Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 312-324Original Article

DESIGN OF NABUMETONE-LOADED TEMPERATURE-RESPONSIVE GEL FOR COLORECTAL DELIVERY USING LIPID NANOCARRIERS IN VITRO/IN VIVO EVALUATION

MOHAMMED A. AMIN1, MOSTAFA A. MOHAMED2,3, DALIA A. GABER2*

1Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, Qassim University, Qassim-51452, Saudi Arabia. 2Clinical Pharmacy Program, College of Health Sciences and Nursing, Al-Rayan National College, Madina, Saudi Arabia. 3Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, Al-Ahram Canadian University, Egypt

*Corresponding author: Dalia A. Gaber; *Email: d.gaber1900@gmail.com

Received: 02 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 21 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to develop a novel thermosensitive in situ gel incorporating nabumetone-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (NAB-SLP-TSG) for rectal delivery to enhance bioavailability and sustain drug retention.

Methods: NAB-SLPs were prepared and optimized using Central Composite Design and evaluated for particle size, encapsulation efficiency, surface charge, and morphology. The optimized SLPs were incorporated into a temperature-sensitive gel and characterized for gelation behavior, rheology, mucoadhesiveness, in vitro drug release, pharmacokinetics, rectal mucosal safety, and retention.

Results: Optimized NAB-SLPs demonstrated an encapsulation efficiency of 89.62±1.34%, drug loading of 14.85±1.13%, mean particle size of 161.43±2.17 nm, PDI of 0.29±0.07, and zeta potential of −20.45±0.63 mV. FTIR and XRD confirmed drug encapsulation and its amorphous dispersion in the lipid matrix. The NAB-SLP-TSG exhibited a gelation temperature of 32.81±0.73 °C, gelation time of 15.32±2.37 s, and mucoadhesive strength of (11.09±0.42)×10² dyne/cm². In vitro, a biphasic release profile was observed. In vivo, the formulation significantly enhanced NAB absorption and bioavailability without causing rectal tissue irritation, while ensuring prolonged local retention.

Conclusion: Unlike previously reported thermosensitive rectal gels for drugs like diclofenac or insulin, this formulation uniquely combines γ-Polyglutamic acid (γ-PGA) to significantly enhance mucoadhesion and solid lipid nanoparticles (SLPs) to sustain rectal retention. This dual approach distinctly advances prior systems by improving both residence time and systemic availability of nabumetone, offering a novel and superior alternative for rectal NSAID delivery.

Keywords: Thermoresponsive gel, Nabumetone, Solid lipid nanoparticles, Rectal administration, Enhanced bioavailability

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55367 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

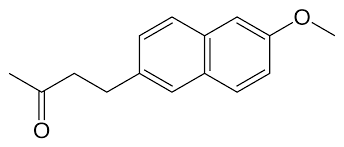

Nabumetone (NAB)-as shown in fig. 1-is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and a nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor, providing potent analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic effects after oral, topical, parenteral, and colorectal administration. NAB is commonly prescribed for managing rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatism, myalgia, gout, neuralgia, radiculitis, ankylosing spondylitis, injury-related inflammation, and fever [1].

However, NAB is classified as a Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS) Class II drug, characterized by low aqueous solubility and high permeability. NAB exhibits poor gastrointestinal (GI) absorption due to its low solubility (~<0.01 mg/ml at 25 °C), leading to limited bioavailability. Additionally, NAB undergoes rapid hepatic metabolism with a serum half-life of only 1–2 h, requiring frequent dosing (3–5 times daily) to maintain effective plasma levels.

Compared to conventional NSAIDs such as diclofenac and ibuprofen, nabumetone possesses a distinct advantage due to its non-acidic prodrug nature, which significantly reduces the risk of direct gastrointestinal irritation [2, 4]. This lower gastric toxicity profile, combined with its poor aqueous solubility, makes NAB particularly suitable for rectal delivery, offering the potential to bypass gastrointestinal degradation while minimizing local and systemic GI-related side effects.

The rectal route offers several benefits, including partial avoidance of hepatic first-pass metabolism, improved bioavailability, and reduced upper GI side effects [3]. However, traditional rectal dosage forms like suppositories are often associated with patient discomfort, mucosal irritation, and poor retention, while enemas suffer from leakage issues.

Thermosensitive in situ gels have emerged as an effective alternative, transforming from liquid to gel at body temperature to enhance retention and patient compliance. Previous studies have applied this approach to various drugs, including diclofenac, insulin, indomethacin, and propranolol. Nonetheless, there remains a critical need to improve mucosal adhesion and sustain drug release for poorly water-soluble drugs like NAB.

This study introduces a novel strategy by combining solid lipid nanoparticles (SLPs) to enhance solubility and protect the drug with γ-Polyglutamic acid (γ-PGA), a biodegradable polymer that provides superior mucoadhesiveness. This dual-function approach distinctly differentiates our formulation from earlier thermosensitive rectal gels, enabling prolonged retention, improved drug absorption, and minimized local irritation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report employing a NAB-SLP thermoresponsive gel enhanced with γ-PGA for rectal delivery.

The objective of this work was to develop and characterize a thermosensitive NAB-SLP-TSG system for rectal delivery, evaluating its physicochemical properties, mucoadhesion, in vitro release, in vivo pharmacokinetics, and rectal mucosal safety [5].

Fig. 1: Chemical structure of nabutamone4-(6-methoxy-2-naphthyl) butan-2-one

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Nabumetone (NAB, purity 99.9 %) was ordered from Saudi Arabian Japanese Pharmaceutical Company Ltd. Palmitic acid and sorbitan monostearate were ordered from SAJA Pharmaceuticals, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Jamjoom Pharma in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia supplied γ-Polyglutamic acid. Poloxamer 408 and Poloxamer 177 were obtained from BASF in Ludwigshafen, Germany. Deionized water was used with Millipore™ VR purifier. Tween 80 was supplied by Arabian Chemical Company Ltd. (Gulf Chlorine), Jubail, Saudi Arabia. HPLC-grade acetonitrile and methanol were purchased from Fisher Scientific. All other employed chemicals and solvents were of analytical grade [6, 11].

Methods

Preparation of nabumetones-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (NAB-SLPs)

Hot homogenization method was used for preparing NAB loaded SLPs. NAB was integrated into a structure of palmitic acid (PA) and sorbitan monostearate (SMS) as Lipid matrices in a 65 °C water bath.[29] At the same time, emulsifying agent Tween 80 was dissolved in distilled water at 65 °C to prepare the aqueous component. Afterward, the water phase was slowly added to the oil phase and the mixture was stirred with a Hei-TORQUE Precision 200 at 1000 rpm for 15 min in a 65 °C water bath. After forming the primary emulsion, the emulsion underwent processing with a sonicator (Hielscher UP400St, Germany) for 15 min the formed nanoemulsion obtained above was instantly stirred while cooling at ice temperature for 10 min to allow the lipid crystal SLP colloid to form. Characterization using SEM, XRD and FTIR was done to NAB-loaded SLP's after the SLP's were first freeze-dried using a lyophilizer (Labconco Free Zone 2.5, USA). In the lyophilizer chamber, the freeze-drying process began with the initial freezing stage of −55 °C for 48 h, followed by a first stage of desiccation at −40 °C for 24 h and a secondary drying phase at 10 °C 50 for 8 h. Trehalose (5% w/v) was incorporated as a cryoprotectant prior to lyophilization to prevent nanoparticle aggregation and preserve particle integrity during freeze-drying. The full detailed composition of NAB-SLPs is shown in table 1.

Optimizations of nabumetones-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (NAB-SLPs)

The formed NAB-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (SLPs) were progressively optimized using Central Composite Design (CCD) via Minitab 20 software. Preliminary screening experiments identified three key formulation factors influencing drug entrapment and loading efficiency: the amounts of palmitic acid (Factor A), sorbitan monostearate (Factor B), and the non-ionic emulsifier Tween 80 (Factor C). Following the CCD matrix, 18 experimental formulations were prepared and evaluated based on multi-response criteria: encapsulation efficiency (%) (EE%, Z1), drug loading (DL, Z2), mean particle size (PZ, Z3), polydispersity index (PDI, Z4), and zeta potential (ZP, Z5), as detailed in table 2. Statistically validated models (p<0.05) were applied to generate response surface equations [7]. However, several predictors for particle size and zeta potential were found to be statistically non-significant, which compromises the overall robustness of the CCD model. To enhance model accuracy and predictive power, these models should be refined using stepwise regression or variable selection techniques. The optimization objective was to maximize EE% and DL while minimizing particle size, polydispersity, and zeta potential.

Physicochemical properties of NAB-SLPS

Particle size, zeta potential, and polydispersity index

Primary measurements of NAB-SLP droplets’ average diameter with respect to volume, and the corresponding PDI were studied at 25 °C at detection angle 90°. Measurements were performed after a 30-second equilibration period (holding step) using the dynamic light scattering method and a SZ-100 analyzer (Malvern Panalytical, UK) equipped with a Diode Laser 635 nm [20]. During each measurement, 100 μl of NAB-SLPs suspension was diluted to a quantity of 2 ml with deionized water and sonicated to enhance the optical scattering conditions [38]. The same method was employed to determine zeta potential or the surface charge of NAB-SLPs. These measurements were done in triplicate and represented as mean (m)±standard deviation (SD).

