Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 5, 109-117Original Article

THERAPEUTIC EVALUATION OF MICHELIA CHAMPACA ON NOISE-INDUCED HEPATORENAL ALTERATIONS IN RATS

MALATHI S.1, DINESH KUMAR2, VIDYASHREE3, RAVINDRAN RAJAN4*

1Department of Physiology, Vels Medical College and Hospital, Manjakaranai, Chennai, India. 2Department of Anatomy, PSP Medical College Hospital and Research Institute, Chennai, India. 3Department of Physiology, Dr Chandramma Dayananda Sagar Institute of Medical Education and Research, India. 4Department of Physiology, Dr. ALM PG Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Madras, Chennai-600113, Tamil Nadu, India

*Corresponding author: Ravindran Rajan; *Email: ravindran89@gmail.com

Received: 11 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 01 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The present study aimed to investigate the hepatoprotective and nephroprotective potential of Michelia champaca methanolic extract in male wistar rats subjected to noise-induced stress.

Methods: Rats were exposed to noise stress at 100 dB for 4 h daily, for both acute (1 d) and chronic (30 d) durations. Liver function enzymes (AST, ALT, ALP), renal biomarkers (urea, creatinine), DNA fragmentation analysis, and histopathological evaluations were performed to assess organ damage and protective effects.

Results: Chronic noise exposure led to a significant (p<0.05) increase in hepatic and renal biomarkers [AST, ALP, ALT, Creatinine, urea], indicating liver and kidney dysfunction. Additionally, DNA fragmentation revealed genotoxic stress in exposed animals. Administration of M. champaca extract (400 mg/kg body weight) markedly (p<0.05) attenuated these biochemical and molecular alterations in both acute and chronic exposure groups.

Conclusion: The findings suggest that liver and kidney tissues are particularly vulnerable to noise-induced oxidative and genotoxic stress. Treatment with M. champaca extract conferred significant protective effects, likely due to its phytochemical constituents. Further studies are needed to elucidate its molecular mechanisms and potential clinical applications.

Keywords: M. champaca, Liver enzymes, AST, ALP, ALT, Kidney creatinine, Urea, Noise stress

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i5.7069 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Noise pollution has emerged as a significant global concern in today's increasingly industrialized and urbanized world. It is recognized as a major environmental stressor, contributing to a wide range of psychological and physiological health issues [1, 2]. While low levels of environmental noise are generally not considered a substantial health risk, prolonged or repeated exposure to high-intensity noise-typically above 90 dB-can have serious adverse health effects [3]. Chronic noise exposure has been linked to elevated stress responses, leading to systemic physiological disturbances [4].

One of the key mechanisms by which noise exerts its harmful effects is through the generation of free radicals [5]. The oxidative stress induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS) harms auditory cells and extends its detrimental effects to other organs, including the liver and kidneys. Oxidative stress caused by prolonged noise exposure can disrupt cellular homeostasis, increase lipid peroxidation, and heighten the risk of developing chronic diseases such as cancer and metabolic disorders [6].

The liver, a vital organ responsible for detoxification, protein synthesis, and metabolic regulation, is particularly vulnerable to oxidative injury [7]. Hepatocytes, the functional cells of the liver, play a crucial role in various biochemical pathways and are sensitive to damage from hepatotoxic agents, including ROS [8]. Experimental studies have demonstrated that exposure to high-frequency noise can induce pathological changes in liver tissues [9]. Compromising hepatic function.

Similarly, the kidneys are susceptible to noise-induced damage. Several studies have shown that chronic noise exposure is associated with psychosocial stress, which can contribute to hypertension and metabolic syndromes such as type 2 diabetes [10-13]. These conditions, in turn, exacerbate renal deterioration. Mechanistically, noise-induced stress activates the sympathetic nervous system, leading to renal hemodynamic alterations, including increased renal vascular resistance and reduced blood flow [14, 15]. Animal studies have observed elevated sympathetic nerve activity in response to noise, correlating with impaired renal perfusion and function. Such findings suggest a potential link between environmental stressors like noise and chronic kidney disease (CKD) of unknown origin [16].

Epidemiological data support this association. Zhang et al. [17] reported a positive correlation between noise exposure and CKD prevalence, while Kim et al. [18] found that noise significantly affects kidney function, particularly in women. Given the scarcity of effective pharmaceutical options to prevent or reverse liver and kidney damage caused by environmental stressors, there is growing interest in alternative therapies such as those found in Ayurvedic medicine.

One such medicinal plant is M. champacacommonly known as Swarna Champa. It is rich in antioxidants, particularly flavonoids, and has been traditionally used for its therapeutic effects on the central nervous system. Scientific studies have highlighted its anti-inflammatory [19], antimicrobial [20], anti-leishmanial [21], antidiabetic [22], and cardioprotective properties [23], and it is also used for kidney diseases [24]. Additionally, a sesquiterpene lactone known as parthenolide-recognized for its anticancer activity [20]-has been isolated from its bark. Other beneficial compounds, such as essential oils, alkaloids, and beta-sitosterol, have also been identified in various parts of the plant.

Despite its wide array of pharmacological properties, limited research has been conducted on the protective effects of M. champaca against noise-induced stress, particularly concerning hepatic and renal damage. Considering the growing prevalence of noise-related health issues, including younger populations, and the lack of comprehensive studies on the metabolic impact of noise stress, it becomes essential to explore potential protective agents.

This study explores the effects of noise pollution on liver and kidney health by assessing serum levels of hepatic enzymes and renal biomarkers in rats exposed to different intensities of noise stress with a particular emphasis on the potential protective role of M. champaca.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Wistar rats, weighing between 200–250g, were selected for the study and housed in cages (size: 40 × 40 × 20 cm) under controlled conditions of temperature (23±2 °C), humidity (50±5%), and a 12 h light/dark cycle. They had free access to food and water ad libitum. The care and handling of the animals adhered to the guidelines set by the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Government of India. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (Approval No: 01/23/2015).

Flower collection and preparation of extracts

Flowers of M. champacawere sourced from local markets in Chennai and identified by Dr. D. Aravind, Department of Medicinal Botany. A voucher specimen was deposited at the Herbarium of the National Institute of Siddha, with the reference number NIS/MB/94/2013. After collection, the flowers were cleaned, dried in the shade at room temperature, and then ground before extraction.

Methanol extracts

Ten gs of dried M. champaca flowers were immersed in 100 ml of methanol (twice, i. e., 2x100 ml) for 8-10 d at room temperature in the dark, with stirring every 18 h using a sterile rod. The extract was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper, concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure at 40 °C using a rotary evaporator, and stored at 4 °C for subsequent use. An oral dose of 400 mg/kg body weight was administered to the animals in this study.

Experimental groups

The rats were divided into six groups, with six rats in each group: saline control, acute noise stress, chronic noise stress (1 day and 30 d, respectively), M. champaca treatment alone (30 d), and noise stress (acute and chronic) combined with M. champaca treatment (30 d).

Induction of noise stress

Noise stress was induced using a white noise generator (0-26 kHz), amplified by a 40W amplifier and transmitted through two 15W loudspeakers placed 30 cm above the animal cages. The sound intensity was measured using a Quest Electronics Cygnet Systems D2023 sound level meter (serial No. F02199, India), and maintained at 100 dBA. The rats were exposed to this noise for 4 h daily. Control animals were placed in identical conditions, but were not exposed to the noise, to rule out the influence of handling stress [25].

