein structure. However, specific regions demonstrated higher flexibility, signifying localised adaptability. The control ligand (X6D) exhibited an RMSF exceeding 0.3 nm for residues Arg126 and Ser388 (terminal residues), which is anticipated due to their inherent mobility, while residues His280–Cys290 fluctuated between 0.3 and 0.4 nm, indicating a flexible loop region. Compound 1830 elicited increased fluctuations in residues Phe144, Arg285, Thr292, Leu293, Tyr295, Asn332, and Ser388, likely attributable to ligand-induced conformational changes. Likewise, 94381 demonstrated elevated RMSF in residues Arg126, Arg285, Cys290, Thr292, Asn332, and Asn386, coinciding with critical flexible areas, while exhibiting reduced fluctuations compared to 1830. The findings indicate that both compounds stabilise the protein.

Fig. 3: RMSD of the protein when bound to the compounds 1830, 2673, 94381 and 135402019 along with the control compound (X6D)

Conformation

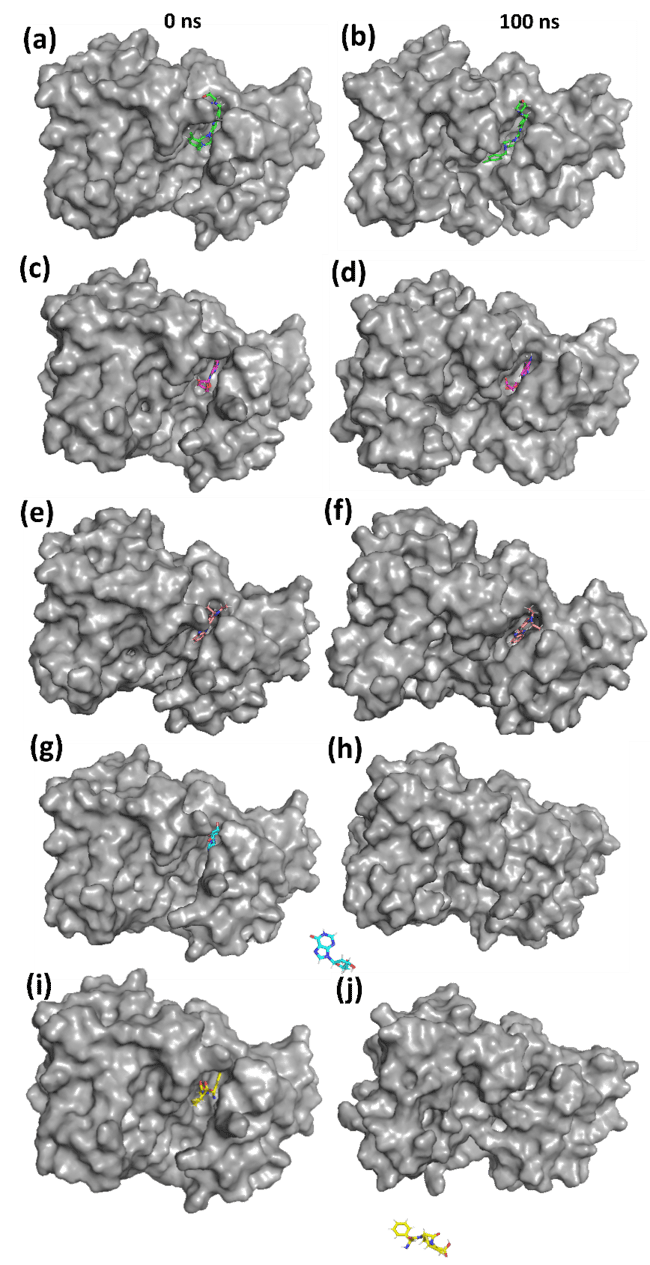

Fig. 4 depicts the three-dimensional conformations of protein-ligand complexes at 0 ns (initial binding) and 100 ns (post-molecular dynamics simulation) for the control ligand (X6D), 1830, 2673, 94381, and 135402019. The structural insights derived from the MD simulation elucidate ligand stability, retention within the binding site, and potential ligand displacement.

