Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 5, 2025, 315-319Original Article

PHARMACOKINETICS OF A NEWLY FORMULATED IBUPROFEN TABLET IN ARABIC HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS

DUAA JAAFAR JABER AL-TAMIMI1*, SABA ABDULHADI JABER2, HALAH TALAL SULAIMAN3

1College of Pharmacy, Al-Nisour University, Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, Baghdad, Iraq. 2,3Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq

*Corresponding author: Duaa Jaafar Jaber Al-tamimi; *Email: duaa.altamimi1@gmail.com

Received: 18 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 28 Jul 2025. Publication: 20 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate the pharmacokinetics (PKs) of a newly formulated immediate-release ibuprofen (IBU) 400 mg tablet administered to healthy Arabic volunteers.

Methods: This was a single-dose study conducted on healthy Arabic subjects under overnight fasting. Each subject received one 400 mg tablet of the newly formulated IBU. Blood samples were collected at pre-determined intervals for up to 12 h post-dose. Pharmacokinetic parameters including maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to reach maximum concentration (Tmax), area under the curve from time zero to last measurable concentration (AUC₀₋ₜ), area under the curve from time zero to infinity (AUC₀₋∞), elimination rate constant (Kₑ), elimination half-life (T 0.5), mean residence time (MRT), clearance/bioavailability (Cl/F), and volume of distribution/bioavailability (Vd/F) were calculated using non-compartmental analysis.

Results: The mean±SD pharmacokinetic parameters of IBU after a single 400 mg dose were as follows: Cmax = 26.1±4.7 µg/ml, Tmax = 1.98±0.56 h, AUC₀₋ₜ = 103.4±23.5 µg·h/ml, AUC₀₋∞ = 107.8±28.6 µg·h/ml, %AUCextra= 3.5±2.6, Kₑ = 0.310±0.047 h⁻¹, T 0.5 = 2.29±0.42 h, MRT = 4.17±0.84 h, Cl/F = 3.9±0.71 l/h, Vd/F = 12.6±2.3 l. The newly formulated IBU tablet was well tolerated by all participants with no significant adverse effects observed.

Conclusion: The present investigation introduced the PK parameters of a newly formulated IBU tablet administered to Arabic healthy individuals which were found to be comparable to the data presented in literature for other IBU tablets. Consequently, the new IBU formula can be introduced to the market as a safe and effective product.

Keywords: Ibuprofen tablet, Pharmacokinetics, Arabic men

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i5.55640 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Ibuprofen (IBU) was the first available over-the-counter (OTC) drug used and prescribed widely as a potent antipyretic, analgesic, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory. It is available on the market in different doses, dosage forms and routes of administration, including injection, suspension, capsule, chewable tablet, and sustained-release tablet, in addition to a wide dose range of 100, 200, 400, 600, and 800 mg of immediate-release tablets. As OTC, IBU is usually given every 4-6 h orally in doses of 200-400 mg (not more than 1200 mg daily). It is prescribed orally for inflammatory disease every 6-8 h in a dose range of 400-800 mg (not exceed 3200 mg daily), for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in 300, 400, 600, or 800 mg doses every 6-8 h (not more than 3200 mg daily) [1].

Ibuprofen (IBU) is rapidly and very well absorbed orally attaining its peak plasma levels within 1 to 2 h after extravascular intake. The terminal plasma elimination plasma half-life (t 0.5) of IBU is about 2 h [2-5]. Administration of IBU tablet directly after food causes a reduction in the rate but not the extent of the absorption from GIT [6-8]. In addition, other factors may also affect the absorption of IBU [9-13].