Table 1: Factors and their corresponding levels in the central composite design

| Levels | |||

| -1 | 0 | 1 | |

Independent Variables A= Amount of Palmitic acid (g) B= Amount of Sorbitan Monostearate (g) C=Amount of Tween 80 (g) |

|||

| 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | |

| 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | |

| 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | |

Dependent variables Z1 = Encapsulation efficiency Z2 = Drug Loading Z3 = mean particle size Z4 = Polymer dispersity index Z5 = zeta potential |

Controls Increase Increase Decrease Decrease Decrease |

||

Encapsulation efficiency (EE%) and drug loading (DL)

The evaluation of NAB incorporation and holding within SLPs was studied using centrifugation. Initially, 200 μl of the NAB-SLP formulation was blended with 500 μl of deionized water in a centrifuge-compatible ultrafiltration tube (Millipore (Merck) 10 kDa; USA). Each sample was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4 °C using an Eppendorf 4000 R centrifuge [8, 9]. The resulting filtrate was then diluted with methanol and labeled as W0. For determining the total NAB content, 0.5 ml of the NAB-SLP preparation was combined with 2 mL of methanol and sonicated for 30 minutes to fully release the encapsulated drug; this sample was marked as Wf. All test solutions were passed through a 0.22 μm filter and examined with a Waters Alliance HPLC system to quantify NAB levels. The percentage of drug entrapment was calculated using a standard formula:

HPLC analysis of NAB

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) technique was utilized to determine the amount of NAB present in the sample. The system configuration included A Thermo Scientific UltiMate™ 3000 HPLC system was employed for the chromatographic analysis. The system included a LPG-3400SD quaternary pump, WPS-3000 autosampler, TCC-3000RS column oven, and a DAD-3000RS diode array detector. Chromatographic data acquisition and processing were performed using Chromeleon™ 7.2 software [25]. Separation was carried out on a Hypersil GOLD™ C18 column (4.6×250 mm, 5 µm). The detection of Nabumetone was performed at a wavelength of 331 nm, corresponding to its maximum UV absorbance. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and phosphate buffer (pH adjusted to 3.0 with orthophosphoric acid) in a ratio of 60:40 (v/v), delivered at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The injection volume was 20 µl, and the column temperature was maintained at 30 °C. The total run time was 10 min, and the retention time of NAB was approximately 6.2 min. A strong linear relationship was observed between peak area and concentration, described by the linear regression equation: y = 523.41x – 3125.7 (R² = 0.9991), where x is the concentration in µg/ml and y is the peak area. The method demonstrated linearity in the range of 2.0–200 µg/ml, with a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.6 µg/ml [31].

Table 2: Central composite design: impact of formulation variables on EE, DL, MPZ, PDI, and ZP"

| Run | A (g) | B (g) | C (g) | Z1 (%) | Z2 (%) | Z3 (nm) | Z4 | Z5 (Mv) |

| 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 88.60 | 65.2 | 170.23 | 036 | -23.5 |

| 2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 87.52 | 30.1 | 113.25 | 0.63 | -33.5 |

| 3 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 84.65 | 46.8 | 100.24 | 0.28 | -28.6 |

| 4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 78.88 | 66.5 | 192.23 | 0.51 | -25.7 |

| 5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 85.45 | 48.9 | 110.23 | 0.45 | -21.5 |

| 6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 87.20 | 61.2 | 112.25 | 0.48 | -18.9 |

| 7 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 83.59 | 57.5 | 111.85 | 0.49 | -14.9 |

| 8 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 87.42 | 69.2 | 285.35 | 0.68 | -24.8 |

| 9 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 90.89 | 69.6 | 222.35 | 0.66 | -16.9 |

| 10 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 85.34 | 57.3 | 189.32 | 0.48 | -22.47 |

| 11 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 74.69 | 60.8 | 178.25 | 0.81 | -19.54 |

| 12 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 79.14 | 69.3 | 156.85 | 0.42 | -20.54 |

| 13 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 81.64 | 65.9 | 312.25 | 0.86 | -23.85 |

| 14 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 82.29 | 40.4 | 175.25 | 0.54 | -19.32 |

| 15 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 88.73 | 39.8 | 209.65 | 0.56 | -20.47 |

| 16 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 87.04 | 45.6 | 215.69 | 0.54 | -19.87 |

| 17 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 81.50 | 58.7 | 165.85 | 0.42 | -20.18 |

| 18 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 87.5.10 | 61.8 | 168.5 | 0.48 | --22.7 |

Scanning electron microscope

The morphology and surface characteristics of NAB and NAB-SLPs were examined using a JEOL JSM-IT500 scanning electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) operating at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. The lyophilized NAB-SLPs were affixed to an aluminum stub using carbon conductive tape and then sputter-coated with gold in a vacuum under an inert argon environment prior to imaging [34].

X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD)

X-ray diffraction analysis was conducted to explore the crystallinity and solid-state nature of the developed formulations. Pure NAB, lipid, their physical admixture, freeze-dried blank particles, and lyophilized NAB-loaded SLPs were subjected to analysis to detect any alterations in the crystal structure. The measurements were performed at ambient temperature using a Rigaku MiniFlex 600 diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Japan), employing a Cu-Kα X-ray source operating at 40 kV and 30 mA. Data were acquired across a 2θ range of 3° to 60°, with a step size of 0.010° and a scan speed of 0.1° per second.

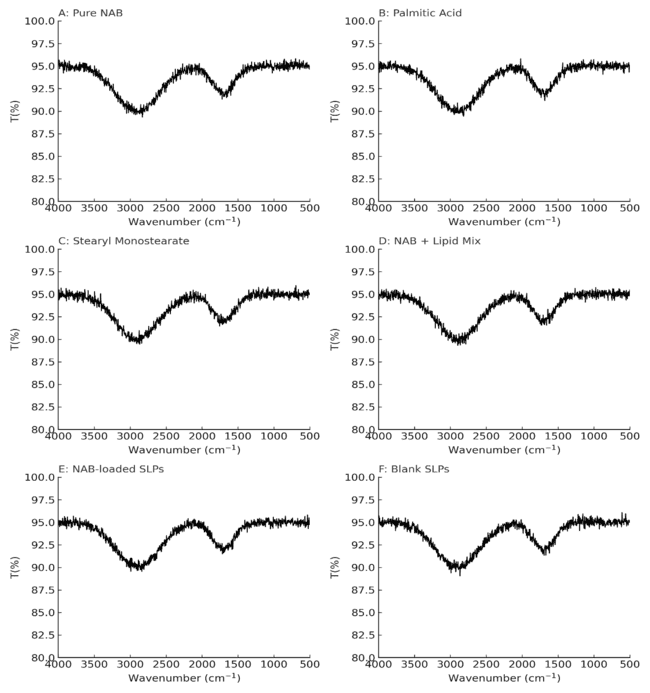

Fourier transform infrarer (FTIR) spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were recorded to evaluate possible intermolecular interactions and chemical stability of the formulations. A Thermo Nicolet iS50 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was utilized, scanning within the wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹. Each sample was finely pulverized in an agate mortar and thoroughly mixed with KBr at a 1:20 (w/w) ratio. The mixture was compressed into a thin disc for spectral acquisition [20].

Preparation of temperature-responsive gel (TSG)

In this investigation, a thermosensitive in-situ gel formulation based on weight/volume was developed using a modified cold technique, similar to the procedure outlined by Choi et al. The formulation incorporated optimized NAB-SLPs at a concentration of 4 mg/ml. Briefly, 18% poloxamer 408 (w/w) and 10% poloxamer 177 (w/w) were incrementally introduced into the cold NAB-SLPs dispersion, maintained at 4 °C, with intermittent mixing until complete dissolution was achieved. Subsequently, 0.5% γ-Polyglutamic acid(w/w) was quantitatively added under continuous stirring until a uniform gel-like system free of aggregates was formed, the pH of the final gel was adjusted between 6.5 and 7.8, then stored at 4 °C until further use, resulting in the preparation of NAB-SLP-TSG (table 3).

Additionally, a plain nabumetone in-situ gel (NAB-TSG) was prepared using the same approach, without the lipid particles, for comparative evaluation in in vitro and in vivo studies. The required quantities of P408, P177, and γ-polyglutamic acid were dispersed in cold ultra-purified water at 4 °C, kept refrigerated, and stirred periodically until fully hydrated. The appropriate amount of Nabumetone was then incorporated to obtain a homogeneous NAB-TSG formulation [19, 23].

Table 3: NAB-SLP gel properties of the formulation

| Formulation | P408/P177 (%, w/w) | Drug form | Gelation temperature (°C) | Gelation time (s) | Gel strength (g/cm²) | Bio adhesive force (×10² dyne/cm²) |

| NAB-SLP-TSG1 | 15%/5% | SLPs | 31.85±0.60 | 18.25±2.10 | 40.75±1.48 | 10.15±0.29 |

| NAB-SLP-TSG2 | 15%/8% | SLPs | 32.95±0.85 | 16.80±1.50 | 52.20±1.25 | 11.80±0.41 |

| NAB-TSG1 | 16%/6% | NAB | 34.80±0.72 | 37.50±1.30 | 27.20±3.10 | 6.45±0.95 |

| NAB-TSG2 | 16%/6% | NAB | 35.10±2.30 | 35.90±1.30 | 32.60±2.90 | 7.85±0.60 |

Note: 0.2% γ-Polyglutamic acid was added to each formulation. Abbreviations: SLPs, solid lipid nanoparticles; NAB, pure drug, (X±SD, n=3).

