Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 152-161Reviewl Article

ADVANCED NANOCARRIERS FOR OCULAR DRUG DELIVERY: STRATEGIES TO OVERCOME OCULAR BARRIERS

DIVYA1, RUPA MAZUMDER1*, ANJNA RANI1, RAKHI MISHRA2

1Department of Pharmaceutics, Noida Institute of Engineering and Technology (Pharmacy Institute), Knowledge Park-II, Greater Noida-201306, Uttar Pradesh, India. 2Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Noida Institute of Engineering and Technology (Pharmacy Institute), Knowledge Park-II, Greater Noida-201306, Uttar Pradesh, India

*Corresponding author: Rupa Mazumder; *Email: rupa_mazumder@rediffmail.com

Received: 03 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 23 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

Ocular drug delivery is confronted with significant challenges because of the eye's specific anatomy and physiological barriers, including the blood-retinal and corneal epithelium. Traditional dose formulations often experienced rapid precorneal clearance and low absorption. Recent advances in nanotechnology, such as liposomes, cubosomes, glycerosomes, nano wafers, microneedles, vectors for gene therapy, olaminosomes, bilosomes, and exosomes, offer promising alternatives to bypass these limitations. These techniques facilitate longer ocular retention, controlled release, targeted distribution, enhanced drug solubility, and improved patient compliance. For instance, glycerosomes and nanoliposomes enhance permeability and biocompatibility; nanogels and cubosomes have structural advantages for drug stabilization and sensitivity; microneedles offer a minimally invasive approach to achieve epithelial barriers; exosomes enable targeted bioactivity and intracellular delivery; and olaminosomes, which are made of lipid-based vesicles and oleylamine, offer great entrapment efficiency and corneal adherence. In contrast, bilosomes, which incorporate bile salts, improve corneal permeability. The present work provides comprehensive insights into nanocarrier approaches for improving ocular bioavailability, along with related patents and clinical trials in this field.

Keywords: Ocular drug delivery, Nanocarriers, Permeation enhancement, Ocular barriers, Advanced delivery system, Bio-availability, Patents, Clinical trial

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55388 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

The eye is an important primary sense organ that is vital to human awareness. It is a specialized and intricate organ. Infections, injuries, and other conditions that might damage the eye's defense mechanism cause millions of people worldwide to have visual acuity deficiencies [1]. Formulators and researchers have major obstructions in properly delivering therapeutic substances to ocular tissues because of the various defense mechanisms and the distinct physiological and anatomical characteristics of the eye. The fundamental objectives of ODDSs are to overcome different ocular barriers, decrease dosing frequency, and preserve therapeutic medication concentrations at the targeted location. The system should be designed to increase medication availability at the intended place of action while preventing any injury to the eye throughout the delivery process [2]. Eye drops, injections, ointments, gels, and other formulations are among the many conventional ocular drug delivery methods that are commercially available to treat ocular diseases. These conventional dosage forms do, however, have several intrinsic drawbacks, such as inadequate therapeutic agent retention time on the ocular surface, fast eye drainage, accelerated tear turnover that lowers bioavailability, a higher chance of ocular side effects, and less-than-ideal patient adherence [3]. Eye drops still make up 90% of ocular treatments despite these major limitations, but only 5% of the prescribed amount is effectively absorbed due to rapid drainage, tear dilution, and ineffective absorption, meaning that only a small portion of the medication reaches the intended intraocular tissues. Therefore, frequent installations are required to reach the therapeutic levels, which may cause cellular damage and toxicity to the ocular surface [4]. Given the facts, the development and expansion of innovative and more effective drug administration techniques has emerged as a pressing need to overcome these innate challenges, necessitating a paradigm shift toward more intricate methods to maximize therapeutic results in ocular treatments. Innovative drug delivery systems based on nanotechnology, including micelles, nanosuspensions, nanoemulsions, nanoparticles, liposomes, enzysomoses, niosomes, cubosomes, and nano-wafers, olaminosomes, bilosomes, carbon nanotubes, mesoporous silica gel and quantum dots have been studied as better substitutes for conventional ocular delivery techniques in recent decades for the treatment of a variety of ocular diseases. These nanocarriers offer enhanced bioavailability, stability, and solubility. They serve as drug reservoirs, which enables sustained drug delivery, lowers the frequency of administration, and increases patient compliance [5, 6]. In conclusion, research on non-invasive ocular drug delivery methods has garnered significant attention, aiming to overcome ocular barriers, preserve therapeutic efficacy, and maintain controlled drug release. The field of ocular drug therapy appears to be on the verge of revolutionary discoveries due to nanotechnology, despite a significant portion of current research still being in its early stages.

Methods

A comprehensive literature review was conducted using databases such as Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar, and the library. Keywords including ocular drug delivery, nanocarriers, permeation enhancement, and ocular barriers were used. The search included peer-reviewed articles published between 2020 and 2025, focusing on English-language studies involving advanced nanocarriers in ophthalmic applications.

Novel approaches for permeation enhancement

Several nanocarriers formulated using synthetic organic nanomaterials, including lipid-based nanoparticles, dendrimers, polyester, polymeric micelles, and natural biopolymers, are found in the field of ocular nanomedicine[7]. Furthermore, inorganic nanomaterials such as silica nanoparticles, metal oxide nanoparticles, carbon-based materials, and quantum dots are essential. Additionally, biological elements like exosomes and pure biomolecules are intriguing. An overview of ocular nanomedicines is provided in this part; each is distinguished by its unique structure, composition, and characteristics. Additionally, using information from current representative research, we examine the benefits and drawbacks of each formulation when used in the field of ophthalmology.

Solid lipid nanoparticles vs nanostructured lipid carriers

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) represent two prominent lipid-based nanocarriers employed in ocular drug delivery[8]. While both systems enhance drug stability and provide sustained release, important differences influence their suitability for specific ocular applications [9, 10].

SLNs are composed of solid lipids that remain in a solid state at both room and body temperatures. They offer good drug encapsulation and biocompatibility, but their crystalline structure may lead to drug expulsion during storage [11]. SLNs typically demonstrate high physical stability but can suffer from limited drug loading due to their tightly packed lipid matrix. A research study effectively created tacrolimus-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles integrated into an in-situ gel (TAC-SLNs ISG) by combining probe sonication and high-shear homogenization methods. The final formulation attained an average particle size of around 122.3±4.3 nm. Evaluations conducted in vivo and in vitro showed a profile of sustained drug release [12].

However, NLCs incorporate a blend of solid and liquid lipids, creating an imperfect matrix that allows greater drug incorporation and reduces the risk of drug expulsion [13]. This structural advantage enables NLCs to accommodate lipophilic drugs more efficiently and enhance corneal penetration. Research conducted by Santonocito et al. developed and assessed mangiferin-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (MGN–NLCs) were shown to efficiently penetrate corneal permeation, hence boosting their improved delivery capabilities [4]. Moreover, NLCs have shown improved mucoadhesion and prolonged precorneal retention compared to SLNs, which may translate into better therapeutic outcomes in ocular conditions requiring sustained drug exposure.

Overall, while SLNs offer a more rigid and stable structure[15], NLCs provide enhanced flexibility, higher drug loading capacity, and better adaptability for complex formulations. The choice between SLNs and NLCs depends on the nature of the drug, the desired release profile, and the specific target within the ocular tissues.

Liposomes

Liposomes are nanoscale carriers that resemble biological membranes (consisting of a lipid bilayer around an aqueous center) and size ranging between 50 and 500 nm, which has a significant impact on how they distribute drugs [16, 17]. Liposomes are useful for delivering medications to both the anterior and posterior eye segments while reducing discomfort because of their tiny size and positive surface charge, which enhances corneal penetration and ocular retention [18]. Cationic FK506-loaded liposomes were created by Chen et al. to improve ocular medication delivery for the treatment of dry eye, and their effectiveness was assessed by in vivo investigations. Results demonstrate the potential of FK506 liposomes as an efficient ocular drug delivery technology by confirming that they not only prolong residence time on the ocular surface but also markedly improve corneal drug penetration [19]. Although their benefits, liposomes have drawbacks such as immunological responses, aggregation, drug leakage, and low stability brought on by lipid oxidation [20].

