Int J Pharm Pharm Sci, Vol 17, Issue 3, 1-9Original Article

INFLUENCE OF PHYSICO-CHEMICAL PARAMETERS ON THE FABRICATION OF SILVER NANOPARTICLES USING MARANTA ARUNDINACEA l AND ITS ANTI-MICROBIAL EFFICACY

V. K. ROKHADE, T. C. TARANATH*

P. G. Department of Studies in Botany, Environmental Biology Laboratory, Karnatak University, Dharwad-580003, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: T. C. Taranath; *Email: tctaranath@rediffmail.com

Received: 08 Jul 2018, Revised and Accepted: 11 Jan 2025

ABSTRACT

Objective: To investigate phytosynthesis of silver nanoparticles, factors governing the synthesis of nanoparticles and antibacterial activity of synthesized silver nanoparticles.

Methods: The leaf extract of Maranta arundinacea L. was used for synthesis of silver nanoparticles which was confirmed by changing the colour of reaction mixture from colourless to brown. Synthesized silver nanoparticles were characterized by UV-vis spectroscopy (UV-vis), Fourier Transform Infra Red Spectrophotometer (FTIR), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Energy dispersive X-ray diffraction (EDX), Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HR-TEM) and testing the antibacterial activity against E. coli, S. typhi, S. aureus and B. polymyxa following well diffusion method.

Results: Silver nanoparticles shows characteristic UV-Vis absorption peak at 406 nm. The influence of physico-chemical parameters was studied and optimized to obtain nanoparticles of diverse sizes. The size of silver nanoparticles ranges from 30 to 90 nm and were found to be spherical in shape with crystalline nature. The synthesized silver nanoparticles showed good antimicrobial activity against multi-drug resistant S. aureus, B. polymyxa, E. coli and Salmonella typhi. Silver nanoparticles show that higher antibacterial activity was observed in Gram negative bacteria than in Gram-positive bacteria. The highest zone of inhibition 7.033±0.033 mm was observed in S. typhi at 250 µl and lowest zone of inhibition 4.100±0.066 mm was seen in B. polymyxa at 250 µl.

Conclusion: Silver nanoparticles synthesized using leaf extract of Maranta arundinacea L. may exhibit reasonable testing antimicrobial activity against some pathogenic microbes.

Keywords: Silver nanoparticles, Maranta arundinacea L, Physico-chemical parameters, Antimicrobial activity

© 2025 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijpps.2025v17i3.28365 Journal homepage: https://innovareacademics.in/journals/index.php/ijpps

INTRODUCTION

Nanotechnology provides the tools and technology platform for the investigation and transformation of biological system which offers inspiration models and bio-assemble components to nanotechnology [1]. Nanoparticles are present at a higher surface-to-volume ratio with decreasing size of nanoparticles. They possess unique optical and electronic properties compared to bulk material. It has been reported that since ancient times silver is known to have antimicrobial [2], antiviral [3], anti-plasmodial [4], anti-inflammatory [5], anti-cancer [6, 7] and anti-diabetic [8] activities. The size, shape and surface morphology play an important role in controlling the physical, chemical, optical and electronic properties of these nanomaterials. Several physical properties of silver nanoparticles, such as Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), can be tailored for specific application by controlling the size, shape and morphology of the nanoparticles [9-11]. The nanoparticles synthesis generally involves either a “top down” or a “bottom up” approach. The bottom up approach mostly relies on chemical and biological methods of production. The problem with most of the chemical and physical methods of nanosilver production is that they are extremely expensive and also involve the use of toxic, hazardous chemicals, which may pose potential environmental and biological risks.

Synthesis of nanoparticles through biological methods is a good alternative over chemical and physical methods as they are environmental friendly and economic. Since past few decades, it was only the prokaryotes that have been exploited for the synthesis of nanoparticles. But recently, it was found that highly evolved organisms like algae, diatoms, plants and other components of eukaryotes also possess the reducing potential to convert the inorganic metal ions into metal nanoparticles. This approach is an alternate route of synthesizing biocompatible nanoparticles compared to chemical synthesis, which is the latest possible way of linking material science and biotechnology in the emerging field of nanobiotechnology. The extracts of various plants and plant parts such as leaf, fruit, flower, tuber and rhizome were used for the synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles, with further testing the efficacy of nanoparticles for antimicrobial activity. Among such plants, Murraya koenigii [12], Garcinia mangostana [13], Olea europaea [14], Tribulus terrestris [15], Artemisia nilagirica [16], Hibiscus cannabinus [17], Alternanthera sessilis [18], Aegle marmelos [19], Melothria maderaspatana [20], Morinda citrifolia [21], Syzgium samasangense [22], Phyllanthus maderaspatensis [23], Hemidesmus indicus [24], Leea indica [25], Carica papaya [26] Lawsonia inermis (Henna) [27], Linum usitatissimum [28], Lavandula intermedia [29], Allophylus serratus [30], Bauhinia acuminate, Biophytum sensitivum [31] and Polygonum glabrum [32] were employed.

Maranta arundinacea, l also known as arrowroot Maranta, belongs to family Marantaceae. Arrowroot is a perennial plant growing to a height of between 0.3 m (1 ft) and 1.5 m (5 ft). Twin clusters of small white flowers bloom about 90 d after planting. The plant exhibits various medicinal properties such as being antidysentric, antidote, aphrodisiac, antipyretic, depurative, and hypocholesterolemic. Its leaves are lanceolate. The edible part of the plant is the rhizome. Maranta arundinacea, L is reported for the antioxidant activity and hypolipidemic effect [33, 34]. The biochemical activities of plants are mainly due to the phytochemical components present in it. Maranta arundinacea,L. is rich with various phytochemicals such as alkaloids, carbohydrates, cardiac glycosides, proteins, amino acids, phenolic compounds, terpenoids, saponins, flavones and gum [35]. The present investigation is undertaken to study phytosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaf extract of Maranta arundinacea,L, factors governing the synthesis of silver nanoparticles and antibacterial activity of the synthesized nanoparticles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and plant material

Silver nitrate was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich chemicals. All glassware was washed with distilled water and dried in oven. Fresh leaves of M. arundinacea were collected from Siddapur, Uttarkannad, Karnataka, India.