Biochemical estimation

Blood samples were collected from the retroorbital plexus, and serum was separated by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The serum was then analyzed for various biochemical parameters, including aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT) was measured by Rietman and Frankel [26]; alkaline phosphatase (ALP) by King and King Method [27]; urea by the Natelsonmethod [28] and creatinine levels by the Brod and sinota method [29].

Histopathological studies

Liver and kidney tissue samples were collected, fixed in 10% formalin, formalin-fixed samples were dehydrated in ascending grades of ethanol, cleared in methyl benzoate and embedded in paraffin wax, sections were cut at 5µm thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin [30] and examined under a photomicroscope.

RESULTS

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS for Windows statistical software (version 20.0, SPSS Inc., Cary, North Carolina). The significance between groups was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison tests, with a significance level set at P<0.05.

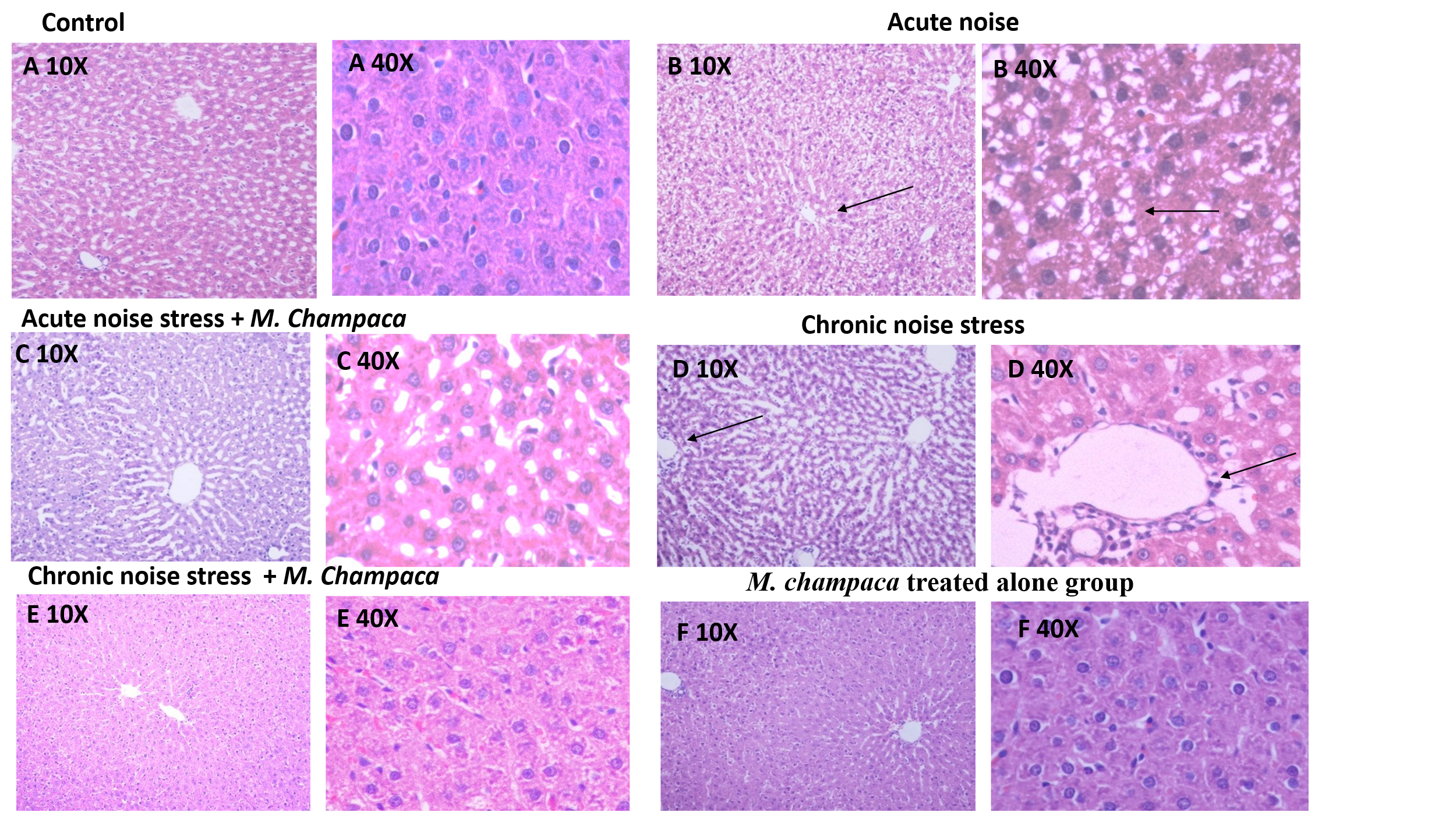

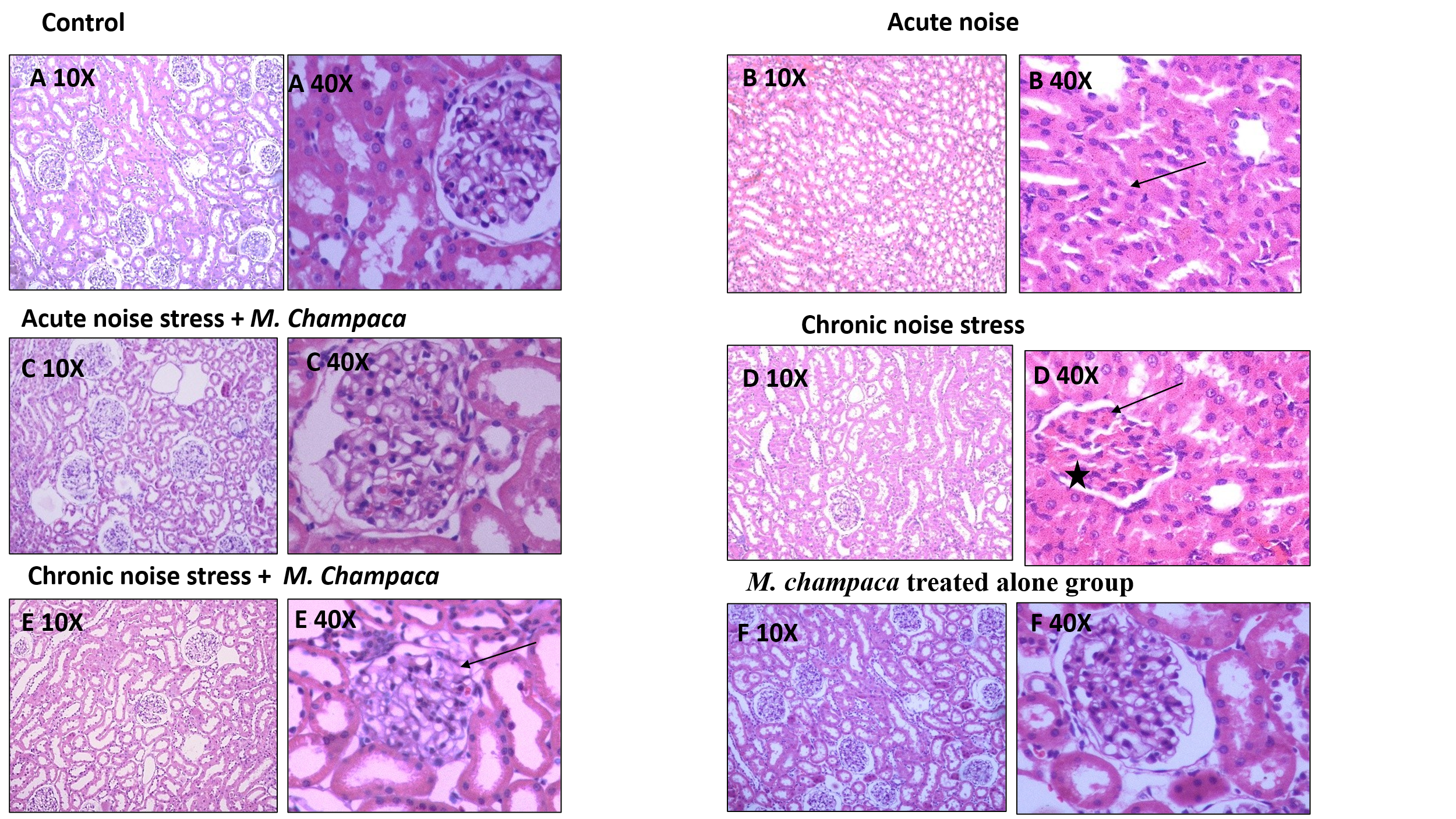

Fig. 1: Illustrates H and E-stained liver cells of rat’s in different experimental groups at 10X and 40X magnification. (A) Control, (B) Acute noise stress alone, (C) Acute noise stress+M. champaca, (D) Chronic noise stress, (E) Chronic noise stress+M. champaca, (F) M. champaca treated alone group

Chronic noise stress exposure group shown central vein and hepatic sinus congestion, as well as devasted hepatic lobule in liver tissue, dilated congested portal vein and sinusoidal spaces, and vacuolated hepatocytes with pyknotic nuclei. Highly affected endothelial lining of blood vessels of the liver tissue (fig. 1D). Whereas these changes were mild in acute stress group (fig. 1B). All these changes were reversed in noise group treated with M. champaca (fig. 1C and E) Drug treatment group showed no detectable histological changes in liver tissues.

