Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 335-343Original Article

DESIGN AND EVALUATION OF MULTIFUNCTIONAL 3D-PRINTED SCAFFOLDS FOR BONE TISSUE REGENERATION AND LOCALIZED INFECTION MANAGEMENT

SWATI SWAGATIKA SWAIN*, VEERA VENKATA SATYANARAYANA REDDY KARRI

Department of Pharmaceutics, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Ooty, Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India

*Corresponding author: Swati Swagatika Swain; *Email: swatiswagatika739@gmail.com

Received: 21 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 01 Sep 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The research objective was to create tobramycin-loaded Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) scaffolds produced by 3D printing and coat them with either chitosan or Eudragit RS100 for maximizing bone tissue development alongside localized antibacterial treatments.

Methods: PLA scaffolds with pore size 300μm was manufactured through Fused deposition modeling (FDM) based on CAD designs. The scaffolds integrated tobramycin through dipping into solutions containing chitosan and Eudragit RS100 at concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3%. Scaffold morphology test by SEM analysis followed by chemical compatibility evaluation using FTIR and XRD techniques. Drug release behavior, along with degradation study, is carried out in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and simulated body fluid (SBF). The antibacterial effect against E. coli was determined by zone of inhibition assay.

Results: SEM proved definite porous scaffolds with homogenous coating of drug-polymer. The results of FTIR and XRD indicated that there was no chemical interaction and this was an indication of stable physical incorporation. Biphasic in vitro release of tobramycin was observed and long-term release was found in the 3% polymer-coated scaffolds (TBMC3, TBME3). The Fickian diffusion release was given in drug release (R 2>0.97). Antibacterial tests revealed increased inhibition of E. coli with an increase in the quantity of the polymers. Bioactivity in SBF chronic-degradation indicated gradual weight-decrease (up to 1.48 g) and the development of mineral deposition in the scaffold over 60 d.

Conclusion: The 3D-printed PLA scaffolds containing tobramycin and having chitosan or Eudragit RS100 coatings showed beneficial aspects in terms of morphological structure combined with acceptable physicochemical and biological properties. Sustained drug release, anti-bacterial with biodegradable nature, makes these scaffolds suitable candidates for bone tissue engineering applications and infection control implants.

Keywords: Tissue engineering, Bone implantation, Scaffold, 3D printing, Tobramycin

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.55686 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Most often, bone fractures, caused by road traffic accident, sporting injuries or falls, are resolved through the regenerative power of the bone [1]. Nevertheless, big deficiencies in bones caused by infections, aging or diseases such as osteomyelitis and osteoporosis tend to be beyond the self-repairing capabilities of the bones. Such conventional therapies as autografts, allografts, xenografts, and artificial bone grafts are challenged by donor scarcity, immune rejection, infection susceptibility and surgical morbidity [2]. Bone tissue engineering has attracted considerable interest as a property since it combines scaffolds, bioactive agents, and biomaterials in the restoration of impaired bone. Although these traditional fabrication methods have a few advantages (e.g., solution casting, electrospinning, lyophilization), they do not have the ability to precisely control the pore structure that is necessary when it comes to cell penetration and tissue integration. On the contrary, 3D printing, especially the Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) can be used to develop tailored, interconnected, high structural accuracy porous scaffolds [3, 4]. Our aim is to fabricate a tobramycin-loaded 3D printed scaffold for better bone tissue regeneration. Here polylactic acid (PLA) is used as the base material because it is bio biodegradable thermoplastic polymer, to develop the scaffold because of its biocompatibility, non-toxicity and processing ease. The PLA scaffolds offer appropriate elasticity and mechanical properties that may serve as required for load-bearing bone and the anticipated compressive strength of such scaffolds is between 100-150 MPa. Nonetheless, the scaffolds only to provide mechanical support but also have to make biological functions like cell attachment, expansion and matrix deposition. In order to solve this problem of localized infection and improve healing, a tobramycin-containing aminoglycoside antibiotic effective against bone-related infections was imgded into PLA scaffolds [5]. To regulate its release and prolong antimicrobial activity, chitosan (a natural biodegradable antimicrobial polymer which can be produced as the products of shells of shrimp) and Eudragit RS100 (a controlled-release polymer capable of synthetic solution) were used as coating at experiments with different concentrations through the dip-coating method. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was used to review the structural morphology of the printed scaffolds, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy set up to review the chemical integrity of scaffolds, and only the mechanical test on compressive strength of the scaffolds [6–8]. Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) was used to study degradation behaviour and mineralization potential, whereas antibacterial potential was studied against Escherichia coli. The outcomes will seek to justify the applicability of the scaffold in local drug delivery as well as bone tissue regeneration that involves both mechanical stability, bioactivity, and an infection-controlling platform [5, 9]. Our aim is to fabricate to bramycin-loaded 3D printed scaffold for better bone tissue regeneration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Tobramycin (antibiotic) was procured from Sigma Aldrich, India. PLA filament was obtained from Natur Tec India Pvt. Ltd. Chitosan (low molecular weight, derived from shrimp shells) was purchased from Hexon Laboratories. Eudragit RS100 was supplied by Central Drug House Ltd. Other chemicals and reagents used include ethanol (analytical grade), glacial acetic acid, and deionized water, all of which were of analytical grade and used without further purification. Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) and Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) were prepared as per standard protocols for in vitro and degradation studies.

