Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 2, 30-34Original Article

DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY OF COMBINED MAMMOGRAPHY AND ULTRASONOGRAPHY IN BREAST MALIGNANCY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS IN WESTERN RAJASTHAN POPULATION

YOGESH SONAGARA*, RAJENDRA KUMAR CHAUDHARY, KIRTI CHATURVEDY, SAMTA BUDANIA

Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dr. Sampurnanand Medical College, Jodhpur, Rajasthan-342003, India

*Corresponding author: Yogesh Sonagara; *Email: sonagarayogesh1996@gmail.com

Received: 13 Dec 2024, Revised and Accepted: 24 Feb 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The breast cancer is a serious health concern for women that is receiving more attention due to its rising incidence and mortality. In the past 26 y, every state in the US has seen a rise in the age-standardized incidence rate of breast cancer in females, which rose by markedly in last 20 y.

Methods: A total of 100 female patients above 30 y age referred from out-patient for routine breast screening (BIRAD 2 or above), with or without lump or nodularity in the breast, with complaint of pain in the breast and history of nipple discharge were recruited into this prospective study. Ultrasonography and mammography BIRADS were performed and correlated with histology findings. This study was performed in the radiodiagnosis department at a tertiary care center in Western Rajasthan.

Results: The mean age of study participants was 46.9 y±10.52. Majority of the patients belonged to 41-50 year age group (40%). Out of 100 patients, 32% females had family history of breast cancer. The false negative rate of mammography and ultrasonography was 3% and 9%, respectively with highest percentage in 41-50 y age group (7.5%). The combined sensitivity of mammography and ultrasound (93.94%) was higher than individual techniques.

Conclusion: Combining ultrasonography and mammography findings improves cancer detection in screening of women at risk for breast cancer. The higher imaging BI-RADS classification grade showed a positive predictive value in detecting breast malignancy.

Keywords: BI-RADS, Breast lump, Mammography, Histology

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i2.6051 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer, a major women’s health issue, has been gaining attention as its incidence and mortality are rising, comprising the fifth leading cause of cancer mortality. Even with adjuvant chemotherapy, the five-year survival rate for metastatic breast cancer is less than 30%. Globally, there were predicted to be 2.3 million (11.7%) new cases and 684,996 (6.9%) fatalities in 2020. Estimates from 2012 place the number of Asian women with breast cancer at 21.2%; by 2020 that number had risen to 22.9% [1]. According to Globocan statistics 2020, 10.6% (90408) of all fatalities in India and 13.5% (178361) of all cancer cases were related to breast cancer [2].

Compared to all the women undergoing breast imaging, women who come with palpable breast lumps had a greater chance of having cancer [3]. A movement towards comparatively earlier presentation in the stages of breast cancer is the result of advancements in health infrastructure, high-resolution ultrasound (USG) devices, full-field digital mammography, and awareness. A methodical "Triple assessment" that combines radiological imaging, histological correlation, and clinical examination is used to evaluate breast complaints [4].

The most recent iteration of the American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria, the evaluation of women aged 30 to 39 y old might commence with either mammography or ultrasonography for palpable breast masses; nevertheless, mammography was the conventionally advised method earlier [5]. Using a uniform lexion, the results seen on MG and USG are interpreted. The majority of nations in the world adhere to the American College of Radiology's "Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS)" evaluation categories [6].

In the present study, we are trying to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of combined mammography and ultrasonography and their BIRADS in distinguishing lesions considering histopathology as gold standard among females of Western Rajasthan, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present prospective study was conducted in the Department of Radio-diagnosis, Dr S. N. Medical College, Jodhpur and associated group of hospitals. After obtaining written informed consent, female patients (over 30 y old) referred for routine breast screening (BIRAD 2 or above), with or without lump or nodularity in the breast, with complaint of pain in the breast and history of nipple discharge who from the outpatient department of Mathura Das Mathur Hospital and Mahatma Gandhi Hospital were recruited into the study. The study excluded women who were pregnant, had a bleeding disorder, or had a documented case of breast cancer (BIRADS 6). A total of 100 patients were recruited into the study.

Two to three cores were taken and fixed in buffered formalin and all were processed. The mammography and USG were conducted by the same radiologist. Following imaging, all patients had Trucut biopsies performed by the same radiologist using image guidance, and the tissue samples were sent to the pathology section for histological evaluation.

