Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 17, Issue 6, 128-132Original Article

STUDY OF ASSESSMENT OF CLINICAL PROFILE AND ETIOLOGY OF PATIENTS OF SEVERE ANEMIA ADMITTED AT TERTIARY CARE CENTER

BEHLOOL JOHAR1*, PRATEEK TIWARI2, MANJULA GUPTA1, NIKHIL GUPTA1, SIMMI DUBE1

1Department of General Medicine, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, India. 2Department of Oncology, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, India

*Corresponding author: Behlool Johar; *Email: behlool.j@gmail.com

Received: 14 Aug 2025, Revised and Accepted: 10 Oct 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: To study the clinical profile, determine aetiological factors, and assess contributing variables among patients with severe anaemia in a tertiary care setting in Central India.

Methods: This observational study was conducted over one year (March 2024–February 2025) at Gandhi Medical College and Associated Hospitals, Bhopal. A total of 150 adult patients with haemoglobin<7 g/dl and undiagnosed anaemia were enrolled. Patients underwent detailed clinical evaluation and comprehensive laboratory investigations.

Results: Females comprised 64.7% of the cohort, with a mean age of 53.91±21.62 y. Pallor (100%) and dyspnoea (100%) were universal symptoms. Nutritional anaemia was the predominant cause (83.33%), with iron deficiency anaemia accounting for 60%, followed by vitamin B12 deficiency (20%). Other causes included leukaemia (7.3%), haemoglobinopathies (4.7%), haemolytic anaemia (2.6%), infections (1.3%), and aplastic anaemia (0.7%). mean haemoglobin was 4.47±1.51 g/dl. SGPT levels varied significantly with anaemia severity (p=0.013), while MCV approached significance (p=0.051), indicating hepatic stress and microcytosis in severe cases.

Conclusion: Severe anaemia in hospitalized adults is predominantly nutritional in origin, underscoring the need for early detection, nutritional interventions, and public health strategies. Focused community screening and comprehensive management protocols are vital to reduce the anaemia burden and its complications.

Keywords: Severe anaemia, Iron deficiency anaemia, Nutritional anaemia, Haemoglobin, Aetiology, India, Hospital-based study, Vitamin B12, Public health, Clinical profile

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2025v17i6.8014 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijcpr

INTRODUCTION

Anaemia is a global public health problem affecting individuals of all age groups, genders, and socioeconomic strata [1, 2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), anaemia is defined as a condition in which the number of red blood cells (RBCs) or their haemoglobin concentration (oxygen-carrying capacity) is insufficient to meet physiological demands, varying by age, sex, altitude, smoking, and pregnancy status [3]. WHO classifies anaemia based on haemoglobin levels, with thresholds of<13 g/dl for men, <12 g/dl for nonpregnant women, and<11 g/dl for pregnant women [2, 4, 5].

India accounts for a significant share of the global anaemia burden. Factors such as poverty, malnutrition, limited health education, and a high prevalence of infectious diseases exacerbate the issue [6]. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), anaemia affects 57.2% of women aged 15-49 y, 25% of men, and 67.1% of children under the age of 5 [7]. Despite being preventable and treatable, anaemia remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in India, particularly among vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, young children, and the elderly [8-10].

Severe anaemia represents an advanced stage of the condition, where the physiological consequences are more pronounced and potentially life-threatening [11]. Clinically, severe anaemia manifests with a constellation of symptoms, including generalized weakness, fatigue, pallor, dyspnoea, palpitations, and, in extreme cases, cardiovascular collapse. Chronic severe anaemia leads to compensatory mechanisms such as tachycardia and left ventricular hypertrophy, which may result in heart failure if untreated. Additionally, it impairs immunity, predisposing patients to infections, and adversely impacts cognitive and physical performance, thus reducing the quality of life [12].

Anaemia has a multifactorial aetiology requiring a comprehensive evaluation to identify underlying causes. It is broadly categorized into nutritional deficiencies, such as iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) from inadequate intake or chronic blood loss, and megaloblastic anemia due to vitamin B12 or folate deficiency. Hemolytic anemia results from increased RBC destruction, either inherited (e. g., sickle cell anaemia) or acquired (e. g., malaria). Anaemia of chronic disease (ACD) arises in conditions like infections or autoimmune disorders, where inflammatory cytokines disrupt erythropoiesis. Bone marrow disorders, including aplastic anaemia and leukaemia, lead to impaired RBC production. Other causes include acute or chronic blood loss, parasitic infections, genetic disorders, and toxic exposures [13].

