Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 232-240Original Article

NEUROPROTECTIVE EFFECTS OF DONEPEZIL AND FLUOXETINE VIA GSK-3 PATHWAY IN A TRANSGENIC DROSOPHILA MODEL OF ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE: NEUROPSYCHIATRIC AND BEHAVIOURAL ANALYSIS

PRIYANKA LG, BHARAT B. J., K. L. KRISHNA*

Department of Pharmacology, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore-570015, India

*Corresponding author: K. L. Krishna; *Email: klkrishna@jssuni.edu.in

Received: 09 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 04 Sep 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study investigates the neuroprotective effects of Donepezil and Fluoxetine in a transgenic Drosophila melanogaster model of AD, with a specific focus on modulation of the GSK-3 signalling pathway.

Methods: Transgenic Drosophila flies expressing the UAS-ELAV-GAL4 system were divided into four groups: (1) Normal, (2) Disease Control, (3) Donepezil 100 µM (DPZ), and (4) Fluoxetine 10 µM (FLX), treated for 21 d. Behavioural assays (negative geotaxis, open field) were conducted to assess locomotor function. Biochemical analyses, including oxidative stress markers (CAT, MDA, GSH) and neurotransmitters (dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine), were measured. Immunohistochemistry was used to qualitatively assess the expression of Aβ, GSK-3, and neuroinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) in fly brains.

Results: Transgenic Drosophila melanogaster expressing AD pathology exhibited elevated levels of oxidative stress markers, neurotransmitter deficits, and marked neuroinflammation. Donepezil and Fluoxetine significantly (p≤0.05) reduced MDA levels and restored CAT and GSH levels, indicating improved antioxidant defence. Both treatments also reversed reductions in dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine levels significantly (p≤0.05) when compared to the control group, suggesting neurochemical restoration. Immunohistochemistry revealed decreased Aβ, GSK-3, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) following treatment, with Fluoxetine demonstrating comparatively greater modulation. Histological analysis confirmed improved neuronal integrity, particularly in the Fluoxetine-treated group, indicating superior neuroprotective efficacy.

Conclusion: Donepezil and Fluoxetine confer neuroprotection by enhancing locomotor function, reducing oxidative stress, restoring neurotransmitter balance, and attenuating neuroinflammation. Notably, Fluoxetine’s modulation of serotonergic-GSK-3 signalling suggests it may augment standard AD therapy by targeting both cholinergic and non-cholinergic mechanisms, offering a promising adjunctive strategy for disease management.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Drosophila melanogaster, Donepezil, Fluoxetine, GSK-3 signalling, Neuroinflammation

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55475 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and depression are two of the most pressing global mental health challenges due to their increasing prevalence and profound societal impact [1]. A growing body of research over the past decades has highlighted a significant association between these conditions, although the precise biological mechanisms linking them remain complex and not fully understood [2]. Evidence suggests that depression during midlife may increase the risk of developing AD later in life, and persistent depressive symptoms in older adults may serve as early indicators of cognitive decline [3].

The pathophysiological overlap between AD and depression involves multiple factors, including genetic susceptibility, neuroimmune alterations, and the accumulation of hallmark proteins such as amyloid-beta (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau [3]. Despite advancements in therapeutic strategies ranging from pharmacological treatments to lifestyle interventions, there remains a lack of cohesive models that explain the bidirectional relationship between these disorders [4]. This highlights a critical need for mechanistic studies that can bridge the gap between mood disorders and AD pathology, and explore dual-action therapeutic approaches targeting both conditions.

Cognitive impairments in AD and mood disorders often extend to deficits in estimating continuous quantities such as time, distance, and weight [5]. These impairments have been proposed as early diagnostic markers for neurodegenerative conditions, with some studies indicating that such deficits may precede overt clinical symptoms [6]. This highlights the importance of early detection, particularly in individuals with a history of mood disorders, where subtle cognitive and sensorimotor changes may reflect underlying neuropathology [6].

Given the need for robust and translationally relevant AD models, Drosophila melanogaster has emerged as a valuable system for investigating AD-related metabolic and molecular alterations [7, 31, 32]. Compared to mammalian models, Drosophila offers a short life cycle, low maintenance cost, and a well-annotated genome, making it ideal for rapid experimentation [8]. Importantly, Drosophila shares a highly conserved glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) signalling pathway with mammals, enabling the study of tau phosphorylation and Aβ toxicity in a genetically tractable context [9]. The fly model also supports rapid and high-throughput genetic screening, allowing researchers to dissect complex gene-environment interactions and identify novel therapeutic targets with efficiency unmatched by mammalian systems [8]. Additionally, Drosophila exhibits conserved metabolic pathways relevant to AD, including insulin/IGF signalling, mitochondrial dynamics, and lipid metabolism [10]. The simplicity of its nervous system, combined with sophisticated molecular tools such as GAL4/UAS expression systems, CRISPR-based gene editing, and RNAi libraries, makes it uniquely suited for dissecting the interplay between neurodegeneration and metabolic dysfunction, while enabling real-time observation of disease progression and therapeutic response [10].

GSK-3 is a central regulator in AD pathology, contributing to tau phosphorylation, Aβ generation, synaptic dysfunction, and cognitive deficits [11]. Recent findings indicate that serotonergic signalling can inhibit GSK-3β through activation of the AKT/PDK1 pathway, a mechanism enhanced by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as Fluoxetine. This interaction may help restore synaptic plasticity and neuronal resilience, offering a potential therapeutic link between depression and AD [12]. Previous studies have also demonstrated that modulating GSK-3 activity in Drosophila can reduce Aβ-induced neurotoxicity and improve neuronal function, reinforcing its utility in modelling AD pathogenesis [13]. Additionally, the fly model has been successfully used in drug screening pipelines, accelerating the identification of compounds with neuroprotective potential.

Despite these advancements, there is a notable lack of studies that simultaneously explore the comparative and combinatorial effects of cholinergic and serotonergic agents on neurodegeneration within a genetically tractable model. Addressing this gap could improve our understanding of the interconnectedness of neurotransmitter systems in AD and depression and support the development of multi-target therapies.