The control ligand stays anchored in the active site, but modest conformational alterations are evident after 100 ns, as illustrated in fig. 4(a, b). This signifies moderate stability with a certain degree of flexibility in binding. Here, 1830 persists in the binding pocket, exhibiting minor conformational alterations depicted in fig. 4(c, d). This indicates consistent interactions during the simulation, validating its potential as a robust inhibitor. Compound 2673 departs from the active site, signifying weak binding interactions as illustrated in fig. 4(e, f). The displacement indicates that 2673 lacks robust stabilising contacts, rendering it a less viable choice for Aurora A kinase inhibition. The Compound 94381 stays tethered inside the active site, exhibiting little positional alterations as illustrated in fig. 4(g, h). The steady placement indicates robust ligand-protein interactions, affirming 94381 as a potential inhibitor. Compound 135402019 entirely exits the binding pocket, signifying inadequate retention and low binding affinity, as illustrated in fig. 4(i, j). This verifies that 135402019 is not an appropriate candidate for further evaluation.

94381 and 1830 exhibit robust binding stability, retaining their locations inside the active site. Compounds 2673 and 135402019 demonstrate poor binding and entirely dissociate from the protein binding pocket, rendering them inappropriate for further optimisation. The control ligand (X6D) remains attached but exhibits slight conformational changes, suggesting intermediate stability.

Fig. 4: 3D conformation of the protein-ligand complexes for (a, b) Control (X6D) (c, d) 1830 (e, f) 2673 (g, h) 94381 (i, j) 135402019

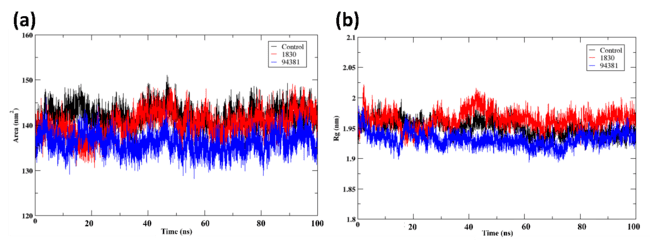

Rg and SASA

The protein-ligand complexes for control (X6D), 1830, and 94381 are shown in fig. 5 with a focus on Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) and Radius of Gyration (Rg) shown in fig. 5(a) and 5(b), respectively. In order to assess the stability of the protein when attached to various ligands, these characteristics that shed light on structural compactness and solvation dynamics are essential. A more stable and compact conformation of the protein is indicated by lower values of the Rg, an analytical measure of the overall compactness of the protein structure (fig. 5(b)). During the simulation, the most compact and stable protein structure was maintained by ligand 94381, as indicated by its lowest Rg value of approximately 1.9 nm. The moderate Rg values (1.95-2.0 nm) observed in 1830 suggest a significantly more pliable structure when contrasted with 94381. The protein shows the most flexibility when attached to the control ligand, as seen by the control (X6D) fluctuating around approximately 2.0 nm, which implies that it experiences more conformational alterations.

Analysing the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) elucidates the extent of the protein surface that is exposed to the solvent (fig. 5(a)). A higher number indicates that the structure is more extended and exposed to the solvent. It is suggested that there is improved protein-ligand interaction with little solvent exposure since 94381 consistently displays the lowest SASA in the range 130-140 nm². The slightly higher SASA values in the range 135-145 nm² observed in 1830 suggest that the protein is moderately flexible. Control (X6D) exhibits the highest SASA in the range 140–150 nm², indicating a more solvent-exposed structure, which aligns with its weaker binding stability observed in previous analyses. 94381 was observed to generate a protein conformation that is both more stable and less susceptible to solvents when the SASA is at its lowest. Although not as effective as the control ligand, the moderate SASA values of 1830 demonstrate some flexibility. Overall, 94381 demonstrates the best overall stability, as indicated by lower Rg (most compact protein) and lower SASA (least solvent exposure). Here, 1830 maintains moderate structural integrity but is slightly more flexible.

Fig. 5: Post MD analysis of the protein-ligand complexes (a)SASA (b) Radius of gyration (Rg) of the protein when bound to the ligands control (X6D), 1830, and 94381

Fig. 6: Number of the hydrogen bonds of the protein-ligand complexes for (a) control (X6D) (b) 1830, and(c) 94381

