Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 4, 1-9Review Article

A REVIEW ON TARGETED POLYMERIC NANOPARTICLES: CLASSIFICATION, PREPARATION TECHNOLOGY, BIOSYNTHESIS, CHARACTERIZATION AND APPLICATION IN DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEM

ABHISHEK KUMAR*, BRIJESH SINGH, PREET KAUR

Ashoka Institute of Technology and Management (Pharmacy), Paharia- Sarnath, Varanasi-221007, U. P., India

*Corresponding author: Brijesh Singh; *Email: abhishekkumargupta82@gmail.com, brijesh19feb@gmail.com

Received: 12 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 13 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

The intricacy of certain sicknesses, as well as the innate harmfulness of specific medications, has prompted a rising interest in the turn of events and improvement of medication conveyance frameworks. Polymeric nanoparticles stand apart as a vital tool to further develop drug bioavailability or specific delivery at the site of action. The adaptability of polymers makes them possibly great for satisfying the particular drug-delivery system. Polymeric nanoparticles comprise of an inward part (center) in which the therapeutic substance is contained and encompassed by a polymeric shell. Polymeric nanoparticles have shown extraordinary potential for designated conveyance of medications for the treatment of diseases. Nano medicine gives another medical care worldwide and is equipped for reviving existing clinical items. Polymeric nanoparticles stand apart as a vital tool to further develop drug bioavailability or explicit conveyance at the site of activity. In this review, we examine the most ordinarily involved techniques which are used for the creation and production of polymeric nanoparticles was given also there is the brief illustration about the revision of the use of polymeric nanoparticles for the dermal drug delivery, cosmetics, gene delivery using nanoparticles was carried out, The choice of polymer and the ability to modify drug release from polymeric nanoparticles have made them ideal candidates for nanoparticles. There is a short discussion about the application of nanotechnology used in the field of medicine and the antimicrobial technique used in the application nanotechnology.

Keywords: Nanoparticles, Gene delivery, Polymeric shell, Dermal drug delivery, Nanotechnology and nanomedicine

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i4.6098 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Polymeric nanoparticles are small particles composed of polymers, which are large molecules composed of repeating subunits. These nanoparticles are on the Nano scale, typically 1-100 nanometers in size. They are used in many fields, including medicine, where they can be designed to encapsulate drugs and deliver them to specific locations in the body.

Novel nanotechnology-based drug delivery methods have shown encouraging results in recent years. These systems include dendrimers, liposomes, nanoemulsions, microemulsions, polymeric nanoparticles, lipid nanoparticles, and nanocrystals. They offer various advantages, such as improved drug solubility and stability, flexibility in regulating drug release, improved drug membrane permeability, modifiable surface characteristics, potential for drug targeting, and ease of drug administration through intramuscular, subcutaneous, oral, and intravenous routes [1].

Polymeric nanoparticles are nanoparticles made entirely of polymers. Once the drug has been dissolved, trapped, and encapsulated into nanoparticles, either nanospheres or nanocapsules can be created, depending on the production procedure. The drug is kept in vesicular structures known as nanocapsules, where it is enclosed in a hollow by a polymer membrane. Nanospheres are matrix structures where the medication is evenly and physically dispersed [2].

The basic building block of nanotechnology is nanoparticles (NPs). Particulate matter with at least one dimension less than 100 nm is referred to be a nanoparticle. They may consist of biological materials, metal, metal oxides, or carbon.

The main factors affecting these NPs' physico-chemical characteristics are their variations in size and form. NPs have found significant success in a wide range of applications in several disciplines, including medical, environmental, energy-based research, imaging, chemical and biological sensing, gas sensing, and others, thanks to their unique physical and chemical properties. Since nanotechnology is seen as one of the key components for a sustainable and clean future, researchers are more drawn to it [3].

Classification of nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles can be categorized according to a number of factors, including size, composition, and methods of manufacture. Here's a short outline:

Composition

• Natural Polymers: Those originating from natural sources such as nucleic acids, polysaccharides, or proteins. Gelatin nanoparticles, alginate, and chitosan are a few examples.

• Synthetic Polymers: Polymers created through chemical engineering that provides property control. Polyethylene glycol (PEG), poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), and polystyrene nanoparticles are a few examples.

Size

Particles with a solid polymeric matrix all around are called nanospheres.

• Nanocapsules: Core-shell structures in which an inner core is encased in a polymeric shell.

Methods of preparation

• Techniques for Polymerization: Common techniques include mini-emulsion, dispersion, and emulsion polymerization.

• Solvent Evaporation: The drug and polymer are dissolved in a volatile solvent, and then the solvent evaporates.

• Emulsification-Solvent Diffusion: Emulsifying a polymer solution in an organic solvent into an aqueous phase.

• Coacervation: Separation of a polymer-rich phase from a polymer-poor phase.

Charge

• Cationic Nanoparticles: Positively charged polymers like chitosan, suitable for drug delivery and gene therapy. • Anionic Nanoparticles: Negatively charged polymers, such as alginate, used for controlled release applications.

Surface modification

• Functionalized Nanoparticles: Modified surfaces for specific purposes, like PEGylation to enhance biocompatibility.

Biodegradability

• Biodegradable Nanoparticles: Polymers that undergo degradation into non-toxic byproducts, reducing long-term effects.

Thermo-responsive nanoparticles

• Polymers that respond to temperature changes, altering their properties or releasing encapsulated substances.

Smart nanoparticles

• pH-Sensitive Nanoparticles: Respond to changes in pH, often used for targeted drug delivery in specific tissues.