Preparation of leaf extract

Ten g of leaves were thoroughly washed with de-ionized water and were cut into small pieces and boiled in 100 ml of deionized water for 20 min. Extract was filtered with Whatman 41 filter paper and stored at 4 °C to be used for further experiments.

Synthesis of silver nanoparticles

Five ml of M. arundinacea leaf extract was added into 95 ml of aqueous solution of 1 mmol AgNO3 for reduction and stabilization of Ag+ions into silver nanoparticles. The colour of solution changes from colourless to brown, indicating the formation of silver nanoparticles and further confirmed by characteristic absorption spectra by UV-Vis spectrometer.

Different parameters for investigation

The effect of various parameters of reaction mixture on end product was spectrophotometrically investigated.

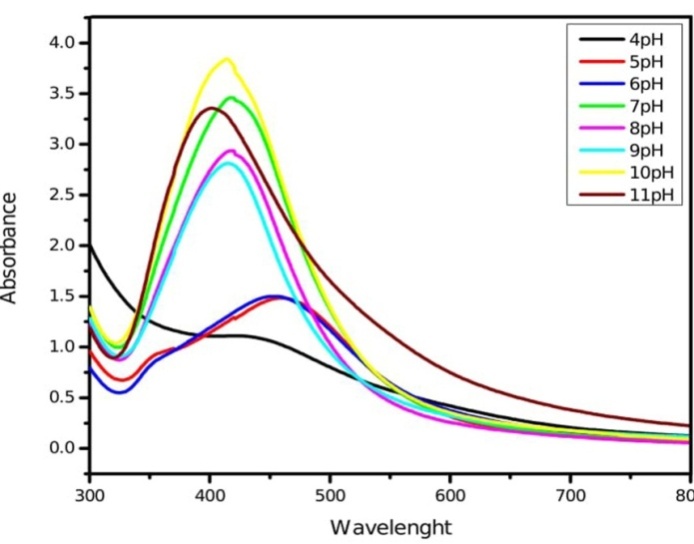

Hydrogen ion concentration (pH)

The pH of reaction mixture was maintained at 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11 respectively.

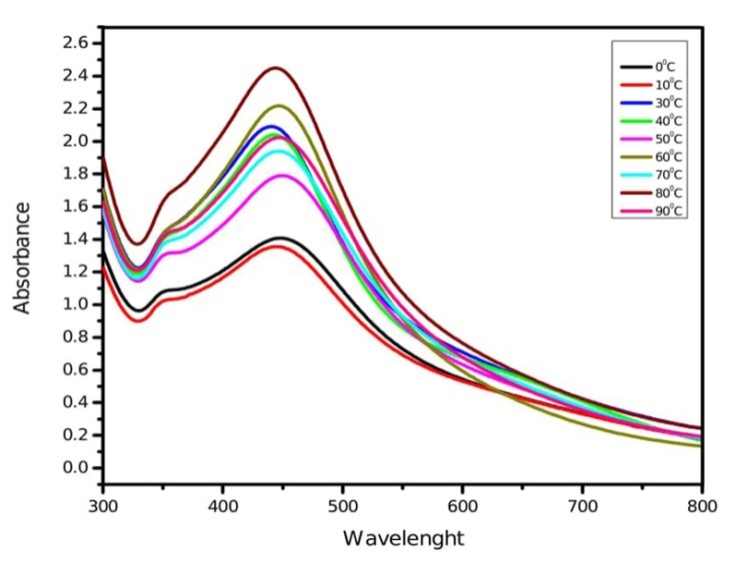

Reaction temperature

The reaction temperature was maintained at 0, 10, 37, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80 and 90°C using water bath.

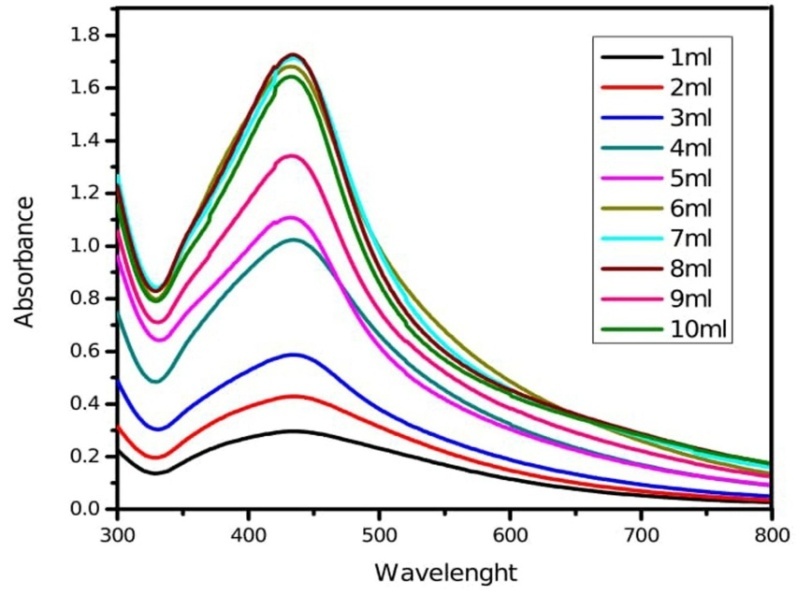

Concentration of leaf extract

The serial dilution of the plant leaf extract varying 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 ml can be used with the same volume ratio (5 ml extract 95 ml 1 mmol silver nitrate).

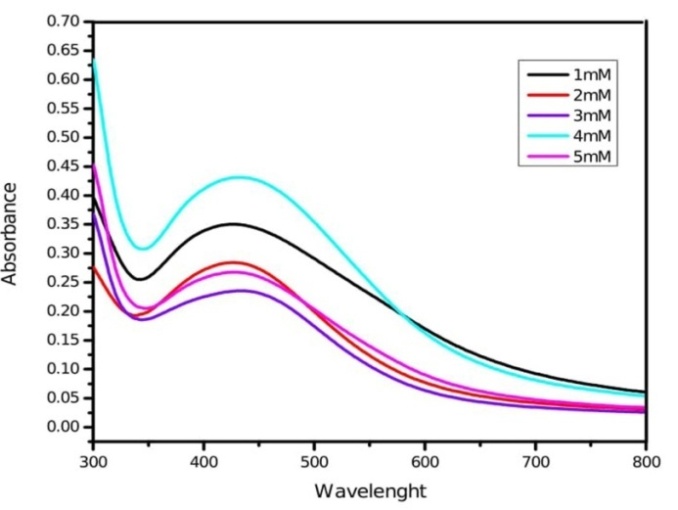

Concentration of silver nitrate solution

The reaction was monitored by using different concentration of silver nitrate (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 mmol) solution for the synthesis of nanoparticles.

