Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 181-192Original Article

NANOMICELLAR DISPERSION-BASED APPROACH TO IMPROVE AMISULPRIDE DISSOLUTION: FORMULATION, CHARACTERIZATION, AND IN VITRO RELEASE STUDY

HAIDER HANI HASHIM1, SABA ABDULHADI JABER2*

1AL-Shaheed Al-Sader General Hospital, Ministry of Health, Iraq. 2Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq

*Corresponding author: Saba Abdulhadi Jaber; *Email: sabahadeejabir77@gmail.com

Received: 01 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 09 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This research aims to overcome the solubility and absorption limitations of amisulpride (AMS) by formulating it into a nano-micellar (NM) delivery system, thereby improving its oral bioavailability and efficacy as an antiemetic through enhanced dissolution rate and extent.

Methods: Six types of nanocarriers, Soluplus(SLP), D-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate(TGPS), Poloxamer (POL 188 and407), Solutol HS-15(STL-H15), and Tween-80, were used for the preparation of AMS as nano micellar dispersion(AMS-NM) either alone with 1:2,1:4,1:6, and 1:8 ratios or in combination with 1:4:1 and 1:4:2 ratios by utilizing Thin film hydration method. Twenty-four formulas were prepared and primarily checked for physical stability, then subjected to particle size (P. size), polydispersity index (PDI), entrapment efficiency (EE%), drug loading (DL%), and solubility factor (Sf) measurements. Only the selected formulas with accepted results of physical appearance and in vitro Characterization will progress to the release Study. Morphological and compatibility analyses, as well as Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and X-ray diffraction, were performed only for one optimal formula.

Results: Out of 24 nanomicelle formulations (F1–F24), four (F2, F4, F6, and F18) exhibited physical stability with optimal P. size, PDI, EE%, and Sf, qualifying them for further release studies. The formulation F2, containing a 1:4 ratio of SLP, emerged as the optimized system, achieving a complete (100%) release of AMS within 45 min, significantly surpassing the 24% release observed from the pure drug suspension. F2 demonstrated a nanoscale p. size of 67.1±2.2 nm, low PDI (0.061±0.002), high EE% (73±3.6), drug loading of 14.6±0.09%, and a solubility factor of 4.3. It presented a clear, faint light blue appearance with nano-spherical morphology, excellent drug-excipient compatibility, and structural stability. DSC and PXRD analyses confirmed successful AMS entrapment within the micellar core.

Conclusion: This strategy not only addresses AMS’s inherent solubility limitations but also utilizes nanoscale carrier properties and size-dependent mechanisms to enhance drug dissolution and absorption, thereby optimizing therapeutic delivery and showing great promise for improving clinical efficacy.

Keywords: Amisulpride, Nano micelle, In vitro release, Entrapment efficiency %

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.55349 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

An emerging field of nanotechnology has developed over the past decade, as reducing the size of drug particles increases their solubility, dissolution rate, and bioavailability [1, 2]. Polymeric nanoparticles, liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, nanostructured lipid carriers, micro-and nanoemulsions, self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems, and polymeric micelles were among the various approaches developed [3].

Nanomicelles (NMs) are generally made of amphiphilic polymers that self-assemble in water into hydrophobic core-hydrophilic shell nanostructures (20–200 nm) at concentrations higher than the critical micellar concentration (CMC). The presence of a lipophilic core enhances the solubility of poorly water-soluble molecules, providing the potential for controlled drug release [4]. At the same time, the hydrophilic shell protects the encapsulated drug from the external medium and prevents interaction with plasma components, resulting in long circulation properties in vivo. Moreover, the small particle size prolongs the residence time in blood circulation, bypassing the liver and spleen filtration and glomerular elimination, and enhances cellular uptake and the ability to cross epithelial barriers. All these aspects result in increased drug bioavailability [5].

The use of micelles as drug carriers offers several benefits, including simplified development, lower expenses, easier passage of cargo across biological barriers, enhanced solubility in aqueous media, including the undisturbed water layer of the intestine, controlled release profiles, and degradation shielding [6].

Amisulpride (AMS) is an atypical antipsychotic/antischizophrenic agent with limited extrapyramidal side effects. It is a member of pyrrolidines, an aromatic amine, a sulfone, a member of benzamides, and an aromatic amide [7]. Intravenous Amisulpride is approved by the FDA (2020) to be used in adults to prevent and treat postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), either alone or in combination with an antiemetic of a different class. It is also effective at preventing delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) caused by highly emetogenic chemotherapy [8]. AMS acts as an antiemetic agent by blocking dopamine signaling in the chemoreceptor trigger zone, a brain area that relays stimuli to the vomiting center [9, 10].

AMS exhibits low oral bioavailability (~48%) [11], primarily due to its poor solubility at the higher pH of the intestine, attributed to its weakly basic nature (pKa 9.37) [12]. Additionally, its absorption may be further limited by efflux via P-glycoprotein transporters and first-pass metabolism, although these factors are less prominent [13, 14].

Soluplus (SLP) has garnered significant attention among polymeric components that have recently been investigated for their potential in pharmaceutical and drug delivery product formulations. It is (57% polyvinyl caprolactam, 30%polyvinyl acetate, and 13% polyethylene glycol 6000) graft copolymer; the hydrophilic portion is made up of the polyethylene glycol backbone, while the lipophilic fraction is made up of the vinyl caprolactam/vinyl acetate side chains [15, 16]. As a result of its amphiphilic character, it can form micelles in an aqueous solution above the CMC value of 7.6 mg/l, while also exhibiting a significant solubility enhancement effect [17, 18].

Tocopherol polyethylene glycol succinate (TPGS), a synthetic analog of alpha-tocopherol, is gaining more attention in medication delivery strategies. The alpha-tocopherol component of the molecule is soluble in fat, whereas the PEG portion is soluble in water. The molecule is a non-ionic surfactant that is both biocompatible and biodegradable. Moreover, TPGS also functions as a permeation enhancer and absorption enhancer; it has an intermediate molecular weight (~1513 g/mol) and is utilized in pharmaceutical corporations due to its ability to withstand thermally stable conditions without degradation [19, 20].

Solutol HS-15 (STL-H15) is a non-ionic surfactant that is composed of thirty percent free polyethylene glycol and seventy percent polyglycol mono-and di-esters of twelve-hydroxystearic acid [16]. Strong stability, good biocompatibility, enhanced ability to pass through mucosal membranes, and the extraordinary ability to dissolve hydrophobic medicines are some of the characteristics that set it apart from other substances [21, 22].

Poloxamer 188 (POL 188) and Tween 80 (TWN 80) are often utilized in formulating mixed nano micelles (MNM) due to their surfactant properties, which enhance the stability and solubility of poorly soluble drugs. Some key points regarding their use in MNM formulations include reduced particle size and enhanced drug entrapment efficiency [23].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material

AMS and TGP were purchased from Hangzhou Hyper Chemicals Limited. SLP and STL-H15 were purchased from BASF in Germany and Picasso in China. TWN 80, POL 188, and POL 407 were purchased from Fluka Chemical. Methanol was purchased from Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd., India. Deionized water (DW) and the other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade.

Method preparation of AMS-NM

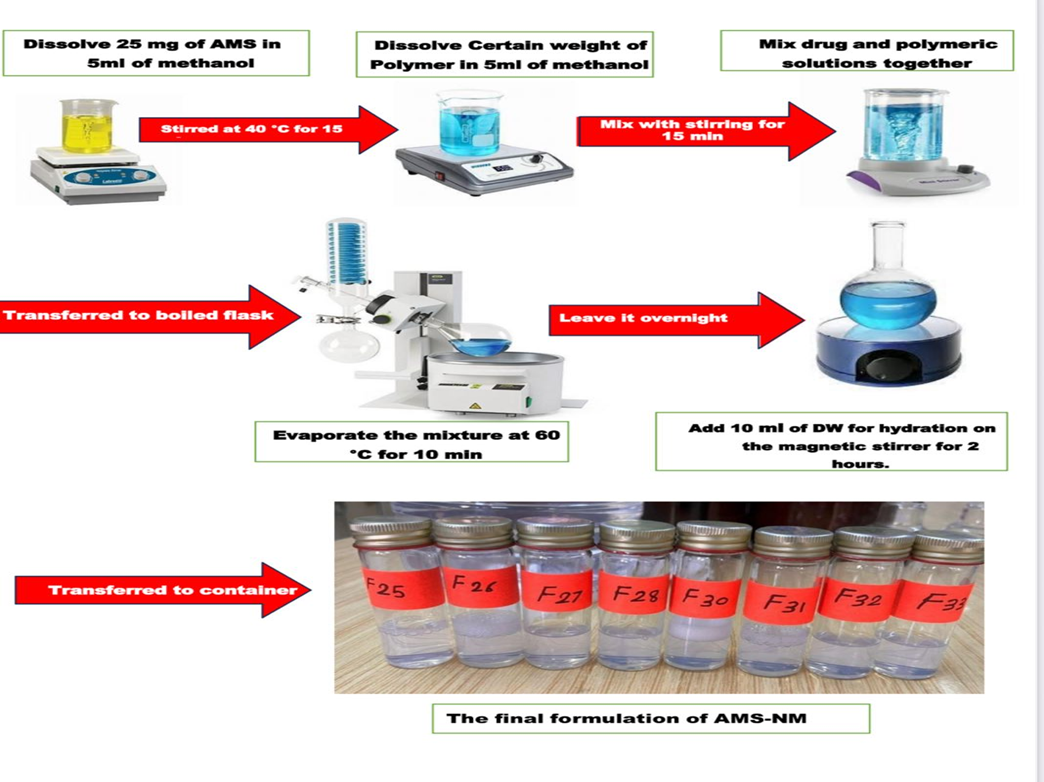

Twenty-five mg of AMF was dissolved in 5 ml of an organic solvent (methanol). The required quantities of each polymer (SLP, TGPS, STL-H15, TWN 80, POL 188, and 407) according to the specified ratios [(1:2), (1:4), (1:6), (1:8), (1:4:1), and (1:4:2)] were dissolved in 5 ml of the same organic solvent. Both solvents were stirred separately and then mixed in a round-bottom flask over a magnetic stirrer at 45 °C for 15 min. The solvent mixture was then evaporated for 10 min at 60 °C using a rotary evaporator (Bibby Scientific Limited, UK). Afterward, the flask was left overnight to allow any remaining solvent to evaporate at ambient temperature. A magnetic stirrer at 300 rpm was used for two hours to hydrate the film by adding 10 ml of deionized water (DW) [24, 25], as demonstrated in fig. 1.