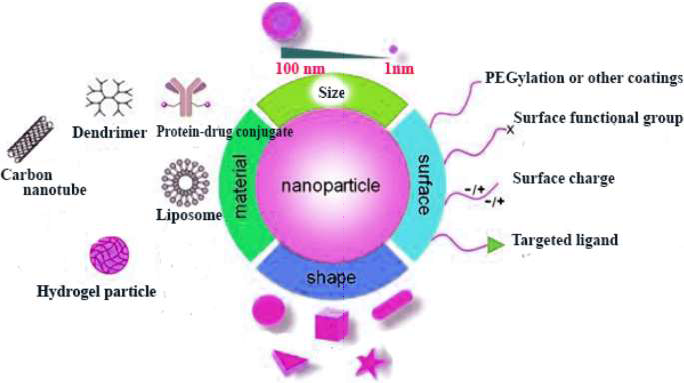

Nanoparticles can be further categorized in a variety of ways, including by their materials, sizes, surfaces, and shapes [4] Example primarily based totally on coating material and based on the use for the study purpose the classification of nanoparticles given in the below fig. 1.

Two categories of nanoparticles exist as follows: Carbon-based nanoparticles (c), Inorganic nanoparticles (b), Organic nanoparticles (c)

1. Inorganic nanoparticles: These are non-carbon-based particles. Inorganic nanoparticles are often defined as those based on metal and metal oxides.

a) Metal-based: Metal-based nanoparticles are created by destructive or constructive means by synthesizing metals into nanometric sizes[6]. The metals aluminum (Al), cadmium (Cd), cobalt (Co), copper (Cu), gold (Au), iron (Fe), lead (Pb), silver (Ag), and zinc (Zn) are frequently utilized in the creation of nanoparticles.

b) Based on metal oxides: The purpose of the synthesis of the metal oxide-based nanoparticles is to alter the characteristics of the corresponding metal-based nanoparticles. The manufacture of metal oxide nanoparticles is primarily motivated by their enhanced reactivity and efficiency. Aluminum oxide (Al2O3), cerium oxide (CeO2), iron oxide (Fe2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), silicon dioxide (SiO2), titanium oxide (TiO2), and zinc oxide (ZnO) are the ones that are most frequently synthesized [7].

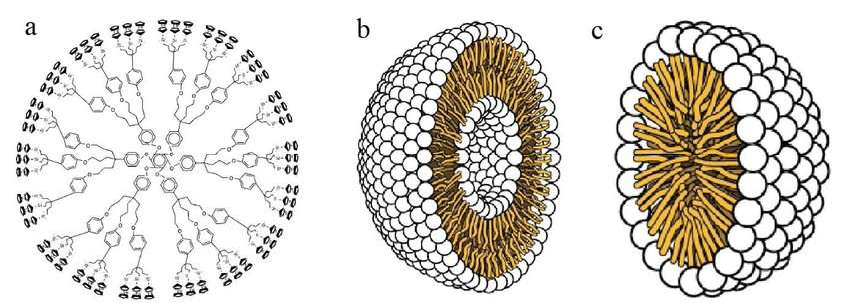

2. Organic nanoparticles: Polymers such as ferritin, liposomes, dendrimers, and micelles are examples of organic nanoparticles as shown in fig. 2. These nanoparticles are harmless and biodegradable. Certain particles, like liposomes and micelles, have hollow cores that make them susceptible to electromagnetic and thermal radiation, including light and heat. These particles are also known as nanocapsules. They are the perfect option for medication delivery because of these special qualities [8].

Fig. 1: Nanoparticle schematic representation [5]

Fig. 2: Dendrimers, liposomes, and micelles are examples of organic nanoparticles [8]

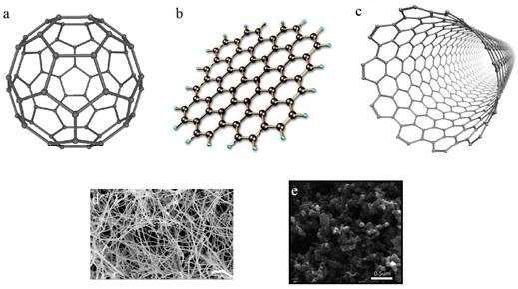

3. Carbon-based: Nanoparticles that are entirely composed of carbon are referred to be carbon-based. Fullerenes, graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), carbon nanofibers, carbon black, and occasionally activated carbon in nanosize can all be categorized under this category [9].

a) Carbon nanotubes (CNTs): CNTs are made of graphenenanofoil, which has a honeycomb lattice of carbon atoms. The CNTs are wound into hollow cylinders to create nanotubes, which can range in length from a few micrometers to several millimeters and have diameters as low as 0.7 nm for single-layered CNTs and 100 nm for multi-layered CNTs. A half-fullerene molecule can shut the ends or leave them hollow.

b) Carbon Nanofiber: Instead of using standard cylindrical tubes, carbon nanofiber is created by winding the same graphene nanoflakes into a cone or cup shape.

c) Fullerenes: Fullerenes, also known as C60, are spherical carbon molecules composed of carbon atoms bound together by sp2 hybridization. The spherical structure of fullerenes, which have diameters of up to 8.2 nm for single layers and 4 to 36 nm for multi-layered fullerenes, is made up of roughly 28 to 1500 carbon atoms as given in fig. 3.

Fig. 3: Various carbon-based nanoparticles, including graphene, fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, carbon nanofibers, and carbon black [9]

Methods of preparation

There are following methods of preparation of nanoparticles.