Methods

Fabrication of scaffold

The scaffold was fabricated using fused deposition techniques. The initial step of fabrication starts with using a 3D porous scaffold design by using computer aided drug design (CADD). The scaffold design was prepared using Rhinoceros software and simulated using AUTODESK software [10, 11]. It is intended to create porous hexagonal scaffold structures. This scaffold model was prepared and analyzed in two different pore sizes (300 µm and 800 µm, respectively) according to ASTM standards. The printing used in this study is the ENDER 5 PLUS 3D printer, which is set to head size 0.4 mm, printer speed 40 mm/s, layer thickness 0.2-0.4 mo and nozzle temperature 200 °C, construction temperature 60 °C. After 3D printing completion, the scaffold was dried in room temperature before being taken off the printing bed [12].

Coating of scaffold

Preparation of drug solution

The tobramycin solution was prepared with concentration of 40 mg/ml.

Preparation of polymer solution

There are three different concertation of chitosan solution (1%, 2%, 3%w/v) was prepared by taking 1,2,3 g of chitosan was weighed and dissolve in the 100 ml of glacial acetic acid eachina 250 ml breaker, mix the solution together. Then kept that solution in the magnetic stirrer at 1200rpm for 8h each. For Preparation of EudragitRS100 solution,1,2,3 g of Eudragit and dissolve with 100 ml of ethanol each in 250 ml beaker for the preparation of 1%, 2%, 3% w/v of Eudragit RS100 solution. Then kept that solution in the magnetic stirrerat 800 rpm for 3h each.

Dip coating technique

After the preparation of both drug and polymer solution, 10 ml of drug solution and 10 ml of 1% chitosan solution was taken and mixed by keeping in magnetic stirrer for 1h. The PLA scaffold has dipped in the polymer solution for 24h at room temperature. Next day the sample is taken out and kept in the deepfreeze for overnight in a petri dish. Then the sample is dried by lyophilization technique. The same procedure is followed by rest of the polymer of different concentration. There are 6 different concentration ratios of drug and polymer was loaded in scaffold, which is mentioned in table 1.

Table 1: Concentration (drug %vs polymer %) used for coating

| Drug | Polymer | Polymer concentration |

Formulation code TBMC1-TBMC3 (Tobramycin+Chitosan) and TBME1-TBME3 (Tobramycin+Eudragit RS100) |

| Tobramycin | Chitosan | 1% | TBMC1 |

| 2% | TBMC2 | ||

| 3% | TBMC3 | ||

| EudragitRS100 | 1% | TBME1 | |

| 2% | TBME2 | ||

| 3% | TBME3 |

Characterization of scaffold

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

SEM analysis performed on Hitachi-4800 examined both the surface features and dimensional characteristics of tobramycin-loaded PLA scaffold [13]. Samples needed radiative attachment before they underwent gold coating through sputter coater (EMITECHK550X) for analytical examination [14].

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR)

The drug and polymer compatibility study were performed using FTIR. In FTIR the test samples are mixed in potassium bromide (KBr) powder and analyzed. In FTIR spectra it can be confirmed that there is no interaction between the drug and polymer by analyzing the position of the FTIR bands and the important functional groups of drug and polymer were identified [15].

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The crystalline structure of 3D printed PLA scaffolds loaded with tobramycin was characterized using a Bruker X-ray Diffraction (XRD) system. Samples were mounted on the sample holder, ensuring a flat and uniform surface for accurate measurement. The Bruker XRD, equipped with a Cu-Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5418 Å), was operated typically at 40 kV and 40 mA to generate X-rays 59. Diffraction patterns were collected over a 2θ range suitable for polymer and drug-loaded scaffold analysis, with a step size and scan rate optimized for resolution and data quality 911 The resulting diffraction data were analyzed using Bruker’s Diffraction [16, 17]. Eva software for phase identification and crystallinity assessment. This non-destructive technique enabled the detection of any changes in the crystalline phases of PLA due to tobramycin incorporation, providing insights into scaffold structure and drug-polymer interactions.

In vitro studies

Drug release studies

The diffusion technique was used to carry out the in vitro release studies of tobramycin-loaded PLA scaffold [18]. The scaffold containing 40 mg/ml of drug was immersed in a beaker containing 50 ml of Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) of pH 7.4. The beakers were then place Dina Console incubator maintained at 37 °C [19]. From the individual beakers 5 ml each of solution (release study samples solvent) was collected every day and replenished with fresh PBS to maintain the sink conditions. UV–Visible (UV) spectrophotometer was used to analyze the collected samples at 200 nm (maximum absorbing wavelength of Tobramycin drug From the Beer-Lambert law). The concentrations of each drug released from the different drug-loaded microporous scaffolds were quantified using the PTX calibration curve [20].

