Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 130-151Reviewl Article

MOLECULAR AND EPIGENETIC MECHANISMS OF COVID-19-RELATED CARDIOVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS: MULTIOMICS BIOMARKERS AND PRECISION MEDICINE APPROACHES

KETAKI DAWALE*, PANKAJ JAMBHOLKAR, VASANT WAGH

Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College (JNMC) DMIHER (Deemed to be University), Wardha, Maharashtra-442001, India

*Corresponding author: Ketaki Dawale; *Email: ketakidawale14@gmail.com

Received: 11 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 26 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

COVID-19 has emerged as a significant precipitant of acute cardiovascular complications, collectively termed COVID-19-associated acute cardiovascular syndrome. Approximately one-third of hospitalized patients experience myocardial injury, with elevated cardiac troponins correlating with disease severity and mortality. The pathogenesis involves direct viral invasion of cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells via the ACE2 receptor, immune-mediated inflammation (notably cytokine storm), endothelial dysfunction, and prothrombotic states. These mechanisms are further modulated by genetic and epigenetic factors, including DNA methylation changes and host genetic polymorphisms, which influence individual susceptibility to cardiac complications. Multiomics integration—encompassing microRNA expression, exosomal biomarkers, glycomic profiling, and genomic data—has enabled the identification of novel molecular signatures for risk stratification and therapeutic targeting. For instance, specific miRNA signatures have been shown to predict responsiveness to anti-inflammatory therapies, offering the potential to personalize treatment strategies based on individual molecular profiles. Classic biomarkers such as high-sensitivity troponins, NT-proBNP, and myoglobin, alongside emerging molecular and epigenetic markers, provide valuable insights into the mechanisms linking SARS-CoV-2 infection to myocardial injury, arrhythmia, and long-term cardiovascular sequelae. This review synthesizes current evidence on the molecular, genetic, and epigenetic underpinnings of COVID-19-related cardiovascular disease, highlighting the promise of precision medicine approaches for early diagnosis, prognostication, and targeted intervention in post-COVID-19 cardiovascular risk management.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Cardiovascular disease, Myocardial injury, Endothelial dysfunction, Cytokine storm, ACE2 receptor, Epigenetic reprogramming, Multiomics integration, Biomarkers

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55425 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of COVID-19 has revealed a spectrum of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), collectively termed COVID-19-associated acute cardiovascular syndromes (CVS). Complications such as myocardial injury, Arrhythmias, and heart failure are prevalent, With studies reporting acute myocardial injury in approximately 31% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

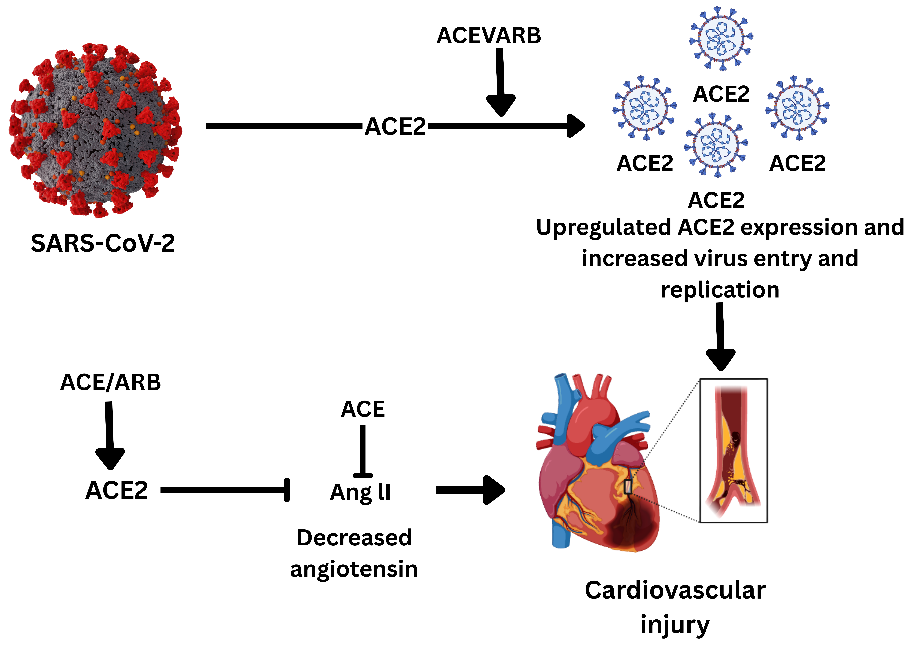

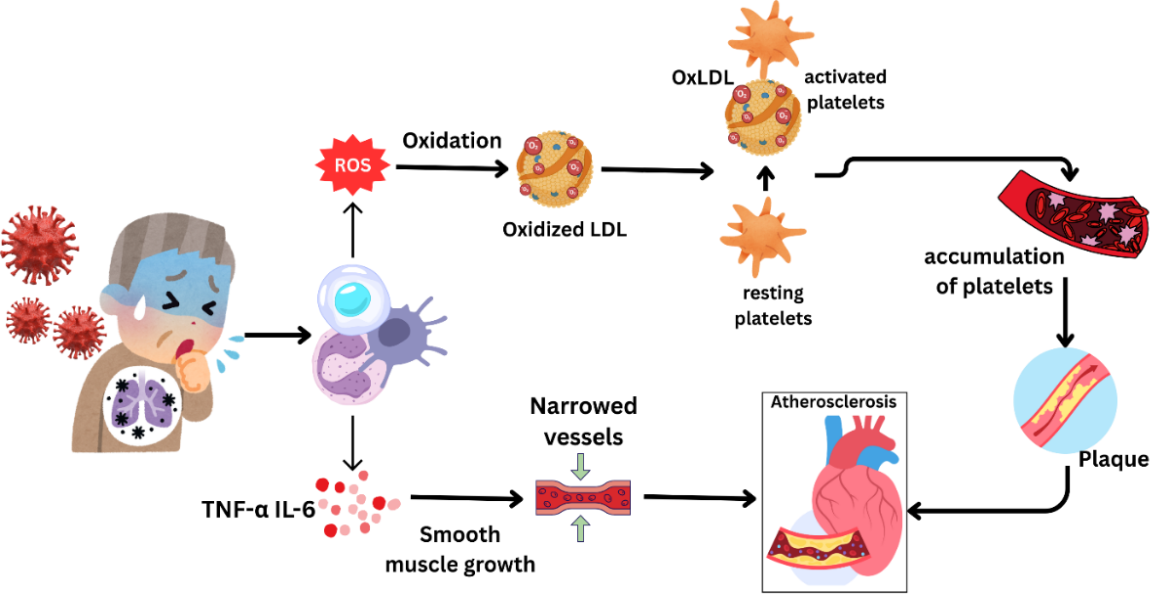

This is typically defined by elevated serum cardiac troponins and is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. The mechanisms involved are multifaceted and include both direct and indirect nerve pathways. The affinity of SARS-CoV-2 for the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor facilitates the viral invasion of cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells, primarily toward myocardial inflammation and endotheliitis [1]. The presence of a polybasic cleavage site at the S1/S2 boundary of the spike protein, which is missing in closely related coronaviruses, is a distinctive feature of SARS-CoV-2 [2]. SARS-CoV-2 binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is expressed on cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells, allowing viral entry and leading to myocardial inflammation and endotheliitis (1). A key feature of SARS-CoV-2 is the polybasic cleavage site at the S1/S2 boundary of the spike protein, absent in closely related coronaviruses, which facilitates viral entry. The host protease furin also plays a critical role by enhancing viral entry into host cells and contributing to the virus's broad tissue tropism. Fig. 1 illustrates the molecular mechanisms linking SARS-CoV-2 infection to cardiovascular complications, emphasizing viral entry via ACE2, activation of the immune response (cytokine storm), and endothelial dysfunction.

SARS-CoV-2 infection causes myocardial injury through a combination of direct viral toxicity and systemic immune responses. Infection triggers a cytokine storm, marked by elevated levels of interleukins (e. g., IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which exacerbate myocardial inflammation and contribute to cardiac dysfunction [3]. Additionally, severe respiratory involvement in COVID-19 may lead to hypoxemia, increasing myocardial stress and potentially causing ischemia. The prothrombotic effect of SARS-CoV-2 increases the risk of microvascular thrombosis, further compromising coronary circulation and leading to myocardial infarction [4].

A critical aspect of SARS-CoV-2’s pathophysiology involves ACE2 downregulation, which disrupts the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). This imbalance contributes to vasoconstriction, inflammation, and myocardial damage-a process that is exacerbated by direct viral binding to ACE2 and subsequent receptor internalization. In addition to the immune response, endothelial dysfunction plays a pivotal role in the development of COVID-19-associated cardiovascular complications. Studies, such as Varga et al. (2020), have demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 induces endothelial cell damage, leading to vascular inflammation and increased risk of thrombosis, which is integral to the severity of the disease [5]. SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to widespread endothelial inflammation, which plays a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of COVID-19. The viral nucleocapsid protein activates endothelial cells via Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), triggering NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, which result in upregulation of adhesion molecules and inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β [6]. Endothelial activation, along with the cytokine storm, promotes vascular dysfunction and exacerbates the systemic inflammatory response. Moreover, despite prophylactic measures, the procoagulant nature of COVID-19 has led to increased venous thromboembolism (VTE), highlighting the importance of immune-mediated coagulopathy in the severity of COVID-19 [7]. These results confirm the key role of endothelial dysfunction and immune-mediated coagulopathy in the progression and severity of COVID-19.

SARS-CoV-2's ability to infect cardiac endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes triggers myocardial injury, leading to inflammation and cell destruction. The cytokine storm exacerbates myocardial injury by causing hypoxemia, increasing myocardial oxygen demand, and facilitating the formation of microthrombi. These mechanisms increase the risk of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in COVID-19 patients. Emerging data also suggest that genetic predispositions may drive COVID-19-related cardiac events. For instance, the p. Ser1103Tyr-SCN5A polymorphism, prevalent in African American populations, has been linked to an increased risk of arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in the context of COVID-19 [8].