Characterization of temperature-responsive gel (TRG)

Determination of gelation temperature and gelation time

The gelation temperature and time were evaluated using the magnetic stirring bar technique. A clear vial containing a magnetic stirring bar and 10 ml of the thermosensitive gel was placed in a programmable low-temperature magnetic stirrer system (model XYZ-123). A digital temperature probe connected to a thermistor was immersed directly in the gel solution. The gel was gradually heated at a controlled rate of 1–2 °C per minute with continuous stirring at 50 rpm. The temperature at which the magnetic bar ceased movement, indicating gelation, was recorded as the gelation temperature. For gelation time measurement, a vial with 10 ml of the formulation and a magnetic bar was immersed in a water bath maintained at 37 °C and stirred continuously at 50 rpm. The gelation time was noted as the time point when the magnetic bar stopped moving due to gel formation. Results for gelation temperature and time are averages from three independent trials [30].

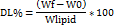

Assessment of gel strength

Gel strength was measured following the procedure described by Chio et al. The formulation (50 g) was transferred into a 100-mL graduated cylinder and incubated at 34 °C to allow gelation. A standardized weight apparatus (35 g) was gently placed on the gel surface. The gel strength was defined by the time (in seconds) the apparatus took to penetrate 5 cm into the gel. If the apparatus required longer than 300 sec to reach this depth, incremental weights were added on top of the apparatus until penetration was achieved. The minimal weight required to push the apparatus 5 cm into the gel was recorded as gel strength. The apparatus setup is illustrated in fig. 2.

Measurement of bioadhesive force

The adhesive strength of the in-situ gel was quantified using a modified muco-adhesion apparatus. Fresh porcine rectal mucosa was secured onto two glass vials. The vials were equilibrated at 32–34 °C for 10 min to maintain a mucosal surface temperature near 33 °C, preventing excess hydration of the gel during measurement [48]. One vial was attached to a balance, and 0.5 ml of the gel was sandwiched between the two mucosal surfaces. The bio-adhesive force, expressed as detachment stress (dyne/cm²), was calculated from the smallest weight needed to separate the two vials.

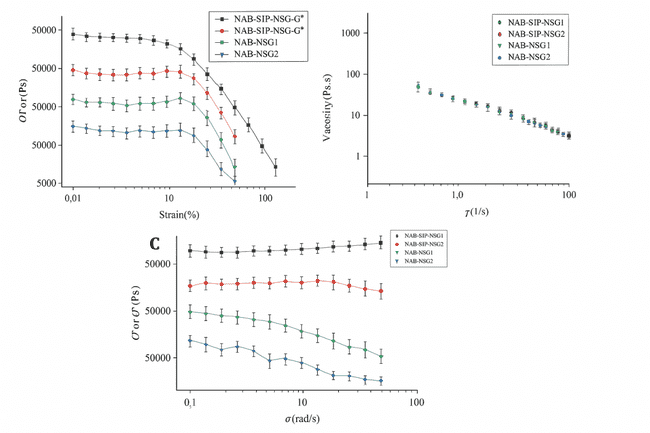

Evaluation of rheological properties

Rheological characteristics of NAB-loaded solid lipid nanoparticle in situ gel (NAB-SLP-TSG) and NAB in situ gel (NAB-TSG) were studied at 37 °C using a rotational rheometer (MCR 302, Anton Paar, Austria) equipped with a 50 mm diameter plate and a cone angle of 4°. Approximately 1.2 g of sample was placed on the rheometer plate and allowed to equilibrate for 60 sec to remove any artifacts caused by sample loading and to stabilize the temperature. Subsequently, the elastic (storage) modulus and viscous (loss) modulus of the gels were measured isothermally at 37 °C by applying a shear rate range of 0–100 s⁻¹. Amplitude sweep and frequency sweep tests were conducted to monitor changes in moduli and angular frequency versus strain. Viscosity was also measured at 37 °C at a constant shear rate of 100 s⁻¹, reflecting physiological conditions [47].

Fig. 2: Diagram shows the method of measuring gel strength

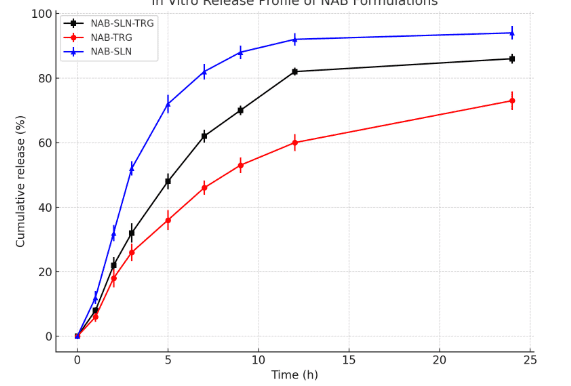

In vitro drug release

To evaluate the in vitro drug release profile, release experiments were performed using the Franz diffusion cell technique with excised porcine rectal membranes, which are more physiologically relevant compared to artificial membranes. The previously used dialysis tubing (12–14 kDa) was replaced due to its limited in vivo correlation for rectal mucosa. A 5 ml aliquot of each formulation was placed in the donor compartment of the Franz cell, and the receptor compartment was filled with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 6.8) containing 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to enhance the solubility of nabumetone and maintain sink conditions. The system was maintained at 37±0.5 °C with continuous stirring. At predetermined time points, 1 ml samples were withdrawn from the receptor compartment and immediately replaced with an equal volume of fresh buffer to maintain a constant volume [26, 28]. The NAB concentration in the collected samples was quantified via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) after filtering through a 0.45 μm membrane filter. All measurements were conducted in triplicate.

To elucidate the drug release mechanism from the mucoadhesive in situ gels, both with and without lipid incorporation, the release data were subjected to analysis using widely recognized kinetic models, such as zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, and Ritger–Peppas models. These mathematical models are commonly used to characterize drug release behavior from polymeric delivery systems. The release kinetics of nabumetone from the solid lipid nanoparticle-loaded in situ gel were determined by fitting the experimental results to these model equations [22].

Log (Mt/M ) = log k+n log t

) = log k+n log t

The expression Mt/M∞ denotes the proportion of drug released at a given time t. In this equation, is a formulation-specific constant, and nis an exponent that indicates the mode of drug release. A greater k value implies a quicker release rate n value of 1 represents zero-order kinetics. When n lies between 0.5 and 1, it suggests a non-Fickian (anomalous) diffusion mechanism, whereas a value of 0.5 signifies Fickian diffusion, in alignment with the Higuchi model [50].

Pharmacokinetic study

Animals studies

The rectal safety assessment was limited to gross examination without histopathological confirmation. Hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining of rat rectal tissues should be conducted to evaluate potential submucosal inflammation or necrosis. Also lacking is any discussion of gel manufacturability, sterilization method, or stability data-all critical for clinical translation. Eighteen male Long-Evans rats, each weighing 280±15 g, were selected for the experiment and randomly assigned to three groups: NAB-SLP-IGS, NAB-IGS, and NAB suppository. The animals were fasted 24 h prior to treatment, with water available ad libitum. Rats were anesthetized using an ether chamber, placed supine on a surgical table, and fixed using a thread. A polyethylene catheter was inserted into the right femoral artery for blood sampling. The rectal dose of 30 mg/kg NAB used in rats corresponds to a human equivalent dose of approximately 180 mg, which is significantly lower than the clinically administered dose of 500–1000 mg.[46]A justification for this dose selection should be provided, or dose scaling based on allometric principles must be applied to improve translational relevance. The formulations NAB-SLP-IGS and NAB-IGS, both containing 30 mg/kg NAB, were administered rectally using stomach tubes affixed to glass syringes, delivering the drug to a 4 cm depth from the rectal entry point.

Subsequently, a solid suppository formulation containing NAB was administered at an equivalent dose of 0.56 g/kg (30 mg/kg NAB), using the same depth. To prevent formulation expulsion, the anus was sealed using cyanoacrylate adhesive. Despite claims of localized rectal retention, no imaging evidence (e.g., radiography or fluorescence tracking) was provided to confirm in vivo gel retention. Future studies should incorporate such imaging modalities to substantiate localized delivery. Additionally, the pharmacokinetic comparison between NAB-SLP-IGS and NAB-IGS lacks statistical validation. Key indicators such as p-values or confidence intervals should be reported to support the significance of observed differences [32, 33]. Blood samples (0.2 ml) were collected from the femoral artery at predefined time intervals (5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 240, and 360 min) into anticoagulant-treated tubes. Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 10 min and stored at −20 °C until analysis.

Blood sample analysis

A 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube was filled with an aliquot of 50 μl of each plasma sample, 10 μl of the internal standard solution (piroxicam, 130 ng/ml), and 200 μl of acetonitrile. To aid in protein precipitation, the mixture was vortexed for a short while before being centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 rpm. After the solution was created, 200 μl of the clear supernatant was moved to a new tube and allowed to evaporate at 30 °C under nitrogen gas. Once more, the residue was dissolved in 100 μl of the mobile phase, vortexed for one minute, and centrifuged for ten minutes at 13,000 rpm. To be analyzed, the last supernatant was added to the UPLC-MS apparatus [39].

