Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 4, 38-44Review Article

POLYMERIC NANOCARRIERS IN THERAPEUTIC DELIVERY: CURRENT TRENDS AND FUTURE HORIZONS

ANJALI MISHRA1*, APOORVA KUMARI2, GAURI BARAIK3, ANAMIKA PALAK4

*1Department of Pharmacy, Sarala Birla University, Mahilong, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India. 2,3,4Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Jharkhand Rai University, Namkum, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India.

*Corresponding author: Anjali Mishra; *Email: anjalimishra674@gmail.com

Received: 15 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 10 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

This detailed review on ‘Polymeric nanocarriers’, aims to provide an in-depth understanding of polymeric nano entities as a novel and efficient platform for drug delivery, with a focus on improving therapeutic precision and minimizing side effects. The study examines the design principles, drug loading capabilities, and release profiles of polymeric nanoparticles, along with their mechanisms for passive and active targeting. It also highlights their current applications in areas such as cancer therapy, gene delivery, and vaccination, while addressing the key challenges, including biocompatibility, scalability, and regulatory approval. Future trends such as stimuli-responsive systems and integration with artificial intelligence are also discussed. Polymeric nanoparticles offer versatile and highly tunable systems for controlled and targeted drug delivery. With continued advancements in material science and nanotechnology, they hold significant promise for transforming conventional therapies and advancing the field of personalized medicine, despite existing barriers that must still be addressed for widespread clinical use.

Keywords: Polymeric nanoparticles, Nanocarriers, Dendrimers, Sustained release, Chitosan, Sodium alginate

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i4.7041 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) are an emerging tool in drug delivery systems (DDS), designed to address various challenges associated with traditional drug delivery, particularly in the context of cancer therapy [1]. Their primary advantage lies in overcoming obstacles related to the precise delivery of drugs to tumor cells while minimizing side effects on surrounding healthy tissue. This targeted approach can improve the therapeutic efficacy of drugs while reducing toxicity. PNPs typically range in size from 1 nm to 1000 nm [2]. Their small size is crucial in allowing efficient penetration into tissues and enhanced interaction with cellular structures. In nanocapsule, the drug is enclosed within a core that is surrounded by a polymeric shell. This arrangement can protect the drug from degradation before it reaches its target site. In some cases, the core itself may serve as the drug, with the polymer layer serving as a protective barrier. These are made from a network of cross-linked polymers, within which the drug is imgded. The drug is uniformly distributed throughout the polymer matrix [3, 4].

In both types of nanoparticles, the drug may be either encapsulated inside the particle (in the case of nanocapsules) or imgded within the polymer matrix (in the case of nanospheres). Additionally, drugs can also be adsorbed onto the surface of the nanoparticle, which can affect the release profile and interaction with cells [5].

Polymeric nanocarriers can be engineered to target specific cells or tissues, such as cancer cells, by modifying their surface properties (e. g., attaching ligands or antibodies). This allows for more localized drug release, improving efficacy and reducing off-target effects. Due to their size and surface properties, polymeric nanoparticles can exploit the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, where they accumulate in tumor tissues with leaky vasculature and poor lymphatic drainage. By targeting drugs directly to diseased cells, polymeric nanocarriers reduce the exposure of healthy tissues to the drug, which can significantly reduce adverse side effects commonly associated with chemotherapy and other treatments. The rate of drug release can be precisely controlled, preventing the rapid release of high concentrations of drug, which could cause systemic toxicity [6].

Polymeric nanoparticles can improve the solubility and bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs by encapsulating them in the nanoparticle matrix, allowing for more efficient absorption in the body. Encapsulation within polymeric nanocarriers can protect sensitive drugs (e. g., proteins, peptides, and nucleic acids) from enzymatic degradation and premature metabolism in the body. Polymeric nanoparticles can be designed to release their payload gradually over an extended period, ensuring prolonged therapeutic action with fewer doses. This reduces the need for frequent administration and improves patient compliance. Polymeric nanoparticles can be engineered to respond to specific stimuli in the body, such as changes in pH, temperature, or enzyme activity. This allows for on-demand release of the drug at the target site (e. g., within a tumor environment). Polymeric nanocarriers are suitable for a broad range of therapeutic agents, including small-molecule drugs, proteins, peptides, nucleic acids (DNA, RNA), and even vaccines [7-9]. Nanocarriers can be designed as nanocapsules or nanospheres, offering flexibility in drug loading and release mechanisms. Additionally, the surface of these nanoparticles can be modified to improve biocompatibility and functionalize them for specific targeting. Many polymeric materials used for nanoparticles (e. g., PLGA, chitosan, poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)) are biocompatible and biodegradable. These polymers break down into non-toxic byproducts, reducing the risk of long-term accumulation in the body and minimizing adverse reactions. Surface modifications (such as PEGylation) can help reduce the immune system’s recognition of the nanoparticles, thus increasing their circulation time in the bloodstream and improving therapeutic efficiency. Encapsulation in polymeric nanocarriers can protect drugs from environmental factors such as oxidation, moisture, and light. This is especially important for biologics like proteins and vaccines, which are prone to instability in their native forms [10].

