Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 4, 105-108Original Article

RE-EVALUATION OF NECK STAGING BY COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY SCAN, MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING AND ELECTIVE NECK DISSECTION IN CLINICALLY N0 NECK IN HEAD AND NECK CANCERS AND ITS HISTO-PATHOLOGICAL CORRELATION

SMITA RAY1, PREMANAND PANDA2, PRAGNYA PARAMITA MISHRA3*

1Department of ENT, Hi-tech MCH, Rourkela, Odisha, India. 2Department of Radiology, JP Hospitals and Research Centre, Rourkela, Odisha, India. 3Department of Pathology, Hi-tech MCH, Rourkela, Odisha, India

*Corresponding author: Pragnya Paramita Mishra; *Email: pparamita1982@gmail.com

Received: 15 Apr 2025, Revised and Accepted: 10 Jun 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: Thirty percent of all cancer cases are head and neck cancer. The most frequent way that these tumors spread is through lymphatic metastasis. In patients with head and neck tumors, cervical lymph node assessment is a crucial step in the staging process. Furthermore, the prognosis of patients with head and neck malignancies is greatly influenced by the identification of cervical lymph node metastases. The modalities available to detect metastatic lymph nodes are ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and scintigraphy. Our study is done to compare the efficacy of clinical examination, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and histopathological correlation after elective neck dissection and staging of lymph node metastasis in head and neck cancers.

Methods: This prospective study was carried out in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Hitech Medical College and Hospital, Rourkela, Odisha, between January 2023 and December 2024 in association with the department of radiodiagnosis. A total of 30 patients of all age groups and both sexes with clinically N0 neck with proven head and neck cancer and requiring surgery as the primary mode of treatment were included in the study. All CT and MRI images were assessed by a radiologist without prior knowledge of the clinical status of the patient. The result of the clinical examination, CT scan, and MRI was compared with the histopathological report.

Results: In the present study, the majority of patients ranged between the age group of 40-60 years (66.6%), with a mean age of 49.3 years. There was a marked male preponderance with a 2.75:1 male-to-female ratio, and the most common primary site was the larynx (40%). the maximum number of patients presented to the outpatient department when the primary was at the stage of T3 in the case of laryngeal tumors and T2 in the case of oral cavity tumors. When comparing the results of clinical examinations to histopathology, there were 30 clinically N0 necks, while 13 cases were found to be histopathologically positive. So, true positives were 17 (56.66%), and false negatives were 13 (43.33%). Out of 13 histopathologically proven positive necks, CT could diagnose metastasis in 7 cases, which showed a statistically significant correlation between CT scan and histopathology (p value 0.01). Out of 13 histopathologically proven positive necks, MRI could diagnose metastasis in 6 cases, which showed a statistically significant correlation between CT scan and histopathology (p value 0.02).

Conclusion: This study concludes that palpation alone was an inaccurate technique for assessment of the neck. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging had a higher accuracy for diagnosing metastatic disease than clinical examination. Both have comparable efficacy in detecting occult metastasis in the neck. Histopathological confirmation is indispensable in view of the low sensitivity of both modalities.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Lymphnode, Computed tomography, Magnetic resonance imaging, Metastasis

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i4.7030 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

According to GLOBOCAN 2020, India will see 2.1 million new cases of cancer by 2040, a 57.5% increase from 2020–2021 [1-3]. Additionally, one in nine Indians will get cancer in their lifetime 3. Thirty percent of all cancer cases are head and neck cancer [4]. The most frequent way that these tumors spread is through lymphatic metastasis. In patients with head and neck tumors, cervical lymph node assessment is a crucial step in the staging process. The best course of treatment and the patient's prognosis may be impacted by the occurrence of cervical lymph node metastases. [5] Depending on the pathological findings of the nodes, individuals with cervical lymph node metastases may be treated with radiation, chemotherapy, or selective or radical neck dissection [6–8]. Furthermore, the prognosis of patients with head and neck malignancies is greatly influenced by the identification of cervical lymph node metastases [9-11].

