Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 5, 22-30Review Article

THE POTENTIAL OF 3D PRINTING IN DRUG DELIVERY AND TISSUE ENGINEERING

ANIKET S. INGLE*, KRANTI S. PATIL, PURVA M. PAPRIKAR

Shastry Institute of Pharmacy, Dbatu, Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India

*Corresponding author: Aniket S. Ingle; *Email: aniketingale734@gmail.com

Received: 08 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 30 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

The pyramid of additive manufacturing, the jewel of 3-dimensional (3D) printing emerges. Over the past ten years, it has been anticipated that three-dimensional bioprinting technology will revolutionize the pharmaceutical sector. It is rapidly developing and has applications in many fields, including as the aircraft, defence, automotive, architectural, film, music, forensic, dental, audiology, prosthetics, surgery, cuisine, and fashion industries. This amazing manufacturing technique has grown in importance for pharmaceutical applications in recent years. Computer software will create a computer-aided drug (CAD) model, which will then be fed into bioprinters. The printers will identify and create the model scaffold based on material inputs. The printing process is accelerated by methods such as stereolithography, binder deposition, inkjet-based, fused deposition modelling, material extrusion, material jetting, selective laser sintering, selective laser melting, and bioprinting. Rapid prototyping, flexible design, print-on-demand, lightweight and robust components, quick and economical, and environmentally friendly are some of the unique benefits. The conceptualization of 3D printing is briefly described in this review, followed by the many techniques used. A brief explanation of the fabrication materials used in the pharmaceutical industry was given. The laser beam is directed toward the different pharmaceutical and medical uses.

Keywords: 3 Dimensional printing, Technics of 3D printing, Fabricating material, Tissue engineering, Drug delivery

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i5.7038 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

One such incredible technology that is thriving in almost every area of healthcare is 3D printing [1]. In contrast to subtractive manufacturing techniques, three-dimensional (3D) printing, sometimes referred to as additive manufacturing (AM) and fast prototyping, is the process of connecting materials to create items from 3D model data, typically layer-by-layer [2] 3D printing is an additive process that creates 3D shapes by combining successive layers of material [3]. AM is a group of emerging technologies that create things from the ground up, layer by layer across the cross-section. This procedure initiates the process of building a 3D model of the intended item using computer-aided software, commonly referred to as CAD [4].

Essentially, one amazing one advantage of 3D printing is its capacity to produce intricate structures that are not economically viable to produce via injection moulding techniques [5]. A rising number of biomedical engineering researchers have begun using 3D printing as a game-changing tool for biomedical applications, particularly for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, thanks to recent advancements in the technology [6]. Patients who utilize medications with limited therapeutic indices or who are known to have a pharmacokinetic variant may benefit most from personalized 3D-printed medications [7].

Fused deposition (FDM), selective laser sintering (SLS), and stereolithography modeling (SLA) are 3D printers that can print plastic materials. Two rollers extrude a molten thermoplastic polymer filament through a high-temperature nozzle in FDM, where it solidifies onto a build plate [8]. Although the human body has an amazing capability for regeneration, this ability is constrained by various criteria, including the kind of tissue and the requirement for growth hormones for physical expansion and differentiation (a crucial deficiency). Any damage to a tissue larger than this requires outside assistance. Regenerative medicine (RM) or tissue engineering (TE) are common terms used to describe this method of promoting tissue regeneration. Scaffolds are the external supports [9]. Biocompatibility and mass transport were given much of the attention in the early days of tissue engineering because it was thought that biomaterials only served as scaffolding for cells. Nonetheless, it is now understood that the extracellular matrix of the in vivo cellular milieu contains vital information-rich cues [10]. Although the basic properties of biodegradability, biocompatibility, and rapid prototyping have formed the foundation for the development of 3D printed tissue engineering constructions, tissue integration requires further focus [11].

When compared to traditional techniques, current three-dimensional (3D) printing technologie may more advantaIt was thought that the cells would proliferate more quickly as a result of the isotropic compressive pressure. It was thought that the cells would proliferate more quickly since the outcome of the isotropic compressive load. When compared to traditional techniques, modern three-dimensional (3D) printing technologies can be more advantageous in creating structures with higher resolutions [12]. BJ-3DP, FDM, SSE, MED in material extrusion, and SLA are the primary 3D printing methods utilized in the pharmaceutical industry [13]. Additionally, Mathew et al. created the empty MN array for transdermal medication administration application using the digital light processing (DLP) 3D printing technique [14].

Three-dimensional printing (3DP) is thought to be the most revolutionary and potent of the several innovations introduced into the pharmaceutical and biomedical markets. This method is acknowledged as a flexible instrument for accurately producing a range of gadgets. It is a technology used in disease modelling, tissue and organ engineering, and the advancement of novel dosage forms [15]. The use of 3DP techniques in the pharmaceutical industry manufacturing of drug products has gained a lot of attention recently due to its many inherent advantages over conventional technologies, such as the ability to produce complicated solid dosage forms with high accuracy and precision, on-demand manufacturing, cost effectiveness, and the tailoring and customization of medications with individually adjusted doses [16].

Trump cards highlight the main advantages of 3D printing, which include quicker, more flexible, more affordable, and customized production; improved quality control; time and energy savings; improved management from raw material collection to the finished product; quick prototyping; reduced waste; and environmental friendliness, which attracted attention in the pharmaceutical industry [1]. An essential component of bone tissue engineering is scaffolding. Three-dimensional (3D) biocompatible structures called scaffolds can replicate the characteristics of extracellular matrix (ECM), including mechanical support, cellular activity, and protein synthesis, through biochemical and mechanical interactions. They can also function as an example for attachment and promote the formation of bone tissue in vivo [2]. An object's 3D model is the the initial stage of the 3D printing procedure.

It is then digitalized and divided into model layers using specialized software. Then, by superimposing each new layer atop the previous one, the Three-dimensional printing technology 2D layers into a 3D build. The finished product is created by combining these layers [3].

Techniques behind 3D printing

Most people agree that Hideo Kodama from the Municipal Industrial Research Institute of Nagoya produced the first tangible item from a computer design. Nonetheless, Charles Hull, Who invented the first 3D printer? in 1984 while employed by the business he formed, 3D Systems Corp., is usually given credit for it. The solid imaging method known as stereolithography and the STL (stereolithographic) file format, which is still the most used format in 3D printing today, were both invented by Charles A. Hull. Alongside his development of 3D printing, he is also recognized for having initiated commercial fast prototyping. He first produced the melting and solidification action by heating photopolymers with UV light [17].

Additive manufacturing (AM) is the fundamental idea behind 3D printing. In contrast to traditional machine technology, additive manufacturing (AM) involves stacking connected materials in layers to create a 3D model. It is a revolutionary technology that might mark the beginning of a new age of production and the development of new business models for companies [1].