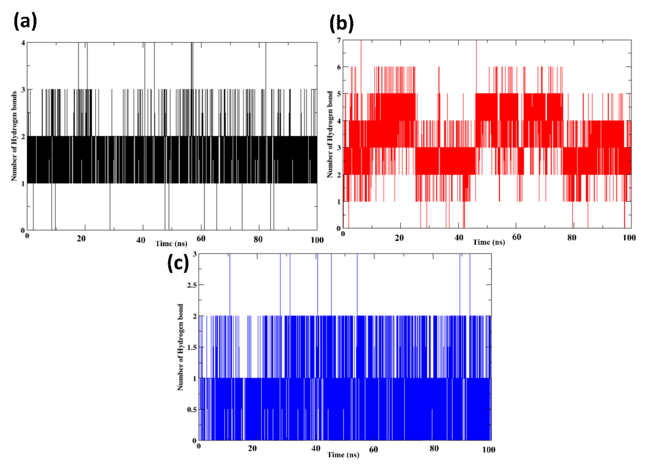

Hydrogen bonds

The protein-ligand complexes analysed for hydrogen bonding during the 100 ns MD simulation are shown in fig. 6, with a focus on Control (X6D), 1830, and 94381. A protein's binding affinity to ligands and the stability of the protein-ligand complex are both affected by hydrogen bonds, which are crucial stabilising interactions. Throughout the simulation, the control ligand tends to maintain 1-2 hydrogen bonds, with some deviations. Compared to the control ligand, 1830 consistently establishes 2-6 hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation. Stronger protein-ligand interactions and improved ligand retention are outcomes of numerous persistent hydrogen bonds. The reduced RMSD and Rg values observed are supported by higher hydrogen bond occupancy, which further strengthens the good binding stability of 1830. Hydrogen bonds are formed by 94381 throughout the simulation, and these bonds are relatively stable. Although there are fewer than 1830 of these bonds, their consistency and stability indicate that the binding stance has been well-retained. The binding strength is enhanced by the steady hydrogen bonding pattern, which is in line with decreased RMSD and compact Rg values. The maximum number of hydrogen bonds is observed in 1830, suggesting that the interaction between the protein and ligand is more stable. Even though there are fewer hydrogen bonds in 94381, the interactions are more constant, suggesting that it is strongly retained in the binding site. The control ligand (X6D) shows variations and produces the fewest hydrogen bonds, suggesting a reduced binding affinity. Because of their robust and sustained hydrogen bonding interactions, the two most promising inhibitors are 1830 and 94381. Further, supplementary table S8 lists the average hydrogen-bond counts (± SD) for the control (X6D) and the selected compounds (1830 and 94381). The control formed an average of 1.85 hydrogen bonds with a standard deviation of 0.41, while 1830 exhibited a significantly higher average of 3.38 hydrogen bonds (± 1.08), indicating stronger and more consistent interactions. 94381, on the other hand, formed 0.88 hydrogen bonds (± 0.49), reflecting weaker interactions with the protein compared to the control and 1830.

Interaction analysis

Aurora A kinase's molecular interactions with the control ligand (X6D), 1830, and 94381 are shown in fig. 7, with important residues implicated in hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions. Important interaction residues Tyr212 and Ala213 were shown by the control ligand (X6D). The ligand's moderate stability is enhanced by the hydrogen bond, it forms with Ala213. The hydrophobic interaction between Tyr212 and the ligand aids in its anchoring to the binding pocket. The amino acids Glu260, Leu263, and Ala213 interact with 1830 compounds. The ligand stabilises its location in the binding site by forming hydrogen bonds with Ala213 and Glu260. Leu263 improves the retention of the ligand by providing hydrophobic support. Increased hydrophobic interactions and stronger hydrogen bonding indicate that the binding stability is improved compared to the control ligand. Important residues that interacted with compound 94381 were Ala213, Ala273, Leu263, Leu210, Leu194, Leu109, and Val147. Ala213 secures the ligand to the active site by establishing a strong hydrogen bond. Ala213 and Glu260, located within the hinge region and catalytic cleft, are essential for ATP binding and phosphate transfer, and the hydrogen bonds formed with these residues likely mimic critical interactions seen in substrate recognition. Leu263, part of the hydrophobic back pocket, further stabilizes the ligand through non-polar contacts. These interactions with catalytically significant residues suggest that 94381 and 1830 may effectively inhibit Aurora A’s enzymatic activity by occupying functionally relevant regions of the binding pocket. Among the compounds studied, 94381 had the strongest binding stability, due to its vast network of stabilising interactions. 1830 is also a possible candidate because of its strong hydrogen bonding.