Polymeric micelles

Polymeric micelles are carriers that self-assemble. With core-shell structures made of amphiphiles that are typically 10–100 nm in size. The majority of polymeric micelles are made with amphiphilic copolymers, which allow for targeting, in vivo stability, and sustained release [21, 22]. Micelles improve medication penetration into eye tissues, lowering toxicity and frequency of dose, and increasing ocular bioavailability [23]. To improve ocular medication administration, Adwan et al. (2024) recently developed a new chitosan-coated dexamethasone mixed micellar formulation (DEX-CMM, F6) utilizing Pluronic F-127 and Soluplus®. Improved stability and mucoadhesion were facilitated by the modified formulation's high positive zeta potential (+36 mV), low PDI (0.168), and nanosized particle dispersion (~152 nm). The HET-CAM test was used to evaluate biocompatibility. The DEX-CMM (Row A) was found to be non-irritating even after five minutes, showing no symptoms of coagulation, vascular lysis, or bleeding. However, the negative control (saline, Row B) had no harmful effects, but the positive control (10% NaOH, Row C) produced extreme discomfort. The safety and excellent efficacy of the DEX-CMM formulation as a viable ocular delivery technology are confirmed by these results(24). Micellar carriers' primary drawback is that the polymers that are amphiphilic and surfactants employed in their manufacture have been demonstrated to likely irritate the eyes. Micelles' issues with production scale-up are another drawback [25].

Nanosuspension

Nanosuspensions are colloidal dispersions containing medication particles smaller than a micron that utilize surfactants for stabilization. The drug, which is not soluble in water, is dispersed in nanosuspensions, which are free of matrix constituents. They can be applied to increase a drug's solubility in aqueous and lipidic environments [26]. Nanosuspensions improve solubility and bioavailability, especially for poorly soluble drugs, allowing higher drug loading, extended release, and longer retention on the eye surface. This reduces dosing frequency and boosts patient compliance [27]. A new ophthalmic nanosuspension formulation of voriconazole has been developed recently, utilizing Eudragit RS100 and Pharmasolve® to address issues with fungal keratitis treatment, including limited tissue penetration and low ocular bioavailability. Using a quasi-emulsion solvent evaporation process, the formulation yielded uniformly spherical nanoparticles with a mean size of 138±1.3 nm, a stable positive zeta potential ranging from 22.5 to 31.2 mV, and a high entrapment efficiency of 98.6±2.5 percent. Excellent dispersion and physical stability are reflected in these qualities. The in vitro and in vivo tests showed that the nanosuspension had better ocular permeability than conventional voriconazole injection. With better retention, penetration, and therapeutic potential, this nanosuspension presents a viable approach for improved topical ocular administration of voriconazole [28]. Although they have several benefits for ocular medication delivery, nanosuspensions also have certain drawbacks. Physical instability is a major issue over time, nanosuspensions are susceptible to particle aggregation and sedimentation, which can reduce therapeutic effectiveness and shelf life [29].

Nanogel

The word nanogel describes strongly crosslinked hydrogels that are nanoscale and can be either polymers or monomers [30]. These tiny particles are made of networks of crosslinked three-dimensional polymers [31]. They differ from microgels (more than 1 μm) and macrogels (more than 100 μm) because their particle sizes reach several hundred nanometers. Their soft consistency and high-water content offer superior biocompatibility and comfort during administration, while their tiny size facilitates improved penetration through ocular barriers. lowering the frequency of doses and increasing medication absorption [32]. Gels and nanoparticles together demonstrate a potential approach that is thought to represent a significant change in the distribution of medications [33]. A recent study focused on issues such as low solubility, stability, and short retention time by developing a lutein-loaded micelle nanogel to enhance its ocular transport. The improved formulation displayed an entrapment effectiveness of 84.5±1.75%, a zeta potential between –14.2 and+11.3 mV, a particle size of 205.2±15.36 nm, and a PDI of 0.3±0.20. While the F4 formulation showed improved corneal penetration, antioxidant activity (IC₅₀: 55.11 µg/ml), cell survival, and moderate irritancy, FTIR and TEM verified structural integrity. These results suggest that the nanogel is a secure and efficient method of delivering lutein to the eyes [34]. Despite their potential, nanosuspensions frequently have limited ocular retention times because of blinking and tear turnover, physical instability (such as sedimentation and crystal formation), and the possibility of particle aggregation. Furthermore, it is still technically difficult to scale up the production process and achieve a uniform particle size without compromising important quality features [35].

Nanowafer

Nano wafers are small membranes in the shape of discs that contain nanoscale drug reservoirs. Unlike conventional eye drops, it is simple to apply to the surface of the eyes using a fingertip and stays firmly in place even when blinking continuously [36]. In comparison to conventional eye drops, nanowafers provide long-lasting medication administration, effective ocular adhesion, and ease of use, enhancing absorption, lowering dosage frequency, and enhancing therapeutic results [37]. To overcome the drawbacks of using eye drops often, a cysteamine-loaded nanowafer (Cys-NW) was developed to treat corneal cystinosis. Furthermore, the medication remained stable on the nanowafer for up to four months at ambient temperature. According to these results, Cys-NW is a potential substitute for ocular cystinosis treatment since it provides more effectiveness, longer stability, and higher patient compliance [38]. Despite having tremendous potential to improve controlled release and drug retention, nanowafershave several drawbacks. These include the difficulty of increasing output while maintaining quality, the possibility of pain if formulations are not appropriately tailored for various eye shapes and tear film dynamics, and the requirement for precise medication loading to prevent under-or overdose [39].

Microneedles

Microneedles (MNs) are metal or polymer-based devices that vary in size from a few micrometers to 200 μm. Because of their tiny structures, MNs are regarded as minimally invasive. The ability to administer medications precisely and less invasively to the anterior and posterior eye areas makes MNsan excellent tool for ocular drug delivery. They minimize patient pain, decrease systemic exposure, and improve medication absorption. MNs, which are made of biocompatible and biodegradable polymers, are a viable treatment option for a variety of eye conditions because they can circumvent ocular barriers and offer controlled, localized medication delivery [40]. A wearable corneal microneedle patch was recently developed for the effective treatment of infections and damage to the eyes. By enabling prolonged medication administration straight to the ocular tissue, this novel patch improves therapeutic results while reducing pain. The study found that by enhancing medication bioavailability and patient compliance, this significantly less invasive method presents a possible substitute for traditional eye drops [41]. Although microneedles provide accurate, minimally invasive administration, they have drawbacks, including insufficient long-term safety evidence, depth control issues, possible tissue injury, and patient discomfort. It is still difficult to design devices that are consistent with the curved surface of the eye [42].

Cubosomes

Cubosomes are biocompatible nanocarriers made from specific amphiphilic lipids, forming reversed bicontinuous cubic phases with distinct properties [43, 44]. Benefits include their structural resemblance to biological membranes encourages fusion with ocular tissues, boosting medication penetration and bioavailability, while their bioadhesive qualities improve retention on the eye surface [45]. A recent study investigated the use of Annexin V-conjugated cubosomes (L4-ACs) as a targeted ocular delivery method to distribute LM22A-4, a neurotrophic factor mimic, for the protection of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) in glaucoma. By specifically targeting the optic nerve head and the posterior region of the eye, the 17% L4-ACs significantly preserved RGC and enhanced visual function in a rat model of acute intraocular pressure increase, which mimics glaucomatous conditions. Additionally, this formulation showed promise in preventing apoptosis in both in vitro and in vivo environments [46]. Despite the benefits of cubosomes for ocular drug administration, they have significant drawbacks, including drug leakage during storage, toxicity from stabilizers, and manufacturing issues with maintaining particle size and stability. In addition, they might not provide as much control over drug release as other carriers [47].

Stability, scalability and toxicity

Cubosomes face several critical limitations that hinder their clinical translation. One major challenge is that cubosomes are prone to physical instability over time, including drug leakage, particle aggregation, and structural transformations that compromise their cubic lattice [48]. These problems can lead to unpredictable release profiles and reduced therapeutic efficacy during storage or upon exposure to biological fluids. Additionally, cubosomes exhibit high viscosity and are sensitive to environmental factors such as pH and temperature, which complicate both their handling and large-scale manufacturing. These features compromise batch reproducibility and complicate the standardization of formulations. Toxicology is another significant issue, and it varies according to the lipid and stabilizer composition employed in the cubosome synthesis process [43].

Glycerosomes

Glycerosomes are vesicles with a high glycerol content, phospholipids, and water. By enhancing penetration through eye surface barriers, glycerol increases the bilayer fluidity and stability, making the vesicles safe, non-irritating, and efficient for ocular distribution. High amounts of phospholipids and glycerol in their special composition allow glycerosomes to improve ocular medication delivery. Glycerosomes are adaptable and can hold both lipophilic and hydrophilic medications [49, 50]. Gupta et al. recently conducted a study that concentrated on creating natamycin-loaded glycerosomes for improved ocular medication delivery in the treatment of fungal keratitis. The study showed that glycerosomes dramatically outperformed traditional liposomes using the thin-film hydration approach and a 3² factorial design for optimization. The glycerosomes also had better ex vivo corneal penetration. According to these results, glycerosomes provide enhanced natamycin stability, drug loading, and corneal delivery, which makes them a viable treatment option for ocular keratitis disease [51]. Glycerosomes may have drawbacks despite their promising ocular delivery potential, such as vesicle instability brought on by a high glycerol concentration, which may cause the medication to aggregate or leak. Additionally, their size about other vesicular systems may restrict their ability to penetrate far into the eye and lower the effectiveness of corneal absorption [52].