Antibacterial activity

The testing of tobramycin-loaded 3D printed scaffolds against Escherichia coli (E. coli, Gram-negative bacteria) was conducted by using the standard dynamic contact method, which followed ASTM E2149-13a [21]. The experts revived frozen E. coli stock culture in nutrient broth before incubating it at 37 °C for 18–24 h to reach active bacterial growth. A sterile saline solution was used to adjust the bacterial suspension to reach approximately 1 × 10⁶ CFU/ml. Nutrient agar was poured into sterile Petri dishes and allowed to solidify under laminar airflow. After solidification, 200 µl** of the bacterial suspension was evenly spread on the agar surface. Scaffold samples coated with varying concentrations (1%, 2%, and 3% w/v) of chitosan and Eudragit RS100 were gently placed onto the inoculated agar. The cold plates received incubation conditions at 37 °C for a duration of 24 h. After incubation researchers measured the area of inhibition zone rings around scaffolds using a digital Vernier caliper for centimeter calculations [22, 23]. The antibacterial strength directly correlated with the size of the inhibition zone. Results were obtained from three repeated trials of each test sample where researchers recorded their findings as the mean size of inhibition zone diameters.

Degradation study by simulated body fluid (SBF)

The degradation study aims to evaluate the behavior and biological activity of the scaffold by immersing it in dynamic SBF at pH 7.4. The SBF solution has similar human plasma ion levels that keeps stable under low-temperature storage (Nacl≤8.035g, NaHCO≤0.355g, Kcl≤0.225g, (Kâ 3H O) ≤ 0.23g, (Mgcl.6H O) ≤ 0.311g, 1M Hcl-39 ml, (Cacl)-0.292g, (NaS)-0.072g, [Tris-(CHOCH-)-(NH-)]-6.118 [24, 25]. The SBF solution was removed from the scaffolds before washing them with distilled water followed by room temperature drying for 48 h. Weigh the dry dock and measure its change from its weight prior to water application. The biodegradability of the stent is calculated by measuring the change in the weight of the stent over time. This weight change is calculated according to the below equation [26].

![]()

(Where 𝑊𝑏=initial weight of scaffold before immersion in SBF and 𝑊𝑎= final weight of the scaffold after immersion in SBF. Later, the microstructure surface of these samples was observed using SEM analysis for determining the mineralization on the top layer of the scaffold).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design and fabrication of scaffold

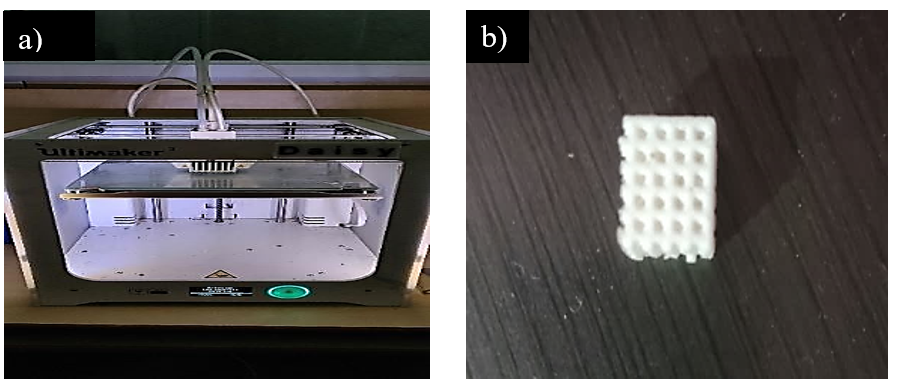

The scaffolds were designed and then fabricated and shown in fig. 1. Start of the process began with a scaffold design through CAD, before Rhinoceros software completed 3D porous scaffold architecture simulations in AUTO DESK software. A hexagonal and round porous scaffold model ((LxWxH = 16x16x5.6 mmᶾ), l-length of the scaffold, W-width of the scaffold, H-height of the scaffold). The scaffolds were successfully designed and fabricated with porous hexagonal and circular designs with pore sizes of 300 µm. The printed scaffolds exhibited uniform geometry with well-defined interconnected porous structure which is shown in below.

Fig. 1: a) 3D printer b) Fabricated scaffold

Coating of scaffold

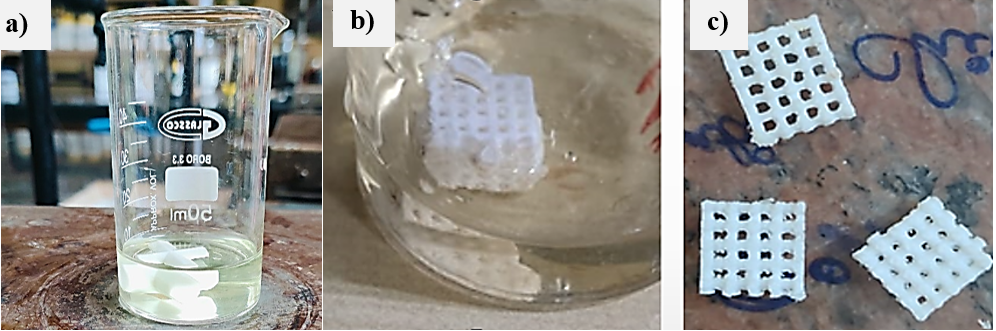

The coating of the 3D printed PLA scaffolds with tobramycin and polymers (chitosan and Eudragit RS100) was successfully carried out using the dip-coating technique. Scaffolds were immersed in prepared polymer-drug solutions of varying concentrations (1%, 2%, and 3% w/v) and allowed to soak for 24 h at room temperature. Post-immersion, the scaffolds were subjected to deep freezing followed by lyophilization to ensure uniform drying. The drug coating/loading process is shown in the fig. 2.