The neck is staged by palpation in most institutions in the world. Though it is inexpensive and can be repeated again and again, it is known to be associated with high false-positive and false-negative rates and low sensitivity and specificity. Moreover, there is a high incidence of occult metastasis in head and neck cancers, which is missed by palpation. Oncologists electively treat the neck to prevent occult metastases. This over-or under-treatment can be avoided by accurate staging methods with the help of imaging techniques. After histological confirmation, we evaluated the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging with palpation to examine their dependability in the staging of head and neck malignancies. We also evaluated the role of elective neck dissection in patients with clinically N0 head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Aim of the study is to compare the efficacy of clinical examination, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and histopathological correlation after elective neck dissection and staging of lymph node metastasis in head and neck cancers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective study was carried out in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at Hitech Medical College and Hospital, Rourkela, Odisha, between January 2023 and December 2024 in association with the department of radiodiagnosis. A total of 30 patients of all age groups and both sexes with clinically N0 neck with proven head and neck cancer and requiring surgery as the primary mode of treatment were included in the study. Pregnant women, patients with iodinated contrast material allergies, individuals with a history of radiation exposure or prior to surgery for head and neck cancer, any clinically palpable neck lymph node, and evidence of distant metastases are among the exclusion criteria.

A comprehensive general physical and otorhinolaryngological examination was conducted after a thorough and pertinent history was obtained. A complete assessment of the site, size, and extent of the primary tumor was done to properly stage the tumor. A biopsy was taken from the primary site and sent to the pathology department for histopathological examination. Patients' necks were carefully inspected for any palpable lymph nodes. Routine blood hemogram, chest x-ray, and abdominal ultrasound were done to rule out metastasis to the lung and abdomen. After clinical examination, all the patients were sent for contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Size greater than 1 cm, rim enhancement after intravenous contrast, core necrosis, spherical shape, three or more lymph nodes in the first drainage area, and extracapsular spread of illness are the criteria used to determine whether a node is positive on contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans. Considering these criteria, any node detected as metastatic on a computed tomography scan was documented and compared to other modalities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done in all cases, and nodes with an axial diameter of>10 mm, central necrosis, hypointensity on T1-weighted images that enhance after contrast injection, and focal inhomogeneous or hyperintense areas on T2-weighted images were considered positive nodes on MRI. All CT and MRI images were assessed by a radiologist without prior knowledge of the clinical status of the patient. The result of the clinical examination, CT scan, and MRI was compared with the histopathological report.

RESULTS

In this study, patients ranged in age from 20 to 80 years, with the majority in the age group of 40-60 years (66.66%), with a mean age of 49.3 years. There was a marked male preponderance, with 73.3% male and the rest, 26.7%, female. The male-to-female ratio was 2.75:1. In terms of primary cancer distribution, 12 instances (or 40% of cases) were laryngeal, which was followed by oral cavity (8 cases, or 26.66%), tongue (7 cases, or 23.33%), and lip (3 cases, or 10%). In our study, the maximum number of patients presented to the outpatient department when the primary was at the stage of T3 in the case of laryngeal tumors and T2 in the case of oral cavity tumors. 30 patients were taken for surgery; 18 patients underwent supra-omohyoid neck dissection with removal of level I, II, and III lymph nodes, and the remaining 12 underwent lateral neck dissection with removal of level II, III, and IV lymph nodes. When comparing the results of clinical examinations to histopathology, there were 30 clinically N0 necks, while 13 cases were found to be histopathologically positive. So, true positives were 17 (56.66%), and false negatives were 13 (43.33%).

Table 1: Comparision of computed tomography with histopathology results

| CT scan | Positive | Negative | Total |

| Positive | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Negative | 6 | 16 | 22 |

| Total | 13 | 17 | 30 |

Out of 13 histopathologically proven positive necks, CT could diagnose metastasis in 7 cases. 1 case diagnosed as positive on a CT scan did not reveal a tumor on histopathology. The p-value for CT is 0.01, which is statistically significant. The measure of agreement kappa=0.426 shows there is a low association between CT findings and histopathological findings.

Table 2: Comparision of MRI with histopathology results

| MRI | Positive | Negative | Total |

| Positive | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Negative | 7 | 16 | 23 |

| Total | 13 | 17 | 30 |

Out of 13 histopathologically proven positive necks, MRI could diagnose metastasis in 6 cases. 1 case diagnosed as positive in an MRI scan did not reveal a tumor on histopathology. The p-value for MRI is 0.02, which is statistically significant. The measure of agreement kappa=0.493 shows there is a low association between MRI findings and histopathological findings.

Table 3: Comparision of result of diagnostic modalities: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | Accuracy | |

| CT scan | 53.84 | 94.11 | 87.5 | 72.72 | 76.66 |

| MRI | 46.16 | 94.11 | 85.71 | 69.56 | 73.33 |

The results of the study calculated in terms of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy of the two diagnostic modalities, were as given in table 3.