The enhanced stability of drug formulations within nanoparticles can improve their shelf life, making them more suitable for storage and transportation. For cancer treatments, polymeric nanocarriers can help overcome drug resistance mechanisms. The nanoparticles can alter the drug's pharmacokinetics and biodistribution, bypassing cellular efflux pumps or other resistance mechanisms commonly found in tumor cells. Polymeric nanocarriers can be designed to deliver multiple agents (e. g., a combination of chemotherapy drugs and siRNA or other biologics), which can work synergistically to counteract resistance and improve treatment outcomes [11]. Due to controlled and sustained release, polymeric nanocarriers can reduce the need for frequent drug administration, leading to greater patient convenience and adherence to treatment regimens. nanocarriers can be formulated for oral, transdermal, or even inhalation delivery, offering non-invasive alternatives to intravenous drug administration. Polymeric nanoparticles can be designed not only to deliver drugs but also to carry imaging agents. This creates the potential for theranostic applications, where the nanoparticle can both treat the disease and monitor its progress in real-time using imaging techniques like MRI or fluorescence. Many polymeric nanoparticles can be synthesized using scalable and cost-effective methods, which makes them viable for large-scale pharmaceutical production. Additionally, the materials used for fabrication can be relatively inexpensive compared to other nanomaterials [12, 13].

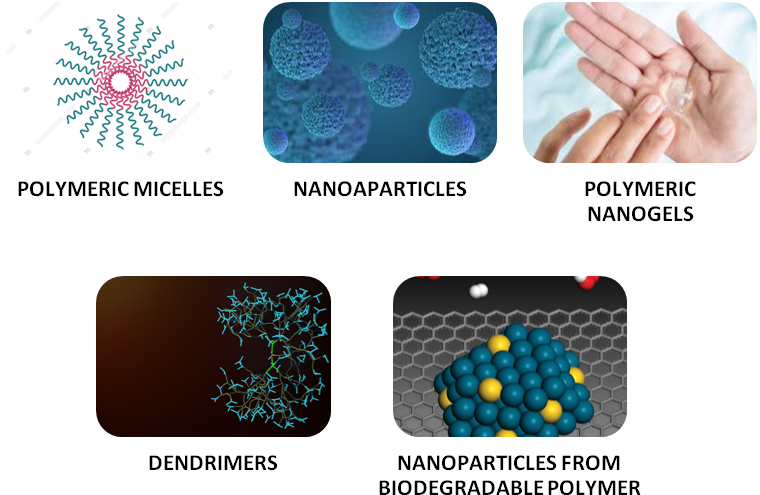

Fig. 1: Types of polymeric nanocarriers

Polymeric micelles

Polymeric micelles are a class of polymer-based nanoparticles that are being widely explored in nanomedicine, especially for drug delivery. These micelles are typically formed from amphiphilic block copolymers, which contain both hydrophilic (water-attracting) and hydrophobic (water-repelling) blocks. In an aqueous solution, the hydrophobic blocks aggregate to form a core, while the hydrophilic blocks extend outward to form a stabilizing shell. This unique core-shell structure allows the micelles to encapsulate hydrophobic drugs in the core while the shell stabilizes the structure in aqueous environments and enhances biocompatibility [14].

The formation of polymeric micelles is driven by the hydrophobic interactions between the copolymer blocks. When amphiphilic block copolymers are introduced into water, the hydrophobic segments tend to aggregate, minimizing exposure to water, while the hydrophilic segments interact with the surrounding aqueous medium. The size and stability of the micelles can be influenced by factors such as the polymer composition (length of the hydrophilic and hydrophobic blocks), concentration, and solvent conditions like temperature, pH, and ionic strength. These factors allow for the fine-tuning of micelle characteristics, making them adaptable for different applications [15].

Polymeric micelles have several important properties that make them well-suited for drug delivery. First, they are typically small, ranging from 10 to 100 nm in diameter, which allows them to navigate through the bloodstream and reach target sites. Their small size also helps them evade rapid clearance by the immune system, enhancing their circulation time. Additionally, the micelles' core-shell structure enables them to solubilize hydrophobic drugs, which are typically poorly soluble in water, improving the bioavailability of these compounds. Furthermore, polymeric micelles can provide controlled drug release through diffusion, polymer degradation, or stimuli-responsive mechanisms (e. g., pH or temperature changes), allowing for more precise and prolonged therapeutic effects. Finally, since they are made from biocompatible and biodegradable polymers, polymeric micelles are generally safe for use in vivo, minimizing the risk of toxicity [16-18].

There are different types of polymeric micelles based on the composition and design of the copolymers used. The most common type consists of block copolymer micelles, where two or more different polymer blocks form the core and shell. For instance, the hydrophilic block might be polyethylene glycol (PEG) or poly(ethylene oxide), while the hydrophobic block could be polylactic acid (PLA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), or polycaprolactone (PCL). In some cases, polymeric micelles are also designed with drug conjugates, where the therapeutic agent is covalently attached to the polymer chain, allowing for a more controlled release. Furthermore, stimuli-responsive micelles have been developed that release their cargo in response to specific triggers such as changes in pH, temperature, or enzymatic activity, enhancing the precision of drug delivery [19].

Polymeric micelles offer a range of applications, particularly in the field of drug delivery. One of the primary uses is in the delivery of poorly water-soluble drugs, such as many anticancer agents (e. g., paclitaxel, doxorubicin), which can be encapsulated within the hydrophobic core of the micelles. This increases their solubility, bioavailability, and therapeutic efficacy while reducing side effects associated with systemic administration. Polymeric micelles are also being used for gene therapy, where they serve as carriers for genetic materials such as DNA, RNA, or siRNA. The micelles protect these sensitive molecules from degradation in the bloodstream and deliver them efficiently to target cells. Additionally, polymeric micelles are useful for delivering proteins, peptides, and other biologics by protecting them from enzymatic degradation, improving their stability and bioavailability. For targeted drug delivery, micelles can be functionalized with targeting ligands such as antibodies or peptides, which specifically bind to receptors on target cells, ensuring that the drug is delivered to the intended site, minimizing off-target effects [20].