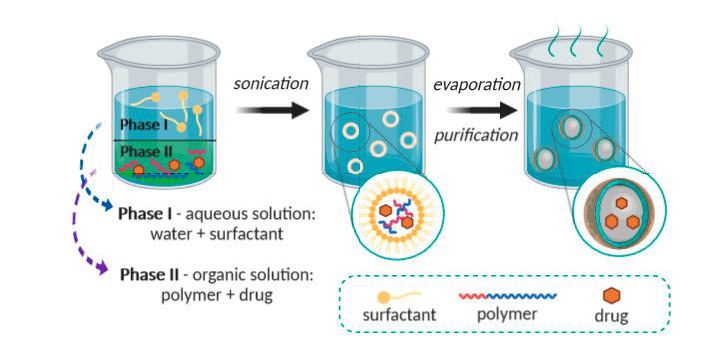

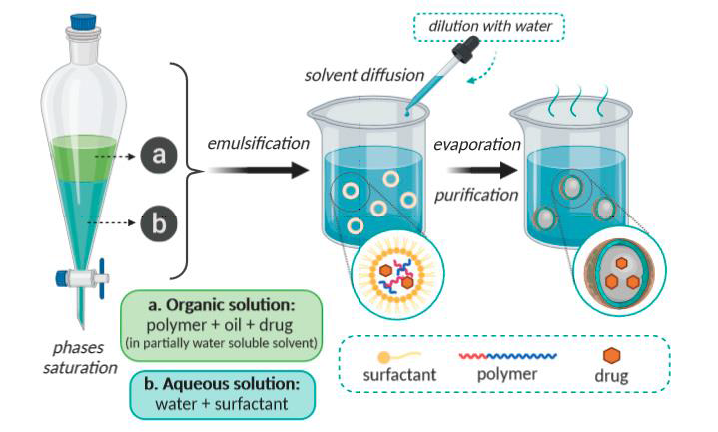

1. Method of solvent evaporation

The technique of solvent evaporation was initially created for nanoparticle preparation [10]. This process involves first preparing the nanoemulsion formulation. Polymer dissolved in an organic solvent (ethyl acetate, dichloromethane, or chloroform). In this solution, the drug is distributed. Then, employing mechanical stirring, sonication, or micro fluidization (high-pressure homogenization through small channels), this mixture emulsified in an aqueous phase containing surfactant (polysorbates, poloxamers, sodium dodecyl sulfates, polyvinyl alcohol, gelatin) creates an oil-in-water emulsion. Following the emulsion's development, the organic solvent evaporates when the temperature is raised and the pressure is lowered while stirring continuously [11-13] as shown in fig. 4.

Fig. 4: Solvent-evaporation technique representation [14]

2. Method of double emulsification

Due to the poor trapping of hydrophilic medicines in emulsification and evaporation methods, double emulsification technique is utilized first, w/o emulsion made by continuously swirling an aqueous drug solution into an organic polymer solution. After creating a second aqueous phase and vigorously swirling it, a w/o/w emulsion was produced, and the organic solvent was extracted using high centrifugation [10].

3. The diffusion method for emulsions

This Leroux et al. technique patent is a modified version of the salting out method. Water was added to a water-miscible solvent solution (such as benzyl alcohol or propylene carbonate) to dissolve the polymer. Emulsification of the polymer-water saturated solvent phase takes place in an aqueous solution with stabilizer. The solvent was then eliminated by filtering or evaporating as shown in fig. 5.

This method's benefits include high encapsulation efficiency (usually 70%), simplicity, ease of scale-up, high batch-to-batch consistency, lack of homogenization, and narrow size distribution. This method's drawbacks include the enormous amounts of water that are reportedly required to be removed from the suspension and the water-soluble medication that leaks into the saturated aqueous external phase during emulsification, which lowers the effectiveness of encapsulation [10-12].

Fig. 5: Representation of the emulsification-diffusion technique [13]

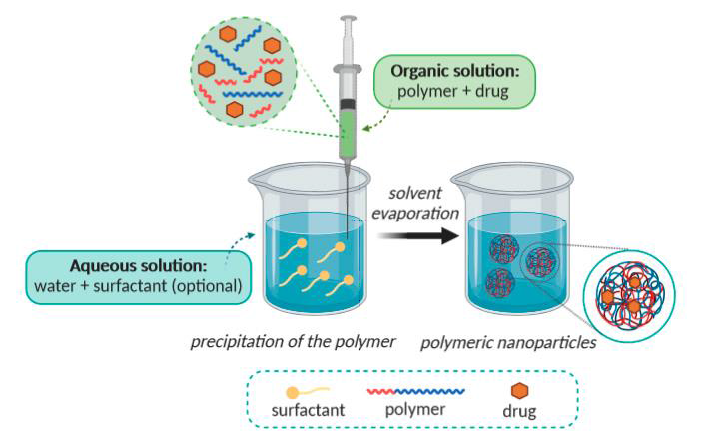

4. Nano precipitation method

This is another method which is widely used for nanoparticle preparation, which is also called solvent displacement method. This technique was first described by Fessi et al. 1989 [10, 11] Tamizhrasi at al prepared Lumivudine loaded nanoparticles. Firstly drug was dissolved in water, and then cosolvent (acetone used for make inner phase more homogeneous) was added into this solution. Then another solution of polymer (ethyl cellulose, eudragit) and propylene glycol with chloroform prepared, and this solution was dispersed to the drug solution as given in fig. 6.

Ten milliliters of a 70% aqueous ethanol solution were gradually mixed with this dispersion. The organic solvents were eliminated after five minutes of mixing by evaporating at 35° under normal pressure. The nanoparticles were then separated using a cooling centrifuge (10000 rpm for 20 min), the supernatant was drained, and the nanoparticles were cleaned with water and dried in a desiccator at room temperature [14].