In cardiovascular diseases, endothelial cells release extracellular vesicles (EVs), including microvesicles and exosomes, in response to physiological stress or injury [9]. These vesicles carry bioactive molecules such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (e. g., mRNA, microRNAs, and noncoding RNAs), which facilitate intercellular communication and influence various pathophysiological processes [10]. Exosomes, in particular, transport heritable materials from damaged or apoptotic cells, offering a non-invasive method for detecting cellular changes without requiring a tissue biopsy. The liquid biopsy principle, which analyzes circulatory biomarkers, is increasingly utilized for early diagnosis and risk stratification in cardiovascular disease [11].

This review aims to explore how host genetic and epigenetic factors influence the spectrum and severity of cardiovascular sequelae following COVID-19 infection. By integrating multi-omics data-including miRNA expression profiles, exosomal biomarkers, and host genetic polymorphisms—we seek to identify predictive markers and therapeutic targets for precision medicine approaches. Specifically, we will examine how multiomics integration can inform personalized treatment strategies for post-COVID cardiovascular disease, thus advancing precision medicine in clinical management and intervention.

Fig. 1: Schematic representation of the impact of ACE inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) on SARS-CoV-2 infection and cardiovascular injury. SARS-CoV-2 uses the ACE2 receptor for cellular entry, and the use of ACEi/ARB drugs leads to upregulation of ACE2 expression, increasing viral entry and replication. This exacerbates cardiovascular injury by further promoting viral invasion and myocardial damage. In contrast, ACE inhibitors decrease angiotensin II levels, which may have protective effects against cardiovascular complications

Methods/approach

This review integrates evidence from peer-reviewed articles published between January 2020 and December 2024. Relevant literature was identified through structured searches of PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus using combinations of the keywords: "COVID-19," "SARS-CoV-2," "cardiovascular complications," "multiomics," "epigenetics," and "precision medicine." Only original research articles, meta-analyses, and reviews in English involving human subjects with accessible full texts were included. Non-human studies, case reports, and articles without full text were excluded. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, followed by full-text review. Data extraction focused on molecular mechanisms, biomarker discovery, and clinical relevance, emphasizing the integration of multiomics strategies in understanding COVID-19-associated cardiovascular pathophysiology.

Molecular and epigenetic biomarkers in post-COVID-19 cardiovascular risk assessment

The intersection of COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease (CVD) has unveiled a complex molecular landscape in which multiomics integration is revolutionizing the identification of biomarkers for risk stratification and therapeutic targeting. Emerging evidence highlights the significant role of epigenetic reprogramming in post-COVID-19 cardiac complications. For example, DNA methylation changes in genes such as Peg10 (hypomethylated) and Ece1 (hypermethylated) are related to altered cardiac function and inflammation, suggesting that epigenetic disturbances contribute to myocardial injury in COVID-19, as supported by studies demonstrating associations between DNA methylation changes and altered cardiac gene expression [12]. Given ACE2’s crucial role in regulating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and its involvement in maintaining cardiovascular and pulmonary homeostasis, the epigenetic repression of ACE2 by H3K27me3 can have far-reaching consequences. In COVID-19, where ACE2 expression is central to viral entry, excessive silencing of ACE2 could limit the body's ability to counteract viral infection, potentially exacerbating both pulmonary and cardiovascular dysfunction [13]. Interestingly, the dynamic regulation of H3K27me3—such as its removal by demethylases like JMJD3 (KDM6B) or UTX (KDM6A)—can reactivate previously silenced genes, including ACE2, under certain physiological or pathological conditions. This reactivation could play a role in recovering ACE2 expression in response to viral infections or cardiovascular stress. However, aberrant or excessive H3K27me3 at the ACE2 locus may contribute to disease states by limiting ACE2 expression, which is particularly relevant in the context of cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary disorders, and SARS-CoV-2 infection [14]. These findings underscore the potential of glycomic profiling to uncover novel biomarkers of cardiac damage.

Thus, the epigenetic regulation of ACE2 by H3K27me3 exemplifies the complex ways in which environmental stimuli, such as viral infections, can shape gene expression and influence disease outcomes. By understanding how these modifications regulate ACE2 and other critical genes, researchers may uncover new therapeutic strategies aimed at manipulating epigenetic marks to mitigate post-COVID-19 cardiovascular complications [15, 16] (table 1).

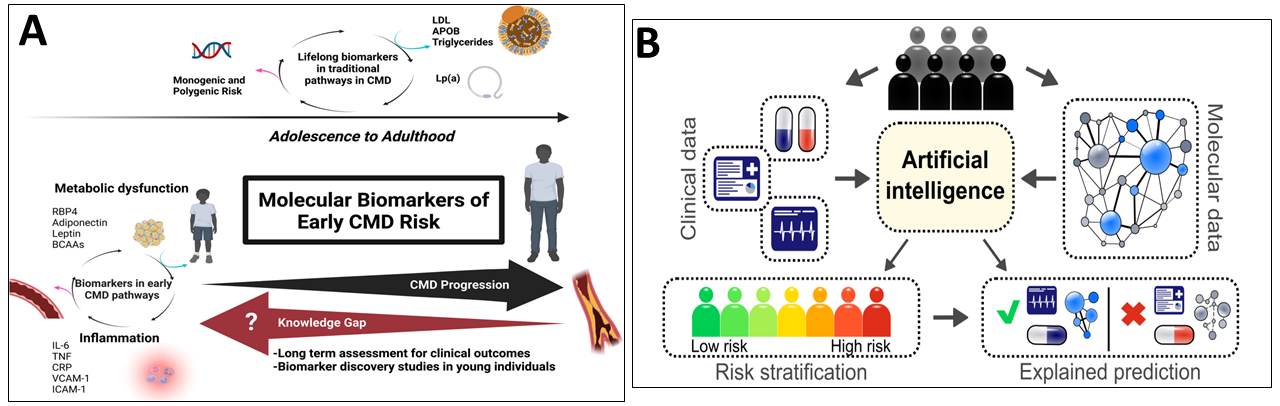

The integration of molecular and epigenetic biomarkers into post-COVID-19 cardiovascular risk assessment represents a breakthrough in precision medicine. Classic cardiac biomarkers, including high-sensitivity troponins (hs-cTnI, cTnT), NT-proBNP, myoglobin, and CK-MB, are consistently elevated in patients with COVID-19 who experience myocardial injury, and their levels strongly correlate with disease severity and mortality risk [17]. In particular, NT-proBNP and myoglobin have emerged as independent predictors of adverse events, particularly in noncardiac patients, highlighting the importance of nuanced biomarker interpretation in different clinical contexts. In particular, NT-proBNP and myoglobin have emerged as independent predictors of undesirable outcomes, particularly in noncardiac patients, highlighting the importance of nuanced biomarker interpretation in different clinical contexts [17]. The field is rapidly developing to include new molecular signatures, such as microRNAs (e. g., miR-155 and miR-21-5p). These molecular markers do not exclusively reflect the extent of cardiac and pulmonary involvement but nevertheless provide valuable mechanistic insights into the interactions among viral infection, inflammation, and tissue remodeling. These molecular fingerprints, together with epigenetic changes, including DNA methylation and histone acetylation patterns, guarantee Polish threat stratification, enable prior support, and demonstrate how targeted therapy in the postacute sequela of COVID-19 works. As multiomics integration becomes increasingly feasible, the convergence of proteomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic data is poised to accelerate our understanding of the complex molecular interactions between SARS-CoV-2 infection and long-term cardiovascular complications [18].

Table 1: Epigenetic regulators and their role in COVID-19 pathophysiology

| Epigenetic regulator | Target | Molecular mechanism | Pathophysiological role in COVID-19 | Clinical association | Ref |

| DNMT1 | TLR4 promoter | Hypermethylation | ↓ Innate immune response; impaired viral sensing | Severe COVID-19; cytokine dysregulation | [19] |

| TNF-α promoter | Hypermethylation | ↓ TNF-α expression; dysregulated inflammation | Higher risk of ARDS and multiorgan failure | [19, 20] | |

| ACE2 | ACE2 gene | Hypomethylation | ↑ ACE2 expression; enhanced viral entry | Increased susceptibility to infection | [21] |

| HDAC3 | Pro-inflammatory genes (e. g., IL6, CXCL1) | Histone deacetylation | ↑ Pro-inflammatory cytokine storm | Severe lung injury and hyper inflammation | [21, 22] |

| IFN-γ pathway | Deacetylation of H3K27 | ↓ Antiviral interferon response | Delayed viral clearance; prolonged infection | [23] | |

| SIRT1/NF-κB axis | NF-κB pathway | Competitive inhibition | ↑ Oxidative stress and endothelial damage | Thrombotic complications | [24] |

Mechanisms of viral-induced cardiovascular damage

The cardiovascular complications observed in COVID-19 patients are driven by a multifaceted interplay between direct viral injury, immune-mediated inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. The cytokine storm is triggered by excessive release of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6, which increase systemic and cardiac inflammation. Elevated cytokine levels induce endothelial activation, increase vascular permeability, and promote a hypercoagulable state, leading to microvascular dysfunction and the formation of microthrombi within coronary vessels [25]. This cascade disrupts coronary circulation and disrupts the transport of nutrients and oxygen to the heart muscle, thereby contributing to myocardial injury, cardiac arrhythmia, and cardiac incapacity [26].