Due to differences in the PKs of drugs because of many reasons such as administration of drugs in different doses, dosage forms like solid and ophthalmic dosage forms, routes of administration, food intake, concomitant therapy, and among various populations; therefore, there are ongoing recent researches for studying drugs PKs, bioavailability, particularly for drugs which possess difficulties in measuring in plasma and clearly identifying it clinical outcomes [14-22]. Concerning IBU, it was found that the rate and extent of IBU absorption in the GIT from different formulations demonstrate significant differences in the onset, intensity and duration of pain reduction [23]. Hence, the current study was conducted to evaluate IBU PKs following the administration of a newly formulated IBU tablet in Arabic healthy men. This is the first study conducted in an Arabic population to calculate pharmacokinetics (PKs) by applying a newly developed formula, which is intended to be officially registered.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The study protocol was prepared according to the trial’s objectives and ICH guidelines for good clinical practice [24, 25] and the recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki [26]. As per the above-mentioned guidelines [24-26], the study protocol was ethically approved by the research ethics committee at the University of Baghdad under the approval number 442024G. The protocol described all details, including clinical, bioanalytical, and PKs. All the screened subjects were fully informed about all details of this clinical trial involving the objectives and any potential risks associated with their participation, in addition to their rights to withdraw at any time during the trial. All screened subjects were financially compensated. At the screening stage, the clinical investigator and the participant and two witnesses signed two original copies of the consent forms. Each participant was delivered his original copy of the informed consent, and the other copy of the informed consent was archived in the study source documents.

Inclusion criteria

Arabic healthy adult men who were willing to comply with all requirements of the protocol involving pre and post-study clinical examinations were chosen to be enrolled in this trial according to the following inclusion criteria: 1) ages between 18-50 y, 2) body mass index (BMI) range from18-30 kg/m2, 3) non-smoker or light smoker (<10 cigarettes per day), 4) no history of alcohol and drug abuse, 5) no involvements in any clinical trials such as PKs, bioavailability, 6) no recent surgical operation and/or blood donation for at least eight weeks prior this trial, and, 7) absence of acute infection within at least two weeks prior the study.

The screened subjects were considered healthy and eligible for participation based on the following inclusion criteria:

1. Personal interview with the participant to examine mental condition.

2. Complete physical and clinical investigations, including normal vital signs (blood pressure, temperature, and pulse), normal ECG, and no significant medical history or diseases such as gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, hepatic, renal, respiratory, renal, epilepsy, bleeding/coagulation disorders, severe anemia, and psychiatric problems.

3. Clinical laboratory investigations included normal biochemistry, hematology, negative (HIV, hepatitis B and C), negative drug abuse and alcohol abuse examinations, and normal routine urine analysis.

4. No history of hypersensitivity or allergy to ibuprofen (IBU) or any of its related compounds.

The exclusion criteria included the presence of any significant acute or chronic medical conditions, abnormal clinical or laboratory findings, history of alcohol or drug abuse, recent surgical operations or blood donation within eight weeks prior to the study, participation in other clinical trials within the past two months, and current use of any medication that might interfere with IBU metabolism.

Additionally, subjects with a BMI outside the range of 18–30 kg/m², heavy smokers (>10 cigarettes/day), and those unable to comply with the study protocol were also excluded.

Ibuprofen administration

All the participants attended the clinic before about 18 h of IBU administration to achieve clinical investigations, including vital signs, alcohol and drug abuse tests. After that, each eligible participant was given an identification number to be used during the entire clinical trial. Standard dinners were served 12 h pre-drug intake. The participants were confined in the clinic site during the entire interval of the study (30 h) in order to avoid any violation of the study protocol.

Ibuprofen 400 mg of a newly formulated tablet was administered to each participant with 240 ml water after an overnight fasting of 12 h. Immediately after drug administration, the clinical staff did a mouth check to ensure the drug intake by the participant. Water was not allowed before 2 h of IBU intake and, for 2 h after dosing (other than water given with the drug), after that water was permitted ad libitum. Standard lunches, snacks, and dinners were served to the participants at 4, 8, and 12 h of IBU administration, respectively. Sleeping during the first 4 h of drug intake was banned. The participants were asked to stay upright, sitting, standing, and moving in the clinic freely, but under complete observation and supervision of the clinical staff.