Characterization of silver nanoparticles

The UV-Vis spectrum of the sample was monitored using UV-2450 (Shimadzu) spectrophotometer operated with 1 nm resolution within the range of 300–800 nm. Further characterization was done by Fourier Transform Infra Red Spectrophotometer (FTIR) (F-7000FL) spectrometer. In order to remove any free biomass residue, the residual solution after reaction was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 20 min and the resulting suspension was re-dispersed in 10 ml sterile distilled water. Centrifugation and re-dispersion were repeated for three times. Finally, the dried samples were palletized with KBr and analyzed using FT-IR. For Energy dispersive X-ray diffraction (EDX) analysis, the reduced silver was dried on a carbon tape placed on a copper stub and performed on a HITACHI SU6600. Dried sample was collected for the determination crystalline structure of Ag nanoparticles by X’ Pert pro X-ray diffractometer operated at 40 kv and 30 mA with Cu Kα radiation. Morphological characterization of the sample was done by High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HR-TEM) (JEOL JSM6701–F), a pinch of dried sample was coated on a carbon tape. It was again coated with platinum in an auto fine coater and then the material was subjected to analysis.

Antibacterial activity

Antimicrobial activity was analyzed with synthesized silver nanoparticles by well diffusion method against Gram positive bacteria Viz. Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC3160), Bacillus polymyxa (MTCC 190) and Gram-negative bacteria Viz. Escherichia coli (MTCC 723, 1554) and Salmonella typhi (MTCC3216). Bacterial species were brought form Institute of microbial technology (CSIR-IMTech), Chandigarh. Initially, the stock cultures of bacteria were revived by inoculating in broth media and grown at 37ᵒC for 18 h. Agar Muller Hinton media were poured into plates and wells were made. Each plate was inoculated with 18 h old cultures (100 μl,10-4cfu) and spread evenly on the plate. After 20 min, the wells were filled with the tested nanoparticles at different volumes. All the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and the diameter of inhibition zone were noted.

Statistical analysis

The values were expressed as the mean±standard error of the mean, and all measurements were made in triplicate. The collected data were statistically analysed using a one-way analysis of variances with SPSS 20 software. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

When leaf extract of M. arundinacea was added to aqueous silver nitrate solution, a dark brown colour appeared within 2 min (fig. 1B). Our results collaborate with the silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf mucilage of Sesamum lacinatum Klein ex Willd., where colour change occurred within 2 min [36]. The colour change was arising due to the property of quantum confinement, which is a size-dependent property of nanoparticles which affects the optical property of the nanoparticles [37]. The absorption spectra showed an intense peak at 406 nm due to the surface plasmon resonance band of silver nanoparticles and broadening of peak indicated that the particles are polydispersed. Different parameters were optimized including pH, temperature, leaf extract concentration and silver nitrate concentration were identified as factors affecting the synthesis of silver nanoparticles.

Fig. 1: (A) Habit of M. arundinacea (B) Visual observation a) AgNO3 b) leaf extract c) leaf extract+AgNO3

Factors influencing the synthesis of nanoparticles

Effect of pH

The pH plays a vital role in synthesis of nanoparticles and in controlling their size and shape. Acidic condition hinders the formation of nanoparticles and forms a larger-sized nanoparticle, whereas small and highly dispersed nanoparticles were formed at basic pH which enhances the formation of nanoparticles. At basic pH large numbers of functional groups are available for silver binding which facilitated a greater number of silver nanoparticles to bind and subsequently form a greater number of nanoparticles with smaller diameters. The raising in pH value at basic condition enhances the repulsive barrier and keeping the nanoparticles physically apart from each other. The excess of H+ ions at low pH, on the contrary, depresses ionization of the active reducing agent and gates electron transfer due to protonation [38]. The optimum pH for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles is pH=7 (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: UV-Vis absorption spectra of silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf extract of M. arundinacea at different pH

Effect of temperature

The synthesis of silver nanoparticles depends on the temperature, increased in temperature increases the rate of formation of silver nanoparticles. The size is reduced initially due to the reduction in aggregation of the growing nanoparticles. The peak sharpness increases with an increase in the reaction temperature. It is evident that increase in reaction rate of conversion of the metal ion to nanoparticles occurs at higher temperature [39]. The optimum temperature for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles is 80 °C (fig. 3). Reaction temperatures play an important role to control the nucleation process of nanoparticles configuration.

Fig. 3: UV-Vis absorption spectra of silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf extract of M. arundinacea at different temperatures

Effect of leaf extract concentration

The quantity of leaf extract plays an important role in the complete conversion of silver ions into silver nanoparticles. Fig. 4 depicts a series of absorption spectra recorded from the solution of silver nanoparticles at different leaf extract concentrations of experimental plants. The optimum condition for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles is 8 ml (fig. 4). The sharpness of the absorption peak is dependent on the quantity of leaf and fruit extract, which gets sharpened at higher quantity up to a certain limit further, increase in quantity showed broader absorption peak. Increase in the leaf extract quantity decreases the size of silver nanoparticles [40].

Effect of salt concentration

Variation in silver nitrate concentration (1-5 mmol) causes variation in the size of nanoparticles. 1 mmol silver nitrate solution is suitable to yield more number of small-sized silver nanoparticles with sharp intense absorption peak (fig. 5). The absorbance intensity of the solutions increased with higher concentration of silver nitrate due to an enhancement in oxidation of hydroxyl groups by silver ions [41]. The spectrum can exhibit a shift towards the red end or the blue end depending upon the particle size, shape, state of aggregation and the surrounding dielectric medium [42]. Physico-chemical conditions of reaction mixture such as pH, reaction temperature, leaf extract concentration and silver nitrate concentration have been standardized to obtain sharp intense absorption peaks at 406 nm in M. arundinacea respectively, which indicate the formation of small-sized mono-dispered silver nanoparticles.

