Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 6, 112-121Original Article

“HOSPITAL-BASED STUDY TO ASSESS THE EFFECTIVENESS AND SAFETY OF ANTIDIABETIC MONOTHERAPY IN CONTRAST TO COMBINATION THERAPY”

OLIVER STEEVO PINTO, RAKSHITH SHETTY*, U. Y. FAREENA FAIZAL, ASHNA SAYISH, CHRISTY T. CHACKO, A. R. SHABARAYA

Department of Pharmacy Practice, Srinivas College of Pharmacy, Valachil, Mangalore-574143, India

*Corresponding author: Rakshith Shetty; *Email: rakshiths423@gmail.com

Received: 12 Aug 2025, Revised and Accepted: 02 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aims to compare the effectiveness and safety of antidiabetic monotherapy versus combination therapy in managing T2DM.

Methods: A prospective, observational study was conducted over six months in the general medicine department, involving 152 inpatients with T2DM. Patients aged 18 or above, with HbA1c ≥ 6.5% and/or GRBS ≥ 200 mg/dl, and on either monotherapy or combination therapy were included. Data were collected from patient records and caregivers.

Results: The results indicated that combination therapy demonstrated superior glycemic control compared to monotherapy, which was statistically significant (p<0.05). Monotherapy was prevalent, with biguanides and sulphonylureas being the most prescribed drugs. However, combination therapy showed a higher incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), particularly among older patients. Metformin was identified as the safest oral hypoglycemic agent (OHA). The study also revealed significant cost savings when using Jan Aushadhi medications compared to branded alternatives.

Conclusion: The findings underscore the necessity for regular blood glucose monitoring and personalized treatment plans to manage T2DM effectively. The study highlights the economic advantages of prescribing low-cost generics, which can improve medication adherence and health outcomes, especially in financially constrained patients. The integration of lifestyle modifications with pharmacotherapy is crucial for enhanced glycemic control. This study emphasizes the importance of combination therapy for better glycemic control in T2DM while acknowledging the increased risk of ADRs. It advocates for the economic benefits of Jan Aushadhi drugs, suggesting a cost-effective approach to diabetes management. Healthcare providers must focus on comprehensive care, integrating clinical guidelines and promoting interdisciplinary collaboration to improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Antidiabetic therapy, Glycemic control, Adverse drug reactions, Cost-minimization

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i6.8004 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is the most predominant disease affecting more than 180 million people globally, around 400 million people will have diabetes by 2030 [1]. Diabetes, which was initially an entity in developed countries and the urban areas, has now percolated deeply in developing countries and into the peri-urban and rural areas [2]. According to recent epidemiological surveys, the prevalence of (type 2 diabetes mellitus) DM in India ranges from 5% to 17%. The burden is expected to increase as a result of rapid demographic and lifestyle changes [3].

The major conventional hypoglycemic drugs used for the treatment of diabetes include biguanides, sulfonylureas, SGLT2 inhibitors, DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, and thiazolidinediones (TZDs), etc. These drugs can act on different targets to effectively respond to the complex mechanisms of diabetes and could work synergistically to better control the blood glucose in diabetes patients [4].

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European association for the study of diabetes (EASD) recommend a conventional step-by-step approach for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) that includes starting with lifestyle modifications, medical nutritional therapy, and exercise. If haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels are higher than the target of 7.0%, metformin monotherapy is then added. Still, less than half of T2DM patients meet the suggested HbA1c goals. The progressive nature of type 2 diabetes and the shortcomings of the available treatments, such as low tolerability and adherence, are to blame for the inability to achieve appropriate glycaemic control [5].

The recent American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) and ADA/EASD guidelines recommend treatment intensification with an additional drug if monotherapy does not achieve or maintain an HbA1c target after 3 mo. The preferred third-line treatment includes insulin initiation or a triple combination of oral blood glucose-lowering drugs [6].

Combining various agents like glinides, thiazolidinediones, sulfonylureas, and carbohydrate digestion inhibitors offers an alternative approach for treating type 2 diabetes in patients with moderate to high HbA1c levels. However, adverse events and tolerability issues may diminish the benefits of combination therapy. An ideal combination should address central pathophysiology and ensure safety and effective glycemic control in clinical practice. Ongoing research compares newer and older diabetes medications, aiming to provide a comprehensive overview for stakeholders, including patients and clinicians.

Objectives

Primary objective

To analyse and compare the effectiveness and safety of antidiabetic monotherapy and combination therapy.

Secondary objectives:

To compare the glycemic control quantitatively among the therapy.

To assess the prevalence of undesirable effects of treatment.

To study the impact of comorbidity in selection of antidiabetic therapy.

To estimate and compare the cost-minimization of commonly used combination and monotherapy in managing type 2 diabetes Mellitus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design: A prospective, observational study will be carried out among inpatients in the general medicine department to compare the effectiveness and safety of anti-diabetic monotherapy to combination therapy. The study was completed in the period of 6 mo.

Sample size: 152

Study criteria

Inclusion criteria

Patients of either gender aged 18 or above suffering from type 2 diabetes mellitus with or without any other co-morbid condition.

Taking either mono or a combination of anti-diabetic medications. Subjects should have an HbA1c ≥ 6.5% and/or GRBS of ≥ 200 mg/dl to be included in the study.

In the case of a patient receiving monotherapies or dual combination therapies at different times during the study period, the patient will be included in both groups that is monotherapy and combination therapy group.

Exclusion criteria

Diabetes mellitus type 1 patients, gestational diabetics.

Patients with acute sickness requiring insulin, those on corticosteroids, and pregnant and lactating women were excluded from the study.

Source of data collection

The required information will be collected from Patient, patient’s medical records and patient caregiver.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used for the analysis and suitable statistical tests will be applied to analyse the data.

The collected data will be analysed using Microsoft Excel 2019 and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

This study analysed 152 patients, with 55.9% being male and 44.1% female. Regarding age distribution, patients were divided into three groups: less than 40 y old (8% of the total), between 40 and 60 y old (47%), and over 60 y old (45%).

Table 1: Patient characteristics

| Variables (N= 152) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Gender | Male | 85 | 55.90 |

| Female | 67 | 44.10 | |

| Age in years | <40 | 13 | 8.00 |

| 40-60 | 71 | 47.00 | |

| >60 | 68 | 45.00 |

Prescribing pattern of different dosage forms in T2DM

The present study reveals that 59.8% of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients use oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs), totalling 91 patients, while 40.2% rely on Insulin therapy, comprising 61 patients. Among them, 87 patients undergo Monotherapy with a single medication, while 65 receive Combination therapy with multiple medications. These insights underscore the varied treatment strategies employed to manage T2DM, emphasizing both oral and injectable therapies tailored to individual patient needs.