Several factors contribute to the progression from mild or moderate anaemia to severe anaemia. These include delayed diagnosis, lack of access to timely medical care, cultural and socioeconomic barriers, and comorbid conditions such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) or HIV/AIDS. Anaemia accounts for 9% of the global disability burden, adversely impacting work productivity, learning abilities, and cognitive function, with far-reaching effects on health, economic growth, and social progress [14].

Understanding the clinical profile and aetiology of severe anaemia is crucial for targeted interventions, as it helps identify symptoms, complications, and root causes, enabling effective treatment and prevention strategies. Tertiary care hospitals provide a unique setting for studying severe anaemia due to their advanced diagnostic facilities and multidisciplinary management of complex cases. This study aims to document the clinical profile, categorize aetiologies, and evaluate factors contributing to severe anaemia in Central India, addressing gaps in knowledge and guiding public health initiatives. The findings are expected to inform interventions such as public health campaigns, early diagnosis programs, and improved healthcare access, contributing to better management of anaemia and reducing its burden in the region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted as an observational study on adult patients admitted with a clinical and laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of severe anaemia (<7 g/dl) in the Department of Medicine, Gandhi Medical College and Associated Hospitals (Hamidia Hospital), Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, during the study period of 1 y i. e. from 1st March 2024 to 28th February 2025. All adult patients aged 18 y or above, with haemoglobin level of less than 7 g/dl and with undiagnosed causes of severe anaemia were included, whereas patients with known renal failure who were already on treatment, already been diagnosed and are on treatment elsewhere for anaemia, pregnant women, post-traumatic cases and anaemia due to acute hemorrhage were excluded.

Prior to initiating the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC), Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal. After obtaining written informed consent, each patient underwent a thorough clinical evaluation, including presenting complaints, past medical history, transfusion history, dietary history, personal habits, and family history. General physical examination was done, which included evaluation of vital signs and signs of anaemia and other comorbidities. Systemic examination with emphasis on cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and central nervous systems was also done and findings were documented in a pre-designed semi-structured proforma. All patients underwent the investigations as per standard clinical protocol, which included complete blood count (CBC), reticulocyte count, peripheral blood smear examination, liver function tests (LFTs), renal function tests (RFTs), random blood sugar (RBS), serum iron profile, vitamin B12, and folate levels, Hemoglobin electrophoresis to identify hemoglobinopathies and bone marrow aspiration/biopsy where indicated. Other investigations, such as ultrasonography, viral markers and other additional relevant tests based on clinical judgment, were done and findings were documented.

Statistical analysis

The data was compiled using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using Epi Info 7.0software. Descriptive statistics such as mean, median, standard deviation, and frequency were used. To test the level of significance and associations, one-way ANOVA was applied. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

This study was conducted on a total of 150 patients with severe anemia admitted in medical ICU.

Table 1: Distribution of patients according to baseline variables

| Baseline variables | Number of patients (n=150) | Percentage | |

| Gender | Male | 53 | 35.3 |

| Female | 97 | 64.7 | |

| Age (years) | 18-30 | 28 | 18.66 |

| 31-60 | 42 | 28 | |

| 61-90 | 80 | 53.33 | |

| Clinical signs | Pallor | 100 | 100 |

| Fever | 74 | 49.33 | |

| Oedema | 90 | 60 | |

| Icterus | 20 | 13.33 | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 10 | 6.66 | |

| Pulmonaryedema | 10 | 6.66 | |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | 13 | 8.77 | |

| Tachycardia | 66 | 44 | |

| Dyspnea | Grade 1 | 0 | |

| Grade2 | 0 | ||

| Grade3 | 105 | ||

| Grade4 | 45 |

In our study, the majority i. e. 97 (64.7%) cases were females and the mean age of patients was 53.91±21.62 y. Majority of participants (53.33%) belonged to the age group of 61-90 y, followed by those in 31-60 y age group (28%). Pallor and dyspnea (grade 3 and grade 4) were present in all cases, with severe anemia and oedema was present in 60% cases, icterus in 13.33% cases and hepatosplenomegaly in 8.77% cases (table 1).