The advantages of polymeric micelles as drug delivery systems are numerous. Their small size and stability help prolong circulation time in the bloodstream and evade the immune system, while their core-shell structure enables the solubilization of hydrophobic drugs and controlled release profiles. The use of biocompatible and biodegradable materials ensures that these micelles are safe for in vivo use. Additionally, their ability to deliver a wide variety of therapeutic agents, from small-molecule drugs to genetic materials, makes them versatile carriers for various treatment modalities. Moreover, the surface can be easily modified with ligands for targeted delivery, enhancing therapeutic efficacy and reducing side effects [21].

Despite their promise, several challenges remain in the development and application of polymeric micelles. The synthesis of the block copolymers required for micelle formation can be complex and costly, and standardizing the production process is critical for ensuring consistency. Moreover, scaling up the production of polymeric micelles for clinical use is still a challenge, requiring optimized methods that maintain quality while reducing costs. Additionally, the release kinetics of drugs from polymeric micelles need to be carefully controlled to ensure effective treatment. This is particularly challenging when designing micelles for different types of drugs or disease conditions, as the release rate must be tailored to each specific case. Finally, the in vivo performance of polymeric micelles can be influenced by factors such as polymer degradation rates, stability in circulation, and interactions with the immune system, which must be optimized to achieve the desired therapeutic outcomes [22, 23].

Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles are minuscule particles with a size range typically between 1 and 100 nanometers. Due to their extremely small size and high surface area-to-volume ratio, they exhibit unique physical and chemical properties that make them ideal for applications in medicine, especially in drug delivery. Among the different types of nanoparticles used in therapeutics, polymeric nanocarriers are particularly promising. These are nanoparticles composed of natural or synthetic polymers that can carry drugs, genes, or other bioactive molecules to targeted areas in the body. Their design allows for protection of the therapeutic agent, controlled release, and often targeted delivery, which enhances the efficacy of treatment and reduces side effects [24].

Polymeric nanocarriers are primarily made using biodegradable and biocompatible polymers. Common polymers include PLGA (poly lactic-co-glycolic acid), PLA (polylactic acid), PEG (polyethylene glycol), chitosan, alginate, and poloxamers. These materials are chosen for their ability to safely degrade within the body into non-toxic byproducts. Polymeric nanoparticles generally exist in two forms, nanospheres, where the drug is dispersed throughout the polymer matrix [25]. Nanocapsules which consist of a core (often liquid or solid) surrounded by a polymeric shell. The drug can be loaded through physical entrapment, adsorption, or chemical bonding. The design depends on the nature of the drug, the intended release profile, and the site of action.

Polymeric nanocarriers can deliver drugs in a controlled and targeted manner. After administration, these nanoparticles circulate in the bloodstream and can reach the target site through two main mechanisms. Passive targeting, where the nanoparticles accumulate in the target tissues (like tumors) due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, which is common in cancerous tissues with leaky vasculature. Active targeting, which involves surface modification of nanoparticles with ligands such as antibodies, peptides, or small molecules that can recognize and bind to specific receptors overexpressed on the target cells. Once at the target site, the drug is released via various mechanisms: polymer degradation, pH sensitivity, enzymatic cleavage, or external stimuli like heat or magnetic fields [26].

Despite their promising features, polymeric nanocarriers face several scientific and regulatory challenges, one of the most notable advantages of nanoparticles is their ability to enhance the bioavailability of drugs, particularly those that are poorly soluble or unstable in aqueous environments. The small size of nanoparticles allows them to penetrate biological barriers (such as the blood-brain barrier or cellular membranes), improving the distribution of drugs in the body. Nanoparticles can also be engineered to improve the solubility and stability of hydrophobic drugs, making them more effective when delivered to target tissues. Nanoparticles provide the ability for controlled drug release, which helps reduce dosing frequency and improve patient compliance. Furthermore, they can be designed for targeted delivery to specific sites in the body, such as tumors, by using surface modifications like ligands or antibodies that recognize specific receptors on diseased cells. This minimizes the side effects associated with systemic drug distribution and maximizes therapeutic efficacy at the site of action [27, 28].

Many nanoparticles, especially those made from biodegradable and biocompatible polymers, degrade naturally into non-toxic products once they have fulfilled their purpose in the body. This reduces the risk of accumulation in tissues and organs, leading to safer drug delivery systems. The natural biodegradability of materials like PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) ensures that there is no long-term toxic buildup [29].

Nanoparticles can be engineered for multiple functions. They can carry both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs, proteins, nucleic acids, and other bioactive molecules. Additionally, they can serve dual purposes, such as delivering therapeutic agents and acting as diagnostic tools (i. e., theranostics). This versatility opens a wide range of applications, from cancer therapy to gene delivery and vaccine development [30].

Since nanoparticles can be specifically directed to the targeted tissues or organs, they often reduce the exposure of healthy tissues to toxic drugs. This targeted delivery helps minimize the toxic side effects often seen with conventional therapies, such as chemotherapy, which affects both cancerous and healthy cells. Moreover, the protective coating of nanoparticles ensures that drugs are released only in the desired area. Even though nanoparticles are laced with multiple merits, there are also some challenges associated with it. One of the significant challenges associated with nanoparticles is ensuring their physical and chemical stability during storage and circulation in the body [31].

