Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 5, 124-128Original Article

PRESCRIPTION AUDIT IN OUTPATIENT DEPARTMENTS OF A SUPERSPECIALITY HOSPITAL IN NORTH-EASTERN INDIA

MUKUNDAM BORAH, ATIFA AHMED*, PRAN PRATIM SAIKIA, SWOPNA PHUKAN, MUKHLESUR RAHMAN

Department of Pharmacology, Gauhati Medical College and Hospital, Guwahati, Assam, India

*Corresponding author: Atifa Ahmed; *Email: a_atifa@yahoo.com

Received: 12 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 03 Aug 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: The study was conducted to evaluate prescribing patterns, assess adherence to standard treatment guidelines, and identify areas for improvement in prescription practices across superspeciality OPDs of a tertiary care hospital in Northeast India.

Methods: A cross-sectional prescription audit study was conducted over a 3-month period in the superspeciality OPDs of a tertiary care hospital in Northeast India. A total of 600 prescriptions were systematically sampled and analysed using WHO/INRUD prescribing indicators. Statistical analysis was performed using descriptive statistics and appropriate analytical tests.

Results: The present study demonstrates that the OPD registration number, date of consultation, and patient gender were consistently recorded in all prescriptions (100%), but complete patient names missing in 1.2% of prescriptions. The handwritings on 11% of prescriptions were not legible. 78.9% of prescriptions included a record of the salient features of the clinical examination, and just 75.1% mentioned a presumptive or definitive diagnosis. The average number of drugs per prescription was 5.39, indicating a trend towards polypharmacy. 88% of drugs were prescribed by their generic names. Antibiotics were prescribed in 12% of encounters. Drugs used by parenteral route were approximately 5% and percentage of drugs prescribed from EDL (Essential Drug List) is 82%. A notable finding was that only 72% of the prescribed medicines were available in the hospital dispensary.

Conclusion: The study shows excellent documentation of basic prescription elements and the generic prescribing rates are also commendable. But the trend of polypharmacy and inadequate drug availability require urgent attention.

Keywords: Prescription audit, Drug utilization, Superspeciality OPDs, Irrational prescriptions

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i5.7071 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Prescription auditing represents a critical quality assurance mechanism in modern healthcare systems, serving as an essential tool for evaluating prescribing practices and ensuring rational drug use [1]. To investigate drug use in health facilities, the WHO has recommended core prescribing indicators that encompass parameters such as average number of drugs per encounter, percentage of drugs prescribed by generic name, percentage of encounters with antibiotics and injections, and percentage of drugs prescribed from essential drug lists [2]. Inappropriate use of medicine has become an important issue worldwide, with the WHO estimating that more than 50% of medicines are prescribed, dispensed or sold irrationally, and about half of the patients fail to take them correctly [3]. The consequences of inappropriate prescribing extend beyond individual patient safety to encompass broader public health concerns, including antimicrobial resistance, increased healthcare costs, and suboptimal therapeutic outcomes. Studies have indicated that majority of prescriptions in developing countries are of drugs of "doubtful efficacy," highlighting the urgent need for systematic evaluation of prescribing practices [4].

Tertiary care hospitals in India face unique challenges in maintaining rational prescribing practices due to complex patient presentations, diverse specialty departments, and high patient volumes. The north-eastern region of India presents distinctive healthcare challenges, including geographical isolation, limited healthcare infrastructure, and diverse ethnic populations with varying disease patterns. Tertiary care hospitals in this region serve as referral centres for a vast catchment area, handling complex cases that require careful medication management. Despite their critical role, there is a paucity of prescription audit studies specifically conducted in north-eastern Indian tertiary care settings, creating a significant knowledge gap in understanding regional prescribing patterns and their compliance with WHO standards. Regular monitoring of WHO indicators enables healthcare institutions to identify prescribing deficiencies and implement targeted interventions for quality improvement [5].