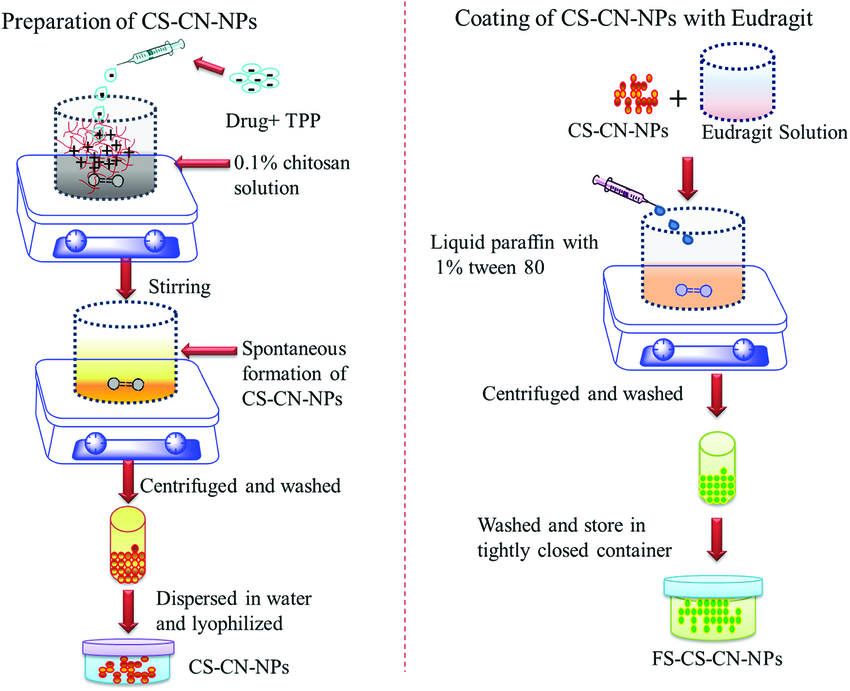

Ionic gelation method

Ionic gelation method also known as coacervation, is a technique that requires the creation of two aqueousphases: a polymer called chitosan, an adi-block co-polymer of ethylene oxide or propylene oxide (PEO-PPO), and a polyanion called sodium tripolyphosphate. These phases are mixed together, and as a result, the positively charged amino group in chitosan interacts with the negatively charged tripolyphosphate to form coacervates that are nanometer in size. Coacervates are created when two aqueous phases engage electrostatically, and the ionic gelation method is used when two molecules interact owing to ionic force and transition from the liquid phase to the gel phase at room temperature [16, 17] as given in fig. 7.

Fig. 6: The nano precipitation approach [15]

Fig. 7: Ionic gelation method [18]

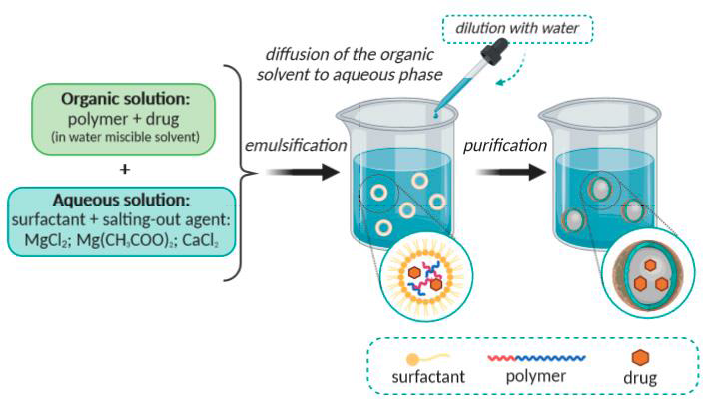

6. Salting out

It is a variation on the diffusion technique for emulsion solvents. The drug and polymer mixture in the solvent is emulsified into an aqueous gel. Salting agents include non-electrolytes (sucrose) and electrolytes (magnesium chloride, calcium chloride, and magnesium acetate). This method's ability to effectively encapsulate medications will change if salting out agents is employed. After the process is finished, the salting out agent is removed via filtration [19] as given in fig. 8.

Fig. 8: Illustration of the salting-out method [19]

Dialysis

It works in a manner akin to Nano precipitation. It is appropriate for creating narrowly dispersed, tiny nanoparticles. Here, an organic solvent-containing polymer is poured into the dialysis tube. As a result of the polymer losing its solubility, it aggregates to produce a homogenous dispersion of nanoparticles. A semi-permeable barrier reduces the amount of mixing of the polymer solution by enabling passive solvent movement [20].

SCF, or supercritical fluid technology

SCF can be used to produce nanoparticles in large quantities. This method has none of the disadvantages of previous methods. SCF is a substitute technique for creating biodegradable nanoparticles and micro particles. Eco-friendly is SCF fluid. Carbon dioxide is one of the widely used SCF due to non-toxic and non-inflammatory nature.

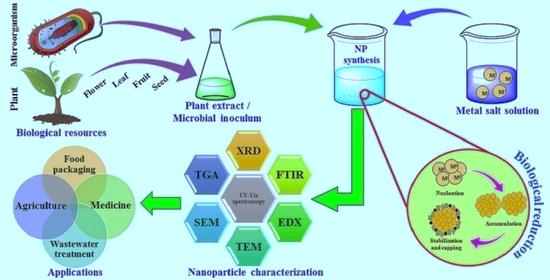

Synthesis of nanoparticles

It is possible to create nanoparticles chemically or biologically. Chemical synthesis processes have been linked to numerous negative impacts since they include harmful chemicals that are adsorbed onto their surface. Environmentally sustainable substitutes for chemical and physical processes in the manufacture of nanoparticles include biological methods that employ microbes, enzymes, fungi, plants, or plant extracts [21-26]. The creation of these environmentally acceptable techniques for nanoparticle synthesis is becoming a significant area of nanotechnology, particularly for the numerous applications of silver nanoparticles [27–29].

Biosynthesis: mechanism

Microorganisms' ability to biosynthesize nanoparticles is an environmentally benign technology. Metal oxides like titanium oxide and zinc oxide, as well as a variety of prokaryotes and eukaryotes, are employed in the synthesis of metallic nanoparticles, including silver, gold, platinum, zirconium, palladium, iron, and cadmium.

