Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 4, 21-25Review Article

CARDIOPROTECTIVE HERBS: AN UPDATED REVIEW

RAHUL*, AJEET PAL SINGH, AMAR PAL SINGH

Department of Pharmacology, St. Soldier Institute of Pharmacy, Lidhran Campus, Behind NIT (R. E. C.), Jalandhar –Amritsar by pass, NH-1, Jalandhar-144011, Punjab, India

*Corresponding author: Rahul; *Email: rahul18933@gmail.com

Received: 12 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 05 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

"All mechanisms and ways that maintain the heart by reducing" comprise cardioprotective measures. Phytochemicals are natural bioactive molecules distinguished from other biochemicals because they exist naturally in fruits, vegetables, and medicinal plants and have an impact on the treatment of numerous diseases. It is imperative to explore the pharmacological and therapeutic potential of biodiversity of plants. Diosgenin, isoflavones, sulforaphane, carotinized, catechin, and quercetin are examples of bioactive molecules that can increase the cardioprotective influences of certain cardioprotective plants and decrease the prevalence of cardiac abnormalities.

Keywords: Cardioprotective, Medicinal plants, Phytoconstituents, Cardiovascular disease

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i4.7013 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Medicinal plants have the potential to be used as sources of medicine due to their secondary metabolites and therapeutic essential oils. Medicinal plants are used to treat a variety of ailments because they are cheaper, safer, effective, readily available, and accessible. The virtues mentioned have impacted the usage of medicinal plants among various traditional medicine practitioners to the point where herbal usage becomes a daily practice [1-3]. Many people all over the world utilize herbal medicines for their health, and many tribes have incorporated them into their cultural heritage. Polyphenols produce cardio-protective effects primarily by preventing oxidation of low-density lipoprotein. The majority of important pharmacological drugs are derived from plants. Plant-derived drugs are significant within human and animal health care systems around the globe, and are utilized to prevent health issues as well as treat pathology. Medicinal herb treatments for ischemic heart disease-related circumstances have been an established practice for many years. The last decade of the twentieth century has produced an extensive body of phytochemical, biological, and clinical evidence to suggest that plant-based herbal therapies are gaining acceptance for the treatment of numerous diseases [4, 5]. Cardiovascular disease has a significant and growing worldwide burden. In 1990, over 14 million people died from cardiovascular disease; by 2020, that number is expected to increase to about 25 million [6]. Cardiovascular disease is a substantial and growing worldwide burden. In 1990, more than 14 million people died from cardiovascular disease; by 2020, it is expected that that number will increase to nearly 25 million. The occurrences of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are increasing around the world, particularly in developing nations that are going through a rapid health transition. Poor dietary and lifestyle behaviors that contribute to diabetes and obesity are amongst the chronic opportunities for increasing CVD occurrences [7, 8].

Medicinal plants with cardioprotective potential

Emblica officinalis (E. officinalis) or Phyllanthus emblica (P. emblica) are small to medium-sized deciduous trees in the family Euphorbiaceae. Emblica officinalis (E. officinalis) or Phyllanthus emblica (P. emblica) are small to medium-sized deciduous trees in the family Euphorbiaceae [9].

Tinospora cordifolia (T. cordifolia) is a deciduous climbing shrub belonging to the Menispermaceae family; and has been shown in research in Wistar rats to effectively prevent cadmium (Cd) poisoning from altering the changes in antioxidants, glycoproteins, and serum marker enzymes (lactate dehydrogenase and creatine kinase) levels. T. cordifolia was indicated to serve as a potent cardioprotective modality for Cd intoxication, toxicity monitoring changes in the enzyme levels. The cardioprotective effects of T. cordifolia have also been characterized in rats with myocardial infarction from ischemia-reperfusion [10].

Glycerrhiza glabra

The herbaceous perennial Glycerrhiza glabra (G. glabra) is a member of the Fabaceae family. Root is crucial in terms of its therapeutic significance. The primary components are flavonoids such as isoliquiritigenin and liquiritigenin (4′,7‐ dihydroxyflavanone) and saponins such glycyrrhizin. According to a study done on rats, G. glabra exhibits cardioprotective effects that are followed by ischemia-reperfusion injury. It may also have the ability to prevent myocardial infarction by influencing heart function and having antioxidant benefits. According to a preclinical investigation, therapeutic dosages of G. glabra should not damage the heart because of the normal histoarchitecture of the myocardium [11, 12].