This study investigates the neuroprotective effects of Donepezil and Fluoxetine in a transgenic Drosophila melanogaster model of AD. We assess their impact on locomotor behaviour, oxidative stress, neurotransmitter levels, and neuroinflammatory markers. By comparing these treatments, we aim to elucidate the roles of cholinergic and serotonergic pathways—particularly GSK-3 modulation—in AD pathogenesis and therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals are reagents

All the reagents and chemicals used in the study were of analytical grade. Major chemical like Acetylcholine chloride (CAS Number: 2260-50-6), Dopamine (CAS Number: 62-31-7), and serotonin (CAS Number: 50-67-9) was procured from Sigma–Aldrich. Trichloroacetic acid (CAS No. 76-03-9), Thiobarbituric acid (CAS No. 504-17-6), DTNB (Ellman’s Reagent) (CAS No. 69-78-3), Tris-HCl (CAS No. 1185-53-1), and Pyrogallol (CAS No. 87-66-1) were obtained from SRL. Hydrogen peroxide (CAS No. 7722-84-1) was obtained from Merck. Reduced glutathione was procured from Himedia. Primary antibody: Beta Amyloid-Santa Cruz, catalog no: sc-374527, TNF Alpha–Abcam, ab1793, IL-1β – Cell Signalling, 12242S, IL-6-Santa Cruz, sc-57315, GSK3 beta Antibody (1F7)-Santa Cruz, sc-53931.

Fly stocks

Gene overexpression was achieved using the GAL4-UAS binary expression system. Appropriate genetic crosses were performed between UAS lines and a pan-neuronal GAL4 driver to facilitate targeted expression of human Aβ42 in the fly nervous system. Virgin female flies carrying the elav-GAL4 driver on the X chromosome were crossed with male flies harbouring the UAS-Aβ42 transgene on the second chromosome. Crosses were maintained at 25 °C under standard culture conditions. The resulting progeny, with the genotype UAS-Aβ42/+; elav-GAL4/+, expressed human Aβ42 specifically in neurons and were referred to as AD model flies [14]. Wild-type Oregon-K flies were used as the normal control group, while untreated AD model flies served as the disease control group.

Preparation of culture media

The drug concentrations—10 µM fluoxetine and 100 µM donepezil—were selected based on prior Drosophila studies to ensure relevance and avoid arbitrary dosing. Fluoxetine at 10 µM has been shown to effectively slow serotonin reuptake without causing toxicity in Drosophila CNS [33]. Although Donepezil is commonly used at higher concentrations (0.1–10 mM), 100 µM was selected as a conservative, lower-end dose to assess potential early effects [34]. This approach allows the detection of subtle behavioural and biochemical changes while minimizing off-target effects. The selected doses are thus grounded in previously published Drosophila work.

In line with Siddique et al. (2024), where Donepezil and Fluoxetine were directly mixed into fly food without mention of solvent use [34], we administered both drugs by incorporating them directly into the cornmeal-agar medium. This method is widely accepted in Drosophila studies and avoids complications associated with vehicle interference. All flies were maintained under standard laboratory conditions at 25 °C, 60–70% humidity, and a 12 h light/dark cycle. The flies were allowed to feed on the treated diet for 15 d before tissue collection and analysis [15]. A complete work model was described in fig. 1. Wild-type and transgenic Drosophila melanogaster were utilized in this study to investigate the neuroprotective effects of Donepezil and Fluoxetine. The flies were divided into four experimental groups (table 1), each consisting of 15 flies per group.

Fig. 1: Detailed study protocol for investigation of the therapeutic impact of donepezil and fluoxetine in transgenic AD Drosophila model

Table 1: Grouping and treatment for investigation of the therapeutic impact of donepezil and fluoxetine in transgenic AD Drosophila model

| Groups | Treatment | Number of flies |

| Normal Control | Normal diet | 15 |

| Disease Control | Normal diet | 15 |

| Donepezil 100 µM (DPZ) | Normal diet+100 µM DPZ | 15 |

| Fluoxetine 10 µM (FLX) | Normal diet+10 µM FLX | 15 |

Behavioural assays

Negative geotaxis assay

A negative geotaxis assay was used to examine the locomotor abilities of adult flies. At each time point, ten male adult flies were placed in a (17.5 cm×2.5 cm) long glass tube (fig. S1). A horizontal line was drawn 08 cm above the bottom of the vial. After the flies had acclimated for 1 minute, both control and treated groups were assayed manually at random, and the total number of flies that escaped beyond the minimum distance of 08 cm in 10 seconds was counted manually across all three groups [16].

Open field arena test

Exploratory locomotion was evaluated using a circular arena with a diameter of 15 cm, subdivided into 1 cm² squares. Individual flies were placed in the arena, and their movement was observed for 60 sec (fig. S2). The number of square crossings, defined as the complete entry of the fly’s body into a new square, was manually recorded. The experiment was conducted in four independent replicates, with each group consisting of 60 flies [17].

Biochemical analysis: assessment of antioxidant enzyme activity

Catalase (CAT) activity assay

CAT activity was determined as per the procedure described by [18]. The reaction mixture contains 190 μl of phosphate buffer (50 mmol, pH 7) and 100 μl of Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). 10 μl of tissue supernatant was added. The change in absorbance was monitored for 3 min at 30 sec intervals, and the absorbance was recorded at 240 nm using a nano-drop plate reader (MULTISKAN Sky-high, Thermo Scientific). The CAT activity was represented as μmol of H2O2 hydrolysed/min/mg of protein [18].

Lipid peroxidation (LPO) activity

Malondialdehyde (MDA), a crucial indicator of oxidative damage, was measured to assess the degree of lipid peroxidation. For the experiment, 150 µl** of the sample was incubated for one hour at 90 °C in a water bath with 2 ml of a 1:1:1 mixture of thiobarbituric acid (TBA, 0.37%), trichloroacetic acid (TCA, 15%), and hydrochloric acid (HCl, 0.25 N). The reaction mixture was centrifuged for five minutes at 4 °C and 3000 rpm after cooling. After gathering the pink supernatant, absorbance was measured at 535 nm in comparison to a blank. The extinction coefficient used to compute the MDA concentration was 156,000 M⁻¹ cm⁻¹ [20].

Reduced glutathione (GSH) activity

After combining 500 μl of brain tissue supernatant with 1 ml of TCA (5%) and letting it sit at 40 °C for an hour, it was centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C at 3000 rpm. In short, 200 μl of supernatant was incubated for 5 min at room temperature with a reaction mixture that contained 50 μl of DTNB (20 mmol) and 1.8 ml of phosphate buffer (0.1M, pH 7). A nano-drop plate reader (MULTISKAN Sky-high, Thermo Scientific) was used to quantify the OD of yellow colour development at 412 nm, and the GSH concentration was expressed as μmol/mg of protein [19].

Neurotransmitter analysis using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

HPLC was employed to quantify key neurotransmitters, including acetylcholine (ACh), serotonin (5-HT), and dopamine. Drosophila flies were euthanized by immersion in ice-cold water (2–4 °C). Brains were carefully dissected using surgical scissors and homogenized in chilled methanol. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected for analysis. Neurotransmitter ACh, 5-HT, and dopamine levels were measured by injecting 10 µl of the sample into a C18 HPLC column (LC-20AD, 250×4.6 mm), with detection at 280 nm using a UV detector. The mobile phase consisted of methanol and acetonitrile in a 70:30 ratio, flowing at 1 ml/min. Neurotransmitter standards were prepared in methanol at concentrations of 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 µg/ml for qualitative comparison (fig. S3) [21].