In SARS-CoV-2-induced cardiac cell infection, both ACE2 and transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2) are expressed on cardiomyocytes and pericytes, facilitating viral entry into these cells. The virus binds to ACE2 on the cell surface, and TMPRSS2 cleaves the viral spike protein, enabling membrane fusion and viral entry. This direct infection leads to cytopathic effects, including cell death and impaired contractility in cardiomyocytes, and can trigger local myocardial inflammation. Additionally, infected cardiomyocytes secrete chemokines such as CCL2, which recruit monocytes and amplify inflammatory responses, further promoting myocardial injury and fibrosis. Pericyte infection via ACE2-dependent pathways also contributes to vascular dysfunction and inflammation within the heart. Collectively, these mechanisms exacerbate myocardial damage through direct cytopathic effects and by driving local and systemic inflammatory processes. Moreover, TNF-α and IL-6 have been shown to directly impair cardiac contractility and promote fibrosis, whereas IL-1 can accelerate fibrotic changes in cardiac tissue. The resulting endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and immune cell infiltration collectively drive the acute and chronic cardiovascular sequelae observed in COVID-19 patients [26].

Fig. 3 shows a multistep coronavirus infection method that can be used to avoid cardiovascular damage. After infection, SARS-CoV-2 causes renin‒angiotensin‒aldosterone (RAAS) organization dysfunction, which contributes to inflammation and oxidative stress, especially in the kidney, and initiates endothelial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species (ROS). The above modifications contribute to the formation of plaques in the coronary artery. Moreover, the overreaction of the immune system causes a cytokine storm, which further exacerbates cardiovascular stress. The risk of CVD is exacerbated by the combined effects of hypoxia and the imbalance between oxygen supply and demand.

Cytokine storm and endothelial dysfunction

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought renewed attention to the role of cytokine storms in pathophysiology. SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers a systemic inflammatory reaction, culminating in a cytokine storm corresponding to IL-6, IL-1, and IL-12. This reaction is associated with imperative injury to and dysfunction of endothelial tissues, as demonstrated by a reduction in the azotic oxide content, increased oxidative stress, and increased vascular permeability [27]. The resulting endothelial dysfunction significantly contributes to severe complications, including thrombosis and multiorgan failure. This underscores the critical importance of the tissue microenvironment in modulating these pathological processes and highlights the potential of targeting neurovascular pathways as part of therapeutic strategies.

The endothelium, which lines blood vessels, plays a focal role in vascular homeostasis by regulating vasodilation, thrombosis, and inflammation [21]. During a cytokine storm, inflammatory mediators disrupt endothelial integrity, leading to endothelial dysfunction and endotheliitis [28]. Proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, weaken the interendothelial junction by downregulating the important proteins VE-cadherin and ZO-1, increasing vascular permeability, and facilitating the infiltration of immune cells and cytokines into surrounding tissues. This method increases regional inflammation and vascular damage, which is further exacerbated by oxidative stress and the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [29].

Endothelial dysfunction is exacerbated by adjusting to a prothrombotic state, as cytokines disrupt the chain of curdling and suppress anticoagulant functions, including the downregulation of thrombomodulin and tissue factor nerve pathway inhibitors. Platelet activation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation (NETs) are more advanced microvascular thromboses, primarily toward ischemic injury in several organs, including the heart. The promotion of D-dimer and fibrin depletion products in COVID-19 patients isa clinical sign of the current hypercoagulable declaration and is closely associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and other thrombotic complications [29].

These findings further indicate that COVID-19 is associated with preexisting inflammatory conditions, particularly in elderly patients, where chronic inflammation exacerbates endothelial dysfunction [30]. Mechanically, SARS-CoV-2 can directly infect endothelial cells via ACE2, a major factor involved in cell death during inflammasome activation (e. g., NLRP and caspase-1), and mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to extrainvasive endothelial injury and inflammatory gene expression. The interaction between cytokine release and endothelial dysfunction may also extend to the basic nervous system, resulting in blood vessel obstruction and facilitating nervous system manifestations. Together, these mechanisms establish endothelial dysfunction as a key driver of COVID-19 disease and its cardiovascular and multiorgan complications [29].

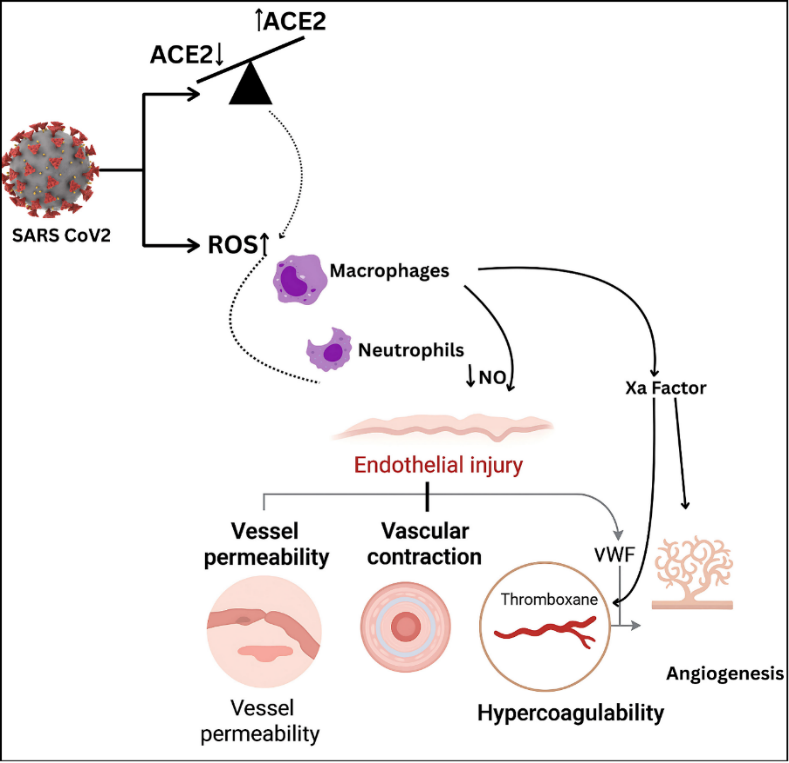

Fig. 2 shows the molecular pathways leading to endothelial dysfunction caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. The virus downregulates ACE2 and increases ROS production, promoting macrophage and neutrophil recruitment without depletion or thromboxane-mediated hypercoagulability. In addition, von Willebrand factor (VWF), whose main role is platelet collection, pathological angiogenesis, and endothelial damage, is upregulated. Moreover, factor Xa activation causes IL-6 expression and, in addition to inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, which is a major driver of COVID-19-related vascular and multiorgan complications.

Fig. 2: Pathophysiological effects of SARS-CoV-2 on endothelial function: The virus induces ROS production and ACE/ACE2 imbalance, promoting macrophage and neutrophil recruitment, NO depletion, endothelial injury, hypercoagulability via thromboxane and VWF, and subsequent platelet activation. Factor Xa contributes to IL-6-driven inflammation and pathological angiogenesis, leading to thrombotic complications in patients with COVID-19

Oxidative stress and cardiovascular damage

Oxidative stress occurs when reactive oxygen species (ROS) production exceeds the capacity of the antioxidant defense system, primarily in relation to cell and molecular perturbations, which are the cause of cardiovascular disorders. Proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, stimulate immune cells, including macrophages and neutrophils, to produce excessive ROS [31]. The current increase in production overwhelms the endogenous antioxidant, resulting in an oxidative state affecting the bioavailability of azotic oxide (NO). The decrease in NO disrupts normal vasodilation, stimulates vasoconstriction, and increases vascular resistance, which contributes to increased blood pressure and decreased coronary perfusion [32].

ROS cause direct damage to endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes by inducing lipid peroxidation, DNA atomization, and protein alteration, which may disrupt the apoptotic and necrotic nerve pathways, further deteriorating tissues and disrupting cardiac function [33]. Moreover, oxidative stress triggers redox-sensitive transcriptional components such as NF-B, which maintains a vicious cycle of inflammation and tissue damage. The interaction between oxidative stress and inflammation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of various CVDs, including myocardial infarction, heart failure, and atherosclerosis [34].

Cytokine effects on myocardial tissue

Inflammatory responses and cytokine release are essential for tissue repair after myocardial infarction (MI) but may also lead to undesirable cardiac adaptations and dysfunction. In response to myocardial injury, cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) are immediately increased, affecting both cardiac contractility and organizational adaptation [35]. TN-and IL-6 can directly impair left ventricular function by altering sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium metabolism, particularly by decreasing systolic cytosolic calcium and impairing myocyte contractility, which can be reversed by cytokine withdrawal. In addition to reducing myofilament sensitivity to calcium via an azotic oxide (NO)-dependent mechanism, TNF-α can cause negative inotropic effects via the impersonal sphingomyelinase nerve pathway, which disrupts calcium release and L-type calcium channel function [36].

An increase in cytokine signals, particularly TNF-α, triggers the apoptotic nerve pathway in cardiomyocytes, as demonstrated by increased caspase activity and altered expression of the apoptosis regulators Bcl-2 and Bax. The progressive loss of cardiomyocytes and deterioration of cardiac function are key consequences of sustained inflammation in the heart. Experimental models have demonstrated that overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) leads to cardiac hypertrophy, ventricular dilation, and ultimately heart failure. Additionally, late after MI, cytokine-induced iNOS expression elevates NO production, further desensitizing myofilaments to calcium and perpetuating contractile dysfunction [36].

In clinical settings, the ability to reliably predict adverse effects and mortality is crucial after myocardial infarction (MI) and in diseases like COVID-19, where cardiac complications frequently occur. For example, NT-proBNP levels exceeding 650 pg/ml have been demonstrated to predict mortality in severe COVID-19 pneumonia patients, and a persistent increase in these biomarkers is associated with a worse prognosis and increased risk of central failure [37, 38]. The Framingham Love Exam and other clinical tests confirmed that higher baseline levels of cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, are associated with a greater incidence of heart failure and cardiac events [36].

The attempt to therapeutically target cytokines, similar to the use of a TN inhibitor, does not produce the expected benefits in chronic spirit failure but underlines the complexity and pleiotropy of the cytokine signal. However, established treatments for post-MI, including ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers, have advantages via anti-inflammatory mechanisms, suggesting that the transitio Ask 8 inflammatory response residue is a key element in capable cardiac remodeling and recovery [36].

