Int J App Pharm, Vol 17, Issue 6, 2025, 485-498Original Article

FOCUSED INSIGHTS INTO ALZHEIMER’S TREATMENT STRATEGIES: PHARMACOPHORE MODELLING, DFT STUDIES, MD SIMULATIONS AND SH-SY5Y NEUROPROTECTION OF NARINGIN

SINDHU T. J.1, JAINEY P. JAMES*1, ZAKIYA FATHIMA C.1, RAJALAKSHIMI VASUDEVAN2, SHANKAR G. ALEGAON3

*1Nitte (Deemed to be University), NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (NGSMIPS), Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Deralakatte, Mangalore-575018, Karnataka, India. 2Department of Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy, King Khalid University, Abha-61441, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 3Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, KLE College of Pharmacy, Belagavi, KLE Academy of Higher Education and Research, Belagavi-590010, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Jainey P. James; *Email: jaineyjames@gmail.com

Received: 12 Jul 2025, Revised and Accepted: 05 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder involving oxidative stress, protein aggregation, and neurotransmitter imbalance. This study aimed to evaluate the neuroprotective potential of Drynaria quercifolia (DQ) phytoconstituents, particularly DQ5 (naringin), using in silico, in vitro, and pharmacological analyses for multitargeted AD therapy.

Methods: Phytocompounds from DQ were analysed through molecular docking to assess binding affinities with AD-related targets, including acetylcholinesterase (AChE), monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B), and peroxiredoxin-5 (Prdx-5). DQ5 (naringin) was further evaluated using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and pharmacophore modelling. Density Functional Theory (DFT) was employed to assess molecular stability and reactivity. In vitro assays measured AChE, MAO-B, tyrosinase inhibition, and hydrogen peroxide scavenging. Neuroprotective effects were evaluated using MTT assay on SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells.

Results: Molecular docking showed strong binding of DQ5 to AChE (-14.182 kcal/mol) and MAO-B (-13.393 kcal/mol). MD simulations confirmed complex stability. DQ5 (naringin) exhibits high stability in its gas-phase optimised structure, and its small HOMO-LUMO gap indicates it may be quite reactive, which could contribute to its biological activity. DQ5 inhibited AChE (IC₅₀ = 8.05±1.02 µg/ml) and 90% SH-SY5Y cell viability. Pharmacokinetic predictions supported favourable drug-likeness and safety profiles.

Conclusion: DQ5 (naringin), a key metabolite from DQ, exhibits significant multitarget activity against AD-related enzymes and oxidative stress. The compound's pharmacological properties and neuroprotective effects highlight its promise as a natural therapeutic candidate for addressing multiple pathways involved in AD pathogenesis.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Drynaria quercifolia (DQ), Naringin, Acetylcholinesterase, Peroxiredoxin, Molecular docking, Molecular dynamics simulations, DFT studies, SH-SY5Y cells

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2025v17i6.56043 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijap

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurological condition marked by a steady decline in cognitive abilities, such as memory, thinking, and behaviour [1]. Amyloid-beta plaque buildup, tau protein tangles, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and disruption of neurotransmission are the disease's hallmarks; these conditions all lead to neuronal death [2]. It is the most prevalent cause of dementia globally, and as of right now, there is no proven treatment [3, 4]. The multifactorial character of AD may be better addressed by a multitarget therapy strategy than by single-target tactics, according to recent studies [5].

Medicinal herbs are widely used in the prevention and treatment of illnesses [6, 7]. Plant-based medications are gaining popularity due to the disadvantages of contemporary medicines [8, 9]. The plant Drynaria quercifolia (DQ), also known as the oak-leaf fern, has been widely utilised in traditional medicine to treat various illnesses, such as neurological issues, inflammatory diseases, and bone abnormalities [10]. Bioactive substances like phenolics, terpenoids and flavonoids, which have been demonstrated to have neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant qualities, are abundant in the rhizome of DQ [11].

Numerous factors impact the evolution of AD. Some essential theories include cholinergic theory [12], oxidative stress hypothesis [13], and tyrosinase hyperactivity [14]. Acetylcholine depletion due to cholinergic neuron loss in AD worsens cognitive decline. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors, such as donepezil and rivastigmine, increase acetylcholine but have side effects [15, 16].

Tyrosinase hyperactivity contributes to AD by producing oxidative stress and neuronal damage via quinones [17, 18]. Peroxiredoxins (Prx), antioxidant enzymes that lower reactive oxygen species (ROS), are linked to protein misfolding in AD despite their protective role [19–20]. A possible treatment target for AD has been drawn to monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) because of its connection to aberrant γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) synthesis in reactive astrocytes [21].

The possibility of using Drynaria species to treat AD has been investigated in recent research. Drynaria species have been reported to enhance cognitive performance [22]. Another study demonstrated a substantial neuroprotective impact against Aβ-induced toxicity in PC12 cells. This implies that DR could be a viable all-natural AD therapy [23].

Axonal regeneration effects on Aβ25–35-induced atrophy were observed by the phenolic substances (2S)-neoeriocitrin and caffeic acid 4-O-glucoside, which were extracted from the Drynaria species extract [24]. Furthermore, naringenin, a phenolic molecule in Drynaria species and its metabolite, naringenin-7-O-glucuronide, can traverse the blood-brain barrier and exhibit noteworthy neuroprotective properties against axonal atrophy produced by Aβ.

These results emphasise the possibility of using Drynaria species to treat AD and stress the significance of metabolite identification to gain a deeper understanding of the therapeutic mechanisms of natural substances [25]. DQ has been shown to ameliorate scopolamine-induced memory impairment in mice because of its anticholinesterase and antioxidant properties [26].

The neuroprotective qualities of most Drynaria species have been the main focus of research. Unfortunately, little is known about their secondary metabolites' potential to prevent AD and how they work. Interestingly, no study has used SH-SY5Y cell lines to investigate DQ's neuroprotective effects or MAO-B inhibitory activity and its phytoconstituents. Furthermore, there is limited in silico research on the molecular binding interactions between DQ and acetylcholinesterase, and none have used DFT-based molecular simulations to examine the electronic characteristics or confirm their stability. As a result, a thorough analysis of the processes by which the main ingredients in DQ block important enzymes is necessary.

This work aims to find putative multitarget compounds from DQ that could be lead candidates for additional development in AD treatment by combining computational and experimental methodologies. This can tackle the complex nature of AD by focusing on many enzymes related to oxidative stress and neuroinflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In silico platform

Schrödinger 2023-1, LLC, New York's Maestro 13.5.128 version was used for all the works. The workstation has an Intel Core i7 (octa-core) processor, 16GB of RAM, a 1TB hard drive, and a 64-bit operating system running Linux-x86_64.

Preparation of ligands

Seven phytoconstituents of DQ (DQ1-7) were selected from the IMPPAT database (Indian Medicinal Plants Phytochemistry and Therapeutics) (https://cb.imsc.res.in/imppat/) and literature reviews [27] shown in table 1. The 2D chemical structures of DQ1–DQ7(3,4-dihydroxy benzoic acid, 3-acetyl lupeol, Beta-sitasterol, Friedelin, Naringin, Epifriedelinol and β-amyrin) have now been provided in the Supplementary Material (table S1). The ligprep module in Schrodinger was utilised to generate low-energy conformations, and the OPLS3 force field was applied to reduce energy [28]. Four proteins were selected to target cholinergic deficiency, antityrosinase inhibitory activity and oxidative stress related to neurodegenerative diseases: acetylcholinesterase (PDB ID-6O4W) [29], monoamine oxidase-B (PDB ID-2BYB) [30], (tyrosinase enzyme (PDB ID-5I38) [31], and peroxiredoxin (PDB ID-1HD2) [32]. The protein preparation wizard processed the proteins [33]. Using receptor grid generation, a grid box encircled the co-crystal active site [34]. By using flexible docking in ligand sampling, the XP approach enables a more thorough investigation of the ligand-binding space [35]. The ligand that is most likely to form the most stable complex with the target protein can be identified using the glide score, a measurement of binding affinity. The Schrodinger prime module was utilised to ascertain the binding energy of the receptor-ligand complex. The Prime module is used in this calculation to get the total free energy in dGbind (kcal/mol) [36-38].

Physicochemical characteristics

QikProp software from Schrödinger was utilised to ascertain the physicochemical characteristics of ligand molecules [39]. The scores aid in understanding bioavailability and drug-likeness characteristics. Physicochemical properties such as molecular weight, logP, acceptor HB (hydrogen bond) studies, and donor HB (hydrogen bond) studies were assessed using Lipinski's Rule of Five. Estimates were also performed for the physicochemical characteristics of ligand molecules, including their volume, polar surface area (PSA) and Jorgensen's Rule of Three.

ADMET characteristics

The produced ligands were processed using the QikProp program to determine their ADMET properties. The characteristics of ADMET include Caco-2 cell permeability, permeability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), oral absorption percentage in humans, permeability of the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) and its hydrophobic and hydrophilic components (FOSA and FISA). In addition, ADMET properties comprise dermal penetration, plasma-protein binding, metabolism and the Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) value for the Human Ether-A-Go-Go-Related Gene (hERG) Potassium Channel [40].

Predicted targets for phytoconstituents

Therapeutic repositioning and avoiding undesirable side effects may be facilitated by the ability to predict targets and off-targets for medications or therapeutic candidates. Numerous methods have been presented to anticipate interactions between drugs and targets. Super-PRED is a prediction web server for target prediction of compounds [41]. Target prediction for an input chemical can be performed at the target prediction site. The similarity distribution of ligands is used in this target prediction method to estimate the thresholds of targets.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

The Desmond module, which examines compactness, stability, and fluctuations, was used for the XP best-docked complex to evaluate the molecular docking investigation results through molecular dynamics simulation (Schrodinger Release 2021-4) [42-44]. Each protein-ligand combination was immersed in an orthorhombic box using a simple point charge (SPC) aqueous model, and an OPLS3e force field was assigned for positional constraint and minimization. A sufficient concentration of counter-ions (Nap/Cl-) was provided to neutralise the complexes. For every complex in the average pressure and temperature (NPT) ensemble, the simulation time was set at 100 ns. Desmond's default protocols were used to balance and decrease the systems. Ultimately, the ligands' convergence to equilibrium was examined by plotting the protein residues' root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and the root mean square deviation (RMSD) for the protein backbone. MD simulations were done for the best-docked complex DQ5 with 6O4W.

Pharmacophore modelling

The Schrodinger software Phase application used a receptor-based pharmacophore method that deduced interactions from PDB data, including charge transfer, hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic areas in the macromolecular environment, to produce pharmacophore models [45-46]. This technique outlines the spatial configurations of functional groups essential to biological activity. Understanding the necessary elements required for ligand binding and biological activity is made more accessible with the aid of this pharmacophore model. This method assesses the key pharmacophoric characteristics of the ligands that give rise to bioactivity. Pharmacophore modelling was done for the most stable complex DQ5/6O4W found from MD simulation results.