UPLC–MS/MS method for the quantification of nabumetonein plasma

Nabumetone (NAB) levels in rat plasma were quantitatively determined using a Waters ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) coupled with a Thermo Scientific TSQ Endura triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, operating under negative electrospray ionization (ESI−) mode. Chromatographic separation was carried out on a reverse-phase C18 analytical column (50 mm×2.1 mm, 1.7 µm particle size), maintained at a constant temperature of 35 °C [38]. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (aqueous phase A) and acetonitrile (organic phase B), delivered at a flow rate of 0.35 ml/min following a programmed gradient elution. The gradient started with 5% phase B from 0.00 to 0.10 min, gradually increasing to 75% from 0.11 to 2.00 min, then maintained at 75% until 2.80 min. Subsequently, the composition was reduced to 50% B by 3.50 min, followed by a further decrease to 25% B until 4.00 min. The system was re-equilibrated at 5% B until the end of the run at 5.00 min. Detection was performed in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The transition monitored for NAB was m/z 205.0 to 161.0, while the internal standard (ketoprofen) was monitored at m/z 253.0 to 209.0. The collision energies were optimized at −15 V for NAB and −20 V for the internal standard, with declustering potentials set at −110 V and −95 V, respectively. The ionization source conditions included a curtain gas pressure of 25 psi, nebulizer gas (GS1) at 50 psi, auxiliary gas (GS2) at 55 psi, and an ion source temperature of 550 °C. The spray voltage was set to −3200 V. Under these optimized conditions, NAB and the internal standard exhibited retention times of approximately 1.76 min and 1.82 min, respectively. The analytical method demonstrated good linearity within the concentration range of 0.005 to 80 µg/ml, with a correlation coefficient (r²) of 0.9965. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was established at 0.05 µg/ml [38, 45]. The average extraction recovery for NAB was 91.2±8.5%, while that for the internal standard was 93.1±9.2%. Intra-day precision remained below 12% at the LLOQ and under 8% for higher concentration levels. Inter-day precision values for low, medium, and high concentration quality control samples were 13.5%, 10.9%, and 10.3%, respectively, indicating acceptable reproducibility and reliability for pharmacokinetic applications.

Pharmacokinetic evaluation

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated based on the plasma concentration-time data obtained from the validated UPLC–MS/MS method. Calibration curves were constructed for each analytical batch and used to determine NAB concentrations in plasma samples. Data analysis was conducted using Phoenix WinNonlin software (version 8.3, Certara, USA). The maximum observed plasma concentration (Cₘₐₓ) and the time to reach this concentration (Tₘₐₓ) were directly obtained from the plasma profiles. The area under the curve (AUC₀–t), representing the extent of drug absorption over time, was estimated using the linear trapezoidal integration method. These pharmacokinetic indices provided insight into the absorption and systemic exposure of nabumetone following administration.

Statistical analysis

All numerical data are reported as mean values accompanied by standard deviations (mean±SD). Statistical comparisons between different treatment groups were performed using the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. GraphPad Prism software version 9.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was utilized for all statistical computations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Experimental data analysis and validation

To assess the effect of three formulation factors on five outcome variables, eighteen experimental trials were conducted (table 2). The data collected was utilized to create polynomial models for EE%, DL, MPZ, PDI, and ZP that included both main effects and interaction terms. The statistical significance of the models was assessed using P-values at a 95% confidence level, and the quadratic model demonstrated a significant fit for EE, DL, and MPZ (table 4). The measured values were 89.3 to 273.67 nm for MPZ, 0.24 to 0.77 for PDI, 7.04% to 14.94% for DL, 72.72% to 90.28% for EE, and −24.37 to −15.0 mV for ZP. These results confirmed that the quadratic model provided the best fit for the examined responses:

Table 4: Regression analysis results for the evaluated responses Z1–Z5

| Factors | EE % (Z1) | P | DL (Z2) | P | MPZ (Z3) | P | PDI (Z4) | P | ZP (Z5) | P |

| Model | 13.05 | 0.0013* | 9.12 | 0.0042* | 5.79 | 0.0192* | 1.61 | 0.3091 | 1.19 | 0.3975 |

| A | 1.65 | 0.2431 | 7.14 | 0.1363 | 9.52 | 0.0211* | 1.78 | 0.2264 | 2.18 | 0.6047 |

| B | 11.72 | 0.0085* | 3.57 | 0.0921 | 1.38 | 0.6617 | 4.32 | 0.0711 | 2.93 | 0.1689 |

| C | 46.92 | 0.0003* | 1.87 | 0.3175 | 13.02 | 0.0085* | 2.09 | 0.2012 | 1.68 | 0.6185 |

| AB | 6.42 | 0.0431* | 10.34 | 0.0198* | 0.97 | 0.8252 | 2.95 | 0.7789 | 1.41 | 0.6271 |

| AC | 11.34 | 0.0107* | 2.64 | 0.1375 | 0.68 | 0.4413 | 0.94 | 0.3612 | 0.79 | 0.4408 |

| BC | 9.85 | 0.0191* | 0.23 | 0.8712 | 0.92 | 0.4791 | 1.33 | 0.4557 | 0.91 | 0.5389 |

| A² | 6.52 | 0.0382* | 12.96 | 0.0087* | 0.79 | 0.3847 | 2.04 | 0.1813 | 2.37 | 0.1156 |

| B² | 9.02 | 0.0199* | 7.26 | 0.0349* | 22.18 | 0.0054* | 0.81 | 0.3031 | 2.46 | 0.1653 |

| C² | 15.09 | 0.0043* | 36.81 | 0.0082* | 0.91 | 0.7985 | 1.02 | 0.3276 | 2.92 | 0.0993 |

| Lack of Fit | 1.18 | 0.4139 | 0.68 | 0.6278 | 1.28 | 0.4195 | 6.45 | 0.0543 | 21.37 | 0.0059* |

| R² | 0.9421 | 0.9175 | 0.8633 | 0.6481 | 0.6032 |

Note: *Significant value at a 95% confidence level. Z = Response variables. R² = Coefficient of determination.

Encapsulation efficiency (EE%)

EE (%) = 86.38+(0.83×A)+(1.89×B)+(3.91×C)+(2.27×A×B)+ (3.15×A×C)−(1.76×B×C)−(2.13×A²)−(2.54×B²)−(3.04×C²)

Drug loading (DL%)

DL (%) = 13.91−(0.59×A)+(0.94×B)−(0.38×C)+(1.72×A×B)+ (1.07×A×C)−(0.17×B×C)−(1.89×A²)−(1.58×B²)−(3.32×C²)

Mean particle size (MPZ in nm)

MPZ (nm) = 222.74+(35.63×A)−(5.26×B)−(42.41×C)−(16.25×A×B)− (13.48×A×C)+(1.44×B×C)−(14.63×A²)−(80.91×B²)+(5.18×C²)

Polydispersity index (PDI)

PDI = 0.50+(0.07×A)−(0.088×B)−(0.075×C)−(0.022×A×B)− (0.058×A×C)−(0.049×B×C)−(0.087×A²)−(0.067×B²)+(0.065×C²)

Zeta potential (ZP in mV)

ZP (mV) = −21.06−(0.34×A)+(1.42×B)−(0.48×C)+(1.26×A×B)+ (1.02×A×C)+(0.57×B×C)+(1.96×A²)+(1.61×B²)−(0.63×C²)

To evaluate the influence of three formulation variables on five measured responses, a total of eighteen experimental runs were executed (table 2). The results obtained were employed to construct polynomial regression models for EE%, DL, MPZ, PDI, and ZP, integrating both linear and interaction components. The statistical relevance of these models was examined using P-values at a 95% confidence interval, where the quadratic model exhibited a strong fit for EE (Z1), DL (Z2), and MPZ (Z3), as detailed in table X. The observed measurements ranged from 91.7 to 265.42 nm for MPZ, 0.27 to 0.73 for PDI, 7.82% to 15.31% for DL, 71.64% to 89.89% for EE, and −25.84 to −14.72 mV for ZP. These findings supported the conclusion that the quadratic models best represented the variation in these responses. Table X outlines the effect of palmitic acid (PA, labeled as factor A) on the investigated outcomes. Both the mean particle size (MPZ, Z3) and entrapment efficiency (EE, Z1) of NAB-loaded SLPs were significantly influenced by PA, as evidenced by P-values below 0.05, indicating statistical significance. This implies that higher concentrations of PA correlated with increased EE and particle size. Sorbitan monostearate (SMS, factor B) had a significant effect on EE (Z1) only. Furthermore, Tween 80 (factor C) demonstrated a notable influence on both MPZ (Z3) and EE (Z1). Interaction effects among specific formulation factors were also significant, particularly with respect to EE (P<0.05), highlighting the importance of combined factor effects in optimizing formulation characteristics.