This study aims to conduct a comprehensive prescription audit in the Superspeciality departments of a tertiary care hospital in northeast India, utilizing WHO core prescribing indicators to evaluate current prescribing practices, identify areas of concern, and provide evidence-based recommendations for enhancing rational drug use. The findings will contribute valuable insights into regional prescribing patterns and support the development of institution-specific strategies for optimizing pharmaceutical care quality in the northeastern Indian healthcare context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional, observational study was conducted at a Superspeciality hospital in Northeast India over a three-month period from April 2025 to June 2025. The hospital is a tertiary care referral centre with multiple super-specialty departments, including Cardiology, Neurology, Neurosurgery, Gastroenterology, Urology, Nephrology, Endocrinology, Cardiothoracic surgery and Paediatric Surgery. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee prior to data collection.

Study population and sampling

Sample size calculation

A total of 600 prescriptions were analyzed during the study period. The sample size was calculated based on the WHO recommendation for prescription audit studies, which suggests a minimum of 600 prescriptions for reliable assessment of prescribing patterns in healthcare facilities [7]. This sample size provides adequate power (80%) to detect clinically significant differences in prescribing indicators with a confidence interval of 95%.

Sampling strategy

To ensure homogeneous representation across all Superspeciality departments, stratified random sampling was employed. The total sample of 600 prescriptions was proportionally distributed among the eight Superspeciality departments based on their patient load during the study period. The distribution was as follows:

Cardiology: 90 prescriptions (%)

Neurology: 80 prescriptions (%)

Gastroenterology: 80 prescriptions (%)

Nephrology: 75 prescriptions (%)

Endocrinology: 70 prescriptions (%)

Paediatric surgery: 45 prescriptions (%)

Neurosurgery: 40 prescriptions (%)

Cardiothoracic Surgery: 40 prescriptions (%)

Urology: 80 (%)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

All prescriptions issued by qualified specialists in the Superspeciality departments

Prescriptions containing at least one medication

Exclusion criteria

Prescriptions containing only diagnostic procedures or investigations

Repeat prescriptions for the same patient within the study period

Data collection

Data collection tool

A structured data collection form was developed based on WHO core drug use indicators and validated through pilot testing on 30 prescriptions. The WHO/INRUD prescribing indicators were used to assess medication prescribing patterns. These included the average number of drugs prescribed per encounter, the percentage of drugs prescribed by generic name, the percentage of antibiotics prescribed, the percentage of injections prescribed, and the percentage of drugs prescribed from the Essential Drugs List (EDL). Patient-care indicators were employed specifically in relation to the average consultation time, the average dispensing time and the percentage of drugs dispensed. The study tool included health facility indicators, such as the presence of the Essential Medicines List (EML) or hospital formulary copy, and the percentage of key drug availability. These indicators were used to evaluate the level of hospital support in promoting rational drug use.

Patient demographics considered were age, gender, department of consultation and date of prescription. The following prescription details were recorded:

Clinical examination record/Diagnosis

Documentation of allergy/pregnancy/lactation status

Total number of drugs prescribed

Generic vs. brand-name prescribing

Antibiotic prescriptions

Injection prescriptions

Drugs from National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM) 2022

Dosage forms and strengths

Prescriber details and qualifications

Data collection process

Prescriptions were collected systematically from each department on predetermined days throughout the three-month period to avoid temporal bias. A random number generator was used to select prescriptions from the daily prescription pool in each department.

Data management and quality assurance

All data were entered into a pre-designed Microsoft Excel spreadsheet with built-in validation checks to minimize data entry errors. Double data entry was performed for 10% of prescriptions to assess data quality. The database was password-protected and access was restricted to authorized personnel only.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Results were presented in tabular and graphical formats to facilitate interpretation.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained before initiating the study. Patient confidentiality was maintained throughout the study period by de-identifying all prescription data. No personal identifiers were recorded, and all data were handled according to institutional data protection policies.