Blood sampling

Five ml venous blood samples were drawn from each participant via an indwelling cannula placed in the subject’s forearm antecubital vein. The cannula stayed until the end of the study period. Blood samples were drawn before drug administration (0 h), and then at 0.33, 0.67, 1.0, 1.33, 1.67, 2.0, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 6, 8, 10, and eventually at 12 h post-dosing. A total of 15 blood samples were drawn from each participant. The total blood volume obtained from each subject was 85 ml, including the blood samples collected at the screening phase, and the last blood sample to achieve the clinical laboratory tests. One ml of saline containing 0.5 IU heparin was immediately injected after each blood sample withdrawal to avoid closure of the cannula due to clotting. Besides, about 0.05 ml of blood was discarded from the cannula before each blood sample withdrawal to get rid of any residual blood in the cannula. The time for the actual blood sample drawn was recorded. Each blood sample was directly placed into a heparin tube, followed by centrifugation for 5 min at 4000 rpm to separate the plasma. The separated plasma samples were saved as two aliquots in two Eppendorf tubes and were frozen at-20±10 °C until the day of IBU analysis in plasma. All the tubes used for collecting blood and plasma samples were labelled according to a specific in-house coding/labelling system specifying the protocol number, subject identification number given in admission of the participant, and the number of the blood/plasma sample obtained. The quality assurance personal and the principal investigator only had access to the coding/labelling system applied in the study.

Ibuprofen analysis in plasma

A modified high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) method with spectrofluorometer detector was adopted from previous investigations [27-29] to cover the expected IBU plasma concentrations ranges from 0.1-100 µg/ml as shown in previous PK, bioavailability studies [28]. The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) of IBU in plasma was found to be 0.1µg/ml. The standard calibration curve was linear across the tested ranges of 0.1-100 µg/ml with a coefficient of variation (%CV) for intra-day and inter-day precision was lower than or equalled to 9%, and with accuracies within 5% of the nominal tested low, medium and high levels. For ibuprofen’s levels at the LLOQ, the intra-day and inter-day precision and accuracy were within 11 and 14%, respectively. The recovery of IBU was found to be 84% or higher. The determination coefficients (r2) were greater than 0.9991. The bioanalytical method development and validation were carried out according to FDA guidance [30]. Each analytical run contained all unknown authentic IBU plasma samples collected, in addition to the standard calibration curve and the quality control samples at low, medium and high levels of IBU. Moreover, ibuprofen’s plasma concentrations were not estimated by interpolation and/or extrapolation below the LLOQ or above the upper limit of quantitation (ULOQ) of the established standard calibration curve at concentrations ranges of 0.1-100 µg/ml plasma, as recommended by FDA guidelines [30].

Safety evaluation

The tolerability and safety of IBU were evaluated by interviewing each participant to register any unusual feelings such as pain, nausea, dizziness. Besides, the clinical investigator, together with the clinical crew, were found during the entire study period to observe and document any potential adverse events (AEs), adverse drug reactions (ADR), and serious adverse effects (SAE). The vital signs, including temperature, pulse and blood pressure, were recorded at about one hour before IBU administration, and then at 0.5, 1, 2, 6, 8, 10, and eventually at 12 h post-dosing, which is the time of participant’s discharge. Furthermore, the clinic was supplied with the necessary clinical facilities to handle any urgent cases beyond the clinic's capabilities.