Every business, including industry and medical, is affected by the evolving technology. This emerging technology now includes 3D printers. Even though we consider this technology to be extremely recent, what is new is that it is now more widely available and reasonably priced than it was previously. It is believed that 3D printing would advance daily because of the various facilities that serve a wide range of industries [18]. Materials such as metal, ceramic, composite, and polymers can all be printed using 3D technology. Stainless steel is the metal that is most frequently utilized [18].

Different materials and applications can benefit from 3D printing, which includes techniques like selective laser sintered (SLS), material jetting, stereo lithography (SLA), material extrusion and binder jetting, among others. Its capacity to generate elaborate parts successfully and save time and materials through high-speed production make it intriguing in a variety of fields [18]. The medical field is one of the many uses for this well-known technology geometric 3D modeling of the anatomical target area based on medical images, file modification to create the model print-ready, and selection of the material and printing technique are the steps involved in creating a printed medical model [19]. Future-oriented technology is a well-established academic and administrative field that is comprised of the collection of methods and information sources used for this aim, among others [20].

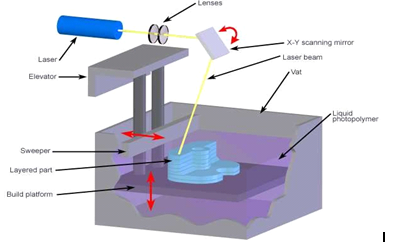

Stereo lithography (SLA)

This procedure involves liquid photopolymer curing in a vat using a UV laser. The construction the platform is dropped into the vat to construct the part. Large items may be produced using stereolithography with excellent surface polish and accuracy. Parts with particular qualities can be constructed using a variety of materials. However, photopolymers, which lack well-defined mechanical qualities and are not consistent throughout time, are the only materials that stereolithography can use [21]. Stereo lithography relates to 3D printing that uses photo polymerization-a process where light joins molecular chains to produce polymers-to construct models, prototypes, and layer-by-layer mode patterns. These polymers then combine to create a solid, three-dimensional object. The area was studied in the 1970s, but Charles (Chuck) W. Hull gave it its name in 1986 after copyrighting the findings. To promote his patent, 3D Systems Inc. was founded [22]. The conduct of the SLA front is really intriguing. This is a well-defined technological front whose interpretation did not create any questions when it was present for a while. However, it is momentarily halted from 2006 to 2012 and eventually vanishes from our model starting in 2015 [3]. With the benefits of great mechanical strength and accuracy, stereolithography is frequently used to create surgical guides for dental implant implantation; yet, it has the drawback of being expensive and requiring specialized equipment [20]. The printed solid and cellular materials' Young's modulus, strength, and resistance to impact were significantly enhanced. Including self-healing properties in resin that is SLA-printed is another method to reduce brittle fracture. Buckingham et al. increased the lifespan of SLA 3D-printed specimens and material sustainability by combining a commercially available photo-curable resin with a self-healing catalyst microcapsule system [23]. A Form labs Form 2 SLA 3D printer (Form labs Inc., Somerville, MA, USA) with a 405 nm wavelength light source was used for all stereo lithographic printing. The resolution of the SLA printer enables the fabrication of objects with layer thicknesses of 25, 50, or 100 µm [24]. Importantly, when employing the SLA 3D printing method for drug distribution, it is important to prevent unwanted interactions between the photo-reactive monomer and the API. If this is not done, the active drug molecule may degrade or iterate, which could reduce the therapeutic effects. Prior research using SLA 3D printing of oral dosage forms showed that the printed tablets contained at least 90% of the medicine, indicating that there were no drug-photopolymer interactions [25].

Fig. 1: Stereolithography

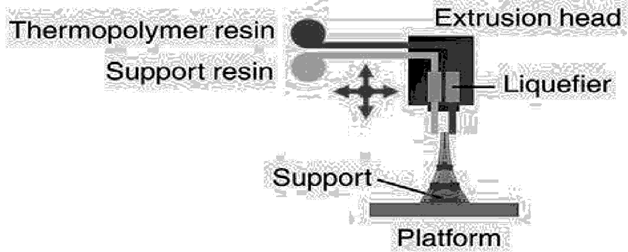

Fused deposition modelling (FDM)

The FDM technique uses thermoplastic polymers such acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, Poly lactic acid (PLA), and PVA. Certain commonly used polymers can be easily fed into FDM printing systems by being coiled and sold commercially as pre-processed filaments. Another name for this procedure is fused filament modelling [26]. Using HME, the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are combined with thermoplastic polymers to create long, cylindrical, rod-shaped filaments, which serve as the starting material for FDM. To create the required 3D shapes, these filaments are fed into the heating nozzle, melted, and then deposited layer by layer using FDM. In-house production of customized dosage forms for immediate consumption is highly promising when FDM and HME are combined into a single unit operation. Therefore, in the context of pharmaceutical manufacture, the combination is regarded as a revolutionary change [27]. One benefit of FDM over powder-bed printing is its higher resolution, which enables it to achieve better dosing precision and create more intricate scaffolds [28].

Fig. 2: Fused deposition modelling

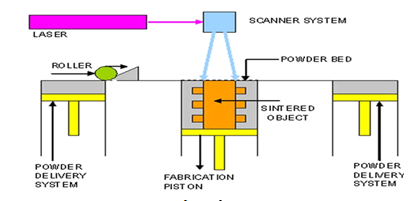

Selective laser sintering (SLS)

Among these is Using a laser beam to fuse powder particles together at their surfaces, selective laser sintering (SLS), a subset of powder bed fusion 3D printing, produces solid objects (Fina et al., 2018a). Carl Deckard created SLS technology in 1984, based on a 100 W neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd: YAG) laser (Beamon and Deckard, 1990) [29]. Since the use of SLS would enable the construction of previously challenging-to-manufacture structures from pharmaceutical grade excipients, we set out to create structures known as 3D gyroid lattice constructs, which are porous solids that can be manufactured with a broad range of micro-structures and length scales. Up until now, 3D printed oral solid dosage forms made using other technologies have demonstrated a multitude of designs and forms [30]. Like the majority of SFF techniques, One additive is selective laser sintering. Fabrication method that rapidly creates models and prototype components from data from CT and MRI scans, 3D CAD models, and 3D digitizing data obtained from a system. Layer by layer, the physical thing is created, turning the three-dimensional issue into a two-dimensional one. CAD data files exported in the industry-standard exchange file format standard training language (STL) are used to build objects layer by layer. A straightforward collection of triangular facets makes up the STL format, a boundary representation (3D System Inc., 1988) [31].