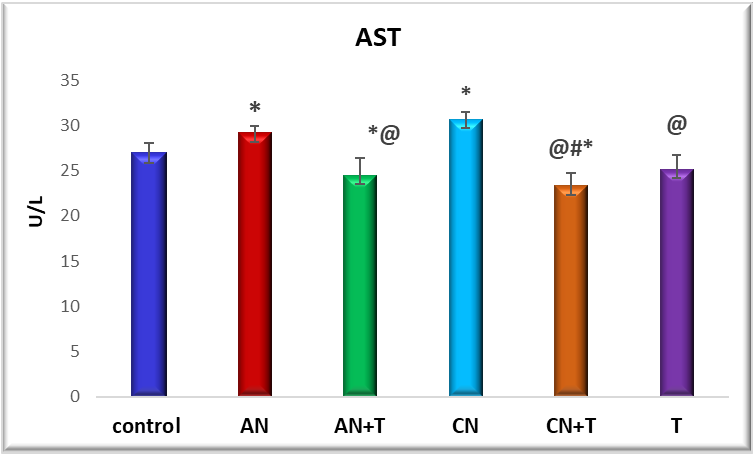

Fig. 2: Effect of noise stress and methanolic extract of M. Champaca on AST: value are expressed as mean±SD, N=6. The symbols represent statistical significance: *@#$<P 0.05. *-Compared with saline control, @-Compared with acute noise, #-compared with chronic noise. $-Acute noise compared with chronic noise

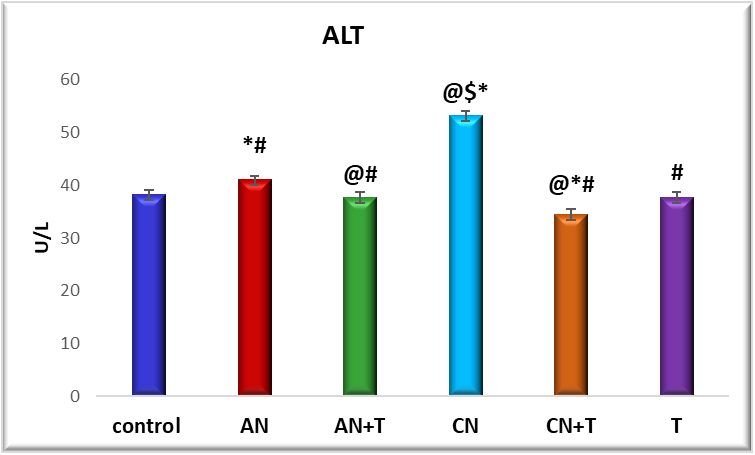

Fig. 3: Effect of noise stress and methanolic extract of M. Champaca on ALT: values are expressed as mean±SD, N=6. The symbols represent statistical significance: *@#$<P 0.05. *-Compared with saline control, @-Compared with acute noise, #-compared with chronic noise. $-Acute noise compared with chronic noise

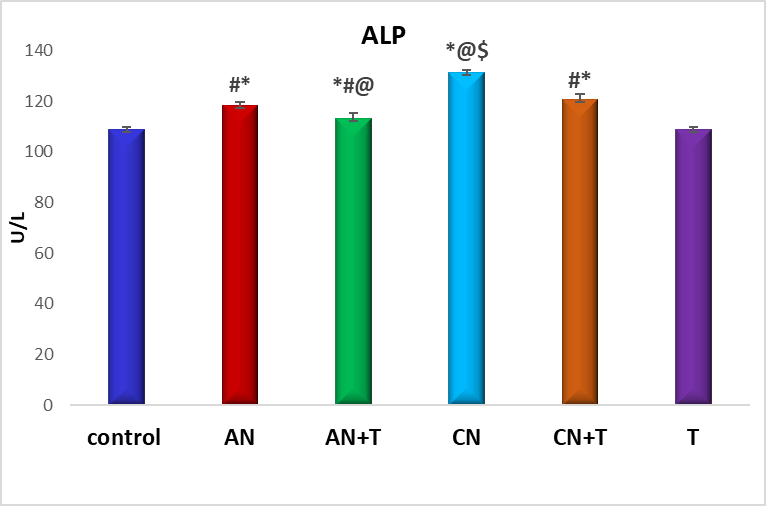

Fig. 4: Effect of noise stress and methanolic extract of M. Champaca on ALP, values are expressed as mean±SD, N=6. The symbols represent statistical significance: *@#$<P 0.05. *-Compared with saline control, @-Compared with acute noise, #-compared with chronic noise. $-Acute noise compared with chronic noise

Effect of methanolic extract of M. champaca on renal markers in noise stress induced rats

The effect of methanolic extract of M. champaca on liver markers ALT, AST, and ALP is summarized in fig. 2,3 and 4. There was a significant (P<0.05) increase in serum ALP, AST, ALT levels in acute and chronic noise stress group (fig. 2, 3, and 4) when compared to control. The methanolic extract of flowers of M. champaca treatments on noise stress group reversed the level of all the liver enzymes. no statistical changes were distinguished in rats treated with M. champaca flower extract group alone compared to that of control.