Terminalia arjuna (T. arjuna)

The large deciduous tree Terminalia arjuna (T. arjuna) is part of the Combretaceae family of flowering plants. In the Indian subcontinent, the bark extract is used to treat dyslipidemia, hypertension, congestive heart failure, and anginal pain. The authors Dwivedi et al. [20] explain that T. arjuna bark extract had cardioprotective activity to significantly inhibit the rise in oxidative stress due to isoprenaline, and an increase in endogenous antioxidant, as well as coronary vasodilatation [13].

Withania somnifera (W. somnifera)

The woody shrub Withania somnifera (W. somnifera) is a member of the Zygophyllaceae family. The root is the medicinally helpful part. Pretreatment with W. somnifera extract significantly alleviated the biochemical and histological changes from doxorubicin in Wistar rats. This suggests a possible role for W. somnifera in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity prevention. When given orally to hypercholesteremic rats, the root powder of the plant significantly lowered their triglyceride and total lipid cholesterol levels. A significant increase in liver bile and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutyral coenzyme levels as well as high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, were also observed. Activity of reductase was also noted [14].

Terminalia chebula (T. chebula) is an evergreen flowering tree in the family Combretaceae. Its fruit is a mild laxative, stomachic, tonic. T. chebula extract reduced rise in lactate; decrease in enzyme activities of Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) cycle, mitochondrial respiration, levels of Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. The results document anti-ischemic property of T. chebula [15].

Sida cordifolia (S. cordifolia) is an upright member of the Malvaceae family. The roots and leaves are the most medicinally important sources. S. cordifolia extract pre-treatment showed significant increased levels of catalase activity and Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) as compared to control on the isoproterenol-induced ischaemia study. This activity confirmed its ability to produce cardioprotection [16].

Tribulus terrestris (T. terrestris) is a small shrub of the Zygophyllaceae family that has hairy or silky hairy properties. ECG and various cardiac biomarkers study showed that T. terrestris had protective activity against myocardial ischemia in rats. The anti-ischemic cardioprotective properties of T. terrestris can be attributed, at least in part, to its antioxidant, antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory activities [17].

Trapa Bispinosa (T. Bispinosa)

The aquatic vegetation Trapa Bispinosa (T. Bispinosa) is part of the family Trapaceae. The fruit is well-known for its medicinal properties. Trapa bispinosa demonstrates anti-inflammatory benefits due to its high nutritional (mineral and vitamin) contents. Based on its ability to demonstrate anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, it is possible this fruit may also be contributory to the treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVDs). Unfortunately, the potassium content in this fruit has not been published. However, the intake of potassium is suggested to remarkably reduce the risk of high blood pressure and stroke in previous studies. To date, single-dose toxicity studies recommend a 3 g/kg body weight for doses [18].

Serpentina

Historically, reserpine is an alkaloid derived from the dried root of the plant R. serpentina, known as 'snake root' in Hindu medicine using Ayurvedic practices, has been utilized for centuries as an Ayurvedic treatment. The R. serpentina root for the treatment of psychoses and high blood pressure was first documented in Indian literature in 1931. However, utilization of Rauwolfia alkaloids in Western medicine began in the mid-1940s following the Second World War. Today, R. serpentina in standardized whole root preparations in the United States Pharmacopoeia is monographed, having reserpine alkaloid also monographed. 200-300 mg of powdered whole root, administered orally, is equivalent to 0.5 mg of reserpine [19].

Stephania tetrandra

The herb Stephania tetrandra has been used in Traditional Chinese medicine to treat hypertension. Tetrandrine, an alkaloidal extract from S. tetrandra, has been shown to be a calcium ion channel blocker, just like verapamil. Tetrandrine inhibits aldosterone production, blocks T and l calcium channels, and prevents diltiazem and methoxyverapamil from binding to cal-cium-channel binding sites. In conscious rats, a dose of tetrandrine (15 mg/kg, parenteral) lowered mean, systolic and diastolic blood pressure for approximate-ly 30 min; however, an intravenous dose of tetrandrine (40 mg/kg) resulted in cardiac depression, which resulted in death. An oral dose of tetrandrine (25 and 50 mg/kg) in stroke-prone hypertensive rats resulted in a progressive, long-lasting hypotensive effect after 48 h, without an alteration in plasma renin activity [20, 21].