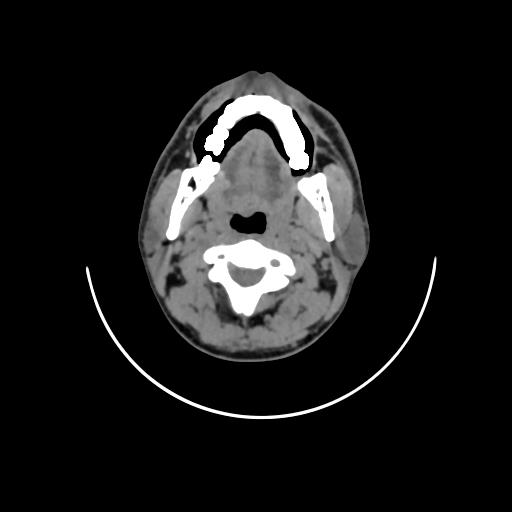

Fig. 1: Non-contrast CT reveals irregular contour of right lateral border of tongue

Computed tomography (fig. 1) changed the nodal staging of 8 patients out of 30. 7 clinically N0 necks were correctly upstaged to N1 later proved by histopathology. 1 was wrongly upstaged to N1, which remained N0 after histopathology.

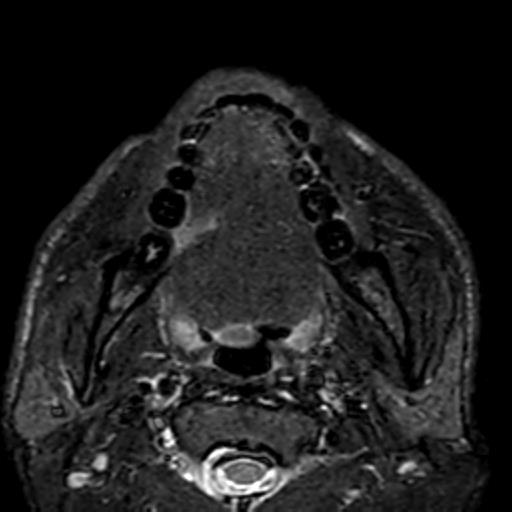

Fig. 2: Contrast-enhanced MRI T1 Fat sat reveals an enhancing irregular ulcer in right lateral border of tongue. No e/o cervical luymphadenopathy

DISCUSSION

Cervical lymph node evaluation is an important part of the staging procedure in patients with head and neck tumours. In addition to location, size, and spread of the primary tumor, the existence and the extent of lymph node metastasis determine the prognosis of affected patients and influence treatment modalities. In clinically N0 necks, the whole treatment rests on the excision of the primary. But if the surgeon is not sure of neck metastasis, prophylactic neck dissection is done. Therefore, a modality with high specificity and accuracy is taken up to detect neck metastasis. The modalities available to detect metastatic lymph nodes are ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and scintigraphy. The present study was regarding the comparison of neck staging by clinical method, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging.

In the present study, the majority of patients ranged between the age group of 40-60 years (66.6%), with a mean age of 49.3 years. There was a marked male preponderance with a 2.75:1 male-to-female ratio, and the most common primary site was the larynx (40%). All the patients were subjected to excision of the primary tumor and elective neck dissection. For laryngeal tumors, total laryngectomy along with lateral neck dissection was done. For tongue carcinoma, primary excision along with supraomohyoid neck dissection was done. In 3 cases of tongue carcinoma involving the mid-to-posterior one-third of the lateral border, the primary site was approached by mandibulectomy. For buccal mucosa carcinoma excision, flap reconstruction was done.

5 cases out of 10 laryngeal tumors (50%) and 8 cases out of 15 oral cavity tumors (53%) showed metastasis in histopathology. Lip and glottis carcinoma did not reveal any occult metastasis. False negative results of 43.3% for clinical examination in our study were fairly in tune with the values of 38% given by Michael H. Stevens et al. [12] and 30.8% by R. Feinmesser et al. [13]. Sako et al. [14] also reported high false negative results of 27-38% in his study. The accuracy of clinical examination obtained in our study was 56.665, which was comparable to the 59% reported by M. W. M. Vanden Brakel [15]. In literature there are many studies reporting high accuracy of palpation. Michael H. Stevens [12] reported an accuracy of 70%.