These microorganisms consist of algae, fungus, bacteria, and actinomycetes. Depending on where the nanoparticles are located, the synthesis process for them might be either extracellular or intracellular [30, 31] as given in fig. 9.

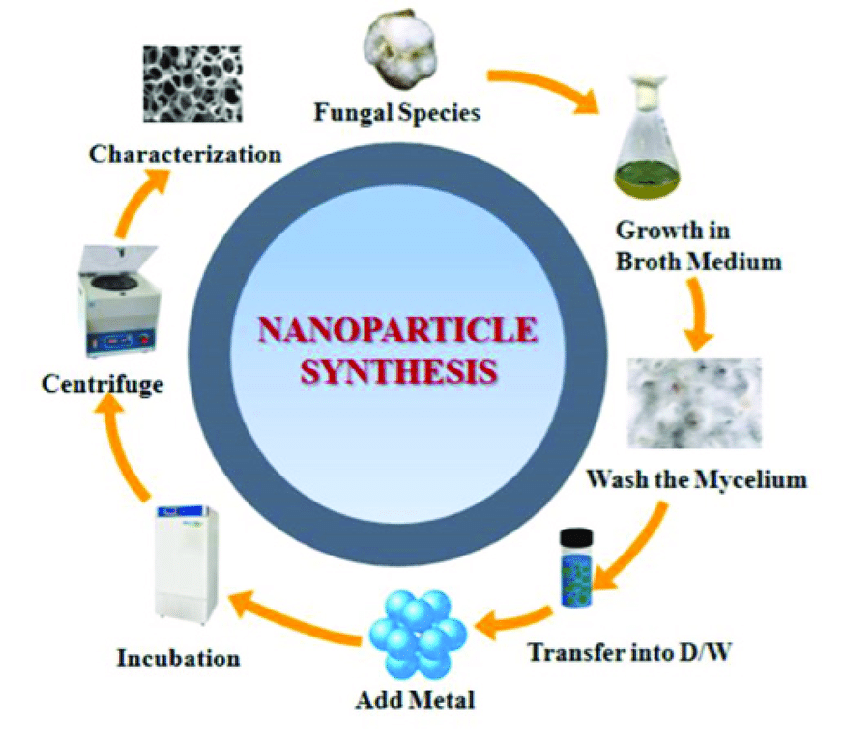

Intracellular synthesis of nanoparticles by fungi

This method involves transport of ions into microbial cells to form nanoparticles in the presence of enzymes. Inside the organism, smaller nanoparticles are generated compared to extracellularly reduced nanoparticles. The particles' ability to nucleate inside the organisms is likely connected to the size limit.

Fungal extracellular production of nanoparticles

Since extracellular synthesis does not require the presence of extraneous cellular components, it has a wider range of uses than intracellular synthesis as shown in fig. 10.

Due in large part to their massive secretory components, which are involved in the reduction and capping of nanoparticles, fungi are known to create nanoparticles extracellular [32].

Fig. 9: Biosynthesis of nanoparticles [30]

Fig. 10: Nanoparticle synthesis [32]

Microbes for the synthesis of nanoparticles

Intracellular or extracellular generation of inorganic materials occurs in both unicellular and multicellular organisms [33]. The hunt for novel materials makes use of microorganisms' capacity to regulate the creation of metallic nanoparticles, such as fungi and bacteria. In research on the biological production of metallic nanoparticles, fungi have taken center stage due to their tolerance and capacity for metal bioaccumulation [34].

The features of nanoparticles/characterization of nanoparticles

Using sophisticated microscopic methods like atomic force microscopy (AFM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), nanoparticles are typically identified by their size, shape, and surface charge. The physical stability and in vivo distribution of the nanoparticles are influenced by the average particle diameter, size distribution, and charge [35].

1) Dimensions: The most frequent method for measuring particle size and distribution is electron microscopy. Particle measurements are done using images from transmission electron microscopes (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [36].

2) Surface area: A nanoparticle's qualities are greatly influenced by its surface area to volume ratio. The most popular method for measuring surface area is BET analysis.

3) Composition: The purity and functionality of the nanoparticles are dictated by their chemical or elemental composition. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy is typically used to assess composition (XPS). Certain methods, like mass spectrometry, atomic emission spectroscopy, and ion chromatography, need the chemical digestion of the particles before wet chemical examination [37].

4) Surface morphology: The shapes and surface structures of the nanoparticles vary, which is significant for taking advantage of their capabilities.

Spherical, flat, cylindrical, tubular, conical, and irregular shapes with crystalline or amorphous surfaces with uniform or imperfections on them are a few of the shapes. The surface is generally determined by electron microscopy imaging techniques like SEM and TEM [38].

5) Surface charge: A nanoparticle's interactions with a target are dictated by its surface charge. A zeta potentiometer is used to quantify surface charges and the stability of their dispersion in a solution.

6) Crystallography: The study of atom and molecular arrangements in crystal solids is known as crystallography. To ascertain the structural arrangement, powder X-ray, electron, or neutron diffraction is used in the crystallography of nanoparticles [39].

7) Poly dispersity index: Using the Malvern Zetasizer, the produced nanoparticles' polydispersity index was determined [40].

8) Release of drugs: Drug loading is the quantity of bound drug per mass of polymer and is expressed as a percentage of the polymer. Analytical techniques are employed, including gel filtration, centrifugal ultrafiltration, UV spectroscopy, HPLC, and ultra-centrifugation [41, 42].