U rhynchophylla extract relaxes norepinephrine precontracted rat aorta via both endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent mechanisms. U rhynchophylla extract likely releases nitric oxide and/or an endothelium-derived relaxing factor for the endothelium-dependent mechanism but does not bind to muscle receptors. Furthermore, research has shown both in vitro and in vivo that rhynchophylline reduces collagen or adenosine diphosphate plus epinephrine-mediated platelet thromboses and prevents platelet accumulation [22].

Veratrum viride

The perennial herb veratrum, also sometimes called hellebore, is cultivated around the globe. The several varieties include Veratrum viride, native to Canada and the eastern United States, Veratrum californicum, endemic to the western United States, Veratrum album, described from Alaska and Europe, and Veratrum japonicum, in Asia. All Veratrum plants can produce poisonous alkaloids, causing bradycardia, hypotension, and vomiting. The majority of veratrum poisonings are because of botanical misidentification with other plants. Although veratrum alkaloids were once used to treat hypertension, their usage declined due to their low therapeutic index, unacceptable toxicity, and the replacement of veratrum with safer alternatives for antihypertensive medications [23].

Panax ginseng (Asian ginseng)

Panax notoginseng is commonly called pseudoginseng because it is often an adulterant in P ginseng preparations. The root of P notoginseng is traditionally used for hemostasis and analgesia in traditional Chinese medicine, and it is also widely used to treat patients with coronary artery disease and angina [24].

Salvia miltiorrhiza (dan-shen), native to China, is related to the Western sage Salvia officinalis. The root of S. miltiorrhiza is traditionally used in Chinese medicine for its cooling, sedative, and circulatory stimulating properties. Like P notoginseng, it has exhibited the ability to dilate coronary arteries at all concentrations, suggesting that it has the potential to be an effective antianginal agent. Furthermore, salvia miltiorrhiza may not produce the effects to treat hypertension because its effects on other arteries differ dependent on concentration [25].

Garlic (Allium sativum) has been used and appreciated by people for the past thousands of years due to its medicinal properties. Garlic is one of the herbal medicines that the scientific community has studied closely. When large amounts of fresh garlic (0.25 to 1.0 g/kg, equivalent to approximately 5-20 average-sized 4-g cloves for a person weighing 78.7 kg) are ingested, the positive benefits mentioned above have been reported. This is further supported by a recent double-blind crossover trial that evaluated the effect of a placebo and 7.2 g of aged garlic extract on blood lipid levels in men with moderate hypercholesterolemia. When compared to placebo, the aged garlic extract produced a reduction in total serum cholesterol by 6.1%, and a reduction in LDL cholesterol by 4.6% [26].

Commiphora mukul (gugulipid)

Ayurveda has long used Commiphora mukul (gugulipid), a small, thorny tree found in India, to treat lipid disorders. The primary mechanism of action for gugulipid is to enhance the liver's uptake and metabolism of LDL cholesterol. 81 In a double-blind, crossover study with 125 patients on gugulipid and 108 on clofibrate, median reductions in serum cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were 11% and 16.8% with gugulipid and 10% and 21.6% with clofibrate, respectively. As a rule, patients with high cholesterol did better on gugulipid therapy than those with high triglycerides [27, 28].

Maharishi Amrit Kalash-4 and Maharishi Amrit Kalash-5 are two complex herbal formulations with significant antioxidant properties shown to inhibit LDL oxidation in hyperlipidemic subjects. They were shown in studies to inhibit platelet aggregation and microsomal lipid peroxidation induced by enzymes and non-enzymatic agents [29].