Exosomes

Exosomes are tiny vesicles (30–150 nm) composed of proteins, lipids, and genetic material. Released by most cells, they play key roles in cell communication, immune response, and inflammation regulation [53]. As exosomes are naturally biocompatible, non-toxic, and biodegradable, they are great drug delivery vehicles. Compared to manufactured nanocarriers, exosomes are safer and have a better capacity to penetrate biological barriers since they are natural carriers. They work very well with various drugs and bioactive substances to treat eye disorders. According to a recent study by Zhou et al., mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes (MSC-exo), enriched with miR-204, successfully reduced dry eye disease linked to GVHD by suppressing the IL-6/IL-6R/Stat3 pathway and reprogramming proinflammatory M1 macrophages into an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype. MSC-exoeyedrop therapy resulted in better epithelial repair, more tear production, less fluorescein staining, and lower OSDI ratings in 28 refractory eyes [54]. Exosomes have a lot of potential for ocular medication administration, but challenges, including low separation yield, carrier content heterogeneity, and issues with large-scale manufacturing and purification, hinder their clinical application. Furthermore, their quick elimination and brief half-life can restrict long-term therapeutic benefits in ocular tissues [55].

Stability, scalability and toxicity

Exosomes are naturally biocompatible and very effective at delivering drugs, but they have numerous stability, scalability, and toxicity issues that need to be resolved for clinical translation. Their structural integrity is frequently only maintained at extremely low temperatures (~80 °C), which is not sustainable or feasible for large-scale pharmaceutical use, and limited is known about their shelf life or stability in vivo [56]. The conventional isolation process of ultracentrifugation is ineffective for obtaining therapeutic quantities since it only produces 10–25% of vesicles and can take more than 10 h. Scalability is still expensive and difficult, even with sophisticated techniques like size-exclusion chromatography or multimodal flow-through chromatography that marginally increase yield and purity [57]. In terms of toxicity, exosomes typically have very good safety profiles, but depending on the cellular origin and production process, their biological activity varies, which raises questions about potential immunological reactions or biodistribution patterns, particularly when applied topically or intravenously to delicate tissues like the eye. The entire therapeutic potential of exosomes in ocular applications will require overcoming these production, storage, and biological safety constraints [56].

Gene therapy

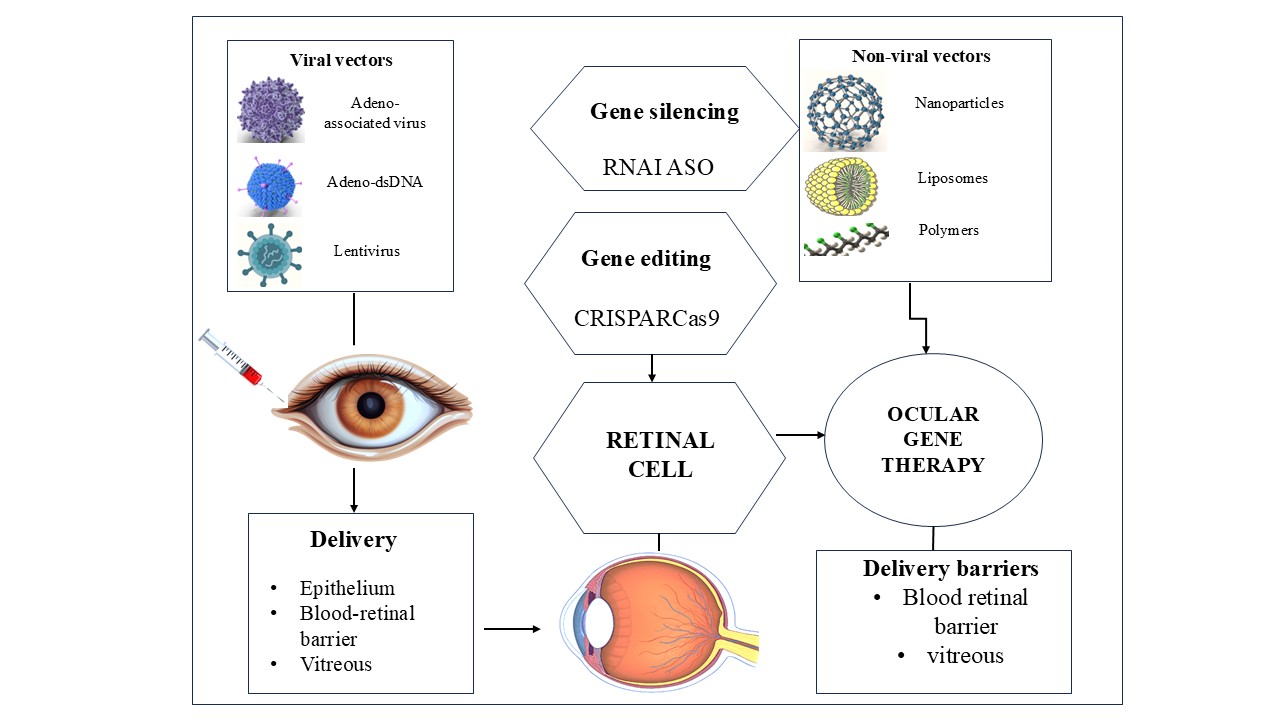

Gene therapy is a promising approach for treating ocular diseases using two main strategies: gene silencing to block harmful proteins and gene insertion or editing to restore protein function. It’s being explored for conditions like AMD and retinal disorders. Delivery involves viral/non-viral vectors, CRISPR-Cas9, and epigenetic tools like RNAi and ASOs [58, 59], which are also depicted in fig. 1. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors uniquely align with ocular gene therapy goals due to their cellular tropism and delivery advantages. When administered via intravitreal injection, AAV serotypes such as AAV2 and AAV8 are adept at crossing the inner limiting membrane to reach retinal ganglion cells, photoreceptors, and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), enabling targeted gene expression with minimal systemic exposure. Moreover, advances in capsid engineering, including surface loop modification and directed evolution, have produced vectors with enhanced retinal tropism and decreased neutralizing antibody binding, improving transduction efficiency in research, including non-human primates. Subretinal delivery, though more invasive, provides direct access to the RPE and photoreceptors, improving transduction precision—this method underpins the approval of therapies like voretigeneneparvovec for LCA. Beyond viral strategies, non-viral mechanisms (e.g., RNA interference, antisense oligonucleotides) also benefit from the ocular immune-privileged status, reducing immunogenicity and facilitating sustained gene silencing without altering genomic DNA [60].

Due to the immune-privileged structure of the eye, gene therapy reduces the need for repeated dosages, minimizes systemic adverse effects, and corrects genetic errors at their source to provide focused, long-lasting treatment for ocular illnesses [59]. A recent 2024 review by Maurya et al. highlights major advancements in ophthalmic gene therapy, emphasizing the eye’s suitability for such treatments due to its immune-privileged nature and accessible structure. The study reports promising progress in treating genetic eye disorders like retinitis pigmentosa, Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), age-related macular degeneration, and Stargardt disease, with LCA-related trials showing the most encouraging outcomes so far. Currently, 33 clinical trials are documented, indicating growing interest and potential in this area. Findings suggest that subretinal delivery of vectors triggers a milder immune response compared to the intravitreal route, underscoring the importance of delivery method selection. Overall, this review concludes that gene therapy is a promising and rapidly evolving strategy in ocular therapeutics, offering hope for managing previously untreatable visual disorders [61]. Gene therapy for eye disorders has several drawbacks despite its potential, such as immunological reactions to viral vectors, restricted gene carrying capacity (particularly with AAVs), possible off-target effects with CRISPR-Cas9, and expensive manufacturing costs that restrict accessibility. Furthermore, additional clinical validation is still needed to ensure the expression's long-term safety and endurance [62].

Fig. 1: Therapeutic approaches and delivery systems utilized in ocular gene therapy, a visual overview of existing and developing approaches for treating various genetic and non-genetic eye disorders

Self-nano-emulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS)

SNEDDS are mixtures of cosurfactants or cosolvents, oil phases, and surfactants. When SNEDDS is mixed with an aqueous phase and gently swirled, oil-in-water nanoemulsions (NEs) with droplet sizes smaller than 200 nm can develop on their own [63]. To improve penetration into ocular tissues, SNEDDS increase the bioavailability and solubility of drugs that aren't very soluble in water. They are effective in treating a range of eye problems since they have a regulated release profile [64]. Jeong et al. developed a self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS) for the ocular administration of flurbiprofen using a Quality by Design (QbD) methodology. The formulation was refined using a Box–Behnken design to achieve a low polydispersity index (0.068), a minimum particle size (24.89 nm), and a high transmittance (74.85%). Stress testing verified the formulation's exceptional stability. In vitro and ex vivo tests showed dramatically improved drug permeation, roughly 2.5 to 4 times better than traditional dispersions, while transmission electron microscopy showed homogenous spherical droplets [65]. Even while SNEDDS is far superior to traditional drug delivery methods, there are still certain drawbacks, such as high excipient concentration in SNEDDS, the possibility of drug precipitation, the difficulty of improving drug loading, and attaining targeted delivery [66].