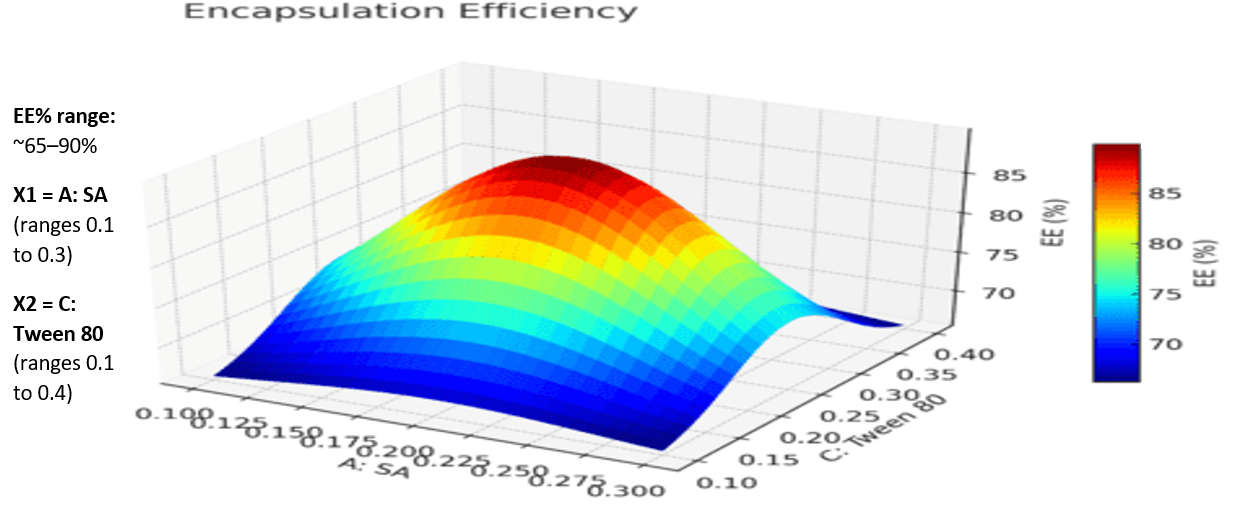

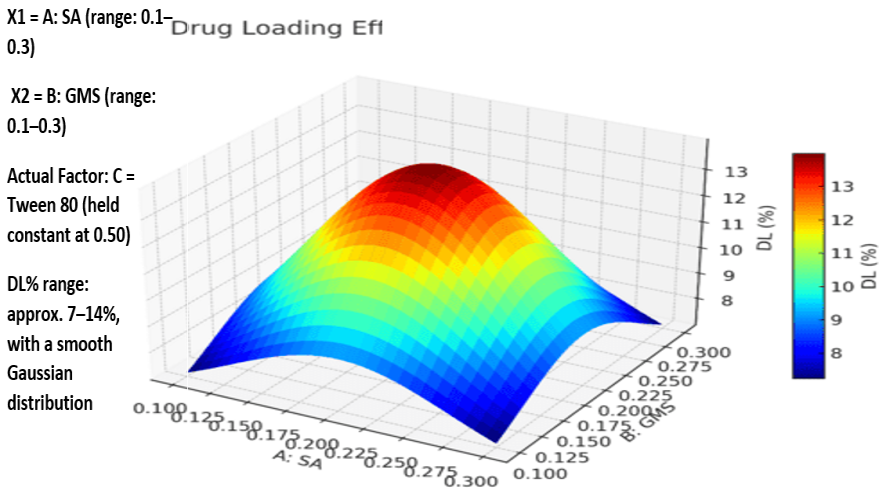

Based on the polynomial models, the three-dimensional response surface analysis findings were shown (fig. 3A–3C), illustrating the significant influence of independent variables on each measured response. Fig. 3's factor (C) 3D response surface is notably steeper, indicating that Tween 80 and SMS affect EE more strongly than PA. Furthermore, it was evident that the entrapment efficiency (EE) of the SLPs increased with lipid concentration. This enhancement might be attributed to the expanded internal lipid phase, which provides a larger medium for dissolving the lipophilic drug NAB. The observed increase in EE at elevated Tween 80 levels could be due to its superior emulsifying and stabilizing capabilities in conjunction with SMS. The medication's solubility in the solid lipid matrix has an impact on drug loading (DL). The lipid's capacity to retain and release the medication has been connected to its crystalline structure. Studies show that as compared to more crystalline forms, amorphous lipid molecules offer better medication incorporation and retention. According to the 3D response plot (fig. 4), DL (Z2) first increased and subsequently decreased as the formulations' lipid and surfactant levels grew. This implies that obtaining effective medication loading requires optimizing the quantity of excipients. The interaction between formulation elements and the mean particle size (MPZ) of SLPs was investigated using three-dimensional surface plots (fig. 5). The results demonstrated that when Tween 80 concentrations increased, SLP particle sizes shrank. The surfactant's ability to reduce the interfacial tension between the lipid and aqueous phases of the system, which enhances the stabilization of smaller nanoparticles and prevents lipid particle aggregation, explains this ingrowth effect [29]. The best formulation was determined using numerical optimization and a desire function technique, with the goal of providing maximum drug loading, maximum encapsulation efficiency, and minimal particle size. The revised NAB-SLP formulation included 0.20 g PA, 0.25 g SMS, and 0.55 g Tween 80.

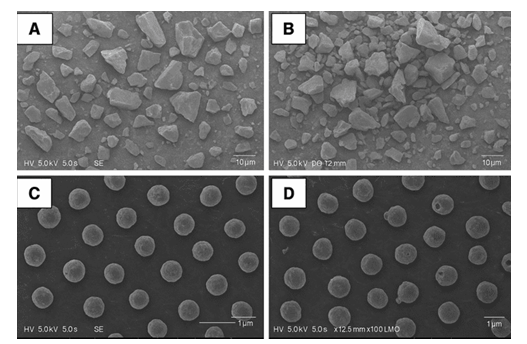

SEM analysis

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is often used to analyze the size, shape, and surface features of nanoparticles. NAB-loaded SLPs had a smooth exterior and a spherical or nearly spherical shape, as illustrated in fig. 4. Furthermore, there were no visible differences between the NAB-loaded SLPs and drug-free SLPs (fig. 4).

Fig. 3A: 3D interaction plots display the role of the independent variables on entrapment efficiency (EE%) of NAB-SLPs

Fig. 3B: 3D interaction plots display the role of the independent variables on Drug loading (DL) of NAB-SLPs

Fig. 3C: 3D interaction plots display the role of the independent variables on mean particle size (MPZ) of NAB-SLPs

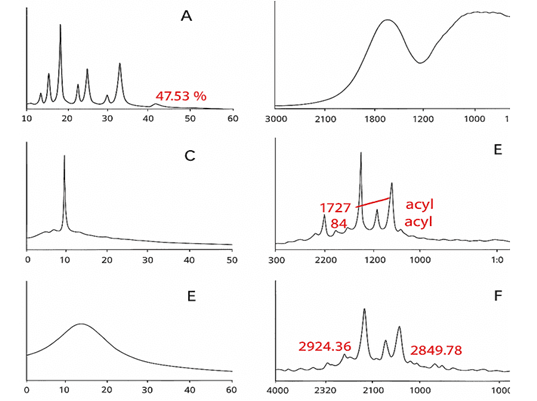

X-Ray diffraction analysis

Pure NAB, PA, SMS, their physical blends, and the final NAB-SLPs formulation were all subjected to X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) analysis because changes in crystallinity are indicative of the formation of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLPs) (fig. 5). Sharp peaks at 2θ angles of 6.0°, 12.0°, 16.0°, 17.0°, 19.0°, 21.0°, 24.0°, 25.0°, and 27.0° were visible in the diffraction pattern of pure NAB, indicating that the drug is in a crystalline form. Significant peaks were also visible in the lipid matrix, suggesting that it was crystalline. The loss of crystalline peaks in SLPs indicates that NAB is completely incorporated into the lipid matrix. This indicates that the drug was encapsulated in an amorphous non-crystalline form, which increases solubility, as well as enabling slower and more efficient release from the SLPs. XRPD data confirmed that NAB was molecularly dispersed within the lipid nanoparticle structure [43].

Fig. 4: Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of (A) Nabumetone, (B) mixture of Nabumetones and Palmitic acid and sorbitan monostearate, (C) NAB-loaded SLPs, (D)Blank SLPs (Magnification 1x100000)

FTIR analysis

FTIR spectroscopy was used to investigate the molecular interactions among the ingredients of the SLPs. It also served to detect the functional groups located on the nanoparticle surfaces. Fig. 8 shows the FTIR spectra of pure NAB, PA, SMS, their physical mixture, NAB-SLPs, and blank SLPs. Absorption spectra for SMS includes distinct peaks at 2916.57 cm⁻¹ (C–H stretching), 1729.67 cm⁻¹ (C=O stretching), 1178 cm⁻¹ (C–O stretching), and SMS also displayed distinct absorption bands at 1651 cm⁻¹ (COOH) and 1226 cm⁻¹ (aromatic C=C). PA also exhibited strong absorption peaks at 2915.71 cm⁻¹ and 1699.64 cm⁻¹ for C–H stretching and C=O stretching, respectively. The FTIR spectrum of physical mixture still had signature peaks of NAB, however, slight shifts were noted, indicating no chemical interaction between NAB and the lipid components. Carbonyl peaks belonging to NAB and the lipids were observed to overlap and shift in the NAB-SLPs spectrum, which, together with a weak shoulder peak attributable to NAB, implied successful entrapment of NAB into the lipid matrix. Reduced intensity of the peak also supported claims of encapsulation. The XRD results corroborated these FTIR findings, supporting the assertion that NAB was present in an amorphous state within the SLPs. The spectra strongly suggested, however, that the functional groups of the lipids remain unchanged in both pure form and in the SLPs, indicating that no chemical changes took place between NAB and the excipients during formulation [44].

Fig. 5: Diffraction patterns (X-ray) of (A) Nabumetone (NAB), (B) Palmitic acid, (C) and glyceryl monostearate (GMS), (D) a physical mixture of NAB and lipids, (E) freeze-dried NAB-SLPs and (F) freeze-dried blank NAB-SLPN

Gel properties analysis

The NAB-SLP-TSG mixture was evaluated for gelation temperature and gelation time. The gelation temperature for liquid suppositories is usually in the range of 30 °C–36 °C. Rao et al. noted that liquid suppositories were not produced with ideal gelling temperatures when P408 and P177 were used singularly. However, when P408 and P177 were combined, it was observed that higher P408 concentrations required lower P177 amounts to reach the desired gelation point [25]. Our previous studies showed that more P408 resulted in a lower gelation temperature, while greater amounts of P177 increased it. Following this logic, a mixture of 18% P408 and 10% P177 was prepared, achieving a gelation temperature of 35 °C. Afterwards, 0.2% HA was added [14, 44]. This mixture stays liquid at room temperature and transforms into a gel at body temperature.