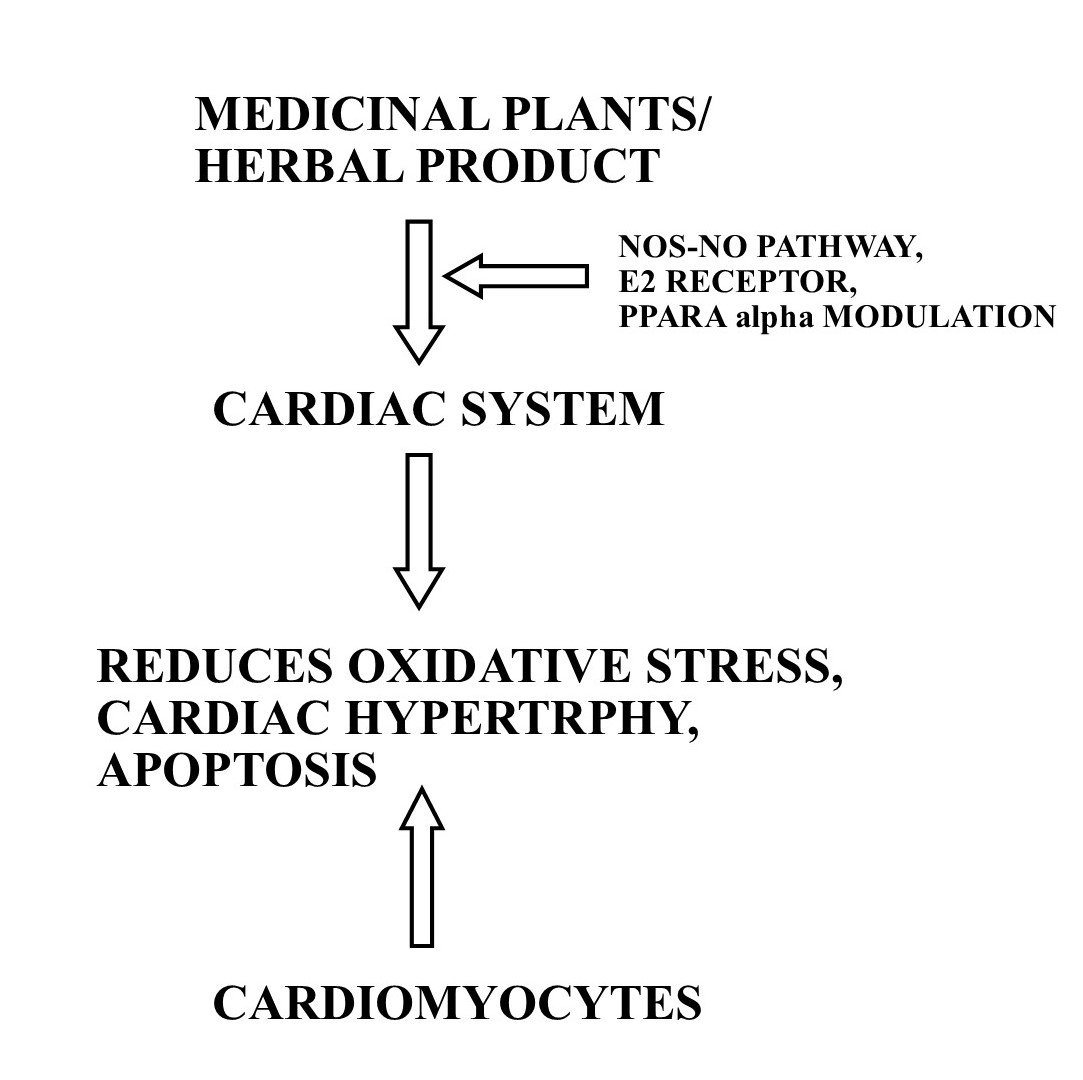

Fig. 1: Cardio protective mechanism of medicinal plants/herbal products

Table 1: Below is a list of various cardioprotective plants' pharmacological status

| Plants name | Family | Chemical constituents | Medicinal use | Dosage form |

Allium sativum (Bulb) [30] |

Liliaceae | Lavonoids, tannins, saponins, and cardiac glycosides | Antihyperlipidemic, and cardioprotective | Garlic oil |

| Ficus hispida (Leaves) [31] | Moraceae | Mucilage, gums, flavonoids, phenols, sterols, amino acids, β-amyrine acetate, protein, carbohydrates, n-triacontanol, lupeol acetate, β-sitosterol, | Cardioprotective, antipyretic, hepatoprotective | Methanol |

| Trichopus zeylanicus (leaves) [32] | Trichopus zeylanicus | Glycosides, flavonoids, steroids, tannins, | Cardioprotective, adoptogenic | Ethanol |

| Tribulus terrestris (fruit) [33] | Zygophyllaceae | Alkaloids, glycosides, and steroidal saponins | Cardioprotective, antilithiatic, | Aqueous |