Fig. 4: UV-Vis absorption spectra of silver nanoparticles synthesized by different leaf extract concentration of M. arundinacea

Fig. 5: UV-Vis absorption spectra of silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf extract of M. arundinacea at different silver nitrate concentration

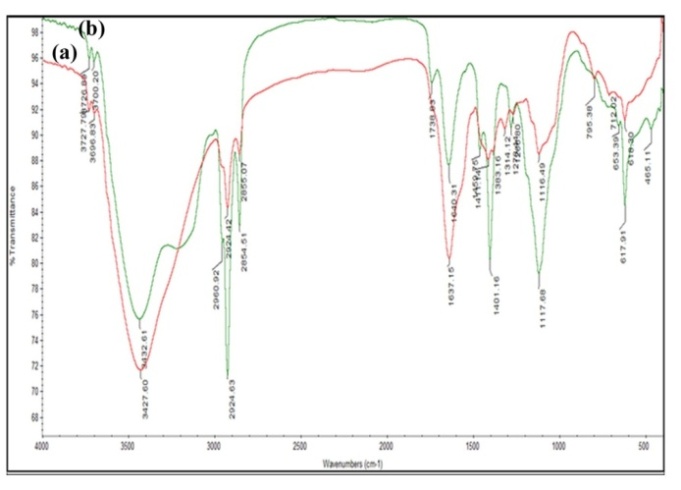

FTIR

FTIR measurements were carried out to identify the possible reducing biomolecules in the plant (leaf) extract responsible for the formation of silver nanoparticles. Fig. 6 (a and b) and table 1 show that the FTIR spectra of M. arundinacea leaf extract and silver nanoparticles, respectively. The band at ~3400 cm-1 arises due to O-H stretching of phenols. The intensity of band was increased in silver nanoparticles compared to plant extract, and this may be due to the binding of silver ions with hydroxyl groups. The band shift in the hydroxyl groups and increased band intensities for carbonyl groups in FTIR spectra confirm the oxidation of these functional groups during synthesis both hydroxyl and carbonyl groups are involved in the reduction and capping of silver nanoparticles. The spectra of silver nanoparticles synthesized by M. arundinacea showed two small bands occurring at ~2900 and 2800 cm-1 assigned to the methylene antisymmetric and symmetric vibration of hydrocarbons present in the protein; similar peaks were observed in T. asperellun [43]. The absorption band at ~1455 cm-1 was observed in M. aurundinacea was attributed to methylene scissoring vibration. The band at ~1098 cm-1 was observed in the spectra of silver nanoparticles by M. aurundinacea corresponds to C-O, C-N or C-C stretching of amino acids. The shift in the band positions 1637-1640 cm-1, 1384-1401 cm-1 suggest that these functional groups are oxidized during the reaction period and responsible for the formation of silver nanoparticles. The leaf extract shows the absorption peaks at 1314, 795, 712 cm-1 was due to the –NO3 stretching from silver nitrate, C-Cl stretching of alkyl halides and C-H stretching of strong aromatic mono-substituted benzene. The absorption band at 1102 and 800 cm-1 observed in the leaf extract and silver nanoparticles of M. arundinacea arises due to OH out-of-plane deformation of as ascorbic acid and bending vibration of C-H groups of phenyl rings. The spectrum of silver nanoparticles shows band at 738 and 653 cm-1 arises due to carbonyl group (C=O) and alpha-glucopyranose rings deformation of carbohydrates and peaks were formed after the bioreduction of nanoparticles. The carbonyl groups from the flavonoid and polyphenolic compound have a strong ability to bind silver ion, so that the flavonoid and polyphenoilc compound could form a coat over the metal nanoparticles to prevent gathering particles. The linkages between carbonyl groups and metal ion give a well-known signature in the FTIR spectrum. After the bioreduction of Ag+, shift in the peak at 1740 cm-1 is attributed to the binding of carbonyl group with nanoparticles.

Fig. 6: FTIR spectra of silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf extract of M. arundinacea (a) leaf extract (b) silver nanoparticles solution

Table 1: FTIR absorption peaks and their associated functional groups present in leaf extract and silver nanoparticles synthesized by M. arundinacea

| S. No. | Leaf extract cm-1 | Silver nanoparticles cm-1 | Functional groups |

| 1 | 3427.60 | 3432.61 | N-H/O-H stretching |

| 2 | 2924.42 | 2924.63 | Methylene symmetric vibrational mode |

| 3 | 2855.07 | 2854.51 | Methylene antisymmetric vibrational mode |

| 4 | - | 1738.83 | Carbonyl stretching |

| 5 | 1637.15 | 1640.31 | Amide band I |

| 6 | - | 1459.75 | Methylene scissoring vibrations |

| 7 | 1383.16 | 1401.16 | C=C stretching of aromatic amines |

| 8 | 1314.12 | - | -NO3 stretching, which comes from silver nitrate |

| 9 | 1266.80 | 1278.44 | Amide band III |

| 10 | 1116.49 | 1117.68 | -C-O-C-linkages |

| 11 | 795.38 | - | Corresponds to C-Cl stretching alkyl halides |

| 12 | 712.02 | - | C-H stretching strong aromatic mono-substituted benzene |

| 13 | - | 653.39 | Alpha-glucopyranose rings deformation of carbohydrates |

| 14 | 618.30 | 617.91 | C=C group/aromatic rings/C=O stretching in carboxyl groups of proteins |

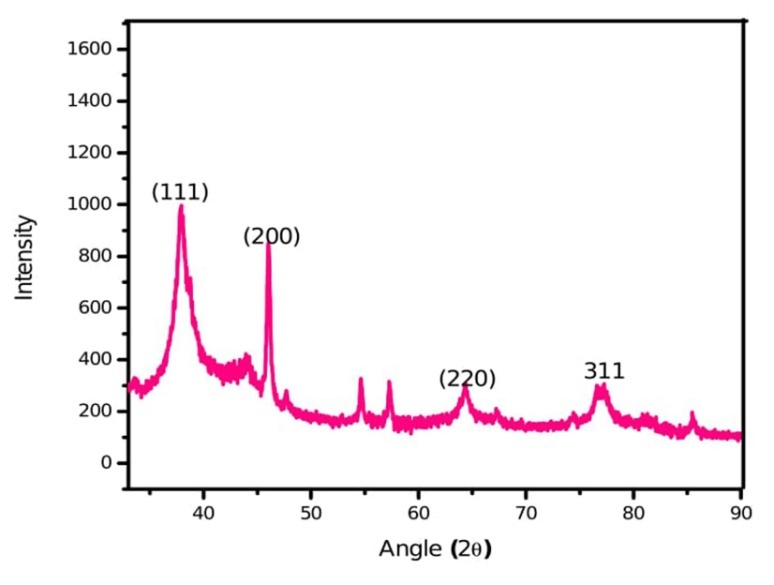

Fig. 7: X-ray diffraction spectrum of silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf extract of M. arundinacea

