Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 3, 71-74Original Article

PREVALENCE OF METHICILLIN-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS FROM CLINICAL SAMPLES IN A TERTIARY CARE HOSPITAL

FATIMA AMATULLAH1, AFREEN IQBAL2*, JYOTHI B.3

1Department of Microbiology, Mahavir Institute of medical sciences, Vikarabad, Telangana, India. 2*Department of Microbiology, Dr Patnam Mahender Reddy Institute of Medical Sciences, Chevella, Telangana, India. 3Department of Microbiology, Dr Patnam Mahender Reddy Institute of Medical Sciences, Chevella, Telangana, India

*Corresponding author: Afreen Iqbal; *Email: jyothipgis@gmail.com

Received: 25 Jan 2025, Revised and Accepted: 16 Mar 2025

ABSTRACT

Objectives: The present research is mainly focussed on the prevalence of S. aureus MRSA strains isolated from various clinical samples in a tertiary care teaching hospital.

Methods: This is a prospective study conducted in the department of Microbiology, tertiary care teaching hospital, Telangana during the period from Jan 2024 to Feb 2025. S. aureus isolates isolated from various clinical specimens like pus, wound swab, aspirates, blood, urine, and other body fluids were tested for the presence of Staphylococcus aureus. All the collected patient samples were processed aseptically using a standard microbiology protocol of culture and sensitivity. The isolates will then be subjected to susceptibility testing by Kirby-Bauer’s disc diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar plates as per CLSI guidelines.

Results: Among 529 culture-positive cases, 23 strains (4.3%) were MRSA and 49 strains (9.2%) were MSSA. Among the prevalence of S. aureus studied in different age groups, maximum number of cases (29.47%) were reported in the age group of>60 y of age. MRSA and MSSA incidence of 60.8% and 57.14% was seen more in males than females. All the 23 strains of MRSA were resistant to cefoxitin. Most of the MRSA were sensitive to gentamycin, amikacin, meropenem, vancomycin, linezolid, clindamycin. All the 23 strains were sensitive to linezolid and vancomycin. The sensitivity to Vancomycin was confirmed by Van E strip method.

Conclusion: The findings of the current study showed the lowest prevalence of MRSA in the study population 4.3%.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, Prevalence

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i3.55071 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus, a very common pathogen in clinical practice, causes a broad spectrum of diseases ranging from minor skin infections, osteomyelitis, food poisoning to pneumonia, toxic shock syndrome, wound infections, and bacteremia [1]. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are strains of Staphylococcus aureus that are resistant to methicillin and a large group of Beta-lactam antibiotics which include penicillin and the cephalosporins [2]. In tertiary care hospitals, MRSA is typically more prevalent in patients who are immunocompromised, have long hospital stays, or have undergone invasive procedures. MRSA prevalence rates can range from 10% to 40% of all Staphylococcus aureus isolates in hospitals, though some centers report even higher rates. In certain areas, the percentage of MRSA can be closer to 30-50% of all S. aureus infections. Hospital-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA) is often more common in a hospital environment compared to community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA), which may be seen more frequently in outpatient or community settings [3]. Surveillance data for MRSA is critical in tracking its spread, and many hospitals have rigorous screening protocols to detect MRSA colonization in high-risk patients. MSSA, which is susceptible to methicillin and related antibiotics, remains a more common pathogen overall, accounting for 40-60% of all S. aureus infections in many settings. Compared with MSSA (Methicillin Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus) strains, infections caused by MRSA strains are associated with higher morbidity, mortality, and health care burden [6-10]. The prevalence of MSSA tends to be inversely related to the prevalence of MRSA in a hospital. As MRSA rates increase, MSSA rates may decline, as MRSA often replaces MSSA in healthcare settings, especially in patients with high-risk profiles. MRSA exhibits a range of genetic resistance mechanisms that enable it to evade treatment with beta-lactam antibiotics and other drugs. The primary mechanism is the acquisition of the mecA gene, which alters the penicillin-binding protein, but MRSA also employs efflux pumps, beta-lactamase production, biofilm formation, and horizontal gene transfer to enhance its survival [1, 2]. These adaptations make MRSA a challenging pathogen, requiring advanced infection control measures and targeted antibiotic therapies. MRSA needs to be treated with drugs that are carefully chosen. Among the often-used antibiotics include daptomycin, linezolid, and vancomycin. As the MRSA strains still developing resistance to these antibiotics, this has led to renewed interest in the usage of Macrolide-Lincosamide-Streptogramin B (MLSB) antibiotics to treat S. aureus infections, with clindamycin being the preferred agent due to its excellent pharmacokinetic properties [4, 5]. Resistance to macrolides in staphylococci may be due to target-site modification, active efflux (encoded by msrA) of the antibiotic, and by drug inactivation. This is the most widespread mechanism of resistance to macrolides and lincosamides, and leads to cross-resistance between macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramin B, giving way to the well-known MLSB phenotype.