| Semecarpus anacardium (dried nuts) [34] | Anacardiaceae | Phenolic compounds, biflavonoids, sterols, glycosides, ursuhenol, | Cardioprotective, antioxidant | Ethanol |

| Crocus sativus(flowers) [35] | Iridaceae | Carotenoid compounds, crocetin, crocin, safranal | Cardioprotective, hypnotic, | Aqueous |

| Ocimum sanctum (leaves) [36] | Lamiaceae | Saponins, tannin, steroid, flavonoids | Cardioprotective, antioxidant | Hydroalcohol |

| Moringa oleifera (leaves) [37] | Moringaceae | Tannins, saponins, alkaloids, terpenes | Antipyretic, and cardioprotective | Hydroalcohol |

| Lagenaria siceraria [38] | Cucurbitaceae | Flavonoids, terpenoids | Antihyperlipidemic, and cardioprotective | Juice |

| Picrorhiza kurroa (Rhizome) [39] | Scrofulariaceae | Glycosides, phenolic compounds | Anti-inflammatory, and cardioprotective | Ethanol |

| Croton sparsiflorus (leaves) [40] | Euphorbiaceae | Saponins, tannins, phenols, flavonoids, | Anti-inflammatory, and cardioprotective | Methanol |

| Azadirachta indica (leaves) [41] | Meliaceae | Tannins, flavonoids, steroids, | Cardioprotective, chemopreventive, | Aqueous |

| Coleus forskohlii (Roots) [42] | Lamiaceae | Forskolin hydrochloride, demethylcryptojaponol, | Antiobesity, and cardioprotective | Ethanol |

| Psidium guajava (leaves) [43] | Myrtaceae | Carotenoid, flavonoid, | Cardioprotective, | Aqueous |

| Hydrocotyle asiatica (whole plant) [44] | Umbelliferae | Flavonoids, and glycosides | Cardioprotective, antipsoriatic, | Alcohol |

| Terminalia arjuna (Bark) [45] | Combretaceae | Lactones, phytosterol, flavonoids, | Antihyperlipidemic, and cardioprotective | Alcohol |

Callistemon lanceolatus (leaves) [46] |

Myrtaceae | Phenolic compounds, carbohydrates, | Antioxidant, and cardioprotective | Ethanol |

| Phyllanthus niruri (whole plant) [47] | Phyllanthaceae | Flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, | Cardioprotective, anticancer, | Aqueous |

| Curcuma longa (Rhizome) [48] | Zingiberaceae | Curcumin, ar-turmerone, β-sesquiphellandrene, | Cardioprotective, anti-inflammatory | Ethanol |

| Tribulus macropterus (Aerial parts) [49] | Zygophyllaceae | Flavonoids, saponins, alkaloids | Cardioprotective | Methanol |

| Cordia myxa (fruit) [49] | Boraginaceae | Saponins, and tannin | Cardioprotective | Methanol |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa (petals) [50] | Malvaceae | Tannins, saponnins, phenols, glycosides | Antioxidant, and cardioprotective | Aqueous |

| Camellia sinensis (leaves) [51] | Theaceae | Tannins, flavonoids, steroids | Cardioprotective | Aqueous |

Mechanism of medicinal plants/herbal products

Medicinal/herbal plants have demonstrated anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, and anti-apoptotic effect, activation of the signaling pathway of endothelial nitric oxide synthase-nitric oxide (NOS-NO) and stimulation of angiogenesis, decreased endothelial permeability, regulation of the K-ATP channel to prevent free radical-mediated oxidative actions, and anti-apoptotic effects, improved mitochondrial functioning, as well as inhibition of various protein expressions (contractile) and control of calcium levels [52].

CONCLUSION

Herbal medications are widely prevalent in the world so medical providers should remember to inquire about these health behaviors while performing clinical histories, and stay informed on the potential benefits or harm of these treatments. Although the specific molecular mechanisms are still not resolved, many researchers have looked at the therapeutic and preventive benefits of plant phytoconstituents for the treatment of cardiac disorders using chemoprevention. Phytoconstituents may offer cardioprotective benefits by scavenging oxygen free radicals, inhibiting important enzymes, and modulating certain factors. In addition to allopathic treatment regimens, screening of the native medicinal plants of the surrounding landscape, in order to identify specific plant phytoconstituents with therapeutic action against cardiovascular disease, is justified.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

It’s our privilege to express the profound sense of gratitude and cordial thanks to our respected chairman Mr. Anil Chopra and Vice Chairperson Ms. Sangeeta Chopra, St. Soldier Educational Society, Jalandhar for providing the necessary facilities to complete this review work.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed equally

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Jay R, Umang H, Divyash K, Ankur K. Cardioprotective effect of methanolic extract of syzygium aromaticum on isoproterenol induced myocardial infarction in rat. Asian J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;2(4):1-6.