Immunohistochemistry studies

Neural tissue was processed for immunohistochemical analysis following the protocol. Paraffin-imgded brain sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and blocked with 8% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 150 min. Sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against Aβ precursor protein, GSK-3, and pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. After washing, slides were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with secondary goat anti-mouse antibody (1:200, Invitrogen), followed by staining with 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma). Brain sections were examined under a light microscope (200x) to assess protein accumulation [22].

Histopathological analysis

Drosophila brains were fixed overnight at 4 °C using Carnoy's solution, followed by a graded ethanol dehydration process before imgding in paraffin.21 Frontal sections of the fly brain were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HandE) to assess neuroanatomical features, including neuronal integrity and degenerative changes [23].

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean±SEM and analysed using SPSS version 24. Behavioural assays were assessed using repeated measures ANOVA, while biochemical assays were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Behavioural activity

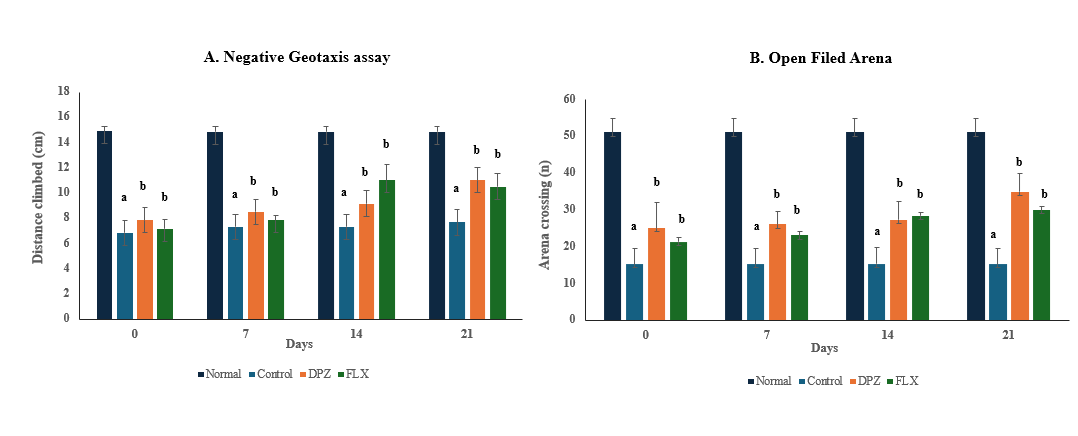

Negative geotaxis activity

A negative geotaxis assay was conducted to assess the locomotor function of Drosophila melanogaster over a 10 sec period. The normal group exhibited significantly greater climbing ability (14.85 cm) compared to the disease model control group (7.29 cm), indicating impaired motor function. Treatment with Donepezil (9.13 cm) and Fluoxetine (9.12 cm) over 21 d significantly improved climbing performance relative to the control group (F(Control)(3,12)=30.65;p≤0.05), suggesting a potential neuroprotective effect of these drugs in restoring locomotor function (fig. 2A).

Open field arena assay

The open field arena test was conducted over a 60 sec period to assess exploratory locomotion based on the number of crossings. The normal group exhibited significantly more crossings (51 crossings) compared to the disease model control group (15 crossings), indicating a reduction in exploratory behaviour due to disease pathology. Treatment with Donepezil (28.3 crossings) and Fluoxetine (25.62 crossings) over 21 d significantly increased the number of crossings relative to the control group (F(Control) (3,12)= 99.01; p ≤ 0.05), suggesting improvements in both motor and cognitive functions (fig. 2B).

Lipid peroxidation (LPO)

Flies expressing AD pathology exhibited a significant increase in MDA levels, indicating elevated lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress (p≤0.05). Treatment with Donepezil and Fluoxetine significantly reduced MDA levels (p≤0.05), suggesting their potential to mitigate lipid peroxidation and protect neuronal membranes (table 2).

Catalase (CAT) activity

CAT activity was markedly reduced in transgenic AD flies compared to normal controls (p≤0.05), reflecting compromised antioxidant defence. However, administration of Donepezil and Fluoxetine significantly restored CAT activity (p≤0.05), indicating their antioxidant potential (table 2).

Reduced glutathione (GSH) levels

GSH levels were significantly depleted in AD flies (p≤0.05), highlighting impaired redox balance. Treatment with Donepezil and Fluoxetine significantly elevated GSH levels (p≤0.05), suggesting enhanced neuroprotection (table 2).

Fig. 2: Donepezil and fluoxetine improve locomotor activity in D. melanogaster, indicating neuroprotective and motor-restorative effects, (A) Negative geotaxis activity and (B) Open field arena activity, biochemical activity: endogenous markers of oxidative stress

Table 2: Donepezil and fluoxetine attenuate oxidative stress in transgenic AD Drosophila melanogaster. (Endogenous antioxidant enzymes: MDA; CAT; GSH; SOD)

| Group | MDA (µmol/mg of protein) | CAT (µmol/min/mg of protein) | GSH (µmol/mg of protein) |

| Normal | 0.100±0.02 | 0.395±0.03 | 1.295±0.09 |

| Control | 0.392±0.03a | 0.256±0.02a | 0.636±0.02a |

| Donepezil | 0.175±0.07b | 0.366±0.02b | 1.147±0.03b |

| Fluoxetine | 0.142±0.02b | 0.386±0.01b | 1.311±0.04b |

Value are expressed as mean±SEM, (n=15/group: triplicates/group), p<0.05 aSignificant when compared with normal group, p<0.05 bSignificant when compared with control group

