Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 4, 120-123Case Study

An RISING MENACE TO SOCIETY: A Case Series oN Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

SANJAYKUMAR RATHWA¹, PRATIKSHA RATHWA¹*, PRAYANS SHAH¹, VRUSHABH NIRGUDE¹

¹Department of Medicine, SBKS Medical Institute and Research Centre, Sumandeep Vidyapeeth Deemed to be University, Pipariya, Vadodara, Gujrat, India. ¹*Department of Dermatology Venereology and Leprosy, SBKS Medical Institute and Research Centre, Sumandeep Vidyapeeth Deemed to be University, Pipariya, Vadodara, Gujrat, India

*Corresponding author: Pratiksha Rathwa; *Email: rathwa.pratiksha.rpk@gmail.com

Received: 17 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 10 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a complex neurological disorder characterized by elevated intracranial pressure. This case series examines the clinical manifestations and therapeutic management of IIH. The patients presented with headache, visual disturbances, and diplopia, with the latter symptom attributed to abducens nerve palsy. Our findings highlight the importance of prompt recognition and treatment of IIH, as delayed diagnosis can lead to irreversible visual loss and other complications. This case series provides valuable insights into the presentation and management of IIH, emphasizing the need for increased awareness and vigilance among healthcare providers.

Keywords: Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension, Papilledema, High intracranial pressure, Acetazolamide, Headache, Pseudotumour Cerebri

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i4.7009 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), formerly known as pseudo tumor cerebri. IIH is a complex neurological disorder characterized by elevated intracranial pressure, often manifesting with debilitating headaches and other symptoms that significantly impact quality of life [1]. Despite advances in neuroimaging and diagnostic techniques, the pathophysiology of IIH remains poorly understood, and its diagnosis can be challenging due to the lack of a clear etiology and the presence of nonspecific symptoms [2].

The clinical presentation of IIH is highly variable, and patients often experience a range of symptoms beyond headache, including visual disturbances, diplopia, and cognitive impairment [3]. Visual symptoms, in particular, are a common feature of IIH, with patients often reporting transient visual obscurations, double vision, and blurred vision [4]. These symptoms can have a profound impact on daily life, leading to significant disability and decreased quality of life. Furthermore, studies have shown that IIH can have a significant impact on mental health, with patients experiencing anxiety, depression, and other psychological symptoms [5]. The diagnosis of IIH is made by the modified Dandy criteria consisting of [1]:

Signs and symptoms of increased intracranial hypertension.

Normal neurological exam (except 6th nerve palsy and papilledema) including mental status examination.

No evidence of hydrocephalus, mass, structural, or vascular lesion on neuroimaging.

Increased lumbar puncture opening pressure (>25 cmH2O)

Normal cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) contents

No other cause of increased ICP identified

This case series aims to contribute to the growing body of literature on IIH by presenting a detailed examination of the clinical manifestations, diagnostic challenges, and therapeutic outcomes of this condition. By exploring the complexities of IIH, we hope to provide valuable insights into the diagnosis and management of this condition and inform best practices for the care of patients with IIH.