Selective laser melting (SLM)

The most often used word for laser sintering of metals is SLM, or selective laser melting, while some manufacturers also use the terms Laser Cussing and DMLS, or direct metal laser sintering [32]. Selective laser melting enables the layer-by-layer production of metal components in accordance with a 3D-CAD Thus, SLM makes it possible to produce practically infinite complicated geometries without the requirement for expensive preproduction or part-specific tooling. Examined the SLM process's defect forms and came to the conclusion that the process's energy density parameters may regulate the faults. Furthermore, one important factor in reducing location distribution faults is scan method. The majority of the flaws are located between two adjacent tracks and at the scan track termination. Thirdly, the magnitude of the molten pool, temperature gradients, and stresses produced by the process parameters used during the deposition of a single layer of the material may all be predicted and controlled using finite element software [33]. The temperature distribution within the SLM procedure varies quickly as the energy beam moves quickly, and a large temperature gradient may result from the high energy input at the local zone. This causes high residual stresses and uneven deformations of the finished parts [34]. The building chamber is frequently filled with argon or nitrogen gas throughout the SLM process to create an inert atmosphere that prevents oxidation of the hot metal components. Additionally, certain SLM machines has the capacity to warm the substrate plate beforehand or the construction chamber as a whole. Typically, the layer's thickness falls between 20 and 100 lm. This was selected to strike a balance between permitting adequate powder flowability and attaining fine.

Fig. 3: Selective laser sintering

Material extrusion

After powder bed fusion, material extrusion (ME) is the second most widely used additive manufacturing (AM) technique, which has had 578,000 and 26,820,000 searches, respectively. The terms "ME," "Fused Deposition Modelling," and "Fused Filament Fabrication" were often searched combined. The procedure of selectively pouring material through a nozzle in additive manufacturing (AM) aperture is referred to by these three words [35].

The solid wire used in material extrusion is composed of filled and unfilled thermoplastics, commonly referred to as "filaments." One popular and widely used thermoplastic polymeric material for material extrusion is PLA. It's a polylactic acid-based thermoplastic. Biocompatibility is demonstrated by the polymer, and under ideal conditions, completely biodegradable. The polymer blend determines its glass transition temperature (Tg), which typically ranges from 45 to 65 °C [36] Parts having complex interior forms can be produced using the additive manufacturing technology referred to as FFF (fused filament fabrication). With one or more extruder nozzle heads, an FFF printer functions essentially as a computer numerically controlled (CNC) gantry machine. One nozzle in dual-nozzle systems is for the modelling substance, as well as the additional nozzle may be for support material or another modelling material that is soluble in alkaline solutions or readily breakable [37].

Bioprinting

The practice of simultaneously writing biomaterials and living cells in a predetermined layer-by-layer stacking arrangement utilizing a computer-aided transfer method to create bioengineered structures is known as bioprinting. In order to better direct tissue development and synthesis, it provides extremely precise spatial placement of cells, proteins, DNA, medication particles, growth factors, and physiologically active particles. For the advancement of tissue fabrication toward physiologically realistic tissue constructs, tissue models, tissues and organs, and organs-on-a-chip models for pharmaceutical and medical applications, this potent technology seems to hold greater promise [38]. Autonomous self-assembly, biomimicry, and the building blocks of mini-tissue are some of the methods used in 3D bioprinting. These methods are being developed by researchers to create 3D functional live human constructs that have mechanical and biological characteristics appropriate for the clinical recovery of organ and tissue function. Adapting technologies made to print molten metals and polymers to the printing of delicate, living biological materials is a significant task [39]. Bioprinting, based on AM technology, enables direct cell deposition in organotypic architecture. Additionally, it can be used in conjunction using CAD/CAM technology in order to create a structure with a precise anatomical shape [40]. Additionally, while bioprinting typically entails applying bioinks to surfaces that have three-dimensional structures created by stacking printed filaments, an emerging method of considerable interest is applying bioinks to suspension baths, also known as suspension media or support hydrogels, which offer support throughout the printing process [41]. By timing the bioink's deposition and crosslinking with the motorized stage movement, bioprinting enables the creation of three-dimensional tissue structures with pre-programmed geometries and structures made of biomaterials and/or living cells (together referred to as the bioink). The adaptability of bioprinting has continued to speed up tissue engineering applications, even if it is still in its infancy [42].

Fig. 4: 3D bioprinter (A), 3D integrated organ printer (B), Commercialized N Ovogen MMX bioprinter (C)

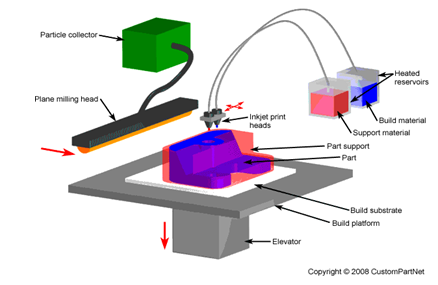

Inkjet printing

Since the 1960s and 1970s, when the technology was initially invented, inkjet printing has been widely adopted. More recently, it has progressed from uses like product tagging and graphic art printing to more sophisticated uses like digital fabrication and additive manufacturing [43]. Over the past 30 to 50 y, two key operating concepts have evolved into standard technologies that are currently controlling the consumer inkjet printing business. These primarily consist of thermal inkjet technology and the piezo-electric ink deposition idea. Several suppliers had already created these systems for the consumer market in the 1960s and 1970s [44] Without the need for tools, inkjet three-dimensional (3D) printing is a quick, adaptable, and affordable technique that makes it possible to create both straightforward and complex 3D things straight from computer-aided design (CAD) data. Inkjet 3D printing is a member of the Solid Freeform Fabrication (SFF) family of manufacturing methods. SFF speeds up the product development cycle and greatly enhances design by enabling the quick manufacturing of prototypes without the requirement for tooling and giving the designer quick, useful input [45]. Because of its accuracy, precision, low cost, simultaneous deposition of several materials, and ease of scale-up/out, inkjet printing has been hailed as a promising additive technology. Material throughput is dependent on the printer's size and number of jets [46].

A liquidized photopolymer is heated to roughly Inkjet 3D printing uses 73 °C, jets it onto a surface, and instantly cures it with UV light. The majority of commercial printers use two or more print heads, one for the model material and one for the support material, just like in traditional printing. One significant benefit of the technique is the ability to add more print heads for increased material throughput or to print multiple materials. Numerous nozzles that are aligned linearly make up each print head. As the build tray descends, thin layers of cured material accumulate until the part is complete [47]. Because of its many technological benefits, inkjet printing is a desirable industrial technique. Inkjet printing is a non-contact process, to start. It is less prone to contamination and damage to the substrate or mask, and it is scalable. Second, inkjet printing is a digital method that uses drop deposition to provide a wide range of patterning options [43].