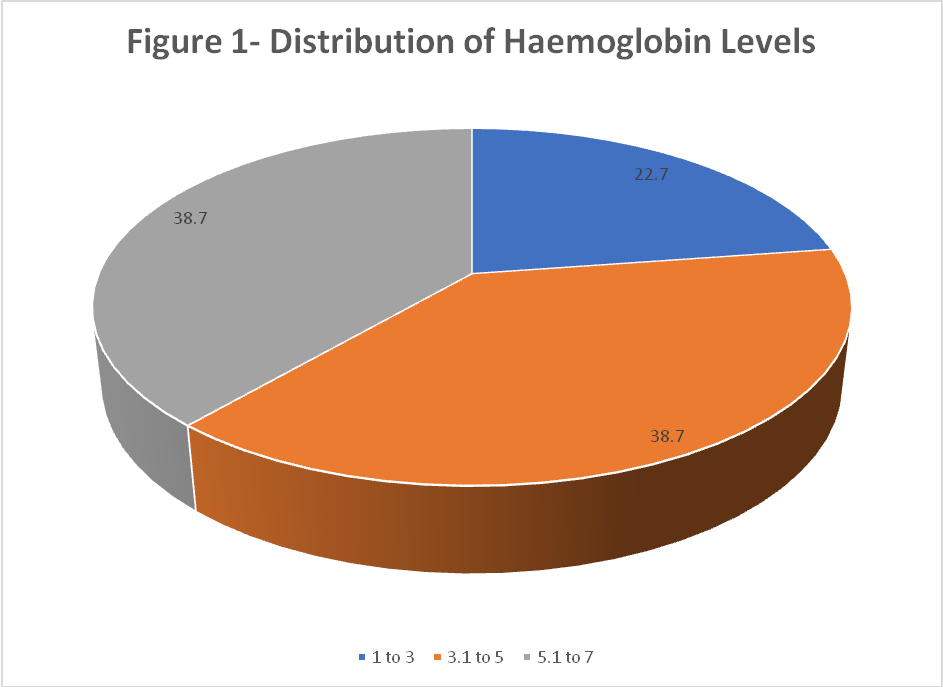

About 22.7% had critically low hemoglobin between 1–3g/dl, while38.7%eachhad hemoglobin in the range of 3.1–5 g/dland5.1–7 g/dl. The mean hemoglobin level was alarmingly low at 4.47±1.51 g/dl (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Distribution of heamoglobin levels

Majority of the study participants had nutritional anaemia (83.33%), most common being iron deficiency anaemia (60%), followed by Vitamin B12 deficiency (20%). Leukaemia attributed to 7.33% cases of severe anemia. Haemoglobinopathies were seen in 4.7% (sickle cell anemia with or without nutritional deficiencies), while 2.6% had hemolytic anemia-autoimmune hemolytic anemia (0.7%) and G6PD deficiency (0.7%). 1.33% had infections (malaria) and 0.66% had aplastic anaemia (table 2).

Table 2: Etiological factors of severe anaemia cases

| Classification | n | % | Sub classification | n | % |

| Nutritional | 125 | 83.3 | Iron deficiency anemia | 90 | 60 |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency anemia | 30 | 20.0 | |||

| Folate deficiency | 3 | 2.0 | |||

| Folate and iron deficiency anemia | 2 | 1.3 | |||

| Hemoglobinopathy | 7 | 4.7 | Sickle cell anemia | 5 | 3.3 |

| Iron deficiency anemia with sickle cell anemia | 2 | 1.3 | |||

| Hemolytic | 4 | 2.6 | G6PDdeficiency | 1 | 0.7 |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 3 | 2.0 | |||

| Leukemia | 11 | 7.3 | Leukemia | 11 | 7.3 |

| Aplastic Anemia | 1 | 0.7 | Aplastic anemia | 1 | 0.7 |

| Infections | 2 | 1.3 | Malaria | 2 | 1.3 |

Table 3: Biochemical and hematological parameters

| Parameter | Min | Max | Mean±SD |

| TLC (percumm) | 1034 | 182893 | 23685.29±43443.41 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 30.0 | 97.0 | 70.23±7.48 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 3.00 | 60.00 | 24.98±9.26 |