Olaminosomes

Olaminosomes are oleylamine-based vesicular nanocarriers—a novel class of lipid-based systems designed to enhance drug transport into the eye. Comprising oleic acid, oleylamine, and surfactants, these systems are biocompatible and biodegradable [67]. Their special composition makes it easier to encapsulate lipophilic and hydrophilic pharmaceuticals, increasing the effectiveness of drug loading [68, 69]. Olaminosomes are a potential nanocarrier technology for the efficient treatment of a variety of ocular illnesses because they offer sustained release, improve penetration across ocular barriers, and demonstrate biocompatibility. Ahmed et al. have investigated the possibility of using olaminosomes as a cutting-edge ocular delivery method for Fenticonazole Nitrate (FTN) in the treatment of ocular candidiasis. Using the ethanol injection method and central composite design, the researchers optimized the formulation based on key parameters like entrapment efficiency (EE%), particle size (PS), and drug release over 10 h (Q10h) [68]. Because of their lipid-based structure, olaminosomeshave shown promise for ocular drug delivery; however, they have drawbacks, including physical instability (vesicle fusion or aggregation), manufacturing scale issues, and possible variability in drug release characteristics.

Bilosomes

Bilosomes are advanced lipid nanocarriers that include bile salts, which improve the solubility and bioavailability of medications that are not very soluble in water. Extended drug release and enhanced absorption via the corneal epithelium are made possible by their special bilayer structure, which enables them to pass past ocular barriers [70]. Their lipid content and nanoscale size enhance adhesion and penetration, ensuring the effective delivery of therapeutic substances to the intended eye tissues. Bilosomes promote sustained release, show biocompatibility, increase drug solubility, and facilitate penetration across ocular barriers. These characteristics make bilosomes a potential system of nanocarriers for the efficient treatment of several eye conditions. A recent research study used a Quality by Design strategy to create bilosome-loaded in-situ gels (CIP-BLO-opt-IG3) to improve the ocular administration of ciprofloxacin (CIP). The results suggest that CIP-BLO-opt-IG3 is a promising nanocarrier-based ocular formulation for improving the therapeutic efficacy and residence time of CIP in the eye [7]. Bilosomes may have problems such as batch-to-batch variability, pH sensitivity, and possible bile salt irritation despite their improved permeability and stability. To validate their clinical efficacy and long-term ocular safety, more research is required.

Nanocrystals

Nanocrystals offer an effective method to overcome ocular barriers and greatly increase the bioavailability of medications injected into the eye. Pure medicine particles that are nanosized and stabilized by polymers or surfactants are called nanocrystals [72]. Due to their high surface-area-to-volume ratio, nanocrystals exhibit strong adhesion to ocular membranes, allowing extended ocular retention within the tear film and improved corneal penetration [73]. Recent developments in ocular drug delivery systems based on nanocrystals have shown considerable potential, particularly for improving the solubility and bioavailability of medications that are not highly soluble in water. Because of their superior penetration, robust mucosal adherence, and great drug-loading capability, nanocrystals are unique and perfect for getting beyond ocular barriers. The study concludes that nanocrystals have a lot of promise for developing into medicines that target the posterior portion of the eye with more advancements, particularly in surface modification and formulation technologies [74]. Potential aggregation, limited long-term stability, burst release, and challenges in scaling up production while preserving stability and uniform size are among the problems.

Carbon nanotubes

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are cylinder-shaped nanostructures made of rolled graphene sheets that are known for their large surface area, excellent mechanical strength, and electrical conductivity. Due to their ability to cross ocular barriers and provide controlled and targeted release, they have garnered interest as innovative drug delivery platforms in ophthalmology in recent years [75]. CNTs are perfect for delivering therapeutic substances through covalent or non-covalent attachments because of their exceptional aspect ratio and high surface area-to-volume ratio. Furthermore, they may directly penetrate cell membranes by a nano-needle action due to their thin, needle-like shape, which greatly enhances drug uptake at the cellular level [76]. However, these results are derived from preclinical in vitro and animal studies. There is currently no clinical evidence that CNTs penetrate deep ocular tissues in humans; clinical translation remains to be demonstrated. Their chemical and physical properties frequently impact these negative consequences, including aggregation, length, and surface chemistry. To increase CNTs' compatibility with biological systems and reduce these dangers, researchers are investigating surface modifications, such as covering them with biocompatible polymers. Nevertheless, comprehensive toxicological and pharmacokinetic analyses are still necessary before CNTs may be utilized in clinical ophthalmic applications without risk [77].

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles

Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) are silica-based nanocarriers characterized by pore sizes ranging from 2 to 50 nm. Their high surface area, tunable porosity, and ease of functionalization make them promising candidates for drug delivery applications, including ocular therapies. MSNs can be engineered to respond to specific stimuli, enhancing targeted drug release and minimizing systemic side effects. MSNs usually develop by sol-gel procedures, and one popular technique is the Stöber method [78]. The high drug-loading capacity, stimuli-responsive controlled release, superior stability under physiological settings, and robust MSNs biocompatibility make them useful for ocular drug administration. A recent study developed a novel ocular drug delivery system using 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) loaded into amino-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles (AMSN), further coated with O-carboxymethyl chitosan (AMSN-CMC). These findings suggest that AMSN-CMC-FU offers a promising, non-invasive strategy for improving the therapeutic efficacy of 5-FU in treating ocular cancer [79]. Despite their advantages, MSNs face certain limitations. Variability in particle size, surface charge, and aggregation can affect their biocompatibility and potentially lead to cytotoxicity. Additionally, their complex manufacturing process demands strict control over synthesis conditions [78].

Quantum dots

Nanoscale semiconductor particles known as quantum dots (QDs), which are usually between 2 and 10 nm in size, produce light at certain wavelengths when activated by a specific light source. The color of light they emit is directly influenced by their sizes, smaller QDs emit shorter wavelengths, while larger ones emit longer wavelengths. As a result, their emission properties can be precisely controlled during synthesis by adjusting their size. Ophthalmology uses QDs, which have several important properties. Because of their stability and biocompatibility, cadmium selenide/zinc sulfide (CdSe/Zn S) in QDs are often utilized [80]. A recent review by Zhang et al. highlights the growing potential of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) in the diagnosis and treatment of ophthalmic diseases. Because of their special luminous qualities, CQDs present a viable substitute for conventional dyes in imaging and eye care diagnostics. While still an emerging field, the study concludes that CQDs hold strong potential for advancing both diagnosis and treatment strategies in ophthalmology [81]. QDshave a lot of drawbacks, mostly because of their possible toxicity, cellular damage, inflammation, oxidative stress, and safety issues. CdSe/ZnS QDs have been shown to induce reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, ferroptosis, and mitochondrial damage in retinal pigment epithelial cells and other tissues, raising safety concerns for ocular use. Thus, before QDs are widely used in ophthalmology, thorough in vivo research is essential to assess their clinical safety [82].