Applications of nanoparticles in the pharmaceutical industry

Using nanoparticles to deliver drugs for proteins and peptides. Protein delivery is a key topic of research because of the growing number of novel biotechnological molecules, including monoclonal antibodies, hormones, and vaccines, as well as their potential for therapeutic use [43]. The outcome of the balance between stabilizing and destabilizing factors is protein stability. Weak non-covalent interactions, including as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic contacts, are the foundation for the creation and stability of the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of proteins. This delicate equilibrium will be shifted and the proteins will become unstable if any of these interactions are disrupted [44, 45]. The following are new technology and delivery methods for therapeutic proteins and peptides:

Tumor-targeting drug delivery system

Based on the following features, the use of nanoparticles for tumor targeting makes sense:

1) Through active targeting by ligands on their surface or improved permeability and retention effect, nanoparticles will be able to deliver a concentrated dose of medicine in the neighborhood of the tumor targets.

2) By limiting drug distribution to the target organ, nanoparticles will lower the amount of drug exposure in healthy tissues.

Research indicates that the drug distribution pattern in vivo is significantly influenced by the polymeric composition of nanoparticles, including the type, hydrophobicity, and biodegradation profile of the polymer, as well as the associated drug's molecular weight, localization within the nanospheres, and mode of incorporation technique (adsorption or incorporation) [46, 47].

Different anticancer medications encapsulated in nanoparticles

Nanoparticles in dermatology

The new generation of carrier systems benefits from enhanced skin penetration capabilities, depot effect with continuous drug release, and surface functionalization (e. g., binding to particular ligands) enabling targeted cellular and subcellular delivery. The administration of drugs to the skin using nanoparticles and nano-carriers has the potential to transform the management of several skin conditions [48].

Dermal drug delivery

To improve the local bioavailability of API at their drug target, dermal drug administration using (lipid nanoparticle) LN is especially interesting for disorders of the HF (hair follicle). Drug targets in the HF have been discovered; for example, isotretinoin promotes apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in sebocytes [49] in the dermal papilla, monoxide promotes prostaglandin and vascular endothelial growth factor synthesis [50, 51], while cyclosporine A helps hair epithelial cells proliferate.

Cosmetics using nanoparticles

The goal of this analysis is to examine a promising field of nanoparticles that are utilized in a variety of cosmetic goods, including foundation, moisturizer, anti-wrinkle cream, soap, toothpaste, blush, eye shadow, nail polish, perfume, and after-shave lotion. In particular, NLCs have been identified as a potential next generation cosmetic delivery agent that can provide enhanced skin hydration, bioavailability, stability of the agent and controlled occlusion [52].

Gene delivery using nanoparticles

In order to trigger an immune response, polynucleotide vaccines transfer genes encoding pertinent antigens to host cells where they are produced. This results in the production of the antigenic protein in the proximity of expert antigen-presenting cells. Because intracellular protein creation stimulates both arms of the immune system more than extracellular protein deposition does, such vaccines elicit both humoral and cell-mediated protection [53, 54].

Anti-microbial techniques in the application of nanotechnology in medicine

The use of Nano crystalline silver as an antibacterial agent for wound therapy was among the first uses of Nano medicine. Staph infections can be prevented with a lotion containing nanoparticles. Nitric oxide gas, which is known to destroy germs, is present in the nanoparticles. Utilizing the nanoparticle cream to produce nitric oxide gas at the location of staph abscesses dramatically decreased the infection, according to studies conducted on mice. Burn dressing using an antibiotic-containing nanocapsule coating. The antibiotics are released from the Nano capsules when an infection begins because of the harmful bacteria in the wound [55, 56].

Application of nanotechnology in medicine: cell repair

In fact, like antibodies, certain sick cells may be engineered to be repaired by nanorobots.

See this page for details on the design study of one such cell repair nanorobot: Cromoglicates, Cell Repair Nanorobots for Chromosome Repair Therapy: The Perfect Gene Delivery Vector [57, 58].

Drug delivery into the brain using nanoparticles

The most significant obstacle impeding the development of novel medications for the central nervous system is the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The BBB is made up of largely impermeable endothelial cells that have tight connections, active efflux transport mechanisms, and enzymatic activity. It successfully stops water-soluble molecules from entering the central nervous system (CNS) and, through the action of efflux pumps or enzymes can also lower the concentration of lipid-soluble molecules in the brain. Consequently, only chemicals that are necessary for brain function can pass through the BBB selectively [59-61].

CONCLUSION

Over the past few decades, PNPs that have been functionalized as an innovative delivery system have advanced significantly. These developments include the creation of nanocarriers, ligand-based PNPs, target-specific drug release, and nano-hydrogels, which are currently receiving a lot of attention. PNPs have been compiled for drug delivery and their own benefits due to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and versatility. Drug delivery to the brain target, cancer, gene therapy, liver, diabetic wounds, Alzheimer's, respiratory, colon, and vaginal diseases are only a few of the many biological uses.

PNPs are the biomedical fields that are in constant development and the challenges that must be resolved contribute to the dynamic of this field. The future perspective of biomedical applications the ability of PNPs to change it with different targeting agents that can target the needed localized site is very effective. There is great promise for polymers as drug-delivery polymers. Modern technology is currently modifying nano carriers to do therapeutic diagnostics as well as biological imaging.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors express their gratitude to the faculty members of the Ashoka Institute of Technology and Management (Pharmacy Institute) and other supporting staff members for their invaluable contributions to the preparation of the review article.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

I was conceptualized for the design and initially wrote the paper and reviewed it. PreetKaur handled data collection and interpretation, while Brijesh Singh sir performed the quality check on the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

There is no conflict of interest among the authors of the review article.

REFERENCES

Ahmad MZ, Mohammed AA, Algahtani MS, Mishra A, Ahmad J. Nanoscale topical pharmacotherapy in the management of psoriasis: contemporary research and scope. J Funct Biomate. 2023;14(1):1-19. doi: 10.3390/jfb14010019.