RESULTS

Study population and prescription characteristics

During the study period, a total of 600 prescriptions were systematically examined from nine different outpatient departments (OPDs) of the Superspeciality Hospital, Gauhati Medical College and Hospital. The prescriptions demonstrated varying levels of completeness and adherence to standard prescribing practices.

Documentation quality and completeness

Essential administrative information showed excellent compliance rates. OPD registration numbers, consultation dates, and patient gender were consistently documented in all prescriptions (100%, n=600). However, gaps in patient identification were identified, with complete patient names missing in 1.2% of prescriptions. A significant concern was the legibility of prescriptions, with 11% demonstrating illegible handwriting that could potentially compromise patient safety.

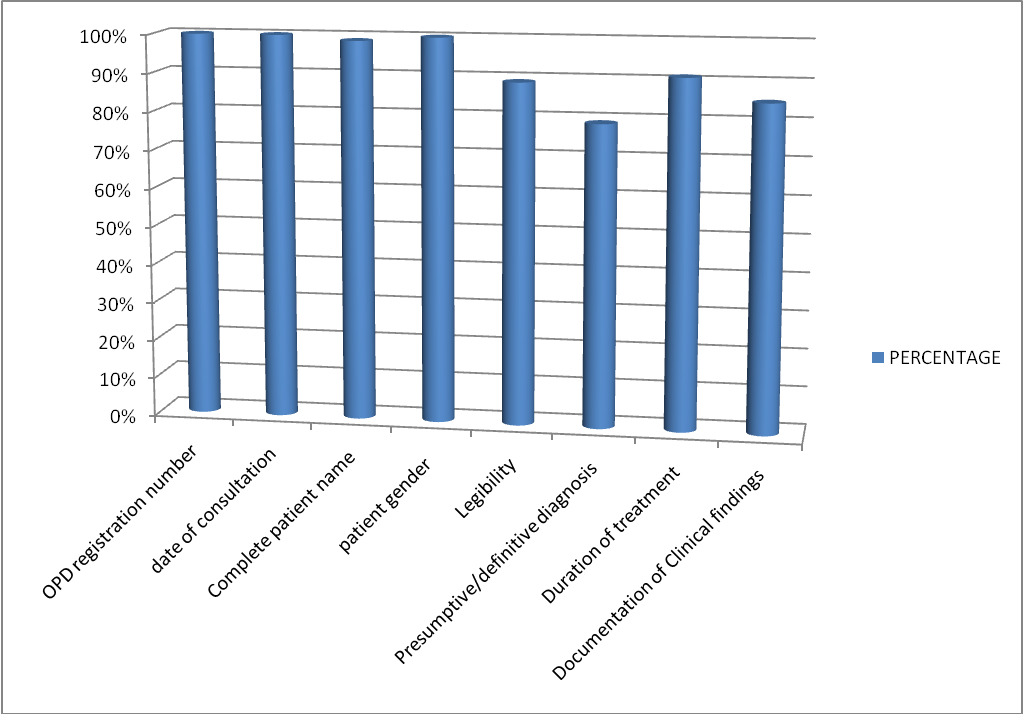

Clinical documentation revealed substantial variation in recording practices. Salient features of clinical examination were documented in 78.5% (n=471) of prescriptions, while presumptive or definitive diagnoses were recorded in 85% (n=510) of cases. Treatment duration was specified in 91% (n=546) of prescriptions, indicating generally good adherence to temporal treatment guidelines. These findings are depicted graphically in fig. 1.

Prescribing patterns and drug utilization

The analysis revealed a concerning trend toward polypharmacy, with an average of 5.39 drugs per prescription (range: 1-8 drugs). Generic prescribing showed encouraging adherence, with 88% prescribed using generic names. Antibiotic prescribing was appropriately conservative at 12% of total drug encounters.