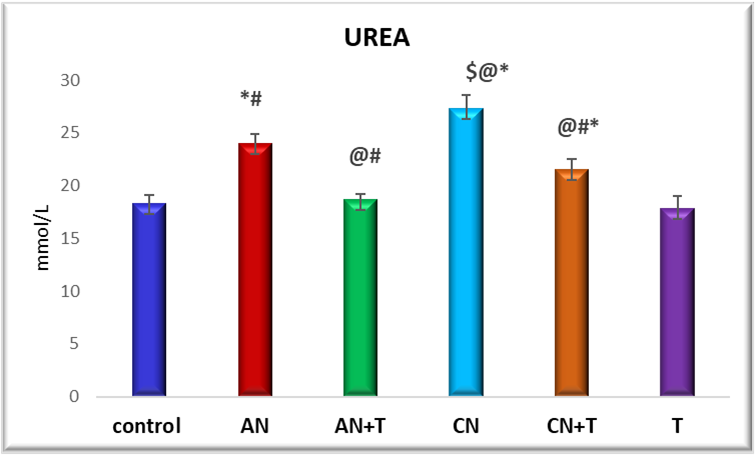

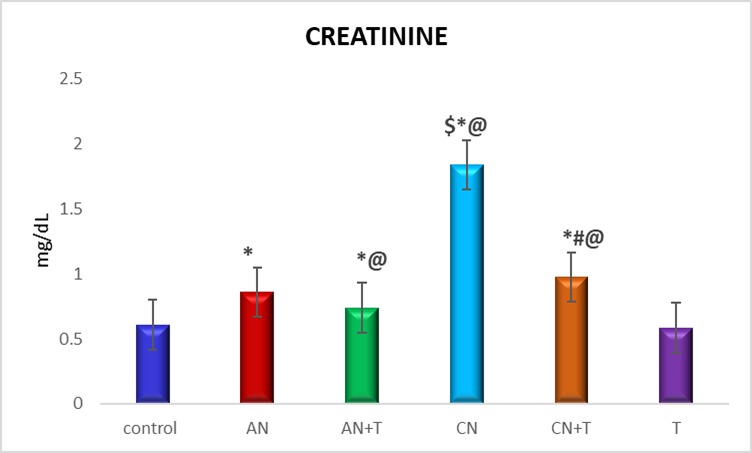

Fig. 5: Effect of noise stress and methanolic extract of M. Champaca on serum urea, values are expressed as mean±SD, N=6. The symbols represent statistical significance: *@#$<P 0.05. *-Compared with saline control, @-Compared with acute noise, #-compared with chronic noise. $-Acute noise compared with chronic noise

Fig. 6: Effect of noise stress and methanolic extract of M. Champaca on serum creatinine, values are expressed as mean±SD, N=6. The symbols represent statistical significance: *@#$<P 0.05. *-Compared with saline control, @-Compared with acute noise, #-compared with chronic noise. $-Acute noise compared with chronic noise

The effect of methanolic extract of M. champacaon renal markers urea and creatinine is summarized in fig. 5 and 6 There was a significant (P<0.05) increase level of urea and creatinine in acute and chronic noise stress group when compared to control. More changes were observed in chronic stress group when compared to acute stress group. The methanolic extract of flowers of M. champaca treatments on noise stress group reversed the level of all the renal markers no statistical changes were distinguished in rats treated with M. champaca flower extract alone group compared to that of control.

B-40X acute noise stress group shows flattened epithelium (arrow) and vacuolated cytoplasm D-40X chronic noise stress group shows mild congestion and lymphoid cell aggregation (star) in the interstitium and necrotic area (arrow) and faintly stained cells and nuclei, ruptured brush borders, and thickened arterial wall.

Exposure of rats to noise showed dystrophic changes in kidney when compared to other groups which include atrophied glomerulus, faintly stained cells and nuclei, ruptured brush borders, and thickened arterial wall and mild congestion and lymphoid cell aggregation in the interstitium and necrotic area Changes were seen in chronic noise group (fig. 7D) when compared to acute noise stress group. Kidneys of noise+drug group showed (both acute and chronic) normal appearance.

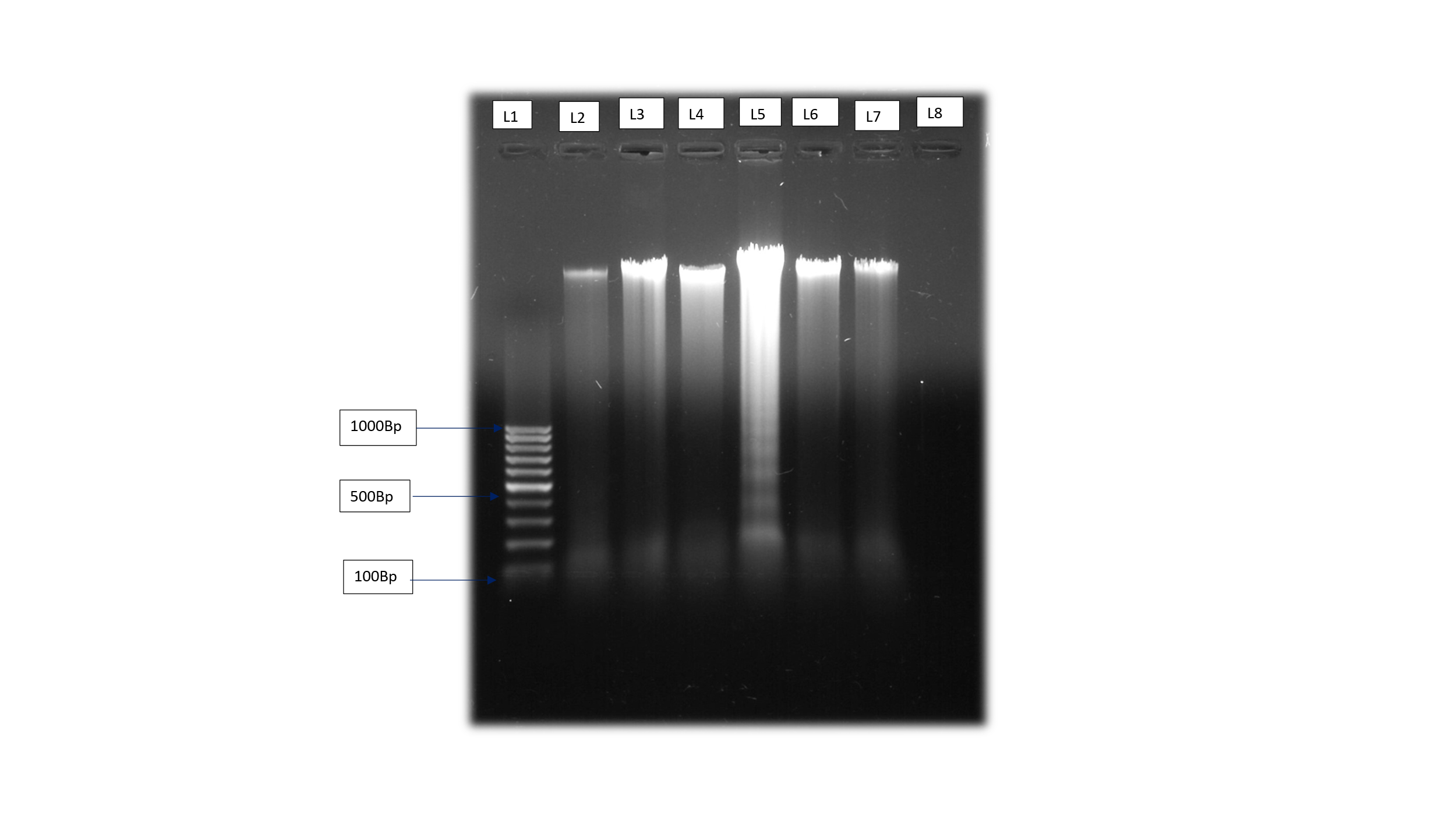

Effect of noise stress on DNA damage of liver

The impact of both acute and chronic noise stress on hepatic DNA integrity was assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis. As shown in fig. 8, no significant DNA fragmentation was observed in the control group, the acute noise stress group treated with M. champaca and the treatment-only group, indicating preserved DNA integrity in these conditions.