Fabricating material

To consistently produce like any other manufacturing process, 3D printing demands premium materials that meet exacting criteria in order to produce high-quality goods. Procedures, specifications, and agreements pertaining to material controls are developed amongst the material's suppliers, buyers, and end users to guarantee this. Utilizing diverse materials, including metal, ceramic, polymers, and their blends to produce composites, hybrids, or functionally graded materials (FGMs), 3D printing technology could produce fully functional parts [48]. Natural biopolymers, such as cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, starch, alginate, chitosan, and their derivatives, can be used as 3D printing feedstock’s to meet sustainability requirements while also significantly lowering the likelihood of certain synthetic polymers' adverse effects in biomedical applications, including decreased cell attachment, degradability, recyclability, hazardous breakdown products, and released additives as per mentioned in below table 1 [49].

Metal

Embraer and Fraunhofer IPK are collaborating to examine the mechanical attributes and features of titanium components produced via Selective Laser Melting for use in structural aerospace applications. Analysing the process and the final products is crucial to gaining advanced information about these created items. To achieve this goal, titanium alloy test geometries were constructed, and several characteristics such surface roughness, density, and microhardness Tensile, fatigue, and roughness characteristics were investigated. In order to assess the results obtained, the SLM method ultimately created structural metal pieces [50]. Due to the ternary cobalt chromium-molybdenum (Co-Cr-Mo) and cobalt-chromium-tungsten the high strength and stainless nature of cobalt-chromium-tungsten (Co-Cr-Mo) and Co-Cr-W alloys, which were initially patented by Haynes in 1907, compositional of clinically useful cobalt-based alloys, such as prosthetic knee and hip joints and denture frameworks for fixed and removable prostheses, have been developed. According to reports, the first time a cobalt-based alloy was used for investment casting in dentistry was in 1936. This occurred thirty years after William Taggart developed a workable technique for casting gold inlays [51]. AM metal processing became a cutting-edge processing method as a result of notable developments in its constituent technologies during the previous 20 y, including metal powder feedstock technology, affordable high performance computing hardware and software, and more affordable, dependable industrial lasers. The sharp increase in commercial system sales indicates that it has now attained a key acceptability level. Industry is increasingly demonstrating and embracing AM metal technology, which was created in national laboratories, universities, and industrial research labs. The majority of applications have accomplished this through brute force certification of every single part type, material, and procedure, however some have achieved technological readiness levels of completely certified manufacturing. It would be ideal to have a deeper comprehension of the feedstock materials, procedures, structures, characteristics, and performance [52]. Over the past ten years, direct printing on a range of flexible material surfaces has become more popular due to the availability of Nano-conducting inks made of silver, copper, and related alloys, as well as the capacity to print organic field effect transistor circuits and organic LEDs (OLEDs). These surfaces include direct printing of circuits on paper and flexible, translucent polymer sheets [53], also having various uses of 3D printing (fig. 8).

Fig. 5: Inkjet printing

Polymer

By adding reinforcements like particles, fibers, or nanomaterial’s to thermoplastic polymers, 3D printing of polymer composites with improved mechanical properties gets around the earlier restrictions and makes it possible to create polymer matrix composites, which are known for their high performance and superior functionality [54]. Polymer 3D printing has shown promise in the aerospace and architectural sectors for producing intricate lightweight structures, the art and education sectors for reproducing artefacts, and the medical industry for manufacturing tissues and organs [55]. Materials for polymeric printing, post-processing, reinforcements, and other crucial factors. The mechanical characteristics and assessment methods of 3D-printed polymers will be discussed in this study under the following circumstances: creep, cyclic/fatigue loading, bending, compression, tension, and impact loading. Failure and fracture resilience. The review will include processes and mechanical properties at cryogenic temperatures. The final section of the presentation will address the crucial factors for standardizing Mechanical testing and characterisation of AM components [56].

Smart material

The fourth revolution also makes use of smart materials to improve product performance. Over time or in response to temperature changes, certain materials may undergo form changes. In addition to having many uses in the medical field, a smart product can modify its shape to meet certain needs [57].

Ceramic

Because the individual powders in some materials, including concrete and ceramics, cannot be fused together by raising their melting points, they are not suitable for 3D printing. On the other hand, by raising their melting or glass transition temperatures, metals and polymers can fuse together. One of the biggest obstacles in the world of additive manufacturing is the incredibly high melting point of ceramic materials as compared to metals and polymers. Deckers et al. examined additive manufacturing techniques with ceramic materials. Through the optimization of AM process parameters current AM techniques may create ceramic components with no cracks or large pores, and their mechanical qualities are comparable to those of ceramic parts that are traditionally produced [58]. Because of the thermal stress that cannot be totally removed throughout the process, ceramics still require more post-processing techniques. The most deadly defect is that inadequate surface roughness necessitates grinding and polishing, which will surely reduce production efficiency. Furthermore, while the high-temperature prepared powder can reduce thermal stress and prevent cracks, the process frequently results in low-resolution precision and poor surface quality for the printed body parts [59].

Tissue engineering

3D printing successfully compensates for these shortcomings as a technology that can create scaffolds for bone tissue engineering, and it has rapidly gained popularity in scaffold moulding. In 1989, Emanuel Sachs of MIT published the first paper on 3D printing technology. It is a form of additive manufacturing, another name for fast prototyping technology. Discrete, accumulation molding theory, computer-aided design, numerical control technology, biological materials, etc. are all incorporated within its operating principle. Using the principles of layered manufacturing and layer-by-layer superposition, this revolutionary digital molding method can swiftly and precisely create materials into 1:1 models [60]. The possible tissue-engineered components, such as bone, cartilage, nerves, muscles, bladders, livers, heart valves, and so forth. The majority of tissue engineering techniques, nevertheless, called for the use of a permeable framework, which serves as a 3D layout for initial cell connection and subsequent tissue arrangement for both in vitro and in vivo techniques. Furthermore, the scaffold provides cells with essential support for attachment, proliferation, and maintenance of their distinct potential. This engineering method defines a defined state of the newly formed hard or delicate tissue [61].