As per the subject’s termination criteria stated in the study protocol, the clinical investigator terminate the participation of any subject during any time of the study according to the following criteria: 1) poor cooperation, bad compliance and/or violation of the participant from any clinical procedures of the protocol, 2) appearance of any illness which may threaten and jeopardize the participant’s health and well-being, 3) occurrence of clinically significant changes in baseline clinical laboratory test and/or vital signs of the participant.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

All primary and secondary PK parameters of IBU for each subject were calculated by non-compartmental analysis using Kinetica software. The following parameters were computed from the plasma concentrations versus time data of each subject, applying standard methods [31, 32]:

Cmax= maximum observed plasma concentration, Tmax = time to attain Cmax, AUC0-t = area under plasma concentration-time curve measured by Trapezoidal rule from zero time (t0) and up to the time of last blood sample withdrawal (tlast) at 12 h post-dosing, AUCt-∞ = extrapolated area under plasma concentration-time curve from tlast to infinity was computed from Clast/λz. Clast = last ibuprofen’s plasma concentration which meets or above the LLOQ. Kelimination (λz) = terminal elimination rate constant determined from the log-linear regression equation (log y=log a-bx) by least-square fitness of more than 3 subsequent concentrations in the terminal phase of the log-concentration versus time graph of each subject, Thalf = terminal elimination half-life was computed from 0.693/λz, AUC0-∞ = area under plasma concentration-time curve from t0 to infinity measured from [AUC0-t+AUCt-∞], AUCextrapolated = extrapolated area under plasma concentration-time curve from tlast to infinity was estimated from [AUCt-∞/AUC0-∞], MRT = mean residence time was derived from [AUMC/AUC], AUMC is the area under moment curve, Cl/F = total body clearance divided by bioavailability (F) was calculated from IBU dose given (400 mg) divided by the computed AUC0-∞ of each subject, Vd/F = apparent volume of distribution was calculated from [Cl/Kelimination] of each individual. Descriptive statistics of all PK parameters were presented [33]. The mean±SD of ibuprofen’s plasma concentrations-time data were plotted by Excel in rectilinear and semi-log graphs.

RESULTS

Participants

Table 1 presents the characteristics of all participants who completed the current trial.

Table 1: Characteristics of subjects completed the study

| Characteristics | Mean±SD | (%CV) | Range |

| Age (y)* | 28.0±8.2 | 29.3 | 19-43 |

| Height (m)* | 1.74±0.06 | 3.5 | 1.60-1.86 |

| Body weight (kg)* | 71.1±8.77 | 12.0 | 58-89 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 24.1±2.32 | 9.6 | 18.7-28.4 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg)* | 119.1±6.5 | 5.4 | 110-130 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)* | 76.1±4.6 | 6.1 | 70-80 |

| Pulse (beat per minute)* | 66.5±5.0 | 7.5 | 60-77 |

| Temperature (°C)* | 36.9±0.18 | 0.005 | 36.6-37.1 |

*n (number of subjects=28).

Tolerability and safety

The new IBU formula was well tolerated by all participants. Clinically meaningful changes in the clinical baseline data, including vital signs and laboratory tests, were not reported during the investigation, and all participants were discharged from the study without any significant changes in their safety profiles.

Table 2 shows the safety profile after administration of the new investigated IBU formula.

Table 2: Adverse events (AE) reported following the administration of the newly investigated ibuprofen formula (n=28)

| Subject No. | AE | Intensity | Recovery | Medical action |

| 02 | Headache | Mild | Complete | No/Audit only |

| 05 | Abdominal pain | Mild | Complete | No/Audit only |

| 06 | Nausea | Mild | Complete | No/Audit only |

| 12 | Dizziness | Mild | Complete | No/Audit only |

| 15 | Nausea | Mild | Complete | No/Audit only |

| 22 | Abdominal pain | Mild | Complete | No/Audit only |

| 25 | Headache | Mild | Complete | No/Audit only |

Bioanalytical results

The modified bioanalytical method applied in this trial [27-29] was found to be suitable and successful in demonstrating the entire PKs behaviours of IBU after a single dose of 400 mg tablet.