Table 1 shows that twenty-four formulas were prepared, sixteen of which are single polymeric NM, and the others are mixed NM. All were subjected to physical evaluation and in vitro Characterization.

Fig. 1: Preparation method of NM

In vitro characterization

Particle size measurement and polydispersity index

A particle size analyzer (Malvern Zetasizer, UV-1700 Pharma Spec, Shimadzu, Japan) utilizes dynamic light scattering to determine the average particle size (P. size) and polydispersity index (PDI) of the prepared NM at room temperature. Each measurement was performed three times, and results are reported as the mean±standard deviation (SD) [12].

Encapsulation efficiency and drug loading capacity

An indirect approach was employed to determine the drug loading capacity (DL%) and encapsulation efficiency (EE%). To isolate unencapsulated AMS, a sample of the formulation was centrifuged using an Amicon® Ultra centrifugal filter (10 kDa molecular weight cutoff, Merck Millipore Ltd., Ireland). The concentration of free AMS was quantified spectrophotometrically at 279 nm with a UV-visible spectrophotometer.

The EE% and DL% values were calculated using the following equations [28, 29]:

EE%= x100-------------(1)

x100-------------(1)

DL%= x100-------------(2)

x100-------------(2)

This method ensures the accurate quantification of drug encapsulation and loading in nanomicellar systems.

Table 1: Composition of AMS micellar liquid dispersions

| Formula code | AMS (mg) |

Drug-polymer ratio | SLP (mg) | TPGS (mg) | POL407(mg) | POL 188 (mg) |

STL-H15 (mg) |

TWN 80 (mg) |

DW up to 10 (ml) |

| F1 | 25 | 1:2 | 50 | 10 | |||||

| F2 | 25 | 1:4 | 100 | 10 | |||||

| F3 | 25 | 1:6 | 150 | 10 | |||||

| F4 | 25 | 1:8 | 200 | 10 | |||||

| F5 | 25 | 1:2 | 50 | 10 | |||||

| F6 | 25 | 1:4 | 100 | 10 | |||||

| F7 | 25 | 1:6 | 150 | 10 | |||||

| F8 | 25 | 1:8 | 200 | 10 | |||||

| F9 | 25 | 1:2 | 50 | 10 | |||||

| F10 | 25 | 1:4 | 100 | 10 | |||||

| F11 | 25 | 1:6 | 150 | 10 | |||||

| F12 | 25 | 1:8 | 200 | 10 | |||||

| F13 | 25 | 1:2 | 50 | 10 | |||||

| F14 | 25 | 1:4 | 100 | 10 | |||||

| F15 | 25 | 1:6 | 150 | 10 | |||||

| F16 | 25 | 1:8 | 200 | 10 | |||||

| F17 | 25 | 1:4:1 | 100 | 25 | 10 | ||||

| F18 | 25 | 1:4:2 | 100 | 50 | 10 | ||||

| F19 | 25 | 1:4:1 | 100 | 25 | 10 | ||||

| F20 | 25 | 1:4:2 | 100 | 50 | 10 | ||||

| F21 | 25 | 1:4:1 | 100 | 25 | 10 | ||||

| F22 | 25 | 1:4:2 | 100 | 50 | 10 | ||||

| F23 | 25 | 1:4:1 | 100 | 25 | 10 | ||||

| F24 | 25 | 1:4:2 | 100 | 50 | 10 |

Solubilization capacity assessment

The solubilization capacity of NM formulations was evaluated using the classical shake-flask method. Excess AMS was added to 5 ml of DW and surfactant dispersions (prepared by dissolving surfactants equivalent to NM formulations in an aqueous phase under continuous stirring). Mixtures were equilibrated for 48 h at room temperature in a shaking water bath. Samples were then centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 30 min, and supernatants were filtered and diluted. AMS concentration was quantified via UV spectrophotometry using a methanol-based calibration curve.

The solubility factor (Sf) was calculated as:

Sf = --------------- (3)

--------------- (3)

Where: Smic represents the solubility of AMS in surfactant dispersion (simulating NM formulations), and Sw represents the solubility of AMS in DW [30].

This method is a gold-standard approach for quantifying solubilization capacity in nanomicellar systems, particularly for poorly soluble drugs like AMS [31].

Optimization of the selected formulas related to the in vitro characterization

Only the selected formulas proceeded to the in vitro release study, based on physical stability for at least two days without precipitation, as well as Characterization results such as P. size, PDI, EE%, DL%, and Sf determination. Formulas that exhibited physical stability, clarity without any precipitation, accompanied by a smaller particle size within the nano range, and an acceptable PDI value. The value of EE% should be high relative to the other formulas to confirm better entrapment. The value of Sf could be considered as an indicator of the delivery system's effect on improving the drug's dissolution.

Determination of the AMS solubility in different media

After adding an excess amount of AMS to a fixed volume of each PBS (pH 6.8), methanol, and DW. The mixture was incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in a shaking water bath to reach equilibrium. The suspension was centrifuged for 30 min at 6000 rpm and then passed through a 0.45 μm pore membrane filter. The calibration curve of AMS in each of the media mentioned above was used to determine the concentration of AMS in the filtrate. The experiment was conducted in triplicate, and the mean±SD was determined [32].

In vitro release of AMS from the prepared NM dispersion

The release profile of AMS from nanomicellar formulations (AMS-NMs) was assessed using a dialysis membrane (cellulose, molecular weight cutoff 8,000–14,000 Da) immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 6.8) at 37 °C to simulate physiological conditions. Before testing, the membrane was equilibrated overnight in PBS. A 5 ml aliquot of AMS-NM dispersion, equivalent to 12.5 mg of AMS, was enclosed within the membrane and submerged in 500 ml of PBS maintained at constant temperature with gentle agitation (50 rpm) using a USP dissolution apparatus type II, following FDA guidelines for AMS oral formulations as demonstrated in fig 2. Aliquots of 5 ml were withdrawn at specified intervals (5, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min), with immediate replacement by fresh medium to maintain sink conditions [33]. The concentration of released AMS was quantified spectrophotometrically at 279 nm, enabling precise monitoring of drug release kinetics.

Release kinetics study

The in vitro release kinetics of AMS from the selected NM formulation were evaluated to understand the drug release behavior. The release data were fitted to various kinetic models, including zero-order (cumulative percentage of drug released versus time), first-order (logarithm of the cumulative percentage of drug released versus time), Higuchi model (cumulative percentage of drug released versus the square root of time), and the Korsmeyer-Peppas model (logarithm of drug release versus logarithm of time). The correlation coefficient (R²) was determined from the linear regression of these plots. Additionally, the release exponent (n) was calculated from the Korsmeyer-Peppas model to characterize the release mechanism [34, 35].

Zero order: Q = Q0+kt……………. (4)

First order: Q/Q0 =e−kt……. (5)

Higuchi: Q = k t1/2 …………………. (6)

Korsmeyer-Peppas: Q/Q0 =kt n…. (7)

Where Q represents the amount of drug released at time t, Q₀ represents the initial amount of drug released at time zero (usually Q0= 0 if no drug is released at the start), and k is the release constant.

Morphological characterization

Field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM)

Once the micelle had been tuned, a drop of it was deposited on aluminum stubs and allowed to air-dry. To ensure the slide remained in place on the specimen holder, double-coated adhesive tape was used. It was followed by the application of gold to the slide using a sputter coater while the slide was placed in a vacuum for ten minutes. This action was performed to establish a consistent coating that enables the creation of high-quality images using scanning electron microscopy. To obtain the pictures using FESEM, several magnifications were employed [36, 37].

Fig. 2: Photographic representation of the in vitro release of AMS nanomicelle dispersion using dissolution apparatus II (Paddle type)

Crystallinity specification

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The formulation was subjected to a DSC thermal analysis of the AMS, excipients, pure drug, and the optimum AMS-NM formula. Under a flow of nitrogen gas, each sample was carefully weighed and stored in aluminum pans. Then, they were heated at a rate of 10 °C/min and cooled at a rate of 40 °C/min. In the research, an empty aluminum baking pan served as a control [38].

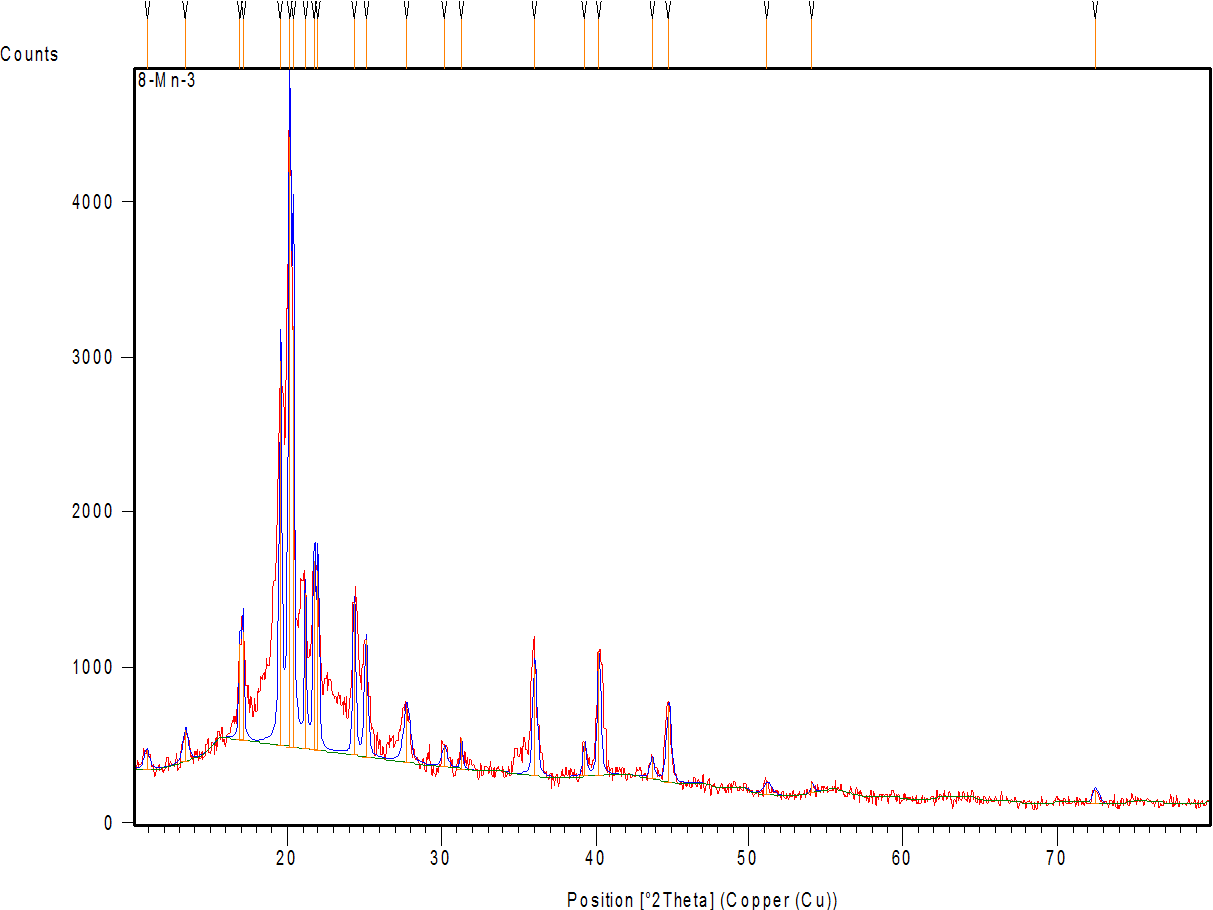

X-Ray powder diffraction (XRPD)