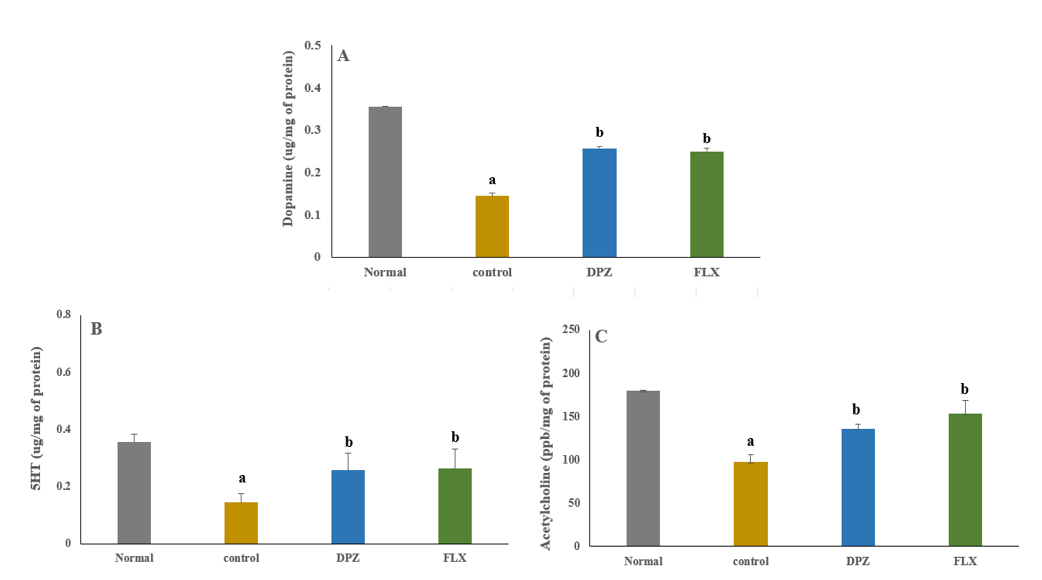

Neurotransmitter dopamine, serotonin and acetylcholine in flies brain

Neurotransmitter profiling revealed a significant reduction in dopamine levels (p≤0.05) in transgenic AD flies compared to normal controls, indicating dopaminergic dysfunction associated with AD pathology. Treatment with Donepezil and Fluoxetine significantly restored dopamine levels (p≤0.05), suggesting their potential role in preserving dopaminergic signalling and mitigating neurodegeneration (fig. 3A).

Serotonin depletion, often linked to mood disturbances and neurodegenerative progression, was significantly observed in transgenic AD flies (p≤0.05). Administration of donepezil and fluoxetine significantly reversed this decline (p≤0.05), indicating their efficacy in restoring serotonergic neurotransmission and potentially improving behavioural outcomes (fig. 3B).

A marked reduction in acetylcholine levels (p≤0.05) was detected in transgenic AD flies, consistent with cholinergic deficits that are a hallmark of AD. Treatment with Donepezil and Fluoxetine significantly increased acetylcholine levels (p≤0.05), highlighting their role in enhancing cholinergic function and supporting cognitive performance (fig. 3C).

Fig. 3: Restoration of neurotransmitter levels in transgenic ad flies following donepezil and fluoxetine treatment (A-Dopamine, B-Serotonin, and C-Acetylcholine, respectively), value are expressed as mean±SEM, (n=15/group: triplicates/group), p<0.05 aSignificant when compared with the normal group, p<0.05 bSignificant when compared with the control group

Immunohistochemical analysis

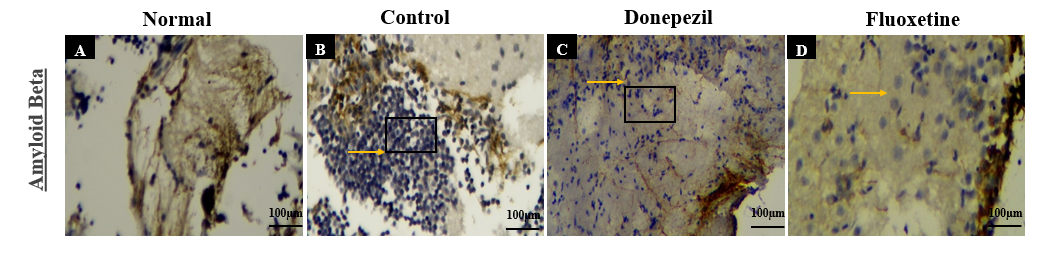

Aβ expression

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed distinct differences in Aβ expression across experimental groups. In the normal group, physiological levels of Aβ were observed with no visible aggregation in the brain regions (fig. 4A). In contrast, the control group exhibited substantial overexpression of Aβ, indicated by intense immunoreactivity (Orange arrows, fig. 4B), consistent with AD pathology.

Treatment with Donepezil resulted in a mild reduction in Aβ expression, with preservation of neuronal morphology (fig. 4C), suggesting partial neuroprotection. The Fluoxetine-treated group showed a moderate decrease in Aβ levels (fig. 4D), indicating potential neuroprotective effects through serotonergic modulation.

Fig. 4: Immunohistochemical analysis of Aβ expression Drosophila fly brain regions across experimental groups: (A) Normal group showing baseline Aβ levels; (B) Control group with marked Aβ overexpression (orange arrows), indicating AD-like pathology; (C) Donepezil-treated group with mild Aβ expression, suggesting partial neuroprotection; (D) Fluoxetine-treated group showing moderate Aβ reduction with slightly reduced neuronal density