In this NAB-SLP-TSG study, gelation times ranged from approximately 15 sec for NAB-SLP-TSG and 34 sec for NAB-TSG, showing how quickly gel formation occurs. To address standardization, gel strength data—originally reported in seconds using arbitrary weights—should instead be expressed as force in Newtons (N) or viscosity in Pa·s to enhance comparability across studies. To measure the level of gelation, gel strength and mucoadhesive force are the main parameters investigated [55]. Gels are best characterized by their strength and mucoadhesive force. Adequate gel strength and mucoadhesion provide retentive control of the gel at the site of administration, increasing residence time in the colorectal region and enhancing drug absorption [56].

Mucoadhesion is the adhesive interaction of the liquid suppository with the colorectal mucosa at 36.5 °C [19]. Past research indicates that poloxamers can moderate mucoadhesion by interacting with oligosaccharides on the colorectal mucosa due to the presence of hydrophilic oxide groups. Strong mucoadhesion helps retain the gel formulation in the rectum, preventing colon migration and potentially minimizing the first-pass effect [58]. Optimal mucoadhesion is required, however, because excess adhesive force may cause injury to mucosal tissue. It is vital for continuous capillary flow and tissue reception to maintain controlled levels of adhesive force.

Porcine mucosa was used as the model tissue in bioadhesive testing; however, justification for its use and relevance to human rectal mucosa is required. Supporting literature should be cited to validate this model. As shown in our results, NAB-SLP-TSG possessed favorable values of gelation temperature (30–33 °C), gel strength (converted to standardized units), and mucoadhesive force (12.64±0.28 dyne/cm², equivalent to standardized SI units if available). The formulation was easily administered rectally, retained its position without leaking, and did not migrate from the administration site. In addition, the suppository's adhesive capabilities allowed it to remain localized, potentially reducing exposure to first-pass metabolism.[13] Nevertheless, it should be noted that the effect of varying γ-PGA concentrations on mucoadhesive performance was not systematically evaluated in this study, and further optimization studies are warranted to establish the concentration–adhesion relationship.

Rheological properties analysis

Rheological properties represent a crucial physicochemical parameter in the formulation of an effective topical drug delivery system. The viscoelastic characteristics of NAB-SLP-TSG were investigated to evaluate its mechanical stability. To assess the linear viscoelastic range, it is essential to identify the region in which the material exhibits consistent rheological behavior. In this study, a nabumetone-based in situ gel was utilized to determine this region by observing variations in the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) in response to increasing shear strain. As illustrated in fig. 7, the relationship between the viscoelastic moduli (G′ and G″) and the shear strain amplitude (γ) reflects the gel's structural integrity. The results enabled the identification of the maximum strain the gel’s internal network could endure before structural breakdown, and an amplitude sweep was conducted to establish this behavior. At a fixed angular frequency of 8 rad/s, the rheological properties were assessed over a strain amplitude range of 0.02% to 120%. Within the range of 0.2% to 2% strain, both the storage modulus (G′) and the loss modulus (G″) remained constant, indicating that this region lies within the linear viscoelastic domain. Consequently, a strain of 2% was chosen for all subsequent dynamic rheological assessments [17, 21]. The data revealed that the formulation exhibited predominantly elastic behavior when the strain (γ) was below 12%, as G′ exceeded G″ in this elastic G′ was observed once the strain exceeded 12%, and the crossover point, where G′ equaled.

Fig. 6: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectra(FTIR) of (A) Nabutamone, (B) palmitic acid, (C) sorbitan monostearate, (D) a physical mixture of drug and lipids, (E) ibuprofen-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles and (F) blank solid lipid nanoparticles

G″—marked the disruption of the gel matrix. Beyond this point, the formulation began to display viscous fluid-like behavior, evidenced by G′ falling below G″. The gel strength, defined as the viscosity of the formulation at physiological temperature (37 °C), was also evaluated. As presented in fig. 7B, the viscosity profile confirmed pseudoplastic (shear-thinning) behavior, with viscosity decreasing progressively as the shear rate increased. This rheological feature facilitates manufacturing processes—making the product easier to mix, fill, and handle—while also minimizing potential rectal mucosal irritation and enhancing patient compliance. The viscoelastic properties of NAB-SLP-TRG and NAB-TRG formulations at 37 °C are shown in fig. 7C. Both exhibited typical viscoelastic behavior over the frequency sweep, where G′ consistently remained higher than G″, indicating that the elastic properties dominated. G′ remained stable across the frequency range, while G″ displayed a slight decline, suggesting the maintenance of the gel’s structural framework. Notably, NAB-TRG demonstrated a higher G′ compared to NAB-SLP-TRG, indicating that it possessed a stiffer texture and superior internal structural consistency.

Fig. 7: Rheological analysis of NAB-SLP-TRG and NAB-TRG formulations. (A) Strain sweep profiles of NAB-SLP-TRG and NAB-TRG; (B) Viscosity response to shear rate at 37 °C; (C) Frequency sweep illustrating elastic and viscous moduli of NAB-SLP-TRG and NAB-TRG at 37 °C and 10 rad/s oscillation

In vitro drug release study

Fig. 8 illustrates the in vitro drug release profiles for selected formulations. The cumulative release percentages of NAB from NAB-SLP, NAB-SLP-TSG, and NAB-TSG were found to be 91.43±2.56%, 83.11±2.39%, and 70.47±5.22%, respectively, throughout the study duration. During the initial 2-hour period, nearly 20% of the drug was released from the SLP-TSG formulation, with a continuous release pattern observed thereafter. This delayed release behavior may result from a gradual diffusion of the active component from the lipid matrix. The NAB-SLP formulation displayed a biphasic release pattern: an initial burst followed by a prolonged release phase. The early-stage rapid release may be attributed to the ease of drug release from the lipid surface. Additionally, elevation in temperature may soften the lipid layer, thereby enhancing NAB solubility [40, 41]. The presence of non-encapsulated NAB on the nanoparticle surface could also contribute to the initial release spike. The increased release rate may further be linked to the nanoparticles’ high surface area and surface-adsorbed NAB. A rise in osmotic pressure within the dialysis bag compared to the external medium could also facilitate accelerated diffusion. SLPs have demonstrated a significant improvement in the solubility and dissolution rate of NAB in comparison to other delivery systems. On the contrary, NAB-SLP-TSG exhibited a slower release pattern, potentially due to the release-modulating properties of the gel matrix, which controls drug diffusion. Given NAB’s limited aqueous solubility, NAB-TSG presented the lowest release rate among the tested formulations. To analyze the release mechanism, different kinetic models—including zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, and Ritger–Peppas—were applied to the data. The coefficient of determination (R²) values is listed in table 5. Among these models, the Higuchi model offered the best fit, with an R² of 0.9912, indicating that the drug release from NAB-SLP-TRG followed a Fickian diffusion mechanism. However, the observed biphasic release profile suggests that Fickian diffusion alone may not fully explain the mechanism. The Korsmeyer–Peppas model yielded an “n” value of 0.47, which typically indicates Fickian diffusion, but this does not account for the initial burst release and subsequent sustained phase. The biphasic nature may suggest anomalous transport behavior due to matrix erosion or swelling of the thermosensitive gel. Therefore, a combination of diffusion and polymer relaxation (non-Fickian or anomalous transport) may better describe the release kinetics. Additionally, the initial burst release was attributed to a surface-associated drug, but this interpretation lacks supporting data. Quantitative analysis distinguishing between free and encapsulated drug content should be conducted, for example via ultrafiltration or centrifugation, to validate this hypothesis and strengthen the mechanistic explanation [30].

These findings are supported by the smaller particle size and uniform spherical shape of NAB-SLPs, which enhance NAB’s solubility within the lipid matrix and allow for accurate kinetic modeling using the Higuchi equation. As shown in table 6, the calculated diffusion exponent (n) for NAB-TRG is approximately 0.48, supporting the idea that drug release occurs via Fickian diffusion through surface and internal channels of the poloxamer gel matrix in an aqueous environment [11].

Fig. 8: In vitro drug release profiles of NAB from selected different formulation in phosphate buffer. Results represented as the mean±SD; n = 3)

Table 5: The kinetic model fitting of release of NAB from different SLP-TSG formulations

| Model | NAB-SLP-TRG | NAB-TRG | NAB-SLP |

| Zero-order kinetic | Mt = 3.56t+18.40 R² = 0.7345 | Mt = 3.18t+9.42 R² = 0.8146 | Mt = 3.62t+33.45 R² = 0.5891 |

| First-order kinetic | ln Mt = 0.18t+83.24 R² = 0.9261 | ln Mt = 0.11t+76.83 R² = 0.9482 | ln Mt = 1.22t+91.34 R² = 0.9812 |

| Higuchi kinetic | Mt/M∞ = 21.35√t – 0.87 R² = 0.9872 | Mt/M∞ = 16.84√t – 4.55 R² = 0.9784 | Mt/M∞ = 23.56√t+11.74 R² = 0.8417 |

| Ritger–Peppas kinetic | Mt/M∞ = 24.19*t^0.47 R² = 0.9395 | Mt/M∞ = 12.86*t^0.53 R² = 0.9423 | Mt/M∞ = 36.74*t^0.35 R² = 0.8638 |

Pharmacokinetic study of a selected formula of NAB-SLP-TSG

The plasma concentration–time profiles are illustrated in fig. 9, while key pharmacokinetic parameters are provided in table 6. The plasma levels of NAB in the NAB-SLP-TRG group were significantly elevated compared to those observed in the NAB-TRG and NAB solid suppository formulations at all measured time points.