Enzymosomes

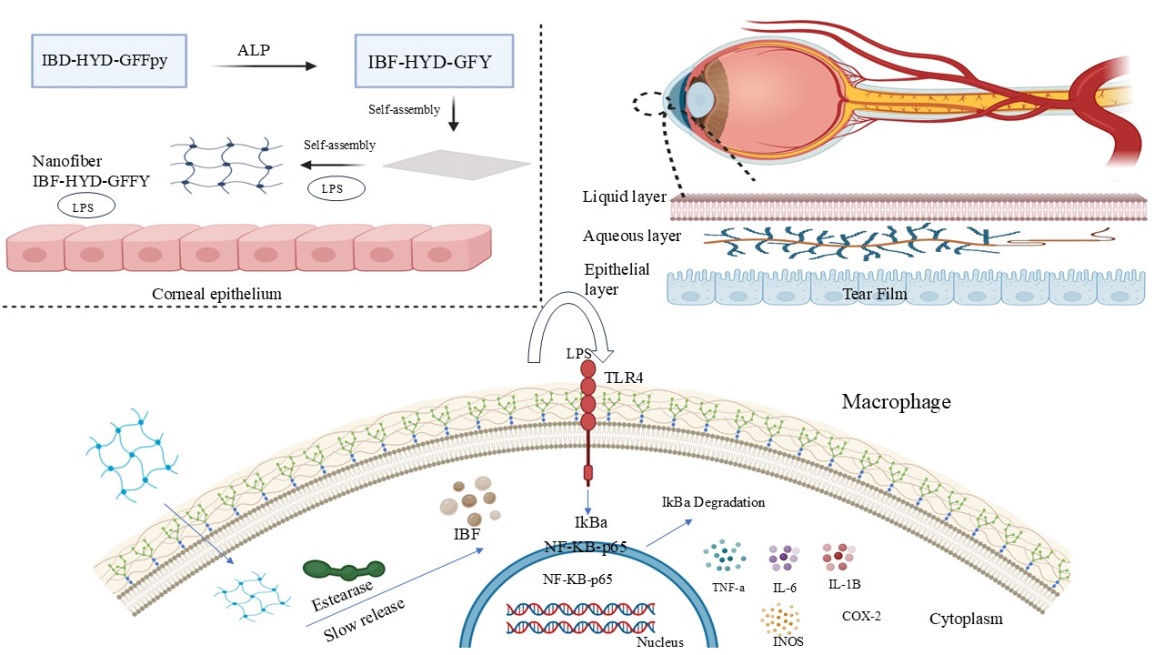

Enzymosomes are advanced drug delivery vehicles developed to take advantage of the eye's enzymatic environment to deliver drugs in a targeted and regulated manner. Compared to the liver, the ocular surface and interior eye structures have a distinct enzymatic profile, which is defined by a reduced expression of cytochrome P450s (CYPs) and most transferases, except glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) whereas several different ocular tissues have many hydrolytic enzymes, particularly esterases. Enzymosomes are designed to stay stable outside cells but release drugs when activated by specific enzymes inside cells. For example, dexamethasone linked to a cell-penetrating peptide via an enzyme-sensitive linker remains stable in the vitreous but is released inside retinal cells by cathepsin D[83]. Enzymosomes enable precise drug release at the target site, enhancing bioavailability and minimizing systemic exposure. A recent study illustrates a novel enzyme-instructed self-assembly (EISA) strategy for ocular drug delivery using a phosphorylated ibuprofen-peptide conjugate (IBF-HYD-GFFpY), which is also described in fig. 2. In vivo testing in a rabbit model of endotoxin-induced uveitis (EIU) demonstrated that the EISA-based eye drops were as effective as commercial diclofenac eye drops, while causing minimal irritation and offering improved drug residence time [84]. Enzymosomes face challenges such as species-specific enzyme variability, which complicates translating animal studies to humans. Incomplete knowledge of ocular enzymes and complex formulation processes also hinders development. Additionally, unintended interactions with non-target enzymes may reduce efficacy and safety.

Fig. 2: Enzyme-triggered self-assembly enables localized, sustained anti-inflammatory drug action at the ocular site

Patents

Patents are crucial in advancing ocular drug delivery by protecting innovative technologies and encouraging investment in research and development. They provide exclusivity to inventors, allowing them to recoup development costs and funds for further innovations. Table 1 depicts a list of patents associated with novel ocular drug delivery systems.

Table 1: List of patents associated with novel ocular drug delivery systems

| S. No. | Patent number | Formulations | Description | References |

| 1 | US 10,195,212 B2 | Nanocarriers containing glucocorticoids | Glucocorticoid-loaded nanoparticles to reduce neovascularization and corneal transplant rejection. | [89] |

| 2 | US9017725B2 | Nano micellar formulation containing corticosteroid encapsulated with Octoxynol-40 (1.0%–3.0% w/v) and Vitamin E TPGS (3.0%–5.0% w/v) in aqueous solution | A patent discloses an ophthalmic topical medication delivery method, particularly for managing disorders affecting the posterior ocular segments. Aqueous ophthalmic solution containing nano micelles encapsulating water-insoluble medications such as corticosteroids is part of the formulation. Octoxynol-40 (1.0% – 3.0% w/v) and Vitamin E TPGS (3.0% – 5.0% w/v) are stable in these micelles, and the solution is buffered to a pH of 5.0–8.0. | [90] |

| 3 | US10272040B2 | Liposomal formulation for the transport of drugs | The formulation includes liposomes with a prostaglandin drug or its derivative and at least one lipid bilayer for better ocular medication delivery. | [91] |

| 4 | IN201911040868 | Glycerosomes of Natamycin for Treatment of Ophthalmic Fungal Keratitis. | Natamycin-loaded glycerosomes for eye drops provide safe ocular administration, high entrapment, and penetration. | [92] |

Approval and clinical status of delivery systems based on nanotechnology for eye disorders

Several ocular drug delivery methods based on nanotechnology are now undergoing clinical review as described in table 2, underscoring their expanding contribution to the advancement of ophthalmic therapies. Although there has been some success in the previous 20 years in gaining regulatory approval for nanocarriers, more systems, particularly those intended to treat eye conditions, are expected to hit the pharmaceutical market in the years to come.

Furthermore, Ocular nanomedicines hold great potential; however, obtaining regulatory approval remains challenging, as there are no clear guidelines for nanoformulations. Instead of using specific frameworks for nanoparticles, the FDA and EMA presently assess medications based on nanocarriers on an individual basis. This approach places significant emphasis on detailed physicochemical characterization—such as particle size distribution, surface charge, and encapsulation efficiency—and the consistent demonstration of batch-to-batch reproducibility, which is particularly challenging for heterogeneous nanosystems. Regulatory bodies also require robust evidence correlating in vitro and animal data with human ocular safety and efficacy, alongside compliance with GMP manufacturing standards—a difficult leap from lab-scale research. The FDA has issued draft guidance for drug products containing nanomaterials, urging early dialogue and thorough characterization throughout development.

Table 2: List of clinical trials on ocular drug delivery methods based on nanotechnology

| S. No. | Clinical trial ID | Nano formulations | Objectives | Current status | Outcomes |

| 1 | NCT04147650 | Voclosporin Ophthalmic Solution (nanomicelles) | To evaluate the safety and effectiveness of a voclosporin nanomicellar formulation for treating dry eye. | Completed phase 3 | ≥10 mm increase in tear production at Week 4. |

| 2 | NCT02845674 | Cyclosporine OTX-101 (nanomicelles) | Assess the efficiency of cyclosporine nanomicelles in the treatment of keratoconjunctivitis Sicca. | Completed Phase 3 | No major safety concerns over 40 w. |

| 3 | NCT01576952 | (Micelles) ISV-303 | Research the effectiveness of the ISV-303 micellar formulation in reducing inflammation post-cataract surgery. | Completed phase 3 | Inflammation was resolved by Day 15 without rescue meds. |

| 4 | NCT00738361 | (Nanoparticles) Paclitaxel | Analyze how paclitaxel nanoparticles are used to treat intraocular melanoma. | Completed phase 2 | Partial or complete tumor reduction by MRI criteria. |

| 5 | NCT03093701 | (Liposomes) TLC399-ProDex |

Examine the safety and effectiveness of liposomes (TLC399-ProDex) in treating macular edema brought on by blockage of the retinal vein. | Completed phase 2 | ≥15-letter gain in BCVA without rescue treatment. |

| 6 | NCT03785340 | (Nanoemulsion)Brimonidine Tartrate | Examine the brimonidine tartrate nanoemulsion's effectiveness and safety in treating dry eye. | Completed phase3 | |

| 7 | NCT04912843 | (Gene Therapy) NR082 via AAV2 vector | Examine gene replacement treatment for Leber's Hereditary Optic Neuropathy using AAV. | Active, not recruiting (Phase 2/3) | Recruiting |

| 8 | NCT06771427 | Exosome Proteomics | To examine exosomal protein indicators in individuals suffering from dry eye disease and Sjögren's syndrome | Not yet recruiting | Recruiting |

Comparative evaluation of key nanocarrier systems

The main characteristics of nanocarriers, including manufacturing complexity, depth of ocular penetration, and drug loading efficiency, are compared effectively in table 3. Liposomes, for example, often achieve 85–95% drug loading and can reach the retina when formulated below 50 nm in size. Dendrimers offer adjustable surface chemistry but may exhibit variable bioavailability and moderate production costs. Carbon nanotubes and quantum dots, although effective in vitro, remain expensive to manufacture and raise long-term safety concerns due to potential retinal accumulation. These practical and safety-related challenges explain why only a small fraction of ocular nanocarriers, fewer than 10 out of over 20 discussed, have reached clinical trials. The primary barriers include poor scalability, regulatory hurdles, and inconsistent long-term safety data, all of which hinder translation into approved therapeutics.