When 3D printing technology first emerged in 1990, its primary application was the creation of scaffolds made of synthetic inks. The process did not develop into what is today known as bioprinting until the past ten years. Tissue engineering applications were aided by the creation of bioinks, biocompatible soft materials containing biological elements like cells or naturally occurring matrices. 3D printing is a new technology that is developing quickly and has the potential to be a useful tool for translating biology and illness in dentistry or creating tissue-like constructions for oral surgery [62]. By employing autologous cells, tissue engineering (TE) totally eliminates the potential of immunological reactions such viral infections and hyperacute and delayed rejections. Prior to implantation, seeded cells can organize and develop into the desired organ or tissue on a scaffold, which is part of the fundamental idea of TE. Until the cells generate enough extracellular matrix, the scaffold gives the replacement tissue its initial biomechanical profile [63]. The construction of a matrix that can replicate the inherent characteristics of bone while serving as a temporary scaffold for tissue regeneration is the challenge of bone-tissue engineering. Bioresorbable implants, such microsphere matrices, have the potential to serve as functional substitutes for trabecular bone when combined with growth hormones and a mechanically stable structure. The difficulty is in balancing the production and expansion of bone with the deterioration and loss of mechanical characteristics. The characteristics of natural trabecular bone may eventually be matched by synthetic substitutes if these parameters can be adjusted to offer sufficient biomechanical support during regeneration [64]. A growth-directing structure that allows cells to migrate and multiply to produce a functional tissue would be the perfect 3D printed construct for tissue engineering. Despite the fact that genetics can influence cell destiny, this area of study has proven to be laborious and complicated. Epigenetics has demonstrated that covalent and noncovalent alterations (such as DNA methylation) to the DNA and histone protein arrangement in chromatin serve as a bridge between the inherited genotype and the challenges of employing genetic tools to control cell fate [11].

The potential for tissue engineering to develop biological substitutes that preserve, repair, or enhance tissue function has garnered a lot of interest in the last ten years. Nowadays, tissue engineering is primarily concerned with creating three-dimensional structures that facilitate the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of cells that originated from cell cultures rather than just cell culture [65]. If tissue engineering is developed and advanced to the point where Living organs and tissues can be can be regularly built and reliably integrated into the body to restore, replace, or enhance tissue and organ functions, reparative medicine could benefit greatly. Therefore, the use of tissue engineering in restorative medicine holds out a lot of promise with the purpose of treating numerous illnesses, such as spinal cord injuries, diabetes, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, birth defects, heart disease, liver and kidney failure, and diabetes. Tissue engineering may yield surrogate tissues that are helpful for toxicity testing and drug research in addition to its application in reparative medicine [66]. Human vascular cells in their intact layers cultured to over confluence can be used to create tissue-engineered blood arteries, creating a "cell self-assembly model." After Fibroblasts and human SMC were cultivated with vitamin C present, three-dimensional sheets of these cells, together with the extracellular matrix they were connected with, were rolled over a mandrill to create tubes of "media" coated with "adventitia." Following maturation, endothelial cells were implanted into the inner tube [67].

Table 1: Fabricating material

| S. No. | Fabricating materials | Subclass | Examples | Applications | Reference |

| 1. | Polymers | Thermoplastics | Polycaprolactone (PCA) Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) |

Tissue engineering (Trachea, stem cell model) Drug modelling for cancer therapy | [68] |

| Polylactic acid (PLA) | |||||

| p-hydroxybenzoic acid (PHBA) | |||||

| Thermosets | Urethane Resin | ||||

| 2. | Hydrogels | Biopolymers | Chitosan Fibrin |

Tissue engineering (bone, cartilage) Drug delivery (nanomedicine) |

[69] |

| Collagen | |||||

| Agar | |||||

| Gelatin | |||||

| Alginate | |||||

| 3. | Composites | Matrix | Carbon fiber Silicon carbide | Prostheses, implants | [1] |

| Fillers | Hydroxyapatite | ||||

| Calcium phosphates | |||||

| Ceramics precursors | |||||

| Metal precursors |

Drug delivery

"The manufacture of objects through the deposition of a substance utilizing a print head, nozzle, or other printer technology" is how ISO defines three-dimensional printing. It has been widely used in the production of biomedical devices, disease modelling, Diagnostics and tissue and organ engineering, and the creation of innovative dosage forms [70]. Layers of material, often polymer, are printed one after the other during the 3D printing process. First described as stereolithography by Charles Hull in 1986, 3D printing technology has now advanced to include new methods as powder bed fusion (PBF), fused deposition modelling (FDM), inkjet printing, and contour crafting (CC). With changes in manufacturing and logistics, 3D printing encompasses a variety of techniques, materials, and equipment, the majority of which have been invented in the past few years. There are many benefits to 3DP, including reduced waste, design freedom, and automation [6]. Additive manufacturing (AM), another name for three-dimensional (3D) printing, is a contemporary process and technology that enables the creation of 3D things from computer-aided design (CAD) digital models. The creation of medication delivery mechanisms, where porosity has been crucial in achieving a satisfactory degree of biocompatibility and biodegradability with enhanced therapeutic benefits, can make use of this technique. Additionally, 3D printing makes it possible to enhance the composition of medicine delivery systems and may give the user the ability to regulate the amount of each element for a particular purpose [71] Various technologies, including fused deposition modelling (FDM), also known as fused filament fabrication (FFF), semi-solid extrusion (SSE), stereolithography (SLA), digital light processing (DLP), and selective laser sintering (SLS), have been employed to create mucosal drug delivery systems [72]. The manufacturing of medications and drug delivery systems has been completely transformed by 3D printing in the healthcare industry. Small batches of medications with customized dosage, dimensions, form, and release properties can be produced at the point of care thanks to 3D printing's flexible and accurate spatial control distribution of components [73]. The term "drug delivery" describes methods, structures, tools, and compounds used to move pharmaceuticals through the body as required to securely produce the intended therapeutic effect. Over time, the idea of drug administration has changed significantly, moving from oral dose forms with immediate release to systems with tailored release. It's accurate to say that regulating the medication release profile to alter the drug's absorption, distribution, metabolization, and elimination quickly emerged as a crucial element for enhancing product efficacy and safety as well as patient compliance [74].

Oromucosal drug delivery system

Reliable techniques to assess mucoadhesion and forecast the delivery system's in vivo interaction with the mucosa are required in the pharmaceutical development of oromucosal delivery systems in order to assess the formulations' potential for clinical usage. There are three types of methods for assessing the mucoadhesion of oromucosal drug delivery systems: in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo experiments. The most accurate techniques are in vivo and ex vivo (rat intestinal segment model, for example), but their application is restricted for moral reasons [75]. When inserted in the mouth, mucoadhesive buccal films, or MBFs, adhere to the buccal mucosa. MBFs can be utilized to treat local or systemic illnesses. The pharmaceutical ingredient that is active (API) in systemic therapy is either ingested with saliva or absorbed through the mucosa, avoiding the gastrointestinal tract [76]. While the application of a backing layer promotes unidirectional drug release and prevents medication swallowing, natural or synthetic mucoadhesive polymers are frequently employed to extend the residence time of formulations on the administration site and maximize localized drug delivery [77].