Table 2: Type of therapy

| Type of therapy | Frequency(n) | Percentage (%) |

| Monotherapy | 87 | 57.2 |

| Combination therapy | 65 | 42.8 |

Different classes of drug used among the therapies in the study

The data from 152 participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) reveals that biguanides were the most commonly prescribed monotherapy (44%), followed by Insulin preparations (40%), while the predominant combination therapy was biguanide+sulfonylurea (77%), with a notable increase in the usage of DPP-4 Inhibitors rising from 3% in monotherapy to 18% when combined with Biguanides, and 5% of patients received a combination of Biguanides+SGLT2 inhibitors.

Effectiveness

Therapy Analysis: Monotherapy was used by 87 patients, and combination therapy by 65 patients. Glycemic control was better in the combination therapy group, with 48 controlled and 17 uncontrolled, showing a significant difference with a p-value of 0.0056.

Prevalence of undesirable effects potentially attributed to antidiabetic therapy

Age-wise distribution of ADR

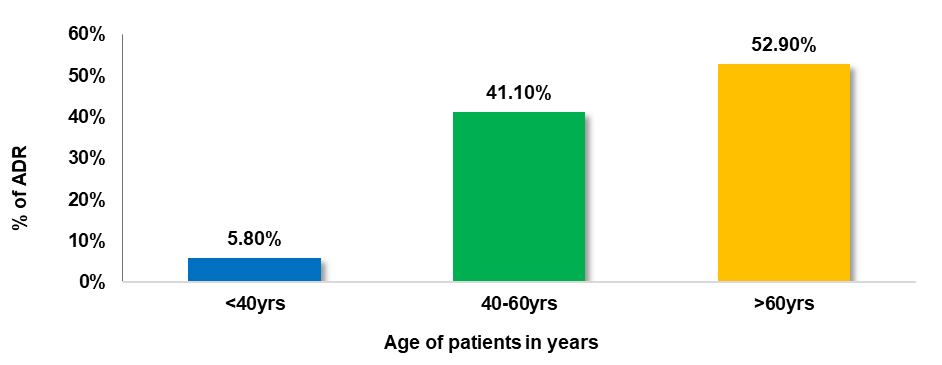

52.9% of the patients who experienced ADRs were above 60 y old, 41.1% were in the age group of 40-60 y and the least (5.8%) were seen in the age group of less than 40 y. The geriatric population was more prone to ADR than the age group of 40-60 y, whereas the age group below 40 y experienced the least ADR.

Table 3: Effectiveness of monotherapy in contrast to combination therapy

| Type of therapy | Glycemic control | ||

| Controlled | Uncontrolled | *p-value | |

| Monotherapy | 45 | 42 | 0.0056 |

| Combination therapy | 48 | 17 | |

Controlled: RBS≤ 140 mg/dl at p<0.05, Uncontrolled: RBS>140 mg/dl *p value using chi-square test

Table 4: Effectiveness of the monotherapy

| Class of drug | Glycaemic control | ||

| Controlled | Uncontrolled | p-value (at p<0.05) | |

| DPP4 inhibitor | 1 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Sulfonylureas | 3 | 5 | |

| Insulin preparations | 13 | 12 | |

| Biguanide | 15 | 12 | |

Table 5: Effectiveness of the combination therapy

| Class of drug | Glycaemic control | ||

| Controlled | Uncontrolled | p-value (at p<0.05) | |

| Biguanide+sulfonylurea | 28 | 3 | 0.2 |

| Biguanide+DPP4 inhibitor | 6 | 1 | |

| Biguanide+SGLT2 inhibitor | 1 | 1 | |

Fig. 1: Distribution of ADRs among different age groups

Gender-wise distribution of ADR

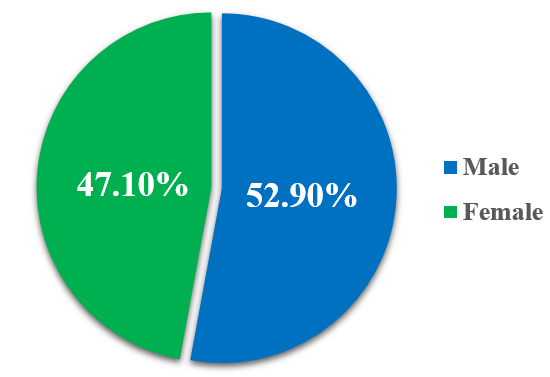

The study revealed that the male population 9 (52.9%) predominated over female population 8 (47%) in ADR occurrence.

Types of adverse effects noticed

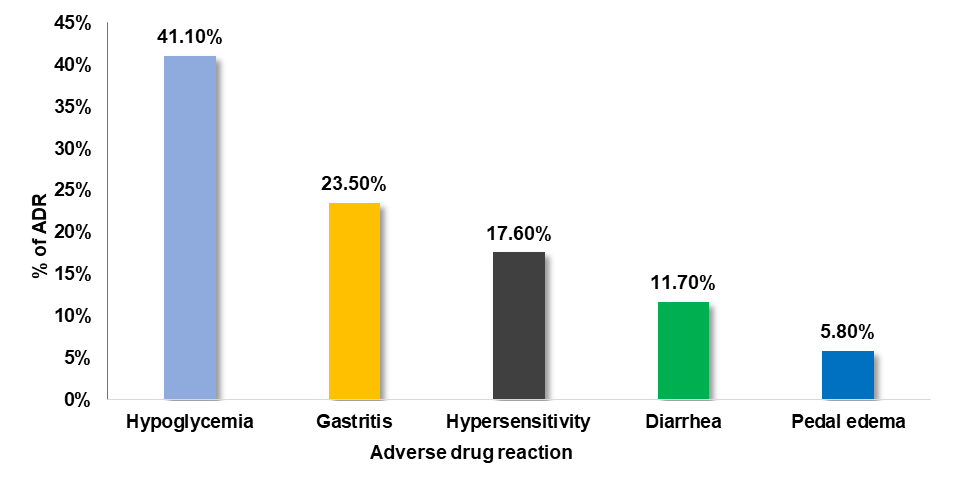

The current study revealed that the most occurred adverse effects include hypoglycemia (41.1%), gastritis (23,5%), hypersensitivity (17.6%), diarrhoea (11.7%), and pedaledema (5.8%).