Statistical analysis

The categorical variables were described in numbers and percentages (%), and continuous variables as means. Differences in diagnostic methods were analyzed using Chisquare test or Fisher’s exact test wherever applicable. Accuracy was determined as the proportion of true positive (TP)+true negative (TN). Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) was used to determine the ability of mammography, sonography, as well as mammography and sonography, combined to predict malignancy using area under the curve (AUC). All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26. P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

The present study was approved by Institutional Ethics committee, Dr. Sampurnan and Medical College, Jodhpur, India. Reference No.: SNMC/IEC/2023/Plan/710. Dated: 18.05.2023.

RESULTS

The present study was conducted in the Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dr. Smapurnanand Medical College and associated Hospitals, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

A total of 100 females above the age of 30 y, were recruited into the study. mean age was 46.9 y±10.52. Majority of the patients were from 41-50 y age-group (40%), followed by 30-40 age-group (38%), 51-60 age-group (12%) and above 60 y (10%). Out of 100 patients, 32% females had family history of breast cancer.

The false negative rate of mammography and ultrasonography was 3% and 9%, respectively. The false negativity was mainly associated with 41-50 y age group (7.5%), no family history of breast cancer (4.41%), inner quadrants of breast (15.88%), class-C breast density (6.25%), equal mammography density (10%), pleomorphic calcification (11.76%), normal overlying skin (3.53%), and no evidence of nipple retraction (3.33%). The mammography showed no false negative cases above 60 y age group only. The false negative occurrence was common among women with hypoechoic lesion (14.06%), overlying skin retraction (14.29%) and lumps without evidence of muscle invasion (9.78%) table 1, table 2.

Table 1: Univariate analysis: comparison of mammography with histopathology

| Tumour characteristics (N) | Histopathology (Total positive: 33) | P value | |

| TP, N(%) | FN, N(%) | ||

| Age | |||

| 30-40 (38) | 5 (13.16) | 0 (0.0) | p= 0.265816 |

| 41-50 (40) | 12 (30.0) | 3 (7.5) | |

| 51-60 (12) | 8 (66.67) | 0 (0.0) | |

| >60 (10) | 5 (50) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Family history of breast cancer | |||

| Yes (32) | 14 (43.75) | 0 (0.0) | p= 0.118913 |

| No (68) | 16 (23.53) | 3 (4.41) | |

| Location | |||

| Central (27) | 12 (44.44) | 0 (0.0) | p= 0.580625 |

| LIQ (10) | 5 (50.0) | 1 (10.0) | |

| LOQ (6) | 3 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| UIQ (17) | 4 (23.53) | 1 (5.88) | |

| UOQ (40) | 6 (15.0) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Shape | |||

| Oval (58) | 14 (24.14) | 2 (3.45) | p= 0.50869 |

| Round (42) | 16 (38.1) | 1 (2.38) | |

| Margin | |||

| Well circumscribed (63) | 7 (11.11) | 1 (1.59) | p= 0.577206 |

| Indistinct (16) | 11 (68.75) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Micro-lobulated (12) | 4 (33.33) | 1 (8.33) | |

| Spiculated (9) | 8 (88.89) | 1 (11.11) | |

| Class of breast density | |||

| A (23) | 15 (65.22) | 0 (0.0) | p= 0.09469 |

| B (44) | 10 (22.73) | 1 (2.27) | |

| C (32) | 5 (15.63) | 2 (6.25) | |

| D (1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mammography density | |||

| Equal (10) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (10.0) | p= 0.12555 |

| Low (3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| High (87) | 28 (32.18) | 2 (2.3) | |

| Calcification | |||

| Amorphous (10) | 4 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | p= 0.673359 |

| Coarse (1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Pleomorphic (17) | 13 (76.47) | 2 (11.76) | |

| None (72) | 13 (18.06) | 1 (1.39) | |

| Overlying skin | |||

| Retraction (4) | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | p= 0.342152 |

| Thickening (11) | 9 (81.82) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Normal (85) | 17 (20.0) | 3 (3.53) | |

| Nipple retraction | |||

| Yes (10) | 9 (90.0) | 0 (0.0) | p= 0.265953 |

| No (90) | 21 (23.33) | 3 (3.33) |

Table 5 shows how well sonography and mammography diagnose patients when compared to biopsy results, which served as the study's gold standard. According to the CNB histology results, 33 (33%) and 67 (67%) of the tumors were malignant. The most important finding is that the combined sensitivity of mammography and ultrasound (93.94%) was far higher than the sensitivity of the two imaging modalities used independently (mammography: 90.91%; USG: 72.73%). However, when compared to the distinct individual specificity of either ultrasound (95.52%) or mammography (82.09%) alone, the combined specificity (80.60%) of ultrasound and mammography was somewhat lower [table 5].

