Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 5, 95-98Original Article

A STUDY OF THE EFFECT OF ORAL INGESTION OF SILVER FOIL ON LIPID FRACTIONS IN CHICKENS

MILI JAIN

Department of Biochemistry, JIET Medical College and Hospital, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

*Corresponding author: Mili Jain; *Email: drmilijain13@gmail.com

Received: 10 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 30 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Silver foil is widely used in Ayurvedic and Unani medicine for various therapeutic purposes, including cardiovascular health. Previous reports have suggested a hypolipidemic effect of silver. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of orally administered silver foil on lipid metabolism in young male chicks.

Methods: A total of 50 male chicks (approximately 1 kg body weight) were divided equally into control and experimental groups. The experimental group received 15 mg of silver foil mixed with ~1 g of mawa sweet once daily for 10 days. Controls were untreated. After the treatment period, all chicks were sacrificed, and blood samples were collected in heparinized vials. Plasma was separated and analysed for lipid fractions, including total lipids, phospholipids, triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, VLDL-cholesterol, and LDL-cholesterol. HDL-cholesterol to total cholesterol ratio was also calculated. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s paired t-test.

Results: Silver analysis revealed 99.5% purity in the foil. Silver levels in the blood and plasma of treated chicks were significantly higher, indicating systemic absorption (4.7 times in blood, 4.4 times in plasma). The experimental group showed significant reductions in total lipids, phospholipids, triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and VLDL-cholesterol, alongside a significant increase in HDL-cholesterol and HDL-C/TC ratio. No signs of toxicity were observed, and body weight increased during the study.

Conclusion: These findings suggest that oral ingestion of silver foil exerts a hypolipidemic effect, notably increasing HDL-cholesterol and reducing atherogenic lipid fractions. Silver foil may hold potential as a natural therapeutic agent for preventing or mitigating atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Silver foil, Lipids, Phospholipids, Triglycerides, Total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, VLDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol to total cholesterol ratio, Atherosclerosis, Cardiovascular health

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i5.7049 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

The increasing integration of metallic compounds in various sectors, including medicine, consumer goods, and food, has raised critical questions regarding their biological safety and systemic impact. Among these, silver has long been utilized for its antimicrobial properties, finding applications in medical dressings, utensils, and more recently, as nanoparticles in diagnostic and therapeutic agents [1].

In South Asian cultures, silver is also ingested intentionally, commonly as decorative foil (vark) in traditional sweets and Ayurvedic preparations. Despite this long-standing practice, the physiological implications of orally ingested silver, particularly in its macroscopic, foil form-remain insufficiently understood.

Although substantial research has addressed the toxicological profiles of silver nanoparticles, studies focusing on bulk or foil forms of silver are limited. The biological interactions of silver particles depend on their size, shape, surface area, as well as their solubility and cellular uptake. For silver particles, it has been shown that silver can induce oxidative stress, inflammation, and metabolic enzyme disruption, which can impact significant metabolic processes. Nevertheless, larger-sized silver particle foils used, such as in food decoration, may have different bioavailability and physiological behaviour that needs to be studied further.

Another primary important concern is how ingested silver interacts with lipid profiles comprising metabolites such as cholesterol, triglycerides, and phospholipids, which play a pivotal role in cellular activities, membrane structural integrity, and energy homeostasis [2].

Abnormalities in lipid profiles are known to contribute to atherosclerosis, cardiovascular diseases, and metabolic syndrome. Some studies suggest foreign substances, particularly metals, may alter the balance of lipids by modifying enzyme action, oxidative pathways, and inflammation [3].

Even though these practices do exist, it has not studied the oral metabolism of silver foil and its impact on lipid fractions that circulate within the body [4, 5]. This gap in knowledge stands out especially because of cultural traditions that accept silver ingestion. In this regard, this study aims to assess whether exposing subjects to silver foil would significantly alter the parameters of lipids in their blood, such as cholesterol levels, HDL-C (High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol), LDL-C (Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol), and triglycerides.

