Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 3, 10-17Review Article

GELATIN-BASED DRUG DELIVERY NANOSYSTEM FOR ONCOLOGY

VAISHNAVI S. JAISWAL*, MRUNAL KOLHE, DHIRAJ KHAMBAYAT, PURVA PAPRIKAR

Shastry Institute of Pharmacy, Erandol, Maharashtra, India

*Corresponding author: Vaishnavi S. Jaiswal; *Email: vj4771231@gmail.com

Received: 25 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 14 Mar 2025

ABSTRACT

Drug delivery nanosystems (DDnS) have seen significant advancements recently. Gelatin, a highly promising biomaterial derived from natural sources, is utilized in anticancer DDnS, enhancing the efficacy of anticancer medications while minimizing side effects. The hydrophilic and amphoteric properties of gelatin, along with its sol-gel transition, enable it to meet various demands in anticancer drug delivery nanosystems. Regarding the latter, the focus is on the application of gelatin in fields of science and technology related to the unique spatial/molecular structure of this high-molecular compound, such as protein-based nanosystems, immobilized matrix systems that organize an immobilized substance at the nanoscale, matrices for the creation of pharmaceutical/dosage forms.

Keywords: Biomaterial, Gelatin, Nanoparticles, Cancer, Oncology

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i3.55044 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

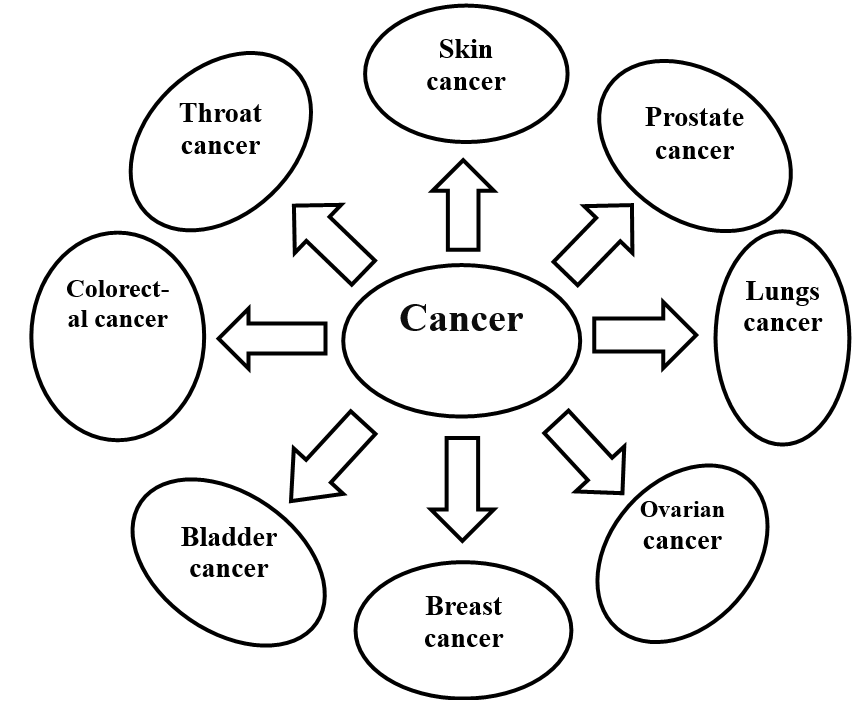

Every year, cancer claims millions of lives and is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. People's lives have been severely impacted by the suffering and high expense of cancer treatment [1]. Alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, inadequate diet, a lack of physical activity, pollution, and non-communicable diseases are all considered human cancer risk factors. Chronic illnesses such as Epstein-Barr virus, human papillomavirus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and H. pylori are also regarded as risk factors for cancer [2]. Cancer is a broad term used to describe a variety of diseases marked by genetic alterations and cellular abnormalities that cause unchecked cell division and the spread of aberrant cells. After heart disease, cancer is the second leading cause of death [3].

In this instance, medical research has focused heavily on cancer treatment. Anticancer medications have many adverse effects and are quite hazardous when used to treat cancer. However, these medications might not be taken as prescribed. It depletes medications and could endanger the health of other organs or tissues [1]. Disease site-specificity by active targeting is crucial for cancer treatment because it increases medication uptake and tumor cytotoxicity while also lowering adverse effects [4].

A relatively new scientific subject called "nanomedicine," which depends on using nanoparticles for illness diagnosis, imaging, monitoring, and treatment, has arisen in the gradual path towards the realization of modern tailored medicine. Nanoparticles between 10 and 100 nm in size are thought to be highly beneficial for medication delivery applications. An adequate size range is crucial for cancer targeting because if they are smaller than 10 nm, they would be promptly removed from the bloodstream by the kidneys, and if they are larger than 100 nm, the reticuloendothelial system (RES) may quickly identify and eradicate them. Drug delivery nanomaterials can be classified as either organic or inorganic. While organic nanocarriers, such as liposomes, dendrimers, and micelles, are highly biocompatible and biodegradable, they typically have low drug-loading capacities and decreased stability. In contrast, inorganic nanocarriers, such as metallic and carbon nanoparticles, are more stable and have multifunctional properties, but they are also less biocompatible and biodegradable [5].

Gelatin is utilized to make controlled and targeted drug-release vehicles for diseases, including cancer. Gelatin is an animal protein that has been refined using partial alkaline and acid hydrolysis, enzymatic hydrolysis, or thermal hydrolysis of collagen from fish and poultry (USP-NF). Water (8–15%) and water-soluble proteins combine to form gelatin [6]. In order to create controlled-release products for pharmaceutical and medical applications, it is frequently utilized to immobilize medications and genes.