CASE 1

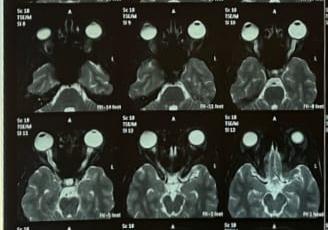

A 27 y old female appeared with a month's worth of headaches and hazy eyesight. Severe Headache was evident on both sides of the occipital region, along with nausea. For one month, the patient had blurred vision that lasted only a few seconds and resolved spontaneously. Her BMI was normal when she was examined. There was no major personal or family history. The intraocular pressure in both eyes was 17 mmHg, according to aplan tonometry. Light perception and projection were present in both eyes. Both eyes showed a papillary light reflex. Ophalmoscopy of both eyes revealed papilledema, no boundaries on the optic nerve head, dilated retinal veins, and a chrysanthemum flower in the right eye. Visual field tests found an increasing blind spot in both eyes, as well as some paracentral scotoma. The lumbar puncture was conducted with a high opening pressure of 250 mmH2O. The CSF test revealed no abnormalities. All required blood tests were performed, which turned out to be normal. The MRI brain with orbit revealed flattening of the posterior sclera, protrusion of the optic nerve heads, and vertical tortuosity of the optic nerve sheath, which suggested the likelihood of pseudotumour cerebri fig. 1. Because of the minor visual field loss, treatment began while in the hospital with mannitol (20%) TID and acetazolamide 500 mg BD. Methylprednisolone injections (1g/d) were given for 5 d. Before being discharged from the hospital, it was recommended to limit physical activity and treat with acetazolamide 250 mg BD and oral prednisolone in decreasing doses. After a month, the follow-up assessment indicated maximal visual acuity in both eyes without correction. An opthalmoscopy examination indicated bilateral mild papilloedema. The study of the visual field indicated very minimal modifications. After a two-month follow-up, there was no Papilloedema and no headaches or blurred vision.

CASE 2

A 30 y old female presented with a complaint of severe throbbing headaches in both temporal regions for two months. The headache had been exacerbated for one month and was accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and retroorbital pain. The patient's headache is bad enough to wake her up from sleep. Complaint of blurred eyesight for one month, which was temporary. The patient also has a complaint of diplopia. Upon testing, she was discovered to be overweight, having a BMI of 24.5. An eye examination revealed abducens nerve palsy. During an opthalmoscopic examination, the right eye showed slight blurring of the disc edge as well as mild venous tortuosity. In the left eye, there is 360 °C blurring of the disc edge. There was more papilloedema in the left eye than in the right. The lumbar puncture was performed under high opening pressure of 230 mmH2O. The CSF count, sugar, and protein levels were all within normal limits. A blood test revealed dyslipidemia, which is defined by elevated cholesterol and triglycerides. An MRI brain with orbit was performed, which revealed that the orbital section of the optic nerve is tortuous and kinked bilaterally. Flattening of the posterior sclera and protrusion of the optic nerve head on both sides, as well as large CSF sleeves around the optic nerve, suggest pseudotumour cerebri fig. 2. The patient was originally treated with acetazolamide 500 mg BD and mannitol (20%) TID. We also administered dexona 8 mg TID injections for three days, followed by oral steroids in tapering doses. The patient was encouraged to lose weight and change her lifestyle. After discharge, oral acetazolamide was continued. After 15 d, a follow-up revealed minimal papilloedema with significant reduction in symptoms. patient came for second follow up after 3 mo with no symptoms and examination revealed no Papilloedema.

Fig. 1: MRI brain with flattening of posterior sclera and protrusion of optic nerve head