Plasma concentrations of ibuprofen

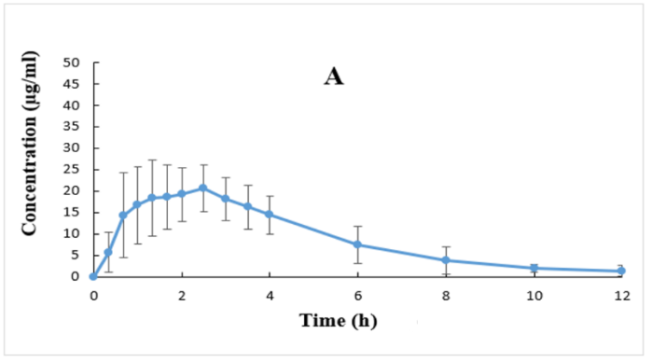

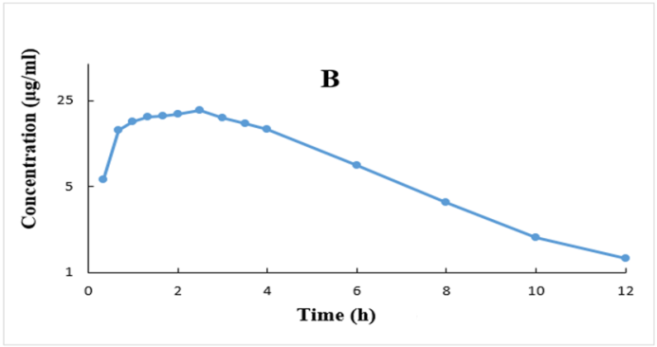

Ibuprofen’s plasma concentrations versus time profiles (mean±SD) are plotted in rectilinear and semilog graphs as depicted in fig. 1.

Pharmacokinetic data

Table 3 introduces the descriptive statistics of all the primary and secondary PK parameters.

Table 4 show the PKs of IBU tablet administered to different populations.

Fig. 1: Plasma concentrations (Mean±SD, (n=28)) versus time profiles after ibuprofen 400 mg tablet plotted in rectilinear (A) and semilog

Table 3: Pharmacokinetic parameters of ibuprofen after a single dose of 400 mg tablets (n=28)

| Stat | Cmax (μg/ml) |

Tmax (h) |

AUC0-t (μg. h/ml) |

AUC0-∞ (μg. h/ml) |

% AUCextra |

λz (h-1) |

T0.5 (h) |

MRT (h) |

Cl/F (l/h) |

Vd/F (l) |

| Mean* | 26.1 | 1.98 | 103.4 | 107.8 | 3.5 | 0.310 | 2.29 | 4.17 | 3.9 | 12.6 |

| ±SD* | 4.7 | 0.56 | 23.5 | 28.6 | 2.6 | 0.047 | 0.42 | 0.84 | 0.7 | 2.3 |

| %CV* | 18 | 34 | 28 | 27 | 74 | 15 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 18 |

| Min* | 17.4 | 1.0 | 73.6 | 75.5 | 1.7 | 0.196 | 1.72 | 3.26 | 2.0 | 9.3 |

| Max* | 33.4 | 3.0 | 167.3 | 203.0 | 13.2 | 0.402 | 3.53 | 6.85 | 5.2 | 18.7 |

*n (number of subjects=28).

Table 4: Average pharmacokinetic parameters of IBU obtained from previous studies in comparison to the current one

Year |

Population |

Dosage form |

Cmax (μg/ml) |

AUC0–∞ (μg. h/ml) |

Tmax (h) |

T 0.5 (h) |

Reference |

2021 |

Jordan |

Tablet |

43.6 |

150.7 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

[2] |

2017 |

Korea |

Tablet |

60.4 |

162 |

1.25 |

2.3 |

[3] |

2001 |

UK and Germany |

Tablet |

31.98 |

109.3 |

1.3 |

2.0 |

[5] |

2015 |

UK |

Tablet |

30.4 |

* |

1.34 |

* |

[6] |

2019 |

Germany |

Tablet |

31.8 |

126 |

1.88 |

2.13 |

[8] |

2025 |

Arabic |

Tablet |

26.1 |

107.8 |

1.98 |

2.3 |

Current |

*Not studied

DISCUSSION

Thirty-three subjects were screened to account for any subject’s withdrawal and/or dropout, which is anticipated in any clinical trial. As per the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the study protocol, three subjects were not eligible to be involved, and two other subjects withdrew because of personal reasons. The remaining 28 participants completed the whole study.