Fig. 2: Distribution of ADR among the genders

Fig. 3: Type of ADRs reported by the patient

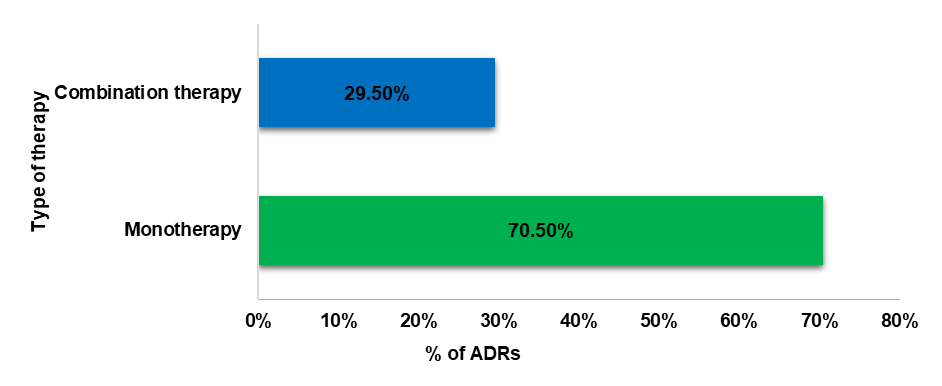

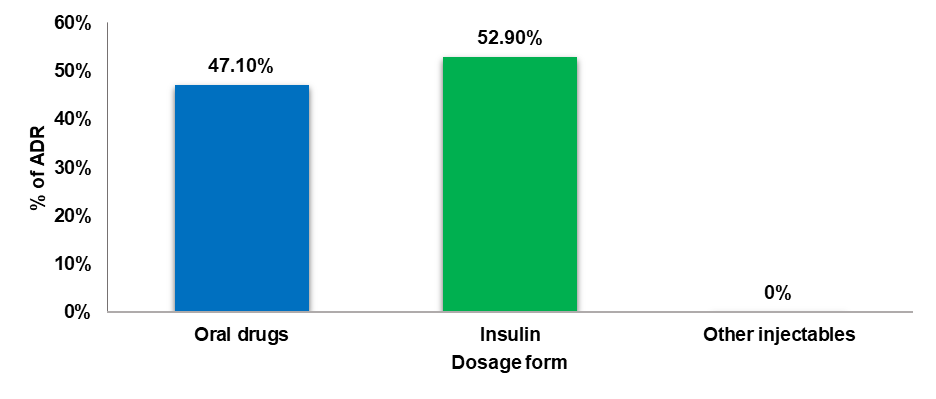

Fig. 4: Type of therapy that caused ADRs

Type of dosage form that caused ADR

The dosage forms that caused ADRs varied distinctly among the study subjects. ADR was higher in patients administered with insulin (52.9%) compared to those given oral medications (47.1%).

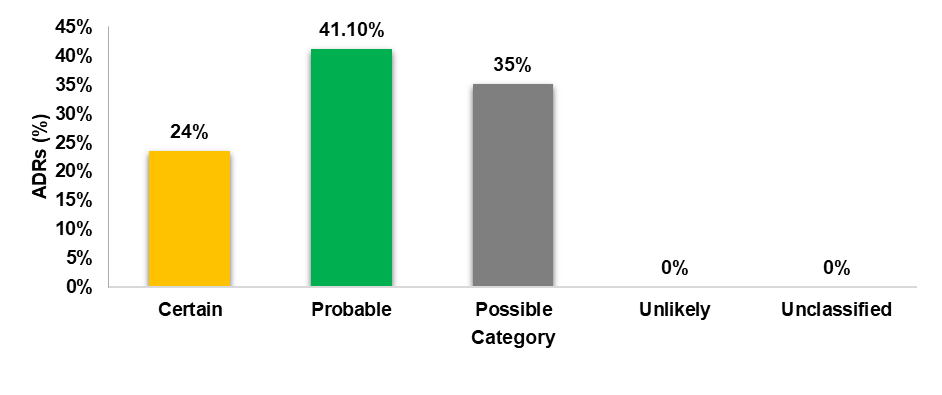

Causality assessment of ADR

Causality assessment by using the WHO scale categorized 41.1% as probable, suggesting a likely causal relationship with the drug administered, 35% as possible, indicating a reasonable likelihood of a causal relationship with the administered drug and 24% as certain, suggesting certainty in determining causality.

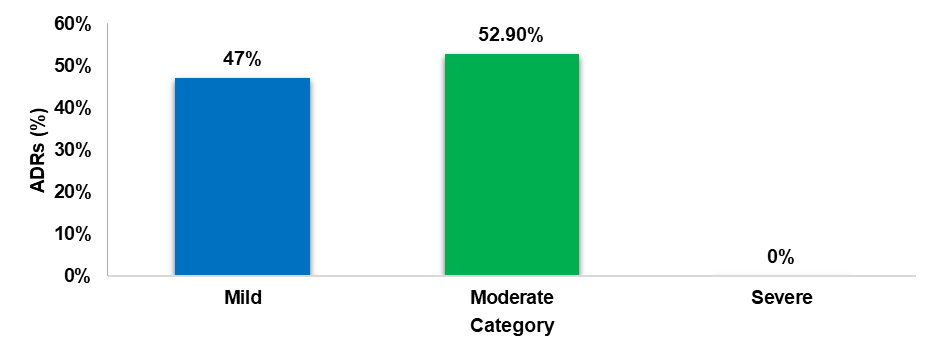

Severity assessment scale

The severity assessment using modified Hartwig and Siegel scale indicated that the majority of the reported ADRs were moderate (52.9%), followed by mild (47%).