Table 3: Comparative evaluation of nanocarrier systems in ocular drug delivery

| Nano-carrier | Drug loading capacity (%) | Corneal/Retinal penetration |

Manufacturing Complexity | Long-term biocompatibility | References |

| Liposomes | High (80-95%) | Moderate corneal penetration, limited retinal access unless<50 nm | Low and well-established technique | Generally safe and biodegradable | [85] |

| Dendrimers | Moderate-to high (50-90%) | Good corneal and conjunctival preparation, variable retinal reach | Moderate, precise synthesis required | Cationic forms may irritate, but PEGylation improves safety | [86] |

| Polymeric micelles | Moderate (60-80%) | Effective corneal delivery, limited retinal penetration | Low to moderate, scalable | Biodegradable polymer is generally safe | [87] |

| Carbon nanotubes | Very high (>90%) | High tissue penetration in preclinical models only, no human data yet | Highly requires purification and functionalization | Concerns over retinal accumulation and inflammation with chronic use | [88] |

| Quantum dots | High (>85%) | Good retinal labeling in preclinical models, only still no human data yet | Highly requires cadmium core purification | Potential for cadmium toxicity and oxidative stress; long-term safety unclear | [56] |

| SLNs (Solid Lipid Nanoparticles) | Moderate to high (60-65%) |

Effective corneal penetration and limited posterior segment delivery | Low to moderate, simpler than NLCs | Good biocompatibility, Limited inflammation | [11] |

| NLCs (Nano-Structured Lipid Nanocarriers) | High (75-95%) | Improved corneal And conjunctival penetration, enhanced posterior retention |

Moderate, requires lipid blend optimization | Good long-term safety, better stability, and drug retention than SLNs | [13] |

Challenges in translating nano-drug delivery systems for treating eye conditions in clinical settings

The translation of nano-drug delivery systems (NODS) for ocular application presents difficulties, such as the need for precise animal models, expensive regulatory approvals, and complex eye barriers. The characteristics of nanoparticles change, and instability is a problem when scaling up from the lab to industry. Multi-step fabrication results in problems with quality control and poor repeatability. Effectiveness is impacted by slight formulation modifications, and the preclinical failure of many nanocarriers can be traced to their long-term biocompatibility and safety concerns. Materials such as carbon nanotubes and quantum dots, while promising in vitro, have shown potential for chronic toxicity, including retinal accumulation and oxidative stress. Additionally, a disconnect often exists between preclinical models and human ocular physiology, making efficacy predictions unreliable. Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA also lack clear, harmonized guidelines for ocular nanomedicines, further delaying clinical advancement. These combined toxicological and translational challenges continue to hinder the progression of most systems into late-stage trials or market approval.

CONCLUSION

Nanomedicine presents significant potential to transform ocular drug delivery. This review demonstrates how enhancing ocular bioavailability using nanotechnology can successfully overcome the drawbacks of traditional methods. Nanoparticle-based systems enable controlled drug release, enhanced tissue penetration, and targeted delivery, thereby increasing therapeutic outcomes and reducing adverse effects. Advances such as surface engineering and customized nanoparticle designs provide disease-specific treatment solutions. However, challenges like biocompatibility, large-scale production, and regulatory hurdles still need to be overcome. Future research should focus on improving formulations, learning more about their workings, and assisting with clinical validation to ensure efficacy and safety. The discipline might make significant strides if nanotechnology for ocular applications continues to grow, since it can significantly improve patient outcomes and treatment outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the institute's management for their unwavering support, inspiration, and wealth of expertise, which helped generate this review.

FUNDING

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. DB reviewed literature resources and wrote the first draft. RM and AR performed conceptualization, curation of literature, and editing. RKM validated scientific content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Mc Cormick I, Mactaggart I, Resnikoff S, Muirhead D, Murthy GV, Silva JC. Eye health indicators for universal health coverage: results of a global expert prioritisation process. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022 Jul;106(7):893-901. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-318481, PMID 33712481.

Anshika Garg, Megha, Anuradha Verma, Manish Singh. Visionary nanomedicine: transforming ocular therapy with nanotechnology based drug delivery systems. Int J of Pharm Sci. 2025;3(2):63-76. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.14786780.

Patel A, Havelikar U, Sharma V, Yadav S, Rathee S, Ghosh B. A comprehensive review on proniosomes: a new concept in ocular drug delivery. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2023 Sep 15;15(5):1-9. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2023v15i5.3048.

Lanier OL, Manfre MG, Bailey C, Liu Z, Sparks Z, Kulkarni S. Review of approaches for increasing ophthalmic bioavailability for eye drop formulations. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2021 Apr;22(3):107. doi: 10.1208/s12249-021-01977-0, PMID 33719019.

Tsung TH, Tsai YC, Lee HP, Chen YH, Lu DW. Biodegradable polymer-based drug delivery systems for ocular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Aug 19;24(16):12976. doi: 10.3390/ijms241612976, PMID 37629157.

Tang Z, Fan X, Chen Y, Gu P. Ocular nanomedicine. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022 May;9(15):e2003699. doi: 10.1002/advs.202003699, PMID 35150092.

Kurul F, Turkmen H, Cetin AE, Topkaya SN. Nanomedicine: how nanomaterials are transforming drug delivery, bio-imaging and diagnosis. Next Nanotechnol. 2025;7:100129. doi: 10.1016/j.nxnano.2024.100129.

Lopez KL, Ravasio A, Gonzalez Aramundiz JV, Zacconi FC. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) prepared by microwave and ultrasound-assisted synthesis: promising green strategies for the nanoworld. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Apr 25;15(5):1333. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15051333, PMID 37242575.

Duan Y, Dhar A, Patel C, Khimani M, Neogi S, Sharma P. A brief review on solid lipid nanoparticles: part and parcel of contemporary drug delivery systems. RSC Adv. 2020;10(45):26777-91. doi: 10.1039/d0ra03491f, PMID 35515778.

Phalak SD, Bodke V, Yadav R, Pandav S, Ranaware M. A systematic review on NANO drug delivery system: solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN). Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2024 Jan 15;16(1):10-20. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2024v16i1.4020.

Gugleva V, Andonova V. Recent progress of solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers as ocular drug delivery platforms. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023 Mar 22;16(3):474. doi: 10.3390/ph16030474, PMID 36986574.

Sun K, Hu K. Preparation and characterization of tacrolimus-loaded slns in situ gel for ocular drug delivery for the treatment of immune conjunctivitis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021 Jan;15:141-50. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S287721, PMID 33469266.

Viegas C, Patricio AB, Prata JM, Nadhman A, Chintamaneni PK, Fonte P. Solid lipid nanoparticles vs. nanostructured lipid carriers: a comparative review. Pharmaceutics. 2023 May 25;15(6):1593. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15061593, PMID 37376042.

Santonocito D, Barbagallo I, Distefano A, Sferrazzo G, Vivero Lopez M, Sarpietro MG. Nanostructured lipid carriers aimed to the ocular delivery of mangiferin: in vitro evidence. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Mar 15;15(3):951. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15030951, PMID 36986812.

Makoni PA, Wa Kasongo K, Walker RB. Short-term stability testing of efavirenz-loaded solid lipid nanoparticle (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) dispersions. Pharmaceutics. 2019 Aug 8;11(8):397. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11080397, PMID 31398820.

Farooq U, O Reilly NJ, Ahmed Z, Gasco P, Raghu Raj Singh T, Behl G. Design of liposomal nanocarriers with a potential for combined dexamethasone and bevacizumab delivery to the eye. Int J Pharm. 2024 Apr;654:123958. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.123958, PMID 38442797.

Batur E, Ozdemir S, Durgun ME, Ozsoy Y. Vesicular drug delivery systems: promising approaches in ocular drug delivery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024 Apr 16;17(4):511. doi: 10.3390/ph17040511, PMID 38675470.

Lombardo D, Kiselev MA. Methods of liposomes preparation: formation and control factors of versatile nanocarriers for biomedical and nanomedicine application. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Feb 28;14(3):543. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14030543, PMID 35335920.

Chen X, Wu J, Lin X, Wu X, Yu X, Wang B. Tacrolimus-loaded cationic liposomes for dry eye treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:838168. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.838168, PMID 35185587.

Su Y, Fan X, Pang Y. Nano based ocular drug delivery systems: an insight into the preclinical/clinical studies and their potential in the treatment of posterior ocular diseases. Biomater Sci. 2023;11(13):4490-507. doi: 10.1039/d3bm00505d, PMID 37222479.

Ozsoy Y, Gungor S, Kahraman E, Durgun ME. Polymeric micelles as a novel carrier for ocular drug delivery. In: Nanoarchitectonics in biomedicine. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2019. p. 85-117. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-816200-2.00005-0.

El Shahed SA, Hassan DH, El Nabarawi MA, El Setouhy DA, Abdellatif MM. Polymeric mixed micelle-loaded hydrogel for the ocular delivery of fexofenadine for treating allergic conjunctivitis. Polymers. 2024 Aug 7;16(16):2240. doi: 10.3390/polym16162240, PMID 39204460.

Durgun ME, Gungor S, Ozsoy Y. Micelles: promising ocular drug carriers for anterior and posterior segment diseases. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2020 Jul 1;36(6):323-41. doi: 10.1089/jop.2019.0109, PMID 32310723.