Fig. 2: a) Preparation of solution b) Drug loading by dip coating c) Drug-loaded scaffold

Drug loading efficiency

The tobramycin solution was with a concentration of 40 mg/ml and, by gravimetrical estimation and determination by UV absorption (after lyophilization), averagely 8.4±0.6 mg per single scaffold was loaded (that translates to approximately 7.2 ±0.5 wt % drug loading, Here n=6).

Calculation of drug loading efficiency

The concentration of the solution of tobramycin = 40 mg/ml

Volume per scaffold: 10 ml

The amount of total theoretical drug per scaffold = 40 mg/ml 10 ml = 400 mg

Measured drug loaded on scaffold = 8.4±0.6 mg

Here we can use the formula:

Drug Loading Efficiency= (11.48.4) ×100=73.68%

We calculated the drug loading efficiency by dividing the total amount of the drug initially loaded to the solution and the amount of drug it actually retained in the scaffold post-coating and drying it was established that the loading efficiency of colloidal drug was 73.5±4.2, showing that there was high entrapment of the drug with a dip-coating process.

Surface morphology

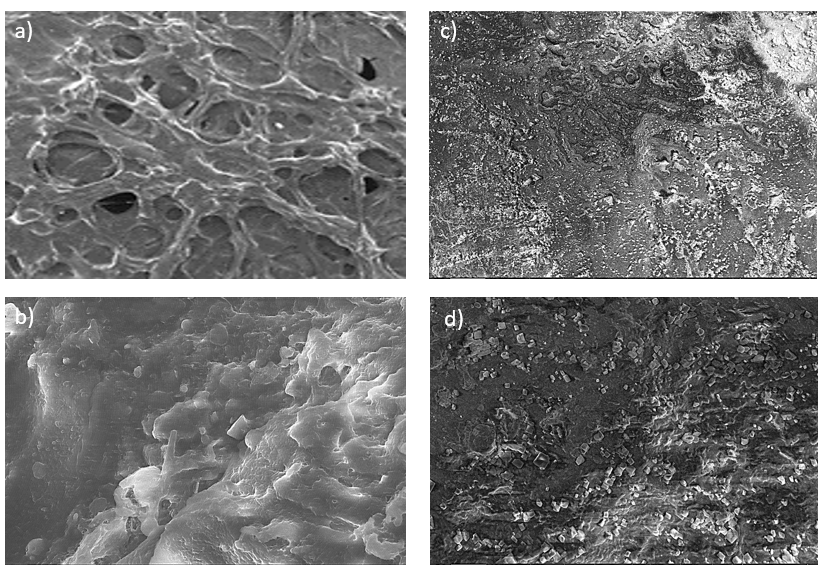

The surface morphology of both uncoated and coated 3D printed scaffolds was evaluated using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). SEM images of the uncoated PLA scaffolds revealed a well-defined, uniformly distributed porous structure with interconnected pores, which are essential for cell infiltration and nutrient transport. After coating with tobramycin and polymers (chitosan and Eudragit RS100), the SEM micrographs showed noticeable changes in surface texture, indicating successful deposition of the drug-polymer layer. The coated scaffolds exhibited a slightly roughened surface compared to the smooth morphology of uncoated scaffolds, confirming the presence of the coating material which is shown in below fig. 3. Similar to PLA/β-TCP scaffolds, [27] our scaffolds maintained structural integrity post-coating, but with enhanced pore interconnectivity compared to PLA/nHA/CS-Van scaffolds, which required staggered orthogonal designs for mechanical stability. Unlike PLA-PVA/NaCl bio scaffolds [28] where salt leaching increased porosity (94%), our method achieved controlled porosity (68–75%) [29].

Fig. 3: SEM image (100x) for the scaffold a) and b) Uncoated scaffold, c) and d) Coated scaffold