Fig. 3: Step-by-step progression of coronavirus infection leading to cardiovascular complications. After the virus enters the body, it disrupts the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), causing inflammation and oxidative stress, particularly in the kidneys. This sequence results in endothelial dysfunction and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which contribute to plaque buildup in the coronary arteries. Moreover, an excessive immune response triggers a cytokine storm, intensifying cardiovascular strain. The combination of low oxygen levels (hypoxia) and an imbalance between oxygen supply and demand further increases the risk of heart injury

Mechanisms leading to specific clinical outcomes

Heart failure

COVID-19 is closely associated with heart failure (HF) via two key approaches: as a precondition that worsens the effects of COVID-19 and as a side effect that may arise from the infection itself. Patients with current hypertension who have COVID-19 frequently experience additional severe symptoms, require more intensive care, and are at greater risk of in-hospital mortality than those who do not have hypertension [39, 40]. COVID-19 can directly precipitate new cases of heart failure (HF) through mechanisms similar to those seen in myocardial infarction, including myocardial inflammation, microthrombi formation, and stress cardiomyopathy. These outcomes may result from direct viral injury to cardiac tissue or from immune-mediated responses. Furthermore, individuals who survive COVID-19 are at increased risk of developing heart failure due to ongoing cardiac injury and persistent inflammation, even after apparent clinical recovery. This highlights the importance of long-term cardiovascular monitoring and management in COVID-19 survivors. The present bidirectional link highlights the need for careful monitoring and management of compassion fitness during and following COVID-19 infection [34].

Emerging evidence underscores a critical link between COVID-19 and heart failure (HF), both as a preexisting risk factor for severe outcomes and a potential complication of the disease. Research has revealed that approximately one-third of COVID-19 patients with anterior ventricular hypertension experience acute accent decompensation, whereas others develop new ventricular hypertension after infection. For example, in an Italian cohort, 9.1% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients experienced acute cardiac failure, with approximately half not having any prior cardiac dysfunction. Mortality rates also include the current risk. A Spanish study reported that 46.8% of COVID-19 patients with heart failure (HF) died, compared with 19.7% of those who did not have HF, highlighting the significantly increased mortality risk associated with pre-existing heart failure in the context of COVID-19 infection [41].

The long-term cardiac sequelae of COVID-19, similar to persistent myocardial injury and fibrotic modifications, suggest that HF likely develops chronically in survivors [42]. Advancing imaging methods, including echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance, which confirm systematic abnormalities and decreased cardiac function a calendar month after recovery, highlight the need for continued cardiovascular surveillance. To reduce the burden of post-COVID-19 HF by ensuring timely treatment of at-risk patients, preemptive monitoring and early involvement are essential [43].

Myocardial infarction and COVID-19-related myocarditis

COVID-19-associated myocardial injury is caused by direct virus-mediated cytopathy, endothelial dysfunction, and the resulting immune-mediated inflammation, leading to myocarditis and myocardial infarction. SARS‐CoV‐2 gains cellular entry by utilizing the angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is abundantly expressed in cardiac myocytes and endothelial cells and is proteolytically activated by TMPRSS2 [44]. Indeed, cardiac pericytes, which express high levels of ACE2, have been identified as key permissive initial targets in microvascular instability and local ischemia [45]. Viral replication within host cells leads to myocardial apoptosis, cytoskeletal distortion, and impaired contractility after entry into host cells [5]. Concurrently, endothelial invasion disrupts vascular integrity, triggering the release of von Willebrand factor, complement activation (notably C5b-9 deposition), and the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. They propagate a prothrombotic milieu of coronary vessels, which may arise as microthrombi or occlusive thrombosis [46]. Novel clinical findings from autopsies and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic COVID-19 survivors, with the benefit of autopsies and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), demonstrate that these patients have subclinical myocardial inflammation but are predisposed to long-term cardiac sequelae such as heart failure or arrhythmogenic events [47]. In addition, the 'cytokine storm' increases IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β levels, which potentiate myocardial injury through direct cytotoxicity and increased systemic endothelial activation [48]. Among the cytokines, IL-6 specifically magnifies leukocyte trafficking to cardiac tissue and increases endothelial cell expression of adhesion molecules, contributing to increased tissue infiltration and necrosis [49]. In severe examples, the current inflammatory cycle coincides with stress cardiomyopathy, where excess catecholamine synergizes with cytokine-mediated damage and further disrupts cardiac output. Together, these mechanisms highlight the unique cardiopathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 and the need to monitor cardiovascular function for a long period of time following infection, particularly in undesirable individuals [50].

Thromboembolism

COVID-19 thromboembolism occurs as a result of multifactorial viral invasion of the endothelium, endothelial impairment, immune-mediated inflammation and coagulopathy. SARS-CoV-2 enters target cells via the ACE2 receptor, which results in the downregulation and increased activity of angiotensin II [51]. It results in an imbalance of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) that increases vasoconstriction, inflammation, and the prothrombotic state. Severe cases of COVID-19 present with endothelial injury evidenced by perivascular T cells and widespread pulmonary vessel thrombosis. Alveolar capillary microthrombi are much more common in COVID-19 patients than in severely ill influenza patients, suggesting that a potent prothrombotic agent is the virus [52].

Increased release of von Willebrand factor, platelet activation, increased soluble P selectin, soluble CD40L and factor VIII lead to a hypercoagulable state in COVID-19 bedside endothelopathy. These markers are associated with mortality in intensive care unit (ICU) settings, even in noncritically ill patients, and are associated with elevated vWF levels, suggesting systemic coagulopathy. In addition, microvascular thrombosis is further worsened by the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), resulting in ischemic injury in other organs, such as the heart [53]. Furthermore, recent studies have shown the presence of fibrinoid microclots in the microcirculation, which are resistant to fibrinolysis and might play a role in long-term complications such as long COVID-19. Recent studies have also revealed the presence of fibrinoid microclots in the microcirculation, which are resistant to fibrinolysis and may contribute to long-term complications such as long COVID-19. These microclots can obstruct capillary blood flow, leading to tissue hypoxia and organ dysfunction [54].

Prolonged anticoagulation beyond the acute phase of COVID-19 has been shown to reduce the risk of VTE therapeutically [55]. In a study reported at the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Congress in 2024, patients who continued anticoagulation post-COVID-19 had no cases of VTE, whereas those who did not receive anticoagulation, or had it discontinued, had a higher incidence of thrombotic events [56]. These finding stresses that postacute thrombotic risks are indeed high and that extended prophylaxis is necessary for adequate prophylaxis. Furthermore, machine learning models have been developed to predict the occurrence of pulmonary embolism and mortality in COVID-19 patients at admission to help in early risk stratification and management of the disease [57].

Arrhythmias

We have increasingly recognized the association of COVID-19 with a spectrum of cardiac arrhythmias involving both the atrial and ventricular conduction systems. The most frequent arrhythmia found in hospitalized patients is sinus tachycardia, with rates ranging from 24.4% to 64.8% [58]. Fibrillation (AF) is noted in 10.5%-16.5% of cases, with a higher percentage being critically ill or having preexisting cardiovascular disease; 37% of cases have new-onset AF [59]. Notably, the occurrence of AF in COVID-19 patients is linked to increase in-hospital mortality, with some studies indicating a mortality rate of 45.2% in patients with new-onset AF compared with 11.9% in those without.

Although less common, ventricular arrhythmias also offer considerable clinical concern. A meta-analysis of 13,790 patients revealed a pooled prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias of 5% and a higher prevalence in patients with elevated cardiac troponin, suggesting an association with myocardial injury [60]. Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation are associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with preexisting cardiac disease.

The pathophysiology of these arrhythmias in COVID-19 patients is multifactorial. Myocardial tissue in myocarditis can be directly invaded by a virus through ACE2 receptors, and systemic inflammation and cytokine storms can lead to electrical instability. Hypoxia, electrolyte imbalances and the use of QT-prolonging medications all add to arrhythmogenesis [61]. Emerging evidence also points to autonomic dysfunction as a contributing factor, with studies indicating that SARS-CoV-2 may disrupt autonomic regulation, leading to arrhythmic events [62].

In light of these findings, continuous cardiac monitoring and early identification of arrhythmic events are crucial in the management of COVID-19 patients, especially those with preexisting cardiovascular diseases or elevated inflammatory markers. Further research is warranted to elucidate the long-term cardiac implications of COVID-19 and to develop targeted strategies for arrhythmia prevention and treatment in this patient population.

Chronic viral infections and long-term risks

Emerging evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 infection can lead to lasting epigenetic modifications in host cells, contributing to the phenomenon termed "post-COVID-19 methylome memory." An example of one alteration lies in the repression of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) gene in endothelial cells via the trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3), a well-defined epigenetic silencing marker. This modification is mediated by polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which facilitates the addition of H3K27me3 marks, leading to chromatin condensation and transcriptional repression [63]. Downregulation of ACE2 disrupts the balance of the renin‒angiotensin system (RAS), leading to endothelial dysfunction, increased vascular permeability, and a proinflammatory state. Some of the persistent cardiovascular complications observed in long-term COVID-19 patients might be driven by these changes [64].

Moreover, the epigenetic silencing of ACE2 mediated by H3K27me3 might not be restricted to endothelial cells but might occur even in other cells expressing ACE2, as observed in other epithelial cells of the lungs and kidneys [65]. The multiorgan symptoms associated with long COVID-19 could also have contributed to these widespread repressions [66]. Therefore, revealing the mechanisms of this epigenetic regulation may enable therapeutic intervention. For example, one could reverse the repression of ACE2 and retrieve normal cellular function via the inhibition of the PRC2 complex or the use of demethylating agents. However, more research is needed to reveal the extent to which these epigenetic changes actually spread, as well as how they may affect survivors of COVID-19 worldwide.