Density functional theory (DFT) studies

Geometric optimisation

Studies using density functional theory (DFT) concentrate on geometric optimisation, which predicts the best stable molecule structure by minimising the system's energy [47]. This allows bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles to be calculated. DFT is a computational quantum chemistry and materials science technique investigating molecules' electronic structures and characteristics. The B3LYP functional (Becke's three-parameter hybrid functional with Lee–Yang–Parr correlation) and the 6-31G (d,p) basis set were used to geometrically optimise the DQ5 (naringin) molecule of the Jaguar module of the Schrödinger software. Electrostatic potential maps (ESP) were also produced for every molecule. The frontier molecular orbitals, including the highest occupied molecular orbital (EHOMO) and others, were used to determine quantum chemical parameters, including the energy gap (ΔEGAP), dipole moment (μ), hardness (η), and local softness (σ) and the following equation.

Chemicals and reagents for extraction

Sigma-Aldrich, Loba Chemie, and Yarrow Chem supplied all of the chemicals. The rhizomes of DQ collected from Idukki district, Kerala, were authenticated (Supplementary file) in the Department of Botany, Nirmala College, Muvattupuzha, using Fern Flora of South India. The powdered material was extracted using a Soxhlet apparatus [48-53].

Phytochemical screening of plant extract

A preliminary qualitative examination of the extracts tests for proteins, fats and oils, alkaloids, glycosides, flavonoids, steroids, carbohydrates and terpenoids [54-58].

In vitro studies

Ellman’s test method assessed the potency of ethyl acetate extracts and DQ5 (naringin) acetylcholinesterase inhibitory [59]. The absorbance was measured at 412 nm on the microplate reader (LISA Plus thermoscientific). The MAO-B assay was performed using a fluorometric method. The fluorescence was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 530 and 585 nanometers, respectively [60]. Dopachrome production at 492 nm was used to measure the tyrosinase inhibition activity [59] Antioxidant properties were evaluated by hydrogen peroxide scavenging assay (230 nm) [61]. The following equation was employed to compute percentage inhibition.

% inhibition =

The sample and standard inhibition were expressed as the concentration required for 50% inhibition (IC50).

MTT assay for the evaluation of neuroprotective action of DQ and DQ5 on scopolamine-induced neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells

The MTT assay evaluated the impact of DQ extract and DQ5 (naringin) on scopolamine-induced neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y CRL-2266cells [62]. Scopolamine is used to induce cellular stress in the seeded SHSY5Y cells. 100 µl of DMEM supplemented with FBS was used to plate 10,000 SH-SY5Y cells per well in 96-well plates. For the blank wells, 100 µl of DMEM supplemented with FBS was added without any cells. DQ extract and DQ5 (naringin) concentrations were 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 μg/ml. 20 μl of MTT reagent (5 mg/ml) was added after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO₂, and the mixture was then incubated for 4 h. The results were expressed as a percentage growth in each well compared to control cells cultivated without the standard/DQ. After dissolving formazan crystals in DMSO, the absorbance at 550 nm was measured. The following equation was used to compute relative cell viability: Cell viability (%) =

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In silico studies

Molecular docking

For further docking studies, seven phytoconstituents found in the rhizome of DQ (DQ1-DQ7) were selected (table S1), and their anti-Alzheimer activity was assessed against three targets. Compared to their co-crystals (donepezil, kojic acid and benzoic acid), all phytoconstituents showed a remarkable binding affinity. Additionally, they showed distinct interactions with acetylcholinesterase (6O4W). The docking scores and interactions were investigated, including hydrophobic, polar, and hydrogen bonding (table 1).

Compound DQ5 showed the best glide scores and molecular interactions with two targeted enzymes (6O4W and 1HD2) out of the seven phytoconstituents, which indicates its potential anti-Alzheimer efficacy. Protein-ligand complexes were graded according to the glide score, which efficiently separates active molecules with high binding affinities from inactive ones. Based on their highest docking score, compound DQ5 was chosen for an in-depth investigation to learn more about their molecular interactions and potential as an anti-Alzheimer drug.

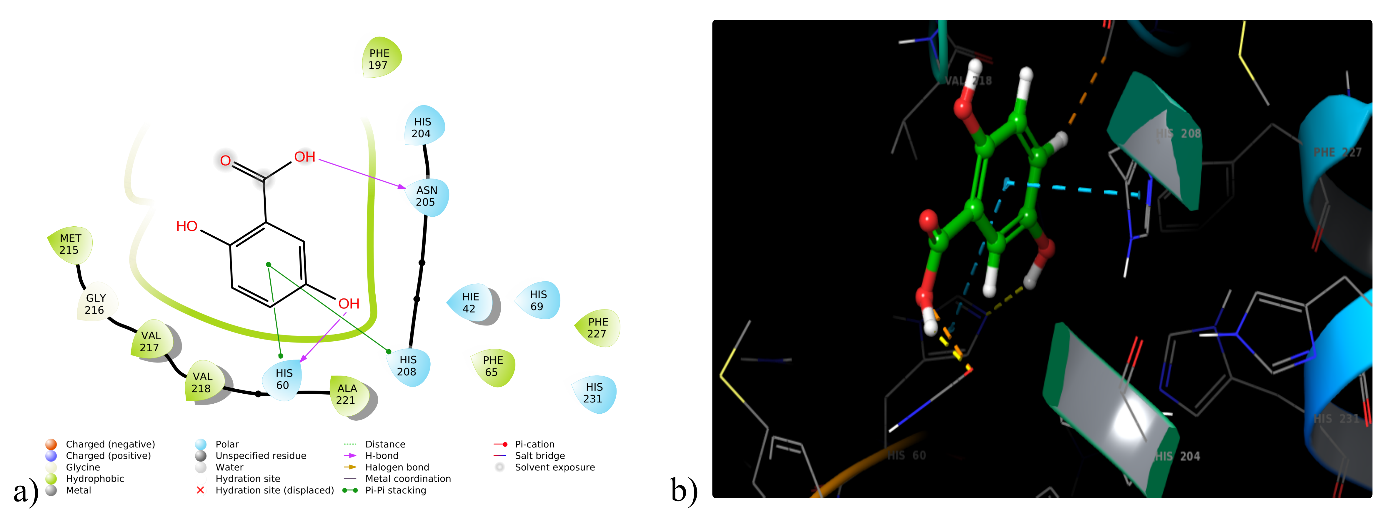

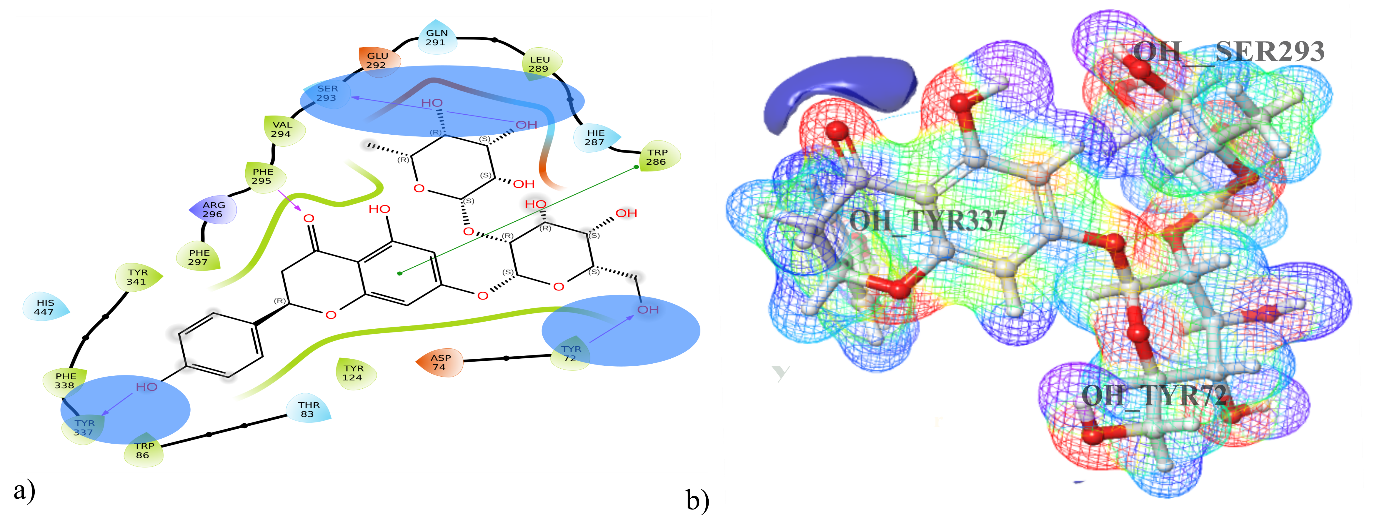

Binding with acetylcholinesterase enzyme (6O4W)

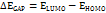

With an impressive binding affinity, every phytoconstituent could be docked into the acetylcholinesterase (6O4W) protein's active site with docking scores ranging from-14.182 to-2.498 kcal/mol(table 1). With a docking score of-14.182 kcal/mol, compound DQ5 (naringin) demonstrated outstanding binding with 6O4W, beating the co-crystal donepezil (-9.54 kcal/mol). Compound DQ5 demonstrated hydrogen bond interactions with Ser293, Phe295, Tyr72, and Tyr337 and hydrophobic interactions with Trp286, Leu289, Val294, Phe295, Phe297, Tyr341, Phe338, Tyr337, Trp86 and Tyr124. Additionally, it formed polar interactions with the amino acid residues Hie287, Gln291, Ser293, His447 and Thr83, and pi-pi stacking with Trp286 of the acetylcholinesterase protein active site (table 2). Fig. 1 shows the 2D and 3D interaction of compound DQ5 with acetylcholinesterase enzyme (6O4W).

In a validation docking study, donepezil was redocked into its own binding site under the same parameters and protocol as the original docking. The resulting root mean square deviation (RMSD) between the docked pose and the co-crystallised pose was reported as 1.217 Å. This is well below the commonly accepted ≤ 2 Å threshold, supporting that docking protocol for 6O4W would be considered validated. The resulting root‑mean‑square deviation (RMSD) between the docked pose and the co-crystallised pose was reported as 1.208 Å . This is well below the commonly accepted ≤ 2.0 Å threshold, supporting that the docking protocol for 6O4W would be considered validated.

These findings confirm a positive correlation between molecular docking results and the in vitro acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. According to a literature survey, the highest docking score, DQ5 (naringin), improved long-term potentiation and restored learning and memory deficits caused by Alzheimer's disease [63].

Binding with monoamino oxidase-B enzyme (2BYB)

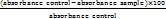

Only two phytocompounds have interacted with MAO-B. DQ5 (naringin) and DQ1 (3,4-di hydroxybenzoic acid) have interacted with a docking score of-13.393 and-5.796 kcal/mol, respectively. The DQ5 has shown the highest binding with 2BYB with a docking score greater than the co-crystal (-6.46 kcal/mol). 2D showed hydrophobic interaction of DQ5 with residue Tyr 60, Phe 343, Ile 316, Ile 198, Ile 199, Tyr 326, Leu 171, Cys 172, Tyr 188, Met 436, Try 435, Ty 398, Cys 397 and made a hydrogen bond with Tyr 398, Lys 296, Ser 59 (table 1, fig. 2).