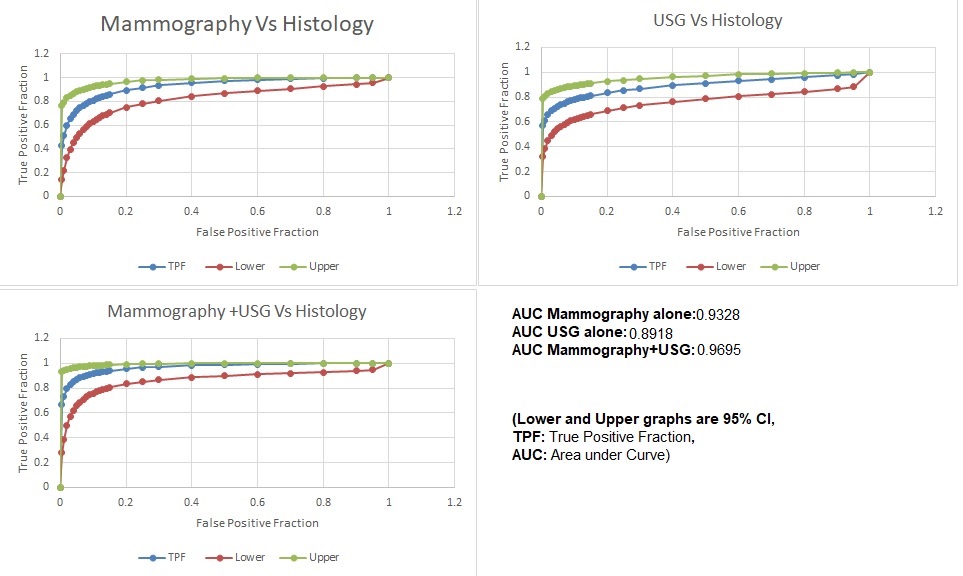

When ROC analysis was done in predicting breast malignancy, the combined predictive ability of mammography plus ultrasound (AUC=0.9695) was higher than that of mammography alone (AUC=0.9328) as well as ultrasound alone (AUC=0.8918) [fig. 1].

Table 2: Univariate analysis: comparison of ultrasonography with histopathology

| Tumour characteristics | Histopathology (total positive: 33) | P value | |

| TP, n(%) | FN, n(%) | ||

| Age (N) | |||

| 30-40 (38) | 2 (5.26) | 3 (7.89) | p= 0.203661 |

| 41-50 (40) | 11 (27.5) | 4 (10.0) | |

| 51-60 (12) | 6 (50.0) | 2 (16.67) | |

| >60 (10) | 5 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Family history of breast cancer | |||

| Yes (32) | 10 (31.25) | 4 (12.5) | p= 0.88566 |

| No (68) | 14 (20.59) | 5 (7.35) | |

| Shape | |||

| Oval (56) | 12 (21.43) | 4 (7.14) | p= 0.77611 |

| Round (44) | 12 (27.27) | 5 (11.36) | |

| Margin | |||

| Well circumscribed (54) | 1 (1.85) | 3 (5.56) | p= 0.04399* |

| Indistinct (18) | 9 (50.0) | 1 (5.56) | |

| Micro-lobulated (19) | 6 (31.58) | 4 (21.05) | |

| Spiculated (9) | 8 (88.89) | 1 (11.11) | |

| USG Echogenicity | |||

| Anechoic (29) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | p= 0.670861 |

| Hyperechoic (3) | 1 (33.33) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hypoechoic (64) | 22 (34.38) | 9 (14.06) | |

| Isoechoic (1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Solid cystic (3) | 1 (33.33) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Overlying skin | |||

| Retraction (7) | 5 (71.43) | 1 (14.29) | p= 0.065621 |

| Thickening (9) | 8 (88.89) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Normal (84) | 11 (13.1) | 8 (9.52) | |

| USG posterior feature | |||

| Posterior enhancement (26) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | p= 0.13397 |