This research seeks to bridge the gap between cultural practices and modern toxicological science. This study addresses an important question with due regard for ethics and appropriate experimentation by determining what biological changes happen systemically due to silver-foil ingestion on lipid metabolism. Insights from such research could not only advance understanding of silver’s biological effects on metabolism but also contribute to evidence-based assessments of consumer safety. As silver continues to be consumed in various forms globally, a rigorous scientific evaluation of its systemic impact is both timely and essential.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted in the Department of Biochemistry at Bikaner Medical College. Chickens were selected as the experimental model given their easy availability from the local market, ease of handling, and the ability to obtain a sufficient volume of blood for subsequent biochemical assays. One-month-old male chicks of the same breed were used in the study. The chicks were divided into two groups: control and experimental, with 25 birds in each group. The body weight of the chicks in both groups was recorded before initiation of the experiment. The standard diet used was finisher mash, as recommended by North (1984). An oral dose of 15 mg of silver was administered daily to the experimental group in the form of silver foil incorporated into mawa. After 10 d of treatment, the chicks were kept overnight under fasting conditions before sacrifice. After that, blood samples were drawn from the jugular vein and placed in vials coated with anticoagulants. The plasma was subsequently separated by centrifugation, and various biochemical analyses - such as total lipids, phospholipids, triglycerides, and total cholesterol - were performed. Furthermore, ratios of HDL-cholesterol to total cholesterol, as well as VLDL and LDL fractions, were calculated.

Determination of silver concentration in both blood and plasma was performed following the Volhard-Arnold method using atomic absorption spectrophotometry. VLDL cholesterol was calculated from plasma samples as described by Vasudevan and Sreekumari (1999). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was calculated using the formula suggested by Vasudevan and Sreekumari (1999).

RESULTS

The results indicate that total lipids were considerably lower in the experimental group (437.0 ± 49.5 mg/dl) compared to the control group (518.8 ± 82.0 mg/dl), demonstrating a highly significant difference (*t = 4.2, **p<0.001). A similar trend was observed in phospholipids, which decreased from 217.0 ± 56.2 mg/dl in the control group to 189.3 ± 32.3 mg/dl in the experimental group (*t = 2.1, **p<0.05).

Table 1: Effect of experimental intervention on serum lipid fractions: comparative statistical analysis

| Lipid fraction | Control group | Experimental group | Anylasis | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | *t-test | **p-value | |

| Total Lipids (mg/dl) | 518.8 | 82 | 437 | 49.5 | 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Phospholipids (mg/dl) | 217 | 56.2 | 189.3 | 32.3 | 2.1 | <0.05 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 115.7 | 33.5 | 71.9 | 29.2 | 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 145.4 | 26.6 | 120.8 | 18.8 | 3.7 | <0.001 |

| HDL-Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 44.4 | 15 | 53.6 | 14 | 2.2 | <0.05 |

| HDL-Cholesterol*100/Total Cholesterol(mg/dl) | 31.4 | 12.3 | 45.4 | 14 | 3.7 | <0.001 |

| VLDL-Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 23.1 | 6.6 | 14.3 | 5.8 | 5 | <0.001 |

| LDL-Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 77.8 | 31.9 | 52.8 | 24.3 | 3.1 | <0.01 |

Triglyceride levels showed a substantial reduction in the experimental group (71.9 ± 29.2 mg/dl) in comparison with the control group (115.7 ± 33.5 mg/dl) (*t = 4.9, **p<0.001). Likewise, total cholesterol decreased markedly from 145.4 ± 26.6 mg/dl in the control group to 120.8 ± 18.8 mg/dl in the experimental group (*t = 3.7, **p<0.001).