Fig. 2: MRI brain with changes of IIH

CASE 3

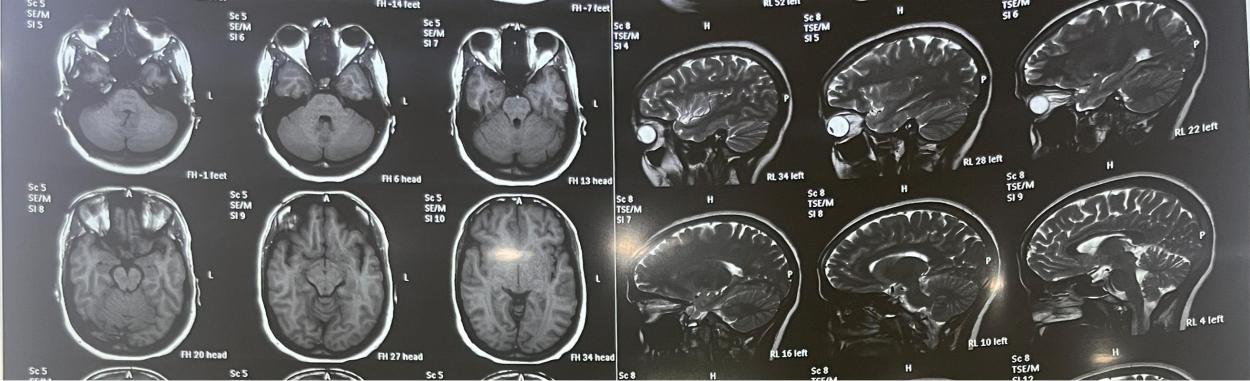

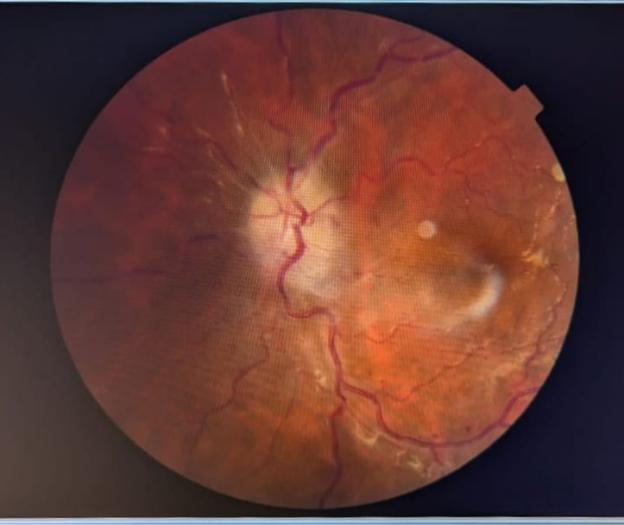

A 42 y old female reported with a widespread throbbing headache coupled with nausea for several months. She has also been complaining about visual problems in the form of blurred vision for the past month. This lasted a few minutes and resolved spontaneously. She also complained of double vision. There was no accompanying vomiting. She was hypertensive and on regular medications for the same. Upon assessment, she was shown to be obese with a BMI of 31. Her blood was tested, and the results were normal. Opthalmologic evaluation reveals a peripheral visual field deficit but no significant reduction in visual acuity. The abducens nerve palsy is present. Fundoscopic examination revealed hypertensive retinopathy with papilloedema changes. Specific findings included arteriolar attenuation, venous tortuosity, dot blot hemorrhages, and hard exudates, all of which are characteristic of advanced hypertensive retinopathy fig. 3. The presence of papilloedema suggests increased intracranial pressure. For additional study, an MRI BRAIN with orbit was performed, which revealed an empty sella turcica, flatness of the posterior sclera, and protrusion of the optic nerve head fig. 4. Lumbar puncture is unique for its high opening pressure of 240 mmH2O. CSF investigation for count, protein, and sugar yields normal results. She was started on oral acetazolamide 500 mg BD and Mannitol (20%) TID dosages. Furosemide 20 mg BD tablets are administered, which also aid to reduce her blood pressure. She was recommended to follow a low-sodium diet and was assigned to a dietitian for weight loss. There were no symptoms or papilloedema during the one-month follow-up visit. On further follow up after 1 mo she was fully symptom free and had lost around 4 kg.

Fig. 3: Fundoscopic changes of hypertensive retinopathy and papilloedema

Fig. 4: MRI brain with empty sella turcica and protrusion of optic nerve head

CASE 4

A 37 y old female arrived with occasional impaired vision for two months, which resolved spontaneously. She had a pulsatile headache for two months. Symptoms were more noticeable in the morning. The headache was relieved after taking NSAIDS. Over the course of a month, the symptoms became more severe. The patient experienced an intermittent but intense headache that woke her up from sleep. She describes it as the worst headache she's ever had. Upon assessment, she was discovered to be obese with a BMI of 32. All blood tests were completed, and the results were within normal limits. Upon examination, the ocular fundus revealed bilateral optic disc edema with a blurring boundary that was more prominent in the right eye than the left. Retinal veins are tortuously dilated. There was presence of dot blot hemorrhages and macular edema. Papillary edema present in both eyes fig. 5. The visual fields of both eyes indicate enlargement of the blind spots. Lumbar puncture was performed with a high opening pressure of 260 mmH2O. The biochemical examination of CSF was normal. An MRI brain scan was performed, which was normal. The patient was started on acetazolamide 250 mg tablet four times a day. The patient was urged to lose weight and follow a salt-restricted diet. After two weeks of follow-up, the impaired vision had improved along with minor papilledema. After 8 w, the patient was asymptomatic and had no papilloedema.