Table 2 shows the safety profile after administration of the new investigated IBU formula, which indicates that all the registered adverse effects are mostly mild and appeared in 7 subjects out of 28 participants completed the study. The most common AEs included headache, nausea, abdominal pain, and dizziness. These events required no treatment other than monitoring. Besides all of these registered adverse effects recovered before subjects discharged from the study.

The method validation was accurate, specific, selective, sensitive, and precise based on the current recommended FDA bioanalytical method validation guidance [30]. Moreover, ibuprofen’s plasma concentration ranges from 0.1-100 µg/ml applied in this investigation were quite enough for covering the ranges of the resulted ibuprofen’s plasma levels, as illustrated in fig. 1.

The drug was detected (above LLOQ of 0.1 µg/ml) in all plasma samples and all participants at the first blood sample withdrawal (i. e., 0.33 h after drug administration) and attained its maximum plasma concentrations (Tmax) after about 2 h (range 1-3 h) after drug intake (fig. 1 and table 3). Ibuprofen’s plasma levels declined mono-exponentially with relatively rapid elimination profiles from the body, as shown in fig. 1B. The present findings are in good agreement with other investigations [2-8].

The data presented in table 3 demonstrated low inter-subject variability (as shown by low %CV) for all parameters. Moreover, the estimated % extrapolated AUC is low, which indicate that IBU LLOQ of 0.1 µg/ml used in this study, and blood sampling for 12 h after IBU dosing were very enough for identifying the absorption and disposition of the drug, and consequently reliable calculations of ibuprofen PK parameters were achieved (fig. 1 and table 3).

Table 4 shows the pharmacokinetics of IBU tablet administered to different populations. Concerning Cmax vales: table 4 indicates that the study conducted in England and Germany indicates that the average Cmax values are almost similar and comparable to the current Cmax values. However, the study conducted in Jordan and Korea gave a higher Cmax value.

Regarding Tmax and T 0.5 values: it is apparent that there are no clear differences between the Tmax values obtained from different populations.

Concerning the total AUC: it is obvious that the study conducted in Uk and Germany gave almost comparable and similar results to the current study. However, the AUC obtained from study conducted in Jordan and Korea show clear differences to each other and to the current investigation.

Accordingly, it seems that IBU tablet formulation tested in the current investigation show different rate and extent of absorption since Cmax reflect rate and extent of drug absorption, while AUC reflects the extent of absorption. These differences could be due to formulation differences.

The inter-subject variability in IBU pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax, AUC) can be justified through pharmaceutical and/or physiological reasons.

Pharmaceutical factors include formulation characteristics such as excipient composition differences that directly impacts dissolution kinetics, particularly for BCS Class II drugs like IBU. In addition, population metabolic polymorphisms and physiological factors could also affect PKs parameters.

CONCLUSION

The present investigation introduced the PK parameters of a newly formulated IBU table administered to Arabic healthy individuals, which was found to be comparable to the data presented in literature for IBU tablets. Consequently, the new IBU formula can be introduced to the market as a safe, effective and affordable national surrogate to the brand product.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to acknowledge the clinical team, the analytical staff, and all the subjects who participated in the study.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was carried out following the updated ICH guidelines for good clinical practice (GCP) and provisions of the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects stated in the latest version of the declaration of Helsinki.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, D. J. A.-T.; methodology, D. J. A.-T.; software, D. J. A.-T., S. A. J. and H. T. S.; data analysis, D. J. A.-T.; resources, D. J. A.-T., S. A. J. and H. T. S; writing—original draft preparation, D. J. A.-T., writing—review and editing, S. A. J. and H. T. S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Rainsford KD. Ibuprofen: pharmacology, efficacy and safety. Inflammopharmacology. 2009;17(6):275-342. doi: 10.1007/s10787-009-0016-x, PMID 19949916.