| Posterior shadowing (25) | 15 (60.0) | 3 (12.0) | |

| No (9) | 9 (18.37) | 6 (12.24) | |

Transverse versus anteroposterior diameter ratio>1 |

|||

| Yes (55) | 11 (20.0) | 2 (3.64) | p= 0.21636 |

| No (45) | 13 (28.89) | 7 (15.56) | |

| USG muscle invasion | |||

| Yes (8) | 8 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | p= 0.046594* |

| No (92) | 16 (17.39) | 9 (9.78) |

Table 3: Birads of mammography, USG and combined

| Birads | Mammography N(%) | USG N(%) | Combined N(%) |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) |

| 2 | 44 (44) | 51 (51) | 36 (36) |

| 3 | 14 (14) | 22 (22) | 20 (20) |

| 4 | 24 (24) | 13 (13) | 24 (24) |

| 5 | 18 (18) | 14 (14) | 20 (20) |

BIRADS grading of patients’ breast lump showed combined imaging of mammography and USG was marginally better than individual techniques table 3, table 4

Table 4: Distribution of patients based on BIRADS in comparison to histopathology

| BIRADS | Benign (n=67), (%) | Malignant (n=33), (%) | ||||

| MG | USG | Combined | MG | USG | Combined | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 42 | 46 | 36 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| 3 | 13 | 18 | 18 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| 4 | 11 | 3 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 11 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 14 | 20 |

Tables 5: Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and Accuracy of imaging techniques with histopathology

| Imaging | Sensitivity %, (95% CI) |

Specificity %, (95% CI) |

PPV %, (95% CI) |

NPV %, (95% CI)) |

Accuracy %, (95% CI) |

| Mammography | 90.91%, (95% CI: 95.67%-98.08%) | 82.09%, (95% CI: 70.80%-90.39%) | 71.43%, (95% CI: 59.69%-80.85%) | 94.83%, (95% CI: 86.10%-98.19%) | 85.00%, (95%CI: 76.47%-91.35%) |

| USG | 72.73%, (95% CI: 54.48%-86.70% | 95.52%, (95% CI: 87.47%-99.07%) | 88.89%, (95% CI: 72.19%-96.10%) | 87.67%, (95% CI: 80.25%-92.56%) | 88.00%, (95% CI: 79.98%-93.64%) |

| Mammography+USG | 93.94%, (95% CI: 79.77%-99.26%) | 80.60%, (95% CI: 69.11%-89.24%) | 70.45%, (95% CI: 59.23%-79.65%) | 96.43%, (95% CI: 87.52%-99.05%) | 85.00%, (95% CI: 76.47%-91.35%) |

PPV: Positive predictive value, NPV: Negative predictive value, USG: Ultrasonography.

Fig. 1: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) Curve of mammography, USG, and mammography and USG combined BIRAD category in relation to histology results

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the comparative accuracy of breast ultrasound and mammography combined and, separately, BIRADSs categorisation in women with breast masses.

The sensitivity of detecting breast malignancy by ultrasonography and mammography was found comparable to each other; however, a higher specificity was observed for ultrasonograpy compared to mammography. When the results of both the diagnostic modalities were combined together, the sensitivity and eventually diagnostic accuracy significantly increased. Similar findings have been reported in several studies [7-10]. Therefore, it is better to use both ultrasound and mammography as diagnostic tools to screen women. However, the reduced specificity of these two modalities combined means that they may not accurately rule out breast malignancy, and have also been reported previously [10]. This reduced specificity could be due to the fact that ultrasound can ably identify some lesions which may not be detectable at mammography, especially in very dense breasts.

As found in our result, the sensitivity in detecting malignant lesion was highest by mammography and USG combined (93.94%) but specificity was found to be associated with USG. Similar observation have been noted by Ghaemian et al. [11] Lee et al. [9] and Berg et al. [7]. These findings support that an increased number of women can be diagnosed with breast cancer in early stage if mammography and USG both are used for screening. In our study, although the combined sensitivity was higher for both methods combined but specificity decreased (80.6%) in comparison to mammography (82.09%) or USG (95.52%) alone, similar finding was seen in studies conducted worldwide [7, 9, 11]. Although, many studies support that adding USG to mammography increase the sensitivity, but the studies have found comparably low positive predictive values or high negative predictive values [8].

Although, the current guidelines recommend to screen all women above 40 y by mammography, but women with dense breast may not get detected further women with dense breast are more prone to develop breast cancer [12, 13].

In the present study, we evaluated the BIRADS classification of mammography, USG and both imaging techniques combined. The BI-RADS system have been found useful in distinguishing benign and malignant masses in several studies, but its accuracy is still debatable [14, 15]. Apart from imaging techniques, several patient-related factors such as age, previous breast surgery, lesion characteristics and newer imaging techniques may also affect the accuracy of diagnostic methods [16].