Comparative virology: cardiovascular complications in other viral infections

While SARS-CoV-2 has intensified scientific focus on virus-induced cardiovascular damage, it is essential to understand that a wide range of other viral pathogens also contribute to useful cardiac complications via equally share and distinct mechanisms. For instance, influenza virus infection has long been associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction, myocarditis, and psychological or emotional distress. Systemic inflammation, endothelial activation, and prothrombotic conditions are frequently responsible for these episodes. Various investigations have shown an increased incidence of Acute Coronary Syndrome and Cardiac Arrhythmia during the influenza outbreak, particularly in susceptible communities with preexisting medical conditions [67].

In contrast, SARS-CoV-2 has a wide range of cardiovascular effects due to its unique use of the ACE2 receptor, which is expressed widely in the central nervous system, the vasculature, the renal, and the lungs. The present wide tissue tropism, together with the presence of a polybasic cleavage site in its own spike protein, enhances its ability to penetrate different organs. Consequently, patients with COVID-19 frequently experience myocardial inflammation, microvascular thrombosis, cardiac arrhythmia, and central failure even when they do not have severe respiratory symptoms [68, 69]. As shown in table 1, SARS-CoV-2 differs significantly from earlier coronaviruses like SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, which demonstrated less frequent and less severe cardiovascular involvement [70, 71].

The alternative cardiotropic viruses, also known as Coxsackievirus B, are well established causes of myocardial inflammation due to their ability to attack directly the cardiomyocytes. The present virus uses the coxsackie-adenovirus receptor (CAR) and causes inflammation, necrosis, and the potential development of dilatation of the heart [72]. However, as noted in table 2, it typically does not have the thrombotic and systemic endothelial complications that qualify SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, viruses such as Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) may have long-term cardiovascular effects through chronic immune activation and vascular inflammation. CMV is associated with coronary artery disease, HIV with cardiomyopathy and pneumonic hypertension, and EBV with myocarditis and vasculitis [73].

Table 2: Comparative virology: cardiovascular complications across viral infections

| Virus | Receptor usage | Key cardiovascular complications | Mechanisms involved | Unique features/Notes | Clinical management implications | Ref |

| SARS-CoV-2 | ACE2 | Myocarditis, myocardial injury, arrhythmias, heart failure, thromboembolism | Direct cardiomyocyte invasion, endothelial dysfunction, cytokine storm, thrombosis, oxidative stress | Polybasic cleavage site increases infectivity; broader tissue tropism; high thrombotic burden (Cenko et al., 2021), | Monitor cardiac biomarkers and ECG; echocardiography; anticoagulation; immunomodulatory therapies; manage arrhythmias and myocarditis. | [69, 74] |

| Influenza virus | Sialic acid | Myocarditis, myocardial infarction, heart failure, arrhythmias | Systemic inflammation, endothelial activation, thrombosis, direct myocardial invasion | - | Early antiviral treatment (e. g., oseltamivir); influenza vaccination; cardiac monitoring; manage as per myocarditis/ACS. | [67, 75] |

| SARS-CoV (2002) | ACE2 | Myocardial inflammation, arrhythmias, mild myocarditis | Cytokine-mediated inflammation, mild endothelial involvement | Less severe CV impact than SARS-CoV-2 | Supportive care; monitor for cardiac involvement; manage arrhythmias and inflammation. | [71] |

| MERS-CoV | DPP4 | Myocarditis, heart failure (rare) | Immune-mediated injury, limited cardiac tropism | Lower incidence/severity of CV issues | Focus on respiratory support; cardiac monitoring if symptoms present; echocardiography if indicated. | [70] |

| Coxsackievirus B | CAR | Viral myocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy | Direct myocyte lysis, chemokine-driven inflammation | - | Supportive care for myocarditis (rest, heart failure meds); consider immunosuppression in severe cases; long-term management of cardiomyopathy. | [76] |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) | β2 integrins (e. g., CD13) | Myocarditis, coronary artery disease, transplant vasculopathy | Chronic vascular inflammation, endothelial damage, immune dysregulation | - | Antiviral therapy (ganciclovir/valganciclovir) for active infection; in transplant patients, prophylaxis; manage cardiovascular risk. | [73] |

| HIV | CD4, CCR5, CXCR4 | Cardiomyopathy, pericarditis, atherosclerosis, pulmonary hypertension | Chronic inflammation, immune activation, ART-related cardiotoxicity | - | Early ART; monitor for ART cardiotoxicity; aggressive management of traditional CV risk factors; treat pericarditis and cardiomyopathy. | [73] |

| Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) | CD21 | Myocarditis, pericarditis, coronary vasculitis | B-cell-mediated immune response, vasculitis, systemic inflammation | - | Supportive care for myocarditis/pericarditis (NSAIDs, colchicine); consider antivirals in severe cases; immunosuppression for vasculitis. | [73] |

Genetic architecture of COVID-19 cardiotoxicity

The genetic framework that supports COVID-19 cardiotoxicity is multifaceted and includes both host heritable sensitivity and the inflammatory nerve pathway, which contributes to cardiovascular damage. The discrepancy in the ACE2 gene, which is essential for SARS-CoV-2 entry, has been linked to systemic inflammation and increased cardiovascular threat in COVID-19 patients, particularly SNPs such as rs4646142 and rs6632677, which correlate with biomarkers of cardiac stress and inflammation [77, 78]. In addition to ACE2, alternative polymorphisms such as IFITM3 (rs6598045), in addition to being associated with higher COVID-19 mortality rates, propose great ancestral strength in terms of disease outcomes [79]. Moreover, cytokine-induced inflammation, particularly IL-6 and TNF-α, has been demonstrated to directly impair cardiomyocyte function even in the absence of viruses, highlighting the way in which the immune response itself can cause cardiac injury (table 3) [80, 81].

Furthermore, extensive analysis revealed that COVID-19 severity and cardiotoxicity are influenced by shared inherited nerve pathways that affect immune responses, curdling, and endothelial function. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and phenome-wide association studies (PheWASs) clearly overlap, despite severe COVID-19 results and other cardiovascular and inflammatory conditions. For example, differences close to the ABO gene locu are associated with COVID-19 badness and increased thrombotic liability because ACE and ACE2 polymorphisms affect host susceptibilities and inflammatory responses [82, 83]. Importantly, genes that regulate the immune nerve pathway, similar to the Toll-like receptor and cytokine signaling components (e. g., IL6 and TNF-α), are involved in the development of hyperinflammatory conditions that significantly contribute to myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19 [84, 85].

Table 3: Recent studies on the genetic architecture of COVID-19-related cardiotoxicity

| Study | Key findings | Genetic loci/Genes | Implications | Ref |

| Ferreira et al. (2022) | Identified COVID-19 GWAS loci overlapping with cardiovascular pathways | LZTFL1, ABO, ACE2, IFNAR2, DPP9 | Implicated in vascular injury, inflammation, and immune dysregulation | [86] |

| Verma et al. (2021) | COVID-19 risk loci (ABO, TYK2) also associated with cardiovascular traits | ABO, TYK2 | Shared genetic basis with thrombosis and heart failure | [82] |

| Gholami et al. (2022) | Haplotypic variants linked to blood pressure and metabolites | ACE, AGT (rs4316, rs5051) | Regulatory variants affect vascular/ metabolic traits linked to COVID-19 severity | [87] |

| Upadhyai et al. (2022) | Identified rare variants in cardiac structure genes linked to COVID-19 severity | SPEG, DES, FBXO34 | These genes underlie susceptibility to cardiac injury in COVID-19 | [88] |

| Horowitz et al. (2022) | Variant lowering ACE2 expression reduces COVID-19 risk | rs190509934 (ACE2) | Protective against infection but may impair cardiac regulation | [89] |

| Loktionov et al. (2024) | Identified COVID-19 GWAS SNPs that increase risk of CAD and stroke | SLC6A20-LZTFL1, DPP9, ELF5 | Variants contribute to inflammation, oxidative stress, and thrombosis | [90] |

| Hu et al. (2021) | Found 8 genetic “supervariants” linked to COVID-19 mortality | DES, SPEG, DNAH7, STXBP5 | Involve cardiac function, thrombosis, and mitochondrial pathways | [91] |

| Li and Chen (2024) | COVID-19 causally increases risk for multiple CVDs (e. g., MI, HF) | Multiple GWAS loci (Mendelian randomization) | Confirms COVID-19 as a risk factor for heart failure, angina, MI | [92] |

In addition to ACE2 and inflammatory cytokines, a number of alternative genes have been identified as crucial participants in the ancestral sensitivity of COVID-19 patients to cardiovascular complications. Polymorphisms in the ACE gene (e. g., rs4343 and rs4341) (table 4) were associated with worse results in hypertensive or diabetic patients with COVID-19, suggesting an increased ramification of comorbidities and hereditary vulnerabilities [93]. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) gene and the Toll-like receptor (TLR) play important roles in the modulation of immune reaction, contributing to the cytokine surge, which damages the cardiovascular system [83, 85]. TYK2 and DPP4, which are involved in interferon signaling and viral entry, respectively, have also been linked to the modulation of immune dysfunction and cardiovascular complications [94].