The location, the MRSA strain's susceptibility, and the extent of the infection all influence the treatment option. To make sure the best antibiotic is selected, susceptibility testing is essential. In certain situations, a combination therapy may be required. Since MRSA infections can be quite dangerous, effective management requires prompt and suitable antibiotic treatment. The present research is mainly focussed on the prevalence of S. aureus strains isolated from various clinical samples in a tertiary care teaching hospital.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

This is a prospective study conducted in the department of Microbiology, tertiary care teaching hospital, Telangana during the period from Jan 2024 to Feb 2025. S. aureus isolates isolated from various clinical specimens like pus, wound swab, aspirates, blood, urine, and other body fluids were tested for the presence of Staphylococcus aureus. All the collected patient samples were processed aseptically using a standard microbiology protocol. The samples were streaked on blood agar plates and MacConkey agar plates. Staphylococcus aureus produces large. Circular, convex, smooth, shiny, opaque, beta-hemolytic, golden-yellow pigmented colonies. They produce small pink colour colonies. S. aureus growth was confirmed by catalase and coagulase test. The isolates will be then subjected to susceptibility testing by Kirby Bauer’s disc diffusion method on Mueller Hinton agar plates as per CLSI guidelines. Various antibiotics tested were penicillin (10 units), amikacin (30μg), cefoxitin (30μg), co-trimoxazole (1.25/23.75μg), ciprofloxacin (5μg), gentamicin (10μg), erythromycin (15μg), clindamycin (2μg), linezolid (30μg), tetracycline (30μg), and meropenem (30μg) are used (Hi-Media, Mumbai, India). Vancomycin susceptibility was tested using E-strips (Hi-Media, Mumbai, India). The zone diameters and MIC values will be interpreted as per CLSI guidelines [6, 7]. The detection of methicillin resistance in the S. aureus was identified through a phenotypic test by using a surrogate marker cefoxitin (30μg). The zone size greater than 21 mm is considered as methicillin sensitive and less than 21 mm is considered as methicillin resistance.

RESULTS

About 1800 clinical specimens were examined for the presence of growth of Staphylococcus aureus, among which 29.3% (529/1800) samples had bacterial growth. Among 529 culture-positive bacterial isolates, 17.9% (95/529) were S. aureus isolates and among them coagulase negative staphylococci 41.3% (23/95), respectively. The coagulase positive S. aureus were 75.7%(72/95) strains. Among the 72 strains of coagulase-positive S. aureus, 23 strains were MRSA (31.9%; 23/72) and 49 strains were MSSA (68.1%; 49/72).

Among 529 culture-positive cases, 23 strains (4.3%) were MRSA and 49 strains (9.2%) were MSSA. Among the prevalence of S. aureus studied in different age groups, maximum number of cases (29.47%) were reported in the age group of>60 y of age followed by 51-60 y 23 (24.21%). Most of the Coagulase negative Staphylococci were reported in the age group of 21-30 y 05 (21.7%) and 51-60 y05 (21.7%). Out of 23 MRSA strains isolated, the maximum number of cases 12(51.17%) were reported in the age group of>60 followed by similar prevalence was seen in the age group of 41-50 y and 51-60 y age group 05 (21.7%). Among the 49 MSSA cases, highest incidence 13(26.5%) were isolated in the age group of 51-60 y.