Using an X-ray diffractometer set up with Cu as the tube node, X-ray diffraction patterns of AMS, a physical mixture, and the optimum AMS-NM formula (F2) were obtained. Diffractograms were captured at room temperature with a voltage of 45 kV, a current of 30 mA, a step size of 0.02°, and a counting rate of 0.5 s/step. Scattering angles (2θ) were taken from 4° to 50° [39].

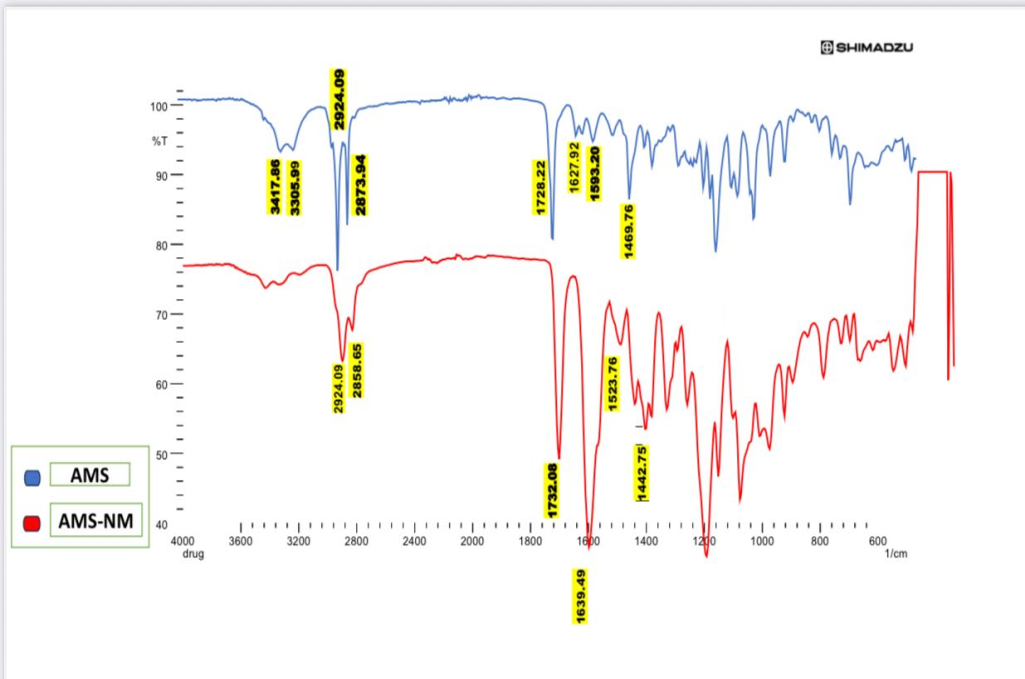

Drug-excipient compatibility study

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR spectroscopy combined with the attenuated total reflectance (ATR) technique was used to detect any potential contact or complexation between the active ingredient and selected excipients, as well as AMS-excipient compatibility. AMS, as dug powder with the selected AMS-NM formulas, was put directly, without any prior preparation, into the crystal area. Then, the pressure arm was placed above the sample and scanned over the range between 4000-400 cm-1 wavenumber [40].

Stability studies

Stability assessment on storage

To evaluate the long-term physical and chemical stability of AMS-loaded NMs, samples were stored in sealed glass vials under two conditions: ambient temperature (25 °C) and refrigerated (4 °C) for 90 d. Post-storage, formulations underwent comprehensive analysis, including drug content quantification, P. size measurement, PDI, EE%, and Visual inspection for precipitation events.

Stability upon water dilution

The physical stability of the AMS-loaded NM was evaluated by diluting the selected formulation with DW in a 1:10 ratio. Three hours later, PDI and the average diameter were assessed [41]. The studies were conducted in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

To determine whether the variations in the factors that were applied are significant at the level of (P ˂0.05), highly significant at a level of (P˂0.005), and non-significant at the level of (P>0.05), the research's findings were presented as the mean of three triplicate models±(SD), and applying one way (ANOVA) using Microsoft Excel 2010, followed by Tukey's HSD test. When One-way ANOVA results show significant differences, Tukey’s test confirms that these differences are not due to random variation but represent true group differences at each time point.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

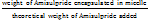

Effect of polymer type and concentration on the in vitro characterization of ANM-NM: Particle size, PDI, EE%, DL%, and Sf

Effect of solplus

From the results in table 2 of the AMS-NM characterization, it is noticeable that increasing the concentration of SLP from 1:2,1:4,1:6, and 1:8 is associated with stable particle sizes (70±2.6, 67.1±2.2, 64.92±3.9, and 65.03±2.4, respectively) rather than a direct reduction in size. SLP is an amphiphilic polymer that self-assembles into spherical NM with a consistent mean size of ~60–70 nm, regardless of polymer concentration. SLP-NM formed above a CMC of 7.6 mg/l, beyond which additional polymer primarily increases the number of micelles rather than altering their size. Pignatello demonstrated the same result in his studies, which declared the rule of SLP for solving the problem of poorly soluble drugs via nano-micellar formulation [42]. The PDI of the AMS-NM dispersion prepared with SLP is between 0.002±0.001 to 0.061± 0.002, which indicates the nano micelles are very uniform in size, with almost no variation between particles, i. e., a highly monodispersed system; which was very important to ensure predictable drug release, and improve stability of the formulations [43].

Increasing the concentration of SLP leads to more polymer molecules being available in the solution, so more micelles, which means more sites for the drug to be encapsulated; as a result, the EE% gradually increases to 54±2.1, 73±3.6, 68±4.1, and 69±5.0 by increasing SLP concentration and decreasing the P. size within certain limits [44]. There is a direct relationship between the EE% and Sf, as demonstrated in table 2. Therefore, F2, with a higher value of EE%, exerts a higher Sf, which is approximately 4.3-fold.

A high EE% does not necessarily mean a high DL% because it also depends on the total mass of the carrier and the drug-to-carrier ratio, so the result of AMS-NM illustrated in table 2 declares that the higher value of DL% (18 %) for F1-related to the lowe polymer to drug ratio, while for F2 which exerts higher value of EE% with DL% of 14.6 % which fixed the conclusion that the correlation is positive but not strictly linear; both values must be considered together to evaluate NM drug loading performance effectively [45].

Considering all the above results of AMS-NM dispersion using SLP as a primary polymer, F2 was selected for further in vitro analysis.

Effect of TGPS

AMS-NM prepared with TGPS as a single polymer exerts a direct or positive relationship between TGPS concentration and P. size, as demonstrated in table 2 for F5, F6, F7, and F8, so as the AMS: TGPS ratio increased from 1:2,1:4,1:6 to 1:8 the P. size also increased from 29.31±1.8, 58.46±1.28, 65.93±1.52, to 300±1.98 nm, respectively. This result is often observed because higher concentrations of TGPS can promote the formation of larger micellar aggregates, possibly due to enhanced hydrophobic interactions and changes in the micelle's core structure. Additionally, TGPS can influence the assembly and growth of micelles, resulting in larger P sizes as the ratio increases [46]. The values of PDI are 0.348±0.012, 0.263±0.13, and 0.323±0.04 for F5, F6, and F7, respectively, indicating a moderate monodisperse system. At the same time, F8, with a particle size of 300 nm, exerts a PDI value of 0.7 (poor monodisperse system) [43]. Increasing the TPGS concentration or ratio in AMS-NM correlates with increased EE% up to an optimal level, beyond which the effect is minimal or undetectable, as shown in F5, F6, and F7, with EE% equal to 46±1.2, 84±2.0, and 56±1.3 respectively, which is attributed to the enhanced hydrophobic core volume and micelle stability provided by TPGS (TPGS increases the hydrophobic core capacity of the micelles, allowing more hydrophobic drug molecules to be encapsulated effectively) [48, 49]. The values of Sf are 3.9, 7.7, and 3.2 folds for F5, F6, and F7, indicating a direct relationship between Sf and EE%. The value of DL% is 16.8±2.2, which complies with the EE%. Considering all the above-discussed results of AMS-NM dispersion using TGPS as the primary polymer, F6 was selected for further in vitro analysis.

Effect of poloxamer 188 and 407

Poloxamers 188 and 407 were used in the ratio of 1:2, 1:4, 1:6, and 1:8 to examine the effect of these two hydrophilic polymers on the characterization of AMS-polymeric dispersion starting from the p. size listed in table 2 for F9 to F16, which demonstrates the indirect relationship between the polymeric concentration and the P. size. However, all the measured sizes are not accepted compared to other polymers (SLP and TGPS). The larger p. size observed with Poloxamer 188 and 407 polymeric dispersions is attributed to their molecular characteristics, concentration-dependent aggregation, and gelation behavior. Careful optimization of polymer concentration and formulation conditions is crucial for maintaining particle size within the nanoscale range [50]. Therefore, both POL (188 and 407) are not used alone in the present study to produce NMs because they may not offer sufficient stability and control over the size and shape of the NMs; additionally, they may not provide the required amphiphilic balance necessary for stable NM formation [51]. Instead of using them alone, these polymers are primarily used in conjunction with another polymer to prepare mixed micelles or binary micelle systems.