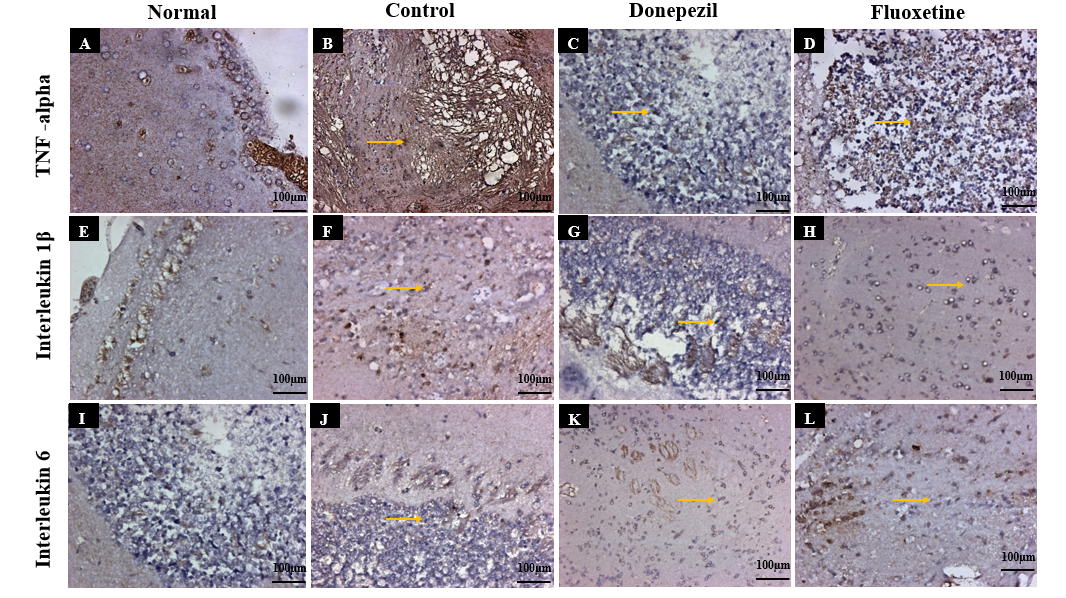

Pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) expression

Inflammation plays a crucial role in neurodegeneration, and the immunohistochemical analysis of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α,IL-6 and IL-1β) provided insight into the neuroinflammatory responses in transgenic AD Drosophila. In the normal group, basal expression levels of TNF-α,IL-6 and IL-1β were observed, indicating a normal immune response. (fig. 5A, 5E, 5I). However, in the control group, a pronounced overexpression of these cytokines was detected in the forebrain and midbrain regions (Orange arrow, fig. 5B, 5F, 5J). The increased cytokine levels suggest chronic neuroinflammation, which is known to exacerbate neuronal loss and synaptic dysfunction in AD. Donepezil-treated flies exhibited mild expression of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, with reduced neuroinflammatory responses compared to the control group (fig. 5C, 5G, 5K). This suggests that Donepezil may help attenuate neuroinflammation by modulating acetylcholine-mediated anti-inflammatory pathways. In contrast, the Fluoxetine-treated group demonstrated a mild to moderate reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (fig. 5D, 5H, 5L) further supporting Fluoxetine’s role in mitigating neuroinflammation via serotonergic and anti-inflammatory pathways.

Fig. 5: Immunohistochemical analysis of Pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) expression in Drosophila fly brain regions across experimental groups: (A,E,I) Normal group showing baseline TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β levels balanced immune response; (B,F,J) Control group with marked TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β overexpression, the increased cytokine levels suggest chronic neuroinflammation, which is known to exacerbate neuronal loss and synaptic dysfunction in AD (orange arrows), indicating AD-like pathology; (C,G,K) Donepezil-treated flies exhibited mild reduction in expression of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, indicating reduced neuroinflammatory responses compared to the control group; (D,H,L) Fluoxetine-treated group demonstrated a moderate reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokine expression of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, further supporting Fluoxetine’s role in mitigating neuroinflammation via serotonergic and anti-inflammatory pathways

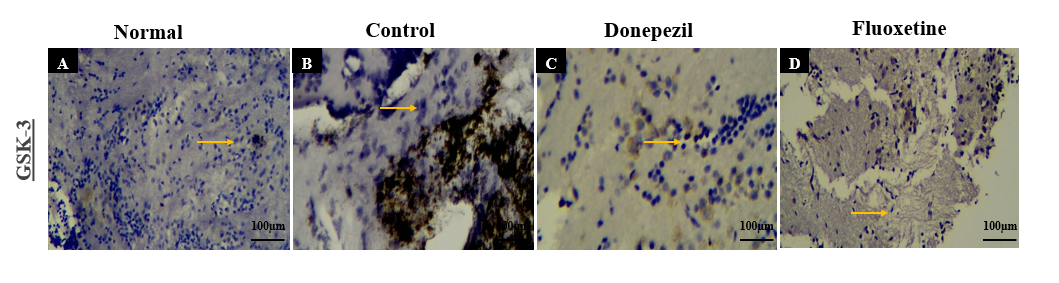

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) expression

GSK-3was significantly elevated in transgenic AD flies (fig. 6A), compared to normal flies (fig. 6B), Donepezil-treated flies showed mild expression (fig. 6C) while Fluoxetine-treated flies exhibited moderate GSK-3 expression with neuronal preservation (fig. 6D).

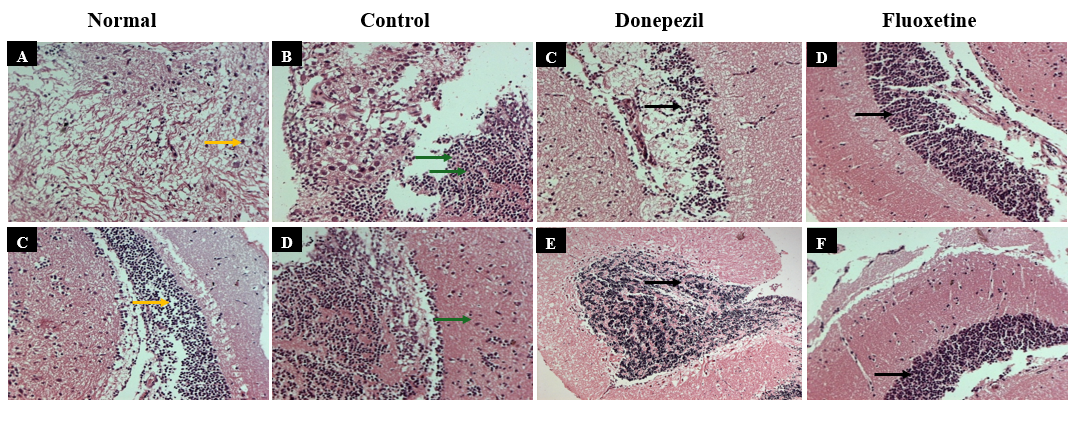

Haematoxylin and eosin staining

Hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining was performed to assess neuronal integrity across experimental groups. The normal group (fig. 7A and C) exhibited well-preserved brain architecture with intact neuronal morphology and no signs of degeneration. In contrast, transgenic AD flies (fig. 7B and D) showed pronounced histopathological changes, including neuronal shrinkage, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and evidence of apoptosis, indicative of neurodegeneration.

Donepezil-treated flies (fig. 7C and E) demonstrated moderate preservation of neuronal structure, with reduced signs of degeneration compared to the untreated AD group, suggesting partial neuroprotection. Interestingly, Fluoxetine-treated flies (fig. 7D and F) displayed near-normal neuronal morphology, with minimal structural abnormalities, indicating a potentially stronger neuroprotective effect, possibly through its anti-inflammatory and serotonergic mechanisms.

Fig. 6: Immunohistochemical analysis of GSK3 expression in Drosophila fly brain regions across experimental groups: (A) Normal group showing balanced GSK3 levels; (B) Control group with GSK3 overexpression (Orange arrows), indicating AD-related inflammation; (C) Donepezil-treated group showing mild GSK3 reduction, suggesting partial anti-inflammatory effect; (D) Fluoxetine-treated group with mild to moderate GSK3 decrease, supporting its anti-inflammatory role

Fig. 7: Histological analysis using H and E staining (200x magnification) revealed well-preserved neuronal architecture in the normal group (Orange arrows). The AD control group showed marked neurodegeneration, including neuronal apoptosis (red arrows) and Purkinje cell loss (Black arrows). Donepezil treatment reduced cortical damage, indicating moderate neuroprotection. Fluoxetine-treated flies exhibited preserved neurons and myelin sheaths, suggesting stronger neuroprotective effects.