| Eosinophils (%) | .00 | 7.00 | 4.54±1.56 |

| Basophils (%) | .00 | 5.00 | 2.4440±1.50 |

| Platelets (percumm) | 6829 | 509400 | 175300.40±125850.99 |

| SGOT (U/l) | 10.10 | 39.80 | 24.64±8.82 |

| SGPT (U/l) | 10.10 | 39.80 | 25.24±8.87 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | .40 | 3.90 | 1.2067±0.72 |

| Indirect Bilirubin (mg/dl) | .10 | 3.50 | 0.69±0.55 |

| TSH (mIU/l) | .60 | 4.90 | 2.87±1.29 |

| T3 (ng/dl) | 1.10 | 3.00 | 1.98±0.57 |

| T4 (mcg/dl) | 4.50 | 12.00 | 8.32±2.29 |

| Serum LDH(U/l) | 140.80 | 1024.00 | 235.93±136.77 |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/ml) | 27.70 | 1971.70 | 960.61±642.84 |

| Folic acid (ng/ml) | .40 | 16.80 | 9.22±4.40 |

| MCV (fL) | 48.00 | 118.00 | 78.97±17.65 |

| MCH (pg) | 17.90 | 33.00 | 29.38±2.42 |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 23.30 | 36.00 | 33.76±1.70 |

| Serum Iron (µg/dl) | 14.70 | 169.70 | 70.15±42.15 |

| Ferritin(ng/ml) | 0.9 | 297.20 | 37.51.±69.48 |

| Reticulocyte count (%) | 1.50 | 2.50 | 1.97±0.30 |

Table 4: Association of severity of anemia with various factors

| Variable | Hemoglobin(gm/dl) | P-value | ||

| 1-3 (Mean±SD) | 3.1-5 (Mean±SD) | 5.1-7 (Mean±SD) | ||

| Age | 54.59±21.02 | 55.40±21.96 | 52.02±21.85 | 0.225 |

| TLC(/cumm) | 19656.44±37922.59 | 29492.84±51441.30 | 20239.48±37399.86 | 0.795 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 71.72±7.90 | 69.97±6.37 | 69.62±8.23 | 0.693 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 25.66±9.44 | 24.33±8.68 | 25.22±9.82 | 0.717 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 4.45±1.80 | 4.46±1.54 | 4.66±1.54 | 0.769 |

| Basophils (%) | 2.57±1.56 | 2.58±1.40 | 2.24±1.55 | 0.391 |

| Platelets (/cumm) | 163549.29±124696.85 | 181476.53±129653.94 | 176012.84±124371.43 | 0.883 |

| SGOT(U/l) | 26.81±9.04 | 24.95±9.15 | 23.06±8.18 | 0.136 |

| SGPT (U/l) | 29.26±9.12 | 23.75±8.96 | 24.38±8.04 | 0.013 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.13±0.64 | 1.30±0.80 | 1.16±0.69 | 0.711 |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.72±0.53 | 0.68±0.60 | 0.68±0.52 | 0.864 |

| TSH (mIU/l) | 2.70±1.14 | 2.84±1.41 | 2.99±1.26 | 0.504 |

| T3 (ng/dl) | 1.93±0.60 | 1.89±0.52 | 2.09±0.60 | 0.161 |

| T4 (mcg/dl) | 8.48±2.30 | 8.34±2.37 | 8.20±2.24 | 0.854 |

| Serum LDH(U/l) | 243.19±172.55 | 242.35±150.48 | 225.25±93.95 | 0.856 |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/ml) | 892.61±629.59 | 963.41±666.39 | 997.66±634.44 | 0.733 |

| Folic Acid (ng/ml) | 9.04±4.62 | 9.17±4.24 | 9.37±4.50 | 0.946 |

| MCV (fL) | 72.60±16.32 | 80.02±18.06 | 81.66±17.36 | 0.051 |

| MCH (pg) | 29.66±2.27 | 29.36±2.84 | 29.23±2.05 | 0.523 |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 33.87±1.29 | 33.49±1.98 | 33.98±1.60 | 0.221 |

| Serum Iron (µg/dl) | 68.78±43.84 | 70.65±41.19 | 70.44±42.83 | 0.804 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 35.59±73.09 | 26.97±56.34 | 50.33±77.86 | 0.143 |

| Reticulocyte count (%) | 1.95±0.30 | 1.96±0.29 | 2.00±0.31 | 0.674 |

Elevated total leukocyte counts and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in some patients hint at underlying infections or haemolytic processes. Low average serum iron (70.15 µg/dl) and ferritin levels (mean 37.51 ng/ml) support iron deficiency as a key aetiology. The mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of 78.97 fL suggests a predominance of microcytic to normocytic anaemia, consistent with iron deficiency. Variable vitamin B12 and folic acid levels point to the presence of nutritional deficiencies. Slightly elevated bilirubin levels support possible haemolysis or hepatic involvement. These findings collectively underline a multifactorial aetiology involving nutritional deficiencies, iron depletion, and mild haemolytic components (table 3).