Fig. 1: (a) 2D and (b) 3D interaction of DQ5 with acetylcholinesterase enzyme (6O4W)

Fig. 2: (a) 2D and (b) 3D interaction of DQ5 with monoamino oxidase enzyme (2BYB)

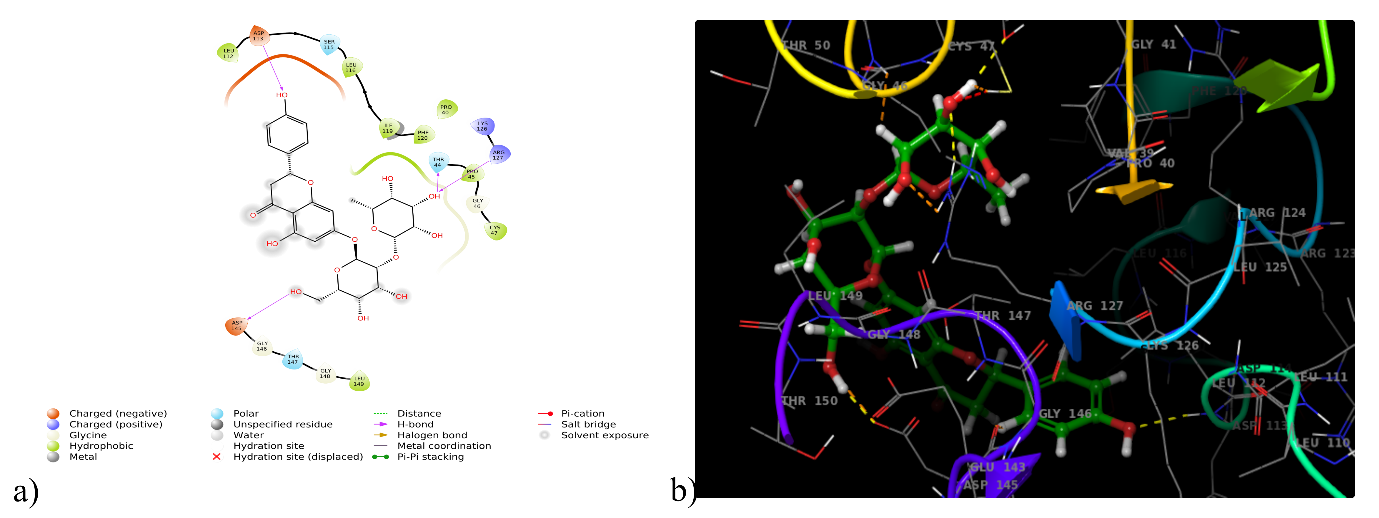

Binding with tyrosinase enzyme (5I38)

Five phytoconstituents (DQ1, DQ2, DQ4, DQ6 and DQ7) could dock into the active domain of the tyrosinase enzyme (5I38) with a remarkable binding affinity, with docking scores varied from -5.56 to -3.40 kcal/mol. Compound DQ1 displayed the highest binding score (5I38) with a docking score of -5.56 kcal/mol, whereas the co-crystal kojic acid showed -7.15 kcal/mol. Compound DQ1 (3, 4-dihydroxy benzoic acid) exhibited hydrophobic interactions with Ala221, Phe197, Phe227, Phe65 and Met215, as well as hydrogen bond interactions with Asn205 and His60. Furthermore, it established polar contacts with the tyrosinase protein active site's amino acid residues His231, His69, Hie42, His208, Asn205, His204 and His60. A Glide XP docking validation study reported that the reference ligand (kojic acid) reproduced its experimental binding pose with an RMSD of 0.132 Å. This is well below the commonly accepted ≤ 2.0 Å threshold, supporting that the docking protocol for 5I38 would be considered validated. The 2D and 3D interactions between DQ1 and the tyrosinase enzyme (5I38) are depicted in fig. 3 and table 1.

Fig. 3: (a) 2D and (b) 3D interaction of DQ1 with tyrosinase enzyme (5I38)

Binding with peroxiredoxin (1HD2)

Antioxidant activity can be measured by examining the interactions with the enzyme peroxiredoxin (1HD2). DQ5 (naringin) scored the greatest docking score (-6.644 kcal/mol) with 1HD2, and hydrogen bonding was attributed to the amino acids Asp113, Asp145, Thr44, and Arg127. Whereas, hydrophobic interactions were linked to Cys47, Pro40, Pro45, Phe120, Ile119, Leu116, Leu112, and Leu149 and polar interactions with Thr44 and Ser115 (fig. 4). It exceeded co-crystal benzoic acid's docking score of 5.506 kcal/mol (table 1).

Fig. 4: (a) 2D and (b) 3D interaction of DQ5 with peroxiredoxin enzyme (1HD2)

Binding free energy calculation

The extra-precision docking findings are validated by carefully grading the ligands according to their binding free energies and calculating the binding free energy of the ligand-protein complexes using the MM-GBSA approach. The ΔGbind values of the enzymes acetylcholinesterase (6O4W) and human peroxiredoxin (1HD2) ranged from-29.69 (DQ1) to-86.49 kcal/mol (DQ5) and-29.95 (DQ1) to-68.26 (DQ5) kcal/mol, respectively. The binding free energy (ΔGbind) scores with the acetylcholinesterase enzymes revealed that the best-interacted molecule DQ5 (naringin) (-86.49 kcal/mol) had better binding energy than the co-crystal donepezil (-77.91 kcal/mol) and benzoic acid of the human peroxiredoxin enzyme (-26.55 kcal/mol) (table 1).

Table 1: Compound code, phytoconstituents, docking scores, interactions and binding free energy of compounds with target proteins 6O4W, 2BYB, 5I38 and 1HD2

| Compound code and phytoconstituents name | PDB ID | Docking scores (kcal/mol) |

Hydrophobic interactions | Polar interactions | Hydrogen bonds | Pi-pi stacking | MM GBSA dG Bind (kcal/mol) |

DQ1 3,4-dihydroxy benzoic acid |

6O4W | -5.87 | Phe297, Tyr124, Ala204, Phe338, Tyr337, Ile451, Trp86 | Ser203, His447 | Gly122, Gly121, Ser203, Glh202 | Tyr337, His447 | -29.69 |

| 2BYB | -5.79 | Tyr 326, Ile 198, Ile 199, Leu 171, Cys 172, Phe 168, Ile 316 | Gln 206, ser 200 | Ile 199 | - | -23.56 | |

| 5I38 | -5.56 | Phe197, Phe227, Phe65, Ala221, Val218, Val217, Met215 | His231, His69, Hie42, His208, Asn205, His204, His60 | Asn205, His60 | His208 | -38.21 | |

| 1HD2 | -5.40 | Phe120, Pro40, Pro45, Cys47, Leu149, Leu116 | Thr147, Thr44 | Thr147, Thr44, Gly46, Cys47 | - | -29.95 | |

DQ2 3-acetyl lupeol |

6O4W | -4.01 | Trp286, Leu289, Leu86, Tyr341, Phe295, Val294, Tyr72 | Hie287, Ser293 | Hie287 | - | -42.45 |

| 2BYB | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 5I38 | -1.10 | Met61, Phe197, Pro201, Met215, Ala221, Phe227, Val217, Val218 | Hie42, His208, Asn205, His204 | - | - | -58.83 | |

| 1HD2 | -3.687 | Leu116, Ile119, Phe120, Pro40, Leu149, Pro45, Cys47 | Thr147, Thr44 | Lys49 | - | -50.10 | |

DQ3 Beta-sitasterol |

6O4W | -9.27 | Trp286, Leu76, Val294, Phe295, Phe297, Tyr124, Leu76, Tyr72, Tyr341, Phe295, Phe297 | His447, Ser293, Ser203 | Glh202, Tyr133 | - | -48.80 |

| 2BYB | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 5I38 | Phe227, Met215, Val217, Val218, Ala221, Phe65, Met61, Met184, Pro201, Phe197 | His231, Hie42, His60, His208, Asn205, His204 | - | - | -67.93 | ||

| 1HD2 | - | Phe120, Ile119, Pro45, Leu196, Pro40, Cys47, Leu149 | Thr147, Thr44 | - | - | -64.42 | |

DQ4 Friedelin |

6O4W | -2.49 | Trp286, Leu289, Phe295, Val294, Tyr72, Tyr341, Leu76 | Ser93, Thr75 | - | - | -47.94 |

| 2BYB | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 5I38 | -3.40 | Phe197, Met61, Pro201, Phe227, Met215, Val217, Val218, Ala221 | Hie42, Asn205, His204, His60, His231, His208 | - | - | -42.13 | |

| 1HD2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

DQ5 Naringin |

6O4W | -14.18 | Trp286, Leu289, Val294, Phe295, Phe297, Tyr341, Phe338, Tyr337, Tyr72, Trp86, Tyr124 | Hie287, Gln291, Ser293, His447, Thr83 | Ser293, Phe295, Tyr72, Tyr337 | Trp286 | -86.49 |

| 2BYB | -13.39 | Tyr 60, Phe 343, Ile 316, Ile 198, Ile 199, Tyr 326, Leu 171, Cys 172, Tyr 188, Met 436, Try 435, Ty 398, Cys 397 | Thr 43, Thr 426, Thr 399, Ser 59, Gln 206 | Tyr 398, Lys 296, Ser 59 | Tyr 326 | -80.53 | |

| 5I38 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 1HD2 | -6.64 | Cys47, Pro40, Pro45, Phe120, Ile119, Leu116, Leu112, Leu149 | Thr44, Ser115 | Asp113, Asp145, Thr44, Arg127 | - | -68.26 | |

DQ6 Epifriedelinol |

6O4W | -4.63 | Trp286, Leu289,Val294, Phe295, Phe297,Phe338, Tyr341, Tyr72, Leu76, Tyr124 | Ser293 | - | - | -35.49 |

| 2BYB | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 5I38 | -3.56 | Met215, Pro201,Val217, Val218, Met61, Phe197 | His204, Asn205, His60, His208, | Asn205 | - | -58.45 | |

| 1HD2 | -0.17 | Leu116, Ile119, Phe120, Pro40, Pro45, Cys47 | Thr44, Thr147 | - | - | -49.15 | |

DQ7 β-amyrin |

6O4W | -3.91 | Trp286, Leu289,Val284, Phe295, Phe297,Tyr124, Leu76, Tyr72, Tyr341, Phe338 | Hie287, Ser293, Thr75 | - | - | -45.23 |

| 2BYB | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 5I38 | -3.53 | Phe65, Met61, Val217, Val218, Pro201, Phe197 | His60, Asn57, His208, Asn205, His204 | - | - | -57.68 | |

| 1HD2 | -1.15 | Phe120, Ile119, Pro45, Leu116, Pro40, Cys47, Leu149 | Thr147, Thr44 | Arg127 | - | -58.91 | |

| Donepezil | 6O4W | -9.54 | Phe338, Tyr337, Ile 451, Tyr133, Trp86, Tyr124, Tyr341, Phe297, Tyr72, Trp286, Leu289, Val294, Phe295, | Ser203, His447, Ser293 | Phe295 | Trp286, Trp86 | -77.91 |

| Selegiline | 2BYB | -6.46 | Leu 164, Leu 167, Phe 168, Leu 171, Cys 172, Pro 104, Phe 103, Trp 119, Tyr 435, Ile 198, Ile 199, Tyr 326, Ile 316 | -44.93 | |||

| Kojic acid | 5I38 | -7.15 | Gln 206 | - | - | -40.17 | |

| Benzoic acid | 1HD2 | -5.50 | Met215, Val217, Val218, Ala221, Phe65, Phe227 | His204, Asn205, His208, His60, Hie42, His231 | Gly216, | -27.37 |

Physicochemical properties

The physicochemical characteristics were determined using QikProp. All compounds followed Lipinski’s Rule of Five, establishing the drug-likeness attribute. Table 2 lists the different physicochemical characteristics of the seven compounds (DQ1-DQ7). The molecular weight was between 154.12 and 616.62, matching the range suggested by Qikprop. It was demonstrated that the permissible range for the lipophilicity QPlogPo/w of the seven derivatives was-1.49 to 7.82. The polar surface area (PSA), which varied from 18.40 Å to 227.94 Å, was connected to the Van der Waals surface area of polar nitrogen and oxygen atoms. The predicted range of donors and acceptors for hydrogen bonding was 1.70–19.30 acceptors and 0.0–8.0 donors, respectively. It has been demonstrated that all derivatives, with a few noteworthy exceptions, adhere to Lipinski's RO5. Essentially, the concept is that every component may be categorised as a molecule similar to a drug.