DISCUSSION

AD is a complex neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive cognitive decline, neuronal loss, and dysfunction across multiple molecular pathways [24]. This study investigated the neuroprotective effects of Donepezil and Fluoxetine using a transgenic Drosophila melanogaster model of AD. Both agents demonstrated beneficial effects across key pathological domains, including oxidative stress, neurotransmitter imbalance, neuroin flammation, structural integrity, and locomotor function. Notably, Fluoxetine exhibited broader efficacy, suggesting potential for therapeutic repurposing in the AD context.

Oxidative stress, one of the early contributors to AD pathophysiology, was significantly elevated in untreated transgenic flies, as reflected by increased MDA levels and reduced antioxidant enzyme activities. The restoration of CAT and GSH levels following treatment indicates that both Donepezil and Fluoxetine can enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses. This effect likely results from direct free radical scavenging and modulation of redox signaling, which, in turn, may protect neurons from lipid peroxidation and cellular damage [25]. Comparable findings were reported by Sharma et al. (2021), who observed that Fluoxetine treatment reduced oxidative stress markers and restored antioxidant balance in rodent AD models, [26] and by Wango et al. (2015), who confirmed Donepezil’s antioxidant-enhancing capacity in Aβ-expressing mice. These parallels strengthen the reliability of our observations [27].

Restoration of neurotransmitter levels was another prominent effect observed in this study. Acetylcholine levels were markedly reduced in AD flies, consistent with cholinergic system disruption in disease. Donepezil restored acetylcholine through acetylcholinesterase inhibition, while Fluoxetine also elevated acetylcholine levels, possibly via serotonin-mediated modulation of cholinergic tone. In addition, both dopamine and serotonin, which influence executive function, mood, and motivation, were significantly increased after Fluoxetine administration. This could be attributed to its ability to modulate monoaminergic systems indirectly via neurotrophic support, including increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), known to regulate dopaminergic and serotonergic signaling [28]. The normalization of these neurotransmitters likely contributes not only to improved cognitive functions but also to behavioral stabilization. Similar neurotransmitter-restoring effects of SSRIs in AD have been reported by Kobayashi et al. (2012), who demonstrated increased serotonin and dopamine turnover with fluoxetine treatment, correlating with improved cognitive and behavioural outcomes [29]. Our findings align with this evidence, highlighting conserved serotonergic–cholinergic cross-talk across models.

Histopathological analysis confirmed extensive neurodegeneration in the disease model, including loss of structural architecture and cellular density. While Donepezil mitigated this degeneration to a moderate extent, Fluoxetine offered near-complete structural preservation. Interestingly, despite this histological improvement, the neuron count in Fluoxetine-treated flies was slightly lower compared to Donepezil. This addresses the concern of neuron reduction despite neuroprotection and may reflect enhanced clearance of apoptotic debris, a plausible outcome of Fluoxetine-induced microglial or glial activation, facilitating tissue cleanup rather than indicating further neurotoxicity. This observation echoes findings from Zhang et al. (2017), who reported that fluoxetine preserved dentate gyrus neurons and improved cognition in APP/PS1 mice, while CA1/CA3 regions remained unaffected, suggesting regionally selective neuroprotection [30].

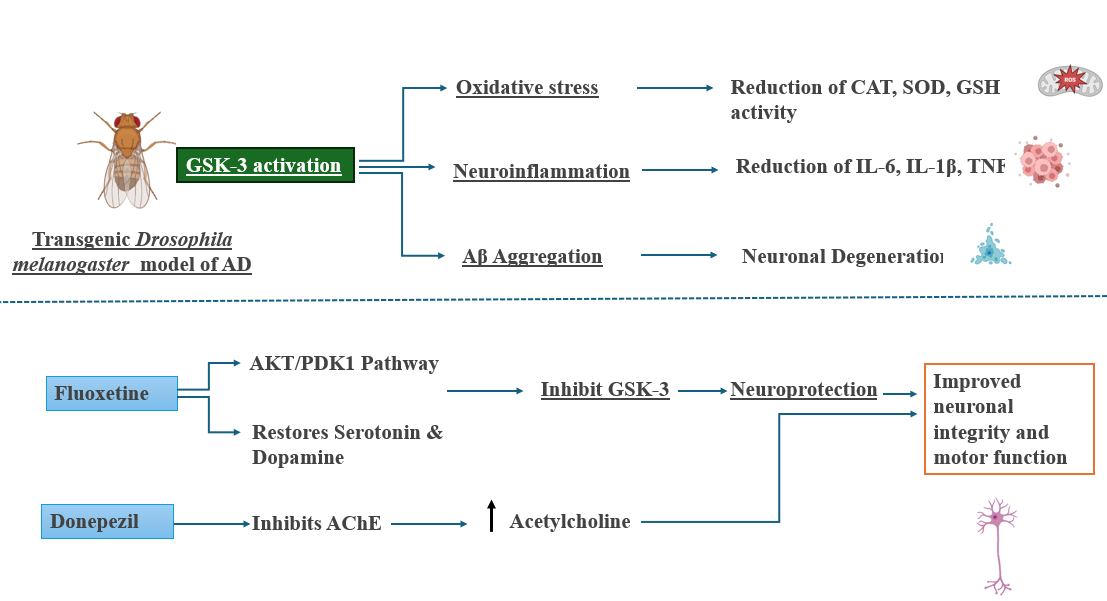

One of the central findings of this study is the modulation of GSK-3, a key kinase involved in several AD-relevant pathways [31]. GSK-3 activity was markedly elevated in the AD model, while both treatments downregulated its expression. The more robust suppression by Fluoxetine suggests the involvement of upstream signaling cascades. Specifically, Fluoxetine is known to activate the PI3K/AKT pathway, leading to inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK-3β at Ser⁹. Additionally, its influence on Wnt/β-catenin signaling and upregulation of BDNF contributes to GSK-3β inhibition [32, 33]. Our results are consistent with observations by Beurel et al. (2015), who demonstrated that SSRIs inhibit GSK-3β via AKT activation. Additionally, A 2017 study Zhao et al., demonstrated that Donepezil prevents Aβ₄₂-induced neurotoxicity via activation of PI3K/Akt and inhibition of GSK-3, leading to increased phosphorylation of AKT and GSK-3β, reduced tau phosphorylation, and overall enhanced neuronal viability. These converging findings underscore the importance of GSK-3 modulation as a therapeutic target. This mechanistic clarification directly addresses the gap identified in the discussion regarding how Fluoxetine and Donepezil downregulates GSK-3 [34. 35]. Future validation using Western blot and gene expression analysis for p-GSK-3β (Ser⁹) would strengthen these conclusions and help confirm pathway-specific effects in this model.