Fig. 5: Type of dosage form that caused ADR among the patients

Fig. 6: WHO causality assessment scale

Fig. 7: Severity assessment by modified hartwig and siegel scale

Fig. 8: Preventability assessment by modified schumock and thornton scale

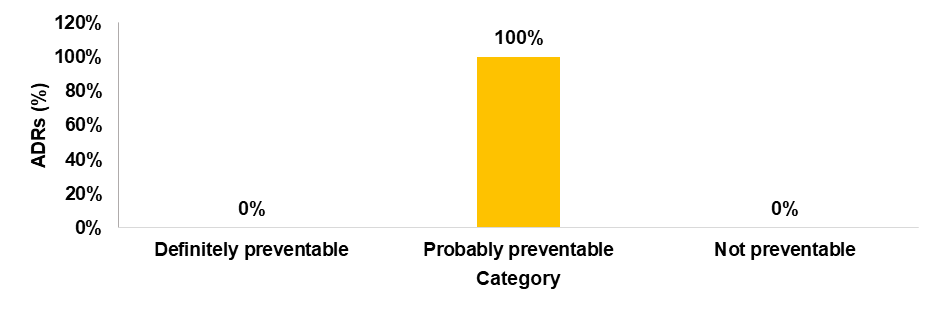

Preventability scale of ADR

The preventability of ADRs was assessed using a modified Schumock and Thornton scale, which revealed that all the reported ADRs were probably preventable.

Incidence of ADR with drugs prescribed

The number of drugs prescribed was compared with the number of ADRs reported in this study. Here, the majority of ADRs were reported with Biguanides (9), but when comparing it with the total number of drugs prescribed (103), the ADR rate (8.7%) concerning Biguanides is less.

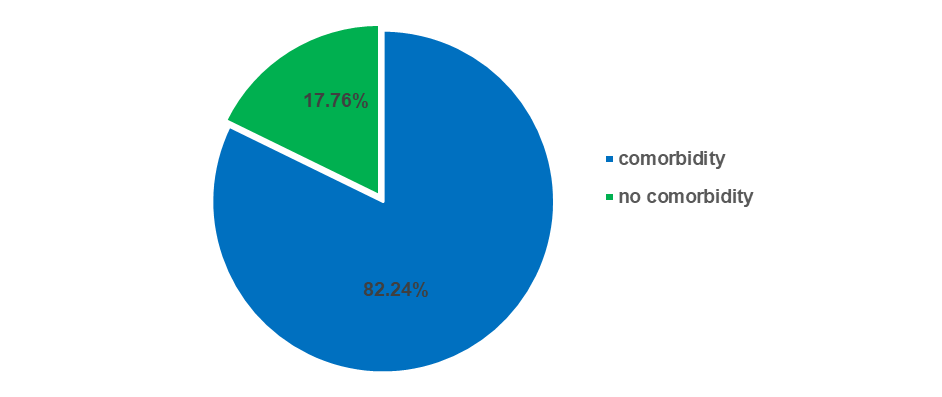

Prevalence of comorbidity in diabetic patients

The study revealed that among the 152 participants, the proportion of diabetic patients with comorbidity conditions is high at 125 (82.24%), while the proportion of diabetic patients without comorbidity conditions is low at 27 (17.76%).

Fig. 9: Prevalence of comorbidity in diabetic patient

Table 6: Age and gender wise distribution of comorbidities

| Patient characteristics (N=152) | With comorbidities n (%) | Without comorbidities n (%) |

| Age | ||

| <40 | 9(5.9%) | 4(2.6%) |

| 40 – 60 | 57(37.5%) | 14(9.2%) |

| >60 | 59(38.8%) | 9(5.9%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 25 (16.4%) | 60(39.4%) |

| Female | 56(36.8%) | 11(7.2%) |

The study revealed that the patients aged>60 y had more comorbidities 59(38.8%), while the aged<40 y had fewer comorbidities 9(5.9%) and the female participants had a higher number of comorbidities 56(36.9%) than males 25(16.4%).

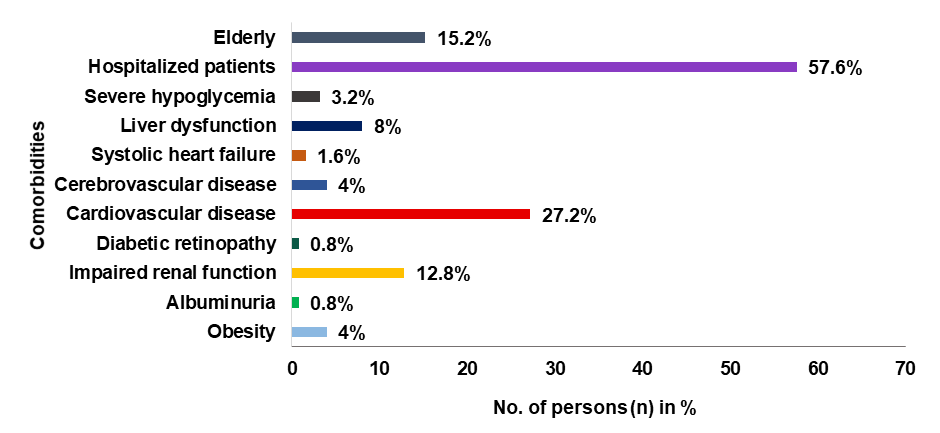

Fig. 10: Prevalence of different comorbidities

Guidelines followed among patients with comorbidities

The study revealed that among participants with comorbidities, treatment for 112 (73.6%) followed the guidelines, while 13(8.5%) did not follow the guidelines.

Assessing the prevalence of comorbidities

Among the 112 (73.6%) patients with comorbidities and with treatment guidelines followed, the comorbid condition with the highest prevalence rate is Hospitalized patients at 57.65% and Albuminuria had the lowest prevalence rate 0.8%.

Cost-minimization of commonly used combination and monotherapy in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus

The present study attempted to conduct the cost-minimization of commonly used combinations and monotherapies in managing type 2 diabetes mellitus. In the context of monotherapies prescribed, biguanides (metformin) and insulin preparations (regular insulin) were the most commonly prescribed monotherapies at 44% and 40% respectively, followed by sulfonylureas and DPP-4 Inhibitors at 13% and 3%. The study found that Biguanide+sulfonylurea (metformin+glimepiride) is the most commonly used combination at 77% followed by Biguanide+DPP-4 inhibitor (metformin+sitagliptin) at 18%. The study also analysed low-cost medications in the prescription and it was found that in monotherapy, only 40% of low-cost alternatives were prescribed, whereas 60% were branded drugs. When analysing combination therapies, the use of low-cost alternatives was much less in percentage, which is only 5 %. As these drugs are formulated by different companies in different brands, the study also had the objective to compare their cost-minimization. It was measured by comparing the monotherapies and combination therapies to their low-cost alternatives/branded generic and Jan Aushadhi scheme counterparts.