Its biodegradability, biocompatibility, and water solubility Gelatin is non-toxicity, cross-linking, and simplicity of chemical modification make it perfect for use in drug delivery vehicle systems such as gelatin-based nanoparticles. Additionally, it may be a good option for iron oxide surface modification [7].

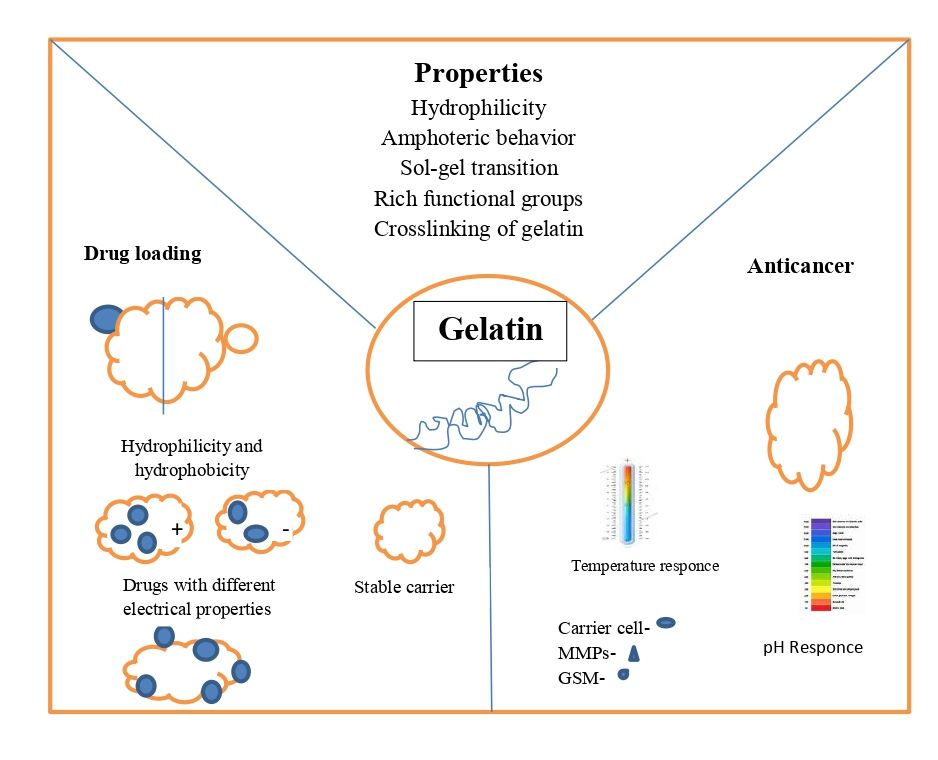

Here, our goal is to associate gelatin's physicochemical characteristics with anticancer DDnS for various cancer treatment modalities. We examine and condense the benefits and responsiveness of gelatin as a drug carrier, as well as its particular uses in the delivery of anticancer medications [1]. As per given fig. 1.

Fig. 1: Properties of gelatin

Properties of gelatin for an anticancer DDnS

Hydrophilic properties

The surface of the gelatin molecular chain is composed of amino acids that resemble collagen and has a large number of hydrophilic groups that readily form hydrogen bonds. As a result, gelatin readily binds to drug molecules and is extremely water-soluble.

Employed polyhydroxy butyric acid/gelatin nanofibers to release methotrexate (MT), a less hydrophilic drug, and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), a very hydrophilic drug. When they investigated the release of two drug kinds with distinct hydrophilic characteristics, they found that the more hydrophilic 5-FU was released sooner and more quickly than MT. Both MT and 5-FU showed a steady release rate after 24 to 96 h, which can successfully satisfy the requirements of various medication kinds in the post-operative therapy of cancer [8]. Gelatin's hydrophilic qualities can be changed to cause it to self-assemble and release drugs as micelles or polymer vesicles and colleagues made the emulsion by mixing 25–30 weight percent polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) solution with gelatin solution. 97% of the loaded MT medicine will be released within 10 days if the MT adsorbed on the gelatin surface is released within 10 h and the gelatin gradually swells over the next 30 h. Additionally, by increasing hydrophilicity, gelatin can be used to alter other anticancer drug delivery vehicles to successfully increase stability in vivo [9].

It can improve how well cancer cells absorb drugs. Likewise, gelatin might be utilized to improve graphene materials' durability in vivo by using hydrophobic interactions on the surface of graphene [10].

Amphoteric behaviour

Gelatin has various isoelectric points and behaves amphoterically. During the hydrolysis reaction, the majority of the collagen's amino acids were preserved, and it includes many functional groups, including hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amino groups Alkaline gelatin (type B), for instance, has an isoelectric point between pH 4.8 and 5.0. Aspartic acid and glutamic acid are produced from asparagine and glutamine in an alkaline environment. Considering that amide is present With carboxyl groups, gelatin is a polyampholyte that displays a range of characteristics and configurations in varying pH ranges [11]. Gelatin can carry anticancer medications with various charges thanks to its amphoteric nature examined DOX's loading behavior, which revealed a positive charge and was difficult to load on identically charged materials. Nonetheless, it can be transported as charged amphiphiles on gelatin-based substrates. Gelatin effectively increases the hydrophilic and anticancer drug-loading capability of the composites. After loading DOX onto the gelatin-based nanofibers, Benjamin et al. observed a notable drop in zeta potential, confirming gelatin's ability to load this kind of medication [12].