Inflammation is another driving force in AD progression [36]. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, were observed in the untreated disease group, consistent with a chronically activated immune state. Both drugs attenuated this inflammatory response, with Fluoxetine showing greater reductions. This may be attributed to its known actions on microglial cells, where SSRIs can reduce cytokine production by inhibiting NF-κB signaling and related transcriptional activators. By suppressing neuroinflammation, Fluoxetine may contribute to breaking the vicious cycle of oxidative stress and cellular injury. Similar anti-inflammatory profiles have been reported in prior rodent study by Chen et al. 2022. Fluoxetine has been shown to suppress IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α production in hippocampal and microglial cultures—largely via NF-κB inhibition. Meanwhile, donepezil has been demonstrated to reduce IL-1β and IL-6 expression and attenuate microglial/astrocytic activation in AD mouse models. These converging findings reinforce the translational consistency of our anti-inflammatory observations [37].

Behaviorally, AD flies showed reduced motor function, including impaired negative geotaxis and exploratory behavior. These deficits correlate with neuronal loss and disrupted neurotransmitter signaling in key motor circuits. Both treatments improved locomotor performance, suggesting restoration of neural circuitry and improved neurotransmission. Fluoxetine demonstrated slightly superior improvements in climbing and exploration, likely due to its broader modulation of serotonergic, dopaminergic, and neurotrophic systems. These findings highlight the potential advantage of targeting multiple pathways in restoring behavioral function.

Fig. 8: Mechanistic insights into the neuroprotective effects of Fluoxetine and Donepezil in a Drosophila model of AD. GSK-3 activation in the transgenic Drosophila melanogaster AD model induces oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and Aβ aggregation, contributing to neuronal degeneration. Fluoxetine activates the PI3/AKT pathway, inhibits GSK-3, and restores serotonin and dopamine levels, leading to neuroprotection. Donepezil inhibits acetylcholinesterase (AChE), increasing acetylcholine availability in the brain. Both agents ultimately improve neuronal integrity and motor function in the AD model. Fluoxetine demonstrates a broader mechanism by targeting both neurochemical and molecular pathways

While these findings offer promising preclinical insights with a rapid and genetically tractable platform for screening, their limitations include the lack of a blood-brain barrier, which may alter drug penetration and central bioavailability. Additionally, drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics differ significantly from mammalian systems, limiting translational precision. Nevertheless, the model provides an efficient and genetically tractable platform to identify potential therapeutic targets and pathways, warranting further validation in mammalian systems. Furthermore, the present study did not quantitatively assess IHC expression levels, relying instead on qualitative observations. Future studies will incorporate these quantification outcomes to provide more objective and statistically robust IHC data.

Additionally, based on the current findings, there is a clear implication that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), when combined with cholinesterase inhibitors like Donepezil, may represent a viable clinical strategy, especially in AD patients who also exhibit depression or neuropsychiatric symptoms. This combination approach may enhance both symptomatic and potential disease-modifying outcomes.

The growing emphasis on pharmacology in AD, as highlighted by recent trials combining memantine with cholinesterase inhibitors, suggests that dual targeting of serotonergic and cholinergic systems may gain traction in clinical pipelines. Given the high prevalence of depression in AD patients, SSRIs like Fluoxetine could see repurposing not only for symptomatic relief but also for disease modification via GSK-3 and neuroinflammatory regulation. Thus, our findings support the rationale for incorporating SSRIs into future combination trials alongside standard cholinesterase inhibitors, with potential clinical uptake particularly strong in patients with comorbid neuropsychiatric manifestations.

Taken together, this study demonstrates that both Donepezil and Fluoxetine exert multi-level neuroprotection in an AD model, with Fluoxetine showing more comprehensive benefits across oxidative, inflammatory, and neurotransmitter-related domains. These results provide a strong rationale for exploring combined serotonergic and cholinergic therapeutic strategies in future clinical trials aimed at addressing the multifaceted nature of AD.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that both Donepezil and Fluoxetine offer neuroprotective benefits in a transgenic Drosophila model of AD by reducing oxidative stress, restoring neurotransmitter balance, and preserving neuronal and motor function. Fluoxetine showed superior efficacy, highlighting the therapeutic potential of serotonergic modulation. The findings support a combined cholinergic-serotonergic approach as a promising strategy for AD intervention. Future studies should explore the molecular mechanisms underlying these effects and evaluate long-term outcomes. Overall, targeting multiple neurobiological pathways may enhance therapeutic success in neurodegenerative disease management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the supporting staff of the JSS University.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore, India.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Priyanka LG: Conceptualization, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review and Editing, Data Curation, Software and Methodology; Bharat B J: Review, Editing, Revision of The Work, Resources and Visualization; K l Krishna: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Validation and Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Huang YY, Gan YH, Yang L, Cheng W, Yu JT. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiology mechanisms and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2024 Jun 1;95(11):992-1005. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2023.10.008, PMID 37866486.

Lyketsos CG, Carrillo MC, Ryan JM, Khachaturian AS, Trzepacz P, Amatniek J. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011 Sep;7(5):532-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2410, PMID 21889116, PMCID PMC3299979.

Botto R, Callai N, Cermelli A, Causarano L, Rainero I. Anxiety and depression in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of pathogenetic mechanisms and relation to cognitive decline. Neurol Sci. 2022 Jul;43(7):4107-24. doi: 10.1007/s10072-022-06068-x, PMID 35461471, PMCID PMC9213384.

Kivipelto M, Mangialasche F, Ngandu T. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment dementia and Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018 Nov;14(11):653-66. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0070-3, PMID 30291317.

Hansson O. Biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Med. 2021 Jun;27(6):954-63. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01382-x, PMID 34083813.

Ossenkoppele R, Van Der Kant R, Hansson O. Tau biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: towards implementation in clinical practice and trials. Lancet Neurol. 2022 Aug;21(8):726-34. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00168-5, PMID 35643092.

Bolus H, Crocker K, Boekhoff Falk G, Chtarbanova S. Modeling neurodegenerative disorders in Drosophila melanogaster. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Apr 26;21(9):3055. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093055, PMID 32357532, PMCID PMC7246467.

Rubin GM. Drosophila melanogaster as an experimental organism. Science. 1988 Jun 10;240(4858):1453-9. doi: 10.1126/science.3131880, PMID 3131880.

Wojcik EJ. A mitotic role for GSK-3beta kinase in Drosophila. Cell Cycle. 2008 Dec;7(23):3699-708. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.23.7179, PMID 19029800, PMCID PMC6713227.

Nitta Y, Sugie A. Studies of neurodegenerative diseases using Drosophila and the development of novel approaches for their analysis. Fly (Austin). 2022 Dec;16(1):275-98. doi: 10.1080/19336934.2022.2087484, PMID 35765969, PMCID PMC9336468.