Nanoparticles may aggregate, lose their surface characteristics, or degrade, particularly in complex biological environments. These issues can affect their performance, the release profile of drugs, and the overall safety of the system. While many nanoparticles are designed to be biocompatible, there is still concern about their potential to provoke an immune response. The body’s immune system might recognize nanoparticles as foreign objects and initiate an immune reaction, leading to rapid clearance of the particles or, in some cases, inflammatory responses. Additionally, the long-term effects of nanoparticle accumulation in the body remain an area of active research, as certain nanoparticles may pose risks if they do not degrade as expected [32].

The large-scale production of nanoparticles with consistent size, shape, and surface characteristics is a challenging task. The methods used to synthesize nanoparticles often have limitations in terms of reproducibility, and scaling up these processes from the laboratory to industrial production requires overcoming technical and cost-related hurdles. Additionally, ensuring uniformity and batch-to-batch reproducibility is critical for regulatory approval and market readiness [33].

The regulatory approval process for nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems can be lengthy and complex. Regulatory bodies, such as the FDA, require extensive preclinical and clinical testing to ensure the safety and efficacy of nanomedicines. However, since nanoparticles are a relatively new class of drug delivery vehicles, regulatory guidelines are still evolving, and comprehensive safety assessments are required to evaluate their long-term effects on human health [34].

Nanoparticles may encounter biological barriers such as the reticuloendothelial system (RES), liver, or spleen, which can lead to the rapid clearance of the nanoparticles from the bloodstream before they reach the target tissue. Additionally, nanoparticles must be designed to evade immune cells and avoid recognition by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS). If nanoparticles are cleared too quickly, they will not have sufficient time to release their therapeutic cargo at the intended site, thus diminishing their efficacy [35].

Polymeric nanogels

Polymeric nanogels are a class of nanocarriers composed of cross-linked polymer networks, designed to deliver drugs, proteins, nucleic acids, and other bioactive agents. These nanogels are typically characterized by their ability to absorb large amounts of water, making them highly swollen, soft, and flexible. This unique feature enables them to encapsulate both hydrophobic and hydrophilic molecules, which is beneficial in enhancing the solubility and stability of therapeutic agents that would otherwise be difficult to deliver through conventional means [36].

The cross-linked structure of polymeric nanogels provides them with exceptional stability under physiological conditions, preventing premature drug release before they reach their intended target. Moreover, the polymer chains forming the nanogel network can be tailored to respond to various stimuli, such as pH, temperature, ionic strength, or specific enzymes, making them highly versatile for controlled drug release. This "smart" feature allows the nanogels to release their payload in response to environmental changes in the body, such as the acidic microenvironment of tumors, providing an effective method for targeted drug delivery.

One of the significant advantages of polymeric nanogels is their ability to protect sensitive drugs, like proteins or genes, from degradation or denaturation. The gel-like structure acts as a shield, preventing the degradation of bioactive compounds during circulation in the bloodstream. Additionally, their small size and biocompatibility enable them to avoid rapid clearance by the immune system and accumulate in diseased tissues through mechanisms such as the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [37, 38].

Polymeric nanogels are particularly promising in the treatment of cancers, where they can be engineered to deliver chemotherapeutic agents directly to tumors, thereby minimizing the exposure of healthy tissues to toxic drugs. Their ability to encapsulate a variety of bioactive agents also makes them suitable for gene therapy, vaccine delivery, and wound healing applications. Furthermore, the flexibility of the polymeric network allows the inclusion of targeting ligands on their surface, enhancing their specificity for certain cell types, such as cancer cells or specific immune cells.

However, while polymeric nanogels offer significant promise in drug delivery, challenges remain. Their large-scale production and reproducibility are not without difficulties, as precise control over the gelation process is required to ensure consistent drug loading and release profiles. Additionally, there are concerns regarding the long-term fate of nanogels within the body, including their potential accumulation in organs like the liver or spleen, which warrants thorough evaluation of their biocompatibility and biodegradability. Despite these challenges, ongoing research continues to explore innovative solutions to optimize polymeric nanogels for clinical applications, and they are increasingly viewed as a valuable tool in the development of next-generation drug delivery systems [39, 40].

Dendrimers

Dendrimers are highly branched, nanoscale macromolecules that possess a distinct, tree-like structure. They are composed of a central core surrounded by successive layers of repeating branching units, known as generations. Each generation adds additional branches that radiate outward from the core, creating a highly symmetric and well-defined structure. The branching nature of dendrimers creates a large surface area with numerous available functional groups. This unique architecture contrasts with traditional linear polymers, where the structure is more uniform and lacks the degree of branching that dendrimers possess. The size, shape, and surface functionality of dendrimers can be precisely controlled during synthesis, making them highly customizable for a wide variety of applications, particularly in the biomedical and pharmaceutical fields [41].

One of the most significant advantages of dendrimers is their ability to carry a substantial payload of therapeutic agents, such as drugs, nucleic acids, or proteins, within their highly branched interior cavities. These cavities, also referred to as the dendrimer's core-shell structure, can encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules. This versatility makes dendrimers ideal for delivering a wide range of drug types that may otherwise be challenging to deliver using conventional systems. Additionally, the surface of dendrimers can be functionalized with various chemical groups, including targeting ligands, to enhance the specificity of drug delivery. This allows for targeted therapy, where drugs are delivered directly to the site of action (e. g., a tumor or infected tissue), reducing the potential for systemic side effects and improving therapeutic outcomes [42, 43].