Sol-gel transition

Gelatin is a type of thermosensitive substance that reacts strongly to heat, usually through a sol-gel transition. But it's essential to modify the temperature range of Gelatin sol-gel transition to regulate the release of anticancer drugs by temperature response Gelatin and Poly N-isopropyl acrylamide (PNIPAM) nanofibers with thermo responsive swelling/deswelling properties. When the fibers are loaded with the anticancer medication DOX, the temperature increases can cause a considerable release of DOX, which effectively lowers the viability of human cervical cancer cells [13].

The trigger signals for DDnS that are most frequently used across all response kinds. In addition to cancer treatment, a variety of temperature-responsive medication carriers are frequently employed. A DOX gelatin-based nanodrug delivery vehicle that reacts to temperature has been created [1].

Crosslinking of gelatin

The gelatin microspheres may dissolve prior to medication delivery due to their high water solubility. Nanomaterial stability for carriers and control can be enhanced by crosslinking the drug's release. It falls into one of three categories: chemical, enzymatic, or physical approaches. The majority of the reaction sites for DDnS, a gelatin-based substance, arecarboxyl and amino groups. Generally, natural polymers or extracts based on oxidized polysaccharides or non-toxic genipin.

The CTC release behavior of gelatin hydrogels is not significantly impacted by genipin crosslinking. In the meantime, the gelatin hydrogel layer reduces the rate at which Diclofenac is released medication from within the nanofibers. To meet the need for long-term release of anticancer medications, the thickness of the hydrogel can be adjusted to manage the composite's drug release rate. Additionally, gelatin can be converted into photo-crosslinked materials through grafting using methacryloyl groups. Both photo-chemical and cross-linking reactions follow UV light irradiation, making hydrogel DDnS formulation appropriate for minimally invasive cancer treatment [14].

Chemical crosslinkers come in two varieties: non-zero-length and zero-length. By bridging free amine groups, non-zero-length crosslinkers are incorporated into the biomaterial of the protein molecules' free carboxylic acid residues of glutamic and aspartic acid or lysine and hydroxylysine. Polyepoxides, isocyanates, and aldehydes (formal, glutaral, and glyceral) are frequently employed as crosslinkers [4].

Types of drugs delivery nanosystem

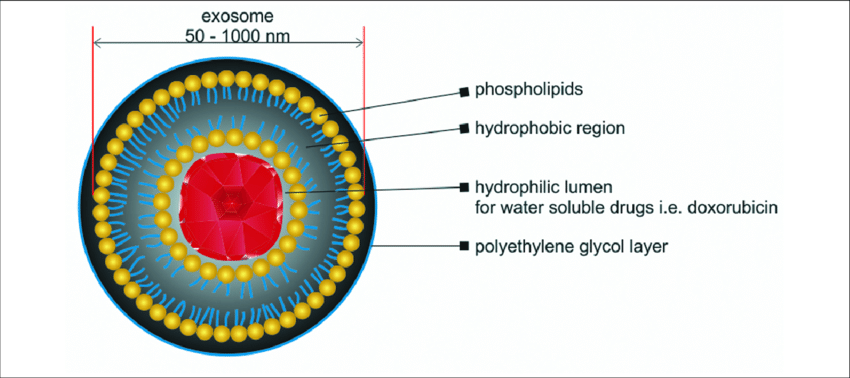

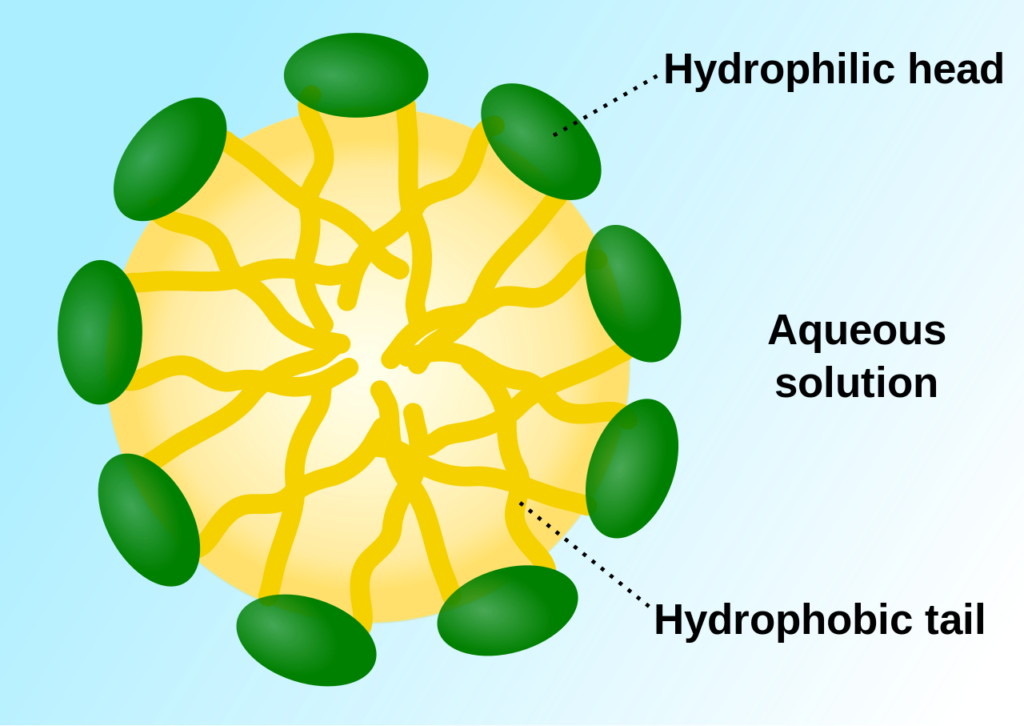

Liposomes

Spherical vesicles called liposomes are made up of one or more lipid bilayers that separate their aqueous contents from the surrounding media. Dr. Alec D. Bingham, a British biophysicist, made the unintentional discovery of them in the 1960s. He found that adding water to the phospholipid phosphatidylcholine resulted in the formation of a closed bilayer structure.