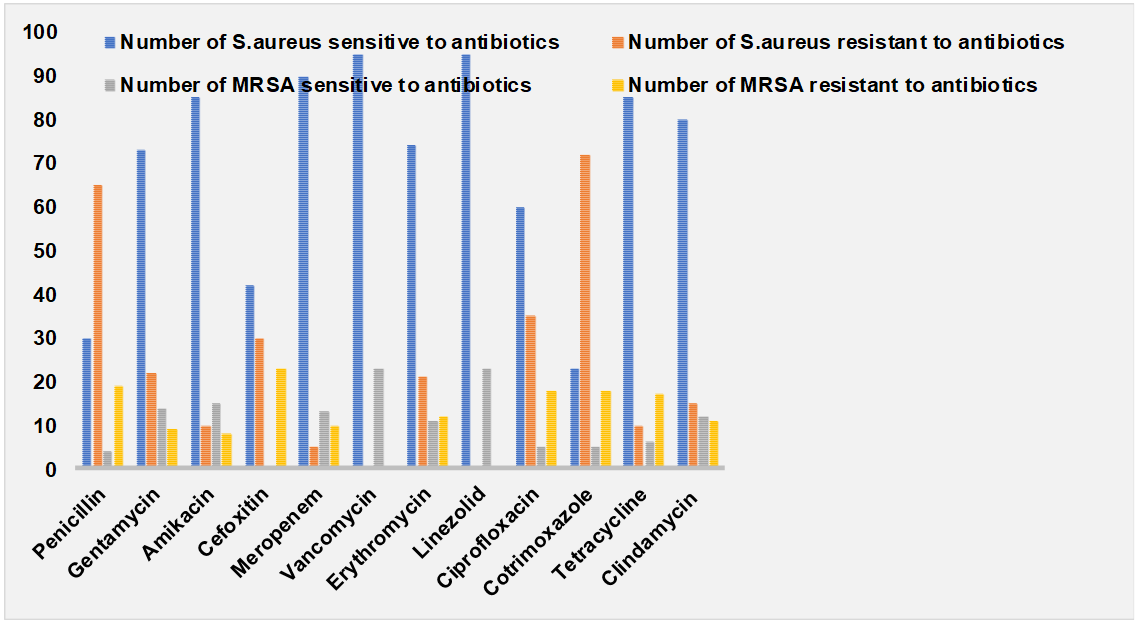

Table 1 showed the prevalence of MRSA and MSSA findings of the current research. The incidence of S. aureus infection was more in males 56.84% than in females. Most of the CONS were isolated 56.5%, from samples collected from female patients. MRSA and MSSA incidence of 60.8% and 57.14% was seen more in males than females. Majority of the patients were in-patients 53.6% and most of the samples were positive for CONS in in-patients than OP patients. MRSA and MSSA strains were mainly isolated from in-patient samples 95.65% and 51.02%. Most of the S. aureus strains were isolated from pus 31.57% followed by urine samples 28.4% and wound swabs 24.21% among the 95 positive cultures of S. aureus. Majority of the S. aureus strains were sensitive to antibiotics like Gentamycin, amikacin, meropenem, vancomycin, erythromycin, linezolid, tetracycline and clindamycin (table 2) (fig. 1). All the 23 strains of MRSA were resistant to cefoxitin. Most of the MRSA were sensitive to gentamycin, amikacin, meropenem, vancomycin, linezolid, clindamycin. All the 23 strains were sensitive to linezolid and vancomycin. The sensitivity to Vancomycin was confirmed by Van E strip method.

Table 1: Distribution of S. aureus, MRSA, MSSA among the demographic variables, and type of samples

| Characters | Staphylococcus aureus | CONS | MRSA | MSSA |

| Age (y) | ||||

| 1-10 | 01 (1.05%) | 01(4.34%) | - | - |

| 11-20 | 03(3.15%) | 01 (4.34%) | - | 02(4.08%) |

| 21-30 | 10(10.52%) | 05 (21.7%) | - | 05(10.2%) |

| 31-40 | 12 (12.6%) | 03(13.04%) | 01(4.34%) | 08(16.3%) |

| 41-50 | 18 (18.9%) | 04(17.3%) | 05(21.7%) | 09(18.3%) |

| 51-60 | 23 (24.21%) | 05 (21.7%) | 05(21.7%) | 13(26.5%) |

| >60 | 28 (29.47%) | 04 (17.3%) | 12(51.17%) | 12(24.4%) |

| Total | 95 | 23 | 23 | 49 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 54 (56.84%) | 10 (43.4%) | 14 (60.8%) | 28(57.14%) |