Vaginal drug delivery system

It is possible to treat bacterial vaginal infections locally or orally. The most common medications used for oral therapy are metronidazole and clindamycin. Even though most women receive effective treatment with these antimicrobials, 30% will relapse after 4 w of treatment because the germs were not completely eradicated, the lactobacilli flora was not successfully restored, or resistance developed [78]. A naturally occurring steroid hormone, progesterone is mostly used in hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for menopause and hypogonadism. It also helps the ovum implant and sustains pregnancy. It is possible to deliver progesterone by injection or by mouth. However, because to its water-insoluble nature and hepatic metabolism, progesterone administered orally has a bioavailability of less than 10%, but progesterone administered via injection causes severe local aches and damage [79] Along with the standard "O" shape, progesterone-loaded vaginal rings were also printed in "Y" and "M" shapes. The rings were made from a PLA and PCL blend and manufactured using an FDM 3D printer. Because the "O" ring has a higher surface area/volume ratio than the "Y" and "M" rings, the latter two have a lower drug release pattern. Progesterone was released by the vaginal rings in a pattern of continuous release for over seven days [80].

Ocular drug delivery system

Because topical administration, such as eye drops, is convenient, non-invasive, and reduces systemic adverse effects, it is the recommended method for delivering therapeutic drugs to the anterior portion of the eye. However, due to a variety of circumstances, including as blinking, a high rate of tear turnover, nasal-lacrimal drainage, and a short drug residence time, ocular bioavailability from topically applied formulations is often poor (<5%) [81]. We'll talk about the most prevalent chronic eye conditions. Longer medication treatment intervals are required for these disorders, and the best Ideally, drug delivery systems should increase the drug molecules' dispersion to target the ocular tissues, stability, and activity. This article discusses utilizing the long-acting drug delivery target system (LADDS), especially drug delivery devices that are implanted (IDDS), as well as how to formulate, characterize, evaluate, and apply them in clinical settings [82]. Although they can administer hydrophobic medications, ocular suspensions and emulsions can cause impaired vision. Semi-solid ocular gels and ointments may significantly extend residence time. Solid dose forms could be utilized for zero-order release (insert), water-sensitive drug delivery (powder), or maintaining residence time (therapeutic contact lens) [83].

CONCLUSION

The growth estimations show that the 3D printing sector is headed for expansion. With more and more research being done, 3D printing's uses are growing. As demonstrated by the Amazon proposed concept, 3D printing will transform how consumers purchase goods. With so many opportunities to watch, the field is undoubtedly a game changer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors like to express our sincere you to everyone who helped to make this project a success review article our deepest thanks to our institute ‘Shastry Institute Of Pharmacy Erandol’ and also grateful to our friends and guide ‘Miss Purva paprika’ for their valuable guidance and constant support throughout this review article.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed equally

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Pavan Kalyan BG, Kumar L. 3D printing: applications in tissue engineering medical devices and drug delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2022;23(4):92. doi: 10.1208/s12249-022-02242-8, PMID 35301602.

Wang C, Huang W, Zhou Y, He L, He Z, Chen Z. 3D printing of bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Bioact Mater. 2020;5(1):82-91. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.01.004, PMID 31956737.

Serhan M. Total iron measurement in human serum with a smartphone. AIChE Annu Meet Conf Proc. 2019 Nov;8:2800309. doi: 10.1109/JTEHM.2020.3005308.

Zhu W, Ma X, Gou M, Mei D, Zhang K, Chen S. 3D printing of functional biomaterials for tissue engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;40:103-12. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.03.014, PMID 27043763.

Zaszczynska A, Moczulska Heljak M, Gradys A, Sajkiewicz P. Advances in 3D printing for tissue engineering. Materials (Basel). 2021;14(12):3149. doi: 10.3390/ma14123149, PMID 34201163.

Jain A, Bansal KK, Tiwari A, Rosling A, Rosenholm JM. Role of polymers in 3D printing technology for drug delivery an overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24(42):4979-90. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666181226160040, PMID 30585543.

Afsana, Jain V, Haider N, Jain K. 3D printing in personalized drug delivery. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24(42):5062-71. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190215122208, PMID 30767736.

Badnjevic A, Skrbic R, Gurbeta Pokvic L, editors. CMBEBIH 2019. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-17971-7.

Jammalamadaka U, Tappa K. Recent advances in biomaterials for 3D printing and tissue engineering. J Funct Biomater. 2018;9(1):22. doi: 10.3390/jfb9010022, PMID 29494503.

Bae H, Chu H, Edalat F, Cha JM, Sant S, Kashyap A. Development of functional biomaterials with micro and nanoscale technologies for tissue engineering and drug delivery applications. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2014;8(1):1-14. doi: 10.1002/term.1494, PMID 22711442.

Richards DJ, Tan Y, Jia J, Yao H, Mei Y. 3D printing for tissue engineering. Isr J Chem. 2013;53(9-10):805-14. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201300086, PMID 26869728.

Dogan E. HHS Public Access. 2020. p. 1-28. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2020.100752.3D.

Wang S, Chen X, Han X, Hong X, Li X, Zhang H. A review of 3D printing technology in pharmaceutics: technology and applications now and future. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(2):416. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15020416, PMID 36839738.

Aldawood FK, Parupelli SK, Andar A, Desai S. 3D printing of biodegradable polymeric microneedles for transdermal drug delivery applications. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(2):237. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16020237, PMID 38399291.

Jamroz W, Szafraniec J, Kurek M, Jachowicz R. 3D printing in pharmaceutical and medical applications recent achievements and challenges. Pharm Res. 2018;35(9):176. doi: 10.1007/s11095-018-2454-x, PMID 29998405.

Park BJ, Choi HJ, Moon SJ, Kim SJ, Bajracharya R, Min JY. Pharmaceutical applications of 3D printing technology: current understanding and future perspectives. J Pharm Investig. 2018 Oct 29;49:575-85. doi: 10.1007/s40005-018-00414-y.

Kumar AV. A review paper on 3D-printing and various processes used in the 3D-printing. IJSREM. 2022;6(5):953-8. doi: 10.55041/IJSREM13278.

Bozkurt Y, Karayel E. 3D printing technology; methods biomedical applications future opportunities and trends. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;14:1430-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.07.050.

Nadagouda MN, Rastogi V, Ginn M. A review on 3D printing techniques for medical applications. Curr Opin Chem Eng. 2020 Jun;28:152-7. doi: 10.1016/j.coche.2020.05.007.

Garechana G, Rio Belver R, Bildosola I, Cilleruelo Carrasco E. A method for the detection and characterization of technology fronts: analysis of the dynamics of technological change in 3D printing technology. PLOS One. 2019;14(1):e0210441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210441, PMID 30615689.

