Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 5, 91-94Original Article

A STUDY ON FACTORS INFLUENCING CONTRACEPTIVE CHOICES AMONG POST-PARTUM WOMEN IN A TERTIARY HEALTH CENTRE, TIRUPATI

DORAI DEEPA*, Y. ARUNA, VANKEEPURAM VISHNU KALYANI

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, S. V. Medical College, Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, India

*Corresponding author: Dorai Deepa; *Email: drddeepa@gmail.com

Received: 10 Jun 2025, Revised and Accepted: 30 Jul 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: There is an unmet need for family planning among postpartum women in developing countries. Reasons for urban-rural disparity in family planning use are not much known. This study aims to study factors influencing contraceptive choice in postpartum women, reasons for rural and urban disparity and psychosocial and environmental dimensions to the contraceptive process.

Methods: Prospective cross-sectional study was carried out in department of obstetrics and gynecology for a period of six months by using a standardized questionnaire. All women who delivered live baby were included in the study.

Results: Among 300 study participants, 158 were from rural areas and 142 were from urban areas. Prior usage of contraceptives was noted in 54.6%. Majority of participants (80.6%) were willing to use a contraceptive method after counseling. The most commonly accepted methods of contraception were condoms and female sterilization. The most cited reason for choice of contraceptive was convenience.

Conclusion: There was a high intent among postpartum women to use a contraceptive method. However, there is still a portion of women, mostly belonging to rural areas that are unaware and unwilling to use contraception.

Keywords: Oral contraceptive pills (OCP), Intrauterine device (IUD), Female sterilization, Male sterilization, Emergency contraception, Parity

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i5.7053 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Among the 1.9 billion women of reproductive age group 15 to 49 y worldwide in 2019, 1.1 billion have a need for family planning. Of these 842million are using contraceptive methods and 270 million having an unmet need for contraception. Postpartum women are among those with greatest unmet need for family planning. According to data from 57 countries in 2005-2013 estimates 32-62% of postpartum women had an unmet need for family planning. One of the global health priorities is to address the high unmet need for contraception among postpartum women in developing countries [1, 2].

Prevention of unwanted and closely spaced pregnancies leads to maternal, infant morbidity and mortality. Evidences show that interpregnancy intervals shorter than 18mo. increase the risk of adverse outcome [3].

WHO recommends birth spacing interval of 24 mo before couple attends next pregnancy. WHO advises to include non-medical aspects in the development of their advice while counseling by health professionals [4]. It advises to take in to account the ethics and socio cultural norms of the women. Recommendations by the health professionals rarely give importance to the personal wishes of women [5].

According to the NFHS 58.5% of the currently married women in the reproductive age group or their husband was using modern family planning method in the urban corresponding to 55.5% in the rural population in 2019 to 2021. Knowledge of contraception is almost universal in Andhra Pradesh. Only 26% of currently married women know about the lactationalamenorrhea method and 14% know about the female condoms. The contraceptive prevalence rate in Andhra Pradeshamong married women age 15-49 y is 71% [6].

Reasons for urban-rural disparity in family planning use are not much known. The urban-rural disparity in the use of different family planning methods may also reflect the difference in availability and access to different methods in rural and urban population [7].

In depth analysis of rural-urban disparity in family planning is relevant to understanding the impact of official family planning programmes and for strengthening family planning service delivery system [8]. Contraceptive process in clinical practice has sociodemographic, psychosocial and environmental dimensions to it [9, 10].

This study aims to ascertain the factors influencing contraceptive choice in postpartum women, reasons for rural and urban disparity and to connect the psychosocial and environmental dimensions to the contraceptive process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Prospective cross-sectional study was carried out in department of obstetrics and gynecology in Government Maternity Hospital, Tirupati. This study was conducted for a period of six months after obtaining Institutional Scientific and Institutional Ethics committee approval (Lr. No.354/2024). All the women who delivered live baby were included in the study. All women who had cesarean section and undergone bilateral tubectomy were excluded from the study.

Demographic details names, age, parity, address were taken. A standardized questionnaire in Telugu language was used to collect data from the study participants through face-to-face interview after obtaining informed consent form. All issues related to privacy and confidentiality was adhered to. Interviews were conducted in a private scheduled area to maintain confidentiality. They were counseled about temporary and permanent methods of contraception and allowed to choose a method of contraception of their choice.

RESULTS

A total of 300 participants were included in the study. Among them, 158 were from rural areas and 142 were from urban areas. Their sociodemographic profile including age, religion, family income, occupation and educational status were studied mean age was 28.4 y. More than two thirds of patients belonged to 20 to 30 y age, dominated by 21 to 25 y (35%). Hindus were 69%, Muslims were 25% and others were 6% respectively as mentioned in table 1.