Fig. 7: Interaction analysis of the protein-ligand complexes for (a) control (X6D) (b) 1830, and (c) 94381

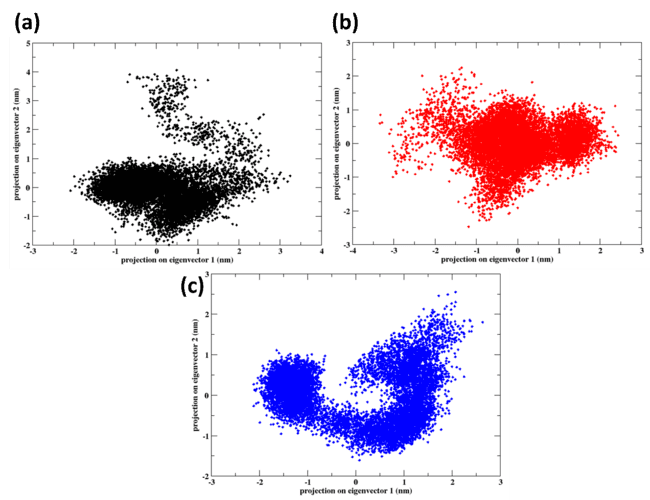

PCA

The protein-ligand complexes for Control (X6D), 1830, and 94381 are shown in fig. 8 using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). PCA enables the projection of the protein-ligand complex trajectory along the two principal eigenvectors, which encapsulate the predominant motions observed during the 100 ns MD simulation, facilitating an in-depth examination of global motion and conformational dynamics. Greater conformational flexibility and structural fluctuations are suggested by the extensively scattered and uneven distribution of the control ligand (X6D).

The distribution of 1830 is more compact than that of X6D; however, there is still a significant dispersion along both eigenvectors. Although 1830 is more effective at stabilising the protein than X6D, still showed some flexibility in terms of structure. It is a promising candidate for an inhibitor, as evidenced by the presence of robust hydrogen bond formation, consistent RMSD trends, and modest global motion. There are few conformational changes and strong structural stability in the 94381 PCA plot, which is supported by the strongly clustered distribution of the data. The stable protein-ligand association maintained by 94381 is indicated by the compact distribution along eigenvectors 1 and 2, which implies that the protein mobility is constrained. The structural alignment of 94381 is marked by low RMSD, low SASA, robust hydrogen bonding, and compact Rg, which together indicate that it is the most stable and effective inhibitor. With minor structural variations, 94381 displays the most stable conformational behaviour, suggesting strong binding.

Fig. 8: PCA of the protein-ligand complexes for (a) control (X6D) (b) 1830, and (c) 94381

FEL

Fig. 9 shows the results of the Free Energy Landscape (FEL) analysis for the protein-ligand complexes of, from left to right, Control (X6D), 1830, and 94381. Lower energy regions (red) depict more stable conformational states in the FEL, while higher energy regions (blue) depict less favourable states, as shown by Principal Component Analysis (PCA) projections.

Control Ligand (X6D) results show a diffuse energy distribution with multiple high-energy patches (14 kJ/mol) in the FEL contour plot (a) and 3D surface plot (b). Multiple local minima in the control ligand point to structurally dynamic protein structure. In both the FEL contour plot (c) and the 3D surface plot (d), compound 1830 showed that the free energy well is deeper and more compact, with a noticeable stable zone at lower energy (12.8 kJ/mol). With fewer local minima than in X6D, the conformational variability in 1830 was found to be lower. A more stable conformation for binding ligands to proteins is suggested by the presence of a dominating energy minimum. Evidence from reduced SASA, improved hydrogen bonding, and lower RMSD suggests that 1830 is more stable compared to the control.

The deep wells in the FEL plots (fig. 9(a, c, e)) correspond to the closed or bound conformations, where the protein-ligand interactions are most stable, indicating a strong binding affinity. On the other hand, the shallower basins (fig. 9(b, d, f)) represent open or unbound states, suggesting less stable or weak interactions. These basins directly correlate with the functional states of the protein, where the deep wells are associated with the active state of the protein, and the shallow regions indicate potential inactive or dissociated states.

A single dominant minimum was shown by 94381's FEL contour plot (e) and 3D surface plot (f), which indicated the most well-defined and deepest energy well at around 10 kJ/mol. The deep and compact basin indicates that 94381 forms the most stable protein-ligand complex. The robust hydrogen bonding network and the tight clustering seen in principal component analysis are in agreement with the limited conformational changes. 94381's exceptional structural stability and strong binding affinity are further supported by its most stable and lowest energy conformation. 94381 has the least conformational changes and the most stable binding because its energy well is the deepest and the most compact. 1830 is a promising alternative inhibitor because of its limited stability. The most potent inhibitor is 94381 because it keeps the lowest free energy binding mode. While 1830 has encouraging stability, its energy fluctuations are marginally greater than those of 94381.