Pandian A, Belavek C. A review of recent trends and challenges in 3D printing. 2016 ASEE North Central Section Conference. American Society for Engineering Education; 2016. p. 1-17.

Thakar CM, Parkhe SS, Jain A, Phasinam K, Murugesan G, Ventayen RJ. 3D printing: basic principles and applications. Mater Today Proc. 2022;51:842-9. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.06.272.

Xu W, Jambhulkar S, Zhu Y, Ravichandran D, Kakarla M, Vernon B. 3D printing for polymer/particle based processing: a review. Composites Part B: Engineering. 2021 Oct 15;223:109102. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109102.

Healy AV, Fuenmayor E, Doran P, Geever LM, Higginbotham CL, Lyons JG. Additive manufacturing of personalized pharmaceutical dosage forms via stereolithography. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(12):645. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11120645, PMID 31816898.

Xu X, Robles Martinez P, Madla CM, Joubert F, Goyanes A, Basit AW. Stereolithography (SLA) 3D printing of an antihypertensive polyprintlet: case study of an unexpected photopolymer drug reaction. Addit Manuf. 2020 May;33:101071. doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2020.101071.

Prasad LK, Smyth H. 3D printing technologies for drug delivery: a review. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2016;42(7):1019-31. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2015.1120743, PMID 26625986.

Giri BR, Song ES, Kwon J, Lee JH, Park JB, Kim DW. Fabrication of intragastric floating controlled release 3D printed theophylline tablets using hot-melt extrusion and fused deposition modeling. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(1):77. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12010077, PMID 31963484.

Konta AA, Garcia Pina M, Serrano DR. Personalised 3D printed medicines: which techniques and polymers are more successful? Bioengineering Basel. 2017;4(4):79. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering4040079, PMID 28952558.

Awad A, Fina F, Goyanes A, Gaisford S, Basit AW. 3D printing: principles and pharmaceutical applications of selective laser sintering. Int J Pharm. 2020;586:119594. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119594, PMID 32622811.

Fina F, Goyanes A, Madla CM, Awad A, Trenfield SJ, Kuek JM. 3D printing of drug-loaded gyroid lattices using selective laser sintering. Int J Pharm. 2018;547(1-2):44-52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.05.044, PMID 29787894.

Mazzoli A. Selective laser sintering in biomedical engineering. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2013;51(3):245-56. doi: 10.1007/s11517-012-1001-x, PMID 23250790.

Zeng K, Pal D, Stucker B. A review of thermal analysis methods in laser sintering and selective laser melting. International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium. 2012. p. 796-814. doi: 10.26153/tsw/15390.

Sefene EM. State-of-the-art of selective laser melting process: a comprehensive review. J Manuf Syst. 2022 Mar;63:250-74. doi: 10.1016/j.jmsy.2022.04.002.

Jia H, Sun H, Wang H, Wu Y, Wang H. Scanning strategy in selective laser melting (SLM): a review. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2021;113(9-10):2413-35. doi: 10.1007/s00170-021-06810-3.

Hsiang Loh GH, Pei E, Gonzalez Gutierrez J, Monzon M. An overview of material extrusion troubleshooting. Appl Sci. 2020;10(14):4776. doi: 10.3390/app10144776.

Ecker JV, Kracalik M, Hild S, Haider A. 3D material extrusion printing with biopolymers: a review. Chem Mater Eng. 2017;5(4):83-96. doi: 10.13189/cme.2017.050402.

Goh GD, Yap YL, Tan HK, Sing SL, Goh GL, Yeong WY. Process structure properties in polymer additive manufacturing via material extrusion: a review. Crit Rev Solid State Mater Sci. 2020;45(2):113-33. doi: 10.1080/10408436.2018.1549977.

Ozbolat IT, Peng W, Ozbolat V. Application areas of 3D bioprinting. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21(8):1257-71. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.04.006, PMID 27086009.

Murphy SV, Atala A. 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(8):773-85. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2958, PMID 25093879.

Seol YJ, Kang HW, Lee SJ, Atala A, Yoo JJ. Bioprinting technology and its applications. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46(3):342-8. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu148, PMID 25061217.

Daly AC, Prendergast ME, Hughes AJ, Burdick JA. Bioprinting for the biologist. Cell. 2021;184(1):18-32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.002, PMID 33417859.

Gungor Ozkerim PS, Inci I, Zhang YS, Khademhosseini A, Dokmeci MR. Bioinks for 3D bioprinting: an overview. Biomater Sci. 2018;6(5):915-46. doi: 10.1039/c7bm00765e, PMID 29492503.

Guo Y, Patanwala HS, Bognet B, Ma AW. Inkjet and inkjet-based 3D printing: connecting fluid properties and printing performance. Rapid Prototyp J. 2017;23(3):562-76. doi: 10.1108/RPJ-05-2016-0076.

Zub K, Hoeppener S, Schubert US. Inkjet printing and 3D printing strategies for biosensing analytical and diagnostic applications. Adv Mater. 2022;34(31):e2105015. doi: 10.1002/adma.202105015, PMID 35338719.

Napadensky E. The chemistry of inkjet inks. In: Chapter: 13. Inkjet 3D Printing; 2009. p. 249-61. doi: 10.1142/9789812818225_0013.

Clark EA, Alexander MR, Irvine DJ, Roberts CJ, Wallace MJ, Sharpe S. 3D printing of tablets using inkjet with UV photoinitiation. Int J Pharm. 2017;529(1-2):523-30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.06.085, PMID 28673860.

Mueller J, Shea K, Daraio C. Mechanical properties of parts fabricated with inkjet 3D printing through efficient experimental design. Mater Des. 2015;86:902-12. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2015.07.129.

Shahrubudin N, Lee TC, Ramlan R. An overview on 3D printing technology: technological materials and applications. Procedia Manuf. 2019;35:1286-96. doi: 10.1016/j.promfg.2019.06.089.

Liu J, Sun L, Xu W, Wang Q, Yu S, Sun J. Current advances and future perspectives of 3D printing natural-derived biopolymers. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;207:297-316. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.11.077, PMID 30600012.

Uhlmann E, Kersting R, Klein TB, Cruz MF, Borille AV. Additive manufacturing of titanium alloy for aircraft components. Procedia CIRP. 2015;35:55-60. doi: 10.1016/j.procir.2015.08.061.

Hitzler L, Alifui Segbaya F, Williams P, Heine B, Heitzmann M, Hall W. Additive manufacturing of cobalt-based dental alloys: analysis of microstructure and physicomechanical properties. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2018;2018(1):1-12. doi: 10.1155/2018/8213023.

DebRoy T, Wei HL, Zuback JS, Mukherjee T, Elmer JW, Milewski JO. Additive manufacturing of metallic components process structure and properties. Prog Mater Sci. 2018;92:112-224. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2017.10.001.