Table 2: In vitro characterization of AMS-NM (Particle size analysis (p. size), polydispersity index (PDI), entrapment efficiency (EE%), drug loading (DL%), and solubility factor (Sf)

| NM code | Drug-polymer ratio | Physical appearance | p. size nm | PDI | EE% | DL% | Sf |

| F1 | 1:2 | Stable** | 70±2.6 | 0.0171±0.001 | 54±2.1 | 18±1.09 | 2.3 |

| F2* | 1:4 | Stable** | 67.1±2.2 | 0.061±0.002 | 73±3.6 | 14.6±0.09 | 4.3 |

| F3 | 1:6 | Stable** | 64.92±3.9 | 0.028±0.004 | 68±4.1 | 9.7±0.89 | 3.1 |

| F4* | 1:8 | Stable** | 65.03±2.4 | 0.002±0.001 | 69±5.0 | 6.9±1.3 | 3.3 |

| F5 | 1:2 | Stable** | 29.31±1.8 | 0.348±0.012 | 46±1.2 | 15.3±.0.88 | 3.98 |

| F6* | 1:4 | Stable** | 58.46±1.28 | 0.263±0.13 | 84±2.0 | 16.8±2.2 | 7.7 |

| F7 | 1:6 | Stable** | 65.93±1.52 | 0.323±0.04 | 56±1.3 | 8±1.2 | 2.9 |

| F8 | 1:8 | Stable** | 300±1.98 | 0.775±0.01 | ----- | ---- | ----- |

| F9 | 1:2 | Cloudy | 877.6±15 | 0.791±0.28 | ---- | ----- | ------ |

| F10 | 1:4 | Cloudy | 667.8±8.22 | 0.665±0.01 | ---- | ----- | ------ |

| F11 | 1:6 | Cloudy | 405.6±5.85 | 0.307±0.08 | ---- | ----- | ------ |

| F12 | 1:8 | Cloudy | 216.5±3.8 | 0.248±0.02 | ---- | ----- | ------ |

| F13 | 1:2 | Cloudy | 887.3±2.7 | 0.73±0.12 | ---- | ----- | ------ |

| F14 | 1:4 | Cloudy | 332.7±1.6 | 0.375±0.01 | ---- | ----- | ------ |

| F15 | 1:6 | Cloudy | 299.9±1.2 | 1.182±0.2 | ---- | ----- | ------ |

| F16 | 1:8 | Cloudy | 183.8±1.6 | 0.28±0.02 | ---- | ----- | ------ |

| F17 | 1:4:1 | Stable** | 68.79±2.6 | 0.057±0.009 | 70.3±1.5 | 11.7±0.56 | 2.6 |

| F18* | 1:4:2 | Stable** | 65.79±2.1 | 0.03±0.002 | 76±2.1 | 10.9±0.07 | 4 |

| F19 | 1:4:1 | Stable** | 78±1.1 | 0.0690±0.01 | 45.6±0.60 | 7.6±0.56 | 3.2 |

| F20 | 1:4:2 | Stable** | 76.±0.8 | 0.1409±0.06 | 53±0.9 | 7.57±0.07 | 4.09 |

| F21 | 1:4:1 | Stable** | 85.2±1.3 | 0.107±0.01 | 58±1.35 | 9.7±0.21 | 2.9 |

| F22 | 1:4:2 | Stable** | 86.72±1.2 | 0.1202±0.01 | 61±1.8 | 8.7±0.11 | 3.34 |

| F23 | 1:4:1 | Stable** | 75.9±1.52 | 0.046±0.001 | 46.5±2.5 | 7.7±0.23 | 3.2 |

| F24 | 1:4:2 | Stable** | 68.18±1.31 | 0.0309±0.002 | 49±1.1 | 7.0±0.13 | 3.24 |

Results expressed as a mean±SD, (n=3). F* represents the formula selected for in vitro release. Stable** means physically stable, clear with no precipitated particles, and with a faint light blue reflection, which indicates the nano size.

Effect of polymer combination

Based on the in vitro Characterization of the SLP-NM dispersions to select an F2(1:4) ratio for preparation of mixed polymeric NM via (1:4:1) and (1:4:2) ratios with STL-H15(F17, F18), TWN 80(F19, F20), TPGS (F21, F22), and POL-188 (F23, F24), as declared in table 1.

Fig. 3 and table 2 indicate that P. size, PDI, EE%, and Sf were measured for all the prepared mixed polymeric NMs, starting from F17 and F18, as compared with F2, showing no significant changes (P>0.05) in all measured parameters, except that EE% was higher for F18. Since STL-H15 (surfactant) and SLP (polymer) form mixed micelles with similar hydrodynamic properties, the system retains micellar integrity, avoiding changes in size or stability. In contrast, for PDI, uniform mixing of polymers maintains monodispersity (PDI<0.2). The encapsulation efficiency increased for F18 with a higher ratio of STL H15 (HLB ~15) complements SLP (HLB ~14), reducing interfacial tension and enabling better drug partitioning into micelles. Additionally, Solutol's fatty acid esters improve compatibility with the hydrophobic drug (AMS). Additionally, Solutol's C15 fatty alcohol chains may expand the hydrophobic domain of the micellar core, creating more space for drug entrapment [52].

The particle size was significantly increased (P<0.05) for F19, F20, F21, and F22 as compared with F2, while the EE% with DL% was significantly decreased (P<0.05), as declared in table 2 and fig. 3. The effect of TWN 80 with HLB ~15 is more hydrophilic than SLP with HLB ~14, forms looser, larger mixed micelles due to the mismatched packing of its single hydrophobic tail (C18 chain) with SLP's bulkier polyvinyl caprolactam chains, as well as TPGS contains a bulky vitamin E (tocopherol) hydrophobic core and long PEG chain, creates larger micelles due to steric hindrance and expanded hydrophobic domains. Therefore, both surfactants disrupt the tight self-assembly of SLP, resulting in less compact, larger micelles.

Tween 80's single alkyl chain and TPGS's vitamin E provide fewer hydrophobic "pockets" compared to SLP's vinyl caprolactam-rich core, reducing drug affinity. Additionally, TWN 80 competes with the drug for incorporation into micelles, lowering the drug loading percentage (DL%). Finally, TWN 80 has a higher CMC (~0.012 mmol) than SLP (CMC ~0.0003 mmol), making mixed micelles more prone to dissociation and drug leakage [53, 54].

The effect of POL-188 as a copolymer was declared in the measurement of EE% and DL% for F23 and F24, which were found to be significantly lower than F2 since POL-188, being a nonionic surfactant with a relatively high HLB, tends to form micelles with larger hydrophilic shells and less compact hydrophobic cores compared to SLP alone. This can lead to a reduced hydrophobic domain volume and weaker interactions with hydrophobic drugs, thereby lowering the EE% and DL%, which is consistent with the data of F23 and F24 in table 2 [55].

Fig. 3: The effect of using polymer combination on P. size, EE%, DL%, and Sf (mean±SD, n=3)

Optimization of the selected formulas from in vitro characterization

Based on the results mentioned in table 2, F2, F4, F6, and F18 exhibited physical stability with P. sizes of 67.1, 64, 92, 58.46, and 65.79 nm, respectively. The PDI values were acceptable for a monodispersed system, which was very important to ensure predictable drug release and improve the stability of the formulations. Finally, the values of EE% and Sf were 73, 69, 84, and 76, with corresponding values of 4.3, 3.3, 7.7, and 4, respectively. The combination of the best results from all in vitro characterizations was observed in the four formulas (F2, F4, F6, and F18) that underwent an in vitro release study to select an optimum one that exhibited improvement in both the rate and extent of AMS dissolution.

Saturation solubility of amisulpride in different media

Table 3 below presents the data from the saturated solubility study conducted for AMS in PBS pH 6.8, methanol, and DW.

Table 3: Saturated solubility data of amisulpride

| Media for the solubility study | Solubility (mg/ml) | Description form |

| Methanol | 150.7±3.01 | Freely soluble |

| Phosphate buffer saline pH 6.8 (PBS) | 1.967±0.04 | Slightly soluble |

| Deionized water (DW) | 0.374±0.003 | Insoluble |

Based on the above results, methanol was selected as an appropriate solvent for AMS, and in vitro release can be performed under sink conditions.

In vitro release of AMS from the prepared NM dispersion

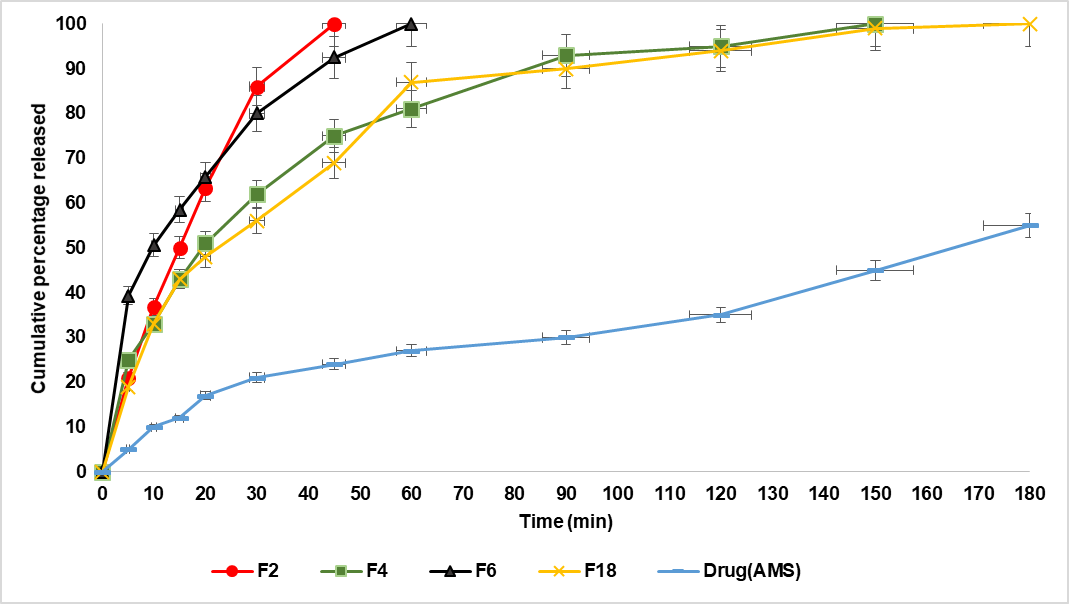

Depending on the results of the in vitro Characterization of the prepared AMS-NM dispersions, F2, F4, F6, and F18 were selected for further evaluation in the in vitro release study. As demonstrated previously, 5 ml of the prepared NM was placed within a dialysis bag, which was securely tied to the paddle of the dissolution apparatus, and then immersed in 500 ml of PBS. Fig. 4 illustrates the cumulative percentage released at 3 h time intervals of the prepared AMS-NM dispersion compared to the release profile of pure AMS. After 180 min (3 h), the pure drug (without formulation) achieves only 55% release, whereas F2, F6, F4, and F18 exhibit 100% release of AMS at 45, 60, 150, and 180 min, respectively.