Based on the peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC), the NAB-SLP-TRG formulation demonstrated more rapid absorption and achieved higher systemic drug levels. The mean residence time (MRT) and elimination half-life (t₁/₂) of NAB-SLP-TRG and NAB-TRG were found to be 9.12 h and 4.68 h, and 7.21 h and 5.2 h, respectively. The AUC₀–∞ value for NAB-SLP-TRG was 144.53±25.48 µg·h/ml, markedly higher than that of NAB-TRG (85.92±49.73 µg·h/ml, p<0.05) and the NAB-suppository (43.76±15.12 µg·h/ml, p<0.01). Furthermore, the AUC₀–t of the NAB-SLP-TRG (62.85±24.14 µg·h/ml) increased by approximately 59.9% compared to the NAB-TRG group (39.3±1.58 µg·h/ml). Compared with the NAB-suppository, the AUC₀–t of NAB-SLP-TRG was 3.22-fold higher (62.85±24.14 vs. 19.48±7.91 µg·h/ml), indicating a substantial enhancement in bioavailability (table 6).

Pharmacokinetic evaluation revealed that NAB-SLP-TRG improved the oral bioavailability of nabumetone by approximately 3.2 times over the NAB suppository and extended the elimination half-life to about 7.21 h. Following rectal administration, the NAB-SLP-TRG formulation resulted in longer t₁/₂ and MRT, and significantly increased AUC₀–∞ in comparison to the conventional suppository, suggesting enhanced drug retention and controlled release properties, potentially reducing dosing frequency [49, 50].

In contrast with the NAB-TRG, the NAB-SLP-TRG formulation produced notably higher Cmax and MRT values. The maximum plasma concentration reached was 19.22±1.41 µg/ml for NAB-SLP-TRG, as shown in table 6. Additionally, the MRT for NAB-SLP-TRG (9.12 h) was significantly longer than that of the NAB suppository (2.82 h) (p<0.01). The elimination half-life was also significantly extended (p<0.01) in the NAB-SLP-TRG group compared to the suppository.

These findings suggest that NAB-SLP-TRG enables more efficient drug absorption, likely due to the presence of the lipid-based matrix, which allows gradual drug dissolution and distribution in the rectal cavity. Conversely, NAB-TRG disperses and gels more immediately, adhering to the rectal mucosa. The data support that solid lipid nanoparticle-based in situ gels are effective delivery systems for nabumetone, improving solubility and prolonging absorption. The use of NAB-SLP-TRG for rectal delivery was shown to increase drug residence time, promote absorption, and significantly boost the systemic bioavailability of nabumetone [6, 18].

Fig. 9: The plasma concentration–time profiles are illustrated

Table 6: Pharmacokinetic parameters of IBU in serum after rectal administration (X±SD, n=6)

| Parameter | NAB-Suppository | NAB-ISG | NAB-SLN-ISG |

| Cmax (µg/ml) | 13.72±2.81 | 15.09±1.45 | 17.33±1.18 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.58±0.12 | 1.18±0.29 | 1.42±0.06 |

| t1/2 (h) | 1.52±0.45 | 4.62±0.85** | 6.47±1.04** |

| AUC0→t (µg·h/ml) | 16.86±7.94 | 35.11±3.04* | 56.72±21.89 |

| AUC0→∞ (µg·h/ml) | 36.59±14.21 | 70.05±41.92 | 128.47±25.65** |

| MRT0→∞ (h) | 2.45±0.64 | 4.09±1.05 | 8.12±0.92** |

P < 0.05, P < 0.01 compared to the NAB-suppository group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to the NAB-ISG group. AUC₀→∞ represents the area under the plasma concentration–time curve from zero to infinity, calculated by the trapezoidal rule. SD indicates standard deviation; t₁/₂ is the elimination half-life; Cₘₐₓ refers to the peak plasma concentration; Tₘₐₓ is the time taken to reach Cₘₐₓ; and F₁ denotes absolute bioavailability (n=6).

CONCLUSION

Nabumetone-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (NAB-SLPs) were successfully formulated, characterized, and optimized using a Central Composite design for rectal administration. The influence of formulation components, specifically palmitic acid (PA), glyceryl monostearate (GMS), and Tween 80, on encapsulation efficiency (EE), drug loading (DL), mean particle size (MPZ), polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential (ZP) of the SLPs was thoroughly evaluated. The optimized formulation exhibited favorable physicochemical characteristics.

These SLPs were incorporated into a thermosensitive gel base, which demonstrated pseudoplastic rheological behavior and an acceptable texture suitable for rectal use. In vitro release studies of NAB-SLPs and the NAB-SLP–thermosensitive gel (NAB-SLP-TSG) revealed a biphasic release profile, with an initial burst release followed by a sustained drug release phase.

Importantly, NAB-SLP-TSG showed significantly enhanced drug absorption and improved systemic bioavailability in animal models. Furthermore, no irritation or tissue damage was observed in the rectal mucosa, and the gel formulation maintained prolonged residence in the rectum. These findings support the potential of NAB-SLP-TSG as a practical and efficient rectal delivery system for administering non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Dalia A. Gaber; Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. Mohammed A. Amin; Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation. Mostafa A. Mohamed; Software, Statistical analysis, Resources, Data interpretation, Writing – review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Matsumoto K, Hasegawa T, Ohara K, Takei C, Kamei T, Koyanagi J. A metabolic pathway for the prodrug nabumetone to the pharmacologically active metabolite 6-methoxy-2-naphthylacetic acid (6-MNA) by non-cytochrome P450 enzymes. Xenobiotica. 2020;50(7):783-92. doi: 10.1080/00498254.2019.1704097, PMID 31855101.

Jameel BK, Raauf AM, Abbas WA. Synthesis, characterization molecular docking in silico ADME study and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of new pyridine derivatives of nabumetone. Al Mustansiriyah J Pharm Sci. 2023;23(3):250-62. doi: 10.32947/ajps.v23i3.1042.

Jagdale SC, Deore GK, Chabukswar AR. Development of microemulsion-based nabumetone transdermal delivery for treatment of arthritis. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 2018;12(2):130-49. doi: 10.2174/1872211312666180227091059, PMID 29485013.

Grande F, Ragno G, Muzzalupo R, Occhiuzzi MA, Mazzotta E, Luca MD. Gel formulation of nabumetone and a newly synthesized analog: microemulsion as a photoprotective topical delivery system. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(5):423. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12050423, PMID 32380748.

Park YJ, Yong CS, Kim HM, Rhee JD, Oh YK, Kim CK. Effect of sodium chloride on the release, absorption and safety of diclofenac sodium delivered by poloxamer gel. Int J Pharm. 2003;263(1-2):105-11. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(03)00362-4, PMID 12954185.

El Leithy ES, Shaker DS, Ghorab MK, Abdel Rashid RS. Evaluation of mucoadhesive hydrogels loaded with diclofenac sodium chitosan microspheres for rectal administration. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2010;11(4):1695-702. doi: 10.1208/s12249-010-9544-3, PMID 21108027.

Kawish SM, Hasan N, Beg S, Qadir A, Jain GK, Aqil M. Docetaxel loaded borage seed oil nanoemulsion with improved antitumor activity for solid tumor treatment: formulation development in vitro in silico and in vivo evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022;75:103693. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103693.

Alhalmi A, Amin S, Khan Z, Beg S, Al Kamaly O, Saleh A. Nanostructured lipid carrier-based codelivery of raloxifene and naringin: formulation optimization in vitro, ex vivo, in vivo assessment and acute toxicity studies. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(9):1771. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14091771, PMID 36145519.

Pivetta TP, Simoes S, Araujo MM, Carvalho T, Arruda C, Marcato PD. Development of nanoparticles from natural lipids for topical delivery of thymol: investigation of its anti-inflammatory properties. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2018;164:281-90. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.01.053, PMID 29413607.

He C, Kim SW, Lee DS. In situ gelling stimuli-sensitive block copolymer hydrogels for drug delivery. J Control Release. 2008;127(3):189-207. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.01.005, PMID 18321604.

Park YJ, Yong CS, Kim HM, Rhee JD, Oh YK, Kim CK. Effect of sodium chloride on the release, absorption and safety of diclofenac sodium delivered by poloxamer gel. Int J Pharm. 2003;263(1-2):105-11. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(03)00362-4, PMID 12954185.

Shtay R, Tan CP, Schwarz K. Development and characterization of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) made of cocoa butter: a factorial design study. J Food Eng. 2018;231:30-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.03.006.

Singh A, Neupane YR, Mangla B, Kohli K. Nanostructured lipid carriers for oral bioavailability enhancement of exemestane: formulation design in vitro ex vivo and in vivo studies. J Pharm Sci. 2019;108(10):3382-95. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2019.06.003, PMID 31201904.