Murr LE. Frontiers of 3D printing/additive manufacturing: from human organs to aircraft fabrication. J Mater Sci Technol. 2016;32(10):987-95. doi: 10.1016/j.jmst.2016.08.011.

Caminero MA, Chacon JM, Garcia Moreno I, Rodriguez GP. Impact damage resistance of 3D printed continuous fibre reinforced thermoplastic composites using fused deposition modelling. Composites Part B: Engineering. 2018 Apr;148:93-103. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.04.054.

Wang X, Jiang M, Zhou Z, Gou J, Hui D. 3D printing of polymer matrix composites: a review and prospective. Composites Part B: Engineering. 2017;110:442-58. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.11.034.

Dizon JR, Espera AH, Chen Q, Advincula RC. Mechanical characterization of 3D-printed polymers. Addit Manuf. 2018;20:44-67. doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2017.12.002.

Haleem A, Javaid M. Additive manufacturing applications in industry 4.0: a review. J Ind Intg Mgmt. 2019;4(4):1-23. doi: 10.1142/S2424862219300011.

Lee JY, An J, Chua CK. Fundamentals and applications of 3D printing for novel materials. Appl Mater Today. 2017;7:120-33. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2017.02.004.

Chen Z, Sun X, Shang Y, Xiong K, Xu Z, Guo R. Dense ceramics with complex shape fabricated by 3D printing: a review. J Adv Ceram. 2021;10(2):195-218. doi: 10.1007/s40145-020-0444-z.

Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zhi P, Liu L, Liu C, Fang A. 3D printing method for bone tissue engineering scaffold. Med Nov Technol Devices. 2023;17:100205. doi: 10.1016/j.medntd.2022.100205, PMID 36909661.

Mani MP, Sadia M, Jaganathan SK, Khudzari AZ, Supriyanto E, Saidin S. A review on 3D printing in tissue engineering applications. J Polym Eng. 2022;42(3):243-65. doi: 10.1515/polyeng-2021-0059.

Tao O, Kort Mascort J, Lin Y, Pham HM, Charbonneau AM, ElKashty OA. The applications of 3D printing for craniofacial tissue engineering. Micromachines Basel. 2019;10(7):480. doi: 10.3390/mi10070480, PMID 31319522.

Stock UA, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering: current state and prospects. Annual Review of Medicine. 2001;52(1):443-51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.52.1.443.

Laurencin CT, Ambrosio AM, Borden MD, Cooper JA. Tissue engineering: orthopedic applications. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 1999;1:19-46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.1.1.19, PMID 11701481.

Peltola SM, Melchels FP, Grijpma DW, Kellomaki M. A review of rapid prototyping techniques for tissue engineering purposes. Ann Med. 2008;40(4):268-80. doi: 10.1080/07853890701881788, PMID 18428020.

Sipe JD. Tissue engineering and reparative medicine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;961:1-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb03040.x, PMID 12081856.

Thomas AC, Campbell GR, Campbell JH. Advances in vascular tissue engineering. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2003;12(5):271-6. doi: 10.1016/S1054-8807(03)00086-3, PMID 14507577.

Asmaria T, Sajuti D, Ain K. 3D printed PLA of gallbladder for virtual surgery planning. AIP Conf Proc. 2020 Apr;2232. doi: 10.1063/5.0001732.

Serris I, Serris P, Frey KM, Cho H. Development of 3D-printed layered PLGA films for drug delivery and evaluation of drug release behaviors. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020;21(7):256. doi: 10.1208/s12249-020-01790-1, PMID 32888114.

Mohapatra S, Kar RK, Biswal PK, Bindhani S. Approaches of 3D printing in current drug delivery. Sensors International. 2022;3:100146. doi: 10.1016/j.sintl.2021.100146.

Nasiri G, Ahmadi S, Shahbazi MA, Nosrati Siahmazgi V, Fatahi Y, Dinarvand R. 3D printing of bioactive materials for drug delivery applications. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2022;19(9):1061-80. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2022.2112944, PMID 35953890.

Karavasili C, Eleftheriadis GK, Gioumouxouzis C, Andriotis EG, Fatouros DG. Mucosal drug delivery and 3D printing technologies: a focus on special patient populations. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;176:113858. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113858, PMID 34237405.

Xu X, Awad A, Robles Martinez P, Gaisford S, Goyanes A, Basit AW. Vat photopolymerization 3D printing for advanced drug delivery and medical device applications. J Control Release. 2021;329:743-57. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.10.008, PMID 33031881.

Diogo C. 3D printing of pharmaceutical drug delivery systems. Archives of Organic and Inorganic Chemical Sciences. 2018;1(2):1-5. doi: 10.32474/AOICS.2018.01.000109.

Dubashynskaya NV, Petrova VA, Skorik YA. Biopolymer drug delivery systems for oromucosal application: recent trends in pharmaceutical R & D. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(10):5359. doi: 10.3390/ijms25105359, PMID 38791397.

Tian Y, Orlu M, Woerdenbag HJ, Scarpa M, Kiefer O, Kottke D. Oromucosal films: from patient centricity to production by printing techniques. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2019;16(9):981-93. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2019.1652595, PMID 31382842.

Eleftheriadis GK, Ritzoulis C, Bouropoulos N, Tzetzis D, Andreadis DA, Boetker J. Unidirectional drug release from 3D printed mucoadhesive buccal films using FDM technology: in vitro and ex vivo evaluation. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2019;144:180-92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2019.09.018, PMID 31550525.

Arany P, Papp I, Zichar M, Regdon G, Beres M, Szaloki M. Manufacturing and examination of vaginal drug delivery system by fdm 3d printing. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(10):1714. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13101714, PMID 34684007.

Fu J, Yu X, Jin Y. 3D printing of vaginal rings with personalized shapes for controlled release of progesterone. Int J Pharm. 2018;539(1-2):75-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.01.036, PMID 29366944.

Elkasabgy NA, Mahmoud AA, Maged A. 3D printing: an appealing route for customized drug delivery systems. Int J Pharm. 2020 Jul;588:119732. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119732, PMID 32768528.

Xu X, Awwad S, Diaz Gomez L, Alvarez Lorenzo C, Brocchini S, Gaisford S. 3D printed punctal plugs for controlled ocular drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(9):1421. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13091421, PMID 34575497.

Mostafa M, Al Fatease A, Alany RG, Abdelkader H. Recent advances of ocular drug delivery systems: prominence of ocular implants for chronic eye diseases. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(6):1746. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15061746, PMID 37376194.

Ahmed S, Amin MM, Sayed S. Ocular drug delivery: a comprehensive review. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2023;24(2):66. doi: 10.1208/s12249-023-02516-9, PMID 36788150.