Al-Dalaen SMI, Hamad AW, AL-Hujran TA, Al-Btoush HA, Al-Halaseh L, Magharbeh MK. Bioavailability and bioequivalence of two oral single dose of ibuprofen 400 mg to healthy volunteers. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2021;14(1):435-44. doi: 10.13005/bpj/2143.

Dongseong S, Sook JL, Yu-Mi H, Young Sim C, Jae Won K, Se Rin P. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation according to absorption differences in three formulations of ibuprofen. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2017;4(11):135-41.

Mendes GD, Mendes FD, Domingues CC, de Oliveira RA, da Silva MA, Chen LS. Comparative bioavailability of three ibuprofen formulations in healthy human volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008 June;46(6):309-18. doi: 10.5414/cpp46309, PMID 18541128.

Schettler T, Paris S, Pellett M, Kidner S, Wilkinson D. Comparative pharmacokinetics of two fast-dissolving oral ibuprofen formulations and a regular-release ibuprofen tablet in healthy volunteers. Clin Drug Investig. 2001;21(1):73-8. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200121010-00010.

Moore RA, Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Straube S. Effects of food on pharmacokinetics of immediate release oral formulations of aspirin, dipyrone, paracetamol and NSAIDs-a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(3):381-8. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12628, PMID 25784216.

Heintze K, Fuchs W. Effects of food on pharmacokinetics of immediate release oral formulations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(5):1239. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12712, PMID 26140311.

Weiser T, Schepers C, Mück T, Lange R. Pharmacokinetic properties of ibuprofen (IBU) from the fixed-dose combination IBU/caffeine (400/100 mg; FDC) in comparison with 400 mg IBU as acid or lysinate under fasted and fed conditions-data from 2 single-center, single-dose, randomized crossover studies in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2019 August;8(6):742-53. doi: 10.1002/cpdd.672, PMID 30897305.

Al-Tamimi DJ, Hussien AA. Formulation and characterization of self-microemulsifying drug delivery system of tacrolimus. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2021;30(1):91-100. doi: 10.31351/vol30iss1pp91-100.

Jadhav SV, Nikam AS, Gunjal SB. To study the regulatory guidelines for API of ibuprofen: a review. Asian J Pharm Res Dev. 2024;12(1):98-106. doi: 10.22270/ajprd.v12i1.1356.

Das Purkayastha HD, Nath B. Formulation and evaluation of oral fast disintegrating tablet of ibuprofen using two super disintegrants. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2017;9(4):92-5. doi: 10.22159/20966.

Devi JR, Das B. Preparation and evaluation of ibuprofen effervescent granules. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019 Aug 7;12(8):52-5.

Tiwari A, Gabhe SY, Mahadik KR. Comparative study on the pharmacokinetics of ibuprofen alone or in combination with piperine and its synthetic derivatives as potential bioenhancer. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2020;12(1):363-71.

Alani ME, Al-Tamimi DJ, Al-Mahroos MI. Ammoo1 AM, al-Tamim MJ, Ibraheem JJ. Bioequivalence study of a newly developed azithromycin suspension versus Zithromax® following a single dose to healthy fasting adult subjects. IJDD. 2021;11(1):159-65.

Al-Tamimi DJ, Alani ME. Ammoo AM. Ibraheem JJ. Linear pharmacokinetics of doxazosin in healthy subjects. Int J Res Pharm Sci. 2020;11(1):1031-9.