Table 4: Key genes and their roles in COVID-19-related cardiotoxicity

| Gene/locus | Associated Variant(s) | Role in COVID-19 cardiotoxicity | Ref |

| ACE2 | rs4646142, rs6632677 | Viral entry receptor: polymorphisms linked to systemic inflammation and CV risk | [77] |

| ACE | rs4343, rs4341 | Associated with worse cardiac outcomes in comorbid COVID-19 patients | [93] |

| IFITM3 | rs6598045 | Polymorphism linked to increased COVID-19 mortality | [79] |

| ABO | rs505922 | Linked to thrombosis and severe COVID-19 outcomes | [82] |

| IL6, TNF-α | Not specified | Cytokines driving myocardial damage via hyperinflammatory response | [80] |

| TLR genes | Various | Regulate immune response, cytokine release, and inflammation severity | [82] |

| HLA locus | Various | Governs antigen presentation; variations influence immune response to virus | [83] |

| TYK2 | rs34536443 | Alters interferon and cytokine signaling; linked to autoimmunity and viral defense | [82] |

| DPP4 | Various | Facilitates viral entry; higher expression may worsen infection | [94] |

Shared genetic loci and correlations

Genome-wide cross-trait meta-analyses provide a solid understanding of the overlapping hereditary mechanism underlying joint disease. Individual scrutiny revealed that 10 patients had COVID-19 and coronary artery disease (CAD), 3 had type 2 diabetes (T2D), 5 had corpulence (OBE), and 21 had hypertension (HTN). These spaces were enriched in the signal and secretion nerve pathways, demonstrating that immune signaling, inflammation, and metabolic regulation may contribute to a common life-related mechanism associated with these disorders [95]. Moreover, Mendelian randomization analysis in this analysis suggested that COVID-19 may have a potential causal effect on CAD, OBE, and HTN, suggesting that the inherent sensitivity to severe COVID-19 may be similar to that of these chronic conditions.

Further large-scale investigations have corroborated and expanded upon these biological parallels. Notably, a comprehensive genome-wide cross-trait analysis of COVID-19 and obesity identified 13 risk loci through colocalization studies, in addition to implicating 3,546 pleiotropic genes. These genes are mainly active in the immune and cue transduction nerve pathways, confirming that the immune‒metabolic axis is a crucial convergence peak in the midst of COVID-19 malignity and metabolic irregularities in addition to fleshiness [96]. Moreover, hereditary research on the link between COVID-19 and hypertension has identified a significant positive heritable relationship and eight common protein-coding genes, such as ABO and FUT2, that regulate the inflammatory and vascular nerve pathways involved in joint disease [97]. These findings highlight the role of endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory signaling as shared mechanisms in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and cardiovascular diseases.

Recent studies have shown that COVID-19 and countless cardiac traits, notably coronary artery disease (CAD), type 2 diabetes (T2D), fleshiness (OBE), and hypertension (HTN), are intertwined in the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility and cardiovascular conditions.

A significant constructive hereditary correlation between COVID-19 and CAD (Rg = 0.4075, P = 0.0031), T2D (Rg = 0.232, P = 0.0043), fleshiness (Rg = 0.3451, P = 0.0061), and HTN (Rg = 0.233, P = 0.0026) was observed in a genome-wide cross-trait meta-analysis. These associations suggest that shared genetic loci affect both COVID-19 severity and cardiometabolic conditions. Specifically, 10 sites were shared between COVID-19 and CAD, 3 with T2D, 5 with OBE, and 21 with HTN, together with a number of sites involved in inflammatory and metabolic signaling pathways [95].

Complementary evidence from a Mendelian randomization study supports these findings, showing that genetic liability to T2D, CAD, and obesity is positively associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes [98]. Another large-scale GWAS, in addition to confirming that trait appreciation fleshiness, T2D, and HTN genetically converge with COVID-19, highlights the importance of metabolic and cardiovascular fitness for COVID-19 susceptibility and progression [99]. Moreover, none of the lipid traits identical to those of LDL, HDL, total cholesterol (TC), or, alternatively, triglycerides (TGs) have been found to have a useful ancestral association with COVID-19 during the aforementioned trait, suggesting that not all cardiometabolic traits share an inherited basis with COVID-19 consequences [95].

A 2024 analysis by Chen et al. conducted a large-scale genome-wide cross-trait evaluation, confirming a robust biological association between obesity and COVID-19. The study examined 331 shared single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and identified 13 common risk loci, with a particular enrichment in immune signaling and neural pathways. These findings further reinforce the role of obesity as a hereditary susceptibility factor for COVID-19 [96]. Another analysis by Singh et al. 2024, found host ancestral variations, especially in genes involved in metamorphosis, highlighted in this context: APOE, MTHFR, inflammation and curdling (e. g., IL-6, CRP, ACE2, PAI-1) to assist with COVID-19-induced cardiac damage. These findings support the assumption that a certain biological background predisposes humans to both CVD and COVID-19 complications [100].

In addition, a 2022 study using UK Biobank information revealed that polygenic risk scores (PRSs) for coronary artery disease (CAD), atrial fibrillation, and venous thromboembolism predict a higher incidence of these diseases following COVID-19. Importantly, lifestyle factors modify this ancestral threat, highlighting the interaction between genetics and the ecosystem in post-COVID-19 cardiovascular outcomes [101]. Loktionov et al. (2024) identified key genetic markers associated with specific COVID-19 GWAS-related SNPs, notably rs17713054 in the SLC6A20-LZTFL1 locus and rs12610495 in DPP9. These findings provide critical insights for addressing the shared genetic challenges underlying coronary artery disease and stroke. Moreover, they validate the overlap between the heritable genetic architectures of COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease [90].

Tissue-specific gene expression and pathways

Transcriptome-wide association studies (TWASs) have shown that a significant tissue-specific gene utterance form is correlated with COVID-19 and a number of cardiac contexts; however, the aforementioned associations do not directly coincide with each individual tissue [102]. These findings suggest that the expression and impact of COVID-19 and cardiac diseases may be influenced in a remarkably divergent manner by the state of the tissues during COVID-19. For example, spatiotemporal transcriptomic analysis of COVID-19-infected liver and lung tissues revealed a shared immune-related gene expression pattern, characterized by signatures associated with B-cell activation and complement pathway activation. Additionally, the analysis uncovered a unique response: preferential endothelial cell migration within the affected tissues, indicative of tissue-specific remodeling and a distinct damage response[103]. Similarly, the SARS-CoV-2 accessory protein ORF3a has been demonstrated to participate in distinct signaling cascades across lung, brain (including regions implicated in emotional regulation), and cardiac tissues. Notably, ORF3a is uniquely associated with the modulation of calcium ion transport, a neural pathway critically involved in cardiac contractility and arrhythmogenesis [104]. Additionally, pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the cMP-PKG signaling pathway is particularly important in this tissue-specific response. This nerve pathway, which is familiar with the regulation of vasodilation and cardiac contractility, has emerged as a focal mechanism possibly involving COVID-19-induced endothelial dysfunction and cardiac complications [105]. Moreover, TWAS and bioinformatic analysis revealed systematic enrichment of the immune nerve pathway, including IL-6 and GPCR signals, in both pneumonic and cardiac tissues during SARS-CoV-2 infection, highlighting the systemic but organ-specific immune dysregulation at play [68].

In addition to tissue-specific gene expression, the integration of miRNA (miRNA) infrastructure analysis provides crucial insight into the mechanism driving organ-specific results in COVID-19. For example, in a survey of ORF3a viroporin interaction networks, a distinct group of miRNAs modulates gene expression in the lung and brain, although only a single essential miRNA target has been identified at the center, highlighting relatively restricted but highly specific regulatory regulation in cardiac tissue [104]. These findings are significant as they demonstrate that posttranscriptional gene regulation can influence disease severity and organ involvement, particularly in tissues such as the heart, which are otherwise less transcriptionally responsive to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Similar to miRNA-mediated regulatory differences, increased clinical awareness and patient-reported knowledge of cardiac symptoms or persistent cardiovascular complications in the absence of severe respiratory manifestations may help to elucidate this phenomenon.

Furthermore, differential pathway activity analysis revealed that while immune activation is widespread, downstream effects diverge by tissue. For example, the interleukin-6 (IL-6) signaling axis is markedly increased in patients with COVID-19-related myocardial injury and is associated with a useful decrease in lymphocyte counts, a hallmark of immune deregulation and poor prognosis [96]. Similarly, the cGMP‒PKG signaling pathway, which is familiar with the regulation of vasodilation and vascular remodeling, systematically changes the affected tissues and may constitute a common mechanical link during pneumonic and cardiac complications. These tissue-specific differences in nerve pathway interactions, immune responses, and transcriptional profiles substantiate the complexity of COVID-19 pathology and the relevance of targeted therapy to precise organ structures on the basis of a molecular signature. A summary of key genes, their functional roles, and associated diseases or processes is provided in table 5.

Table 5: Key genes, functional roles, and associated diseases/processes

| Gene | Functional role | Associated disease/Process | Ref |

| BRCA1 | DNA repair via homologous recombination | Hereditary breast/ovarian cancer | [106] |

| BRCA2 | DNA repair and genomic stability maintenance | Hereditary breast/ovarian cancer | [106] |

| TP53 | Tumor suppression, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis | Li-Fraumeni syndrome, various cancers | [107] |

| CFTR | Chloride ion transport in epithelial cells | Cystic fibrosis | [108] |

| EGFR | Cell proliferation and signaling regulation | Non-small cell lung cancer | [109] |

| APOE | Lipid metabolism and amyloid-beta clearance | Alzheimer’s disease | [110] |

Molecular mechanisms and cardiac injury

SARS-CoV-2 infection causes significant cardiac damage through several molecular mechanisms that disrupt the function of cardiomyocytes and increase inflammation. Mitochondrial disorders, where viral proteins such as the M protein are localized in mitochondria, alter their shape, and reduce oxidative phosphorylation, are part of the central nervous system [111]. Decreasing ATP production and increasing oxidative stress contribute to cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 infection disrupts the NF-B signaling nerve pathway, resulting in the development of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, which may increase myocardial inflammation and damage [112]. The virus also affects calcium homeostasis in cardiomyocytes. An increase in genes involved in calcium transport, such as STIM1 and L-type calcium channels, has been detected in the calcium signal nerve pathway. Arrhythmias and cardiac hypertrophy may result from these changes [111]. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 suppresses ACE2 signaling during host cell entry. ACE2 is a major regulator of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), and its downregulation aims at accreting angiotensin Il. This transition contributes to vasoconstriction, inflammation, and fibrosis, which contribute to cardiac stress and injury [113].