Kondapuram P, Kumar SS. A review of merely polymeric nanoparticles in recent drug delivery system. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022;15(4):4-12. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2022.v15i4.43239.

Khan I, Saeed K, Khan I. Nanoparticles: properties, applications and toxicities. Arab J Chem. 2019;12(7):908-31. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.05.011.

Nalla A. Novel herbal drug delivery system an overview. WJPPS. 2017;6(8):369-95. doi: 10.20959/wjpps20178-9712.

Sandhiya V, Ubaidulla U. A review on herbal drug loaded into pharmaceutical carrier techniques and its evaluation process. Future J Pharm Sci. 2020;6(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s43094-020-00050-0.

Salavati Niasari M, Davar F, Mir N. Synthesis and characterization of metallic copper nanoparticles via thermal decomposition. Polyhedron. 2008;27(17):3514-8. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2008.08.020.

Tai CY, Tai CT, Chang MH, Liu HS. Synthesis of magnesium hydroxide and oxide nanoparticles using a spinning disk reactor. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2007;46(17):5536-41. doi: 10.1021/ie060869b.

Tiwari DK, Behari J, Sen P. Application of nanoparticles in waste water treatment. World Applied Sciences Journal. 2008;3(3):3417-33.

Ealias AM, Saravanakumar P. A review on the classification, characterisation, synthesis of nanoparticles and their application. IOP Conf S Mater Sci Eng. 2017;263(3):32019. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/263/3/032019.

Pal SL, Jana U, Manna PK, Mohanta GP, Manavalan R. Nanoparticle: an overview of preparation and characterization. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2011;1(6):228-34.

Nagavarma BV, Yadav HKS, Ayuz A, Vasudha LS, Shivakumar HG. Different techniques for preparation of polymeric nanoparticles a review. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2012;5(3):1-8.

Mullaicharam AR. Nanoparticles in drug delivery system. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis. 2011;1(2):103-21. doi: 10.4103/2231-0738.84194.

Allouche J. Synthesis of organic and bioorganic nanoparticles: an overview of the preparation methods. Springer Verlag London; 2013. p. 27-74.

Aleksandra Z, Carreiro F, Oliveira AM, Andreia N, Barbara P, Nagasamy DV. Polymeric nanoparticles: production, characterization toxicol ecotoxicol. Mol. 2020 Aug 15;25(16):3731. doi: 10.3390/molecules25163731.

Tamizhrasi S, Shukla A, Shivkumar T, Rathi V, Rathi JC. Formulation and evaluation of lamivudine-loaded polymethacrylic acid nanoparticles. Int J PharmTech Res. 2009;1(3):411-5.

Mu L, Feng SS. PLGA/TPGS nanoparticles for controlled release of paclitaxel: effects of the emulsifier and drug loading ratio. Pharm Res. 2003;20(11):1864-72. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000003387.15428.42, PMID 14661934.

Puglisi G, Fresta M, Giammona G, Ventura CA. Influence of the preparation conditions on poly(ethylcyanoacrylate) nanocapsule formation. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 1995;125(2):283-7. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(95)00142-6.

Calvo P, Remunan Lopez C, Vila Jato JL, Alonso MJ. Novel hydrophilic chitosan polyethylene oxide nanoparticles as protein carriers. J Appl Polym Sci. 1997;63(1):125-32. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19970103)63:1<125::AID-APP13>3.0.CO;2-4.

Jung J, Perrut M. Particle design using supercritical fluids: literature and patent survey. J Supercrit Fluids. 2001;20(3):179-219. doi: 10.1016/S0896-8446(01)00064-X.

Singh P, Kim YJ, Zhang D, Yang DC. Biological synthesis of nanoparticles from plants and microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 2016;34(7):588-99. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.02.006, PMID 26944794.

Klaus T, Joerger R, Olsson E, Granqvist CG. Silver-based crystalline nanoparticles microbially fabricated. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(24):13611-4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13611, PMID 10570120.

Konishi Y, Ohno K, Saitoh N, Nomura T, Nagamine S, Hishida H. Bioreductive deposition of platinum nanoparticles on the bacterium shewanella algae. J Biotechnol. 2007;128(3):648-53. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.11.014, PMID 17182148.

Willner I, Baron R, Willner B. Growing metal nanoparticles by enzymes. Advanced Materials. 2006;18(9):1109-20. doi: 10.1002/adma.200501865.

Vigneshwaran N, Ashtaputre NM, Varadarajan PV, Nachane RP, Paralikar KM, Balasubramanya RH. Biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus aspergillus flavus. Mater Lett. 2007;61(6):1413-8. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2006.07.042.

Shankar SS, Rai A, Ankamwar B, Singh A, Ahmad A, Sastry M. Biological synthesis of triangular gold nanoprisms. Nat Mater. 2004;3(7):482-8. doi: 10.1038/nmat1152, PMID 15208703.

Ahmad N, Sharma S, Singh VN, Shamsi SF, Fatma A, Mehta BR. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Desmodium triflorum: a novel approach towards weed utilization. Biotechnol Res Int. 2011;2011:1-8. doi: 10.4061/2011/454090.

Armendariz V, Gardea Torresdey JL, Jose Yacaman M, Gonzalez J, Herrera I, Parsons JG. Proceedings of the conference on application of waste remediation technologies to agricultural contamination of water resources Kansas City, MO, USA; 2002.

Kim BY, Rutka JT, Chan WC. Nanomedicine. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(25):2434-43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0912273, PMID 21158659.

Kyriacou SV, Brownlow WJ, Xu XH. Using nanoparticle optics assay for direct observation of the function of antimicrobial agents in single live bacterial cells. Biochemistry. 2004;43(1):140-7. doi: 10.1021/bi0351110, PMID 14705939.