Adwan S, Al Akayleh F, Qasmieh M, Obeidi T. Enhanced ocular drug delivery of dexamethasone using a chitosan-coated Soluplus®-based mixed micellar system. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Oct 29;16(11):1390. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16111390, PMID 39598514.

Kaushal N, Kumar M, Tiwari A, Tiwari V, Sharma K, Sharma A. Polymeric micelles loaded in situ gel with prednisolone acetate for ocular inflammation: development and evaluation. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2023 Aug;18(20):1383-98. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2023-0123, PMID 37702303.

Gorle A, Nerkar P, Ola M, Bhaskar R, Khalane V. Formulation and evaluation of polymeric ocular nanosuspension containing azelastine hydrochloride. BCA. 2024 Sep 25;24(2):2809. doi: 10.51470/BCA.2024.24.2.2809.

Suriyaamporn P, Pornpitchanarong C, Pamornpathomkul B, Patrojanasophon P, Rojanarata T, Opanasopit P. Ganciclovir nanosuspension loaded detachable microneedles patch for enhanced drug delivery to posterior eye segment. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2023 Oct;88:104975. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2023.104975.

Qin T, Dai Z, Xu X, Zhang Z, You X, Sun H. Nanosuspension as an efficient carrier for improved ocular permeation of voriconazole. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2021 Feb;22(2):245-53. doi: 10.2174/1389201021999200820154918, PMID 32867650.

Guven UM, Yenilmez E. Olopatadine hydrochloride loaded kollidon® SR nanoparticles for ocular delivery: nanosuspension formulation and in vitro-in vivo evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2019 Jun;51:506-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.03.016.

Wu Y, Tao Q, Xie J, Lu L, Xie X, Zhang Y. Advances in nanogels for topical drug delivery in ocular diseases. Gels. 2023 Apr 2;9(4):292. doi: 10.3390/gels9040292, PMID 37102904.

Suhail M, Rosenholm JM, Minhas MU, Badshah SF, Naeem A, Khan KU. Nanogels as drug delivery systems: a comprehensive overview. Ther Deliv. 2019 Nov;10(11):697-717. doi: 10.4155/tde-2019-0010, PMID 31789106.

Xu H, Li S, Liu YS. Nanoparticles in the diagnosis and treatment of vascular aging and related diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Jul 11;7(1):231. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01082-z, PMID 35817770.

Li C, Obireddy SR, Lai WF. Preparation and use of nanogels as carriers of drugs. Drug Deliv. 2021 Jan;28(1):1594-602. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2021.1955042, PMID 34308729.

Shetty R, Jose J, Maliyakkal N, DSS, Johnson RP, Bandiwadekar A. Micelle nanogel-based drug delivery system for lutein in ocular administration. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2025 Feb 28;398(8):10611-23. doi: 10.1007/s00210-025-03919-0, PMID 40019526.

Amrutkar CS, Patil SB. Nanocarriers for ocular drug delivery: recent advances and future opportunities. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023 Jun;71(6):2355-66. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1893_22, PMID 37322644.

Meng T, Zheng J, Shin CS, Gao N, Bande D, Sudarjat H. Combination nanomedicine strategy for preventing high-risk corneal transplantation rejection. ACS Nano. 2024 Aug 6;18(31):20679-93. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.4c06595, PMID 39074146.

Dourado LF, Silva CN, Gonçalves RS, Inoue TT, De Lima ME, Cunha Junior AS. Improvement of PnPP-19 peptide bioavailability for glaucoma therapy: design and application of nanowafers based on PVA. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022 Aug;74:103501. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103501.

Marcano DC, Shin CS, Lee B, Isenhart LC, Liu X, Li F. Synergistic cysteamine delivery nanowafer as an efficacious treatment modality for corneal cystinosis. Mol Pharm. 2016 Oct 3;13(10):3468-77. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00488, PMID 27571217.

Liu LC, Chen YH, Lu DW. Overview of recent advances in nano-based ocular drug delivery. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Oct 19;24(20):15352. doi: 10.3390/ijms242015352, PMID 37895032.

Rojekar S, Parit S, Gholap AD, Manchare A, Nangare SN, Hatvate N. Revolutionizing eye care: exploring the potential of microneedle drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Oct 30;16(11):1398. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16111398, PMID 39598522.

Jiang X, Liu S, Chen J, Lei J, Meng W, Wang X. A transformative wearable corneal microneedle patch for efficient therapy of ocular injury and infection. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025 Mar;12(12):e2414548. doi: 10.1002/advs.202414548, PMID 39887635.

Gupta P, Yadav KS. Applications of microneedles in delivering drugs for various ocular diseases. Life Sci. 2019 Nov;237:116907. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116907, PMID 31606378.

Sivadasan D, Sultan MH, Alqahtani SS, Javed S. Cubosomes in drug delivery a comprehensive review on its structural components, preparation techniques and therapeutic applications. Biomedicines. 2023 Apr 7;11(4):1114. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11041114, PMID 37189732.

Manorma MR, Mazumder R, Rani A, Budhori R, Kaushik A. Current measures against ophthalmic complications of diabetes mellitus a short review. Int J App Pharm. 2021 Nov 7;13(6):54-65. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2021v13i6.42876.

Umar H, Wahab HA, Gazzali AM, Tahir H, Ahmad W. Cubosomes: design, development and tumor-targeted drug delivery applications. Polymers. 2022 Jul 31;14(15):3118. doi: 10.3390/polym14153118, PMID 35956633.

Ding Y, Chow SH, Chen J, Brun AP, Wu CM, Duff AP. Targeted delivery of LM22A-4 by cubosomes protects retinal ganglion cells in an experimental glaucoma model. Acta Biomater. 2021 May;126:433-44. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.03.043, PMID 33774200.

Nasr M, Teiama M, Ismail A, Ebada A, Saber S. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of cubosomal nanoparticles as an ocular delivery system for fluconazole in treatment of keratomycosis. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2020 Dec;10(6):1841-52. doi: 10.1007/s13346-020-00830-4, PMID 32779112.

Kamble SN RS. A comprehensive review on cubosomes. Int J of Pharm Sci. 2024 May 29;2(5):1728-39. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.11388304. [Last accessed on 06 Jul 2025].

Gupta P, Mazumder R, Padhi S. Glycerosomes: advanced liposomal drug delivery system. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2020;82(3):385-97. doi: 10.36468/pharmaceutical-sciences.661.

Sharma D, Rani A, Singh VD, Shah P, Sharma S, Kumar S. Glycerosomes: novel nano-vesicles for efficient delivery of therapeutics. Recent Adv Drug Deliv Formul. 2023 Sep;17(3):173-82. doi: 10.2174/0126673878245185230919101148, PMID 37921130.

Gupta P, Mazumder R, Padhi S. Development of natamycin-loaded glycerosomes a novel approach to defend ophthalmic keratitis. IJPER. 2020 May 29;54(2s):s163-72. doi: 10.5530/ijper.54.2s.72.

Naguib MJ, Hassan YR, Abd Elsalam WH. 3D printed ocusert laden with ultra-fluidic glycerosomes of ganciclovir for the management of ocular cytomegalovirus retinitis. Int J Pharm. 2021 Sep;607:121010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121010, PMID 34391852.

Manukonda R, Attem J, Yenuganti VR, Kaliki S, Vemuganti GK. Exosomes in the visual system: new avenues in ocular diseases. Tumour Biol. 2022 Aug 9;44(1):129-52. doi: 10.3233/TUB-211543, PMID 35964221.

Zhou T, He C, Lai P, Yang Z, Liu Y, Xu H. miR-204–containing exosomes ameliorate GVHD-associated dry eye disease. Sci Adv. 2022 Jan 14;8(2):eabj9617. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj9617, PMID 35020440.

An S, Anwar K, Ashraf M, Lee H, Jung R, Koganti R. Wound healing effects of mesenchymal stromal cell secretome in the cornea and the role of exosomes. Pharmaceutics. 2023 May 13;15(5):1486. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15051486, PMID 37242728.

Palakurthi SS, Shah B, Kapre S, Charbe N, Immanuel S, Pasham S. A comprehensive review of challenges and advances in exosome-based drug delivery systems. Nanoscale Adv. 2024;6(23):5803-26. doi: 10.1039/d4na00501e, PMID 39484149.

Bonner SE, Van De Wakker SI, Phillips W, Willms E, Sluijter JP, Hill AF. Scalable purification of extracellular vesicles with high yield and purity using multimodal flowthrough chromatography. J Extracell Biol. 2024 Feb;3(2):e138. doi: 10.1002/jex2.138, PMID 38939900.

Tawfik M, Chen F, Goldberg JL, Sabel BA. Nanomedicine and drug delivery to the retina: current status and implications for gene therapy. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2022 Dec;395(12):1477-507. doi: 10.1007/s00210-022-02287-3, PMID 36107200.