To explain the release profile, several factors should be considered, including particle size, polymer type, and viscosity, which are correlated with the polymer concentration. F2 and F6 approximately exhibit similar behavior to the release of AMS. Still, it's a bit faster for F2 than F6, although the smaller particle size is associated with F6. Still, the polymer type is the causative factor here because SLP is an amphiphilic polymer that increases the solubility of poorly soluble drugs, thereby accelerating their release. In contrast, for TGPS, the incorporation of a drug in the core firmly remains inside the micelle, causing slower release [56]. F4 exerts a slower AMS release, although it is formulated with SLP, but with a 1:8 ratio, which increases the viscosity and retains the release [57]. F18 offers a slower release profile due to the inclusion of STL-H15 in combination with SLP, which forms a mixed micellar core that is more hydrophobic and structurally stable. This enhanced hydrophobic core provides a more favorable environment for the entrapment of hydrophobic drugs, resulting in a higher entrapment efficiency (EE%). At the same time, the drug becomes more tightly held within the micellar core, making it less available for rapid release into the surrounding medium [58].

Finally, all the prepared AMS-NM formulations exhibited significantly (P<0.05) improved drug release compared to the pure drug, which was confirmed by Tukey's HSD test specially for formulations F2 and F6 that demonstrated the best release profiles, which were significantly (P<0.05) higher than AMS as pure drug at all time intervals. However, we selected F2, which contains SLP at a 1:4 ratio, over the NM formulated with TPGS at a 1:4 ratio (F6). This choice was based not only on the superior physicochemical properties of SLP, such as its excellent solubilization capacity and stability, but also because the Self-nanomicellizing solid dispersion technique used for solidification in the final stage is more compatible with SLP-based formulations. Therefore, F2 was chosen as the optimized nanomicellar formula for further development and future studies [26].

Fig. 4: The release profile of AMS from F2, F4, F6, F18, and pure drug in PBS (pH 6.8) at 37 °C (mean±SD, n = 3)

Kinetics of drug release

Table 4 listed below demonstrates that the release of AMS from F2 NM dispersion follows the Korsmeyer–Peppas plot depending on the values of the regression coefficient, which were 0.9896 and the corresponding n-value equal to 0.8, which means that AMS released from 1:4 SLP micelles often shows a rapid, anomalous release (n ≈ 0.8), typical for nano micellar or polymeric systems with both diffusion and swelling/relaxation effects. The rapid release of about 60% of the drug within 20 min is typically attributed to the drug molecules located near or at the micelle surface or loosely bound within the micellar core. These drug molecules diffuse quickly into the release medium upon dilution or exposure to sink conditions [59, 60]. The rapid release (60% in 20 min, 100% in 45 min) is consistent with a system where both diffusions through the micellar matrix and the relaxation/erosion of the micelle structure contribute to the release, which provides an advantage for improving the rate and extent of AMS dissolution to exert it's required rapid effect as an antiemetic.

Table 4: The release kinetic modeling data mechanism of the selected AMS-NM (F2)

| Release mechanism release m | n-value | Korsmeyer–Peppas | Higuchi | First-order | Zero-order | Formula code |

| Anomalous release (Non-fickian) | 0.8 | 0.9896 | 0.9614 | 0.9764 | 0.8952 | Rsqr (F2) |

Morphological characterization

Field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM)

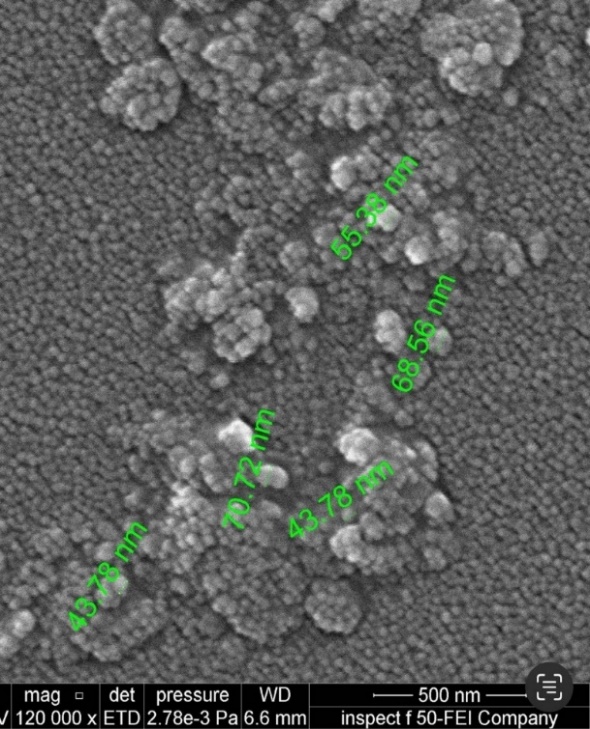

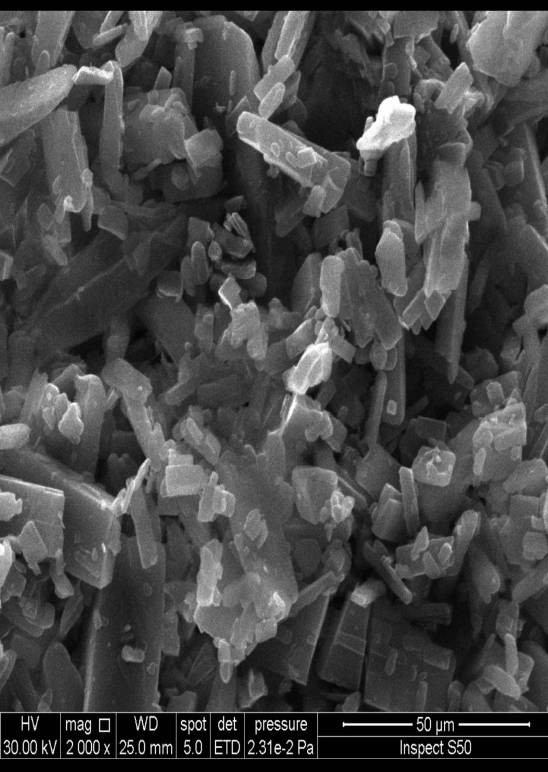

Fig. 5a demonstrates that the optimized, improved formula is spherical and has nanosized particles, compared with pure drug powder, which appears in fig. 5b as irregular macro-sized particles. The size calculated from FESEM is consistent with the results obtained by the zeta sizer using dynamic light scattering (DLS) [61].