Binding free energy

The binding free energy calculations for the protein-ligand complexes of the control ligand (X6D), 1830, and 94381 were performed using the Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) method, as shown in table 4. A number of energy components are computed in the MM/GBSA method in order to assess binding affinity. These components include the following: total binding free energy (GTOTAL), gas-phase interaction energy (GGAS), VDW, electrostatic, polar solvation, non-polar solvation, and EGB. X6D, the control ligand, is observed to participate in a greater number of hydrophobic contacts due to its exceptionally strong van der Waals interactions (-66.31 kcal/mol). While the van der Waals contributions of 1830 (-35.45 kcal/mol) and 94381 (-41.12 kcal/mol) are smaller, they contribute to stable binding. 1830 has the lowest electrostatic energy (-29.64 kcal/mol), indicating that it interacts strongly with the protein via charge. 94381 is more affected by hydrophobic contacts than electrostatic forces, as its electrostatic contribution is almost zero (0.19 kcal/mol). Moderate electrostatic interactions (-25.19 kcal/mol) are also observed in the control ligand X6D, indicating that hydrophobic and electrostatic binding are in equilibrium. The binding affinity of 94381 is enhanced since it has the lowest polar solvation penalty (18.16 kcal/mol). Because it takes more energy to desolvate before binding, the binding strength of 1830 is reduced, due to its higher solvation penalty of 42.44 kcal/mol. Due to its the control’s desolvation energy (49.47 kcal/mol), it has a low binding affinity. The strongest gas-phase interactions (-91.5 kcal/mol) are mostly caused by van der Waals forces and are observed in the control ligand (X6D). Despite having weaker gas-phase interactions, the reduced solvation penalties of 94381 (-40.93 kcal/mol) and 1830 (-65.09 kcal/mol) make up for it. The solvent environment has the least impact on 94381 because its solvation energy is the lowest at 13.00 kcal/mol. The effective binding energies of 1830 and the control ligand (X6D) are reduced due to their substantially larger solvation penalties, which are 37.59 and 42.79 kcal/mol, respectively. Control ligand (X6D) has a total binding free energy (ΔGTOTAL) of-48.71 kcal/mol. The binding free energies of 1830 (-27.50 kcal/mol) and 94381 (-27.93 kcal/mol) are comparable to X6D's, suggesting a moderate affinity for binding but lower stability.

Further per-residue decomposition was performed for the complexes. Supplementary fig. S6 shows the per-residue decomposition of MM-GBSA energy for the control (X6D), 1830, and 94381 compounds, highlighting key hotspot interactions within the protein-ligand complex. Notably, Ala213 exhibits significant stabilizing contributions with energy values of –3.83 kcal/mol (control), –3.87 kcal/mol (1830), and –3.67 kcal/mol (94381), indicating its crucial role in stabilizing ligand binding across all compounds. Similarly, Tyr212 shows a consistent negative energy contribution of –2.83 kcal/mol (control), –2.79 kcal/mol (1830), and –2.85 kcal/mol (94381), further reinforcing its importance in the interaction network. These residues are identified as key hotspots, suggesting they play a critical role in binding stability and may be potential targets for enhancing ligand affinity.

Fig. 9: FEL of the protein-ligand complexes for (a, b) control (X6D) (c, d) 1830, and (e, f) 94381

Table 4: Binding free energy of the protein-ligand complexes from MM/GBSA analysis

| Energy components | Control | 1830 | 94381 |

| ΔVDWAALS | -66.31 | -35.45 | -41.12 |

| ΔEEL | -25.19 | -29.64 | 0.19 |

| ΔEGB | 49.47 | 42.44 | 18.16 |

| ΔESURF | -6.68 | -4.85 | -5.16 |

| ΔGGAS | -91.5 | -65.09 | -40.93 |

| ΔGSOLV | 42.79 | 37.59 | 13 |

| ΔTOTAL | -48.71 | -27.5 | -27.93 |

DISCUSSION

Aurora kinase A is a critical therapeutic target in leukaemia and other malignancies, where it is implicated in the regulation of the cell cycle and mitotic progression [49]. In specific types of leukaemia, such as acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), researchers have demonstrated that aurora kinase inhibitors can efficiently halt the cell cycle and induce the death of leukemic blasts. According to previous study compound 7c has been demonstrated to inhibit the growth of certain cancer cell lines, such as HL-60, MCF-7, HeLa, and HCT-116, with IC50 values ranging from 0.335 to 2.75 μM [50]. This particular inhibition was observed during the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. The structural basis for 7c's efficacy against aurora kinase A was established through molecular docking, which established a substantial binding affinity of the compound within the ATP-binding pocket of the Aurora A kinase.