Liposomes consist of phospholipids, such as those found in soybeans, egg yolks, and other natural sources, can be synthesized or extracted. Egg phosphatidylcholine (EPC) and soy phosphatidylcholine (SPC) are examples of natural phospholipids, while dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) and dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC) are examples of synthetic phospholipids. Every phospholipid molecule consists of a hydrophilic head group made up of serine, choline, ethanolamine, or inositol and two hydrophobic tails [15].

A wide range of bioactive substances, including genes, viruses, medications, DNA, proteins, vaccines, and enzymes, can be transported by liposomes due to their special structure. Furthermore, because they may enclose radioactive molecules, they can also be utilized for molecular imaging [16].

There are currently a number of authorized liposomal cancer medicines on the market, such as Doxil®, Depocyt®, and Marqibo®. Clinical trials have been conducted on a number of different formulations to evaluate their effectiveness in treating cancer [17].

Fig. 2: Structure of liposome

Transfersome

The conventional liposomes are limited to the stratum corneum's outer layer and cannot penetrate the skin deeply. Consequently, novel lipid vesicle classes such as an improved form of liposomes, transferosomes are an ultra-flexible lipid-based elastic vehicle with highly deformable membranes that improve the delivery of materials to deeper skin tissues via a no noccluded technique that enters the stratum corneum's intercellular lipid lamellar regions because of the skin's osmotic force or hydration [18].

It is made up of phospholipid and a single-chain surfactant that gives the vesicles their flexibility and deformability so they can be applied topically to provide nutrients locally to support skin health. However, due to their susceptibility to oxidative destruction and the purity of natural phospholipid, transfersomes are not chemically stable. Another factor working against the use of transfersomeas drug delivery vehicles is phospholipids [19].

The differential in water concentration between the skin's surface and inside is what causes the osmotic gradient. Because of their high degree of deformation, transfersomes can quickly pass through the subcutaneous tissue's intercellular lipid route. Some of the preliminary research revealed that there are wrongdoings within the intercellular lipid packing of the subcutaneous tissue of mice, which serves as the virtual conduit for transfersome penetration [20].

According to one definition, transfersomes are specialized vesicular particles with at least one inner watery compartment encased in lipid vesicles; they resemble liposomes in appearance, but transfersomes can be appropriately deformed to pass through pores that are far smaller than themselves. An illustration showing the structure of transfersomes [21] is presented in fig. 3.

Fig. 3: Structure of transfersome

Niosomes

Although niosomes and liposomes are structurally nearly identical, niosomes have greater penetration power, greater stability and therapeutic index of medicine, and lower toxicity; hence, they could provide more benefits than liposomes. Niosome's benefits include its excellent solubility, affordability, and flexibility and regulated content release. As a result, they are frequently used as a neoplasia targeting vehicle or as a hemoglobin, peptide, or transdermal delivery system [22].

Niosomes also demonstrated extended circulation, sustained release, and retention in the skin in tropical applications, which helped the medication penetrate the skin. When applied topically to treat skin conditions, niosomes have been shown to be more stable and less harmful than liposomes [23].

Niosome-loaded resveratrol is one possible option in this respect for the topical treatment of skin malignancies 99,100 in a similar vein. A croton oil-induced ear edema paradigm in male ICR mice was used to develop the topical gel from Zingibercassumunar Roxb. extract loaded niosome for anti-inflammatory activity-enhanced skin penetration and stability of component D [24] as per fig. 4.

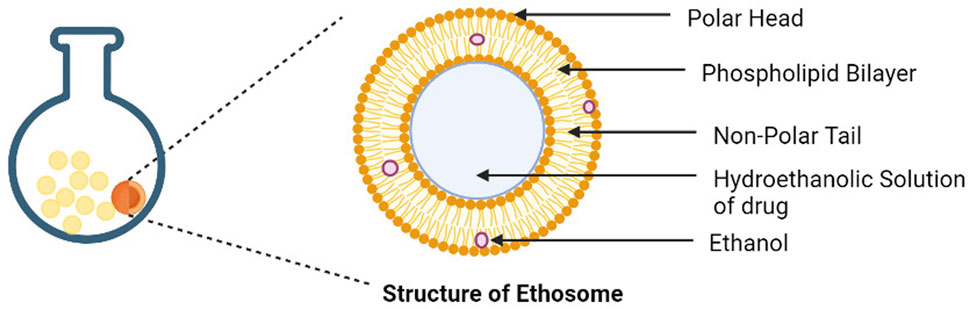

Ethosomes

Developed for topical, transdermal, and systemic applications, this novel liposome is characterized as a soft, non-invasive lipid-based elastic vesicle with a high efficiency of both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs, as well as active ingredient delivery to deeper skin layers and blood circulation [25].

Water and specific phospholipids (phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylglycerol) make up an ethersome. Additionally, a considerably elevated alcohol content (30–45%) (ethanol and isopropyl alcohol)

Higher ethosome deformability and entrapment efficiency are provided by this composition, improving topical medication administration of highly concentrated active components, transdermal transport effectiveness, and, in contrast to liposomes, extends the ethosomes' physical stability through the flexibility of the lecithin bilayer [26] as per fig. 5.