Computed tomography scans of necks in our study showed 8 positive and 22 negative results for metastatic lymph nodes. Out of 8, 7 were true positives and 1 was a false positive (12.5%). Out of 22 diagnosed negative patients, 6 were later found to be false negatives (27.27%, i. e. histopathologically containing tumors). However, Shalinder Singh Bhau et al. [16] study considered 73 nodes, out of which 23 (85.18%) were true positives and 4 (14.8%) were false positives, and 41 (89.13%) were true negatives and 5 (10.86%) were false negatives. In Philipp Thoenissen et al. [17] study, CT examinations showed a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity of 68%. In addition, the false-positive rate for CT examinations was 32%, and the false-negative rate was 33%. Positive predictive value of 85.71% and negative predictive value of 69.5% are high as compared to 81% and 60%, respectively reported Watkinson J. C. in 1991 [18]. The accuracy of 73.3% obtained for computed tomography in our study was in line with the 72% accuracy obtained by Feinmesser et al. [13] and the 71% accuracy obtained by Watkinson et al. [18]. In our study, CT scans changed the neck staging (N0 to N1) correctly in 7 (23.3%). One of them was downstaged from N1 to N0 after histopathological confirmation. Michael H. Stevens et al. [12] reported in his study of 40 patients that CT changed the staging of 30 patients correctly (25%), with 9 upstaged and 1 downstaged. These differences in the studies may be due to the use of larger sections of scans, different criteria used for considering the node positive, or bolus or continuous contrast infusion.

MRI done for 30 patients in our study showed 7 positive and 23 negative results for metastatic lymph nodes. Out of 7, 6 were true positives and 1 was a false positive (14.28%). Out of 23 diagnosed as negative, 7 were later found to be false negative (30.43%). The sensitivity (46.16%) and specificity (94.11%) for MRI in our study, while the sensitivity was 66% and the specificity was 68% in Philipp Thoenissen's [17] study. In literature, some studies, like M. W. M. Vanden Brakel [15], have reported high sensitivity (81%) and specificity (88%) for MRI. A positive predictive value of 85.7% and a negative predictive value of 69.5% were seen in our study. H. D. Curtin et al. [19] reported a positive predictive value of 52% and a negative predictive value of 79%. In our study the accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging of 73.3% is fairly in tune with that of M. W. M. Vanden Braken [15] of 75% in clinically N0 neck. Most studies that have compared the accuracy of CT scans and MRI imaging for the assessment of the neck have found no significant difference between these two modalities [19]. Reliable comparisons of sensitivity and specificity between different studies are not possible owing to non-equivalent patient populations. Furthermore, different studies are not comparable owing to the varying radiology criteria used and the different imaging techniques. The present study also showed no significant difference between CT and MRI in terms of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy. The present study also showed palpation to be inaccurate in comparison to the assessment of a clinically N0 neck. Both CT scans and MRIs are superior to palpation in detecting metastatic neck disease. They were reliably upstaged in nearly 54% of cases that were false negatives at palpation.

Owing to comparable results of CT scans and MRIs in staging the neck, the choice between both could be based on evaluation of the primary tumor. For tumors of the buccal mucosa and lip, MRI should be preferred, while for laryngeals, a CT scan is better. Advantages of CT over MRI are less time consumption, fewer motion artifacts, and cost factors. Advantages of MRI over CT are no exposure to ionizing radiation or iodinated contrast, imaging is possible in every anatomical orientation, lymph nodes are clearly differentiated from blood vessels, and evaluation of retroperitoneal nodes.

A disadvantage of CT and MRI is that they use morphologic criteria for metastasis in lymph nodes that are based on tumor-induced differences in size and contrast enhancement. The limitation of these morphology criteria can only be overcome by obtaining histopathologic evidence of metastasis.

CONCLUSION

This study concludes that palpation alone was an inaccurate technique for assessment of the neck. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging had a higher accuracy for diagnosing metastatic disease than clinical examination. All head and neck cancer patients with a clinically normal neck and probability of occults (>20%) should undergo CT or MRI. Both have comparable efficacy in detecting occult metastasis in the neck. Either of the two could be done in view of the evaluation of the primary tumor with no added cost for separate assessment of the cervical lymph node status. In view of the high positive predictive value of both modalities, patients with a clinically normal neck examination and an abnormal CT or MRI should be suspected of having metastasis. Histopathological confirmation is indispensable in view of the low sensitivity of both modalities. Elective neck treatment should be considered for the management of clinically N0 neck, particularly in Indian setups where there is significant loss to follow-up, rather than elective neck investigation with a wait-and-watch policy. The neck should be approached surgically if the mode of treatment of the primary tumor is surgery. Preoperative imaging assessments were useful but not adequate in the detection of micrometastasis. Available imaging modalities cannot replace the role of elective neck dissection as a diagnostic procedure for staging of N0 neck. Continued prospective studies are needed to establish a definite mode to detect occult nodal disease, thus decreasing the burden of under-or overtreatment of N0 neck.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed equally

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Pineros M, Znaor A. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: an overview. Int J Cancer. 2021 Aug 15;149(4):778-89. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33588, PMID 33818764.