X-ray diffraction

It is a very powerful and versatile quantitative technique to elucidate the complete three-dimensional structure of matter at molecular and atomic levels. Elucidation of detail structural features at atomic levels is possible if the specimen is in a crystalline state. The diffraction intensities were recorded from 30օ to 90օ at 2θ. The XRD pattern of M. arundinacea silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf extract showed four diffraction peaks 37.86օ, 44.04օ, 64.13օ, 76.98օ 19օ corresponding to (111), (200), (220) and (311) planes respectively (fig. 7). All the peaks in XRD pattern can be readily indexed to a face-centered cubic structure of silver as per database of Joint committee on powder diffraction standards (JCPDS) (file number 893722/04-0783). It confirms the FCC crystalline nature of elemental silver and shape of nanoparticles are spherical and hexagonal. The Bragg angle which gives the mean size of 8.96 nm of leaf extract of silver nanoparticles synthesized by M. arundinacea.

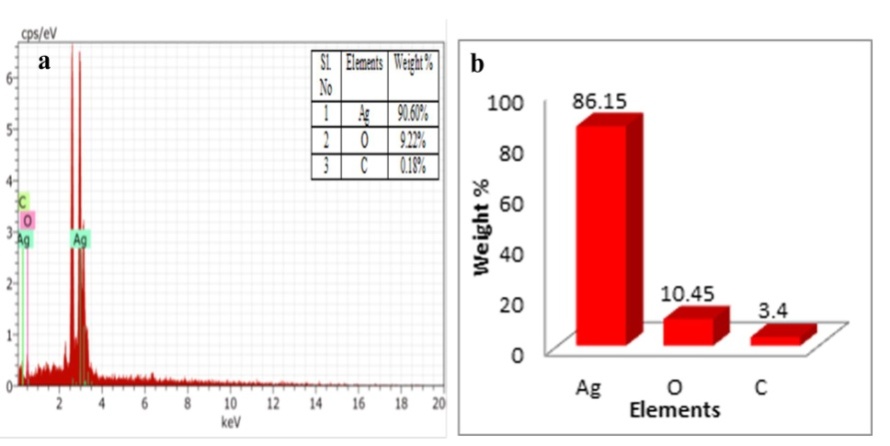

EDX

The EDX spectrum shows high intense major peak of elemental silver and less intense peak of carbon (C) and oxygen (O) also arises due to the formation of capping layers on the surface of nanoparticles by biomolecules which are present in the leaf extract (fig. 8). The EDX results confirm the reduction of silver ions to elemental silver. Our results are in conformity with other findings [44]. It gives qualitative as well as quantitative status of elements that may be involved in the formation of nanoparticles. The strong signal of elemental peak at approximately 3 kev exist the absorption of metallic silver nanoparticles due to surface plasmon resonance peak [45].

Fig. 8: a) EDX spectrum b) quantitative analysis of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles by using leaf extract of M. arundinacea

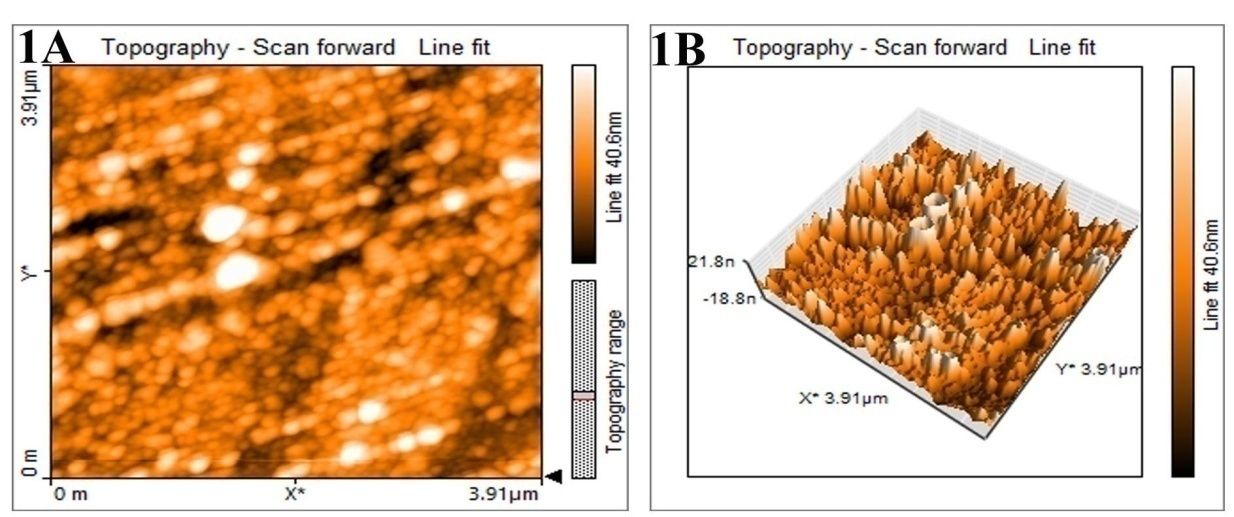

Fig. 9: AFM images of silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf extract of M. arundinacea (1A) Two-dimensional image (1B)-Three-dimensional images

AFM

The surface morphology of the nanoparticles was visualized by atomic force microscope to analyze the particles shape and size. The two-and three-dimension images of silver nanoparticles synthesized by M. arundinacea leaf extract reveals that the particles are monodispersed and spherical in shape with size ranging from 30 to 90 nm (fig. 9). The line graph shows that distribution of the silver nanoparticle and distance between them.