Arya V, Gupta VK. Chemistry and pharmacology of plant cardioprotectives: a review. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2011 May 1;2(5):1156.

Parasuraman S, Thing GS, Dhanaraj SA. Polyherbal formulation: concept of ayurveda. Pharmacogn Rev. 2014 Jul;8(16):73-80. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.134229, PMID 25125878.

Zern TL, Fernandez ML. Cardioprotective effects of dietary polyphenols. J Nutr. 2005 Oct 1;135(10):2291-4. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2291, PMID 16177184.

Dec GW. Digoxin remains useful in the management of chronic heart failure. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87(2):317-37. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00172-4, PMID 12693728.

Neal B. Managing the global burden of cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2002;4:F2-6. doi: 10.1016/S1520-765X(02)90022-2.

Reddy KS. Cardiovascular diseases in the developing countries: dimensions determinants, dynamics and directions for public health action. Public Health Nutr. 2002 Feb;5(1A):231-7. doi: 10.1079/phn2001298, PMID 12027289.

Das DK. Natural products and healthy heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;54(5):366-8. doi: 10.1097/fjc.0b013e3181c6eeef, PMID 19998522.

Patil BS, Kanthe PS, Reddy CR, Das KK. Emblica officinalis (Amla) ameliorates high-fat diet-induced alteration of cardiovascular pathophysiology. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2019;17(1):52-63. doi: 10.2174/1871525717666190409120018, PMID 30963985.

Priya LB, Baskaran R, Elangovan P, Dhivya V, Huang CY, Padma VV. Tinospora cordifolia extract attenuates cadmium-induced biochemical and histological alterations in the heart of male wistar rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017 Mar;87:280-7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.098, PMID 28063409.

Pastorino G, Cornara L, Soares S, Rodrigues F, Oliveira MB. Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra): a phytochemical and pharmacological review. Phytother Res. 2018;32(12):2323-39. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6178, PMID 30117204.

Ojha S, Golechha M, Kumari S, Bhatia J, Arya DS. Glycyrrhiza glabra protects from myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by improving hemodynamic biochemical histopathological and ventricular function. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2013;65(1-2):219-27. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2011.08.011, PMID 21975080.

Dwivedi S, Chopra D. Revisiting terminalia arjuna an ancient cardiovascular drug. J Tradit Complement Med. 2014;4(4):224-31. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.139103, PMID 25379463.

Visavadiya NP, Narasimhacharya AV. Hypocholesteremic and antioxidant effects of Withania somnifera (Dunal) in hypercholesteremic rats. Phytomedicine. 2007;14(2-3):136-42. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.03.005, PMID 16713218.

Suchalatha S, Srinivasan P, Devi CS. Effect of Terminalia chebula on mitochondrial alterations in experimental myocardial injury. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;169(3):145-53. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2007.06.034, PMID 17678884.

Kubavat JB, Asdaq SM. Role of Sida cordifolia L. leaves on biochemical and antioxidant profile during myocardial injury. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124(1):162-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.04.004, PMID 19527827.

Reshma PL, Binu P, Anupama N, Vineetha RC, Abhilash S, Nair RH. Pretreatment of Tribulus terrestris L. causes anti-ischemic cardioprotection through MAPK-mediated anti-apoptotic pathway in rat. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019 Mar 1;111:1342-52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.01.033, PMID 30841448.

Karmakar UK, Rahman KS, Biswas NN, Islam MA, Ahmed MI, Shill MC. Antidiarrheal, analgesic and antioxidant activities of Trapa bispinosa roxb. fruits. Res J Pharm Technol. 2011;4(2):294-7.

Physician’s Desk Reference. 43rd ed. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Publishing Company; 1989. p. 1648.

Rossier MF, Python CP, Capponi AM, Schlegel W, Kwan CY, Vallotton MB. Blocking T-type calcium channels with tetrandrine inhibits steroidogenesis in bovine adrenal glomerulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1993;132(3):1035-43. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.3.8382595, PMID 8382595.