Table 2: Physicochemical properties of phytoconstituents

| S. No. | Code | Molecular weight | Volume | Log P | Donor HB | Acceptor HB | PSA | Rule of five | Rule of three |

| DQ1 | 154.12 | 504.81 | 0.78 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 92.28 | 0 | 0 | |

| DQ2 | 468.76 | 1496.71 | 7.82 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 32.60 | 1 | 1 | |

| DQ3 | 414.71 | - | 8.02 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 20.23 | 1 | 0 | |

| DQ4 | 426.72 | 1361.26 | 6.90 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 25.77 | 1 | 1 | |

| DQ5 | 580.54 | 1561.58 | -1.49 | 7.00 | 19.30 | 227.94 | 3 | 2 | |

| DQ6 | 428.74 | 1367.50 | 6.97 | 1.00 | 1.70 | 18.40 | 1 | 1 | |

| DQ7 | 426.72 | 1368.11 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 1.70 | 18.92 | 1 | 1 | |

| Donepezil | 379.49 | 1271.92 | 4.36 | 0.00 | 5.50 | 50.85 | 0 | 0 | |

| Kojic acid | 142.11 | 479.28 | -0.63 | 2.00 | 4.95 | 81.68 | 0 | 0 | |

| Benzoic acid | 122.12 | 462.80 | 1.86 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 50.23 | 0 | 0 |

Donar HB-Hydrogen Bond Donor, Accept HB-Hydrogen Bond Acceptor, Log P-Oil/water partition coefficient, PSA-Polar Surface Area.

ADMET properties

QikProp was utilised to ascertain the pharmacokinetic characteristics. It helps establish absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion and provides information on the onset of action and how the drug crosses barriers. The medicinal chemist can alter the substance as needed to enhance activity with the aid of the ADME properties. QikProp program investigated properties such as plasma-protein binding, inhibiting hERG, blood-brain barrier penetration, metabolism, solvent-accessible surface area, and bioavailability.

Bioavailability prediction

The metrics used to assess oral absorption include the predicted aqueous solubility, logS, the anticipated proportion of oral absorption by humans, and compliance with Jorgensen's well-known "Rule of Three (RO3)". This rule states that a molecule is more likely to be swallowed if it satisfies all or any of the following criteria: #Primary Metabolites<7, logS>-5.7 and Caco-2>22 nm/s. Caco-2 cell permeability was used to quantify the gut-blood barrier's non-active transport, and the examined derivatives produced a wide range of results. All phytochemicals met Jorgensen's RO3 requirements and showed the most significant penetration to the gut-blood barrier (table 3).

Blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration

QPlogBB was used to assess the brain's accessibility.-2 indicates very low or no CNS penetration,-1 indicates low penetration, 0 represents moderate or uncertain potential, 1 suggests high penetration, and 2 indicates very high CNS penetration. Every derivative exhibited CNS values between -2 and +2, and all could pass across the blood-brain barrier (table 3).

Prognosis of metabolism

Data shown in table 6 predicted that every compound can undergo metabolism over one to eight processes, except DQ3 and DQ5 (table 3).

Potassium (hERG K+) channel blockage

hERG K+channel blockers may be hazardous, and IC50 values can often be used to predict and project the cardiac toxicity of early-stage medications. All compounds have hERG K+values within the permitted limit (table 3).

Table 3: ADMET properties of phytoconstituents

| S. No. | Code | % Human oral absorption |

# metab |

QP logS |

QPlog hERG |

QPLog Caco |

CNS | QP logBB |

QP log Khsa |

| Acceptable range | >80% High <25% Low |

(1-8) | -6.5 to-0.5 | Below –5 | >500 Great <25 Poor |

–2 to+2 | –3.0 to 1.2 | –1.5 to 1.5 | |

| DQ1 | 58.46 | 2 | -1.06 | -1.49 | 31.97 | -2 | -1.16 | -0.77 | |

| DQ2 | 100.00 | 2 | -8.88 | -4.02 | 3982.20 | 1 | 0.06 | 2.34 | |

| DQ4 | 100.00 | 2 | -7.85 | -3.35 | 3866.88 | 1 | 0.19 | 2.03 | |

| DQ5 | 0.00 | 10 | -2.84 | -5.52 | 4.03 | -2 | -3.91 | -1.12 | |

| DQ6 | 100.00 | 1 | -7.83 | -3.45 | 4922.06 | 1 | 0.22 | 2.01 | |

| DQ7 | 100.00 | 3 | -7.82 | -3.54 | 4872.07 | 1 | 0.22 | 2.01 | |

| Donepezil | 100.00 | 6 | -4.53 | -6.63 | 913.32 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.58 | |

| Kojic acid | 66.03 | 2 | -0.43 | -3.196 | 245.99 | -1 | -0.93 | -0.86 | |

| Benzoic acid | 80.64 | 0 | -1.47 | -1.704 | 244.92 | -1 | -0.30 | -0.68 |

#metab-Number of likely metabolic reactions, QPlogS-Aqueous solubility, QPloghERG-IC50 value for blockage of hERG K+channels, QPlogCaco-Apparent Caco-2 cell permeability, CNS-Central Nervous System activity"-–2 indicates very low or no CNS penetration, –1 indicates low penetration, 0 represents moderate or uncertain potential, 1 suggests high penetration, and 2 indicates very high CNS penetration., QPlogBB-Brain/Blood partition coefficient, QPlogKhsa-Binding to human serum albumin

Surface area accessible to solvents (SASA, FOSA, FISA)

The solvent and molecules contact area represented SASA, typically between 300.0 and 1000.0 Å, and all deviations fall within the acknowledged limits. Saturated carbon and linked hydrogen, SASA's hydrophobic element, FOSA (0–750), and the reported values fall within the allowable range. FISA was represented by the hydrophilic region of the SASA (SASA on heteroatoms of N, O, and H), with values ranging from 7.0 to 330.0 (table 4).

Predicted targets for phytoconstituents

The SuperPred web server was developed to predict chemical compound indications for medicinal use. All phytoconstituents and their anticipated targets associated with Alzheimer's disease demonstrated almost 70% and higher probability percentages in this investigation (table 5). The phytoconstituent DQ5(naringin), which had the most excellent docking score, showed a 99.30% probability of binding to the predicted target amyloid beta-peptide linked with the endoplasmic reticulum in Alzheimer's disease.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular dynamics simulations (Desmond module) studies assessed the quality of the molecular docking results for the XP best-docked complex of DQ5 and DQ3 with the enzyme acetylcholinesterase. The simulations study evaluated the protein-ligand complex's compactness, stability, and conformational fluctuations (Schrodinger Release 2021-4). Each protein-ligand combination was immersed in an orthorhombic box using a simple point charge (SPC) aqueous model, and an OPLS3e force field was assigned for positional constraint and minimisation. A sufficient counter-ion concentration (Na+/Cl-) was provided to neutralise the complexes. For every complex in the average pressure and temperature (NPT) ensemble, the simulation time was set at 100 ns. Desmond's default protocols were used to balance and decrease the systems. Ultimately, the ligands' convergence to equilibrium was examined by plotting the protein residues' root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and the root mean square deviation (RMSD) for the protein backbone.

Table 4: Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA, FOSA and FISA) of DQ’s phytoconstituents

| S. No. | Comp. Code | SASA | FOSA | FISA |

| DQ1 | 330.11 | 0.00 | 199.80 | |

| DQ2 | 740.87 | 672.52 | 41.73 | |

| DQ3 | 755.58 | 676.69 | 48.9 | |

| DQ4 | 669.36 | 626.28 | 43.08 | |

| DQ5 | 810.84 | 285.28 | 357.44 | |

| DQ6 | 676.30 | 644.27 | 32.03 | |

| DQ7 | 676.28 | 624.33 | 32.49 | |

| Donepezil | 719.32 | 418.80 | 49.81 | |

| Selegiline | 66.22 | 219.98 | 3.35 | |

| Kojic acid | 320.11 | 55.47 | 169.24 | |

| Benzoic acid | 308.72 | 0.00 | 106.55 |

SASA: Total solvent accessible surface area, FOSA: Hydrophobic component of the SASA, FISA: Hydrophilic component of the SASA, PISA-π (carbon and attached hydrogen) component of the SASA.

Table 5: Predicted targets for DQ5

| Target name | Probability | Indication |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Amyloid Beta-Peptide-Binding Protein | 99.3% | Alzheimer disease |