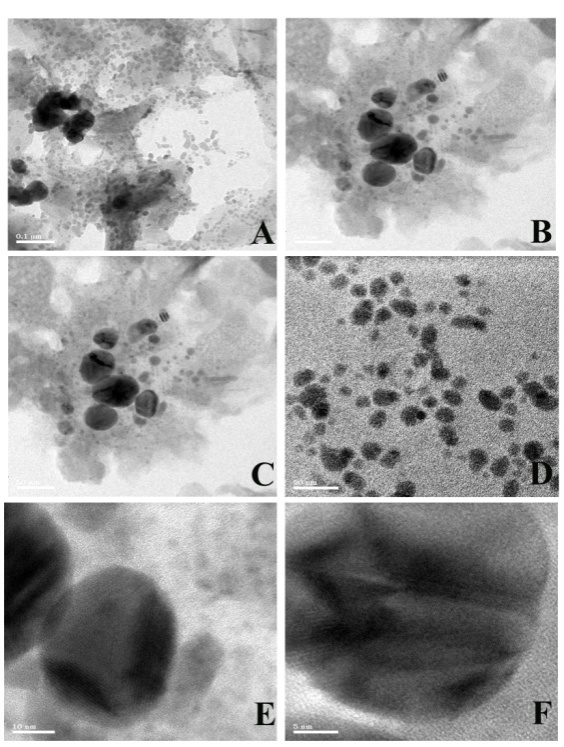

HR-TEM

The silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf extract of M. arundinacea was analyzed by HR-TEM with different magnification as depicted in fig. 10. The nanoparticles are spherical and no aggregation was evident in fig. 10, size ranges between 5 and 30 nm.

Antimicrobial activity

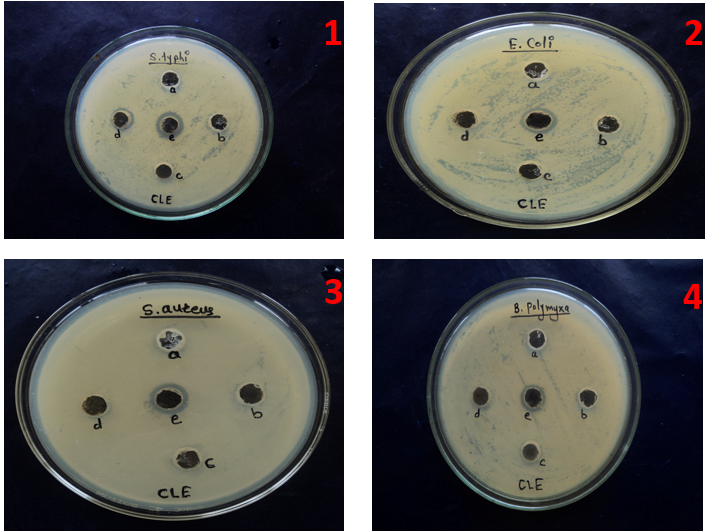

The silver nanoparticles showed good antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive (S. aureus, B. polymyxa) and Gram negative bacteria (E. coli, S. typhi). Silver nanoparticles at different concentrations (25 µl, 50 µl, 100 µl and 250 µl) showed different zone of inhibition (ZOI) with respect to different microorganisms (fig. 11 and table 2). In the present investigation, silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf extracts of M. arundinacea show that higher antibacterial activity in Gram negative bacteria than the Gram-positive bacteria. Gram-negative bacteria are more sensitive to silver nanoparticles due to difference in the cell wall structure of bacteria. The cell wall of the Gram-positive bacteria is composed of a thick layer of peptidoglycan, consisting of linear polysaccharide chains cross-linked by short peptides, thus forming more rigid structure leading to difficult penetration of the silver nanoparticles compared to the Gram-negative bacteria where the cell wall possesses thinner layer of peptidoglycan [46]. Due to species specificity S. typhi are more sensitive to silver nanoparticles compared to E. coli. The E. coli was shown sensitive towards the silver nanoparticles of leaf extract of M. arundinacea (5.100±0.078 mm). The highest zone of inhibition 7.033±0.033 mm was observed in S. typhi at 250 µl** and lowest zone of inhibition 4.100±0.066 mm was seen in B. polymyxa at 250 µl**. The moderate zone of inhibition 6.033±0.033 mm and 5.100±0.078 mm was observed in S. aureus and E. coli at 250 µl** (table 2). As per statistically analysis reveals that zone of inhibition is varied with different concentration. Results obtained varied significantly with each treatments. It was observed that ZOI formed by E. coli, S. typhi, S. aureues, and B. polymyxa, was significant at the level of p<0.05. The mechanism behind the activity of silver nanoparticles on bacteria not yet fully explored; the three most common mechanisms proposed to date are (1) the disruption of ATP production and DNA replication by uptake of free silver ions, (2) Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) generation by silver and silver nanoparticles and (3) direct damage of silver nanoparticles to the cell membranes [47]. Feng et al., (2008) and Matsumura et al., (2003) proposed that silver nanoparticles release silver ions which interact with thiol groups of many enzymes, thus inactivating most of the respiratory chain enzymes, leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species enzymes, which causes the self-destruction of the bacterial cells and interruption of DNA replication due to damage of the DNA [48-50].

Fig. 10: HR-TEM Images of silver nanoparticles synthesized by leaf extract of M. arundinacea (A-0.1 µm, B-100 nm, C-50 nm, D-20 nm, E-10 nm, F-5 nm)

Fig. 11: Antimicrobial activity of concentrations of silver nanoparticles 1) Salmonella typhi 2) Escherichia coli 3) Staphylococcus aureus 4) Bacillus polymyxa. (a) Control, (b) 25, (c) 50, (d) 100 and (e) 250 µl

Table 2: Antibacterial and antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles by leaf extract of M. arundinacea

| Different concentration of AgNPs (µl | Zone of inhibition (mm) | |||

| Escherichia coli | Salmonella typhi | Staphylococcus aureus | Bacillus polymyxa | |

| Control | - | - | - | - |

| 25 | - | - | - | - |

| 50 | - | - | - | - |

| 100 | - | 2.100±0.058b | - | - |

| 250 | 5.100±0.078a | 7.033±0.033a | 6.033±0.033a | 4.100±0.066a |

Note: Each value represents the mean ±SE of triplicates; mean in each column followed by similar letters are not significantly different at 5 % probability level using tukey’s test