| Female | 41(43.15%) | 13(56.5%) | 09(39.13%) | 21(42.8%) |

| Type of patient | ||||

| In-patient | 51(53.6%) | 04(17.3%) | 22(95.65%) | 25(51.02%) |

| Out-patient | 44(46.3%) | 19 (82.6%) | 01(4.34%) | 24(48.9%) |

| Clinical specimens | ||||

| Urine | 27 (28.4%) | 07(30.4%) | 0521.7%) | 15(30.6%) |

| Blood | 12(12.6%) | 04(17.3%) | 02(8.69%) | 06(12.24%) |

| Pus | 30 (31.57%) | 06(26.08%) | 08(34.7%) | 16(32.6%) |

| Wound swab | 23(24.21%) | 05(21.7%) | 07(30.4%) | 11(22.4%) |

| Body fluids | 03(3.15%) | 01 (4.34%) | 01 (4.34%) | 01 (4.34%) |

| Total | 95 | 23 | 23 | 49 |

Table 2: Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of S. aureus and MRSA

| Antibiotics | Number of S. aureus sensitive to antibiotics | Number of S. aureus resistant to antibiotics | Number of MRSA sensitive to antibiotics | Number of MRSA resistant to antibiotics |

| Penicillin | 30 | 65 | 4 | 19 |

| Gentamycin | 73 | 22 | 14 | 09 |

| Amikacin | 85 | 10 | 15 | 08 |

| Cefoxitin | 42 | 30 | 0 | 23 |

| Meropenem | 90 | 5 | 13 | 10 |

| Vancomycin | 95 | 0 | 23 | 0 |

| Erythromycin | 74 | 21 | 11 | 12 |

| Linezolid | 95 | 0 | 23 | 0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 60 | 35 | 5 | 18 |

| Cotrimoxazole | 23 | 72 | 5 | 18 |

| Tetracycline | 85 | 10 | 6 | 17 |

| Clindamycin | 80 | 15 | 12 | 11 |

Fig. 1: Antibiotic susceptibility pattern

DISCUSSION

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a significant concern in both community-acquired (CA-MRSA) and hospital-acquired (HA-MRSA) infections. The prevalence varies based on geographic region, healthcare settings, and public health interventions. HA-MRSA infections occur in healthcare settings, such as hospitals and nursing homes, where patients are often vulnerable due to compromised immune systems, invasive devices, and prolonged stays. In hospital settings, MRSA is one of the leading causes of bloodstream infections, surgical site infections, and pneumonia [8]. The prevalence of CA-MRSA has been rising over the past few decades, especially in certain populations, such as athletes, military recruits, children, and people who engage in high-risk behaviours. CA-MRSA strains often differ from HA-MRSA in their genetic characteristics, such as the presence of the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin, which makes them more virulent. These infections are commonly seen in outpatient settings and tend to present as skin and soft tissue infections (e. g., abscesses). Hospital-acquired MRSA accounts for a significant proportion of S. aureus infections in Indian healthcare settings, with estimates ranging from 30-50% of all S. aureus infections, particularly in high-risk areas like intensive care units (ICUs) and neonatal units [9-11]. Community-acquired MRSA has also been on the rise, representing about 10-20% of S. aureus infections in the community, with skin and soft tissue infections being the most common manifestation. In certain regions, this percentage may be higher, reflecting the growing burden of MRSA outside of healthcare settings. In the present study, among 529 culture-positive cases, 23 strains (4.3%) were MRSA and 49 strains (9.2%) were MSSA. The prevalence of MRSA in our study isvery less comparatively than the results obtained in the Gopalakrishnan et al. 2010 who reported the overall prevalence of MRSA was 40-50% [12]. The prevalence of MRSA varies between regions and between hospitals in the same region as seen in a study from Delhi [19], where the MRSA prevalence in nosocomial SSTI varied from 7.5 to 41.3 per cent between three tertiary care teaching hospitals. Verghese et al. reported the overall MRSA rate was 35% in their study [13]. The results of the present study were in accordance to the findings of Shahi, et al. in 2018 who showed the lowest prevalence of MRSA and other studies done globally also showed similar results [14, 15]. In our study, 31.57% isolates were from pus and wound swab samples, indicating their key role in pyogenic soft tissue. The higher frequency of S. aureus isolation in pus samples compared to other samples has been reported in other studies in Nepal and other parts of the world [16, 17]. Preventing MRSA infections requires a multifaceted approach that emphasizes good hygiene, proper wound care, and effective infection control, particularly in healthcare settings. Key practices include regular handwashing, covering wounds, avoiding the sharing of personal items, and proper sanitation of commonly touched surfaces. Additionally, education and early detection are essential in reducing the spread of MRSA. By following these preventive measures, communities can significantly reduce the incidence of MRSA and help limit the development of antibiotic resistance.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the current study showed lowest prevalence of MRSA in the study population 4.3% might be of low sample size. Regular surveillance of hospital-associated infection, practices include regular handwashing, covering wounds, avoiding the sharing of personal items, and proper sanitation of commonly touched surfaces and monitoring of antibiotic sensitivity pattern is required to reduce MRSA prevalence.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed equally