Hulkoti NI, Taranath TC. Biosynthesis of nanoparticles using microbes a review. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2014 Sep 1;121:474-83. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.05.027.

Mann S. Biomineralization principles and concepts in bioinorganic materials chemistry. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198508823.001.0001.

Narayanan KB, Sakthivel N. Biological synthesis of metal nanoparticles by microbes. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2010;156(1-2):1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2010.02.001, PMID 20181326.

Vanlalveni C, Ralte V, Zohmingliana H, Das S, Anal JM, Lallianrawna S. A review of microbes mediated biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their enhanced antimicrobial activities. Heliyon. 2024;10(11):e32333. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32333, PMID 38947433.

Sastry M, Ahmad A, Khan I, Kumar R. Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles using fungi and actinomycete. Curr Sci. 2003;85(2):162-70.

Mcbride AA, Price DN, Lamoureux LR, Elmaoued AA, Vargas JM, Adolphi NL. Preparation and characterization of novel magnetic nano-in-microparticles for site-specific pulmonary drug delivery. Mol Pharm. 2013;10(10):3574-81. doi: 10.1021/mp3007264, PMID 23964796.

Marsalek R. Particle size and zeta potential of ZnO. APCBEE Procedia. 2014;9:13-7. doi: 10.1016/j.apcbee.2014.01.003.

Sharma V, Rao lJM. An overview on chemical composition, bioactivity and processing of leaves of cinnamomum tamala. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014:54(4)433-48. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.587615.

Hodoroaba VD, Rades S, Unger WE. Inspection of morphology and elemental imaging of single nanoparticles by high-v resolution SEM/EDX in transmission mode. Surface & Interface Analysis. 2014;46(10-11):945-8. doi: 10.1002/sia.5426.

Yano F, Hiraoka A, Itoga T, Kojima H, Kanehori K, Mitsui Y. Influence of ion-implantation on native oxidation of Si in a clean room atmosphere. Appl Surf Sci. 1996;100-101:138-42. doi: 10.1016/0169-4332(96)00274-7.

Aejaz A, Azmail K, Sanaullah S, Mohsin A. Formulation and in vitro evaluation of aceclofenac solid dispersion incorporated gels. Int J Appl Sci. 2010;2(1):7-12.

Souza SD. A review of in vitro drug release test methods for nanosized dosage forms. Adv Pharm. 2014;2:1-12. doi: 10.1155/2014/304757.

PB Abeena, R Praveen Raj, PA Daisy. A review on cyclodextrinsnanosponges. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2020;60(1):132-7.

Almeida AJ, Souto E. Solid lipid nanoparticles as a drug delivery system for peptides and proteins. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59(6):478-90. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.007, PMID 17543416.

Banga AK. Pharmaceutical application of nanoparticles in drug delivery system Drug Delivery Today. Pharm Technol. 2002;61:150-4.

Wang W. Instability stabilization and formulation of liquid protein pharmaceuticals. Int J Pharm. 1999;185(2):129-88. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00152-0, PMID 10460913.

Chandrababu D, Hiren B, Patel L. Pharmaceutical application of nanoparticles in drug delivery system. Asian J Pharm Life Sci. 2012;56:456-98.

Zhang Q, Shen Z, Nagai T. Prolonged hypoglycemic effect of insulin loaded polybutylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles after pulmonary administration to normal rats. Int J Pharm. 2001;218(1-2):75-80. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00614-7, PMID 11337151.

Papakostas D, Rancan F, Sterry W, Blume Peytavi U, Vogt A. Nanoparticles in dermatology. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303(8):533-50. doi: 10.1007/s00403-011-1163-7, PMID 21837474.

Nelson AM, Gilliland KL, Cong Z, Thiboutot DM. 13-cis retinoic acid induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human SEB-1 sebocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(10):2178-89. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700289, PMID 16575387.

Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. J Dermatol. 2004;150(2):186-94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x.

Takahashi T, Kamimura A. Cyclosporin a promotes hair epithelial cell proliferation and modulates protein kinase C expression and translocation in hair epithelial cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(3):605-11. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01452.x, PMID 11564166.

Parixit P, Rikisha B. Cytokines and signal transduction pathways mediated by anthralin in alopecia areata affected dundee experimental balding rats. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;2:40-55.

Phillipos T. Safety and risk associated with nanoparticles a review. J Miner Mater Char Eng. 2010;9(5):455-9. doi: 10.4236/jmmce.2010.95031.

Cincinnati OH. Approaches to safe nanotechnology; an information exchange. CDC; 2006.

Cho K, Wang X, Nie S, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Therapeutic nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1310-6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1441, PMID 18316549.

Kaur IP, Bhandari R, Bhandari S, Kakkar V. Potential of solid lipid nanoparticles in brain targeting. J Control Release. 2008;127(2):97-109. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.12.018, PMID 18313785.

Imam SS. Nanoparticles: the future of drug delivery. Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2023;15(6):8-15. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2023v15i6.3076.

Vijayashankar S, U Doss. Analysis of salivary components to evaluate the pathogenesis of autism in children. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2014;7(4):205-11.

Renganathan S, Fatma S, PK. Green synthesis of copper nanoparticle from Passiflora foetida leaf extract and its antibacterial activity. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(4):79-83. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i4.15744.

Yadav NK, Mazumder R, Rani A, Kumar A. Current perspectives on using nanoparticles for diabetes management. Int J App Pharm. 2024;16(5):38-45. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i5.51084.

Phalak SD, Bodke V, Yadav R, Pandav S, Ranaware M. A systematic review on nano drug delivery system: solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN). Int J Curr Pharm Sci. 2024;16(1):10-20. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2024v16i1.4020.