No statistically significant differences were observed in age, laboratory parameters such as TLC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, basophils, platelet count, SGOT, bilirubin, thyroid hormones, vitamin B12, folic acid, MCH, MCHC, serum iron, or reticulocyte countin cases with varying severity of anemia (p>0.05). However, SGPT showed a statistically significant variation (p=0.013), being slightly higher in the 1–3 g/dl group, suggesting possible hepatic stress in patients with more severe anaemia. Additionally, MCV approached statistical significance (p=0.051), hinting that microcytosis might be more pronounced in severe cases (table 4).

DISCUSSION

Anaemia remains a critical public health challenge in India, disproportionately affecting vulnerable groups such as women, children, and the elderly due to a complex interplay of nutritional deficiencies, infectious diseases, and socioeconomic disparities. Severe anaemia, defined by the World Health Organization as hemoglobin levels below 7 g/dl, is associated with serious clinical manifestations, including fatigue, cardiovascular compromise, and increased susceptibility to infections. Despite the existence of national nutrition programs, the burden of severe anaemia persists, underscoring the need for a deeper understanding of its clinical and etiological landscape. The present study was undertaken to assess the clinical profile of patients with severe anaemia, categorize its underlying causes, and evaluate contributing factors among hospitalized adults.

The mean age in our study was 53.91±21.62 y, indicating that severe anaemia affects a broad age group, particularly older adults. This finding aligns with Dash et al., who reported a mean age of 53.34±17.75 y, and Gara et al., who reported a mean age of 45.82±22.57y, with a predominance of patients in the 61–70 y bracket (32.94%) [15, 16]. Our study showed a clear female predominance (64.7%), similar to findings by Gara et al. (68.24% females) [16] and Aryal et al. (78.2% females) [17]. Pillapalyam et al. also noted that68% of their anaemic patients were female [18]. This trend reflects the gender-based vulnerability to anaemia in India, attributable to menstruation, pregnancy, and nutritional disparities.

In our cohort, pallor and shortness of breath were present in 100% of patients, attributing to the severity of the disease, oedema was observed in 60% of patients,a finding consistent with Gara et al. who reported pedaloedema in 32.94%.[16]Dash et al. observed peripheral oedema in 57.1% of patients.[15] The presence of oedema likely reflects cardiac or renal involvement. Icterus was seen in 13.33% of our patients, which is higher than the 2.6% reported by Aryal et al.[17] and 9% in Pillapalyam et al., [18], suggesting a higher rate of haemolytic or hepatic involvement in our cohort.

Lymphadenopathy was infrequent (6.7%), similar to Reddy et al. (16%) [1] and Dash et al. (2.9%) [15], indicating a relatively low burden of malignancy or infections like tuberculosis. Fever was found in 49.33% of patients, indicating towards ongoing inflammation and easy susceptibility to the infections. Tachycardia was present in 44% patients, indicating towards anemia leading to the hyperdynamic circulation.

The mean haemoglobin in our study was 4.47±1.51 g/dl, underscoring the extreme severity of anaemia among inpatients. This finding is comparable to Dash et al. [15], who reported a mean of 3.7±0.85 g/dl among patients with very severe anaemia, and Gara et al., [16], where 37% had Hb<6.5 g/dl. In contrast, Aryal et al. reported severe anaemia in only 17.1% of their patients, likely due to the broader inclusion criteria [17]. Little et al. also found a higher prevalence of moderate anaemia, particularly among women [19].

Our study revealed a predominance of microcytic to normocytic anaemia (MCV mean=78.97 fL), supported by low serum iron (70.15 µg/dl) and ferritin (37.51ng/ml), indicating iron deficiency. This is in agreement with Dash et al. who reported 58.6% microcytic anaemia [15] Ratre et al. with 59%microcytic hypochromic smears [20]. and Pillapalyam et al. who found 56% microcytic cases [18].