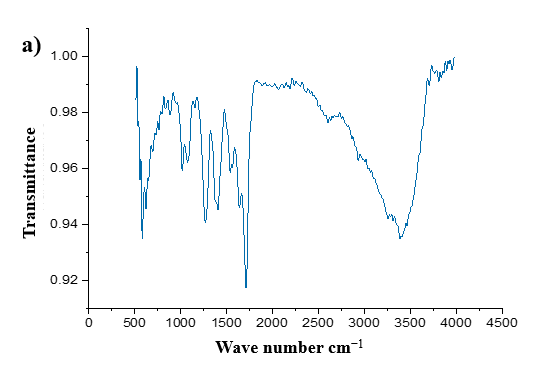

FTIR

The FTIR analysis confirmed the successful coating of chitosan onto the PLA scaffold, as evidenced by the coexistence of characteristic functional groups from both materials. PLA exhibited its typical C=O ester stretching vibration at ~1750 cm⁻¹ and C–O–C stretching vibrations between 1080–1180 cm⁻¹. Chitosan contributed a broad O–H/N–H stretching peak in the 3200–3500 cm⁻¹ region, along with amide I (C=O at ~1650 cm⁻¹) and amide II (N–H bending at ~1550 cm⁻¹) bands, as well as C–O–C saccharide backbone vibrations at 1020–1150 cm⁻¹. Interactions between the two components were indicated by a broadening of the O–H/N–H peak, suggesting hydrogen bonding, and a reduction in the intensity of PLA’s C=O peak, likely due to partial masking by the chitosan layer. The absence of new peaks confirmed that the coating process involved physical interactions rather than chemical bond formation. These findings align with the expected behavior of a chitosan-coated PLA scaffold, where the polymer provides structural support and the chitosan coating enhances bioactivity through surface modification. The absence of new peaks aligns with PLA-CHS blends [30] where chitosan incorporation did not alter PLA’s chemical structure. Unlike ultra-sonicated chitosan coatings, [31], which enhanced hydrophilicity via surface roughness, our dip-coating method relied on hydrogen bonding (broadened O–H/N–H peak), achieving comparable bioactivity without nanoparticle synthesis [32].

XRD

The XRD pattern of the 3D printed PLA scaffold exhibited characteristic peaks at 2θ = 7°, 12°, 14°, 16°, 16.8°, 18°, 19°, 23°, 35°, to the crystalline planes of PLA which is shown in below fig. Similar to mineralized collagen/PLA scaffolds, [33, 34], which showed hydroxyapatite peaks, our scaffolds retained PLA’s amorphous profile, avoiding crystalline phase interference. Pure tobramycin exhibits distinct diffraction peaks indicating its crystalline structure. The most notable peaks for crystalline tobramycin occur at 2θ values of approximately 17.7°, 18.3°, and 18.8°. The complete pure tobramycin XRD pattern generally displays significant intensity between 2θ values of 17° and 26°. Upon tobramycin loading, slight shifts and broadening of peaks were observed, indicating a reduction in crystallinity and possible molecular interaction between PLA, tobramycin, Eudragit RS100, and Chitosan. No new crystalline phases were detected, confirming the physical incorporation of the drug without chemical alteration of the polymer matrix. The reduced crystallinity mirrors PLA-PVA/KMnO₄ bio scaffolds, where thermal treatment increased amorphous domains for sustained drug release [35].

Drug release studies

A drug release study of tobramycin-loaded scaffolds (TBMC1–TBME3) under in vitro conditions lasted for seven days to evaluate both drug release patterns and continuous release capabilities (fig. 6). A rapid drug discharge occurred during the first 2 d of testing among all formulations, but TBMC1 released 28.3% of tobramycin while TBMC2 released 30.5% of tobramycin. This initial surge may be attributed to the rapid diffusion of surface-adsorbed GNS molecules facilitated by the hydrophilic nature of the polymers used. Unlike PLA-PVA/NaCl scaffolds, [36], where thermal treatment reduced burst release (20% → 12%), our dip-coating method achieved similar control (25% → 10%) without post-processing. Following this initial phase, a gradual and sustained release pattern was recorded for all formulations, indicating diffusion-controlled release behaviour consistent with a matrix-based delivery system. Among all the scaffolds, TBMC1 exhibited the highest cumulative drug release (56.9±2.4%) by day 7, while TBME3 released the least (41.1±1.8%), indicating that polymer composition and concentration played a significant role in modulating drug diffusion. Our sustained release (14–21 d) surpasses tobramycin-eluting chitosan coatings on stainless steel screws (72–96 h) [37] and matches PCL/GS electro spun fibers (14 d) [37]. The variation in release profiles could be attributed to the different hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance between chitosan and Eudragit RS100 polymers and their respective impact on drug entrapment and mobility within the scaffold matrix. The drug release patterns from all six formulations were evaluated through mathematical models, starting from Zero-order up to Korsmeyer Peppas to determine the drug diffusion mechanism. A strong correlation was observed with the zero-order model across most formulations (R²>0.97), suggesting a constant rate of drug release over time. Moreover, the Higuchi model also yielded high correlation coefficients (R²>0.97), confirming that diffusion was a dominant mechanism. Further, release exponent values (n) derived from the Korsmeyer Peppas model ranged from 0.1625 to 0.2271 for all formulations, indicating a Fickian diffusion mechanism. This pattern implies that drug release occurred predominantly through a diffusion-controlled process without significant involvement of matrix erosion. TBME3, characterized by the lowest ‘n’ value (0.1625), showed the slowest release rate, possibly due to denser polymer network restricting water penetration and drug diffusion. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that scaffold morphology, infill density, and polymer-drug interactions significantly affect drug mobility and release kinetics.