Amador C, Shah R, Ghiam S, Kramerov AA, Ljubimov AV. Gene therapy in the anterior eye segment. Curr Gene Ther. 2022;22(2):104-31. doi: 10.2174/1566523221666210423084233, PMID 33902406.

Kellish PC, Marsic D, Crosson SM, Choudhury S, Scalabrino ML, Strang CE. Intravitreal injection of a rationally designed AAV capsid library in non-human primate identifies variants with enhanced retinal transduction and neutralizing antibody evasion. Mol Ther. 2023 Dec;31(12):3441-56. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.10.001, PMID 37814449.

Maurya R, Vikal A, Narang RK, Patel P, Kurmi BD. Recent advancements and applications of ophthalmic gene therapy strategies: a breakthrough in ocular therapeutics. Exp Eye Res. 2024 Aug;245:109983. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2024.109983, PMID 38942133.

Dhurandhar D, Sahoo NK, Mariappan I, Narayanan R. Gene therapy in retinal diseases: a review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021 Sep;69(9):2257-65. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3117_20, PMID 34427196.

Buya AB, Beloqui A, Memvanga PB, Preat V. Self-nano-emulsifying drug-delivery systems: from the development to the current applications and challenges in oral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2020 Dec 9;12(12):1194. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12121194, PMID 33317067.

Vikash B, Shashi PNK, Pandey NK, Kumar B, Wadhwa S, Goutam U. Formulation and evaluation of ocular self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system of brimonidine tartrate. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2023 Mar;81:104226. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2023.104226.

Jeong JH, Yoon TH, Ryu SW, Kim MG, Kim GH, Oh YJ. Quality by design (QbD)-based development of a self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system for the ocular delivery of flurbiprofen. Pharmaceutics. 2025 May 9;17(5):629. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics17050629, PMID 40430920.

Dehghani M, Zahir Jouzdani F, Shahbaz S, Andarzbakhsh K, Dinarvand S, Fathian Nasab MH. Triamcinolone loaded self nano-emulsifying drug delivery systems for ocular use: an alternative to invasive ocular surgeries and injections. Int J Pharm. 2024 Mar;653:123840. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.123840, PMID 38262585.

Ahmed S, Amin MM, Sayed S. Ocular drug delivery: a comprehensive review. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2023 Feb 14;24(2):66. doi: 10.1208/s12249-023-02516-9, PMID 36788150.

Ahmed S, Amin MM, El Korany SM, Sayed S. Pronounced capping effect of olaminosomes as nanostructured platforms in ocular candidiasis management. Drug Deliv. 2022 Dec 31;29(1):2945-58. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2022.2120926, PMID 36073061.

Abd Elsalam WH, ElKasabgy NA. Mucoadhesive olaminosomes: a novel prolonged release nanocarrier of agomelatine for the treatment of ocular hypertension. Int J Pharm. 2019 Apr;560:235-45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.01.070, PMID 30763680.

Kaurav H, Tripathi M, Kaur SD, Bansal A, Kapoor DN, Sheth S. Emerging trends in bilosomes as therapeutic drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics. 2024 May 23;16(6):697. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16060697, PMID 38931820.

Alsaidan OA, Zafar A, Yasir M, Alzarea SI, Alqinyah M, Khalid M. Development of ciprofloxacin-loaded bilosomes in situ gel for ocular delivery: optimization in vitro characterization ex-vivo permeation and antimicrobial study. Gels. 2022 Oct 25;8(11):687. doi: 10.3390/gels8110687, PMID 36354595.

Bassani CL, Van Anders G, Banin U, Baranov D, Chen Q, Dijkstra M. Nanocrystal assemblies: current advances and open problems. ACS Nano. 2024 Jun 11;18(23):14791-840. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c10201, PMID 38814908.

Geng F, Fan X, Liu Y, Lu W, Wei G. Recent advances in nanocrystal based technologies applied for ocular drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2024 Feb;21(2):211-27. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2024.2311119, PMID 38271023.

Geng F, Fan X, Liu Y, Lu W, Wei G. Recent advances in nanocrystal based technologies applied for ocular drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2024 Feb;21(2):211-27. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2024.2311119, PMID 38271023.

Sonowal L, Gautam S. Ocular drug delivery strategies using carbon nanotubes: a perspective. Mater Lett. 2025 Jan;379:137642. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2024.137642.

Demirci H, Wang Y, Li Q, Lin CM, Kotov NA, Grisolia AB. Penetration of carbon nanotubes into the retinoblastoma tumor after intravitreal injection in LH BETA T AG transgenic mice reti-noblastoma model. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2020;15(4):446-52. doi: 10.18502/jovr.v15i4.7778, PMID 33133434.

Sciortino N, Fedeli S, Paoli P, Brandi A, Chiarugi P, Severi M. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes for drug delivery: efficiency related to length and incubation time. Int J Pharm. 2017 Apr;521(1-2):69-72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.02.023, PMID 28229946.

Rodrigues FS, Campos A, Martins J, Ambrosio AF, Campos EJ. Emerging trends in nanomedicine for improving ocular drug delivery: light-responsive nanoparticles mesoporous silica nanoparticles and contact lenses. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2020 Dec 14;6(12):6587-97. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c01347, PMID 33320633.

Alhowyan AA, Kalam MA, Iqbal M, Raish M, El Toni AM, Alkholief M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles coated with carboxymethyl chitosan for 5-fluorouracil ocular delivery: characterization in vitro and in vivo studies. Molecules. 2023 Jan 27;28(3):1260. doi: 10.3390/molecules28031260, PMID 36770926.

Huang K, Liu X, LV Z, Zhang D, Zhou Y, Lin Z. MMP9-responsive graphene oxide quantum dot-based nano-in-micro drug delivery system for combinatorial therapy of choroidal neovascularization. Small. 2023 Sep;19(39):e2207335. doi: 10.1002/smll.202207335, PMID 36871144.

Zhang X, Yang L, Wang F, Su Y. Carbon quantum dots for the diagnosis and treatment of ophthalmic diseases. Hum Cell. 2024 Aug 2;37(5):1336-46. doi: 10.1007/s13577-024-01111-9, PMID 39093514.

Biswal MR, Bhatia S. Carbon dot nanoparticles: exploring the potential use for gene delivery in ophthalmic diseases. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021 Apr 6;11(4):935. doi: 10.3390/nano11040935, PMID 33917548.

Bhattacharya M, Sadeghi A, Sarkhel S, Hagström M, Bahrpeyma S, Toropainen E. Release of functional dexamethasone by intracellular enzymes: a modular peptide based strategy for ocular drug delivery. J Control Release. 2020 Nov;327:584-94. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.09.005, PMID 32911015.

Hu Y, Wang Y, Deng J, Ding X, Lin D, Shi H. Enzyme instructed self assembly of peptide drug conjugates in tear fluids for ocular drug delivery. J Control Release. 2022 Apr;344:261-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.03.011, PMID 35278493.

Jacob S, Nair AB, Shah J, Gupta S, Boddu SH, Sreeharsha N. Lipid nanoparticles as a promising drug delivery carrier for topical ocular therapy an overview on recent advances. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Feb 27;14(3):533. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14030533, PMID 35335909.

Wang J, Li B, Kompella UB, Yang H. Dendrimer and dendrimer gel derived drug delivery systems: breaking bottlenecks of topical administration of glaucoma medications. MedComm Biomater Appl. 2023 Mar;2(1):e30. doi: 10.1002/mba2.30, PMID 38562247.

Li S, Chen L, Fu Y. Nanotechnology-based ocular drug delivery systems: recent advances and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnology. 2023 Jul 22;21(1):232. doi: 10.1186/s12951-023-01992-2, PMID 37480102.

Demirci H, Wang Y, Li Q, Lin CM, Kotov NA, Grisolia AB. Penetration of carbon nanotubes into the retinoblastoma tumor after intravitreal injection in LH BETA T AG transgenic mice reti-noblastoma model. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2020;15(4):446-52. doi: 10.18502/jovr.v15i4.7778, PMID 33133434.

Justin SH, Qing P, Qingguo X, Nicholas JB, Walter JS, Bing W. Glucocorticoid-loaded nanoparticles for prevention of corneal allograft rejection and neovascularization, US10195212B2; 2017.

Ashim KM, Poonam RV, Ulrich MG. Topical drug delivery systems for ophthalmic use, US9017725B2; 2015.

Subramanian V, Jayaganesh VN, Tina W, Yin Chiang FB. Liposomal formulation for ocular drug delivery, US10272040B2; 2019.

Mazumder R, Swarupanjali P, Gupta P. Glycerosomes of natamycin for treatment of ophthalmic fungal keratitis, I. P. 201911040868 2019.