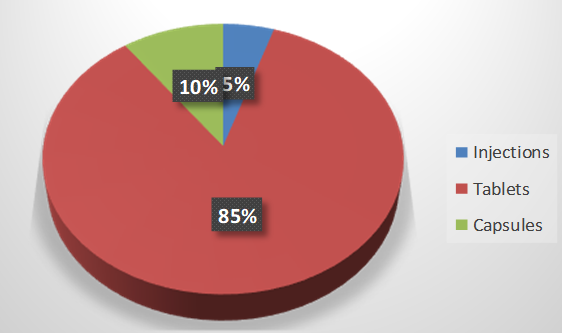

Parenteral drug administration was limited to 5% of prescribed medications (fig. 2), suggesting appropriate preference for oral routes when clinically feasible. Adherence to the Essential Drug List (EDL) was substantial, with 82% of prescribed drugs included in the national formulary.

Healthcare system performance indicators

Medication availability within the hospital dispensary was found to be 72%, indicating potential access barriers for patients requiring external procurement. Consultation efficiency metrics revealed brief patient interactions, with an average consultation time of 3 min (range: 1-8 min) and dispensing time of 90 sec (range: 30-180 sec).

Departmental variations

Significant inter-departmental variations were observed in prescribing practices and guideline adherence. The cardiology department demonstrated the highest level of compliance with established prescribing guidelines, while other departments showed variable adherence patterns.

Fig. 1: Patient demographics and other recording trends in prescriptions

Fig. 2: Graphical representation of injectable, tablets and capsules prescribed

Table 1: WHO/INRUD prescribing, patient-care and health-facility indicators observed in the prescription audit (n=600) in comparison to optimal reference value

| WHO/INRUD indicators | Average/percentage | Optimal value |

| Average number of drugs prescribed per encounter (Average) | 5.39 | 1.6–1.8 |

| Percentage of drugs prescribed by generic name | 88% | 100% |

| Antibiotic prescribed | 12% | 20.0%–26.8% |

| Injection prescribed | 5% | 13.4%–24.1% |

| Percentage of drugs prescribed from the EML | 82% | 100% |

| Average consultation time in minutes (min) | 3 min | ≥10 min |

| Average dispensing time in seconds (sec) | 90 sec | ≥180 secs |

| Percentage of medicines dispensed | 72% | 100% |

| Percentage availability of a copy of EDL or formulary | 100% | 100% |

DISCUSSION

Prescription documentation and legibility

The present study demonstrates excellent compliance with basic prescription documentation requirements, with 100% of prescriptions containing essential identifiers, including OPD registration numbers, consultation dates, and patient gender. This finding exceeds the documentation standards reported in several states the country, where basic patient identification remains problematic [6, 7]. However, the absence of complete patient names in 1.2% of prescriptions, while minimal, represents a critical safety concern that could lead to medication errors and patient misidentification. The finding that 11% of prescriptions exhibited illegible handwriting is particularly concerning from a patient safety perspective. Poor prescription legibility has been consistently identified as a leading cause of medication errors worldwide [8]. Recent systematic reviews have demonstrated that implementation of electronic prescribing systems can reduce medication errors and significantly decrease adverse drug events [9], suggesting an urgent need for digital transformation in prescription practices at the study institution.

Clinical documentation quality

The documentation of clinical examination findings in 78.9% of prescriptions and presumptive/definitive diagnoses in 75.1% represents suboptimal clinical record-keeping. These findings are consistent with recent studies conducted in similar healthcare settings in India [10, 11]. The absence of clinical rationale in approximately one-quarter of prescriptions raises concerns about prescription appropriateness and medico-legal documentation standards [12]. The high documentation rate of treatment duration (91%) is encouraging and aligns with current WHO recommendations for rational prescribing practices. This finding compares favourably with recent studies from other tertiary care centres in India. [13].

Prescribing patterns and polypharmacy

The average of 5.39 drugs per prescription indicates a concerning trend toward polypharmacy. This trend is also observed in other Indian tertiary care hospitals [14, 15]. Current evidence indicates that polypharmacy regimens involving five or more drugs are highly prone to unacknowledged prescribing errors due to complex drug-drug interactions and contraindications [16, 17]. The high polypharmacy rate in a superspeciality hospital setting may be attributed to the complex nature of cases, multiple comorbidities, and the involvement of different subspecialists in patient care. However, regular medication reconciliation and de-prescribing initiatives should be considered to optimize therapeutic outcomes while minimizing potential harm.