Kawashima K, Hayakawa T, Miwa Y, Oohata H, Suzuki T, Fujimoto K. Structure and hypotensive activity relationships of tetrandrine derivatives in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Gen Pharmacol. 1990 Jan 1;21(3):343-7. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(90)90835-a, PMID 2187737.

Kuramochi T, Chu J, Suga T. Gou-teng (from Uncaria rhynchophylla Miquel) induced endothelium-dependent and independent relaxations in the isolated rat aorta. Life Sci. 1994;54(26):2061-9. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00715-2, PMID 8208063.

Jaffe AM, Gephardt D, Courtemanche L. Poisoning due to ingestion of Veratrum viride (false hellebore). J Emerg Med. 1990;8(2):161-7. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(90)90226-l, PMID 2362117.

Ody P. The complete medicinal herbal. New York: Dorling Kindersley; 1993.

Lei XL, Chiou GC. Cardiovascular pharmacology of panax notoginseng (burk) F.H. chen and salvia miltiorrhiza. Am J Chin Med. 1986;14(3-4):145-52. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X86000235, PMID 3799531.

Steiner M, Khan AH, Holbert D, Lin RI. A double-blind crossover study in hypercholesterolemic men that compared the effect of aged garlic ex-tract and placebo administration on blood lipids. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 Dec;64(6):866-70. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.6.866.

Singh V, Kaul S, Chander R, Kapoor NK. Stimulation of low density lipoprotein receptor activity in liver membrane of guggulsterone-treated rats. Pharmacol Res. 1990;22(1):37-44. doi: 10.1016/1043-6618(90)90741-u, PMID 2330337.

Nityanand S, Srivastava JS, Asthana OP. Clinical trials with gugulipid a new hypolipidaemic agent. J Assoc Physicians India. 1989;37(5):323-8. PMID 2693440.

Sundaram V, Hanna AN, Lubow GP, Koneru L, Falko JM, Sharma HM. Inhibition of low-density lipoprotein oxidation by oral herbal mixtures maharishi amrit kalash-4 and Maharishi Amrit Kalash-5 in hyperlipidemic patients. Am J Med Sci. 1997;314(5):303-10. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199711000-00007, PMID 9365332.

Senthilkumar GP, Moses MF, Sengottuvelu S, Rajarajan T, Saravanan G. Cardioprotective activity of garlic (Allium sativum) in isoproterenol induced rat myocardial necrosis: a biochemical and histoarchitectural evaluation. PCI- Approved-IJPSN. 1970;2(4):779-84. doi: 10.37285/ijpsn.2009.2.4.14.

Shanmugarajan T, Arunsundar M, Somasundaram I, Krishnakumar E, Sivaraman D, Ravichandiran V. Cardioprotective effect of Ficus hispida Linn on cyclophosphamide provoked oxidative myocardial injury in a rat model. Int J Pharmacol. 2008;4(2):78-87. doi: 10.3923/ijp.2008.78.87.

Velavan S, Selvarani S, Adhithan A. Cardioprotective effect of Trichopus zeylanicus against myocardial ischemia induced by isoproterenol in rats. Bangladesh J Pharmacol. 2009;4(2):88-91. doi: 10.3329/bjp.v4i2.1824.

Sailaja KV, Shivaranjani VL, Poornima H, Rahamathulla SB, Devi KL. Protective effect of Tribulus terrestris L. fruit aqueous extract on lipid profile and oxidative stress in isoproterenol-induced myocardial necrosis in male albino Wistar rats. Excli J. 2013 May 6;12:373-83. PMID 26417233.

Chakraborty M, Asdaq SM. Interaction of Semecarpus anacardium L. with propranolol against isoproterenol-induced myocardial damage in rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 2011;49(3):200-6. PMID 21452599.

Mehdizadeh R, Parizadeh MR, Khooei AR, Mehri S, Hosseinzadeh H. Cardioprotective effect of saffron extract and safranal in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in wistar rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2013;16(1):56-63. PMID 23638293.

Sharma M, Kishore K, Gupta SK, Joshi S, Arya DS. Cardioprotective potential of Ocimum sanctum in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;225(1):75-83. doi: 10.1023/a:1012220908636, PMID 11716367.