| Cathepsin D | 96.15% | Alzheimer disease |

| Glutamate receptor ionotropic, AMPA 2 | 87.87% | Parkinson disease |

| Adenosine A1 receptor | 80.56% | Parkinson disease |

| Platelet-derived growth factor receptor | 72.28% | Alzheimer disease |

| Transthyretin | 70.19% | Amyloidosis |

| Monoamine oxidase A | 67.89% | Neurodegenerative disorder |

| Neurotensin receptor 2 | 51.25% | Neurodegenerative disorder |

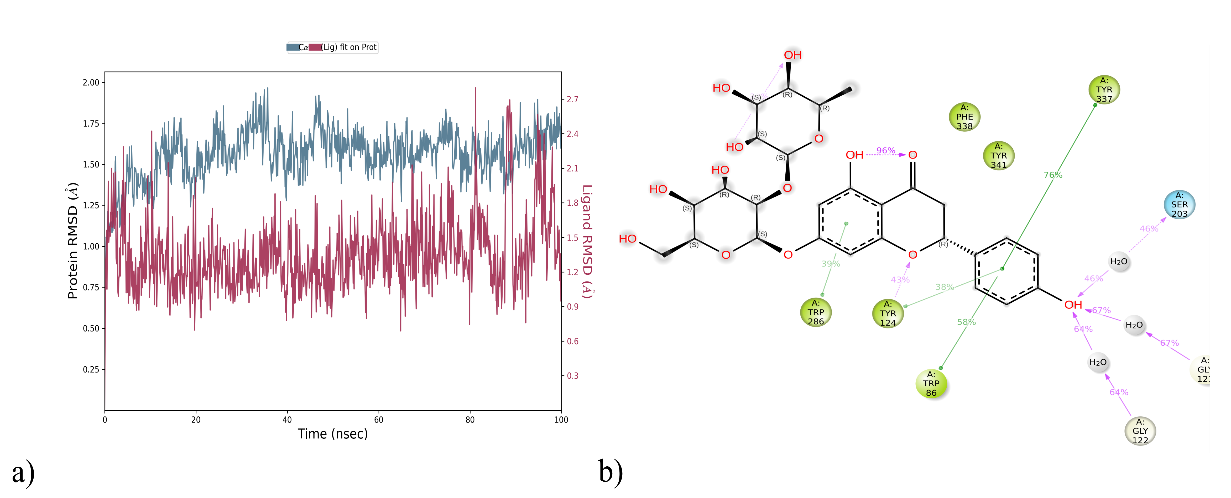

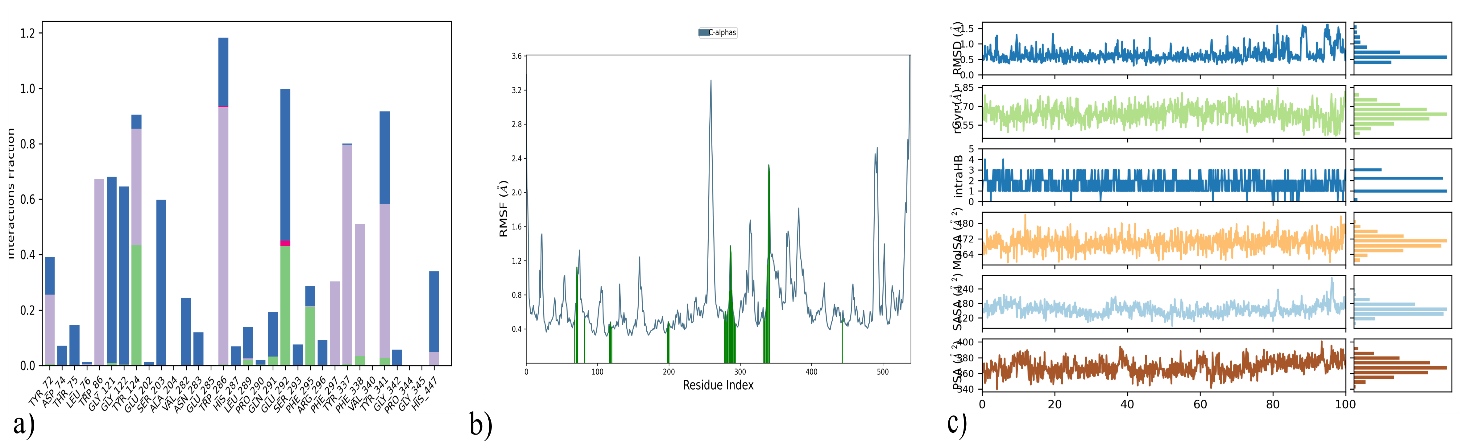

Analysis of compound DQ5/6O4W complex simulation

Molecular dynamics simulations outline the ligand-protein complexes and proteins' flexibility and stability. The docked complex DQ5/6O4W was simulated using molecular dynamics to ascertain the inhibitors' binding affinity for the protein. According to the interaction mode analysis, the binding modes acquired during MD simulation were relatively similar to those obtained post-docking (table 6). Based on all backbone Cα atoms compared to the matching original structures of each trajectory for the simulated ligand-protein complexes, the protein RMSD value of 6O4W varied up to 2.00 Å, as shown in fig. 5a. The values of the ligand RMSD for compound DQ5, found to be 2.7 Å, demonstrated its stability within the protein binding pocket. These findings show unequivocally that DQ5 exhibits excellent stability when attached to the target 604W.

Following the simulation run, the average of the interaction occupancies of the binding site residues was used to analyse each system's per-residue interaction. Tyr124 maintained the H-bond interaction (43%) post-docking. The pi-pi stacking with Tyr337 (76%), Tyr124 (38%), Trp86 (58%) and Trp286 (39%) were retained during pre and post-MD interaction (fig. 5b). Protein interactions with the ligand can be monitored throughout the simulation. The simulation interactions diagram exhibiting the value 1.2 for the residue Trp286 highlighted the multiple contacts with the ligand (fig. 6a). Analysis of the RMSF for Cα atoms and the protein-ligand complex revealed fluctuations ranging from 0.4 to 3.6 Å. (fig. 6b), the highest interaction occupancy in the DQ5/6O4W complex.

The provided fig. (fig. 6c) directly supports the statement by demonstrating that a comprehensive MD analysis requires the inclusion of metrics beyond just RMSD and RMSF. The graphs for Rg, intra HB, and SASA are explicitly shown, proving that these are standard and necessary outputs of an MD simulation. They provide insights into the protein's compactness, solvent exposure, and internal hydrogen-bonding network, respectively. Each of these metrics provides a unique and vital perspective on the protein's dynamic behaviour and stability that is not captured by a simple measure of atomic fluctuations, such as RMSD or RMSF.

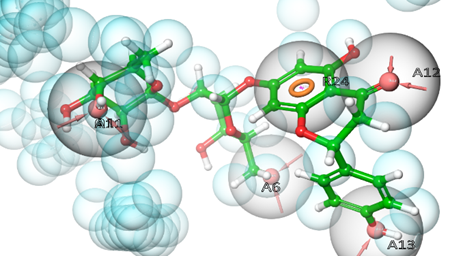

Pharmacophore modelling of DQ5 (naringin) with 6O4W

Pharmacophore modelling studies assessed the best-docked complex of DQ5 (naringin) with the enzyme acetylcholinesterase. DQ5 (naringin) is anticipated to form hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues when docked with acetylcholinesterase (6O4W). Results predicted that the residues Tyr72, Phe295, Ser293 and Tyr337 are indispensable for forming hydrogen bonds between acceptor groups A6, A12, A11 and A13. One pi-pi stacking existed between the amino acid Trp286 and the aromatic ring R24 (table 7) (fig. 7).

Table 6: Comparison of the interacting residues in both pre and post-MD simulation of DQ5 (naringin) with target protein 6O4W

| Highest docking score compounds | Binding interactions post-docking (pre MD simulation) |

Binding interactions (post MD simulation) |

| DQ5 | Trp286, Leu289, Val294, Phe295, Phe297, Tyr341, Phe338, Tyr337, Tyr72, Trp86, Tyr124, Hie287, Gln291, Ser293, His447, Thr83, Ser293, Phe295, Tyr72, Tyr337, Trp286 | Trp286, Tyr124,Trp86, Phe 338, Tyr341,Tyr337, Ser203 |

Fig. 5: (a) Analysis of RMSD (Å) and (b) Protein-ligand contacts of DQ5 with 6O4W for a 100 ns of MD run

Fig. 6: (a) Protein-ligand contacts of 6O4W_DQ5 for a 100 ns of MD run (b) RMSF of complex and C-alpha atoms (blue), Protein residues that interact with the ligand (green)(c) PSA (Å), SASA (Å), MolSA (Å), intra HB (Å), rGyr (Å) and RMSD (Å) of 6O4W_DQ5, Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), Polar surface area (PSA), Solvent accessible surface area (SASA), Molecular surface area (MolSA), Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonds (intraHB), Radius of Gyration (rGyr), Root mean square deviation(RMSD)

Fig. 7: Pharmacophore hypothesis: compound DQ5 with 6O4W

Table 7: Pharmacophore hypothesis features of DQ5 with target protein 6O4W

| S. No. | Phytoconstituent | Pharmacophoric features | Amino acid residues |

| 1 | DQ5 | A13 | Tyr337 |

| A6 | Tyr72 | ||

| A12 | Phe295 | ||

| A11 | Ser293 | ||

| R24 | Trp286 |

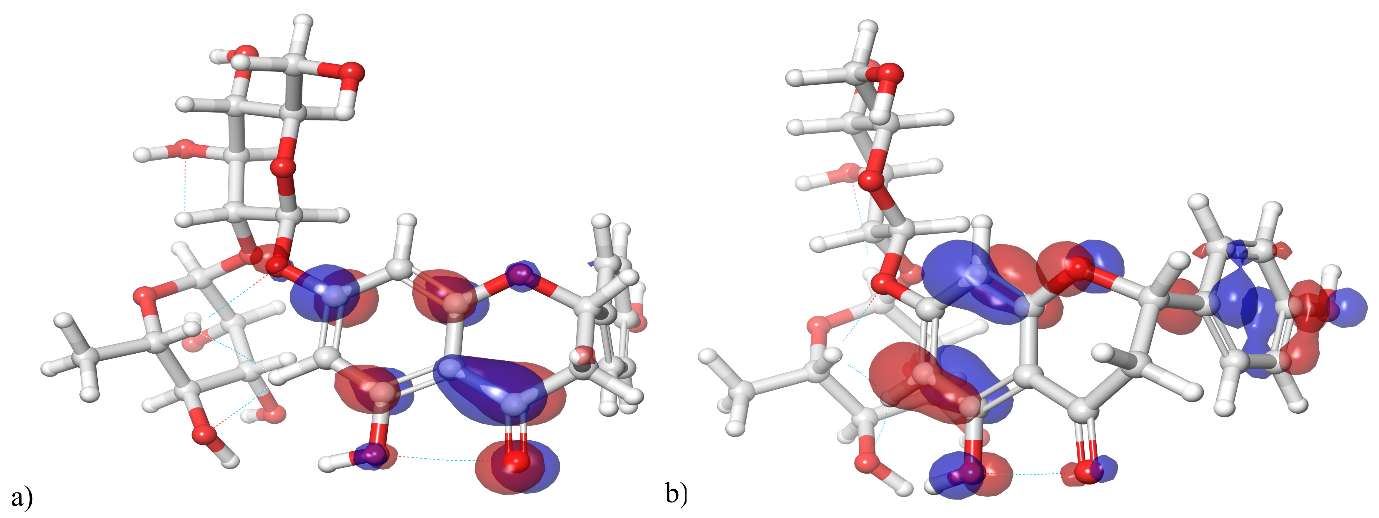

Density functional theory (DFT) of DQ5 (naringin)

Optimisation of molecular geometries

In quantum chemistry, molecular orbitals (MOs) are essential to comprehending a molecule's chemical characteristics, such as its reactivity and binding affinity. The lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) are the most significant MOs. The DQ5 (naringin) molecular structure has an optimised gas-phase energy of-2101.350085. Chemical properties, including reactivity, stability, and kinetics, can be explained by molecular orbitals. Since a molecule's hardness (η) indicates how soft or hard it is, softer molecules are typically more reactive. The DFT/B3LYP/6-31G (d,p) method was used to calculate the energy gap and chemical reactivity descriptors. The HOMO and LUMO frontier orbitals of DQ5 (naringin) are shown in fig. 8. Generally, more molecular reactivity is indicated by a lower energy gap between HOMO and LUMO. DQ5 (naringin) show a ΔEGAP of −0.175439. DQ5 (naringin) exhibits high stability in its gas-phase optimised structure, and its small HOMO-LUMO gap indicates it may be quite reactive, which could contribute to its biological activity.