The 6-bromo-7-[4-(4-chlorobenzyl)piperazin-1-yl]-2-[4-(morpholin-4-ylmethyl)phenyl]-3h-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (X6D) co-crystallized with aurora kinase A, has been employed as a reference standard in numerous drug development studies, including those that assessed new aurora kinase A inhibitors [51, 52]. The therapeutic potential of aurora kinase A inhibition is further supported by the efficacy of X6D, a well-studied Aurora kinase inhibitor, in inducing mitotic arrest and mortality in leukaemia cells [14].

The robust binding interactions and ability to reduce lymphoblast proliferation in ALL models have both been used to demonstrate the effectiveness of X6D as an inhibitor in other studies. In the same vein, numerous other studies employed VX-680 as a reference standard for drug development [52–55]. Aurora A inhibitors are extremely beneficial in the treatment of AML and ALL due to their capacity to disrupt mitotic regulation. Leukaemia cells are selectively destroyed by this perturbation, while normal cells are preserved [56].

Numerous potent inhibitors of Aurora A kinase have been identified in recent molecular docking investigations. Almilaibary (2022) discovered two novel MK8745 analogues that exhibit superior stability and binding affinity in comparison to the original [57]. This was demonstrated in a previous study. In the same vein, molecular dynamics simulations confirmed the sustained formation of complexes in response to the discovery by Siudem et al. (2023) of pepper compounds that have the capacity to inhibit Aurora A kinase [8]. In a separate investigation, previous study identified natural substances, including quercetin, kaempferol, luteolin, and rutin, as potential AURKA inhibitors [58]. These compounds exhibited robust interactions with critical residues Leu139, Glu211, and Ala213. These residues were observed in the binding site and interacting with the present investigation with 1830 and 94381.

In the present study in docking, the control compound X6D exhibited the highest binding affinity with a docking score of –11.2 kcal/mol, while compound 94381 and 1830 scored –8.6 kcal/mol and –7.0 kcal/mol, respectively. Although these are comparatively lower than the control, they still reflect favorable binding interactions. Molecular docking was initially employed to screen 1,634 drug-like compounds, resulting in the selection of 683 hits with docking scores ≤ –6.0 kcal/mol. To further minimize false positives and improve hit reliability, this study integrated DFT-based electronic property analysis and the PSICHIC (PhySIcoCHemICal graph neural network) approach for binding affinity prediction. These additional filters helped identify 1830 and 94381 as top candidates based on both docking and post-docking evaluations.

Unlike previous studies such as Siudem et al., 2023, which relied mainly on molecular docking and MD simulations, our study employed a more comprehensive computational pipeline. Starting with Lipinski’s Rule of Five and ML-based QSAR screening, we identified active compounds and refined them using PSICHIC GNN-based affinity prediction. DFT analysis of the top 34 hits evaluated electronic properties, from which four top candidates (94381, 135402019, 1830, 2673) were selected for ADMET profiling. These were further validated through MD simulations, MM/GBSA binding free energy, PCA, FEL, and interaction analysis, providing a deeper and multi-dimensional assessment of their therapeutic potential.

This present study is further substantiated by prior research, which reinforces the case for targeting Aurora kinase A as an alternative for leukaemia therapy. Two naturally occurring compounds, 94381 and 1830, were the focus of this study. These compounds demonstrated potential as Aurora A kinase inhibitors due to their high binding stability, excellent solubility, ideal drug-likeness, and synthetic feasibility. Principal component analysis (PCA) and molecular dynamics simulations revealed stable interactions with aurora A kinase during a 100 ns simulation. Molecular docking and MM-GBSA investigations validated their high binding affinity. Their potential as potent kinase inhibitors were further validated by DFT analysis, which also emphasised their advantageous attributes. Overall, these findings underscore the potential of natural compounds to serve as effective Aurora A kinase inhibitors in future research on the treatment of leukaemia.

Although this study provides a comprehensive in silico evaluation, experimental validation is currently lacking. As part of future work, the top-performing compounds, particularly 94381 and 1830, will be subjected to in vitro assays using leukemia cell lines to confirm their inhibitory activity against Aurora A kinase. Additionally, we acknowledge that the use of rigid receptor docking may introduce false negatives by not fully capturing protein flexibility; however, this limitation was mitigated by subsequent molecular dynamics simulations, which allowed for a more realistic evaluation of binding stability.