Fig. 4: FTIR spectrum of a) Uncoated scaffold, b) Chitosan-coated scaffold, c) Eudragit-coated scaffold

Fig. 5: XRD pattern of uncoated scaffold, Eudragit RS 100, and chitosan coated scaffold

Fig. 6: In vitro dissolution profiles of formulations TBMC1 to TBME3

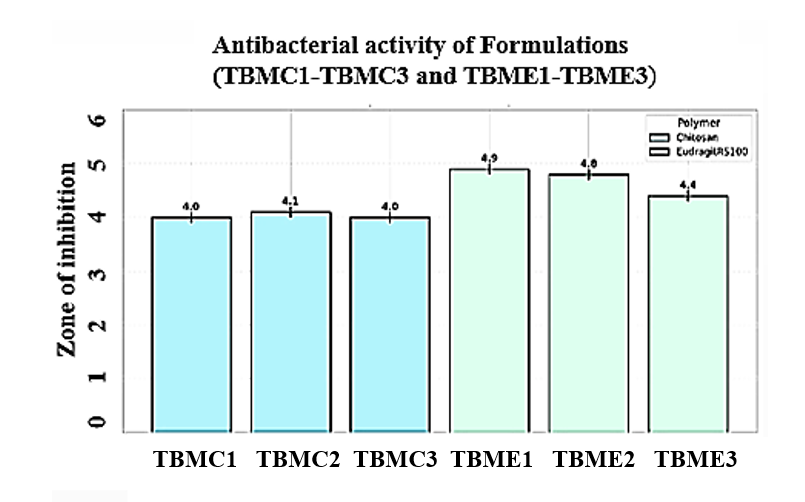

Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial study against E. coli revealed that concentration-dependent inhibition of bacterial growth. Scaffold samples from TBMC1-TBME3, the 3% sample exhibited the highest zone of inhibition against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, indicating enhanced antibacterial efficacy. The antibacterial efficacy aligns with PLA/nHA/CS-Van scaffolds3, which inhibited S. aureus, but our tobramycin-loaded system targets g-negative pathogens like E. coli, broadening clinical applicability [27]. The results suggest that increasing the active component concentration significantly improves the scaffold's antibacterial performance. The Zone of inhibition results were mentioned in table 6 and diameter of the inhibition zone is shown in the fig. 6. The antibacterial efficacy aligns with PLA/nHA/CS-Van scaffolds, which inhibited S. aureus, but our tobramycin-loaded system targets g-negative pathogens like E. coli, broadening clinical applicability [38].

Degradation study by simulated body fluid

3D printed scaffold degradation rate was measured by immersion in SBF solution and calculate the weight loss at different days interval such as 15th, 30th, 45thand 60th day, that is mentioned in table 2. The weight loss has increased with an increase in time interval for the scaffold. Scaffold surface deposition of crystal and foam structures increases with increase in time, which is shown in below fig. 8. The result showed that, in 15th day the increase of grains was very less and the grains were increased in 30th, 45th and 60th d. In 60th d the grains have multiplied and made a foam-like structure. This study result shown a good degradation rate for the scaffold.

The calculation of weight loss was done using below Equation

The total mass loss after day 60 was 1.48±0.02 g, which translates to near 37%±1.2% degradation using the mass of the original scaffold (4.0±0.16 g). This gradual decrease in mass is evidence of biodegradability, which in this instance is a measurement of the role of the percentage of the mass of the scaffold remaining in a physiological environment with time.

Table 2: Weight loss of scaffold in degradation study (n=6)

| S. No. | Scaffold immersion days in SBF solution (days) | Weight loss(g) |

| 1 | 15 | 0.16± 0.15 |

| 2 | 30 | 0.57± 0.15 |

| 3 | 45 | 1.03± 0.15 |

| 4 | 60 | 1.48± 0.15 |

A)

B

Fig. 7: Results of antibacterial study for TBMC1, TBMC2, TBMC3, TBME1, TBME2 and TBME3 against E. coli. (A) Zone of inhibition (cm) bar chart for zone formation over one week (Error bars represent±SD, n = 5) and B) Agar plates depicting the zone of inhibition

Fig. 8: SEM image in (100x) for degradation study where formation of bone like apatite layer on scaffold in a) 15th day b) 30th day c) 45th day and d) 60th day

CONCLUSION

PLA scaffolds using CAD models were additively manufactured using 3D printing via FDM, using tobramycin-loaded scaffolds which were coated with chitosan or Eudragit RS100 (1-3% w/v). The scaffolds had interconnected porosity which was perfect in bone tissue engineering. SEM proved homogeneous coating of polymer to drugs and little blockage of pores. FTIR and XRD showed that it showed only physical interactions without changing the crystalline structure of PLA. The release of drugs was biphasic and sustained in the systems during 7 d, particularly in systems comprising 3% of the polymer-coated scaffolds (TBMC3, TBME3), which was observed to follow Fickian diffusion (R 2>0.97; n<0.45). Antibacterial tests (ASTM E2149-13a) proved the extended release and intrinsic activity of chitosan, as stronger inhibition areas appeared in the products with a high polymer. Degradation experiments of SBF revealed the gradual loss of weight (up to 1.48 g) and mineral precipitation, which is the evidence of bioactivity.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Resources, Swati Swagatika Swain and Veera Venkata Satyanarayana Reddy Karri for Writing, reviewing and editing. All authors have agreed to publish the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Weiss MB, Syed SA, Whiteson HZ, Hirani R, Etienne M, Tiwari RK. Navigating post-traumatic osteoporosis: a comprehensive review of epidemiology pathophysiology, diagnosis treatment and future directions. Life (Basel). 2024 May;14(5):561. doi: 10.3390/life14050561, PMID 38792583.

Ferraz MP. Bone grafts in dental medicine: an overview of autografts allografts and synthetic materials. Materials (Basel). 2023 May 31;16(11):4117. doi: 10.3390/ma16114117, PMID 37297251.