Fig. 5: Fundoscopic changes of papilloedema, dot blot hemorrhages and macular edema

CASE 5

A 35 y old female complained of a chronic headache for three months. The headache was generalised, throbbing, and not accompanied by nausea or vomiting. There were no accompanying visual problems, convulsions, or fever. On inspection, she was discovered to be obese. Her neurological evaluation revealed no specific neurological deficits. Her blood pressure was normal. Her blood was tested, and it was normal. MRI BRAIN with orbit was performed, which was completely normal. On an opthalmological assessment, both eyes' visual acuity was normal. bilateral enlarged optic disc in the posterior portion, suggestice of developed papilloedema. The other examinations were normal. The lumbar puncture revealed a high opening pressure of 260 mmH2O. The biochemical analysis of CSF was normal. The patient was given acetazolamide 500 mg four times a day. Mannitol (20%) injection was administered thrice a day for three days. She was encouraged to lose weight and counselled by a dietitian. Her symptoms improved after three weeks, although she still had papilledema. After 8 w, she was completely asymptomatic, and the papilloedema had been resolved.

DISCUSSION

Idiopathic intracranial Hypertension (IIH), also known as benign intracranial hypertension is a disorder of elevated cerebrospinal fluid pressure of unknown cause. As it also associated with high incidence of vision loss the term benign was no longer used. Changes in blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain tissue volume can affect intracranial pressure. IIH is likely caused by a problem in CSF control, such as excessive secretion or inadequate drainage. IIH Commonly occurs in obese women in the childbearing age [6]. Here we found that all the five patients in our case series were females with age varies from 27 to 42 y. it can occur in children,adults and nonobese person of either sex. Out of five patients 3 were obese, 1 was overweight and 1 was with normal BMI. Studies found that higher body mass index is associated with greater risk of IIH [7] so in recent world rising rates of obesity may leads to increase prevalence of IIH.

The most common symptom at presentation is headache, and which was present in all five patients. Lowering ICP can reduce headache symptoms. Patients with concurrent headache disorders may not respond well to ICP-lowering treatments, necessitating the use of traditional pain medications. IIH headaches are often pulsatile, global, worse after awakening, and exacerbated by ICP-raising activities. IIH often causes visual problems, including vision loss. Transient vision loss is found in 4 out of 5 patients. The common signpapilledema, which can be symmetric or asymmetric. IIH is characterized by papilledema, which occurs in 97% of patients. Two patients were reported diplopia it was due to consequences of abducens nerve palsy and resolve with normalisation of intracranial pressure [8] if Papilloedema left untreated it may progress to permanent vision loss and optic atrophy this is the only serious complication of IIH which leads to significant morbidity.

To rule out malignant hypertension, the patient's blood pressure should be measured at the time of presentation out of five one patient was hypertensive and one patient having Dyslipidemia. Arterial hypertension has been associated with IIH [9]. The original weight should also be confirmed and documented. Visual acuity, pupillary reflexes, and color vision must all be tested to measure optic nerve function. To examine the optic nerve head and macula, the pupils should be dilated. The degree of papilloedema should be documented as this aids in follow-up. This has been made easier by the use of Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), which correctly measures the degree of edema in the optic disc. Brain imaging helps rule out space-occupying lesions and other causes of elevated ICP, such as hydrocephalus and cerebral venous thrombosis, when diagnosing IIH [10]. Imaging abnormalities associated with raised ICP include an empty sella or flattening of the pituitary gland, tight subarachnoid spaces, flattening of the posterior globe, protrusion of the optic nerve head, enhancement of the prelaminar portion of the optic nerve head, distension of the optic nerve sheath, and vertical tortuosity of the optic nerve [11]. All of our patients underwent an MRI scan, and three of them showed IIH alterations.