CONCLUSION

Aurora A kinase is a prospective therapeutic target for leukaemia therapy, as it is essential for the regulation of the cell cycle and the progression of tumours. In order to identify natural chemical inhibitors of Aurora A kinase, this study employed a multi-step in silico methodology that included computational screening, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, free energy calculations, and density functional theory analysis. The leading candidates were identified as 94381 and 1830 through computational screening of a natural chemical library. These compounds exhibited resilient binding stability, advantageous solubility, ideal drug-likeness, and synthetic viability. The molecular docking and MM-GBSA analyses confirmed their significant binding affinity, while the MD simulations and PCA analysis demonstrated their capacity to maintain stable associations with Aurora A kinase over the 100 ns simulation period. The results of this study underscore the potential of 94381 and 1830 as aurora kinase A inhibitors for leukaemia treatment, underscoring the necessity of additional experimental validation. The results serve as a firm foundation for forthcoming preclinical and clinical investigations and emphasise the significance of computational drug discovery methods in the rapid identification of new anticancer agents.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

J. K. is responsible for research design, data collection, data interpretation, writing, finalizing and revision.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Key Statistics for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/acute-myeloid-leukemia/about/key-statistics.html. [Last accessed on 12 Feb 2025].

Tang A, Gao K, Chu L, Zhang R, Yang J, Zheng J. Aurora kinases: novel therapy targets in cancers. Oncotarget. 2017;8(14):23937-54. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14893, PMID 28147341.

Damodaran AP, Vaufrey L, Gavard O, Prigent C. Aurora a kinase is a priority pharmaceutical target for the treatment of cancers. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38(8):687-700. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.05.003, PMID 28601256.

Howard S, Berdini V, Boulstridge JA, Carr MG, Cross DM, Curry J. Fragment-based discovery of the Pyrazol-4-Yl urea (AT9283), a multitargeted kinase inhibitor with potent aurora kinase activity. J Med Chem. 2009;52(2):379-88. doi: 10.1021/jm800984v, PMID 19143567.

Goldenson B, Crispino JD. The aurora kinases in cell cycle and leukemia. Oncogene. 2015;34(5):537-45. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.14, PMID 24632603.

Kollareddy M, Zheleva D, Dzubak P, Brahmkshatriya PS, Lepsik M, Hajduch M. Aurora kinase inhibitors: progress towards the clinic. Investig New Drugs. 2012;30(6):2411-32. doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9798-6, PMID 22350019.

Kim SJ, Jang JE, Cheong JW, Eom JI, Jeung HK, Kim Y. Aurora a kinase expression is increased in leukemia stem cells and a selective aurora a kinase inhibitor enhances ara c induced apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Korean J Hematol. 2012;47(3):178-85. doi: 10.5045/kjh.2012.47.3.178, PMID 23071472.

Siudem P, Szeleszczuk L, Paradowska K. Searching for natural aurora a kinase inhibitors from peppers using molecular docking and molecular dynamics. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(11):1539. doi: 10.3390/ph16111539, PMID 38004405.

Mirgany TO, Asiri HH, Rahman AF, Alanazi MM. Discovery of 1H-benzo[d]Imidazole-(halogenated) benzylidenebenzohydrazide hybrids as potential multi-kinase inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17(7):839. doi: 10.3390/ph17070839, PMID 39065690.

Ion GN, Nitulescu GM, Mihai DP. Machine learning assisted drug repurposing framework for discovery of Aurora Kinase B inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;18(1):13. doi: 10.3390/ph18010013, PMID 39861075.

Danapur V, Sringeswara A. Pharmacognostic studies on Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2019;1(1):13-5. doi: 10.33545/26647222.2019.v1.i1a.2.

Moore AS, Blagg J, Linardopoulos S, Pearson AD. Aurora kinase inhibitors: novel small molecules with promising activity in acute myeloid and Philadelphia-positive leukemias. Leukemia. 2010;24(4):671-8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.15, PMID 20147976.

Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235-42. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235, PMID 10592235.

Bavetsias V, Large JM, Sun C, Bouloc N, Kosmopoulou M, Matteucci M. Imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine derivatives as inhibitors of aurora kinases: lead optimization studies toward the identification of an orally bioavailable preclinical development candidate. J Med Chem. 2010;53(14):5213-28. doi: 10.1021/jm100262j, PMID 20565112.

Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46(1-3):3-26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0, PMID 11259830.

Lipinski CA. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2000;44(1):235-49. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8719(00)00107-6, PMID 11274893.