Jabbar EG, Al-Tamimi DJ, Al-Mahroos MI, Al-Tamimi ZJ, Ibraheem JJ. Pharmacokinetics and bioequivalence study of two formulations of cefixime Suspension . J Adv Pharm Educ Res. 2021;11(1):170-7. doi: 10.51847/LstEumAkic.

Al-Mahroos MI, Al-Tamimi DJ, Al-Tamimi ZJ, Ibraheem JJ. Clinical pharmacokinetics and bioavailability study between generic and branded fluconazole capsules. J Adv Pharm Educ Res. 2021;11(1):161-9. doi: 10.51847/UePrHyehg4.

Ammoo AM, Al-Tamimi DJ, Al-Mahroos MI, Al-Tamimi MJ, Ibraheem JJ. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole tablets administered to healthy volunteers. J Adv Pharm Edu Res (JAPER). 2021;11(2):93.

Al-Tamimi DJ, Maraie NK, Arafat T. Comparative bioavailability (bioequivalence) study for fixed dose combination tablet containing amlodipine, valsartan and hydrochlorothiazide using a newly developed HPLC-MS/MS method. Int J Pharm Sci. 2016;8(7):296-305.

Al-Tamimi D, Al-Kinani K, Taher S, Hussein A. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of fluoxetine in healthy male adult volunteers. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2023;31Suppl:153-61. doi: 10.31351/vol31issSuppl.pp153-161.

Jaber Al-Tamimi DJJ, Abbas Al-Mahroos MI, Jaber Al-Tamimi MJ, Jaber Ibraheem J. Pharmacokinetic comparison and bioequivalence evaluation between a newly formulated generic and the brand cefuroxime axetil tablets in healthy male adult fasting subjects. Res J Pharm Technol. 2022;15(5):2184-92. doi: 10.52711/0974-360X.2022.00363.

Al-Tamimi DJJ. Review article ophthalmic dosage forms. Kerbala J Pharm Sci. 2020;18:81-202.

Moore AR, Derry S, Straube S, Ireson Paine J, Wiffen PJ. Faster, higher, stronger? Evidence for formulation and efficacy for ibuprofen in acute pain. Pain. 2014;155(1):14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.08.013, PMID 23969325.

International council for harmonization of technical requirements for pharmaceuticals for human use (ICH), ICH harmonized guidance: guidance for good. Clin Pract. 2016 Nov;E6:(R2).

E6 (R2) Good Clinical Practice: Integrated Addendum to ICH E6(R1). Guidance for industry. Center for drug evaluation and research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), March: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2018.

WMA Declaration of Helsinki, ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, 64th WMA general assembly. Fortaleza, Brazil; 2013.

Farrar H, Letzig L, Gill M. Validation of a liquid chromatographic method for the determination of ibuprofen in human plasma. Journal of Chromatography B. 2002;780(2):341-8. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00543-3.

Canaparo R, Muntoni E, Zara GP, Della Pepa C, Berno E, Costa MS. Determination of ibuprofen in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography: validation and application in pharmacokinetic study. Biomed Chromatogr. 2000;14(4):219-26. doi: 10.1002/1099-0801(200006)14:4<219::AID-BMC969>3.0.CO;2-Z, PMID 10861732.

Ganesan M, Rauthan S, Pandey Y, Tripathi P. Determination of ibuprofen in human plasma with minimal sample pretreatment. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2010;1(5):120-7. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.1(5).120-27.

Bioanalytical method validation guidance for industry. United States department of health and human services, food and drug administration, center for drug evaluation and research (CDER), Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM); May 2018.

Leon S, Andrew BC. Murray D. Shargel and Yu’s applied biopharmaceutics and pharmacokinetics. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education/Medical; 2021.

Hartmut D, Stephan S. Rowland and Tozer’s clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: concepts and applications. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2019.

Schober P, Vetter TR. Nonparametric statistical methods in medical research. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(6):1862-3. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005101.