Alam T, Khan S, Gaba B, Haider MF, Baboota S, Ali J. Adaptation of quality by design-based development of isradipine nanostructured lipid carrier and its evaluation for in vitro gut permeation and in vivo solubilization fate. J Pharm Sci. 2018;107(11):2914-26. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2018.07.021, PMID 30076853.

Li L, Guo D, Guo J, Song J, Wu Q, Liu D. Thermosensitive in situ forming gels for ophthalmic delivery of tea polyphenols. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2018;46:243-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2018.05.019.

Zafar S, Akhter S, Ahmad I, Hafeez Z, Alam Rizvi MM, Jain GK. Improved chemotherapeutic efficacy against resistant human breast cancer cells with co-delivery of docetaxel and thymoquinone by chitosan grafted lipid nanocapsules: formulation optimization in vitro and in vivo studies. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2020;186:110603. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110603, PMID 31846892.

Patel A, Bell M, O Connor C, Inchley A, Wibawa J, Lane ME. Delivery of ibuprofen to the skin. Int J Pharm. 2013;457(1):9-13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.09.019, PMID 24064201.

Rizwanullah M, Amin S, Ahmad J. Improved pharmacokinetics and antihyperlipidemic effiacy of rosuvastatin-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers. J Drug Target. 2017;25(1):58-74. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2016.1191080, PMID 27186665.

Kawish SM, Ahmed S, Gull A, Aslam M, Pandit J, Aqil M. Development of nabumetone-loaded lipid nano-scaffold for the effective oral delivery; optimization characterization drug release and pharmacodynamic study. J Mol Liq. 2017;231:514-22. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.01.107.

Alam M, Ahmed S, N, Moon G, Aqil M, Sultana Y. Chemical engineering of a lipid nano-scaffold for the solubility enhancement of an antihyperlipidaemic drug simvastatin; preparation optimization, physicochemical characterization and pharmacodynamic study. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2017;46(8):1-12. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1396223.

Rizwanullah M, Ahmad J, Amin S. Nanostructured lipid carriers: a novel platform for chemotherapeutics. Curr Drug Deliv. 2016;13(1):4-26. doi: 10.2174/1567201812666150817124133, PMID 26279117.

Negi LM, Jaggi M, Joshi V, Ronodip K, Talegaonkar S. Hyaluronic acid decorated lipid nanocarrier for MDR modulation and CD-44 targeting in colon adenocarcinoma. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;72:569-74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.09.005, PMID 25220787.

Sartaj A, Annu, Alam M, Biswas L, Yar MS, Mir SR. Combinatorial delivery of ribociclib and green tea extract mediated nanostructured lipid carrier for oral delivery for the treatment of breast cancer, synchronising in silico in vitro and in vivo studies. J Drug Target. 2022;30(10):1113-34. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2022.2104292.

Ivanova NA, Trapani A, Franco CD, Mandracchia D, Trapani G, Franchini C. In vitro and ex vivo studies on diltiazem hydrochloride-loaded microsponges in rectal gels for chronic anal fissures treatment. Int J Pharm. 2019;557:53-65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.12.039, PMID 30580086.

Ahmed S, Mahmood S, Danish Ansari MD, Gull A, Sharma N, Sultana Y. Nanostructured lipid carrier to overcome stratum corneum barrier for the delivery of agomelatine in rat brain; formula optimization, characterization and brain distribution study. Int J Pharm. 2021;607:121006. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121006, PMID 34391848.

Yuan Y, Cui Y, Zhang L, Zhu HP, Guo YS, Zhong B. Thermosensitive and mucoadhesive in situ gel based on poloxamer as new carrier for rectal administration of nimesulide. Int J Pharm. 2012;430(1-2):114-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.03.054, PMID 22503953.

Kolawole OM, Lau WM, Khutoryanskiy VV. Chitosan/β-glycerophosphate in situ gelling mucoadhesive systems for intravesical delivery of mitomycin-C. Int J Pharm X. 2019;1:100007. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpx.2019.100007, PMID 31517272.

Vigani B, Rossi S, Sandri G, Bonferoni MC, Caramella CM, Ferrari F. Recent advances in the development of in situ gelling drug delivery systems for non-parenteral administration routes. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(9):859. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12090859, PMID 32927595.

Zahir Jouzdani F, Wolf JD, Atyabi F, Bernkop Schnurch A. In situ gelling and mucoadhesive polymers: why do they need each other? Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2018;15(10):1007-19. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2018.1517741, PMID 30173567.

Myers RH, Montgomery DC, Anderson Cook CM. Response surface methodology: process and product optimization using designed experiments. 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2016.

Batool S, Zahid F, Ud Din F, Naz SS, Dar MJ, Khan MW. Macrophage targeting with the novel carbopol-based miltefosine-loaded transfersomal gel for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis: in vitro and in vivo analyses. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2021;47(3):440-53. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2021.1890768, PMID 33615936.

Jagdale SC, Deore GK, Chabukswar AR. Development of microemulsion-based nabumetone transdermal delivery for treatment of arthritis. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 2018;12(2):130-49. doi: 10.2174/1872211312666180227091059, PMID 29485013.

Pham CV, Van MC, Thi HP, Thanh CD, Ngoc BT, Van BN. Development of ibuprofen loaded solid lipid nanoparticle-based hydrogels for enhanced in vitro dermal permeation and in vivo topical anti-inflammatory activity. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020;57:101758. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.101758.

Baig MS, Ahad A, Aslam M, Imam SS, Aqil M, Ali A. Application of box–behnken design for preparation of levofloxacin-loaded stearic acid solid lipid nanoparticles for ocular delivery: optimization in vitro release ocular tolerance and antibacterial activity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;85:258-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.12.077, PMID 26740466.

Plosker GL, Faulds D. Epirubicin a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in cancer chemotherapy. Drugs. 1993;45(5):788-856. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199345050-00011, PMID 7686469.

Zahir Jouzdani F, Wolf JD, Atyabi F, Bernkop Schnurch A. In situ gelling and mucoadhesive polymers: why do they need each other? Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2018;15(10):1007-19. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2018.1517741, PMID 30173567.

Din FU, Choi JY, Kim DW, Mustapha O, Kim DS, Thapa RK. Irinotecan encapsulated double reverse thermosensitive nanocarrier system for rectal administration. Drug Deliv. 2017;24(1):502-10. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2016.1272651, PMID 28181835.

Wadetwar RN, Agrawal AR, Kanojiya PS. In situ gel containing Bimatoprost solid lipid nanoparticles for ocular delivery: in vitro and ex vivo evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020;56:101575. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.101575.

Ivanova NA, Trapani A, Franco CD, Mandracchia D, Trapani G, Franchini C. In vitro and ex vivo studies on diltiazem hydrochloride-loaded microsponges in rectal gels for chronic anal fissures treatment. Int J Pharm. 2019;557:53-65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.12.039, PMID 30580086.

Kumar R, Singh A, Sharma K, Dhasmana D, Garg N, Siril PF. Preparation characterization and in vitro cytotoxicity of fenofibrate and nabumetone loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020;106:110184. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110184, PMID 31753394.

Purohit TJ, Hanning SM, Wu Z. Advances in rectal drug delivery systems. Pharm Dev Technol. 2018;23(10):942-52. doi: 10.1080/10837450.2018.1484766, PMID 29888992.

Park H, Kim MH, Yoon YI, Park WH. One-pot synthesis of injectable methylcellulose hydrogel containing calcium phosphate nanoparticles. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;157:775-83. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.10.055, PMID 27987990.

Bar Shalom D, Klaus R, editors. Pediatric formulations: a road map. AAPS Adv Pharm Sci. 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-8011-3.

Li L, Guo D, Guo J, Song J, Wu Q, Liu D. Thermosensitive in situ forming gels for ophthalmic delivery of tea polyphenols. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2018 Aug;46:243-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2018.05.019.

Chen L, Han X, Xu X, Zhang Q, Zeng Y, Su Q. Optimization and evaluation of the thermosensitive in situ and adhesive gel for rectal delivery of budesonide. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020;21(3):97. doi: 10.1208/s12249-020-1631-5, PMID 32128636.

Ramadan EM, Borg TM, Elkayal MO. Formulation and evaluation of novel mucoadhesive ketorolac tromethamine liquid suppository. Asian J Pharm Pharmacol. 2016;3:124-32.

Din FU, Kim DW, Choi JY, Thapa RK, Mustapha O, Kim DS. Irinotecan-loaded double reversible thermogel with improved antitumor efficacy without initial burst effect and toxicity for intramuscular administration. Acta Biomater. 2017;54:239-48. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.03.007, PMID 28285074.

Xing R, Mustapha O, Ali T, Rehman M, Zaidi SS, Baseer A. Development characterization and evaluation of SLN-loaded thermoresponsive hydrogel system of topotecan as biological macromolecule for colorectal delivery. BioMed Res Int. 2021;2021:9968602. doi: 10.1155/2021/9968602, PMID 34285920.

Al Kinani AA, Zidan G, Elsaid N, Seyfoddin A, Alani AW, Alany RG. Ophthalmic gels: past present and future. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;126:113-26. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.12.017, PMID 29288733.

Agibayeva LE, Kaldybekov DB, Porfiryeva NN, Garipova VR, Mangazbayeva RA, Moustafine RI. Gellan gum and its methacrylated derivatives as in situ gelling mucoadhesive formulations of pilocarpine: in vitro and in vivo studies. Int J Pharm. 2020;577:119093. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119093, PMID 32004682.