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCE

Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG JR. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015 Jul;28(3):603-61. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14, PMID 26016486, PMCID PMC4451395.

Grundmann H, Aires-de-Sousa M, Boyce J, Tiemersma E. Emergence and resurgence of meticillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus as a public health threat. Lancet. 2006 Sep 2;368(9538):874-85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68853-3, PMID 16950365.

Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber MJ, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(1):53-9. doi: 10.1086/345476, PMID 12491202.

Ahmed MO, Alghazali MH, Abuzweda AR, Amri SG. Detection of inducible clindamycin resistance (MLSB(i)) among methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from Libya. Libyan J Med. 2010 Jan 13;5. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v5i0.4636, PMID 21483594.

Timsina R, Shrestha U, Singh A, Timalsina B. Inducible clindamycin resistance and Erm genes in staphylococcus aureus in school children in Kathmandu, Nepal. Future Sci OA. 2020;7(1):FSO361. doi: 10.2144/fsoa-2020-0092, PMID 33437500.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Twenty-Second Informational Supplement; CLSI Document M100-S22. Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2013.

Fiebelkorn KR, Crawford SA, MC Elmeel ML, Jorgensen JH. Practical disk diffusion method for detection of inducible clindamycin resistance in staphylococcus aureus and coagulase negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(10):4740-4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4740-4744.2003, PMID 14532213.

Ghosh S, Banerjee M. Methicillin resistance and inducible clindamycin resistance in staphylococcus aureus. Indian J Med Res. 2016 Mar;143(3):362-4. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.182628, PMID 27241651, PMCID PMC4892084.

Samia NI, Robicsek A, Heesterbeek H, Peterson LR. Methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus nosocomial infection has a distinct epidemiological position and acts as a marker for overall hospital acquired infection trends. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17007. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-21300-6, PMID 36220870.

Brown NM, Goodman Al, Horner C, Jenkins A, Brown EM. Treatment of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): updated guidelines from the UK. JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance. 2012;3(1):1-6.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Thirty-fourth Informational Supplement; Wayne, PA: CLSI. Document M100-S22; 2024.

Gopalakrishnan R, Sureshkumar D. Changing trends in antimicrobial susceptibility and hospital-acquired infections over an 8 y period in a Tertiary Care Hospital in relation to introduction of an infection control programme. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58 Suppl:25-31. PMID 21563610.

Gadepalli R, Dhawan B, Kapil A, Sreenivas V, Jais M, Gaind R. Clinical and molecular characteristics of nosocomial meticillin resistant staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue isolates from three Indian Hospitals. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73(3):253-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.07.021, PMID 19782432.

Varghese GK, Mukhopadhya C, Bairy I, Vandana KE, Varma M. Bacterial organisms and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58 Suppl:23-4. PMID 21563609.

Shahi K, Rijal KR, Adhikari N, Shrestha UT, Banjara MR, Sharma VK. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus: prevalence and antibiogram in various clinical specimens at Alka Hospital. TU J Microbiol. 2018;5:77-82. doi: 10.3126/tujm.v5i0.22316.

Hiramatsu K, Hanaki H, Ino T, Yabuta K, Oguri T, Tenover FC. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40(1):135-6. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.135, PMID 9249217.

Shrestha LB, Syangtan G, Basnet A, Acharya KP, Chand AB, Pokhrel K. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in Nepal. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2021 May 25;59(237):518-22. doi: 10.31729/jnma.6251, PMID 34508427, PMCID PMC8673459.