Table 1: Sociodemographic profile of participants

| Sociodemographic profile | No. of cases, (300) n(%) | Rural, (158) | Urban, (142) |

| Age group (years) | |||

| 15–20 | 15(5) | 9 | 6 |

| 21–25 | 105(35) | 72 | 33 |

| 26–30 | 90(30) | 42 | 48 |

| 31–35 | 84(28) | 34 | 50 |

| 36–40 | 6(2) | 1 | 5 |

| Religion | |||

| Hindu | 207(69) | 102 | 105 |

| Muslim | 75(25) | 47 | 28 |

| Others | 18(6) | 9 | 9 |

| Family income (INR per month) | |||

| <3000 | 18(6) | 14 | 4 |

| 3,000–5,000 | 33(11) | 29 | 4 |

| 6,000–10,000 | 63(21) | 42 | 21 |

| >10,000 | 186(62) | 73 | 113 |

| Education status | |||

| Illiterate | 21(7) | 12 | 9 |

| Primary | 63(21) | 41 | 22 |

| Secondary | 72(24) | 21 | 51 |

| Higher secondary | 96(32) | 47 | 49 |

| Graduate | 36(12) | 28 | 8 |

| Postgraduate | 12(4) | 9 | 3 |

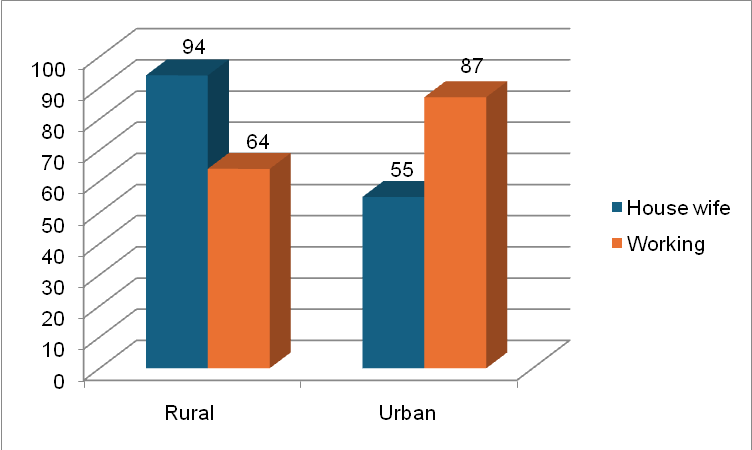

Family income of 62% of participants was more than Rs. 10000/-per month. At least 50% of the participants had an education of higher secondary level or above. About half of the participants (50.3%) were working individuals as depicted in fig. 1. Using chi square test of independence, the p-value is 0.00033. The result is significant at p<0.05.

Fig. 1: Occupation of participants (Urban and rural distribution)

Prior usage of contraceptives was noted in 54.6% of participants. Majority of participants (80.6%) were willing to use one or the other contraceptive method after counseling. When the choice of contraceptive was discussed with participants, rural women preferred female sterilization (22.1%), condoms (20.8%) and natural methods (13.2%); whereas urban women preferred IUCD (20.4%), condoms (13.3%) and injectable (12.6%). Distribution of cases according to contraceptive of choice is detailed in table 2.

Table 2: Distribution of cases according to contraceptive choice

| Contraceptive methods | Total number n(%) | Rural | Urban |

| Natural | 33 (11) | 21 | 12 |

| Condoms | 52 (17.3) | 33 | 19 |

| OCPs/POP | 31 (10.3) | 14 | 17 |

| IUCD | 39 (13) | 10 | 29 |

| Injectable | 21(07) | 3 | 18 |

| Emergency contraceptives | 8 (2.6) | 2 | 6 |

| Male sterilization | 10 (3.33) | 4 | 6 |

| Female sterilization | 48 (16) | 35 | 13 |

| None | 58 (19.3) | 36 | 22 |

Source of knowledge in participants was media, friends and partner. Majority of participants were mono or biparous (94.6%). Only 5% of the participants were multiparous as mentioned in table 3.

Table 3: Parity of the participants

| Parity | Rural | Urban |

| 1 | 64 | 71 |

| 2 | 81 | 68 |

| 3 | 9 | 2 |

| >3 | 4 | 1 |

Nearly one fifth of participants (19.3%) were reluctant to use contraceptives even after counseling. Reasons for non-acceptance are mentioned in table 4. Wanting pregnancy or the preference of male child were the predominant factors (36.2%) for non-acceptance of contraception. Fear of side effects, lack of knowledge and husband opposition played major role in rural participant’s reluctance.

Table 4: Reason for non-acceptance of contraception

| Reason | Rural n=36 | Urban, n=22 |

| Lack of knowledge | 6 | 0 |

| Fear of side effects | 7 | 5 |

| Religious belief | 2 | 1 |

| Husband opposition | 6 | 5 |

| Not necessary | 2 | 3 |

| They want pregnancy | 9 | 6 |

| Preference of male child | 4 | 2 |

DISCUSSION

In this study of postpartum breastfeeding women surveyed, a high intention to use contraception was noted. The most commonly accepted methods of contraception were condoms, closely followed by female sterilization. The most cited reason for choice of contraceptive was convenience.