In contrast, liver tissues from animals exposed to chronic noise stress exhibited clear DNA fragmentation, (Fig; 8 lane 5) a hallmark of genotoxic damage. This suggests that prolonged noise exposure leads to significant DNA damage in hepatic cells. Notably, animals in the chronic noise stress group that received M. champaca treatment showed a marked reduction in DNA fragmentation, indicating that the plant extract may confer protective effects against noise-induced genotoxicity.

These findings highlight the potential of M. champaca as a protective agent against chronic noise-induced DNA damage in liver tissues.

Fig. 7: Illustrates H and E-stained kidney tissue in different experimental group at 10X and 40X magnification

Fig. 8: Effect of M. champacaon DNA fragmentation in liver of noise-exposed adult wistar rats

DISCUSSION

The impact of noise stress on biological systems involves modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which can alter the functioning of various organs. As a result, indirect effects are observed in liver and kidney function [31]. Prolonged exposure to noise stress increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), disrupting the redox balance within tissues and cells and shifting it toward a more oxidizing environment.

Oxidative stress resulting from excessive ROS generation can impair various cellular structures including lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, DNA, and membranes. This results in tissue damage, particularly affecting the liver and kidneys [32].

The liver, during the detoxification of xenobiotics and other toxic substances, generates substantial amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Oxidative stress resulting from excessive ROS production has been strongly associated with liver disorders, including steatosis and various other pathological conditions [33].

These effects are supported by histopathological evidence (fig. 1) and are accompanied by elevated levels of liver enzymes-AST (aspartate aminotransferase), ALT (alanine transaminase), ALP (alkaline phosphatase) (fig. 2-4)-accompanied by a rise in blood urea and creatinine levels (fig. 5 and 6).

The effects of noise stress on liver function are multifaceted and can vary depending on the intensity and duration of exposure, as well as individual susceptibility. Our findings show that liver enzyme alterations correlate with the severity and duration of noise exposure. Rats subjected to chronic noiseexposureexhibited significantly greater changes (P<0.05) than those exposedacutely (fig. 2-4) possibly as a result of intensified neuroendocrine or autonomic stress responses. This suggests that noise stress can alter liver metabolic activity and enzyme levels, as supported by Blumenthal et al. [34].

After 30 d of noise exposure, a significant rise in serum ALT, AST, ALP, urea, and creatinine levels was observed in adult male Wistar rats. This may result from the release of these enzymes from damaged hepatocytes into circulation [35]. Nayanatara et al. [36] also reported elevated AST and ALT levels in rats exposed to chronic environmental stressors, linking these changes to cellular damage, necrosis, and increased membrane permeability. Similar findings were noted in our chronic stress group.

ALT is considered a more sensitive marker for acute liver damage compared to AST, as it is primarily associated with liver parenchyma. Histological examination of liver tissues from chronically stressed rats revealed increased lymphocytes and Kupffer cells in the portal areas, dilated and congested portal veins and sinusoids, and vacuolated hepatocytes with pyknotic nuclei. These findings were more prominent in the chronic stress group than in the acute group. Kupffer cells, known to release cytokines and inflammatory mediators in response to sympathetic activation, contribute to hepatocellular damage and necrosis [37]. Notably, these changes were alleviated in the chronic noise group treated with M. champaca.

Fatma et al. [38] proposed that stress-related liver damage is primarily due to altered hepatic blood flow, with emotional stress inducing vasospasms and centrilobular hypoxia. Filip et al. [39] also observed significant damage to the liver’s vascular endothelium following prolonged stress. Chida et al. [40] supported this view, suggesting that stress-induced vasospasm and hypoxia can cause hepatic injury.

Studies revealed that Histological examination of four weeks of noise exposure led to increased collagen deposition in the liver, while two weeks of exposure caused central vein and sinusoidal congestion, along with hepatocyte destruction due to inflammatory cell infiltration.

Chronic noise stress exposure group showed central vein and hepatic sinus congestion, as well as devasted hepatic lobule in liver tissue, dilated congested portal vein and sinusoidal spaces, and vacuolated hepatocytes with pyknotic nuclei. Highly affected endothelial lining of blood vessels of the liver tissue (fig. 1D). Whereas these changes were mild in acute stress group (fig. 1B). All these changes were reversed in noise group treated with M. champaca (fig. 1C and E) Drug treatment group showed no detectable histological changes in liver tissues.

These structural changes may result from enhanced lipid peroxidation and reduced antioxidant enzyme activity, (These parameters were studied and published separately) leading to cellular membrane damage [41].

The current study observed a significant increase (p<0.05) in serum creatinine levels in both acute and chronic noise-exposed rats, (fig. 6) with a more pronounced increase noted in the chronic exposure group. Elevated levels of urea and creatinine indicate impaired kidney function, as the kidneys are less able to filter and excrete metabolic waste products effectively. According to Matsumoto et al. [42], increased serum creatinine may result from enhanced catabolism in muscle and tissues, leading to its elevated synthesis.

In cases of acute stress, rapid activation of the HPA axis leads to sudden physiological changes. However, prolonged exposure to noise stress interferes with creatinine metabolism and is associated with decreased renal transaminase activity [43], which may explain the more significant alterations seen in the chronic exposure group. Moreover, excessive noise stress can trigger apoptotic signalling pathways, resulting in cell death.

Excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been implicated in the progression of renal diseases, including nephrotic syndrome [44]. Hence assessing the level of oxidative stress is vital for the early prediction and understanding of nephrotic syndrome pathogenesis. In vitro studies have highlighted the pivotal role of oxidative stress in the development of NS [45]. ROS-induced redox reactions can lead to protein carboxylation, DNA damage, and disruption of the cytoskeleton. These oxidative injuries compromise glomerular protein permeability and disrupt the structural integrity of tubular epithelial cells, ultimately contributing to the onset of nephrotic syndrome [46].

In the kidneys, stress-induced oxidative damage resulted in several degenerative changes, as seen in our chronic noise-exposed group. Compared to the acute group, which showed minimal histological changes, chronic exposure led to brush border destruction, tubular cell vacuolization, and vascular congestion (fig. 7D). Treatment with M. champaca reduced these effects (fig. 7C and E). Kidney cortices from control animals and those treated with the drug showed a normal distribution of collagen fibers.