Generic prescribing and essential drug list compliance

The generic prescribing rate of 88% represents good adherence to WHO recommendations and national prescribing policies. But still there is scope of improvement to achieve 100% generic prescriptions as per WHO guidelines. This finding substantially exceeds generic prescribing rates reported in other parts of India [13, 18, 19]. High generic prescribing rates contribute to improved medication affordability and accessibility for patients while reducing healthcare costs [20].

The 82% compliance with the Essential Drug List (EDL) demonstrates good adherence to evidence-based formulary practices that aligns with recent studies from other Indian tertiary care centres [19]. However, the 18% deviation from EDL recommendations warrants investigation to ensure that non-EDL prescriptions are clinically justified and not driven by commercial influences.

Antibiotic prescribing patterns

The antibiotic prescribing rate of 12% is remarkably low compared to recent global trend of increased antibiotic consumption in tertiary care hospital standards [21, 22]. This finding may reflect the focus on outpatient prescriptions, where antibiotic use is generally lower than in inpatient settings but still it is significantly lower than any other Indian scenario as well [23, 24]. It indicates good antimicrobial stewardship practices at the institution fulfilling WHO criteria of less than 30% [25].

Parenteral drug usage

As per WHO prescribing indicators, the injectable encountered should be less than 20% of total drugs prescribes [25]. The parenteral drug prescribing value of 5% in the outpatient setting in our study suggests rational prescribing practices regarding route of administration in the ambulatory care setting.

Drug availability and access

The availability of 72% of prescribed medicines in the hospital dispensary represents a significant challenge for patient care continuity and medication adherence. Medication non-availability in hospital pharmacies can lead to treatment interruption, increased out-of-pocket expenses, and poor clinical outcomes [26]. This finding necessitates improved pharmaceutical supply chain management and formulary planning to ensure adequate stock levels of essential medications.

Consultation and dispensing times

The average consultation time of 3 min falls well below the minimum of 10 min for adequate patient assessment and counselling in the WHO guidelines for patient care indicators [7]. Longer consultations may be helpful to achieve clinical effectiveness and patient safety. This finding is consistent with time constraints reported in many overcrowded tertiary care hospitals in developing countries [27]. Inadequate consultation time may compromise diagnostic accuracy, patient education, and prescription appropriateness.

The 90-second dispensing time is also suboptimal for proper medication counselling and patient education. Adequate dispensing time, the WHO optimal value of which should be equal or more than ≥180 sec is essential for ensuring patient understanding of medication regimens and improving adherence [28].

Clinical and policy implications

The findings of this audit highlight several areas requiring immediate attention to improve prescription quality and patient safety. The implementation of electronic health records and e-prescribing systems could address legibility issues and improve documentation completeness. Regular prescription audits, feedback mechanisms, and continuing education programs are essential for maintaining high prescribing standards. The high polypharmacy rate necessitates the development of medication reconciliation protocols and clinical decision support systems to optimize therapeutic regimens. Improved inventory management systems are required to ensure better drug availability in hospital dispensaries.

LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design provides a snapshot of prescribing practices but may not reflect seasonal variations or temporal trends. The study was conducted at a single tertiary care institution, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other healthcare settings. Additionally, the audit did not assess clinical outcomes or patient satisfaction measures, which would provide a more comprehensive evaluation of prescription quality.