Dendrimers exhibit a phenomenon known as multivalency, where the numerous functional groups on their surface enable multiple simultaneous interactions with biological targets. This can be particularly useful for achieving highly specific binding to cell receptors, antibodies, or other biomolecules. For example, dendrimers can be functionalized with ligands that specifically recognize cancer cell receptors, allowing for selective drug delivery to tumour sites. Moreover, dendrimers can also be used in combination with imaging agents, providing a powerful platform for theranostics, the combination of therapy and diagnostics in a single system. This ability to carry both therapeutic and diagnostic agents makes dendrimers an essential tool in personalized medicine, where therapies can be tailored to the individual patient based on their specific disease markers [44].

The controlled release of drugs from dendrimers is another highly desirable feature. Drugs encapsulated within dendrimers can be released in response to specific environmental triggers, such as changes in pH, temperature, or the presence of enzymes. For example, in the case of cancer therapy, dendrimers can be engineered to release their drug payload in the acidic microenvironment of a tumour, offering a highly localized and effective treatment strategy. This capability to control the timing and location of drug release not only enhances the bioavailability of the drug but also reduces the chances of premature drug release, which could lead to decreased efficacy or increased toxicity [45, 46].

Dendrimers can be modified to avoid recognition and rapid clearance by the immune system. The surface of dendrimers can be functionalized with stealthing agents like polyethylene glycol (PEG) to reduce opsonization (coating by immune cells) and prevent early removal from circulation by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). This surface modification allows dendrimers to circulate in the bloodstream for a longer period, increasing the likelihood of reaching the intended target site. Additionally, dendrimers can be engineered to improve targeted delivery to specific cells or tissues. Functional groups on their surface can be conjugated with targeting ligands, such as antibodies, peptides, or small molecules, that specifically bind to receptors overexpressed on the target cells. This level of targeting ensures that the therapeutic agents are delivered directly to the disease site, enhancing the efficacy of the treatment and reducing damage to healthy tissues [47].

While dendrimers offer remarkable advantages in drug delivery, there are concerns regarding their toxicity, especially at higher concentrations. The highly charged surfaces of dendrimers can interact with cell membranes, leading to potential cytotoxicity or immune responses. The functional groups on the dendrimer surface, particularly those with positive charges, can disrupt cell membranes or trigger inflammatory responses, which can cause harm to healthy tissues. Therefore, careful optimization of the surface chemistry and size of dendrimers is required to minimize these adverse effects. Additionally, although dendrimers are often designed to be biodegradable, their long-term fate in the body still requires more extensive study to understand potential accumulation and toxicity over time, particularly in organs like the liver or spleen. The synthesis of dendrimers, although precise and highly customizable, is often a complex and multi-step process. This complexity can lead to challenges in scalability for large-scale production, making dendrimers relatively expensive compared to other drug delivery systems. The cost of producing dendrimers may limit their widespread clinical use, especially when compared to other nanoparticle-based delivery systems that are simpler to manufacture [48]. Furthermore, the uniformity and reproducibility of dendrimer production are critical for their consistent performance, but achieving these qualities on a large scale can be challenging due to the intricate synthetic pathways required. Despite the challenges, the future of dendrimers in medicine looks promising. Researchers are exploring novel ways to overcome toxicity concerns, improve their scalability, and enhance their biodegradability. Advances in dendrimer design, such as the development of dendrimers with responsive surfaces that can change their properties in response to the environment, are helping to further their applications. Dendrimers hold great potential in the field of gene therapy, where they can be used to deliver nucleic acids, such as DNA or RNA, to target cells, enabling gene editing or gene silencing. They also show promise in vaccine development and wound healing. As new methods for dendrimer synthesis and surface functionalization are developed, their use in a wide range of therapeutic areas will continue to expand [49, 50].

Nanoparticles from biodegradable polymer

Polymeric particles made from biodegradable polymers are an important class of materials used in drug delivery, biomedical applications, and tissue engineering. These particles, which include nanoparticles, microparticles, and nanocapsules, are fabricated from polymers that can break down into non-toxic by-products within the body. The use of biodegradable polymers for creating these particles offers significant advantages, particularly in medical and pharmaceutical applications, because they can safely degrade over time, reducing the need for removal after their intended purpose is fulfilled [51].

Biodegradable polymeric particles are typically created from materials like poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), chitosan, and gelatin, all of which are known for their biocompatibility and biodegradability. These materials undergo hydrolytic degradation in the body, breaking down into simple, non-toxic molecules like lactic acid or glycolic acid, which are then naturally eliminated. This property eliminates concerns related to the long-term accumulation of synthetic materials in the body, a significant challenge with non-biodegradable systems [52].

One of the primary advantages of using biodegradable polymeric particles is their controlled release of encapsulated drugs. By manipulating the polymer's properties, such as the polymer's molecular weight or the degree of cross-linking, the release rate of the drug can be controlled. This allows for sustained and targeted delivery, minimizing the frequency of dosing and reducing side effects associated with conventional drug delivery systems. For instance, in cancer therapy, biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles can deliver chemotherapeutic drugs directly to tumor sites, increasing efficacy while minimizing damage to healthy tissues [53].

Additionally, biodegradable polymeric particles can encapsulate a wide range of bioactive agents, including hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs, proteins, and nucleic acids. This makes them highly versatile and suitable for various therapeutic applications, from controlled release of small molecules to gene therapy. These particles can also be surface-modified to target specific tissues or cells, improving the specificity and effectiveness of treatment.