Kauser A, Shah SM, Iqbal N, Murtaza MA, Hussain I, Irshad A. In vitro antioxidant and cytotoxic potential of methanolic extracts of selected indigenous medicinal plants. Prog Nutr. 2018 Dec 1;20(4):706-12. doi: 10.23751/pn.v20i4.7523.

Upaganlawar A, Balaraman R. Cardioprotective effects of lagenaria siceraria fruit juice on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in wistar rats: a biochemical and histoarchitecture study. J Young Pharm. 2011;3(4):297-303. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.90241, PMID 22224036.

Senthil Kumar SH, Anandan R, Devaki T, Santhosh Kumar M. Cardioprotective effects of Picrorrhiza kurroa against isoproterenol-induced myocardial stress in rats. Fitoterapia. 2001;72(4):402-5. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(01)00264-7, PMID 11395263.

Beaulah A, Sadiq M, Sivakumar V, Santhi J. Cardioprotective activity of methanolic extract of Croton sparciflorus on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarcted wistar albino rats. J Med Plants Stud. 2014;2(6):1-8.

Peer PA, Trivedi PC, Nigade PB, Ghaisas MM, Deshpande AD. Cardioprotective effect of Azadirachta indica A. Juss. on isoprenaline-induced myocardial infarction in rats. Int J Cardiol. 2008;126(1):123-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.01.108, PMID 17467089.

Ahsan F, Siddiqui HH, Mahmood T, Srivastav RK, Nayeem A. Evaluation of cardioprotective effect of coleus forskohlii against isoprenaline-induced myocardial infarction in rats. IJPBR. 2014;2(1):17-25. doi: 10.30750/ijpbr.2.1.3.

Yamashiro S, Noguchi K, Matsuzaki T, Miyagi K, Nakasone J, Sakanashi M. Cardioprotective effects of extracts from Psidium guajava L. and Limonium wrightii okinawan medicinal plants against ischemia reperfusion injury in perfused rat hearts. Pharmacology. 2003;67(3):128-35. doi: 10.1159/000067799, PMID 12571408.

Pragada RR, Veeravalli KK, Chowdary KP, Routhu KV. Cardioprotective activity of Hydrocotyle asiatica L. in ischemia-reperfusion induced myocardial infarction in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93(1):105-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.025, PMID 15182913.

Karthikeyan K, Bai BR, Gauthaman K, Sathish KS, Devaraj SN. Cardioprotective effect of the alcoholic extract of Terminalia arjuna bark in an in vivo model of myocardial ischemic reperfusion injury. Life Sci. 2003;73(21):2727-39. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00671-4, PMID 13679240.

Firoz M, Bharatesh K, Nilesh P, Vijay G, Tabassum S, Nilofar N. Cardioprotective activity of ethanolic extract of Callistemon lan-ceo latus leaves on doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in rats. Bangl J Pharmacol. 2011;6(1):38-45. doi: 10.3329/bjp.v6i1.8154.

Thippeswamy AH, Shirodkar A, Koti BC, Sadiq AJ, Praveen DM, Swamy AH. Protective role of Phyllantus niruri extract in doxorubicin induced myocardial toxicity in rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011 Jan 1;43(1):31-5. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.75663, PMID 21455418.

El Sayed EM, El Azeem AS, Afify AA, Shabana MH, Ahmed HH. Cardioprotective effects of Curcuma longa L. extracts against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5(17):4049-58.

Ashour OM, Abdel Naim AB, Abdallah HM, Nagy AA, Mohamadin AM, Abdel Sattar EA. Evaluation of the potential cardioprotective activity of some Saudi plants against doxorubicin toxicity. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2012;67(5-6):297-307. doi: 10.1515/znc-2012-5-609, PMID 22888535.

Obouayeba AP, Meite S, Boyvin L, Yeo D, Kouakou TH, N Guessan JD. Cardioprotective and anti-inflammatory activities of a polyphenol-enriched extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa petal extracts in wistar rats. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2015;4(1):57-63.

Khan G, Haque SE, Anwer T, Ahsan MN, Safhi MM, Alam MF. Cardioprotective effect of green tea extract on doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Acta Pol Pharm. 2014;71(5):861-8. PMID 25362815.

Liu C, Huang Y. Chinese herbal medicine on cardiovascular diseases and the mechanisms of action. Front Pharmacol. 2016 Dec 1;7:469. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00469, PMID 27990122.