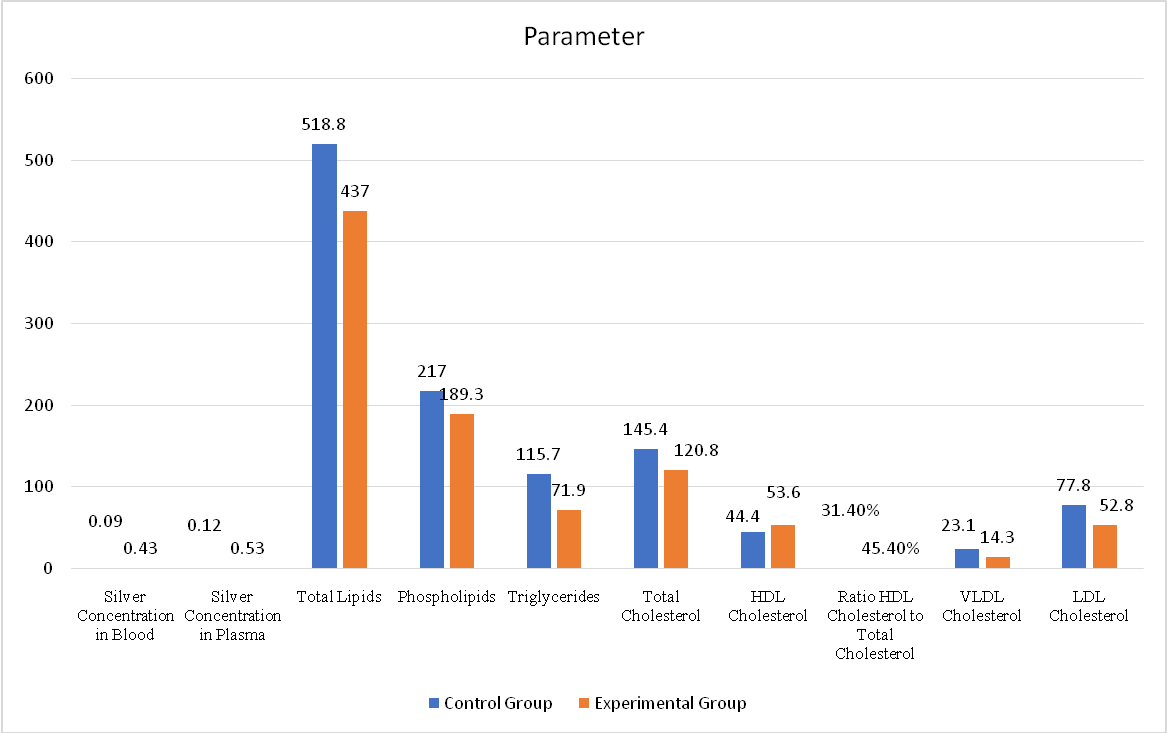

Fig. 1: Effect of orally administered silver foil on plasma lipid profile

Silver levels in blood and plasma were measured in µg/ml. Lipid parameters, including total lipids, phospholipids, triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and VLDL cholesterol, were recorded in mg/dl. The HDL-to-total cholesterol ratio was expressed as a percentage. The data represent mean values for both groups.

Interestingly, HDL-cholesterol increased significantly in the experimental group (53.6 ± 14.0 mg/dl) in comparison with the control group (44.4 ± 15.0 mg/dl) (*t = 2.2, **p<0.05). Correspondingly, the HDL-C to total cholesterol ratio was significantly elevated in the experimental group (45.4 ± 14.0%) compared to controls (31.4 ± 12.3%) (*t = 3.7, **p<0.001), indicating a more favourable lipid profile.

Both VLDL-cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol levels showed significant reductions following silver foil ingestion. VLDL-C decreased from 23.1 ± 6.6 mg/dl in the control group to 14.3 ± 5.8 mg/dl in the experimental group (*t = 5.0, **p<0.001), while LDL-C declined from 77.8 ± 31.9 mg/dl to 52.8 ± 24.3 mg/dl (*t = 3.1, **p<0.01).

DISCUSSION

The current research contributes to closing a significant gap in the literature, which largely omits the effects of silver administration on lipid profiles. The purity of the silver foil used in this study was 99.5%, and its dosage was standardized following Nadkarni et al. (1986). [6]

During the experiment, the chicks in the treatment group remained alert, healthy, and active, with no visible manifestation of toxicity. The initial average body weight of the chicks was 0.977±0.166 kg before the start of the study and subsequently increased to 1.069±0.181 kg by its conclusion. This upward trend in body weight further suggests that the administration of silver leaf did not produce any deleterious effects. Comparable results were previously published by Khanna et al. (1997) [7], who did not observe any adverse effects after adding a 1% silver preparation to the diet of rats for two months. However, Hill et al. (1964) documented growth retardation in chicks at 100 ppm, with progressively severe effects, including depression and reduced activity, upon increasing the silver concentration to 200 ppm [8].