Despite the many advantages, there are challenges associated with biodegradable polymeric particles. Manufacturing these particles with consistent size, uniform drug loading, and desired degradation profiles remains a challenge, particularly for large-scale production. The degradation rate of the polymers can also vary depending on the environmental conditions, which can affect the timing of drug release. Additionally, ensuring that the degradation products are safe and do not cause adverse reactions in the body is crucial for the success of these systems [54].

Concluding, biodegradable polymeric particles represent a promising technology in drug delivery and other biomedical applications. Their ability to deliver drugs in a controlled and targeted manner, combined with their biodegradability and biocompatibility, makes them an attractive option for treating various diseases. However, further research is needed to address the challenges related to their synthesis, scalability, and degradation behaviour to fully realize their potential in clinical settings [55].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, polymeric nanocarriers have emerged as a highly promising and versatile tool in the field of drug delivery. Their unique properties, including biocompatibility, biodegradability, and the ability to encapsulate a wide range of therapeutic agents, have revolutionized how drugs are delivered and targeted in the body. Polymeric nanocarriers provide significant improvements in drug stability, bioavailability, and controlled release, which are critical for enhancing the efficacy and reducing the side effects of treatments. These nanocarriers are especially advantageous in the delivery of chemotherapeutic agents, gene therapies, and vaccines, where precision in targeting specific cells or tissues is paramount.

The use of polymeric nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery is a particularly compelling aspect of their application. By functionalizing the surface of nanoparticles with ligands, such as antibodies, peptides, or other molecules, drugs can be directed to tissues or cells, such as tumor cells or diseased tissues, thus minimizing off-target effects and systemic toxicity. Moreover, the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect in tumors further boosts the potential of these carriers for passive targeting. Additionally, advancements in stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems, which release drugs in response to specific internal or external cues (such as pH, temperature, or light), are pushing the boundaries of precision medicine by allowing for even more tailored therapeutic interventions.

Despite the many advantages of polymeric nanocarriers, several challenges remain that need to be addressed for their widespread clinical adoption. Issues related to the scalability and reproducibility of nanocarrier production remain significant barriers to their commercialization. The toxicological safety of these systems, especially in long-term applications, also requires thorough investigation to ensure that degradation products do not elicit adverse effects in patients. Regulatory challenges further complicate the path toward clinical approval, as rigorous testing is required to meet safety and efficacy standards.

Looking to the future, the integration of polymeric nanocarriers with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning offers exciting possibilities for optimizing the design and delivery of therapeutics. These technologies could enable the development of more sophisticated, personalized drug delivery systems tailored to individual patient profiles, thus improving therapeutic outcomes. Moreover, the increasing focus on combination therapies and gene delivery will expand the range of conditions that polymeric nanoparticles can treat, including genetic disorders, cancer, and infectious diseases.

In conclusion, while challenges persist, the ongoing advancements in the design, production, and application of polymeric nanocarriers position them as a cornerstone in the future of drug delivery. Their potential to revolutionize therapeutic treatments through targeted delivery, controlled release, and customised medicine promises to improve patient outcomes, reduce side effects, and offer new avenues for treating a wide range of diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all co-authors for their valuable input, critical review, and collaborative efforts in the preparation of this manuscript.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

De R, Mahata MK, Kim KT. Structure-based varieties of polymeric nanocarriers and influences of their physicochemical properties on drug delivery profiles. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022;9(10):e2105373. doi: 10.1002/advs.202105373, PMID 35112798.

Tewari AK, Upadhyay SC, Kumar M, Pathak K, Kaushik D, Verma R. Insights on development aspects of polymeric nanocarriers: the translation from bench to clinic. Polymers. 2022;14(17):3545. doi: 10.3390/polym14173545, PMID 36080620.

Cao Z, Li D, Wang J, Yang X. Reactive oxygen species sensitive polymeric nanocarriers for synergistic cancer therapy. Acta Biomater. 2021 Aug;130:17-31. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.05.023, PMID 34058390.

Haider M, Zaki KZ, El Hamshary MR, Hussain Z, Orive G, Ibrahim HO. Polymeric nanocarriers: a promising tool for early diagnosis and efficient treatment of colorectal cancer. J Adv Res. 2022 Jul;39:237-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.11.008, PMID 35777911.

Haider M, Zaki KZ, El Hamshary MR, Hussain Z, Orive G, Ibrahim HO. Polymeric nanocarriers: a promising tool for early diagnosis and efficient treatment of colorectal cancer. J Adv Res. 2022 Jul;39:237-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.11.008, PMID 35777911.

Mazumdar S, Chitkara D, Mittal A. Exploration and insights into the cellular internalization and intracellular fate of amphiphilic polymeric nanocarriers. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11(4):903-24. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.02.019, PMID 33996406.

Lagarrigue P, Moncalvo F, Cellesi F. Non-spherical polymeric nanocarriers for therapeutics: the effect of shape on biological systems and drug delivery properties. Pharmaceutics. 2022;15(1):32. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15010032, PMID 36678661.

Zhang J, Yang X, Chang Z, Zhu W, Ma Y, He H. Polymeric nanocarriers for therapeutic gene delivery. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2025;20(1):101015. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2025.101015, PMID 39931356.