Cost-minimization analysis of oral monotherapy drugs prescribed

In monotherapy, the cost-benefit of oral and injectables like insulin was compared separately (table 7). Jan Aushadhi Metformin 500 mg tablets had a percentage benefit of 50.73% compared to branded drugs and 38.71% compared to low-cost alternatives. The study also compared Jan Aushadhi metformin 850 mg which provided a percentage benefit of 61.47% and 43.42% compared to branded and low-cost alternatives, respectively. Comparing sulfonylureas which were prescribed, first the study compared different doses of glimepiride. Jan Aushadhi glimepiride 1 mg had a percentage benefit of 91.28% compared to branded drugs and 88.35% compared to low-cost alternatives. 2 mg tablets of glimepiride from Jan Aushadhi were also beneficial, providing about 91.5% and 81.6% benefits compared to branded and low-cost alternatives, respectively. While comparing Jan Aushadhi gliclazide 80 mg study found benefits of 72.7% compared to branded drugs and 56.5% compared to low-cost alternatives. The study also analysed the benefits of voglibose an alpha-glycosidase inhibitor available in the Jan Aushadhi, which provided a 91.06% benefit compared to branded voglibose but resulted in a 20% loss in Jan Aushadhi voglibose was bought instead of its low-cost alternatives, therefore suggesting that there are instances wherein some branded generics can be cost-effective compared to Jan Aushadhi drugs. The study analysed the benefits of teneligliptin dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor available in the Jan Aushadhi, which provided a 78.4% benefit compared to branded teneligliptin and 39.3% benefit compared to its low-cost alternatives.

Cost-minimization analysis of parenteral monotherapy drugs prescribed

Comparing the benefits of Jan Aushadhi insulin preparations to other branded and low-cost alternatives, the study compared 3 different types to their Jan Aushadhi alternatives (table 8). Firstly, isophane insulin available in Jan Aushadhi provided benefits of 66% compared to branded and low-cost alternatives. Secondly, Regular insulin available in Jan Aushadhi provided a benefit of 60.11% compared to branded and low-cost alternatives. Lastly, insulin glargine in Jan Aushadhi benefitted the patients by 39.82% compared to branded and low-cost preparations. It is to be noted that the doctors prescribed the branded drugs, which themselves were the low-cost alternative, so the benefits compared to branded and low-cost alternatives are the same for all insulin preparations.

Table 7: Cost-minimization analysis of oral monotherapy drugs prescribed

| Cost-minimization of monotherapy (oral) | ||||||||

| Cost-minimization analysis of treatment | ||||||||

| Branded drug(s) | LCA drugs/branded generics | JAS | JAS in INR compared to | JAS in % compared to | ||||

| Drug name | Cost/tablet (INR) | Drug name | Cost/tablet (INR) | Cost/tablet (INR) | Branded drugs | LCA drugs | Branded drugs | LCA drugs |

| A) Biguanide | ||||||||

| i) Metformin – 500 mg | ||||||||

| Wymet | 1.1 | Zomet | 1 | 0.66 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 40% | 34% |

| Matce ER | 1.9 | 1.24 | 0.34 | 65.2% | 34% | |||

| Glyconorm SR | 2.26 | 1.6 | 0.34 | 70.79% | 34% | |||

| mean benefit | 50.73% | 34% | ||||||

| ii) Metformin – 850 mg | ||||||||

| Glycomet | 5.14 | Genericart metformin | 3.5 | 1.98 | 3.16 | 1.52 | 61.47% | 43.42% |

| B) Sulfonylureas | ||||||||

| i) Glimepiride – 1 mg | ||||||||

| GP1 | 4.14 | Genericart glimepiride | 3.78 | 0.44 | 3.77 | 3.34 | 91.06% | 88.35% |

| Glimmy | 3.9 | 0.44 | 3.46 | 3.34 | 88.71% | 88.35% | ||

| Glimer 1 | 4.14 | 0.44 | 3.77 | 3.34 | 91.06% | 88.35% | ||

| mean benefit | 91.28% | 88.35% | ||||||

| ii) Glimepiride – 2 mg | ||||||||

| Amaryl | 6.48 | Isryl 2 | 3 | 0.55 | 5.93 | 2.45 | 91.5% | 81.6% |

| GP2 | 6.49 | 5.94 | 2.45 | 91.5% | 81.6% | |||

| mean benefit | 91.5% | 81.6% | ||||||

| iii) Gliclazide – 80 mg | ||||||||

| Reclide | 8.8 | Glizid | 5.52 | 2.4 | 6.4 | 3.12 | 72.7% | 56.5% |

| C) Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor | ||||||||

| i) Voglibose | ||||||||

| Vogliaid | 3.9 | Vogliter | 1 | 1.2 | 2.7 | -0.2 | 69.2% | -20% |

| D) Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors | ||||||||

| i) Teneligliptin | ||||||||

| Tenstar | 9.3 | Tenlizem | 3.3 | 2.0 | 7.3 | 1.3 | 78.4% | 39.3% |

Abbreviations: LCA-Low-Cost Alternatives, JAS – Jan Aushadhi Scheme, INR – Indian Rupee, %: percentage.

Cost-minimization analysis of oral combination therapy drugs prescribed

For the comparison of combination therapies (Table: 9). combination of glimepiride 1 mg and metformin 500 mg, the mean percentage benefit of using Jan Aushadhi instead of branded drugs and low-cost alternatives was 82.39% and 70.6%, respectively. For combination of glimepiride 2 mg and metformin 500 mg, the mean percentage benefit of using Jan Aushadhi instead of branded drugs and low-cost alternatives was 67%. Similarly, Other prescribed sulfonylurea+metformin combinations, such as glibenclamide and metformin, gliclazide and metformin, and glipizide and metformin, could also provide significant percentage benefits of 54.5%, 30%, and 33.2%, respectively, if Jan Aushadhi drugs are prescribed instead of costly branded alternatives. In the dapagliflozin and sitagliptin combination, the mean benefit of using Jan Aushadhi instead of branded drugs and low-cost alternatives was 69.69% and 60%, respectively. The sitagliptin-metformin combination could provide mean savings of 54.5% and 59.6% when using Jan Aushadhi drugs instead of branded drugs and other low-cost alternatives.