Absorption of silver by the chicks during the experiment was further demonstrated by the 4.4-fold rise in plasma silver and 4.7-fold rise in whole blood silver concentrations. As shown in table 1, silver quantity was considerably higher in the experimental group than in the control group, affirming that silver was absorbed following its administration.

The greater rise in whole blood silver levels as compared to plasma in the silver-treated group, in contrast to their respective controls, stands in opposition to the observations made by Choudhary (2001) in the case of copper bhasma and by Jha (1999) and Sharma et al. (2001) in the case of gold, where plasma was found to show greater distribution than whole blood or erythrocytes [9-11].

As presented in table 1, silver foil administration led to a statistically significant decrease in lipid fractions, except for high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, which was considerably increased in the experimental group. The total lipid concentration was significantly lower in the experimental group of chicks in comparison to the control group (*p<0.001). Similar effects were observed for phospholipids, which fell to 87.2% of control values following the intervention, reflecting a 12.7% reduction (*p<0.05) as shown in table 1.

Additionally, silver leaf administration resulted in a marked 37.8% reduction in triglyceride levels in the experimental group of chicks when contrasted with controls (*p<0.001). Thus, the ability of silver to lower triglyceride and lipid fractions while increasing HDL may be considered a desirable metabolic profile in reducing atherogenic risk. (Besser and Thorner, 1994) [12].

The control group of chicks presented a plasma total cholesterol level of 145.4±26.6 mg%, while the experimental group, after administration of silver foil for 10 d, demonstrated a significantly lower plasma total cholesterol level of 120.8±18.8 mg% (*p<0.001) (fig. 1). This corresponds to a 16.9% reduction in total cholesterol, with the average plasma cholesterol in the experimental group representing 83.0% of the control group’s value.

The reduction in total cholesterol by any therapeutic agent is considered beneficial for the regression of atherosclerosis, as demonstrated by numerous animal and human studies (Faggioto et al., 1984; Clarkson, 1984) [13, 14].

The mechanisms by which silver reduces plasma lipid levels, especially cholesterol and triglycerides, remain unclear. Because silver belongs to the heavy metal group, it may be speculated that it inhibits enzyme systems involved in the biosynthesis of cholesterol and other lipids. This view is supported by a study by Konjufca et al. (1997), [15] who found that copper supplementation (63–180 mg/kg) in the form of cupric citrate or cupric sulfate for 21 d resulted in reduced plasma, liver, and thigh muscle cholesterol, alongside a decline in fatty acid synthetase and cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase activity. Furthermore, silver, like copper, belongs to the same group in the periodic table (fig. 1) (Sharma, 1999), implying that it may produce similar effects by inhibiting these key enzyme mechanisms [16].

In contrast to the reductions observed in other lipid fractions, a statistically significant (*p<0.05) increase in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol was recorded in the silver-treated chicks. The average HDL cholesterol rose by 20.7% in the experimental group than in the control group. A rising level of HDL cholesterol is a desirable metabolic profile, as higher HDL is linked with a reduced possibility of atherosclerosis (Ramakrishnan, 1995) [17].

The ratio of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol to total cholesterol serves as an index of atherosclerotic risk, with higher ratios reflecting a more favourable profile (table 1). Ideally, the HDL cholesterol to total cholesterol ratio should be high, while total cholesterol should be kept at a minimum, thereby reducing the atherogenic potential.

In the present study, we observed a highly significant (*p<0.001) increase in the HDL cholesterol to total cholesterol ratio in the experimental group of chicks after administration of silver foil (fig. 1). The average increase was 44.5% in contrast with the control group, additionally implying a reduced atherosclerotic risk in the silver-treated chicks.

A substantial decrease in VLDL cholesterol was recorded in the experimental group following silver administration (*p<0.001) (fig. 1). The average VLDL cholesterol in the experimental group was 61.9% of that in the control group, reflecting a 38% reduction. VLDL particles are predominantly formed in the liver from triglycerides, which are themselves derived from circulating free fatty acids or from de novo lipogenesis. VLDL cholesterol largely originates from the delivery of cholesterol within chylomicron remnants (Besser and Thorner, 1994) [12].