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP)

An electrostatic potential is essential for determining how a molecule's electric charge is distributed. When placed in a binding pocket, it provides information about electrostatic interactions with proteins and within the molecule. Finding areas with a high electron density (negative potential) and a low electron density (positive potential) on a molecular surface is made more accessible by mapping the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP). This data can be utilised to investigate molecular interactions and forecast electrophilic and nucleophilic attack sites. The 6-31G (d,p) basis set and the B3LYP method were used to calculate the molecule electrostatic potentials at the optimised geometry. Fig. 9 shows the MEP for DQ5 (naringin). The graph shows that the characteristics of the substituted functional groups dictate the size, shape, and orientation of the neutral (green), negative (red, electrophilic attack sites), and positive (blue, nucleophilic attack sites) areas. The degree of drug-receptor binding at the active site of the target receptor is strongly influenced by differences in the mapping of electrostatic potential in drug-like compounds.

The combined overlay of the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) map and docking

The combined overlay of the Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) map and docking pose presents a compelling visualisation of the electrostatic complementarity between the ligand and the AChE active site. Notably, the blue region of the MEP map indicating an electron-rich (nucleophilic) zone on the ligand—aligns well with Ser293, a hydrogen bond donor residue in the AChE binding pocket (PDB: 6O4W). This spatial alignment strongly supports the formation of a favourable hydrogen bond interaction, which is observed in the docking results.

This correlation confirms the reliability of the docking pose and validates the proposed binding mode by demonstrating that electrostatic interactions are consistent with the chemical environment of the active site. The MEP surface highlights key regions responsible for stabilizing interactions within the binding site, particularly through charge complementarity with amino acid residues like Ser293 (fig. 9).

This overlay strengthens the interpretation of the docking results by providing visual and electrostatic confirmation of critical interactions, thereby reinforcing the binding affinity and orientation of the ligand within the AChE enzyme.

Fig. 8: HOMO and LUMO orbitals of DQ5 (naringin)

Fig. 9: a) Molecular electrostatic potential map for DQ5 (naringin) and b) docking pose with 6O4W

Extraction of powdered drugs and qualitative chemical examination of extracts

The rhizomes of DQ (fig. 10a and b) collected and the percentage yield was determined as follows: benzene (6.00%), ethyl acetate (5.01%), chloroform (2.10%), ethanol (3.20%), and water (6.40%). Ethyl acetate extraction was performed at 60 °C in 200 ml solvent for 48 h. Qualitative chemical analysis revealed that the ethyl acetate extract contained the highest concentration of phytochemicals compared to other extracts, prompting the continuation of in vitro studies with this extract (table 8).

Fig. 10: a) Drynariaquercifolia growing in its natural habitat b) rhizome

Table 8: Percentage yield and qualitative chemical analysis of various extracts of Drynariaquercifolia

| Extracts of Drynariaquercifolia rhizome | Benzene | Ethyl acetate | Chloroform | Ethanol | Water |

| % yield | 6.00% | 5.01% | 2.10% | 3.20% | 6.40% |

| Alkaloids (Mayer’s and Wagner’s Test) | - | - | + | - | - |

| Flavonoids (Lead Acetate Test) | - | + | - | - | - |

| Proteins and amino acids (Millions and Biuret Test) | - | - | + | + | + |

| Glycosides (Modified Borntrager’s Test, Legal’s Test, Baljet Test, Liebermann Burchard's Test and Keller Killani Test) | - | + | - | - | - |

| Saponins (Froth’s Test] | + | + | - | - | - |

| Steroids (Liebermann Burchard's Test) | - | + | - | - | - |

| Fat and oil (Stain Test, Soap Test) | + | + | + | + | - |

| Carbo hydrates (Molisch’s Test, Benedict’s test, Fehling’s Test, Barfoed’s Test | - | + | - | - | + |

| Terpenoids (Salkowski test) | - | + | - | - | - |

Abbreviations+positive,-negative

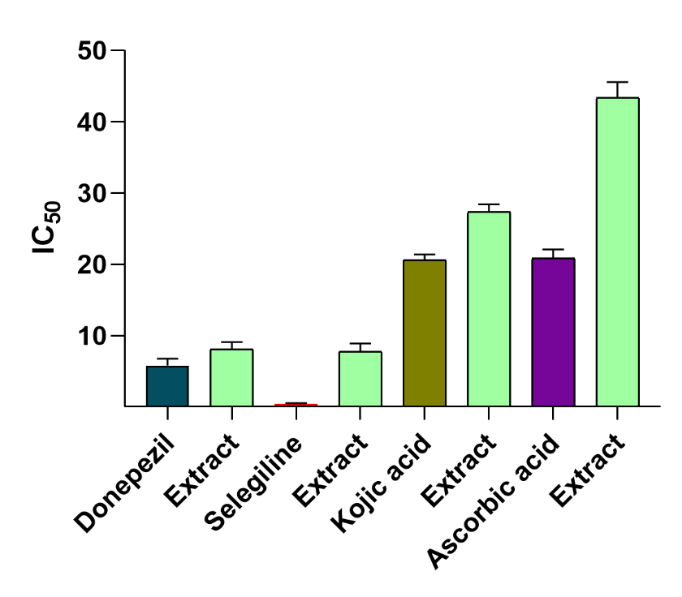

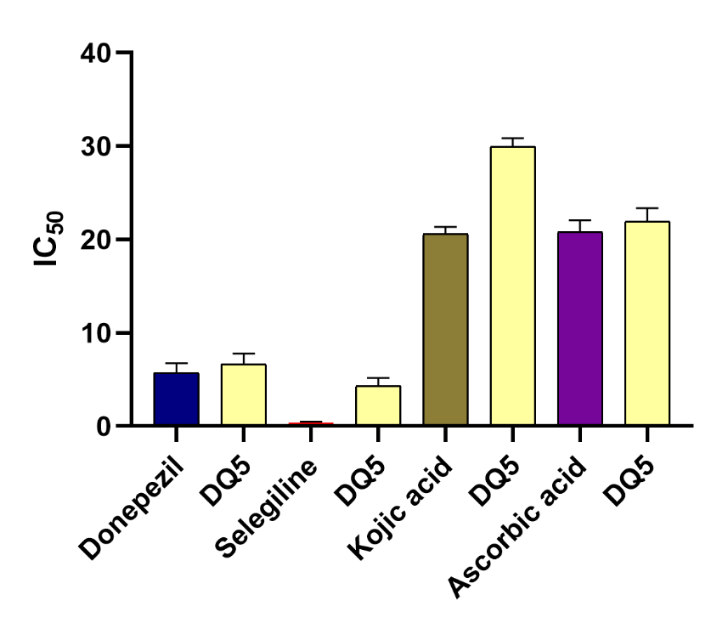

Fig. 11: In vitro studies data of DQ extract, Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory test (standard-Donepezil); MAO-B Inhibitory Test (standard-Selegiline); Tyrosinase Inhibitory Test (standard-Kojic acid); Hydrogen peroxide free radical scavenging effects (standard Ascorbic acid). value were expressed in mean± Standard error of the mean(n=4)p≤ 0.05). one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post‑hoc test. For AChE: p = 0.012. For MAO‑B: p = 0.05 For tyrosinase: p = 0.001 For H₂O₂ scavenging: p = 0.005)

In vitro studies

Acetylcholinesterase, MAO-B, Tyrosinase inhibition test and hydrogen peroxide free radical scavenging effects of DQ extract

The DQ extract demonstrated potent acetylcholinesterase inhibition, with an IC50 value of 8.05±1.02 µg/ml. The inhibitory potency of the extract against MAO-B was evaluated using a fluorometric method. From the results, it is inferred that the DQ extract obtained moderate MAO-B inhibitory action. They showed notable tyrosinase inhibition, with an IC50 value of 27.32±1.08 µg/ml. This activity is likely attributed to the plant's flavonoid-rich secondary metabolites, which can chelate metals like iron and copper [64, 66]. DQ extract demonstrated moderate antioxidant activity, with an IC50 value of 43.37±2.19 µg/ml in the hydrogen peroxide scavenging assay [67, 68] (fig. 11).

Acetylcholinesterase, MAO-B, Tyrosinase inhibition test and hydrogen peroxide free radical scavenging effects of DQ5 (naringin)

The computational findings of DQ5 (naringin) were validated by assessing its activity through in vitro experiments, as depicted in fig. 12. DQ5 (naringin) was checked for its inhibitory potential for the enzymes AchE, MAO-B and tyrosinase, as well as hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity. DQ5 was found to have potent anti-AChE and hydrogen peroxide scavenging effects and moderate anti-MAO-B and anti-tyrosinase activity when compared with their standards, respectively. These results comply with the docking results. Therefore, these studies highlight the biological significance of DQ5 (naringin), which can be developed as lead in treating Alzheimer’s disease. Naringin’s ability to reduce oxidative stress, mitigate histopathological damage, and improve cognitive function aligns with previous research emphasising its potential in treating neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s [69]. In this study, the protective effects of naringin against AlCl3-induced AD in rats further strengthen its therapeutic promise. The improvements in behavioural performance and the reduction of oxidative mitochondrial damage observed in naringin-treated rats suggest that it can counteract the neurotoxic effects of aluminium, which is known to induce AD-like pathology. Additionally, the neurochemical and molecular analyses confirm naringin’s ability to modulate pathways involved in oxidative stress and inflammation [70]. Naringin's neuroprotective effects might also be due to its metabolite, naringenin, a flavonoid aglycone (a non-sugar form of naringin). Many studies have proven its neuroprotective effects. The inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) by naringenin indicates its potential to improve cholinergic function, an essential aspect of AD pathology. This is further supported by the significant reduction in AChE activity in Citrus junos extracts, with naringenin identified as the active component [71].

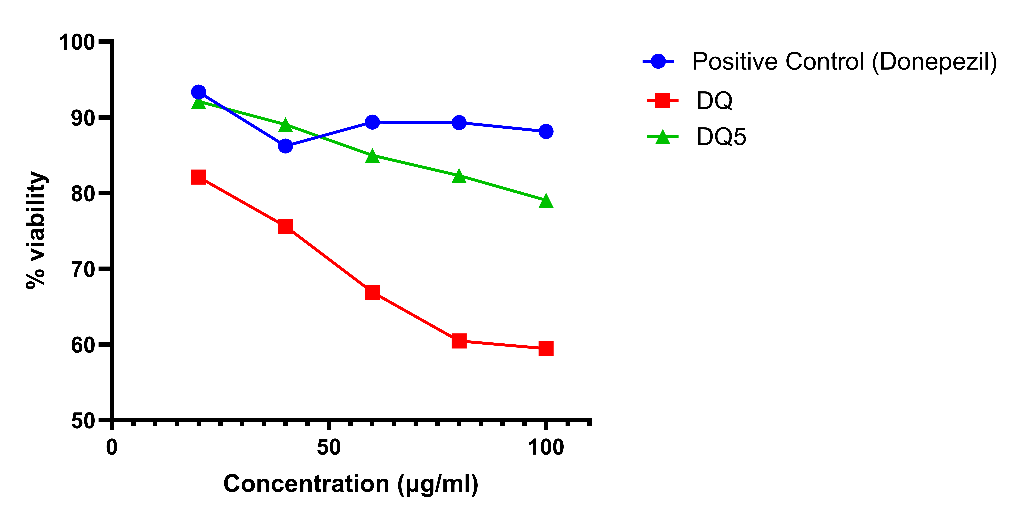

Neuroprotective assay of DQ extract and DQ5 (naringin) in scopolamine-induced neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells

MTT was used on neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells to assess the neuroprotective effect of the DQ extract and DQ5 (naringin) [72]. Scopolamine concentration (2 mmol) and exposure time (24 h) used in our SH-SY5Y model, scopolamine-induced oxidative stress, ROS elevation, and neuronal damage. The viability of cells was evaluated at concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 μg/ml. DQ5 showed a high percentage of viability against scopolamine-induced neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells compared to positive control. Based on the percentage of viability, we can conclude that DQ5 (naringin) shows good neuroprotective action (fig. 13).