Demographic and economic components were cited as influencing factors in the choice of contraception. Women in urban areas preferred IUCD, whereas women in rural areas preferred female sterilization or condoms. This choice mostly depended on the age and parity of the participant. Multiparous females above the age of 30 y preferred tubal sterilization, whereas monoparous women below 30 y preferred condoms or withdrawal method. These results align with the results of Doley R et al. and Borathkur S et al. [11, 12].

Household income and educational qualification also affected the choice of contraceptive. Women with little income and less education opted for no contraception or natural methods pertaining to financial constraints. In this study, we could not elicit differences of choice based on religious grounds. In a study by Pradhan et al. [13], authors reported that muslim women opted more for IUDs. Similarly, in a study by Mogeni et al., women of Christian faith opted more for the implants [14].

A high intent was noted among the participants of this study to use contraception post counseling. This indicates the importance of healthcare worker counseling in addressing the concerns and helping choose an appropriate contraceptive. Nineteen percent of participants in our study did not intend to use contraception before six months postpartum. Women who do not initiate contraception by six months postpartum are at an increased risk of having an unintended pregnancy as there is decline in efficacy of lactational amenorrhea [15].

Condoms followed by female sterilization, IUDs, natural methods, OCPs, injectables, male sterilization and emergency contraceptives were the preferred order of choice. Rural and urban status of participants played a role in this choice, with rural women preferring noninvasive and economical methods. These results correlate with other similar studies [16]. Most common reason for non-acceptance of contraception was the want of pregnancy. Social media, family and friends along with their partners played a major role as sources of information for contraception.

The primary limitation of this study is the data is from a single urban hospital, findings may not be generalizable. In person interviews and questionnaires may have led to interviewer bias, though efforts were made to reduce the same. Assessment of woman during immediate postpartum period and inclusion of sociodemographic factors are the strengths of the study.

CONCLUSION

Postnatal contraception needs to be addressed in a multifaceted way involving sociodemographic, cultural, clinical and health factors. Though there was a high intent among postpartum women to use a contraceptive method, there is still a portion of women, mostly belonging to rural areaswho are unaware and unwilling to use contraception. Proper guidelines to counsel patients starting from prenatal period, not only improves adherence to contraception, but also helps in reducing maternal and newborn mortality with properly spaced pregnancies.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Barclay L. CDC updates guidelines for postpartum contraceptive use; 2011. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/746177.

Vernon R. Meeting the family planning needs of postpartum women. Stud Fam Plann. 2009;40(3):235-45. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00206.x, PMID 19852413.

Ross JA, Winfrey WL. Contraceptive use intention to use and unmet need during the extended postpartum period. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2001;27(1):20-7. doi: 10.2307/2673801.

Hobcraft J. Demographic and health surveys. In: Hobcraft J, editor. The health rationale for family planning: timing of births and child survival. 1st ed. New York: United Nations; 1994. p. 112.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS). The third National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005-06. Int Insti Popul Sci Mumbai. 2007;2:1-168.

World Health Organization. Report of a WHO technical consultation on birth spacing. In: WHO, editor. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. p. 1-37.

Rutstein SO. Effects of preceding birth intervals on neonatal infant and under five years mortality and nutritional status in developing countries: evidence from the demographic and health surveys. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2005;89(S1):S7-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.012.

Conde Agudelo A, Belizan JM. Maternal morbidity and mortality associated with interpregnancy interval: cross-sectional study. BMJ. 2000;321(7271):1255-9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1255, PMID 11082085.

B Robey, J Ross, I Bhushan. Meeting unmet need: new strategies. Popul Rep J. 1996 Sep:(43):1-35.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. India’s vision FP 2020. Family Planning Division; 2020.

Doley R, Pegu B. A retrospective study on acceptability and complications of PPIUCD insertion. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2016;5(31):1631-4. doi: 10.14260/jemds/2016/384.

Borthakur S, Sarma AK, Alakananda A, Bhattacharjee AK, Deka N. Acceptance of post partum intra-uterine contraceptive device (PPIUCD) among women attending Gauhati Medical College and Hospital (GMCH) for delivery between Jan 2011 to Dec 2014 and their follow up. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2015;4(92):15756-8. doi: 10.14260/jemds/2015/2276.

Pradhan E, Canning D, Shah IH, Puri M, Pearson E, Thapa K. Integrating postpartum contraceptive counseling and IUD insertion services into maternity care in Nepal: results from stepped wedge randomized controlled trial. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0738-1, PMID 31142344.

Mogeni R, Mokua JA, Mwaliko E, Tonui P. Predictors of contraceptive implant uptake in the immediate postpartum period: a cross sectional study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24(6):438-43. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2019.1670344, PMID 31566415.

Berens P, Labbok M, Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM clinical protocol #13: contraception during breastfeeding, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(1):3-12. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2015.9999, PMID 25551519.

Rahmanpour H, Mousavinasab SN, Hosseini SN, Shoghli A. Preferred postpartum contraception methods and their practice among married women in Zanjan, Iran. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60(9):714-8. PMID 21381574.