The slight elevation in bilirubin in our patients may point to haemolysis or hepatic dysfunction, similar to observations by Calis et al., who noted bilirubin elevation in the context of malaria and bacterial infections in Malawian children with severe anaemia [21]. Elevated SGPT (p=0.013) in our study suggests possible hepatic involvement, especially in the most anaemic group (Hb 1–3g/dl).

Iron deficiency emerged as the leading cause of severe anaemia in our study (60%), aligning with the findings of Gara et al. (56% of nutritional anaemia cases) [16] and Aryal et al. (59.1% IDA) [17]. Ratre et al. reported 84% nutritional anaemia, predominantly iron deficiency [20].

G6PD deficiency was rare (0.7%) in our cohort, aligning with Dash et al. [15] and Calis et al., [21] who reported it in 13.8% of Malawian children but emphasized its role mainly in malaria-endemic zones. Sickle cell anaemia was seen in 3.3% of our cases, comparable to Dash et al. [15] and Gara et al. [16] who also reported its presence in a minority. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (0.7%) was infrequent in our study, which aligns with the low DCT positivity (2%).

Our study reported 7.33% of anaemia cases due to chronic myeloid leukaemia and 0.66% due to aplastic anomia. This is closely mirrored by Reddy et al. [1] where leukaemia and lymphoma each accounted for 10%, and aplastic anemia contributed to 4%. Similarly, Dash et al. identified aplastic anemia in 1.4%, [15] corroborating our findings.

The presence of malaria in 1.3% of our cases is relatively lower than Reddy et al.,[1] who documented chronic malaria in 8% of their patients, andDash et al., [15], where hookworm and malaria combined contributed significantly to anaemiaaetiologies. A broader perspective is offered by Calis et al., [21] who reported high malaria-related anemia burdens in endemic regions (59.5%) and identifying it as a key contributor to severe anaemia. The relatively low malaria-associated anaemia in our study may be attributed to improved vector control measures and prompt treatment in the study population.

The significant variation in SGPT levels (p=0.013) across haemoglobin strata in our study indicates hepatic stress in severe anaemia, a finding not widely explored in earlier Indian studies but mentioned by Pasricha et al. as apotential contributor to anaemia in systemic illnesses [22].

In conclusion, our study findings largely align with national and regional literature emphasizing nutritional deficiencies—particularly iron and vitamin B12—as predominant causes of severe anaemia. The demographic trends, clinical signs, and lack of significant associations with certain hematological parameters resonate with observations from both older and contemporary studies. However, the relatively high prevalence of hepatic derangements, the low yield of autoimmune and genetic causes, and the exceedingly low mean haemoglobin levels underscore the critical burden and severity in hospitalized patients. These findings warrant targeted public health strategies, improved screening, and comprehensive management protocols, especially for vulnerable groups such as elderly females from low-resource backgrounds.

Our study had certain limitations. The findings are based on data collected from a single tertiary care hospital, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other regions or healthcare settings. Since the study was conducted among admitted patients, it inherently included more severe cases of anaemia and may not reflect the clinical and etiological profile of anaemia in the general community. Being an observational cross-sectional study, it captures patient data at a single point in time and does not provide insights into the long-term outcomes or response to treatment. The study did not include longitudinal follow-up of patients, which restricts understanding of the disease progression and effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

CONCLUSION

Severe anaemia continues to be a significant public health challenge, especially in developing countries like India, where nutritional deficiencies, infectious diseases, and limited access to healthcare play a pivotal role. A significant proportion of cases were attributable to nutritional deficiencies, particularly iron deficiency anaemia, followed by megaloblastic and anaemia of chronic disease. Other causes included haemolytic anaemia, haemoglobinopathies, and bone marrow suppression, though in relatively smaller proportions. This study emphasizes the need for early detection and thorough etiological workup of severe anaemia, which is often preventable and treatable. Delayed diagnosis may not only lead to worsening of clinical status but also predispose patients to avoidable complications. Therefore, an integrated approach encompassing public health awareness, nutritional interventions, and robust diagnostic protocols is crucial to reducing the burden of severe anaemia. From a broader perspective, these findings highlight the importance of reinforcing preventive strategies at both community and hospital levels. Future research should focus on longitudinal follow-up and interventional models to assess the impact of early treatment and policy-level health initiatives in mitigating the long-term consequences of severe anaemia.