Table 8: Cost-minimization analysis of parenteral monotherapy drugs prescribed

| Cost-minimization of monotherapy (parenteral) | ||||||||

| Cost-minimization analysis of treatment | ||||||||

| Branded drug(s) | LCA drugs/branded generics | JAS | Benefit of JAS in INR, compared to | Benefit of JAS in %, compared to | ||||

| Drug name | Cost/ml (INR) | Drug name | Cost/ml (INR) | Cost/ml (INR) | Branded drug | LCA drug | Branded drug | LCA drug |

| A) NPH/isophane insulin | ||||||||

| Human Mixtard | 26.5 | Human Mixtard* | 26.5* | 0.66 | 9 | 17.5 | 63.03% | 66.03% |

| B) Regular insulin | ||||||||

| Human Actrapid | 17.8 | Human Actrapid* | 17.8* | 7.1 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 60.11% | 60.11% |

| C) Insulin glargine | ||||||||

| Basaalog injection | 188.33 | Basaalog injection* | 188.33* | 113.33 | 75 | 75 | 39.82% | 39.82% |

Abbreviations: LAC-Low-Cost Alternatives, JAS – Jan Aushadhi Scheme, INR – Indian Rupee, *: the drug prescribed is the lowest priced alternative available in the market, %: percentage.

Table 9: Cost-minimization analysis of oral combination therapy drugs

| Cost-minimization of combination therapy (oral) | ||||||||

| Cost-minimization analysis of treatment | ||||||||

| Branded drug(s) | LCA drugs/branded generics | JAS | Benefit of JAS in INR, compared to | Benefit of JAS in %, compared to | ||||

| Drug name | Cost/tablet (INR) | Drug name | Cost/tablet (INR) | Cost/tablet (INR) | Branded drugs | LCA drugs | Branded drugs | LCA drugs |

| A) Biguanide+Sulfonylureas | ||||||||

| i) Metformin+glimepiride – 500 mg+1 mg | ||||||||

| Gepride M1 | 10.3 | Genericart glimepiride+metformin | 6 | 1.76 | 8.54 | 4.24 | 82.91% | 70.6% |

| Glycomet GP 1 | 8.13 | 6.37 | 4.24 | 78.35% | 70.6% | |||

| Glucoryl M1 | 10.6 | 8.84 | 4.24 | 83.3% | 70.6% | |||

| Gluformin G1 | 11.8 | 10.04 | 4.24 | 85.0% | 70.6% | |||

| mean benefit | 82.39% | 70.6% | ||||||

| ii) Metformin+glimepiride – 500 mg+2 mg | ||||||||

| Matce G2 | 5.45 | Matce G2* | 5.45* | 1.76 | 3.69 | 3.69 | 67.7% | 67.7% |

| iii) Glibenclamide+Metformin – 500 mg+5 mg | ||||||||

| Glinil-M | 3.44 | Glibamide M | 2.45 | 1.2 | 2.24 | 1.25 | 65.4% | 51% |

| iv) Gliclazide+Metformin – 500 mg+60 mg | ||||||||

| Gzide M | 4.3 | Gzide M* | 4.3* | 3.0 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 30% | 30% |

| v) Glipizide+Metformin – 500 mg+5 mg | ||||||||

| Glirum MF | 4.3 | Gzide M* | 4.3* | 0.9 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 10.8% | 10.8% |

| Glynase MF | 1.13 | 0.11 | 55.6% | 10.8% | ||||

| mean benefit | 33.2% | 10.8% | ||||||

| B) Biguanide+Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors | ||||||||

| i) metformin+sitagliptin – 500 mg+50 mg | ||||||||

| Sitasmart-M | 20.5 | Sitaday M | 10.89 | 6.5 | 14 | 4.39 | 68.29% | 40.31% |

| Siabite M | 11.9 | 6.5 | 5.4 | 4.39 | 45.37% | 40.31% | ||

| Glura M | 13.2 | 6.5 | 6.7 | 4.39 | 50.0% | 40.31% | ||

| mean benefit | 54.5% | 40.31% | ||||||

| C) Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors+Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors | ||||||||

| i) Sitagliptin+Dapagliflozin – 100 mg+10 mg | ||||||||

| Sitadapa | 16.9 | Genricart sitagliptin+dapagliflozin | 16 | 7 | 9.9 | 9 | 58.5% | 56.2% |

| Dapavel S | 19.8 | 7 | 12.8 | 9 | 64.6% | 56.2% | ||

| mean benefit | 61.5% | 56.2% | ||||||

Abbreviations: LCA-Low-Cost Alternatives, JAS – Jan Aushadhi Scheme, INR – Indian Rupee, *: the drug prescribed is the lowest priced alternative available in the market. %: percentage.

DISCUSSION

In the ever-changing field of managing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), this study compares the effectiveness of antidiabetic combination therapy and monotherapy. The need for a nuanced understanding of various treatment modalities to optimize patient outcomes is highlighted by the growing global burden of type 2 diabetes. A quantitative evaluation of glycaemic control sheds light on the differing efficacies of these therapeutic modalities in addition to safety and efficacy. When making healthcare decisions, it is essential to prioritize patient safety and tolerability by having a thorough understanding of the frequency of adverse effects linked to various treatments.

The most prevalent anti-diabetic therapy was monotherapy either with OHA or insulin, while combination therapy with OHA and insulin was to a lesser extent. A study by Agarwal et al. has documented good glycemic control on monotherapy, however, in our study, combination therapy achieved good glycemic control, an association of glycemic control with monotherapy and combination therapy was found out using statistically significant chi-square test (p<0.05) [17].

The study strongly highlights the domination of OHA but documents a shifting trend towards insulin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes and the need for periodic blood glucose monitoring in patients receiving anti-diabetic drug treatment to identify inadequately controlled glycemic levels so that drug therapy can be intensified and multiple drug interventions can be planned in order to obtain an optimal glycemic level. Consider integrating lifestyle modifications alongside prescribed anti-diabetic medications to enhance glycemic control in type 2 diabetes [17].

In the present study, OHAs were commonly prescribed drugs, accounting for 62% of the total prescribed anti diabetic products. Biguanide (44%) were the most commonly prescribed class, followed by sulfonylureas (13%) and their FDC (fixed drug combination) accounted for 77%. This reflects that sulfonylureas and biguanides are the choice of most physicians in the treatment of type 2 diabetes [17]. However, there is no association between glycemic control and among the different class drugs (p>0.05).

The present study was conducted among 152 T2DM patients comprising of more male patients than female. Out of 17 reported ADRs, males reported ADRs at a higher rate than females. Patients over the age of 60 y suffered the highest percentage of ADRs, which is consistent with a study by Bhattacharjee et al. [19].