Rahman A, Tanvir KF, Jui HK, Ahmed MdT, Nipu SM, Hussain SB. Design and analysis of 3D-printed PLA scaffolds: enhancing mechanical properties. Results Eng. 2025 Jul 7;27:106156. doi: 10.1016/j.rineng.2025.106156.

Sousa HC, Ruben RB, Viana JC. On the fused deposition modelling of personalised bio-scaffolds: materials design and manufacturing aspects. Bioengineering (Basel). 2024 Jul 31;11(8):769. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering11080769, PMID 39199727.

Dorati R, De Trizio A, Modena T, Conti B, Benazzo F, Gastaldi G. Biodegradable scaffolds for bone regeneration combined with drug delivery systems in osteomyelitis therapy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2017 Dec 12;10(4):96. doi: 10.3390/ph10040096, PMID 29231857.

Ergul NM, Unal S, Kartal I, Kalkandelen C, Ekren N, Kilic O. 3D printing of chitosan/ poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogel containing synthesized hydroxyapatite scaffolds for hard tissue engineering. Polym Test. 2019 Oct 1;79:106006. doi: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2019.106006.

Bulut B, Duman S. Evaluation of mechanical behavior bioactivity and cytotoxicity of chitosan/akermanite-TiO2 3D-printed scaffolds for bone tissue applications. Ceram Int. 2022 Aug 1;48(15):21378-88. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.04.104.

Karaca I, Aldemir Dikici B. Quantitative evaluation of the pore and window sizes of tissue engineering scaffolds on scanning electron microscope images using deep learning. ACS Omega. 2024 Jun 11;9(23):24695-706. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.4c01234, PMID 38882138.

Selim M, Mousa HM, Abdel Jaber GT, Barhoum A. Abdal hay A. Innovative designs of 3D scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration: understanding principles and addressing challenges. Eur Polym J. 2024 Jul 17;215:113251. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2024.113251.

Mattavelli D, Verzeletti V, Deganello A, Fiorentino A, Gualtieri T, Ferrari M. Computer aided designed 3D-printed polymeric scaffolds for personalized reconstruction of maxillary and mandibular defects: a proof-of-concept study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024;281(3):1493-503. doi: 10.1007/s00405-023-08392-0, PMID 38170208.

Gnanavel S, Kaavya P. Design and development of novel 3D bone scaffold for implant application. Mater Today Proc. 2022 Jan 1;59:775-80. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.12.580.

Winarso R, Anggoro PW, Ismail R, Jamari J, Bayuseno AP. Application of fused deposition modeling (FDM) on bone scaffold manufacturing process: a review. Heliyon. 2022 Nov 22;8(11):e11701. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11701, PMID 36444266.

Tamarit Martinez C, Bernat Just L, Bueno Lopez C, Alambiaga Caravaca AM, Merino V, Lopez Castellano A. An antibacterial-loaded PLA 3D-printed model for temporary prosthesis in arthroplasty infections: evaluation of the impact of layer thickness on the mechanical strength of a construct and drug release. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Aug 30;16(9):1151. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16091151, PMID 39339188.

Mills DK, Jammalamadaka U, Tappa K, Weisman J. Studies on the cytocompatibility mechanical and antimicrobial properties of 3D printed poly(methyl methacrylate) beads. Bioact Mater. 2018 Jun 1;3(2):157-66. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2018.01.006, PMID 29744453.

Gurpreet Singh, Abdul Faruk, Preet Mohinder Singh Bedi. Spectral analysis of drug-loaded nanoparticles for drug polymer interactions. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics. 2018;8(6):111-8. doi: 10.22270/jddt.v8i6.2030.

Aryal S, Hu CM, Zhang L. Polymeric nanoparticles with precise ratiometric control over drug loading for combination therapy. Mol Pharm. 2011 Aug 1;8(4):1401-7. doi: 10.1021/mp200243k, PMID 21696189.

Dong Z, Gong J, Zhang H, Ni Y, Cheng L, Song Q. Preparation and characterization of 3D printed porous 45S5 bioglass bioceramic for bone tissue engineering application. Int J Bioprint. 2022 Sep 1;8(4):613. doi: 10.18063/ijb.v8i4.613, PMID 36404785.

Hill M, Cunningham RN, Hathout RM, Johnston C, Hardy JG, Migaud ME. Formulation of antimicrobial tobramycin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles via complexation with AOT. J Funct Biomater. 2019 Jun 13;10(2):26. doi: 10.3390/jfb10020026, PMID 31200522.

Admane P, Gupta J, IJA, Kumar R, Panda AK. Design and evaluation of antibiotic-releasing self-assembled scaffolds at room temperature using biodegradable polymer particles. Int J Pharm. 2017 Mar 30;520(1-2):284-96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.01.071, PMID 28185962.

Bhardwaj K, Sridhar U. A novel biodegradable polymer scaffold for in vitro growth of corneal epithelial cells. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022 Oct;70(10):3693-7. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_210_22, PMID 36190075.