Crystallinity specification

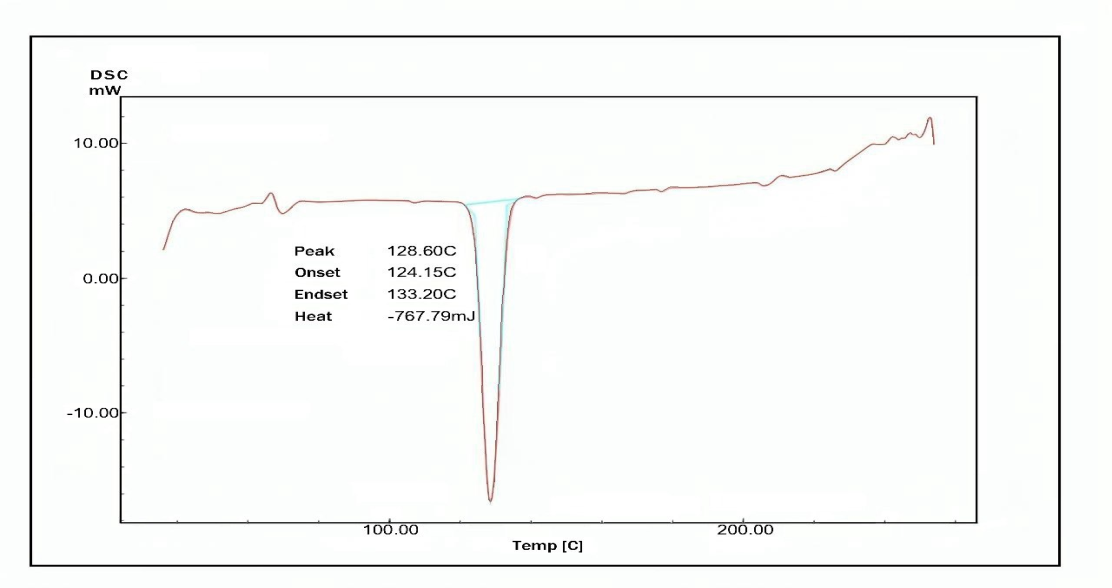

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

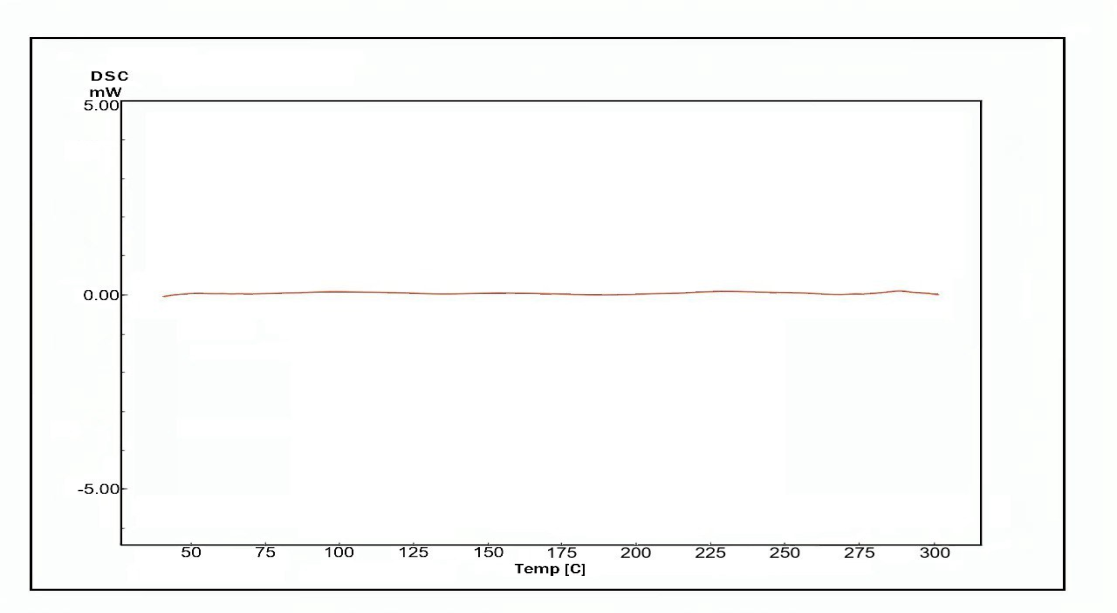

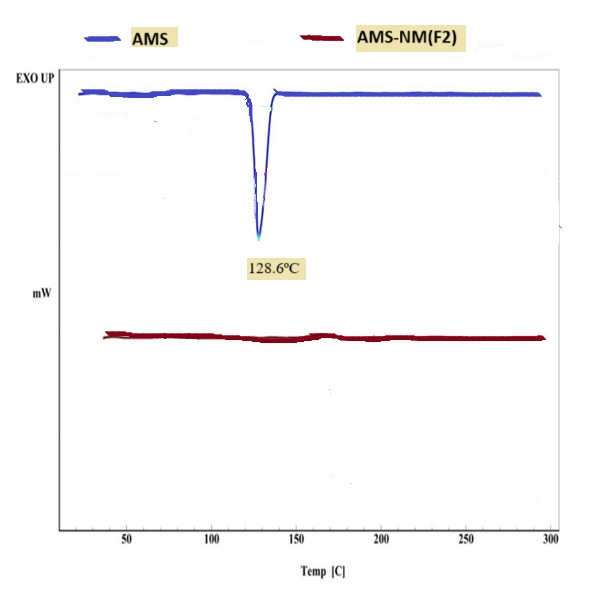

Fig. 6(a, b and c) illustrates the thermal behavior of the pure drug AMS, and the selected formula F2 demonstrated a sharp endothermic peak at 128.6ºC corresponding to the AMS melting point, indicating its purity and anhydrous crystalline structure. The thermogram of the selected formula demonstrates that the endothermic peak of AMS has vanished, which may suggest that the drug is no longer in its crystalline form and is likely entrapped in an amorphous state within the micelle [62, 63].

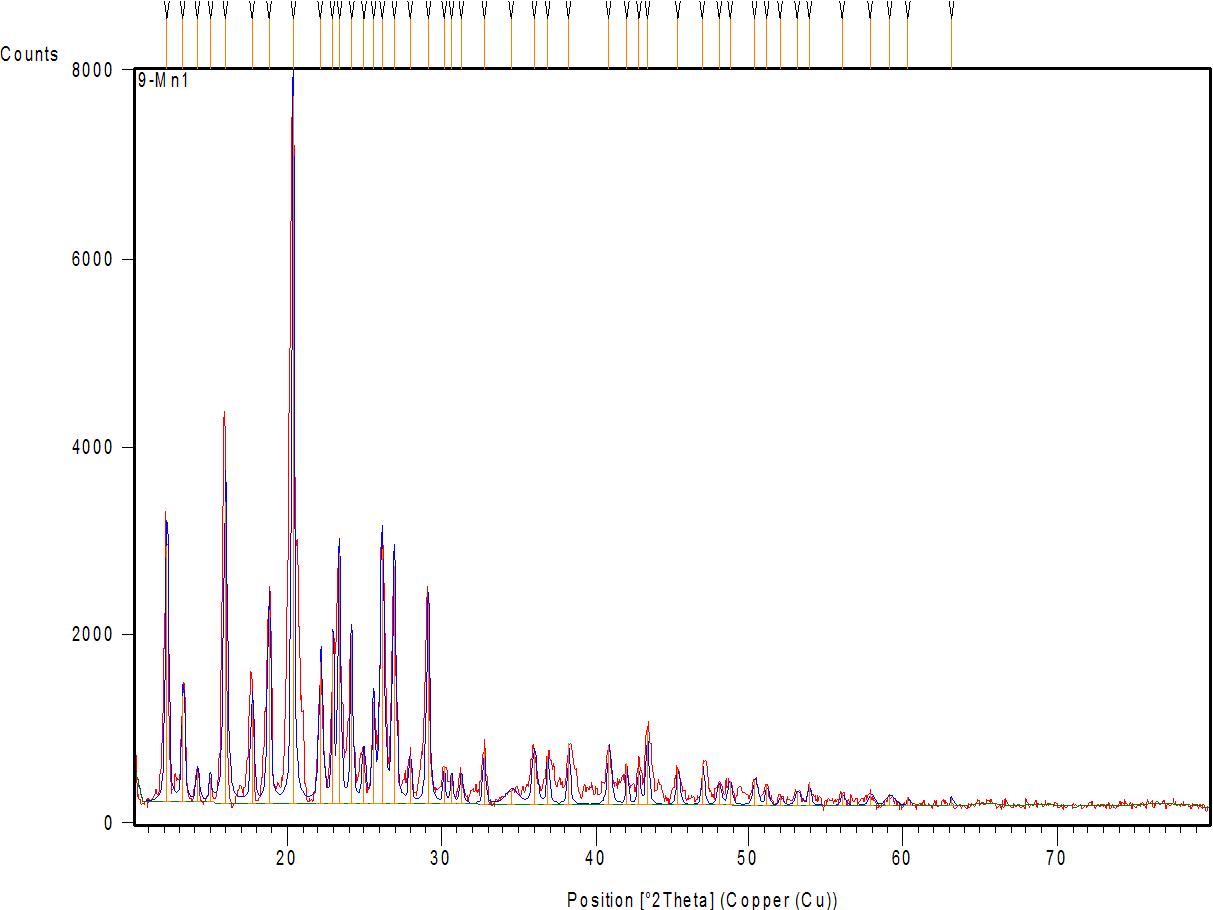

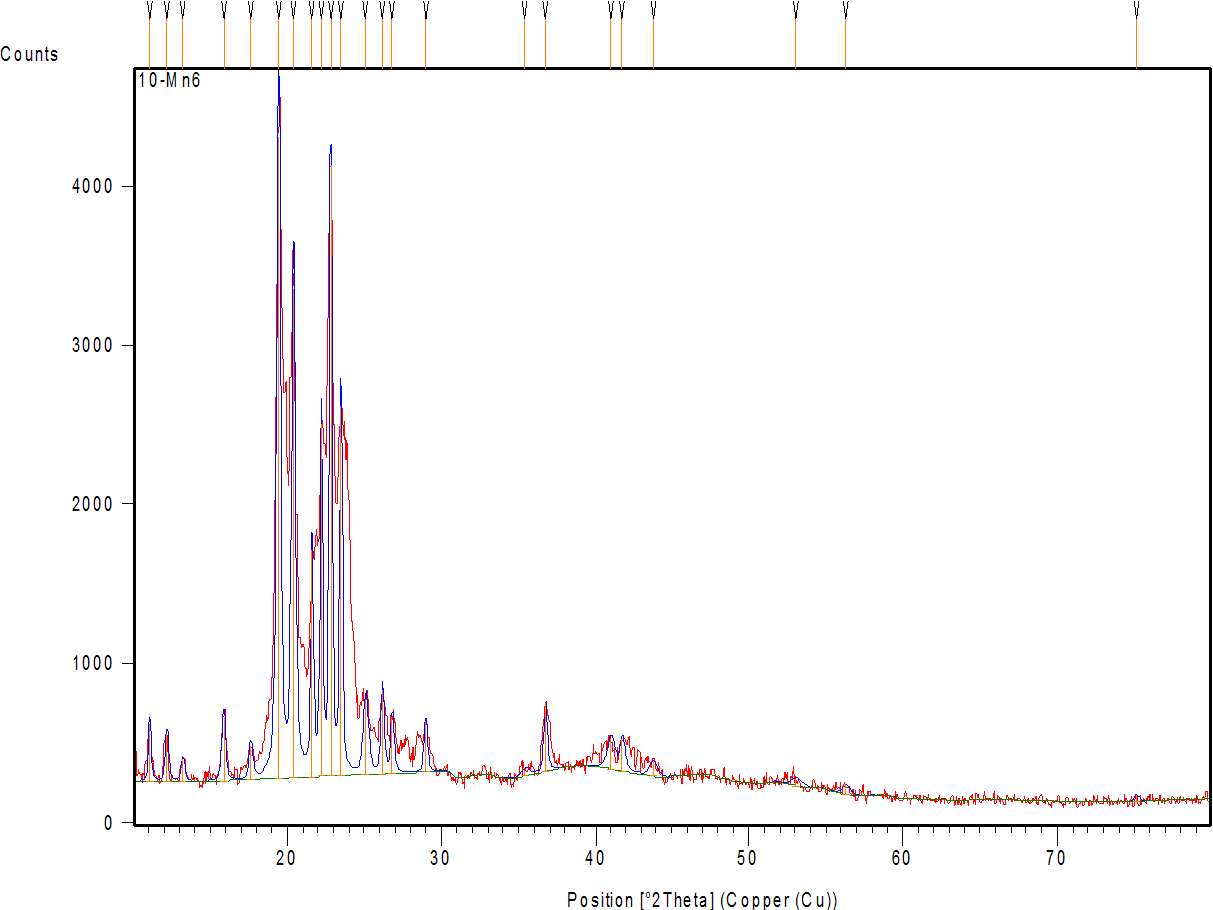

X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD)

Fig. 7a shows the diffractogram of AMS, demonstrating sharp peaks with high intensity at 2θ scattered angles of 12.19, 15.98, 18.81, 20.35, 23.35, 26.13, 26.91, and 29.11°, indicating the highly crystalline nature of the drug. Fig. 7 band c represent the diffractogram of the physical mixture and optimum formula F2, demonstrating the disappearance or reduction of the drug’s crystalline peaks in the XRD pattern of the NM formulation (compared to the pure drug) confirms the loss of crystallinity, supporting the conclusion that the drug is molecularly dispersed or amorphous within the micelle [64].