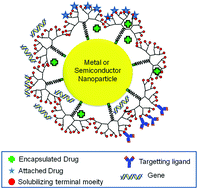

Dendrimers

A dendrimer is a synthetic polymer that resembles a tree and is defined by a single central core that frequently produces branches of macromolecules with different arms (multifunctional groups and external capping) (fig. 6) to improve targeting to certain spots. Typically, they consist of manufactured or natural substances, including sugars, amino acids, and nucleotides [27]. This polymer's structure and hydrophilicity can be readily controlled during synthesis to provide greater solubility, permeability, and biocompatibility, which makes it unique. Biodistribution, elimination, and hence lowering adverse effects.

Immediately, because polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers may be created in a variety of sizes, geometries, and surfaces, they have lately been investigated as carriers to obtain nanoscale functionalized formulae [28].

This dendrimer can, therefore, provide target ligands to encourage specific binding to biological receptors. Furthermore, the tiny due to its size, this dendrimer can quickly leave the body through the kidneys and bypass the reticuloendothelial system. Additionally, PAMAM dendrimers' wide interior holes enable them to compound hydrophobic medications via either a covalent or non-covalent combination [29]

As a result, they discovered that all generations with the corresponding PAMAM dendrimer concentrations demonstrated possible advantages for improving solubility and quercetin in vitro. A micelle schematic illustration efficient application of nanocarriers as medication delivery vehicles for the management of specific cancers dual releasing pattern, with a longer sustained release after a faster initial release. Additionally, the effectiveness of this dendrimer in assessing the acute activity of this nanocarrier in response to inflammation was assessed using a carrageenan-induced paw edema model [30] as per fig. 6.

Fig. 4: Structure of noisome

Fig. 5: Structure of ethosome

Fig. 6: Structure of dendrimers polymeric micelle

Amphiphilic block copolymers self-assemble in aqueous conditions to create polymeric micelles, which are an aggregate of colloids. The inner core of these micelles is hydrophobic, whereas the outside shell is hydrophilic. It has been claimed that polymeric micelles have a number of benefits over other nanocarriers. These molecules' high molecular weight prevents them from dissociating instantly upon dilution. They are, therefore far more stable than micelles with smaller molecular weights. Additionally, they can circulate for extended periods of time and are quite stable in the bloodstream [31].

When stored, they also have a longer shelf life. Since polymeric micelles are typically between 15 and 30 nm in size, they can evade renal elimination and gather at the location of the tumor straightforward methods make it straightforward to load medications and small compounds into these micellar structures. Additionally, the majority of the polymers utilized to create micelles are low-cost and non-toxic [21].

However, the quick removal of polymeric micelles from the bloodstream is a major disadvantage. By covering the micellar structure with an outer layer of polyethylene oxide (PEO)/polyethylene glycol (PEG), this can be avoided. Protein adsorption on the micellar surface is reduced as a result of PEG's hydrophilic character, which makes it bind with water molecules. This implies they can evade phagocytosis and remain in the bloodstream for extended periods of time [32].

Because polymeric micelles may easily penetrate tissue without being detected by the immune system, they are widely used as nanocarriers for drug delivery. They also have outstanding biodegradability and drug-loading efficiency. If taken orally, polymeric micelles may occasionally be broken down by digestive enzymes. Numerous investigations have been carried out to evaluate the effectiveness of cancer-targeting cells using polymeric micelles' assistance as per fig. 4 [33].

Fig. 4: Structure of polymeric micelle

Table 1: Drug delivery systems comprising nanovesicular carriers

| Type of gelatin drug delivery system | Drug used | Treatment | Types | Reference |

| Liposomes | 5-Fluorouracil | HT-29 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (non-small cell lung cancer) | Alginate | [34] |

| Doxorubicin | HepG2 hepatoma (liver cancer) | Glycyrrhetinic acid/triphenylphosphine liposome | [34] | |

| Curcumin | A2780 (ovarian cancer) | DMPC/DMPC cholesterol liposomes | [35] | |

| Doxorubicin and Paclitaxel | MCF-7 (breast cancer) | Hyaluronic acid-liposomes | [35] | |

| Neosomes | Rosmarinic acid | Creation of an acneniosomalgelofrosmarinic acid | [36] | |

| Gallic acid | Creation of a Gallic Acid-Loaded Ionic cetrimonium bromide surfactant niosomes for anti-aging properties |

[37] | ||

| Ethosomes | Gamma oryzanol | Creation of ethosomes that contain gamma Oryzanol for wrinkle repair and skin aging prevention | [38] | |

| Dendrimers | Vismodegib | HaCaT (skin cancer) | PAMAM-D | [39] |

| Paclitaxel and Sorafenib co-delivery | HepG2 (liver cancer) | PLA and HA-modified PAMAM G4.5 | ||

| Polymeric Micelle | Paclitaxel | SGC7901 (gastric cancer) | RGD PEG-PTX polymeric micelle | [40] |

| Cabazitaxel | C4-2 (prostate cancer) | PEG-cholesterol polymeric micelle |

Skin cancer

Skin cancer is the sixth most common type of cancer worldwide, and its prevalence is steadily rising. One common and hazardous malignancy in people is skin cancer. The two most prevalent forms of skin cancer are non-cancer skin tumors, which originate from epidermal cells, and melanoma, which are malignancies caused by malfunctioning melanocytes. Ninety-five percent of skin malignancies are not melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) brought on by both natural and hereditary causes. Although there are many different forms of non-melanoma skin cancer, they can be categorized into two primary subgroups. 99 percent of all NMSCs are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

Numerous nanoparticles, such as lipid-, protein-, polymer-, dendrimer-, carbon-, and inorganic nanoparticles, as well as superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPION) nanoparticles, have been used to treat skin cancer thus far. Over the past few years, lipid-based although vesicles have gained popularity as a way to apply medications topically, their application is still difficult. The most widely utilized lipid-based nanoparticles for the treatment of skin cancer are examined in this review [41].