Wang L, Li J, Di LJ. Glycogen synthesis and beyond a comprehensive review of GSK3 as a key regulator of metabolic pathways and a therapeutic target for treating metabolic diseases. Med Res Rev. 2022 Mar;42(2):946-82. doi: 10.1002/med.21867, PMID 34729791, PMCID PMC9298385.

Hui J, Zhang J, Kim H, Tong C, Ying Q, Li Z. Fluoxetine regulates neurogenesis in vitro through modulation of GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014 Dec 7;18(5):pyu099. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu099, PMID 25522429, PMCID PMC4376550.

Sofola O, Kerr F, Rogers I, Killick R, Augustin H, Gandy C. Correction: inhibition of GSK-3 ameliorates Aβ pathology in an adult-onset drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLOS Genet. 2012;8(1)e1001087. doi: 10.1371/annotation/baa8a2a9-130b-4959-b6fb-6f786fd02826.

Prußing K, Voigt A, Schulz JB. Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2013 Nov 22;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-35, PMID 24267573, PMCID PMC4222597.

Caravaca JM, Lei EP. Maintenance of a Drosophila melanogaster population cage. J Vis Exp. 2016 Mar 15;(109):53756. doi: 10.3791/53756, PMID 27023790, PMCID PMC4829027.

Cao W, Song L, Cheng J, Yi N, Cai L, Huang FD. An automated rapid iterative negative geotaxis assay for analyzing adult climbing behavior in a drosophila model of neurodegeneration. J Vis Exp. 2017 Sep 12;(127):56507. doi: 10.3791/56507, PMID 28931001, PMCID PMC5752225.

Soibam B, Mann M, Liu L, Tran J, Lobaina M, Kang YY. Open-field arena boundary is a primary object of exploration for Drosophila. Brain Behav. 2012 Mar;2(2):97-108. doi: 10.1002/brb3.36, PMID 22574279, PMCID PMC3345355.

Claiborne A. Handbook of methods for oxygen radical research. Florida CRC Press Boca Rat; 1985. p. 283-4.

Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR, Zampaglione N, Gillette JR. Bromobenzene induced liver necrosis. Protective role of glutathione and evidence for 3,4-bromobenzene oxide as the hepatotoxic metabolite. Pharmacology. 1974;11(3):151-69. doi: 10.1159/000136485, PMID 4831804.

Wright JR, Colby HD, Miles PR. Cytosolic factors which affect microsomal lipid peroxidation in lung and liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1981;206(2):296-304. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90095-3, PMID 7224639.

Nadiga AP, Krishna KL, Moin A, Abu Lila AS, Danish Rizvi SM, Sahyadri M. Exposure of zinc induced Parkinson’s disease-like non-motor and motor symptoms in relation to oxidative/nitrosative stress mediated neurodegeneration in the brain of Drosophila melanogaster. J Pharmacol Sci. 2025 Aug;158(4):303-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2025.05.010, PMID 40543992.

Goto S, Morigaki R, Okita S, Nagahiro S, Kaji R. Development of a highly sensitive immunohistochemical method to detect neurochemical molecules in formalin-fixed and paraffin imgded tissues from autopsied human brains. Front Neuroanat. 2015 Mar 3;9:22. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2015.00022, PMID 25784860, PMCID PMC4347496.

Kucherenko MM, Marrone AK, Rishko VM, Yatsenko AS, Klepzig A, Shcherbata HR. Paraffin imgded and frozen sections of Drosophila adult muscles. J Vis Exp. 2010 Dec 27;(46):2438. doi: 10.3791/2438, PMID 21206479, PMCID PMC3159657.

Perluigi M, Di Domenico F, Butterfield DA. Oxidative damage in neurodegeneration: roles in the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer disease. Physiol Rev. 2024 Jan 1;104(1):103-97. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2022, PMID 37843394, PMCID PMC11281823.

Birben E, Sahiner UM, Sackesen C, Erzurum S, Kalayci O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ J. 2012 Jan;5(1):9-19. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182439613, PMID 23268465, PMCID PMC3488923.

Sharma A, Mohammad A, Saini AK, Goyal R. Neuroprotective effects of fluoxetine on molecular markers of circadian rhythm cognitive deficits, oxidative damage and biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology induced under chronic constant light regime in Wistar rats. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2021;12(12):2233-46. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00238, PMID 34029460.

Anderkova L, Eliasova I, Marecek R, Janousova E, Rektorova I. Distinct pattern of gray matter atrophy in mild Alzheimer’s disease impacts on cognitive outcomes of noninvasive brain stimulation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(1):251-60. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150067, PMID 26401945.

Bathina S, Das UN. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its clinical implications. Arch Med Sci. 2015 Dec 10;11(6):1164-78. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.56342, PMID 26788077, PMCID PMC4697050.

Kobayashi K, Haneda E, Higuchi M, Suhara T, Suzuki H. Chronic fluoxetine selectively upregulates dopamine D₁-like receptors in the hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(6):1500-8. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.335, PMID 22278095.

Zhang J, Guo J, Zhao X, Chen Z, Wang G, Liu A. Fluoxetine increases hippocampal neurogenesis and ameliorates memory deficits in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Brain Res. 2017;1657:86-93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.11.028.

Llorens Martin M, Jurado J, Hernandez F, Avila J. GSK-3β, a pivotal kinase in Alzheimer disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2014 May 21;7:46. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00046, PMID 24904272, PMCID PMC4033045.

Yang H, Cao Q, Xiong X, Zhao P, Shen D, Zhang Y. Fluoxetine regulates glucose and lipid metabolism via the PI3K‑AKT signaling pathway in diabetic rats. Mol Med Rep. 2020 Oct;22(4):3073-80. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11416, PMID 32945450, PMCID PMC7453494.

Su HC, Ma CT, Yu BC, Chien YC, Tsai CC, Huang WC. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β regulates the anti-inflammatory property of fluoxetine. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;14(2):150-6. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.06.015, PMID 22749848.

Beurel E, Grieco SF, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation actions and diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;148:114-31. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.016, PMID 25435019.

Babulal GM, Stout SH, Head D, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, Morris JC. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers predict driving decline: brief report. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(3):675-80. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170067, PMID 28453487.

Kamila P, Kar K, Chowdhury S, Chakraborty P, Dutta R, SS. Effect of neuroinflammation on the progression of Alzheimer’s disease and its significant ramifications for novel anti-inflammatory treatments. IBRO Neurosci Rep. 2025;18:771-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ibneur.2025.05.005, PMID 40510290.

Guo L, Wang Z, Li J, Cui L, Dong J, Meng X. MCC950 attenuates inflammation-mediated damage in canines with Staphylococcus pseudintermedius keratitis by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;108:108857. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108857, PMID 35597123.