CONCLUSION

Plant-mediated biosynthesis offers a rapid, cheap, clean, safe and eco-friendly approach. The spherical shaped silver nanoparticles were formed by using leaf extract as reductant and stabilizer. The silver nanoparticles were tunable by simply changing the pH, reaction temperature, leaf extract concentration and silver nitrate concentration of the reactions. The influences of physico-chemical factors increase reduction of silver precursor due to increased activity of leaf extract constituent. As a result, the number of nucleus and, thus size of the silver nanoparticles decreased with basic pH higher temperature of the reaction. The silver particles became more spherical-like in shape. The synthesized silver nanoparticles showed good antimicrobial activity against multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus polymyxa, Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhi. In the present investigation, silver nanoparticles highly toxic to Salmonella typhi. The Gram-negative bacteria shows highest antimicrobial activity than Gram-positive bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors thank the Chairman, P. G. Department of Studies in Botany, Karnatak University, Dharwad for providing necessary facilities and University Grant Commission, New Delhi for financial assistance under UGC-SAP-DSA I Phase programme of the department. One of the author (Rokhade) thank University for the award of the UGC-UPE fellowship; Authors acknowledge the instrumentation facility at USIC, K. U. Dharwad. Authors also acknowledge SAIF at IIT Madras for providing support in carry out HR-TEM and EDX.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Research was done by the main author Veena Rokhade under the guidance of Prof. T. C. Taranath.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

Mubarak Ali D, Thajuddin N, Jeganathan K, Gunasekaran M. Plant extract mediated synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles and its antibacterial activity against clinically isolated pathogens. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2011;85(2):360-5. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.03.009, PMID 21466948.

Sudhakar C, Selvam K, Govarthanan M, Senthilkumar B, Sengottaiyan A, Stalin M. Acorus calamus rhizome extract mediated biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their bactericidal activity against human pathogens. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2015;13(2):93-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2015.10.003.

Suriyakalaa U, Antony JJ, Suganya S, Siva D, Sukirtha R, Kamalakkannan S. Hepatocurative activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles fabricated using Andrographis paniculata. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013 Feb 1;102:189-94. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.06.039, PMID 23018020.

Gnanadesigan M, Anand M, Ravikumar S, Maruthupandy M, Vijayakumar V, Selvam S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by using mangrove plant extract and their potential mosquito larvicidal property. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4(10):799-803. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60197-1, PMID 22014736.

Jacob SJ, Finub JS, Narayanan A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Piper longum leaf extracts and its cytotoxic activity against Hep-2 cell line. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2012 Mar 1;91:212-4. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.11.001, PMID 22119564.

Akhtar MS, Panwar J, Yun YS. Biogenic synthesis of metallic nanoparticles by plant extracts. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2013;1(6):591-602. doi: 10.1021/sc300118u.

Das S, Das J, Samadder A, Bhattacharyya SS, Das D, Khuda Bukhsh AR. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles by ethanolic extracts of Phytolacca decandra gelsemium sempervirens hydrastis canadensis and thuja occidentalis induce differential cytotoxicity through G2/M arrest in A375 cells. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2013 Jan 1;101:325-36. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.07.008.

Swarnalatha C, Rachela S, Ranjan P, Baradwaj P. Evaluation of in vitro antidiabetic activity of Sphaeranthus amaranthoides silver nanoparticles. Int J Nanomat Biostr. 2012;2(3):25-9.

Alivisatos AP. Semiconductor clusters nanocrystals and quantum dots. Science. 1996;271(5251):933-7. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.933.

Kelly KL, Coronado E, Zhao LL, Schatz GC. The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: the influence of size shape and dielectric environment. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107(3):668-77. doi: 10.1021/jp026731y.

Sepeur S. Nanotechnology: technical basics and applications. Hannover: Vincentz; 2008.

Christensen L, Vivekanandhan S, Misra M, Kumar Mohanty AK. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using murraya koenigii (curry leaf): an investigation on the effect of broth concentration in reduction mechanism and particle size. Adv Mater Lett. 2011;2(6):429-34. doi: 10.5185/amlett.2011.4256.

Veerasamy R, Xin TZ, Gunasagaran S, Xiang TF, Yang EF, Jeyakumar N. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using mangosteen leaf extract and evaluation of their antimicrobial activities. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2011;15(2):113-20. doi: 10.1016/j.jscs.2010.06.004.

Awwad AM, Salem NM, Abdeen A. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Olea europaea leaves extract and its antibacterial activity. Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2012;2(6):164-70. doi: 10.5923/j.nn.20120206.03.

Gopinath V, Mubarak Ali D, Priyadarshini S, Priyadharsshini NM, Thajuddin N, Velusamy P. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Tribulus terrestris and its antimicrobial activity: a novel biological approach. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2012 Aug 1;96:69-74. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.03.023, PMID 22521683.

Vijayakumar M, Priya K, Nancy FT, Noorlidah A, Ahmed AB. Biosynthesis characterisation and anti-bacterial effect of plant-mediated silver nanoparticles using Artemisia nilagirica. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;41:235-40. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.04.017.

Bindhu MR, Umadevi M. Synthesis of monodispersed silver nanoparticles using Hibiscus cannabinus leaf extract and its antimicrobial activity. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2013 Jan 15;101:184-90. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.09.031, PMID 23103459.

Niraimathi KL, Sudha V, Lavanya R, Brindha P. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Alternanthera sessilis (Linn.) extract and their antimicrobial antioxidant activities. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013 Feb 1;102:288-91. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.08.041, PMID 23006568.

Patil S, Sivaraj R, Rajiv P, Rajendran V, Seenivasan R. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from leaf extract of Aegle marmelos and evaluation of its antibacterial activity. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015 Jan;7(6):169-73.

Srinivasan S, Indumathi D, Sujatha M, Sujitra K, Muruganathan U. Novel synthesis characterization and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles using leaf extract of Melothria maderaspatana (Linn)Cong. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;8(6):104-9.

Asha RP, Kavitha S, Shweta RS, Priyanka P, Vrinda A, Vivin TS, Silpa S. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using fresh leaf of Morinda citrifolia and its antimicrobial activity studies. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(3):459-61.