CONCLUSION

This prescription audit reveals both strengths and areas for improvement in prescribing practices at a tertiary care superspeciality hospital. While documentation of basic prescription elements and generic prescribing rates are commendable, concerns regarding polypharmacy, consultation times, and drug availability require urgent attention. Systematic interventions focusing on electronic prescribing, clinical decision support, and continuous quality improvement are essential for optimizing prescription practices and ensuring patient safety.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are thankful to the administration of the Gauhati Medical College and Hospital, for the support during the study.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed equally

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Sunny D, Roy K, Benny SS, Mathew DC, Gangadhar Naik JG, Gauthaman K. Prescription audit in an outpatient pharmacy of a tertiary care teaching hospital a prospective study. J Young Pharm. 2019;11(4):417-20. doi: 10.5530/jyp.2019.11.85.

World Health Organization. How to investigate drug use in health facilities: selected drug use indicators. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

Meena DK, Mathaiyan J, Thulasingam M, Ramasamy K. Assessment of medicine use based on WHO drug-use indicators in public health facilities of the South Indian Union Territory. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022 May;88(5):2315-26. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15165, PMID 34859476.

Aravamuthan A, Arputhavanan M, Subramaniam K, Udaya Chander J SJ. Assessment of current prescribing practices using World Health Organization core drug use and complementary indicators in selected rural community pharmacies in Southern India. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2017;10:1. doi: 10.1186/s40545-016-0074-6, PMID 27446591.

Ofori Asenso R, Agyeman AA. Irrational use of medicines a summary of key concepts. Pharmacy (Basel). 2016 Oct 28;4(4):35. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy4040035, PMID 28970408, PMCID PMC5419375.

Saha A, Bhattacharjya H, Sengupta B, Debbarma R. Prescription audit in outpatient Department of a Teaching Hospital of North East, India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2018;6(4):1241-7. doi: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20181275.

Marupaka J, Kodam L, Tamma NK, Karedla S. Prescription audit of patients in a Teritiary Care Hospital. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2020 Oct 21;9(11):1583-91. doi: 10.18203/2319-2003.ijbcp20204435.

Ariaga A, Balzan D, Falzon S, Sultana J. A scoping review of legibility of hand-written prescriptions and drug orders: the writing on the wall. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2023 Jul-Dec;16(7):617-21. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2023.2223972, PMID 37308401.

Ciapponi A, Fernandez Nievas SE, Seijo M, Rodriguez MB, Vietto V, Garcia Perdomo HA. Reducing medication errors for adults in hospital settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;11(11):CD009985. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009985.pub2, PMID 34822165.

Navadia KP, Patel CR, Patel JM, Pandya SK. Evaluation of medication errors by prescription audit at a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2023;14(4):275-84. doi: 10.1177/0976500X231222689.

Afrah ALM, Abdulla LM, Saleem N, Baktharatchagan A, Vishwanath U. Refining patient care: evaluating prescription practices of medical residents and interns in a teaching hospital through an audit. Sage Open Med. 2024 Nov 20;12:20503121241300902. doi: 10.1177/20503121241300902, PMID 39575311, PMCID PMC11580091.

Smith JD, Lemay K, Lee S, Nuth J, Ji J, Montague K. Medico-legal issues related to emergency physicians documentation in Canadian emergency departments. CJEM. 2023 Sep;25(9):768-75. doi: 10.1007/s43678-023-00576-1, PMID 37646956, PMCID PMC10495505.

Joshi R, Medhi B, Prakash A, Chandy S, Ranjalkar J, Bright HR. Assessment of prescribing pattern of drugs and completeness of prescriptions as per the World Health Organization prescribing indicators in various Indian Tertiary Care Centers: a multicentric study by rational use of medicines centers Indian council of medical research network under national virtual centre clinical pharmacology activity. Indian J Pharmacol. 2022 Sep-Oct;54(5):321-8. doi: 10.4103/ijp.ijp_976_21.

Bhagavathula AS, Vidyasagar K, Chhabra M, Rashid M, Sharma R, Bandari DK. Prevalence of polypharmacy, hyperpolypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2021 May 19;12:685518. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.685518, PMID 34093207, PMCID PMC8173298.