a b

Fig. 5(aandb). FESEM of optimized AMS-NM (a), and pure AMS powder (b)

a

b

c

Fig. 6(a, b and c): The differential scanning calorimetry of: (a) Amisulpride (pure drug), (b) AMS-NM (F2), and(c) joined thermogram of AMS and AMS-NM (F2)

a

b

c

Fig. 7: X-ray powder diffraction of: (a) AMS-drug powder (b) physical mixture (c) AMS-NM (F2)

Compatibility study by FTIR

The FTIR spectroscopic analysis can determine whether a medicine is compatible with other excipients, an essential factor to consider when choosing the best one. Furthermore, FTIR analysis is a valuable tool for investigating potential structural changes in the drug due to exposure to various complex and demanding conditions during formulation. Fig. 8 shows AMS's FTIR spectra which demonstrate that AMS retains its chemical integrity within the nanomicellar carrier, with characteristic peaks for N–H stretching (~3400–3300 cm⁻¹), C–H stretching (~2920–2870 cm⁻¹), C=O stretching (~1730–1720 cm⁻¹), aromatic C=C stretching (~1630–1590 cm⁻¹), and C–H bending (~1460–1440 cm⁻¹) present in both the pure drug and nanomicellar formulation. The FTIR spectra of AMS-NM (F2) showed no significant shifts in the characteristic AMS bands, confirming successful drug encapsulation without chemical modification. This indicates excellent drug-excipient compatibility and structural integrity, underscoring the formulation’s potential for further development [62, 65].

Fig. 8: FTIR joined spectra of AMS as pure drug and AMS-NM (F2) as an optimized formula

Stability study

The storage stability of the optimized AMS-NM dispersion (F2) was evaluated over three months under two conditions: refrigerated at 4 °C and ambient temperature. Particle size was monitored using a Malvern particle size analyzer, while encapsulation efficiency (EE%) and content% % were determined spectrophotometrically at 279 nm. Additionally, a visual inspection was performed to detect any precipitation of AMS.

The stability data are summarized in table 5 which demonstrates that the P. size and PDI remained consistently low and within the nanoscale range (<100 nm) across all conditions, indicating that the NM maintained their uniform size distribution and colloidal stability after 3 mo of storage at both refrigerated (4 °C) and room temperature (25 °C), as well as upon dilution with water. The clear appearance without precipitation or turbidity further supports the physical stability of the formulation.

The EE% values showed a minimal decrease (from 73% to 70%) after 3 mo at 25 °C, indicating negligible drug leakage or degradation. The drug content remained above 98% in all conditions, confirming excellent chemical stability and preservation of AMS integrity during storage and dilution.

Table 5: Stability parameter of F2 NM-dispersion (means± SD, n=3)

| Storage condition | Average P. size (nm) | PDI | EE% | Appearance | Content % |

| 4 °C after 3 mo | 67.1±2.2 | 0.061±0.002 | 73.03± 3.6 | Clear | 99.9± 0.01 |

| 25 °C after 3 mo | 73.09±3.4 | 0.081± 0.004 | 70.02±2.4 | Clear | 98.01± 0.05 |

| Water dilution stability | 64.0± 1.9 | 0.109± 0.03 | 72.08± 3.4 | Clear | 99.02±0.015 |

Results are expressed as mean±SD, n=3

CONCLUSION

Nanomicellar technology offers a highly effective strategy to overcome the poor aqueous solubility of AMS, significantly enhancing its oral bioavailability potential. The optimized formulation F2, containing 25 mg AMS and 100 mg SLP, demonstrated uniform nanoscale particle size (67.1±2.2 nm) with excellent monodispersity (PDI 0.061±0.002) and a remarkable solubility factor of 4.3 compared to pure AMS. This formulation achieved 100% drug release within 45 min, thereby improving both the rate and extent of dissolution, while maintaining excellent stability, confirming its suitability as a novel and promising oral delivery system for AMS.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Haider Hani Hashim designed the research work, performed the experiment, and analyzed the results. Saba Abdulhadi Jaber contributed to the preparation and revision of the manuscript, providing guidance and monitoring the research outcomes to finalize the paper for submission.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Alobaidy RA, Rajab NA. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of darifenacin HBr as nanoparticles prepared as nanosuspension. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2022;12(2):1-7. doi: 10.25258/ijddt.12.2.00.

Abdulqader AA, Rajab NA. Bioavailability study of posaconazole in rats after oral poloxamer p188 nano-micelles and oral posaconazole pure drug. J Adv Pharm Educ Res. 2023;13(2):140-3. doi: 10.51847/Q59uyvRmY3.

Piazzini V, D Ambrosio M, Luceri C, Cinci L, Landucci E, Bilia AR. Formulation of nanomicelles to improve the solubility and the oral absorption of silymarin. Molecules. 2019;24(9):1688. doi: 10.3390/molecules24091688, PMID 31052197.

Lu Y, Park K. Polymeric micelles and alternative nanonized delivery vehicles for poorly soluble drugs. Int J Pharm. 2013;453(1):198-214. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.08.042, PMID 22944304.

Pepic I, Lovric J, Filipovic Grcic J. How do polymeric micelles cross epithelial barriers? Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;50(1):42-55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.04.012, PMID 23619286.

Shakeri A, Sahebkar A. Opinion paper: nanotechnology: a successful approach to improve oral bioavailability of phytochemicals. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 2016;10(1):4-6. doi: 10.2174/1872211309666150611120724, PMID 26063398.

Center for Biotechnology. Information. PubChem compound summary for CID 2159. Amisulpride; 2025.

Herrstedt J, Summers Y, Jordan K, Von Pawel J, Jakobsen AH, Ewertz M. Amisulpride prevents nausea and vomiting associated with highly emetogenic chemotherapy: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled dose-ranging trial. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(7):2699-705. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4564-8, PMID 30488222.

Kang C, Shirley M. Amisulpride: a review in post-operative nausea and vomiting. Drugs. 2021;81(3):367-75. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01462-1, PMID 33656662.

Guembe Michel N, Nguewa P, Gonzalez Gaitano G. Soluplus®-based pharmaceutical formulations: recent advances in drug delivery and biomedical applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(4):1499. doi: 10.3390/ijms26041499, PMID 40003966.

Sparshatt A, Taylor D, Patel MX, Kapur S. Amisulpride dose plasma concentration occupancy and response: implications for therapeutic drug monitoring. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(6):416-28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01429.x, PMID 19573049.

Musenga A, Mandrioli R, Morganti E, Fanali S, Raggi MA. Enantioselective analysis of amisulpride in pharmaceutical formulations by means of capillary electrophoresis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;46(5):966-70. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.05.022, PMID 17606354.

Schmitt U, Hiemke C, Hirtter S. P-glycoprotein (P-gp) affects the pharmacodynamics and of the atypical antipsychotic amisulpride. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(5):260. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-825503.

Singh S, Negi JS, Bisht R, Negi V, Kasliwal N, Thakur V. Development and evaluation of orodispersible sustained release formulation of amisulpride–γ-cyclodextrin inclusion complex. J Incl Phenom Macrocycl Chem. 2014;78(1-4):239-47. doi: 10.1007/s10847-013-0292-3.

Shi NQ, Lai HW, Zhang Y, Feng B, Xiao X, Zhang HM. On the inherent properties of soluplus and its application in ibuprofen solid dispersions generated by microwave quench cooling technology. Pharm Dev Technol. 2018;23(6):573-86. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2016.1256409, PMID 27824281.

Dian L, Yu E, Chen X, Wen X, Zhang Z, Qin L. Enhancing oral bioavailability of quercetin using novel soluplus polymeric micelles. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2014;9(1):2406. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-9-684, PMID 26088982.

Pignatello R, Corsaro R, Bonaccorso A, Zingale E, Carbone C, Musumeci T. Soluplus® polymeric nanomicelles improve solubility of BCS-class II drugs. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022;12(8):1991-2006. doi: 10.1007/s13346-022-01182-x, PMID 35604634.

Mali KD, Shinde DT, Patil KR. Review on soluplus®: pharmaceuticals revolutionizing drug delivery and formulation strategies. Int J Pharm Investigation. 2025;15(2):344-60. doi: 10.5530/ijpi.20250146.

Alani AW, Rao DA, Seidel R, Wang J, Jiao J, Kwon GS. The effect of novel surfactants and solutol HS 15 on paclitaxel aqueous solubility and permeability across a caco-2 monolayer. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99(8):3473-85. doi: 10.1002/jps.22111, PMID 20198687.

Bergonzi MC, Vasarri M, Marroncini G, Barletta E, Degl Innocenti D. Thymoquinone-loaded soluplus®-solutol® HS15 mixed micelles: preparation in vitro characterization and effect on the SH-SY5Y cell migration. Molecules. 2020;25(20):4707. doi: 10.3390/molecules25204707, PMID 33066549.

Alzalzalee R, Kassab H. Factors affecting the preparation of cilnidipine nanoparticles. IJPS. 2023;32Suppl:235-43. doi: 10.31351/vol32issSuppl.pp235-243.

Salimi A, Sharif Makhmal Zadeh B, Kazemi M. Preparation and optimization of polymeric micelles as an oral drug delivery system for deferoxamine mesylate: in vitro and ex vivo studies. Res Pharm Sci. 2019;14(4):293-307. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.263554, PMID 31516506.

Kontogiannis O, Selianitis D, Perinelli DR, Bonacucina G, Pippa N, Gazouli M. Non-ionic surfactant effects on innate pluronic 188 behavior: interactions and physicochemical and biocompatibility studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):13814. doi: 10.3390/ijms232213814, PMID 36430294.

Al Wiswasi N, Fatima J, Al Gawahri. Brimonidine soluplus nanomicelles: preparation and in vitro evaluation. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2025;34(1):246-55. doi: 10.31351/vol34iss1pp246-255.

Rajab NA, Jawad MS. Preparation and evaluation of rizatriptan benzoate loaded nanostructured lipid carrier using diff erent surfactant/co-surfactant systems. Int J Drug Deliv Technol. 2023;13(1):120-6. doi: 10.25258/ijddt.13.1.18.

Nizar Awish Jassem, Shaimaa Nazar Abd Alhammid. Formulation and evaluation of canagliflozin self-nanomicellizing solid dispersion based on rebaudioside a for dissolution and solubility improvement. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2025;33(4SI):43-56. doi: 10.31351/vol33iss(4SI)pp43-56.