Saraf A, Sharma M. Polymeric nanocarriers for advanced cancer therapy: current developments and future prospects. In: Bhattacharya S, Sharma M, Page AB, Mukherjee D, Kanugo A, editors. Advancements in cancer research: exploring diagnostics and therapeutic breakthroughs. Bentham Science Publishers; 2025. p. 232-58. doi: 10.2174/9789815305906125010016.

Encinas Basurto D, Eedara BB, Mansour HM. Biocompatible biodegradable polymeric nanocarriers in dry powder inhalers (DPIs) for pulmonary inhalation delivery. J Pharm Investig. 2024;54(2):145-60. doi: 10.1007/s40005-024-00671-0.

Khawas S. Innovations in nanocarrier technology for targeted therapeutics: a comprehensive review. Redvet. 2024;25(1):1076-89. doi: 10.69980/redvet.v25i1.780.

Biswas A, Kumar S, Choudhury AD, Bisen AC, Sanap SN, Agrawal S. Polymers and their engineered analogues for ocular drug delivery: enhancing therapeutic precision. Biopolymers. 2024;115(4):e23578. doi: 10.1002/bip.23578, PMID 38577865.

Vahab SA, KA, MS, Kumar VS. Exploring chitosan nanoparticles for enhanced therapy in neurological disorders: a comprehensive review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2025;398(3):2151-67. doi: 10.1007/s00210-024-03507-8.

Gagliardi M, Borri C. Polymer nanoparticles as smart carriers for the enhanced release of therapeutic agents to the CNS. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23(3):393-410. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666161027111542, PMID 27799038.

Ribovski L, Hamelmann NM, Paulusse JM. Polymeric nanoparticles' properties and brain delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(12):2045. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13122045, PMID 34959326.

Verma K, Chaturvedi A, Paliwal S, Dwivedi J, Sharma S. Polymeric nanocarriers for the delivery of phytoconstituents. In: Pooja D, Kulhari H, editors. Nanotechnology-based delivery of phytoconstituents and cosmeceuticals. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. 2024. p. 89-123. doi: 10.1007/978-981-99-5314-1_4.

Sharma Y, Patel P, Kurmi BD. A mini-review on new developments in nanocarriers and polymers for ophthalmic drug delivery strategies. Curr Drug Deliv. 2024;21(4):488-508. doi: 10.2174/1567201820666230504115446, PMID 37143264.

Sunoqrot S, Abdel Gaber SA, Abujaber R, Al Majawleh M, Talhouni S. Lipid and polymer-based nanocarrier platforms for cancer vaccine delivery. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2024;7(8):4998-5019. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.3c00843, PMID 38236081.

Mesquita B, Singh A, Prats Masdeu CP, Lokhorst N, Hebels ER, Van Steenbergen M. Nanobody-mediated targeting of zinc phthalocyanine with polymer micelles as nanocarriers. Int J Pharm. 2024 Apr 25;655:124004. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.124004, PMID 38492899.

Idumah CI. Recently emerging advancements in polymeric nanogel nanoarchitectures for drug delivery applications. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater. 2024;73(2):104-16. doi: 10.1080/00914037.2022.2124256.

Pourmadadi M, Dehaghi HM, Ghaemi A, Maleki H, Yazdian F, Rahdar A. Polymeric nanoparticles as delivery vehicles for targeted delivery of chemotherapy drug fludarabine to treat hematological cancers. Inorg Chem Commun. 2024 Sep;167:112819. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112819.

Delgado Pujol EJ, Martinez G, Casado Jurado D, Vazquez J, Leon Barberena J, Rodriguez Lucena D. Hydrogels and nanogels: pioneering the future of advanced drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics. 2025;17(2):215. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics17020215, PMID 40006582.

Zhao Q, Zhang S, Wu F, Li D, Zhang X, Chen W. Rational design of nanogels for overcoming the biological barriers in various administration routes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2021;60(27):14760-78. doi: 10.1002/anie.201911048, PMID 31591803.

Yin Y, Hu B, Yuan X, Cai L, Gao H, Yang Q. Nanogel: A versatile nano delivery system for biomedical applications. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(3):290. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12030290, PMID 32210184.

Wu HQ, Wang CC. Biodegradable smart nanogels: a new platform for targeting drug delivery and biomedical diagnostics. Langmuir. 2016;32(25):6211-25. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b00842, PMID 27255455.

Vijayan VM, Vasudevan PN, Thomas V. Polymeric nanogels for theranostic applications: a mini review. Curr Nanosci. 2020;16(3):392-8. doi: 10.2174/1573413715666190717145040.

Rahdar A, Sayyadi K, Sayyadi J, Yaghobi Z. Nano gels: a versatile nano carrier platform for drug delivery systems: a mini review. Nanomed Res J. 2019;4(1):1-9.

Rigogliuso S, Sabatino MA, Adamo G, Grimaldi N, Dispenza C, Ghersi G. Polymeric nanogels: nanocarriers for drug delivery application. Chem Eng. 2012;27:247-52. doi: 10.3303/CET1227042.

Zhao K, Li D, Shi C, Ma X, Rong G, Kang H. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles as the delivery carrier for drug. Curr Drug Deliv. 2016;13(4):494-9. doi: 10.2174/156720181304160521004609, PMID 27230997.

Hans ML, Lowman AM. Biodegradable nanoparticles for drug delivery and targeting. Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci. 2002;6(4):319-27. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0286(02)00117-1.

Sundar DS, Antoniraj MG, Kumar CS, Mohapatra SS, Houreld NN, Ruckmani K. Recent trends of biocompatible and biodegradable nanoparticles in drug delivery: a review. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23(32):3730-51. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160607103854, PMID 27281132.