Researchers are investigating the use of nanoparticles to identify melanoma and assess its stage of development. For patients with melanoma to have a decent chance of survival, early identification is essential. In addition to histological analysis and visual assessment, a number of new Numerous diagnostic techniques have been developed, such as RNA microarray, multispectral digital image analysis, dermoscopy, whole-body photography, and reflectance confocal microscopy [42].

Fig. 5: Application for different kinds of cancer

Breast cancer

In the United States and other nations, breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women. Just in the USA, It is anticipated that 249,000 new invasive breast cancer cases and roughly 61,000 new in situ breast cancer cases, or nearly one in three cancer cases, occurred in 2016. The primary cause of cancer death for women between the ages of 20 and 59 is breast cancer, which is also the second most common cause of cancer death for women 60 and older, after lung and bronchus cancer [43].

One of the main causes of death for women globally is breast cancer. Unchecked growth of breast epithelial cells makes it possible to employ both chemical and intrinsic cues (such as pH) and drug carriers in therapy use extrinsic/physical stimuli, such as heat, as stimulus-response signals. For the delivery of medications used to treat breast cancer, gelatin is the perfect preparation material [44].

Cancer nanomedicine has significantly advanced the development of cancer treatments, which is an interdisciplinary field that focuses on designing and using nanoscale (usually up to 100 nm) materials and technologies for medical purposes. Increased biocompatibility, multifunctional encapsulation of active compounds, less degradation during blood circulation, passive or active targeting, effective administration, and decreased or eliminated adverse effects are just a few of the possible advantages offered by nanoparticulate-based delivery methods [45].

Lung cancer

Clinical care of lung cancer remains a challenging issue in spite of the advancements in oncological sciences. Abstruseness in the current scene is examined in this essay scenario of managing lung cancer and talks about nanobioengineering techniques to get around it. A thorough review of the bio-nanotools (bio-nanocarriers and nano-biodevices) for various lung cancer applications has been provided, along with a comparative analysis of the main benefits and drawbacks. Prophylaxis/prevention, diagnosis, treatment/therapeutics, and therapeutic medication monitoring (aided by theranostics) are the four (quadripartite) distinct components of disease management in the clinical setting. A critical evaluation of the literature on the use of bio-nanotools for each of these lung cancer treatment facets has been developed [46].

Gelatin is a polyampholyte that possesses hydrophobic and cationic groups in roughly a 1:1:1:1 ratio, which may improve its capacity to load both hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules medications that cause drophobic additionally, its functional groups are readily available and chemically modifiable, a characteristic that could be helpful in creating targeted drug delivery systems. Collagenase enzymes may easily break down gelatin, a denatured protein. Furthermore, compared to collagen, it has reduced antigenicity Hathout and the capacity for chemical modification, cross-linking, biodegradability, and biocompatibility all contribute to the potential of gelatin-based nanoparticles (GNPs) as a drug delivery vehicle [47].

Colorectal cancer

One of the most prevalent types of gastroenteric cancer in the world is colorectal cancer (CRC), a malignant tumor that begins in the colon or rectum. About 35% of the over 150,000 new patients diagnosed each year in the USA will pass away from colorectal cancer. The reason behind CRC is not entirely understood; it is thought to be complex, and a body of research indicates that the disease is associated with specific risk factors. For instance, there is evidence linking the development of colon cancer to lifestyle factors (diet, smoking, and alcohol use), genetic factors (family history, inherited syndromes, racial and ethnic background), and other medical histories (inflammatory bowel diseases, colon polyps, obesity, and type II diabetes) [48].

The pH of the medium affected the drug release, indicating that the produced hydrogel drug carriers might release the medication in a selective manner in the mucosal base of the colon and the rectal cavity. Additionally, the hydrogel drug carrier's drug loading rate increased as the dosage of gelatin rose [1].

CONCLUSION

Gelatin-based drugs delivery nanosystems are a promising approach to cancer treatment because they can impove the effectiveness of cancer drugs and reduce the side effects. Gelatin nanoparticles can be modified with ligands to target specific cell and they can be designed to release the drugs in a controlled and sustained manner. Gelatin’s Properties are allow it to bind to the drugs molecules and it can enhance the process of the drug by cancer cell.

Gelatin can be used as a drugs delivery system for cancer treatment because it’s biocompatible, biodegradable and can be responsive to environmental changes. Gelatin-based drug delivery systems can be improve the efficacy of drugs and reduce their side effects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors like to express our sincere appreciation to everyone who contributed to the successful completion of this review article. Our deepest thanks to our institute ‘Shastry Institute of Pharmacy Erandol’ and also greatful to our friends and guide ‘Miss. purvapaprikar’ for their valuable guidance and constant support throughout this review article.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Jiang X, DU Z, Zhang X, Zaman F, Song Z, Guan Y. Gelatin based anticancer drug delivery nanosystems: a mini review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1158749. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1158749, PMID 37025360.

Chavda VP, Patel AB, Mistry KJ, Suthar SF, WU ZX, Chen ZS. Nano drug delivery systems entrapping natural bioactive compounds for cancer: recent progress and future challenges. Front Oncol. 2022;12:867655. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.867655, PMID 35425710.