SARS-CoV-2 infection initiates a cascade of intracellular events that significantly disrupt the function of cardiomyocytes at the molecular level. Mitochondrial dysfunction is detected by an individual with earlier molecular derangement triggered by the interaction of viral proteins, such as ORF9b and membrane proteins, with the host mitochondria. This interaction disrupts mitochondrial interactions and biosynthesis, resulting in reduced oxidative phosphorylation, decreased ATP synthesis, and excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These bioenergetic perturbations are capable of causing cardiac stress and apoptosis, thus contributing to myocardial injury. A review by Shang et al. (2022) revealed that septic cardiomyocytes exhibit significant changes in mitochondrial morphology and metabolic reprogramming, highlighting the influence of viruses on cardiac energy metamorphosis [95].

The activation of the proinflammatory signaling nerve pathway, particularly the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-B) nerve pathway, is another key mechanism. SARS-CoV-2 stimulates toll-like receptors (TLRs) and intracellular form appreciation receptors (PRRs), which are mainly responsible for NF-κB activation and the subsequent transcription of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β. In a systemic cytokine storm, particularly in severe cases of COVID-19, this inflammation may increase, facilitating endothelial dysfunction, vascular escape, and cardiac ischemia. Recent transcriptomic analysis of cardiac tissue from a COVID-19 patient revealed increased expression of inflammatory mediators and immune cell infiltration [114].

In addition, calcium signal disturbance plays a key role in SARS-CoV-2-induced cardiac injury. The virus has been associated with an increase in phospholipase C gamma 2 (PLCG2), a gene involved in calcium mobilization from the intracellular space. Calcium imbalance leads to sarcoplasmic reticulum stress, contractile dysfunction, arrhythmia, and even cardiac hypertrophy. The increased susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmias and undesirable cardiac modifications, particularly under inflammatory stress conditions, have been correlated with the promotion of PLCG2 expression [115]. Additionally, calcium overload exacerbates mitochondrial permeability transition and amplifies cell death pathways, creating a vicious cycle of injury.

Finally, SARS-CoV-2 entry via the ACE2 receptor affects its downregulation, disrupting the renin‒angiotensin‒aldosterone system (RAAS). ACE2 is normally a regulator of angiotensin Il by converting it into angiotensin-1-7, a vasodilatory and antifibrotic molecule. Loss of ACE2 alters RAAS stability toward angiotensin Il accumulation, stimulating vasoconstriction, oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis. This imbalance contributes to increased blood pressure and to the development of undesirable cardiac adaptations [116, 117]. Together, these molecular alterations illustrate the multifaceted nature of cardiac injury in patients with COVID-19 and highlight potential therapeutic targets for cardiovascular protection.

Genetic susceptibility and polygenic risk

The polygenic architecture of COVID-19 suggests that common ancestral divergences offer simultaneous susceptibilities to infection and undesirable outcomes, including cardiac complications. Hereditary liability in cases such as ischemic stroke is significantly correlated with severe COVID-19, highlighting the importance of shared heritable threat variables in reducing cardiotoxicity [118].

Recent studies have illuminated the significant role of genetic susceptibility and polygenic risk in determining both the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the severity of COVID-19 outcomes, particularly concerning cardiac complications. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have examined specific biological sites, such as 3p21.31 and 9q34.2, associated with severe COVID-19. The SLC6A20, LZTFL1, and CXCR6 genes, which are involved in immune responses and possibly affect the severity of the illness, are present at 3p21.31. Similarly, where blood group A is associated with a greater risk of severe COVID-19, the 9 g34.2 venue corresponds to the ABO blood group, whereas blood group O appears to have few protective effects [119].

Polygenic liability tons (PRSs), which combine the effects of various hereditary discrepancies, have been a key element in measuring the susceptibility of individuals to COVID-19-related complications [120]. An analysis of data from the UK Biobank revealed that a higher PRS is correlated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events, including atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, venous thromboembolism, and ischemic stroke, after COVID-19 [101]. In particular, individuals with high ancestral risk exhibit a significantly greater hazard ratio for these conditions compared to those with low ancestral risk. Furthermore, genetic variations in genes related to metamorphosis, inflammation, and curdling nerve pathways have been implicated in the progression of COVID-19-related cardiac injury. Polymorphisms in the ACE2, TMPRSS2, and IL-6 genes are associated with increased susceptibility to serious diseases and increased mortality rates. For example, the T allele of rs12329760 in the TMPRSS2 gene and the confident IL-6 polymorphism have been correlated with severe COVID-19 outcomes, highlighting the complex interaction among the ancestral components and disease severity [100].

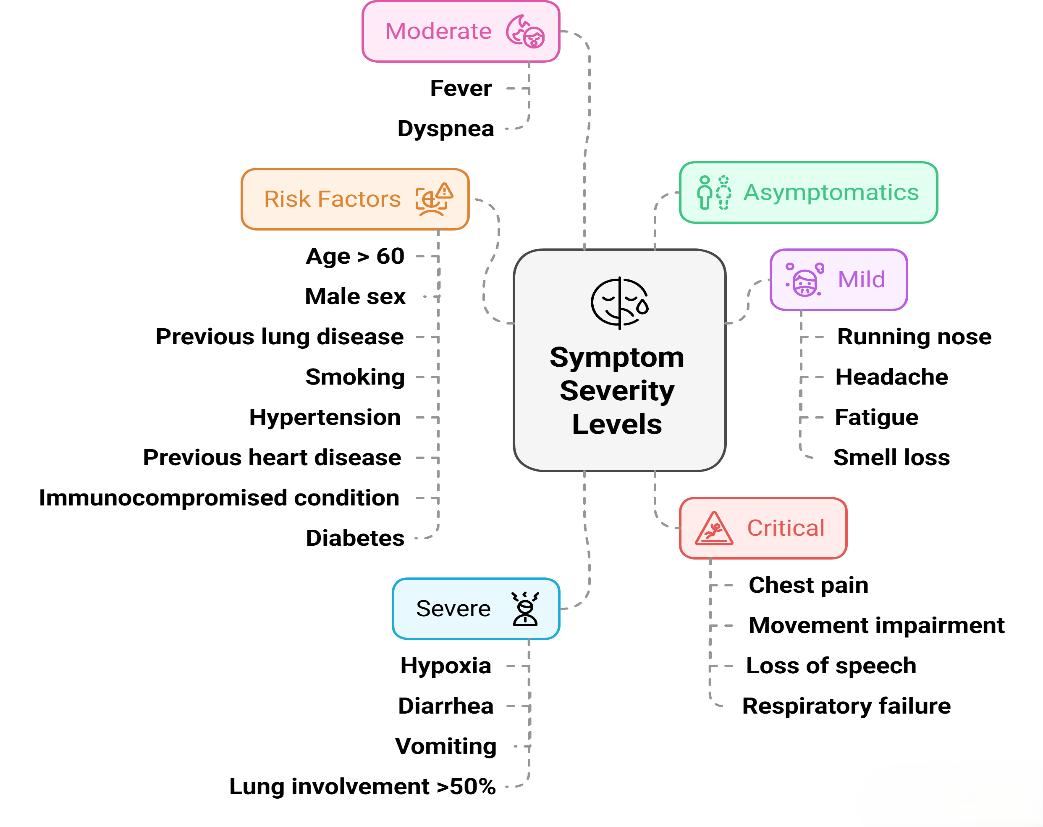

COVID-19 is now widely recognized as a systemic illness with a broad range of clinical outcomes, from no symptoms at all to life-threatening complications. Research shows that approximately one-third of infected individuals remain asymptomatic, whereas others can experience severe or even fatal outcomes [121–123]. Initial symptoms often mimic those of common respiratory infections such as flu or parainfluenza, typically including fever, coughing, and fatigue. Less frequent symptoms include headaches; sore throat; muscle and joint pain; digestive issues such as diarrhea or vomiting; and sensory changes such as loss of smell (anosmia) or taste (ageusia) (fig. 5) [124].

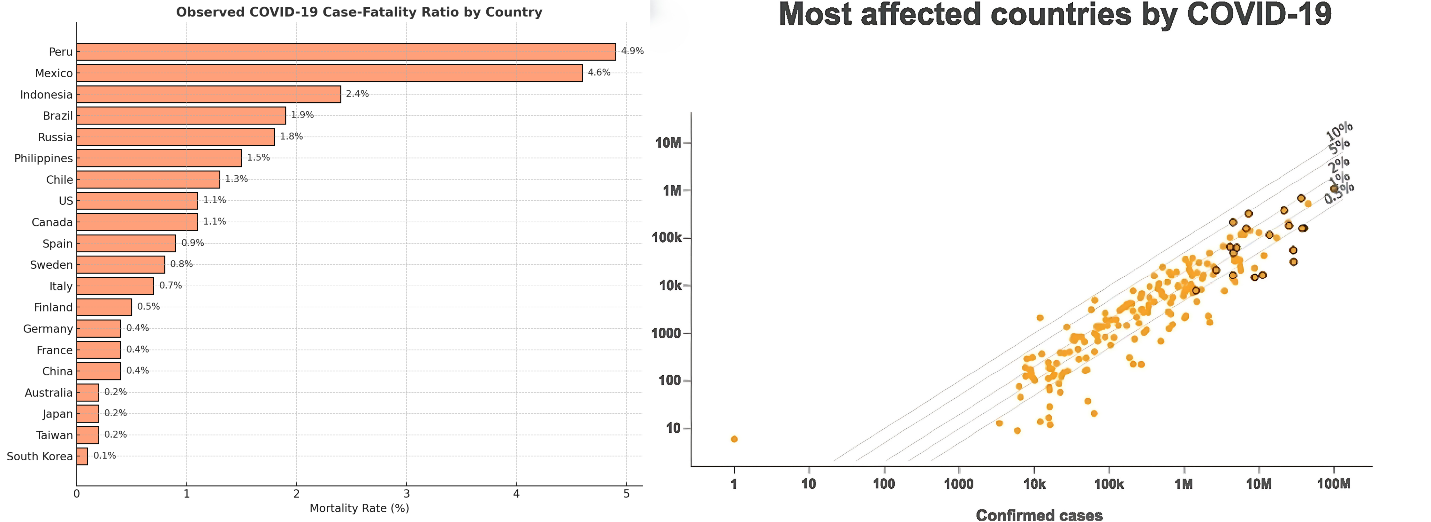

A large-scale study involving over 70,000 COVID-19 patients revealed that 81% exhibited mild to moderate symptoms, 14% developed severe illness requiring respiratory assistance, and approximately 5% experienced critical conditions such as respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiorgan dysfunction—leading to causes of COVID-19-related mortality [117]. Fatality rates vary widely across the world. For example, South Korea has reported a low death rate of 0.1%, whereas Peru has seen a much higher death rate of 4.9% on December 28, 2022 (Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Data). The key risk factors for developing severe or fatal COVID-19 complications include being over 65 years old, male sex, and preexisting conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, chronic diseases (pulmonary, renal, and hepatic), a weakened immune system, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and obesity [125, 126]. Moreover, an increasing number of individuals experience prolonged health issues beyond the acute phase of infection. Known as post-COVID-19 syndrome or long-term COVID-19, these symptoms can persist for more than three months after the initial illness (fig. 6) [127].