Rytting E, Nguyen J, Wang X, Kissel T. Biodegradable polymeric nanocarriers for pulmonary drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5(6):629-39. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.6.629, PMID 18532919.

Chamundeeswari M, Jeslin J, Verma ML. Nanocarriers for drug delivery applications. Environ Chem Lett. 2019;17(2):849-65. doi: 10.1007/s10311-018-00841-1.

Paul S, Hmar EB, Pathak H, Sharma HK. An overview on nanocarriers. In: Nanocarriers for drug targeting brain tumors. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2022. p. 145-204. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-90773-6.00004-X.

Drbohlavova J, Chomoucka J, Adam V, Ryvolova M, Eckschlager T, Hubalek J. Nanocarriers for anticancer drugs: new trends in nanomedicine. Curr Drug Metab. 2013;14(5):547-64. doi: 10.2174/1389200211314050005, PMID 23687925.

Preman NK, Jain S, Johnson RP. Smart polymer nanogels as pharmaceutical carriers: a versatile platform for programmed delivery and diagnostics. ACS Omega. 2021;6(8):5075-90. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c05276, PMID 33681548.

Li D, Van Nostrum CF, Mastrobattista E, Vermonden T, Hennink WE. Nanogels for intracellular delivery of biotherapeutics. J Control Release. 2017;259(259):16-28. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.12.020, PMID 28017888.

Nunes D, Andrade S, Ramalho MJ, Loureiro JA, Pereira MC. Polymeric nanoparticles loaded hydrogels for biomedical applications: a systematic review on in vivo findings. Polymers. 2022;14(5):1010. doi: 10.3390/polym14051010, PMID 35267833.

Li Y, Maciel D, Rodrigues J, Shi X, Tomas H. Biodegradable polymer nanogels for drug/nucleic acid delivery. Chem Rev. 2015;115(16):8564-608. doi: 10.1021/cr500131f, PMID 26259712.

Altuntas E, Ozkan B, Gungor S, Ozsoy Y. Biopolymer-based nanogel approach in drug delivery: basic concept and current developments. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(6):1644. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15061644, PMID 37376092.

Maddiboyina B, Desu PK, Vasam M, Challa VT, Surendra AV, Rao RS. An insight of nanogels as novel drug delivery system with potential hybrid nanogel applications. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2022;33(2):262-78. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2021.1982643, PMID 34547214.

Garg A, Shah K, singh Chauhan C, Agrawal R. Ingenious nanoscale medication delivery system: nanogel. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2024 Feb;92:105289. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2023.105289.

Sahu S, Telegaonkar S, Mishra M. Future prospects and challenges to central nervous system drug delivery; a shortcoming towards treatment of neurodegenerative disease. In: Novel drug delivery systems in the management of CNS disorders. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2025. p. 451-62. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-13474-6.00002-0.

Alwattar JK, Chouaib R, Khalil A, Mehanna MM. A novel multifaceted approach for wound healing: optimization and in vivo evaluation of spray dried tadalafil loaded pro-nanoliposomal powder. Int J Pharm. 2020 Sep 25;587:119647. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119647, PMID 32673771.

Poonia N, Jadhav NV, Mamatha D, Garg M, Kabra A, Bhatia A. Nanotechnology-assisted combination drug delivery: a progressive approach for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Ther Deliv. 2024;15(11):893-910. doi: 10.1080/20415990.2024.2394012, PMID 39268925.

Bhavsar N, Saxena B, Shah J. Blood-brain barrier and central nervous system drug delivery: challenges and opportunities. In: Nanocarriers for drug targeting brain tumors. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2022. p. 31-48. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-90773-6.00005-1.

Khatoon R, Alam MA, Sharma PK. Current approaches and prospective drug targeting to brain. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2021 Feb;61:102098. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.102098.

Jiao Y, Yang L, Wang R, Song G, Fu J, Wang J. Drug delivery across the blood brain barrier: a new strategy for the treatment of neurological diseases. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(12):1611. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16121611, PMID 39771589.

Scherrmann JM. Drug delivery to brain via the blood-brain barrier. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;38(6):349-54. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(02)00202-1, PMID 12529929.

Rytting E, Nguyen J, Wang X, Kissel T. Biodegradable polymeric nanocarriers for pulmonary drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5(6):629-39. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.6.629, PMID 18532919.

Sung JC, Pulliam BL, Edwards DA. Nanoparticles for drug delivery to the lungs. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25(12):563-70. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.09.005, PMID 17997181.

Menon JU, Ravikumar P, Pise A, Gyawali D, Hsia CC, Nguyen KT. Polymeric nanoparticles for pulmonary protein and DNA delivery. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(6):2643-52. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.01.033, PMID 24512977.

Suen CM, Mei SH, Kugathasan L, Stewart DJ. Targeted delivery of genes to endothelial cells and cell and gene-based therapy in pulmonary vascular diseases. Compr Physiol. 2013;3(4):1749-79. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120034, PMID 24265244.

Nichols SP, Storm WL, Koh A, Schoenfisch MH. Local delivery of nitric oxide: targeted delivery of therapeutics to bone and connective tissues. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64(12):1177-88. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.03.002, PMID 22433782.

Fahmy TM, Fong PM, Goyal A, Saltzman WM. Targeted for drug delivery. Mater Today. 2005;8(8):18-26. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(05)71033-6.