The study further unveiled a higher incidence of undesirable effects associated with mono-therapy compared to combination therapy. These findings are parallel with the outcomes reported by Abhishank Singh et al. [27] wherein mono therapy exhibited a significantly greater occurrence of adverse effects than combination therapy. Individual variability in drug metabolism and response further contributes to the complexity, emphasizing the need for careful risk assessment and monitoring in clinical practice.

Regular Insulin and Metformin were the anti-diabetic drugs that were prescribed most frequently and they also showed a higher number of ADRs. However, when the medicine's safety was examined, only 9 ADRs were recorded out of 103 individuals who were taking Metformin and 8 ADRs were reported among 57 patients taking Insulin. This finding is comparable to research done by Tirthankar Debet et al. [20].

The WHO Causality Evaluation scale was used to examine causality to strengthen and emphasize the study's validity. According to the assessment, majority of them were probable and possible. These results were in line with the research conducted by Javedh S et al. [21]. which found that the majority of ADRs fall into the probable category.

The majority of ADRs reported in the study were moderate, followed by mild, based on the Hartwig and Siegel scale used to evaluate the severity of ADRs. This is in contrast to the study by Rajesh et al. [22], which showed that majority of ADRs were mild followed by moderate and then severe. By using the modified Schumock and Thornton scale, the preventability of the ADRs was assessed, it was shown that all the reported ADRs were probably preventable, which is consistent with a study by Keezhipadathil J [13].

As the study examined the safety of the medications, Metformin is more frequently prescribed and regarded as the safest medication when compared to the more recent pharmacological classes of anti-diabetics because of their reduced ADR rate. This is in accordance with the research conducted by Keezhipadathil J [13].

Diabetic patients with comorbidity conditions is high while the proportion of diabetic patients without comorbidity is low, similar to the study conducted by Ponnachan R et al., [14].

The age and gender-wise distribution of comorbidities revealed notable disparities in comorbidity rate based on age and gender. Patients aged over 60 y exhibited a higher prevalence of comorbidities compared to those under 40 y. Similarly, female participants had a higher frequency of comorbidities than males, similar to the study conducted by Ponnachan R et al. [14]

The study revealed a notable difference in adherence to guidelines between patients with and without comorbidities where the majority adhered to the guidelines, whereas a small fraction did not. In contrast, for all patients without comorbidities, the majority adhered to guidelines without deviation, similar to the study conducted by Tschope et al. [15]

Hospitalized patients had the highest prevalence of comorbid conditions, whereas albuminuria had the lowest prevalence. It was found that the high prevalence of comorbid conditions among the participants raises important considerations for healthcare providers and policymakers. Participants' data was distributed based on comorbid conditions. Cardiovascular problem was found to be the comorbidity with the highest frequency followed by impaired renal function, elderly, and liver dysfunction and thereby underscores the complexity of managing patient care in real-world settings. Healthcare professionals need to be equipped to address not only individual conditions but also the interactions and implications of comorbidities on overall health outcomes, which is consistent with a study by Pati S et al. [11]

The findings of the present study revealed that a large majority of respondents adhere to guidelines for managing comorbid conditions. Overall, the results emphasize the importance of comprehensive care for individuals with comorbid conditions. Healthcare systems must prioritize the integration of guidelines into clinical practice, promote interdisciplinary collaboration among healthcare providers, and empower patients to actively participate in their care management. By addressing these challenges, healthcare providers can enhance the quality of care delivery and improve health outcomes for individuals with complex health needs.

Overall, these research findings underscore the significance of comprehensively understanding and effectively managing comorbidities in healthcare practice. By addressing the high prevalence of multiple health issues and promoting adherence to guidelines, healthcare providers have the opportunity to enhance patient care and ultimately improve the overall health outcomes for individuals with comorbid conditions.

The study findings show that metformin alone and metformin plus glimepiride were the most commonly used oral therapies, Glimepiride and metformin drugs are widely prescribed for effective blood glucose control due to their capability of counteracting insulin secretion disorder and insulin resistance, respectively [23]. Insulin preparations were the most commonly used parenteral drugs because elderly patients often require insulin due to advanced disease stages and reduced pancreatic function, as it provides effective and adjustable glucose control. The study's findings highlight the substantial cost benefits of prescribing Jan Aushadhi anti-diabetic medications over both branded and low-cost generic alternatives. through the cost-benefit analysis, it was noted that prescribing Jan Aushadhi drugs provided significant economic benefits compared to branded drugs that were prescribed to the patients already or even when compared to low-cost alternatives available in the market as noted by Chaudhary et al. [24]

It shows that prescribing Jan Aushadhi anti-diabetic drugs can lower treatment costs, allowing patients to manage chronic illnesses like type 2 diabetes mellitus at a lower cost. This cost-minimization may improve access to essential drugs, which could lead to better health outcomes and less financial strain on patients in need of these drugs. However, the study found that the price of one generic drug available under the Jan Aushadhi scheme is costlier than the corresponding branded generic drug available in the market al. so noted by Mukherjee et al. [25] Certain Jan Aushadhi generics may be costlier than branded generics due to pricing based on top branded equivalents, along with additional distribution and store incentive costs. The study noted few percent of the drugs prescribed in both monotherapy and combination therapy were low-cost drugs instead of expensive branded drugs which could be important for medicines like anti-diabetic drugs which are to be taken lifetime. Patients, particularly those over 60, face substantial financial burdens. This age group often has fixed incomes, making the high cost of medication challenging. Prescribing low-cost alternative drugs can significantly alleviate their financial strain, ensuring better adherence and improved health outcomes. Expensive diabetes medication lead to decreased adherence among patients, particularly those with limited incomes, resulting in poorer health outcomes and increased complications [26].

CONCLUSION

This study highlights that combination therapy achieves better glycemic control than monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), emphasizing the value of consistent glucose monitoring to enable timely therapeutic adjustments. Although adverse drug reactions remain an important consideration, metformin demonstrates the most favourable safety profile, with clinical pharmacists contributing significantly to ADR detection and adherence support. The frequent occurrence of comorbidities in this population reinforces the need for strict adherence to evidence-based guidelines to optimize outcomes in complex cases. From an economic standpoint, the use of affordable Jan Aushadhi formulations enhances treatment accessibility and reduces costs, particularly benefiting older adults and patients with limited financial means, thereby promoting more equitable diabetes management.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Ganga S, Shareef S, Tadvi N, Siddiqua S. A comparative study of efficacy and adverse effects of monotherapy with combination therapy for oral anti-diabetics in diabetes mellitus type 2 patients. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2021;11(6):1-5. doi: 10.5455/njppp.2021.11.01021202126012021.