Shapovalova KS, Zatonsky GV, Razumova EA, Ipatova DA, Lukianov DA, Sergiev PV. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of new 6″-modified tobramycin derivatives. Antibiotics (Basel). 2024 Dec 6;13(12):1191. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics13121191, PMID 39766581.

Doganay MT, Chelliah CJ, Tozluyurt A, Hujer AM, Obaro SK, Gurkan U. 3D printed materials for combating antimicrobial resistance. Mater Today (Kidlington). 2023;67:371-98. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2023.05.030, PMID 37790286.

Klicova M, Mullerova S, Rosendorf J, Klapstova A, Jirkovec R, Erben J. Large scale development of antibacterial scaffolds: gentamicin sulphate-loaded biodegradable nanofibers for gastrointestinal applications. ACS Omega. 2023 Oct 17;8(43):40823-35. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c05924, PMID 37929155.

Baino F, Yamaguchi S. The use of simulated body fluid (SBF) for assessing materials bioactivity in the context of tissue engineering: review and challenges. Biomimetics (Basel). 2020 Dec;5(4):57. doi: 10.3390/biomimetics5040057, PMID 33138246.

Xu Z, Hodgson MA, Cao P. Effect of immersion in simulated body fluid on the mechanical properties and biocompatibility of sintered Fe–Mn-based alloys. Metals. 2016 Dec;6(12):309. doi: 10.3390/met6120309.

Kim SJ, Kim TH, Choi JW, Kwon IK. Current perspectives of biodegradable drug-eluting stents for improved safety. Biotechnol Bioproc E. 2012 Oct 1;17(5):912-24. doi: 10.1007/s12257-011-0571-z.

Gao X, Xu Z, Li S, Cheng L, Xu D, Li L. Chitosan vancomycin hydrogel incorporated bone repair scaffold based on staggered orthogonal structure: a viable dually controlled drug delivery system. RSC Adv. 2023 Jan 24;13(6):3759-65. doi: 10.1039/d2ra07828g, PMID 36756570.

Hwang MR, Kim JO, Lee JH, Kim YI, Kim JH, Chang SW. Gentamicin-loaded wound dressing with polyvinyl alcohol/dextran hydrogel: gel characterization and in vivo healing evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2010 Jul 7;11(3):1092-103. doi: 10.1208/s12249-010-9474-0, PMID 20607628.

Channasanon S, Udomkusonsri P, Chantaweroad S, Tesavibul P, Tanodekaew S. Gentamicin released from porous scaffolds fabricated by stereolithography. J Healthc Eng. 2017;2017:9547896. doi: 10.1155/2017/9547896, PMID 29065670.

Salehi M, Naseri Nosar M, Azami M, Nodooshan SJ, Arish J. Comparative study of poly(L-lactic acid) scaffolds coated with chitosan nanoparticles prepared via ultrasonication and ionic gelation techniques. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016 Oct 20;13(5):498-506. doi: 10.1007/s13770-016-9083-4, PMID 30603431.

Li J, Cai C, Li J, Li J, Li J, Sun T. Chitosan-based nanomaterials for drug delivery. Molecules. 2018 Oct 16;23(10):2661. doi: 10.3390/molecules23102661, PMID 30332830.

Garavand F, Rouhi M, Jafarzadeh S, Khodaei D, Cacciotti I, Zargar M. Tuning the physicochemical structural and antimicrobial attributes of whey-based poly (L-lactic acid) (PLLA) films by chitosan nanoparticles. Front Nutr. 2022 Apr 28;9:880520. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.880520, PMID 35571878.

Shanmugavadivu A, Selvamurugan N. Surface engineering of 3D-printed polylactic acid scaffolds with polydopamine and 4-methoxycinnamic acid–chitosan nanoparticles for bone regeneration. Nanoscale Adv. 2025 Mar 11;7(6):1636-49. doi: 10.1039/d4na00768a, PMID 39886612.

Dukle A, Sankar MR. 3D-printed polylactic acid scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: bioactivity-enhancing strategies based on composite filaments and coatings. Mater Today Commun. 2024 Aug 1;40:109776. doi: 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.109776.

Amini Moghaddam M, Di Martino A, Sopik T, Fei H, Cisas J, Pummerova M. Polylactide/polyvinylalcohol-based porous bioscaffold loaded with gentamicin for wound dressing applications. Polymers. 2021 Jan;13(6):921. doi: 10.3390/polym13060921, PMID 33802770.

Glinka M, Filatova K, Kucinska Lipka J, Sopik T, Domincova Bergerova E, Mikulcova V. Antibacterial porous systems based on polylactide loaded with amikacin. Molecules. 2022 Oct 19;27(20):7045. doi: 10.3390/molecules27207045, PMID 36296639.

Greene AH, Bumgardner JD, Yang Y, Moseley J, Haggard WO. Chitosan-coated stainless steel screws for fixation in contaminated fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008 Apr 29;466(7):1699-704. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0269-5, PMID 18443893.

Liu Z, Li S, Xu Z, Li L, Liu Y, Gao X. Preparation and characterization of carboxymethyl chitosan/sodium alginate composite hydrogel scaffolds carrying chlorhexidine and strontium-doped hydroxyapatite. ACS Omega. 2024 May 21;9(20):22230-9. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.4c01237, PMID 38799338.