Abed HN, Hussein AA. Ex-vivo absorption study of a novel dabigatran etexilate-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier using non-everted intestinal sac model. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2019;28(2):37-45. doi: 10.31351/vol28iss2pp37-45.

Hekmat A, Attar H, Seyf Kordi AA, Iman M, Jaafari MR. New oral formulation and in vitro evaluation of docetaxel-loaded nanomicelles. Molecules. 2016;21(9):1265. doi: 10.3390/molecules21091265, PMID 27657038.

Wang J, LV F, Sun T, Zhao S, Chen H, Liu Y. Sorafenib nanomicelles effectively shrink tumors by vaginal administration for preoperative chemotherapy of cervical cancer. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021;11(12):3271. doi: 10.3390/nano11123271, PMID 34947619.

Rupp C, Steckel H, Muller BW. Solubilization of poorly water soluble drugs by mixed micelles based on hydrogenated phosphatidylcholine. Int J Pharm. 2010;395(1-2):272-80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.05.025, PMID 20580793.

Bansal KK, Ali AA, Rahman M, Sjoholm E, Wilen CE, Rosenholm JM. Evaluation of solubilizing potential of functional poly(jasmine lactone) micelles for hydrophobic drugs: a comparison with commercially available polymers. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater. 2023;72(16):1272-80. doi: 10.1080/00914037.2022.2090942.

Kakad SP, Bharati YR, Kshirsagar SJ, Dashputre N, Tajanpure A, Kankate RS. Fabrication of amisulpride nanosuspension for nose-to-brain delivery in the potential antipsychotic treatment. Biosci Biotech Res Asia. 2024;21(1):109-21. doi: 10.13005/bbra/3207.

Tamer MA. The development of a brain-targeted mucoadhesive amisulpride-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier. Farmacia. 2023;71(5):1032-44. doi: 10.31925/farmacia.2023.5.18.

Mallappa DP, Chelsea FR, Ratnakar RP, Panchakshari GA, Shivamurthi MV, Uppinangady BS. Development and characterization of mucoadhesive buccal gel containing lipid nanoparticles of triamcinolone acetonide. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 2020;54(3s):s505-11. doi: 10.5530/ijper.54.3s.149.

Lu P, Liang Z, Zhang Z, Yang J, Song F, Zhou T. Novel nanomicelle butenafine formulation for ocular drug delivery against fungal keratitis: in vitro and in vivo study. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2024;192:106629. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2023.106629, PMID 37918544.

Dou J, Zhang H, Liu X, Zhang M, Zhai G. Preparation and evaluation in vitro and in vivo of docetaxel-loaded mixed micelles for oral administration. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2014 Feb 1;114:20-7. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.09.010, PMID 24157590.

Jaber SH. Lasmiditan nanoemulsion-based in situ gel intranasal dosage form: formulation characterization and in vivo. Farmacia. 2023;71(6):1241-53. doi: 10.31925/farmacia.2023.6.15.

Dey NS, Mukherjee B, Maji R, Satapathy BS. Development of linker-conjugated nanosize lipid vesicles: a strategy for cell selective treatment in breast cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2016;16(4):357-72. doi: 10.2174/1568009616666151106120606, PMID 26548758.

Akhtar MS, Mandal SK, Malik A, Choudhary A, Agarwal S, Sarkar S. Nano micelle: novel approach for targeted ocular drug delivery system. Egypt J Chem. 2022;65(12):337-55. doi: 10.21608/ejchem.2022.119133.5359.

Puppala RK, A VL. Optimization and solubilization study of nanoemulsion budesonide and constructing pseudoternary phase diagram. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019;12(1):551. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2019.v12i1.28686.

Sulaiman HT. Soluplus and solutol hs-15 olmesartan medoxomil nanomicelle-based oral fast-dissolving film: in vitro and in vivo characterization. Farmacia. 2024;72(4):794-804. doi: 10.31925/farmacia.2024.4.7.

Pignatello R, Corsaro R, Bonaccorso A, Zingale E, Carbone C, Musumeci T. Soluplus® polymeric nanomicelles improve solubility of BCS-class II drugs. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022;12(8):1991-2006. doi: 10.1007/s13346-022-01182-x, PMID 35604634.

Jassem NA, Alhammid SN. Ex vivo permeability study and in vitro solubility characterization of oral canagliflozin self-nanomicellizing solid dispersion using soluplus ® as a nanocarrier. Acta Marisiensis Seria Medica. 2024;70(2):42-9. doi: 10.2478/amma-2024-0011.

Halah Talal Sulaiman, Nawal A, Rajab. Preparation and characterization of olmesartan medoxomil-loaded polymeric mixed micelle nanocarrier. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2025;33(4SI):89-100. doi: 10.31351/vol33iss(4SI)pp89-100.

Wu MY, Kao IF, Fu CY, Yen SK. Effects of adding chitosan on drug entrapment efficiency and release duration for paclitaxel-loaded hydroxyapatite gelatin composite microspheres. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(8):2025. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15082025, PMID 37631239.

Li S, Liu X, Liang X, Wang X. Dual reduction-sensitive nanomicelles for antitumor drug delivery with low toxicity to normal cells. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2024;7(17):19952-62. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.4c01908.

Ghosh I, Schenck D, Bose S, Ruegger C. Optimization of formulation and process parameters for the production of nanosuspension by wet media milling technique: effect of vitamin E TPGS and nanocrystal particle size on oral absorption. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2012;47(4):718-28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.08.011, PMID 22940548.

Ahmed TA, El Say KM, Ahmed OA, Aljaeid BM. Superiority of TPGS-loaded micelles in the brain delivery of vinpocetine via administration of thermosensitive intranasal gel. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:5555-67. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S213086, PMID 31413562.

Mod Razif MR, Chan SY, Widodo RT, Chew YL, Hassan M, Hisham SA. Optimization of a luteolin-loaded TPGS/poloxamer 407 nanomicelle: the effects of copolymers hydration temperature and duration and freezing temperature on encapsulation efficiency, particle size and solubility. Cancers. 2023;15(14):3741. doi: 10.3390/cancers15143741, PMID 37509402.

Szafraniec J, Antosik A, Knapik Kowalczuk J, Chmiel K, Kurek M, Gawlak K. The self-assembly phenomenon of poloxamers and its effect on the dissolution of a poorly soluble drug from solid dispersions obtained by solvent methods. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(3):130. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11030130, PMID 30893859.

Gerardos AM, Balafouti A, Pispas S. Mixed copolymer micelles for nanomedicine. Nanomanufacturing. 2023;3(2):233-47. doi: 10.3390/nanomanufacturing3020015.

Attia MS, Elshahat A, Hamdy A, Fathi AM, Emad Eldin M, Ghazy FE. Soluplus® as a solubilizing excipient for poorly water-soluble drugs: recent advances in formulation strategies and pharmaceutical product features. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2023 Jun;84:104519. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2023.104519.

Yassin AE, Massadeh S, Alshwaimi AA, Kittaneh RH, Omer ME, Ahmad D. Tween 80-based self-assembled mixed micelles boost valsartan transdermal delivery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;17(1):19. doi: 10.3390/ph17010019, PMID 38256853.

Ding Y, Ding Y, Wang Y, Wang C, Gao M, Xu Y. Soluplus®/TPGS mixed micelles for co-delivery of docetaxel and piperine for combination cancer therapy. Pharm Dev Technol. 2020;25(1):107-15. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2019.1679834, PMID 31603017.

Woodhead JL, Hall CK. Encapsulation efficiency and micellar structure of solute-carrying block copolymer nanoparticles. Macromolecules. 2011;44(13):5443-51. doi: 10.1021/ma102938g, PMID 21918582.

Bernabeu E, Gonzalez L, Cagel M, Moretton MA, Chiappetta DA. Deoxycholate-TPGS mixed nanomicelles for encapsulation of methotrexate with enhanced in vitro cytotoxicity on breast cancer cell lines. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2019;50:293-304. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.01.041.

Muhannad Salah, Luay Radhi, Mohammed Al Lami. Preparation and characterization of diazepam-loaded nanomicelles for pediatric intravenous dose adjustment. IJPR. 2020;13(1):2275-86. doi: 10.31838/ijpr/2021.13.01.361.

Li X, Zhang Y, Fan Y, Zhou Y, Wang X, Fan C. Preparation and evaluation of novel mixed micelles as nanocarriers for intravenous delivery of propofol. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6(1):275. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-275, PMID 21711808.

Gohar S, Iqbal Z, Nasir F, Khattak MA, E Maryam G, Pervez S. Self-assembled latanoprost-loaded soluplus nanomicelles as an ophthalmic drug delivery system for the management of glaucoma. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):27051. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-78244-2, PMID 39511270.

Kaur M, Rathee A, Krishna V, Nagpal M. Soluplus-based polymeric micelles: a promising carrier system for challenging drugs. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2024;84(9):83-93. doi: 10.47583/ijpsrr.2024.v84i09.014.

Saba Abdulhadi Jaber, Nawal Ayash Rajab. Preparation and in vitro/ex vivo evaluation of nanoemulsion-based in situ gel for intranasal delivery of lasmiditan. IJPS. 2024;33(3):128-41. doi: 10.31351/vol33iss3pp128-141.

Tamer MA, Kassab HJ. Optimizing intranasal amisulpride loaded nanostructured lipid carriers: formulation development and characterization parameters. Pharm Nanotechnol. 2025;13(2):287-302. doi: 10.2174/0122117385301604240226111533, PMID 40007188.

Sukamporn P, Baek SJ, Gritsanapan W, Chirachanchai S, Nualsanit T, Rojanapanthu P. Self-assembled nanomicelles of damnacanthal loaded amphiphilic modified chitosan: preparation, characterization and cytotoxicity study. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017 Aug 1;77:1068-77. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.263, PMID 28531980.

Rathee A, Solanki P, Emad NA, Zai I, Ahmad S, Alam S. Posaconazole-hemp seed oil loaded nanomicelles for invasive fungal disease. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):16588. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-66074-1, PMID 39025925.

Dino SF, Edu AD, Francisco RG, Gutierrez E, Crucis P, Lapuz AM. Drug excipient compatibility testing of cilostazol using FTIR and DSC analysis. Philipp J Sci. 2023;152(6A):2129-37. doi: 10.56899/152.6A.08.