Nivetha T, Veronica S. Bioprospecting the in vitro antioxidant and anticancer activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized from the leaves of Syzgium samasangense. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(7):269-74.

Annamalai A, Christina VL, Christina V, Lakshmi PT. Green synthesis and characterisation of Ag NPs using aqueous extract of Phyllanthus maderaspatensis L. J Exp Nanosci. 2014;9(2):113-9. doi: 10.1080/17458080.2011.631041.

Latha M, Sumathi M, Manikandan R, Arumugam A, Prabhu NM. Biocatalytic and antibacterial visualization of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Hemidesmus indicus. Microb Pathog. 2015 May;82:43-9. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2015.03.008, PMID 25797527.

Reshma SK, Anju AJ, Jayanthi S, Ramalingam C, Anita AE. Investigation of biogenic silver nanoparticles green synthesized from Carica papaya. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7(3):107-10.

Rokhade VK, Taranath TC. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaf extract of leea indica (burm. f.) merr. and their synergistic antimicrobial activity with antibiotics. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2016;40(1):211-7.

Kumar KS, Kathireswari P. Biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPS) by Lawsonia inermis (henna) plant aqueous extract and its antimicrobial activity against human pathogens. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2016;5(3):926-37. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2016.503.107.

Anjum S, Abbasi BH. Thidiazuron enhanced biosynthesis and antimicrobial efficacy of silver nanoparticles via improving phytochemical reducing potential in callus culture of Linum usitatissimum L. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016 Feb 22;11:715-28. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S102359, PMID 26955271.

Elemike EE, Onwudiwe DC, Ekennia AC, Katata Seru L. Biosynthesis characterization and antimicrobial effect of silver nanoparticles obtained using Lavandula intermedia. Res Chem Intermed. 2017;43(3):1383-94. doi: 10.1007/s11164-016-2704-7.

Kero J, Sandeep BV, Sudhakar P. Synthesis characterization and evaluation of the antibacterial activity of Allophylus serratus leaf and leaf derived callus extracts mediated silver nanoparticles. J Nanomat. 2017:4213275-86.

Elizabath A, Mythili S, Sathiavelu A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from the medicinal plant Bauhinia acuminata and Biophytum sensitivum a comparative study of its biological activities with plant extract. Int J Appl Pharm. 2017;9(1):22-9. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2017v9i1.16277.

Rokhade VK, Taranath TC. Polygonum glabrum willd. leaf extract mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their assessment of antimicrobial activity. IOSR JPBS. 2018;13(3):68-75. doi: 10.9790/3008-1303026875.

Nishaa S, Vishnupriya M, Sasikumar J, Hephzibah P, Christabel GK. Antioxidant activity of ethanolic extract of Maranta arundinacea L tuberous rhizomes. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2012;5(4):85-8.

Damat. Hypolipidemic effect of cake from butylated arrowroot strach. ARPN J Sci Tech. 2012;2:1007-12.

Shintu PV, Radhakrishnan VV, Mohanan KV. Pharamacognostic standardisation of Maranta arundinacea L. an important ethnomedicine. J Pharm Phytochem. 2015;4(3):242-6.

Rokhade VK, Taranath TC. Synthesis of biogenic silver nanoparticles using sesamum laciniatum klein ex willed. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2014;43:221-5.

Kumara Swamy M, Sudipta KM, Jayanta K, Balasubramanya S. The green synthesis characterization and evaluation of the biological activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Leptadenia reticulata leaf extract. Appl Nanosci. 2015;5(1):73-81. doi: 10.1007/s13204-014-0293-6.

Stenesh J. Foundation of biochemistry. Biochemistry; 1998.

Huang H, Yang Y. Preparation of silver nanoparticles in inorganic clay suspensions. Compos Sci Technol. 2008;68(14):2948-53. doi: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.10.003.

Dubey SP, Lahtinen M, Sarkka H, Sillanpaa M. Bioprospective of Sorbus aucuparia leaf extract in development of silver and gold nanocolloids. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2010;80(1):26-33. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.05.024.

Kora AJ, Sashidhar RB, Arunachalam J. Gum kondagogu (Cochlospermum gossypium): a template for the green synthesis and stabilization of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial application. Carbohydr Polym. 2010;82(3):670-9. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.05.034.

Smitha SL, Nissamudeen KM, Philip D, Gopchandran KG. Studies on surface plasmon resonance and photoluminescence of silver nanoparticles. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2008;71(1):186-90. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2007.12.002, PMID 18222106.

Mukherjee P, Roy M, Mandal BP, Dey GK, Mukherjee PK, Ghatak J. Green synthesis of highly stabilized nanocrystalline silver particles by a non-pathogenic and agriculturally important fungus T. asperellum. Nanotechnology. 2008;19(7):075103. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/7/075103, PMID 21817628.

Ajitha B, Ashok Kumar Reddy Y, Shameer S, Rajesh KM, Suneetha Y, Sreedhara Reddy P. Lantana camara leaf extract mediated silver nanoparticles: antibacterial green catalyst. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2015 Aug;149:84-92. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2015.05.020, PMID 26057018.

Das J, Velusamy P. Antibacterial effects of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using aqueous leaf extract of Rosmarinus officinalis L. Mater Res Bull. 2013;48(11):4531-7. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2013.07.049.

Shrivastava S, Bera T, Roy A, Singh G, Ramachandrarao P, Dash D. Characterization of enhanced antibacterial effects of novel silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnol. 2007 May 4;18(22):225103-11. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/18/22/225103.

Feng QL, WU J, Chen GQ, Cui FZ, Kim TN, Kim JO. A mechanistic study of the antibacterial effect of silver ions on escherichia coli and staphylococcus aureus. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;52(4):662-8. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20001215)52:4<662::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-3, PMID 11033548.

Matsumura Y, Yoshikata K, Kunisaki SI, Tsuchido T. Mode of bactericidal action of silver zeolite and its comparison with that of silver nitrate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(7):4278-81. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.7.4278-4281.2003, PMID 12839814.

Morones JR, Elechiguerra JL, Camacho A, Holt K, Kouri JB, Ramirez JT. The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2005;16(10):2346-53. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/16/10/059, PMID 20818017.

Rai M, Yadav A, Gade A. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27(1):76-83. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.09.002, PMID 18854209.