Majidzadeh H, Araj Khodaei M, Ghaffari M, Torbati M, Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J, Hamblin MR. Nano-based delivery systems for berberine: a modern anti-cancer herbal medicine. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2020;194:111188. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111188, PMID 32540763.

Meghani NM, Amin HH, Park C, Park JB, Cui JH, Cao QR. Design and evaluation of clickable gelatine oleic nanoparticles using fattigation platform for cancer therapy. Int J Pharm. 2018;545(1-2):101-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.04.047, PMID 29698822.

Ajith S, Almomani F, Elhissi A, Husseini GA. Nanoparticle-based materials in anticancer drug delivery: current and future prospects. Heliyon. 2023;9(11):e21227. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21227, PMID 37954330.

Gullapalli RP, Mazzitelli CL. Gelatin and non-gelatin capsule dosage forms. J Pharm Sci. 2017;106(6):1453-65. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.02.006, PMID 28209365.

Hamarat Sanlıer S, Yasa M, Cihnioglu AO, Abdulhayoglu M, Yılmaz H, Ak G. Development of gemcitabine adsorbed magnetic gelatin nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery in lung cancer. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2016;44(3):943-9. doi: 10.3109/21691401.2014.1001493, PMID 25615875.

Han S, LI M, Liu X, Gao H, WU Y. Construction of amphiphilic copolymer nanoparticles based on gelatin as drug carriers for doxorubicin delivery. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013 Feb 1;102:833-41. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.09.010, PMID 23107962.

Cascone MG, Lazzeri L, Carmignani C, Zhu Z. Gelatin nanoparticles produced by a simple W/O emulsion as delivery system for methotrexate. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2002;13(5):523-6. doi: 10.1023/a:1014791327253, PMID 15348607.

Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science. 2004;303(5665):1818-22. doi: 10.1126/science.1095833, PMID 15031496.

Alipal J, Mohd PU’AD NA, Lee TC, Nayan NH, Sahari N, Basri H. A review of gelatin: Properties sources process applications and commercialisation. Mater Today Proc. 2021;42:240-50. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.12.922.

Zou Z, HE D, HE X, Wang K, Yang X, Qing Z. Natural gelatin capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles for intracellular acid triggered drug delivery. Langmuir. 2013;29(41):12804-10. doi: 10.1021/la4022646, PMID 24073830.

Slemming Adamsen P, Song J, Dong M, Besenbacher F, Chen M. In situ cross-linked PNIPAM/gelatin nanofibers for thermo-responsive drug release. Macromol Mater Eng. 2015;300(12):1226-31. doi: 10.1002/mame.201500160.

Esposito E, Cortesi R, Nastruzzi C. Gelatin microspheres: influence of preparation parameters and thermal treatment on chemico physical and biopharmaceutical properties. Biomaterials. 1996;17(20):2009-20. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)00325-8, PMID 8894096.

Bozzuto G, Molinari A. Liposomes as nanomedical devices. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015 Feb 2;10:975-99. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S68861, PMID 25678787.

Bangham AD, Standish MM, Watkins JC. Diffusion of univalent ions across the lamellae of swollen phospholipids. J Mol Biol. 1965;13(1):238-52. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80093-6, PMID 5859039.

Carugo D, Bottaro E, Owen J, Stride E, Nastruzzi C. Liposome production by microfluidics: potential and limiting factors. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25876. doi: 10.1038/srep25876, PMID 27194474.

Nagalingam A. Drug delivery aspects of herbal medicines. In: Japanese kampo medicines for the treatment of common diseases: focus on inflammation. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. p. 143-64. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809398-6.00015-9.

Prabhu RH, Patravale VB, Joshi MD. Polymeric nanoparticles for targeted treatment in oncology: current insights. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015 Feb 2;10:1001-18. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S56932, PMID 25678788.

Rai S, Pandey V, Rai G. Transfersomes as versatile and flexible nano vesicular carriers in skin cancer therapy: the state of the art. Nano Rev Exp. 2017;8(1):1325708. doi: 10.1080/20022727.2017.1325708, PMID 30410704.

Sarwa KK, Mazumder B, Rudrapal M, Verma VK. Potential of capsaicin loaded transfersomes in arthritic rats. Drug Deliv. 2015;22(5):638-46. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2013.871601, PMID 24471764.

Pando D, Matos M, Gutierrez G, Pazos C. Formulation of resveratrol entrapped niosomes for topical use. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2015;128:398-404. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.02.037, PMID 25766923.

Goyal G, Garg T, Malik B, Chauhan G, Rath G, Goyal AK. Development and characterization of niosomal gel for topical delivery of benzoyl peroxide. Drug Deliv. 2015;22(8):1027-42. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2013.855277, PMID 24251352.

Rameshk M, Sharififar F, Mehrabani M, Pardakhty A, Farsinejad A, Mehrabani M. Proliferation and in vitro wound healing effects of the microniosomes containing Narcissus tazetta L. bulb extract on primary human fibroblasts (HDFs). Daru. 2018;26(1):31-42. doi: 10.1007/s40199-018-0211-7, PMID 30209758.

Choi JH, Cho SH, Yun JJ, YU YB, Cho CW. Ethosomes and transfersomes for topical delivery of ginsenoside rhl from red ginseng: characterization and in vitro evaluation. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2015;15(8):5660-2. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2015.10462, PMID 26369134.