Our data (table 1) show a critical (*p<0.01) reduction in LDL cholesterol following silver foil administration (fig. 1). The average LDL cholesterol in the experimental group was 67.8% of that in the control group, representing a 32.1% drop. Elevated plasma LDL is a well-established atherosclerotic risk factor. (Besser and Thorner, 1994) [12].

Findings of our study collectively indicate a beneficial role for silver foil in mitigating the atherosclerotic process.

As chicks are very rarely used as laboratory models, normal plasma lipid values for this species are not frequently documented in the literature. To enable comparison, a thorough search of available data was performed.

CONCLUSION

The age-old practice of consuming silver leaf with betel and sweets (typically rich in lipids) or drinking water from silver glasses may have a sound scientific basis. The absorption of microquantities of silver may contribute to maintaining plasma lipid levels within normal range and, in turn, may aid in retarding the progression of atherosclerosis.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed equally

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Foldbjerg R, Dang DA, Autrup H, Kjems J, Ornsbo L. Cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human lung cells. J Nanopart Res. 2009;11(7):1645-58.

Prabhu S, Poulose EK. The effect of nanosilver on oxidative stress in rat liver and kidney. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:3903-10.

Shah S, Sharma M, Pathak N, Garg BS. Impact of silver nanoparticles on lipid metabolism in rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2013;76(6):335-45.

Chen X, Schluesener HJ. Nanosilver: a review of nanosilver safety and toxicity. Arch Toxicol. 2011;85(11):1269-81.

Sharma M, Singh J, Sharma R, Singh SP. Oxidative stress and genotoxicity induced by silver nanoparticles in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2009;28(2):223-8.

Nadkarni AK. Indian materia medica. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Bombay: Popular Press Prakashan; 1986. p. 14-5.

Khanna AT, Sivaraman R, Vohora SB. Analgesic activity of silver preparations used in Indian systems of medicine. Indian J Pharmacol. 1997;29:393-8.

Hill CH, Starcher B, Matrone G. Mercury and silver interrelationships with copper. J Nutr. 1964;83:107-10. doi: 10.1093/jn/83.2.107, PMID 14167698.

Choudhary P. Effect of ingestion of copper bhasma on circulating lipids and cardiac enzymes. Jaipur: University of Rajasthan; 2001. p. 80.

Kayahan S. Cholesterol binding capacity of normal and atherosclerotic intimas. Lancet. 1959;1(7066):223-4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(59)90051-0, PMID 13631974.

Sharma DC, Jha J, Sharma P, Gaur BL. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of a gold-containing ayurvedic drug. Indian J Exp Biol. 2001;39(9):892-6. PMID 11831371.

Besser GM, Thorner MO. Clinical endocrinology. 2nd ed. London: M Wolfe; 1994. p. 6.2-6.18.

Faggiotto A, Ross R, Harker L. Studies of hypercholesterolemia in the nonhuman primate. I. Changes that lead to fatty streak formation. Arteriosclerosis. 1984;4(4):323-40. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.4.4.323, PMID 6466191.

Clarkson TB, Bond MG, Bullock BC. A study on atherosclerosis regression in Macaca mulatta. V. changes in abdominal aorta and carotid and coronary arteries from animals with atherosclerosis induced for 38 m and then regressed for 24 or 48 m at plasma cholesterol concentrations of 300 or 200 mg/dl. Exp Mol Pathol. 1984;41(1):41-96. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(84)90011-x.

Konjufca VH, Pesti GM, Bakalli RI. Modulation of cholesterol levels in broiler meat by dietary garlic and copper. Poult Sci. 1997;76(9):1264-71. doi: 10.1093/ps/76.9.1264, PMID 9276889.

Sharma DC. Textbook of biochemistry. Hyderabad: Paras Medical Publisher; 1999. p. 223.

Ramakrishnan S, Swami R. Textbook of clinical (medical) biochemistry and immunology; 1995. p. 67-76.