Mao J, Akhtar J, Zhang X, Sun L, Guan S, Li X. Comprehensive strategies of machine learning based quantitative structure-activity relationship models. iScience. 2021;24(9):103052. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103052, PMID 34553136.

Davies M, Nowotka M, Papadatos G, Dedman N, Gaulton A, Atkinson F. ChEMBL Web services: streamlining access to drug discovery data and utilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W612-20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv352, PMID 25883136.

Landrum G. RDKit: open source cheminformatics. Release. 2014;3:1. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10398.

Rogers D, Hahn M. Extended connectivity fingerprints. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50(5):742-54. doi: 10.1021/ci100050t, PMID 20426451.

Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J, He S. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D1373-80. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac956, PMID 36305812.

O Boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, Morley C, Vandermeersch T, Hutchison GR. Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform. 2011;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33, PMID 21982300.

Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(16):2785-91. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256, PMID 19399780.

Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function efficient optimization and multithreading. J Comp Chem. 2010;31(2):455-61. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334, PMID 19499576.

Koh HY, Nguyen AT, Pan S, May LT, Webb GI. Physicochemical graph neural network for learning protein ligand interaction fingerprints from sequence data. Nat Mach Intell. 2024;6(6):673-87. doi: 10.1038/s42256-024-00847-1.

Argaman N, Makov G. Density functional theory: an introduction. Am J Phys. 2000;68(1):69-79. doi: 10.1119/1.19375.

Rozhenko AB. Density functional theory calculations of enzyme inhibitor interactions in medicinal chemistry and drug design. In: Gorb L, Kuz’min V, Muratov E, editors. Application of computational techniques in pharmacy and medicine. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands 2014. p. 207-40. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9257-8_7.

Sun Q, Berkelbach TC, Blunt NS, Booth GH, Guo S, Li Z. PySCF: the Python-based simulations of chemistry framework. WIREs Comp Mol Sci. 2018;8(1):e1340. doi: 10.1002/wcms.1340.

Tirado Rives J, Jorgensen WL. Performance of B3LYP density functional methods for a large set of organic molecules. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4(2):297-306. doi: 10.1021/ct700248k, PMID 26620661.

Nedelec JM, Hench LL. Effect of basis set and of electronic correlation on ab initio calculations on silica rings. J Non-Crystalline Solids. 2000;277(2-3):106-13. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3093(00)00306-9.

Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics drug likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717, PMID 28256516.

Banerjee P, Eckert AO, Schrey AK, Preissner R. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W257-63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky318, PMID 29718510.

Bauer P, Hess B, Lindahl E. GROMACS 2022.4 manual; 2022 Nov 16. doi: 10.5281/ZENODO.7323409.

Huang J, MacKerell AD. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. J Comput Chem. 2013;34(25):2135-45. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23354, PMID 23832629.

Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J. CHARMM general force field: a force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(4):671-90. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367, PMID 19575467.

Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys. 1993;98(12):10089-92. doi: 10.1063/1.464397.

Harrach MF, Drossel B. Structure and dynamics of TIP3P, TIP4P, and TIP5P water near smooth and atomistic walls of different hydroaffinity. J Chem Phys. 2014;140(17):174501. doi: 10.1063/1.4872239, PMID 24811640.

Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJ, Fraaije JG. Lincs: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comp Chem. 1997;18(12):1463-72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199709)18:12<1463::AID-JCC4>3.0.CO;2-H.

Bussi G, Donadio D, Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem Phys. 2007;126(1):014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420, PMID 17212484.

Martonak R, Laio A, Parrinello M. Predicting crystal structures: the Parrinello-Rahman method revisited. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90(7):075503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.075503, PMID 12633242.

Lipinski CA. Lead and drug-like compounds: the rule of five revolution. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2004;1(4):337-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007, PMID 24981612.

Nogara PA, Saraiva R De A, Caeran Bueno D, Lissner LJ, Lenz Dalla Corte C, Braga MM. Virtual screening of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors using the lipinski’s rule of five and zinc databank. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:870389. doi: 10.1155/2015/870389, PMID 25685814.

PD, SS, MR, VL. Ligand-based virtual screening on natural compounds for discovering active ligands. Pharm Chem. 2011;3(3):51-7.

Nath A, Kumer A, Khan MW. Synthesis, computational and molecular docking study of some 2,3-dihydrobenzofuran and its derivatives. J Mol Struct. 2021;1224:129225. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129225.

Cosconati S, Forli S, Perryman AL, Harris R, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. Virtual screening with AutoDock: theory and practice. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2010;5(6):597-607. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2010.484460, PMID 21532931.