Previous studies have shown that even two weeks of exposure to 100 dB noise causes renal congestion and cell disorganization [47] while one-year exposure to 87 dB led to lipidosis and swelling in renal tissues of Wistar rats [48].

Chronic noise exposure in both prepubertal and adult animals resulted in glomerular loss, altered corticomedullary ratio, and decreased kidney volume-changes indicative of reduced nephron count due to damage. Similar renal alterations have been observed in turtles subjected to chronic vibration stress, including distorted podocyte structure, vacuolation, and loss of normal tubule architecture [48].

According to Zhang et al. [49] increased collagen deposition facilitates tissue healing and the formation of new blood vessels. In our study, collagen accumulation persisted in the cortex of treated rats exposed to chronic noise, suggesting ongoing repair and remodellingall these changes are observed in the chronic noise stress group treated with M. Champaca (fig. 7E) mainly methanolic extract contain compounds like epicatechin and resveratrol.

Resveratrol (3,5,4'-trihydroxystilbene) is a naturally occurring polyphenolic compound known for its broad range of protective effects against oxidative stress, inflammation, diabetes, obesity, and cognitive dysfunction. It exhibits potent antioxidant activity, safeguarding vital organs such as the liver, kidneys, and brain from oxidative damage [50].

The mechanisms underlying resveratrol’s antioxidant effects include direct scavenging of free radicals, suppression of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and the upregulation of endogenous antioxidant enzymes like SOD, GSH and CAT [51, 52].

Numerous studies have confirmed the hepatoprotective potential of resveratrol, largely attributed to its ability to reduce oxidative stress and inhibit apoptosis [53, 54]. In experimental models involving cadmium exposure and high-fat diet-induced liver damage, resveratrol significantly attenuated hepatotoxicity and oxidative injury [55-58]. Additionally, in heat stress models, resveratrol preserved hepatic structure and function, highlighting its protective role under environmental and physiological stress.

Resveratrol has also been shown to mitigate liver damage caused by ischemia-reperfusion injury through multiple mechanisms. These include the inhibition of lipid peroxidation, enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, CAT, and glutathione peroxidase), reduction in aminotransferase levels, suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and improvement in vascular function [59]. These multifaceted effects form the basis of its therapeutic potential in liver transplantation settings [60, 61].

Further supporting its hepatoprotective role, Kirimlioglu et al. [62] demonstrated that resveratrol administration in rats undergoing partial hepatectomy resulted in decreased lipid peroxidation and nitric oxide (NO) levels, alongside increased GSH content. These findings reinforce the compound’s robust antioxidant and cytoprotective capabilities.

Epicatechin (EPI), a flavanol well-recognized for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties, has garnered attention for its Reno protective, hepatoprotective, and cardioprotective potential [63]. Several studies have demonstrated that epicatechin enhances hepatic glutathione (GSH) levels, reduces elevated malondialdehyde (MDA) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), and restores glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity, particularly in monocrotaline (MCT)-treated animal models [64, 65]. Both in vivo and in vitro research further confirms that epicatechin mitigates cisplatin-induced cellular injury by preserving mitochondrial protein content, maintaining structural integrity, and preventing functional impairments-effects that are especially pronounced in renal tubular epithelial cells [66].

Notably, epicatechin also exerts therapeutic effects in models of established nephropathy. In cisplatin-induced kidney injury in mice, EPI has demonstrated the ability to preserve mitochondrial function and structural integrity, even when administered after the onset of tubular damage. This highlights its potential as a post-injury therapeutic agent.

Polyphenols, particularly flavonoids such as epicatechin, are among the most powerful plant-derived antioxidants. These compounds act as efficient free radical scavengers, neutralizing harmful oxidative species before they inflict cellular damage. Moreover, polyphenols can form complexes with reactive metals like iron, zinc, and copper, modulating their absorption and limiting toxicity due to excess accumulation [67]. This antioxidant potential is evident in our study where chronic noise exposure group treated with M. champaca-a plant rich in polyphenols, flavonoids, and other phytochemicals-ameliorated oxidative stress-induced damage.

Noise exposure is known to act as a DNA stressor, inducing oxidative DNA damage and DNA strand breaks in various cells and organs. Previous studies have shown that noise exposure can cause DNA damage in auditory and non-auditory organs, including the cochlear sensory cells, auditory nerves [68, 69] cortex [70, 71], brainstem [72], heart and liver [69, 73].

Our findings indicate that chronic noise stress caused significantly DNA damage in liver tissue (fig. 8) compared to acute noise stress. DNA is a primary target for oxidative stress, leading to lipid peroxidation and protein damage [74]. The observed changes are likely due to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and free radicals, resulting in altered tissue architecture, as evident in the histopathology of the liver. In contrast, the acute noise stress group showed mild changes, while the acute noise stress group treated with M. Champaca and the control group showed protective effects against noise stress-induced DNA damage.

Similar studies have reported protective effects of natural compounds against noise stress-induced damage. For example, Indigofera tinctoria and Scoparia dulcis aqueous extracts, rich in flavonoids, prevented DNA damage and abnormal tissue architecture in Wistar albino rats exposed to chronic noise stress. Another study by Sultana et al. [75] found that chrysin, a phytochemical compound rich in flavonoids, attenuated cisplatin-induced toxicity and prevented severe DNA damage in Wistar rats.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrates that liver and kidney tissues are particularly susceptible to disorders induced by noise stress. The methanolic extract of M. champaca exhibits significant hepatoprotective and nephroprotective activity, safeguarding these organs in rats subjected to noise-induced stress. The presence of rich phytochemical constituents namely epicatechin and resveratrol in M. champaca may contribute to its therapeutic potential in treating liver and kidney disorders. Further molecular studies are needed to elucidate the exact mechanism of action and explore the clinical applications of M. champaca.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

First author – Dr. Malathi. S – experiments and manuscript preparation and formulation of experimental design.

Second author Dr. Dinesh Kumar – Histology work-tissue processing and staining of liver and kidney.

Third author-Dr. Vidyashree H. M– Manuscript edition and formulation of experimental design.

Corresponding and forth author-Dr. Ravindran Rajan – formulation of experimental design and approved.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Karlidag T, Yalcin S, Ozturk A, Ustundag B, Gok U, Kaygusuz I. The role of free oxygen radicals in noise induced hearing loss: effects of melatonin and methylprednisolone. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2002;29(2):147-52. doi: 10.1016/S0385-8146(01)00137-7.

Ohinata Y, Yamasoba T, Schacht J, Miller JM. Glutathione limits noise induced hearing loss. Hear Res. 2000;146(1-2):28-34. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(00)00096-4.

Ravindran R, Devi RS, Samson J, Senthilvelan M. Noise stress induced brain neurotransmitter changes and the effect of Ocimum sanctum (linn) treatment in Albino rats. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;98(4):354-60. doi: 10.1254/jphs.FP0050127.

Mc Ewen BS. Stress and the individual: mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(18):2093-101. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1993.00410180039004.

Manikandan S, Srikumar R, Jeya Parthasarathy NJ, Devi RS. Protective effect of Acorus calamus linn on free radical scavengers and lipid peroxidation in discrete regions of brain against noise stress exposed rat. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28(12):2327-30. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.2327.