FUNDING

Nil

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Declared none

REFERENCES

Reddy VS, Reddy VS. A study of etiological and clinical profile of patients with severe anemia in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Int J Adv Med. 2018 Nov 22;5(6):1422-7. doi: 10.18203/2349-3933.ijam20184750.

FIGO. Iron deficiency and anaemia in women and girls. London: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 2023. Available from: https://www.figo.org/resources/figo-statements/iron-deficiency-and-anaemia-women-and-girls. [Last accessed on 11 Dec 2024].

World Health Organization. Anaemia: overview. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/anaemia. [Last accessed on 12 Dec 2024].

World Health Organization. Guideline on haemoglobin cutoffs to define anaemia in individuals and populations. World Health Organization; 2024 Mar 5.

World Health Organization. Anaemia. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anaemia.

Rai RK, Kumar SS, Sen Gupta SS, Parasannanavar DJ, Anish TS, Barik A. Shooting shadows: India’s struggle to reduce the burden of anaemia. Br J Nutr. 2023 Feb;129(3):416-27. doi: 10.1017/S0007114522000927, PMID 35383547.

National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019–21: India fact sheet. India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Available from: https://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS5_FCTS/India.pdf. [Last accessed on 23 Jun 2024].

Osborn AJ, Muhammad GM, Ravishankar SL, Mathew AC. Prevalence and correlates of anemia among women in the reproductive age (15-49 y) in a rural area of Tamil Nadu: an exploratory study. J Educ Health Promot. 2021 Sep 30;10:355. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1526_20, PMID 34761041.

Kotecha PV. Nutritional anemia in young children with focus on Asia and India. Indian J Community Med. 2011;36(1):8-16. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.80786, PMID 21687374.

Daniel RA, Ahamed F, Mandal S, Lognathan V, Ghosh T, Ramaswamy G. Prevalence of anemia among the elderly in India: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e42333. doi: 10.7759/cureus.42333, PMID 37614252.

Badireddy M, Baradhi KM. Chronic anemia. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534803. [Last accessed on 12 Dec 2024].

Turner J, Parsi M, Badireddy M. Anemia. In: Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499994.

Chaparro CM, Suchdev PS. Anemia epidemiology, pathophysiology and etiology in low and middle-income countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019 Aug;1450(1):15-31. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14092, PMID 31008520.

Lopes SO, Ribeiro SA, Morais DC, Miguel ED, Gusmao LS, Franceschini SD. Factors associated with anemia among adults and the elderly family farmers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jun 16;19(12):7371. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19127371, PMID 35742619.

Dash SC, Sundaray NK, Tudu PK, Rajesh B. A hospital-based study of severe anemia in adults in Eastern India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2018;7(1):114-20. doi: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20185183.

Gara HK, Vanamali DR. Etiological patterns and clinical manifestations of severe anemia in hospitalized patients. Assam J Intern Med. 2024 Jun;14(1):23-30. doi: 10.4103/ajoim.ajoim_10_24.

Aryal D, Ghimire MR, Pandey S, Paudel D, Gaire A. Clinical profile of patients with anemia in a Tertiary Care Hospital. J Univ Coll Med Sci. 2023 Sep 7;11(2):20-4. doi: 10.3126/jucms.v11i02.57984.

Pillapalyam L, Rizwana S. Study of clinical and laboratory profile of anaemia in a Tertiary Care Hospital. ResearchGate. 2023 Mar;22(3):7-9. doi: 10.9790/0853-2203160709.

Little M, Zivot C, Humphries S, Dodd W, Patel K, Dewey C. Burden and determinants of anemia in a rural population in South India: a cross-sectional study. Anemia. 2018 Jul 15;2018:7123976. doi: 10.1155/2018/7123976, PMID 30112198.

Ratre DB, Patel DN, Patel DU, Jain DR, Sharma DV. Clinical and epidemiological profile of anemia in central India. Int J Med Res Rev. 2014;2(1):45-52. doi: 10.17511/ijmrr.2014.i01.09.

Calis JC, Phiri KS, Van Hensbroek MB. Severe anemia in Malawian children: reply. N Engl J Med. 2008 May 22;358(21):2291.

Pasricha SR, Black J, Muthayya S, Shet A, Bhat V, Nagaraj S. Determinants of anemia among young children in rural India. Pediatrics. 2010 Jul 1;126(1):e140-9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3108, PMID 20547647.