Fig. 12: In vitro studies data of DQ5 (naringin), Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Test (standard-Donepezil); MAO-B Inhibitory Test (standard-Selegiline); Tyrosinase Inhibitory Test (standard-Kojic acid); Hydrogen Peroxide Free Radical Scavenging Effects (standard-Ascorbic acid). value were expressed in mean± Standard error of the mean(n=4) one‑way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post‑hoc test. AChE: p = 0.008 p< 0.05). MAO‑B: p = 0.13 (not significant; p ≥ 0.05) Tyrosinase: p = 0.002. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity: p = 0.002

Fig. 13: Neuroprotective assay of DQ extract and DQ5 (naringin), value were expressed in mean± Standard error of the mean (n=3. one‑way ANOVA: cell viability p = 0.001. Tukey's HSD post‑hoc tests: DQ5 significant (p<0.05), and DQ extract not differ significantly. Donepezil is the positive control

ROS assay in SH-SY5Y cells treated with scopolamine and test compounds

SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were seeded and treated with 1 mmol scopolamine to induce oxidative stress, in the presence or absence of test compounds DQ and DQ5. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the culture media were removed, and the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) to eliminate residual media and unbound compounds. Subsequently, 10 μM of 2',7'-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) was added to each well, and the cells were incubated again at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark. DCFH-DA is a non-fluorescent probe that is converted into the highly fluorescent compound 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) upon oxidation by intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). After incubation, the fluorescence intensity of DCF was measured using a microplate reader at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 535 nm. ROS levels were quantified [72], and the percentage inhibition of ROS generation by DQ and DQ5 was calculated relative to the scopolamine-treated group. The results were used to evaluate the antioxidant and potential neuroprotective effects of DQ and DQ5.

As shown in fig. S1, Scopolamine treatment significantly increased intracellular ROS levels (59±0.88%) compared to the control group (22±0.77%, P<0.01), indicating the induction of oxidative stress. Treatment with DQ (34±0.69%) and DQ5 (51±0.79%) significantly reduced ROS levels compared to the scopolamine group (P<0.01 for both), suggesting that both compounds exhibit antioxidant activity. All values are presented as mean±SEM (n = 3), and statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. These findings suggest that DQ5, being a more active fraction, possesses potent antioxidant activity and may offer enhanced neuroprotection by mitigating oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y neuronal cells.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the study highlights the potential of DQ extract and its main phytoconstituent naringin as a promising multitarget natural therapeutic agent for Alzheimer's disease. The extract and naringin demonstrated significant inhibitory effects on AChE, MAO-B, tyrosinase, and Prdx-5, critical enzymes implicated in the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. The in silico findings, particularly the strong docking interactions of DQ5 (naringin) with AChE, MAO-B, tyrosinase, and Prdx-5, suggested that DQ5 (naringin) plays a pivotal role in the extract's bioactivity. Molecular dynamics simulations further confirmed the stability of DQ5’s (naringin) binding interactions, aligning with the molecular docking predictions. The pharmacophore modelling analysed the pharmacophoric features responsible for biological action for the best-docked complex DQ5/6O4W. DQ5 (naringin) is a geometrically optimised molecule revealed by DFT theory. Its low HOMO-LUMO gap indicates its reactivity, possibly contributing to its biological activity. The pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles revealed the extract's potential for safe therapeutic use, with minimal promiscuity and favourable neuroprotective properties. DQ5 (naringin) inhibitory potential was also determined experimentally and found to be very promising against three enzymes, AchE, MAO-B and tyrosinase, as well as against hydrogen peroxide. MTT assay results on neuroblastoma scopolamine-induced SH-SY5Y cells showed that the extract and DQ5 (naringin) exhibited neuroprotective action, with DQ5 demonstrating a higher percentage of viability against SH-SY5Y cells. The multitargeting capability of the DQ extract and DQ5 (naringin) supports its use in modulating multiple pathways involved in AD progression. These findings align with traditional uses of DQ in herbal medicine, where it has been employed for its neuroprotective and antioxidative properties. Further studies, including in vivo and clinical trials, are needed to validate these promising results and fully explore the therapeutic potential of this natural extract in treating Alzheimer's disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to acknowledge Nitte Deemed to be University, NGSM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Mangaluru, Karnataka, for providing access to resources from the NGSMIPS CADD Lab, which has advanced their research in computational drug design and discovery.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization S. T. J and J. P. J; Methodology S. T. J, J. P. J. Z. F. C and S. G. A; Validation and formal analysis R. V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this article.

REFERENCES

Mitrushina M, Fuld PA. Neuropsychological characteristics of early Alzheimer disease. In: Becker RE, Giacobini E, editors. Alzheimer disease. Boca Raton: CRC Press. 2020. p. 77-103. doi: 10.1201/9781003067665-8.

Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 y. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8(6):595-608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210, PMID 27025652.

De Paula VJ, Radanovic M, Diniz BS, Forlenza OV. Alzheimer’s disease. Subcell Biochem. 2012;65:329-52. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5416-4_14, PMID 23225010.

Breijyeh Z, Karaman R. Comprehensive review on Alzheimer’s disease: causes and treatment. Molecules. 2020;25(24):5789. doi: 10.3390/molecules25245789, PMID 33302541.

Zhang P, Xu S, Zhu Z, Xu J. Multi-target design strategies for the improved treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;176:228-47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.020, PMID 31103902.

Sofowora A, Ogunbodede E, Onayade A. The role and place of medicinal plants in the strategies for disease prevention. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2013;10(5):210-29. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i5.2, PMID 24311829.

Halberstein RA. Medicinal plants: historical and cross-cultural usage patterns. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(9):686-99. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.02.004, PMID 15921929.

Garcia S. Pandemics and traditional plant-based remedies. A historical-botanical review in the era of COVID-19. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:571042. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.571042, PMID 32983220.

Suntar I. Importance of ethnopharmacological studies in drug discovery: role of medicinal plants. Phytochem Rev. 2020;19(5):1199-209. doi: 10.1007/s11101-019-09629-9.

Prasanna G, Chitra M. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of Drynaria quercifolia rhizome. Res J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2015;7(1):6. doi: 10.5958/0975-4385.2015.00002.3.

Aparna G, Sree Parvathy S, Radhika C. Drynaria quercifolia Linn. J. smith a review on ethnomedicinal uses and phytochemical constituents. KJA. 2022;1(2). doi: 10.55718/kja.120.

Schliebs R, Arendt T. The cholinergic system in aging and neuronal degeneration. Behav Brain Res. 2011;221(2):555-63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.11.058, PMID 21145918.

Markesbery WR. Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23(1):134-47. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00629-6, PMID 9165306.

Jin W, Stehbens SJ, Barnard RT, Blaskovich MA, Ziora ZM. Dysregulation of tyrosinase activity: a potential link between skin disorders and neurodegeneration. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2024;76(1):13-22. doi: 10.1093/jpp/rgad107, PMID 38007394.

Ferreira Vieira TH, Guimaraes IM, Silva FR, Ribeiro FM. Alzheimer’s disease: targeting the cholinergic system. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016 Jan 22;14(1):101-15. doi: 10.2174/1570159x13666150716165726, PMID 26813123.

Stanciu GD, Luca A, Rusu RN, Bild V, Beschea Chiriac SI, Solcan C. Alzheimer’s disease pharmacotherapy in relation to cholinergic system involvement. Biomolecules. 2019;10(1):40. doi: 10.3390/biom10010040, PMID 31888102.

Iannitelli AF, Hassanein L, Tish MM, Mulvey B, Blankenship HE, Korukonda A. Tyrosinase induced neuromelanin accumulation triggers rapid dysregulation and degeneration of the mouse locus coeruleus. bioRxiv. 2023 Mar 10. doi: 10.1101/2023.03.07.530845, PMID 36945637.

Moreno Garcia A, Kun A, Calero M, Calero O. The neuromelanin paradox and its dual role in oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(1):124. doi: 10.3390/antiox10010124, PMID 33467040.

Krapfenbauer K, Engidawork E, Cairns N, Fountoulakis M, Lubec G. Aberrant expression of peroxiredoxin subtypes in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. 2003;967(1-2):152-60. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04243-9, PMID 12650976.

Poynton RA, Hampton MB. Peroxiredoxins as biomarkers of oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840(2):906-12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.08.001, PMID 23939310.

Park JH, Ju YH, Choi JW, Song HJ, Jang BK, Woo J. Newly developed reversible MAO-B inhibitor circumvents the shortcomings of irreversible inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Adv. 2019;5(3):eaav0316. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav0316, PMID 30906861.

Yang D. Gu sui bu (Rhizoma drynariae) a good drug for senile dementia. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25(4):290-1. PMID 16447673.

Park SY, Kim HS, Hong SS, Sul D, Hwang KW, Lee D. The neuroprotective effects of traditional oriental herbal medicines against β-amyloid-induced toxicity. Pharm Biol. 2009;47(10):976-81. doi: 10.1080/13880200902967987.

Yang ZY, Kuboyama T, Kazuma K, Konno K, Tohda C. Active constituents from Drynaria fortunei rhizomes on the attenuation of Aβ(25-35) induced axonal atrophy. J Nat Prod. 2015;78(9):2297-300. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00290, PMID 26299900.

Yang Z, Kuboyama T, Tohda C. A systematic strategy for discovering a therapeutic drug for Alzheimer’s disease and its target molecule. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:340. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00340, PMID 28674493.

Ferdous R, Islam MB, Al Amin MY, Dey AK, Mondal MO, Islam MN. Anticholinesterase and antioxidant activity of Drynaria quercifolia and its ameliorative effect in scopolamine induced memory impairment in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;319(1):117095. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.117095, PMID 37634747.

Ramesh N, Viswanathan MB, Saraswathy A, Balakrishna K, Brindha P, Lakshmanaperumalsamy P. Phytochemical and antimicrobial studies on Drynaria quercifolia. Fitoterapia. 2001;72(8):934-6. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(01)00342-2, PMID 11731121.

James P, Crasta L, Shetty V, Jyothi D, Jouhara M, Fathima CZ. Tyrosinase and peroxiredoxin inhibitory action of ethanolic extracts of memecylon malabaricum leaves. Res J Pharm Technol. 2024;17(4):1763-70. doi: 10.52711/0974-360X.2024.00280.

Gerlits O, Ho KY, Cheng X, Blumenthal D, Taylor P, Kovalevsky A. A new crystal form of human acetylcholinesterase for exploratory room-temperature crystallography studies. Chem Biol Interact. 2019;309:108698. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.06.011, PMID 31176713.