CONCLUSION

Women who are at risk for breast cancer can be screened more effectively for the disease by combining the results of mammography and ultrasound tests. The BI-RADS classification for imaging had shown a positive predictive value for the identification of breast cancer. In most cases, non-invasive diagnostic techniques are accessible, affordable, and effective in helping to diagnose breast lesions.

FUNDING

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the conception or design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data. All authors were involved in drafting and commenting on the paper and have approved the final version.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form and declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

World Health Organization. Breast cancer. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer. [Last accessed on 04 Jan 2024].

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660, PMID 33538338.

Brown AL, Phillips J, Slanetz PJ, Fein Zachary V, Venkataraman S, Dialani V. Clinical value of mammography in the evaluation of palpable breast lumps in women 30 Y old and older. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017 Oct;209(4):935-42. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17088, PMID 28777649.

Joshi P, Singh N, Raj G, Singh R, Malhotra KP, Awasthi NP. Performance evaluation of digital mammography digital breast tomosynthesis and ultrasound in the detection of breast cancer using pathology as gold standard: an institutional experience. Egypt J Rad Nucl Med. 2022 Jan 4;53(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s43055-021-00675-y.

Harvey JA, Mahoney MC, Newell MS, Bailey L, Barke LD, D Orsi C. ACR appropriateness criteria palpable breast masses. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013 Oct;10(10):742-9.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.06.013.

D Orsi CJ, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB, Morris EA. ACR BI-RADS® atlas breast imaging reporting and data system. Reston VA: American College of Radiology; 2013. Available from: https://www.acr.org/clinical-resources/reporting-and-data-systems/bi-rads.

Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, Jong RA, Pisano ED, Barr RG. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2012 Apr 4;307(13):1394-404. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.388, PMID 22474203.

Buchberger W, Geiger Gritsch S, Knapp R, Gautsch K, Oberaigner W. Combined screening with mammography and ultrasound in a population based screening program. Eur J Radiol. 2018 Apr 1;101:24-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.01.022, PMID 29571797.

Lee JM, Arao RF, Sprague BL, Kerlikowske K, Lehman CD, Smith RA. Performance of screening ultrasonography as an adjunct to screening mammography in women across the spectrum of breast cancer risk. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 May;179(5):658-67. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8372, PMID 30882843.

Mubuuke AG, Nassanga R, Galukande M. Comparative accuracy of sonography mammography and the BI-RADS characterization of breast masses among adult women at Mulago Hospital Uganda. J Glob Health Rep. 2023 May 23;7:e2023013. doi: 10.29392/001c.75139.

Ghaemian N, Haji Ghazi Tehrani N, Nabahati M. Accuracy of mammography and ultrasonography and their BI-RADS in detection of breast malignancy. Caspian J Intern Med. 2021;12(4):573-9. doi: 10.22088/cjim.12.4.573, PMID 34820065.

Freer PE. Mammographic breast density: impact on breast cancer risk and implications for screening. Radio Graphics. 2015 Mar;35(2):302-15. doi: 10.1148/rg.352140106, PMID 25763718.

Tagliafico AS, Calabrese M, Mariscotti G, Durando M, Tosto S, Monetti F. Adjunct screening with tomosynthesis or ultrasound in women with mammography negative dense breasts: interim report of a prospective comparative trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jun;34(16):1882-8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4147, PMID 26962097.

Park CJ, Kim EK, Moon HJ, Yoon JH, Kim MJ. Reliability of breast ultrasound BI-RADS final assessment in mammographically negative patients with nipple discharge and radiologic predictors of malignancy. J Breast Cancer. 2016;19(3):308-15. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2016.19.3.308, PMID 27721881.

Heinig J, Witteler R, Schmitz R, Kiesel L, Steinhard J. Accuracy of classification of breast ultrasound findings based on criteria used for BI‐RADS. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Sep;32(4):573-8. doi: 10.1002/uog.5191, PMID 18421795.

LA Forgia D, Fausto A, Gatta G, DI Grezia G, Faggian A, Fanizzi A. Elite VABB 13G: a new ultrasound guided wireless biopsy system for breast lesions. Technical characteristics and comparison with respect to traditional core biopsy 14-16G systems. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10(5):291. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10050291, PMID 32397505.