World Health Organization. WHO report on cancer: setting priorities, investing wisely and providing care for all. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Sathishkumar K, Chaturvedi M, Das P, Stephen S, Mathur P. Cancer incidence estimates for 2022 and projection for 2025: result from national cancer registry programme India. Indian J Med Res. 2022 Oct-Nov;156(4-5):598-607. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.ijmr_1821_22, PMID 36510887.

Kulkarni MR. Head and neck cancer burden in India. Int J Head Neck Surg. 2013;4(1):29-35. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10001-1132.

Foote RL, Olsen KD, Davis DL, Buskirk SJ, Stanley RJ, Kunselman SJ. Base of tongue carcinoma: patterns of failure and predictors of recurrence after surgery alone. Head Neck. 1993 Jul-Aug;15(4):300-7. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880150406, PMID 8360051.

Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Robbins KT, Leemans CR, Shah JP, Shaha AR. Changing concepts in the surgical management of the cervical node metastasis. Oral Oncol. 2003 Jul;39(5):429-35. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00010-1, PMID 12747966.

Tankere F, Camproux A, Barry B, Guedon C, Depondt J, Gehanno P. Prognostic value of lymph node involvement in oral cancers: a study of 137 cases. Laryngoscope. 2000 Dec;110(12):2061-5. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200012000-00016, PMID 11129021.

Shah JP. Cervical lymph node metastases diagnostic therapeutic and prognostic implications. Oncology (Williston Park). 1990;4(10):61-5. PMID 2149826.

Golder WA. Lymph node diagnosis in oncologic imaging: a dilemma still waiting to be solved. Onkologie. 2004;27(2):194-9. doi: 10.1159/000076912, PMID 15138355.

O Brien CJ, McNeil EB, McMahon JD, Pathak I, Lauer CS, Jackson MA. Significance of clinical stage extent of surgery and pathologic findings in metastatic cutaneous squamous carcinoma of the parotid gland. Head Neck. 2002 May;24(5):417-22. doi: 10.1002/hed.10063, PMID 12001070.

Kau RJ, Alexiou C, Stimmer H, Arnold W. Diagnostic procedures for detection of lymph node metastases in cancer of the larynx. ORL J Oto Rhino Laryngol Relat Spec. 2000;62(4):199-203. doi: 10.1159/000027746, PMID 10859520.

Stevens MH, Harnsberger HR, Mancuso AA, Davis RK, Johnson LP, Parkin JL. Computed tomography of cervical lymph nodes staging and management of head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985 Nov;111(11):735-9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1985.00800130067007, PMID 4051864.

Feinmesser R, Freeman JL, Noyek AM, Birt D. Metastatic neck disease reply. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114(7):808-9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1988.01860190112038.

Sako K, Pradier RN, Marchetta FC, Pickren JW. Fallibility of palpation in the diagnosis of metastases to cervical nodes. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1964 May;118:989-90. PMID 14143467.

Van Den Brekel MW, Castelijns JA, Stel HV, Golding RP, Meyer CJ, Snow GB. Modern imaging techniques and ultrasound-guided aspiration cytology for the assessment of neck node metastases: a prospective comparative study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1993;250(1):11-7. doi: 10.1007/BF00176941, PMID 8466744.

Bhau SS, Bhau KS, Arshad S, Kalsotra P, Zaffar S, Rashid A. Clinicoradiological and histopathological comparative study of nodal metastasis in head and neck cancers. AIMDR. 2016;2(4):93-9. doi: 10.21276/aimdr.2016.2.4.27.

Thoenissen P, Heselich A, Burck I, Sader R, Vogl T, Ghanaati S. The role of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients preoperative staging. Front Oncol. 2023;13:972042. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.972042, PMID 36959788.

Watkinson JC, Todd CE, Paskin L, Rankin S, Palmer T, Shaheen OH. Metastatic carcinoma in the neck: a clinical radiological scintigraphic and pathological study. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1991 Apr;16(2):187-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1991.tb01974.x, PMID 1649018.

Curtin HD, Ishwaran H, Mancuso AA, Dalley RW, Caudry DJ, McNeil BJ. Comparison of CT and MR imaging in staging of neck metastases. Radiology. 1998 Apr;207(1):123-30. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.1.9530307, PMID 9530307.