Johnson S, Tan L, Van Der Veen S, Caesar J, Goicoechea De Jorge E, Harding RJ. Design and evaluation of meningococcal vaccines through structure based modification of host and pathogen molecules. PLOS Pathog. 2012;8(10):e1002981. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002981, PMID 23133374.

Sindhu TJ, James JP, Babu MS, Zakiya Fathima C, Sheqi A. Design molecular docking synthesis and in vitro evaluation of semicarbazide thiazolidinone derivatives as acetylcholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibitors. Rasayan J Chem. 2025;18(2):1034-41. doi: 10.31788/RJC.2025.1829234.

Declercq JP, Evrard C, Clippe A, Stricht DV, Bernard A, Knoops B. Crystal structure of human peroxiredoxin 5, a novel type of mammalian peroxiredoxin at 1.5 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2001;311(4):751-9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4853, PMID 11518528.

Varghese SS, Mathews SM. A simulation approach for novel 1, 3, 4 thiadiazole acetamide moieties as potent antimycobacterial agents. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2024;16(7):40-7. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2024v16i7.51356.

Sindhu TJ, James JP, Zakiya Fathima C, Mathew B, Kumar S. Mechanistic insights into thiazolidinones as anticholinesterase agents: 3D QSAR pharmacophore modeling molecular docking MD simulations and DFT studies for Alzheimer’s therapy. J Comput Biophys Chem. 2025;24(10):1415-40. doi: 10.1142/S2737416525500309.

James JP, Bhat I, Jose N. Synthesis in silico physicochemical properties and biological activities of some pyrazoline derivatives. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(4):456-9. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i4.17093.

James JP, Aiswarya TC, Priya SN, Jyothi DI, Dixit SR. Structure based multitargeted molecular docking analysis of pyrazole condensed heterocyclics against lung cancer. Int J Appl Pharm. 2021;13(6):157-69. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2021v13i6.42801.

Shehab WS, Haikal HA, Elsayed DA, El Farargy AF, El Gazzar AB, El Bassyouni GT. Pharmacokinetic and molecular docking studies to pyrimidine drug using Mn3O4 nanoparticles to explore potential anti-Alzheimer activity. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):15436. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-65166-2, PMID 38965280.

Cardoso R, Valente R, Souza Da Costa CH, Da S Goncalves Vianez JL, Santana Da Costa K, De Molfetta FA. Analysis of kojic acid derivatives as competitive inhibitors of tyrosinase: a molecular modeling approach. Molecules. 2021;26(10):2875. doi: 10.3390/molecules26102875, PMID 34066283.

Aldahish A, Balaji P, Vasudevan R, Kandasamy G, James JP, Prabahar K. Elucidating the potential inhibitor against type 2 diabetes mellitus associated gene of GLUT4. J Pers Med. 2023 Apr 12;13(4):660. doi: 10.3390/jpm13040660, PMID 37109046.

Fathima CZ, James JP, Srinivasa MG, TJS, BM MJ, Revanasiddappa BC. Investigating multitarget potential of mucuna pruriens against Parkinson’s disease: insights from molecular docking MMGBSA, pharmacophore modelling MD simulations and ADMET analysis. Int J Appl Pharm. 2024;16(5):176-93. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i5.51474.

Nickel J, Gohlke BO, Erehman J, Banerjee P, Rong WW, Goede A. Super pred: update on drug classification and target prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W26-31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku477, PMID 24878925.

Mandal A, Nath Talapatra S. Toxicity prediction of selected phytochemicals of Hatisur weed (Heliotropium indicum Linnaeus) and synthetic medicines: an in silico approach by using ProTox-II tool. Int J Sci Eng Res. 2024;13(5):685-9. doi: 10.21275/SR24511152406.

James JP, Sasidharan P, Mandal SP, Dixit SR. Virtual screening of alkaloids and flavonoids as acetylcholinesterase and MAO-B inhibitors by molecular docking and dynamic simulation studies. Polycyclic Aromat Compd. 2023;43(6):5453-77. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2022.2102662.

Sivashanmugam M, KN S, VU. Virtual screening of natural inhibitors targeting ornithine decarboxylase with pharmacophore scaffolding of DFMO and validation by molecular dynamics simulation studies. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019;37(3):766-80. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1439772, PMID 29436980.

Fathima CZ, James JP, Dwivedi PS, Sindhu TJ. Molecular docking pharmacophore modeling 3D QSAR, molecular dynamics simulation and MMPBSA studies on hydrazine linked thiazole analogues as MAO-B inhibitors. J Comput Biophys Chem. 2025;24(6):709-32. doi: 10.1142/S2737416524500790.

James JP, Devaraji V, Sasidharan P, Pavan TS. Pharmacophore modeling 3D QSAR, molecular dynamics studies and virtual screening on pyrazolopyrimidines as anti-breast cancer agents. Polycyclic Aromat Compd. 2023;43(8):7456-73. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2022.2135545.

Ranade SD, Alegaon SG, Khatib NA, Gharge S, Kavalapure RS, Kumar BR. Design synthesis molecular dynamic simulation DFT analysis computational pharmacology and decoding the antidiabetic molecular mechanism of sulphonamide-thiazolidin-4-one hybrids. J Mol Struct. 2024;1311:138359. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.138359.

Lalam DR. Antimicrobial and phytochemical analysis of methanolic leaf extracts of Terminalia catappa against some human pathogenic bacteria. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2020;9(1):1200-4. doi: 10.22271/phyto.2020.v9.i1t.10621.

Sasidharan S, Chen Y, Saravanan D, Sundram KM, Yoga Latha L. Extraction isolation and characterization of bioactive compounds from plants extracts. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2011;8(1):1-10. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i1.60483, PMID 22238476.

Pati UK, Chowdhury A. A comparison of phytotoxic potential among the crude extracts from Parthenium hysterophorus L. extracted with solvents of increasing polarity. Int Lett Nat Sci. 2015 Jan 27;33:73-81. doi: 10.56431/p-311s61.

Kamil Hussain M, Saquib M, Faheem Khan M. Techniques for extraction isolation and standardization of bio-active compounds from medicinal plants. In: Swamy MK, Akhtar MS, editors. Natural bio-active compounds. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2019. p. 179-200. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-7205-6_8.

Nawaz H, Shad MA, Rehman N, Andaleeb H, Ullah N. Effect of solvent polarity on extraction yield and antioxidant properties of phytochemicals from bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) seeds. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2020;56(3). doi: 10.1590/s2175-97902019000417129.

Danlami JM, Arsad A, Zaini MA. Characterization and process optimization of castor oil (Ricinus communis L.) extracted by the soxhlet method using polar and non-polar solvents. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2015;47:99-104. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2014.10.012.

Sujin RM, Jeeva S, Subin RM. Phytochemical and pharmacological studies of oak leaf fern Drynaria quercifolia (L.) J. Sm.: a review. In: The phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of Ethnomedicinal plants. Boca Raton: Apple Academic Press; 2021. p. 373-87. doi: 10.1201/9781003100768-15.

Nithin MK, Veeramani G, Sivakrishnan S. Phytochemical screening and GC-MS analysis of rhizome of Drynaria quercifolia. Res J Pharm Technol. 2020;13(5):2266. doi: 10.5958/0974-360X.2020.00408.4.

Cook RP. Reactions of steroids with acetic anhydride and sulphuric acid (the Liebermann-Burchard test). Analyst. 1961;86(1023):373. doi: 10.1039/an9618600373.

Watson R, Wright S. The cardiac glycosides of Gomphocarpus fruticosus R. Br. II. Gomphoside. Aust J Chem. 1957;10(1):79. doi: 10.1071/CH9570079.

Ohta M, Iwasaki M, Kouno K, Ueda Y. Mechanism of the Molisch reaction. Chem Pharm Bull. 1985;33(7):2862-5. doi: 10.1248/cpb.33.2862.

Pavan TS, James JP, Dwivedi SR, Priya S, Fathima C Z, Sindhu TJ. Synthesis molecular docking and molecular dynamic studies of Thiazolidineones as acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. Polycyclic Aromat Compd. 2024;44(5):3387-407. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2023.2233666.

Yi C, Liu X, Chen K, Liang H, Jin C. Design synthesis and evaluation of novel monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors with improved pharmacokinetic properties for Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;252:115308. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115308, PMID 37001389.

Hazra B, Biswas S, Mandal N. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity of Spondias pinnata. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:63. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-63, PMID 19068130.

Puangmalai N, Thangnipon W, Soi Ampornkul R, Suwanna N, Tuchinda P, Nobsathian S. Neuroprotection of N-benzylcinnamide on scopolamine induced cholinergic dysfunction in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12(9):1492-8. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.215262, PMID 29089996.

Javed MA, Bibi S, Jan MS, Ikram M, Zaidi A, Farooq U. Diclofenac derivatives as concomitant inhibitors of cholinesterase monoamine oxidase cyclooxygenase-2 and 5-lipoxygenase for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: synthesis pharmacology toxicity and docking studies. RSC Adv. 2022;12(35):22503-17. doi: 10.1039/d2ra04183a, PMID 36105972.

Panzella L, Napolitano A. Natural and bioinspired phenolic compounds as tyrosinase inhibitors for the treatment of skin hyperpigmentation: recent advances. Cosmetics. 2019;6(4):57. doi: 10.3390/cosmetics6040057.

Tan JB, Lim YY. Antioxidant and tyrosinase inhibition activity of the fertile fronds and rhizomes of three different Drynaria species. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):468. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1414-3, PMID 26395256.

Olszowy M. What is responsible for antioxidant properties of polyphenolic compounds from plants? Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;144:135-43. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.09.039, PMID 31563754.

Kanagalatha R, Chinnusamy G. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its antimicrobial antioxidant activity of Drynaria quercifolia. Int J Life Sci Pharm Res. 2022;12(2):37-44. doi: 10.22376/ijpbs/lpr.2022.12.2.

Choi GY, Kim HB, Hwang ES, Park HS, Cho JM, Ham YK. Naringin enhances long-term potentiation and recovers learning and memory deficits of amyloid-beta induced Alzheimer’s disease like behavioral rat model. Neurotoxicology. 2023;95:35-45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2022.12.007, PMID 36549596.

Jainey PJ, Ishwar BK. Microwave assisted synthesis of novel pyrimidines bearing benzene sulfonamides and evaluation of anticancer and antioxidant activities. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2014;7(4):111-4.

Ahmed S, Khan H, Aschner M, Hasan MM, Hassan ST. Therapeutic potential of naringin in neurological disorders. Food Chem Toxicol. 2019;132:110646. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.110646, PMID 31252025.

Oladapo OM, Ben Azu B, Ajayi AM, Emokpae O, Eneni AO, Omogbiya IA. Naringin confers protection against psychosocial defeat stress induced neurobehavioral deficits in mice: involvement of glutamic acid decarboxylase Isoform-67, Oxido-Nitrergic stress and neuroinflammatory mechanisms. J Mol Neurosci. 2021;71(3):431-45. doi: 10.1007/s12031-020-01664-y, PMID 32767187.

Mani S, Sekar S, Chidambaram SB, Sevanan M. Naringenin protects against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium induced neuroinflammation and resulting reactive oxygen species production in SH-SY5Y cell line: an in vitro model of Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacogn Mag. 2018;14:(57s):s458-64. doi: 10.4103/pm.pm_23_18.