Munzel T, Sorensen M, Schmidt F, Schmidt E, Steven S, Kroller Schon S. The adverse effects of environmental noise exposure on oxidative stress and cardiovascular risk. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2018;28(9):873-908. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7118.

Ananthi T, Anuradha R. Hepatoprotective activity of Michelia champaca L. against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatic injury in rats. J Chem Pharm Res. 2015;7(9):270-4.

Chattopadhyay RR. Possible mechanism of hepatoprotective activity of Azadirachta indica leaf extract: part II. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;89(2-3):217-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.08.006.

Xue L, Zhang D, Yibulayin X, Wang T, Shou X. Effects of high frequency noise on female rats multi-organ histology. Noise Health. 2014;16(71):213-7. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.137048.

Bedi M, Varshney VP, Babbar R. Role of cardiovascular reactivity to mental stress in predicting future hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2000;22(1):1-22. doi: 10.1081/CEH-100100058.

Engum A. The role of depression and anxiety in onset of diabetes in a large population based study. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(1):31-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.07.009.

Raikkonen K, Matthews KA, Kuller LH. Depressive symptoms and stressful life events predict metabolic syndrome among middle aged women. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):872-7. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1857.

Novak M, Bjorck L, Giang KW, Heden Stahl C, Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A. Perceived stress and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a 35 y follow-up study of middle aged Swedish men. Diabet Med. 2013;30(1):e8-16. doi: 10.1111/dme.12037.

Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1238-52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32064-5.

Carter JR, Goldstein DS. Sympathoneural and adrenomedullary responses to mental stress. Compr Physiol. 2015;5(1):119-46. doi: 10.1002/j.2040-4603.2015.tb00608.x.

Kannenkeril D, Jung S, Ott C, Striepe K, Kolwelter J, Schmieder RE. Association of noise annoyance with measured renal hemodynamic changes. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2021;46(3):323-30. doi: 10.1159/000515527.

Zhang Y, Liu Y, Li Z, Liu X, Chen Q, Qin J. Effects of coexposure to noise and mixture of toluene ethylbenzene xylene and styrene (TEXS) on hearing loss in petrochemical workers of southern China. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30(11):31620-30. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-24414-6.

Kim YJ, Choi WJ, Ham S, Kang SK, Lee W. Association between occupational or environmental noise exposure and renal function among middle aged and older Korean adults: a cross sectional study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):24127. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03647-4.

Vimala R, Nagarajan S, Alam M, Susan T, Joy S. Anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activity of Michelia champaca Linn. Ixora brachiataRoxb and Rhynchosiacana (Willed.) DC flower extract. Indian J Exp Biol. 1997 Dec;35(12):1310-4. PMID 9567766.

Wei LS, Wee W, Siong JY, Syamsumir DF. Characterization of antimicrobial antioxidant anticancer property and chemical composition of Michelia champaca seed and flower extracts. Stamford Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011;4(1):19-24. doi: 10.3329/sjps.v4i1.8862.

Takahashi M, Fuchino H, Satake M, Agatsuma Y, Sekita S. In vitro screening of leishmanicidal activity in myanmar timber extracts. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27(6):921-5. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.921.

Jarald E, Joshi SB, Jain DC. Antidiabetic activity of flower buds of Michelia champaca Linn. Indian J Pharmacol. 2008;40(6):256-60. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.45151.

Rajshree S, Ranjana V. Michelia champaca L. (Swarna champa) a review. Int J Enhanc Res Sci Tech Eng. 2016;5(8):78-82.

Soltan ME, Sirry SM. Usefulness of some plant flowers as natural acid base indicators. J Chinese Chemical Soc. 2002;49(1):63-8. doi: 10.1002/jccs.200200011.

Samson J, Sheela Devi R, Ravindran R, Senthilvelan M. Effect of noise stress on free radical scavenging enzymes in brain. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;20(1):142-8. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2004.12.059.

Reitman S, Frankel S. A colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1975;28(1):56-63. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/28.1.56.

King EJ, Abul Fadl MA, Walker PG. King armstrong phosphatase estimation by the determination of liberated phosphate. J Clin Pathol. 1951;4(1):85-91. doi: 10.1136/jcp.4.1.85.

Natelson S, Scott ML, Beffa C. A rapid method for the estimation of urea in biologic fluids by means of the reaction between diacetyl and urea get access arrow. Am J Clin Pathol. 1951;21(3_ts):275-81. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/21.3_ts.275.

Brod J, Sirota JH. The renal clearance of endogenous creatinine in man. J Clin Invest. 1948;27(5):645-54. doi: 10.1172/JCI102012.

Bancroft JD, Gamble M. Theory and practice of histological techniques. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008.

Chirica R, Comsa GI, Ion I, Adumitresi C, Radulescu N, Farcas C. Indirect effects of noise exposure on liver activity. ARS Med Tomitana. 2013;19(2):103-6. doi: 10.2478/arsm-2013-0018.

Ising H, Braun C. Acute and chronic endocrine effect of noise review of the research conducted at the institute for water soil and air hygiene. Noise Health. 2000;2(7):7-24. PMID 12689468.

Stohs SJ. The role of free radicals in toxicity and disease. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;6(3-4):205-28. doi: 10.1515/JBCPP.1995.6.3-4.205.

Blumenthal M, Busse WR, Goldberg A. Therapeutic guide to herbal medicines the complete commission monographs. Med. 2000:80-1.

Mazia D, Brewer PA, Alfert M. The cytochemical staining and measurement of protein with mercuric bromophenol blue. The Biological Bulletin. 1953;104(1):57-67. doi: 10.2307/1538691.

Nayanatara AK, Nagaraja HS, Ramaswamy C, Bhagyalakshmi K, Ramesh Bhat M, Gowda D, KM, Venkappa S Mantur. Effect of chronic unpredictable stressors on some selected lipids parameters and biochemical parameters in Wistar rats. J Chin Clin Med. 2009;4(2):92-7.

Dawei W, Yimei Y, Yongming Y. Advances in sepsis associated liver dysfunction. Burns Trauma. 2014;2(3):97-105. doi: 10.4103/2321-3868.132689.

Fatma ED, Eman GH, Neama MT. Effect of crowding stress and or sulpirid treatment on some physiological and histological parameters in female albino rats. Egy J Hos Med. 2010;41(1):566-89. doi: 10.21608/ejhm.2010.16955.

Braet F, Shleper M, Paizi M, Brodsky S, Kopeiko N, Resnick N. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell modulation upon resection and shear stress in vitro. Comp Hepatol. 2004;3(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-3-7.

Chida Y, Sudo N, Kubo C. Does stress exacerbate liver diseases? J of Gastro and Hepatol. 2006;21(1):202-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04110.x.

Li S, Tan HY, Wang N, Zhang ZJ, Lao L, Wong CW. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in liver diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(11):26087-124. doi: 10.3390/ijms161125942.

Matsumoto S, Hanai H, Matsuura H, Akiyama Y. Creatol an oxidative product of creatinine in kidney transplant patients as a useful determination of renal function: a preliminary study. Transp Proce. 2006;38(7):2009-11. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.06.104.

Cybulsky AV. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in proteinuric kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2010;77(3):187-93. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.389.

Parmar GS, Mistry KN, Gang S. Correlation of serum albumin and creatinine with oxidative stress markers in patients having nephrotic syndrome. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2021;13(12):20-4. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2021v13i12.42931.