Rakesh KB, Chowta MN, Shenoy AK, Shastry R, Pai SB. Evaluation of polypharmacy and appropriateness of prescription in geriatric patients: a cross-sectional study at a Tertiary Care Hospital. Indian J Pharmacol. 2017 Jan-Feb;49(1):16-20. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.201036, PMID 28458417, PMCID PMC5351231.

Costanzo S, Di Castelnuovo A, Panzera T, De Curtis A, Falciglia S, Persichillo M. Polypharmacy in older adults: the hazard of hospitalization and mortality is mediated by potentially inappropriate prescriptions findings from the Moli-Sani study. Int J Public Health. 2024 Oct 24;69:1607682. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2024.1607682, PMID 39513180, PMCID PMC11540657.

Kaur U, Reddy J, Reddy NT, Gambhir IS, Yadav AK, Chakrabarti SS. Patterns, outcomes and preventability of clinically manifest drug-drug interactions in older outpatients: a subgroup analysis from a 6 y long observational study in North India. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2025 Jan;398(1):687-98. doi: 10.1007/s00210-024-03294-2, PMID 39046529.

Priyadharsini RP, Ramasamy K, Amarendar S. Antibiotic prescribing pattern in the outpatient departments using the WHO prescribing indicators and AWaRe assessment tool in a Tertiary Care Hospital in South India. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2022 Jan;11(1):74-8. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_527_21, PMID 35309648, PMCID PMC8930124.

Gujar A, Gulecha DV, Zalte DA. Drug utilization studies using WHO prescribing indicators from India: a systematic review. Health Policy Technol. 2021;10(3):100547. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2021.100547.

Chaudhary RK, Philip MJ, Santhosh A, Karoli SS, Bhandari R, Ganachari MS. Health economics and effectiveness analysis of generic anti-diabetic medication from jan aushadhi: an ambispective study in community pharmacy. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021 Oct 1;6:102303. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.102303, PMID 34626923.

Klein EY, Impalli I, Poleon S, Denoel P, Cipriano M, Van Boeckel TP. Global trends in antibiotic consumption during 2016-2023 and future projections through 2030. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2024;121(49):e2411919121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2411919121, PMID 39556760.

Bhattacharjee S, Mothsara C, Shafiq N, Panda PK, Rohilla R, Kaore SN. Antimicrobial prescription patterns in Tertiary Care Centres in India: a multicentric point prevalence survey. Eclinical Medicine. 2025 Mar 28;82:103175. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2025.103175, PMID 40224675, PMCID PMC11992528.

Priyadharsini RP, Ramasamy K, Amarendar S. Antibiotic prescribing pattern in the outpatient departments using the WHO prescribing indicators and AWaRe assessment tool in a Tertiary Care Hospital in South India. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2022 Jan;11(1):74-8. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_527_21, PMID 35309648, PMCID PMC8930124.

Kumar S, Siwach P, Mehta K, Mathur A. Assessment of antibiotic prescribing pattern using WHO access watch and reserve classification (AWaRe) at a Tertiary Care Centre of Northern India: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2025 Mar;19(3):12-6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2025/76248.20757.

Ofori Asenso R. A closer look at the World Health organizations prescribing indicators. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2016 Jan-Mar;7(1):51-4. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.179352, PMID 27127400, PMCID PMC4831494.

Chebolu Subramanian V, Sundarraj RP. Essential medicine shortages procurement process and supplier response: a normative study across Indian states. Soc Sci Med. 2021;278:113926. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113926, PMID 33892243.

Yahanda AT, Mozersky J. What’s the role of time in shared decision making? AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(5):E416-422. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2020.416, PMID 32449658.

Goruntla N, Ssesanga J, Bommireddy BR, Thammisetty DP, Kasturi Vishwanathasetty V, Ezeonwumelu JO. Evaluation of rational drug use based on WHO/INRUD core drug use indicators in a secondary care hospital: a cross-sectional study in Western Uganda. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2023 Sep 14;15:125-35. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S424050, PMID 37727328.