Limsuwan T, Boonme P, Khongkow P, Amnuaikit T. Ethosomes of phenylethyl resorcinol as vesicular delivery system for skin lightening applications. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8310979. doi: 10.1155/2017/8310979, PMID 28804723.

Madaan K, Kumar S, Poonia N, Lather V, Pandita D. Dendrimers in drug delivery and targeting: drug dendrimer interactions and toxicity issues. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6(3):139-50. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.130965, PMID 25035633.

Estanqueiro M, Amaral MH, Conceicao J, Sousa Lobo JM. Nanotechnological carriers for cancer chemotherapy: the state of the art. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2015;126:631-48. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.12.041, PMID 25591851.

Chittasupho C, Anuchapreeda S, Sarisuta N. CXCR4 targeted dendrimer for anti-cancer drug delivery and breast cancer cell migration inhibition. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2017 Oct;119:310-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2017.07.003, PMID 28694161.

Luong D, Kesharwani P, Deshmukh R, Mohd Amin MC, Gupta U, Greish K. PEGylated PAMAM dendrimers: enhancing efficacy and mitigating toxicity for effective anticancer drug and gene delivery. Acta Biomater. 2016 Oct 1;43:14-29. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.07.015, PMID 27422195.

Xiang J, WU B, Zhou Z, HU S, Piao Y, Zhou Q. Synthesis and evaluation of a paclitaxel binding polymeric micelle for efficient breast cancer therapy. Sci China Life Sci. 2018;61(4):436-47. doi: 10.1007/s11427-017-9274-9, PMID 29572777.

Perinelli DR, Cespi M, Lorusso N, Palmieri GF, Bonacucina G, Blasi P. Surfactant self-assembling and critical micelle concentration: one approach fits all? Langmuir. 2020;36(21):5745-53. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c00420, PMID 32370512.

Ghezzi M, Pescina S, Padula C, Santi P, Del Favero E, Cantu L. Polymeric micelles in drug delivery: an insight of the techniques for their characterization and assessment in biorelevant conditions. J Control Release. 2021 Apr 10;332:312-36. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.02.031, PMID 33652113.

Gkionis L, Aojula H, Harris LK, Tirella A. Microfluidic assisted fabrication of phosphatidylcholine based liposomes for controlled drug delivery of chemotherapeutics. Int J Pharm. 2021 Apr;604:120711. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120711, PMID 34015381.

Hormozi N, Esmaeili A. Microfluidic assisted fabrication of phosphatidylcholine based liposomes for controlled drug delivery of chemotherapeutics. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2019 Jun;182:110368. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110368.

Abdelbary AA, Aboughaly MH. Design and optimization of topical methotrexate loaded niosomes for enhanced management of psoriasis: application of box behnken design in vitro evaluation and in vivo skin deposition study. Int J Pharm. 2015;485(1-2):235-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.03.020, PMID 25773359.

Qumbar M, Ameeduzzafar ISS, Imam SS, Ali J, Ahmad J. Formulation and optimization of lacidipine loaded niosomal gel for transdermal delivery: in vitro characterization and in vivo activity. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;93:255-66. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.06.043, PMID 28738502.

Zhang W, Yang Y, LV T, Fan Z, XU Y, Yin J. Sucrose esters improve the colloidal stability of nanoethosomal suspensions of epigallocatechin gallate for enhancing the effectiveness against UVB-induced skin damage. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2017;105(8):2416-25. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33785, PMID 27618624.

Maleki B, Reiser O, Esmaeilnezhad E, Choi HJ. SO3H-dendrimer functionalized magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4@D NH (CH2)4SO3H): synthesis characterization and its application as a novel and heterogeneous catalyst for the one-pot synthesis of polyfunctionalized pyrans and polyhydroquinolines. Polyhedron. 2019;162:129-41. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2019.01.055.

Barve A, Jain A, Liu H, Zhao Z, Cheng K. Enzyme responsive polymeric micelles of cabazitaxel for prostate cancer targeted therapy. Acta Biomater. 2020;113:501-11. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.06.019, PMID 32562805.

Golestani P. Lipid-based nanoparticles as a promising treatment for the skin cancer. Heliyon Heliyon. 2024;10(9):e29898. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29898, PMID 38698969.

Islam K. Potential of nanoparticles as a topical drug delivery system for skin cancer: a review; 2022.

Derakhshankhah H, Jahanban Esfahlan R, Vandghanooni S, Akbari Nakhjavani S, Massoumi B, Haghshenas B. A bio-inspired gelatine-based pH and thermal-sensitive magnetic hydrogel for in vitro chemo/hyperthermia treatment of breast cancer cells. J Appl Polym Sci. 2021;138(24):1-13. doi: 10.1002/app.50578.

Gulati GK, Chen T, Hinds BJ. Programmable carbon nanotube membrane-based transdermal nicotine delivery with microdialysis validation assay. Nanomedicine. 2017;13(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2016.06.017, PMID 27438911.

Hortobagyi GN. Treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(14):974-84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810013391407.

Rawal S, Patel M. Bio-nanocarriers for lung cancer management: befriending the barriers. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021;13(1):142. doi: 10.1007/s40820-021-00630-6, PMID 34138386.

Abdelrady H, Hathout RM, Osman R, Saleem I, Mortada ND. Exploiting gelatin nanocarriers in the pulmonary delivery of methotrexate for lung cancer therapy. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2019;133:115-26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.03.016, PMID 30905615.

Yang C, Merlin D. Lipid-based drug delivery nanoplatforms for colorectal cancer therapy. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2020;10(7):1424. doi: 10.3390/nano10071424, PMID 32708193.