Vega Warner V, Ransom RF, Vincent AM, Brosius FC, Smoyer WE. Induction of antioxidant enzymes in murine podocytes precedes injury by puromycin aminonucleoside. Kidney Int. 2004;66(5):1881-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00962.x.

Kamireddy R, Kavuri S, Devi S, Vemula H, Chandana D, Harinarayanan S. Oxidative stress in pediatric nephrotic syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;325(1-2):147-50. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(02)00294-2.

Abouee Mehrizi A, Rasoulzadeh Y, Mesgari Abbasi M, Mehdipour A, Ebrahimi Kalan A. Nephrotoxic effects caused by co-exposure to noise and toluene in new zealand white rabbits: a biochemical and histopathological study. Life Sci. 2020 Oct 15;259:118254. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118254.

Zymantiene J, Zelvyte R, Pampariene I, Aniuliene A, Juodziukyniene N, Kantautaite J. Effects of long term construction noise on health of adult female Wistar rats. Pol J Vet Sci. 2017;20(1):155-65. doi: 10.1515/pjvs-2017-0020.

Zhang D, Xu Z, Chiang A, Lu D, Zeng Q. Effect of GSM1800 MHz radio frequency EMF on DNA damage in Chinese hamuster lung cells. Zhonghuo Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2006;36(3):183-6.

Nallagouni CSR, Mesram N, Karnati PR. Amelioration of aluminum and fluoride induced behavioural alterations through resveratrol in rats. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11(1):289-93. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i1.21620.

Carrizzo A, Forte M, Damato A, Trimarco V, Salzano F, Bartolo M. Antioxidant effects of resveratrol in cardiovascular cerebral and metabolic diseases. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013 Nov;61:215-26. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.07.021.

De Oliveira MR, Chenet AL, Duarte AR, Scaini G, Quevedo J. Molecular mechanisms underlying the anti-depressant effects of resveratrol: a review. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(6):4543-59. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0680-6.

Faghihzadeh F, Hekmatdoost A, Adibi P. Resveratrol and liver: a systematic review. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20(8):797-810. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.168405.

Vairappan B, Sundhar M, Srinivas BH. Resveratrol restores neuronal tight junction proteins through correction of ammonia and inflammation in CCl4-induced cirrhotic mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(7):4718-29. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1389-x.

Fernandez Quintela A, Milton Laskibar I, Gonzalez M, Portillo MP. Antiobesity effects of resveratrol: which tissues are involved? Ann NY Acad Sci. 2017;1403(1):118-31. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13413.

Wang P, Gao J, Ke W, Wang J, Li D, Liu R. Resveratrol reduces obesity in high fat diet fed mice via modulating the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;156:83-98. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.04.013.

Xu L, Wang R, Liu H, Wang J, Mang J, Xu Z. Resveratrol treatment is associated with lipid regulation and inhibition of lipoprotein associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) in rabbits fed a high fat diet. Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2020;2020(1):964-1582. doi: 10.1155/2020/9641582.

Cheng K, Song Z, Zhang H, Li S, Wang C, Zhang L. The therapeutic effects of resveratrol on hepatic steatosis in high fat diet induced obese mice by improving oxidative stress inflammation and lipid related gene transcriptional expression. Med Mol Morphol. 2019;52(4):187-97. doi: 10.1007/s00795-019-00216-7.

Yu S, Zhou X, Xiang H, Wang S, Cui Z, Zhou J. Resveratrol reduced liver damage after liver resection in a rat model by upregulating sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and inhibiting the acetylation of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:3212-20. doi: 10.12659/MSM.913937.

Gedik E, Girgin S, Ozturk H, Obay BD, Ozturk H, Buyukbayram H. Resveratrol attenuates oxidative stress and histological alterations induced by liver ischemia/reperfusion in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(46):7101-6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7101.

Hassan Khabbar S, Vamy M, Cottart CH, Wendum D, Vibert F, Savouret JF. Protective effect of post ischemic treatment with trans resveratrol on cytokine production and neutrophil recruitment by rat liver. Biochimie. 2010;92(4):405-10. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.12.009.

Kirimlioglu H, Ecevit A, Yilmaz S, Kirimlioglu V, Karabulut AB. Effect of resveratrol and melatonin on oxidative stress enzymes regeneration and hepatocyte ultrastructure in rats subjected to 70% partial hepatectomy. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(1):285-9. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.11.050.

Diniprastyowati S. Renoprotective potential offlavonoids rich against doxorubicin induce din animal models: a review. Int J Appl Pharm. 2024;16(6):28-37. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2024v16i6.51741.

Purohit P, Mahesh Kumarkataria. Phytochemicals screening antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of Carica papaya leaf extracts. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2024;16(3):95-8. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2024v16i3.4087.

Kaspar JW, Niture SK, Jaiswal AK. Nrf2:INrf2 (Keap1) signaling in oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47(9):1304-9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.035.

Tanabe K, Tamura Y, Lanaspa MA, Miyazaki M, Suzuki N, Sato W. Epicatechin limits renal injury by mitochondrial protection in cisplatin nephropathy. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2012;303(9):F1264-74. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00227.2012.

Ara N, Nur H. In vitro antioxidant methanolic leaves and flowers extracts of Lippia alba. Res J Med Sci. 2009;4(1):107-10.

Guthrie OW. Noise induced DNA damage within the auditory nerve. Anat Rec. 2017;300(3):520-6. doi: 10.1002/ar.23494.

Van Campen LE, Murphy WJ, Franks JR, Mathias PI, Toraason MA. Oxidative DNA damage is associated with intense noise exposure in the rat. Hear Res. 2002;164(1-2):29-38. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(01)00391-4.

Saljo A, Bao F, Jingshan S, Hamberger A, Hansson HA, Haglid KG. Exposure to short lasting impulse noise causes neuronal c-jun expression and induction of apoptosis in the adult rat brain. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19(8):985-91. doi: 10.1089/089771502320317131.

Frenzilli G, Ryskalin L, Ferrucci M, Cantafora E, Chelazzi S, Giorgi FS. Loud noise exposure produces DNA, neurotransmitter and morphological damage within specific brain areas. Front Neuroanat. 2017 Jun 26;11:49. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2017.00049.

Aarnisalo AA, Pirvola U, Liang XQ, Miller J, Ylikoski J. Apoptosis in auditory brainstem neurons after a severe noise trauma of the organ of Corti: intracochlear GDNF treatment reduces the number of apoptotic cells. ORL. 2000;62(6):330-4. doi: 10.1159/000027764.

Lenzi P, Frenzilli G, Gesi M, Ferrucci M, Lazzeri G, Fornai F. DNA damage associated with ultrastructural alterations in rat myocardium after loud noise exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(4):467-71. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5847.

Schraufstatter IU, Hinshaw DB, Hyslop PA, Spragg RG, Cochrane CG. Oxidant injury of cells. DNA strand breaks activate polyadenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase and lead to depletion of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. J Clin Invest. 1986;77(4):1312-20. doi: 10.1172/JCI112436.

Sultana S, Verma K, Khan R. Nephroprotective efficacy of chrysin against cisplatin induced toxicity via attenuation of oxidative stress. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;64(6):872-81. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01470.x.