Treatment for IIH focuses on relieving symptoms like headaches and protecting vision. Patients with excess weight are advised to adopt a weight-loss plan aiming for 5-10% weight reduction, combined with a low-sodium diet. For mild cases with vision impairment, various medical and surgical options are considered. Acetazolamide is recommended for patients with moderate visual field loss, as it decreases cerebrospinal fluid production and intracranial pressure [12]. Typically, a lumbar puncture provides temporary relief from IIH symptoms. Patients who have a fulminant start of disease or whose increasing visual loss which not been stopped by conventional treatments typically need surgery. Options include CSF diversion techniques such ventriculo/lumbo-peritoneal shunting or optic nerve sheath fenestration. Rapid ICP decrease with ventriculo/lumbo-peritoneal shunting frequently results in improved symptoms especially headaches [13, 14]. Additionally, none of our patients needed surgery. The choice of treatment depends on the severity of symptoms and the extent of vision loss.

CONCLUSION

IIH can no longer be considered a rare disease. As the prevalence of obesity rises, doctors must expect to see more cases of IIH. It is critical to have a high index of suspicion, and primary health care providers must be able to suspect the diagnosis and refer patients for treatment as soon as possible due to the risk of permanent vision loss.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Nil

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors have contributed equally in conception, drafting and review of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2002;59(10):1492-5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000029570.69134.1b, PMID 12455560.

Wall M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurol Clin. 2010;28(3):593-617. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2010.03.003, PMID 20637991.

Skau M, Brennum J, Gjerris F, Jensen R. What is new about idiopathic intracranial hypertension? An updated review of mechanism and treatment. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(4):384-99. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01055.x, PMID 16556239.

Digre KB, Corbett JJ. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): a reappraisal. Neurologist. 2001;7(1):2-68. doi: 10.1097/00127893-200107010-00002.

Radhakrishnan K, Ahlskog JE, Cross SA, Kurland LT, O Fallon WM. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): descriptive epidemiology and case control study. Neurology. 1993;43(4):868-74.

Radhakrishnan K, Ahlskog JE, Cross SA, Kurland LT, O Fallon WM. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri) descriptive epidemiology in rochester minn 1976 to 1990. Arch Neurol. 1993;50(1):78-80. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540010072020, PMID 8418804.

Daniels AB, Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL, Moster ML, Newman NJ. Profiles of obesity weight gain and quality of life in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(4):635-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.12.040, PMID 17386271.

Corbett JJ, Savino PJ, Thompson HS, Kansu T, Schatz NJ, Orr LS. Visual loss in pseudotumor cerebri follow up of 57 patients from five to 41 Y and a profile of 14 patients with permanent severe visual loss. Arch Neurol. 1982;39(8):461-74. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1982.00510200003001, PMID 7103794.

Corbett JJ. The 1982 silversides lecture. Problems in the diagnosis and treatment of pseudotumor cerebri. Can J Neurol Sci. 1983;10(4):221-9. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100045042, PMID 6652584.

Friedman DI, Liu GT, Digre KB. Revised diagnostic criteria for the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome in adults and children. Neurology. 2013;81(13):1159-65. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55f17, PMID 23966248.

Brodsky MC, Vaphiades M. Magnetic resonance imaging in pseudotumor cerebri. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(9):1686-93. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99039-X, PMID 9754178.

Piper RJ, Kalyvas AV, Young AM, Hughes MA, Jamjoom AA, Fouyas IP. Interventions for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(8):CD003434. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003434.pub3, PMID 26250102.

Rosenberg ML, Corbett JJ, Smith C, Goodwin J, Sergott R, Savino P. Cerebrospinal fluid diversion procedures in pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1993;43(6):1071-2. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.6.1071, PMID 8170543.

Eggenberger ER, Miller NR, Vitale S. Lumboperitoneal shunt for the treatment of pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1996;46(6):1524-30. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1524, PMID 8649541.