Samya V, Shriraam V, Jasmine A, Akila GV, Anitha Rani M, Durai V. Prevalence of hypoglycemia among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a rural health center in South India. J Prim Care Community Health. 2019;10:2150132719880638. doi: 10.1177/2150132719880638, PMID 31631765.

Tripathy JP, Sagili KD, Kathirvel S, Trivedi A, Nagaraja SB, Bera OP. Diabetes care in public health facilities in India: a situational analysis using a mixed methods approach. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019;12:1189-99. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S192336, PMID 31410044.

Xie X, Wu C, Hao Y, Wang T, Yang Y, Cai P. Benefits and risks of drug combination therapy for diabetes mellitus and its complications: a comprehensive review. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1301093. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1301093, PMID 38179301.

Wu D, Li L, Liu C. Efficacy and safety of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and metformin as initial combination therapy and as monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(1):30-7. doi: 10.1111/dom.12174, PMID 23803146.

Ji L, Chan JC, Yu M, Yoon KH, Kim SG, Choi SH. Early combination versus initial metformin monotherapy in the management of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: an East Asian perspective. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(1):3-17. doi: 10.1111/dom.14205, PMID 32991073.

Gao W, Dong J, Liu J, Li Y, Liu F, Yang L. Efficacy and safety of initial combination of DPP‐IV inhibitors and metformin versus metformin monotherapy in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obesity Metabolism. 2014;16(2):179-85. doi: 10.1111/dom.12193.

Ramachandran V, Ambady R, Joshi S. Current status of diabetes in India and need for novel therapeutic agents. JAPI. 2021;58:7-9.

Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). Guidelines for management of type 2 diabetes 2018. New Delhi: ICMR; 2018. Available from: https://main.icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/guidelines/icmr_guidelinestype2diabetes2018_0.pdf. [Last accessed on 04 Nov 2025].

Davis HA, Spanakis EK, Cryer PE, Davis SN. Hypoglycemia during therapy of diabetes. MDText.com; 2021. Available from: https://www.endotext.org/chapter/hypoglycemia‑during‑therapy‑of‑diabetes/.

Pati S, Schellevis FG. Prevalence and pattern of co-morbidity among type 2 diabetics attending urban primary healthcare centers at Bhubaneswar (India). PloS One. 2017;12(8):e0181661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181661, PMID 28841665.

Nagarathna R, Madhava M, Patil SS, Singh A, Perumal K, Ningombam G. Cost of management of diabetes mellitus: a pan India study. Ann Neurosci. 2020;27(3-4):190-2. doi: 10.1177/0972753121998496, PMID 34556959.

Keezhipadathil J. Evaluation of suspected adverse drug reactions of oral anti-diabetic drugs in a Tertiary Care Hospital for type II diabetes mellitus. Indian J Pharm Pract. 2019;12(2):103-10. doi: 10.5530/ijopp.12.2.23.

Ponnachan R, Babu B, Yesodhar S, Utangi S. Drug utilization evaluation of anti-diabetics in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with or without comorbidities in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital. J Young Pharm. 2021;13(3):267-9. doi: 10.5530/jyp.2021.13.54.

Tschope D, Hanefeld M, Meier JJ, Gitt AK, Halle M, Bramlage P. The role of co-morbidity in the selection of antidiabetic pharmacotherapy in type-2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12(1):62. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-12-62, PMID 23574917.

Mamatha J, Palatty P, Sachendran D, Vijendra R, Baliga M. Financial benefit of antidiabetic drugs available at Jan Aushadhi (people’s drug) stores to geriatric pensioners: a pilot study from India. Hamdan Med J. 2022;15(2):66. doi: 10.4103/hmj.hmj_64_21.

Agarwal AA, Jadhav PR, Deshmukh YA. Prescribing pattern and efficacy of anti-diabetic drugs in maintaining optimal glycemic levels in diabetic patients. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2014;5(3):79-83. doi: 10.4103/0976-0105.139731, PMID 25278671.

Babu A, Mehta A, Guerrero P, Chen Z, Meyer PM, Koh CK. Safe and simple emergency department discharge therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and severe hyperglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(7):696-704. doi: 10.4158/EP09117.ORR, PMID 19625243.

Bhattacharjee A, Gupta MC, Agrawal S. Adverse drug reaction monitoring of newer oral anti diabetic drugs-a pharmacovigilance perspective. Int J Pharmacol Res. 2016;6(4):142-51.

Tirthankar D, Abhik C, Abhishek G. Adverse drug reactions in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients on oral antidiabetic drugs in a diabetes outpatient department of a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in the Eastern India. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2017;6(3):554-7. doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2017.0423203102016.

Javedh S, Jennifer F, Laxminarayana S, Shifaz AK. A study on adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients with diabetes mellitus in a multi-specialty teaching hospital. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;9(2):114-7.

Rajesh R, Ramesh M, Parthasarathi G. A study on adverse drug reactions related hospital admission and their management. Indian J Hosp Pharm. 2008;45:143-8.

Sahay RK, Mittal V, Gopal GR, Kota S, Goyal G, Abhyankar M. Glimepiride and metformin combinations in diabetes comorbidities and complications: real-world evidence. Cureus. 2020;12(9):e10700. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10700, PMID 33133865.

Chaudhary RK, Philip MJ, Santhosh A, Karoli SS, Bhandari R, Ganachari MS. Health economics and effectiveness analysis of generic anti-diabetic medication from Jan Aushadhi: an ambispective study in community pharmacy. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15(6):102303. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.102303, PMID 34626923.

Mukherjee K. A cost analysis of the Jan Aushadhi scheme in India. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2017;6(5):253-6. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.02, PMID 28812812.

Polonsky WH, Henry RR. Poor medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: recognizing the scope of the problem and its key contributors. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1299-307. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S106821, PMID 27524885.

Singh A, Dwivedi S. Study of adverse drug reactions in patients with diabetes attending a Tertiary Care Hospital in New Delhi, India. Indian J Med Res. 2017 Feb;145(2):247-9. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_109_16, PMID 28639602.