Fig. 5: SARS-CoV-2 infection can result in a range of clinical outcomes, ranging from no symptoms to severe or life-threatening illness. The fig. highlights common symptoms at each severity level, as well as key risk factors such as older age, male sex, and preexisting health conditions

Fig. 6: Country-level case fatality rates. The left panel lists the 20 countries with the highest number of COVID-19 cases, displaying their respective fatality rates (calculated as deaths per confirmed case). The right panel presents a comparative chart, where diagonal lines indicate different fatality rate thresholds. Countries positioned along higher lines have greater observed fatality rates, with the 20 most affected countries marked for emphasis. The data were derived from the https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality

Epigenetic drivers of the cardiovascular pathogenesis of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has revealed a complex epigenetic mechanism facilitating cardiovascular complications, highlighting the role of DNA methylation, histone modification, microRNA (miRNA) deregulation, metabolic reprogramming, and faster ripening of the human body during disease pathogenesis (table 6). Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) are epigenetically managed to facilitate viral entry, with DNA methylation affecting their expression in an age-and comorbidity-dependent manner [128, 129]. The hypomethylation of ACE2 in adult patients, particularly those with diabetes who have a previous smoking history, contributes to viral entry and worsens cardiovascular damage, whereas children have protective hypermethylation, thereby reducing susceptibility [128]. After SARS-CoV-2 infection, downregulation of ACE2 disrupts the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), leading to increased vasoconstriction, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction. These pathophysiological changes are fundamental mechanisms underlying the development of hypertension and other cardiovascular complications in COVID-19. The resulting endothelial dysfunction and vascular injury can contribute to both acute and long-term cardiovascular sequelae [130]. Genome-wide methylation research has also revealed hypermethylation of the antiviral genes IFNAR2 and OAS1, as well as hypomethylation of proinflammatory sites such as IL-6 and TNF-α, which creates a cytokine storm environment. Increased IL-6 levels, which are associated with hypomethylation of one of the promoters, are correlated with myocardial injury and poor prognosis, magnifying systemic inflammation and promoting cardiomyocyte apoptosis, microvascular thrombosis, and cardiac arrhythmia [131].

SARS-CoV-2 also manipulates histone modifications to avoid immune detection and enlists histone deacetylases (HDACs) to calm interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) via the inhibitory marker H3K27me3, thus suppressing untimely antiviral responses. Moreover, viruses degrade histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and disrupt the chromatin structure essential for the activation of the immune system [132]. These epigenetic changes result in H3K4me3 activation in addition to the proinflammatory cytokine gene of cardiac macrophages, fuelling TN-and IL-1 production, which damages the myocardium [131]. However, endothelial cells exhibit reduced H3K9ac via vascular homeostasis genes, which promote endothelial and thrombotic events. The current histone-driven dysregulation initiates a barbarian cycle of inflammation and oxidative stress, worsening myocardial inflammation, acute coronary syndrome, and microvascular dysfunction [133].

MicroRNA imbalances further underpin COVID-19 cardiovascular pathology, with miR-223 upregulation promoting neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation and hypercoagulability, whereas miR-126 downregulation compromises endothelial integrity, increasing D-dimer levels and thrombosis risk [134]. SARS-CoV-2 uses host miRNAs, such as miR-21, to enhance ACE2 protein articulation and viral entry, whereas miR-146a suppression triggers NF-B-mediated inflammation and cardiac damage. Promoting miR-155 in COVID-19-associated cardiomyopathy drives macrophage polarization toward a profibrotic phenotype, worsening systolic dysfunction and myocardial fibrosis. These miRNA changes are not simply bystanders but are mechanistically related to clinical results, indicating their curative potential [135].

Metabolic reprogramming triggered by SARS-CoV-2 interferes with epigenetic control, as it downregulates the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation genes, consumes ATP, and disrupts mitochondrial function. Cardiomyocytes are depleted of vital energy due to hypomethylation of PDK4 and hypermethylation of CPT1A, which disrupts fatty acid oxidation. The resulting metabolic stress activates NADPH oxidase and generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that oxidize CaMKII, trip sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium, and cause cardiac arrhythmia. The depletion of-ketoglutarate (α-KG), a cofactor of the DNA demethylation enzyme, stabilizes hypermethylation close to an antioxidant gene such as SOD2 and contributes to oxidative damage in cardiac tissue [136, 137].

Epigenetic aging has emerged as a critical determinant of long-term cardiovascular risk, with patients experiencing severe COVID-19 displaying evidence of accelerated biological aging as measured by DNA methylation clocks. Notably, hypermethylation of vascular aging-associated genes such as ELOVL2 and FHL2 has been correlated with endothelial dysfunction and the development of atherosclerosis. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2-induced biological aging is associated with activation of the mTOR signaling pathway, which in turn increases the expression of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) implicated in aging processes, such as SIRT1 [138]. The postrecovery cardiac arrhythmia and consequent disappointment may be explained by the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) of endothelial cells, which maintains myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction [139, 140].

Therapeutic strategies targeting these epigenetic mechanisms hold promise. HDAC inhibitors such as vorinostat and DNMT inhibitors such as azacytidine may restore interferon signaling and reduce the viral load, whereas miR-126 mimics and miR-223 antagonists could mitigate endothelial dysfunction and thrombosis [141]. Personalized approaches leveraging epigenetic clocks might identify high-risk patients for early senolytic therapies (e. g., dasatinib) or NAD+boosters to counteract mitochondrial dysfunction. Combining epidrugs with antivirals or vaccines could enhance T-cell memory and reduce long-term cardiovascular sequelae, underscoring the need for epigenetically informed precision medicine in pandemic recovery efforts [140, 142].

Table 6: Epigenetic mechanisms and associated diseases in the pathogenesis of COVID-19

| Epigenetic driver | Mechanism | Associated diseases | Key insights | Ref |

| DNA Methylation (5mC) | Gene silencing via promoter methylation | Cancer, metabolic disorders, neurological diseases | Aberrant methylation of tumor suppressor genes drives cancer; key role in gene‒environment interactions | [143] |

| Histone Acetylation (e. g. H3K27ac) | Chromatin relaxation and gene activation | Cancer, cardiovascular, neurological disorders | Disruption alters gene accessibility and expression | [144] |

| Histone Methylation (e. g. H3K4me3, H3K27me3) | Gene activation or repression | Cancer, autoimmune, imprinting disorders | Specific patterns regulate enhancers and silencing elements | [145] |

| Noncoding RNAs (miRNAs, lncRNAs) | Posttranscriptional regulation | Cancer, neurodegenerative disorders | Dysregulation affects pathways like apoptosis and cell cycle | [146] |

| Imprinting Defects | Parent-specific gene expression | Prader-Willi, Angelman, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndromes | Epimutations and uniparental disomy alter developmental gene expression | [147] |

| Chromatin Remodeling Complexes (e. g. SWI/SNF) | Nucleosome repositioning | Cancer, developmental disorders | Mutations in chromatin remodelers lead to widespread transcriptional deregulation | [148] |

| Hydroxymethylation (5hmC) | Active DNA demethylation | Liver cancer, neurodevelopmental diseases | Decrease in 5hmC observed in liver cancer; dynamic marker of cell identity | [145] |

| TET Enzymes (e. g., TET2) | Convert 5mC to 5hmC | Leukemia, solid tumors | Mutations linked to global DNA methylation changes | [149] |

| IDH1/2 Mutations | Indirectly inhibit TET enzymes | Glioma, AML | Leads to CpG island hypermethylator phenotype (CIMP) | [149] |

| CpG Island Methylator Phenotype (CIMP) | Global promoter methylation | Colorectal, glioblastoma, gastric cancers | Associated with tumor suppressor gene silencing and genetic instability | [149] |

| Environmental Epigenetic Memory | Persistent changes postexposure | Liver disease, metabolic disorders | Epigenetic scars from alcohol, viral infection, or diet persist and contribute to disease progression | [145] |

| Circadian Epigenetic Oscillations | Temporal methylation cycles | Aging, complex diseases | Rhythmic cytosine modifications influence disease timing and progression | [150] |

| Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) | Remove acetyl groups, gene repression | Cancer, fibrosis, neurological conditions | HDAC inhibitors are promising epigenetic therapies | [151] |

| DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) | Add methyl groups to DNA | Cancer, imprinting disorders | Overexpression leads to hypermethylation of tumor suppressors | [152] |

| Global Hypomethylation | Genome instability | Cancer | Loss of methylation contributes to chromosomal instability and oncogene activation | [149] |

Personalized medicine approaches based on genomics and virology